Abstract

目的

探究双氢青蒿素(DHA)与顺铂(DDP)联合应用对耐DDP鼻咽癌细胞株HNE1/DDP增殖抑制和促凋亡的作用及其机制。

方法

CCK-8法检测不同浓度DHA(0、5、10、20、40、80、160 μmol/L)和不同浓度DDP(0、4、8、16、32、64、128 μmol/L)处理24 h和48 h后HNE1/DDP细胞的存活率;采用Compusyn软件计算DHA与DDP的联合指数。将HNE1/DDP细胞分为对照组、DHA组、DDP组、DHA联合DDP组,给药处理24 h后,CCK-8、EdU和集落克隆形成实验分别检测细胞活力、细胞增殖和集落克隆形成能力;流式细胞术检测细胞凋亡情况和细胞内活性氧(ROS)水平;Western blotting检测凋亡相关蛋白Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-9、Cleaved Caspase-3表达水平。ROS抑制剂N-乙酰半胱氨酸预处理后,检测其对DHA联合DDP诱导的细胞增殖、凋亡的影响。

结果

不同浓度DHA和不同浓度DDP均能明显抑制HNE1/DDP细胞活力,DHA(5 μmol/L)联合DDP(8、16、32、64、128 μmol/L)的联合指数均小于1。与DHA或DDP单独处理组相比,DHA联合DDP组细胞活力下降(P<0.01),集落形成数和EdU阳性染色细胞减少(P<0.01),细胞凋亡率和细胞内ROS水平升高(P<0.01),细胞凋亡相关蛋白Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-9、Cleaved Caspase-3的表达水平增加(P<0.05),而N-乙酰半胱氨酸预处理可部分逆转DHA联合DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的增殖抑制和凋亡诱导作用(P<0.01)。

结论

DHA增强DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的增殖抑制和凋亡诱导作用,其机制可能与细胞内ROS的积累有关。

Keywords: 鼻咽癌, 双氢青蒿素, 顺铂, 活性氧, 增殖, 细胞凋亡

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effect of dihydroartemisinin (DHA) for enhancing the inhibitory effect of cisplatin (DDP) on DDP-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line HNE1/DDP and explore the mechanism.

Methods

CCK-8 method was used to assess the survival rate of HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 μmol/L) and DDP (0, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 μmol/L) for 24 or 48 h, and the combination index of DHA and DDP was calculated using Compusyn software. HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA, DDP, or their combination for 24 h were examined for cell viability, proliferation and colony formation ability using CCK-8, EdU and colony-forming assays. Flow cytometry was used to detect cell apoptosis and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). The expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-9 and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by Western blotting. The effects of N-acetyl-cysteine (a ROS inhibitor) on proliferation and apoptosis of HNE1/DDP cells with combined treatment with DHA and DDP were analyzed.

Results

Different concentrations of DHA and DDP alone both significantly inhibited the viability of HNE1/DDP cells. The combination index of DHA (5 μmol/L) combined with DDP (8, 16, 32, 64, 128 μmol/L) were all below 1. Compared with DHA or DDP alone, their combined treatment more potently decreased the cell viability, colony-forming ability and the number of EdU-positive cells, and significantly increased the apoptotic rate, intracellular ROS level, and the expression levels of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-9 and cleaved caspase-3 in HNE1/DDP cells. N-acetyl-cysteine pretreatment obviously attenuated the inhibitory effect on proliferation and apoptosis-inducing effect of DHA combined with DDP in HNE1/DDP cells (P<0.01).

Conclusion

DHA enhances the growth-inhibitory and apoptosis-inducing effect of DDP on HNE1/DDP cells possibly by promoting accumulation of intracellular ROS.

Keywords: nasopharyngeal carcinoma, dihydroartemisinin, cisplatin, reactive oxygen species, proliferation, apoptosis

鼻咽癌起源于鼻咽上皮,常伴有局部侵袭和早期远处转移[1],在东南亚和中国南部地区发病率较高[2, 3]。目前放疗联合顺铂(DDP)化疗仍然是鼻咽癌的主要治疗方法[4]。尽管放化疗联合治疗获得了令人满意的5年生存率(85%~90%)[5],但仍有8%~10%的患者复发并发生肿瘤转移[6]。对于复发性鼻咽癌患者,目前的标准治疗方法是使用铂类药物进行多药化疗。然而,DDP作为鼻咽癌的常用化疗药物,具有较强的肝、肾、神经和心脏毒性[7],部分发生转移的患者通常会产生对DDP的耐药[8]。因此,迫切需要寻找高效低毒的新型治疗方法。

近年研究表明,天然化合物作为潜在的抗癌药物或增敏剂受到了广泛关注[9]。青蒿素是从黄花蒿叶中提取的倍半萜内酯,其活性衍生物包括双氢青蒿素(DHA)、青蒿琥酯和蒿甲醚[10]。除了抗疟疾作用,DHA表现出明显的肿瘤细胞选择性,对正常细胞的毒性极低[11]。DHA通过调节活性氧(ROS)生成、诱导癌细胞凋亡和细胞周期阻滞的方式,发挥抑制癌细胞增殖、生长、转移和血管形成的作用[12-14]。然而,DHA能否在DDP耐药的鼻咽癌细胞株 HNE1/DDP中促进ROS产生并诱导细胞凋亡还缺乏相关研究。此外,DHA还可以作为增敏剂与其他化疗药物联合使用,以提高化疗疗效[15]。有研究表明,DHA不仅能够通过激活ROS介导的多种信号通路增强DDP诱导的非小细胞肺癌细胞死亡[16],还能增强DDP对神经母细胞瘤细胞的生长抑制作用[17],但DHA增强DDP在HNE1/DDP细胞中的抗肿瘤作用尚未见报道。将DHA与传统化疗药物联合使用可能成为一种新的治疗策略。

本研究观察DHA联合DDP对人鼻咽癌HNE1/ DDP细胞增殖、凋亡的影响,探讨其抗肿瘤的作用以及使HNE1/ DDP细胞恢复凋亡敏感性的分子机制,以期为鼻咽癌的临床治疗提供参考依据。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 试剂与仪器

DHA(纯度98.0%)、DDP(纯度99.84%)(MCE)。RPMI 1640基础培养基(普诺赛),1%青霉素-链霉素(Servicebio),胎牛血清(FBS)、胰酶细胞消化液(Biosharp),CCK-8试剂盒(APE×BIO),Annexin V-FITC/PI双染细胞凋亡检测试剂盒(贝博生物),N-乙酰半胱氨酸(NAC,纯度99.0%)、BeyoClick™ EdU-594细胞增殖检测试剂盒、ROS检测试剂盒(碧云天),Cleaved Caspase-9(Asp330)、Cleaved Caspase-3(Asp175)抗体(Cell Signaling Technology),PARP抗体(Abmart),GAPDH抗体(Proteintech),Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L)-HRP抗体(Bioworld)。

BioTek酶标仪(Synergy HT),Obsever Z1高端全电动倒置荧光显微镜(ZEISS),CytoFLEX流式细胞分析仪(BACKMAN COULTER),Mini-Prote电泳仪及凝胶成像分析系统(Bio-Rad)。

1.2. 方法

1.2.1. 细胞培养

DDP耐药的鼻咽癌细胞株 HNE1/DDP 及其亲本细胞株HNE1均购自中南大学湘雅医学院。细胞培养于含有10% FBS,1%青霉素-链霉素的RPMI 1640完全培养基中,在培养基中加入DDP(1 μg/mL)维持细胞的耐药性,置于37 ℃、5% CO2 的培养箱中常规传代培养。

1.2.2. CCK-8实验检测细胞活力

取对数生长期的HNE1和HNE1/DDP 细胞,按照每孔5×103个细胞的密度接种于96孔培养板中。待细胞密度达到70%~80%时,分别添加含有DHA(终浓度为0、5、10、20、40、80、160 μmol/L)、DDP(终浓度为0、4、8、16、32、64、128 μmol/L)及DHA联合DDP(DDP终浓度为0、4、8、16、32、64、128 μmol/L,DHA终浓度为5 μmol/L)的新鲜培养基,每组设置6个复孔,继续培养24、48 h后,每孔加入10 μL CCK-8工作液,置于培养箱中孵育0.5~1 h。使用酶标仪在450 nm波长处对各个孔的吸光度(A)进行测量,计算细胞存活率。细胞存活率(%)=(A 实验组-A 空白组)/(A 对照组-A 空白组)×100。计算药物半数抑制浓度(IC50)和耐药指数(RI)。采用Compusyn软件计算DHA与DDP的联合指数(CI)。

1.2.3. 集落克隆形成实验检测细胞克隆形成能力

取对数生长期的HNE1/DDP细胞,按照每孔3×103个细胞的密度接种于6孔板中,待细胞贴壁生长后,替换含有DHA(0.5 μmol/L)、DDP(3 μmol/L)以及DHA(0.5 μmol/L)联合DDP(3 μmol/L)的培养基后置于培养箱继续培养。每3 d换液并观察细胞状态,待出现肉眼可见克隆时终止培养。弃旧培养基,用PBS洗涤细胞2次,然后加入4%多聚甲醛室温固定15 min。固定完成后,加入0.5%结晶紫溶液染色15 min,最后用PBS将残余结晶紫溶液洗干净,室温晾干,拍照并使用ImageJ软件计数。

1.2.4. EdU实验检测细胞增殖能力

取对数生长期的HNE1/DDP细胞接种于共聚焦培养皿中,待细胞贴壁生长后使用DHA(5 μmol/L)、DDP(30 μmol/L)以及DHA(5 μmol/L)联合DDP(30 μmol/L)处理24 h,采用BeyoClick™ EdU-594细胞增殖检测试剂盒,将37 ℃预热的EdU工作液(10 μmol/L)加入到培养皿中继续孵育2 h。EdU标记完成后,对培养细胞进行固定、洗涤和通透。去除通透液,洗涤细胞1~2次后加入Click反应液,在室温下避光孵育30 min。使用DAPI进行细胞核染色,室温避光孵育5~10 min,染色情况用倒置荧光显微镜观察并拍照。细胞增殖能力采用EdU阳性染色细胞(红色)占总细胞(蓝色)的百分率表示。

1.2.5. Annexin Ⅴ-FITC/PI 双染检测细胞凋亡

取对数生长期的HNE1/DDP细胞,细胞以2×105/孔的密度接种于6孔板中,待细胞密度达到70%~80%时,在含或不含NAC(5 mmol/L)的情况下加入含有DHA或/和DDP的培养基,培养24 h后,1000 r/min离心5 min,弃上清收集细胞,用预冷的PBS洗涤细胞2次。向细胞中加入400 μL 1×Annexin V结合液重悬细胞,然后加入3 μL Annexin V-FITC染色液,轻柔混匀后,室温避光孵育15 min,加入5 μL PI染色液后混匀,避光孵育5 min,最后用过滤网过滤转至流式管,并用流式细胞仪进行上机检测。

1.2.6. DCFH-DA荧光探针检测细胞内ROS水平

将HNE1/DDP细胞接种于6孔板,调整细胞密度为2×105/孔。培养过夜后,将DHA或/和DDP加入细胞中孵育6 h。弃去细胞培养液,用PBS清洗2次后加入含10 μmol/L DCFH-DA的无血清细胞培养液,37 ℃细胞培养箱内孵育30 min。然后使用无血清细胞培养液洗3次,再用胰酶消化细胞并收集至离心管中,1500 r/min离心5 min,用PBS洗涤2次,最后加入400 μL PBS重悬细胞后使用流式细胞仪于488 nm激发波长处检测DCF的荧光强度。

1.2.7. Western blotting检测凋亡相关蛋白表达

将HNE1/DDP细胞以2.5×105/孔接种于6孔板,待细胞密度达到70%~80%时,在含或不含NAC(5 mmol/L)的情况下加入DHA或/和DDP处理细胞24 h。收集细胞,冰上裂解30 min,每10 min取出涡旋1次,使细胞充分裂解。4 ℃、12 000 r/min离心15 min,提取细胞总蛋白,BCA试剂盒测定各组蛋白浓度,蛋白样品中加入Loading buffer后置于金属浴中100 ℃煮沸5 min,取30 μg蛋白进行SDS-PAGE。10% SDS-PAGE电泳(80 V,30 min;120 V,60 min);转膜(300 mA,1~2 h)至PVDF膜;使用5%(w/v)的脱脂奶粉室温封闭4 h;一抗(1∶1000)4 ℃孵育过夜后回收抗体;TBST洗涤3次,10 min/次;二抗(1∶20 000)室温孵育1.5 h;TBST洗涤3次,10 min/次;最后用ECL试剂盒进行显影,使用凝胶成像系统采集图像,并通过ImageJ分析蛋白表达量。

1.3. 统计学分析

使用Graphpad Prism 8.0软件进行数据统计分析和绘图。计量资料以均数±标准差表示,多组间差异的比较采用多因素方差分析及q检验。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。所有实验均重复3次。

2. 结果

2.1. DDP耐药细胞株HNE1/DDP耐药性的验证

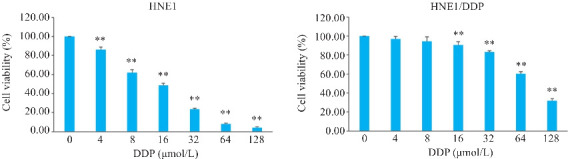

CCK-8结果显示,DDP作用24 h后,随着药物浓度增加,细胞活力逐渐下降(P<0.01),通过曲线拟合得到DDP对亲本株HNE1与耐药株HNE1/DDP细胞的IC50 值分别为13.52±0.97 μmol/L与81.51±2.74 μmol/L,RI为6.03(图1)。

图1.

DDP对HNE1和HNE1/DDP细胞活力的影响

Fig.1 Effect of dihydroartemisinin (DDP) on viability of HNE1 and HNE1/DDP cells. **P<0.01 vs 0 μmol/L.

2.2. DHA或/和DDP抑制HNE1/DDP细胞活力和增殖

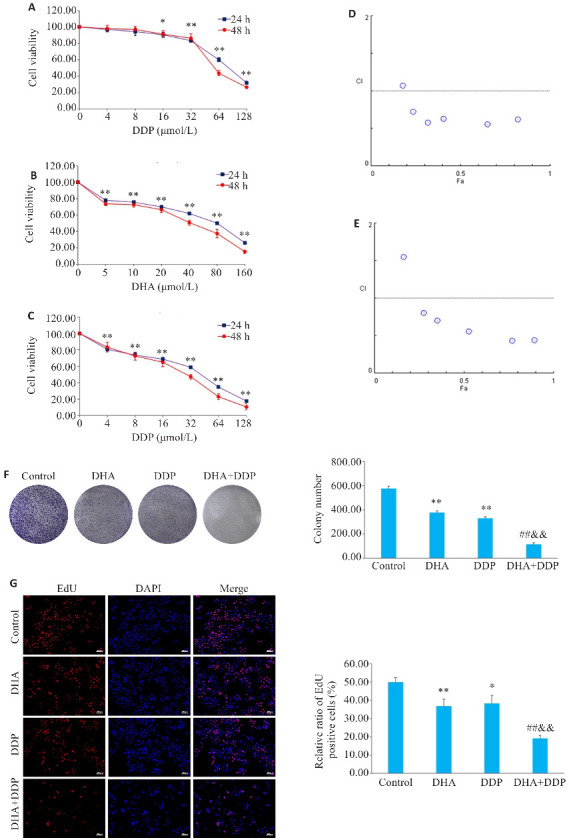

CCK-8结果表明,不同浓度的DHA和DDP处理24、48 h均能明显抑制HNE1/DDP细胞的活力(P<0.05,图2A、B),作用24 h的IC50分别为60.20±3.40 μmol/L、81.51±2.74 μmol/L,作用48 h的IC50分别为35.58±5.58 μmol/L、65.19±4.21 μmol/L。DHA联合不同浓度DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的抑制作用随着DDP浓度的升高而增强(P<0.01,图2C),作用24、48 h的IC50分别为33.27±2.34 μmol/L、23.88±1.11 μmol/L。DHA(5 μmol/L)联合DDP(8、16、32、64、128 μmol/L)的CI值均小于1(图2D、E),因此选取5 μmol/L DHA和30 μmol/L DDP进行后续实验。集落克隆实验结果显示,与对照组相比,DHA组和DDP组均能明显抑制HNE1/DDP细胞集落形成,且DHA联合DDP组的抑制能力更强(P<0.01,图2F)。EdU实验结果表明,DHA组、DDP组、DHA联合DDP组EdU阳性染色细胞在总细胞中的占比明显低于对照组,且DHA联合DDP组细胞EdU阳性细胞率降低(P<0.01,图2G)。

图2.

DHA或/和DDP抑制HNE1/DDP细胞活力和增殖

Fig.2 Inhibitory effects of DHA, DDP, and their combination on viability and proliferation of HNE1/DDP cells. A, B: CCK-8 assay for detecting viability of HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA and DDP for 24 and 48 h. C: CCK-8 assay for detecting viability of HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA (5 μmol/L) combined with DDP (0, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 μmol/L) for 24 and 48 h. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs 0 μmol/L. D, E: Combination index (CI) of combination treatment with DHA and DDP for 24, 48 h. F: Colony formation ability of cells treated with DHA or/and DDP for 24 h. G: EdU test for detecting proliferation of HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA or/and DDP for 24 h (Original magnification: ×10). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs Control group; ## P<0.01 vs DHA group; && P<0.01 vs DDP group.

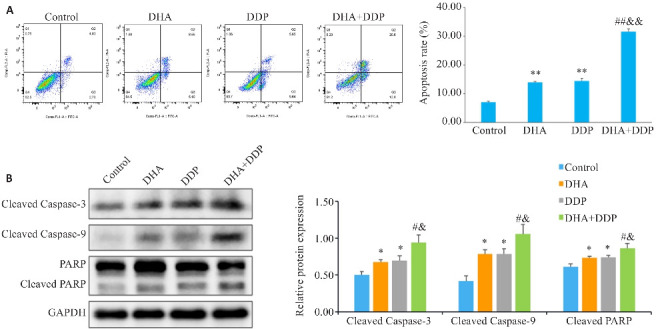

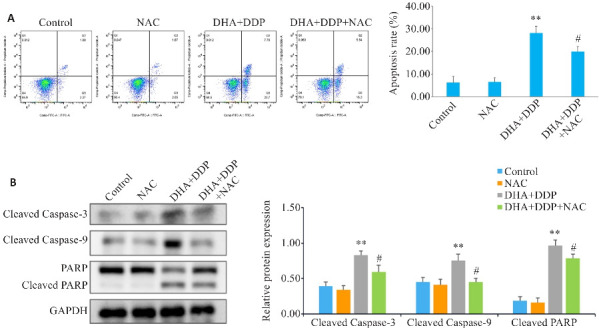

2.3. DHA联合DDP诱导HNE1/DDP细胞凋亡

采用Annexin-V FITC/PI双染检测细胞凋亡,结果显示,与对照组相比,各加药处理组细胞凋亡比例均明显增加,且DHA联合DDP时细胞凋亡率增加更显著(P<0.01,图3A)。Western blotting结果表明,与DHA和DDP组相比,DHA联合DDP组细胞Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-9、Cleaved Caspase-3蛋白表达水平升高(P<0.05,图3B)。

图3.

DHA联合DDP诱导HNE1/DDP细胞凋亡

Fig.3 DHA combined with DDP more potently induces apoptosis in HNE1/DDP cells. A: Apoptosis of HNE1/DDP cells treated with DHA or/and DDP for 24 h detected by flow cytometry. B: Protein levels of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-9, and cleaved caspase-3 in HNE1/DDP cells detected by Western blotting. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs Control group; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs DHA group; & P<0.05, && P<0.01 vs DDP group.

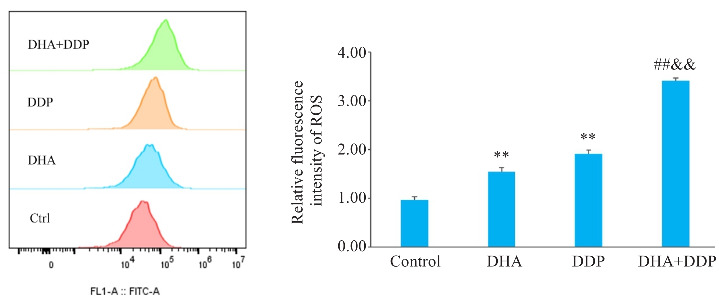

2.4. DHA联合DDP促进HNE1/DDP细胞内ROS的产生

通过DCFH-DA荧光探针检测细胞内ROS水平,结果表明DHA或/和DDP可明显提高HNE1/DDP细胞的ROS水平,且DHA联合DDP时细胞内ROS水平增强(P<0.01,图4)。

图4.

DHA联合DDP促进HNE1/DDP细胞内ROS的产生

Fig.4 DHA combined with DDP enhances ROS production in HNE1/DDP cells. **P<0.01 vs Control group; ## P<0.01 vs DHA group; && P<0.01 vs DDP group.

2.5. DHA联合DDP抑制HNE1/DDP细胞增殖作用依赖于ROS的积累

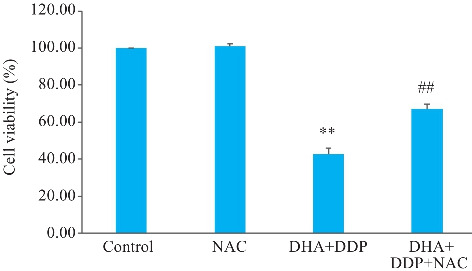

CCK-8结果表明,NAC预处理后,DHA联合DDP组细胞活力的抑制作用被明显逆转(P<0.01,图5)。

图5.

DHA联合DDP抑制HNE1/DDP细胞增殖作用依赖于ROS的积累

Fig.5 DHA combined with DDP more strongly inhibits proliferation of HNE1/DDP cells by promoting ROS accumulation. **P<0.01 vs Control group; ## P<0.01 vs DHA+DDP group.

2.6. ROS参与DHA联合DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的促凋亡作用

流式细胞术结果显示,与DHA联合DDP组相比,NAC预处理后可显著减少ROS诱导的细胞凋亡;Western blotting结果表明,与DHA联合DDP组相比,NAC预处理后凋亡相关蛋白Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-9、Cleaved Caspase-3的表达水平下调(P<0.05,图6)。

图6.

抑制ROS生成对HNE1/DDP细胞凋亡和凋亡相关蛋白表达水平的影响

Fig.6 Effects of inhibiting ROS production on apoptosis and expression of apoptosis-related proteins in HNE1/DDP cells following combined treatment with DHA and DDP for 24 h. A: Apoptosis of HNE1/DDP cells treated with NAC (5 mmol/L) followed by combined treatment with DHA and DDP for 24 h was detected by flow cytometry. B: Protein levels of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-9, and cleaved caspase-3 in HNE1/DDP cells detected by Western blotting. **P<0.01 vs Control group; # P<0.05 vs DHA+DDP group.

3. 讨论

鼻咽癌是华南和东南亚地区最常见的头颈部肿瘤之一[18],目前以DDP为基础的同步放化疗是治疗局部晚期鼻咽癌的标准方法。尽管放疗和化疗的联合疗法取得了令人满意的生存率,然而化疗耐药仍然是鼻咽癌复发患者有效治疗的主要临床障碍。DDP的耐药机制主要涉及DNA损伤修复、细胞凋亡抑制和药物代谢改变等,这些耐药机制对肿瘤患者的治疗及预后有一定影响[19-21]。DHA作为青蒿素的一种衍生物,被认为是一种具有抗疟、抗炎、抗氧化和免疫调节等多重生物活性的天然药物[22],并在近年来被报道为一种有潜力的抗癌药物。多项研究证实,DHA能够通过多种机制发挥抗癌作用,如抑制细胞增殖[23, 24]、诱导细胞凋亡[25, 26]、抑制肿瘤转移和血管生成[27-30]以及诱导细胞自噬和内质网应激[31]等。此外,DHA在增强肿瘤细胞对化疗药物敏感性方面也具有巨大的潜力。研究表明,DHA可通过调控STAT3/DDA1信号通路抑制DDP耐药乳腺癌细胞增殖和诱导凋亡[10],也可通过抑制mTOR使DDP对耐DDP卵巢癌细胞敏感[32]。DHA联合卡培他滨能够通过GSK-3β/TCF7/ MMP9途径抑制结直肠癌的发展,并产生协同作用[33]。然而,DHA是否能够增强DDP耐药鼻咽癌细胞HNE1/DDP的敏感性,其潜在机制有待阐明。本研究发现,与HNE1细胞相比,HNE1/DDP细胞对单独DDP治疗具有耐药性,DHA联合DDP可以显著抑制HNE1/DDP细胞增殖,促进细胞凋亡,两药联合应用效果优于单独使用DHA或DDP,对细胞生长具有协同抑制作用,表明DHA可以增强HNE1/DDP细胞对DDP的敏感性。

细胞凋亡是细胞程序性死亡的一种形式,是肿瘤进展的关键屏障,诱导细胞凋亡被认为是许多抗肿瘤药物开发的重要机制[34]。Caspase9是细胞凋亡途径的初始激活蛋白酶,被称为“启动蛋白酶”;Caspase3则是细胞凋亡途径中的“执行蛋白酶”[35]。当细胞接收到内外信号(如DNA损伤、细胞因子等)诱导细胞凋亡时,Caspase-9活化,从而导致Caspase-3活化,导致细胞死亡[35, 36],因此Caspase-3的激活是细胞凋亡的重要标志。PARP作为Caspase-3的切割底物,在细胞凋亡中起着重要的作用,PARP的剪切也被用作细胞凋亡和Caspase-3激活的指标[37]。有研究显示,马钱子碱A诱导线粒体功能障碍,导致线粒体膜电位降低,Cyt C释放,Caspase-9和Caspase-3活化,最终诱导细胞凋亡[38]。蓝萼甲素通过触发细胞内ROS生成、诱导Caspase-9和Caspase-3裂解等途径诱导线粒体凋亡[39]。本研究发现,与单独处理组相比,DHA联合DDP能够显著上调促凋亡蛋白Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-3、Cleaved Caspase-9的表达,进一步表明DHA可通过Caspase依赖性线粒体凋亡途径的激活协同诱导DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的促凋亡作用,从而发挥抗肿瘤作用。

ROS被认为是癌症细胞死亡和增殖过程中的关键调节因子[40]。有研究表明,DHA能够通过调节舌鳞癌细胞内ROS的生成诱导内质网应激介导的细胞凋亡[41],也能通过靶向PTGS1-ROS介导的多种信号通路增强DDP的抗非小细胞肺癌作用[16]。异戊基螺旋霉素I通过升高ROS水平抑制非小细胞肺癌细胞增殖和诱导细胞凋亡,ROS抑制剂NAC可明显逆转这一作用[42]。这些发现表明,过度积累的ROS参与肿瘤生长抑制,可通过多种途径引起细胞凋亡,但尚未有文献报道DHA是否能在鼻咽癌中通过促进ROS的产生诱导细胞凋亡,并增强DDP的抗肿瘤作用。因此,本研究选择DCFH-DA作为探针检测细胞内ROS水平,进一步探讨ROS 在DHA联合DDP抑制HNE1/DDP细胞增殖和诱导细胞凋亡中的作用。结果表明,DHA与DDP联合应用能够显著增加HNE1/DDP细胞内ROS的生成。为了确定ROS是否与DHA诱导的细胞凋亡有关,本研究使用NAC进行预处理,发现DHA联合DDP显著抑制了HNE1/DDP细胞的增殖,而NAC预处理部分逆转了这一现象。此外,NAC预处理显著降低了DHA联合DDP促HNE1/DDP细胞凋亡的作用,包括下调Cleaved PARP、Cleaved Caspase-3、Cleaved Caspase-9的表达,提示DHA联合DDP对HNE1/DDP细胞的增殖抑制和凋亡诱导作用是由ROS积累介导的。DHA和DDP联合治疗通过促进ROS的产生诱导HNE1/DDP细胞凋亡,比单一药物治疗更大程度上增强了DDP的抗肿瘤活性。

综上所述,DHA能够增强HNE1/DDP细胞对DDP的敏感性,其抑制细胞增殖和诱导凋亡作用可能与细胞内ROS产生有关。本研究结果提示DHA与DDP联合治疗鼻咽癌可能是一种很有前途的临床治疗方法,将为DDP耐药的鼻咽癌临床治疗提供新的策略。然而,本研究只在细胞水平上进行了实验,因此仍需要进一步在动物水平和信号通路上进行验证和探索。

基金资助

国家自然科学基金(81603155);安徽省高校自然科学研究重点项目(2022AH051534,KJ2021A0736);蚌埠医学院自然科学重点项目(2021byzd018);安徽省大学生创新创业训练项目(S202310367074)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81603155).

参考文献

- 1. Wang SM, Claret FX, Wu WY. MicroRNAs as therapeutic targets in nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Front Oncol, 2019, 9: 756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10192): 64-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pfister DG, Spencer S, Adelstein D, et al. Head and neck cancers, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2020, 18(7): 873-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blanchard P, Lee A, Marguet S, et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the MAC-NPC meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(6): 645-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perri F, Bosso D, Buonerba C, et al. Locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current and emerging treatment strategies[J]. World J Clin Oncol, 2011, 2(12): 377-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perri F, Della Vittoria Scarpati G, Caponigro F, et al. Management of recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current perspectives[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2019, 12: 1583-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cui ZQ, Pu T, Zhang YJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA LINC00346 contributes to cisplatin resistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by repressing miR-342-5p[J]. Open Biol, 2020, 10(5): 190286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9. Dutta S, Mahalanobish S, Saha S, et al. Natural products: an upcoming therapeutic approach to cancer[J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2019, 128: 240-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang J, Li Y, Wang JG, et al. Dihydroartemisinin affects STAT3/DDA1 signaling pathway and reverses breast cancer resistance to cisplatin[J]. Am J Chin Med, 2023, 51(2): 445-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malami I, Bunza AM, Alhassan AM, et al. Dihydroartemisinin as a potential drug candidate for cancer therapy: a structural-based virtual screening for multitarget profiling[J]. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2022, 40(3): 1347-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu YM, Gao SJ, Zhu J, et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer via inhibition of the hedgehog signaling pathway[J]. Cancer Med, 2018, 7(11): 5704-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu H, Wang ZD, Tan CL, et al. Dihydroartemisinin/miR-29b combination therapy increases the pro-apoptotic effect of dihydroartemisinin on cholangiocarcinoma cell lines by regulating Mcl-1 expression[J]. Adv Clin Exp Med, 2020, 29(8): 911-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu YY, Chen TS, Wang XP, et al. Single-cell analysis of dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-mediated caspase-8 activation and mitochondrial pathway in ASTC-a-1 cells using fluorescence imaging techniques[J]. J Biomed Opt, 2010, 15(4): 046028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li PC, Yang S, Dou MM, et al. Synergic effects of artemisinin and resveratrol in cancer cells[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2014, 140(12): 2065-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ni LL, Zhu XP, Zhao Q, et al. Dihydroartemisinin, a potential PTGS1 inhibitor, potentiated cisplatin-induced cell death in non-small cell lung cancer through activating ROS-mediated multiple signaling pathways[J]. Neoplasia, 2024, 51: 100991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. 刘艳艳, 安 倩, 海 波, 等. 双氢青蒿素联合顺铂对人神经母细胞瘤细胞增殖及凋亡的影响[J]. 现代肿瘤医学, 2023, 31(22): 4129-35. 36785388 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China[J]. Chin J Cancer, 2011, 30(2): 114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hong Y, Che SM, Hui BN, et al. Combination therapy of lung cancer using layer-by-layer cisplatin prodrug and curcumin co-encapsulated nanomedicine[J]. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2020, 14: 2263-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang ML, Li HR, Li YR, et al. Identification of genes and pathways associated with MDR in MCF-7/MDR breast cancer cells by RNA-seq analysis[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2018, 17(5): 6211-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kadioglu O, Elbadawi M, Fleischer E, et al. Identification of novel anthracycline resistance genes and their inhibitors[J]. Pharmaceuticals, 2021, 14(10): 1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dama S, Niangaly H, Djimde M, et al. A randomized trial of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus artemether-lumefantrine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mali[J]. Malar J, 2018, 17(1): 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slezakova S, Ruda-Kucerova J. Anticancer activity of artemisinin and its derivatives[J]. Anticancer Res, 2017, 37(11): 5995-6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang CZ, Zhang HT, Yun JP, et al. Dihydroartemisinin exhibits antitumor activity toward hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo [J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2012, 83(9): 1278-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qin GQ, Zhao CB, Zhang LL, et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis preferentially via a Bim-mediated intrinsic pathway in hepatocarcinoma cells[J]. Apoptosis, 2015, 20(8): 1072-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Im E, Yeo C, Lee HJ, et al. Dihydroartemisinin induced caspase-dependent apoptosis through inhibiting the specificity protein 1 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep-1 cells[J]. Life Sci, 2018, 192: 286-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong J, Yang WH, Han JQ, et al. Effect of dihydroartemisinin on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in canine mammary tumour cells[J]. Res Vet Sci, 2019, 124: 240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li N, Zhang SY, Luo Q, et al. The effect of dihydroartemisinin on the malignancy and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer cells[J]. Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2019, 20(9): 719-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yao YY, Guo QL, Cao Y, et al. Artemisinin derivatives inactivate cancer-associated fibroblasts through suppressing TGF‑β signaling in breast cancer[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 37(1): 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen HH, Zhou HJ, Fang X. Inhibition of human cancer cell line growth and human umbilical vein endothelial cell angiogenesis by artemisinin derivatives in vitro [J]. Pharmacol Res, 2003, 48(3): 231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu JJ, Chen SM, Zhang XW, et al. The anti-cancer activity of dihydroartemisinin is associated with induction of iron-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress in colorectal carcinoma HCT116 cells[J]. Invest New Drugs, 2011, 29(6): 1276-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng X, Li L, Jiang H, et al. Dihydroartemisinin potentiates the anticancer effect of cisplatin via mTOR inhibition in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: involvement of apoptosis and autophagy[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2014, 444(3): 376-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dai XS, Chen W, Qiao Y, et al. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the development of colorectal cancer by GSK-3β/TCF7/MMP9 pathway and synergies with capecitabine[J]. Cancer Lett, 2024, 582: 216596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li XM, Hou YN, Zhao JT, et al. Combination of chemotherapy and oxidative stress to enhance cancer cell apoptosis[J]. Chem Sci, 2020, 11(12): 3215-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tian YZ, Liu YP, Tian SC, et al. Antitumor activity of ginsenoside Rd in gastric cancer via up-regulation of Caspase-3 and Caspase-9[J]. Pharmazie, 2020, 75(4): 147-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. NavaneethaKrishnan S, Rosales JL, Lee KY. Loss of Cdk5 in breast cancer cells promotes ROS-mediated cell death through dysregulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore[J]. Oncogene, 2018, 37(13): 1788-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olliaro PL, Haynes RK, Meunier B, et al. Possible modes of action of the artemisinin-type compounds[J]. Trends Parasitol, 2001, 17(3): 122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li X, Liu CQ, Zhang X, et al. Bruceine A: Suppressing metastasis via MEK/ERK pathway and invoking mitochondrial apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Biomedecine Pharmacother, 2023, 168: 115784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhu JW, Sun Y, Lu Y, et al. Glaucocalyxin A exerts anticancer effect on osteosarcoma by inhibiting GLI1 nuclear translocation via regulating PI3K/Akt pathway[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9(6): 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perillo B, di Donato M, Pezone A, et al. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon[J]. Exp Mol Med, 2020, 52(2): 192-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou Q, Ye FF, Qiu JX, et al. Dihydroartemisinin induces ER stress-mediated apoptosis in human tongue squamous carcinoma by regulating ROS production[J]. Anticancer Agents Med Chem, 2022, 22(16): 2902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu ZY, Huang ML, Hong Y, et al. Isovalerylspiramycin I suppresses non-small cell lung carcinoma growth through ROS-mediated inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2022, 18(9): 3714-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]