Abstract

Background

The activity of PARP inhibitors (PARPi) in patients with homologous recombination repair (HRR) mutations and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer has been established. We hypothesized that the benefit of PARPi can be maintained in the absence of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in an HRR-mutated population. We report the results of a phase II clinical trial of rucaparib monotherapy in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC).

Methods

This was a multi-center, single-arm phase II trial (NCT03413995) for patients with asymptomatic, mHSPC. Patients were required to have a pathogenic germline mutation in an HRR gene for eligibility. All patients received rucaparib 600 mg by mouth twice daily, without androgen deprivation. The primary endpoint was a confirmed PSA50 response rate.

Results

Twelve patients were enrolled, 7 with a BRCA1/2 mutation and 5 with a CHEK2 mutation. The confirmed PSA50 response rate to rucaparib was 41.7% (N = 5/12, 95% CI: 15.2-72.3%, one-sided P = .81 against the 50% null), which did not meet the pre-specified efficacy boundary to enroll additional patients. In patients with measurable disease, the objective response rate was 60% (N = 3/5), all with a BRCA2 mutation. The median radiographic progression-free survival on rucaparib was estimated at 12.0 months (95% CI: 8.0-NR months). The majority of adverse events were grade ≤2, and expected.

Conclusion

Rucaparib can induce clinical responses in a biomarker-selected metastatic prostate cancer population without concurrent ADT. However, the pre-specified efficacy threshold was not met, and enrolment was truncated. Although durable responses were observed in a subset of patients, further study of PARPi treatment without ADT in mHSPC is unlikely to change clinical practice.

Keywords: PARP inhibitor, homologous recombination, prostate cancer

This article reports the results of a phase II clinical trial of rucaparib monotherapy in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Implications for practice.

Poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have clinical activity in patients with advanced metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer who harbor a homologous recombination repair mutation. Prior studies in prostate cancer have administered PARP inhibitors with concomitant androgen deprivation therapy. In this study, we demonstrate preliminary clinical responses to PARP inhibition without androgen deprivation therapy in a biomarker selected population of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Although some responses were durable, single agent PARP inhibition is unlikely to supplant hormonal therapies in the treatment of metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer.

Introduction

Poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) functions in the DNA repair pathway, specifically in the base excision repair of single-stranded DNA breaks. PARP inhibition leads to chromosomal instability and cell death in tumors that harbor homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene mutations such as BRCA1 or BRCA2.1,2 This concept of “synthetic lethality” has led to the clinical development of multiple PARP inhibitors for use in several HRR-mutated cancers.3

Both germline and somatic HRR mutations have been observed in patients with prostate cancer.4,5 The presence of germline mutations in patients with prostate cancer may confer more aggressive disease and worse clinical outcomes.6-8 In addition, the incidence of germline HRR mutations is significantly higher in patients with metastatic vs localized prostate cancer, suggesting that these patients are at higher risk of developing advanced disease.8 The effect of HRR mutations on response to novel androgen receptor (AR) targeted therapies is unclear, with conflicting observations but the majority suggesting blunted sensitivity.9-11 Multiple clinical trials have shown benefit of PARP inhibitors when used as monotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).12-17 Notably, in each of these studies, patients were maintained on androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) while receiving the PARP inhibitor. Conversely, the use of PARP inhibitors without ADT has not been tested in patients with metastatic prostate cancer.

ADT is an important backbone of therapy for patients with treatment-naïve, metastatic prostate cancer. However, the morbidity of therapy may impact quality of life and lead to adverse health outcomes. Well-tolerated, non-hormonal therapies are an unmet clinical need for patients with incurable prostate cancer. We hypothesized that the efficacy of PARP inhibition will be maintained in the absence of ADT in a biomarker-selected population. Here we report the results of a single arm phase II study using rucaparib without ADT in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) who harbored a germline HRR mutation.

Methods

Study cohort, design, and outcome measures

TRIUMPH is an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved, single-arm, phase II trial that was conducted at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, MD, USA and at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York, NY, USA. Eligible patients were 18 years or older with metastatic disease as defined by one or more bone metastases confirmed by bone scintigraphy or radiographic soft-tissue metastases on CT imaging. All patients must have been ineligible for or declined ADT-based systemic treatment. Eligible patients were required to harbor a germline mutation in one or more HRR genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, CHEK2, NBN, RAD50, RAD51C, RAD51D, PALB2, MRE11, FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCI, FANCM) as documented by a clinical-grade saliva or blood-based germline genetic test. Patients with soft-tissue disease were required to undergo a baseline metastatic tumor biopsy. No prior ADT in the past 6 months before enrollment was allowed. Serum testosterone levels > 100 ng/dL, PSA ≥ 2.0 ng/mL, and adequate bone marrow, renal and liver function were required.

All patients received rucaparib 600 mg by mouth twice daily. Patients were treated until clinical or radiographic progression, unless removed from study due to treatment-related toxicity or voluntary withdrawal of consent.

The primary endpoint for this study was a confirmed PSA50 response rate defined as a ≥ 50% decline in PSA from baseline, confirmed with a second measurement at least 4 weeks later. The best PSA response was measured at any time while taking rucaparib. Secondary endpoints included objective response rate (ORR) in those with measurable disease, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS), PSA progression-free survival (PSA-PFS), and safety. The ORR was defined as the percentage of patients who achieve an objective response (complete response or partial response) by RECIST 1.1 criteria among those with measurable disease. rPFS was defined as the time from the date of the first dose to clinical or radiographic progression according to RECIST 1.1 for soft-tissue disease or PCWG3 for bone lesions. PSA-PFS was defined as the time from the date of the first dose of rucaparib to the time of PSA progression according to PCWG3 criteria (increase from PSA nadir > 25% and by > 2 ng/mL). Toxicities were assessed according to CTCAE version 5.

Statistical analysis

The null hypothesis of a PSA50 response rate was 50%. The sample size was calculated to detect an improved PSA50 response rate from 50% to 75%. An optimal Simon 2-stage design was planned and a sample size of 28 patients provided 90% power to detect an absolute 25% increase in PSA50 response rate with a one-sided type I error of 0.10. A total of 12 patients were planned to be entered in the first stage. The number of patients allowed with a non-BRCA1, -BRCA2, or –ATM mutation in stage 1 was initially planned to be capped at 3. Due to slow enrolment, we allowed 5 patients with a non-BRCA1-BRCA2-ATM mutation. If 6 or fewer subjects had a PSA50 response, then the study would be terminated for futility. If ≥ 7 subjects responded, then an additional 16 patients would be studied, for a total of 28 patients. We stopped the trial early after observing 5 out of 12 responses in the first stage. PSA50 response rate and ORRs were estimated with 95% exact confidence interval (CI) using Clopper-Pearson method. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the rPFS and PSA-PFS.

Next-generation DNA sequencing

Somatic tumor sequencing was performed through Foundation Medicine using the FoundationOne CDx platform. Testing was performed on formalin fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies from a soft-tissue metastasis. If a metastatic site was not able to be biopsied or if tumor specimen was inadequate, molecular testing was performed on archival tissue. Data on locus-specific loss of heterozygosity (LOH, expressed as a binary variable) and genome-wide LOH (gLOH, expressed as a percentage) were also determined.

Results

A total of 12 patients were enrolled on study and received at least one dose of rucaparib. All patients declined ADT and elected to participate on trial. One patient failed screening due to cancer-related pain. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Germline mutations in HRR genes were as follows: N = 6 (50%) BRCA2, N = 5 (41.7%) CHEK2, and N = 1 (8.3%) BRCA1. At the time of original diagnosis, the majority of patients had localized (N = 10; 83.3%) and high-grade disease (Gleason ≥ 9; N = 7 (58.3%)).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patient on TRIUMPH study.

| N = 12 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (Range) |

68 (49-85) |

| Baseline PSA (ng/mL) | |

| Median (Range) |

12.2 (2.0-139) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 12 (100%) |

| Other | 0 |

| Gleason sum | |

| ≤7 | 3 (25.0%) |

| 8 | 1 (8.3%) |

| 9 | 6 (50.0%) |

| 10 | 1 (8.3%) |

| Unknown | 1 (8.3%) |

| M1 at diagnosis | |

| Yes (synchronous) | 2 (16.7%) |

| No (metachronous) | 10 (83.3%) |

| Metastatic distribution | |

| Bone only | 5 (41.7%) |

| LN and bone | 3 (25.0%) |

| LN only | 2 (16.7%) |

| Prostate bed | 1 (8.3%) |

| Lung | 1 (8.3%) |

| Germline HRR mutation | |

| BRCA2 | 6 (50.0%) |

| CHEK2 | 5 (41.7%) |

| BRCA1 | 1 (8.3%) |

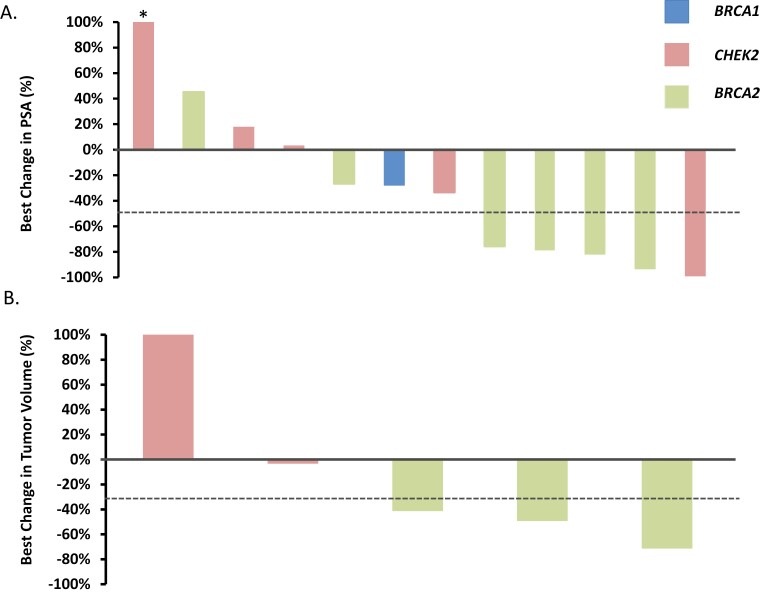

The primary endpoint of PSA50 response rate was estimated at 41.7% (95% CI: 15.2-72.3%, one-sided P = .81 against the null of 50%; Figure 1A). In those patients with a BRCA2 mutation, 4 of 6 achieved a PSA50 response (67%). One patient with a CHEK2 mutation experienced a near-complete biochemical response with a 99% decline in PSA. Five patients had measurable disease at trial entry. Three of 5 patients (60%, 95% CI: 14.7-94.7%) achieved an objective response (Figure 1B). All patients (N = 3) who harbored a germline BRCA2 mutation with measurable disease achieved a partial response.

Figure 1.

Best change in PSA level and target lesions in patients with metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer who harbored a germline HRR gene mutation and were treated with rucaparib in absence of ADT. A. Waterfall plot showing the best PSA decline from baseline for each patient (N = 12). Five of 12 patients achieved a confirmed PSA decline of 50% or greater while on treatment with rucaparib. Asterik denotes a PSA rise greater than 100% (truncated bar). B. Waterfall plot showing best change in tumor volume for 5 patients with measurable disease. An objective response was observed in 3/5 (60%) of patients, all of whom harbored a BRCA2 mutation. Mutated HRR gene is shown for each patient.

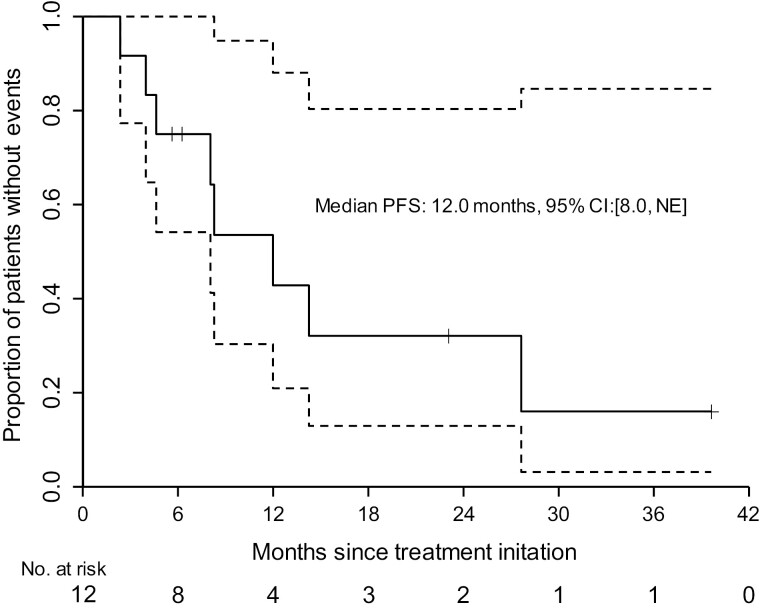

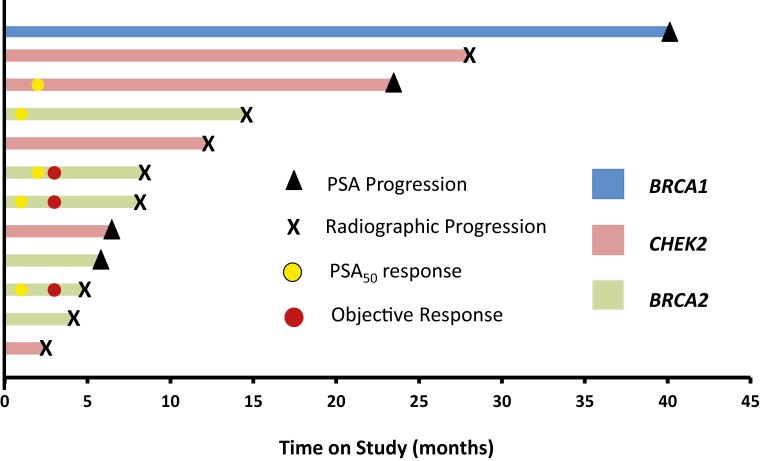

A key secondary endpoint was rPFS. We estimated a median rPFS of 12.0 months (95% CI: 8.0-not reached) (Figure 2). PSA-PFS was estimated at 11.2 months (95% CI: 3.7-not reached) (Supplementary Figure S1). Time on study is shown for each patient, depicted as a swimmer plot (Figure 3). PSA change over time for each patient is provided for reference (Supplementary Figure S2). In patients with a BRCA2 mutation, 5 of 6 (83.3%) were removed from the study for radiographic and/or PSA progression within 9 months. Three patients who remained free from radiographic progression for > 20 months harbored either a CHEK2 or BRCA1 mutation.

Figure 2.

Radiographic progression-free survival estimates for patients on the TRIUMPH Trial. Kaplan-Meier estimate of radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) is shown. The median rPFS was estimated at 12.0 months (95% confidence interval: 8.0-NE months). Dotted area represents the 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Swimmers plot of patients treated with rucaparib on the TRIUMPH trial. Duration of response is shown for each patient. Reason for study discontinuation is listed. Timing of PSA50 and or objective response is noted.

Based on the statistical Simon 2 stage design, the PSA50 response rate observed did not meet criteria for moving to the second stage. The study was thus terminated to further enrollment and patients were given the option to withdraw consent.

Treatment-related adverse events are shown (Table 2). The most common adverse events reported were fatigue (58%) and transaminitis (50%), and all were Grade ≤ 2. One Grade 3 drug-related adverse event was observed (elevated creatinine) which resolved with interruption of therapy and dose reduction of rucaparib. No deaths occurred on study.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events on TRIUMPH study.

| Adverse event | Any grade, N (%) | Grade ≥3, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 7 (58.3%) | 0 |

| Transaminitis | 6 (50.0%) | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 5 (41.7%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 5 (41.7%) | 0 |

| Creatinine elevation | 5 (41.7%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (33.3%) | 0 |

| Rash | 4 (33.3%) | 0 |

| Anemia | 3 (25.0%) | 0 |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia | 3 (25.0%) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Bilirubin elevation | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Insomnia | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Lower extremity edema | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Urinary frequency | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

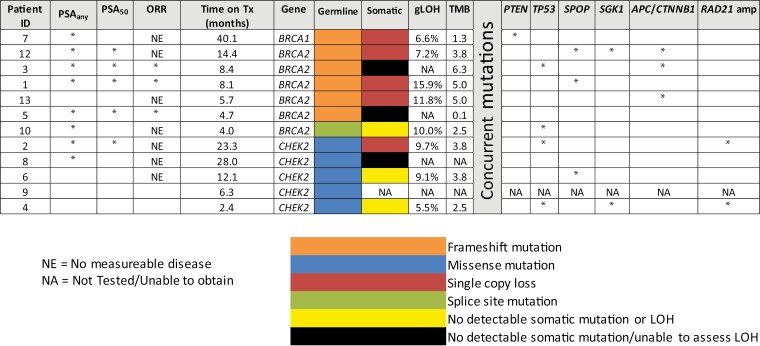

Biallelic HRR gene inactivation was observed in 5 patients (Figure 4). Four of these patients (80%) achieved some degree of PSA decline from baseline (PSAany), with 3 patients with biallelic inactivation being free from radiographic progression for > 12 months. Three patients had confirmed monoallelic (germline-only) HRR mutations without a documented somatic second hit. Two of these 3 patients experienced early disease progression, being treated on study for ≤4 months. No patients with monoallelic-only mutations achieved a PSA50 response. Concurrent somatic alterations in these patients are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Molecular characteristics and clinical responses of each TRIUMPH study patient. Molecular testing was performed on either archived tissue or a fresh biopsy specimen for each patient. Clinical responses including PSAany, PSA50 and objective responses (OR) are shown. The type of germline mutation for each HRR is listed. The “second hit” or somatic mutation is included if applicable. Other somatic co-mutations are shown for genes of interest. Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity (gLOH) percentage and tumor mutational burden (TMN) are included.

Discussion

Prior studies showing the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in patients with mCRPC demonstrated the ability to treat prostate cancer without directly targeting the traditional AR signaling pathway. This led to our hypothesis of testing these agents without concurrent ADT. We selected a population of patients whose germline mutations in an HRR gene would potentially confer the most robust response to PARP inhibition, at least theoretically. Given the near-certain clinical response to ADT in treatment-naïve metastatic prostate cancer patients, we set a high bar for the alternative hypothesis (ie, PSA50 response rate of 75%) to continue this regimen for further clinical development in mHSPC patients. In TRITON2, PSA50 response rates for patients with biallelic HRR mutations or homozygous deletions were estimated at 75% and 81%, respectively, suggesting that our alternative hypothesis was appropriate.15 However, we did not observe enough PSA50 responses in the first part of our 2-stage design to justify enrolling additional patients, and the trial was terminated prematurely for futility.

Two key observations may potentially explain why more patients did not achieve a PSA50 or objective response. 1. Lack of second-hit somatic alterations or single-copy inactivation in the cohort. Three patients in the cohort did not have biallelic inactivation or a second somatic mutation. None of these 3 patients experienced a PSA50 response. Three additional patients did not have a documented inactivating somatic mutation, and allele-specific LOH was unable to be assessed. It is thus possible that half of our patients did not have biallelic inactivation, despite harboring a germline HRR mutation. This could be due to inability to detect the second hit, or due to a true absence of a second hit implying a sporadic cancer that happened to occur in a germline mutation carrier. 2. Cohort enriched for non-BRCA1/2 mutated patients. Five of the 12 patients on study had an underlying germline mutation in CHEK2. Clinical responses to PARP inhibitors in patients harboring a CHEK2 mutation are less common than in BRCA-mutated prostate cancer.18 Four of the 6 patients with a germline BRCA2 mutation had PSA declines of greater than 50% while on rucaparib whereas only 1 in 5 PSA50 responses were observed in the CHEK2 cohort. Thus, the high number of CHEK2 patients may have negatively impacted the overall response rates. 3. Small sample size. A weakness of this study is the small number of patients enrolled, which makes it difficult to accurately estimate the true PSA50 response rate in this study. We stopped the trial early according to statistical design, as was appropriate because these patients had agreed to defer ADT and additional proven systemic agents.

Despite not meeting the primary endpoint of the study, we did observe PSA responses on trial including 67% of patients experiencing a decline in PSA upon starting rucaparib. This is the first trial showing clinical activity using PARP inhibition in patients with metastatic prostate cancer in the absence of ADT. In addition, we observed a median rPFS of 12 months in patients receiving rucaparib. This result is comparable to the median rPFS observed with rucaparib in patients with mCRPC in both TRITON2 and TRITON3 (9.0 and 11.2 months, respectively).15,16 A second study performed by our group examined the use of a different PARP inhibitor, olaparib (again without ADT), in 51 patients with high-risk M0 biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy.19 In that recent study, the PSA50 response rate in the overall HRR-mutated population was 48%, while the PSA50 response rate in the 11 patients with BRCA2 mutations was 100%. Moreover, metastasis-free survival in that trial (using olaparib, in the absence of ADT) was 3.5 years in the HRR-mutated group and only 1.4 years in the HRR wild-type group. Taken together, these findings from our 2 trials of PARP inhibition as a hormone-sparing approach to M0 and M1 HSPC, respectively, suggest that targeting AR may not be required for PSA or objective responses in the context of HRR (and especially BRCA2) mutations. Moreover, some responses to PARP inhibition without ADT may be durable in both the M0 and M1 HSPC settings, affording some patients the option of deferring hormonal therapies.

Several studies have suggested a synergistic relationship between inhibition of AR and PARP inhibitors especially in patients with HRR alterations and particularly in those with BRCA1/2 mutations.20,21 In the TRIUMPH study, we demonstrated that PARP inhibition alone was sufficient to induce both PSA and objective responses in a subset of biomarker-selected patients with metastatic prostate cancer. However, several randomized phase III trials have shown benefit of combined novel AR targeted therapy with PARP inhibition in patients with mCRPC most notably in HRR mutated patients.22-24 The combination of novel AR targeted therapies with PARP inhibition is now an FDA approved option for HRR mutated mCRPC. Furthermore, several trials (AMPLITUDE, TALAPRO-3, and EVOPAR) are currently underway to investigate ADT in combination with novel AR targeted therapy plus PARP inhibition in patients with HRR-mutated mHSPC. Despite showing proof of principle in the TRIUMPH study, the use of PARP inhibition alone as a first-line treatment of mHSPC is unlikely to supplant an ADT-based treatment paradigm for treatment naïve patients with mHSPC.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at The Oncologist online.

Funding

The project described was supported by the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins NIH grant P30 CA006973. Funding for the clinical trial was provided by Clovis Oncology.

Contributor Information

Mark C Markowski, Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Cora N Sternberg, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center, Weill Cornell, New York, NY, United States.

Hao Wang, Division of Quantitative Sciences, Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Tingchang Wang, Division of Quantitative Sciences, Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Laura Linville, Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Catherine H Marshall, Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Rana Sullivan, Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Serina King, Department of Oncology, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Tamara L Lotan, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Emmanuel S Antonarakis, Department of Medicine, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN, United States.

Author contributions

Mark Markowski (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Cora N. Sternberg (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Project administration; Writing—review & editing), Hao Wang (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Tingchang Wang (Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Laura Linville (Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing—review & editing), Catherine H. Marshall (Investigation; Writing—review & editing), Rana Sullivan (Conceptualization; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; Writing—review & editing), Serina King (Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Project administration), Tamara L. Lotan (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—review & editing), Emmanuel S. Antonarakis (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing)

Conflicts of interest

M.C.M. is paid to consultant to Clovis Oncology and Exelixis. C.N.S. is a paid consultant to Pfizer, Merck Ga, MSD, AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, Sanofi-Genzyme, Roche/Genentech, Gilead, Amgen, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Seattle Genetics, UroToday. E.S.A. has served as a paid consultant/advisor for Sanofi, Dendreon, Janssen Biotech, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Lilly, Bayer, and has received honoraria from Sanofi, Dendreon, Janssen Biotech, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Clovis Oncology; has received research funding from Janssen Biotech, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Dendreon, Genentech, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, and Constellation Pharmaceuticals, as well as travel accommodations from Sanofi, and Dendreon; He is a co-inventor of a biomarker technology licensed to Qiagen. C.H.M. reports personal fees from Tempus, Astellas, Bayer, Dendreon, Obseva.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Prior presentation of work

Previously presented as an abstract, Poster Session A: Prostate Cancer, at the 2023 ASCO GU Cancers Symposium. 2023.

References

- 1. Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434(7035):917-921. 10.1038/nature03445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123-134. 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iglehart JD, Silver DP.. Synthetic lethality--a new direction in cancer-drug development. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):189-191. 10.1056/NEJMe0903044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163(4):1011-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161(5):1215-1228. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castro E, Goh C, Olmos D, et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(14):1748-1757. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olmos D, Lorente D, Alameda D, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients with and without somatic or germline alterations in homologous recombination repair genes. Annal Oncol 2024;35(5):458-472. 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):443-453. 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mateo J, Cheng HH, Beltran H, et al. Clinical outcome of prostate cancer patients with germline DNA repair mutations: retrospective analysis from an international study. Eur Urol. 2018;73(5):687-693. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Germline DNA-repair gene mutations and outcomes in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving first-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. Eur Urol. 2018;74(2):218-225. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Annala M, Struss WJ, Warner EW, et al. Treatment outcomes and tumor loss of heterozygosity in germline DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;72(1):34-42. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mateo J, Porta N, Bianchini D, et al. Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(1):162-174. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30684-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22): 2091-2102. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abida W, Patnaik A, Campbell D, et al. ; TRITON2 Investigators. Rucaparib in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration. J Clin Oncol 2020;38(32):3763-3772. 10.1200/JCO.20.01035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fizazi K, Piulats JM, Reaume MN, et al. ; TRITON3 Investigators. Rucaparib or physician’s choice in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(8):719-732. 10.1056/NEJMoa2214676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Bono JS, Mehra N, Scagliotti GV, et al. Talazoparib monotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair alterations (TALAPRO-1): an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(9):1250-1264. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00376-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abida W, Campbell D, Patnaik A, et al. Rucaparib for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer associated with a DNA damage repair gene alteration: final results from the phase 2 TRITON2 study. Eur Urol. 2023;84(3):321-330. 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marshall CH, Teply BA, Lim SJ, et al. Phase 2 study of olaparib (without ADT) in men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer (BCR) after prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16_suppl):5087. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gui B, Gui F, Takai T, et al. Selective targeting of PARP-2 inhibits androgen receptor signaling and prostate cancer growth through disruption of FOXA1 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(29):14573-14582. 10.1073/pnas.1908547116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Asim M, Tarish F, Zecchini HI, et al. Synthetic lethality between androgen receptor signalling and the PARP pathway in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):374. 10.1038/s41467-017-00393-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chi KN, Rathkopf D, Smith MR, et al. ; MAGNITUDE Principal Investigators. Niraparib and abiraterone acetate for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2023;41(18): 3339-3351. 10.1200/JCO.22.01649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saad F, Clarke NW, Oya M, et al. Olaparib plus abiraterone versus placebo plus abiraterone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (PROpel): final prespecified overall survival results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(10):1094-1108. 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00382-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Agarwal N, Azad AA, Carles J, et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10398):291-303. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01055-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.