Abstract

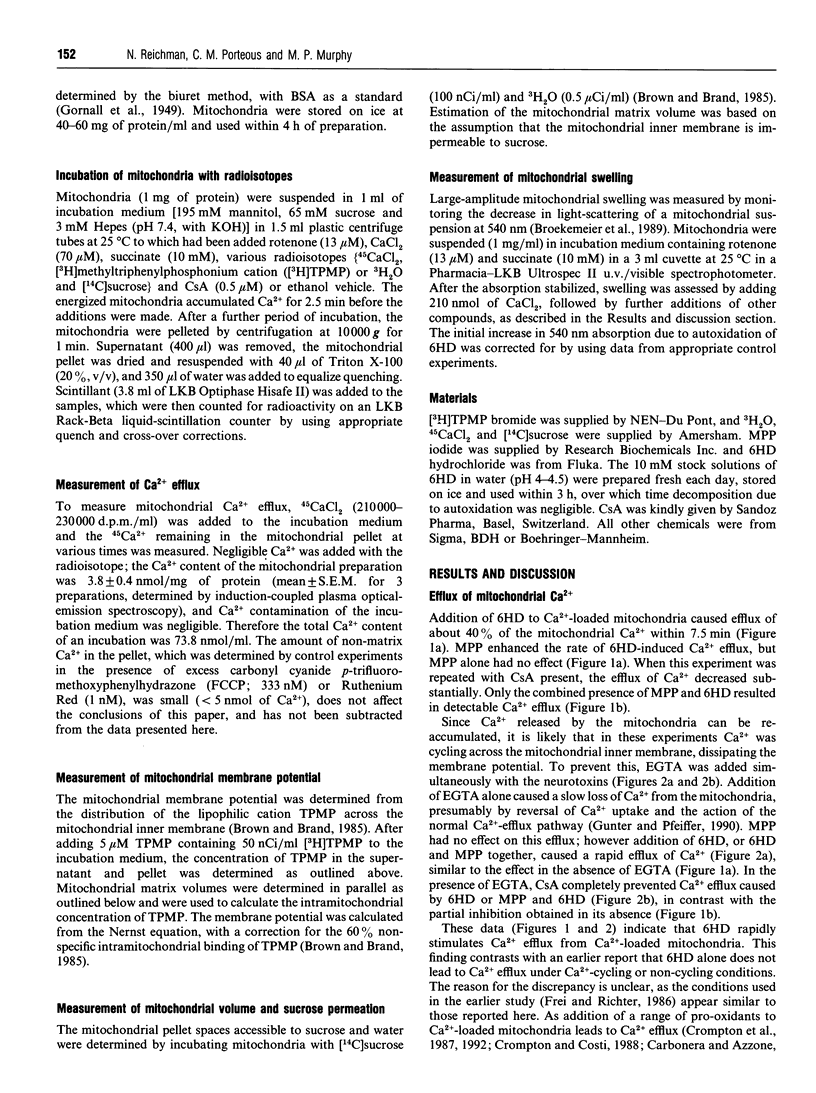

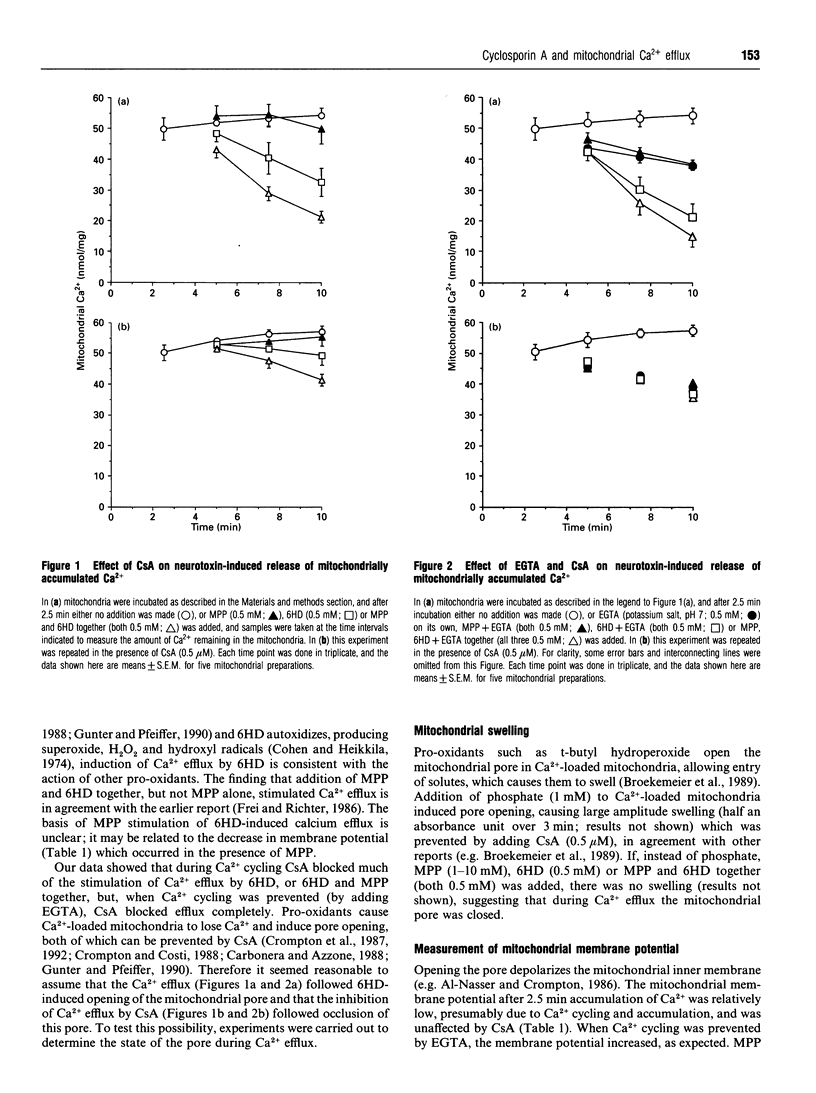

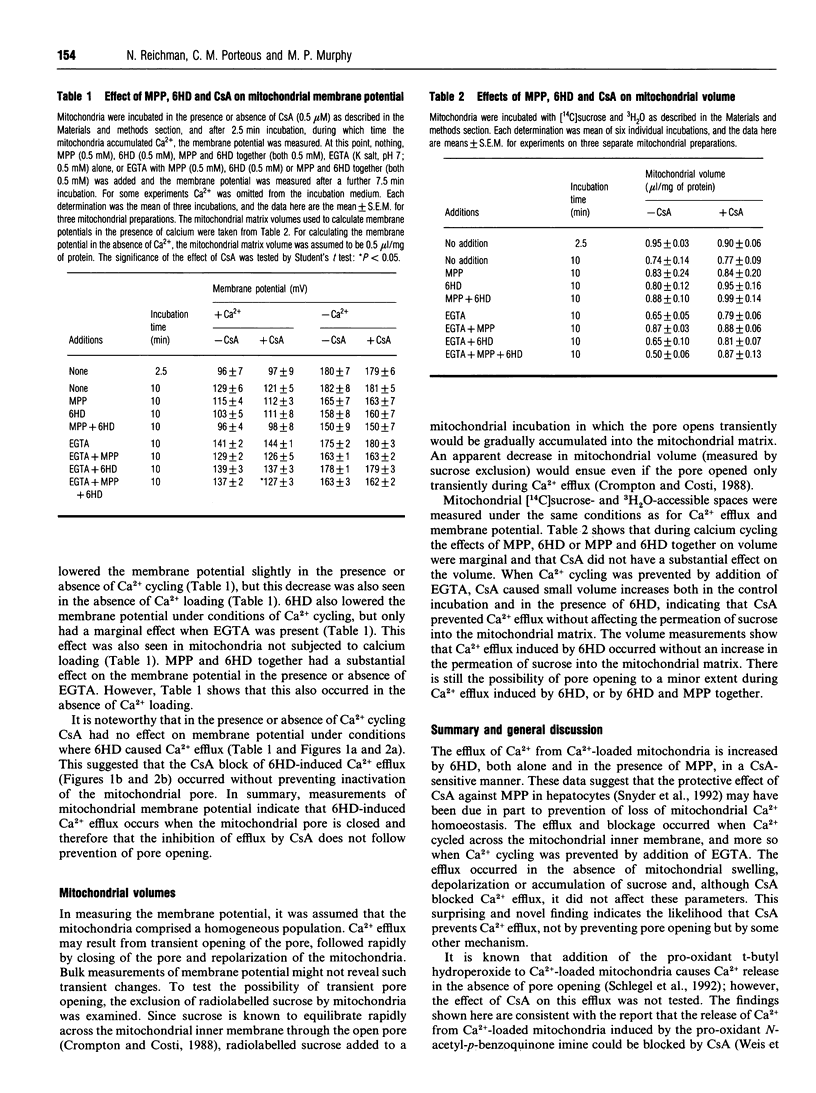

Oxidative stress causes Ca(2+)-loaded mitochondria to release Ca2+. The mechanism of this efflux is unclear, but it appears to be associated with the opening of a pore in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Pore opening depolarizes the mitochondria, letting solutes enter the mitochondrial matrix, causing swelling. Cyclosporin A (CsA) prevents opening of this pore. The neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (6HD) autoxidizes, producing free radicals, which cause oxidative stress. In this paper it is shown that 6HD-induced efflux from Ca(2+)-loaded mitochondria was prevented by CsA. The 6HD-induced Ca2+ efflux was not accompanied by mitochondrial swelling, depolarization of the mitochondrial inner membrane or movement of radiolabelled sucrose into the mitochondrial matrix. In agreement with others [Schlegel, Schweizer and Richter (1992) Biochem. J. 285, 65-69], these findings suggest that the mitochondrial pore remained closed during pro-oxidant-induced Ca2+ efflux. However, the implication that CsA blocks pro-oxidant-induced Ca2+ efflux by some mechanism other than inactivating the mitochondrial pore, suggests that the interaction of CsA with mitochondria may be more complex than is currently supposed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Al-Nasser I., Crompton M. The reversible Ca2+-induced permeabilization of rat liver mitochondria. Biochem J. 1986 Oct 1;239(1):19–29. doi: 10.1042/bj2390019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore by the proton electrochemical gradient. Evidence that the pore can be opened by membrane depolarization. J Biol Chem. 1992 May 5;267(13):8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi P., Veronese P., Petronilli V. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore. I. Evidence for two separate Me2+ binding sites with opposing effects on the pore open probability. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jan 15;268(2):1005–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekemeier K. M., Carpenter-Deyo L., Reed D. J., Pfeiffer D. R. Cyclosporin A protects hepatocytes subjected to high Ca2+ and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 1992 Jun 15;304(2-3):192–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80616-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekemeier K. M., Dempsey M. E., Pfeiffer D. R. Cyclosporin A is a potent inhibitor of the inner membrane permeability transition in liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1989 May 15;264(14):7826–7830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. C., Brand M. D. Thermodynamic control of electron flux through mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochem J. 1985 Jan 15;225(2):399–405. doi: 10.1042/bj2250399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonera D., Azzone G. F. Permeability of inner mitochondrial membrane and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Aug 18;943(2):245–255. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G., Heikkila R. E. The generation of hydrogen peroxide, superoxide radical, and hydroxyl radical by 6-hydroxydopamine, dialuric acid, and related cytotoxic agents. J Biol Chem. 1974 Apr 25;249(8):2447–2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connern C. P., Halestrap A. P. Purification and N-terminal sequencing of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase from rat liver mitochondrial matrix reveals the existence of a distinct mitochondrial cyclophilin. Biochem J. 1992 Jun 1;284(Pt 2):381–385. doi: 10.1042/bj2840381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M., Costi A., Hayat L. Evidence for the presence of a reversible Ca2+-dependent pore activated by oxidative stress in heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1987 Aug 1;245(3):915–918. doi: 10.1042/bj2450915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M., Costi A. Kinetic evidence for a heart mitochondrial pore activated by Ca2+, inorganic phosphate and oxidative stress. A potential mechanism for mitochondrial dysfunction during cellular Ca2+ overload. Eur J Biochem. 1988 Dec 15;178(2):489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte D., Jewell S. A., Ekström G., Sandy M. S., Smith M. T. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MPP+) cause rapid ATP depletion in isolated hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986 May 29;137(1):310–315. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)91211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei B., Richter C. N-methyl-4-phenylpyridine (MMP+) together with 6-hydroxydopamine or dopamine stimulates Ca2+ release from mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1986 Mar 17;198(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M., Riederer P., Przuntek H., Youdim M. B. MPTP mechanisms of neurotoxicity and their implications for Parkinson's disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991 Dec 12;208(4):273–286. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90073-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Pfeiffer D. R. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol. 1990 May;258(5 Pt 1):C755–C786. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.5.C755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa E., Takeshige K., Oishi T., Murai Y., Minakami S. 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) induces NADH-dependent superoxide formation and enhances NADH-dependent lipid peroxidation in bovine heart submitochondrial particles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Aug 16;170(3):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90498-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Oxidative stress as a cause of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1991;136:6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1991.tb05013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass G. E., Wright J. M., Nicotera P., Orrenius S. The mechanism of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine toxicity: role of intracellular calcium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988 Feb 1;260(2):789–797. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazareth W., Yafei N., Crompton M. Inhibition of anoxia-induced injury in heart myocytes by cyclosporin A. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991 Dec;23(12):1351–1354. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90181-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas W. J., Vyas I., Heikkila R. E. Inhibition of NADH-linked oxidation in brain mitochondria by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine, a metabolite of the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine. Life Sci. 1985 Jul 1;36(26):2503–2508. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novgorodov S. A., Gudz T. I., Milgrom Y. M., Brierley G. P. The permeability transition in heart mitochondria is regulated synergistically by ADP and cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 1992 Aug 15;267(23):16274–16282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli V., Cola C., Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore. II. The minimal requirements for pore induction underscore a key role for transmembrane electrical potential, matrix pH, and matrix Ca2+. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jan 15;268(2):1011–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay R. R., Singer T. P. Relation of superoxide generation and lipid peroxidation to the inhibition of NADH-Q oxidoreductase by rotenone, piericidin A, and MPP+. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992 Nov 30;189(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91523-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C., Frei B. Ca2+ release from mitochondria induced by prooxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;4(6):365–375. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel J., Schweizer M., Richter C. 'Pore' formation is not required for the hydroperoxide-induced Ca2+ release from rat liver mitochondria. Biochem J. 1992 Jul 1;285(Pt 1):65–69. doi: 10.1042/bj2850065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T. P., Ramsay R. R. Mechanism of the neurotoxicity of MPTP. An update. FEBS Lett. 1990 Nov 12;274(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81315-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. W., Pastorino J. G., Attie A. M., Farber J. L. Protection by cyclosporin A of cultured hepatocytes from the toxic consequences of the loss of mitochondrial energization produced by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992 Aug 18;44(4):833–835. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90425-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. E., Reed D. J. Current status of calcium in hepatocellular injury. Hepatology. 1989 Sep;10(3):375–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M., Kass G. E., Orrenius S., Moldéus P. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine induces Ca2+ release from mitochondria by stimulating pyridine nucleotide hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1992 Jan 15;267(2):804–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang L. Y., Misra H. P. Superoxide radical production during the autoxidation of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridinium perchlorate. J Biol Chem. 1992 Sep 5;267(25):17547–17552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]