Abstract

Permanent artificial lighting systems in tourist underground environments promote the proliferation of photoautotrophic biofilms, commonly referred to as lampenflora, on damp rock and sediment surfaces. These green-colored biofilms play a key role in the alteration of native community biodiversity and the irreversible deterioration of colonized substrates. Comprehensive chemical or physical treatments to sustainably remove and control lampenflora are still lacking. This study employs an integrated approach to explore the biodiversity, eco-physiology and molecular composition of lampenflora from the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, in Italy. Reflectance analysis showed that photoautotrophic biofilms are able to absorb the totality of the visible spectrum, reflecting only the near-infrared light. This phenomenon results from the production of secondary pigments and the adaptability of these organisms to different metabolic regimes. The biofilm structure mainly comprises filamentous organisms intertwined with the underlying mineral layer, which promote structural alterations of the rock layer due to the biochemical attack of both prokaryotes (mostly represented by Brasilonema angustatum) and eukaryotes (Ephemerum spinulosum and Pseudostichococcus monallantoides), composing the community. Regardless of the corrosion processes, secondary CaCO3 minerals are also found in the biological matrix, which are probably biologically mediated. These findings provide valuable information for the sustainable control of lampenflora.

Keywords: Photoautotrophic biofilms, Geobiology, Biodeterioration, Show caves, Pertosa-Auletta Cave

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Biodiversity

Introduction

Since the seventeenth century, caves have represented an important tourist attraction due to their natural and cultural value. This interest has grown in recent decades, attracting approximately 80 million visitors per year worldwide1. However, the human fruition of these captivating environments affects their ecological balance by introducing exogenous substances and energy, such as the exhalation of CO2 and heat from tourists, along with the organic matter, including microplastic fibers, spores or plant seeds, attached to cloths or to the skin2–5. Nevertheless, the most widespread aesthetical problem in show caves is the development of lampenflora communities on rock walls, speleothems, and cave sediments. These photoautotrophic biofilms thrive on damp lit rock or sediment surfaces due to the presence of artificial lighting systems. Aerophytic cyanobacteria and algae generally compose the early stages of these communities, creating the conditions for the successive colonization by heterotrophic bacteria, fungi, bryophytes, ferns, and vascular plants6,7.

Lampenflora has become an urgent concern for show cave managers due to its impact on the colonized surfaces. This includes aesthetical alteration, such as the development of green patinas or crusts and modifications to the stone surface layer, according to UNI 11182:2006 classification of stone material alteration. Moreover, it causes irreversible chemical corrosion of substrates, particularly when biofilms grow on speleothems. This corrosion is generated by the metabolic activities of the organisms composing the community, which can secrete organic acids that promote surface dissolution8. Lampenflora represents also an ecological problem by introducing a considerable amount of organic matter into the subterranean oligotrophic ecosystem. This affects the autochthonous biodiversity, both qualitatively and quantitatively, given the opportunistic lifestyle of the organisms involved7,8.

As currently there are no effective and sustainable solutions for addressing the lampenflora issue in show caves (both in terms of surface cleaning and growth control), an in-depth characterization of the green biofilm communities that thrive in underground environments adapted to tourism is urgently needed6,8,9. To contribute to the knowledge of this “alien” community in show caves and to the development of mitigation strategies, this work aimed at providing a multi-proxy approach, involving morphological, physiological and taxonomic characterization of photosynthetic-based biofilms. This study particularly focused on lampenflora present in the Pertosa-Auletta Cave (Campania, southern Italy), where it grows on a calcareous substrate10, and is exposed to different lighting conditions, including variable distances from the light sources, wavelengths, and intensity. The findings will allow proposing more effective and sustainable controlling actions not only in show caves but also in any artificially illuminated underground ecosystem.

Experimental procedures

Study area and field analysis

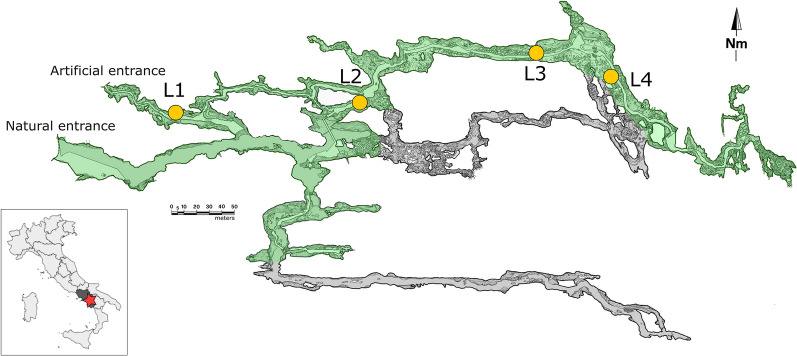

In the lit tourist trail of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, described in detail in Addesso9,11, four spatially distant areas, colonized by photosynthetic-based biofilms and exposed to different lighting conditions were sampled in October 2020. These areas were carefully selected to avoid areas previously subjected to treatments, such as commercial bleach applications9. The lighting setup comprises LED lamp systems, featuring an adjustable spectrum with different wavelengths: green light for sampling sites L1 and L4, and white light for sampling sites L2 and L3 (Table 1., Fig. 1). The cave is equipped with motion detection sensors that control the lights, turning them on according to the movement and rest stops of tourists. Each focus area is illuminated for 15 min, ensuring the safety of the visitors. Daily, the cave is open for eight hours and receives 60.000 visitors per year, with a biological rest period of 30 days in January. The annual temperature of Pertosa-Auletta Cave ranges between 13.2 and 16.1 °C, with relative humidity close to saturation (annual mean value: 97%) and CO2 concentration from 514 ppm up to peaks of 2781 ppm during the highest tourist loads10.

Table 1.

Field measurements on the four lampenflora sampling sites, related to photosynthetic activity of their communities.

| Sample | Fv/Fm | σ | PAR (μmol/m2 s) |

Distance from light source (m) |

Light color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 0.698 | 0.023 | 3.05 | 1.5 | Green |

| L2 | 0.720 | 0.114 | 4.01 | 3.5 | White |

| L3 | 0.622 | 0.037 | 2.42 | 4 | White |

| L4 | 0.704 | 0.018 | 1.85 | 2.5 | Green |

Figure 1.

Pertosa-Auletta Cave map; the yellow circles indicate the studied lampenflora samples along the tourist trail (green). The map was generated using the open-source vector graphics editor Inkscape 0.92 (www.inkscape.org).

In situ, non-destructive reflectance measurements were conducted using a Jaz System spectrometer (Ocean Optics), completed with a VIS–NIR module, and PAR (photosynthetically active radiation), through an irradiance quantum meter (LI-250 Light meter, Li-COR). In addition, measurements of maximal photosystem II (PSII) photochemical efficiency, given by Fv/Fm (variable fluorescence/maximal fluorescence) were carried out on 30-min dark-adapted surfaces, using a portable photosynthesis yield analyzer (MINI-PAM, WALTZ, Germany), equipped with a distance clip holder (Distance Clip 2010A, WALTZ, Germany), to assess the biofilms photosynthetic activity. Additionally, a representative sample was collected from each sampling site, using disposable and sterile scalpel blades and Eppendorf tubes, and then stored at − 80 °C until microbiological processing.

Microscopy observations

For microscopy surveys, oven-dried (50 °C) samples were analyzed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) using a FEI Teneo (ThermoFisher, MA, USA) microscope, with secondary electron detection mode, and an acceleration voltage of 5 kV for ultra-high resolution images.

Optical microscopy images of the biofilms were obtained on a transmitted light Eclipse E-100 Microscope (Nikon, Japan), equipped with a digital Nikon DS-Fi1 camera and processed in the image analysis program NIS Elements F. In addition, biofilm samples were observed using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope (Zeiss, Hamburg, Germany) with a GFP filter set (exciter 450–490 nm; dichroic 495 nm; emitter > 500 nm; Chroma set 41018), and image analysis was performed using AxioVision Software from Zeiss.

DNA metabarcoding data analysis

For molecular analyses, the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used to extract total DNA from approximately 250 mg of each sample, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA amount was determined using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen). The extracted DNA (with a minimum concentration of ~ 0.1 ng/μL), was analyzed via next-generation sequencing (NGS) targeting the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene for Prokaryotes, using the primer pair 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′)12, and the 18S rRNA gene for Eukaryotes, using the primer pair V4F (5′-CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATTCC-3′) and V4R (5′-ACTTTCGTTCTTGATTAA-3′)13. The amplicons were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform to generate 2 × 300 paired-end reads, according to Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) library preparation protocol. Chimeras were identified and removed by means of USEARCH14. Resulting reads were processed in QIIME215, whereas UCLUST16 was used for the similar sequences assignment to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) by clustering with a 97% similarity threshold. Paired-end reads were merged using FLASH14. SILVA database v.132 and NCBI were used for taxonomic identification of query sequences. The taxonomy names were updated according to the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes17,18. The raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence read Archive (SRA) database under project id PRJNA1012674.

Thermo-gravimetry analysis

Thermo-gravimetric analysis of dried (40 ºC) lampenflora samples were conducted using the Discovery series SDT 650 simultaneous DSC/TGA instrument (T.A Instruments Inc. Delaware, USA) under a N2 flow rate of 50 mL/min. The samples (5 mg) were placed in Alumina cups and heated from 50 to 650 °C at a heating rate of 20 ºC/min. TG, dTG curves and mass loss were obtained via TRIOS software (T.A. Instruments, Delaware, USA). To avoid interferences due to the expected great signals corresponding to the thermal degradation of the rock minerals, the thermal analysis was not carried out at temperatures higher than 650 °C.

Data analysis

Reflectance spectra were elaborated in the R 4.0.0 programming environment19, with functions from the “photobiologylnOut” and “ggspectra” packages, and using the open-source vector graphics editor Inkscape 0.92. Alpha diversity analysis, including the estimation of Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, and Good’s Coverage indices, was performed using QIIME2 (https://qiime2.org). The comparison between the structural bacterial diversity present in the different lit tourist trail of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave samples was performed using principal coordinate analysis (PCA) with CANOCO software version 4.56. The Simpson similarity index was computed with Paleontological Statistics (PAST 4.03).

Results

Lampenflora physiological features

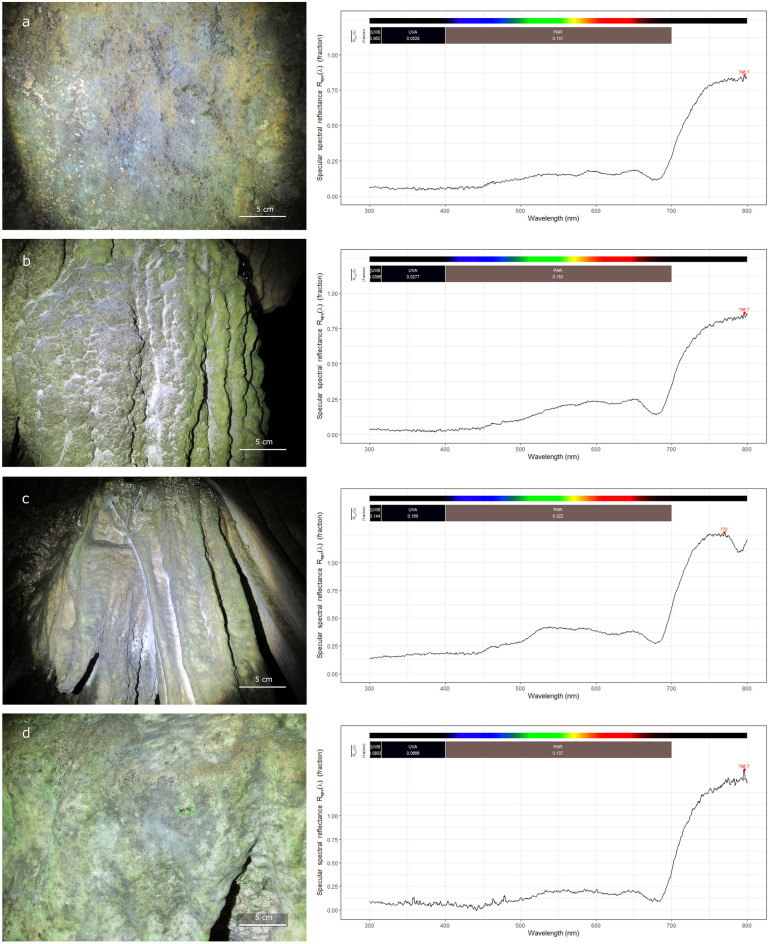

The lamps irradiating the sampled surfaces, located at diverse distances from the light sources (from 1 to 4 m), exhibit different light fluxes, with photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) values ranging from 1.85 to 4.01 μmol/m2 s. Reflectance spectra, reported in Fig. 2, highlight that the four lampenflora samples absorb the totality of the visible light (~ 400–700 nm), reflecting the near-infrared radiation (~ 700–800 nm). Moreover, the spectra indicate a slight reduction in the absorption of visible light between approximately 500–600 nm in samples L2 and L3, which have more distant light sources (3.5 and 4 m, respectively) from the rock colonized by biofilms, compared to L1 and L4, where the light sources are closer to the surfaces (1.5 and 2.5 m, respectively). The maximal PSII photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) shows values ranging between 0.698 and 0.720 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Field image of the four sampling sites from Pertosa-Auletta Cave, with the respective lampenflora reflectance spectra: (a) L1; (b) L2; (c) L3; (d) L4.

Lampenflora morphological features

Being a show cave that opened to tourists almost a century ago, the Pertosa-Auletta Cave is widely colonized by lampenflora, exhibiting green biofilms evident merely tens of meters from the cave entrance till the deeper sections of the cave, illuminated by artificial light along the tourist path (Fig. 2). Field images of the four sampling sites from Pertosa-Auletta Cave show variations in green shades (Fig. 2), which can indicate the dominance of different phototrophic microorganisms. For example, light green biofilm with patches of darker green is predominant in sampling site L1 (Fig. 2a), indicating a mixture of phototrophic species. Vivid and pale green biofilms with distinct whitish areas, likely due to calcite precipitation or localized actinobacteria growth, are observed in sampling sites L2 and L3 (Fig. 2b, c). L4 features vivid green biofilms interspersed with darker green areas (Fig. 2d), further suggesting a diversity of phototrophic organisms such as cyanobacteria or varying environmental conditions.

In addition to green biofilms, ferns and bryophytes are also present in certain areas of the cave, particularly in areas with sediments and mud, which provide the necessary substrate for their growth.

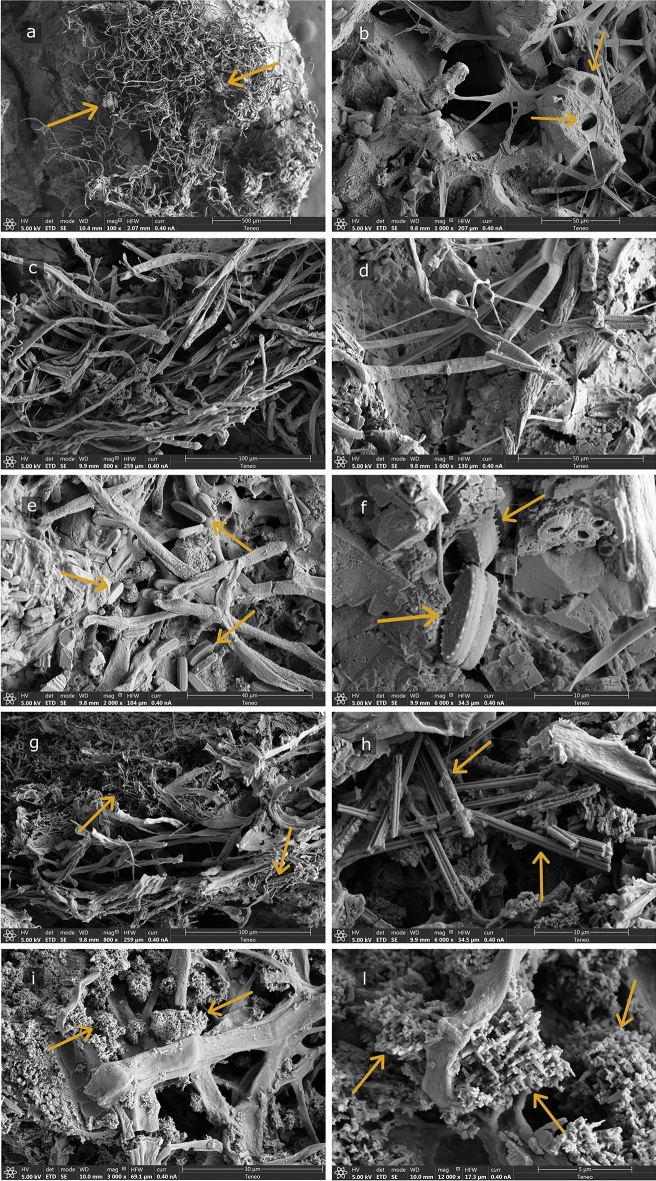

The FESEM (Fig. 3) and optical microscopy images (Fig. 4) shed light on the organization of the lampenflora community. The biofilms are mainly composed of filamentous bacteria and green algae, strongly entwined between them and with the mineral substrate. In some cases, it seems that the network of filamentous microorganisms traps minerals (Fig. 3a–d), with evidence of substrate corrosion (Fig. 3b). Figure 3b, e and f show also the presence of diatoms, whereas Fig. 3g–j reveal secondary minerals disseminated in the biofilm matrix, such as needle-shaped mineral crystals (g and h) and Ca-rich granular structures consisting of coalescing nanocrystals associated with microbial filaments (Fig. 3i and j).

Figure 3.

FESEM images of the green biofilm samples from Pertosa-Auletta Cave. Filamentous microorganisms are shown in L1 (a), L4 (b), L3 (c), L2 (d), diatoms in L4 (e) and L1 (f); needle-fiber calcite structures in L2 and L3 (g and h, respectively), and biogenic-like mineral grains associated with filamentous microorganisms (i and j, respectively). The yellow arrows indicate the features mentioned in the text.

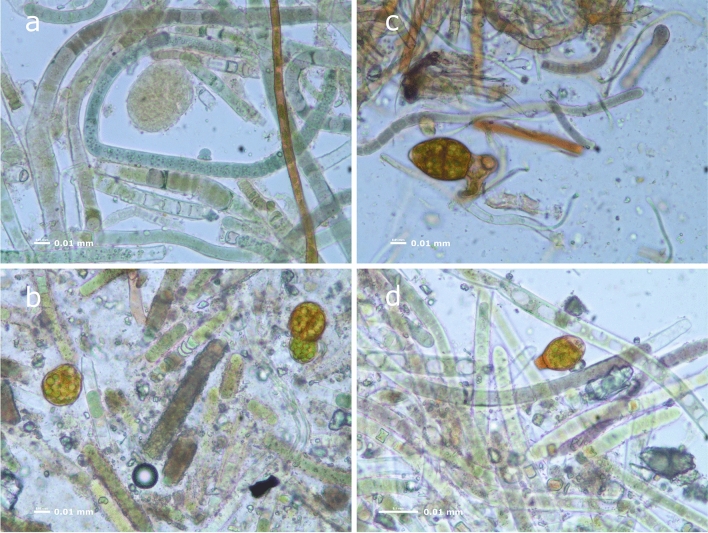

Figure 4.

Representative optical microscopy images of the green biofilm samples from Pertosa-Auletta Cave: L1 (a), L2 (b), L3 (c), L4 (d).

Figure 4 shows a general view of the diverse communities present, predominantly composed of filamentous photoautotrophic organisms. Filaments of green algae are particularly observed (Fig. 4a, b and d). Organisms of higher trophic levels, such as Rotifera or Cercozoa-like cells are also noticed (Fig. 4c).

Lampenflora community composition

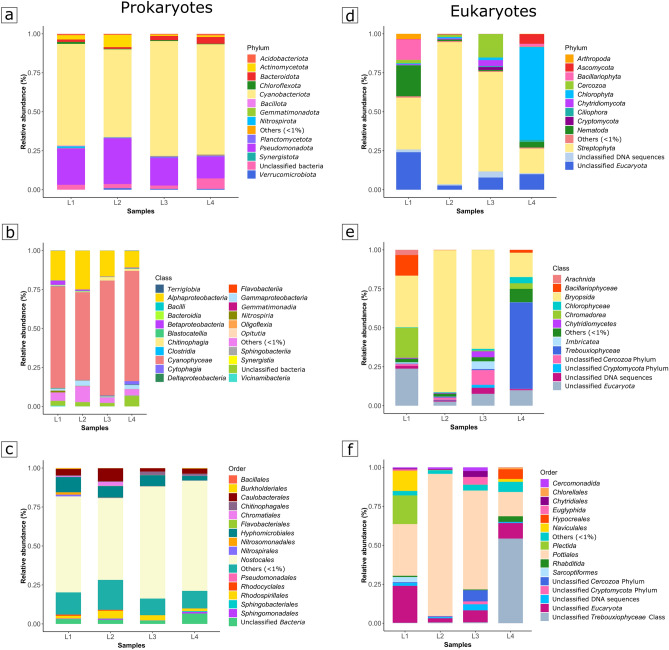

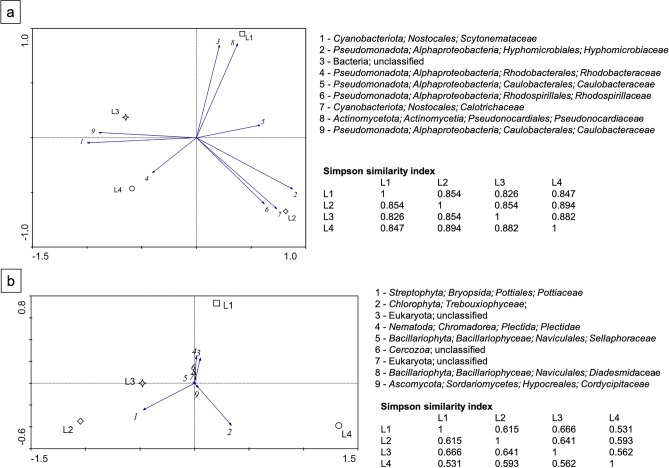

The four samples display similar bacterial composition (Fig. 5a–c). The most abundant phylum is Cyanobacteriota (mean value: 66.50%), represented mainly by Brasilonema angustatum, followed by Pseudomonadota (mean value: 21.01%), unclassified Bacteria (mean value: 3.64%), Actinomycetota (mean value: 3.15%), and Bacteroidota (mean value: 2.42%). Less represented phyla (< 1%) are also identified with a mean relative abundance equal to 3.28%. Within the Pseudomonadota phylum, the most represented classes are: Alphaproteobacteria (mean value: 17.74%), dominated, by Hyphomicrobiales (mean value: 6.79%), Caulobacterales (mean value: 4.47%) and Rhodospirillales (mean value: 2.93%) at the order level, Gammaproteobacteria (mean value: 1.97%) and Betaproteobacteria (mean value: 1.02%). The Simpson similarity index corroborates this observation (Fig. 6a), with all samples sharing similarities above 82. This indicates a high degree of similarity in the bacterial composition. However, the spatial distribution of the samples observed on the PCA analysis (the two principal components axes explained 92.4% of the variation) also shows that differences in the composition, especially among the less abundant populations are present. While samples L3 and L4 form the closest group, given their higher content in members of the family Scytonemataceae, samples L1 and L2 are more dispersed, likely due to their lower content in Scytonemataceae, which increases the influence of the differences in relative abundance of the other bacterial communities have in this distribution (Fig. 6a).

Figure 5.

Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes composition of the lampenflora for each sampling site. The barplots show the relative abundances (%) at phylum (a and d, respectively), class (b and e, respectively), and order levels (c and f, respectively).

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis of the most abundant populations (> 5%) present in the lit tourist trail of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, determined at the family level. Green light for sampling sites L1 and L4, and white light for sampling sites L2 and L3. The Simpson similarity index values are also present. (a) Bacterial populations; (b) Eukaryotic populations.

Concerning the identified Eukaryotes, the 4 samples show a clear differentiation (Fig. 5d–f), contrasting with the prokaryotic community profiles. In L1, the major phylum is Streptophyta (33.26%), followed by unclassified Eukaryota (24.05%), Nematoda (19.89%), dominated by Plectus opisthocirculus, Bacillariophyta (13.22%), represented by Sellaphora bacillum and Diadesmis gallica, Arthropoda (3.34%), and Cercozoa (1.30%) phyla. The L2 sample is almost entirely composed of Streptophyta (91.16%). In L3, the most abundant phyla are: Streptophyta (63.85%), Cercozoa (9.91%), Chytridiomycota (3.84%), Cryptomycota (1.87%) and Chlorophyta (1.66%). At the phylum level, numerous unclassified sequences were obtained (unclassified eukaryota, 7.82%, and unclassified DNA sequences, 3.87%).

The L4 diverges from the other samples due to the higher abundance of Chlorophyta (59.59%), represented by Pseudostichococcus monallantoides, followed by Streptophyta (15.87%), unclassified Eukaryota (9.96%), Ascomycota (6.21%), Nematoda (3.58%), Bacillariophyta (1.85%), and Ciliophora (1.13%). The Streptophyta phylum, which dominated in most samples, is solely represented by the species Ephemerum spinulosum.

The Simpson similarity index supports this differentiation (Fig. 6b), with all samples showing dissimilarities in their composition. Although the similarity values range from 0.53 to a maximum of 0.66, none exceed 0.5, indicating a lack of strong resemblance. The PCA analysis (with 98.2% of the variation explained by the two principal components axes) further reveals that these compositional differences, especially among the most abundant populations, affect their spatial distribution (Fig. 6b). Samples L2 and L3, which have a higher relative abundance of Pottiaceae members, are positioned closer together on the plot. In contrast, samples L1 and L4, displaying a lower relative abundance of this family, exhibit a more dispersed distribution in terms of their overall community abundance. This suggests that the less abundant populations play a significant role in shaping the spatial distribution of L1 and L4 in the PCA.

Metrics employed for microbial community richness and diversity estimations are reported in Table 2. The analysis generated for each sample ranges from 180 to 280 OTUs for Prokaryotes and from 80 to 193 OTUs for Eukaryotes. The analysis well covers the microbial diversity in lampenflora samples, given the average value of Good’s Coverage equal to 1.0%. Chao1 richness estimator ranges between 207.5 and 345.0. Shannon diversity indices present estimates ranging from a minimum of 2.468 to a maximum of 3.830 for Prokaryotes and from 0.925 and 3.817 for Eukaryotes, whereas Inverse Simpson diversity indices show values ranging from 0.480 to 0.729 for Prokaryotes and from 0.169 to 0.839 for Eukaryotes.

Table 2.

Community richness and diversity of prokaryotes and eukaryotes estimated for each sample, using several alpha diversity metrics (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, Good’s Coverage).

| Sample | OTUs | Chao1 | Shannon | Inverse Simpson | Good’s coverage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotes (16S rDNA) | L1 | 277 | 310.2 | 3.830 | 0.729 | 1.0 |

| L2 | 280 | 345.0 | 3.740 | 0.717 | 1.0 | |

| L3 | 253 | 287.2 | 2.468 | 0.480 | 1.0 | |

| L4 | 180 | 207.5 | 2.510 | 0.499 | 1.0 | |

| Eukaryotes (18S rDNA) | L1 | 193 | 193.3 | 3.817 | 0.839 | 1.0 |

| L2 | 135 | 135.0 | 0.925 | 0.169 | 1.0 | |

| L3 | 132 | 132.0 | 2.779 | 0.589 | 1.0 | |

| L4 | 80 | 80.0 | 2.837 | 0.697 | 1.0 |

Thermal analysis of lampenflora

Table 3 depicts the total and relative weight loss of lampenflora samples growing under the four different artificial lighting systems. Following the information provided by the derivative of weight loss (DTg; Supplementary Fig. S1), all thermograms were divided into 3 zones for study: W1 (50–175 °C), which is attributed to weight loss due to water evaporation and labile material, W2 (175–400 °C) which corresponds to loss of organic matter of intermediate stability, and W3 (400–600 °C) which comprises organic material of high thermal stability. The four samples are composed of the same types of organic material in terms of thermal stability with maximum weight loss in the ranges 315–330 °C and 440–460 °C, corresponding to fractions W2 and W3, respectively. Both peaks correspond to biopolymers (i.e., protein and lipid) typically present in biofilms20. L4 shows the lowest presence of thermally degradable material (3.5%; Table 3) and the greatest relative abundance of the most recalcitrant fraction, accounting up to 59% of the material.

Table 3.

Comparative thermogravimetry (TG) parameters in lampenflora samples summarizing: total weight loss for the temperature interval 50–600 °C (%), weight losses and relative weight losses for the temperature intervals: 50–175 °C (W1), 175–400 °C (W2) and 400–600 °C (W3).

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total weight loss | 50–600 °C | 19.9 | 9.6 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| Moisture and very labile OM (W1) | 50–175 °C | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Intermediate OM (W2) | 175–400 °C | 13.3 | 6.1 | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| Recalcitrant OM (W3) | 400–600 °C | 4.6 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| Relative Weight Loss (%) | |||||

| Moisture and very labile OM (W1) | 50–175 °C | 10 | 7 | 6 | 9 |

| Intermediate OM (W2) | 175–400 °C | 67 | 64 | 59 | 32 |

| Recalcitrant OM (W3) | 400–600 °C | 23 | 29 | 35 | 59 |

Discussion

The four sampling sites from the Pertosa-Auletta Cave show the characteristic photosynthetic-based biofilms of lampenflora, coating great extensions of the cave walls and speleothems exposed to artificial light9,21,22.

The maximal PSII photochemical efficiency, which is used as an indicator of photosynthetic performance in photoautotrophs, does not reach ideal conditions when compared to the optimum value (0.83) for several photoautotrophic species. These lower values are indicative of stress conditions23. The Fv/Fm values of the green biofilms analyzed in the Pertosa-Auletta Cave (ranging from 0.62 to 0.72) are slightly lower than the optimum, but they are in agreement with values reported by Grobbelaar24 and Pfendler25, which were 0.74 for lampenflora measured in Cango Cave (South Africa) and 0.70 in La Glacière Cave (France), respectively. This suggests that the lampenflora in the Pertosa-Auletta Cave exhibits satisfactory physiological activity, even under conditions of very low PAR. In fact, as reported in Mulec7, this community can thrive in underground ecosystems with very low photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), ranging from 0.2 to several hundred μmol m-2 s-1 photons, surviving in total darkness over long periods of time8,26. Even under such minimal PPFD conditions, light remains the main driver influencing the growth of photosynthetic-based biofilms in show caves, together with temperature, moisture and distance from the cave entrance27,28.

Furthermore, lampenflora exhibits a characteristic behavior in terms of the reflectance spectra. In fact, it does not reflect the green portion of the spectrum, instead it absorbs the entire visible light (~ 400–700 nm), reflecting only the near-infrared (~ 700–800 nm). In addition to the main photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll a (Chl a), several species within such community, including cyanobacteria and several eukaryotic phototrophs, are capable to produce accessory pigments (e.g., Chl b, c1, c2, c3, xanthophylls, and carotenes). The biosynthesis of these pigments is considerably high under the light saturation point (high light intensity levels), thus enlarging the absorption spectrum of visible radiation28 and displaying a notable tolerance to environmental stress26. Other lampenflora members, including algae, such as those belonging to the Chlorellales order from the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, can adopt mixotrophic and heterotrophic regimes, fixing CO2 through metabolic pathways different from photosynthesis7,8,28,29. Therefore, these phototrophic-based biofilms demonstrate an impressive capacity to adapt to different lighting conditions. Hence, intervening on light wavelengths to control its growth might not be enough, notwithstanding the yellow light (~ 580 nm) seems to limit green biofilm development on illuminated rock surfaces7. The decrease of the absorption in samples L2 and L3, which are exposed to a white light source positioned 3.5 and 4 m away from the rock surface, suggests that increasing the distance between the light sources and the exposed rock surfaces, as well as the use of appropriate light wavelengths in conjunction with measures to reduce light duration and intensity, can inhibit lampenflora growth30.

As revealed by FESEM, the green biofilms from the Pertosa-Auletta Cave induce both destructive and constructive mineral processes on the colonized rock surfaces. As lampenflora mainly consists of epilithic organisms, these extract nutrients from the rock substrate by secreting organic acids and other hygroscopic and negatively charged exopolymers capable of dissolving minerals31. These lampenflora-related processes can cause the formation of corrosion features on the rock surfaces, such as microboring and micropits, clearly visible under the microscope30,32,33.

Filamentous algae and cyanobacteria, in particular, can also physically disrupt the mineral substrates through the penetration of their thready bodies, exerting mechanical pressure that results in the fragmentation of mineral grains, which are trapped in the network of filamentous microorganisms, as observed in Fig. 3b. This process also increases the porosity and permeability of the host rock8,28,34. Moreover, the activity of cyanobacteria can promote the precipitation of secondary CaCO3 minerals8,28,30,32,33,35–37. Our findings confirm the presence of needle-shaped fibers (rods) with smooth surfaces, probably calcite moonmilk38, as well as Ca-rich granular structures consisting of coalescing nanocrystals entangled within the biomass, suggesting microbial mediation. Moonmilk is a white and very soft deposit, commonly reported in caves39,40. These white secondary mineral deposits have often been given a microbial origin, either through the direct precipitation of calcite by microorganisms or the creation of nucleation surfaces that facilitate mineral deposition38,41,42. In the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, lampenflora is also found coating moonmilk deposits, which likely result from the substrate’s biogenic corrosion. To conclusively determine the biogenicity of the coalescing nanocrystals, more rigorous characterization of these structures would be needed.

Optical microscopy examinations also allowed observing the biofilm organization, where we were able to discern numerous intertwined filamentous microorganisms. This included a diversity of filamentous green algae and cyanobacteria, as well as higher-level organisms of the trophic chain (e.g., rotifers, fungal spores, etc.). Correlating these observations with metabarcoding data presented in Fig. 5, we found congruence in the presence of green algae filaments, which are suggested to be predominantly Brasilomena. Organisms resembling the Cercozoa phylum seem to be visually identified and corroborated by the sequencing data. In contrast, direct metabarcoding evidence for members of the Rotifera phylum was not obtained or potentially corresponded to unidentified eukaryotes within the DNA-based analysis. Their presence suggests that the biomass of lampenflora provides a readily available food source. It is noteworthy that this additional biomass is usually absent in the typically oligotrophic cave ecosystem, and is a clear indicator of the ecological cave niche disruption. Moreover, since lampenflora is an invasive, opportunistic, and competitive community, it has the potential to invade the ecological niches of the autochthonous troglobitic species, which are often endemic. This non-native species introduction can affect subsurface microbial diversity and, in more severe cases, lead to the replacement of native species8,26,28.

Regarding the diversity of the lampenflora community found in the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, a relatively consistent prokaryotic composition across the four sampled areas is observed, indicating minimal variability in these microbial constituents under the different lighting conditions examined. Yet, significant distinctions emerged in the eukaryotic community profiles, where marked differences among samples are identified. This disparity suggests that the eukaryotic components of the lampenflora are more responsive or susceptible to variations in light exposure. Among Prokaryotes, Cyanobacteriota emerge as the most abundant, dominated by the tropical and aerophytic species Brasilonema angustatum. It is a nitrogen-fixer belonging to the large group of Nostocales order, originally isolated from freshwater biofilms in Hawai’i, where it grows in moss banks43. With its heterocysts, this aerophytic filamentous cyanobacterial species actively participates in the biogeochemical cycles, promoting an important release of bioavailable nitrogen43, particularly in these poor-nutrient underground ecosystems. Moreover, cyanobacterial species have a key role in the establishment of lampenflora community in lit underground environments. They act as pioneering organisms, together with algae, in the ecological succession, producing exopolymeric compounds that enhance the cohesion of cells to stone substrates and water retention7,8,26,44,45. In our previous study46, we conducted a thorough analysis of the prokaryotic community in areas of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave not exposed to artificial light, using NGS-based 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The identified community was predominantly composed of Pseudomonadota, followed by Acidobacteriota, Actinomycetota, Nitrospirota, Bacillota, among other less representative phyla, and a notable portion remaining unclassified at the phylum level. In these light-absent samples, cyanobacteria were not present, contrasting to the microbial composition in illuminated regions, where cyanobacteria are prevalent due to their reliance on light for photosynthesis, as expected. This highlights the significant influence of light on shaping microbial communities, particularly the role of photosynthesis in driving the presence and abundance of specific microbial taxa.

Concerning Eukaryotes, Streptophyta phylum is the most abundant, exclusively represented by Ephemerum spinulosum, a moss species of the Pottiaceae family. This moss is known to colonize moist habitats47, and was first identified in Europe in Northern Ireland, growing on exposed mud48. This species is also widespread in the Americas and in Asia, thriving on moist and drying soil, on stream edges, lakes or swamps or in ravine ditches48,49. Solely in one sample (L4), located in the cave’s deepest sector, the dominant phylum is Chlorophyta, represented by the green-algae Pseudostichococcus monallantoides. This halotolerant marine species demonstrates high resistance to dehydration due to its salt-tolerant physiological processes50. This characteristic, related to several processes such as the capability to synthetize organic osmolytes, might play a crucial role for phototrophs to survive in cave environments during the initial colonization phase by producing a coating protecting the underlying algae and cyanobacteria28. This photosynthetic marine species is rather uncommon in subterranean environments, being reported only in a recent survey on biofilms from the underground Roman Cryptoporticus of the National Museum Machado de Castro (UNESCO site, Coimbra, Portugal)51. Its presence in the Pertosa-Auletta cave system could be related to the anthropogenic pressure resulting from tourist activities at this site, as well as interactions with the surface native biodiversity.

The Shannon and Simpson indices highlight a low biodiversity for the lampenflora of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave. However, the sampling area closest to the cave entrance displays greater diversity compared to the deeper zone, probably due to the proximity to the external atmosphere, where the climatic influences are surely more pronounced. The natural transport route and dissemination of propagules through several processes (e.g., air currents, water flow, seepage, migratory animals, and even humans) represent important drivers in the successful colonization of lampenflora in this underground ecosystem. Additionally, favorable conditions of nutrients and moisture in the cave environment, and the specific physiology of the incoming organisms, seeds, and spores, contribute to this colonization28. Although the identified taxa, at higher taxonomic levels, exhibit qualitative and quantitative similarities with lampenflora samples from several different cave environments6,21,52, at species level, the detected groups are unique to the Pertosa-Auletta Cave. This is probably related to the autochthonous biodiversity of the surface, specific of the geographical area where the cave is located. It is worth remembering that the processes driving subsurface microbial diversity and speleothem growth are affected by surface conditions (e.g. precipitation, air-flows, vegetation and soil cover) and influenced by anthropogenic activities (e.g. land use changes, cave visits, cave adaptation for tourists). Miller et al.53,54, Piano et al.55 and Addesso et al.56,57 showed that surface land use changes and cave tourism activities had a profound impact on the microbial diversity and speleothem chemistry in several show caves from the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador) and from Italy.

Thermal analysis of the samples shows that degradation corresponded to the thermal breakdown of lipid and peptide biomolecules, typical of green algae58 and cyanobacteria59, which are the major constituents of the community. The Tg and DTg data also show a clear trend to contain less organic matter, and greater thermal stability as moving inwards from L1 to L4. In other words, the thermal analysis showed that the greater the distance to the cave entrance, the lower the organic matter content (weight loss 200–600 °C) and the higher the thermal stability (relative weight of W3 versus W2). This difference is especially remarkable for L4, and could be due to less and slower colonization by photosynthetic-based microorganisms at this location.

Concluding remarks

This multidisciplinary study of lampenflora from the touristic Pertosa-Auletta Cave provides a comprehensive overview of this “alien” photoautotrophic community in lit underground environments, whose diversity and eco-physiology are still scarcely known. The spectra reflectance surveys revealed the lampenflora capacity to absorb the entire visible radiation, reflecting only the near-infrared one. This is due to different trophic pathways that make the hypogean green biofilms resilient and resistant to long periods of darkness. Among the deterioration processes revealed by microscopy examinations, there is evidence of precipitation of CaCO3 secondary structures, such as rods, and moonmilk deposits, as well as destructive processes with the production of corrosion shapes, promoting an irreversible alteration of the colonized rock surfaces. Filamentous organisms, entangled to mineral grains, mainly represented by the nitrogen-fixing Brasilonema angustatum cyanobacterial species, together with the eukaryotes Ephemerum spinulosum and Pseudostichococcus monallantoides, constitute the community almost entirely. Their presence in the cave is likely influenced by local biodiversity and may be propagated through water movement, atmospheric transport, animal activity, and tourist visits, which could facilitate their introduction from the outside. Thermal analysis shows that the degree of colonization by lampenflora is related to the position within the cave system, with areas closer to the entrance being particularly vulnerable. Our findings contribute to better understand the potential risks of the colonization of underground environments by photosynthetic-based communities, which is essential to achieve effective and sustainable controlling strategies for their growth and proliferation in artificially illuminated caves. Future investigations, focusing on the definition of the lampenflora’s metagenomic profile, will try to clarify the specific functions of the community and the interactions among the organisms constituting these communities and their influence on the environment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work received support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) under the research project TUBOLAN PID2019-108672RJ-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. The financial support from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the MICROCENO project (10.54499/PTDC/CTA-AMB/0608/2020) is also acknowledged. This work was partly funded by University of Salerno (Italy) within the ORSA197159 and ORSA205530 projects. The support from the intramural project PIE_20214AT021 funded by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) is also acknowledged. A.Z.M. was supported by a Scientific Employment Stimulus (CEEC) contract (CEECIND/01147/2017) awarded by FCT and then a Ramón y Cajal contract (RYC2019-026885-I) from the MCIN. The authors are grateful to MIdA Foundation, manager of the Pertosa-Auletta Cave, and to the speleo-guide Vincenzo Manisera for the support.

Author contributions

RA, DB, JDW, and AZM conceived the study. RA performed the sampling activities and field analysis. Laboratory procedures were conducted by RA, BC and JMR. Funding was secured by AZM and DB. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RA and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The raw data generated for this study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under project id PRJNA1012674. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-66383-5.

References

- 1.Chiarini, V., Duckeck, J. & De Waele, J. A global perspective on sustainable show cave tourism. Geoheritage14(3), 1–27 (2022). 10.1007/s12371-022-00717-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Freitas, C. R. The role and the importance of cave microclimate in the sustainable use and management of show caves. Acta Carsol.39, 477–489 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith, A., Wynn, P. & Barker, P. Natural and anthropogenic factors which influence aerosol distribution in Ingleborough Show Cave, UK. Int. J. Speleol.42, 49–56 (2013). 10.5038/1827-806X.42.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulec, J. Human impact on underground cultural and natural heritage sites, biological parameters of monitoring and remediation actions for insensitive surfaces: Case of Slovenian show caves. J. Nat. Conserv.22(2), 132–141 (2014). 10.1016/j.jnc.2013.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balestra, V. & Bellopede, R. Microplastic pollution in show cave sediments: First evidence and detection technique. Environ. Pollut.292, 118261 (2022). 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfendler, S. et al. Biofilm biodiversity in French and Swiss show caves using the metabarcoding approach: First data. Sci. Total Env.615, 1207–1217 (2018). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulec, J. Lampenflora. In Encyclopedia of Caves (eds White, W. B. et al.) 635–641 (Elsevier, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baquedano Estévez, C., Moreno Merino, L., de la Losa, R. A. & Durán Valsero, J. J. The lampenflora in show caves and its treatment: An emerging ecological problem. Int. J. Speleol.48(3), 249–277 (2019). 10.5038/1827-806X.48.3.2263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addesso, R. et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the comparison of three contrasting treatments on both lampenflora community and underlying rock surface. Biofouling39, 204–217. 10.1080/08927014.2023.2202314 (2023). 10.1080/08927014.2023.2202314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addesso, R., Bellino, A. & Baldantoni, D. Underground ecosystem conservation through high-resolution air monitoring. Environ. Manage.69, 982–993 (2022). 10.1007/s00267-022-01603-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addesso, R. et al. Vermiculations from karst caves: The case of Pertosa-Auletta system (Italy). Catena182, 104178 (2019). 10.1016/j.catena.2019.104178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herlemann, D. P. R. et al. Transition in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J.5, 1571–1579 (2011). 10.1038/ismej.2011.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoeck, T. et al. Multiple marker parallel tag environmental DNA sequencing reveals a highly complex eukaryotic community in marine anoxic water. Mol. Ecol.19, 21–31 (2010). 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics26, 2460–2461 (2010). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods7, 335–336 (2010). 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics27, 2957–2963 (2011). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oren, A., Mareš, J. & Rippka, R. Validation of the names Cyanobacterium and Cyanobacterium stanieri, and proposal of Cyanobacteriota phyl. nov.. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.72, 10. 10.1099/ijsem.0.005528 (2022). 10.1099/ijsem.0.005528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oren, A. & Garrity, G. M. Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.71, 10. 10.1099/ijsem.0.005056 (2021). 10.1099/ijsem.0.005056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. www.R-project.org (2020).

- 20.Kebelmann, K., Hornung, A., Karsten, U. & Griffiths, G. Intermediate pyrolysis and product identification by TGA and Py-GC/MS of green microalgae and their extracted protein and lipid components. Biomass Bioenergy49, 38–48 (2013). 10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurado, V., del Rosal, Y., Gonzalez-Pimentel, J., Hermosin, B. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biological control of phototrophic biofilms in a show cave: The case of Nerja Cave. Appl. Sci.10, 3448 (2020). 10.3390/app10103448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurado, V. et al. Cleaning of phototrophic biofilms in a show cave: The case of Tesoro cave, Spain. Appl. Sci.12, 7357. 10.3390/app12157357 (2022). 10.3390/app12157357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell, K. & Johnson, G. N. Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. J. Exp. Bot.51(345), 659–668 (2000). 10.1093/jexbot/51.345.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grobbelaar, J. U. Lithophytic algae: A major threat to the karst formation of show caves. J. Appl. Phycol.12, 309–315 (2000). 10.1023/A:1008172227611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfendler, S. et al. UV-C as an efficient means to combat biofilm formation in show caves: Evidence from the La Glacière Cave (France) and laboratory experiments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.24, 24611–24623 (2017). 10.1007/s11356-017-0143-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J. & Massalski, A. Diversity of cyanobacteria on limestone caves. In Cyanobacteria (ed. Tiwari, A.) 45–57 (InTech, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piano, E. et al. Environmental drivers of phototrophic biofilms in an Alpine show cave (SW-Italian Alps). Sci. Total Env.536, 1007–1018 (2015). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulec, J. The diversity and ecology of microbes associated with lampenflora in cave and karst settings. In Microbial Life of Cave Systems (ed. Summers Engel, A.) 263–278 (De Gruyter, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roldán, M., Oliva, F., Gónzalez del Valle, M. A., Saiz-Jimenez, C. & Hernández-Mariné, M. Does green light influence the fluorescence properties and structure of phototrophic biofilms?. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.72, 3026–3031 (2006). 10.1128/AEM.72.4.3026-3031.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulec, J. & Kosi, G. Lampenflora algae and methods of growth control. J. Cave Karst Stud.71(2), 109–115 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macedo, M. F., Miller, A. Z., Dionísio, A. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. Biodiversity of cyanobacteria and green algae on monuments in the Mediterranean Basin: An overview. Microbiol-SGM155, 3476–3490. 10.1099/mic.0.032508-0 (2009). 10.1099/mic.0.032508-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Northup, D. E. & Lavoie, K. H. Geomicrobiology of caves: A review. Geomicrobiol. J.18, 199–222 (2001). 10.1080/01490450152467750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, A. Z. et al. Laboratory-induced endolithic growth in calcarenites: Biodeteriorating potential assessment. Microb. Ecol.60, 55–68. 10.1007/s00248-010-9666-x (2010). 10.1007/s00248-010-9666-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caneva, G., Nugari, M. P. & Salvadori, O. Plant biology for cultural heritage: Biodeterioration and conservation. Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles (2008).

- 35.Barton, H. A. & Northup, D. E. Geomicrobiology in cave environments: Past, current and future perspectives. J. Cave Karst Stud.69(1), 163–178 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krause, S. et al. Endolithic algae affect modern coral carbonate morphology and chemistry. Front. Earth Sci.7, 304 (2019). 10.3389/feart.2019.00304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popović, S. et al. Biofilms in caves: Easy method for the assessment of dominant phototrophic groups/taxa in situ. Environ. Monitor. Assess.192, 720 (2020). 10.1007/s10661-020-08686-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller, A. Z. et al. Origin of abundant moonmilk deposits in a subsurface granitic environment. Sedimentology65, 1482–1503 (2018). 10.1111/sed.12431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cañaveras, J. C. et al. On the origin of fiber calcite crystals in moonmilk deposits. Naturwissenschaften93, 27–32 (2006). 10.1007/s00114-005-0052-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baskar, S., Baskar, R. & Routh, J. Biogenic evidences of moonmilk deposition in the Mawmluh Cave, Meghalaya, India. Geomicrobiol. J.28, 252–265 (2011). 10.1080/01490451.2010.494096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blyth, A. J. & Frisia, S. Molecular evidence for bacterial mediation of calcite formation in cold high-altitude caves. Geomicrobiol. J.25, 101–111 (2008). 10.1080/01490450801934938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curry, M. D., Boston, P. J., Spilde, M. N., Baichtal, J. F. & Campbell, A. R. Cottonballs, a unique subaqueous moonmilk, and abundant subaerial moonmilk in Cataract Cave, Tongass National Forest, Alaska. Int. J. Speleol.38, 111–128 (2009). 10.5038/1827-806X.38.2.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaccarino, M. A. & Johansen, J. R. Brasilonema angustatum sp. nov. (Nostocales), a new filamentous cyanobacterial species from the Hawaiian Islands. J. Phycol.48, 1178–1186 (2012). 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popović, S. et al. Cave biofilms: Characterization of phototrophic cyanobacteria and algae and chemotrophic fungi from three caves in Serbia. J. Cave Karst Stud.79, 10–23 (2017). 10.4311/2016MB0124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Havlena, Z., Kieft, T. L., Veni, G., Horrocks, R. D. & Jones, D. S. Lighting effects on the development and diversity of photosynthetic biofilm communities in Carlsbad Cavern, New Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.87, e02695-e2720 (2021). 10.1128/AEM.02695-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Addesso, R. et al. Microbial community characterizing vermiculations from karst caves and its role in their formation. Microb. Ecol.81, 884–896 (2021). 10.1007/s00248-020-01623-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ignatov, M. S., Ignatova, E. A. & Malashkina, E. V. Ephemerum spinulosum Bruch & Schimp. (Bryophyta), a new species for Russia. Arctoa22, 97–100 (2013). 10.15298/arctoa.22.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holyoak, D. Ephemerum spinulosum Bruch & Schimp. (Ephemeraceae) in Northern Ireland: A moss new to Europe. J. Bryol.23, 139–141 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Infante, M. & Heras, P. Ephemerum cohaerens (Hedw.) Hampe and E. spinulosum Bruch & Schimp (Ephemeraceae, Bryopsida), new to the Iberian Peninsula. Cryptogamie Bryol.26(3), 327–333 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jurado, V. et al. Holistic approach to the restoration of a vandalized monument: The Cross of the Inquisition, Seville City Hall, Spain. Appl. Sci.12, 6222 (2022). 10.3390/app12126222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soares, F., Trovão, J. & Portugal, A. Phototrophic and fungal communities inhabiting the Roman cryptoporticus of the national museum Machado de Castro (UNESCO site, Coimbra, Portugal). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.38, 157 (2022). 10.1007/s11274-022-03345-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burgoyne, J. et al. Lampenflora in a show cave in the Great Basin is distinct from communities on naturally lit rock surfaces in nearby wild caves. Microorganisms9, 1188 (2021). 10.3390/microorganisms9061188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller, A. Z. et al. Colored Microbial coatings in show caves from the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador): First microbiological approach. Coatings10, 1134 (2020). 10.3390/coatings10111134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller, A. Z. et al. Organic geochemistry and mineralogy suggest anthropogenic impact in speleothem chemistry from volcanic show caves of the Galapagos. iScience25, 104556 (2022). 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piano, E. et al. Tourism affects microbial assemblages in show caves. Sci. Total Env.1(871), 162106 (2023). 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Addesso, R., De Waele, J., Cafaro, S. & Baldantoni, D. Geochemical characterization of clastic sediments sheds light on energy sources and on alleged anthropogenic impacts in cave ecosystems. Int. J. Earth Sci.111(3), 919–927 (2022). 10.1007/s00531-021-02158-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Addesso, R., Morozzi, P., Tositti, L., De Waele, J. & Baldantoni, D. Dripping and underground river waters shed light on the ecohydrology of a show cave. Ecohydrology16(3), e2511 (2023). 10.1002/eco.2511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang, B. & Yoon, H. S. Thermal analysis of green algae for comparing relationship between particle size and heat evolved. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery5, 279–285 (2015). 10.1007/s13399-014-0145-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Supeng, L., Guirong, B., Hua, W., Fashe, L. & Yizhe, L. TG-DSC-FTIR analysis of cyanobacteria pyrolysis. Phys. Procedia33, 657–662 (2012). 10.1016/j.phpro.2012.05.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data generated for this study are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under project id PRJNA1012674. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.