Abstract

Background:

The objective is to summarize evidence from systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and meta-analyses evaluating the effects of any format of Internet-based, mobile-, or telephone-based intervention as a technology-based intervention in suicide prevention.

Materials and Methods:

This is an umbrella review, that followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 statement guidelines. An electronic search was done on September 29, 2022. Data were extracted by reviewers and then methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed by A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews-2. Statistical analysis was done by STATA version 17. Standard mean difference was extracted from these studies and by random effect model, the overall pooled effect size (ES) was calculated. I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity between studies. For publication bias, the Egger test was used.

Results:

Six reviews were included in our study, all with moderate quality. The overall sample size was 24631. The ES for standard mean differences of the studies is calculated as − 0.20 with a confidence interval of (−0.26, −0.14). The heterogeneity is found as 58.14%, indicating a moderate-to-substantial one. The Egger test shows publication bias.

Conclusion:

Our results show that technology-based interventions are effective. We propose more rigorous randomized controlled trials with different control groups to assess the effectiveness of these interventions.

Keywords: Overview, prevention, self-harm, suicide, technology

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a major public health problem although it has decreased about 5% in 2018-2020.[1] During 2019, the overall rate of suicide was 9/100,000 in the whole world.[2] According to the Global Burden of Disease-2019 report, self-harm is the 3rd cause of death in people aged 10–24 years.[3]

Suicide can be prevented, which needs public sector attention regarding planning and assigning evidence-based strategies (including restricting access to lethal means, gatekeeper training, educational and/or screening programs, access to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), technology-based interventions and follow-up care).[4,5]

In 2014, the World Health Organization, presented its first report on suicide, “Preventing suicide: A Global Imperative.” The purpose of this report was to increase the consciousness of the general public and to seek the support of different countries for this program to create community-based strategies preventing suicide. The 3rd goal of Sustainable Development Goals or SDG-3 is about reducing by one-third non-communicable diseases by 2030, and suicide mortality rate is an indicator of this goal.[6,7]

There are some people who have suicidal thoughts but do not seek face-to-face therapy for various reasons, such as financial problems, stigma, and limitation of access to services,[8] and especially for this group of people, technology-based interventions may be beneficial.[9,10,11] One of the important benefits of using these methods is providing fast service without delay.[12]

Technology-based interventions, in this review, are defined as interventions delivered by a telephone, mobile, either by SMS or applications, web-based and/or Internet-based device.

The use of these interventions in the field of psychiatry and/or suicide is increasing.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] These studies that assess the role of technology-based interventions are promising and there are many randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses in this field. One point that some researchers mention is that the effectiveness of interventions increases if it is specifically designed to prevent suicide, while many studies have dealt with a wide range of psychiatric problems and suicide together.[25] In a recent systematic review in 2023 by Sarubbi et al. the effectiveness of mobile apps was approved.[26]

Meta-reviews, over-reviews, and reviews of reviews also named umbrella reviews are generated in response to the existence of multiple systematic reviews or meta-analyses on a particular topic. In fact, systematic reviews and meta-analysis work on primary studies, but meta-reviews work on systematic reviews and meta-analysis[27] to create an overall picture of a specific research question.[28]

This review aims to summarize evidence from systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and meta-analyses evaluating the effects of any format of Internet-based, mobile-, or telephone-based intervention as a technology-based intervention in suicide prevention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this umbrella review, we have followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 Statement in conjunction with the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration Document.[29,30] This review was approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (ethical number: IR.MUI.MED.REC.1400.487).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was done by a Ph.D. of Health Information Management (RN), for relevant systematic reviews or meta-analyses or scoping reviews which were published from January 01, 2005, to September 29, 2022. Databases searched: PubMed, Medline, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest. Search terms indicative of suicide, self-harm, and mobile or online applications were employed [Appendix 1]. This study did not include systematic searches of gray literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Any technology-based interventions, i.e. Internet-based, web-based, E-mail, mobile- or telephone-based, mobile apps, text messages, and social networking which were used to prevent suicide ideation or behavior were included. The outcome was suicide ideation or behavior prevention. There was no restriction for the age of participants, and also for comparator groups. All systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and scoping reviews that include the keywords listed as the search terms above were included. Articles published in languages other than English were excluded from the study.

Data extraction

After the identification of records from databases (by RN), two reviewers (NM and SS) screened the article’s title and abstract separately. The remaining articles needed to be assessed in their full text. The full texts were assessed based on the eligibility criteria, which means the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. Then the remaining articles were assessed for their quality. After quality assessment, these data were extracted from the reviews; descriptive characteristics (title; authors; year of publication; study design; number of participants; number of RCTs included; databases searched; and the last searched date); interventions; comparators; outcomes; quantitative outcome data, i.e., effect size (ES) and confidence interval (CI) and heterogeneity (I2). The author’s comments, limitations, and methodological quality/risk of bias were also extracted. In the process of screening of title/abstracts and inclusion, methodological quality/risk of bias assessments, and data extraction which was done by two reviewers (NM and SS), any discrepancies were addressed through a discussion and if it was not solved, it was discussed with a third reviewer (ZF).

Assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias

There are some instruments for this assessment. One of the most popular of these tools, which is used by different umbrella reviews is A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR).[28,31,32] It was developed in 2007 and is used for randomized clinical trials (RCTs). AMSTAR-2 is then created for critical appraisal of systematic reviews of randomized and non-randomized studies. AMSTAR-2 is not developed to give an overall score. Reviewers should pay attention to critical domains. As mentioned in Shea’s article, we ranked our articles in the same way, which rates articles as high, moderate, low, and critically low.[32]

High quality is considered when there is there in no critical flaw and one or no non-critical flaws. Moderate quality means when a systematic review has no critical flaw but may have 2 or more noncritical one. A study is assessed as low if there is one critical flaw with/without noncritical one. And finally, a systematic review is considered as critical low, if it has more than one critical flaw.[32] The studies with the high or moderate quality have been included in the study and those with low or critically low quality were not included.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done for the 6 studies included in the study by Stata version 17. 2021. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. Standard mean difference was extracted as ES from these studies and by random effect model and the overall pooled ES was calculated. A negative ES indicated a protective effect of the intervention or lower risk of outcome.

I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity between studies. If the value was between 30% and 60%, it was assumed as moderate, and if it was between 50% and 90%, it meant substantial heterogeneity, and if it was more than 90%, it was assumed as very high or considerable heterogeneity.[33]

There are statistical tests to evaluate for the presence of publication bias; the Egger test was used in our review.[34] Egger test is based on a linear regression model that shows the possibility of publication bias. This test needs at least 6 studies.[35] If the width from the origin does not exceed zero, as we see in our review, it indicates that publication bias has occurred.

RESULTS

An overview of the results

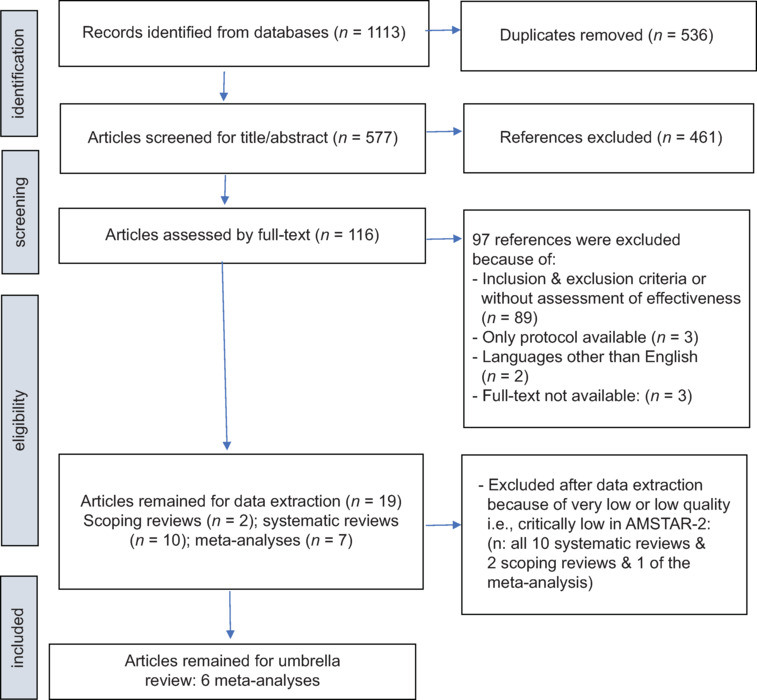

Our electronic search resulted in 1113 articles. After removing duplicates, 577 articles were remained. These articles were screened by their title and/or abstract and finally, 116 articles remained. These 116 articles were assessed by their full text which reached 19 articles for data extraction [Figure 1].[29] After the exclusion of reviews because of low-quality assessment, 6 meta-analyses remained for further analysis.[36,37,38,39,40,41]

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart study

Characteristics of the studies included

Six meta-analyses were included.[36,37,38,39,40,41] They were published between 2017 and 2022 in Germany, England, Australia, China, and Hong Kong. Five of them used only RCTs as their included articles and the other one was pseudo-RCT, or observational pre-test/post-test design.[40] The number of studies included in these reviews ranged 4–38. The total sample size of participants in the studies ranged from 1225 to 11,158. All of the 6 meta-analyses were done on adults and adolescents with suicidal thoughts/ideations or suicidal behavior. One review assessed non-suicidal thoughts in addition to suicidal thoughts and behaviors and 1 review assessed RCTs, pseudo-RCTs, and observational ones; the sample size, effects size, and CI for these 2 reviews were extracted for only our preferred outcome. These reviews used 3–7 databases (Web of Science; Scopus; PubMed; Applied Science and Technology; EMBASE; Cochrane Library; CENTRAL or Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Centre for Research Excellence of Suicide Prevention; Global Health; PsycARTICLES; PsycINFO; Sociological Abstracts; Social Services Abstracts; ERIC; CINAHL). The interventions that were of interest in these reviews were Internet-based CBT; mobile phone/smartphone apps; virtual reality; videos and computer games; self-guided digital interventions (app or web-based, which delivered theory-based therapeutic content); online apps and digital-based interventions. The comparator groups in the primary studies of these reviews were treatment as usual (active or passive treatment); wait-list; NA (not applicable); placebo; no intervention; face-to-face interventions; and attentional control condition. The outcome of interest in the primary studies included in the reviews was suicidal ideation, suicidal attempt or suicidal behavior; and nonsuicidal self-injury (injury or violence). AMSTAR-2 was used to critically appraise the studies. All of the 6 studies were of moderate quality [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the meta-analyses included in this study

| Author name and year of publication | Type of articles* | Number of articles | Number of RCTs | Participants** | Date ranged searched | Intervention# | Comparators## | Outcome### | Samples size for suicide ideation or behavior+ | Effect size overall (standard difference mean)++ | CI | AMSTAR 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Büscher R, 2020[36] | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | April 6, 2019 | 1 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 1 | 1567 | –0.29, P<0.001 | –0.40––0.19 | Moderate |

| Chen M, 2022[37] | 1 | 34 | 18 | 2 | March 1, 2020 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | 1, 2, 3, 5 | 1, 2 | 5297 | 0.17, P<0.001 | 0.08–0.26 | Moderate |

| Torok M, 2019[39] | 1 | 14 | 14 | 3 | May 21, 2019 | 6 | 1, 2, 3 | 1 | 4398 | –0.23, P<0∙0001 | –0.35––0.11 | Moderate |

| Witt K, 2017[40] | 3 | 14 | 8 | 3 | March 31, 2017 | 2, 7 | 1, 2, 5, 6 | 1 | 986 | –0.26, P=0.005 | –0.44––0.08 | Moderate |

| Yu T, 2021[41] | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | March 31, 2020 | 1 | 1, 2 | 1 | 1225 | 0.23 | 0.12–0.34 | Moderate |

| Schmeckenbecher J, 2022[38] | 1 | 38 | 38 | 1 | December 31, 2021 | 8 | 1, 2, 3 | 1 | 11,158 | –0.121 | –0.166––0.077 | Moderate |

*1: RCTs; 2: Single-arm studies and RCTs; 3: RCT, pseudo-RCT, or observational pre- and post-test design, **1: Adults and adolescents with suicidal ideation or behaviors; 2: Adults and adolescents from school, community settings, and clinical settings-with depression or suicidal thoughts or experienced self-harm; 3: Adults and adolescents with different psychiatric problems, #1: iCBT; 2: Mobile phone/smartphone apps; 3: VR; 4: Videos and computer games; 5: Self-guided digital interventions (app or web based, which delivered theory-based therapeutic content); 6: Online apps; 7: DBIs, ##1: TAU (active or passive treatment); 2: Wait-list; 3: NA; 4: Placebo; 5: No intervention; 6: Face-to-face interventions; 7: Attentional control condition, ###1: Suicidal ideation, suicidal attempt or suicidal behavior; 2: Nonsuicidal self-injury (injury or violence), +Sample size for suicide thoughts and behavior and for RCTs only, ++Effect size for suicide thoughts and behavior and for RCTs only. RCT: Randomized controlled trial, iCBT: Internet-based cognitive-based therapy, VR: Virtual reality, DBIs: Digital-based interventions, NA: Not applicable, AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess systematic review, CI: Confidence interval, TAU: Treatment as usual

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the 6 reviews included in the umbrella review (adopted from Shea et al.)[32]

| Criteria* | Authors |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Büscher R, 2020[36] | Chen M, 2022[37] | Torok M, 2019[39] | Witt K, 2017[40] | Yu T, 2021[41] | Schmeckenbecher J, 2022[38] | |

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Partial yes | Partial yes | Partial yes | Yes | Yes | Partial yes |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | Yes/Yes | No | Yes/Yes | Yes/Yes | No | No |

| Overall rating | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Study results

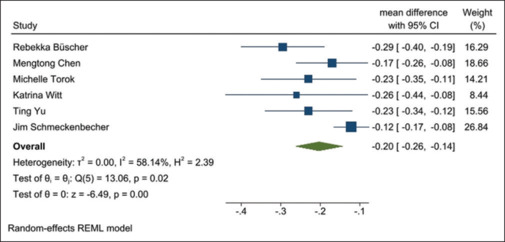

Random-effects REML model was used to find the overall ES and heterogeneity of the meta-analyses. The overall sample size was 24,631. In 2 studies, the ES was positive but with the meaning of protective effect of interventions for suicide. We have included them as negative values because we assumed negative values as protective ES or preventing suicide. The overall ES for the standard mean difference of the studies is − 0.20 with a CI of (−0.26, −0.14). The heterogeneity is found as 58.14% which is a moderate to substantial one [Figure 2]. According to the Cochrane Handbook, heterogeneity impacts generalizability, and therefore, researchers should select a strategy to encounter it. One of them is to “Perform a random-effects meta-analysis” and we have used this one.[42]

Figure 2.

Forest plot of treatment effects on suicidal ideation or behavior

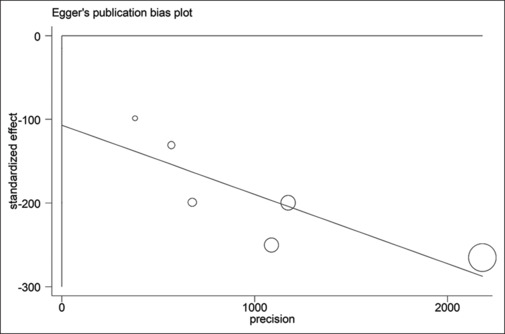

To check for publication bias, often a funnel plot is used. If there is no bias, the distribution pattern of the results should appear as an inverted and symmetric funnel;[43,44] but in the Cochrane Handbook, it is recommended to use a funnel plot when there are at least 10 studies in a review.[42] Trim and Fill plot is a kind of supplement for funnel plot, which does not work well in the presence of heterogeneity so we did not use it too. Egger test needs at least 6 studies,[35] and because our review consisted of 6 studies, this method was used to evaluate the presence of publication bias. In our review, the width from the origin did not exceed zero, which indicates that publication bias has occurred [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Egger’s plot for publication bias

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that technology-based interventions are effective in the prevention of suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy was found to be effective in decreasing suicidal ideation and behavior in adults and adolescents compared to the control group in Buscher et al. meta-analysis.[36]

Digital health interventions’ (DHIs) effectiveness was compared to other interventions in Chen et al. study and they found a meaningful effect in reducing suicide in adults and adolescents. In this study, their outcome of interest was the effectiveness of interventions on unintentional injury, violence, and suicide prevention, and we extracted data just for suicide prevention. Furthermore, this study reported a positive ES, because their outcome was effective and we used its ES as a negative one, meaning that the interventions had a protective effect on suicide. They found DHIs comparable to traditional interventions and face-to-face interventions and they found maintenance in study’s follow-ups.[37]

In Torok et al. meta-analysis, self-guided digital interventions for preventing suicide in adults and adolescents were statistically effective when assessed quickly after an intervention was undergone and when suicide was targeted instantly. Furthermore, with the purpose of being comparable, SMS or DVD-delivered interventions were excluded. In this study, digital interventions were proposed to be used more extensively.[39]

In Witt’s et al. meta-analysis, they identified a meaningful ES and a reduction in suicidal ideation and behavior in RCTs of online and mobile telephone applications in adults and adolescents. In this study, brief interventions, i.e. those delivered by SMS or E-mail were excluded. This review used RCTs, pseudo-RCTs, and observational studies as its primary included studies, and we extracted data only from RCTs included in this systematic review.[40]

Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy and its effectiveness were assessed in Yu and colleagues’ meta-analysis and in this study, a meaningful effect in preventing suicide in patients with suicidal thoughts was found. In this study, suicidal thoughts were categorized as a primary outcome and suicidal attempt as a secondary outcome. Standard mean difference was used for suicidal thoughts and odds ratio was used for suicidal behavior in this article; and we used only their data of mean differences.[41]

The effectiveness of distance-based suicide interventions was shown to have a small but significant effect on the prevention of suicide behavior and ideation in adults and adolescents. We have used the overall ES for the prevention of suicidal thoughts and behavior for this study.[38]

We found heterogeneity in both, studies using different forms of technology-based interventions and also in the comparator groups. Furthermore, there was no consistency in assessing the outcomes. Some assessed suicidal thoughts, suicidal behavior, nonsuicidal injuries, and even violence. In these situations, we extracted data according to our preferred outcome, i.e. suicidal thoughts or behavior.

The population of interest in some primary studies in the reviews was conducted on young people and some studies were conducted on adults. It is important to note that these may differ from each other. We think that adults and adolescents with different psychiatric problems cannot be compared together.

We found publication bias in our review. This may have different reasons; from the design and method of the study to the researcher’s low motivation to publish their article because of the statistically meaningless results and also the journal’s low tendency to publish an article with no statistically meaningful results.[45]

Finally, we propose more rigorous randomized controlled trials with different control groups to assess both the effectiveness and also the cost-effectiveness of these interventions.

Limitations

An important limitation in our study, and also in most of the umbrella studies is about overlapping of the primary studies included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We know that this could bring some form of bias and even it may influence some data which are entered more than once in the overview analysis.[27,28] Another constraint is about the primary studies. Their quality, accuracy, and point of view of their researchers could have an impact on our interpretation. Different studies recommend the authors of an umbrella review to assess the quality of each primary study of the systematic review,[27,28,46,47] although we were not able to do so. Furthermore, most primary studies included in our overview were RCTs, and this may influence the outcome positively. The heterogeneity and lastly the publication bias which were found to be limitations in our study.

CONCLUSION

Suicide is a public health issue that affects not only the person who suicide but also their family, friends, and the whole society. Overall, our review shows that technology-based interventions are effective in suicide prevention.

Recommendations for policy and practice

We suggest researchers conduct more evidence-based researches to investigate the effectiveness of using these interventions.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article is extracted from a postgraduate thesis. It is approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Ethical number.: IR.MUI.MED.REC.1400.487).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1

Pubmed:

(((“Suicide”[MeSH Terms] OR (suicid*[Title/Abstract] OR “Self harm”[Title/Abstract] OR “self poisoning”[Title/Abstract] OR “self cutting”[Title/Abstract] OR “self inflicted wound*”[Title/Abstract] OR “suicid*”[Title/Abstract] OR “self mutilat*”[Title/Abstract] OR “auto mutilat*”[Title/Abstract] OR “self injur*”[Title/Abstract] OR “self destruct*”[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((“Internet-Based Intervention”[MeSH Terms] OR “internet based intervention*”[Title/Abstract] OR “web based intervention*”[Title/Abstract] OR “online intervention*”[Title/Abstract] OR “internet intervention*“[Title/Abstract]) OR ((“Medical Informatics”[MeSH Terms] OR “Telemedicine”[MeSH Terms] OR “Information Technology”[MeSH Terms] OR “Telemedicine“[Title/Abstract] OR “Medical Informatics”[Title/Abstract] OR “Information Technology”[Title/Abstract] OR “internet”[Title/Abstract] OR “mobile”[Title/Abstract] OR “web”[Title/Abstract] OR “email”[Title/Abstract] OR “e-mail”[Title/Abstract] OR “online”[Title/Abstract] OR “social media”[Title/Abstract] OR “social network*”[Title/Abstract] OR “website”[Title/Abstract] OR “remote consultation”[Title/Abstract] OR “mobile health”[Title/Abstract] OR “m health”[Title/Abstract] OR “mhealth”[ Title/Abstract] OR “telehealth”[Title/Abstract] OR “tele-health”[Title/Abstract] OR “e health”[Title/Abstract] OR “ehealth”[Title/Abstract]) AND “intervention*”[Title/Abstract]))) AND (“Systematic Review” [Publication Type] OR “Meta-Analysis” [Publication Type] OR “research synthesis”[Title/Abstract] OR “research integration”[Title/Abstract] OR “data synthesis”[Title/Abstract] OR “meta analys*”[Title/Abstract] OR “meta analyz*”[Title/Abstract] OR “meta analyt*”[Title/Abstract] OR “metaanalys*”[Title/Abstract] OR “metaanalyz*”[Title/Abstract] OR “metaanalyt*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Systematic Review”[ Title/Abstract] OR “Meta-Analysis”[ Title/Abstract] OR “scoping review*”[Title/Abstract])

Embase

| Number | Query |

|---|---|

| #18 | #3 AND #14 AND #17 |

| #17 | #15 OR #16 |

| #16 | “systematic review”:ti, ab OR “meta analysis”:ti, ab OR”scoping review”:ti, ab OR”research synthesis”:ti, ab OR ”research integration”:ti, ab OR”data synthesis”:ti, ab OR”meta analys*”:ti, ab OR”meta analyz*”:ti, ab OR”meta analyt*”:ti, ab OR”metaanalys*”:ti, ab OR”metaanalyz*”:ti, ab OR”metaanalyt*”:ti, ab |

| #15 | “systematic review”/exp OR ”meta analysis”/exp OR”scoping review”/exp |

| #14 | #6 OR #13 |

| #13 | #9 AND #12 |

| #12 | #10 OR #11 |

| #11 | “intervention”:ti, ab |

| #10 | “intervention”/exp OR ”intervention study”/exp |

| #9 | #7 OR #8 |

| #8 | “medical informatics”:ti, ab OR ”information technology”:ti, ab OR ”telemedicine”:ti, ab OR ”internet”:ti, ab OR ”mobile”:ti, ab OR ”web”:ti, ab OR ”email”:ti, ab OR ”e-mail”:ti, ab OR ”online”:ti, ab OR ”social media”:ti, ab OR ”social network*”:ti, ab OR ”website”:ti, ab OR ”remote consultation”:ti, ab OR ”mobile health”:ti, ab OR ”m health”:ti, ab OR ”mhealth”:ti, ab OR ”telehealth”:ti, ab OR ”tele-health”:ti, ab OR ”e health”:ti, ab OR ”ehealth”:ti, ab |

| #7 | “medical informatics”/exp OR”telemedicine”/exp OR”telehealth”/exp OR ”information technology”/exp |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #5 | “internet based intervention*”:ti, ab OR”web based intervention*”:ti, ab OR”online intervention*”:ti, ab OR ”internet intervention*”:ti, ab |

| #4 | “web-based intervention”/exp |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #2 | “suicid*”:ti, ab AND”self harm”:ti, ab OR”self poisoning”:ti, ab OR”self cutting”:ti, ab OR”self inflicted wound*”:ti, ab OR”suicid*”:ti, ab OR”self mutilat*”:ti, ab OR”auto mutilat*”:ti, ab OR”self injur*”:ti, ab OR”self destruct*”:ti, ab |

| #1 | “suicide”/exp |

Cochrane Library

| ID | Search |

|---|---|

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Suicide] explode all trees |

| #2 | (suicid* OR “Self harm” OR “self poisoning” OR “self cutting” OR “self inflicted wound*” OR “suicid*” OR “self mutilat*” OR “auto mutilat*” OR “self injur*” OR “self destruct*”):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Internet-Based Intervention] explode all trees |

| #5 | (“internet based intervention*” OR “web based intervention*” OR “online intervention*” OR “internet intervention*”):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor: [undefined] explode all trees |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Telemedicine] explode all trees |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Information Technology] explode all trees |

| #10 | (“Telemedicine” OR “Medical Informatics” OR “Information Technology” OR “internet” OR “mobile” OR “web” OR “email” OR “e-mail” OR “online” OR “social media” OR “social network*” OR “website” OR “remote consultation” OR “mobile health” OR “m health” OR “mhealth” OR “telehealth” OR “tele-health” OR “e health” OR “ehealth”):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) |

| #11 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 |

| #12 | (intervention*):ti, ab, kw (Word variations have been searched) |

| #13 | #11 AND #12 |

| #14 | #4 OR #5 OR #13 |

| #15 | #3 AND #14 |

| #16 | #15 limited to Cochrane Reviews |

Scopus:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (suicid* OR “Self harm” OR “self poisoning” OR “self cutting” OR “self inflicted wound*” OR “suicid*” OR “self mutilat*” OR “auto mutilat*” OR “self injur*” OR “self destruct*”)) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“internet based intervention*” OR “web based intervention*” OR “online intervention*” OR “internet intervention*”)) OR ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Telemedicine” OR “Medical Informatics” OR “Information Technology” OR “internet” OR “mobile” OR “web” OR ” ‘email OR “e-mail” OR “online” OR “social media” OR “social network*” OR “website“ OR “remote consultation” OR “mobile health” OR “m health” OR “mhealth” OR “telehealth” OR “tele-health” OR “e health” OR “ehealth”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (intervention*)))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“systematic review” OR “meta analysis” OR “scoping review” OR “research synthesis” OR “research integration” OR “data synthesis” OR “meta analys*” OR “meta analyz*” OR “meta analyt*” OR “metaanalys*” OR “metaanalyz*” OR “metaanalyt*”))

Proquest:

AB, TI(“systematic review” OR “meta analysis” OR “scoping review” OR “research synthesis” OR “research integration” OR “data synthesis” OR “meta analys*” OR “meta analyz*” OR “meta analyt*” OR “metaanalys*” OR “metaanalyz*” OR “metaanalyt*”) AND (su (suicide) OR AB, TI (suicid* OR “Self harm” OR “self poisoning” OR “self cutting” OR “self inflicted wound*” OR “self mutilat*” OR “auto mutilat*” OR “self injur*” OR “self destruct*”)) AND ((AB, TI(“Telemedicine” OR “Medical Informatics” OR “Information Technology” OR “internet” OR “mobile” OR “web” OR “email” OR “e-mail” OR “online” OR “social media” OR “social network*” OR “website” OR “remote consultation” OR “mobile health” OR “m health” OR “mhealth” OR “telehealth” OR “tele-health” OR “e health” OR “ehealth”) AND AB, TI (intervention*)) OR (su(“Internet-Based Intervention”) OR AB, TI(“internet based intervention*” OR “web based intervention*” OR “online intervention*” OR “internet intervention*”)))

WEB OF SCIENCE SEARCH STRATEGY

| 1: TS=(suicid* OR “Self harm” OR “self poisoning” OR “self cutting” OR “self inflicted wound*” OR “suicid*” OR “self mutilat*” OR “auto mutilat*” OR “self injur*” OR “self destruct*”) Results: 80141 | 2: TS=(“internet based intervention*” OR “web based intervention*” OR “online intervention*” OR “internet intervention*” ) Results: 4742 | 3: (TS=(“Telemedicine” OR “Medical Informatics” OR “Information Technology” OR “internet” OR “mobile” OR “web” OR “email” OR “e-mail” OR “online” OR “social media” OR “social network*” OR “website” OR “remote consultation” OR “mobile health” OR “m health” OR “mhealth” OR “telehealth” OR “tele-health” OR “e health” OR “ehealth”)) AND TS=(intervention*) Results: 97094 | 4: #2 OR #3 Results: 97094 | 5: TS=(“systematic review” OR “meta analysis” OR “scoping review” OR “research synthesis” OR “research integration” OR “data synthesis” OR “meta analys*” OR “meta analyz*” OR “meta analyt*” OR “metaanalys*” OR “metaanalyz*” OR “metaanalyt*” ) Results: 576549 6: #1 AND #4 AND #5 Results: 412 |

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC. 2023 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html . [Last updated on 2023 May 08] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannah Ritchie. and Max Roser. and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. Suicide. 2015 Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/suicide’ . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann JJ, Michel CA, Auerbach RP. Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: A systematic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:611–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sufrate-Sorzano T, Juárez-Vela R, Ramírez-Torres CA, Rivera-Sanz F, Garrote-Camara ME, Roland PP, et al. Nursing interventions of choice for the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour: The umbrella review protocol. Nurs Open. 2022;9:845–50. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arensman E, Scott V, De Leo D, Pirkis J. Suicide and suicide prevention from a global perspective. Crisis. 2020;41:S3–7. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2014. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779 . [Last accessed on 2014 Aug 17] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwyer A, de Almeida Neto A, Estival D, Li W, Lam-Cassettari C, Antoniou M. Suitability of text-based communications for the delivery of psychological therapeutic services to rural and remote communities: Scoping review. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8:e19478. doi: 10.2196/19478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreuze E, Jenkins C, Gregoski M, York J, Mueller M, Lamis DA, et al. Technology-enhanced suicide prevention interventions: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:605–17. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16657928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rassy J, Bardon C, Dargis L, Côté LP, Corthésy-Blondin L, Mörch CM, et al. Information and communication technology use in suicide prevention: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e25288. doi: 10.2196/25288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehtimaki S, Martic J, Wahl B, Foster KT, Schwalbe N. Evidence on digital mental health interventions for adolescents and young people: Systematic overview. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8:e25847. doi: 10.2196/25847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forte A, Sarli G, Polidori L, Lester D, Pompili M. The role of new technologies to prevent suicide in adolescence: A systematic review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:109. doi: 10.3390/medicina57020109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cliffe B, Tingley J, Greenhalgh I, Stallard P. mHealth interventions for self-harm: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e25140. doi: 10.2196/25140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franco-Martín MA, Muñoz-Sánchez JL, Sainz-de-Abajo B, Castillo-Sánchez G, Hamrioui S, de la Torre-Díez I. A systematic literature review of technologies for suicidal behavior prevention. J Med Syst. 2018;42:71. doi: 10.1007/s10916-018-0926-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen ME, Nicholas J, Christensen H. A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malakouti SK, Rasouli N, Rezaeian M, Nojomi M, Ghanbari B, Shahraki Mohammadi A. Effectiveness of self-help mobile telephone applications (apps) for suicide prevention: A systematic review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020;34:85. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.34.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melia R, Francis K, Hickey E, Bogue J, Duggan J, O’Sullivan M, et al. Mobile health technology interventions for suicide prevention: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e12516. doi: 10.2196/12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry Y, Werner-Seidler A, Calear AL, Christensen H. Web-based and mobile suicide prevention interventions for young people: A systematic review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25:73–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berrouiguet S, Baca-García E, Brandt S, Walter M, Courtet P. Fundamentals for future mobile-health (mHealth): A systematic review of mobile phone and web-based text messaging in mental health. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e135. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e176. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon V, Rajan TM, Sarkar S. Psychotherapeutic applications of mobile phone-based technologies: A systematic review of current research and trends. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:4–11. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.198956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melbye S, Kessing LV, Bardram JE, Faurholt-Jepsen M. Smartphone-based self-monitoring, treatment, and automatically generated data in children, adolescents, and young adults with psychiatric disorders: Systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e17453. doi: 10.2196/17453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawes-Wickwar S, McBain H, Mulligan K. Application and effectiveness of telehealth to support severe mental illness management: Systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5:e62. doi: 10.2196/mental.8816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huckvale K, Nicholas J, Torous J, Larsen ME. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental health conditions: Status and considerations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;36:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen H, Batterham PJ, O’Dea B. E-health interventions for suicide prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:8193–212. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110808193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarubbi S, Rogante E, Erbuto D, Cifrodelli M, Sarli G, Polidori L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile apps for monitoring and management of suicide crisis: A systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:5616. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: overviews of reviews. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version. 2020:6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faulkner G, Fagan MJ, Lee J. Umbrella reviews (systematic review of reviews) International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2022;15:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marx W, Veronese N, Kelly JT, Smith L, Hockey M, Collins S, et al. The dietary inflammatory index and human health: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1681–90. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan R Group RRCCaCR. Heterogeneity and Subgroup Analyses in Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Reviews: Planning the Analysis at Protocol Stage. Available from: https://cccrg.cochrane.org . [Last accessed on 2016 Dec] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi L, Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: Practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15987. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalton JE, Bolen SD, Mascha EJ. Publication bias: The elephant in the review. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:812–3. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Büscher R, Torok M, Terhorst Y, Sander L. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203933. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen M, Chan KL. Effectiveness of digital health interventions on unintentional injury, violence, and suicide: Meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23:605–19. doi: 10.1177/1524838020967346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmeckenbecher J, Rattner K, Cramer RJ, Plener PL, Baran A, Kapusta ND. Effectiveness of distance-based suicide interventions: Multi-level meta-analysis and systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2022;8:e140. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2022.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torok M, Han J, Baker S, Werner-Seidler A, Wong I, Larsen ME, et al. Suicide prevention using self-guided digital interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e25–36. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witt K, Spittal MJ, Carter G, Pirkis J, Hetrick S, Currier D, et al. Effectiveness of online and mobile telephone applications (‘apps’) for the self-management of suicidal ideation and self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:297. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1458-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu T, Hu D, Teng F, Mao J, Xu K, Han Y, et al. Effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27:2186–203. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1930073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4. Cochrane. 2023 Available from: https//:www.training.cochrane.org/handbook . [Last updated on 2023 Aug 22] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman JI, editor, editor. Basic Biostatistics for Medical and Biomedical Practitioners. 2nd. Elsevier Inc: Academic Press; 2019. Chapter 36 – Meta-analysis; pp. 621–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee W, Hotopf M. 10 – Critical appraisal: Reviewing scientific evidence and reading academic papers. In: Wright P, Stern J, Phelan M, editors. Core Psychiatry. 3rd. Oxford: W.B. Saunders; 2012. pp. 131–42. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Its causes and consequences. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hennessy EA, Johnson BT, Keenan C. Best practice guidelines and essential methodological steps to conduct rigorous and systematic meta-reviews. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2019;11:353–81. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hossain MM, Nesa F, Das J, Aggad R, Tasnim S, Bairwa M, et al. Global burden of mental health problems among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114814. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]