Abstract

Background

Over the past three decades, our understanding of sleep apnea in women has advanced, revealing disparities in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment compared to men. However, no real-life study to date has explored the relationship between mask-related side effects (MRSEs) and gender in the context of long-term CPAP.

Methods

The InterfaceVent-CPAP study is a prospective real-life cross-sectional study conducted in an apneic adult cohort undergoing at least 3 months of CPAP with unrestricted mask-access (34 different masks, no gender specific mask series). MRSE were assessed by the patient using visual analog scales (VAS). CPAP-non-adherence was defined as a mean CPAP-usage of less than 4 h per day. The primary objective of this ancillary study was to investigate the impact of gender on the prevalence of MRSEs reported by the patient. Secondary analyses assessed the impact of MRSEs on CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence depending on the gender.

Results

A total of 1484 patients treated for a median duration of 4.4 years (IQ25–75: 2.0–9.7) were included in the cohort, with women accounting for 27.8%. The prevalence of patient-reported mask injury, defined as a VAS score ≥ 5 (p = 0.021), was higher in women than in men (9.6% versus 5.3%). For nasal pillow masks, the median MRSE VAS score for dry mouth was higher in women (p = 0.039). For oronasal masks, the median MRSE VAS score for runny nose was higher in men (p = 0.039). Multivariable regression analyses revealed that, for both women and men, dry mouth was independently and negatively associated with CPAP-usage, and positively associated with CPAP-non-adherence.

Conclusion

In real-life patients treated with long-term CPAP, there are gender differences in patient reported MRSEs. In the context of personalized medicine, these results suggest that the design of future masks should consider these gender differences if masks specifically for women are developed. However, only dry mouth, a side effect not related to mask design, impacts CPAP-usage and non-adherence.

Trial Registration: InterfaceVent is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03013283).First registration date is 2016–12-23.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-024-02965-1.

Keywords: Sleep apnea, Leaks, Side-effects, Women

Background

The prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome (SAS) in adults over the age of 35 ranges from 5.9% to 79.2%, depending on the clinical symptoms and apnea/hypopnea scoring criteria used [1, 2]. In 2024, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) remains the cornerstone of SAS treatment, despite major advances in alternative therapies [3–5]. CPAP-adherence is associated with improved quality of life (QoL) [6, 7], and reduced incident or recurrent major adverse cardiovascular events [8, 9].

Over the past three decades, our understanding of SAS in women has grown, highlighting the existence of disparities between women and men in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment [10–12]. The apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) is lower in women than in men, and QoL is worse in women [11, 13]. Some studies also suggest that CPAP-adherence is poorer in women [12].

Although our knowledge about the specificities of SAS in women is increasing, real gaps in the research persist, as highlighted by a recent editorial advocating for targeted research on gender disparities in SAS [14]. While several manufacturers have developed women's and men's versions of certain series of their masks, no external study has validated the concept of a gender-specific mask. To date, there is no long-term study reporting gender differences in MRSEs, nor studies reporting the impact of gender-related MRSEs on CPAP-adherence.Therefore, the primary objective of the present study was to investigate the impact of gender on the prevalence of patient-reported MRSEs. Secondary analyses assessed the impact of MRSEs on CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence (defined as a mean CPAP-usage of less than 4 h per day) depending on gender.

Methods

Study design and study population

This study presents an ancillary analysis of the InterfaceVent study, which was exhaustively described in a prior publication [15]. Briefly, the InterfaceVent study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03013283) was a prospective, real-life cross-sectional study conducted from February 7, 2017 to April 1, 2019 in adults undergoing at least 3 months of CPAP or non-invasive ventilation. We herein report results for SAS-patients treated exclusively by CPAP. SAS was defined according to the French Social Security (FSS) system criteria: (1) Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) ≥ 30/h (or AHI ≥ 15/h and more than 10/h respiratory-effort-related arousals), and (2) associated with sleepiness and at least three of the following symptoms: snoring, headaches, hypertension, reduced vigilance, libido disorders, nocturia. These criteria must be met in order for patients to be reimbursement by the FSS. The Apard ADENE group, a non-profit home care provider, provided care to patients following an initial prescription by one of the 336 device-prescribing physicians in the Occitanie region of France. Patient inclusion occurred during one of the routine home visits, conducted by one of the 32 Apard technicians, that are required to receive reimbursement for CPAP treatment by the FSS-single payer system. No CPAP-adherence threshold was required for reimbursement, and patients with poor compliance were not systematically excluded (for exclusion criteria, see [15]). Patients had unlimited access to 34 masks (see [15]). No specific women’s or men’s versions of the mask series were available at the time of study.

Collected data

Side-effect visual analogue scales (VAS; see below), the Epworth-Sleepiness-Scale and the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire were administered by a technician employed by the home care provider during a scheduled visit, as previously described [15].

An 11-point VAS (0 = no reported side-effect to 10 = very uncomfortable side-effect) was used to assess the following MRSEs: dry mouth, partner disturbance due to leaks, patient-reported leaks, noisy mask, heavy mask, painful mask, mask injury, painful harness, harness injury, redness of the eyes, itchy eyes, dry nose, stuffy nose, and runny nose. Importantly, the technician did not help patients fill out the questionnaires and the VAS.

Statistical analyses

Continuous data were expressed as medians with their associated quartile ranges due to non-Gaussian distributions. Qualitative parameters were expressed as numbers and percentages. Gender effect was evaluated using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for quantitative data, and Chi-square or Fisher tests for qualitative effects. Side-effects and mask model, according to gender and mask type, were compared using Chi-square or Fisher tests. For these last comparisons, corrected p-value with False Discovery Rate correction were performed. To visualize correlations between MRSEs for a given gender and mask type, a principal component analysis was performed for women and men on nasal (NM), oronasal (ONM) and nasal pillow masks (NPM). Univariate and Multivariable logistic and linear regression analyses were used to study, by gender, associations between CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence (defined as a mean CPAP-usage of less than 4 h per day) versus explanatory variables (demographic data, Epworth-Sleepiness-Scale (ESS) score, EQ-5D-3L-questionnaires, device/mask data and MRSEs). All statistical analyses were performed with R (V.4.3.1).

Results

Population baseline characteristics according to mask type and gender are summarized in Table 1. A total of 1484 patients (27.8% women) were included in the analysis. Patients received significantly different mask types according to gender (p = 0.002). Specifically, 58.6% of women received NM versus 52.5% of men, 19.6% of women received NPM versus 16.4% of men, and 21.8% of women received oronasal masks versus 31.1% of men. The median BMI was higher in women than in men (32.5 kg/m2 vs. 30.5 kg/m2, p < 0.001), and more than half of patients were obese (62.2% for women vs. 53.9% for men, p = 0.007). Initial AHI ≥ 30/h occured less often in women (81.2% vs. 88.1%, p = 0.001). Women were more likely to live alone compared to men (46.2% vs. 20.7%, p < 0.001), and experienced anxiety/depression more frequently (51.5% vs. 34.8%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, median EQ-5D-3L health VAS (0–100 score) was lower in women than in men (60.6 vs. 70.2, p < 0.001). Active workers were 19.8% and 20.9% for women and men respectively (p = 0.628), active smokers were 11.9% and 11.8% for women and men respectively (p = 0.952). Median global leaks and global large leaks were lower in women than in men for NM (p < 0.001 and p = 0.039). Mean pressure was lower in women for NM (p = 0.004). The median CPAP-usage was lower in women than in men for both NM and NPM (p = 0.005 and p < 0.001). Women's lower CPAP-usage is also reflected in their higher level of non-adherence (10.9% vs. 6.5%, p = 0.005).

Table 1.

Population characteristics according to mask type and gender

| Whole population (N = 1484) | Nasal mask (N = 804) | Nasal pillow mask (N = 257) | Oronasal mask (N = 423) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N = 413 | Men, N = 1071 | P value | Women, N = 242 | Men, N = 562 | p-value | Women, N = 81 | Men, N = 176 | p-value | Women, N = 90 | Men, N = 333 | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 67.0 [61.0; 74.0] | 67.0 [60.0; 74.0] | 0.8181 | 67.0 [62.0; 74.8] | 67.0 [61.0; 74.0] | 0.5531 | 65.0 [58.0; 72.0] | 66.0 [60.0; 73.3] | 0.3331 | 67.0 [59.3; 72.8] | 68.0 [60.0; 74.0] | 0.6411 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.5 [27.7; 36.9] | 30.5 [27.5; 34.0] | < 0.0011 | 32.5 [27.9; 37.2] | 30.2 [27.3; 33.8] | < 0.0011 | 30.3 [26.4; 36.0] | 30.2 [27.3; 33.7] | 0.8501 | 33.6 [28.7; 36.8] | 31.0 [28.1; 34.5] | 0.0141 |

| Diagnostic AHI (events/h) | 36.0 [30.0; 49.0] | 40.2 [32.0; 58.0] | < 0.0011 | 36.0 [30.0; 50.0] | 40.4 [32.0; 57.2] | 0.0051 | 36.0 [30.0; 46.0] | 40.0 [31.0; 57.5] | 0.0201 | 36.0 [31.0; 49.0] | 41.0 [31.0; 59.0] | 0.0971 |

| Presence of partner (%) | 218 (53.8) | 832 (79.3) | < 0.0012 | 124 (52.3) | 441 (79.3) | < 0.0012 | 45 (57.0) | 140 (81.4) | < 0.0012 | 49 (55.1) | 251 (78.2) | < 0.0012 |

| Epworth scale | ||||||||||||

| ESS (0–24 score) | 5.0 [3.0; 8.0] | 5.0 [3.0; 9.0] | 0.3471 | 4.0 [2.0; 8.0] | 5.0 [3.0; 8.8] | 0.0431 | 7.0 [3.0; 10.0] | 5.0 [3.0; 9.0] | 0.1491 | 6.0 [3.0; 9.0] | 6.0 [3.0; 9.0] | 0.8031 |

| RES (%) | 63 (15.3) | 177 (16.5) | 0.5512 | 32 (13.2) | 89 (15.8) | 0.3422 | 14 (17.3) | 32 (18.2) | 0.8622 | 17 (18.9) | 56 (16.8) | 0.6442 |

| Device | ||||||||||||

| CPAP-usage (h/day) | 6.5 [5.0; 7.5] | 6.8 [5.7; 7.8] | < 0.0011 | 6.5 [5.3; 7.8] | 7.0 [5.8; 7.9] | 0.0051 | 6.2 [4.8; 7.0] | 6.8 [5.8; 7.8] | < 0.0011 | 6.5 [5.0; 7.4] | 6.5 [5.5; 7.8] | 0.0981 |

| Non-adherence (%) | 45 (10.9) | 70 (6.5) | 0.0052 | 18 (7.4) | 26 (4.6) | 0.1082 | 14 (17.3) | 13 (7.4) | 0.0162 | 13 (14.4) | 31 (9.3) | 0.1572 |

| Current AHIflow (events/h) | 1.6 [0.8; 3.0] | 2.1 [1.0; 4.2] | < 0.0011 | 1.4 [0.7; 2.8] | 1.8 [1.0; 4.0] | < 0.0011 | 1.6 [0.9; 3.0] | 1.6 [0.8; 3.0] | 0.9241 | 1.9 [1.1; 3.1] | 2.9 [1.5; 5.5] | < 0.0011 |

| Treatment duration (years) | 3.6 [1.5; 8.4] | 5.0 [2.3; 10.2] | < 0.0011 | 3.6 [1.4; 8.3] | 5.1 [2.0; 10.9] | 0.0101 | 3.2 [1.4; 6.7] | 6.5 [3.3; 10.6] | < 0.0011 | 4.0 [1.7; 9.2] | 4.2 [2.3; 9.2] | 0.6261 |

| Mean pressure (cmH2O) | 8.0 [6.2; 9.8] | 8.3 [6.8; 10.0] | < 0.0011 | 7.6 [6.0; 9.5] | 8.0 [6.6; 9.8] | 0.0041 | 7.3 [6.2; 8.8] | 7.7 [6.5; 9.4] | 0.2081 | 9.1 [7.9; 10.6] | 9.1 [7.6; 10.8] | 0.9261 |

| 90th/95th pressure (cmH2O) | 10.0 [8.0; 11.6] | 10.0 [8.4; 11.8] | 0.0331 | 9.8 [7.9; 11.3] | 10.0 [8.0; 11.5] | 0.0611 | 9.5 [7.9; 10.8] | 9.6 [8.0; 11.0] | 0.4141 | 11.0 [9.6; 12.0] | 10.9 [9.3; 12.0] | 0.5201 |

| Fixed pressure (%) | 41 (10.0) | 150 (14.0) | 0.0372 | 24 (10.0) | 80 (14.2) | 0.0982 | 8 (9.9) | 25 (14.2) | 0.3352 | 9 (10.0) | 45 (13.5) | 0.3752 |

| Comfort mode (%) | 65 (15.7) | 169 (15.8) | 0.9842 | 38 (15.7) | 92 (16.4) | 0.8142 | 13 (16.1) | 29 (16.5) | 0.9312 | 14 (15.6) | 48 (14.4) | 0.7862 |

| Heated humidifier (%) | 255 (61.7) | 626 (58.5) | 0.2472 | 143 (59.1) | 291 (51.8) | 0.0562 | 52 (64.2) | 107 (60.8) | 0.6022 | 60 (66.7) | 228 (68.5) | 0.7452 |

| Heated breathing tube (%) | 27 (6.5) | 32 (3.0) | 0.0022 | 12 (5.0) | 14 (2.5) | 0.0702 | 8 (9.9) | 5 (2.8) | 0.0283 | 7 (7.8) | 13 (3.9) | 0.1573 |

| Mask | ||||||||||||

| Mask availability since 2013 (%) | 170 (41.2) | 440 (41.2) | 0.9792 | 66 (27.3) | 171 (30.5) | 0.3532 | 42 (51.9) | 61 (34.9) | 0.0102 | 62 (68.9) | 208 (62.7) | 0.2742 |

| Unintentional leaks (l/min) | 2.4 [0.0; 7.2] | 2.5 [0.0; 7.5] | 0.6011 | 2.5 [0.0; 8.0] | 2.5 [0.0; 8.4] | 0.6811 | 1.2 [0.0; 4.5] | 2.4 [0.0; 7.3] | 0.2191 | 0.0 [0.0; 3.6] | 1.2 [0.0; 7.3] | 0.2581 |

| Unintentional large leaks (%) | 0.1 [0.0; 0.8] | 0.1 [0.0; 0.9] | 0.8281 | 0.1 [0.0; 0.7] | 0.0 [0.0; 0.6] | 0.5301 | 0.0 [0.0; 0.8] | 0.1 [0.0; 0.6] | 0.9941 | 0.1 [0.0; 1.0] | 0.3 [0.0; 3.8] | 0.2021 |

| Global leaks (l/min) | 28.0 [22.0; 34.0] | 36.0 [30.0; 45.5] | < 0.0011 | 27.0 [21.0; 33.8] | 33.0 [30.0; 43.0] | < 0.0011 | 31.0 [25.8; 33.5] | 36.0 [28.0; 43.0] | 0.2611 | 28.0 [23.0; 39.0] | 37.5 [33.1; 48.2] | 0.1711 |

| Global large leaks (%) | 0.4 [0.0; 2.6] | 1.0 [0.2; 6.4] | 0.0151 | 0.3 [0.0; 2.2] | 1.0 [0.1; 5.0] | 0.0391 | 0.8 [0.2; 4.7] | 0.9 [0.4; 5.4] | 0.7691 | 1.6 [0.1; 2.7] | 5.0 [0.2; 8.8] | 0.5301 |

Leaks were obtained using CPAP built-in software [15]. Data are reported as medians and quartiles or numbers and percentages of total as appropriate. 1Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test; 2Chi-square test; 3Fisher exact test. Bolds variables are statistically significant at the 5% threshold

AHI: Apnea–Hypopnea Index; AHIflow: AHI reported by device; BMI: Body Mass Index; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; ESS: epworth sleepiness scale; N = number of patients responding, Non-adherence: CPAP-usage under 4 h per day; RES: residual excessive sleepiness (ESS score > 10); VAS: visual analogue scale

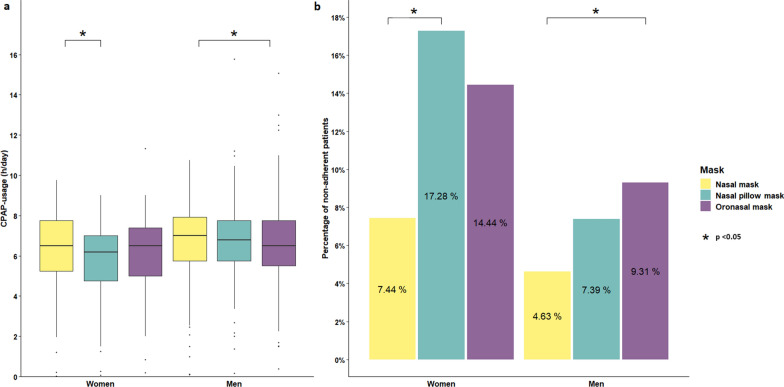

CPAP-usage and non-adherence according to mask type and gender are depicted in Fig. 1. For women, median CPAP-usage was higher in NM than in NPM (6.5 h/day vs. 6.2 h/day, p = 0.036), reflecting greater non-adherence in NPM compared with NM (17.3% vs. 7.4%, p = 0.031). For men, median CPAP-usage was higher in NM than in ONM (7.0 h/day vs. 6.5 h/day, p = 0.038), reflecting greater non-adherence in ONM compared with NM (9.3% vs. 4.6%, p = 0.017).

Fig. 1.

CPAP-usage (a) and CPAP-non-adherence (b) according to maks type and gender

Prevalence of mask related side‑effects reported by the patient depending on gender and mask type

Gender differences in terms of specific VAS scores according to mask type are depicted in Fig. 2. When we compared genders, we found that median MRSE VAS scores for partner disturbing leaks were lower in women (p < 0.001) for NM, were lower for women for runny nose (p = 0.039) for ONM, and were higher in women for dry mouth (p = 0.039) for NPM.

Fig. 2.

Visual analogue scales for mask related side-effect scores according to gender and mask type

MRSE frequencies (VAS score ≥ 1 and VAS score ≥ 5) according to gender were analyzed (see Additional file 1). Partner disturbing leaks were lower in women than in men (p < 0.001 for VAS score ≥ 1 and p = 0.004 for VAS score ≥ 5); the prevalence of mask injury was higher in women than in men (9.6% and 5.3%, respectively) for a VAS score ≥ 5 (p = 0.021).

Mask differences in terms of specific VAS scores according to gender were analyzed (see Additional file 2). When we compared mask types, we found that, for women, a median MRSE VAS score for runny nose was higher in NPM than in ONM (p = 0.045), and median MRSE VAS score for patient reported leaks was higher in ONM than in NM (p = 0.012). For men, median MRSE VAS scores for dry mouth, patient reported leaks, partner disturbing leaks, itchy eyes and red eyes were higher in ONM than in NM (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.042, p = 0.034 and p = 0.013, respectively). Median MRSE VAS scores for dry mouth, itchy eyes and red eyes were higher in ONM than in NM (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). Median MRSE VAS score for itchy eyes was higher in NM than in NPM (p = 0.025).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) suggested that there were comparable groups of side effects according to gender for NM and ONM (Additional file 3). For NPM, the groups were more dispersed, with different positioning of leak items by gender.

Mask series and gender

There was no difference in the distribution of mask series according to gender (see Additional file 4). However, there were significant differences in the distribution of mask series for each type of mask by gender (see Additional file 5). For NPM, there was a significant difference in Swift Fx® (51.1%) and Nuance pro® (31.2%) for men but no significant difference for women. For both women and men, Mirage Fx® and Swift Fx® were the most popular mask series for NM and NPM, respectively. For ONM, Simplus® was the most popular for women and Quattro® for men.

Mask related side-effects, CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence according to gender

Tables 2 and 3 summarize univariate and multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses evaluating the impact of explanatory variables on CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence according to gender. For women, in the model explaining CPAP-usage, the latter was independently associated with higher BMI, higher mean pressure, non-active smokers, higher VAS score for partner disturbing leaks and lower VAS score for dry mouth. In the model explaining CPAP-non-adherence, the latter was independently associated with only lower VAS score for partner disturbing leaks.

Table 2.

Univariate analyses by gender

| Variable | CPAP-usage (h/day) | CPAP-non-adherence (< 4 h/day) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N = 413 | Men, N = 1071 | Women, N = 413 | Men, N = 1071 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.01 | − 0.01, 0.03 | 0.205 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.03 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.97, 1.03 | 0.953 | 0.97 | 0.95, 0.99 | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.05 | 0.02, 0.08 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03, 0.07 | < 0.001 | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.00 | 0.075 | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.00 | 0.043 |

| Diagnostic AHI (events/h) | 0.01 | 0.00, 0.02 | 0.089 | 0.01 | 0.00, 0.02 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 | 0.680 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.264 |

| Active smokers | − 0.54 | − 1.11, 0.02 | 0.059 | 0.14 | − 0.19, 0.47 | 0.403 | 1.56 | 0.65, 3.74 | 0.320 | 1.63 | 0.85, 3.13 | 0.141 |

| Mustache | NA | NA | NA | − 0.05 | − 0.30, 0.20 | 0.706 | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | 0.57, 1.76 | 0.992 |

| Beard | NA | NA | NA | − 0.20 | − 0.48, 0.08 | 0.161 | NA | NA | NA | 0.86 | 0.44, 1.68 | 0.661 |

| Active workers | − 0.53 | − 0.98, − 0.07 | 0.025 | − 0.47 | − 0.73, − 0.21 | < 0.001 | 1.46 | 0.70, 3.05 | 0.311 | 1.71 | 0.99, 2.96 | 0.055 |

| Presence of partner | 0.28 | − 0.08, 0.63 | 0.128 | 0.11 | − 0.15, 0.38 | 0.395 | 0.72 | 0.38, 1.36 | 0.310 | 0.45 | 0.27, 0.76 | 0.003 |

| Epworth scale | ||||||||||||

| ESS (0–24 score) | − 0.09 | − 0.13, − 0.05 | < 0.001 | − 0.05 | − 0.07, − 0.02 | < 0.001 | 1.09 | 1.02, 1.16 | 0.007 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.10 | 0.144 |

| RES | − 0.84 | − 1.32, − 0.35 | < 0.001 | − 0.27 | − 0.56, 0.01 | 0.058 | 2.26 | 1.10, 4.66 | 0.027 | 1.29 | 0.70, 2.36 | 0.419 |

| Device | ||||||||||||

| Current AHIflow (events/h) | 0.04 | − 0.04, 0.11 | 0.355 | − 0.02 | − 0.04, 0.01 | 0.259 | 0.96 | 0.83, 1.12 | 0.621 | 1.07 | 1.02, 1.12 | 0.002 |

| Treatment duration (years) | 0.05 | 0.02, 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.06 | 0.04, 0.08 | < 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.89, 1.03 | 0.218 | 0.91 | 0.86, 0.96 | < 0.001 |

| Mean pressure (cmH2O) | 0.15 | 0.07, 0.23 | < 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.05, 0.15 | < 0.001 | 0.95 | 0.82, 1.10 | 0.496 | 0.93 | 0.83, 1.05 | 0.231 |

| 90th/95th pressure (cmH2O) | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.20 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 0.03, 0.13 | < 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.84, 1.11 | 0.588 | 0.94 | 0.84, 1.05 | 0.298 |

| Fixed pressure | 0.56 | − 0.03, 1.16 | 0.063 | 0.33 | 0.03, 0.64 | 0.031 | 0.62 | 0.18, 2.09 | 0.440 | 0.45 | 0.18, 1.15 | 0.095 |

| Comfort mode | − 0.34 | − 0.83, 0.14 | 0.166 | − 0.18 | − 0.47, 0.11 | 0.227 | 2.16 | 1.05, 4.45 | 0.036 | 1.11 | 0.58, 2.12 | 0.746 |

| Heated humidifier | − 0.42 | − 0.78, − 0.06 | 0.024 | − 0.23 | − 0.45, − 0.02 | 0.034 | 1.27 | 0.66, 2.45 | 0.472 | 1.49 | 0.89, 2.49 | 0.129 |

| Heated breathing tube | − 0.52 | − 1.24, 0.19 | 0.152 | − 0.17 | − 0.78, 0.45 | 0.600 | 1.02 | 0.30, 3.55 | 0.970 | 2.77 | 1.03, 7.44 | 0.043 |

| Mask | ||||||||||||

| Interface | 0.029 | 0.200 | 0.026 | 0.022 | ||||||||

| Nasal | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Nasal pillow | − 0.61 | − 1.07, − 0.15 | 0.010 | − 0.04 | − 0.34, 0.26 | 0.806 | 2.60 | 1.23, 5.50 | 0.012 | 1.64 | 0.83, 3.27 | 0.157 |

| Oronasal | − 0.30 | − 0.75, 0.14 | 0.180 | − 0.22 | − 0.45, 0.02 | 0.077 | 2.10 | 0.98, 4.49 | 0.055 | 2.12 | 1.23, 3.63 | 0.007 |

| Mask availability since 2013 | − 0.44 | − 0.80, − 0.08 | 0.016 | − 0.34 | − 0.55, − 0.12 | 0.002 | 1.57 | 0.84, 2.92 | 0.153 | 2.93 | 1.76, 4.88 | < 0.001 |

| Device reported leaks (0–100 score) | 0.00 | − 0.01, 0.01 | 0.685 | 0.00 | − 0.01, 0.01 | 0.863 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.374 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.610 |

| Side-effects (0–10 VAS score) | ||||||||||||

| Patient reported leaks | − 0.02 | − 0.08, 0.04 | 0.458 | 0.01 | − 0.03, 0.05 | 0.611 | 1.00 | 0.91, 1.11 | 0.942 | 1.01 | 0.93, 1.09 | 0.902 |

| Partner disturbing leaks | 0.05 | − 0.01, 0.11 | 0.079 | 0.02 | − 0.01, 0.05 | 0.262 | 0.80 | 0.68, 0.94 | 0.007 | 0.93 | 0.86, 1.00 | 0.067 |

| Noisy mask | − 0.03 | − 0.10, 0.04 | 0.350 | 0.00 | − 0.05, 0.04 | 0.817 | 1.06 | 0.95, 1.19 | 0.291 | 0.97 | 0.88, 1.07 | 0.513 |

| Heavy mask | − 0.08 | − 0.19, 0.02 | 0.102 | − 0.04 | − 0.11, 0.02 | 0.194 | 1.00 | 0.83, 1.19 | 0.966 | 0.92 | 0.77, 1.09 | 0.310 |

| Mask pain | − 0.07 | − 0.16, 0.02 | 0.119 | − 0.01 | − 0.07, 0.05 | 0.678 | 1.08 | 0.94, 1.24 | 0.285 | 1.06 | 0.94, 1.20 | 0.311 |

| Mask injury | − 0.01 | − 0.09, 0.07 | 0.772 | 0.05 | − 0.01, 0.12 | 0.107 | 1.03 | 0.90, 1.17 | 0.702 | 0.98 | 0.84, 1.14 | 0.783 |

| Harness pain | − 0.03 | − 0.13, 0.07 | 0.522 | − 0.01 | − 0.08, 0.06 | 0.882 | 1.05 | 0.90, 1.22 | 0.560 | 1.11 | 0.97, 1.26 | 0.119 |

| Harness injury | 0.01 | − 0.12, 0.14 | 0.887 | 0.09 | 0.01, 0.17 | 0.020 | 1.05 | 0.86, 1.28 | 0.658 | 0.88 | 0.69, 1.12 | 0.293 |

| Red eyes | 0.04 | − 0.03, 0.11 | 0.235 | 0.03 | − 0.01, 0.07 | 0.159 | 0.96 | 0.85, 1.09 | 0.554 | 1.04 | 0.94, 1.14 | 0.450 |

| Itchy eyes | 0.03 | − 0.03, 0.10 | 0.300 | 0.04 | 0.00, 0.09 | 0.051 | 1.01 | 0.89, 1.13 | 0.929 | 0.98 | 0.88, 1.10 | 0.773 |

| Dry nose | − 0.05 | − 0.10, 0.00 | 0.069 | − 0.06 | − 0.09, − 0.03 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.90, 1.10 | 0.928 | 1.04 | 0.96, 1.12 | 0.308 |

| Stuffed nose | − 0.06 | − 0.12, 0.00 | 0.034 | − 0.02 | − 0.06, 0.02 | 0.397 | 1.02 | 0.92, 1.13 | 0.668 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.09 | 0.904 |

| Runny nose | 0.01 | − 0.06, 0.08 | 0.719 | 0.02 | − 0.02, 0.06 | 0.298 | 0.99 | 0.87, 1.12 | 0.883 | 0.97 | 0.88, 1.07 | 0.586 |

| Dry mouth | − 0.05 | − 0.10, 0.00 | 0.043 | − 0.03 | − 0.06, 0.00 | 0.090 | 1.04 | 0.95, 1.12 | 0.409 | 1.06 | 0.99, 1.13 | 0.092 |

| Number* [0/14] | − 0.03 | − 0.08, 0.01 | 0.150 | − 0.01 | − 0.03, 0.02 | 0.500 | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.10 | 0.667 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.07 | 0.632 |

Bolds variables are statistically significant at the 5% threshold. Italics variables are included in multivariable analyses.*Number of side effects; dichotomous data created when the VAS scale for the side effect was above or equal to 1. This variable was not included in the multivariable analyses because of its collinearity with MRSE-variables

AHI: Apnea–hypopnea Index; AHIflow: AHI reported by device; BMI: body mass index; CI: Exact Confidence Interval; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; NA: not applicable; OR: Odds Ratio; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale

Table 3.

Multivariable regressions for CPAP-usage and CPAP-non-adherence as variables-of-interest, summary of significant explanatory-variables including side-effects

| Variable | CPAP-usage (h/day) | CPAP-non-adherence (< 4 h/day) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, N = 413 | Men, N = 1071 | Women, N = 413 | Men, N = 1071 | |||||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.03 | < 0.001 | 0.96 | 0.93, 0.98 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.07 | 0.016 | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.07 | < 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.88, 0.99 | 0.015 | |||

| Active smokers | − 0.89 | − 1.50, − 0.27 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| Presence of partner | 0.43 | 0.24, 0.77 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| Epworth scale | ||||||||||||

| ESS (0–24 score) | − 0.04 | − 0.07, − 0.02 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Device | ||||||||||||

| Current AHIflow (events/h) | 1.08 | 1.03, 1.14 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Treatment duration (years) | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.06 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Mean pressure (cmH2O) | 0.16 | 0.06, 0.25 | 0.002 | |||||||||

| 90th/95th pressure (cmH2O) | 0.05 | 0.00, 0.11 | 0.034 | |||||||||

| Mask | ||||||||||||

| Mask availability since 2013 | − 0.30 | − 0.53, − 0.07 | 0.009 | 2.72 | 1.56, 4.74 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Side-effects | ||||||||||||

| Partner disturbing leaks (0–10 VAS score) | 0.07 | 0.01, 0.13 | 0.026 | 0.80 | 0.68, 0.94 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Harness injury (0–10 VAS score) | 0.13 | 0.04, 0.21 | 0.003 | |||||||||

| Dry nose (0–10 VAS score) | − 0.06 | − 0.09, − 0.02 | 0.004 | |||||||||

| Dry mouth (0–10 VAS score) | − 0.10 | − 0.15, − 0.04 | < 0.001 | 1.08 | 1.00, 1.16 | 0.050 | ||||||

Note that for models, explanatory-variables with a p-value < 0.15 at the univariate level were fed into multivariable analyses using stepwise selection. A backward elimination was then applied and only explanatory-variables with a p-value < 0.05 at the multivariable level remain in the definitive models. Bolds variables are statistically significant at the 5% threshold

AHI: Apnea–Hypopnea Index; AHIflow: AHI reported by device; BMI: body mass index; CI: exact confidence interval; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; ESS: epworth sleepiness scale; OR: odds ratio; VAS: visual analogue scale.

For men, in the model explaining CPAP-usage, the latter was independently associated with higher age, BMI, treatment duration, p90/95th pressure, lower ESS score, availability of the mask before 2013, higher VAS score for harness injury, and lower VAS score for dry nose. In the model explaining CPAP-non-adherence, the latter was independently associated with lower age and BMI, living alone, higher current AHIflow, availability of the mask after 2013, and higher VAS score for dry mouth.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report, in a large cohort of patients treated with long-term CPAP, the gender-specific prevalence of several MRSEs and their impact on CPAP-usage and non-adherence. The main results reported here suggest that: 1) there are disparities in MRSEs according to gender and mask type; 2) different MRSEs are independently associated with CPAP-usage and non-adherence according to gender.

External validity of our study

In a 2021 narrative review, Bouloukaki et al. estimated the men-women ratio for sleep apnea syndrome to be 1.5:1 (i.e., 40% women) [13]. In our study, 27.8% of the patients are women. This is comparable to the prevalence of 32.3% recently published in a study by Prigent et al., which involved 25,846 patients in France receiving identical care [16]. However, our prevalence of women is higher than that of the ISAACC cohort (16.5%) and lower than the prevalence in the PLSC (39% women) and HynoLauss (53% women) cohorts [17]. Importantly, the characteristics of our population of women are comparable to those reported in the literature, with a lower quality of life (including more symptoms of depression), more obesity, less severe initial SAS, and less CPAP-adherence than men [11–14, 18].

Mask related side‑effects depending on gender

The study identified only three MRSEs (dry mouth, runny nose and mask injury) that differed between men and women, with only mask injury potentially justifying the design of a gender-specific mask.

Dry mouth is a MRSE known to be associated with a decrease in CPAP-adherence (Bachour and Maasilta, 2004; Rotty et al., 2021). For NPMs, the median MRSE VAS score for dry mouth was significantly higher in women, and the use of heated breathing tubes was significantly elevated in this group. Similar trends were observed for NMs and ONMs, but did not reach significance,. This observation is of crucial importance considering that future NPM designs cannot directly mitigate this side effect, and interventions by technicians or patients, such as the use of heated humidifiers and heated breathing tubes, should be considered to limit dry mouth. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis has reported the efficacy of heated humidifiers in addressing dry mouth (Hu et al., 2023), and the use of heated humidifiers is recommended with a moderate quality of evidence (Patil et al., 2019a; Patil et al., 2019b).

For ONMs, the median MRSE VAS score for runny nose was significantly higher in men. In a previous study, runny nose was associated with residual excessive sleepiness (RES, defined as an Epworth-Sleepiness-Scale score of ≥ 11), but not CPAP-adherence, in univariate analysis [15]. To mitigate this side effect, the use of heated humidifiers and/or topical steroids are proposed, but the quality of evidence is low [4, 5].

The prevalence of patient-reported mask injury was higher in women than in men. In a previous study, we found that mask injury was associated with RES, but not CPAP-adherence, in univariate analysis [15]. If masks specifically dedicated to women are developed in the future, they should take these gender specificities into account.

In accordance with the findings of previous studies [19, 20], our study observed that patient-reported leaks were the most prevalent MRSE, but no gender differences in prevalence were found.

Factors influencing CPAP-adherence depending on gender

In line with previous long term cohort studies, we reported that: i) for both women and men, BMI was independently and positively associated with CPAP-adherence [21]; ii) for men, the presence of a partner was positively and independently associated with CPAP-adherence [21]; iii) for men, treatment duration and age were also independently and positively associated with CPAP-usage [18]. Partner disturbing leaks, for women, and harness injury, for men, were positively associated with CPAP-usage and CPAP-adherence. We observe these results as an association and not as a cause, since prolonged CPAP-usage increases the risk of mask-related injuries in patients and potentially causes discomfort for their partners, particularly in cases where sleep disturbances arise from noisy air leaks or skin irritation due to leak exposure.

Study limitations

The long-term design of our study serves as both a strength and a limitation. Patients may have been treated with various mask series and mask types prior to inclusion. Therefore, we cannot ascertain whether the prevalence of different masks or MRSEs was influenced by different mask sequences. Furthermore, it is important to keep in mind that since our patients were treated with long-term CPAP our observations are not validated for patients treated with short-term CPAP.

Patients were enrolled in the study from February 7, 2017, to April 1, 2019. This is also a strength and a limitation. It is a strength because the women in the cohort received the same treatment as the men, as none of the women used masks specifically designed for women, such as the “for her” series by ResMed. However, it is a limitation because only 17% of the patients were treated with NPM, despite the increasing use of this type of mask [22, 23]. Furthermore, recent minimal contact masks, which are now available, were not used in our study, representing another limitation.

The lack of data on comorbidities, as other diseases and medications may impact the probability of MRSE. Additionally, in men, the presence of a beard may be a factor affecting MRSEs.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing long-term CPAP therapy, gender differences in MRSEs have been observed. The study identified three MRSEs that differed between men and women, with only one potentially justifying the creation of a gender-specific mask. Women were more affected by dry mouth with NPMs, and men by runny nose with ONMs; however, these side effects cannot be directly addressed in future mask designs. On the other hand, the higher incidence of mask injuries reported by women could guide the development of masks specifically designed for them. In the context of personalized medicine, our results suggest that future mask designs should take these gender differences into account when developing masks specifically for women. Nonetheless, our study highlights that only dry mouth, a side effect not related to mask design, impacts CPAP-usage and non-adherence.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Apard team for their help in carrying out this study (administrative Team: Pierre Coulot, Bernard Alsina, Valérie Bachelier, Christophe Jeanjean, Philippe Lansard, Joël Nogue, Magali Partyka; technician team: Matthieu Alberti, Julien Bauchu, Yannick Baudelot, Gregory Bel, Julien Bernard, Julien Bourrel, Frédéric Bousquet, David Crespy, Olivier Cubero, Eric Deghal, Fabien Deville, Sébastien Faure, Laure Ferraz, Olivier Gaubert, Georges Guichard, Franck Issert, Renaud Lopez, Mounia Maachou, Clément Maurin, David Minguez, Fabien Moubeche, Christophe Pinotti, Liva Ranaivo, Lazhar Saighi, Frédéric Sola, Frédéric Tallavignes, Olivier Tramier, Jean-Michel Tribe, Jean-Marc Uriol, Romain Vernet). The authors would like to thank Dr Sarah Skinner for editing the article.

Abbreviations

- AHI

Apnea–Hypopnea-Index

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CPAP

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FSS

French Social Security

- MRSEs

Mask related side-effects

- NM

Nasal mask

- NPM

Nasal pillow mask

- ONM

Oronasal mask

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- QoL

Quality of life

- RES

Residual excessive sleepiness

- SAS

Sleep apnea syndrome

- VAS

Visual analogue scales

Author contributions

DJ accessed all data and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the analysis. All authors contributed to and approved the final submitted manuscript. CV: data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation; FB: data collection; JPM: study design analysis and manuscript preparation; RG: data collection and analysis; JCB: manuscript preparation; FG: manuscript preparation; AB: study design, analysis and manuscript preparation; NM: study design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation; DJ: study design, analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

InterfaceVent is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03013283). The protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Mediterranée 1; reference number RO-2016/50). All participants had given their written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

CV declares working for Adene home healthcare provider company. JPM declares grants/funds: Adene, Novartis, Chiesy, GSK, DPC-ORL; personal fees from Pulmon X. RG declares working for Adene home healthcare provider company. JCB declares consultant fees from AGIR à dom, a French Homecare provider. FG declares receipt of personal fees from AIR LIQUIDE SANTE, INSPIRE, BIOPROJET, RESMED and SEFAM; payment for presentations from BIOPROJET, CIDELEC, INSPIRE, RESMED, and SEFAM; non-financial support from ASTEN SANTE. AB declares grants/funds: Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi-Regeneron; clinical trial investigator: Acceleron, Actelion, Galapagos, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Nuvaira, Pulmonx, United Therapeutic, Celltrion, Vertex. NM declares grants/funds: GlaxoSmithKline; personal fees: Sanofi-Regeneron. DJ reports personal fees from Lowenstein, Jazz, Bioprojet, Adene, Bastide, LVL, GSK, Astra, ALK, Bohringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Philips Healthcare, and Resmed, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Sefam and Nomics, grants and personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:687–98. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinzer R, Marti-Soler H, Haba-Rubio J. Prevalence of sleep apnoea syndrome in the middle to old age general population. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:e5-6. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00006-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randerath W, Verbraecken J, de Raaff CAL, Hedner J, Herkenrath S, Hohenhorst W, et al. European Respiratory Society guideline on non-CPAP therapies for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30: 210200. 10.1183/16000617.0200-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil SP, Ayappa IA, Caples SM, Kimoff RJ, Patel SR, Harrod CG. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an american academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15:335–43. 10.5664/jcsm.7640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil SP, Ayappa IA, Caples SM, Kimoff RJ, Patel SR, Harrod CG. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an american academy of sleep medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15:301–34. 10.5664/jcsm.7638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, Anderson CS, Rodgers A, Perkovic V, et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318:156–66. 10.1001/jama.2017.7967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, Bloxham T, George CFP, Greenberg H, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–9. 10.1093/sleep/30.6.711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gervès-Pinquié C, Bailly S, Goupil F, Pigeanne T, Launois S, Leclair-Visonneau L, et al. Positive airway pressure adherence, mortality, and cardiovascular events in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:1393–404. 10.1164/rccm.202202-0366OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azarbarzin A, Zinchuk A, Wellman A, Labarca G, Vena D, Gell L, et al. Cardiovascular benefit of continuous positive airway pressure in adults with coronary artery disease and obstructive sleep apnea without excessive sleepiness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:767–74. 10.1164/rccm.202111-2608OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bublitz M, Adra N, Hijazi L, Shaib F, Attarian H, Bourjeily G. A narrative review of sex and gender differences in sleep disordered breathing: gaps and opportunities. Life. 2022;12:2003. 10.3390/life12122003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-García MÁ, Sierra-Párraga JM, Garcia-Ortega AA. Obstructive sleep apnea in women: we can do more and better. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;64: 101645. 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel SR, Bakker JP, Stitt CJ, Aloia MS, Nouraie SM. Age and sex disparities in adherence to CPAP. Chest. 2021;159:382–9. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouloukaki I, Tsiligianni I, Schiza S. Evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea in female patients in primary care: time for improvement? Med Princ Pract. 2021;30:508–14. 10.1159/000518932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-García MÁ, Labarca G. Obstructive sleep apnea in women: scientific evidence is urgently needed. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18:1–2. 10.5664/jcsm.9684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotty M-C, Suehs CM, Mallet J-P, Martinez C, Borel J-C, Rabec C, et al. Mask side-effects in long-term CPAP-patients impact adherence and sleepiness: the InterfaceVent real-life study. Respir Res. 2021;22:17. 10.1186/s12931-021-01618-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prigent A, Blanloeil C, Jaffuel D, Serandour AL, Barlet F, Gagnadoux F. Seasonal changes in positive airway pressure adherence. Front Med. 2024;11:1302431. 10.3389/fmed.2024.1302431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solelhac G, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, Blanchard M, Berger M, Hirotsu C, Imler T, et al. Pulse wave amplitude drops index: a biomarker of cardiovascular risk in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207:1620–32. 10.1164/rccm.202206-1223OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prigent A, Blanloeil C, Serandour A-L, Barlet F, Gagnadoux F, Jaffuel D. A biphasic effect of age on CPAP adherence: a cross-sectional study of 26,343 patients. Respir Res. 2023;24:234. 10.1186/s12931-023-02543-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachour A, Vitikainen P, Virkkula P, Maasilta P. CPAP interface: satisfaction and side effects. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:667–72. 10.1007/s11325-012-0740-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borel JC, Tamisier R, Dias-Domingos S, Sapene M, Martin F, Stach B, et al. Type of mask may impact on continuous positive airway pressure adherence in apneic patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e64382. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagnadoux F, Le Vaillant M, Goupil F, Pigeanne T, Chollet S, Masson P, et al. Influence of marital status and employment status on long-term adherence with continuous positive airway pressure in sleep apnea patients. PLoS ONE. 2011;6: e22503. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laaka A, Hollmén M, Bachour A. Evaluation of CPAP mask performance during 3 years of mask usage: time for reconsideration of renewal policies? BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8: e001104. 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zonato AI, Rosa CFA, Oliveira L, Bittencourt L. Comparing CPAP masks during initial titration for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: 1 year experience. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;88(Suppl 5):S63–8. 10.1016/j.bjorl.2021.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.