Abstract

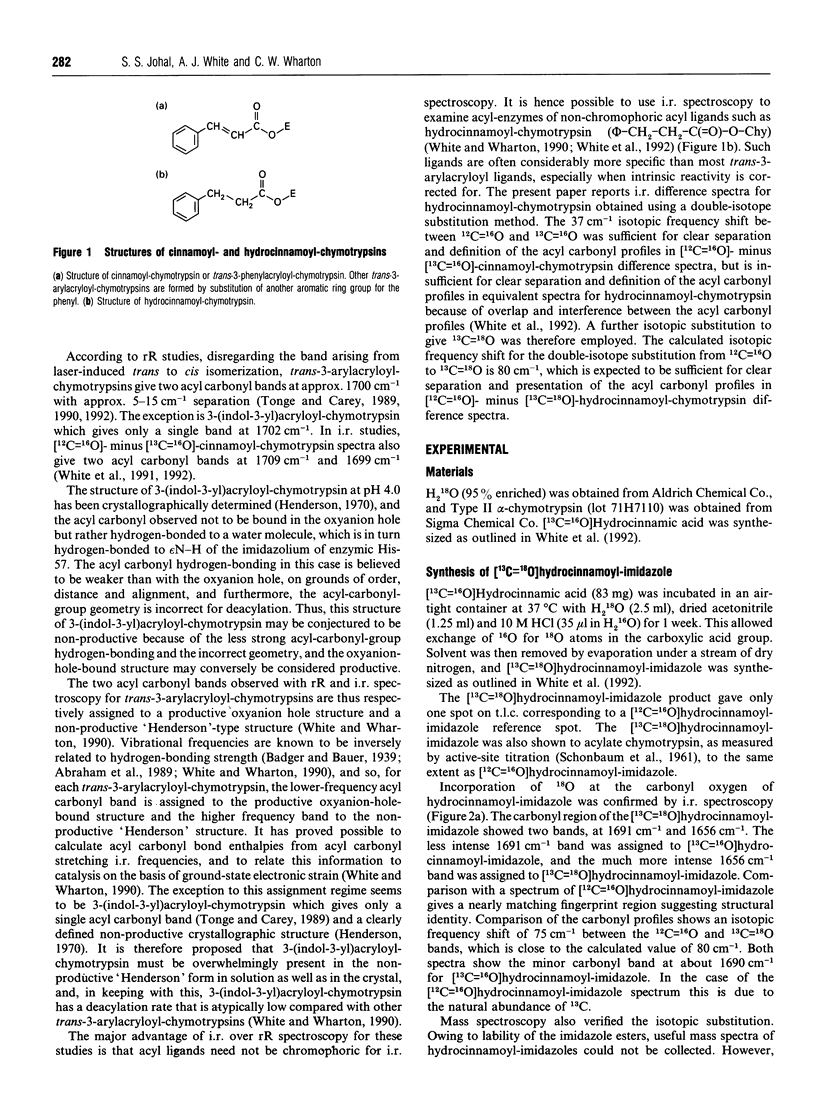

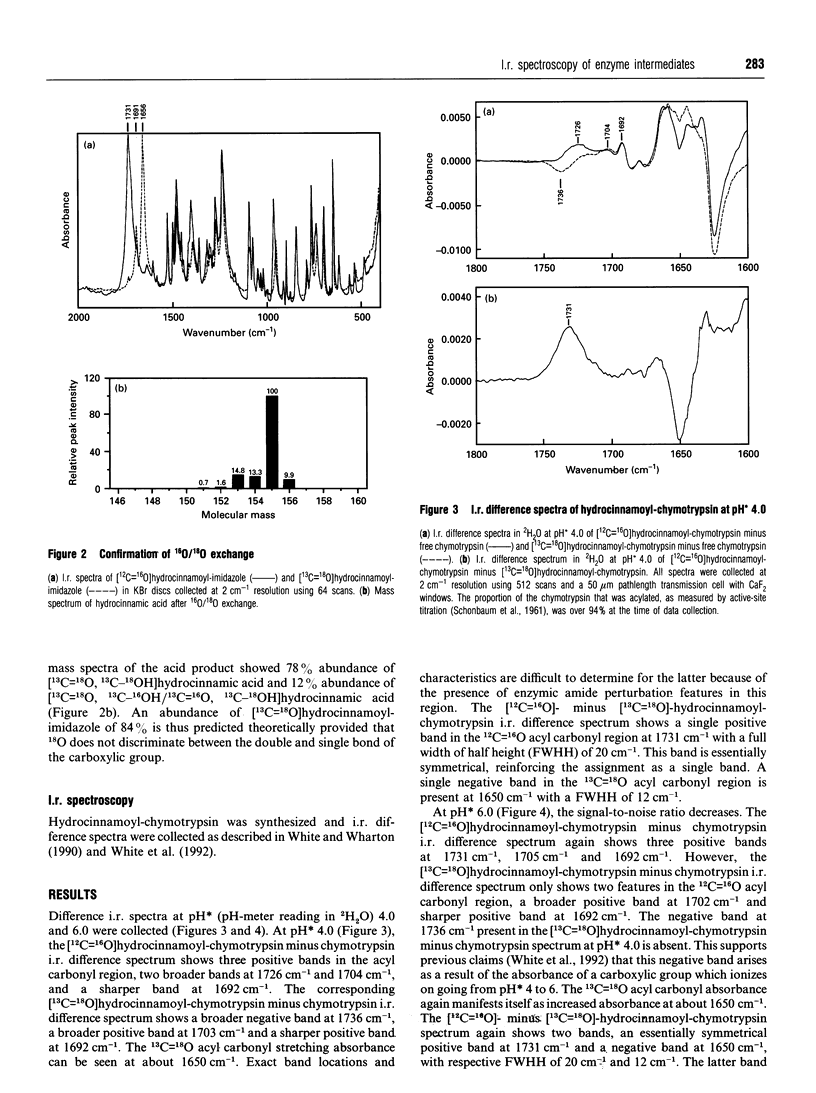

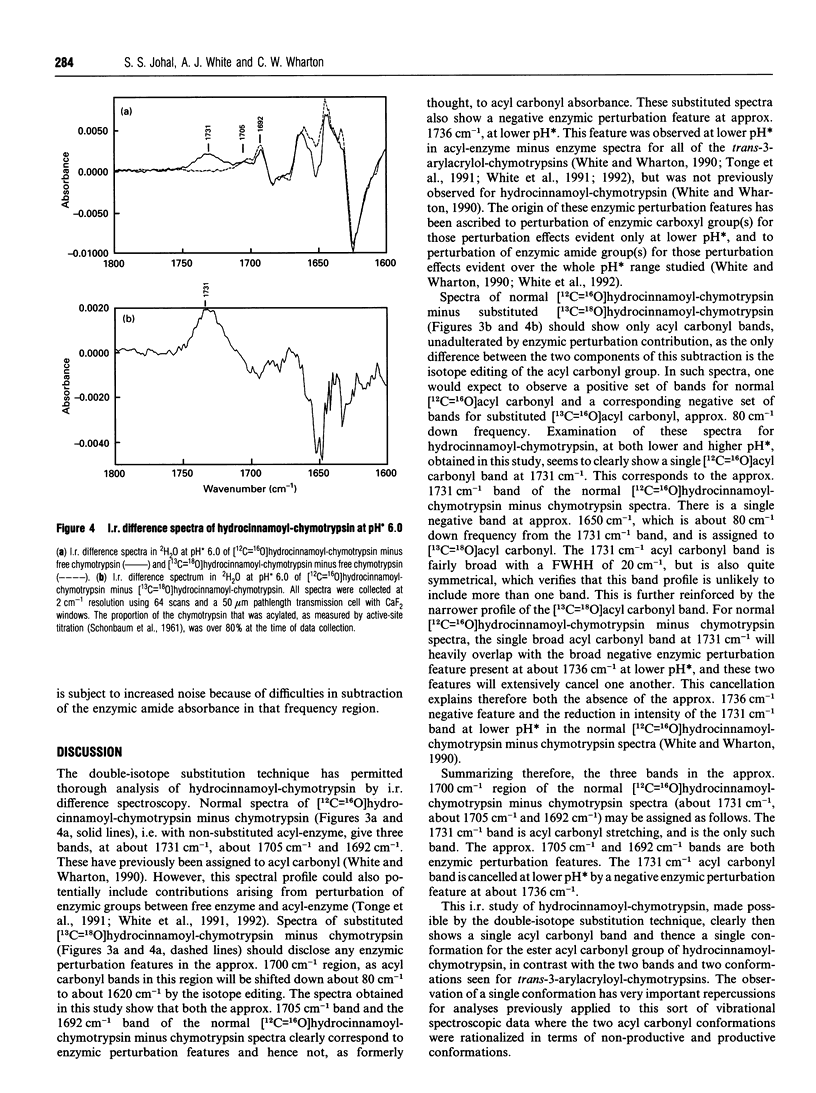

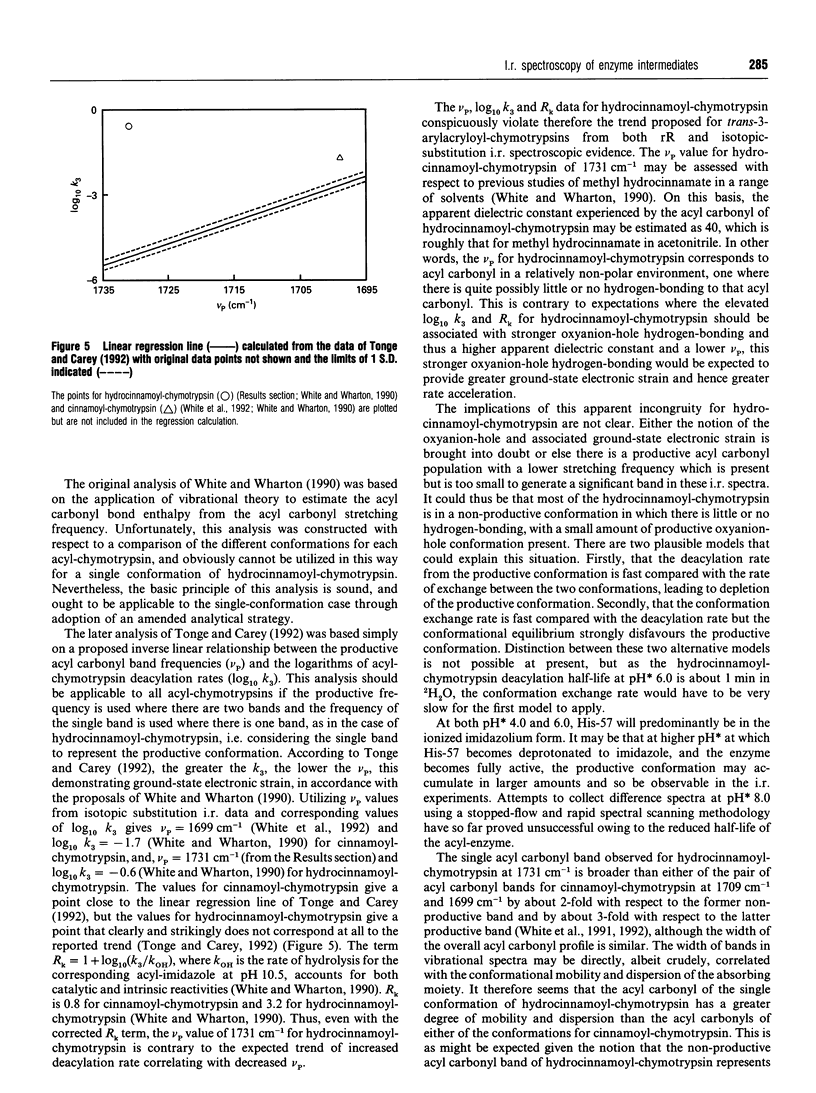

I.r. difference spectroscopy combined with 13C and 18O double-isotope substitution was used to examine the ester acyl carbonyl stretching vibration of hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin. A single acyl carbonyl stretching band was observed at 1731 cm-1. This contrasts with previous i.r. and resonance Raman spectroscopic studies of a number of trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins which showed two acyl carbonyl stretching bands in the region of 1700 cm-1, which were proposed to represent productive and non-productive conformations of the acyl-enzyme. The single acyl carbonyl band for hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin suggests only a single conformation, and the comparatively high frequency of this band implies little or no hydrogen-bonding to this carbonyl group. Enzymic hydrogen-bonding to the acyl carbonyl is believed to give bond polarization and thereby catalytic-rate acceleration. Thus, in view of the apparent lack of such hydrogen-bonding in hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin, it should be the case that this acyl-chymotrypsin is less specific than trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins, whereas the opposite is true. It is therefore proposed that there may be a productive acyl carbonyl population of lower stretching frequency for hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin, but that this is too small to be discerned because of either a relatively high deacylation rate or an unfavourable conformational equilibrium. The single acyl carbonyl band for hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin is significantly broader than those for trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins, indicating that this group is more conformationally mobile and dispersed in the former. This can be correlated with the absence of acyl carbonyl hydrogen-bonding in hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin, and with the much greater flexibility of the saturated hydrocinnamoyl group than unsaturated trans-3-arylacryloyl. This flexibility is presumably the reason why hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin is more specific than trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins. Resonance Raman spectroscopy is limited to the non-specific trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins because of its chromophoric requirement, whereas i.r. may be used to examine non-chromophoric more specific acyl-enzymes such as hydrocinnamoyl-chymotrypsin. The results presented in this paper suggest that trans-3-arylacryloyl-chymotrypsins are atypical.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alber T., Petsko G. A., Tsernoglou D. Crystal structure of elastase-substrate complex at -- 55 degrees C. Nature. 1976 Sep 23;263(5575):297–300. doi: 10.1038/263297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan P., Pantoliano M. W., Quill S. G., Hsiao H. Y., Poulos T. Site-directed mutagenesis and the role of the oxyanion hole in subtilisin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jun;83(11):3743–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Zheng J., Sloan D., Burgner J., Callender R. A vibrational analysis of the catalytically important C4-H bonds of NADH bound to lactate or malate dehydrogenase: ground-state effects. Biochemistry. 1992 Jun 2;31(21):5085–5092. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Zheng J., Sloan D., Burgner J., Callender R. Classical Raman spectroscopic studies of NADH and NAD+ bound to lactate dehydrogenase by difference techniques. Biochemistry. 1989 Feb 21;28(4):1525–1533. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. Structure of crystalline alpha-chymotrypsin. IV. The structure of indoleacryloyl-alpha-chyotrypsin and its relevance to the hydrolytic mechanism of the enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1970 Dec 14;54(2):341–354. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertus J. D., Kraut J., Alden R. A., Birktoft J. J. Subtilisin; a stereochemical mechanism involving transition-state stabilization. Biochemistry. 1972 Nov 7;11(23):4293–4303. doi: 10.1021/bi00773a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHONBAUM G. R., ZERNER B., BENDER M. L. The spectrophotometric determination of the operational normality of an alpha-chymotrypsin solution. J Biol Chem. 1961 Nov;236:2930–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz T. A., Henderson R., Blow D. M. Structure of crystalline alpha-chymotrypsin. 3. Crystallographic studies of substrates and inhibitors bound to the active site of alpha-chymotrypsin. J Mol Biol. 1969 Dec 14;46(2):337–348. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonge P. J., Carey P. R. Forces, bond lengths, and reactivity: fundamental insight into the mechanism of enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 1992 Sep 29;31(38):9122–9125. doi: 10.1021/bi00153a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonge P. J., Carey P. R. Length of the acyl carbonyl bond in acyl-serine proteases correlates with reactivity. Biochemistry. 1990 Dec 4;29(48):10723–10727. doi: 10.1021/bi00500a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonge P. J., Pusztai M., White A. J., Wharton C. W., Carey P. R. Resonance Raman and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic studies of the acyl carbonyl group in [3-(5-methyl-2-thienyl)acryloyl]chymotrypsin: evidence for artifacts in the spectra obtained by both techniques. Biochemistry. 1991 May 14;30(19):4790–4795. doi: 10.1021/bi00233a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S. J., Seibel G. L., Kollman P. A. The nature of enzyme catalysis in trypsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Feb;83(3):649–653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. A., Estell D. A. Subtilisin--an enzyme designed to be engineered. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988 Aug;13(8):291–297. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton C. W. Infra-red and Raman spectroscopic studies of enzyme structure and function. Biochem J. 1986 Jan 1;233(1):25–36. doi: 10.1042/bj2330025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. J., Drabble K., Ward S., Wharton C. W. Analysis and elimination of protein perturbation in infrared difference spectra of acyl-chymotrypsin ester carbonyl groups by using 13C isotopic substitution. Biochem J. 1992 Oct 1;287(Pt 1):317–323. doi: 10.1042/bj2870317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. J., Drabble K., Wharton C. W. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of (13C=O) trans-cinnamoyl- and (13C=O) hydrocinnamoyl-a-chymotrypsins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991 Apr;19(2):159S–159S. doi: 10.1042/bst019159s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. J., Wharton C. W. Hydrogen-bonding in enzyme catalysis. Fourier-transform infrared detection of ground-state electronic strain in acyl-chymotrypsins and analysis of the kinetic consequences. Biochem J. 1990 Sep 15;270(3):627–637. doi: 10.1042/bj2700627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]