Abstract

Background

Chlorpromazine, one of the first generation of antipsychotic drugs, is effective in the treatment of schizophrenia. For most people schizophrenia is a life‐long disorder but about a quarter of those who have a first psychotic breakdown do not go on to experience further breakdowns. Most people with schizophrenia are prescribed antipsychotic drugs, although use is often intermittent. The effects of stopping medication are not well researched in the context of systematic reviews.

Objectives

To quantify the effects of stopping chlorpromazine for people with schizophrenia stable on this drug.

Search methods

We supplemented an electronic search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2006 and July 2012) with reference searching of all identified studies.

Selection criteria

We included all relevant randomised clinical trials.

Data collection and analysis

We independently inspected citations and abstracts, ordered papers and re‐inspected and quality assessed these. We independently extracted data and resolved disputes during regular meetings. We analysed dichotomous data using fixed effects relative risk (RR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, where possible, we calculated the weighted mean difference (WMD). We excluded the data where more than 40% of people were lost to follow up.

Main results

We included ten trials involving 1042 people with schizophrenia stable on chlorpromazine. Even in the short term, those who remained on chlorpromazine were less likely to experience a relapse compared to people who stopped taking chlorpromazine (n=376, 3 RCTs, RR 6.76 CI 3.37 to 13.54, NNH NNH 4 CI 2 to 8). Medium term (n=850, 6 RCTs, RR 4.04 CI 2.81 to 5.8, NNH 4 CI 3 to 7) and long term data were similar (n=510, 3 RCTs, RR 1.70 CI 1.44 to 2.01, NNH 4 CI 3 to 6). People allocated to chlorpromazine withdrawal were not significantly more likely to stay in the study compared with those continuing chlorpromazine treatment (n=374, 1 RCT, RR 1.14 CI 0.55 to 2.35). In sensitivity analyses, there was a significant difference in the 'relapse' outcome between trials for those diagnosed according to checklist criteria compared to those with a clinical diagnosis.

Authors' conclusions

This review confirms clinical experience and quantifies the risks of stopping chlorpromazine medication for a group of people with schizophrenia who are stable on this drug. With its moderate adverse effects, chlorpromazine is likely to remain one of the most widely prescribed treatments for schizophrenia.

Keywords: Humans, Withholding Treatment, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/administration & dosage, Chlorpromazine, Chlorpromazine/administration & dosage, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Cessation of medication for people with schizophrenia already stable on chlorpromazine

The course of schizophrenia can be varied with some people experiencing a single episode of psychosis while others suffer repeated episodes. Often people with schizophrenia want to stop treatment with chlorpromazine once symptoms have subsided. This review highlights the risks of stopping chlorpromazine for those with established illness. Halting medication with chlorpromazine increases the risk of relapse over all time periods. Relapses are damaging and can be dangerous.

Background

The efficacy of chlorpromazine and other phenothiazine derivatives in treating acute episodes of schizophrenia has long been demonstrated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (e.g. NIMH 1964). The importance of maintenance drug therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia has been evident since the early 1960s. Initial studies indicated that about a half to two thirds of patients with schizophrenia who were stable on medication relapsed following cessation of maintenance pharmacological therapy, compared with between five and 30% of the patients maintained on medication (Caffey 1964, Davis 1975). A review of 66 studies performed between 1985 and 1993 demonstrated that medication cessation was associated with a 53.2% relapse rate within 6.3 to 9.7 months compared with 15.6% within 7.9 months in the maintenance groups (Gilbetr 1995). Thus, findings from medication discontinuation studies have conclusively shown that, as a group, patients with schizophrenia fare better if they receive antipsychotic medication than no medication whatsoever.

Although schizophrenia is generally thought to be a life‐long disorder requiring indefinite pharmacological treatment, prolonged use of antipsychotic medication carries the risk of adverse effects, and few people want to take medication for months and often years, least of all the population most commonly hit by new episodes of schizophrenia, those in their late teens or early 20s.

The course of schizophrenia varies, and may follow one of four patterns (Shepherd 1989); 13% may have a single episode with no subsequent impairment, 30% may have several episodes with no or minimal impairment, 10% may suffer impairment following the first episode with occasional exacerbation of symptoms and no return to normality, and 47% show impairment increasing after each exacerbation. Presently, it is not possible to predict the course of an illness. Medication cessation studies may help identify the characteristics of those patients who will have a single episode and not require maintenance drug treatment. Such studies may also help identify those who will follow a relapsing course and may benefit from intermittent treatment, and those who require indefinite maintenance drug treatment.

The clinician is left with a dilemma. Most people probably should take medication for longer than they want to, yet the epidemiology tells clinicians that some patients will be able to avoid taking these powerful medications in the long term. Evidence for the efficacy of medication is plentiful and often supported by industry funding. Cessation trials are not in the interest of industry to undertake, and appear less common. Nevertheless, this latter type of study does ask an important question. Certainly, follow up (Curson 1985) and audit (Essali 1993) studies of people on long acting injectable antipsychotics who stop medication do strongly suggest that, for this group at least, cessation is inadvisable. In this review we aimed to investigate the quantitative effects of stopping chlorpromazine for people stable on this drug by reviewing available trial‐based evidence.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of stopping chlorpromazine therapy in people with schizophrenia stable on chlorpromazine.

It is expected that several sensitivity analyses could be undertaken within this review. The following hypotheses will be tested:

When compared with placebo, for the primary outcomes of interest (see: 'Criteria' for considering studies for this review) chlorpromazine cessation is differentially effective for: 1. Men and women. 2. People who are under 18 years of age, between 18 and 64, or over 65 years of age. 3. People who became ill recently (i.e. acute episode approximately less than one month's duration) as opposed to people who have been ill for longer period. 4. People who are given low doses (1‐ 500 mg/day), and those given high doses (over 501 mg/day). 5. People who have schizophrenia diagnosed according to any operational criterion i.e. a pre‐stated checklist of symptoms/problems/time periods/exclusions) as opposed to those who have entered the trial with loosely defined illness. 6. People treated earlier (pre‐1990) and people treated in recent years (1990 to 2006).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised controlled trials. We included trials described as 'double‐blind' if it was implied that the study was randomised and we included these in a sensitivity analysis. If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they remained in the analyses. If their inclusion did result in statistically significant differences, we did not add the data from these lower quality studies to the results of the better trials, but presented these within a subcategory. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia‐like psychoses (schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders). There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994).

Types of interventions

1. Placebo: (active or inactive) or no treatment. 2. Chlorpromazine: any dose or mode of administration (oral or by injection).

Types of outcome measures

1. General 1.1 Global state improvement* 1.2 Relapse ‐ as defined by each study* 1.3 Leaving the study early 1.4 Death (suicide and non‐suicide

2. Mental state 2.1 General symptoms 2.2 Specific symptoms 2.2.1 Positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking) 2.2.2 Negative symptoms (avolition, poor self‐care, blunted affect) 2.2.3 Mood ‐ depression

3. Behaviour 3.1 General behaviour 3.2 Specific behaviours (e.g. aggressive or violent behaviour) 3.2.1 Social functioning 3.2.2 Employment status during trial (employed/unemployed) 3.2.3 Occurrence of violent incidents (to self, others or property)

4. Adverse effects

5. Economic 5.1 Cost of care.

* We chose relapse and global state improvement (as defined in the individual studies) as the primary outcome measures.

We grouped outcomes into the short term (0‐8 weeks), medium term (eight weeks to six months) and long term (six months to two years)

Search methods for identification of studies

1. Electronic searches We searched The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (March 2006) using the phrase: [(((anadep* or chloractil* or chlorazin* or chlorpromados* or chlorpromazine* or chlorprom‐ez‐ets* or (chlor p‐z)* or chromedazine* or cpz* or elmarine* or esmind* or fenactil* or hibanil* or hibernal* or klorazin* or klorproman* or klorpromez* or largactil* or megaphen* or neurazine* or plegomazine* or procalm* or promachel* or promacid* or promapar* or promexin* or promosol* or prozil* or psychozine* or psylactil* or serazone* or sonazine* or thoradex* or thorazine* or tranzine*) AND (cessation* or withdr?w* or discontinu* or halt* or stop* or drop?out* or dropout*)) in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or ((chlorpromazine* and withdrawal*) in interventions of STUDY)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

1. 1 Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (July 2012)

[(((*anadep* or *chlora* or *chlorprom* or *chlor p‐z* or *chromedazine* or *cpz* or *elmarine* or *esmind* or *fenactil* or *hibanil* or *hibernal* or *klorazin* or *klorproman* or *klorpromez* or *largactil* or *megaphen* or *neurazine* or *plegomazine* or *procalm* or *promachel* or *promacid* or * proma* or *promexin* or *promosol* or *prozil* or *psychozine* or *psylactil* or *serazone* or *sonazine* or *thoradex* or *thorazine* or *tranzine*) AND (*cessation* or *withdr?w* or *discontinu* or * halt* or * stop* or *drop?out* or *dropout*)) in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE) or ((*chlorpromazine* and *withdrawal*) in interventions of STUDY)]

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to existing or new review titles.

2. Reference searching We inspected the references of all identified studies for further trials.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials We (MQM, ER, HA and HEM) independently inspected references located through electronic or reference searches in order to identify randomised trials meeting the inclusion criteria. Where disagreement occurred we resolved this by discussion, or, when there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, we (MQM, HEM) independently decided whether they met review criteria. Once again, disagreement was resolved by discussion. If doubt remained, we added the study to the list of those awaiting assessment, pending acquisition of more information.

2. Assessment of methodological quality The methodological quality of trials was assessed using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005). These criteria are based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect (Schulz 1995), and define the following categories:

A. Low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment) B. Moderate risk of bias (some doubt about the results) C. High risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment). Only trials falling in category A or category B were included in this review.

3. Data collection We (MQM, ER, HA and HEM) independently extracted data from selected trials and held regular meetings during the data extraction period and resolved disputes by discussion.

4. Data synthesis

4.1 Data types We assessed outcomes using continuous (for example changes on a behaviour scale) or dichotomous (for example, either 'no important changes' or 'important changes' in a person's behaviour) measures. Included studies reported no categorical measures (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as 'little change', 'moderate change' or 'much change').

4.2 Incomplete data We did not include trial outcomes if more than 40% of participants were not reported in the final analysis.

4.3 Dichotomous ‐ yes/no ‐ data On the condition that more than 60% of people completed the study, everyone allocated to the intervention was counted whether they completed the follow up or not. We conducted an intention to treat analysis assuming that those who dropped out had the negative outcome, with the exception of death. Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. We used those predefined cut off points used by the authors of every study determining clinical effectiveness. Otherwise we considered a rating of 'at least much improved' according to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (Guy 1976), or a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score, a clinically significant response.

We calculated the relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) because RR has been shown to be more intuitive than odds ratios (Boissel 1999) and odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation may lead to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. We calculated RR and its 95% CI based on a fixed effects model.

4.4 Continuous data 4.4.1 Normally distributed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we multiplied the standard deviation for scales starting from zero by two, and if the result was more than the mean, we considered the mean unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, (Altman 1996). If a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

4.4.2 Rating scales: A wide range of instruments is available to measure mental health outcomes. These instruments vary in quality and many are not valid, or even ad hoc. For outcome instruments some minimum standards have to be set. We only included continuous data from rating scales if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000), the instrument was either a self report or completed by a rater, and the instrument could be considered a global assessment of an area of functioning. However, as it was expected that therapists would frequently also be the rater, we commented on such data as 'prone to bias'.

4.4.3 Summary statistic For continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups, again based on a fixed effects model.

4.5 Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999). In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for these using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for these using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

5. Investigation for heterogeneity We judged clinical heterogeneity within all comparisons between included studies, and visually inspected graphs in order to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented by the I‐squared statistic which provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than to chance alone. An I‐squared estimate equal to or greater than or equal to 75% indicates the presence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

6. Sensitivity analyses We attempted to test the effects of gender, age, diagnostic criteria and date of publication on the primary outcome of relapse.

7. General Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for chlorpromazine.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of the studies please see Included and Excluded Studies tables.

1. Excluded studies We excluded 29 studies; three were not randomised and 19 trials did not involve withdrawal of chlorpromazine. However, three studies did include withdrawal of chlorpromazine but reported no usable outcomes. Four other studies, employed different phenothiazines, one of which was chlorpromazine, but outcome data were not broken down between the different compounds.

2. Awaiting assessment There are no studies awaiting assessment.

3. Ongoing studies We know of no ongoing studies.

4. Included studies We included ten studies.

4.1 Methods In all included studies, randomisation was either reported or implied. The mean duration of intervention was 294 days (˜ten months), but this was highly skewed (SD 299 days). The most common study length was six months but the range was wide; with the shortest trial lasting for one month (Zeller 1956) and the longest for three years (Hogarty 1973 a).

4.2 Setting Most studies were hospital‐based. Only Hogarty 1973 a was undertaken in the community.

4.3 Participants Participants in most trials were reportedly suffering from schizophrenia, with two exceptions; people in Zeller 1956 were "psychotic patients", and Freeman 1962 included a few people with chronic brain syndrome and personality disorders as well as those with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia was diagnosed using some diagnostic criteria or pre‐stated set of symptoms in only a few trials. The mean age of participants was about 44 yrs (˜SD 7), and their illness were mostly chronic with mean hospitalisation period of about 20 years. Six studies involved only male participants (three studies did not mention the sex of participants, Mathur 1981, Shawver 1959, Zeller 1956). Overall the male to female ratio was about 3:1 (M 630, F 217).

4.4 Study size The total number of participants was 1024 (mean 104, SD˜121). This ranged from 20 (Pigache 1973) to 374 (Hogarty 1973 a).

4.5 Interventions All participants were people with schizophrenia stable on chlorpromazine medication and randomised into two groups. Chlorpromazine was discontinued for the first group and replaced with placebo. The second group continued to receive chlorpromazine at different doses ranging from 100 mg/day (Caffey 1964) to 510 mg/day (Greenberg 1966). The mean dose was 270mg/day with (SD˜135).

4.6 Outcomes All outcomes were dichotomous and but several scales described below were used to generate these data.

4.7.1 Global state 4.7.1.1 Clinical Global Impression (Guy 1976) A rating instrument commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery.

4.7.1.2 Multidimensional Rating Scale (Lorr 1953) The Multidimensional Rating Scale or Hamilton's schizophrenia scale is a modification of the Inpatient Multidimensional Psychiatric Scale. The MDRSP is to be completed after a psychiatric interview. It consists of 18 items, in the form of simple questions, to be rated along a four point scale. The severity scores are defined by short behavioural descriptions on the form, thus avoiding interpretation problems. The scale is mainly designed for the evaluation of chronically hospitalised schizophrenic patients.

4.7.2 Mental state 4.7.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (Overall 1962) A brief rating scale used to assess the severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The original scale has sixteen items, but a revised eighteen‐item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', scoring from 0‐6 or 1‐7. Scores can range from 0‐126, with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

4.7.2.2 Wing Scale (Wing 1961) The Wing scale has been successful in detecting the efficacy of antipsychotic drugs. The SRSS is a simple four item rating scale: 1) incongruity of affect, 2) poverty of speech, 3) incoherence of speech and 4) coherent delusions. In spite of the availability of definitions and examples, the items remain a bit vague. The SRSS's original purpose was to classify subjects, and, although it cannot be used for diagnosis, as the items are taken from the key symptoms of the disease in the rather strict sense in which it is defined in placeEurope, a high score would support a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Training is probably necessary, as it is for the use of any scale based on the typical experiences of schizophrenics which are not as easily open to empathy as are the emotions of depressed or anxious patients. The interview format is free and, for an experienced rater, the time to complete the SRSS after the interview is less than a minute.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation None of the included studies described the methods used to generate random allocation. A form of allocation concealment (sealed envelopes) was described in only one study (Pigache 1973). For the other studies, readers are given little assurance that bias was minimised during the allocation procedure. Five (5/10) studies reported that the participants allocated to each treatment group were very similar. Five (5/10) studies had exactly the same number of participants in the chlorpromazine and placebo groups, yet only Shawver 1959 reported that participants were randomly assigned in blocks. It seems improbable that such equal numbers could have been obtained in the remaining four studies unless block randomisation was used.

2. Blindness Six of the ten included trials described a double‐blinding procedure; four indicated that attempts at blinding had been made but gave no description of such attempts, and a single study, Mathur 1981, gave no indication that blinding had been attempted.

3. Early withdrawals Interestingly, the description of those who left the studies early was very poor. Only three studies reported early withdrawals yet they gave little or no details of why people left the studies early.

4. Outcome reporting Studies frequently presented both dichotomous and continuous data in graphs. Sometimes, just statistical measures of probability (p‐values) were reported making it impossible to acquire raw data for synthesis. It was also common to use p‐values as a measure of association between intervention and outcomes instead of showing the strength of the association. Although p‐values are influenced by the strength of the association, they also depend on the sample size of the groups. Although raw data may be extracted from p‐values if the exact p‐values were known, this extraction was not possible in the studies included in this review because p‐values were reported as 'p<0.05' or 'p>0.05'. Frequently continuous data were poorly described: often no standard deviations/errors were presented or no data were presented at all. In this way a lot of potentially informative data were lost. Some studies attempted at using the original trials as vehicles for answering a host of questions about schizophrenia. As a consequence, data from the randomised parts of the studies became buried beneath copious subgroup analyses.

5. Overall quality The quality of trials, as measured using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2005), varied. Inclusions in this review necessitated at least a Category B on the Cochrane Handbook rating of allocation. As we considered nine studies to be in category 'B' whilst only one study achieved Category A status, some data must be considered to be prone to a moderate degree of bias.

Effects of interventions

1. The search, trial selection and data extraction The searches yielded 60 electronic records, of which 20 were easily rejected after first inspection. The other 40 papers were considered to match the inclusion criteria closely enough to be mentioned in either the 'Included studies' or 'Excluded studies' section. During the data extraction process, we inspected the references of these papers and identified nine more papers as being relevant.

The review currently cites 31 papers as 'excluded studies' and 18 papers as included. There was over 80% agreement for trial selection and once we had investigated disagreement, acquired and re‐inspected papers, concordance became 100%. Initially there was also over 80% agreement in all but 'numbers completing the study' (70%) and listing of outcome instruments. For the latter, in about one fifth of reports, we often failed to identify the same number of scales, often when several had been used.

2. COMPARISON: CHLROPROMAZINE WITHDRAWAL vs CONTINUING ON CHLORPROMAZINE

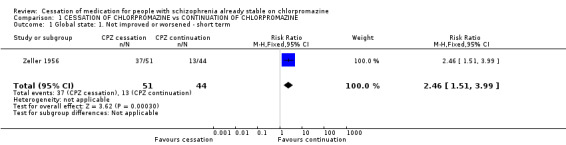

2.1 Global state 2.1.1 Not improved or worsened Only Zeller 1956 reported usable data regarding global state improvement at short‐term follow‐up (n=95, 1 RCT, RR 2.46 CI 1.51 to 3.99, NNH 3 CI 2) favouring chlorpromazine continuation.

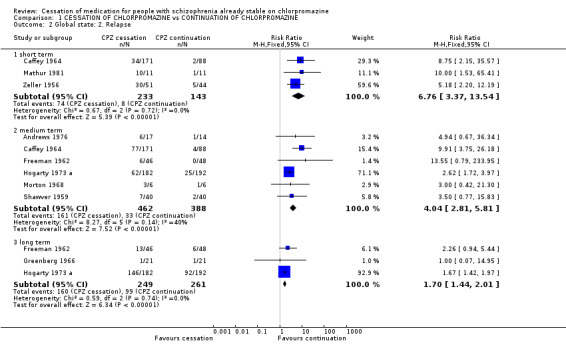

2.1.2 Relapse The data for this primary outcome were extracted and sorted into short, medium and long‐term relapse. The results are homogeneous (p=0.36, 0.13, 0.46 respectively) and overall data significantly favoured chlorpromazine continuation. In the short term three trials presented usable data regarding relapse and favoured chlorpromazine continuation (n=376, 3 RCTs, RR 6.76 CI 3.37 to 13.54, NNH 4 CI 2 to 8). In the medium term six trials presented usable data regarding relapse and again the results favoured chlorpromazine continuation (n=850, 6 RCTs, RR 4.04 CI 2.81 to 5.81, NNH 4 CI 3 to 7). In the long term follow up category we obtained data from three trials which again favoured chlorpromazine continuation (n=510, 3 RCTs, RR 1.70 CI 1.44 to 2.01, NNH 4 CI 3 to 6).

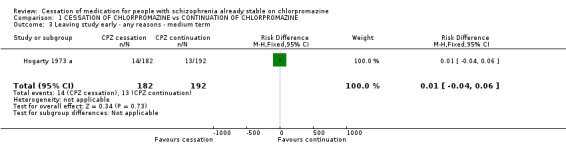

2.2 Leaving the study early Only one large study, Hogarty 1973 a with a duration of more than three years showed that people allocated to the chlorpromazine cessation group were not significantly more likely to stay in the study than those who were allocated to the chlorpromazine continuation group (n=374, 1 RCT, RR 1.14 CI 0.55 to 2.35). Surprisingly, we were unable to obtain any further data regarding patients who left the study early from other included studies.

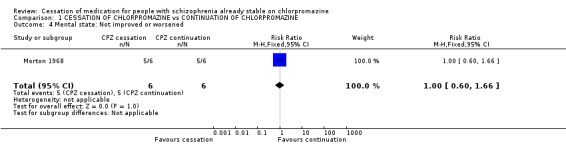

2.3 Mental state For this important outcome data were very limited. One included trial, Morton 1968, presented usable data relating to this outcome. This study reported no difference in mental state in patients who continued taking chlorpromazine in comparison with those in the cessation group using a cut off point of at least a 50% decline in score to indicate 'improvement' (n=12, 1 RCT, RR not improved 1.0 CI 0.60 to 1.66).

2.4 Missing outcomes No usable data were presented in any of the included trials about either the adverse effects or the economic (cost‐effectiveness) consequences of continuing on chlorpromazine or withdrawing from this medication.

2.4 SENSITIVITY ANALYSES A number of sensitivity analyses could not be performed as data were only available for people from different age groups, gender (male, female), chronicity and for those treated before or after 1990. However, sensitivity analyses on groups with different chlorpromazine dosages, or different diagnostic criteria were possible.

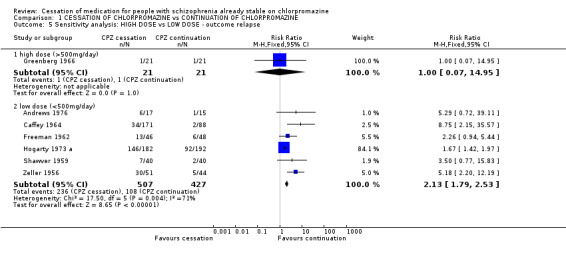

2.4.1 Low dose (<500mg/day) versus high dose (>500mg/day): Relapse Limited data were available for participants who took low dosages of chlorpromazine compared with those whose took higher dosages. The only primary outcome for which data were available for comparison was 'relapse'. Greenberg 1966 was the only one with dose >500 mg/day (n=42) while the other five studies used doses <500 mg/day (n=934). There were no significant differences in the outcomes of 'relapse' between these two groups as the wide confidence intervals for these groups of studies overlap.

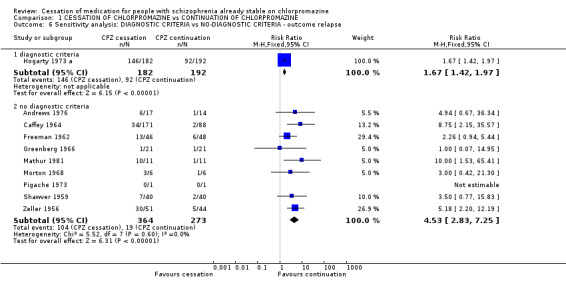

2.4.2 People diagnosed according to any operational criteria versus those who have not been diagnosed using operational criteria The available relevant studies allowed synthesis of data for the outcomes of 'relapse'. Hogarty 1973 a was the only trial with patients diagnosed according to an operational criterion (n=374) while nine other trials included patients with schizophrenia diagnosed clinically (n=638). 'Relapse' in trials with patients clinically diagnosed showed a significant difference in comparison with those who diagnosed patients according to operational criteria, yet both groups favours chlorpromazine continuation.

Discussion

1. Strengths and weakness of the review 1.1 Adding the old to the new This review includes trials that span nearly five decades of evaluative studies within psychiatry. It is possible that the rigour of these experiments has changed over time, as have participants and even the formulation of the drug (it was thought that introduction of impurities in early formulations of chlorpromazine led to jaundice). There is some empirical evidence that the quality of schizophrenia trial reporting has not changed much over time (Thornley 1998) or, if it has changed, it may even have declined (Ahmed 1998). We have found no time‐related differences in reporting of studies within this review and no suggestion of a change of the effect size over time. Synthesis of results seems justified.

1.2 Failing to identify old trials We identified trials by meticulous searching. Nevertheless, for a compound formulated so long ago, publication biases may be difficult to avoid. The strength of this review is that it presents up‐to‐date quantitative data for the withdrawal of a benchmark treatment for schizophrenia which is used throughout the world.

2. Applicability The 11 included studies in this review included many people who would be recognisable in everyday practice. There are those with strictly diagnosed illnesses, very likely to suffer from schizophrenia, and people whose illness was diagnosed using less rigorous criteria. Although the outcomes that have been used in this review are accessible to both clinicians and recipients of care, generalising to treatment in community settings, could be problematic. Most studies were undertaken in hospital, whereas the great majority of people with schizophrenia reside in the community.

3. Homogeneity We did not find heterogeneity. The test for homogeneity is based on the I‐square statistic, and is often fairly weak because the number of studies is small. However, the results of such tests, when statistically significant, suggest caution when adding trial data together.

4. COMPARISON: CHLROPROMAZINE WITHDRAWAL VERSUS CONTINUING ON CHLORPROMAZINE

4.1.Global state 4.1.1 Global improvement There were few data, but they show that global state deteriorated significantly after cessation of chlorpromazine (NNH 3 CI 2 to 7). These findings are limited and derived from only one study (n=95) but are consistent with clinical impressions.

4.1.2 Relapse This is a primary outcome in this review and there were data regarding the relapse from studies with different periods of follow ups, but the strongest results come from studies of six months duration. For this period, which was classified as medium term follow up, data were obtained from six trials and homogeneous data clearly favoured chlorpromazine continuation over its cessation. The people included in the trials that provide data for this review were, largely, very chronically unwell. Stopping the drug on which they had been stable often resulted in relapse with a relatively small NNH with tight confidence intervals (NNH 4 CI 3 to 7).

4.1.4 Death It may be surprising that there were no deaths reported among over 1000 people with schizophrenia who were randomised to chlorpromazine cessation or chlorpromazine continuation. The lifetime incidence of suicide for people suffering from schizophrenia is 10‐13% (Caldwell 1992). Furthermore, the use of large doses of antipsychotic drugs has been associated with sudden death (Jusic 1994) but there are no records of such events within this review. The fact that there were no deaths may reflect the fact that either trial‐care is more vigilant than routine care or that death is an under‐reported outcome.

4.2 Leaving the study early Withdrawing chlorpromazine seems to result in no more people leaving the study compared with continuation of the same drug (n=374, 1 RCT, RR 1.14 CI 0.55 to 2.35). We are unclear what this finding represents. It could be a function of good trial design, or reflect the nature of the patient group.

4.3 Mental state In fact, very little can be said about mental state from chlorpromazine withdrawing trials included in this review, and we were only able to obtain usable data from one small study (Morton 1968, n=12). However, trials comparing instigation of chlorpromazine with placebo presented good data about mental state and this has been fully assessed in another Cochrane review (Thornley 2006).

4.4 Sensitivity analysis As was likely from the start, the power to detect a real difference between studies in any one of the sensitivity analyses was very low. Only subsets of already limited lists of trials were available. The wide confidence intervals could be hiding true differences in effect between the sexes, age groups of people, acutely and chronically ill people, those allocated high or low doses of chlorpromazine, people diagnosed with operational criteria as opposed to more clinical diagnoses, and early trials versus current studies. The only suggestion of a statistically significant difference was for high dose versus low dose studies (relapse between nine weeks and six months). It is important to remember that this is now a non‐randomised comparison between studies, rather than within a study, and that this is one of many statistical tests that were undertaken on this dataset. Further complicating matters is the fact that the other outcomes within this particular sensitivity analysis did not clearly support or refute this difference between high and low doses. The significant difference in the 'relapse' outcome between groups with clinically diagnosed schizophrenics and those diagnosed according to checklist criteria is interesting.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with schizophrenia For people with their first episode of schizophrenia medication is useful. Studies suggest that over 10% of this group will not go on to have further relapses. The trials in this review do not include people in this important group and the data do not easily relate to people with first episodes of this difficult and damaging illness. People whose illness is established, who have been stabilised on chlorpromazine, should not stop their medication in favour of placebo.

2. For clinicians Much evidence points to intermittent cessation of medication as being the normal pattern of compliance. In this review we confirm much that clinicians already know, but this review does provide some quantification to support clinical impression. For people with established illnesses, chlorpromazine withdrawal shows significant increase in relapse across all time periods. For people in their first episode of schizophrenia about 13% will not go on to need antipsychotic medications in the long term (Shepherd 1989). This review does not help either identify or quantify risk in this important subgroup.

3. For managers or policy makers Chlorpromazine is inexpensive and therefore it is understandable that it remains one of the most widely prescribed drugs used for treating people with schizophrenia. Clearly cessation is related to increased rates of relapse for those with established illness. Relapse incurs costs, as does the management of adverse effects of chlorpromazine. This review, however, does not contain cost‐effectiveness data.

Implications for research.

1. General So much more could have been learnt about the effects of the cessation of chlorpromazine if the studies in this review had clearly described the method of allocation, the integrity of blinding, especially for the more subjective outcomes, and the reasons for early withdrawal (Moher 2001).

2. More trials comparing chlorpromazine with placebo? Even though chlorpromazine has been used as an antipsychotic drug for decades, there are still only a few well‐conducted randomised, placebo‐controlled trials measuring the effects of its cessation and potential to cause deterioration. Stopping medication, failing to comply with ongoing treatment is so common (CATIE 2005) and therefore it is essential that clinicians and patients should know in quantitative terms, of the consequences of such an action. New studies evaluating the consequences of the cessation in comparison with the continuation of the treatment would be most welcome, but probably are only ethical for people who have decided to stop the medication anyway. Within the trial, people should be encouraged to either continue for some period or continue with their decision to stop, within the context of the trial. In this way the consequences of their decision could be closely monitored and any adverse consequences picked up very quickly.

We have outlined methods for a study in Table 04. Concrete and simple outcomes are of interest. For example, clearly reporting improvement, 'number of violent incidents', 'relapse' (giving some description of criteria), 'hospital discharge or admission', and 'presence of delusions or hallucinations' would have been helpful, and simple reporting of levels of satisfaction and quality of life would have been most informative. Chlorpromazine has been in use for decades, yet clinicians still have no trial‐based data indicating how people with schizophrenia would fair in the short, medium and long term if the drug was stopped. If rating scales are to be employed, a concerted effort should be made to agree on which measures are the most useful. Studies within this review reported on so many scales that, even if results had not been poorly reported, they would have been difficult to synthesise in a clinically meaningful way.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 July 2012 | Amended | Update search of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trial Register (see Search methods for identification of studies), no new studies found. |

History

Review first published: Issue 1, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 January 2009 | Amended | Author order amended |

| 25 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 November 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group editorial base for their help, their support and the fun we had whilst working there.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Global state: 1. Not improved or worsened ‐ short term | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.46 [1.51, 3.99] |

| 2 Global state: 2. Relapse | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 short term | 3 | 376 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.76 [3.37, 13.54] |

| 2.2 medium term | 6 | 850 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.04 [2.81, 5.81] |

| 2.3 long term | 3 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [1.44, 2.01] |

| 3 Leaving study early ‐ any reasons ‐ medium term | 1 | 374 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.06] |

| 4 Mental state: Not improved or worsened | 1 | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.60, 1.66] |

| 5 Sensitivity analysis: HIGH DOSE vs LOW DOSE ‐ outcome relapse | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 high dose (>500mg/day) | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.95] |

| 5.2 low dose (<500mg/day) | 6 | 934 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [1.79, 2.53] |

| 6 Sensitivity analysis: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA vs NO‐DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA ‐ outcome relapse | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 diagnostic criteria | 1 | 374 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [1.42, 1.97] |

| 6.2 no diagnostic criteria | 9 | 637 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.53 [2.83, 7.25] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 1 Global state: 1. Not improved or worsened ‐ short term.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 2 Global state: 2. Relapse.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 3 Leaving study early ‐ any reasons ‐ medium term.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 4 Mental state: Not improved or worsened.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 5 Sensitivity analysis: HIGH DOSE vs LOW DOSE ‐ outcome relapse.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CESSATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE vs CONTINUATION OF CHLORPROMAZINE, Outcome 6 Sensitivity analysis: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA vs NO‐DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA ‐ outcome relapse.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Andrews 1976.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned. Blinding: double, identical capsules given by the hospital pharmacist who "alone held the key to the drug assignment". Duration: 42 weeks (preceded by 8 weeks stabilisation on chlorpromazine). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=32. Age: mean 55 yrs. Sex: all male. History: in hospital > 6 yrs, mean 23 yrs, on oral phenothiazine. Excluded: on depot injections of phenothiazine. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=17. 2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose 50,150‐200 or 200‐450 mg/day. N=15. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse. Unable to use ‐ Behaviour change: WBRSW (no SD). Leaving the study early: due to deterioration of behaviour ‐ 3 people (not reported by group). Death: coronary thrombosis (not reported by group). |

|

| Notes | For one patient in the Control Group, the urine test for CPZ was negative and this patient "who did not relapse" was omitted from analysis in the results. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Caffey 1964.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned. Blinding: double, identical capsules. Duration: 16 weeks (preceded by 3 months stabilisation on either chlorpromazine or thioridazine). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=438 (269 to relevant interventions). Age: < 56, mean 40 yrs. Sex: all males. History: in hospital >2yrs, mean 10 yrs. Excluded: CNS disease, any seizures, prefrontal lobotomy. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=171. 2. Chlorpromazine or thioridazine intermittent treatment: dose 400 mg, 350 mg respectively 3 days a week. N=89. 3. Chlorpromazine or thioridazine continuation: dose 400 mg, 350 mg/day respectively. N=88. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse. Unable to use ‐ Global state: IMPS (no SD), Ward Evaluation Scale (no data). Behaviour change: PRP (no SD). Biochemistry: urine test (no SD). |

|

| Notes | * Data not detailed for each drug. We considered CPZ and Thioridazine patients as one group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Freeman 1962.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, pairs matched on morbidity. Blinding: double, identical capsules, "neither experimenters nor staff knew which patients were receiving the placebo". Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: psychosis (86 schizophrenia, 6 chronic brain syndrome, 2 personality disorders). N=94. Age: mean 44 yrs. Sex: all males. History: "chronic" in hospital >12 yrs, only on chlorpromazine in last 2 months. Excluded: physically assaultive, considered for discharge. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=46.

2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose 220 mg/day. N=48. Sedatives were permitted for occasional use when required. |

|

| Outcomes | Relapse. Unable to use ‐ Behaviour change: LBRS (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Greenberg 1966.

| Methods | Allocation: randomisation unclear, implied and supported by demographic data. Blinding: double. Duration: 60 weeks. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=42. Age: mean 42 yrs. Sex: all males. History: "chronic" in hospital mean 13 yrs, received chlorpromazine >8 months mean 2.5 yrs. Excluded: patients judged to have substantially decompensated. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=21. 2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose 510 mg/day. N=21. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse. Unable to use ‐ Global state: Rating Scale for Chronic Schizophrenia (no data). Behaviour change: Gardner Behaviour Chart (no data). Adverse effects: no usable data. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hogarty 1973 a.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, stratified by sex, factorial design (2*2). Blinding : double, identical capsules. Duration: 3 years (preceded by 2 months stabilisation on chlorpromazine). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM II). N=374. Age: range 18‐53, mean 34 yrs. Sex: male and female. History: recently discharged, hospital<2 yrs, IQ>70. Excluded: serious suicidal or homicidal behaviour, organic brain syndrome, unmanageable drinking or drug abuse. Setting: community. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=182.

2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose ˜270 mg/day. N=192. Factored to: A. Major Role Therapy. N=190. B. Rehabilitation counselling. N=184. |

|

| Outcomes | Relapse.

Leaving study early. Unable to use ‐ Death: not reported by group. Trouble with police. not reported by group. Mental state: BPRS, symptom checklist, IMPS, SSI (no SD). Social functioning: Major Role Adjustment Inventory, Katz Adjustment Scale, Casework Evaluation Schedule. (no SD). Carer morbidity: Family Distress Scale. (no SD). Global state: KAS (no SD). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Mathur 1981.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, cross‐over design (after 6months). Blinding: double, given by hospital pharmacist in individual bottles. Duration: 16 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=24. Age: mean 55 yrs. Sex: unknown. History: in hospital mean 27 yrs, stable on chlorpromazine >6 months. Setting: hostel. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=12. 2. Chlorpromazine continuation: (dose not reported). N=12. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse.

Leave the study early. Unable to use ‐ Death: 1 suicide (not reported by group). Behaviour: 1 person threatening (not reported by group). Global state: deterioration (not reported by group). Urine tests for the presence of phenothiazine. no data. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Morton 1968.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned. Blinding: double, identical capsule given by the hospital pharmacist. "no one concerned with the care of patients knew which patients were started on placebo". Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=40 (12 to relevant interventions). Age: 25‐55 yrs. Sex: all male. History: in hospital >2 yrs, on chlorpromazine >18 months, maintenance doses of tranquillizer had been administered for at least 18 months. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=6. 2. Trifluoperazine cessation: placebo. N=14. 3. Chlorpromazine continuation: (dose not reported). N=6 4. Trifluoperazine continuation: (dose not reported). N=14. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse.

Mental state: Wing scale. Unable to use ‐ Behaviour change: WPRS (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Pigache 1973.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, pairs matched on clinical status and IQ, cross‐over design. Blinding: double, independent pharmacist, sealed in individual envelopes. Duration: 55 weeks (preceded by 3 months stabilisation on chlorpromazine). | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=20. Age: 30‐50 yrs. Sex: all males. History: chronic> 2 yrs, unmarried. Excluded: given ECT or Insulin therapy during the last 12 months, physically unwell. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=10.

2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose 50‐100 mg/day. N=10. Minor analgesics, antibiotics (as necessary). |

|

| Outcomes | Relapse.

Mental state: BPRS, PAT.

Leaving the study early (cross over design: 2 patients; placebo at the time of leaving. 1 patient; CPZ 50% at the time of leaving). Unable to use ‐ Biochemistry: Blood + urine tests (no data). Global state: Average Global Rating Scale (no SD). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Shawver 1959.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, pairs matched on the morbidity score and ward location (randomised block design). Blinding: double, identical capsule. Duration: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. N=120 (80 to relevant interventions). Age: < 50 yrs. Sex: unknown. History: in hospital mean 8 yrs, on chlorpromazine >6 months. Excluded: leucotomy or organic conditions, ECT for the past year. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=40. 2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose 200 mg/day. N= 40. 3. Reserpine continuation: dose 2 mg/day. N=40. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse.

Global state: MSRPP (morbidity score). Unable to use ‐ Behaviour change: AAMI (no usable data). |

|

| Notes | A team of two including the ward psychiatric made a joint interview to increase the reliability of the rating. AAMI consisted of five separated measures: Level of activity, level of anxiety, mental disorganization, interpersonal relationships and abnormality of activity. No data about whether relapses occured during the short term or medium term. All considered medium term. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Zeller 1956.

| Methods | Allocation: randomly assigned, pairs matched on diagnosis. Blinding: stated as double blind, but "only one investigator knew which patients were in each group and when placebo treatment was instituted'. Duration: 1 month. | |

| Participants | Diagnosis: mainly people with schizophrenia*. N=176 (95 to relevant interventions). Age: unknown. Sex: unknown. History: stable on either CPZ or reserpine. Excluded: receiving medication < 1month. Setting: hospital. | |

| Interventions | 1. Chlorpromazine cessation: placebo. N=51. 2. Chlorpromazine continuation: dose >200 mg/day. N=44. 3. Reserpine continuation: dose 2 mg/day. N=37. 4. Reserpine cessation: placebo. N=44. | |

| Outcomes | Relapse. Unable to use‐ Global state: Malmud and Sands Worchester Rating Scale (no data). |

|

| Notes | *Almost 60% of the patients have schizophrenic reaction, the others have depressive, organic, neurotic and manic‐depressive reactions. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

CPZ‐ chlorpromazine. CNS‐ Central Nervous System. ECT‐ Electroconvulsive Therapy.

Mental state ‐ BPRS‐ Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. IMPS‐ Inpatient Multidimensional psychiatric Scale. MSRPP‐ Multi‐dimensional Scale for Rating Psychiatric Patients. PRP‐ Psychotic Reaction Profile.

Behaviour ‐ WBRSW‐ Ward Behaviour Rating Scale of Wing. SW‐ Social Withdrawal. SE‐ Socially Embarrassing Behaviour . LBRS‐ Lyons Behaviour Rating Scale. PRP‐ Psychotic Reaction Profile, ward behaviour scale completed by two nurses. Ward Evaluation Scale‐ completed by the patients. WBRSW ‐ Ward Behaviour Rating Scale of Wing.

AAMI‐ consisted of five separated measures: Level of activity, level of anxiety, mental disorganization, interpersonal relationships and abnormality of activity.

PAT‐ Pigache Attention Task(auditory attention task). SSI‐ Springfield Symptom Inventory.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Blackburn 1981 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine, prochlorperazine, perphenazine, promazine, trifluoperazine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Bouchard 1998 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: risperidone versus classical neuroleptics. |

| Chouinard 1990 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: remoxipride versus chlorpromazine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Crow 1986 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with first episode of schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, pimozide or trifluoperazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: results not broken down by individual drug. |

| Diamond 1960 | Allocation: randomisation unclear. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus triflupromazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: results not broken down by individual drug. |

| Garfield 1966 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine, thioridazine, trifluoperazine, perphenazine, prochlorperazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: results not broken down by individual drug. |

| Goldberg 1967 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus acetophenazine versus fluphenazine. |

| Good 1958 | Allocation: randomly assigned, cross over design. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: global state, behaviour change (no usable data). |

| Gross 1960 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine, perphenazine, prochlorperazine, promazine, reserpine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Hine 1958 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Hogarty 1973 b | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: global state (no usable data). |

| Howanitz 1996 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine versus clozapine. |

| Knight 1979 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: thiothixene versus trifluoperazine versus chlorpromazine. |

| Lapolla 1967 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine versus etrafon. |

| Levine 1997 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine, perphenazine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Mefferd 1958 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus placebo. Outcomes: behaviour change (MSRPP), mental state, side effects‐ no usable data. |

| Melnyk 1966 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: thioridazine and chlorpromazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: results not broken down by individual drug. |

| Montero 1971 | Allocation: randomisation unclear. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine and trifluoperazine versus thioridazine. |

| Moss 1958 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Pai 2001 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: reserpine versus placebo. |

| Pigache 1993 | Allocation: randomly assigned, cross over design. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine low dose versus medium dose versus high dose. |

| Pokorny 1974 | Allocation: randomisation unclear. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine versus thioridazine. |

| Pollack 1956 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Prien 1968 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine high dose versus chlorpromazine low dose, versus placebo versus drug chosen by physician, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Schiele 1961 | Allocation: randomisation unclear. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine versus thioridazine versus trifluoperazine versus placebo, not chlorpromazine withdrawal. |

| Slotnick 1971 | Allocation: randomisation unclear. Participant: agitated psychiatric patients. Intervention: haloperidol versus chlorpromazine. |

| Troshinsky 1962 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine, triflupromazine, thioridazine versus placebo, withdrawal study. Outcomes: results not broken down by individual drug. |

| Wilson 1982 | Allocation: randomly assigned. Participant: people with schizophrenia. Intervention: chlorpromazine versus pimozide. |

| Wode‐Helgodt 1981 | Allocation: not randomised. |

Contributions of authors

Muhammad Qutayba Almerie ‐ protocol development, data extraction, analysis, data interpretation and writing the final report.

Hosam El‐Din Matar ‐ protocol development, data extraction, analysis, data interpretation and writing the final report.

Hassan Alkhateeb ‐ protocol development data extraction.

Emtithal Rezk ‐ protocol development and data extraction.

Adib Essali ‐ writing up the final report.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Dr. Naser Al Merie, Not specified.

Mr. Yahya Matar, Not specified.

Mr.Bassam Alkhateeb, Bahrain.

External sources

Faculty of Medicine, Damascus University, Not specified.

Declarations of interest

None.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Andrews 1976 {published data only}

- Andrews P, Hall JN, Snaith RP. A controlled trial of phenothiazine withdrawal in chronic schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 1976;128:451‐55. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caffey 1964 {published data only}

- Caffey EM, Diamond LS, Frank TV, Grasberger JC, Herman L, Klett CJ, Rothstein C. Discontinuation or reduction of chemotherapy in chronic schizophrenics. Journal of Chronic Diseases 1964;17(4):347‐58. [PsycINFO 1965‐09583‐001] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffey EM, Forrest IS, Frank TV, Klett CJ. Phenothiazine excretion in chronic schizophrenics. American Journal of Psychiatry 1963;120:578‐82. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman 1962 {published data only}

- Freeman Leslie S, Alson Eli. Prolonged withdrawal of chlorpromazine in chronic patients. Diseases of the Nervous System 1962;23:522‐25. [PsycINFO 74‐32161] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Greenberg 1966 {published data only}

- Greenberg LM, Roth S. Differential effects of abrupt versus gradual withdrawal of chlorpromazine in hospitalized chronic schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 1966;123:221‐26. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hogarty 1973 a {published data only}

- Goldberg SC, Schooler NR, Hogarty GE, Roper M. Prediction of relapse in schizophrenic outpatients treated by drug and sociotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 1977;34(2):171‐84. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients. one‐year relapse rates. Archives of General Psychiatry 1973;28(1):54‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC, Schooler NR. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients. III. Adjustment of non relapsed patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 1974;31(5):609‐18. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC, Schooler NR, Ulrich RF. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients. II two‐year relapse rates. Archives of General Psychiatry 1974;31(5):603‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Ulrich RF. Temporal effects of drug and placebo in delaying relapse in schizophrenic outpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry 1977;34(3):297‐301. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mathur 1981 {published data only}

- Mathur S, Hall JN. Phenothiazine withdrawal in schizophrenics in a hostel. British Journal of Psychiatry 1981;138:271‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morton 1968 {published data only}

- Morton MR. A study of the withdrawal of chlorpromazine or trifluoperazine in chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 1968;124(11):1585‐88. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pigache 1973 {published data only}

- Pigache RM. The Clinical relevance of an auditory attention task (PAT) in a longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia with placebo substitution for chlorpromazine. Schizophrenia research 1993;10(1):39‐50. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigache RM, Norris HN. Measurement of drug action in schizophrenia. Clinical Science 1973;44(6):28. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shawver 1959 {published data only}

- Shawver JR, Gorham DR, Leskin LW, Good WW, Kabnick DE. Comparison of chlorpromazine and reserpine in maintenance drug therapy. Diseases of the Nervous System 1959;20:452‐57. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zeller 1956 {published data only}

- Zeller WW, Graffagnino PN, Cullen CF, Rietman HJ. Use of chlorpromazine and reserpine in the treatment of emotional disorders. JAMA 1956;160:179‐84. [PsycINFO 81‐02889] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Blackburn 1981 {published data only}

- Blackburn HL, Allen JL. Behavioral effects of interrupting and resuming tranquillizing medication among schizophrenics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1981;133:302‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bouchard 1998 {published data only}

- Bouchard RH, Pourcher E, Mérette C, Demers MF, Villeneuve J, Roy MA, Gauthier Y, Cliche D, Labelle A, Maziade M. One year follow up of schizophrenic patients treated with risperidone or classical neuroleptics: a prospective, randomized, multicentered open study. 11th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Congress; 1998 Oct 31 ‐ Nov 4; Paris, France. 1998. [11th Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology [CD‐ROM]: Conifer, Excerpta Medica Medical Communications BV, 1998 P2124]

Chouinard 1990 {published data only}

- Chouinard G. A placebo‐controlled clinical trial of remoxipride and chlorpromazine in newly admitted schizophrenic patients with acute exacerbation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum 1990;358:111‐19. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crow 1986 {published data only}

- Crow TJ, MacMillan JF, Johnson AL, Johnstone EC. A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic neuroleptic treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry 1986;148:120‐27. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diamond 1960 {published data only}

- Diamond LS, Marks JB. Discontinuance of tranquillizers among chronic schizophrenic patients receiving maintenance dosage. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1960;131:247‐51. [PsycINFO 1961‐02332‐001] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garfield 1966 {published data only}

- Garfield SL, Gershon S, Sletten I, Neubauer H, Ferrel E. Withdrawal of ataractic medication in schizophrenic patients. Diseases of the Nervous System 1966;27(5):321‐25. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldberg 1967 {published data only}

- Goldberg SC, Schooler NR, Mattsson N. Paranoid and withdrawal symptoms in schizophrenia: differential symptom reduction over time. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1967;145(2):158‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Good 1958 {published data only}

- Good WW, Sterling M, Holtzman WH. Termination of chlorpromazine with schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 1958;115:443‐48. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefferd RB Jr, Labrosse EH, Gawienowski AM, Williams RJ. Influence of chlorpromazine on certain biochemical variables of chronic male schizophrenics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1958;127:167‐79. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gross 1960 {published data only}

- Gross M, Hitchman IL, Reeves WP, Lawrence J, Newell PC. Discontinuation of treatment with ataractic drugs. A preliminary report. American Journal of Psychiatry 1960;116:931‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hine 1958 {published data only}

- Hine FR. Chlorpromazine in schizophrenic withdrawal and in the withdrawn schizophrenic. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1958;127:220‐27. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hogarty 1973 b {published data only}

- Hogarty GE, Munetz MR. Pharmacogenic depression among outpatient schizophrenic patients: a failure to substantiate. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 1984;4(1):17‐24. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Howanitz 1996 {published data only}

- Howanitz EM, Pardo M, Litwin P, Stern RG, Wainwright KM, FLosonczy M. Efficacy of clozapine versus chlorpromazine in geriatric schizophrenia. 149th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 1996 Oct 2 ‐ May 9; New York, New York, USA. 1996. [MEDLINE: ]

Knight 1979 {published data only}

- Knight RG, Harrison A. A double blind comparison of thiothixene and a trifluoperazine‐chlorpromazine composite in the treatment of chronic schizophrenia. New Zealand Medical Journal 1979;89(634):302‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lapolla 1967 {published data only}

- Apella A. A double blind evaluation of chlorpromazine versus a combination of perphenazine and amitriptyline. International Journal of Neuropsychiatry 1967;3(5):403‐5. [PsycINFO 1968‐07423‐001] [Google Scholar]

Levine 1997 {published data only}

- Levine J, Caspi N, Laufer N. Immediate effects of chlorpromazine and perphenazine following neuroleptic washout on word association of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Research 1997;26(1):55‐63. [MEDLINE: ; PsycINFO 1997‐06099‐006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mefferd 1958 {published data only}

- Mefferd RBJr, Labrosse EH, Gawienowski AM, Williams RJ. Influence of chlorpromazine on certain biochemical variables of chronic male schizophrenics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1958;127:167‐79. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melnyk 1966 {published data only}

- Melnyk WT, Worthington AG, Laverty SG. Abrupt withdrawal of chlorpromazine and thioridazine from schizophrenic in‐patients. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 1966;11(5):410‐13. [PsycINFO 1966‐13288‐001] [Google Scholar]

Montero 1971 {published data only}

- Montero E. Thioridazine compared with a combination of chlorpromazine and trifluoperazine hydrochloride in schizophrenic patients. 5th World Congress of Psychiatry; 1971 Nov 28 ‐ Dec 4; Mexico City, Mexico. 1971:433. [MEDLINE: ]

Moss 1958 {published data only}

- Moss CS, Jensen RE, Morrow W, Freund HG. Specific behavioural changes produced by chlorpromazine in chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 1958;115:449‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pai 2001 {published data only}

- Pai YM, Yu SC, Lin CC. Risperidone in reducing tardive dyskinesia: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2001 May 5‐10; New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Marathon Multimedia, 2001. [MEDLINE: ; PsycINFO 1997‐06099‐006]

Pigache 1993 {published data only}

- Pigache RM. Effects of placebo, orphenadrine, and rising doses of chlorpromazine, on PAT performance in chronic schizophrenia. A two year longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Research 1993;10(1):51‐59. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pokorny 1974 {published data only}

- Pokorny AD, Prien RF. Lithium in treatment and prevention of effective disorder: a VA NIMH collaborative study. Diseases of the Nervous System 1974;35(7):327‐33. [PsycINFO 53‐03687] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pollack 1956 {published data only}

- Pollack B. The effect of chlorpromazine on the return rate of 250 patients released from the Rochester State Hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry 1956;112:937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prien 1968 {published data only}

- Prien RF, Cole JO, Bel kin NF. Relapse in chronic schizophrenics following abrupt withdrawal of tranquillizing medication. British Journal of Psychiatry 1968;115(523):679‐86. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prien RF, Levine J, Cole JO. Indications for high dose chlorpromazine therapy in chronic schizophrenia. Diseases of the Nervous System 1970;31(11):739‐45. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schiele 1961 {published data only}

- Schiele BC, Vestre ND, Stein KE. A comparison of thioridazine, trifluoperazine, chlorpromazine, and placebo: a double‐blind controlled study on the treatment of chronic hospitalized, schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Psychopathology 1961;22(3):151‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Slotnick 1971 {published data only}

- Slotnick VB. Management of the acutely agitated psychiatric patient with parental neuroleptics: the comparative symptom effectiveness profiles of haloperidol and chlorpromazine. 5th World Congress of Psychiatry; 1971 Nov 28 ‐ Dec 4; Mexico City, Mexico. 1971:531. [MEDLINE: ]

Troshinsky 1962 {published data only}

- Troshinsky C, Aaronson H, Stone RK. Maintenance phenothiazines in aftercare of schizophrenic patients. Pennsylvania Psychiatric Bulletin 1962;2:11‐15. [Google Scholar]

Wilson 1982 {published data only}

- Wilson LG, Roberts RW, Gerber CJ, Johnson MH. Pimozide versus chlorpromazine in chronic schizophrenia ‐ a 52 week double blind study of maintenance therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1982;43(2):62‐5. [PsycINFO 68‐06384] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wode‐Helgodt 1981 {published data only}

- Wode‐Helgodt B, Alfredsson G. Concentrations of chlorpromazine and two of its active metabolites in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of psychotic patients treated with fixed drug doses. Psychopharmacology 1981;73(1):55‐62. [PsycINFO 68‐06384] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Ahmed 1998

- Ahmed I, Soares K, Seifas R, Adams CE. Randomised controlled trials in Archives of General Psychiatry (1959‐1995): a prevalence study. Archives of General Psychiatry 1998;55(8):754‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Altman 1996

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Detecting skewness from summary information. BMJ 1996;313:1200. [OLZ020600] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bland 1997

- Bland JM, Kerry SM. Statistics notes. Trials randomised in clusters. British Medical Journal 1997;315:600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boissel 1999

- Boissel JP, Cucherat M, Li W, Chatellier G, Gueyffier F, Buyse M, Boutitie F, Nony P, Haugh M, Mignot G. The problem of therapeutic efficacy indices. 3. Comparison of the indices and their use. Therapie 1999;54(4):405‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caldwell 1992

- Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenia ‐ a high‐risk factor for suicide: clues to risk reduction. Suicide and life‐threatening behavior 1992;22:479‐93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carpenter 1994

- Carpenter WT Jr, Buchanan RW. Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 1994;330:681‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CATIE 2005

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 2005;353:1209‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Curson 1985

- Curson DA, Barnes TR, Bamber RW, Platt SD, Hirsch SR, Duffy JC. Long‐term depot maintenance of chronic schizophrenic out‐patients: the seven year follow‐up of the Medical Research Council fluphenazine/placebo trial. III. Relapse postponement or relapse prevention? The implications for long‐term outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry 1985;146:474‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davis 1975

- Davis JM. Overview: maintenance therapy in psychiatry ‐ I. Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 1975;132:1237‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2000

- Deeks J. Issues in the selection for meta‐analyses of binary data. Abstracts of 8th International Cochrane Colloquium; 2000 Oct 25‐28th; Cape Town, South Africa. 2000.

Divine 1992

- Divine GW, Brown JT, Frazer LM. The unit of analysis error in studies about physicians' patient care behavior. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1992;7:623‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donner 2002

- Donne A, Klaar N. Issues in the meta‐analysis of cluster randomized trials. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21:2971‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Essali 1993

- Essali MA, Maddocks PD. Seventeen years in the life of a depot neuroleptic clinic ‐ an audit study of schizophrenia and other psychosis. British Journal of Medical Economics 1993;6:3‐11. [Google Scholar]

Gilbetr 1995

- Gilbert PL, Harris J, Adams LA, Jest DV. Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 1995;52:174‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gulliford 1999