Abstract

Background

People tend to feel better after exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This study was performed to investigate the impact of UVA exposure on psychological and neuroendocrine parameters.

Methods

Fifty-three volunteers were separated into 42 individuals who had UVA exposure and 11 individuals who had no UVA exposure. The UVA-exposed volunteers had irradiation sessions six times in a three-week period. All volunteers completed two questionnaires at baseline (T1) and at the end of the study (T3). For the determination of serotonin and melatonin serum levels of all volunteers blood samples were collected at baseline (T1), after the first UVA exposure (T2), and at the end of the study after the sixth exposure (T3).

Results

UVA-exposed volunteers felt significantly more balanced, less nervous, more strengthened, and more satisfied with their appearance at T3. By contrast, the controls did not show significant changes of psychological parameters. In comparison to T1 and T3, serum serotonin was significantly higher and the serum melatonin was significantly lower for the volunteers exposed to UVA at T2. Both, for exposed and non-exposed volunteers serotonin and melatonin levels did not significantly differ at T1 and T3.

Conclusions

It remains obscure, whether the exposure to UVA or other components of the treatment were responsible for the psychological benefits observed. The changes of circulating neuroendocrine mediators found after UVA exposure at T2 may be due to an UVA-induced effect via a cutaneous pathway. Nevertheless, the positive psychological effects observed in our study cannot be attributed to circulating serotonin or melatonin.

Background

Despite the well-known risks linked with ultraviolet (UV) overexposure, use of artificial sunlamp for recreational and cosmetic purposes has become popular in recent decades. In addition to the cosmetic effect of tanning, people feel more active, more energetic and healthier after exposure to sunlight or artificial UV radiation [1-6]. In an open study, 840 (83%) sunbed users (n = 1013) reported being relaxed while using a sunbed [7]. The author speculated on a possible effect on the central nervous system. However, the apparent psychological benefits were closely related to the degree of tan that was achieved through the sunbed and it may be that those subjects who obtained the desired tan were naturally satisfied with the outcome [7,8]. In a small number of studies the influence of UV radiation on psychological parameters and/or neuroendocrine mediators (e.g., β-endorphin, enkephalin) has been investigated systematically [6,9-13]. The results of these studies are controversial, however. Other neuroendocrine mediators such as serotonin and melatonin could also play an important role in mediating UV-induced central effects.

About a quarter of healthy subjects report that winter weather or cloudy days influence their mood, and about 40% of depressed patients show seasonality, as depressive periods are limited to either winter or summer months. These patients respond favorable to light therapy [14-16]. It has been shown that blood serotonin increases in healthy subjects and patients with non-seasonal depression after repeated visible light exposure. Therefore, the involvement of serotonergic mechanisms following light therapy has been suggested [16]. Serotonin is a hormone and neurotransmitter. Centrally produced serotonin affects emotional states, appetite, sleep-wake cycles, and other human rhythms. Peripherally, serotonin is predominantly produced by gastrointestinal tract myenteric plexus neurons. It contributes to hemostasis, immunomodulation, and perception of pain and itch [16-21].

Much of the serotonin in the pineal gland is converted into melatonin by serotonin-N-acetyltransferase which is directly under adrenergic control of sympathetic nerves and has a strong circadian rhythm of activity. Serotonin as well as melatonin have serum half-lives less than one hour [22,23]. Once melatonin is synthesized, it is not stored in the gland, but is circulated. Secretion of melatonin depends on a circadian rhythm with low levels during the day, medium levels in the evening and maximum levels at night between 2 and 4 a.m.. Apart from modulation of immunobiological defence reactions and aging, melatonin participates in the regulation of seasonal biological rhythm. The visible light-induced suppression of nocturnal melatonin via the eye-brain mechanism has been documented in a variety of mammalian species, including monkeys and humans. In contrast, serotonin is increased in the retina, pineal gland, and the hypothalamus in the presence of visible light [24,25].

We conducted a two-group randomized controlled study with healthy subjects in order to investigate the impact of UVA exposure on psychological parameters and serotonin and melatonin serum levels.

Material and methods

Subjects and study protocol

The three-week study was performed in a university setting during the winter months from December 2000 to March 2001. Fifty-three healthy volunteers were recruited and gave their informed consent for participation in the study. Detailed data of the volunteers are listed in Table 1. Before the experiments, all volunteers were interviewed and skin types were determined according to Fitzpatrick's classification [26]. Exclusion criteria included: history of regular sunbed use, photosensitivity and psychiatric disorders, drug use and abuse, and UV exposure for two months prior to the study. Based on unbalanced randomization the 53 volunteers were separated into 42 individuals who had UVA exposures and 11 individuals who had no UVA exposure in the course of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the 53 volunteers, distribution of skin types, and results of colorimetry at T1 and T3

| Volunteers (n = 53) | Gender female (f), male (m) | Mean age ± SD years (range) | Skin type | Colorimetry L*-values | ||

| II | III | T1 | T3 | |||

| UVA-exposed (n = 42) | 32 f, 10 m | 25.9 ± 8 (18–57) | 18 | 24 | 62.7 | 60.1a |

| Non-exposed (n = 11) | 7 f,4 m | 26.5 ± 6.2 (18–36) | 3 | 8 | 61.4 | 62.4b |

a P < 0.001; b P > 0.05; differences in gender and age between UVA-exposed and non-exposed volunteers were insignificant (P > 0.05)

At baseline (T1), all volunteers (n = 53) completed the questionnaires and underwent blood collection. Subsequently, the exposed volunteers had UVA irradiation (skin type II: 15 min.; skin type III: 20 min.). After that, blood collection was performed again (T2). Within the following three weeks the exposed volunteers had two UVA irradiation sessions on a weekly basis (exposure six times in total). On the last day of the study (after the sixth UVA exposure) all volunteers completed the questionnaires and underwent blood collection again (T3).

Questionnaires

To assess changes of emotional states and physical awareness of the volunteers at T1 and T3, two well-established validated questionnaires were employed: Basler Befindlichkeits-Skala BBS [27], Fragebogen zum Körperbild FKB-20 [28]. The BBS (16 items) was developed to assess and quantify changes of emotional states [factor analysis includes four factors: 1) vitality 2) intrapsychological homeostasis 3) social extroversion 4) vigilance]. The FKB-20 (20 items) was designed to assess non-clinical disturbances of physical awareness. It measures two independent dimensions: 1) negative physical awareness 2) vital physical dynamics.

UV sources and dosimetry

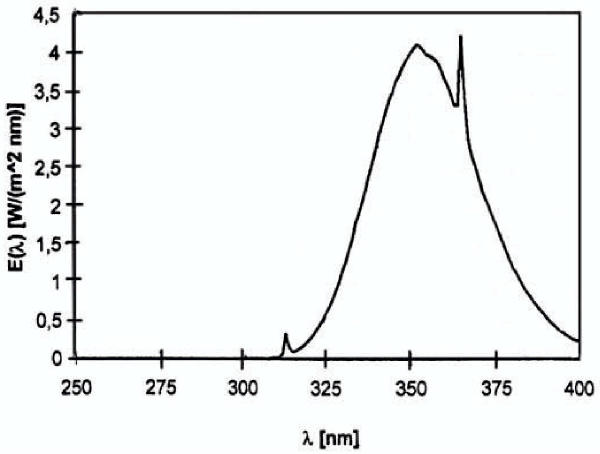

The Ergoline Classic 450 Super Power sunbed (JK-Products GmbH, Windhagen, Germany) was used for whole-body irradiation. This air-conditioned tanning device was fitted with 42 Solarium Plus R1-12-100 W fluorescence lamps (Wolff System AG, Riegel, Germany). Before the beginning of the investigation, the spectral output of the lamps was measured with a calibrated MED 2000 spectroradiometer (Opsira GmbH, Weingarten, Germany). The integrated irradiance assessed spectroradiometrically at skin level was 17.5 mW/cm2 for UVA (means from 16 measure sites). Only a small fraction of UVB was measured (0.09 mW/cm2). Therefore the fluorescence lamp was defined as a UVA source. The emission spectrum of the fluorescence lamp is shown in Figure 1. UVA irradiance was routinely measured each exposure session with the UV-METER radiometer (Waldmann, Willingen-Schwenningen, Germany). Before each UVA dosimetry and exposure session the lamps underwent a warm-up period of 10 min [29]. The UVA dosage of each exposure session was 16 J/cm2 (skin type II) and 21 J/cm2 (skin type III), respectively. The dosage was given in line with the manufacturer's recommendations. The cumulative UVA doses were 96 J/cm2 for skin type II and 126 J/cm2 for skin type III. During sunbed exposure the volunteers wore goggles that were opaque to UV and visible light.

Figure 1.

Spectral irradiance of the fluorescence lamp used in this study.

Skin color measurements

To quantify the degree of tanning a compact tristimulus colorimeter Minolta Chroma Meter CR-200 was employed (Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The measurements were performed in accordance with the definitions of the CIE L* a* b* color space [30]. The luminance (L*) was used to evaluate differences between skin color of all volunteers (n = 53) at T1 and T3. The L* value expresses the relative brightness of the color, ranging from total black to completely white. Skin color was measured on the forehead.

Serotonin and melatonin serum levels

Blood was collected by venipuncture between 8.00 and 11.00 a.m. after an overnight fast. We saw to it that blood collection at T1 and T3 was performed at the same time for the same volunteer. The serum for the serotonin and melatonin determination was obtained from blood stored for 60 min and centrifugated for 6 min at 3000 × g; after that, 6 ml serum were stored at -71°C. Serotonin was analyzed with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to manufacturer's instructions (IBL GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). The assay procedure is based on the competition between biotinylated and non-biotinylated antigen for a fixed number of antibody binding sites. Bound anti-biotin serotonin is complexed with goat anti-biotin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. The cross reactivity of the anti-N-acetylserotonin antiserum against serotonin is less than 0.01%. The lowest detectable level that can be distinguished from zero standard is 0.03 ng/ml. This technique has a mean intra-assay variance coefficient of about 5% and a mean inter-assay variance coefficient of 7.6%. The results were expressed as the concentration of serotonin in ng/ml (normal range: 20–240 ng/ml) [31]. Serum melatonin levels were determined by means of a commercial radioimmunoassy kit RIA (IBL GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) that consisted of 125I-melatonin (4 μCi), including antiserum, precipitating antiserum, serum standards, enzymes, enzyme buffers and assay buffers. The cross reactivity of the antiserum to serotonin is less than 0.01%. The lowest detectable level of melatonin that deviates from the zero standard is < 3.5 ρg/ml. This technique has a mean intra-assay variance coefficient of approximately 8.3% and a mean inter-assay variance coefficient of about 14.9%. The results were expressed as the concentration of melatonin in ρg/ml (normal range: during day-time up to 30 ρg/ml and during night-time up to 150 ρg/ml) [32].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 10.0 for Windows. Analysis of the distribution was made by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov-test; to examine the homogeneity and heterogeneity of variances the Levene's test for equality of variances was used. After that, the following methods have been applied: for comparison of two independent samples by normal distribution: the 2-tailed Student's t-test for independent samples, for comparison of two independent samples by non-normal distribution: the Mann-Whitney U-test (2-tailed), for comparison of paired samples by normal distribution: the t-test for paired samples, for comparison of paired samples by non-normal distribution: the Wilcoxon test. Correlations were calculated through Pearson's correlation coefficient (r). The questionnaires were analysed using validated scales on the basis of factor analysis. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The evalution of the BBS questionnaires (questions nos 1, 5, and 6) revealed that UVA-exposed volunteers felt significantly more balanced (P = 0.01), less nervous (P = 0.03), and more strengthened (P = 0.009) at T3; the increase of robustness and strength was confirmed by the results of the FKB-20 questionnaire (question no. 1). The evalution of question no. 2 of the FKB-20 questionnaire revealed that UVA-exposed volunteers were significantly (P = 0.04) more satisfied with their appearance at T3. Data of the above-mentioned items with significant changes are provided in Table 2 and Table 3 in detail. The results of the other items (detailed data not shown) of the questionnaires completed by the UVA-exposed volunteers showed no significant differences between T1 and T3 (P > 0.05). The results of the questionnaires (detailed data not shown) completed by the controls at T1 and T3 differed insignificantly (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Data of the BBS questionnaire completed by the UVA-exposed volunteers (n = 42)

| Question no. 1 (P = 0.03) | ||

| "I feel..." | Before UVA exposure (T1) Volunteers (%) | After UVA exposure (T3) Volunteers (%) |

| ... very calm. | 7(16.7) | 9(22) |

| ... calm. | 14 (33.3) | 18(43.9) |

| ... rather calm. | 9(21.4) | 10 (24.4) |

| ...equally. | 3(7.1) | 1 (2.4) |

| ... rather nervous. | 6(14.3) | 3 (7.3) |

| ... (very) nervous. | 3(7.1) | 0 |

| Question no. 5 (P = 0.01) | ||

| "I feel ..." | ||

| ... very balanced. | 8(19) | 11(26.8) |

| ... balanced. | 11 (26.2) | 16 (39) |

| ...rather balanced. | 9(21.4) | 7(17.1) |

| ... equally. | 7(16.7) | 5 (12.2) |

| ... rather unbalanced. | 5(11.9) | 2 (4.9) |

| ... (very) unbalanced. | 2 (4.8) | 0 |

| Question no. 6 (P = 0.009) | ||

| "I feel..." | ||

| ... very strengthened. | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.9) |

| ... strengthened. | 5 (12.2) | 11(26.8) |

| ... rather strengthened. | 7(17.1) | 8(19.5) |

| ...equally. | 12 (29.3) | 14(34.1) |

| ... rather weakened. | 9(22) | 5 (12.2) |

| ...(very) weakened. | 6(14.7) | 2 (2.4) |

Table 3.

Data of the FKB-20 questionnaire completed by the UVA-exposed volunteers (n = 42)

| Question no. 1 (P = 0.01) | ||

| "In all I feel robust and strong" | Before UVA exposure (T1) Volunteers (%) | After UVA exposure (T3) Volunteers (%) |

| Not correct or hardly correct | 2(5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Correct in part | 8(20) | 4(10) |

| Correct to a great extent | 26 (65) | 29 (72.5) |

| Absolutely correct | 4(10) | 6(15) |

| Question no. 2 (P = 0.04) | ||

| "There is something wrong with my appearance" | ||

| Not correct or hardly correct | 14(34.1) | 18(45) |

| Correct in part | 21 (51.2) | 19 (47.5) |

| Correct to a great extent | 6(14.6) | 3 (7.5) |

| Absolutely correct | 0 | 0 |

The serotonin (normally distributed) and melatonin (non-normally distributed) serum levels are detailed in Table 4. In comparison to T1 and T3, serotonin levels of the UVA-exposed volunteers were significantly higher at T2 (r = 0.95; P = 0.003 and r = 0.88; P = 0.02, respectively). The serotonin levels of non-exposed controls differed insignificantly at T1, T2, and T3. In comparison to T1 and T3, the melatonin levels were significantly lower for the UVA-exposed volunteers at T2 (r = 0.96; P < 0.001 and r = 0.67; P = 0.03). For the non-exposed controls, a significantly lower melatonin level was found at T2 versus T1 (r = 0.94; P = 0.005) but not versus T3. Colorimetric measurements of UVA-exposed volunteers at T3 revealed a significant decrease of luminance (P < 0.001), by contrast the controls showed no significant change of skin color (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Serotonin and melatonin serum levels* of the UVA-exposed volunteers and non-exposed controls

| Serum level | T1 | T2 | T3 |

| Serotonin (ng/ml) | |||

| UVA-exposed (n = 42) | 215 ± 75.2 | 228.7 ± 84.2 a | 213.2 ± 69.1 d |

| Non-exposed (n = 11) | (191.9 ± 53.7) | (198.9 ± 52.4) | (212.5 ± 78.5) |

| Melatonin (ρg/ml) | |||

| UVA-exposed (n = 42) | 17.3 ± 15.1 | 12.5 ± 8b | 17.9 ± 20.2 e |

| Non-exposed (n = 11) | (25.7 ± 19.7) | (20.6 ± 15.3) c | (28.6 ± 41.1) |

* Data comprise mean ± SD; a P < 0.001 vs T1; b P = 0.01 vs T1; c P = 0.005 vs T1; d P = 0.02 vs T2; e P 0.03 vs T2

Discussion

The influence of electromagnetic radiation on serotonin and melatonin serum levels has been predominantly studied using visible wavelengths that effected via the eye-brain pathway [4,25,33]. A previous report suggested that skin light exposure – for example of the popliteal region – can affect human circadian rhythms and suppress peripheral melatonin levels in humans via "humoral phototransduction" [34]. However, subsequent studies have not supported the existence of extraocular photic regulation of the circadian rhythms in humans [35-37]. To avoid a possible influence of neuroendocrine effects via eye-brain mechanism, our volunteers were instructed to use opaque glasses during irradiation. In comparison to the high spectral irradiance in the UVA region, the output within the UVB and visible region was considered negligible. Thus, we could investigate UVA-induced effects that were mediated via a cutaneous pathway.

We found a modest increase of serotonin and a decrease of melatonin levels in the UVA-exposed volunteers at T2. Both changes were statistically significant (P < 0.001; P < 0.01). At all times, differences of serotonin levels of the non-exposed controls did not reach significant levels. The conversion of serotonin to melatonin is a photosensitive step resulting from the photoinhibition of the enzymes N-acetyltransferase. It has recently been reported that UVA radiation is a powerful signal affecting the pineal melatonin-generating system and inhibits N-acetyltransferase [33,38,39]. Accordingly, it has been observed that melanocytes are photoresponsive cells which express and metabolize indolamines, such as melatonin, during the G2 phase while responding to UV exposure [40]. Therefore, we make the hypothesis that UVA radiation leads to an inhibition of N-acetyltransferase via a cutaneous pathway [41]. As a result the production of serotonin increases at the expense of melatonin.

Although we observed positive changes in emotional states and physical awareness for the UVA-exposed volunteers, the serum parameters did not correlate with these changes. Therefore, the mood-modifying effects have probably not been mediated directly by circulating serotonin or melatonin. In contrast to Diffey's report [7] the psychological benefits observed in our study did correlate only with slight tan as confirmed by the data of the colorimetric measurements. However, the UVA-exposed volunteers were more satisfied with their appearance at T3 and therefore possibly felt better (Tab. 3). We cannot rule out that these psychological benefits were due to the slight tan that UVA-exposed volunteers experienced. During the last decades tanning preferences have changed and many people consider a slight tan more attractive and healthier than a deep tan. Of course this trial would have benefited from a double-blind placebo-controlled study design, as described by Polderman et al. [42]. Such a protocol, however, would be very difficult to attain as the increasing tan of UVA-exposed subjects would "break the blind" after a few exposures. Since we intended to investigate the effect of standard UVA dosage commonly used in tanning salons, we did the study without a double-blind design. If the amount of tan would "break the blind" then perhaps a sunless tanning lotion could be used on UV-exposed as well as non-exposed individuals. Nevertheless, interactions between the tanning lotion and UV radiation cannot be ruled out.

It would be interesting to investigate in future studies the influence of psychosocial effects on emotional states and physical awareness claimed to occur after UV exposure. Like, for example, the cognitive theory of the psychological effect of the "self-fulfilling-prophecy", in this study "self-fulfilling-prophecy" could reflect the prevailing opinion in Western societies that sunlight and sunbed exposure generally improve the mood and emotional states.

Conclusions

Although we observed psychological benefits after a series of sunbed exposure sessions it has not been possible to differentiate whether the UVA exposure or other components of the treatment; such as the volunteer's knowledge that he or she was exposed to UVA radiation, and/or the resultant tan, were responsible for these benefits. The slight increase in serotonin levels and the decrease in melatonin levels of exposed volunteers (T2) may be due to UVA-induced effects via a cutaneous pathway. Nevertheless, the positive psychological effects observed in our study cannot be attributed to circulating serotonin or melatonin. Thus, sophisticated double-blind placebo-controlled trials are necessary to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms of mood-modifying effects claimed to be linked with UV exposure and neuroendocrine mediators.

Abbreviations

UV: ultraviolet

Competing interests

This work was supported in part by grants from the Förderverein Sonnenlicht-Systeme e. V. (FVS, Stuttgart, Germany).

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We are very grateful to Ms Kornelia Richter (Gemeinschaftspraxis für Laboratoriumsmedizin, Dortmund, Germany) for her helpful technical support in the course of the study. We thank the Förderverein Sonnenlicht-Systeme e.V. (FVS, Stuttgart, Germany) who also provided the sunbed for research.

Contributor Information

Thilo Gambichler, Email: t.gambichler@derma.de.

Armin Bader, Email: a.bader@derma.de.

Mirjana Vojvodic, Email: m.vojvodic@derma.de.

Falk G Bechara, Email: f.bechara@derma.de.

Kirsten Sauermann, Email: k.saueremann@derma.de.

Peter Altmeyer, Email: p.altmeyer@derma.de.

Klaus Hoffmann, Email: k.hoffmann@derma.de.

References

- Altmeyer P, Hoffmann K, Stücker M, eds Skin Cancer and UV Radiation. Springer Berlin New York. 1997.

- Wang S, Setlow R, Berwick M, et al. Ultraviolet A and melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:837–846. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Marcusson JA, Hemminki K. DNA photodamage induced by UV phototherapy lamps and sunlamps in human skin in situ and its potential importance for skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:194–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF, Jung EG, eds Biological effects of light. Proceedings of a symposium, Basel, Switzerland, November 1–3, 1998. Kluwer Academic Publishers Norwell. 1999.

- Boldeman C, Beitner H, Jansson B, Nilsson B, Ullen H. Sunbed use in relation to phenotype, erythema, sunscreen use and skin diseases. A questionnaire survey among Swedish adolescents. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:712–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiter F, Bilek P, Bachl N, et al. The effect of artificial and natural sunlight upon some psychosomatic parameters of the human organism. In: Hèléne C, Charlier M, Montenay-Garestier T, Laustriat G, editor. Trends in Photobiology. Plenum Press New York; 1982. pp. 465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Diffey BL. Use of UVA sunbeds for cosmetic tanning. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb06221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JM, Amonette RA. Indoor tanning: risks, benefits, and future trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:288–298. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belon PE. UVA exposure and pituitary secretion. Variations of human lipotropin concentrations (βLPH) after UVA exposure. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;42:327–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1985.tb08948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levins PC, Carr DB, Fisher JE, Momtaz K, Parrish JA. Plasma beta-endorphin and beta-lipotropin response to ultraviolet radiation. Lancet. 1983;16:166. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen JB, Avrach WW, Hansen ES, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Kragballe K. Increased levels of enkephalin following natural sunlight (combined with salt water bathing at the Dead Sea) and ultraviolet A radiation. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1012–1019. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintzen M, Ostijn DMJD, le Cessie S, Burbach JPH, Vermeer BJ. Total body exposure to ultraviolet radiation does not influence plasma levels of immunoreactive beta-endorphin in man. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2001;17:256–260. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2001.170602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCF, Shuster S, Marks JM, Penny RJ, Thordy AJ. The effects of photochemotherapy on endocrine secretion in patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;61:350–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerevanian BI, Anderson JL, Grota LJ, Bray M. Effects of bright incandescent light on seasonal and nonseasonal major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18:355–364. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart KT, Gaddy JR, Byrne B, Miller S, Brainard GC. Effects of green or white light for treatment of seasonal depression. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90016-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao ML, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, Mackert A, Strebel B, Stieglitz RD, Volz HP. Blood serotonin, serum melatonin and light therapy in healthy subjects and in patients with nonseasonal depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;86:127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover V, Jarman J, Sandler M. Migraine and depression: biological aspects. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirson AR, Heuchert JW. Correlations for serotonin levels and measures of mood in a nonclinical sample. Psychol Rep. 2000;87:707–716. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A, Wortsman J. Neuroendocrinology of the skin. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457–487. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JC, Cross RJ, Walker RF, Markesbery WR, Brooks WH, Roszman TL. Influence of serotonin on the immune responses. Immunology. 1985;54:505–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan RL, Lipper G, Lerner EA. The neuro-immuno-cutaneous-endocrine network: relationship of mind in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1431–1435. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.11.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall TC. 5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically-effective serotonin precursor. Altern Med Rev. 1998;3:271–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann H, Dittgen M, Hoffmann A, Bartsch C, Breitbarth H, Timpe C, Farker K, Schmidt U, Mellinger U, Zimmermann H, Graser T, Oettel M. Evaluation of an oral pulsatile delivery system for melatonin in humans. Pharmazie. 1998;53:462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ. Pineal melatonin: cell biology of its synthesis and its physiological interactions. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:151–180. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE. Visible light induced changes in the immune response through an eye-brain mechanism (psychoneuroimmunology). J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 1995;29:3–15. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(95)90241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I and IV. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:869–887. doi: 10.1001/archderm.124.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobi V. Basler Befindlichkeits-Skala. Ein Self-Rating zur Verlaufsmessung der Befindlichkeit. Beltz Weinheim. 1985.

- Clement U, Löwe B. Fragebogen zum Körperbild (FKB-20). Mappe mit Handanweisung, Fragebogen, Auswertungen. Hogrefe Göttingen. 1996.

- Gasparro FP, Brown DB. Photobiology 102: UV sources and dosimetry – the proper use and measurement of "photons as a reagent". J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:613–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton A, Fischer T, Lathi A, Wilhelm KP, Taikiwaki H, Serup J. Guidelines for measurement of skin colour and erythema. A report from the standardization group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBL GmbH (Hamburg Germany) Instruction for use. Serotonin ELISA. Cat-No: RE 59121. 1998.

- IBL GmbH (Hamburg Germany) Instruction for use. Melatonin direct RIA. Cat-No: RE 29301/71, 1998.

- Brainard GC, Podolin PL, Leivy SW, Rollag MD, Cole C, Barker FM. Near-ultraviolet radiation suppresses pineal melatonin content. Endocrinology. 1986;119:2201–2205. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-5-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SS, Murphy PJ. Extraocular circadian phototransduction in humans. Science. 1998;279:396–399. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom N, Heiskala H, Hatonen T, Mustanoja S, Alfthan H, Alila-Johansson A, Laakso ML. No evidence for extraocular light induced phase shifting of human melatonin, cortisol and thyrotropin rhythms. Neuroreport. 2000;11:713–717. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200003200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom N, Hatonen T, Laakso M, Alila-Johansson A, Laipio M, Turpeinen U. Bright light exposure of a large skin area does not affect melatonin or bilirubin levels in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1098–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koorengevel KM, Gordijn MC, Beersma DG, Meesters Y, den Boer JA, van den Hoofdakker RH, Daan S. Extraocular light therapy in winter depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:691–698. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawilska JB, Rosiak J, Nowak JZ. Effects of near-ultraviolet (UV-A) light on melatonin biosynthesis in vertebrate pineal gland. Biol Signals Recept. 1999;8:64–69. doi: 10.1159/000014570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraikin GY, Strakhovskaya MG, Ivanova EV, Rubin AB. Near-UV activation of enzymatic conversion of 5-hydroxytryptophan to serotonin. Photochem Photobiol. 1989;49:475–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1989.tb09197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar B. Melatonin and melanocyte functions. Biol Signals Recept. 2000;9:260–266. doi: 10.1159/000014648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misery L. The neuro-immuno-cutaneous system and ultraviolet radiation. Photodermatol Photoimunol Photomed. 2000;16:78–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2000.d01-8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman MCA, Huizinga TWJ, Le Cessie S, Pavel S. UVA-1 cold light treatment of SLE: a double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;112:112–115. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]