Abstract

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an important technique for treating biliary obstruction. A case report of a 75-year-old male with diagnosed choledocholithiasis and cholangitis was presented. He had a history of hepatic surgery 45 years ago, and during the ERCP, an unusual clinical scenario was encountered. Retained extraction basket during ERCP is a rare but known complication and there are no standard recommendations to manage it. To our knowledge, this is the first case report described in the literature with retention of an extraction basket in surgical sutures at ERCP and the longest period from surgery to stone formation in the biliary system. This case report aims to emphasize that in patients with a history of hepatobiliary surgery, postoperative material can cause complications during ERCP.

Keywords: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Choledocholithiasis, Suture material, Extraction basket

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an important technique for treating both benign and malignant biliary obstructions and is generally considered effective and safe [1]. Frequent complications of ERCP include pancreatitis, bleeding, infection, and perforation, while extraction basket retention is a rare but serious one [2]. Following surgical interventions such as open cholecystectomy, choledochotomy, gastric surgery, hepatectomy, or hepaticojejunostomy, the non-absorbable sutures can migrate into the bile ducts and serve as a nidus for stone formation with consequent obstructive jaundice and/or cholangitis. Such complications can be successfully managed using ERCP [3-6]. Extraction baskets are commonly used for the extraction of common bile duct (CBD) stones larger than 1 cm, with a high percentage of success [7]. Basket retention represents an unusual and rare complication of biliary stone removal, and basket entanglement in sutures in CBD has not yet been described in the available literature. Herein we present one such clinical scenario, discuss the mechanism that could have caused it and suggest a treatment approach.

Case Report

A 75-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice, and a fever. He had no significant comorbidities, but he underwent a hepatic procedure due to a hydatid cyst in the right side of the liver 45 years ago. The cyst was removed and concurrent cholecystectomy with choledochotomy and T-tube placement were performed. The postoperative course was uneventful. Two years before the current presentation, the patient underwent ERCP due to cholangitis related to choledocholithiasis. A balloon extraction of CBD stones and subsequent plastic biliary stent placement were performed. At the time, it was advised to remove the biliary stent in 2 months, but later on, the patient did not return for follow-up.

On physical examination, there was a tenderness in the right upper abdominal quadrant, icterus and fever (38.1 °C). Laboratory tests showed a cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme results and increased inflammation markers.

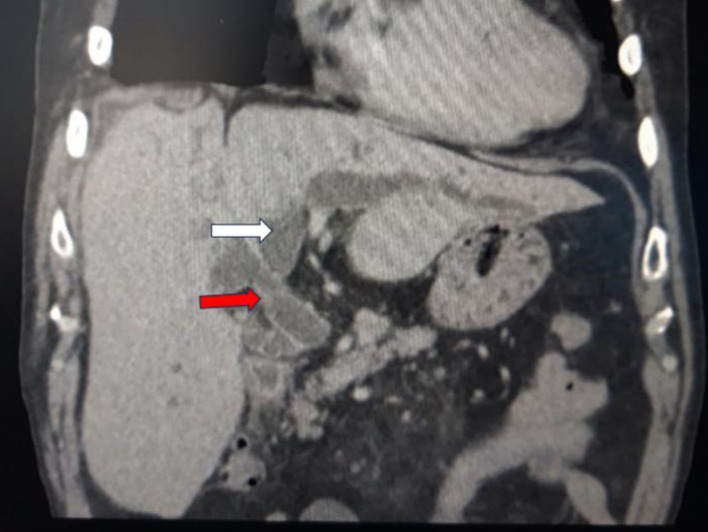

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showed dilatation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. The CBD was dilated to 20 mm with imaging evidence of an intraluminal stone (15.5 × 7.5 × 11 mm in size) and a plastic stent positioned in the distal part of the CBD (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

CECT revealing a bile duct dilatation (white arrow) with intraluminal concrement (red arrow). CECT: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy (ceftriaxone 2 g QD) with fluid resuscitation was started immediately.

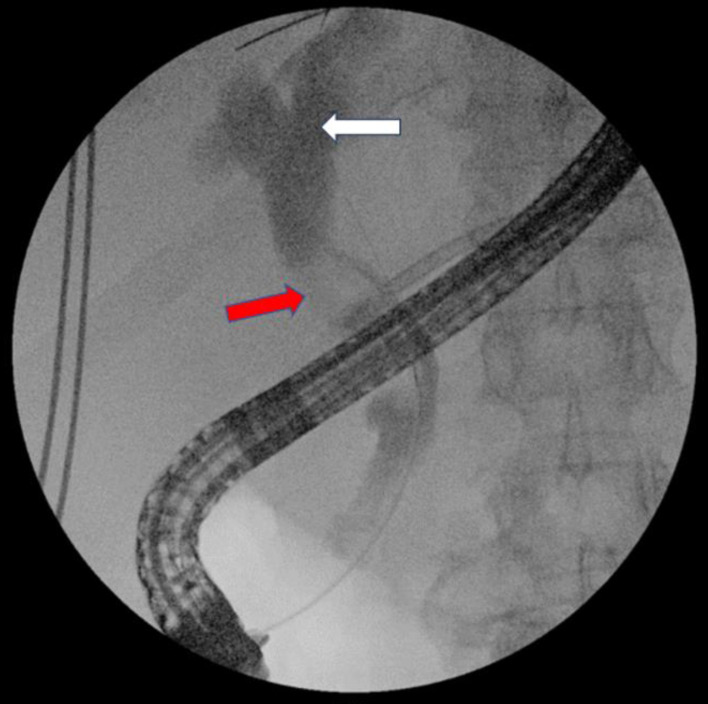

At ERCP performed the next day, the plastic biliary stent was in situ and a choledocho-duodenal fistula was seen. The stent was removed with forceps and left in the stomach until the end of the procedure. The biliary sphincterotomy was adequate. Cholangiography showed dilatation of the intra- and extra-hepatic biliary tree and a large stone in the CBD (Fig. 2). An extraction basket (Olympus; FG-V422PR) was then introduced to remove the stone. During the removal attempt, significant resistance was felt during basket withdrawal; multiple attempts failed, although the basket had been closed. The basket was tried to retrieve with an emergency Soehendra lithotripter (Olympus; BML-110A-1) (Fig. 3), but the wire broke at the patient’s mouth level. An attempt to retrieve it with a balloon catheter and a rat-tooth forceps was unsuccessful as well, so the final option was surgical management.

Figure 2.

Cholangiogram shows dilatation of intra- and extrahepatic biliary ducts (white arrow) and a large stone in CBD (red arrow). CBD: common bile duct.

Figure 3.

Retained extraction basked tried to retrieve with emergency Soehendra lithotripter.

A median laparotomy was performed, and following the choledochotomy, a biliary stone in the proximal CBD was found. The stone was removed, but the removal of the retained basket was not successful because it was firmly attached to the CBD wall. Despite a manual milking method, water irrigation and Fogarty catheter use, the basket could not be safely removed. Therefore, a duodenotomy was performed into the second part of the duodenum. The extraction basket was found in the papilla, entangled in a ball of surgical sutures (Fig. 4). The sphincterotomy was extended and all foreign material was carefully removed. The duodenum was closed and a T-tube was placed in the CBD. An abdominal drain was placed in the subhepatic area. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, crystalloid fluids, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), analgesics, and low molecular weight heparin (LWMH), and he was clinically stable, afebrile, and anicteric with normalization of liver function tests (LFTs) and inflammatory markers. The T-tube was removed on the 17th postoperative day and the patient was discharged. At the last follow-up, 12 months after surgery, the patient had no symptoms and he had normal LFTs.

Figure 4.

Surgical sutures removed from prepapillary CBD during the surgery. CBD: common bile duct.

Discussion

Non-absorbable surgical sutures in the lumen of the biliary tree usually originate from ligation of the cystic duct after cholecystectomy or CBD repair, and only rarely from other surgical interventions, such as hepatico-jejunal anastomosis, gastrectomy, and hepatectomy [3-6]. In cases of choledochotomy, the common bile duct is usually closed over the T-tube with several interrupted sutures. The main purpose of the T-tube is prevention of bile stasis and decompression of the biliary tree. In addition, it minimizes the risk of bile leakage and prevents stricture formation of the sutured CBD.

The exact mechanism of suture migration into bile ducts is not clearly understood. It is assumed that suture material can cause continuous erosions of bile ducts and migrate intraluminally. In cases of previously described T-tube placement and removal, suture migration may be triggered by inflammatory processes around the choledochotomy or by suture disruption during the removal. Once they are in the duct, the bile flow is impeded and bile salts deposit around the suture material, resulting in stone formation [6].

Here, we describe the case of CBD stone formation due to non-absorbable sutures more than 40 years after surgery. It is, to the best of our knowledge, the longest reported period from surgery to such a clinical scenario. Also, we describe an unusual and unique case of extraction basket retention within such surgical material. In this case, several factors might have contributed to suture intraluminal migration and stone formation. First, the abovementioned consequences of choledochotomy and T-tube placement and the use of non-absorbable suture probably resulted in suture migration into CBD. Over the years, it served as a nidus for stone formation and resulted in cholangitis and choledocholithiasis 2 years prior to presentation. This was treated with ERCP which could have caused further suture displacement inside the CBD. All this finally led to the unusual clinical scenario described in our article.

Extraction basket retention is a rare complication and all reported cases have been related to endoscopic extraction of biliary stones. The prevalence of this complication is 0.8% [2]. It occurs mostly when the basket cannot be extracted through papilla Vateri because of the size of the stone and when the detachment of the stone from the basket is not possible. In this situation, the next logical step is an emergency lithotripsy, which can resolve most of these situations [8]. But what if the basket lead wire breaks? This is a known, but extremely rare problem and there are no standard recommendations. It is also an emergency that requires prompt reaction to avoid biliary and intestinal injuries [9]. Various strategies are reported: surgical, non-surgical, or even conservative.

The surgical approach can be an open or a laparoscopic one. When open surgery is chosen, a choledochotomy should be attempted first to remove the basket. When this fails, as in our case, duodenotomy and extension of sphincterotomy should be the next step [2]. Laparoscopic treatment has advantages over open surgery, including lower morbidity rates, shorter hospital stays and lower cost. However, in patients who have previous hepatobiliary procedures, there are many technical challenges due to the adhesions and altered anatomy [10]. Laparoscopic CBD exploration under the control of a choledochoscope can easily identify the problem and the retained basket can be engaged with a choledochoscopic basket and pulled out [11]. In addition, the choledochoscope can be used to fragment the stones and remove them more easily [12].

Recently, numerous non-surgical methods for retrieving retained extraction baskets have been discussed. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), intracorporeal electrohydraulic shock wave, and laser lithotripsy can all be used to fragment impacted stones and retrieve retained baskets safely. However, these methods are rarely used because they require special equipment and well-trained staff; therefore, they are not available in many centers [9, 13, 14].

A percutaneous, transhepatic approach is also described. With this, intracorporeal electrohydraulic lithotripsy for stone fragmentation and subsequent basket retrieval, or using Amplatz goose-neck snare can be used [15-17].

Various endoscopic methods for retrieving retained baskets are reported. Extension of sphincterotomy is one of them. However, it can be complicated by tissue injury due to the spreading of electrical current through the wire [18]. Post-cut sphincterotomy with a needle knife can be efficient and safe in the hands of an experienced endoscopist [19]. Albert described basket retrieval by using argon plasma coagulation (APC) to cut the wires, whereupon the basket is easily removed with forceps [20]. Balloon dilation is a safe method for large CBD stone extraction, which can also be used for retrieving retained baskets with high success and should be considered as the first-line salvage treatment [21]. Another approach to this complication is the use of a second extraction basket. It is quite simple to use and does not require any additional tools other than the second basket [8]. Another simple method is grasping the extraction basket’s wires with rat-tooth forceps and thus disengaging the extraction basket from the stone [22]. A case of a plastic biliary stent placement alongside the retained basket with subsequent continuous traction on wires in the stomach is also reported. At the follow-up ERCP 2 weeks later, the wires were still in the stomach and the extraction basket had migrated into the duodenum and was easily removed with biopsy forceps [23]. Fully covered self-expandable metal stents (FCSEMS) are also used for dealing with this complication. In this case, the wires had also been left in the stomach, and after 2 weeks, when the FCSEMS was removed, the basket was easily retracted outside the papilla Vateri without any adverse events [24]. Although the aforementioned cases emphasize a strategy of observation and a follow-up ERCP after providing biliary drainage, they are rarely performed and potentially could result in serious biliary and intestinal injuries. An orthopedic instrument, an AO (ASIF) wire tightener, can be successfully used when stones are impacted along with the extraction basket [25].

All the above-mentioned salvage techniques were applied after the extraction basket had been retained together with a stone. Although the number of case reports on this subject is increasing, it still represents a quite rare and unusual complication, and standard protocols are not established. We believe that successful management of this situation depends on familiarity with such cases from the literature, previous dealing with similar complications, and endoscopist adaptability. In addition, a multidisciplinary approach and consultation with surgeons and radiologists is of paramount importance. In the case we present, the basket was retained in prepapillary CBD without apparent reason, since the basket had been closed. A more aggressive endoscopic procedure was not tried because of the risk of CBD injury. So surgical consultation was a reasonable next option. It turned out that the basket was entangled in a ball of non-absorbable surgical sutures from a hepatobiliary surgery performed 45 years ago. The sutures were probably the reason for the stone formation. A CT scan cannot detect materials such as surgical sutures especially if these are associated with stones, so the exact diagnosis could not established pre-procedure in our case. There were other unfavorable factors connected with this case. It was only the fourth ERCP performed in our hospital, and the procedure was commenced by the trainee at the beginning of his ERCP education. A senior gastroenterologist from another hospital, who supervised the procedure, took over, but also he had not seen this type of complication during his 20-year-long ERCP-performing career. In addition, our surgical team had not had experience with ERCP complications. Considering all of those factors, it was decided that open surgery with choledochotomy and duodenotomy is the best option. The stone, the sutures, and the extraction basket were successfully removed and the patient eventually recovered successfully.

Conclusions

Extraction basket retention and the lead wire break during emergency extracorporeal lithotripsy can happen even with an empty (closed) basket. If this occurs in a patient with a history of hepatobiliary surgery, postoperative suture material should be considered as a possible cause. Although different methods of retrieving retained baskets are described, one has to be very careful to avoid injuries, especially if there are unforeseen factors, such as suture material.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AB and ZP. Writing - original draft preparation: AB, ZP, IS, and VD. Supervision: IR and BB. Writing - review and editing: AA and MP. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Alatise OI, Owojuyigbe AM, Omisore AD, Ndububa DA, Aburime E, Dua KS, Asombang AW. Endoscopic management and clinical outcomes of obstructive jaundice. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2020;27(4):302–310. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_242_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu Shakra I, Bez M, Bickel A, Badran M, Merei F, Ganam S, Kassis W. et al. Emergency open surgery with a duodenotomy and successful removal of an impacted basket following a complicated endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedure: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s13256-020-02608-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Tao L, Wu X, Mou L, Sun X, Zhou J. Bile duct stone formation around a Prolene suture after cholangioenterostomy. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(1):263–266. doi: 10.12669/pjms.321.8985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda C, Yokoyama N, Otani T, Katada T, Sudo N, Ikeno Y, Matsuura F. et al. Bile duct stone formation around a nylon suture after gastrectomy: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:108. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinoshita H, Sajima S, Hashino K, Hashimoto M, Sato S, Kawabata M, Tamae T. et al. A case of intrahepatic gallstone formation around nylon suture for hepatectomy. Kurume Med J. 2000;47(3):235–237. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.47.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KH, Jang BI, Kim TN. A common bile duct stone formed by suture material after open cholecystectomy. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22(4):279–282. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binmoeller KF, Schafer TW. Endoscopic management of bile duct stones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32(2):106–118. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200102000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khawaja FI, Ahmad MM. Basketing a basket: A novel emergency rescue technique. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4(9):429–431. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i9.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhaus H, Hoffmann W, Classen M. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy with an automatic stone recognition system for basket impaction in the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1992;24(6):596–599. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori T. Comprehensive and innovative techniques for laparoscopic choledocholithotomy: A surgical guide to successfully accomplish this advanced manipulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(13):1531–1549. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varshney VK, Sreesanth KS, Gupta M, Garg PK. Laparoscopic retrieval of impacted and broken dormia basket using a novel approach. J Minim Access Surg. 2020;16(4):415–417. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_245_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien JW, Tyler R, Shaukat S, Harris AM. Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration for Retrieval of Impacted Dormia Basket following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography with Mechanical Failure: Case Report with Literature Review. Case Rep Surg. 2017;2017:5878614. doi: 10.1155/2017/5878614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attila T, May GR, Kortan P. Nonsurgical management of an impacted mechanical lithotriptor with fractured traction wires: endoscopic intracorporeal electrohydraulic shock wave lithotripsy followed by extra-endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(8):699–702. doi: 10.1155/2008/798527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauter G, Sackmann M, Holl J, Pauletzki J, Sauerbruch T, Paumgartner G. Dormia baskets impacted in the bile duct: release by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1995;27(5):384–387. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheridan J, Williams TM, Yeung E, Ho CS, Thurston W. Percutaneous transhepatic management of an impacted endoscopic basket. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39(3):444–446. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon JH, Lee JK, Lee JH, Lee YS. Percutaneous transhepatic release of an impacted lithotripter basket and its fractured traction wire using a goose-neck snare: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12(2):247–251. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halfhide BC, Boeve ER, Lameris JS. Percutaneous release of Dormia baskets impacted in the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1997;29(1):48. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekiz F, Yuksel O, Uskudar O, Yuksel I, Altinbas A, Basar O. Successful endoscopic removal of fractured basket traction wire during mechanical lithotripsy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22(2):233–234. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Zhang LP, Xu M, Zeng HZ, Zeng QS, Chen HL, Liu Q. et al. "Post-cut": An endoscopic technique for managing impacted biliary stone within an entrapped extraction basket. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2018;19(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albert JG. "Cutting the wire" as a troubleshooter for a Dormia basket impacted in the common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(2):465. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsinelos P, Fasoulas K, Beltsis A, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Terzoudis S, Kountouras J. Large-balloon dilation of the biliary orifice for the management of basket impaction: a case series of 6 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1298–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryozawa S, Iwano H, Taba K, Senyo M, Sakaida I. Successful retrieval of an impacted mechanical lithotripsy basket: a case report. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S111–S113. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maple JT, Baron TH. Biliary-basket impaction complicated by in vivo traction-wire fracture: report of a novel management approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(6):1031–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grande G, Cecinato P, Caruso A, Bertani H, Zito FP, Sassatelli R, Conigliaro R. Covered metal stent as a rescue therapy for impacted Dormia basket in the biliary tract. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30(3):305–306. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.18028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dullemen H, Stuifbergen WN, Juttmann JR, van der Werken C. Simple release of an impacted Dormia basket during endoscopic bile duct stone extraction. Endoscopy. 1993;25(5):374. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.