Abstract

Environmental concerns linked to animal-based protein production have intensified interest in sustainable alternatives, with a focus on underutilized plant proteins. Faba beans, primarily used for animal feed, offer a high-quality protein source with promising bioactive compounds for food applications. This study explores the efficacy of ultrasound-assisted extraction under optimal conditions (123 W power, 1:15 g/mL solute/solvent ratio, 41 min sonication, 623 mL total volume) to isolate faba bean protein (U-FBPI). The ultrasound-assisted method achieved a protein extraction yield of 19.75 % and a protein content of 92.87 %, outperforming the control method’s yield of 16.41 % and protein content of 89.88 %. Electrophoretic analysis confirmed no significant changes in the primary structure of U-FBPI compared to the control. However, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy revealed modifications in the secondary structure due to ultrasound treatment. The U-FBPI demonstrated superior water and oil holding capacities compared to the control protein isolate, although its foaming capacity was reduced by ultrasound. Thermal analysis indicated minimal impact on the protein’s thermal properties under the applied ultrasound conditions. This research highlights the potential of ultrasound-assisted extraction for improving the functional properties of faba bean protein isolates, presenting a viable approach for advancing plant-based food production and contributing to sustainable protein consumption.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Faba bean, Protein isolate, Structural properties, Functional properties, Thermal analysis

1. Introduction

Economic growth heightened cultural and social awareness, and an improved standard of living over the past decade has driven consumer preference for nutritious and flavourful foods. This shift has resulted in over $30 billion in revenue for the dietary supplement industry [1]. To meet the rising nutritional demands of the world’s growing population, plant protein has become a crucial part of diets. One of its key benefits is providing sufficient amounts of essential amino acids [2]. Moreover, the unique physicochemical properties of plant proteins affect food processing, storage, and consumption, thereby impacting food quality and sensory attributes. This shift is often referred to as the “protein transition” [3].

Compared to other common protein crops, faba bean seeds (V. fabacaeae) have a higher protein content, approximately 30 % of dry matter, making them an appealing raw material for producing protein-rich foods [4]. Additionally, faba beans are increasingly favoured as a plant-based protein source due to their effective nitrogen-fixing abilities and ease of cultivation [5]. Moreover, faba bean protein offers a quality of amino acid profile and digestibility comparable to animal proteins, distinguishing it from many other plant-based proteins [6], [7], [8]. A whole faba bean contains approximately 27 % protein, 2 % fat, 60 % carbohydrates, and 15 % fibre, along with various vitamins and minerals [9], [10]. Globulins, making up 70–80 % of the storage protein in faba bean seeds, are classified into two types based on their sedimentation coefficient: 7S vicilin-type globulins and 11S legumin-type globulins. Additionally, the albumin fraction in faba beans is notable for its high content of sulphur-containing amino acids compared to other seed proteins [11]. The physicochemical and functional properties of globulin and other protein fractions vary due to differences in their structures. These structural variations lead to differences in attributes such as denaturation temperature, solubility profile, and functional characteristics [12], [13]. Protein-rich products from faba beans are typically classified into two categories: isolates, which contain approximately 90 % protein, and concentrates, which have around 65 % protein [9]. Protein isolates from pulses are generally obtained using various methods, including alkaline solubilization with subsequent precipitation at the isoelectric point, or salt extraction followed by micellization [9], [14]. Traditional extraction methods are often limited by their lower extraction yields and reduced protein purity. Additionally, many commercially available proteins exhibit poor solubility and are prone to significant denaturation, which can adversely affect their structural integrity and functional performance [15].

Ultrasound, a novel non-thermal technology for processing and chemical applications, is classified as a method for process intensification [16]. Enhanced extraction with ultrasound primarily results from the benefits of acoustic cavitation, which is induced by ultrasonic waves traveling through the suspension [17]. Ultrasound enhances extraction by mechanically increasing the contact area between liquid and solid phases, which improves solvent penetration into the sample and accelerates the diffusion of solutes into the solvent [18], [19]. However, optimizing the process for ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) remains limited. Effective UAE can lead to improved extraction yields and modified functional properties of proteins [20]. Successful protein extraction relies on understanding how UAE parameters such as time, power, frequency, solvent-to-sample ratio, and temperature affect the extraction of faba bean proteins. Using response surface methodology to optimize these variables helps in selecting the best conditions to maximize extraction yield and purity.

Although ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) is a promising technique, there is a lack of in-depth studies on optimizing protein extraction from faba bean seeds. This research aims to fill this gap by introducing UAE for faba bean protein isolation. It involves: (i) optimizing UAE parameters using Box-Behnken Design (BD) to enhance extraction efficiency; and (ii) evaluating and comparing the structural, thermal, and functional properties of proteins isolated through this method. The study offers a detailed analysis of the protein physicochemical and thermal characteristics obtained through optimized UAE.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Raw materials and chemicals

Faba bean seeds were purchased from Whole Foods Earth (Kent, United). NaOH, ((≥99.9 % pure), HCI, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (United Kingdom). β-mercaptoethanol was obtained from Thermo Fisher scientific. Rapeseed oil was obtained from a local shop in Sheffield (United Kingdom). All the chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. The seeds were finely powdered using a cyclone mill and kept at −20 °C until needed.

2.2. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of faba bean protein

The optimization process aimed to determine the optimal set of parameters for achieving the highest extraction yield and protein content, thereby identifying the key influencing factors. This was informed by previous research findings [17] and other studies on protein isolation from plant sources, which guided the selection of minimum and maximum values for each factor [21], [22]. Different dispersions of faba bean flour in water (1:5–1:20 w/v) with variable total volumes (500–1000 mL) were agitated at 25 °C for 20 min at 500 rpm before ultrasonic-assisted extraction. PH of the dispersion was then adjusted to pH 11, then subjected to ultrasonic treatment at varying ultrasonic power (50–180 W) and varying sonication duration (10–60 min) using a S24d22D titanium ultrasonic horn with a sonotrode diameter of 22 mm and radiating surface of 3.8 cm2 (Teltow, Germany). Temperature was maintained at 20–25 °C using an ice bath. The resultant mixture was centrifuged for 20 min at 25 °C at 6,000 rpm using a centrifuge (accuSpinTM 400, United Kingdom). After gathering the supernatant, 1 N HCI was used to bring the pH to 4.0 while stirring continuously for 20 min. Protein isolate pellets were then obtained after centrifuging at 6,000 rpm for 20 min at 25 °C. After 48 hrs of lyophilization of the protein pellet, samples were stored at −20 °C for further analysis. Protein content was determined by the Dumas method. Control protein isolate was generated using optimized conditions without ultrasound treatment.

The weight of the protein isolate obtained was divided by the initial weight of the measured faba bean flour to calculate the extraction yield, as given in Equation (1).

| (1) |

The mass of the initial flour and final protein isolate are represented by ms and mi, respectively.

2.3. Box-Behnken analysis experiment

The independent variables in the study were ultrasonic power, sonication time, solid/solvent ratio, and total extraction volume. To maximize extraction yield and protein content from faba bean flour, a response surface-based optimization method was employed using Design Expert software. Each of the four variables was tested at three distinct levels: low (1), medium (0), and high (+1). These variables were explored for their effects on the ultrasonic-assisted alkaline extraction of faba bean protein isolates. Both the extraction yield and protein content of the freeze-dried faba bean protein isolate served as the response variables. The comprehensive results of the optimization process are documented [23]. The coded factors for each variable are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Actual and coded variables were used in the ultrasound-assisted extraction design of the experiment.

| Independent variables | Unit | Levels |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | optimal | High | ||

| Power | W | 50 | 115 | 180 |

| Solute/water ratio | w/v | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Extraction time | min | 10 | 35 | 60 |

| Total volume | ml | 500 | 750 | 1000 |

2.4. Functional properties

2.4.1. Protein oil and water holding capacity (OHC and WHC)

For WHC and OHC, 1.0 g of faba bean protein isolate was dispersed in 40 mL of distilled water and rapeseed oil, respectively. The mixtures were vortexed at maximum speed for one minute, and then allowed to stand at room temperature (20–23 °C) for six hours. After that, samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 20 °C at 3000 x g.

Where is the mass of the tube and protein isolate and absorbed water or oil; is the mass of the tube and protein isolate while is the mass of faba bean protein.

2.5. Foaming properties

To study the foam stability and capacity, the method described by Loushigam et al., [24] was employed. Faba bean protein isolate solutions (1 % weight protein basis, pH 7) were dissolved in distilled water and stirred at room temperature for one hour. 15 mL of the protein mixture were homogenized for three minutes at room temperature using a homogenizer (IKA T18 ultra-turrax basic, United Kingdom). Using a graduated cylinder, the total volumes (mL) were measured before and after whipping. The following formula was used to compare the volume of the foam layer at 15 and 30 min to the initial foam volume of the samples to determine the foaming capacity (FC) and stability (FS):

2.6. Qualitative analysis of proteins using electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Electrophoresis was carried out on SDS-PAGE in a reducing solution of β-mercaptoethanol [25]. 50 mg protein powders were dissolved in 10 mL of PBS buffer (0.01 M, pH 7) and stirred at 200 rpm for 2 hr at room temperature. 10 μL protein solution was dissolved, and vortexed with 10 μL loading buffer (reducing solution containing 10 % 2-mercaptoethanol). The samples were heated for 4 min at 95 ⁰C, followed by cooling, and centrifugation at 13300 x g for 3 min. An aliquot was injected into the pocket of the Bio-Rad 4 % acrylamide stacking gel. Separation at a current of 25 mA was performed for one hour at a voltage of 200 V for 35 mins. SDS-PAGE pre-stained ladder ranging from 260–8 kDa was used as standard marker. The gel was rinsed with water and stained sequentially with commasie blue and imperial stain. Destained gel was scanned using Gel analysis instrument (Nugenius, United Kingdom).

2.7. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis

For the FTIR investigation, an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR spectrophotometer (Spectrum 100 FT-IR, PerkinElmer, USA) was used. A total of 16 scans were conducted within the wavenumber range 4000 – 650 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.8. Thermal properties

2.8.1. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

A thermogravimetric analyzer type Q50 was used to study the thermal properties of the protein isolates. About 2 mg of the material was heated from 30 to 900 °C under ambient nitrogen (200 mL/min).

2.8.2. Differential scanning calorimetry

The thermal profile of the protein isolates was measured using differential scanning calorimetry. Aluminum pans with a hermetically sealed interior held 10–20 mg of protein isolates. In an inert nitrogen environment, samples were heated at a rate of 10 °Cmin−1 using a heat ramp from 25 to 180 °C.

2.9. X-ray diffraction (XRD)

For XRD studies, an X'pert X-ray diffractometer was employed. The anti-scatter slits were set at 0.04 mm along with 1 mm diverging and receiving slits. The diffractogram was measured between 5 and 70° (2θ) with a step size of 0.05 ⁰.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by Origin 2019. All the values were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimal extraction conditions by RSM

The experimental results indicated that the conditions of 123 W power, a solute to solvent ratio of 0.06 (1:15 g/mL), a sonication time of 41 min, and a total volume of 623 mL were predicted to yield a maximum extraction yield of 18.71 ± 1 % and a protein content of 89.76 ± 1 % after optimization. Upon experimental validation, these conditions achieved an extraction yield of 19.75 ± 0.87 % and a protein content of 92.87 ± 0.53 %. Therefore, the quadratic model used in this study proved effective in determining the optimal conditions for producing protein isolate from faba bean flour. In contrast, a control sample processed under similar conditions but without ultrasound treatment yielded an extraction rate of 16.41 ± 0.02 % and a protein content of 89.88 ± 0.40 % [23]. Thus, the ultrasound treatment enhanced both the extraction efficiency and the protein content of the extracts, consistent with findings reported in the literature for other plant materials [26]. The effectiveness of ultrasonication could be linked to cell disruption during the extraction process. Plant proteins are often covalently bound to other macromolecules like carbohydrates, cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. These bonds hinder protein release from plant matrices and reduce their availability in the extraction medium, necessitating an extraction method capable of effectively disrupting the cell matrix [27]. In alkaline medium, ultrasonic waves produce cavitation, turbulence, and shear forces near the plant matrix, disrupting plant tissue and enhancing protein extraction [28]. This is attributed to cavitation and the mechanical vibrations of ultrasound waves, which break cell walls and molecular bonds, increasing the contact surface area between the solid and liquid matrices [29].

3.2. Functional properties

3.2.1. Foaming capacity (FC) and foaming stability (FS)

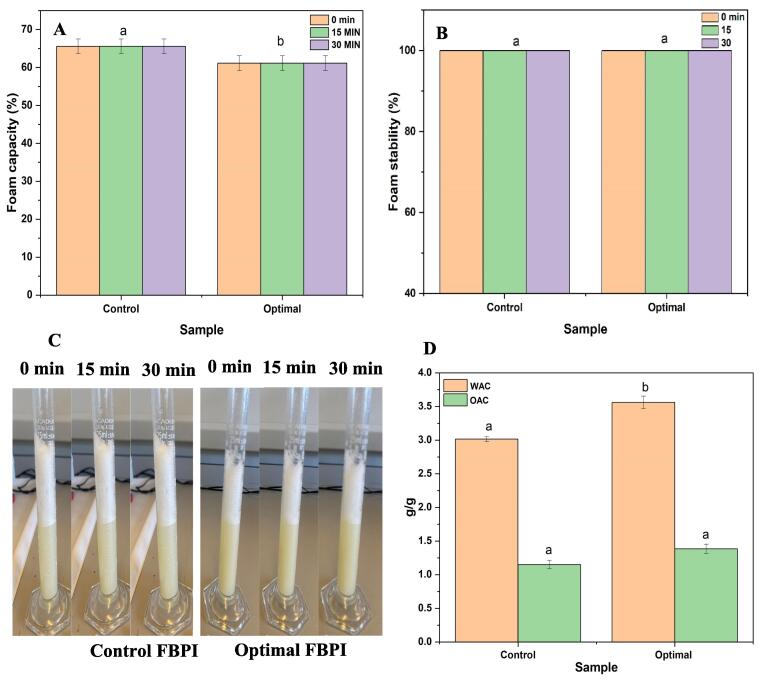

The foaming capacity and foaming stability of control and ultrasound FBPI are presented in Fig. 1A& B. While foaming stability (FS) refers to a protein’s ability to produce stable foams by constructing a continuous intermolecular polymer network that encloses air cells, foaming capacity (FC) describes a protein’s ability to unfold quickly forming a cohesive layer that surrounds gas bubbles [30]. In theory, the main phases for protein to form foams are transportation, penetration, and reorganization of protein molecules at the air/water interface. The Foaming capacity of the control FBPI was 65.56 % which was higher than the optimal U-FBPI (61.11 %). Several studies have reported an improvement in foaming capacity after ultrasound treatment [31], [32] which are contrary to those observed in these studies. However, a study by Gao et al. [33] on soluble pea proteins showed that ultrasound treatment can reduce foaming capacity through major modifications in protein structure and network which may affect FC. Apart from variations in the foaming method used, final power input per unit volume and other ultrasonic parameters may influence foaming capacity. In terms of foam stability, both samples showed 100 % stability as shown in Fig. 1B & C after 10, 15, and 30 min. This indicates that both protein isolates had sufficient mechanical strength, and flexibility to keep the foams intact. Chittapalo et al. [34] found that the alkaline extraction method resulted in a higher foaming capacity for rice bran protein compared to the ultrasonic extraction method. This reduction may be due to ultrasonic treatment altering the protein structure and changing the ratio of hydrophilic to hydrophobic groups. This increases surface tension and decreases surface activity, affecting the protein’s adsorption capacity and migration speed at the air–water interface [35].

Fig. 1.

Functional properties of optimal ultrasound-assisted and control extracted faba bean protein isolate (A) foaming capacity (B) foaming stability (C) representative photographs of the foam prepared from (1 % wt., protein basis, pH 7) at 0, 15 and, 30 (D) water and oil absorption capacity.

3.3. Water holding capacity and oil holding capacity (WHC)

Information on the water and oil absorption capacity of proteins is useful in predicting protein behaviour in food systems such as meat analogs, yogurt analogs, and bakery products. This is necessary to prevent liquid loss (water or oil) during processing and avoiding undesirable textural and sensorial properties [36], [37]. The water and oil absorption capacity of the optimal ultrasound-assisted faba bean protein isolate and the control is shown in Fig. 1D. The water holding capacity was significantly higher in the optimal ultrasound protein isolate (3.56 g/g) compared to the control sample (3.01 g/g). The WHC of proteins is influenced by numerous factors such as conformational structure, particle size, surface hydrophobicity as well as the amino acid sequence [38]. Similarly, a higher OHC was observed in the optimal ultrasound protein isolate (1.38 g/g) than in the control sample (1.15 g/g). Lipid-protein interactions are attributed to the binding of non-polar amino acid side chains to aliphatic chains of lipids, thus proteins with high surface hydrophobicity tend to have a high OHC [39].

The relatively high fluid binding properties of the faba bean protein after ultrasound treatment may have been due to the formation of a more porous structure [41]. An increase in OBC values may also be because ultrasonic cavitation caused partial denaturation of the faba bean’s proteins, which exposed hydrophobic groups at the surfaces of the protein powders, thereby leading to greater oil retention [40]. Proteins with higher hydrophobicity typically exhibit better fat absorption, as the non-polar amino acid chains interact easily with lipid aliphatic chains [41]. The application of protein in specific foods often depends on the WHC to OHC ratio. Non-protein substances such as starch and lipids can interact with proteins, altering the WHC and OHC, highlighting the importance of efficient protein isolation from the plant matrix.

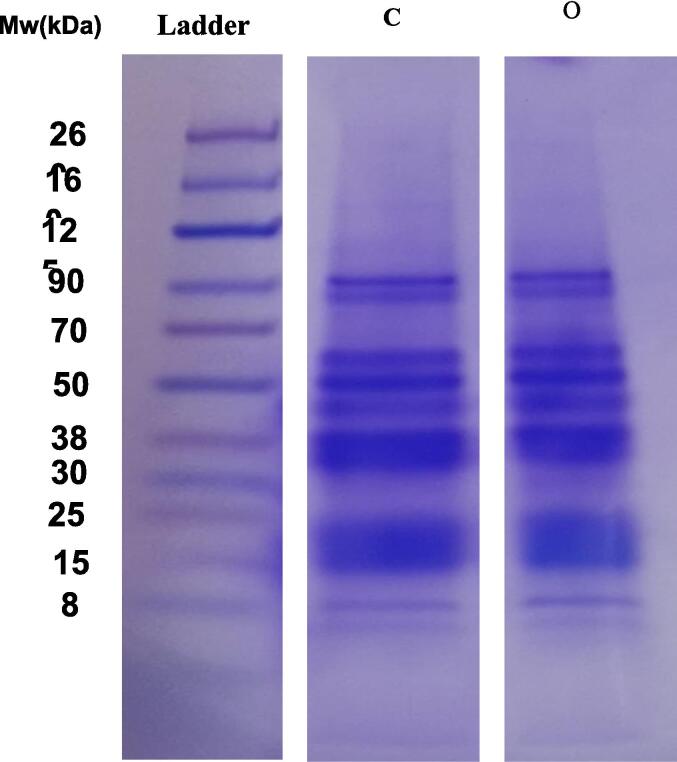

3.4. SDS-PAGE analysis

SDS electrophoresis was performed to analyze the protein profiles of the two protein isolates: optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction and conventional faba bean protein isolates. Fig. 2 shows the protein profile of the two isolation conditions under reducing conditions. Several bands were observed from 8 to 90 kDa. An additional smearing band was observed from 260 to 90 kDa. Similar subunit bands were observed between optimized and controlled protein isolates. These results are in agreement with different studies which observed no changes on primary structure after ultrasound application in soy protein isolate, moringa protein and pea protein isolate [40], [41]. Two strong protein bands detected ∼90 kDa could correspond to seed lipoxygenase [42]. A strong protein band was detected at ∼50–55 kDa in both samples. This band could be the globulin convicilin [42]. The trimeric protein is one of the primary storage proteins in Vicia faba L. The dense protein bands detected at from ∼38 kDa may represent vicilin subunits while protein subunits at 15 kDa and below may be associated with albumins [42].

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE protein profile of Faba bean isolates under reducing conditions. C represents conventional protein extraction while O represent ultrasound-assisted extraction.

The results indicate that ultrasound treatment did not alter the primary structure of macromolecules, as the applied sonication conditions were insufficient to disrupt this structure. Polypeptides in the 20–29 kDa and 29–44 kDa ranges are likely related to the acidic and basic subunits of glycinin [43], [44]. Subunits around 50 kDa and 70 kDa are probably vicilin and convicilin, respectively [43]. Singh & Kaur [45] identified polypeptides with molecular weights of 12–120 kDa and 11.5–122 kDa as corresponding to albumin and globulin fractions, respectively. The SDS-PAGE results support the findings from Zou et al. [46] and O’sullivan et al. [47], which demonstrated that ultrasound does not significantly alter the molecular structure of protein isolates.

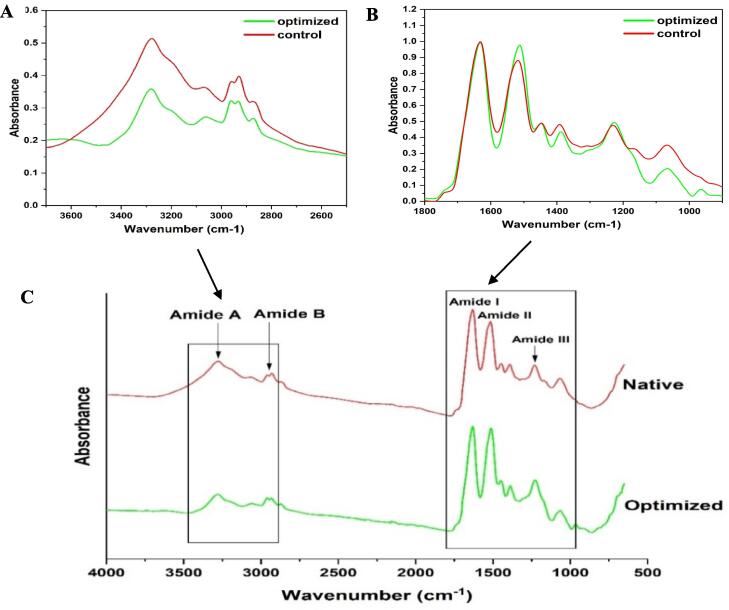

3.5. FTIR

FTIR spectra of optimised protein isolate and conventionally extracted protein were both in accordance with those found from other protein isolates such as pea, quinoa, and album proteins [48], [49] (Fig. 3). Dominant regions attributed to protein functional groups Amide I, Amide II and Amide II (Fig. 3B) were found in both spectra. Additionally, other regions such as Amide A and B (region 3500–2500 cm−1) were also observed in both samples. Bands ranging from 1200–1000 cm−1 mostly ascribed to carbohydrate regions showed major differences between the two samples [50]. Major differences were observed in the spectra in all amide regions especially in amide A and B regions however slight differences in the Amide I, II, and III regions. Optimized ultrasound-extracted proteins showed lower absorbance in amide A and B regions in comparison with the control protein isolate. The lower peak intensity of ultrasound-produced protein isolates could be attributed to protein–protein interaction occurrence via hydrogen bonds in a higher degree. Amide I band which is the most sensitive protein region was also confirmed to result from C=O stretching vibrations and N-H bending vibrations [48], [51]. The amide I band of both optimized and control samples showed similar wavenumber and intensities, however, the Amide II band of optimized protein isolate showed a higher intensity compared to control isolates. Additionally, the carbohydrate region (1200–1000 cm−1), showed lower intensity in ultrasound extracted proteins compared to the control, indicating high protein purity in ultrasound-assisted protein extraction. Modification of the secondary structure after ultrasonic-assisted treatment can be attributed to the breaking of β-sheet secondary bonds resulting in the rearrangement into α-helices and β-turns [35]. Additionally, the reduction in absorption intensity in the Amide A and B regions may be attributed to partial swelling of the protein structure and disruption of hydrogen bonding interactions. This results in the cleavage of β-sheet and β-turn bonds and their reorganization into α-helices, altering the protein structure [35].

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectra of freeze-dried protein isolate from Faba beans flour by optimized ultrasound-assisted and conventional extraction process.

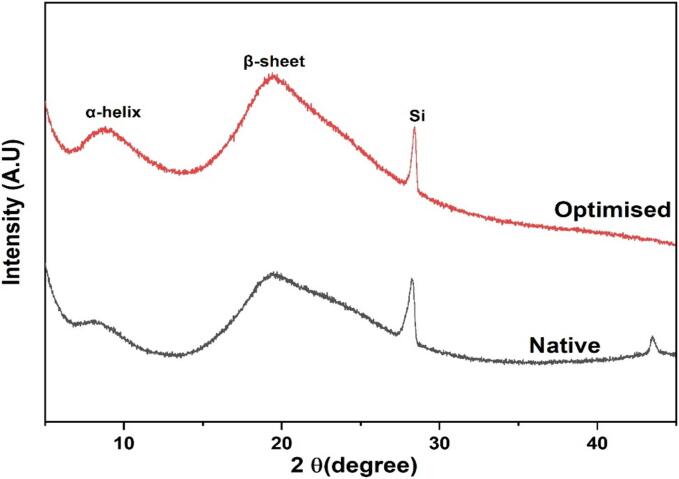

3.6. X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is used to investigate the phase composition and crystal structural properties [52]. XRD patterns of protein obtained from faba bean flour by ultrasound and conventional extraction process were studied to provide further structural information. The diffractogram of ultrasonic-assisted and conventional faba bean isolates is shown in Fig. 4. Slight differences between both samples showed that extraction conditions influenced diffractogram patterns. The first diffraction peak was observed between 5° and 10° (low intensity), which is related to a relatively sharp diffraction peak. The second peak was observed around 20° (high intensity). A very small peak was observed between 40° and 45° for untreated extracted faba bean protein isolate. The crystalline region I and II is attributed to 2θ = 10° and 2θ = 20° respectively. Information on crystalline size can be obtained from diffraction intensity and area. A small crystal size usually shows a low diffraction intensity and vice versa [53]. The results are similar to those of 7S and 11S proteins obtained from soy proteins [54] as well as results obtained from mung bean proteins [55]. Whey protein isolates were also reported to have comparable peaks at 2θ = 8° and 19.5° [56].

Fig. 4.

XRD diffraction pattern of optimised and control Faba bean protein isolate.

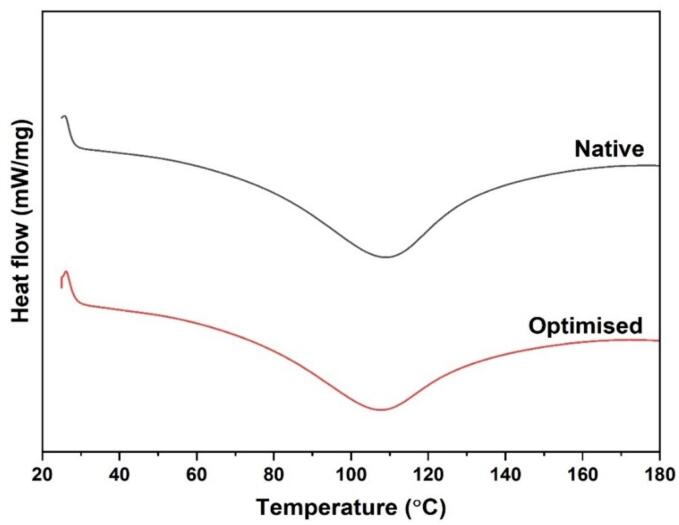

3.7. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The thermal stability of proteins plays a key role in the functionality and hence their applicability in food systems. The thermal properties are useful in different food application as most processes involve some heating steps. DSC can serve as a means of examining protein properties during processing. The Tdenaturation is the temperature of protein degradation and is useful observed as a peak and reflects thermal stability of proteins. DSC thermogram of the optimized and control faba bean protein isolate is shown in Fig. 5. Control FBPI displayed an endothermic peak at 109.5 °C while the peak of ultrasound-assisted optimized FPPI had a similar endothermic peak but slightly lower. Slightly lower denaturation temperature may be due to physical structural modification resulting from ultrasound treatment. Ultrasonicated protein did not denature after extraction, instead, proteins were stable. This indicates that native and optimized ultrasound treatments are both thermally stable and could serve several benefits in the food industry. Previous researchers have reported different denaturation temperatures for commercially and laboratory-prepared faba bean protein isolates. Kimura et al. [12] observed that the 11S fraction of faba bean protein showed Td value of 95.4 °C while the 7S fraction showed a Td value of 83.8 °C. Variations in the denaturation temperature of protein isolates from faba beans could be attributed to extraction conditions, varietal differences, and technique used.

Fig. 5.

DSC spectrum of optimized and control Faba bean protein isolates.

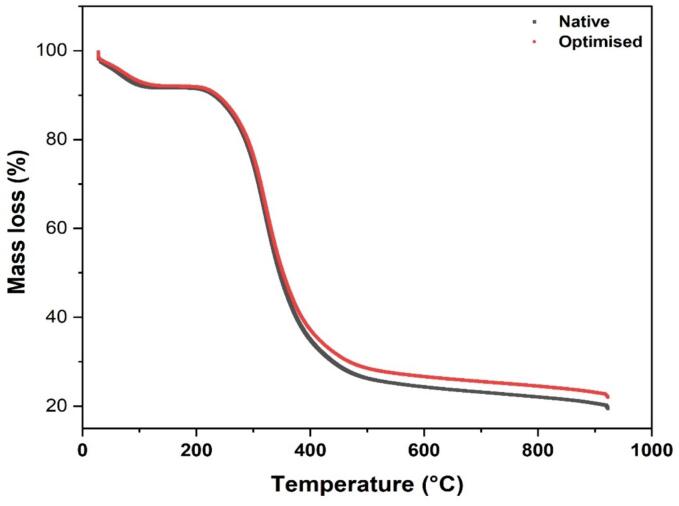

3.8. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermal investigation of proteins is useful for determining the temperature-dependent behaviour of proteins before significant thermal decomposition occurs, which is critical for various food applications. This is of particular interest during high-temperature processes such as cooking, pasteurization, and sterilization [57]. TGA curves of ultrasound-treated and conventional faba bean protein isolates are shown in Fig. 6. Both samples showed similar degradation curves up to 950 °C. Weight loss in the temperature range 0 to 200 °C is often associated with water loss and some volatile compounds. Control samples showed a slightly rapid water loss compared to optimal ultrasound-assisted protein isolate. At temperatures between 200 to 400 °C, there was a drastic weight loss in both samples mostly attributed to the presence of polymeric substances which in this case is proteins. Control protein isolate however showed slightly lower degradation compared to optimal ultrasound-aided extraction from 400 to 900 °C. This observation is related to the structural modifications induced by ultrasound, such as the modification in secondary structure. This finding agrees with the results reported by Mir et al. [58] for album seed protein isolates treated with high-intensity ultrasound. Finally, a slight constant weight loss was observed from 400 to 900 °C, which may be attributed to residual materials such as oxidation products. Comparable results have been reported by Yılmaz & Gultekin Subasi [59] for laurel and Olive protein isolates, and He et al [60] noted a similar pattern for quinoa protein isolates.

Fig. 6.

TGA profile of optimal ultrasound-aid and control Faba beans protein isolates.

4. Conclusion

In this study ultrasound-assisted process parameters for the production of faba bean protein isolate were compared to the conventional alkaline extraction process. Following BBD optimization of the ultrasound process, a higher extraction yield (19. 75 vs 16.41 %) and protein content (92.87 vs 89.88 %) were obtained under optimum conditions (Power (123 W), solute/solvent ratio (0.06) (1:15 g/mL), sonication time (41 min), and total volume (623 mL)) compared to the conventional approach. When comparing the ultrasound-treated FBPI to the conventional protein isolate, the ultrasound FBPI demonstrated enhanced water holding and oil absorption capacities. However, it exhibited a decreased foaming capacity. Both protein isolates showed similar foaming stability. FTIR analysis indicated modifications in the secondary structure and fingerprint regions of the ultrasound FBPI, while electrophoresis studies showed no changes in the primary structure. Thermal analysis using DSC and TGA revealed changes in the thermal characteristic profile of ultrasound-treated FBPI. This provides the opportunity to use the recommended ultrasound optimum parameters in food and industrial settings to produce functional faba bean protein for different food applications.

5. Rights retention statement

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version of this paper arising from this submission.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abraham Badjona: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Robert Bradshaw: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Caroline Millman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. Martin Howarth: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Bipro Dubey: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Abraham Badjona, Email: badjona@shu.ac.uk.

Robert Bradshaw, Email: r.bradshaw@shu.ac.uk.

Caroline Millman, Email: c.e.millman@shu.ac.uk.

Martin Howarth, Email: prof.m.howarth@gmail.com.

Bipro Dubey, Email: b.dubey@shu.ac.uk.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Dong W., et al. Comparative evaluation of the volatile profiles and taste properties of roasted coffee beans as affected by drying method and detected by electronic nose, electronic tongue, and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Food Chem. 2019;272:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zha F., Rao J., Chen B. Modification of pulse proteins for improved functionality and flavor profile: a comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20:3036–3060. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiking H., de Boer J. The next protein transition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;105:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.07.008. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martineau-Côté D., Achouri A., Karboune S., L’Hocine L. Faba Bean: an untapped source of quality plant proteins and bioactives. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14081541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augustin M.A., Cole M.B. Towards a sustainable food system by design using faba bean protein as an example. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022;125:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.04.029. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badjona A., Bradshaw R., Millman C., Howarth M., Dubey B. Faba Beans protein as an unconventional protein source for the food industry: processing influence on nutritional, techno-functionality, and bioactivity. Food Rev. Intl. 2023 doi: 10.1080/87559129.2023.2245036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badjona A., Bradshaw R., Millman C., Howarth M., Dubey B. Faba Bean processing: thermal and non-thermal processing on chemical, antinutritional factors, and pharmacological properties. Molecules. 2023;28 doi: 10.3390/molecules28145431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badjona A., Bradshaw R., Millman C., Howarth M., Dubey B. Faba Bean flavor effects from processing to consumer acceptability. Foods. 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/foods12112237. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelsang-O’Dwyer M., et al. Comparison of Faba bean protein ingredients produced using dry fractionation and isoelectric precipitation: techno-functional, nutritional and environmental performance. Foods. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/foods9030322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Angelis D., et al. Data on the proximate composition, bioactive compounds, physicochemical and functional properties of a collection of faba beans (Vicia faba L.) and lentils (Lens culinaris Medik.) Data Brief. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.H.E.A. El Fiel, A.H. El Tinay, E.A.E. Elsheikh. Effect of nutritional status of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) on protein solubility profiles. (2002). doi:doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00314-9.

- 12.Kimura A., et al. Comparison of physicochemical properties of 7S and 11S globulins from pea, fava bean, cowpea, and French bean with those of soybean-french bean 7S globulin exhibits excellent properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:10273–10279. doi: 10.1021/jf801721b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vioque J., Alaiz M., Girón-Calle J. Nutritional and functional properties of Vicia faba protein isolates and related fractions. Food Chem. 2012;132:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eze C.R., Kwofie E.M., Adewale P., Lam E., Ngadi M. Advances in legume protein extraction technologies: a review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022;82 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2022.103199. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K.H., Ryu H.S., Rhee K.C. Protein solubility characteristics of commercial soy protein products. JAOCS, J. Am. Oil Chemists’ Soc. 2003;80:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meroni D., Djellabi R., Ashokkumar M., Bianchi C.L., Boffito D.C. Sonoprocessing: from concepts to large-scale reactors. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:3219–3258. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00438. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badjona A., Bradshaw R., Millman C., Howarth M., Dubey B. Structural, thermal, and physicochemical properties of ultrasound-assisted extraction of faba bean protein isolate (FPI) J. Food Eng. 2024;377 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.107030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman M.M., Lamsal B.P. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and modification of plant-based proteins: Impact on physicochemical, functional, and nutritional properties. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20:1457–1480. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12709. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusoff I.M., Mat Taher Z., Rahmat Z., Chua L.S. A review of ultrasound-assisted extraction for plant bioactive compounds: phenolics, flavonoids, thymols, saponins and proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022;157 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111268. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ampofo J., Ngadi M. Ultrasound-assisted processing: science, technology and challenges for the plant-based protein industry. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez-Ossorio C., et al. Composition and techno-functional properties of grape seed flour protein extracts. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022;2:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fatima K., et al. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of protein from Moringa oleifera seeds and its impact on techno-functional properties. Molecules. 2023;28 doi: 10.3390/molecules28062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badjona A., Bradshaw R., Millman C., Howarth M., Dubey B. Response surface methodology guided approach for optimization of protein isolate from Faba bean. Part 1/2. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;109 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.107012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loushigam G., Shanmugam A. Modifications to functional and biological properties of proteins of cowpea pulse crop by ultrasound-assisted extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;97 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar M., et al. Advances in the plant protein extraction: mechanism and recommendations. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;115 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadidi M., Orellana Palacios J.C., McClements D.J., Mahfouzi M., Moreno A. Alfalfa as a sustainable source of plant-based food proteins. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023;135:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.03.023. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.S. Zia, P. Moazzam Raaq Khan, R. Muhammad Aadil, I. Gabriela Medina-Meza. Bioactive recovery from watermelon rind waste using ultrasound-assisted extraction. (2023). doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3568664/v1.

- 29.Görgüç A., Bircan C., Yılmaz F.M. Sesame bran as an unexploited by-product: Effect of enzyme and ultrasound-assisted extraction on the recovery of protein and antioxidant compounds. Food Chem. 2019;283:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y., et al. Impact of ultrasonication/shear emulsifying/microwave-assisted enzymatic extraction on rheological, structural, and functional properties of Akebia trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz. seed protein isolates. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;112 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sert D., Rohm H., Struck S. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of protein from pumpkin seed press cake: impact on protein yield and techno-functionality. Foods. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/foods11244029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du H., Zhang J., Wang S., Manyande A., Wang J. Effect of high-intensity ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical, structural, rheological, behavioral, and foaming properties of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.)-seed protein isolates. LWT. 2022;155 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao K., Zha F., Yang Z., Rao J., Chen B. Structure characteristics and functionality of water-soluble fraction from high-intensity ultrasound treated pea protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;125 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chittapalo T., Noomhorm A. Ultrasonic assisted alkali extraction of protein from defatted rice bran and properties of the protein concentrates. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009;44:1843–1849. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang S.Q., Du Q.H., Fu Z. Ultrasonic treatment on physicochemical properties of water-soluble protein from Moringa oleifera seed. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornet S.H.V., Snel S.J.E., Lesschen J., van der Goot A.J., van der Sman R.G.M. Enhancing the water holding capacity of model meat analogues through marinade composition. J. Food Eng. 2021;290 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pico J., Reguilón M.P., Bernal J., Gómez M. Effect of rice, pea, egg white and whey proteins on crust quality of rice flour-corn starch based gluten-free breads. J. Cereal Sci. 2019;86:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao X., Hua Y. Composition, structure and functional properties of protein concentrates and isolates produced from walnut (Juglans regia L.) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:1561–1581. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishinari K., Fang Y., Guo S., Phillips G.O. Soy proteins: a review on composition, aggregation and emulsification. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;39:301–318. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahan K., Ashfaq A., Islam R.U., Younis K., Yousuf O. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted protein extraction from defatted mustard meal and determination of its physical, structural, and functional properties. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022;46 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li R., Xiong Y.L. Ultrasound-induced structural modification and thermal properties of oat protein. LWT. 2021;149 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warsame A.O., Michael N., O’sullivan D.M., Tosi P. Identification and quantification of major Faba bean seed proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:8535–8544. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c02927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevkani K., Singh N., Kaur A., Rana J.C. Structural and functional characterization of kidney bean and field pea protein isolates: a comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;43:679–689. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruan S., et al. Analysis in protein profile, antioxidant activity and structure-activity relationship based on ultrasound-assisted liquid-state fermentation of soybean meal with Bacillus subtilis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh A., Kaur A. Comparative studies on seed protein characteristics in eight lines of two Gossypium species. J. Cotton Res. 2019;2 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou Y., et al. Modifying the structure, emulsifying and rheological properties of water-soluble protein from chicken liver by low-frequency ultrasound treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;139:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’sullivan J., Murray B., Flynn C., Norton I. The effect of ultrasound treatment on the structural, physical and emulsifying properties of animal and vegetable proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;53:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vatansever S., Ohm J.B., Simsek S., Hall C. A novel approach: Supercritical carbon dioxide + ethanol extraction to improve techno-functionalities of pea protein isolate. Cereal Chem. 2022;99:130–143. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mir N.A., Riar C.S., Singh S. Rheological, structural and thermal characteristics of protein isolates obtained from album (Chenopodium album) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) seeds. Food Hydrocoll. Health. 2021;1 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amir R.M., et al. Application of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for the identification of wheat varieties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;50:1018–1023. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0424-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carbonaro M., Maselli P., Nucara A. Relationship between digestibility and secondary structure of raw and thermally treated legume proteins: a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic study. Amino Acids. 2012;43:911–921. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-1151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Surdu V.A., Győrgy R. X-ray diffraction data analysis by machine learning methods—A review. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland) 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/app13179992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ameh E.S. A review of basic crystallography and x-ray diffraction applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019;105:3289–3302. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J., et al. Determination of the domain structure of the 7S and 11S globulins from soy proteins by XRD and FTIR. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013;93:1687–1691. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moghadam M., Salami M., Mohammadian M., Emam-Djomeh Z. Development and characterization of pH-sensitive and antioxidant edible films based on mung bean protein enriched with Echium amoenum anthocyanins. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021;15:2984–2994. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seiwert K., Kamdem D.P., Kocabaş D.S., Ustunol Z. Development and characterization of whey protein isolate and xylan composite films with and without enzymatic crosslinking. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;120 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sá A.G.A., Moreno Y.M.F., Carciofi B.A.M. Food processing for the improvement of plant proteins digestibility. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;60:3367–3386. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1688249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mir N.A., Riar C.S., Singh S. Physicochemical, molecular and thermal properties of high-intensity ultrasound (HIUS) treated protein isolates from album (Chenopodium album) seed. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;96:433–441. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yılmaz H., Gultekin Subasi B. Distinctive processing effects on recovered protein isolates from Laurel (Bay) and olive leaves: a comparative study. ACS Omega. 2023 doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c04482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He X., et al. Effect of hydrothermal treatment on the structure and functional properties of quinoa protein isolate. Foods. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/foods11192954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available upon reasonable request.