Abstract

Background

For Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) youth transitioning from child to adult services, protocols that guide the transition process are essential. While some guidelines are available, they do not always consider the effective workload and scarce resources. In Italy, very few guidelines are currently available, and they do not adhere to common standards, possibly leading to non-uniform use.

Methods

The present study analyzes 6 protocols collected from the 21 Italian services for ADHD patients that took part in the TransiDEA (Transitioning in Diabetes, Epilepsy, and ADHD patients) Project. The protocols’ content is described, and a comparison with the National Institute for Clinical Health and Excellence (NICE) guidelines is carried out to determine whether the eight NICE fundamental dimensions were present.

Results

In line with the NICE guidelines, the dimensions addresses in the 6 analyzed documents are: early transition planning (although with variability in age criteria) (6/6), individualized planning (5/6), and the evaluation of transfer needs (5/6). All protocols also foresee joint meetings between child and adult services. The need to include the families is considered by 4 out of 6 protocols, while monitoring (2/6), and training programs (1/6) are less encompassed. In general, a highly heterogeneous picture emerges in terms of quality and quantity of regulations provided.

Conclusions

While some solid points and core elements are in common with international guidelines, the content’s variability highlights the need to standardize practices. Finally, future protocols should adhere more to the patients’ needs and the resources available to clinicians.

Keywords: Transition care, ADHD, Protocols

Background

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that has as core symptoms impulsiveness, inattentiveness, and hyperactivity [1]. It affects up to 5% of children under 18 worldwide, ranging between 0.85% and 10% in childhood and adolescence [2, 3]. In Italy alone, the estimated prevalence is 1.4% (from 1.1 to 3.1%) among children aged 5 to 17 years [4], with a wide variability of age at time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in children living in European countries [5]. As in the case of other neurodevelopmental disorders, the onset of ADHD symptoms occurs during childhood and adolescence, and around 7% of patients continue to manifest symptoms in their adult life [6]. Adolescence is especially critical in this regard, being characterized by physical, psychological, and social changes [7–10]. The insecurity that comes with such changes can also affect the transition from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) [11].

However, many studies that conducted surveys or interviews with patients and their caregivers describe dissatisfaction and feelings of being left alone [12, 13]. Patients often report the need for AMHS to work more closely with them and their carers and the need for the transition to start earlier [14]. The semi-structured interviews conducted within the TRAMS study [15] highlighted four themes perceived as fundamental towards a successful transition: good clinician qualities and positive and transparent relationships with them, sharing the responsibility of the care continuity with parents, care provision independently of nature and severity of problems, and addressing concerns about AMHS services.

As reported by several studies [14, 16], the National Institute for Clinical Health and Excellence [17] ADHD guidelines first provided a clear systematization for transitioning from child to adult services. These guidelines can be summarized in eight points:

Young people with ADHD should be transferred to adult mental health services (AMHS) if they continue to have significant ADHD symptoms or other coexisting conditions that require treatment (Evaluation of transfer need);

The transition should be planned in advance by both the referring and the receiving service (Early transition planning);

The transfer should be completed by the time the patient is 18 years of age (although precise timing may vary locally) (Transition completed by 18 years);

A re-assessment of patients’ needs should be done at school-leaving age (Re-evaluation at school-leaving age);

During the transition to adult services, a formal meeting involving both CAMHS and AMHS should be considered, and complete information about the adult service should be provided to the patient (Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting);

The young person and, when appropriate, the parent/carer should be involved in the transition planning (Family involvement);

After the transition, a comprehensive patient assessment of personal, educational, occupational, and social functioning (keeping in consideration coexisting conditions) should be carried out at the adult service (Patient assessment after transition/monitoring);

Specialist ADHD teams for children, young people, and adults should jointly develop age-appropriate training programs for diagnosing and managing ADHD (Training programs).

Available international research is based mainly on the National Institute for Clinical Health and Excellence (NICE) guidance for managing ADHD. However, only a few available guidelines outlined explicit transition recommendations (e.g., the Ready Steady Go Programme and the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance guidelines) [2, 14, 16]. The “Six Core Elements” American recommendations are another interesting attempt towards guiding healthcare transition [18, 19]. The foundations of this transition and care guide are tracking and monitoring progress, administering transition readiness assessments, planning for transition (which includes helping the patient transition to an adult approach to care), and providing ongoing care [20]. While this guide provides valuable tools in the preparation phase, the self-assessment of patients to evaluate transition readiness, and the inclusion of families in the process, it does not regulate transition timing, joint meetings between services, or monitoring after the conclusion of the process.

While these guidelines seem to respond to the patient’s needs and concerns, clinicians stated that at a practical level, it is not always possible to follow these recommendations due to workload and scarce resources [16, 21, 22]. Moreover, the uncertainties and gaps in knowledge translate into not knowing how to share information with young people and their families [23].

This fragmented picture highlights the need to develop precise tools and adapt internationally available recommendations to specific national clinical practices. Such tools should be modeled on a medical protocol, i.e., one that can be defined as a set of predetermined criteria regulating interventions for effective patient care management. It should be evidence-based, updated, and responsive to the needs of patients in defined care settings. A protocol to guide the what, how, and when of transition should thus be a priority of healthcare systems [24] and guaranteed in an appropriate care pathway.

In Italy, the need for a similar protocol is particularly salient. Indeed, there is no unified transition practice [25], and the quantity and quality of existing guidelines were to date never investigated.

The aim of the present study was two-fold: (1) to collect the available, even if scarce, existing guidelines on the Italian territory and compare them with the eight points of the NICE guidelines, and (2) to identify the essential points that a practical and effective protocol in daily practice should address.

Methods

The protocols described in the present work were collected within the Italian TransiDEA (Transitioning in Diabetes, Epilepsy, and ADHD patients) Project, which evaluated the transition process from adolescence to adult services in the ADHD, Epilepsy, and Diabetes fields. Two surveys were developed, one for pediatric and one for adult services. The details of the survey’s structure and the results of the 42 Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and 35 Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) who filled in the survey for the ADHD branch have been reported in a separate publication [26].

Along with questions regarding general information on the services (region, type of service, number of patients, pharmacological treatments) and questions on the transition process, the survey asked whether CAMHS and AMHS services had a transition protocol, and if so, whether it was specific for ADHD patients or generic. Only 24% (n = 10) of the participating CAMHS and 32% (n = 11) of the AMHS reported having a transition protocol. In particular, 7 CAMHS were in the north, 1 in the center, and 2 in the south. Similarly, 7 AMHS were in the north, 3 in the center, and 1 in the south. 3 CAMHS and 2 AMHS reported having a protocol specific to ADHD patients. We then asked these 21 services to send us a copy of their transition protocols to analyze their content. The protocol analysis was qualitative, based on previous protocol recommendations, and following the process recommended for thematic analysis [27]. In particular, we sought to determine whether the eight dimensions reported by the NICE guidelines as fundamental in a transition protocol were present [14]. As a 9th dimension, we added the individualized planning of the transition pathway, which, although largely considered in the NICE guidelines, was never described as a dimension of its own. Moreover, we added the number of pages of each protocol as additional information. This last point, even though it cannot be considered a criterion for protocol evaluation per se, is particularly interesting at a descriptive level as it highlights the large variability in terms of content quantity. In summary, the ten dimensions we considered were: (D1) Evaluation of transfer need; (D2) Early transition planning; (D3) Individualized planning; (D4) Transition completed by 18 years; (D5) Re-evaluation at school-leaving age; (D6) Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting; (D7) Family involvement; (D8) Patient assessment after transition/monitoring; (D9) Training program; (10) Number of pages.

Results

Six protocols were collected from the 21 centers that participated in the survey and reported a protocol, four from CAMHS and two from AMHS, none specific for ADHD patients.

All protocols assume that transition planning should start early (D2), ranging from 14 years (1 protocol) to a general “months before turning 18” (Table 1). Five out of 6 protocols mention the importance of individualized planning (D3) and of evaluating transfer needs, although only 3 detail what needs should be considered to individualize the pathway. The first of these three specifies the following aspects: personal, diagnostic, and anamnestic data; the reason for referral and intervention objective; functioning in different areas of life (social functioning, work, autonomy); care needs and social context; possible substance use or other addictive behavior. Similarly, another protocol indicates that, for each patient, the transition should consider the condition’s history and clinical course, the personal and family history, and the most relevant social aspects (although the term “individualized plan” never appears in the protocol). A third one creates a specific pathway in terms of social integration (school, employment, work, etc.) involving the community social services network, schools, employment services, daycare services for people with disabilities, etc.

Two services reported that the age for referral (D4) should be 18 years. In contrast, one of the services stated a broad “between the ages of 14 and 25”, another one “one month after turning 18,” and a third one did not give any indications. One protocol mentioned the possibility of designing “soft transition” paths. This means more gradually approaching the changes the patient will have to undergo, as confirmed by the fact that this protocol indicated the youngest age for starting transition planning (14 years old).

All protocols foresee and regulate joint CAMHS-AMHS meetings (D6), while 4 include the families’ involvement (D7) as fundamental. Patient monitoring (D8) and re-evaluation at school-leaving age (D5) seem to be widely left out (only 2 out of 6 documents elaborate on these themes). The same goes for training programs (D9), which are only mentioned by one of the guidelines. Finally, one protocol anticipated the possibility of continuing the care pathway at the CAMHS where needed.

The number of pages (10) differed widely, going from 2 to 3 pages to 20 pages. Moreover, a service had a main, 9-page document and specific documents for individual local services, ranging from 8 to 25 pages.

Table 1.

Column one reports the nine fundamental protocol dimensions outlined in the NICE guidelines and that emerged from our protocols (individualized planning), along with the number of pages. Columns 2 to 7 indicate whether each of the analyzed protocols reported such dimensions. Under each protocol we reported the type of service (CAMHS, AMHS) and the number of patients and transitioning patients in the year previous to the survey, conducted between December 2021 and May 2022 (only referring to ADHD patients)

| Dimensions | Protocol 1 AMHS (40 patients, 15 transitioning) |

Protocol 2 AMHS (3 patients, 2 transitioning) |

Protocol 3 CAMHS (113 patients, 4 transitioning) |

Protocol 4 CAMHS (100 patients, 11 transitioning) |

Protocol 5 CAMHS (300 patients, 2 transitioning) |

Protocol 6 CAMHS (210 patients, 8 transitioning) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Evaluation of transfer need | Evaluation of requirements for the specific patient (where a long care pathway is not foreseen, the patient can stay in CAMHS until needed) | Particular attention to severe disorders that require intensive treatment and/or supportive interventions | Evaluate the complexity of each case. If needed, for continuity of care patients can stay in CAMHS after turning 18 | X | Only briefly mentioning severity of symptoms | Decided with the family based on the final clinical report |

| D2 | Early transition planning | At least 6 months before turning 18, as early as possible after turning 17 | Starting at age 14; at least 6 months before turning 18 | From 16, usually 6/12 months before turning 18 depending on complexity of the case | Yes (Therapeutic Project sent to adult services 6 months before patients turn 18) | Report sheet sent 3 months before patient turns 18 | Between 17 and 18 years. First meeting “months before” turning 18 |

| D3 | Individualized planning | Personal, diagnostic and anamnestic data; reason for referral and intervention objective; functioning in different areas of life (social functioning, work, autonomy); care needs and social context; possible substance use or other addictive behavior | Individual plan after evaluation of diagnostic picture | Specific pathway for social integration (school, employment, work, etc.) involving the community social services network, schools, employment services, etc. | X (“Development of an individualized therapeutic plan, complex and integrated”, but how not explained) | X (“Development of a subsequent individualized therapeutic-rehabilitation project”, but how not explained) | History and clinical course, personal and family history, and the most relevant social aspects |

| D4 | Transition completed by 18 years | Yes | X (Between 14 and 25, not specified) | Yes | 1 month after turning 18 maximum | X | X (Not mentioned) |

| D5 | Re-evaluation at school-leaving age | X | X (only briefly mentioned, but for transfer and not for re-evaluation) | X | X | X | X |

| D6 | Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting and information sharing | Functionally integrate all services involved (how not specified) | First contact via email (specifying urgency of transfer); advised to follow up with a phone call. Case discussed within 15 days | Presentation of the case (can be done online), followed by 2 or 3 joint meetings | AMHS receives a therapeutic-rehabilitation project by CAMHS in the year before the patient turns 18; technical meeting with all involved services (at least 3 months before turning 18) | Periodic meetings to monitor the process | 1 technical meeting CAMHS + AMHS, followed by 1 meeting with AMHS, the patient, and the caregivers (the CAMHS can also be present, but only if necessary) |

| D7 | Family involvement | Include and involve families together with the patients (support with social services if necessary) | Active participation of family members in the transition and construction of a new care and assistance program | Families take part in meetings and bring reports of the diagnostic-therapeutic pathway to the AMHS clinicians | X | X | Meeting with CAMHS to be informed about transfer options; meeting with AMHS |

| D8 | Patient assessment after transition / monitoring | Partial (request confirmation of successful take-over) | Updates every 3 months | X | X | X | X |

| D9 | Training program | Joint training for CAMHS and AMHS clinicians | X | X | X | X | X |

| 10 | Number of pages | 25 | All: 9; Specific for different centers (25, 9, 9, 5, 5, 8) | 4 | 8 | 23 | 2 |

| 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 2/9 | 2/9 | 5/9 |

Discussion

International guidelines, such as the NICE guidelines in the U.K. and the American “Six Core Elements”, attempt to systematize the transition process from CAMHS to AMHS. While they try to include local health services in their consultation, such services often fail to implement them locally [16]. Whether this reflects the low adherence to the clinical practice or a broader lack of resources, the emerging picture is critical. The present study analyzed whether the six Italian protocols (Table 1) follow the structure of international guidelines or adopt different strategies.

As for what concerns transition planning, all Italian protocols considered the need for individualized planning, albeit with varying degrees of detail as to what to consider. The evaluation of transfer needs was, in line with the NICE guidelines, considered by almost all centers (only one did not foresee such a preparation phase). All protocols considered the age criterion, although it differed widely between services. The NICE guidelines suggest starting at 15-and-a-half years of age. Early planning is often mentioned in the Italian protocols, but it does not seem clear when to start optimal transition planning [28]. One of the protocols analyzed here suggests discussing the changes the patient will undergo at 14 years of age, consistently with the Six Core Elements framework. Inversely, the other 5 protocols tend to indicate 17 years of age (or 6 to 3 months before turning 18) as the time to start planning. Even if this age is higher than that indicated by international guidelines, the fact that 5 out of 6 protocols report it shows that organizational practices do not currently challenge this criterion. Future policies could attempt to establish the 16-year mark (a trade-off between Italian practices and international suggestions) as the moment to start planning the transition.

Moreover, most studies and respondents from the survey that was previously conducted within the same Project seem to report that transition should be completed by age 18 and, at the same time, that ideally, the criteria for referral should be 18 years of age. This is mainly due to the Italian Health System organization, which states that patients should not remain in pediatric services’ care after turning 18. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that, in practice, this indication is difficult to follow; within the guidelines received, only 2 reported such a cutoff, while most protocols were vague (e.g., between 14 and 25 years, or “months after turning 18”). Moreover, a consensus is growing that the 18-year norm may not be in the best interest of young patients [29]. Another criterion that might be worth considering is not using the age of 18, but the end of a school cycle (See Scarpellini & Bonati, 2022, for ages reported in different studies) [30]. Yet, such a possibility is never mentioned in the analyzed protocols. Future guidelines might suggest re-evaluating the patients in that particular moment as part of the monitoring aspect.

All services have in common with the NICE guidelines that the working group included many professional figures, including CAMHS and local clinicians, who also foresee joint meetings. Families’ involvement is also frequently considered (from 4 out of 6 protocols). This multi-perspective approach is undoubtedly the most universally recognized strength in a transition process and should be followed when drafting protocols.

On the other hand, a few points pivotal in the NICE document are less addressed in Italian regulations. In particular, patient assessment and monitoring after transition, as well as providing training programs for professionals, should be implemented in future shared recommendations.

Lastly, the difference in content quantity in the analyzed protocols is an interesting point to consider. The core information and level of protocol completeness do not seem to relate to the number of pages. Contrarily, one of the most extensive protocols analyzed in the present study (23 pages) addressed only two core transition elements to a satisfactory extent. On the other hand, the 2-page protocol covered more points, although not thoroughly (7 of the 9 included).

The limit of the present study is that it describes a small number of protocols. Only 29% of the centers that participated in the previous survey declared having a protocol, a low rate for an instrument aimed at guaranteeing an appropriate care pathway. Moreover, not all of those services were willing to share their documents, making examining all practices in use impossible. Yet, collecting 6 protocols allowed a random selection of different document types. At the same time, an improvement at a regional level emerged. As of 2018, only four CAMHS had transition protocols in the Lombardy region in Italy [31]. Data collected in the 2022 survey indicated an increase (out of 21 centers with a protocol, 6 were in Lombardy), which, although small, remains a positive trend.

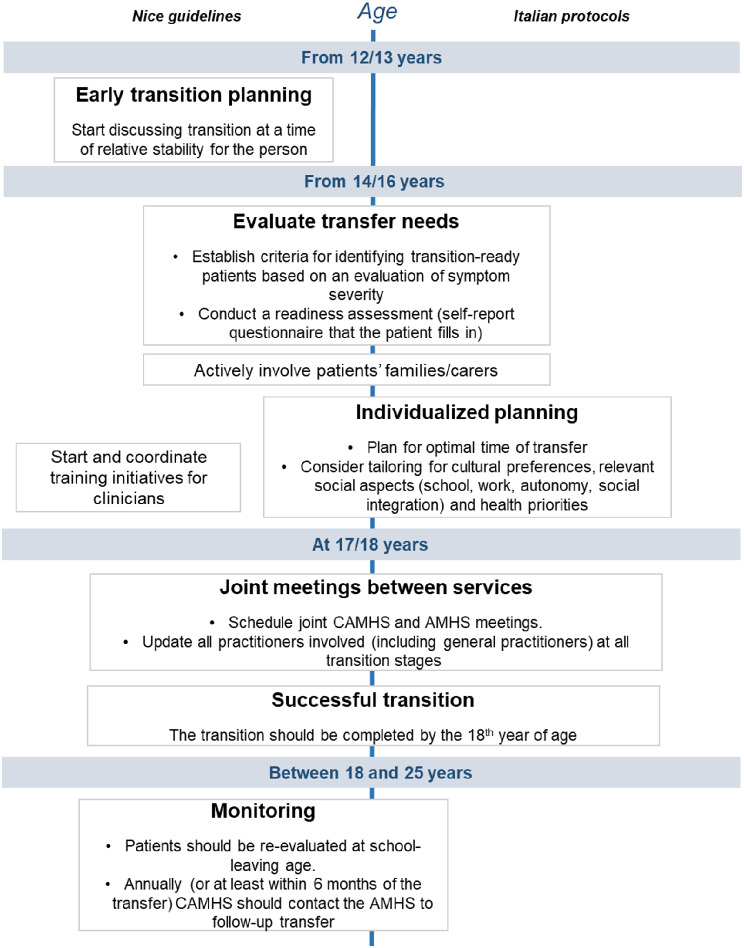

A macroscopic comparison of the Italian protocols, the NICE, and the “Six Core Element” guidelines (Table 2) reveals a clear picture of what should be included in an ideal protocol. First, a discussion about transition planning should be conducted with patients and their families as early as possible (e.g., at 16 years of age). In this phase, patients and clinicians should agree on a timeline, including establishing criteria to detect transition-ready patients and regularly conducting readiness assessments. Tracking readiness over 5 years can effectively show when adolescents meet the criteria for transitioning [32]. Periodically, or at least at the age of 17, joint meetings should be foreseen to ensure a successful transition by age 18. In the following years (or after at least 6 months), CAMHS should follow up on transfer to ensure that patients are appropriately supported. The patients and their families must be actively involved and informed in all process steps [33]. Training the clinicians in all the necessary steps and their importance is also crucial [34, 35]. These steps are summarized in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Column one reports the fundamental protocol dimensions outlined in the NICE guidelines and that emerged from our protocols (individualized planning and number of pages). Column 2 reports the definition and ideal parameters of such dimensions. Column 3 compares the ideal definition foreseen by the guidelines with practical observations collected in the 2021/2022 survey. Column 4 summarizes the guidelines collected in the protocols described in the present paper.

| Dimensions | U.K. | U.S. | Italy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NICE GUIDELINES | 6 CORE ELEMENTS | SURVEY DATA (42 pediatric and 35 adult services) | PROTOCOLS (n = 6) | ||

| D1 | Evaluation of transfer need | Transfer to adult mental health services in presence of significant ADHD symptoms or other coexisting conditions that require treatment. Transition planning must be developmentally appropriate | Establish criteria for identifying transition-aged patients. Conduct regular readiness assessments | Age and clinical features (comorbidities, severe symptoms, drug treatment) | Most protocols include evaluation of complexity/severity of symptoms |

| D2 | Early transition planning | From age 13 or 14. Indication to start planning early. Do not use a rigid age threshold, but start transition at a time of relative stability for the young person | Start discussing it at age 12 and planning it at age 14 to 16 | Most pediatric services start at age 17 or 18; one service starts at 15 and one at 21 | On average 6 months before age 18. Some mention as early as possible after turning 17, only one plans to start at age 14 |

| D3 | Individualized planning | -** | Plan for optimal timing of transfer. Consider tailoring for cultural preferences and health priorities | Lack of resources makes it hard to plan individual transition pathways | Evaluating diagnostic picture and relevant social aspects (school, work, autonomy, social integration) |

| D4 | Transition completed by 18 years | Transition should be completed by 18 |

N.A. (Transfer young adults when their condition is as stable as possible) |

Age 15 to 21; median at age 18 | Only around 50% of the protocols foresee completing transition by age 18 |

| D5 | Re-evaluation at school-leaving age | A young person with ADHD receiving treatment and care from CAMHS or pediatric services should be reassessed at school-leaving age to establish the need for continuing treatment into adulthood | NA | Only two pediatric services consider school, but during transition and not for a subsequent re-evaluation | NA |

| D6 | Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting and information sharing | Update all the practitioners involved, including general practitioners | Build ongoing and collaborative partnership with specialty care clinicians | 69% of the pediatric services and 60% of the adult services have joint meetings | All protocols have the indication to program joint meetings |

| D7 | Family involvement | Co-produce transition policies and strategies with young people and their carers; ask them if the services helped them achieve agreed outcomes and give them feedback about the effect their involvement has had. Ask the young patients how they would like their carers to be involved | Plan transfer also with parents/caregivers. Elicit parent/caregiver feedback on their experience with the transition | 67% of the pediatric services and 60% of the adult services have meetings with the families | Families are regularly updated and often actively involved in the transition planning phase |

| D8 | Patient assessment after transition / monitoring | Hold annual meetings to review transition planning. Follow up until age 25 when needed (for a minimum of 6 months after transfer) | Integrate with electronic medical records when possible. Contact young adults and caregivers 3 to 6 months after last pediatric visit to confirm attendance at first adult appointment | 9% of the pediatric services and 15% of the adult services plan patients’ monitoring | One protocol requests confirmation of the successful take-over; one protocol programs updates every 3 months |

| D9 | Training program | Start and coordinate local training initiatives (including for teachers). Specialist ADHD teams (child and adult psychiatrists, pediatricians, and other child and adult mental health professionals) jointly develop and undertake training programs | Educate all staff about the practice’s approach to transition. Offer education and resources on needed skills to patients/caregivers | None. Lack of training often reported as a limit and unmet need | Only one protocol foresees joint training for pediatric and adult services |

**Individual planning is never mentioned ad one of the NICE guidelines dimensions (e.g., Young et al., [14], and Eke et al., [16]). When reading the guidelines, however, several points are clearly found to suggest an individualization of the pathway. In point 1.1.4, for instance, the guidelines suggest using “person-centered” approaches, supporting the single patient in making decisions regarding their pathway, and addressing relevant outcomes and the young person’s goals. During transition, a “developmentally appropriate” support must be provided, taking into account the person’s maturity, cognitive abilities, psychological status, needs in consideration of long-term conditions, social and personal circumstances, caring responsibilities, and communication needs. Furthermore, regarding family involvement, the guidelines state: “adults’ services should take into account the individual needs and wishes of the young person when involving parents or carers…”

Fig. 1.

Example of the transition process steps based on the NICE guidelines and the protocols analyzed in the present paper

Conclusions

Drafting comprehensive and practical recommendations that address clinicians’ and patients’ needs, that are evidence-based, consider clinical practice variations, and can positively affect the quality of care should be a priority [36, 37]. We believe this should include implementing clear communication with the families, providing information on the available services, managing the contacts with the specialists, and offering flexibility in the care pathway based on the symptoms’ severity [38]. Another critical point that must be considered is clarifying the specialists’ role in creating reports or directly communicating with general practitioners and educational services, since parents usually perceive it as a burden to be the carriers of information between different services [12]. One of the crucial points is to manage expectations. If patients and their families have unrealistic expectations, the transition process will be perceived as a failure regardless of how it is managed [15]. Moreover, a clear transition timeline should be outlined, guided by patient needs and foreseeing an adequate number of meetings. Finally, successful future guidelines must contain a reasonable amount of information and be defined based on the resources available to overcome the issues reported with existing policies. This will imply defining the guidelines with clinicians so that the actors involved in the transition process have an active voice. Implementing all these points in Italian recommendations will be the aim of one part of this study. After collecting information directly from the main actors of the transition (children, families, and clinicians), a document will be drafted. A Delphi consensus will then be carried out to review the document with the help of a multidisciplinary panel. Although based on the Italian reality, we intend to present a model that can be replicated internationally to shape future transitioning recommendations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the TransiDEA Group members: Coordinating and Managing Group: Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milan, Italy: Maurizio Bonati, Antonio Clavenna, Nicoletta Raschitelli, Francesca Scarpellini, Elisa Roberti, Rita Campi, Michele Giardino, Michele Zanetti: Diabetes (D): AUSL della Romagna, Ravenna, Italy: Vanna Graziani, Federico Marchetti, Tosca Suprani; Santa Maria delle Croci Hospital, Ravenna, Italy: Paolo Di Bartolo; Epilepsy (E): ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo – Ospedale San Paolo, Milano: Maria Paola Canevini, Ilaria Viganò; ADHD (A): ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo – Ospedale San Paolo, Milano: Ilaria Costantino, Valeria Tessarollo; Scientific Technical Committee (CTS): Giampaolo Ruffoni. The authors would also like to acknowledge Chiara Pandolfini for language editing. Moreover, the authors thank the centers that provided their protocols: “ASST Lodi” Hospital, Lodi (Dr. Paola Morosini); “ASST Vallecamonica”, Sebino, Brescia (Dr. Francesco Rinaldi); CAMHS “ASL Liguria 5”, La Spezia (Dr. Franco Giovannoni); AMHS “Assisano Media Valle del Tevere”, Assisi (Dr. Marco Grignani); AMHS, Perugia (Dr. Marco Grignani); “ASST Rhodense”, Garbagnate Milanese (Dr. Marco Toscano); “Azienda Ulss 8 Berica”, Vicenza (Dr. Francesco Gardellin).

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- CAMHS

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

- AMHS

Adult Mental Health Services

- NICE

National Institute for Clinical Health and Excellence

Author contributions

MB conceptualized the study with the help of the TransiDEA Group; MB and AC curated methodology; RC, MG, and MZ curated resources; ER and FS wrote the original manuscript draft; ER, MB, and AC reviewed and edited the manuscript. MB supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to publish the current version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the project “Transition care between adolescent and adult services for young people with chronic health needs in Italy”, funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2019-12371228).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Since our study does not involve human subjects, an ethical approval was not required. The study is part of a wider project (“Transition care between adolescent and adult services for young people with chronic health needs in Italy”, RF-2019-12371228 ) that was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the IRCCS “Carlo Besta” Ethics Committee (ethics committee of reference for the Mario Negri IRCCS Institute) (8 September 2021, protocol n. 87). The present study represents an analysis of the content of transition protocols (i.e., a set of predetermined guidelines regulating interventions to guarantee an effective transition to adult care) adopted by child psychiatric and psychiatric services and does not involve human participants. Transition protocols have been voluntarily shared by the heads of the services involved in the study and do not contain any data concerning patients. No data concerning single individuals were analyzed. Therefore, no anonymization was necessary, and no informed consent to participate was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The article does not contain personal medical information about any identifiable living individual. No data concerning single individuals were analyzed. No explicit consent for publication was therefore required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- 2.Seixas M, Weiss M, Müller U. Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:753–65. 10.1177/0269881111412095. 10.1177/0269881111412095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roughan LA, Stafford J. Demand and capacity in an ADHD team: reducing the wait times for an ADHD assessment to 12 weeks. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000653. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000653. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reale L, Bonati M. ADHD prevalence estimates in Italian children and adolescents: a methodological issue. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44:108. 10.1186/s13052-018-0545-2. 10.1186/s13052-018-0545-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocco I, Corso B, Bonati M, Minicuci N. Time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in European children: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:575. 10.1186/s12888-021-03547-x. 10.1186/s12888-021-03547-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. 10.7189/jogh.11.04009. 10.7189/jogh.11.04009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen B, Luna B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neurosci Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018;94:179–95. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.005. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrero N, Yu X, Raphael J, O’Connor T. Impacts of racial discrimination in late adolescence on psychological distress and wellbeing outcomes in the transition to Adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72:S2. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.11.024. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintero J, Rodríguez-Quiroga A, Álvarez-Mon MÁ, Mora F, Rostain AL. Addressing the treatment and service needs of young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31:531–51. 10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.007. 10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilens TE, Isenberg BM, Kaminski TA, Lyons RM, Quintero J. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder and transitional aged youth. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:100. 10.1007/s11920-018-0968-x. 10.1007/s11920-018-0968-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young S, Murphy CM, Coghill D. Avoiding the twilight zone: recommendations for the transition of services from adolescence to adulthood for young people with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:174. 10.1186/1471-244X-11-174. 10.1186/1471-244X-11-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen AS, Telléus GK, Mohr-Jensen C, Lauritsen MB. Parent-perceived barriers to accessing services for their child’s mental health problems. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021;15:4. 10.1186/s13034-021-00357-7. 10.1186/s13034-021-00357-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Driver D, Berlacher M, Harder S, Oakman N, Warsi M, Chu ES. The Inpatient experience of emerging adults: transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Care. J Patient Experience. 2022;9:237437352211336. 10.1177/23743735221133652. 10.1177/23743735221133652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young S, Adamou M, Asherson P, Coghill D, Colley B, Gudjonsson G, et al. Recommendations for the transition of patients with ADHD from child to adult healthcare services: a consensus statement from the U.K. adult ADHD network. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:301. 10.1186/s12888-016-1013-4. 10.1186/s12888-016-1013-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swift KD, Hall CL, Marimuttu V, Redstone L, Sayal K, Hollis C. Transition to adult mental health services for young people with attention Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a qualitative analysis of their experiences. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:74. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-74. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eke H, Janssens A, Ford T, Review. Transition from children’s to adult services: a review of guidelines and protocols for young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in England. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;24:123–32. 10.1111/camh.12301. 10.1111/camh.12301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline [CG177] osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. London: National Institute for Health & Care Excellence; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers MJ, Irwin CE. Health Care transitions for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2023;151:e2022057267L. 10.1542/peds.2022-057267L. 10.1542/peds.2022-057267L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White PH, Cooley WC, Transitions clinical report authoring group, American academy of pediatrics, American academy of family physicians, American college of physicians, et al. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182587. 10.1542/peds.2018-2587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.White P, Schmidt A, Shorr J, Ilango S, Beck D, McManus M. Six core elements of health care transition™ 3.0. 2020.

- 21.Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T, Price A, Young S, Ani C, et al. Transition between child and adult services for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): findings from a British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:616–22. 10.1192/bjp.2019.131. 10.1192/bjp.2019.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Signorini G, Singh SP, Boricevic-Marsanic V, Dieleman G, Dodig-Ćurković K, Franic T, et al. Architecture and functioning of child and adolescent mental health services: a 28-country survey in Europe. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:715–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30127-X. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30127-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price A, Mitchell S, Janssens A, Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T. In transition with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): children’s services clinicians’ perspectives on the role of information in healthcare transitions for young people with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:251. 10.1186/s12888-022-03813-6. 10.1186/s12888-022-03813-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SP, Tuomainen H, de Girolamo G, Maras A, Santosh P, McNicholas F, et al. Protocol for a cohort study of adolescent mental health service users with a nested cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of managed transition in improving transitions from child to adult mental health services (the MILESTONE study). BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016055. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016055. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zadra E, Giupponi G, Migliarese G, Oliva F, Rossi PD, Francesco Gardellin, et al. Survey on centres and procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD in public services in Italy. Rivista Di Psichiatria. 2020. 10.1708/3503.34894. 10.1708/3503.34894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberti E, Scarpellini F, Campi R, Giardino M, Clavenna A, Bonati M, et al. Transitioning to adult mental health services for young people with ADHD: an Italian-based survey on practices for pediatric and adult services. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17:131. 10.1186/s13034-023-00678-9. 10.1186/s13034-023-00678-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suris J-C, Akre C. Key elements for, and indicators of, a successful transition: an International Delphi Study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:612–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.007. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn V. Young people, mental health practitioners and researchers co-produce a transition Preparation Programme to improve outcomes and experience for young people leaving Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:293. 10.1186/s12913-017-2221-4. 10.1186/s12913-017-2221-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scarpellini F, Bonati M. Transition care for adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a descriptive summary of qualitative evidence. Child. 2022;cch13070. 10.1111/cch.13070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Reale L, Costantino MA, Sequi M, Bonati M. Transition to adult mental health services for young people with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2018;22:601–8. 10.1177/1087054714560823. 10.1177/1087054714560823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulkey M, Baggett AB, Tumin D. Readiness for transition to adult health care among U.S. adolescents, 2016–2020. Child. 2023;49:321–31. 10.1111/cch.13047. 10.1111/cch.13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bray EA, Everett B, George A, Salamonson Y, Ramjan LM. Co-designed healthcare transition interventions for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44:7610–31. 10.1080/09638288.2021.1979667. 10.1080/09638288.2021.1979667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magon RK, Latheesh B, Müller U. Specialist adult ADHD clinics in East Anglia: service evaluation and audit of NICE guideline compliance. BJPsych Bull. 2015;39:136–40. 10.1192/pb.bp.113.043257. 10.1192/pb.bp.113.043257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coghill D. Services for adults with ADHD: work in progress: Commentary on … Specialist adult ADHD clinics in East Anglia. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:140–3. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.114.048850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kok-Pigge AC, Greving JP, de Groot JF, Oerbekke M, Kuijpers T, Burgers JS. A Delphi consensus checklist helped assess the need to develop rapid guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;156:1–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.02.007. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farrell ML. Transitioning adolescent mental health care services: the steps to care model. Child Adoles Psych Nurs. 2022;35:301–6. 10.1111/jcap.12377. 10.1111/jcap.12377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girela-Serrano B, Miguélez C, Porras‐Segovia AA, Díaz C, Moreno M, Peñuelas‐Calvo I, et al. Predictors of mental health service utilization as adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder transition into adulthood. Early Intervention Psych. 2023;17:252–62. 10.1111/eip.13322. 10.1111/eip.13322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.