Abstract

Background

Hip fracture is a common and serious traumatic injury for older adults characterised by poor outcomes.

Objective

This systematic review aimed to synthesise qualitative evidence about the psychosocial impact of hip fracture on the people who sustain these injuries.

Methods

Five databases were searched for qualitative studies reporting on the psychosocial impact of hip fracture, supplemented by reference list checking and citation tracking. Data were synthesised inductively and confidence in findings reported using the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research approach, taking account of methodological quality, coherence, relevance and adequacy.

Results

Fifty-seven studies were included. Data were collected during the peri-operative period to >12 months post fracture from 919 participants with hip fracture (median age > 70 years in all but 3 studies), 130 carers and 297 clinicians. Hip fracture is a life altering event characterised by a sense of loss, prolonged negative emotions and fear of the future, exacerbated by negative attitudes of family, friends and clinicians. For some people after hip fracture there is, with time, acceptance of a new reality of not being able to do all the things they used to do. There was moderate to high confidence in these findings.

Conclusions

Hip fracture is a life altering event. Many people experience profound and prolonged psychosocial distress following a hip fracture, within a context of negative societal attitudes. Assessment and management of psychosocial distress during rehabilitation may improve outcomes for people after hip fracture.

Keywords: hip fracture, trauma, systematic review, qualitative analysis, psychosocial, older people

Key Points

There is a large body of evidence reporting coherent and relevant evidence on the psychosocial impact of hip fracture.

Hip fracture is a life altering event characterised by a sense of loss, negative emotions and fear of the future. These reactions can be exacerbated by negative attitudes by carers and clinicians.

Psychosocial management may be a component of optimal care to improve outcomes after hip fracture.

Background

Hip fracture is a common and serious injury for older adults. Approximately 1 in 4 people die within the first 12 months after hip fracture [1, 2], only 2 in 3 people who previously lived independently in the community return home, [3] and only about 1 in 3 regain pre-fracture mobility within 6 months after hip fracture [4]. Although these statistics are compelling, they do not consider the additional psychosocial impact that a significant injury, such as hip fracture, can have on a person. Psychosocial factors after injury comprise cognitive, affective and behavioural factors [5]. These factors, including stress perceptions, anxiety and social connections, have been shown to affect return to community engagement in other populations [5], and it is possible these factors are even more pronounced in people after hip fracture when coupled with the increased rates of social isolation and loneliness common among older people [6].

Major trauma, defined as a serious injury with potentially life-changing consequences, is associated with high levels of psychosocial impact, including psychological distress and post-traumatic stress symptoms [7]. Given the associated morbidity and mortality, hip fracture can be a major trauma for which high levels of psychosocial impact may be expected. Understanding the psychosocial impact of hip fracture could inform assessments and interventions to improve outcomes. For example, there is potential to address loss of confidence in mobility after hip fracture through interventions such as motivational interviewing, with subsequent improvements in functional mobility [8]. However, recommended rehabilitation interventions [9] and hip fracture guidelines pay little attention to the assessment or management of the significant psychosocial impact of these injuries [10, 11].

A recent systematic review reported quantitative measures of psychological outcomes after hip fracture in 55 studies [12]. The main psychological factors identified were depression and anxiety with evidence of a negative association between these factors and functional outcome. In another quantitative review of 19 studies, social factors, including social support and living arrangements, were found to be associated with functional recovery and mortality [13]. These findings demonstrate how psychosocial factors can influence outcomes after hip fracture, but the findings are limited to the measurement tools chosen by researchers.

Another source of insights into the psychosocial impacts of hip fracture is the lived experience of people, obtained through qualitative research. Qualitative methods can provide in-depth details about phenomena that are difficult to convey with quantitative methods [14]. In this way, the evaluation of the impact of hip fracture is not limited to outcomes chosen by researchers but gives voice to people who have experienced a hip fracture and those who care for them. One review of 14 qualitative studies explored perspectives of recovery after hip fracture in relation to the end point of care [15] but there has been no synthesis of qualitative literature investigating the psychosocial impact of hip fracture. Therefore, we aimed to systematically review qualitative studies to describe the psychosocial impact of hip fracture on the people who sustain them.

Methods

This study is reported consistent with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) [16] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17] (Appendices 1 and 2). A protocol was registered prospectively on the PROSPERO platform (CRD42023457564).

Search strategy and selection criteria

We included studies reporting experiences of people with hip fracture, as well as those involving carers and clinicians involved in the treatment of these patients (Table 1). We were interested in primary qualitative studies that explored psychosocial experiences after hip fracture.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Context |

|

|

| Study design |

|

|

| Outcomes/ Experiences |

|

|

| Other |

|

Five databases were searched to identify relevant studies (MEDLINE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL) from inception until 25 August 2023. Further studies were identified through checking the reference lists of included studies and citation tracking using Google Scholar.

A pre-planned search strategy was developed to identify all available studies, using the search terms ‘hip fracture’, ‘qualitative’ and synonyms for these terms. The search was limited to studies published in English. Search strategies can be viewed in Appendix 3.

Articles were imported into Covidence software with duplicates removed. Two of a team of three reviewers (MR, SW and NT) independently screened the title and abstract of each article against inclusion criteria. The full text of any articles that remained after title and abstract screening were also screened by two of three reviewers (MR, SW and NT) independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers, and if disagreement persisted, a third reviewer decided if the article was included or not.

Two reviewers independently extracted data on study characteristics and design from each study (MR and SW) and the accuracy of extraction was checked by a third reviewer (AS or DS). These data included sample size, setting, data collection method (e.g. interview or focus group), qualitative framework, and research questions informing the analysis; these data were collated using Microsoft Excel software. Prior to data extraction, the form was pilot tested on five studies.

The quality of included studies was assessed by two reviewers (MR and SW) using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research [18]. This checklist contains 10 questions on three aspects: what the results are; whether the results are valid; and whether the results are helpful locally. Quality appraisal was conducted by two reviewers independently, and any conflict was resolved through consensus.

Synthesis

A qualitative meta-synthesis approach was used to analyse the data using methods described by Lachal et al [19]. First, two reviewers from a team of four (MR, CP, NS, NT) read and re-read the results sections of each included study to familiarise themselves with the data. Next, data from the results sections and relevant sections of the discussion were extracted from each study and codes were assigned using an inductive process. The identified codes were reviewed and grouped according to similarity in meaning. Lastly, the four reviewers (MR, CP, MS, NT) met and organised the grouped codes into themes and subthemes. Final synthesis involved four reviewers looking for potential relationships across the themes and subthemes. Microsoft Word and NVivo software were used to help with data management and analysis.

The Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) approach was applied to determine confidence in the identified themes considering methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy of data and relevance, with findings summarised in a qualitative evidence table [20]. Methodological limitations were categorised based on the number of unclear or unreported items on the CASP checklist. For individual studies, ‘no or very minor concerns’ category was awarded for 0 or 1 missing items on the CASP checklist; ‘minor concerns’ for 2 missing items; ‘moderate concerns’ for 3 or 4 missing items; and ‘serious concerns’ for more than 4 missing items. The degree of confidence was determined based on the number of serious/moderate/minor methodological limitations compared to the overall number of studies supporting each finding. Coherence refers to how cogent the fit is between the data from primary studies and a review finding that synthesises that data [20]. As such, coherence was categorised based on the degree to which the data from the included studies was transformed to create synthesised findings in our review. For example, synthesised findings that directly described results reported in the source papers were categorised as ‘no or very minor concerns’, while synthesised findings that were considered to be interpretive or explanatory were categorised as ‘minor concerns’ or more [20]. Adequacy was categorised based on the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding. Relevance was categorised based on whether the data from the primary studies was applicable to the context (population, phenomenon of interest, setting) of the review. Confidence in each review finding was reported as either high, moderate, low or very low. Findings were downgraded from high to moderate if there were at least moderate concerns in one domain and could be downgraded two levels if there were moderate concerns in two domains or serious concerns in one domain.

Results

Study selection

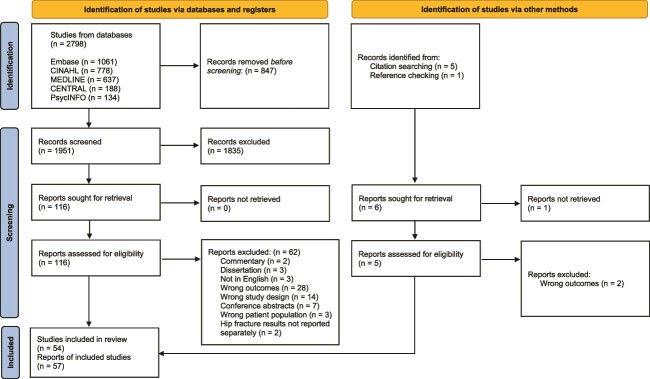

The search strategy yielded 2798 studies, with 1951 records remaining after removal of duplicates (Figure 1). Following application of the inclusion criteria, the full text of 116 studies were screened and 54 studies were included in the review. Citation searching and reference checking yielded a further 3 studies, bringing the total number of included studies to 57 [21–77]. The most common reason for exclusion was that a study did not include data on psychosocial experiences (n = 30, 56%) (Appendix 4).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow of study selection [17].

Methodological quality of included studies

All studies had a clear rationale for selecting qualitative methodology to address their research question and all but two studies [27, 55] had a clear statement of the study aims (Appendix 5). Only 18 (32%) studies had adequately considered the relationship between the researchers and the participants. While most studies had considered ethical issues, eight (14%) studies did not explicitly or adequately report on ethical review. Six studies (11%) had insufficiently rigorous data analysis, and 20 (35%) studies did not have a clear statement of findings.

Study participant characteristics

The participants in the included studies were 919 adults after hip fracture from 54 studies, 297 clinicians from 11 studies and 130 carers from 12 studies. Most participants with hip fracture were female (73%, 631 of 860 where reported) and median or mean ages, where reported, were at least 70 years for all but three studies [42, 55, 66]. Median or mean age was at least 80 years in 19 studies (Table 2). Participants were receiving acute care in hospital in 18 studies, completing sub-acute rehabilitation in 11 studies, and living in the community in 32 studies, with 16 studies exploring perspectives across the different periods. All except five studies used semi-structured interviews as the data collection method.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Title | Setting | Sample size (n) | Data collection method | Qualitative framework | Median patient age (range) | Female patients (n, %) | Community-dwelling (n, %) | Living alone (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrahamsen [21] | Patients’ perspectives on everyday life after hip fracture: A longitudinal interview study | Acute- Post-hip fracture |

12 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face/telephone | Abductive reasoning | 83 (65–103) 89 (82–97) 89 (82–97) |

10 (83) 6 (100) 4 (100) |

11 (92) 5 (83) 3 (75) |

7 (58) |

| Ansah [22] | Systems modelling as an approach for eliciting the mechanisms for hip fracture recovery among older adults in a participatory stakeholder engagement setting | NR | 20 (11 Clinicians, 8 PwHF, 1 Carer) | Participatory workshop, Group, Face-to-face | Group Model Building | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Archibald [23] | Patients’ experiences of hip fracture | Subacute-Community | 5 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological methodology | (>65)a | 4 (80) | NA | NR |

| Asplin [24] | See me, teach me, guide me, but it’s up to me! Patients’ experiences of recovery during the acute phase after hip fracture | Acute-Subacute | 19 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | 81 (66–94) | 13 (68) | NA | 14 (74) |

| Ballinger [25] | Falling from grace or into expert hands? Alternative accounts about falling in older people | Acute-Subacute | 28 (8 PwHF, 20 Clinicians) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Discourse analysis | m = 81 (70–89) | 7 (88) | NA | NR |

| Bergh [26] | Ways of talking about experiences of pain among older patients following orthopaedic surgery | Acute | 22 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Descriptive qualitative content analysis | m = 81 (65+)a | NR | NA | 22 (37) |

| Bishop [27] | From boundary object to boundary subject; the role of the patient in coordination across complex systems of care during hospital discharge | Acute-Community | 86 (17 PwHF, 69 Clinicians) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Ethnographic approach, interpretative qualitative data analysis | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Borkan [28] | Expectations and outcomes after hip fracture among the elderly | Acute-Community | 80 PwHF | Interviews, Individual, Face-to-face/telephone | Ethnographic approach, Content analysis | m = 80 (65+)a | 65 (81) NR |

NA NR |

NR |

| Borkan [29] | Finding meaning after the fall: injury narratives from elderly hip fracture patients | Acute- Community |

80 PwHF | Questionnaire; Semi-structured interviews | Explanatory model |

m = 80 (>65)a NR |

65 (81) NR |

NA NR |

NR |

| Bruun-Olsen [30] | ‘I struggle to count my blessings’: Recovery after hip fracture from patients’ perspective | Community | 8 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological methodology | (69–91) | 6 (75) | 8 (100) | NR |

| Furstenberg [31] | Expectations about outcome following hip fracture among older people | Acute-Subacute | 20 (11 PwHF, 9 Non-patients (community-dwelling elderly)) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | (59–85) | 7 (63) | NA | NR |

| Gesar [32] | Hip fracture: an interruption that has consequences four month later. A qualitative study | Community | 25 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Inductive content analysis | (65+)a | 22 (88) | 22 (88) | NR |

| Gesar [33] | Older patients’ perception of their own capacity to regain pre-fracture function after hip fracture surgery—an explorative qualitative study | Acute | 30 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Inductive content analysis | m = 83 (65–97) | 27 (90) | NA | NR |

| Gorman [34] | Exploring older adults’ patterns and perceptions of exercise after hip fracture | Community | 32 PwHF | Interviews (open-ended), Individual, Telephone | Unspecified thematic analysis | m = 83 (62–97) | 22 (69) | 29 (100) | NR |

| Griffiths [35] | Evaluating recovery following hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of what is important to patients | Subacute-Community | 53 (31 PwHF, 22 Carers) | Interview, Individual/dyad, Face-to-face | Inductive, thematic analysis and cross case analysis | m = 82 (SD = 9) | 20 (65) | NR | NR |

| Guilcher [36] | A qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of deconditioning in hospital in Ontario, Canada | Acute-Community | 53 (15 PwHF, 10 Carers, 17 Clinicians, 11 Managers) | Interview, Individual, Face-to face/telephone | Constant comparison | (50+)a | NR | NR | NR |

| Gunnarsson [37] | Hip-fracture patients’ experience of involvement in their care: A qualitative study | Subacute | 16 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Systematic text condensation | m = 78 (65–72) | 13 (81) | NA | NR |

| Haslam-Larmer [38] | Early mobility after fragility hip fracture: A mixed methods embedded case study | Acute | 28 (17 PwHF, 10 Clinicians, 5 Carers) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual/dyad, Face-to-face | Thematic analysis | 86 (66–100) | 14 (78) | NA | NA |

| Hommel [39] | The patient’s view of nursing care after hip fracture | Acute | 10 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | m = 78 | 9 (90) | NA | NA |

| Huang [40] | Ageism perceived by the elderly in Taiwan following hip fracture | Community-Post-hip fracture | 11 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Directed content analysis | m = 75 (64–84) | 6 (55) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Ivarsson [41] | The experiences of pre- and in-hospital care in patients with hip fractures: A study based on Critical incidents | Acute | 14 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Critical incident technique | m = 74 (18+)a | 8 (57) | NA | 8 (57) |

| Janes [42] | Fragility hip fracture in the under 60s: A qualitative study of recovery experiences and the implications for nursing | Post-hip fracture | 30 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face/telephone | The Silences Framework | (29–60)a | 20 (67) | NR | 11 (37) |

| Jellesmark [43] | Fear of falling and changed functional ability following hip fracture among community-dwelling elderly people: An explanatory sequential mixed method study | Community | 4 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Systematic text condensation |

81 (65–92) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) |

| Jensen [44] | Empowerment of whom? The gap between what the system provides and patient needs in hip fracture management: A healthcare professionals’ lifeworld perspective | NA | 16 Clinicians | 3 Focus Groups, Face-to-face | Content analysis | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jensen [45] | ‘If only had I known’: A qualitative study investigating a treatment of patients with a hip fracture with short time stay in hospital | Community | 29 (10 PwHF, 15 Clinicians, 4 Carers) | Field observation Semi-structured interviews, Individual Face-to-face |

Phenomenological Reflective Lifeworld Research | 80 (67–92) | 8 (80) | 10 (100) | 4 (40) |

| Karlsson [46] | Older adults’ perspectives on rehabilitation and recovery one year after a hip fracture—A qualitative study | Post-hip fracture | 20 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | 81 (70–91) | 16 (80) | 20 (100) | 12 (60) |

| Killington [47] | The chaotic journey: Recovering from hip fracture in a nursing home | Subacute | NR (Clinicians, 25 Carers) | 28 Focus Groups, Face-to-face 25 Semi-structured interviews, Individual/dyad, Face-to-face |

Thematic analysis | 88 (70–97) | 24 (86) | NA | 0 (0) |

| Ko [48] | Discharge transition experienced by older Korean women after hip fracture surgery: a qualitative study | Acute-Community | 12 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | 78 (65–87) | 12 (100) | NA 2 (22) |

NR |

| Langford [49] | ‘life goes on.’ Everyday tasks, coping self-efficacy, and independence: Exploring older adults’ recovery from hip fracture | Community | 27 (23 PwHF, 4 Clinicians) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Telephone | Interpretive description | m = 82 (SD = 9) | 12 (52) | NR | 9 (39) |

| Li [50] | Coping processes of Taiwanese families during the post-discharge period for an elderly family member with hip fracture | Community | 20 (8 PwHF, 12 Carers) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | m = 70 (SD = 3.1) | 4 (50) | NR | 0 (0) |

| McMillan [51] | Balancing risk’ after fall-induced hip fracture: The older person’s need for information | Community | 19 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | 80 (67–89) | 15 (79) | 19 (100) | 10 (53) |

| McMillan [52] | A grounded theory of taking control after fall-induced hip fracture | Community | 19 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | 80 (67–87) | 15 (79) | 19 (100) | 10 (53) |

| Moraes [77] | Sedentary behaviour: barriers and facilitators among older adults after hip fracture surgery. A qualitative study | Community-Post-hip fracture | 11 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenology | (60+)^ | 8 (73) | NR | 4 (36) |

| Patel [53] | A qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of patients living with mild, moderate and severe frailty, following hip fracture surgery and hospitalisation | Community | 16 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

77 (65–88) | 11 (69) | 16 (100) | 6 (38) |

| Pol [54] | Everyday life after a hip fracture: what community-living older adults perceive as most beneficial for their recovery | Community | 19 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | 84 (65–94) | 12 (63) | 16 (84) | 16 (84) |

| Pownall [55] | Using a patient narrative to influence orthopaedic nursing care in fractured hips | Acute | 1 PwHF | Semi-structured interview, Individual, Face-to-face | Patient narrative | 60 (60) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) |

| Rasmussen [56] | Enduring life in between a sense of renewal and loss of courage: lifeworld perspectives one year after hip fracture | Post-hip fracture | 9 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological hermeneutic methodology | 80 (71–93) | 7 (78) | 9 (100) | 7 (78) |

| Rasmussen [57] | Being active 1.5 years after hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of aged adults’ experiences of meaningfulness | Post-hip fracture | 9 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological hermeneutic methodology | (72–94) | 7 (78) | 8 (89) | NR |

| Rasmussen [58] | Being active after hip fracture; older people’s lived experiences of facilitators and barriers | Subacute-Community | 13 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological hermeneutic methodology | 80 (70–92) | 11 (85) 9 (82) |

9 (69) 10 (90) |

9 (69) 8 (73) |

| Roberts [59] | Development of an evidence-based complex intervention for community rehabilitation of patients with hip fracture using realist review, survey and focus groups | Acute-Community | 30 (13 PwHF, 13 Clinicians, 4 Carers) | 3 Focus Groups for clinicians 4 Focus Groups for patients and carers |

Thematic analysis | (65+)a | NR | NR | NR |

| Robinson [60] | Transitions in the lives of elderly women who have sustained hip fractures | Community | 15 PwHF | 3 Focus Groups, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | m = 77 (72–82) | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 15 (100) |

| Sandberg [61] | Experiences of patients with hip fractures after discharge from hospital | Community | 14 PwHF | Semi-structured interview, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | 75 (65–85) | 8 (57) | 14 (100) | 8 (57) |

| Schiller [62] | Words of wisdom—patient perspectives to guide recovery for older adults after hip fracture: a qualitative study | Community-Post-hip fracture | 19 (11 PwHF, 8 Carers) | Semi-structured interview, Individual, Face-to-face/telephone | Inductive topic coding | (60–90)a | 10 (91) | NR | NR |

| Segevall [63] | The journey toward taking the day for granted again: The experiences of rural older people’s recovery from hip fracture surgery | Community | 13 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Content analysis | 74 (66–98) | 7 (54) | 13 (100) | 8 (62) |

| Sims-Gould [64] | Patient perspectives on engagement in recovery after hip fracture: A qualitative study | Community | 50 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Telephone | Unspecified thematic analysis | (65–85+)a | 32 (64) | 50 (100) | 21 (42) |

| Southwell [65] | Older adults’ perceptions of early rehabilitation and recovery after hip fracture surgery: A UK qualitative study | Acute | 15 PwHF | Semi-structured interview, Individual, Face-to-face | Thematic analysis, interpretation informed by Bury’s biographical disruption theoretical framework | (65–85+)a | 7 (47) | NA | NR |

| Strom Ronnquist, [66] | “Lingering challenges in everyday life for adults under age 60 with hip fractures – A qualitative study of the lived experience during the first three years” |

Community-Post-hip fracture | 19 PwHF | Semi-structured interview, Individual, Face-to-face/telephone | Phenomenological hermeneutics | 56 (32–59) | 13 (68) | 19 (100) | 5 (26) |

| Taylor [67] | Community ambulation before and after hip fracture: A qualitative analysis | Subacute-Community | 24 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological theoretical framework and Grounded Theory | 76 (67–86) 82 (63–89) |

8 (67) 9 (75) |

NA 12 (100) |

NA 1 (8) |

| Taylor [68] | Discharge planning for patients receiving rehabilitation after hip fracture: A qualitative analysis of physiotherapists’ perceptions | Subacute- Community | 12 Clinicians | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Turner [69] | Development of a questionnaire to assess patient priorities in hip fracture care | Community | 18 (13 PwHF, 5 Carers) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Telephone; Survey | Unspecified thematic | m = 78 | 9 (69) | NR | NR |

| Tutton [70] | Patient and informal carer experience of hip fracture: A qualitative study using interviews and observation in acute orthopaedic trauma | Acute | 50 (25 PwHF, 25 Carers) | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face Ward observation |

Phenomenological approach | 83 (63–91) | 15 (60) | NA | NR |

| Vestol [71] | The journey of recovery after hip-facture surgery: Older people’s experiences of recovery through rehabilitation services involving physical activity | Community | 21 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenological-hermeneutic approach, Systematic text condensation | m = 77 (67–84) | 16 (76) | 21 (100) | 17 (81) |

| Wong [72] | Clinicians’ perspectives of patient engagement in post-acute care: A social ecological approach | Community | 99 Clinicians | 13 Focus Group, Face-to-face | Grounded Theory | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wykes [73] | The concerns of older women during inpatient rehabilitation after fractured neck of femur | Subacute | 5 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Thematic analysis | 74 (60–79) | 5 (100) | NA | NR |

| Young [74] | Don’t worry, be positive: Improving functional recovery 1 year after hip fracture | Post-hip fracture | 62 PwHF | Thematic survey, Individual | Basic content analysis | m = 78 (65–91) | 40 (76) | 62 (100) | 28 (45) |

| Ziden [75] | The break remains—elderly people’s experiences of a hip fracture 1 year after discharge | Post-hip fracture | 15 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenographic | 79 (66–94) | 13 (87) | 15 (100) | 10 (67) |

| Ziden [76] | A life-breaking event: Early experiences of the consequences of a hip fracture for elderly people | Community | 18 PwHF | Semi-structured interviews, Individual, Face-to-face | Phenomenographic | 80 (65–99) | 16 (89) | 18 (100) | 14 (78) |

Note:

NA = Not applicable

NR = Not reported

a = Estimated age range based on reported age groups or inclusion criteria, actual range not reported

m = mean

SD = standard deviation

# = hip fracture, dc = discharge, wk = week, m = month, PwHF -Participants with hip fracture

Acute = up to 2 weeks after hip fracture; Subacute = greater than 2 weeks post-hip fracture and before community; Community = after sub-acute until 12 months post-hip fracture; Post-hip fracture = after 12 months post-hip fracture

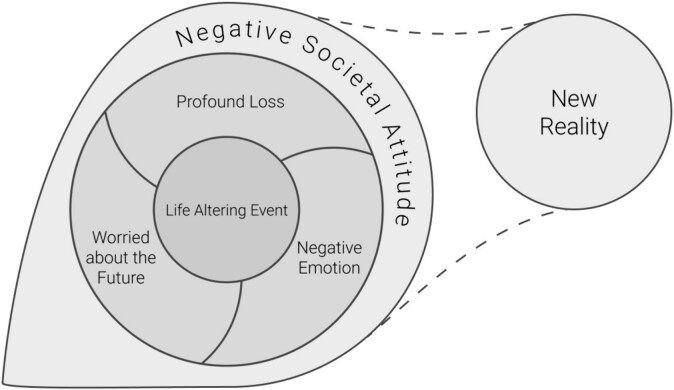

Thematic synthesis

The overarching theme identified was that hip fracture was viewed as a life-altering event. After hip fracture, people experienced a profound sense of loss, expressed pervasive and ongoing negative emotions and were very worried about the future (sub-themes). Affecting these negative experiences was a negative societal attitude (theme). For some people, with time, there was a sense of acceptance of their new reality (theme) (Figure 2) (Appendix 6).

Figure 2.

Thematic synthesis of psychosocial experiences after a hip fracture.

Life-altering event

Hip fracture was regarded as a life-altering event that encompassed major disruptions. Many people who were previously active and able to participate in the community were forced to adapt to a new reality, where they could no longer do things they wanted to do, the way they wanted to do them.

“It’s altered my whole life, believe me.” (Participant with hip fracture) [67]

“I do not think I will return to my former life.” (Participant with hip fracture) [30]

This life-altering event typically began as a traumatic fall, followed by a negative hospital experience. People talked about feeling vulnerable, helpless, scared, and not being valued as a person during the perioperative phase. Some people experienced existential questions after this traumatic event and questioned the change in their identity.

“I will never be the person I was before the fracture. I used to be in good shape, despite my age. Now I ask myself: What is there really to look forward to when you are ninety?” (Participant with hip fracture) [30]

The inability to resume their life after a hip fracture forced people to adapt to a restricted life.

“Right after the hospital, I had a psychological adjustment to the whole thing. After 70 years of walking and having freedom, being confined and the mobility issue … ” (Participant with hip fracture) [49]

“They said I am old and had better retire. They didn’t let me keep managing my factory. At first I felt really angry, but now I don’t want to argue with them. I know my vitality is worse than before; I have no other choice but to accept my present physical condition.” (Participant with hip fracture) [40]

A sense of loss

A profound sense of loss was voiced by many participants throughout hip fracture recovery. People said they had to grapple with the psychological and social implications of hip fracture, including the loss of autonomy, physical ability and for some, the loss of their home, work, and vibrant social life.

“I’m not as capable as everybody else… like I let the side down… feel like I’ve aged fifteen years…” (Participant with hip fracture) [42]

“I’m more house-bound. So I’ve become more of a recluse, I suppose.... It’s my social life that suffers.” (Participant with hip fracture) [75]

Negative emotions

After a hip fracture, there was an overwhelming negative emotion ranging from feelings of gloominess to frustration and loss of confidence especially as they progressed from the acute to the community setting.

“I have nothing to look forward to and I’ll lay here till I die.” (Participant with hip fracture) [29]

“After the hip fracture I have felt depressed for the first time in my life. I feel totally empty. And the gloominess persists even now (four months after the fracture). It is like having fallen into a black hole and being unable to get up again” (Participant with hip fracture) [30]

…if I’m going to be like this for the rest of my life I don’t want to live.” (Participant with hip fracture) [67]

Further, some people felt frustrated with the pace of their recovery, which led to disappointment, dashed expectations, loss of confidence and feelings of resignation.

“My expectations for my own recovery were much higher than reality, and that have made me frustrated and impatient”. (Participant with hip fracture) [30]

“I would say I had more disappointments than surprises. It seems that it’s taking a very long time to me” (Participant with hip fracture) [49]

Worried about the future

The predominant emotion people talked about after hip fracture was feeling worried—about the operation, fear of falling, dependency, and fear of the future.

“Will I ever be able to walk again?”, “Will I ever be in control of the fracture?”, or “Will I ever be able to control my everyday life again?” (Participants with hip fracture) [21]

People feared being alone and socially isolated, and they worried about being dependent on their friends and a burden to their family.

“I don't want to be an invalid . . . I'm too much on my own. I'd rather for the Lord to close my eyes tonight and let me go to rest.” (Participant with hip fracture) [31]

“[my daughter is] ... taking care of me. I feel like that's a big burden... she bathes me. She gives me a shower, sets my hair. That's a lot. Cause she's got a baby to take care of.” (Participant with hip fracture) [31]

For some people, the fear of being a burden on others meant they masked their psychosocial distress so as not to worry others.

“When you have visitors you don’t… you don’t sort of say what your feeling… you try to keep a brave face… and the other ladies in the ward, you don’t say anything to them because they’ve got their own problems.” (Participant with hip fracture) [73].

Negative societal attitude

People after hip fracture perceived a pervasive negative attitude or stigma toward them, from the healthcare staff to family and friends in the community. People said they often felt neglected and ignored, humiliated, and stigmatised because they had a hip fracture. This left them feeling dehumanised and dejected, and lowered their expectations of recovery.

“I said oh I want to go to the toilet. Argh and they said, well we’re very sorry but we can’t do anything [laughter]. So you had to hold it? No, I just had to do it... Oh it was awful. I couldn’t believe it” (Participant with hip fracture) [48]

“My neighbour saw me moving slowly with the walker. She came to me, stood there watching me, shook her head and said, ‘Oh! Now you use this [walker]. You look so old, really like an ugly old grandma’.” (Participant with hip fracture) [40]

Acceptance over time

Some, but not all, participants described a transition over many months from negative emotions to acceptance. This group said they managed to gain a sense of acceptance through gratitude, optimism, resilience and the support of family and friends.

“Yes, because then I’ll just make changes to some of the things I CAN do. For example […] these entertainments nights; I can’t dance and jump around, but I can BE there […] see the joy of life other people have. And what they are able to do, even if I’m not able to the same, it’s kind of comforting.” (Participant with hip fracture) [56]

“I don’t get hung up on small things...I’ve gotten a perspective on life. I’ve learned to be grateful. ...I think you learn things all your life. Because, in spite of everything, I’m healthy.” (Participant with hip fracture) [76]

For others, the new reality of life after hip fracture remained negative even several years after the fall.

“I feel that I’ve aged too quickly […], all of a sudden now you can’t drive anymore, boom! … you don’t have the strength to go and rake in your garden; boom! You can’t make your own food; ... little by little, you can’t do it anymore.” (Participant with hip fracture) [58]

GRADE-CERQual assessment of findings

There was moderate to high confidence in the themes and sub-themes identified (Table 3) (see Appendix 7 for detailed CerQual findings).

Table 3.

Confidence in the evidence from reviews of qualitative research (CERQual) summary of qualitative findings.

| Summary of review finding | Studies contributing to the review finding | CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of CERQual assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[21, 23–25, 28–33, 35–40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48–56, 59, 61, 63, 65–67, 70, 71, 73, 75–77] | Moderate confidence | 41 studies with moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy, and relevance. |

|

[21–23, 25, 29–32, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42–54, 56–63, 66–68, 70, 72, 73, 75–77] | High confidence | 42 studies with minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy, and relevance. |

|

[21–33, 35–37, 39, 40, 42–68, 70–73, 75–77] | Moderate confidence | 52 studies with moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concerns regarding relevance (findings may differ based on temporal context (acute, subacute, community or post-hip fracture)). No or very minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy. |

|

[21–24, 26, 27, 30–39, 41–59, 61, 62, 65–73, 75, 76] | Moderate confidence | 48 studies with moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concerns regarding relevance (findings may differ based on temporal context (acute, subacute, community or post-hip fracture)). No or very minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy. |

|

[22–25, 27, 30, 35–37, 39–48, 50–58, 60–63, 65, 66, 70, 73, 76] | Moderate confidence | 37 studies with minor concern regarding coherence (some concerns about the fit between the data from primary studies and the review findings). Minor concerns regarding relevance (findings may differ based on cultural context). Studies included were mostly of developed nations, although diverse cultures were explored (Asian, European, American, and Australian). No or very minor concerns regarding adequacy. |

|

[21–24, 26, 28, 29, 31–34, 37, 38, 42, 46, 48, 49, 51, 54, 56–60, 64–66, 70, 71, 73–77] | Moderate confidence | 34 studies with moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concern regarding coherence (some concerns about the fit between the data from primary studies and the review findings). Minor concerns about relevance (findings may differ based on temporal context (acute, subacute, community or post-hip fracture)). No or very minor concerns regarding adequacy. |

Discussion

We found moderate to high confidence evidence from a synthesis of 57 qualitative studies that hip fracture is a life altering event with profound psychosocial impacts. For some people, there is a slow acceptance of a new reality. These findings add to the literature by highlighting the depth and extent of impaired psychosocial functioning after hip fracture and suggest a high likelihood that this could negatively impact recovery after hip fracture. Current hip fracture clinical practice guidelines provide no recommendations on the assessment and management of psychosocial functioning nor list it as a recommended area of research [10, 11]. This appears to be a notable omission.

The psychosocial impact of hip fracture is consistent with the affective, cognitive and behavioural reactions associated with trauma [78, 79]. Cognitive reactions in response to trauma can result in a triad of traumatic stress, with negative views about self, the future and the world, including other people and the environment [78]. The identified themes in our review could be regarded as reactions of traumatic stress. When formally assessed against diagnostic criteria, previous studies have reported that post-traumatic stress disorder is rare after hip fracture [80]. However, despite the lack of clinical diagnosis, the current study demonstrates that the negative psychosocial impacts after hip fracture are widespread, profound, prolonged and indicative of traumatic stress.

Given the extent of the psychosocial impacts of hip fracture identified in this review, there may be a case for health service providers to place greater emphasis on providing targeted interventions to address these needs, consistent with the management of other conditions involving traumatic stress. This is important given the associations established between psychosocial functioning and recovery after hip fracture [12, 13, 15]. Tools are already available for clinicians to assess and monitor people at risk of psychosocial distress [12, 80]. For example, higher subscale scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale are associated with psychological distress [81] and perceived functional support, as measured by the Medical Outcome Study-Social Support Survey, has been associated with recovery after hip fracture [82]. This review suggests there may be a place for routine use of such tools to identify psychosocial risk factors during hip fracture rehabilitation in order to deliver appropriate interventions.

Specialist psychosocial care may not be warranted for everyone who experiences a hip fracture. There is a subgroup of people who have a relatively rapid and full functional recovery after hip fracture, who may not experience high degrees of impaired psychological functioning [83]. For those at low risk, expert clinicians providing empathic, person-centred and collaborative care, who listen to their patients and understand the context of their lives, may provide sufficient psychosocial support for people after hip fracture to find their way to the ‘new normal’ described in this review [84]. Also, some of the psychosocial impact of hip fracture may be reduced by addressing the broader societal context, experienced as uncaring attitudes and ageism from clinicians and families, that can be particularly damaging for people at a time of vulnerability [85, 86].

For those people who are identified as being in need of psychological interventions after hip fracture, current research does not provide any certainty about the best way to provide this support [87]. There is limited evidence from two trials with small sample sizes on the effect of psychological interventions following hip fracture; one study reported non-significant findings on the effect of cognitive behaviour therapy on fear of falling and mobility outcomes [88] and another reported increased physical activity and self-efficacy after an 8-week motivational interviewing intervention [8]. There is a need for large trials using stepped approaches to care or comparing different interventions to determine the best ways to provide support and improve outcomes for this vulnerable group.

Strength of this review is that it is based on a large body of evidence with moderate to high confidence in the findings. Our review was prospectively registered and reported consistent with PRISMA and ENTREQ [17]. Limitations were that the review did not include publications in the grey literature, which may have led to some evidence being missed. Papers published in languages other than English were also excluded, although no papers excluded for this reason appeared likely to meet other inclusion criteria. In addition, none of the included studies were from low-income countries so it is uncertain to what extent our findings can be generalised to these settings. However, the review did include studies from countries with different cultures. Finally, this review of qualitative data does not attempt to quantify the proportion of people who have different experiences of recovery, or to identify specific risk factors for psychological distress in people after hip fracture. These are important questions and opportunities for further research.

In conclusion, hip fracture is a life altering event characterised by a profound sense of loss, negative emotions and worry about the future. The assessment and management of psychosocial functioning after hip fracture has received little attention in clinical practice guidelines. Assessing and treating psychosocial functioning may be an important component in providing optimal care to improve outcomes after hip fracture.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Nicholas F Taylor, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; Allied Health Clinical Research Office, Eastern Health, 2/5 Arnold Street, Box Hill, Victoria 3128, Australia.

Made U Rimayanti, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3086, Australia.

Casey L Peiris, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Melbourne 3052, Victoria Australia.

David A Snowdon, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; Academic Unit, Peninsula Health, Frankston, Victoria 3133, Australia.

Katherine E Harding, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; Allied Health Clinical Research Office, Eastern Health, 2/5 Arnold Street, Box Hill, Victoria 3128, Australia.

Adam I Semciw, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia; Allied Health, Northern Health, Epping, Victoria 3076, Australia.

Paul D O’Halloran, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3086, Australia; Centre for Sport and Social Impact, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3086, Australia.

Elizabeth Wintle, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia.

Scott Williams, Academic and Research Collaborative in Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia.

Nora Shields, Olga Tennison Autism Research Centre, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3086, Australia.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

The study was supported by a small internal grant from La Trobe University.

References

- 1. Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry . ANZHFR Annual Report of Hip Fracture Care. Sydney: Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry, 2023. Available: https://anzhfr.org/registry-reports/ (09 April 2024, date last accessed).

- 2. Leung MT, Marquina C, Turner JPet al. Hip fracture incidence and post-fracture mortality in Victoria, Australia: a state-wide cohort study. Arch Osteoporos. 2023;18:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hawley S, Inman D, Gregson CLet al. Predictors of returning home after hip fracture: a prospective cohort study using the UK national hip fracture database (NHFD). Age Ageing. 2022;51:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tang VL, Sudore R, Cenzer ISet al. Rates of recovery to pre-fracture function in older persons with hip fracture: an observational study. J Gen Int Med. 2017;32:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiese-Bjornstal DM. Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statement. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20:103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Freedman A, Nicolle J. Social isolation and loneliness: the new geriatric giants: approach for primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66:176–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olive P, Hives L, Wilson Net al. Psychological and psychosocial aspects of major trauma care in the United Kingdom: a scoping review of primary research. Dent Traumatol. 2023;25:338–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Halloran PD, Shields N, Blackstock Fet al. Motivational interviewing increases physical activity and self-efficacy in people living in the community after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:1108–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation: Module 2: Musculoskeletal Conditions. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2023. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240071100 (09 April 2024, date last accessed).

- 10. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) . The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults [Internet]. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK), 2011, PMID: 22420011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDonough CM, Harris-Hayes M, Kristensen MTet al. Physical therapy management of older adults with hip fracture: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the academy of Orthopaedic physical therapy and the academy of geriatric physical therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51:1–81.33383998 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Auais M, Sousa TAC, Feng Cet al. Understanding the relationship between psychological factors and important health outcomes in older adults with hip fracture: a structured scoping review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;101:104666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Auais M, Al-Zoubi F, Matheson Aet al. Understanding the role of social factors in recovery after hip fractures: a structured scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27:1375–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liamputtong P, Rice ZS. Qualitative Research in Global Health Research. In: Haring R, Kickbusch I, Ganten D, Moeti M (eds.), Handbook of Global Health. Singapore: Springer, 2021, 213–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beer N, Riffat A, Volkmer Bet al. Patient perspectives of recovery after hip fracture: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:6194–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes Eet al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PMet al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . CASP Checklist: 10 Questions to Help you Make Sense of a Qualitative Research. Oxford: CASP UK - OAP, 2018. Available: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (09 april 2024, date last accessed).

- 19. Lachal J, Revah-Levy A, Orri Met al. Metasynthesis: an original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Front Psych. 2017;8:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton Cet al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abrahamsen C, Viberg B, Nørgaard B. Patients’ perspectives on everyday life after hip fracture: a longitudinal interview study. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2022;44:100918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ansah JP, Chia AW-Y, Koh VJWet al. Systems modelling as an approach for eliciting the mechanisms for hip fracture recovery among older adults in a participatory stakeholder engagement setting. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1184484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Archibald G. Patients’ experiences of hip fracture. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Asplin G, Carlsson G, Fagevik Olsén Met al. See me, teach me, guide me, but it’s up to me! Patients’ experiences of recovery during the acute phase after hip fracture. Eur J Physiother. 2021;23:135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ballinger C, Payne S. Falling from grace or into expert hands? Alternative accounts about falling in older people. Brit J Occ Ther. 2000;63:573–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bergh I, Jakobsson E, Sjöström Bet al. Ways of talking about experiences of pain among older patients following orthopaedic surgery. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bishop S, Waring J. From boundary object to boundary subject; the role of the patient in coordination across complex systems of care during hospital discharge. Soc Sci Med. 2019;235:112370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borkan JM, Quirk M. Expectations and outcomes after hip fracture among the elderly. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1992;34:339–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borkan JM, Quirk M, Sullivan M. Finding meaning after the fall: injury narratives from elderly hip fracture patients. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruun-Olsen V, Bergland A, Heiberg KE. “I struggle to count my blessings”: recovery after hip fracture from the patients’ perspective. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Furstenberg A-L. Expectations about outcome following hip fracture among older people. Soc Work Health Care. 1986;11:33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gesar B, Baath C, Hedin Het al. Hip fracture; an interruption that has consequences four months later. A qualitative study. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2017;26:43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gesar B, Hommel A, Hedin Het al. Older patients' perception of their own capacity to regain pre-fracture function after hip fracture surgery–an explorative qualitative study. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2017;24:50–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gorman E, Chudyk AM, Hoppmann CAet al. Exploring older adults' patterns and perceptions of exercise after hip fracture. Physiother Can. 2013;65:86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Griffiths F, Mason V, Boardman Fet al. Evaluating recovery following hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of what is important to patients. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e005406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guilcher SJ, Everall AC, Cadel Let al. A qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of deconditioning in hospital in Ontario, Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gunnarsson A-K, Larsson J, Gunningberg L. Hip-fracture patients’ experience of involvement in their care: a qualitative study. Int J Person Cent Med. 2014;4:106–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haslam-Larmer L, Donnelly C, Auais Met al. Early mobility after fragility hip fracture: a mixed methods embedded case study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hommel A, Kock M-L, Persson Jet al. The patient's view of nursing care after hip fracture. ISRN Nurs. 2012;2012:863291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang Y-F, Liang J, Shyu Y-IL. Ageism perceived by the elderly in Taiwan following hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ivarsson B, Hommel A, Sandberg Met al. The experiences of pre-and in-hospital care in patients with hip fractures: a study based on critical incidents. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2018;30:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Janes G, Serrant L, Sque M. Fragility hip fracture in the under 60s: a qualitative study of recovery experiences and the implications for nursing. J Trauma Orthop Nurs. 2018;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jellesmark A, Herling SF, Egerod Iet al. Fear of falling and changed functional ability following hip fracture among community-dwelling elderly people: an explanatory sequential mixed method study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jensen CM, Santy-Tomlinson J, Overgaard Set al. Empowerment of whom? The gap between what the system provides and patient needs in hip fracture management: a healthcare professionals’ lifeworld perspective. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2020;38:100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen CM, Smith AC, Overgaard Set al. “If only had I known”: a qualitative study investigating a treatment of patients with a hip fracture with short time stay in hospital. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2017;12:1307061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Karlsson Å, Olofsson B, Stenvall Met al. Older adults' perspectives on rehabilitation and recovery one year after a hip fracture–a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Killington M, Walker R, Crotty M. The chaotic journey: recovering from hip fracture in a nursing home. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ko YJ, Lee JH, Baek S-H. Discharge transition experienced by older Korean women after hip fracture surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Langford D, Edwards N, Gray SMet al. “Life goes on.” everyday tasks, coping self-efficacy, and independence: exploring older adults’ recovery from hip fracture. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:1255–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li H-J, Shyu Y-IL. Coping processes of Taiwanese families during the postdischarge period for an elderly family member with hip fracture. Nurs Sci Quart. 2007;20:273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McMillan L, Booth J, Currie Ket al. A grounded theory of taking control after fall-induced hip fracture. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McMillan L, Booth J, Currie Ket al. ‘Balancing risk’after fall-induced hip fracture: the older person's need for information. Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel V, Lindenmeyer A, Gao Fet al. A qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of patients living with mild, moderate and severe frailty, following hip fracture surgery and hospitalisation. PloS One. 2023;18:e0285980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pol M, Peek S, Nes Fet al. Everyday life after a hip fracture: what community-living older adults perceive as most beneficial for their recovery. Age Ageing. 2019;48:440–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pownall E. Using a patient narrative to influence orthopaedic nursing care in fractured hips. J Orthop Nurs. 2004;8:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rasmussen B, Nielsen CV, Uhrenfeldt L. Being active after hip fracture; older people’s lived experiences of facilitators and barriers. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2018;13:1554024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rasmussen B, Nielsen CV, Uhrenfeldt L. Being active 1½ years after hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of aged adults’ experiences of meaningfulness. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rasmussen B, Nielsen CV, Uhrenfeldt L. Enduring life in between a sense of renewal and loss of courage: lifeworld perspectives one year after hip fracture. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2021;16:1934996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Roberts JL, Din NU, Williams Met al. Development of an evidence-based complex intervention for community rehabilitation of patients with hip fracture using realist review, survey and focus groups. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Robinson SB. Transitions in the lives of elderly women who have sustained hip fractures. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:1341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sandberg M, Ivarsson B, Johansson Aet al. Experiences of patients with hip fractures after discharge from hospital. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2022;46:100941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schiller C, Franke T, Belle Jet al. Words of wisdom–patient perspectives to guide recovery for older adults after hip fracture: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Segevall C, Söderberg S, Randström KB. The journey toward taking the day for granted again: the experiences of rural older people's recovery from hip fracture surgery. Orthop Nurs. 2019;38:359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sims-Gould J, Stott-Eveneshen S, Fleig Let al. Patient perspectives on engagement in recovery after hip fracture: a qualitative study. J Aging Res. 2017;2017:217865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Southwell J, Potter C, Wyatt Det al. Older adults’ perceptions of early rehabilitation and recovery after hip fracture surgery: a UK qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:939–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Strøm Rönnquist S, Svensson HK, Jensen CMet al. Lingering challenges in everyday life for adults under age 60 with hip fractures–a qualitative study of the lived experience during the first three years. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2023;18:2191426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Taylor NF, Barelli C, Harding KE. Community ambulation before and after hip fracture: a qualitative analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taylor NF, Harding KE, Dowling Jet al. Discharge planning for patients receiving rehabilitation after hip fracture: a qualitative analysis of physiotherapists' perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Turner N, Dinh JM, Durham Jet al. Development of a questionnaire to assess patient priorities in hip fracture care. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2020;11:2151459320946009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tutton E, Saletti-Cuesta L, Langstaff Det al. Patient and informal carer experience of hip fracture: a qualitative study using interviews and observation in acute orthopaedic trauma. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vestøl I, Debesay J, Bergland A. The journey of recovery after hip-facture surgery: older people's experiences of recovery through rehabilitation services involving physical activity. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:5468–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wong C, Leland NE. Clinicians' perspectives of patient engagement in post-acute care: a social ecological approach. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2018;36:29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wykes C, Pryor J, Jeeawody B. The concerns of older women during inpatient rehabilitation after fractured neck of femur. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16:261–70. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Young Y, Resnick B. Don't worry, be positive: improving functional recovery 1 year after hip fracture. Rehabil Nurs. 2009;34:110–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zidén L, Scherman MH, Wenestam CG. The break remains – elderly people's experiences of a hip fracture 1 year after discharge. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zidén L, Wenestam CG, Hansson-Scherman M. A life-breaking event: early experiences of the consequences of a hip fracture for elderly people. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:801–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moraes SA, Furlanetto EC, Ricci NAet al. Sedentary behavior: barriers and facilitators among older adults after hip fracture surgery. A qualitative study. Braz. J Phys Ther. 2020;24:407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US) . Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57). Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/ (09 april 2024, date last accessed). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pozzato I, Tran Y, Gopinath Bet al. The role of stress reactivity and pre-injury psychosocial vulnerability to psychological and physical health immediately after traumatic injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;127:105190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kornfield SL, Lenze EJ, Rawson KS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms and association with fear of falling after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TTet al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhu Y, Xu BY, Low SGet al. Association of social support with rehabilitation outcome among older adults with hip fracture surgery: a prospective cohort study at post-acute care facility in Asia. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2023;24:1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Noeske KE, Snowdon DA, Ekegren CLet al. Walking self-confidence and lower levels of anxiety are associated with meeting recommended thresholds of physical activity after hip fracture: a cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabil. 2024;Apr 18:1–7. (accepted 28 March 2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Shepard KFet al. Expert practice in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2000;80:28–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hill TE. How clinicians make (or avoid) moral judgments of patients: implications of the evidence for relationships and research. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2010;5:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jeyasingam N, McLean L, Mitchell Let al. Attitudes to ageing amongst health care professionals: a qualitative systematic review. Euro Geriatr Med. 2023;14:889–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Crotty M, Unroe K, Cameron IDet al. Rehabilitation interventions for improving physical and psychosocial functioning after hip fracture in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD007624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Scheffers-Barnhoorn MN, Eijk M, Haastregt JCet al. Effects of the FIT-HIP intervention for fear of falling after HIP fracture: a cluster-randomized controlled trial in geriatric rehabilitation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:857–865.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.