Abstract

Experience of childhood trauma, especially physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, carries a risk for developing alcohol use disorder (AUD) and engaging in risky behaviors that can result in HIV infection. AUD and HIV are associated with compromised self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) possibly intersecting with childhood trauma. To determine whether poor HRQoL is heightened by AUD, HIV, their comorbidity (AUD + HIV), number of trauma events, or poor resilience, 108 AUD, 45 HIV, 52 AUD + HIV, and 67 controls completed the SF-21 HRQoL, Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), Ego Resiliency Scale (ER-89), and an interview about childhood trauma. Of the 272 participants, 116 reported a trauma history before age 18. Participants had a blood draw, AUDIT questionnaire, and interview about lifetime alcohol consumption. AUD, HIV, and AUD + HIV had lower scores on HRQoL and resilience composite comprising the BRS and ER-89 than controls. Greater resilience was a significant predictor of better quality of life in all groups. HRQoL was differentially moderated in AUD and HIV: more childhood traumas predicted poorer quality of life in AUD and controls, whereas higher T-lymphocyte count contributed to better quality of life in HIV. This study is novel in revealing a detrimental impact on HRQoL from AUD, HIV, and their comorbidity, with differential negative contribution from trauma and beneficial effect of resilience to quality of life. Channeling positive effects of resilience and reducing the incidence and negative impact of childhood trauma may have beneficial effects on health-related quality of life in adulthood independent of diagnosis.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, Alcohol use disorder, HIV infection, Comorbidities, Resilience, Quality of life

1. Introduction

Trauma during childhood, especially physical, emotional and sexual abuse, carries a heightened risk for later-life engagement in hazardous behaviors, including alcohol misuse and unsafe sex with the potential of acquiring HIV infection (HIV) (Patock-Peckham et al., 2020; Troeman et al., 2011). Indeed, the prevalence of childhood trauma in adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) or HIV is high. A recent epidemiological study of participants (n = 2064) in the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study born in England and Wales in 1994–5 found that 31% reported being exposed to a significant trauma by age 18; 16% of these trauma-exposed participants also had a history of alcohol dependence by age 18 (Lewis et al., 2019). A systematic literature review established that the rate of childhood maltreatment in those with HIV infection was higher than that of the general population; rates of childhood sexual abuse alone in those with HIV ranged from 32% to 76% (Spies et al., 2012). Comorbidity of childhood trauma and alcohol dependence is associated with a more severe clinical profile and a poorer treatment outcome than those with trauma or alcohol dependence alone (Brady and Back, 2012). Similarly, co-occurrence of HIV infection and childhood trauma have negative effects on mental health, HIV-related treatment outcome, and longevity (LeGrand et al., 2015; Pence, 2009; Young-Wolff et al., 2019). The detrimental effects of trauma and their relationship to the emergence of AUD and acquisition of HIV result in substantial personal and societal economic costs (Bingham et al., 2021; Gelles and Perlman, 2012; Sacks et al., 2015). Consequently, identification of factors that modulate outcome, such as resilience, may enhance preventative efforts.

The construct of resilience has been a focus of study for years; however, there is no single agreed upon operational definition (Luthar and Chicchetti, 2000; Vella and Pai, 2019). Southwick and Charney (2012) refer to resilience as a multidimensional construct, defined as an individual’s ability to bounce back from hardship and trauma. Resilience has also been defined as healthy adaptation in the face of threat or adversity or the ability to bounce back from stress having positive influences on health and well-being across the lifespan (Windle et al., 2011). Increasing interest in the study of resilience from policy makers, funding entities, and practitioners (Smith et al., 2008) has prompted research into understanding how childhood trauma affects resilience, functional capacity, and health (Oral et al., 2016). Resilience is protective against the development of AUD (Long et al., 2017), AUD relapse (Yamashita and Yoshioka, 2016), acquisition of HIV infection (McNair et al., 2018), and progression of HIV to AIDS (Liboro et al., 2021). Furthermore, resilience is related to outcome, such as symptom development in AUD (Sheerin et al., 2021), and medication adherence and immune functioning in HIV (Dulin et al., 2018). Resilience may play an especially protective role in reducing incidence of AUD (Cusack et al., 2021; Wingo et al., 2014) and HIV infection (Dale et al., 2015) in those with a history of childhood trauma.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional construct that provides information about functioning in the domains of emotional, cognitive, social, and physical performance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define health-related quality of life as “an individual’s or a group’s perceived physical and mental health over time;” health-related quality of life has been demonstrated to be a powerful predictor of morbidity and mortality [CDC; cdc.gov/hrqol/index.htm]. The concept of health-related quality of life, comprising subjective rating of cognitive functioning, emotional wellbeing, energy/fatigue, current health perceptions, pain, physical functioning, role functioning, and social functioning, is gaining traction as an essential primary and secondary endpoint in assessment of outcome in healthcare research and practice (Levola et al., 2014; Owczarek, 2010).

HRQoL assessments can inform disease prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation efforts, particularly in those with chronic conditions, such as childhood trauma (Edwards et al., 2004), AUD (Donovan et al., 2005; Longabaugh et al., 1994), and HIV (Alford et al., 2021). Several studies report an association between the construct of resilience and quality of life. Fumaz et al. (2015) reported that resilience “plays a fundamental role in well-being” in a sample of long-term diagnosed HIV-infected participants. More recently, Hopkins et al. (2022) reported that psychological resilience was an independent correlate of health-related quality of life in a sample of predominately African American adults with HIV.

A history of childhood trauma is associated with poorer overall quality of life in adulthood in clinical (Warshaw et al., 1993), non-clinical (Beilharz et al., 2020), and targeted population-based (Corso et al., 2008) samples. Data from recent population-based studies indicate that childhood maltreatment, particularly sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect, was associated with increased somatization and poorer physical HRQoL (Downing et al., 2021; Piontek et al., 2021). Further, more adverse childhood experiences correlated with poorer physical HRQoL, where physical HRQoL was both directly and indirectly related to adverse childhood experiences (Martin-Higarza et al., 2020). Although AUD was associated with poorer physical, cognitive, mental, and social HRQoL (Levola et al., 2014; Ugochukwu et al., 2013), physical HRQoL was not affected in a prospective observational study of treatment-seeking patients with AUD (Daeppen et al., 2014). Moreover, HRQoL was diminished even further by co-existing medical conditions, including HIV infection, with HRQoL reduction rates even greater than those associated with AUD alone.

Persons living with HIV infection without significant comorbidities may now have comparable life expectancies to those without HIV due in part to the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (Marcus et al., 2020). As individuals age with HIV, AUD, or their comorbidity, the chronic nature of these diseases, in conjunction with the long-term effects of childhood trauma, suggests that individuals must endure and cope with sequelae of these conditions for decades, making it critical to examine how disease burden and resilience affect HRQoL. For instance, irrespective of alcohol history, persons living with HIV infection who have experienced childhood trauma exhibit poorer verbal and visual memory in adulthood compared to their counterparts with HIV but without childhood trauma (Sassoon et al., 2017). Additionally, the comorbidity of AUD and HIV was associated with lower total HRQoL scores than those of either diagnosis alone. Poorer overall HRQoL was associated with current AUD rather than AUD in remission (regardless of HIV status), and poorer overall HRQoL was associated with depression in AUD, HIV, and their comorbidity (Rosenbloom et al., 2007).

Limited information is available regarding the role of resilience in persons with AUD and HIV who have experienced childhood trauma, and how frequency of trauma, resilience, and disease-related factors interact to affect overall HRQoL. To address these lacunae, this study had three aims: (1) to determine whether greater number of trauma events, poor resilience composite scores, and poor HRQoL scores were compounded by AUD + HIV comorbidity relative to single diagnosis or healthy controls; (2) to assess whether lower levels of resilience, measured by the resilience composite scores, and more trauma events experienced were independently associated with poorer HRQoL among AUD, HIV, and their comorbidity; and (3) to test the relationship of disease-related variables with trauma and resilience to AUD, HIV, and their comorbidity.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 272 study participants included 108 individuals with AUD, 45 with HIV, 52 with AUD + HIV comorbidity, and 67 with neither diagnosis (controls, CTL) (Table 1 for demographic information and statistics). Participants were recruited from the greater San Francisco Bay area through outreach at transitional sober living environments, community treatment programs, support group meetings, or community functions such as AIDS Walk, referrals from medical centers, response to flyers or Internet postings, or through word of mouth and were part of a larger ongoing longitudinal study on the effects of HIV infection and alcohol use on brain structure and function.

Table 1.

Demographics of the four groups (N = 272).

| AUD | HIV | AUD + HIV | CTL | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % or Mean (SD) | % or Mean (SD) | % or Mean (SD) | % or Mean (SD) | ||

| n = | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

| BACKGROUND DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| Sex (% Men) | 71.30% | 71.11% | 61.54% | 52.24% | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity (% Non-Cau.) | 60.19% | 46.67% | 84.62% | 46.97% | <0.001 [AUD + HIV > AUD, HIV, CTL] |

| Age | 53.56 (9.46) | 57.52 (7.80) | 57.20 (6.16) | 56.28 (11.59) | 0.03 [pairwise comparisons not sig.] |

| Median Age; Age Range | 55; 26–76 | 57; 39–78 | 57; 44–79 | 56; 27–87 | |

| Education (yrs) | 13.25 (2.67) | 13.80 (2.39) | 13.42 (2.17) | 16.07 (2.33) | <0.001 [CTL > AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES)a | 42.67 (16.41) | 37.89 (15.22) | 41.90 (13.72) | 25.72 (11.62) | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

| Lifetime Drug Abuse (%) | 72.90% | 46.67% | 71.15% | 1.47% | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

| Drug Abuse Remission (months)b | 124 ± 131; 72 | 131 ± 134; 98 | 117 ± 125; 69 | – | 0.92 (CTL not incl.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CHILDHOOD TRAUMA HISTORY | |||||

| Childhood Trauma History (%) | 48.15% | 42.22% | 51.92% | 26.87% | 0.02 [CTL < AUD, AUD + HIV] |

| Childhood Trauma Age of Onset | 8.75 (4.77) | 8.43 (5.23) | 9.52 (4.95) | 8.12 (4.69) | 0.79 |

| Number of Childhood Trauma Eventsc,b | 90 (115); 29 | 111 (127); 99 | 84 (127); 3 | 60 (85); 12 | 0.61 |

| Participants by Number of Trauma Events | 1 trauma: 12 | 1 trauma: 5 | 1 trauma: 11 | 1 trauma: 5 | |

| 2–99 traumas: 21 | 2–99 traumas: 6 | 2–99 traumas: 6 | 2–99 traumas: 9 | ||

| >100 traumas: 19 | > 100 traumas: 8 | >100 traumas: 10 | >100 traumas: 4 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AUD-RELATED DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| AUD Age of Onset | 26.01 (9.97) | – | 23.87 (8.94) | – | 0.19 |

| AUD Sobriety (months)b | 8.90 (27.00); 2.00 | – | 16.11 (43.27); 0.20 | – | 0.27 |

| AUDIT Score | 18.14 (11.24); 20 | 1.98 (2.01); 1 | 9.31 (10.07); 4.5 | 1.97 (1.67); 2 | <0.001 [(C=HIV) < ALC < ALC + HIV] |

| Lifetime Alcohol Consumption (kg)b | 1284 (971); 977 | 80 (108); 41 | 1034 (985); 726 | 38 (53); 14 | <0.001 [(CTL=HIV) < (ALC = ALC + HIV)] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HIV-RELATED DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| HIV Age of Onset | – | 35.69 (9.51) | 35.71 (8.18) | – | 0.99 |

| Length of time with HIV (years) | – | 21.17 (8.61) | 21.69 (6.21) | – | 0.79 |

| AIDS Status (%) | – | 58.14% | 62.00% | – | 0.71 |

| HAART Medications (%) | – | 88.37% | 96.00% | – | 0.24 |

| Log Viral Load | – | 2.02 (1.04) | 1.99 (1.06) | – | 0.89 |

| CD4 T Lymphocyte Countb | – | 569 (262); 514 | 617 (350); 604 | – | 0.48 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RESILIENCE MEASURES | |||||

| Resilience Composite Score (z-score) | −0.21 (0.82) | −0.08 (0.89) | −0.15 (0.85) | 0.55 (0.66) | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

| ER-89 | 41.25 (7.68) | 43.11 (8.46) | 43.20 (8.53) | 47.00 (5.51) | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

| BRS | 21.44 (4.68) | 21.62 (5.07) | 20.82 (4.52) | 25.32 (4.04) | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE | |||||

| HRQoL Score | 72.82 (17.08) | 73.68 (15.99) | 68.01 (18.66) | 86.95 (9.70) | <0.001 [CTL < AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV] |

Lower value = higher SES.

Mean (SD); median.

For those with trauma history.

2.2. Procedures

This study abided by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of SRI International (Advarra FWA00023875; SRI FWA00007933) and Stanford University (FWA00000935). All participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation and received modest monetary stipends for participation. See Supplemental Material for eligibility criteria and full descriptions of procedures for clinical diagnosis and resilience measures.

2.2.1. Clinical assessment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) history

All 272 participants underwent psychiatric and substance use assessment by senior clinical research staff using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 (SCID) (First et al., 2002, 2015) to establish lifetime DSM-IV-TR criteria for alcohol dependence/abuse or DSM-5 AUD. Estimation of lifetime alcohol consumption was obtained with a semi-structured lifetime alcohol history interview in all but 2 participants (Skinner, 1982; Skinner and Sheu, 1982). All participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor et al., 2001), a 10-item screening instrument to identify hazardous alcohol consumption.

2.2.2. HIV infection status

Hematological analysis confirmed HIV status with an antibody test and yielded CD4 T lymphocyte counts and viral load parameters.

2.2.3. Childhood trauma interview

Historical childhood trauma information was collected by senior clinical research staff through a customized in-person interview following Turner and Lloyd (2004). Individuals with a history of childhood trauma endorsed experiencing at least 1 of 13 types of life traumas before the age of 18 (Sassoon et al., 2017; Turner and Lloyd, 2004). All 272 participants completed the trauma interview; 116 reported experiencing at least 1 life trauma before age 18 years. For each type of reported trauma, the participant estimated the number of times that type of trauma occurred [max score per trauma type was 99 (too many to count)]; trauma types were then summed to yield a total number of childhood life trauma events experienced for each participant.

2.2.4. Resilience measures

Two resilience measures were administered to 264 of the 272 participants: Ego Resiliency Scale [ER-89 (Block and Kremen, 1996)] and Brief Resilience Scale [BRS (Smith et al., 2008)]. Given the high correlation of the ER-89 and the BRS scores (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) among the total group and among the CTL, AUD, HIV and AUD + HIV groups individually (all p’s < 0.004), the ER-89 and BRS scores were combined to produce a resilience composite score. Individual scores for each measure were converted to z-scores, and the mean of the two scores was used as a resilience composite score.

2.2.5. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

The SF-21 (Bozzette et al., 1995), derived from the Short Form (SF-36) of the Medical Outcome Study (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992), is widely used (Alford et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2016) and evaluated HRQoL herein. The SF-21 is a 21-item questionnaire, yielding a total score representing current self-reported quality of life in eight areas: cognitive functioning, emotional well-being, energy/fatigue, current health perceptions, pain, physical functioning, role functioning, and social functioning. A standardized total score ranging from 0 (poor quality of life) to 100 (excellent quality of life) was calculated, reflecting self-rating of coping in these 8 combined functional areas of life (cf, (Rosenbloom et al., 2007)).

2.3. Statistical analyses

2.3.1. Demographic analyses

Initial one-way ANOVAs, Kruskal-Wallis, t-tests, Mann-Whitney U, and chi-square tests compared demographic variables, including percentage of those with a history of childhood trauma in the four groups: AUD, HIV, AUD + HIV, and CTL.

2.3.2. Analyses of study aims

Aim 1:

To examine whether more trauma events, poor resilience, and poor HRQoL were compounded in AUD + HIV compared to single-diagnosis groups or the CTL group, one-way ANOVAs compared number of childhood traumas, resilience composite scores, and HRQoL scores among the four groups. Tukey HSD tests for multiple comparisons were conducted to follow-up significant ANOVA results.

Aims 2 & 3:

To assess whether lower levels of resilience, measured by the resilience composite scores, and more trauma events experienced were independently associated with poorer HRQoL among AUD, HIV, and their comorbidity, and to determine which disease-related variables contributed to HRQoL scores, Pearson correlations and simultaneous multiple regressions were conducted for each group. Pearson correlations tested significance of all potential regression variables selected to be studied, i.e., the resilience composite scores, number of childhood trauma events, disease-related variables (the AUDIT score and lifetime alcohol consumption for all participants and CD4 T-lymphocyte count and HIV log viral load for participants with HIV infection), and demographic variables (age, sex, and SES which incorporates education) on HRQoL scores among all four participant groups, with α = 0.05, to determine which were significant. For each group, only the variables that were significantly correlated with HRQoL scores were entered as variables in simultaneous multiple regressions. A conservative correction of α = 0.013 was used to protect against family-wise error in main analyses (ANOVAs and regressions).

All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27 (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and trauma among groups

Among those reporting trauma, the numbers of trauma events reported were comparable across all four groups. Further, in all groups, those with trauma history had similar trauma age of onset (~8–9 years old). Those with AUD history (AUD, AUD + HIV) had similar mean AUD age of onset (mid-20s), and those with HIV infection had similar mean HIV infection age of onset (mid-30s). For individuals who were comorbid with AUD and HIV infection and who experienced trauma, the typical timeline was, first, experiencing a childhood trauma, followed by onset of AUD, followed by acquisition of HIV.

In the AUD and AUD + HIV groups, history of childhood trauma occurred before the onset of the alcohol diagnosis in all but one case. Similarly, HIV participants reporting childhood trauma experienced those events before learning of their HIV seropositive status. Trauma types endorsed are presented in Table 2. Fewer CTLs reported childhood trauma than the two AUD groups (AUD and AUD + HIV); age of trauma onset, for those who did report experiencing a traumatic event, was statistically similar across the four groups. The types of traumas most likely to be endorsed were related to physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and were of similar proportions among the four groups (73.1% in AUD, 85.7% in HIV, 70.4% in AUD + HIV, and 76.5% in CTL), [χ2 (3) = 1.72, p = 0.63].

Table 2.

Incidence of types of childhood life traumas reported by participants with a history of trauma (N = 116 of 272).

| Types of Childhood Life Traumas | AUD | HIV | AUD + HIV | CTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| with Trauma | with Trauma | with Trauma | with Trauma | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (n = 52 of 108) | (n = 19 of 45) | (n = 27 of 52) | (n = 18 of 67) | |

|

| ||||

| Lost home in natural disaster | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Life threatening accident, injury, illness | 6 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (15%) | 1 (6%) |

| Forced sexual intercourse | 8 (15%) | 3 (16%) | 11 (41%) | 3 (17%) |

| Forced sexual touching | 15 (29%) | 3 (16%) | 10 (37%) | 7 (39%) |

| Physical abuse by parent/guardian | 20 (38%) | 9 (47%) | 9 (33%) | 7 (39%) |

| Physical abuse by boyfriend/girlfriend | 2 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (11%) | 2 (11%) |

| Physical abuse by someone else | 5 (10%) | 2 (11%) | 4 (15%) | 5 (28%) |

| Physically assaulted or mugged | 6 (12%) | 3 (16%) | 6 (22%) | 2 (11%) |

| Emotional abuse by parent/guardian | 25 (48%) | 11 (58%) | 8 (30%) | 9 (50%) |

| Threatened with weapon/shot at (no injury) | 10 (19%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Injured with weapon or shot at | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chased by someone where thought could get hurt | 17 (33%) | 2 (11%) | 9 (33%) | 4 (22%) |

| Car crash where someone was killed/badly injured | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (11%) | 3 (17%) |

3.2. Aim 1: diagnostic group differences in trauma events, resilience composite scores, and HRQoL scores

The mean number of childhood trauma events did not differ among the groups [F (3, 112) = 0.61, p = 0.61]. The majority of the specific childhood trauma events experienced in all groups was related to physical, sexual, and emotional abuse compared to other types of trauma such as illness, natural disasters, severe accidents, or weapons-related violence. In most cases, traumas were ongoing through childhood rather than an infrequent occurrence.

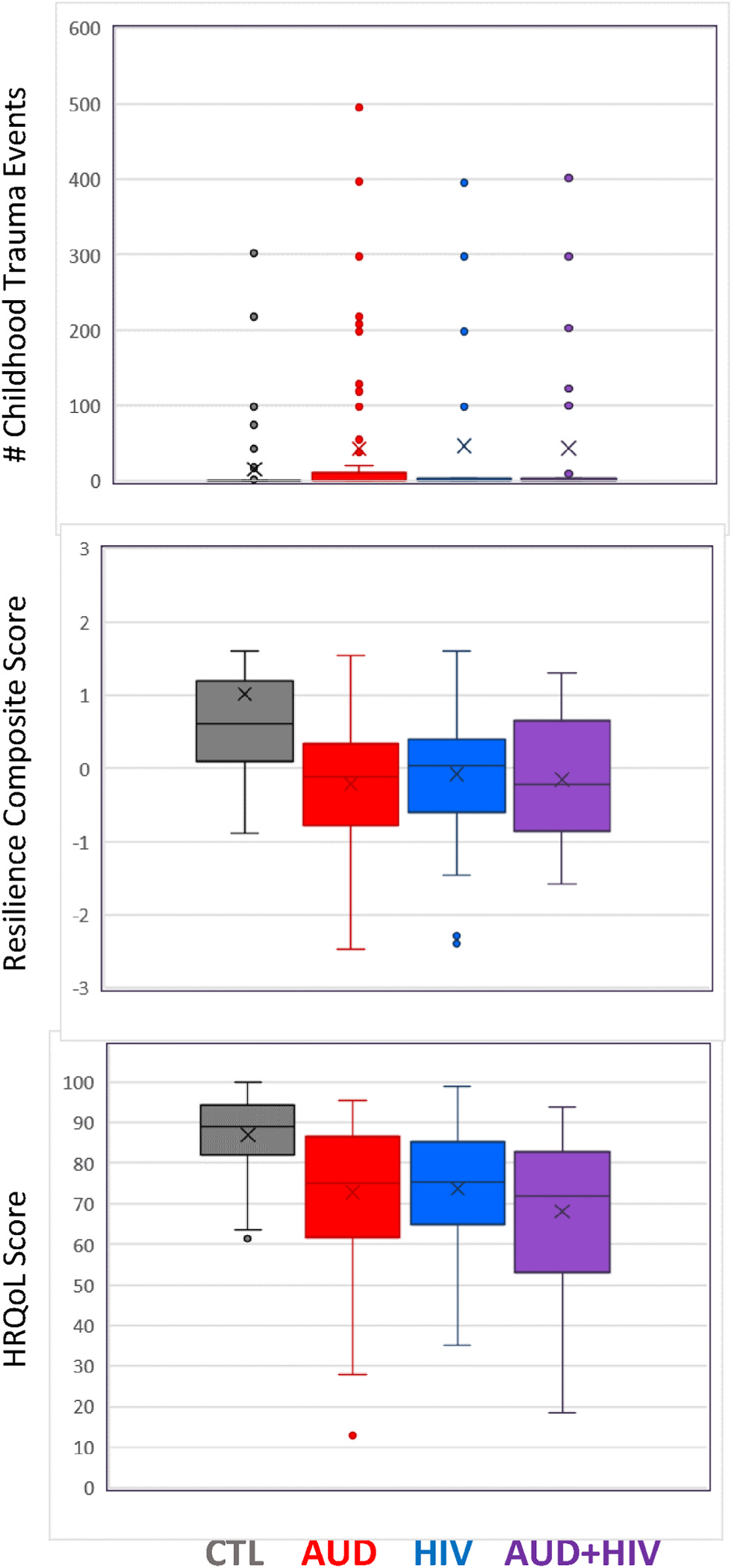

To determine whether resilience composite scores and HRQoL were differentially affected in AUD + HIV than in either single diagnosis or CTL, ANOVAs compared the four diagnostic groups (Fig. 1). For all clinical groups (AUD, HIV, and AUD + HIV), mean resilience composite scores were significantly lower (all p’s < 0.001) than the mean for CTL [F (3, 260) = 12.93, p < 0.001]. Similarly, mean HRQoL scores for AUD, HIV, and AUD + HIV were all significantly lower (all p’s < 0.001) than the mean for CTL [F (3, 268) = 16.97, p < 0.001]. Although the mean HRQoL score in the AUD + HIV group was numerically lower than those of AUD and HIV, group differences were not statistically significant. Results did not change when controlling for group differences in demographics, i.e., sex, ethnicity, age, and SES (which incorporates education).

Fig. 1.

Mean comparisons of HRQoL scores, number of childhood trauma events, and resilience composite scores among the CTL, AUD, HIV, and AUD + HIV groups.

Comparison of those in the clinical groups with history of substance use disorder (including cocaine, opioids, sedatives, stimulants, hallucinogens) to those without showed no significant differences in HRQoL [F (1, 197) = 2.29, p = 0.13], resilience composite score [F (1, 194) = 0.621, p = 0.43], or number of trauma events [F (1, 197) = 0.97, p = 0.33].

3.3. Aims 2 & 3

3.3.1. Correlations of regression predictor variables with HRQoL scores

Next, we explored whether poorer resilience, a greater number of childhood trauma events, and poorer disease-related variables predicted poorer HRQoL scores in ALC, HIV, and AUD + HIV. Simple correlations (Table 3), as a preamble to regressions, were conducted between resilience composite scores, number of childhood trauma events, disease-related factors (AUDIT score, lifetime alcohol consumption, CD4 T lymphocyte count, HIV log viral load), and demographic variables (sex, age, and SES) against HRQoL scores within each of the four groups to determine which variables were significantly associated with HRQoL score; those variables were entered into regression models to predict HRQoL score of each group. Intercorrelations of independent variables for each group appear in Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Table 3.

Correlations of resilience, disease-related, and demographic variables with HRQoL scores.

| AUD | HIV | AUD + HIV | CTL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| — Health-Related Quality of Life Score — | |||||

|

|

|

||||

| Variables | |||||

|

| |||||

| Sex | r | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.23 | −0.07 |

| p-value | 0.18 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.57 | |

| n | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age | r | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 | −0.08 |

| p- value | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.54 | |

| n | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Socioeconomic Scale (Lower score = Higher SES) | r | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.21 | −0.05 |

| p- value | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.68 | |

| n | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of Childhood Trauma Events | r | −0.31 | 0.15 | −0.11 | −0.39 |

| p- value | 0.001 | 0.32 | 0.44 | <0.001 | |

| n | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Resilience Composite Score | r | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| p- value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 | <0.001 | |

| n | 107 | 45 | 50 | 62 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AUDIT Score | r | −0.20 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| p- value | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.92 | |

| n | 108 | 45 | 52 | 67 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lifetime Alcohol Consumption (kg) | r | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 |

| p- value | 0.26 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.66 | |

| n | 107 | 45 | 52 | 66 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CD4 T Lymphocyte Count | r | 0.35 | 0.01 | ||

| p- value | N/A | 0.03 | 0.96 | N/A | |

| n | 37 | 46 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Log Viral Load | r | 0.01 | 0.12 | ||

| p- value | N/A | 0.96 | 0.45 | N/A | |

| n | 35 | 43 | |||

Based on these correlational analyses, the resilience composite score was entered into regressions predicting HRQoL in all four groups. Number of childhood trauma events was entered into regressions predicting HRQoL of AUD and CTL. AUDIT score was entered as a predictor of HRQoL in AUD, whereas CD4 T lymphocyte count was entered as a predictor of HRQoL in HIV. None of the demographic variables were entered into any of the regressions, as none were significant predictors of HRQoL in any group.

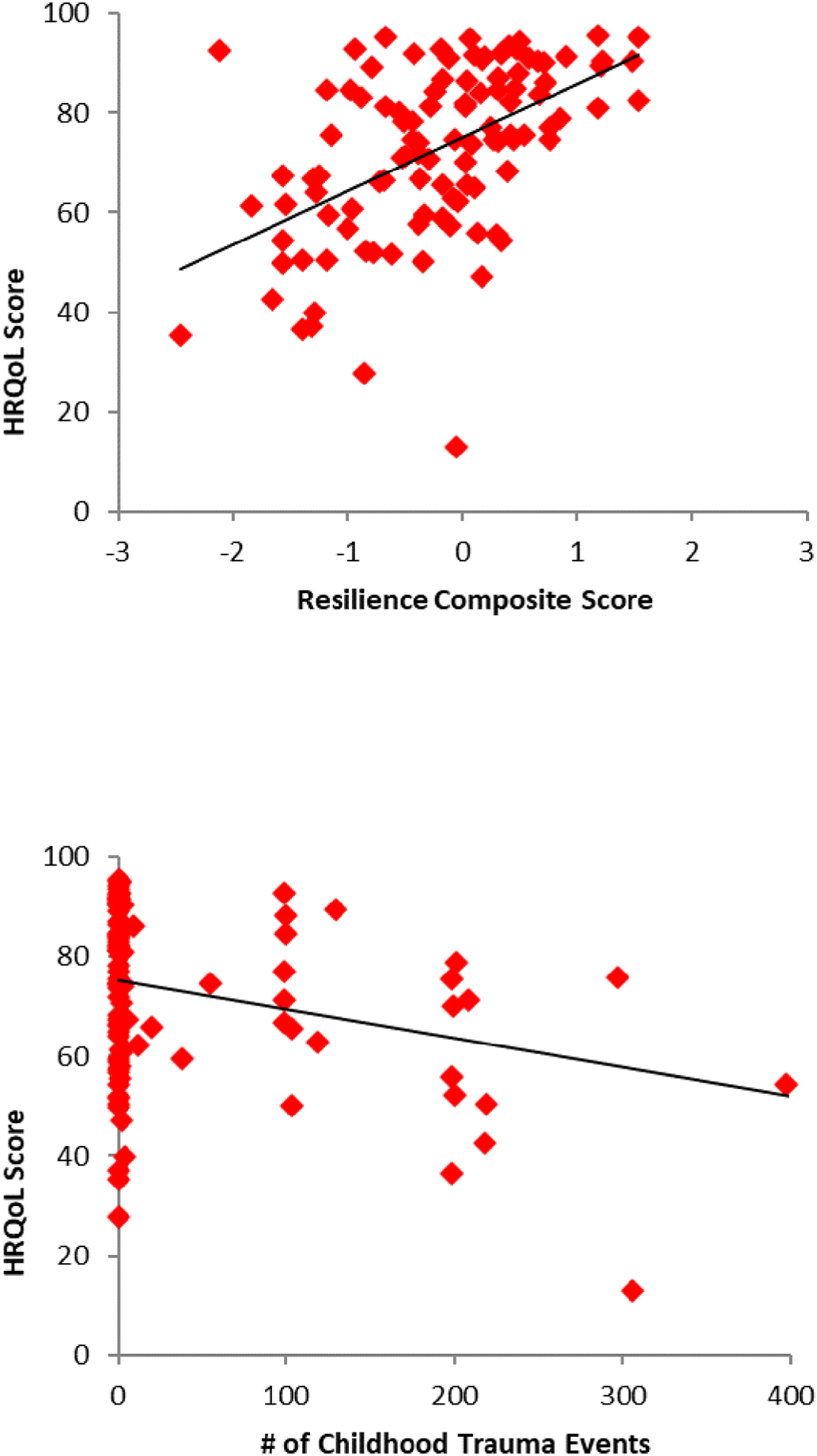

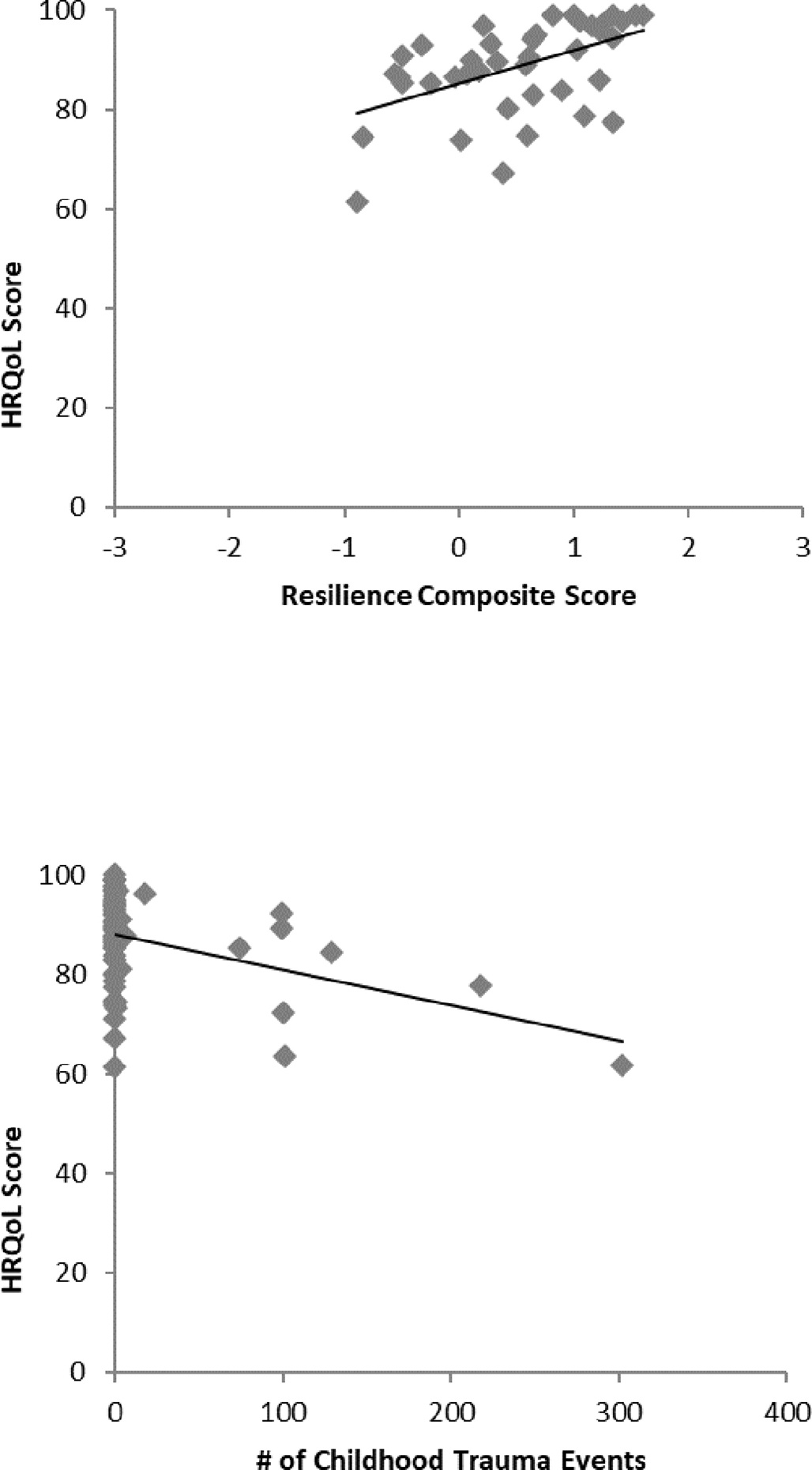

3.4. Multiple regression predicting HRQoL score in AUD

In AUD, multiple regression determined the best linear combination of resilience composite score, number of childhood trauma events, and AUDIT score for predicting HRQoL (Table 4 for statistics). The model was significant, with 30% of the variance of HRQoL scores in AUD explained by the model. Two of the three variables were significant predictors. The resilience composite contributed the most to the prediction of HRQoL score (Table 4, and Fig. 2 for correlation plot), with higher resilience predicting greater HRQoL, and number of childhood trauma events predicting a poorer HRQoL score.

Table 4.

Multiple regressions predicting HRQoL in each subject group.

| Predicting HRQoL in the AUD Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Coefficients | Beta | t-value | p-value |

|

| |||

| Resilience Composite Score | 0.47 | 5.53 | <0.001 |

| # Trauma Events | −0.23 | −2.74 | 0.01 |

| AUDIT Score | −0.04 | −0.49 | 0.63 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F (3,103) = 16.20 | R2 = 0.32 | Adjusted R2 = 0.30 | p<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Predicting HRQoL in the HIV Group | |||

| Coefficients | Beta | t-value | p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

| Resilience Composite Score | 0.55 | 4.26 | <0.001 |

| CD4 T Lymphocyte Count | 0.34 | 2.64 | 0.01 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F (2,34) = 12.72 | R2 = 0.43 | Adjusted R2 = 0.39 | p<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Predicting HRQoL in the AUD + HIV Group | |||

| Coefficients | Beta | t-value | p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

| Resilience Composite Score | 0.37 | 2.72 | 0.01 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F (1,48) = 7.42 | R2 = 0.13 | Adjusted R2 = 0.12 | p=0.01 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Predicting HRQoL in the Control Group | |||

| Coefficients | Beta | t-value | p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

| Resilience Composite Score | 0.48 | 4.76 | <0.001 |

| # Trauma Events | −0.41 | −4.15 | <0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

| F (2, 59) = 20.73 | R2 = 0.41 | Adjusted R2 = 0.39 | p<0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Correlations of resilience composite scores (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), number of childhood trauma events (r = −0.31, p = 0.001) and HRQoL in the AUD group.

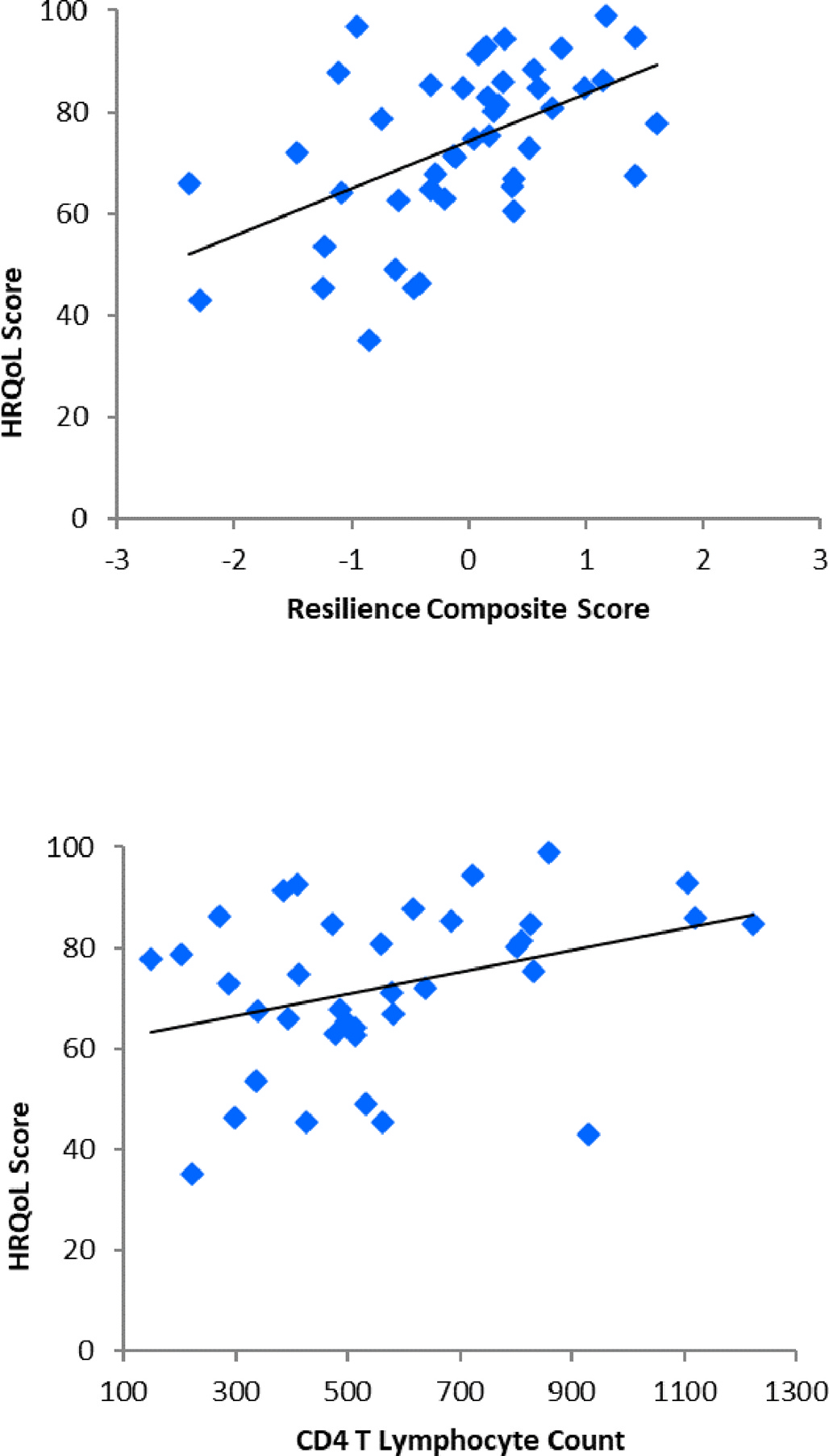

3.5. Multiple regression predicting HRQoL in HIV

Resilience composite score and CD4 T lymphocyte count were entered into the regression model predicting HRQoL score in HIV. Both predictors were significant, with 39% of the variance in HRQoL in the HIV group explained by the model. Higher resilience composite score predicted better HRQoL in HIV. Further, a greater number of CD4 T lymphocytes predicted greater HRQoL (Table 4, and Fig. 3 for correlation plot).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of resilience composite scores (r = 0.52, p < 0.001), CD4 T lymphocyte count (r = 0.35, p = 0.03) and HRQoL in the HIV group.

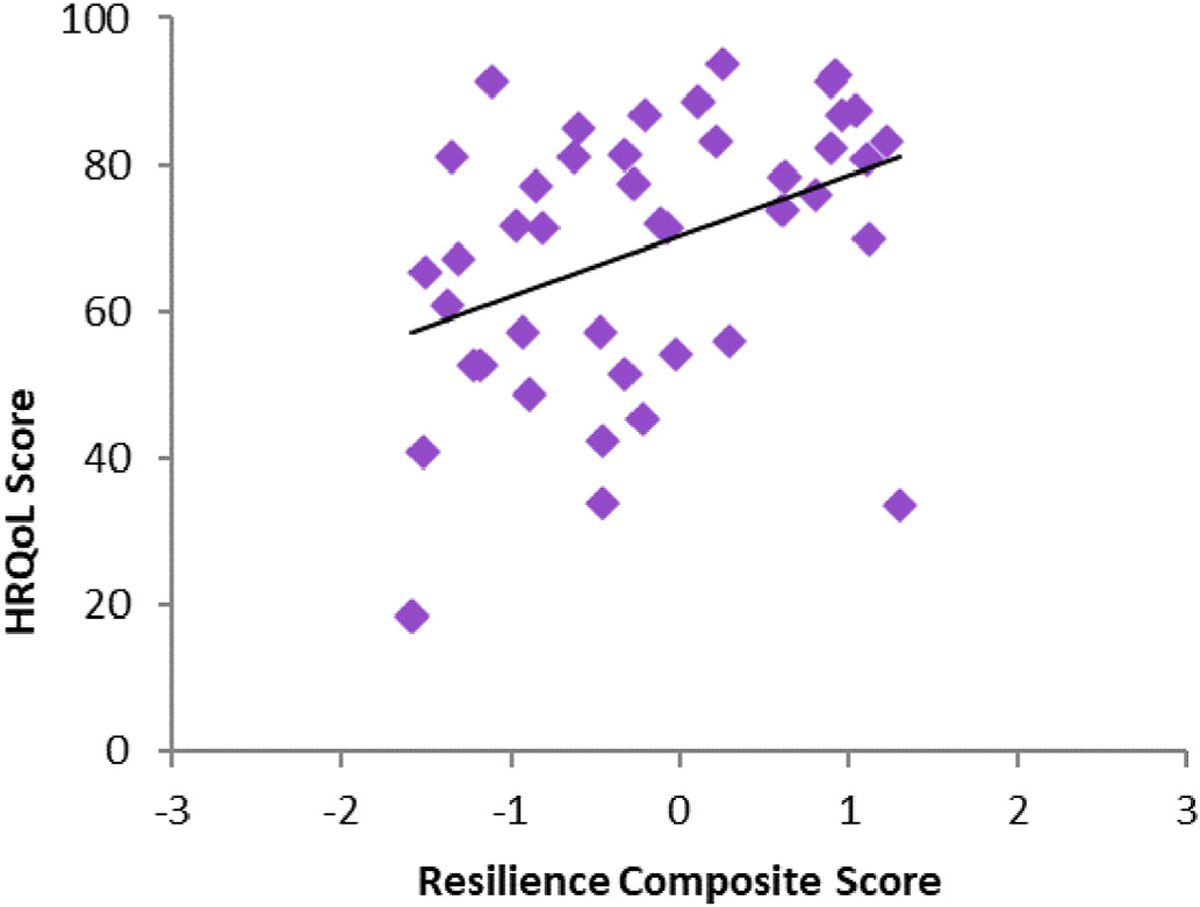

3.6. Multiple regression predicting HRQoL in AUD + HIV

In predicting HRQoL score in the AUD + HIV group, only one variable, resilience composite score, was entered into the regression. Higher resilience composite scores predicted greater HRQoL, with 12% of the variance in HRQoL score accounted (Table 4, and Fig. 4 for correlation plot).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of resilience composites scores (r = 0.37, p = 0.009) and HRQoL in the AUD + HIV group.

3.7. Multiple regression predicting HRQoL in CTL

Resilience composite score and number of childhood trauma events were entered into the regression predicting HRQoL score in CTL. Both variables were significant predictors, accounting for 39% of the variance. A greater number of trauma events was associated with poorer HRQoL scores. Further, higher resilience composite scores predicted greater HRQoL in CTL (Table 4, and Fig. 5 for correlation plot).

Fig. 5.

Correlations of resilience composite scores (r = 0.49, p < 0.001), number of childhood trauma events (r = −0.39, p < 0.001), and HRQoL in the CTL group.

4. Discussion

This study examined how frequency of childhood trauma and resilience affects health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in persons with AUD and HIV infection. Trauma, AUD, and HIV comprise a “trimorbidity” that has been rarely studied despite evidence that trauma during childhood increases risk of AUD and HIV infection (Patock-Peckham et al., 2020; Troeman et al., 2011).

The clinical groups (AUD, HIV, and AUD + HIV) rated their overall HRQoL more poorly than did controls regardless of history of childhood trauma, supporting earlier findings (Rosenbloom et al., 2007); however, a compounded effect of AUD and HIV comorbidity was not observed. Nonetheless, our findings of poorer levels of resilience among the three clinical groups compared to controls were consistent with previous reports (Long et al., 2017; Sanchez et al., 2022; Sheerin et al., 2021), with all groups experiencing a similar number of childhood trauma events and types of trauma.

Our results suggest that resilience plays a critical role as one overarching factor in independently predicting HRQoL well-being in adulthood, being the most salient contributor in this study. Indeed, greater resilience, shown previously to be associated with lower levels of self-reported depression (Spies and Seedat, 2014), consistently predicted health-related quality of life in all four groups.

In addition, a greater number of childhood trauma events, of which recurring physical, sexual, or emotional abuse were the most commonly reported, independently predicted detrimental effects on HRQoL in both the AUD group and control group. This finding is consistent with a recent report of a dosage effect of childhood adversity on quality of life (Martin-Higarza et al., 2020), and now extends this to individuals with AUD.

This study is novel in showing a detrimental impact of AUD and HIV infection on HRQoL even in individuals with HIV or AUD + HIV who were in disease remission. A meta-analysis reported that alcohol consumption promotes worsening of HIV/AIDS symptoms and negatively affects support-seeking (Shuper et al., 2010). Our participants who were comorbid for HIV infection and AUD were high alcohol consumers over their lifetime, and had a mean total lifetime consumption equivalent to AUD, with relatively comparable sobriety lengths. Although more than 50% of participants with HIV infection in our study (HIV, AUD + HIV) had a history of an AIDS-defining event, they had low viral loads, relatively healthy T lymphocyte counts (>500 cells/mm3), were almost all on HAART medications, and were ostensibly unimpaired functionally as indicated by high Karnofsky scores. Regardless of the temporal separation of contributing factors (trauma occurring during childhood, whereas AUD history was more recent, and HIV infection was considered stable), trauma, AUD, and HIV infection histories all had significant detrimental effects on quality of life.

Disease-related variables also demonstrated an association with self-reported quality of life. Higher T lymphocyte count was associated with better HRQoL in individuals with HIV, recognizing the relevance of a healthier immune system to quality of life in those with HIV. While higher AUDIT scores were related to poorer HRQoL in AUD, AUDIT scores were not a significant independent predictor of HRQoL. Neither alcohol-related variable (AUDIT score or amount of lifetime alcohol consumed) was related to HRQoL in AUD + HIV; this may be due to differences in AUD characteristics between the AUD groups, i.e., lower severity and lower variability in AUDIT scores in AUD + HIV than AUD alone.

These results highlight resilience as a potential target for interventions in people with significant adverse life experiences such as history of childhood trauma, AUD, or HIV, or as a target for prevention for at-risk populations. Indeed, resilience can be modified and enhanced neurobiologically and behaviorally toward improving clinical outcomes (Wu et al., 2013). Relevantly, one study reported that an intervention aimed at building psychosocial resilience was associated with improved self-esteem and decreased distress in men with HIV infection who later decreased HIV-associated risk behaviors (Safren et al., 2021).

Taken together, our findings are consistent with reports that AUD, HIV, and childhood trauma have negative effects on quality of life, whereas resilience can offer a protective effect (Long et al., 2017).

4.1. Limitations

Given its cross-sectional design, neither change in HRQoL nor assessment of whether childhood trauma disrupted normal development could be determined. Traumas that occurred throughout childhood and adolescence were considered together without reference to potential differential effects relative to specific developmental periods (Hambrick et al., 2019). In addition, although we had a control group, a smaller proportion of control than clinical participants reported having a childhood trauma history. Further, we did not examine a group of individuals specifically diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); only 11 of our 117 participants with a childhood trauma history met criteria to receive a diagnosis of PTSD. By volunteering to be part of a research study, our participants may have had higher levels of resilience and lower levels of depression than may be typical in this population. Also, while the two measures of resilience used in this study, the BRS and the ER-89, were significantly correlated with each other in all groups, resilience is a complex construct and it is possible that the unique contributions of each measure in assessing resilience might be detectable in larger samples (Watters et al., 2023).

Further, group comparisons may be limited by differences in demographics across groups. The CTL group has a wider age range (although means and medians are similar among groups), and results may not generalize to younger or older individuals. Additionally, sex, ethnicity, and SES (which incorporated years of education) were significantly different across groups; although results did not change when accounting for these differences, comparison between groups may be limited by these differences.

5. Conclusion

This study examined whether a history of trauma experienced during childhood affected quality of life in middle-aged adults who had acquired AUD, HIV, or their comorbidity in adulthood and examined the potential role of resilience in HRQoL judgments. HRQoL has become a well-established and meaningful multidimensional outcome measure in healthcare research and practice, particularly in older adults (Fang et al., 2015) with real-world significance. The construct of resilience independently influenced HRQoL. History of childhood trauma, considered a pervasive public health crisis (Magruder et al., 2016), was reported by 43% of our total sample. Critically, the cascade of events that ultimately could lead to AUD and HIV infection in individuals who experience childhood trauma may be prevented by early identification and intervention (Brady and Back, 2012) targeting resilience (Safren et al., 2021). Prevention and intervention strategies in those at heightened risk for trauma, AUD, or HIV infection may be tailored to enhance resilience for better health-related quality of life, which can continue to be affected even in later life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA017347, AA005965, AA010723).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

None.

CRediT author statement

Stephanie A. Sassoon: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Formal acquisition, Project administration, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; Rosemary Fama: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing; Anne-Pascale Le Berre: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing; Eva M. Müller-Oehring: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing; Natalie M. Zahr: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review and editing; Adolf Pfefferbaum: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review and editing; Edith V. Sullivan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.05.033.

References

- Alford K, Daley S, Banerjee S, Vera JH, 2021. Quality of life in people living with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: a scoping review study. PLoS One 16 (5), e0251944. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro M, 2001. AUDIT. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Beilharz JE, Paterson M, Fatt S, Wilson C, Burton A, Cvejic E, Lloyd A, Vollmer-Conna U, 2020. The impact of childhood trauma on psychosocial functioning and physical health in a non-clinical community sample of young adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatr. 54 (2), 185–194. 10.1177/0004867419881206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham A, Shrestha RK, Khurana N, Jacobson EU, Farnham PG, 2021. Estimated lifetime HIV-related medical costs in the United States. Sex. Transm. Dis. 48 (4), 299–304. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J, Kremen AM, 1996. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 50 (2), 349–361. 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzette SA, Hays RD, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Wu AW, 1995. Derivation and properties of a brief health status assessment instrument for use in HIV disease. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 8, 253–265. 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, 2012. Childhood trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. 34 (4), 408–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, Mercy JA, 2008. Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. Am. J. Publ. Health 98 (6), 1094–1100. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack SE, Bountress KE, Sheerin CM, Spit for Science Work Group, Dick DM, Amstadter AB, 2021. The longitudinal buffering effects of resilience on alcohol use outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 29. 10.1037/tra0001156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeppen J-B, Faouzi M, Sanchez N, Rahhali N, Bineau S, Bertholet N, 2014. Quality of life depends on the drinking pattern in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Alcohol 49 (4), 457–465. 10.1093/alcalc/agu027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SK, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Kelso GA, Cruise RC, Brody LR, 2015. Resilience moderates the association between childhood sexual abuse and depressive symptoms among women with and at-risk for HIV. AIDS Behav. 19 (8), 1379–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D, Mattson ME, Cisler RA, Longabaugh R, Zweben A, 2005. Quality of life as an outcome measure in. alcoholism treatment research Journal on Studies of Alcohol S15, 119–139. 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing NR, Akinlotan M, Thornhill CW, 2021. The impact of childhood sexual abuse and adverse childhood experiences on adult health related quality of life. Child Abuse Negl. 120, 105181 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin AJ, Dale SK, Earnshaw VA, Fava JL, Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, Hogan JW, Carey MP, Howe CJ, 2018. Resilience and HIV: a review of the definition and study of resilience. AIDS Care 30, S6–S17. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1515470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, 2004. Adverse childhood experiences and health-related quality of life as an adult. In: Kendall-Tackett KA (Ed.), Application and Practice in Health Psychology. Health Consequences of Abuse in the Family: A Clinical Guide for Evidence-Based Practice. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Vincent W, Calabrese SK, Heckman TG, Sikkema KJ, Humphries DL, Hansen NB, 2015. Resilience, stress, and life quality in older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Aging Ment. Health 19 (11), 1015–1021. 10.1080/13607863.2014.1003287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. Research Version Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL, 2015. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 - Research Version (SCID-5 for DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Fumaz CR, Ayestaran A, Perez-Alvarez N, Muñoz-Moreno JA, Moltó J, Ferrer MJ, Clotet B, 2015. Resilience, ageing, and quality of life in long-term diagnosed HIV-infected patients. AIDS Care 27 (11), 1396–1403. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1114989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Perlman S, 2012. Estimated Annual Cost of Child Abuse and Neglect. Prevent Child Abuse America, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick EP, Brawner TW, Perry BD, Brandt K, Hofmeister C, Collins JO, 2019. Beyond the ACE score: examining relationships between timing of developmental adversity, relational health and developmental outcomes in children. Arch. Pediatr. Nurs. 33 (3), 238–247. 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins CN, Lee CA, Lambert CC, Vance DE, Haase SR, Delgadillo JD, Fazeli PL, 2022. Psychological resilience is an independent correlate of health-related quality of life in middle-aged and older adults with HIV in the Deep South. J. Health Psychol. 27 (13), 2909–2921. 10.1177/13591053211072430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand S, Reif S, Sullivan K, Murray K, Barlow ML, Whetten K, 2015. A review of recent literature on trauma among individuals living with HIV. Curr. HIV AIDS Rep. 12 (4), 397–405. 10.1007/s11904-015-0288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levola J, Aalto M, Holopainen A, Cieza A, Pitkanen T, 2014. Health-related quality of life in alcohol dependence: a systematic literature review with a special focus on the role of depression and other psychopathology. Nord. J. Psychiatr. 68 (6), 369–384. 10.3109/08039488.2013.852242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SJ, Arseneault L, Caspi A, Fisher HL, Matthews T, Moffitt TE, Odgers CL, Stahl D, Teng JY, Danese A, 2019. The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. Lancet Psychiatr. 6 (3), 247–256. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liboro R, Despres J, Ranuschio B, Bell S, Barnes L, 2021. Forging resilience to HIV/AIDS: personal strengths of middle-aged and older gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS. Am. J. Men’s Health 15 (5). 10.1177/15579883211049016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long EC, Lonn SL, Ji J, Lichtenstein P, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Kendler KS, 2017. Resilience and rist for alcohol use disorders: a Swedish twin study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 141 (1), 149–155. 10.1111/acer.13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Mattson ME, Connors GJ, Cooney NL, 1994. Quality of life as an outcome variable in alcoholism treatment research. J. Stud. Alcohol S12, 119–129. 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Chicchetti D, 2000. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 12 (4), 857–885. 10.1017/S0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Kassam-Adams N, Thoresen S, Olff M, 2016. Prevention and public health approaches to trauma and traumatic stress: a rationale and call to action. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 7, 1–9. 10.3402/ejpt.v7.29715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Alexeeff SE, Anderson AN, Hechter RC, Hu H, Lam JO, Towner WJ, Yuan Q, Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, 2020. Comparison of overall and comorbidity-free life expectancy between insured adults with and without HIV infection, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 3 (6), e207954. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Higarza Y, Fontanil Y, Mendez MD, Ezama E, 2020. The direct and indirect influences of adverse childhood experiences on physical health: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17 (22), 8507. 10.3390/ijerph17228507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair OS, Gipson JA, Denson D, Thompson DV, Sutton MY, Hickson DA, 2018. The associations of resilience and HIV risk behaviors among black gay, bisexual, other men who have sex with men (MSM) in the Deep South: the MARI study. AIDS Behav. 22 (5), 1679–1687. 10.1007/s10461-017-1881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral R, Ramirez M, Coohey C, Nakada S, Walz A, Kuntz A, Benoit J, Peek-Asa C, 2016. Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: the future of health. Pediatr. Res. 79 (1–2), 227–233. 10.1038/pr.2015.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owczarek K, 2010. The concept of quality of life. Acta Neuropsychol. 8 (3), 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Belton DA, D’Ardenne K, Tein J-Y, Bauman DC, Infurna FJ, Sanabria F, Curtis J, Morgan-Lopez AA, McClure SM, 2020. Dimensions of childhood trauma and their direct and indirect links to PTSD, impaired control over drinking, and alcohol-related problems. Addict. Behav. Rep. 23 (12) 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, 2009. The impact of mental health and traumatic life experiences on antiretroviral treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63 (3), 636–640. 10.1093/jac/dkp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontek K, Wiesmann U, Apfelbacher C, Volzke H, Grabe HJ, 2021. The association of childhood maltreatment, somatization and health-related quality of life in adult age: results from a population-based cohort study. Child Abuse Negl. 120, 105226 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Sullivan EV, Sassoon SA, O’Reilly A, Fama R, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Pfefferbaum A, 2007. Alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity: factors affecting self-rated health-related quality of life. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 68 (1), 114–125. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD, 2015. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 49 (5), E73–E79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Thomas B, Biello KB, Mayer KH, Rawat S, Dange A, Bedoya CA, Menon S, Anand V, Balu V, O’Cleirigh C, Klasko-Foster L, Baruah D, Swaminathan S, Mimiaga M, 2021. Strengthening resilience to reduce HIV risk in Indian MSM: a multi-city, randomised, clinical efficacy trial. Lancet Global Health 9, e446–e455. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Perez MG, Field CA, 2022. The role of resilience in alcohol use, drinking motives, and alcohol-related consequences among Hispanic college students. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 48 (1), 100–109. 10.1080/00952990.2021.1996584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon SA, Le Berre A-P, Fama R, Asok P, Hardcastle C, Chu W, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, 2017. Effects of childhood trauma and alcoholism history on neuropsychological performance in adults with HIV infection: an initial study. J. HIV/AIDS and Infect. Dis. 3, 1–15. 10.17303/jaid.2017.3.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheerin CM, Bountress KE, Hicks TA, Lind MJ, Aggen SH, Kendler KS, Amstadter AB, 2021. Longitudinal examination of the impact of resilience and stressful life events on alcohol use disorder outcomes. Subst. Use Misuse 56 (9), 1346–1351. 10.1080/10826084.2021.1922454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuper PA, Neuman M, Kanteres F, Baliunas D, Joharchi N, Rehm J, 2010. Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/AIDS - a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol 45 (2), 159–166. 10.1093/alcalc/agp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, 1982. Development and Validation of a Lifetime Alcohol Consumption Assessment Procedure. Addiction Research Foundation, Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ, 1982. Reliability of alcohol use indices: the lifetime drinking history and the MAST. J. Stud. Alcohol 43, 1157–1170. 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J, 2008. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 15, 194–200. 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Charney DS The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science 338(6103), 79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1222942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Seedat S, 2014. Depression and resilience in women with HIV and early life stress: does trauma play a mediating role? A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 4, e004200. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Afifi TO, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Sareen J, Seedat S, 2012. Mental health outcomes in HIV and childhood maltreatment: a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 1 (30), 1–28. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troeman ZCE, Spies G, Cherner M, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Theilmann RJ, Spottiswoode B, Stein DJ, Seedat S, 2011. Impact of childhood trauma on functionality and quality of life in HIV-infected women. Health Qual. Life Outcome 9, 84. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, 2004. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: racial and ethnic contrasts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 61, 481–488. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugochukwu C, Bagot KS, Delaloye S, Pi S, Vien L, Garvey T, Bolotaulo NI, Kuman N, IsHak WW, 2013. The importance of quality of life in patients with alcohol abuse and dependence. Harv. Rev. Psychiatr. 21 (1), 1–17. 10.1097/HRP.0b013e31827fd8aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella S-LC, Pai NB A theoretical review of psychological resilience: defining resilience research over the decades. Arch. Med. Health Sci. 7(2), 233–239. doi: 10.4103/amhs.amhs_119_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD, 1992. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30 (6), 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw MG, Fierman E, Pratt L, Hunt M, Yonkers KA, Massion AO, Keller MB, 1993. Quality of life and dissociation in anxiety disorder patients with histories of trauma or PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatr. 150 (10), 1512–1516. 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters ER, Aloe AM, Wojciak AS, 2023. Examining the associations between childhood trauma, resilience, and depression: a multivariate meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 24 (1), 231–244. 10.1177/15248380211029397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S, Jud A, Landolt MA, 2016. Quality of life in maltreated children and adult survivors of child maltreatment: a systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 25, 237–255. 10.1007/s11136-015-1085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J, 2011. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual. Life Outcome 9 (8), 1–18. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo AP, Ressler KJ, Bradley B, 2014. Resilience characteristics mitigate tendency for harmful alcohol and illicit drug use in adults with a history of childhood abuse: a cross-sectional study of 2024 inner-city men and women. J. Psychiatr. Res. 51, 93–99. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, Kim JJ, Calderon S, Charney DS, Mathé AA, 2013. Understanding resilience. Frontiers Behav. Neurosci. 7 (10), 1–15. 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita A, Yoshioka S-I, 2016. Resilience associated with self-disclosure and relapse risks in patients with alcohol use disorders. Yonago Acta Med. 59 (4), 279–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Sarovar V, Sterling SA, Leibowitz A, McCaw B, Hare CB, Silverberg MJ, Satre DD, 2019. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, substance use, and HIV-related outcomes among persons with HIV. AIDS Care 31 (10), 1241–1249. 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.