Keywords: cardiac, caspases, fetal development, myocardium, unfolded protein response

Abstract

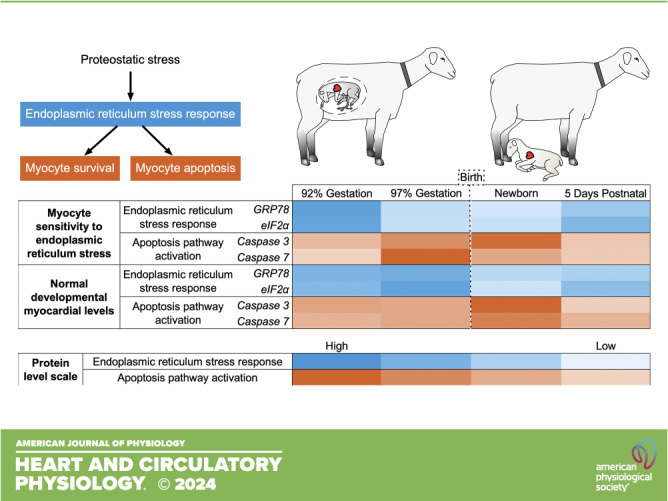

Although the unfolded protein response (UPR) contributes to survival by removing misfolded proteins, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress also activates proapoptotic pathways. Changed sensitivity to normal developmental stimuli may underlie observed cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the healthy perinatal heart. We determined in vitro sensitivity to thapsigargin in sheep cardiomyocytes from four perinatal ages. In utero cardiac activation of ER stress and apoptotic pathways was determined at these same ages. Thapsigargin-induced phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) was decreased by 72% between 135 and 143 dGA (P = 0.0096) and remained low at 1 dPN (P = 0.0080). Conversely, thapsigargin-induced caspase cleavage was highest around the time of birth: cleaved caspase 3 was highest at 1 dPN (3.8-fold vs. 135 dGA, P = 0.0380; 7.8-fold vs. 5 dPN, P = 0.0118), cleaved caspase 7 and cleaved caspase 12 both increased between 135 and 143 dGA (25-fold and 6.9-fold respectively, both P < 0.0001) and remained elevated at 1 dPN. Induced apoptosis, measured by TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, was highest around the time of birth (P < 0.0001). There were changes in myocardial ER stress pathway components in utero. Glucose (78 kDa)-regulated protein (GRP78) protein levels were high in the fetus and declined after birth (P < 0.0001). EIF2A phosphorylation was profoundly depressed at 1 dPN (vs. 143 dGA, P = 0.0113). In conclusion, there is dynamic regulation of ER proteostasis, ER stress, and apoptosis cascade in the perinatal heart. Apoptotic signaling is more readily activated in fetal cardiomyocytes near birth, leading to widespread caspase cleavage in the newborn heart. These pathways are important for the regulation of normal maturation in the healthy perinatal heart.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Cardiomyocyte apoptosis occurs even in the healthy, normally developing perinatal myocardium. As cardiomyocyte number is a critical contributor to heart health, the sensitivity of cardiomyocytes to endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to apoptosis is an important consideration. This study suggests that the heart has less robust protective mechanisms in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress immediately before and after birth, and that more cardiomyocyte death can be induced by stress in this period.

INTRODUCTION

How the final number of cells that make up an organ is decided remains a fundamental mystery. The maximum number of cardiac myocytes is determined in development (1–3), a number that matters because loss of cardiac myocytes contributes to failure in heart disease (4–6).

Programmed cell death plays a key role in the morphogenesis and remodeling of organs during normal development, as well as in pathological conditions (7, 8). During the prenatal period, proliferation increases cardiac myocyte number (1, 2), whereas myocyte death has been described in the normal heart around the time of birth (2, 9–11). In the sheep heart, we have found that total myocyte number declines shortly before birth (2), coinciding with an increased rate of myocyte hypertrophy (2) and increases in cortisol and thyroid hormone before labor (12). Segar and coworkers (13–15) found that newborn lambs are more vulnerable than more mature neonates to apoptosis induced by cardiopulmonary bypass. Intriguingly, treatment of pregnant guinea pigs with the antioxidant pyrroloquinoline quinone reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and increased cardiomyocyte number in hearts of normally growing fetuses, without affecting myocyte proliferation (16). These data suggest that changing sensitivity to reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the healthy perinatal heart contributes to cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

The antioxidant capacity of the fetus is low until the days before birth when it increases both by upregulation of enzymatic systems as well as placental transfer of nonenzymatic antioxidants (17). The role of ROS in the fetal heart is complicated and difficult to study. It is known that oxygen is both a biological stress and a biological signal during development (17–20). Birth constitutes a major oxidative challenge, and while the late gestational period at which we observed cardiomyocyte loss is not associated with notable changes in oxygenation (12), the cardiovascular response to hypoxia changes with the prepartum rise in cortisol (21). Although the duration and frequency of prelabor uterine contractions (“contractures”) do not change over the last third of gestation until immediately before birth (22), these mildly hypoxic episodes may play a role in the context of dynamic cardiomyocyte sensitivity.

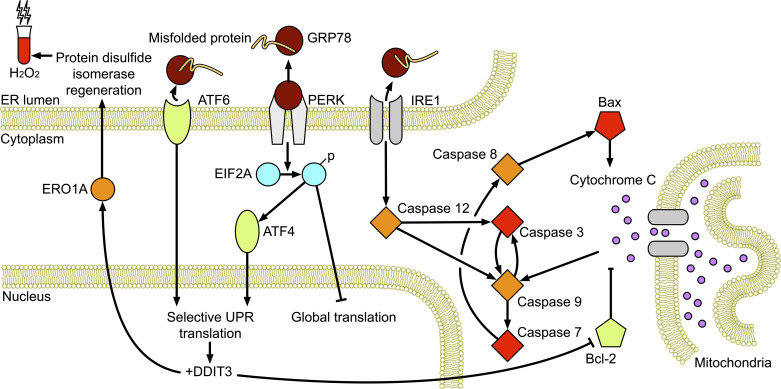

ROS interact with and damage molecules in cells, to which cells may respond through repair or by initiation of apoptosis (23). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is responsible for protein quality control. The unfolded protein response (UPR) contributes to proteostasis by recognizing and sending for degradation the low proportion of proteins that become misfolded during the normal functioning of the cell (24, 25). When protein unfolding increases, as occurs as a consequence of exposure to ROS, the chaperone protein 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) releases signaling molecules activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), PERK, and IRE1 to globally decrease protein translation, and to selectively increase levels of UPR proteins and those responsible for ER-associated protein degradation (Fig. 1) (23, 26). Prolonged or intense ER stress stimulates activation of proapoptotic pathways via increased expression of regulator DNA damage-inducible transcript (DDIT3) and cleavage of caspase 12.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response pathway. ATF, activating transcription factor; BAX, Bcl-2-associated X-protein; DDIT3, DNA damage-inducible transcript; EIF2A, eukaryotic initiation factor 2; ERO1A, ER oxidoreductase 1; GRP78, 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein; UPR, unfolded protein response.

Little is known about the role of ER protein quality control pathways in the developing heart, although this system likely plays a major role during normal development as well as in the congenital heart. To address the hypothesis that the sensitivity of ER and apoptotic signaling pathways increases in the perinatal heart, we studied fetal sheep cardiomyocytes and myocardium from four ages surrounding the time of birth. Our findings contribute new knowledge about the status of the myocardial ER and apoptosis regulation over the time of birth, which may provide understanding not just of normal development but also factors impacting the transition to extrauterine life in infants with congenital heart disease and other cardiac vulnerabilities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Ethical Approval

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health and Science University reviewed and approved all animal protocols (IP007), which were conducted according to the standards defined by the National Institutes of Health. Sheep (Ovis aries) of mixed Western breeds were obtained from a local supplier. Only animals in good body condition, healthy and free from obvious defects, and within the 90% confidence interval of body weight for age were included in the study.

Before euthanasia, whole blood was drawn from the jugular vein (adult and neonatal sheep) or umbilical artery (fetuses), coagulated at room temperature, separated by centrifugation, and processed as described in Lipid Peroxidation Assay. Fetuses and neonates were then given heparin sodium (10,000 U iv) to prevent coagulation. Sheep were humanely euthanized and their hearts were arrested in diastole by injection of a commercial pentobarbital sodium solution (80 mg/kg iv; SomnaSol, Covetrus, OH). Fetuses were given 6–10 mL saturated KCl via the umbilical vein to arrest their hearts in diastole. Hearts were removed without delay.

For living cardiomyocyte-based assays, hearts were immediately dissociated into free cell suspensions as previously described (2). Cardiomyocytes were used promptly in assays (caspase 12 activity, cell viability, TUNEL assay) or were cultured as described previously (27). For measurement of lipid peroxidation, a 50-mg left ventricular (LV) biopsy was promptly taken from the mid-free wall and processed as described in Lipid Peroxidation Assay. For assays requiring frozen myocardium, hearts were dissected along standard anatomical landmarks, and most of the LV was frozen in liquid nitrogen to be stored at −80°C. Every analysis includes six animals/age, and has equal numbers of females and males. Five ages were studied: near-term fetuses at 135 days of gestational age (dGA; term = 147 dGA), fetuses immediately before birth at 143 dGA, newborn lambs at 1 day postnatal (dPN), lambs at 5 dPN, and (for tissue studies) mature, nonpregnant adult sheep (at least 1 yr of age).

Induction of ER Stress in Cultured Cardiomyocytes

Thapsigargin is a potent inhibitor of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) that is responsible for maintaining the normal calcium gradient between the ER and the cytosol (28). SERCA is a node controlling many apoptotic pathways, via the ER stress response as ER calcium levels decline, and via non-ER pathways as cytosolic calcium increases. Dose finding for thapsigargin is necessary for each unique biological application (29). A 5 μM dose of thapsigargin over 12 h was selected for all subsequent experiments as it resulted in ≤50% cell death in all ages studied. Although thapsigargin inhibits the accumulation of Ca2+ accumulation by the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca++ ATPase pump with half-maximal potency at ∼10–20 nM, other investigators have also shown an LD50 similar to ours for immature cardiomyocytes (30, 31).

All cardiomyocyte culture experiments were performed as previously described (32), with minor modifications. LV cardiomyocytes were plated for 24 h in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco DMEM; Cat. No. 11885084, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite (10 mL·L−1; Cat. No. I1884, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA), antibiotic–antimycotic solution (10 mL·L−1; Cat. No. A5955, Millipore Sigma), and fetal bovine serum (Gibco FBS, 10%; Cat. No. 10082147, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Six hours before experimental treatment, media was replaced with supplemented DMEM without FBS. Thapsigargin (5 μM; Cat. No. T9033, Millipore Sigma) was then added to the media, and cells were incubated for 12 h before assessment of outcomes.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA extraction and first-strand reverse transcription followed by quantitative real-time PCR was performed to determine mRNA expression levels from frozen myocardium as previously described (33). For cultured cells, cardiomyocytes were plated at 5 × 105 per well in six-well plates. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1. Reactions were performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed using the standard curve method. Expression levels of experimental genes from myocardial and cardiomyocyte culture samples were normalized to the geometric mean of ribosomal protein L32 (RPL32), ribosomal protein L37α (RPL37A), and hyaluronidase 2 (HYAL2), which we found to be unchanged in the myocardium across the lifespan studied (data not shown).

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative PCR

| Gene Name | Forward | Reverse | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) | CAGCAGCTACTAGGTACCCC | CCTTGCTTTGCGAACCTCTT | NM_001142518.1 |

| Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) | AGTTCTGCCCTCTCCTCAAC | GGGACTGACAAGCTGACTCT | XM_012185020.3 |

| Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) | GCCAGAGGATGACGAAGGGA | TCCAGCTAGGGCTTTGTCGC | XM_004019650.3 |

| Bcl-2-associated X-protein (BAX) | TGTCTGAAGCGCATTGGAGAT | AGGGCCTTGAGCACCAGTTT | XM_015100639.1 |

| Caspase 3 (CASP3) | CCAATGGACCCGTCGATCT | GTCTGCCTCAACTGGTATTTTCTGA | XM_015104559.1 |

| Caspase 8 (CASP8) | TGCAGACATCCGACACAGTT | TCCCTTTGCTGTTTGGTCTC | XM_012142477.2 |

| Caspase 9 (CASP9) | CCCATCAAAGCCAAGCCAAG | TGCGTTCAGGACATAGGCCA | XM_012187486.2 |

| DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT; also known as CHOP) | TGAGTCATTGCCGTTCTCCT | AGGGTCAAGAGTGGTGAAGG | XM_004006542.5 |

| Cytochrome-c, somatic (CYCS) | GGTGATGTTGAGAAGGGCAA | CTCCATCAGCGTCTCCTCTC | XM_004007950.2 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1A) | TTGGGGCTGTGGATGAATCT | GGTCCCTTGTAACCCGTGTA | XM_027971493.2 |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) | TGGCAGGAATGAATGTGTGG | AGACCTCAGCAACATGACGA | XM_004010732.5 |

| Hyaluronidase 2 (HYAL2) | AGGCCGCTGCCCTGATGTTG | GCGGCCGTGAGTGGAGGAAG | JX231101.1 |

| Ribosomal protein L32 (RPL32) | AATCAAGCGGAACTGGCG | GGCATTGGGATTGGTGATT | XM_004018540.2 |

| Ribosomal protein L37α (RPL37A) | ACCAAGAAGGTCGGAATCGT | GGCACCACCAGCTACTGTTT | XM_012166909.1 |

Western Blot Analysis

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis were performed to determine protein expression levels from frozen myocardium similar to the work previously described (32). For cultured cells, cardiomyocytes were plated at 5 × 105 per well in six-well plates. Following induction of stress by thapsigargin, described earlier, proteins were extracted. Briefly, after the thapsigargin treatment cardiomyocytes cells were rinsed with 1× PBS and lyzed with 1× RIPA lysis buffer (Cat. No. 20-188, Millipore Sigma), with protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail I and II (Cat. Nos. 524624 and 524625, Millipore Sigma). Samples [10 μg protein, as quantified by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay] and a protein standard were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel and then transferred to Amersham Protran nitrocellulose membranes (Cat. No. 10600015, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each gel included a protein ladder (Cat. No. 26616, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Multiple gels were required to accommodate all the samples from each set of experiments in addition to a protein standard. To improve reproducibility, all samples, gels, and blots were processed at the same time using the same solutions within each experiment, and samples from different ages were equally distributed across each gel. Following incubation with primary antibodies (Table 2), membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and then incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary: anti-rabbit IgG (Cat. No. 7074, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or anti-mouse IgG (Cat. No. 7076, Cell Signaling Technology). Protein signals were detected with chemiluminescence substrate (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate, Cat. No. 34075, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then visualized (SRX101A, Konica-Minolta, Ramsey, NJ, or G:Box, Syngene, Frederick, MD). Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of protein levels, were repeated at least twice. Expression levels of experimental proteins were normalized to total eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) (phospho-EIF2A) or tubulin-α1β chain (TUBA1B) (all other proteins). After densitometry of raw images, representative images were prepared by juxtaposition of relevant lanes with the same blot and auto white balance to adjust contrast for the entire image.

Table 2.

Antibodies used from cell signaling technology

| Protein Target | Protein Role | Catalog No. | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaved caspase 3 | Executor caspase associated with the endoplasmic reticulum | 9664 | AB_2070042 |

| Cleaved caspase 7 | Executor caspase associated with the endoplasmic reticulum | 8438 | AB_11178377 |

| Caspase 12 | Executor caspase associated with the endoplasmic reticulum | 2202 | AB_2069200 |

| GRP78 | Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone with antiapoptotic properties, key in UPR | 3177 | AB_2119845 |

| Total eIF2A | Regulator of the rate-limiting step of mRNA translation | 5324 | AB_10692650 |

| Phospho-eIF2A | Phosphorylation inhibits this central regulator to reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress | 3398 | AB_2096481 |

| Tubulin-α1β chain (TUBA1B) | Reference protein | 2125 | AB_2619646 |

Caspase 12 Activity

Caspase 12 is an apoptosis effector localized to the ER membrane and is activated by ER stress (caspase 4 is the paralog in humans) (28, 34). Caspase 12 activity was measured to determine cardiomyocyte sensitivity to ER stress using a fluorometric assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Cat. No. ab65664, Abcam, Waltham, MA). Briefly, cardiomyocytes (1 × 105) were plated in a 96-well black side, clear-bottomed optical plate. Following thapsigargin treatment, media was collected from each well, suspended cells were pelleted, and media was discarded. Ice-cold lysis buffer (50 μL; 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% CHAPS, 0.1 mM EDTA) was added to the adherent cells in the plate (30 μL), and to the cell pellet (20 μL), which was then consolidated in the plate and incubated on ice for 10 min. They were then incubated at 37°C for 2 h with reaction buffer (50 μL; 10 mM dithiothreitol) and the caspase 12 cleavage substrate, ATAD-AFC (50 mM; ATAD: acetyl-alanine-threonine-alanine-aspartic acid; AFC: 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin). Caspase 12 activity was obtained with excitation at 400 nm and emission at 505 nm (Synergy H1 plate reader, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VY). Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of caspase 12 activity, was performed in triplicate. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 7%, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 6%.

Cell Viability

Cell viability following ER stress was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) bioreduction assay in which mitochondrial dehydrogenases reduce MTT to a colorimetric formazan product (cell death reduces formazan production), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cat. No. 11465007001, Roche Diagnostics). Briefly, cardiomyocytes were plated in 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells per well. After thapsigargin treatment, described earlier, MTT was added to each well (final concentration, 0.5 mg·mL−1). Cells were incubated for another 4 h (total thapsigargin exposure 16 h). The formazan product was dissolved by adding 100 µL solubilization solution and absorbance was measured at 595 nm (Synergy H1 plate reader). Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of cell metabolic activity, was performed in triplicate and was repeated twice. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 8%, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 12%.

TUNEL Assay

Cell apoptosis following ER stress was assessed in culture followed by TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) of the 3′-OH ends of fragmented DNA, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Click-iT Plus TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit, Cat. No. C10617, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, cardiomyocytes (1 × 105) were plated on coverslips coated with laminin (5 μg·mL−1 for 4 h). Following thapsigargin treatment, described earlier, cells were fixed with freshly made 4% formaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at room temperature before TUNEL labeling. All samples were stained with Hoechst 33342 at 1 μg·mL−1 for 10 min in the dark at room temperature, and mounted on slides for counting (Zeiss Axiovert A1, Oberkochen, Germany). The proportion of positive cells out of a total of 50 cells from each reaction was counted. Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of cell apoptosis, was repeated three times. The interassay coefficient of variation was 13%.

Lipid Peroxidation Assay

Oxidative stress leads to lipid peroxidation within the body, producing end products such as malondialdehyde (MDA). To evaluate oxidative damage present in fresh-frozen serum and LV myocardium, MDA was quantified by reaction with thiobarbituric acid to form a colorimetric product as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Cat. No. MAK085, Millipore Sigma). Briefly, myocardium (10 mg) was homogenized in water (150 μL) containing dibutylhydroxytoluene (3 μL). Perchloric acid (2 N, 50 μL) was added and precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation. To enhance assay sensitivity, 1-butanol was used to extract the MDA-thiobarbituric acid adduct from both plasma and myocardial samples. The product was measured at 532 nm (Synergy H1 plate reader). The assay was performed in triplicate and was repeated twice. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 8%, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 6%.

Total Nucleic Acids

The relative concentrations of mRNA, total RNA, and DNA were determined to understand global transcriptional regulation (35). Assays were performed in myocardium from a separate set of control fetuses, collected similarly to those described earlier, at 133 ± 3 dGA, 139 ± 2 dGA, and 4 ± 3 dPN (n = 7 all groups). Total nucleic acids were isolated from 30 to 50 mg of tissue homogenized in RNase-free lysis buffer, containing (in mM) 10 Tris (pH 8.0), 100 NaCl, and 10 EDTA and 0.5% SDS using a bead homogenizer (TissueLyzer, Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Samples were deproteinized via phenol/chloroform extractions, precipitated in ethanol with NaCl (0.2 M final), and resuspended in TE buffer, consisting of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA. Total nucleic acids were quantified by spectroscopy. Total RNA was isolated from total nucleic acids using TRIzol and biotinylated cDNA was prepared from total RNA using biotin-dCTP and random hexamer primers, and from mRNA using biotin-dCTP and oligo-d (T) primer. First-strand cDNA from total RNA and mRNA was quantified by dot blot. Three microliters of the reverse transcription reactions were spotted on nitrocellulose membrane, UV cross-linked, and rinsed with PBS. Blots were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS-Tween-20, and then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin. After washing, chromogenic substrate was added, and then the optical density of blots was quantitated.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software; RRID SCR_002798). Parameters were compared by sex and age by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If an interaction was present, the main effects were not tested. If justified, multiple comparisons were tested by Šídák’s test. Statistical significance was determined at P value < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Thapsigargin-Induced ER and Caspase Responses Are Greatest near the Time of Birth

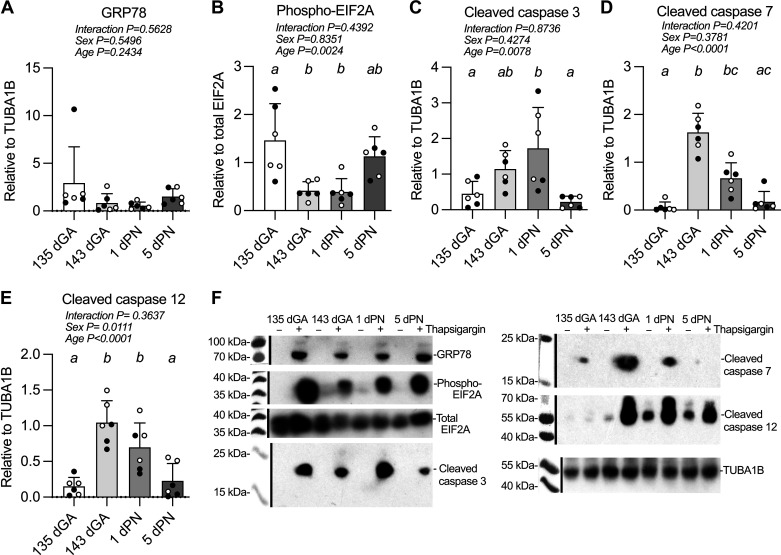

Levels of UPR proteins (Fig. 2, A, B, and F) and apoptosis pathway proteins (Fig. 2, C–F) were compared following the treatment of cultured cardiomyocytes with thapsigargin. Induced expression of the 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), also referred to as BiP or HSPA5, was unchanged by developmental age (Fig. 2A). Induced phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) was low near the time of birth (Fig. 2B), such that between 135 dGA and 143 dGA, phospho-EIF2A induction decreased 72% (P = 0.0096) and remained low at 1 dPN (P = 0.0080).

Figure 2.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced ER stress response- and apoptosis-related protein expression in cultured cardiomyocytes. Thapsigargin was used to create ER stress in primary cardiomyocyte cultures. Measurements were made of 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) protein (78 kDa) (A), eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) protein phosphorylation (38 kDa) (B), cleaved caspase 3 protein (17 kDa) (C), cleaved caspase 7 protein (18 kDa) (D), cleaved caspase 12 protein (42 kDa) (E), and representative Western blot images (white balance and saturation adjusted for visual assessment) (F). n = 3 females (open symbols) and 3 male (closed symbols) animals per group. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified, multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal. Raw values are shown with means ± SD.

Cleavage of caspases 3, 7, and 12 followed a different pattern from phospho-EIF2A, with thapsigargin stimulating cleavage immediately before and after birth. Cleaved caspase 3 levels were 3.8-fold higher at 1 dPN compared with 135 dGA (P = 0.0380), and 7.8-fold higher compared with 5 dPN (Fig. 2C; P = 0.0118). Cleaved caspase 7 levels were 25-fold higher at 143 dGA than at 135 dGA (P < 0.0001) and remained 10-fold higher at 1 dPN than at 135 dGA (Fig. 2D; P = 0.0123); the peak at 143 dGA was 2.4-fold greater than levels at 1 dPN (P = 0.0001) and ninefold greater than at 5 dPN (P < 0.0001). Caspase 12 cleaved levels increased 6.9-fold at 143 dGA over 135 dGA (Fig. 2E; P < 0.0001) and remained elevated at 1 dPN (P = 0.0045), before declining at 5 dPN (vs. 143 dGA P < 0.0001; vs. 1 dPN P = 0.0152). Furthermore, cleaved caspase 12 levels were on average 2.3-fold higher in females than in males across all ages (P = 0.0111).

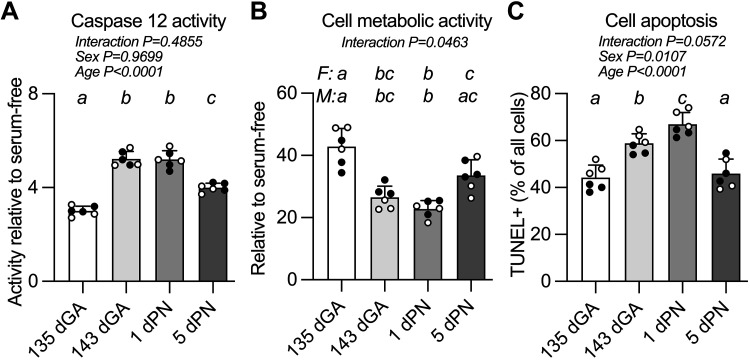

Thapsigargin-Induced Cell Dysfunction and Death Is Greatest near the Time of Birth

Survival responses were compared between ages following treatment of cultured cardiomyocytes with thapsigargin. Stimulated caspase 12 activity was higher in cultured cardiomyocytes from the immediate time around birth compared with earlier or later (Fig. 3A). Between 135 dGA and 143 dGA, activity increased 74% (P < 0.0001), whereas between 1 dPN and 5 dPN, activity decreased by 23% (P < 0.0001). There was an interaction between age and sex on cardiomyocyte survival as measured by mitochondrial activity assay (Fig. 3B). In cardiomyocytes from female fetuses, the highest rate of survival in response to ER stress was in cells from 135 dGA (vs. 143 dGA and 1 dPN P < 0.0001, vs. 5 dPN P = 0.0019), and then recovered somewhat at 5 dPN (vs. 1 dPN P = 0.0294). In cardiomyocytes from male fetuses, survival was highest in cells from both 135 dGA and 5 dPN (135 dGA vs. 143 dGA P = 0.0474; vs. 1 dPN P = 0.0013; 5 dPN vs. 1 dPN P = 0.0167). Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay (Fig. 3C). Cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by ER stress was lowest at 135 dGA (vs. 143 dGA and 1 dPN P < 0.0001) and 5 dPN (vs. 143 dGA P = 0.0003; vs. 1 dPN P < 0.0001), and highest at 1 dPN (vs. 143 dGA P = 0.019).

Figure 3.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced caspase 12 activity and cell death in cultured cardiomyocytes. Thapsigargin was used to create ER stress in primary cultures of cardiomyocytes and measurements were made of caspase 12 activity levels were assessed (A), cell survival as indicated by metabolic activity (B), and cell apoptosis as measured by TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining (C). n = 3 female (F; open symbols) and 3 male (M; closed symbols) animals per group. Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of caspase 12 activity, were performed in triplicate. Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of cell metabolic activity, were performed in triplicate and was repeated twice. Cell culture and treatment, and assessment of cell apoptosis, were repeated three times. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified, multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal. Raw values are shown with means ± SD.

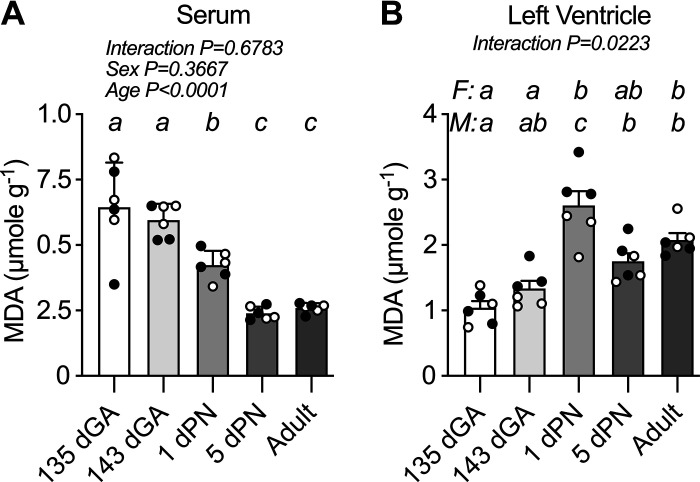

In Vivo Lipid Peroxidation Is High in Fetal Serum but Peaks in Neonatal Heart

Lipid peroxidation by free radicals was measured by the oxidative stress byproduct MDA. Serum MDA levels declined by ∼60% over the perinatal period (Fig. 4A). There were no differences between the fetal ages, but serum MDA decreased by about a third between 143 dGA and 1 dPN (P = 0.0330), and by a similar amount between 1 dPN and 5 dPN (P = 0.0188). The effect of perinatal age on LV lipid peroxidation was statistically different between males and females, although they followed the same trajectory (Fig. 4B). In both females and males, LV lipid peroxidation was similar between fetal ages and then peaked immediately after birth (1 dPN vs. 143 dGA P = 0.0009 and P < 0.0001, respectively). The sexes differed in whether there was a slight decline between 1 dPN and 5 dPN (in males P = 0.0007).

Figure 4.

Lipid peroxidation in sheep serum and left ventricle. Oxidative stress as measured by levels of lipid peroxidation by-product malondialdehyde (MDA) in serum (A) and myocardium (B). n = 3 female (F; open symbols) and 3 male (M; closed symbols) animals per group. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified, multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). Raw values are shown with means ± SD. dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal.

In Utero ER Stress Response-Related mRNA and Protein Expression Level Regulation Is Variable in the Perinatal Period

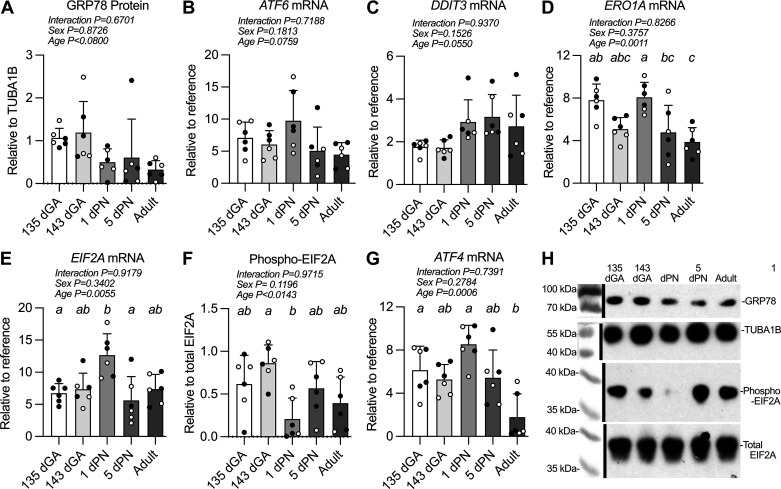

GRP78 protein was unchanged by age (Fig. 5, A and H). Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), which upon release of GRP78 can activate DDIT [also known as C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP)], was not transcriptionally regulated in the perinatal period (Fig. 5B). Accordingly, the mRNA expression levels of DDIT3 were unchanged in the LV by age (Fig. 5C). However, ER oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1A) levels, which are regulated by DDIT3, are regulated in the perinatal period (Fig. 5D), declining after birth (1 dPN vs. 5 dPN P = 0.0389, vs. adult P = 0.0052).

Figure 5.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response-related mRNA and protein expression levels in sheep left ventricle. Measurements were made from left ventricular myocardium of 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) (A), also known as BiP or HSPA5, protein (78 kDa); activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) mRNA (B); C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) (C), also known as DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3) mRNA; endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1A) mRNA (D); eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (EIF2A) mRNA (E); EIF2A protein phosphorylation (38 kDa) (F); activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) mRNA (G); and representative Western blot images (white balance and saturation adjusted for visual assessment) (H). n = 3 female (open symbols) and 3 male (closed symbols) animals per group. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal. Raw values are shown with means ± SD.

EIF2A mRNA expression peaked after birth (Fig. 5E); between 135 dGA and 1 dPN, EIF2A levels almost doubled (P = 0.0249), and from 1 dPN to 5 dPN they decreased 56% (P = 0.0055). EIF2A phosphorylation decreased profoundly between 143 dGA and 1 dPN (Fig. 5, F and H; P = 0.0113). Downstream of phospho-EIF2A is activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), mRNA levels of which remained constant in the LV across the perinatal period (Fig. 5E), but levels in the adult were lower (vs. 135 dGA P = 0.0212).

In Utero Apoptosis-Related Expression Levels Peak near the Time of Birth

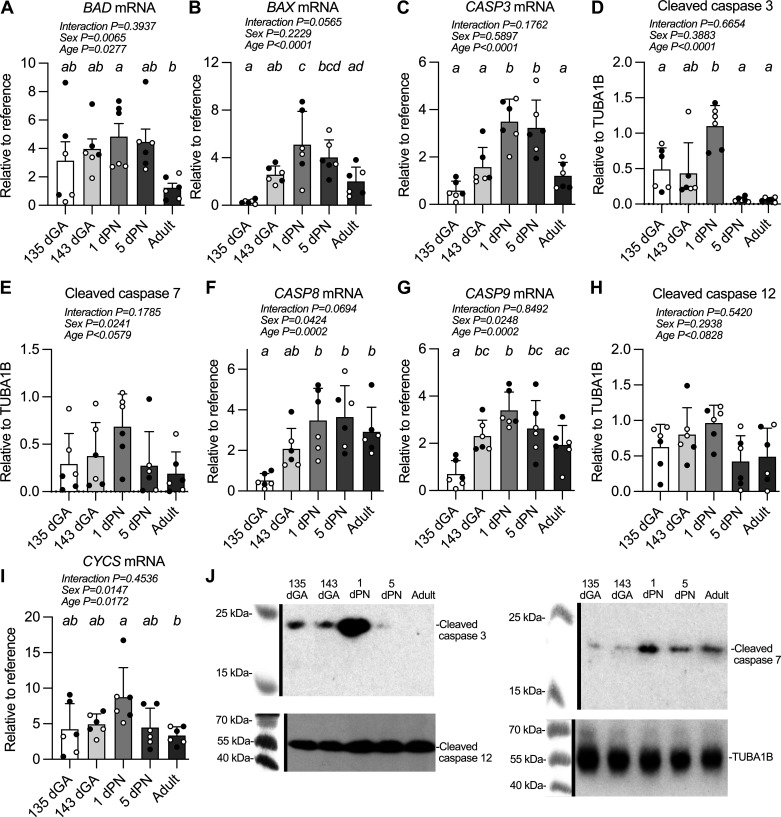

In the LV, mRNA expression levels of proapoptotic genes generally increased with age or peaked just after birth. The mRNA levels of Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) were affected by both perinatal age and sex (Fig. 6A). Levels were higher at 1 dPN than in the adult (P = 0.0361). Levels of Bcl-2-associated X-protein (BAX) mRNA peaked in the LV after birth (Fig. 6B), with expression at 1 dPN 16-fold greater than at 135 dGA (P < 0.0001), and 1.5-fold that in the adult (P = 0.0082).

Figure 6.

Apoptosis-related mRNA and protein expression levels in sheep left ventricle. Measurements were made from the left ventricular myocardium of Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD) mRNA (A), Bcl-2-associated X-protein (BAX) mRNA (B), caspase 3 (CASP3) mRNA (C), cleaved caspase 3 protein (17 kDa) (D), cleaved caspase 7 protein (18 kDa) (E), caspase 8 (CASP8) mRNA (F), caspase 9 (CASP9) mRNA (G), cleaved caspase 12 protein (42 kDa) (H), cytochrome-c (CYCS) mRNA (I), and representative Western blot images (white balance and saturation adjusted for visual assessment) (J). n = 3 female (open symbols) and 3 male (closed symbols) animals per group. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal. Raw values are shown with means ± SD.

LV mRNA levels of the apoptosis effector caspase 3 also peaked after birth (Fig. 6C); there was more than a fold increase in expression from 143 dGA to 1 dPN (P = 0.0045), whereas expression at 1 dPN was almost twofold greater than in the adult (P = 0.0007). Cleaved apoptosis effector caspase 3 protein peaked immediately after birth (Fig. 6, D and J). Levels at 1 dPN were ∼2.2-fold higher than levels at 135 dGA (P = 0.0126; 1 dPN vs. 143 dGA P = 0.055) and 17-fold higher than 5 dPN and adult (both P < 0.0001).

Cleaved effector caspase 7 did not change significantly with age (Fig. 6, E and J). Caspase 8 mRNA expression was affected by both sex and age in the perinatal period (Fig. 6F). Levels were low in the fetus and rose to a plateau after birth; expression increased more than fivefold between 135 dGA and 1 dPN (P = 0.0008). Expression levels of caspase 9 mRNA were also affected by both sex and age in the perinatal period (Fig. 6G). Levels increased immediately before birth with a twofold increase in expression between 135 dGA and 143 dGA (P = 0.0219).

Levels of cleaved activator caspase 12 were unchanged by developmental age (Fig. 6, H and J).

Levels of cytochrome-c (CYCS) mRNA were affected by sex and age in the perinatal period (Fig. 6I). Levels were 160% higher at 1 dPN than in the adult (P = 0.0184).

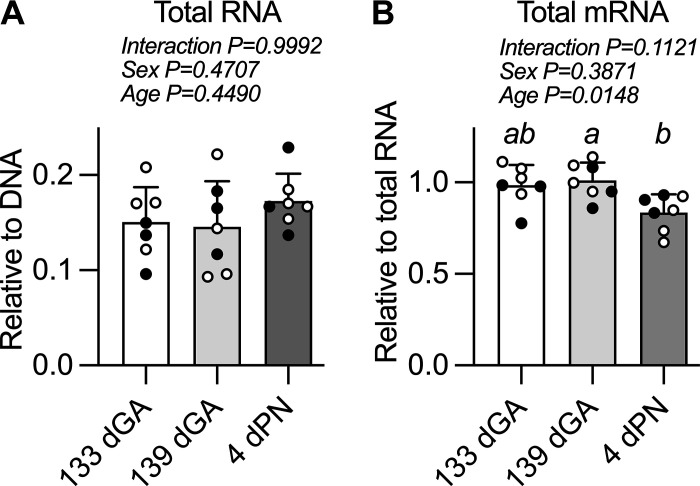

Total mRNA Levels Decline in the Perinatal Period

The ratio of myocardial total RNA to DNA was not different between ages (Fig. 7A). The ratio of mRNA to total RNA did change by age in the perinatal period (Fig. 7B) such that mRNA levels were lower in the postnatal period (vs. 139 dGA P = 0.0197).

Figure 7.

Total nucleic acids in sheep left ventricle. Measurements were made from the left ventricular myocardium of total RNA levels (A) and total messenger RNA (mRNA) levels (B). n = 4 female (open symbols) and 3 male (closed symbols) animals per group. Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance; if justified multiple comparisons were performed by the Šidák test (ages with different letters are statistically different). dGA, days of gestational age; dPN, day postnatal. Raw values are shown with means ± SD.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that in culture, the magnitude of ER stress and apoptotic responses to a similar ER stress changed dramatically with cardiomyocyte age over the weeks surrounding birth. In the same period, levels of expression and activation of the same regulatory molecules were changed in the in utero myocardium. These in utero changes may be due to changes in ER pathway sensitivity revealed by the in vitro experiments, they may be inherently responsive to dynamic changes in systemic and cardiac ROS as suggested by lipid peroxidation, or they may be due to factors not assessed in this study such as increased bulk protein translation. Because we found that changes in ER pathway components were accompanied by changes in caspase pathway activation, this study supports a role for the ER stress response pathways in the regulation of cardiomyocyte number in the normally developing perinatal heart.

Sensitivity of ER Stress Pathways in Cardiomyocytes

The UPR is an adaptive response to ER stress that can either reduce the burden of unfolded proteins in the cell to enhance survival or activate proapoptotic pathways. Responses in cultured cardiomyocytes to thapsigargin demonstrated differences in this balance across perinatal ages. The response to the stressor was generally similar at 143 dGA and 1 dPN, in contrast to the responses at 135 dGA and 5 dPN. Phosphorylation of EIF2A was less responsive in the period closest to birth. It appears that IRE1 was disinhibited, as levels of caspase 12 cleavage and activity were more inducible at 143 dGA in a mirror image to the changes in phospho-EIF2A (24). Downstream caspase targets also increased, and cell death in response to stress was augmented at 143 dGA and 1 dPN. The differences in cardiomyocyte response to ER stress at different ages suggest that the response shifts from prosurvival toward proapoptosis in the days immediately before and after birth.

Regulation of Myocardial ER Stress and Apoptosis In Utero

If a large increase in unfolded proteins exceeds the threshold capacity of the constitutive levels of GRP78, PERK is disinhibited and EIF2A is phosphorylated, which protects the cell by global inhibition of translation while upregulating a selective set of genes including those involved in the UPR (24). One possible outcome of EIF2A phosphorylation is transcription inhibition. We found that mRNA levels were decreased in the newborn period despite a transient decrease in EIF2A phosphorylation at 1 dPN. Prolonged or intense EIF2A activation leads to the activation of proapoptotic signaling pathways. The conditions leading to suppression at 1dPN are unknown. Low ERO1A levels at 143 dGA (compared with 1 dPN) could contribute to ER stress if it impaired regeneration of protein disulfide isomerase, which is responsible for folding proteins in the ER. It is important to note that determining the presence of ER stress is especially challenging in vivo (29), and what constitutes “prolonged” or “intense” activation of the ER stress pathway is unclear in this context. Nevertheless, we did observe a peak in apoptotic activation by caspase 3 at 1 dPN.

In this same period, the fetal heart is undergoing a transition in modality of growth (1, 36, 37). Before 135 dGA, considerable cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to expansion in the number of cells in the ventricles (2). At this time, cellular enlargement accelerates sharply to grow the heart. Terminal differentiation at 135 dGA is ∼50%, and by birth, it is above 75%. Finally, between 135 dGA and birth, cardiomyocyte number is abruptly reduced. Signaling events controlling these growth and maturational effects are likely to be linked and important to the regulation of cardiomyocyte number.

Reactive Oxygen in the Fetus

The generation of ROS and the cellular defenses against ROS change over the course of normal development (38–44). In most fetal tissues studied, enzymatic and nonenzymatic defenses against ROS increase steeply as term approaches (39–41, 44), consistent with our finding of reduced serum lipid peroxidation immediately after birth. When we looked specifically in the heart, however, we found that fetal levels of lipid peroxidation were lower than in the neonate. There are several important changes in the perinatal period that may contribute to pre- and postnatal differences in ROS generation. Increased oxygen levels with air breathing and the cardiac switch to lipid oxidation as the primary source of energy may contribute to increased ROS production at birth. Correspondingly, toward the end of gestation, there is a modest rise in myocardial glutathione peroxidase, although not superoxide dismutase 1 or 2, or catalase (12, 39). In contrast, ROS production in the fetal myocardium may be driven by high fetal levels of ERO1A, which produces hydrogen peroxide when it regenerates disulfide isomerase.

Apart from the differences between fetal and postnatal levels of myocardial lipid peroxidation, the peak on the first day of postnatal life is notable. This peak also corresponds to the suppressed tissue levels of phospho-EIF2A and the peak in cleaved caspases.

Sex Differences

The direction and magnitude of the changes in measured variables with perinatal age were substantially similar between males and females. When all data were considered together, the minor differences in the magnitude of effect or timing between the sexes were not observed to display a consistent pattern suggestive of biological significance.

Conclusions

The role of the UPR in myocardial protein homeostasis as well as ER stress response contributing to cardiac disease are well described (24, 25). However, few studies describe the role of the UPR and the ER stress response during cardiac development. We found that in the weeks surrounding birth, there is dynamic regulation of the proteins involved in ER proteostasis, ER stress, and the apoptosis cascade. Apoptotic signaling is more readily activated in the myocardium through ER stress in the week before birth, leading to widespread caspase cleavage in the newborn heart. These pathways are clearly important for regulating normal development and maturation in the healthy perinatal heart.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant R01HL142483 (to S.S.J.) and Collins Medical Trust (to K.B.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.B., S.L., and S.S.J. conceived and designed research; K.B., H.M.E., S.L., and S.S.J. performed experiments; K.B., H.M.E., S.L., and S.S.J. analyzed data; K.B., H.M.E., S.L., and S.S.J. interpreted results of experiments; K.B. and S.S.J. prepared figures; K.B., S.L., and S.S.J. drafted manuscript; K.B., H.M.E., S.L., and S.S.J. edited and revised manuscript; K.B., H.M.E., S.L., and S.S.J. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burrell JH, Boyn AM, Kumarasamy V, Hsieh A, Head SI, Lumbers ER. Growth and maturation of cardiac myocytes in fetal sheep in the second half of gestation. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 274: 952–961, 2003. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jonker SS, Louey S, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL, Faber JJ. Timing of cardiomyocyte growth, maturation, and attrition in perinatal sheep. FASEB J 29: 4346–4357, 2015. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisén J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 324: 98–102, 2009. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adler CP, Costabel U. Cell number in human heart in atrophy, hypertrophy, and under the influence of cytostatics. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab 6: 343–355, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thornburg K, Jonker S, O'Tierney P, Chattergoon N, Louey S, Faber J, Giraud G. Regulation of the cardiomyocyte population in the developing heart. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 106: 289–299, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mendoza A, Karch J. Keeping the beat against time: mitochondrial fitness in the aging heart. Front Aging 3: 951417, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fragi.2022.951417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death in development. Cell 96: 245–254, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reed JC. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1: 111–121, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nrd726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez E, Siddiquee Z, Shohet RV. Apoptosis and proliferation in the neonatal murine heart. Dev Dyn 221: 302–310, 2001. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. James TN. Normal and abnormal consequences of apoptosis in the human heart. Annu Rev Physiol 60: 309–325, 1998. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kajstura J, Mansukhani M, Cheng W, Reiss K, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Quaini F, Sonnenblick EH, Anversa P. Programmed cell death and expression of the protooncogene bcl-2 in myocytes during postnatal maturation of the heart. Exp Cell Res 219: 110–121, 1995. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jonker SS, Louey S. Endocrine and other physiologic modulators of perinatal cardiomyocyte endowment. J Endocrinol 228: R1–R18, 2016. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karimi M, Wang LX, Hammel JM, Mascio CE, Abdulhamid M, Barner EW, Scholz TD, Segar JL, Li WG, Niles SD, Caldarone CA. Neonatal vulnerability to ischemia and reperfusion: Cardioplegic arrest causes greater myocardial apoptosis in neonatal lambs than in mature lambs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 127: 490–497, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caldarone CA, Barner EW, Wang L, Karimi M, Mascio CE, Hammel JM, Segar JL, Du C, Scholz TD. Apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction in the early postoperative neonatal lamb heart. Ann Thorac Surg 78: 948–955, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hammel JM, Caldarone CA, Van Natta TL, Wang LX, Welke KF, Li W, Niles S, Barner E, Scholz TD, Behrendt DM, Segar JL. Myocardial apoptosis after cardioplegic arrest in the neonatal lamb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 125: 1268–1275, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mattern J, Gemmell A, Allen PE, Mathers KE, Regnault TRH, Stansfield BK. Oral pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) during pregnancy increases cardiomyocyte endowment in spontaneous IUGR guinea pigs. J Dev Orig Health Dis 14: 321–324, 2023. doi: 10.1017/S2040174423000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tipple TE, Ambalavanan N. Oxygen toxicity in the neonate: thinking beyond the balance. Clin Perinatol 46: 435–447, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hernández-García D, Wood CD, Castro-Obregón S, Covarrubias L. Reactive oxygen species: a radical role in development? Free Radic Biol Med 49: 130–143, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thompson LP, Al-Hasan Y. Impact of oxidative stress in fetal programming. J Pregnancy 2012: 582748, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/582748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barbosky L, Lawrence DK, Karunamuni G, Wikenheiser JC, Doughman YQ, Visconti RP, Burch JB, Watanabe M. Apoptosis in the developing mouse heart. Dev Dyn 235: 2592–2602, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fletcher AJ, Gardner DS, Edwards CM, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Development of the ovine fetal cardiovascular defense to hypoxemia towards full term. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H3023–H3034, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00504.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harding R, Poore ER, Bailey A, Thorburn GD, Jansen CA, Nathanielsz PW. Electromyographic activity of the nonpregnant and pregnant sheep uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 142: 448–457, 1982. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863: 2977–2992, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Minamino T, Komuro I, Kitakaze M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 107: 1071–1082, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ren J, Bi Y, Sowers JR, Hetz C, Zhang Y. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol 18: 499–521, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00511-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neill G, Masson GR. A stay of execution: ATF4 regulation and potential outcomes for the integrated stress response. Front Mol Neurosci 16: 1112253, 2023. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2023.1112253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chattergoon N, Louey S, Jonker SS, Thornburg KL. Thyroid hormone increases fatty acid use in fetal ovine cardiac myocytes. Physiol Rep 11: e15865, 2023. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. The SERCA pump as a therapeutic target: making a “smart bomb” for prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 4: 14–22, 2005. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.1.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oslowski CM, Urano F. Measuring ER stress and the unfolded protein response using mammalian tissue culture system. Methods Enzymol 490: 71–92, 2011. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385114-7.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kirby MS, Sagara Y, Gaa S, Inesi G, Lederer WJ, Rogers TB. Thapsigargin inhibits contraction and Ca2+ transient in cardiac cells by specific inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump. J Biol Chem 267: 12545–12551, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Z, Guo J, Bian Y, Zhang M. Intermedin protects thapsigargin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in cardiomyocytes by modulating protein kinase A and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase. Mol Med Rep 23: 107, 2021. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Tierney PF, Chattergoon NN, Louey S, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits angiotensin II-stimulated proliferation in fetal cardiomyocytes. J Physiol 588: 2879–2889, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davis L, Musso J, Soman D, Louey S, Nelson JW, Jonker SS. Role of adenosine signaling in coordinating cardiomyocyte function and coronary vascular growth in chronic fetal anemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R500–R508, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00319.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garcia de la Cadena S, Massieu L. Caspases and their role in inflammation and ischemic neuronal death. Focus on caspase-12. Apoptosis 21: 763–777, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Denisenko O, Lin B, Louey S, Thornburg K, Bomsztyk K, Bagby S. Maternal malnutrition and placental insufficiency induce global downregulation of gene expression in fetal kidneys. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2: 124–133, 2011. doi: 10.1017/S2040174410000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson DF, Jonker SS, Louey S, Cheung CY, Brace RA. Regulation of intramembranous absorption and amniotic fluid volume by constituents in fetal sheep urine. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R506–R511, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00175.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jonker SS, Zhang L, Louey S, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL, Faber JJ. Myocyte enlargement, differentiation, and proliferation kinetics in the fetal sheep heart. J Appl Physiol (1985) 102: 1130–1142, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00937.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. Lipid peroxidation in developing fetal guinea pig brain during normoxia and hypoxia. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 45: 129–135, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayashibe H, Asayama K, Dobashi K, Kato K. Prenatal development of antioxidant enzymes in rat lung, kidney, and heart: marked increase in immunoreactive superoxide dismutases, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase in the kidney. Pediatr Res 27: 472–475, 1990. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Song Y, Pillow JJ. Ontogeny of proteolytic signaling and antioxidant capacity in fetal and neonatal diaphragm. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 295: 864–871, 2012. doi: 10.1002/ar.22436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carbone GM, St Clair DK, Xu YA, Rose JC. Expression of manganese superoxide dismutase in ovine kidney cortex during development. Pediatr Res 35: 41–44, 1994. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Konstantinova SG, Russanov EM. Effect of pregnancy and fetal development on sheep liver superoxide dismutase activity. Res Vet Sci 45: 287–290, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mutinati M, Piccinno M, Roncetti M, Campanile D, Rizzo A, Sciorsci R. Oxidative stress during pregnancy in the sheep. Reprod Domest Anim 48: 353–357, 2013. doi: 10.1111/rda.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torres-Cuevas I, Parra-Llorca A, Sánchez-Illana A, Nuñez-Ramiro A, Kuligowski J, Cháfer-Pericás C, Cernada M, Escobar J, Vento M. Oxygen and oxidative stress in the perinatal period. Redox Biol 12: 674–681, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.