Abstract

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the deadliest malignancy of the female reproductive system. The standard first-line therapy for OC involves cytoreductive surgical debulking followed by chemotherapy based on platinum and paclitaxel. Despite these treatments, there remains a high rate of tumor recurrence and resistance to platinum. Recent studies have highlighted the potential anti-tumor properties of metformin (met), a traditional diabetes drug. In our study, we investigated the impact of met on the anticancer activities of cisplatin (cDDP) both in vitro and in vivo. Our findings revealed that combining met with cisplatin significantly reduced apoptosis in OC cells, decreased DNA damage, and induced resistance to cDDP. Furthermore, our mechanistic study indicated that the resistance induced by met is primarily driven by the inhibition of the ATM/CHK2 pathway and the upregulation of the Rad51 protein. Using an ATM inhibitor, KU55933, effectively reversed the cisplatin resistance phenotype. In conclusion, our results suggest that met can antagonize the effects of cDDP in specific types of OC cells, leading to a reduction in the chemotherapeutic efficacy of cDDP.

Keywords: Metformin, Cisplatin resistance, Ovarian cancer, ATM/CHK2, Rad51

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the eighth most common cause of cancer death and the leading cause of death from gynecological malignancies worldwide, the onset of ovarian cancer is insidious and often diagnosed at advanced stages, with the five-year survival rates below 45 % [1,2]. In advanced stage (stage III and IV) disease, 5-year overall survival rates decline sharply to approximately 30 % [3]. The standard treatment protocol for advanced OC involves cytoreductive surgery combined with platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy [4,5]. Resistance to chemotherapy, exacerbated by repeated chemotherapy cycles, is a significant cause of mortality in OC patients [2]. Chemotherapy-resistant OC has a very poor prognosis and lacks effective treatments, presenting a critical clinical challenge that urgently needs addressing [6].

Cisplatin (cDDP) induces the formation of DNA cross-links, which are subsequently converted by the cellular machinery into nuclear DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [7,8], and it enhances DNA damage during the DNA homologous recombination repair (HRR) process, thereby diminishing DNA repair capabilities and inhibiting the progression of OC [9]. OC cells evade cDDP-induced cell death through various mechanisms, including the cell metabolism pathway, oxidative stress pathway, and cell cycle regulation pathway. Additionally, they employ HRR and homologous DNA templates to repair DNA damage caused by cDDP. The DNA repair function in OC cells remains continuously active, leading to the development of cDDP resistance [10]. Other drugs, such as paclitaxel, are used in combination treatments for cDDP-resistant OC, but their effectiveness is limited [11]. Recently developed targeted drugs for OC are costly and not affordable for all patients [12]. Combining cDDP-based chemotherapy with other effective drugs is an alternative worth considering. However, the efficacy of combined therapies against cDDP resistance necessitates a thorough and detailed assessment due to their variable results and substantial impact on treatment effectiveness.

Metformin (met) is a first-line classic drug for treating type Ⅱ diabetes and has demonstrated antineoplastic effects in epidemiological and laboratory studies [13,14]. Met alone can significantly reduce the number of cancer stem cells in OC tissue and inhibit the growth and metastasis of OC cells [15,16] However, the impact of met combined with cDDP on OC therapy remains unclear. Some studies have shown that met not only enhances the therapeutic effects of cDDP on certain tumors, such as locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and osteosarcoma [[17], [18], [19]], but also mitigates adverse side effects of cDDP, including acute renal injury, cognitive impairment, and brain damage [20,21]. Conversely, other studies have suggested that met promote cDDP resistance in gastric cancer and antagonize the cytotoxicity of cisplatin towards various cancer cell lines such as U251 human glioma, C6 rat glioma, SHSY5Y human neuroblastoma, L929 mouse fibrosarcoma, and HL-60 human leukemia [22,23]. There has also been retrospective data supporting combination of metformin, digoxin, simvastatin as reasonable directions for anticancer therapy. In this work, cDDP was not identified as affecting benefit or resistance in combination with chemotherapy although combination with taxanes or gemcitabine was shown to be improve response when in combination with metformin and/or combined therapies of digoxin, simvastatin and metformin [24]. This study aims to explore the effects of met combined with cDDP on the chemotherapeutic efficacy of OC and its molecular mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Cell culture

The cDDP-resistant OC cell line (C13*) was gifted from Professor Benjamin K. Tsang in the Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada [25]. The human OC cell line A2780 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in Macoy'5A medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2.

2.2. Reagents

The met (S1741) and KU55933(SC9136) were bought from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China), cDDP (232120) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.3. Western blot

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described [26]. The primary mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:1,000, ab8226), anti-Gapdh (1:1,000, ab8245), anti-p-CHK2 (phospho T383, ab59408, 1:1,000) and rabbit monoclonal anti-Bcl2(1:2,000, ab182858), anti-p-ampk (1:1,000, ab133448), anti-p-mTOR (phospho S2448, 1:2,000, ab109268), anti-p-ATM (phospho S1981, 1:1,000, ab315019) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The primary rabbit monoclonal anti-c-caspase-3 antibody (1:1,000) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). The primary rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved-PARP (1:1,000) and anti-Rad51 (1:1,000) was purchased from Epitomics Corp (Burlingame, CA, USA). Mouse monoclonal anti-γ-H2AX (Ser139) antibody (1:800) was purchased from Millipore Corp (USA).

2.4. Immunohistochemical staining and analysis

Immunohistochemical staining was performed according to standard procedures. The tissues were stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody (1:200, ab15580, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rad51 antibody (1:100, Epitomics Corp), rabbit monoclonal anti-p-ATM (phospho S1981, 1:200, ab315019, Abcam,), mouse monoclonal anti-p-CHK2 (1:200, ab59408, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-c-caspase-3 antibody (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4℃. We treated the negative controls as the same way without the primary antibody. Finally, only the staining of Ki-67, Rad51, p-ATM, p-CHK2, and c-Caspase3 in tumor cells was regarded as positive. The results for the protein level were counted by the staining score, as the score were measured based on the percentage of positively stained cells (score 0, no positive cell; score 1, ≤10 % positive cells; score 2, 11 %-25 % positive cells; score 3, 26 %-50 % positive cells; and score 4, ≥51 % positive cells) and staining intensity (scores 0 and 1 were categorized as low expression, and scores 2, 3 and 4 were categorized as high expression). All score was determined separately by two independent experts simultaneously under the same conditions.

2.5. Immunofluorescence (IF) for functional HR

Rad51/γ-H2AX IF was used as a functional HR assay because one γ-H2AX focus corresponds to one DSB, and nuclear Rad51 foci formation is a marker of functional HR [6]. The IF for functional HR was performed as previously described [27]. Briefly, mouse monoclonal anti-γ-H2AX (Ser139) antibody (1:800, Millipore Corp) and rabbit monoclonal anti-Rad51 (1:100, Epitomics Corp) were incubated at 4℃ overnight, followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC or CY3. Images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus). The signal intensity of foci per cell was calculated by subtracting the mean signal in untreated nuclei. γ-H2AX and Rad51 foci were quantified in at least 50 nuclei from three different fields of each coverslip using Image J.

2.6. Alkaline single-cell agarose gel electrophoresis (COMET) assays

Alkaline comet assays were performed with the Trevigen's Comet Assay Kit as described in the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cell suspensions were embedded in LMAgarose and deposited on comet slides. The slides were incubated 1h at 4°C in lysis solution, followed by immersing slides in freshly prepared lkaline unwinding solution (pH > 13) for 20 min at RT in the dark. Electrophoresis was carried out for 30 min at 21 V in electrophoresis solution (pH > 13). Slides were then stained with SYBR Green I. DNA strand breakage was expressed as “comet tail moment”. Tail moment was measured for 100 cells per sample at least and average damage remaining of at least 3 independent experiments was calculated. Tail DNA content was analysed with Cometscore1.5 software.

2.7. Animal experiments

4-6-weeks female nude BALB/c mice, which from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. were housed and maintained in laminar flow cabinets under specific pathogen-free condition. C13* cells (5×106) were resuspended in 50 μL of phosphate-buffered saline and were injected into the mice via intraperitoneal. One week after tumor cell injection, mice were randomly separated into treatment groups. Firstly, we treated the mice as the following:(a) cDDP, n=5; (b) met + cDDP, n=5. For KU55933 treatment, we treated the mice as the following: (a) met + cDDP, n=5; (b) met+cDDP+KU55933, n=5. met (20 mg/kg, dissolved in physiological saline) was given intraperitoneally daily for 28 consecutive days; cDDP (5 mg/kg, dissolved in physiological saline) was given intraperitoneally every 4 days for 28 days; KU-55933 or excipient (10 % dimethyl sulfoxide saline) 5 mg/kg was given 30 min min before cDDP injection and 1, 2, 4, 7 and 14 days after cDDP injection. Tumor xenografts each group were collected at the end point.

2.8. Apoptosis assay

Cells were collected using 0.25 % trypsin and subsequently washed with PBS. After centrifugation, the cells underwent fixation in 80 % ice-cold ethanol and were maintained at -20°C overnight. Subsequently, they were treated with 500 μL of buffer containing 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 20 μg/mL RNase, and incubated for 30 min min. The apoptotic cells were analysed using a FAC-Scan flow cytometer, and the results were processed with Cell Fit software. This experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.9. Statistical analysis

SPSS 22 (SPSS Science Inc., Chicago, Illinois), Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) were used to perform data analysis. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. The means were calculated at least from three independent experiments. Student's two-tailed t-test was used to compare the mean values of two groups as applicable, data were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for studies involving more than two groups Statistical significance was designated at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Met combined with cDDP led to a reduction in apoptosis in C13* and A2780 cells

Initially, we assessed the apoptosis of C13* and A2780 cells after treatment with either met, cDDP, or their combination. Flow cytometry results indicated that both met and cDDP alone significantly increased apoptosis in C13* and A2780 cells (Fig. 1A, P<0.05). However, when met and cDDP were combined, the apoptosis in these cells was reduced (Fig. 1A, P<0.05). Furthermore, the results were consistent regardless of whether the cells were pre-treated with met or cDDP, indicating that the order of administration did not impact the experimental outcomes. (Fig. 1B, P<0.05).

Fig. 1.

Effects of met and cDDP alone or both on apoptosis of C13* and A2780 cells. (A) C13* cell. met, 10 μM; cDDP, 100 μM. (B) A2780 cells. met, 10 μM; cDDP, 50 μM. After the two kinds of cells were treated for 48 hours, the apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. control. Con, control; met, metformin; cDDP, cisplatin.

3.2. Met combined with cDDP alleviated the cDDP-induced injury in OC cells and induced resistance to cDDP

We assessed apoptosis and the expression of DNA damage-related genes in A2780 and C13* cells after exposure to met alone or in combination with cDDP. Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 are critical regulators of apoptosis [28,29], γ-H2AX is one of the markers for DSBs [30], while Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and Rad51 are critical DNA repair enzymes [31,32]. Additionally, ampk and mTOR are closely associated with the progression of OC [33,34]. In A2780, met alone did not significantly affect the protein levels of cleaved Caspase-3 (c-Caspase3), Bcl-2, γ-H2AX, or phosphorylated PARP (p-PARP). However, it upregulated Rad51 and phosphorylated ampk (p-ampk) protein levels while decreasing phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) levels. The combination of met and cDDP significantly decreased the protein level of the c-Caspase3 and γ-H2AX caused by cDDP (Fig. 2A). In the C13* cell, met alone did not change the protein levels of c-Caspase3, Bcl-2, and p-PARP, but it increased γ-H2AX protein expression. When treated with met combined with cDDP, or pre-treated with met for 12 hours followed by cDDP for 48 hours, the protein expression of c-Caspase3/Bcl-2 and DNA damage-related genes, including γ-H2AX, decreased, while Rad51 protein expression increased (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we assessed Rad51 protein expression in C13* cells treated with met combined with cDDP using IF. The results indicated that met alone reduced Rad51 protein expression, while met combined with cDDP lessened the inhibitory effect of cDDP on Rad51 protein expression (Fig. 2C). The comet assay showed that met combined with cDDP reduced the DNA DSBs induced by cDDP (Fig. 2D). In conclusion, these findings suggested that met combined with cDDP reduced apoptosis and DNA damage induced by cDDP, lessened the cytotoxicity of cDDP in A2780 and C13* cells, and led to cisplatin resistance, possibly due to an increase in Rad51 levels. The sequence of met administration did not affect its impact on cDDP.

Fig. 2.

Met alleviated the injury of OC cells induced by cDDP. (A-B) The level of DNA damage protein was detected by met combined with cDDP and met alone in A2780 and C13* cells. (C) IF showed the expression and localization of DNA damage protein in C13* cells, scale bars = 20 μm. (D) Comet assay, scale bars = 5 μm. **P<0.01 vs. control. Con, control; met, metformin; cDDP, cisplatin.

3.3. Met contributed to drug resistance in OC cells against cDDP by affecting the ATM/CHK2 pathway

To explore the mechanism of cDDP resistance in OC induced by met, we further investigated how tumor cells respond to the combination of met and cDDP. ATM is a critical component of the cell's response to DNA damage, particularly in the case of DSBs [35]. When cancer cells encounter DSB, ATM kinases become activated and phosphorylate CHK2, which then plays a role in the cell's response to DSBs [36]. Therefore, we also observed the effect of met combined with cDDP on the ATM/CHK2 pathway. The results indicated that met increased the expression levels of phosphorylated ATM (p-ATM) and phosphorylated CHK2 (p-CHK2) proteins, while the combination of met with cDDP reduced their expression (Fig. 3A,B). The same trend was observed in C13* cells as well (Fig. 3C). Importantly, pre-treatment and simultaneous treatment did not affect the final outcome of the experiment (Fig. 3D). These findings suggested that met combined with cDDP diminished the sensitivity of OC cells to cDDP through modulation of the ATM/CHK2 pathway, contributing to drug resistance in OC cells against cDDP.

Fig. 3.

Met affected the sensitivity of OC cells to cDDP through the ATM/CHK2 pathway. (A) The A2780 cells were treated with met and cDDP or met alone. (B) The A2780 cells were treated with met alone. (C) The C13* cells were treated with met and cDDP or met alone. (D) The cells were treated with met for 24 hours and then combined with cDDP for 24 hours.

3.4. Met alleviated the inhibitory effect of cDDP on tumor growth

To further investigate the impact of combining met with cDDP on tumor development, we established a C13* tumor-bearing mouse model in vivo and treated it with either cDDP alone or a combination of met and cDDP. Our findings revealed that the combination of met and cDDP led to a significant increase in both tumor volume and weight compared to met alone (Fig. 4A-B, P<0.05). Additionally, the combination treatment upregulated the expression levels of Ki-67 and Rad51 proteins, while significantly reducing the levels of c-Caspase3, p-ATM, and p-CHK2 proteins (Fig. 4C). These results suggested that met weakened the inhibitory effect of cDDP on tumor growth, promoted proliferation, and inhibited apoptosis in OC tissues. Moreover, it mitigated DNA damage induced by cDDP by decreasing ATM/CHK2 protein levels and enhanced the repair of DNA damage caused by cDDP through the upregulation of Rad51 protein expression. Consequently, these led to cDDP resistance in OC.

Fig. 4.

Met reduced the inhibitory effect of cDDP on tumor growth. (A) The tumor volume. (B) The tumor weight. C The protein levels of Ki-67, Caspase3, Rad51, p-ATM, and p-CHK2 (×100) were detected by IHC. cDDP, n = 5 (Unfortunately, one of them died during administration); met + cDDP, n = 5. Mean ± SEM. *P<0.05.

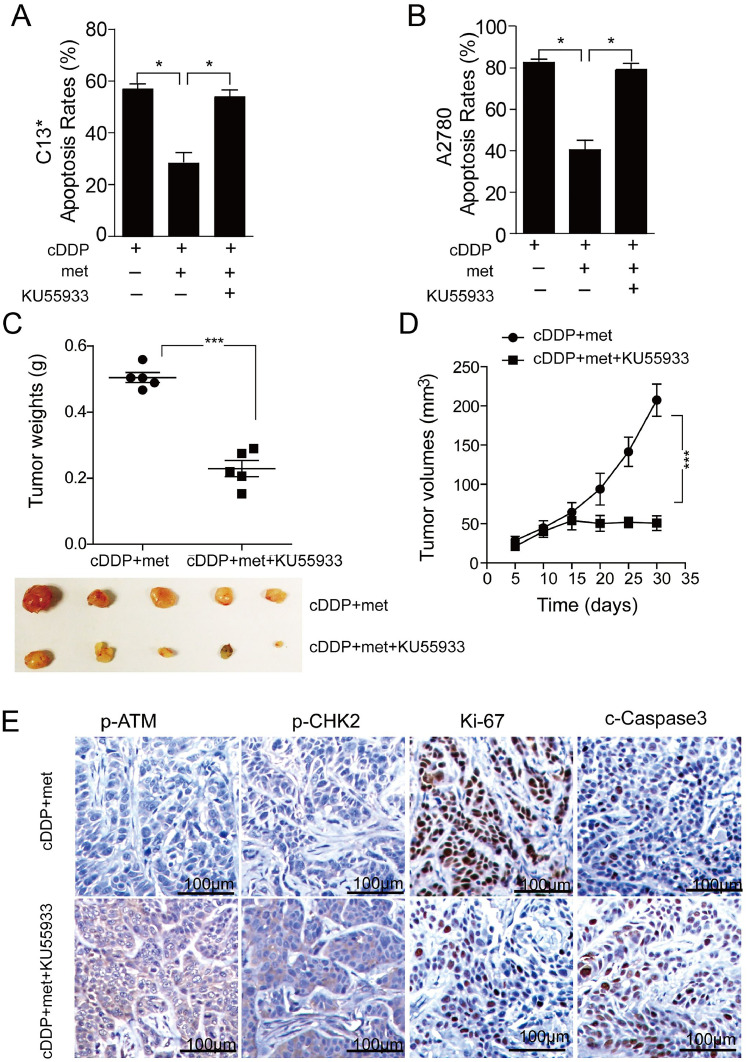

3.5. ATM blocker ATMi-KU55933 reversed drug resistance of OC cells induced by met combined with cDDP

The aforementioned results demonstrated that met weakened the anti-tumor effect of cDDP both in vivo and in vitro, and this effect was associated with the ATM-CHK2 pathway. To further investigate this phenomenon, we conducted ATM blocking using KU55933 in C13* and A2780 cells, respectively, and observed the resulting cell apoptosis. The findings revealed that the inhibitory effect of met on apoptosis induced by cDDP was reversed upon administration of KU55933 (Fig. 5A-B, P<0.05). Furthermore, we established a mouse model treated with met in combination with cDDP and administered KU55933. In this model, the tumor weight and volume of mice treated with KU55933 decreased significantly (Fig. 5C-E, P<0.01), accompanied by a decrease in the protein levels of p-ATM, p-CHK2, and Ki-67, while an increase in c-Caspase3 (Fig. 5F). These results indicated that after administration of KU55933, the therapeutic effect of met combined with cDDP for OC treatment was significantly reversed, leading to increased apoptosis of OC cells. These findings further supported the involvement of the ATM/CHK2 pathway in the drug resistance of OC cells induced by the combination treatment. Moreover, intervention with ATM/CHK2 pathway could reverse the cDDP-resistance induced by the combination treatment.

Fig. 5.

KU55933 reversed the drug resistance induced by met and cDDP. (A) The apoptosis of C13* cells; (B) The apoptosis of A2780 cells. (C-D) The tumor weight and volume after ATM were interfered with in vitro. (E) The level and localization of p-ATM and p-CHK2, Ki-67, and c-Caspase3 proteins were detected by IHC after met combined with cDDP group and KU55933 plus the combination group (×100). Mean ± SEM, n = 5. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. met, metformin; cDDP, cisplatin.

4. Discussions

Met, a well-established medication for treating type II diabetes for over half a century, has demonstrated its utility in managing various conditions, including polycystic ovary syndrome, steatohepatitis, and cardiovascular disease, among others [37]. In OC, met alone has displayed the ability to impede the proliferation of drug-resistant OC cell lines such as A2780, CP70, C200, OV202, OVCAR3, SKVO3ip, PE01 and PE04 [16]. Our study further substantiated the beneficial impact of met alone in OC treatment by inducing apoptosis in drug-resistant OC cells C13* and A2780, underscoring its direct cytotoxic effect on these cells.

When combined with cDDP, previous studies have found that met usually has a synergistic effect with cDDP. In OC cell lines OVCAR-3 and OVCAR-4, met activated the ampk signal pathway and inhibit the mTOR pathway, thereby restraining their proliferation [38]. However, in other OC cell lines such as C13* and A2780 cells, our study demonstrated a reduction in γ-H2AX levels when met was combined with cDDP, indicating a decrease in DNA DSBs. This suggested that met increased the cDDP resistance of C13* and A2780 cells, meaning it reduced the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. A similar phenomenon had also been observed that met enhanced the sensitivity of the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 to chemotherapeutic drugs but had the opposite effect in SKBR3 [39]. Additionally, met-induced ampk activation promoted cisplatin resistance through PINK1/Parkin dependent mitophagy in gastric cancer [22]. Based on the data available in the literature and our findings, we found for the first time that not all types of OC cell lines were sensitive to met combined with chemotherapy drugs such as cDDP, and met did not necessarily work synergistically with chemotherapy for all tumors. This suggests that when using Met, a traditional medicine, for new applications such as treating ovarian cancer, it is necessary to proceed with caution.

In response to DNA-damaging agents, cells activate cell cycle checkpoints and a complex response network. ATM plays a critical role in the DNA damage response (DDR) process, primarily responding to DSBs and initiating downstream pathways activation through phosphorylation of target proteins at the site of DNA, including CHK2 [40]. When cDDP induced DDR in OC cells, drug-resistant OC cells activated the ATM/CHK2 pathway in response to DDR. Previous studies have shown that met alone could activate the ATM/CHK2 pathway in different cancer cells, inhibiting proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer cells and esophageal cancer cells [41,42]. Our results also demonstrated that met alone activated the ATM/CHK2 pathway in OC cells. In contrast, the combination of met and cDDP reduced the activation of the ATM/CHK2 pathway, indicating that met reduced the DDR induced by cDDP. Rad51 also participates in DNA damage repair. A high level of Rad51 is associated with an increased DNA recombination rate and enhanced resistance to DNA damage caused by chemotherapy [43]. OC exhibits a high level of the Rad51 gene, and its increase often indicates a poor prognosis of OC and resistance to cisplatin and other chemotherapeutic drugs [44]. Previous studies have found that artesunate could make OC cells sensitive to cDDP by down-regulating Rad51 [45]. In current study, when met was combined with cDDP, the level of the Rad51 protein expression increased. Rad51 was an important factor contributing to the increased DNA damage repair in OC cells induced by met combined with cDDP, leading to cDDP resistance.

Met has been widely used, and its safety and tolerability in the management of diabetes have been fully verified for diabetic patients. Studies have indicated that type Ⅱ diabetes is associated with an increased risk of liver cancer, pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, and bladder cancer [46]. Met is an independent protective factor against cancer risk in patients with type Ⅱ diabetes [47]. Furthermore, some studies suggest that in diabetic patients, the use of met reduces the risk of certain cancers and all-cause mortality, and it is associated with significant improvement in the prognosis of colon cancer and increases the survival rates of lung cancer [[48], [49], [50]]. However, these data are not fully supported. Randomized trials of met in the treatment of type Ⅱ diabetes and as an adjunctive therapy for various cancers (advanced or metastatic) have not found a reduction in cancer incidence or outcomes [51,52]. For instance, in breast cancer, met does not reduce the risk of breast cancer in diabetic patients [53]. Moreover, it has been found that met promotes the survival of dormant ER (+) breast cancer cells by activating the AMPK pathway [54]. In this study, the combined use of met and cDDP also showed suboptimal results. This suggests that the use of met in diabetic cancer patients pose risks. Therefore, more large-scale, long-term clinical trials are needed to verify the specific efficacy and safety of met in diabetic cancer patients.

Overall, the combination of met and cDDP induced chemo-resistance in OC cells, particularly in C13* and A2780 cell lines. The effect might be attributed to two mechanisms. Firstly, it reduced the occurrence of DSB in OC cells induced by cDDP through the ATM/CHK2 pathway. Secondly, it increased the repair of DSB in OC cells by the upregulation of Rad51 protein expression (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The synergistic effect of the two mechanisms led to cDDP-resistance in OC cells induced by met combined with cisplatin.

In the present study, we first demonstrated in A2780 and C13* cell lines that met alone increased apoptosis, but when combined with cDDP, it led to a decrease in apoptosis. Furthermore, we found that met combined with cDDP reduced the injury of OC cells induced by cDDP, decreased cell apoptosis and increased proliferation of OC cells. It reduced DNA damage of OC cells by inhibiting the ATM/CHK2 pathway, increased DNA damage and repair by increasing Rad51 protein expression, and ultimately mediated cDDP resistance in OC cells. These findings enhanced our understanding of met combined with chemotherapeutic drugs, and we first discovered that the combination of met and cDDP also had negative effect on cDDP treatment in certain OC cells.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jingjing Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Ping Zhou: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Tiancheng Wu: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Liping Zhang: Investigation, Data curation. Jiaqi Kang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jing Liao: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Daqiong Jiang: Supervision. Zheng Hu: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zhiqiang Han: Project administration, Supervision. Bo Zhou: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

We declare the manuscript is an original work which has not been previously published in whole or in part and is not under consideration for publication in any other journals. Its publication has been approved by all co-authors. All authors have contributed to this work and state no existing competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincerest thanks to all the members who participated in the data acquisition, writing, and revision of this article. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32171465, 82102392 and 32371541), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2022CFB209), the Regional Joint Fund Project of Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of China (Regional Cultivation Proiect, Grant No. 2021B1515140063), the Dongguan Social Development Key Proiect of China (Grant No. 20221800905772).

Contributor Information

Zheng Hu, Email: huzheng@whu.edu.cn.

Zhiqiang Han, Email: hanzq2003@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Bo Zhou, Email: bozhou2208@whu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1240–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb PM, Jordan SJ. Epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017;41:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings M, Nicolais O, Shahin M. Surgery in advanced ovary cancer: primary versus interval cytoreduction. Diagnostics. 2022;12(4) doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morand S, Devanaboyina M, Staats H, Stanbery L, Nemunaitis J. Ovarian cancer immunotherapy and personalized medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(12) doi: 10.3390/ijms22126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, Jayson GC, Kitchener H, Lopes T, Luesley D, Perren T, Bannoo S, Mascarenhas M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nachtigal MW, Altman AD, Arora R, Schweizer F, Arthur G. The potential of novel lipid agents for the treatment of chemotherapy-resistant human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancers. 2022;14(14) doi: 10.3390/cancers14143318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cen K, Chen M, He M, Li Z, Song Y, Liu P, Jiang Q, Xu S, Jia Y, Shen P. Sporoderm-Broken spores of ganoderma lucidum sensitizes ovarian cancer to cisplatin by ROS/ERK signaling and attenuates chemotherapy-related toxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.826716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31(15):1869–1883. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Xie HJ, Li YY, Wang X, Liu XX, Mai J. Molecular mechanisms of platinum‑based chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2022;47(4) doi: 10.3892/or.2022.8293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledermann JA, Drew Y, Kristeleit RS. Homologous recombination deficiency and ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;60:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamarra-Luques CD, Goyeneche AA, Hapon MB, Telleria CM. Mifepristone prevents repopulation of ovarian cancer cells escaping cisplatin-paclitaxel therapy. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan LY, Lu Y. New developments in molecular targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Discovery Med. 2018;26(144):219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishida M, Yamashita N, Ogawa T, Koseki K, Warabi E, Ohue T, Komatsu M, Matsushita H, Kakimi K, Kawakami E, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger metformin-dependent antitumor immunity via activation of Nrf2/mTORC1/p62 axis in tumor-infiltrating CD8T lymphocytes. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021;9(9) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J, Xia L, Xiang W, He W, Yin H, Wang F, Gao T, Qi W, Yang Z, Yang X, et al. Metformin selectively inhibits metastatic colorectal cancer with the KRAS mutation by intracellular accumulation through silencing MATE1. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117(23):13012–13022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918845117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JR, Chan DK, Shank JJ, Griffith KA, Fan H, Szulawski R, Yang K, Reynolds RK, Johnston C, McLean K, et al. Phase II clinical trial of metformin as a cancer stem cell-targeting agent in ovarian cancer. JCI insight. 2020;5(11) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rattan R, Giri S, Hartmann LC, Shridhar V. Metformin attenuates ovarian cancer cell growth in an AMP-kinase dispensable manner. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011;15(1):166–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jafarzadeh E, Montazeri V, Aliebrahimi S, Sezavar AH, Ghahremani MH, Ostad SN. Combined regimens of cisplatin and metformin in cancer therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Life Sci. 2022;304 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulati S, Desai J, Palackdharry SM, Morris JC, Zhu Z, Jandarov R, Riaz MK, Takiar V, Mierzwa M, Gutkind JS, et al. Phase 1 dose-finding study of metformin in combination with concurrent cisplatin and radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(2):354–362. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quattrini I, Conti A, Pazzaglia L, Novello C, Ferrari S, Picci P, Benassi MS. Metformin inhibits growth and sensitizes osteosarcoma cell lines to cisplatin through cell cycle modulation. Oncol. Rep. 2014;31(1):370–375. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou W, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Metformin prevents cisplatin-induced cognitive impairment and brain damage in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Gui Y, Ren J, Liu X, Feng Y, Zeng Z, He W, Yang J, Dai C. Metformin protects against cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis and acute kidney injury via AMPKΑ-regulated autophagy induction. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23975. doi: 10.1038/srep23975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao YY, Xiao JX, Wang XY, Wang T, Qu XH, Jiang LP, Tou FF, Chen ZP, Han XJ. Metformin-induced AMPK activation promotes cisplatin resistance through PINK1/Parkin dependent mitophagy in gastric cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.956190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janjetovic K, Vucicevic L, Misirkic M, Vilimanovich U, Tovilovic G, Zogovic N, Nikolic Z, Jovanovic S, Bumbasirevic V, Trajkovic V, et al. Metformin reduces cisplatin-mediated apoptotic death of cancer cells through AMPK-independent activation of Akt. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;651(1-3):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu SH, Yu J, Creeden JF, Sutton JM, Markowiak S, Sanchez R, Nemunaitis J, Kalinoski A, Zhang JT, Damoiseaux R, et al. Repurposing metformin, simvastatin and digoxin as a combination for targeted therapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2020;491:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asselin E, Mills GB, Tsang BK. XIAP regulates Akt activity and caspase-3-dependent cleavage during cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human ovarian epithelial cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):1862–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weng D, Song X, Xing H, Ma X, Xia X, Weng Y, Zhou J, Xu G, Meng L, Zhu T, et al. Implication of the Akt2/survivin pathway as a critical target in paclitaxel treatment in human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;273(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun C, Li N, Yang Z, Zhou B, He Y, Weng D, Fang Y, Wu P, Chen P, Yang X, et al. miR-9 regulation of BRCA1 and ovarian cancer sensitivity to cisplatin and PARP inhibition. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105(22):1750–1758. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter AG, Jänicke RU. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6(2):99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruvolo PP, Deng X, May WS. Phosphorylation of Bcl2 and regulation of apoptosis. Leukemia. 2001;15(4):515–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinner A, Wu W, Staudt C, Iliakis G. Gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(17):5678–5694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau CH, Seow KM, Chen KH. The molecular mechanisms of actions, effects, and clinical implications of PARP inhibitors in epithelial ovarian cancers: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(15) doi: 10.3390/ijms23158125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonilla B, Hengel SR, Grundy MK, Bernstein KA. RAD51 gene family structure and function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020;54:25–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-021920-092410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen H, Zhang L, Zuo M, Lou X, Liu B, Fu T. Inhibition of apoptosis through AKT-mTOR pathway in ovarian cancer and renal cancer. Aging. 2023;15(4):1210–1227. doi: 10.18632/aging.204564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yung MM, Ngan HY, Chan DW. Targeting AMPK signaling in combating ovarian cancers: opportunities and challenges. Acta Biochim. Biophy. Sin. 2016;48(4):301–317. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maréchal A, Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5(9) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kaçmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foretz M, Guigas B, Viollet B. Metformin: update on mechanisms of action and repurposing potential. Nature Rev. Endocrinol. 2023;19(8):460–476. doi: 10.1038/s41574-023-00833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotlieb WH, Saumet J, Beauchamp MC, Gu J, Lau S, Pollak MN, Bruchim I. In vitro metformin anti-neoplastic activity in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008;110(2):246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fatehi R, Rashedinia M, Akbarizadeh AR, Zamani M, Firouzabadi N. Metformin enhances anti-cancer properties of resveratrol in MCF-7 breast cancer cells via induction of apoptosis, autophagy and alteration in cell cycle distribution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023;644:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuco V, Benedetti V, Zunino F. ATM- and ATR-mediated response to DNA damage induced by a novel camptothecin, ST1968. Cancer Lett. 2010;292(2):186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storozhuk Y, Hopmans SN, Sanli T, Barron C, Tsiani E, Cutz JC, Pond G, Wright J, Singh G, Tsakiridis T. Metformin inhibits growth and enhances radiation response of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) through ATM and AMPK. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;108(10):2021–2032. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng T, Li L, Ling S, Fan N, Fang M, Zhang H, Fang X, Lan W, Hou Z, Meng Q, et al. Metformin enhances radiation response of ECa109 cells through activation of ATM and AMPK. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015;69:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z, Waldman AS, Wyatt MD. Expression and regulation of RAD51 mediate cellular responses to chemotherapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;83(6):741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng Y, Wang D, Xiong L, Zhen G, Tan J. Predictive value of RAD51 on the survival and drug responsiveness of ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):249. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B, Hou D, Liu Q, Wu T, Guo H, Zhang X, Zou Y, Liu Z, Liu J, Wei J, et al. Artesunate sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin by downregulating RAD51. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015;16(10):1548–1556. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1071738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McFarland MS, Cripps R. Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of cancer: focus on metformin and the insulin analogs. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(11):1159–1178. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.11.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang K, Bai P, Dai H, Deng Z. Metformin and risk of cancer among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary Care Diabetes. 2021;15(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson D, Frieson D, Zuber J, Solomon SS. Metformin has positive therapeutic effects in colon cancer and lung cancer. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2017;354(3):246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarhini Z, Manceur K, Magne J, Mathonnet M, Jost J, Christou N. The effect of metformin on the survival of colorectal cancer patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1):12374. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16677-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bo S, Benso A, Durazzo M, Ghigo E. Does use of metformin protect against cancer in type 2 diabetes mellitus? J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2012;35(2):231–235. doi: 10.1007/bf03345423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu OHY, Suissa S. Metformin and cancer: solutions to a real-world evidence failure. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(5):904–912. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smiechowski BB, Azoulay L, Yin H, Pollak MN, Suissa S. The use of metformin and the incidence of lung cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):124–129. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu Y, Hajjar A, Cryns VL, Trentham-Dietz A, Gangnon RE, Heckman-Stoddard BM, Alagoz O. Breast cancer risk for women with diabetes and the impact of metformin: a meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2023;12(10):11703–11718. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hampsch RA, Wells JD, Traphagen NA, McCleery CF, Fields JL, Shee K, Dillon LM, Pooler DB, Lewis LD, Demidenko E, et al. AMPK activation by metformin promotes survival of dormant ER(+) breast cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Res. 2020;26(14):3707–3719. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]