Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), COVID-19, lipidomics, metabolomics

Abstract

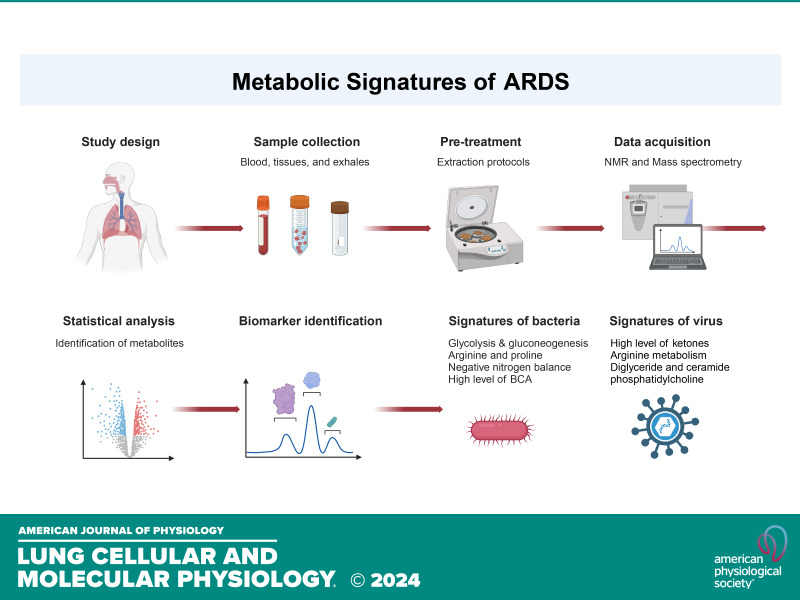

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a fatal pulmonary disorder characterized by severe hypoxia and inflammation. ARDS is commonly triggered by systemic and pulmonary infections, with bacteria and viruses. Notable pathogens include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus aureus, Enterobacter species, coronaviruses, influenza viruses, and herpesviruses. COVID-19 ARDS represents the latest etiological phenotype of the disease. The pathogenesis of ARDS caused by bacteria and viruses exhibits variations in host immune responses and lung mesenchymal injury. We postulate that the systemic and pulmonary metabolomics profiles of ARDS induced by COVID-19 pathogens may exhibit distinctions compared with those induced by other infectious agents. This review aims to compare metabolic signatures in blood and lung specimens specifically within the context of ARDS. Both prevalent and phenotype-specific metabolomic signatures, including but not limited to glycolysis, ketone body production, lipid oxidation, and dysregulation of the kynurenine pathways, were thoroughly examined in this review. The distinctions in metabolic signatures between COVID-19 and non-COVID ARDS have the potential to reveal new biomarkers, elucidate pathogenic mechanisms, identify druggable targets, and facilitate differential diagnosis in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remains a significant contributor to intensive care unit (ICU) mortality, particularly highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. With an approximate mortality rate of 40% in most studies (1–3), ARDS continues to pose substantial clinical challenges despite advancements in basic and clinical research. Presently, pharmacotherapy for ARDS remains ineffective, necessitating primarily supportive interventions such as lung protective ventilation and conservative fluid management strategies. Hence, there is a critical need to adopt cutting-edge approaches, including trans-omics and machine learning algorithms, to deepen our understanding of ARDS by either infectious or noninfectious causes. To explore the omics basis for the differences between COVID and non-COVID ARDS, we conducted a scoping review of the existing literature. We used the following strategy to search for relevant literature in the National Library of Medicine database: “biomarkers[ti] AND (COVID[ti] OR respiratory distress[ti]) AND (metabolic[ti] OR metabolism[ti] OR metabolome[ti] OR metabolomics[ti]),” as well as “(COVID-19[ti] OR SARS-CoV-2[ti] OR respiratory disease[ti]) AND (metabolic[ti] OR metabolome[ti] OR metabolomics[ti] OR metabolomic[ti]) AND (exhaled breath OR edema fluid OR BALF OR lavage OR bronchoalveolar lavage), limited to publications within the past 5 years.

This review offers new insights into the use of metabolomics for diagnosing ARDS caused by bacterial and viral infections. Given the persistent influence of systemic inflammation and alveolar damage on metabolic dysregulation during disease progression, we hypothesize that metabolomic approaches, supported by in vitro, in vivo, and human studies, hold promise for predicting ARDS outcomes and developing innovative treatments. Metabolomic analyses can delineate both endogenous and exogenous metabolites within a single biological sample, thus helping us determine the perturbations in biochemical pathways associated with disease states. In this review, we compared the metabolomics differences between bacteria- and virus-caused ARDS (Table 1). Our focus was on discerning the metabolic pathways associated with ARDS and differentiating those induced by bacterial and viral infections. The research results obtained from blood and tissues beyond the lung were also reviewed (26, 33, 34).

Table 1.

Comparison of metabolic pathways between COVID-19 and other ARDS

| Sample | Non-COVID | COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| EBC | Elevated octane, acetaldehyde, and 3-methylheptane (4). Reduced isoprene, increased in pentane/isoprene (5). | Acetonitrile treatment inactivates the virus, which suppresses the metabolic features (6). |

| Moreover, elevated productions of ketone bodies, short-chain fatty acids metabolism as well as active of cAMP signaling pathways were observed in the exhaled breath condensate from patients with COVID-19 (7). | ||

| Inflammatory oxylipin shifts and dysregulation could be used to monitor COVID-19 disease progression or severity including P450, COX, 15-LOX metabolism related pathways (8). | ||

| BAL | Elevated amino acids concentration, TCA cycles, nucleotide biosynthesis, and glycolysis pathways (9). Elevated amino acid metabolism, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, fatty acid biosynthesis, phospholipids, and purine metabolism (10). Elevated isoleucine, leucine, valine, lysine/arginine, tyrosine, and threonine (11). Elevated taurine, threonine, glutamate, proline, and lysine/arginine (12). | Upregulated arginine biosynthesis, glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis, thyroid hormone synthesis, and pyrimidine metabolism (13). |

| Elevated levels of eicosanoid metabolites were found in patients with severe COVID-19, which are highly associated with quantitative anomalies of circulating neutrophils in the patients (14). | ||

| Edema fluid | Elevated alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolic pathway, and lysine degradation pathways (15). | Altered monomyristin, monolaurin, heptadecanoic acid-glycerine-(1)-monoester, nonadecanoic acid-glycerine-(1)-monoester, pentadecanoic acid-glycerine-(1)-monoester, dihydroxypropyl icosanoate, 2-tert-butyl-4-ethylphenol, and monostearin (16). |

| Lung biopsies | Upregulated nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, and folate biosynthesis (13). | |

| Serum | Elevated proline, glutamate, phenylalanine, valine, and phenylalanine metabolism (11). Increased in N-acetylglycoproteins, acetoacetate, lactate and creatinine, histidine, formate and aromatic amino acids, lipid metabolism, and glycolysis pathway (17). Decreased glucose, alanine, glutamine, and fatty acids (18). | Altered tryptophan metabolism (19). Dysregulated apolipoproteins including APOA1, APOA2, APOH, APOL1, APOD, and APOM. Significant activation of the kynurenine pathway. Enriched metabolites of kynurenate, kynurenine, and 8-methoxykynurenate (20). High ketone bodies (acetoacetic acid, 3-hydroxybutyric acid, and acetone) and 2-hydroxybutyric acid, hepatic glutathione synthesis (21). Decreased eicosanoid and docosanoid lipid mediator products of ALOX12 and COX2; increased products of ALOX5 and cytochrome p450 (22). |

| Plasma | Increased in 2-hydroxybutyric acid, phenylalanine, aspartic acid, carbamic acid, arginine, and ornithine metabolism (23). Altered phenylalanine metabolism (24). | Elevated malic acid of the TCA cycle and carbamoyl phosphate of the urea cycle (25). Differential gelsolin and metabolite citrate or plasmalogens and apolipoproteins between COVID vs. non-COVID (26). Increased triacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines, prostaglandin E2, and arginine, and decreased betaine and adenosine (27). Elevated cystathionine, ethanolamine, glucose, α-1-acid glycoprotein signal A and B, kynurenine, 1-methylhistidine, and 3-methylhistine (28). Dominated kynurenine (29). Altered glycerophospholipid metabolism (30). Altered lysophosphatidylcholine (LPCs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), and triglycerides (31). Deceased patients with COVID-19 had higher metabolites associated with secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) activity and mitochondrial dysfunction (32). |

ALOX12, arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase; APO, apolipoprotein; BAL, bronchioalveolar lavage; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2; EBC, exhaled breath condensate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle. N stands for the number of subjects per study. Virus-specific metabolites are in italic font.

COMMON METABOLIC PATHWAYS SHARED BY NON-COVID- AND COVID-ASSOCIATED ARDS

Multiple metabolic pathways have been identified to be associated with the severity of ARDS. Bos et al. (4) used GC-MS analysis of exhaled breath to compare 23 ventilated patients with ARDS and 20 ventilated ICU control patients. Significant differences were observed between ARDS and control patients in three volatile organic compounds: octane, acetaldehyde, and 3-methylheptane Evans et al. (9) conducted metabolic profiling in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) to evaluate differences between 18 patients with ARDS (sepsis-induced, pneumonia-induced, and aspiration-induced) and 8 healthy controls. This study demonstrated increased levels of guanosine, xanthine, hypoxanthine, and lactate and a decreased level of phosphatidylcholine in patients with ARDS (9). Similarly, Rai et al. (10) used NMR to analyze the metabolic profiling of mini-BALF samples to compare 21 patients with ARDS [10 ARDS and 11 acute lung injury (ALI)] and 9 ventilated control patients.

Significant differences in the concentrations of essential amino acids, including isoleucine, valine, lysine, leucine, threonine, and proline, were observed between the control group and those with ALI/ARDS (10). Common metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis, ketone production, and arginine metabolism, are shared by both non-COVID and COVID-associated ARDS. These pathways are correlated with pathogen infections, immune system dysregulation, and cell death. Understanding and delineating these metabolic pathways could serve as tools for early disease detection.

METABOLIC PATHWAYS SPECIFIC TO NON-COVID-ASSOCIATED ARDS

During the development of ARDS due to bacterial infection, the host and bacterial cells undergo various metabolic changes that can be monitored and analyzed using different sample types in metabolomics studies. Elevated levels of acetaldehyde and other ketones, such as octane and pentane, were detected using GC-MS (4, 5). These volatile compounds could be produced by either the colonized bacteria (35) or by host leukocytes (36) and neutrophils (37). Given the common occurrence of neutrophil infiltration in patients with ARDS, profiling these ketones could prove valuable in identifying diagnostic biomarkers for ARDS. Results from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) studies suggest that the most dysregulated pathways include glycolysis, as well as the production and utilization of amino acids. Metwaly et al. (38) conducted a comprehensive analysis across multiple studies and identified a biological profile of deranged energy metabolism (activation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis), increased collagen synthesis and fibrosis (arginine and proline metabolism), negative nitrogen balance (urea cycle), inflammation (glycerophospholipid metabolism), and accelerated cellular turnover (purine and pyrimidine metabolism), which is commonly perceived in patients with ARDS. In addition to being a key amino acid for glutathione synthesis, glutamate metabolism plays a crucial role in immunomodulation, particularly through its prominent involvement in mediating T cell-mediated immunity via glutamate receptors (39). Consistent with previous studies, both proline and glutamate have been linked to increased abnormalities and correlated with dysfunctional metabolism in ARDS (9, 15). Furthermore, the levels of phenylalanine and phenylacetylglutamine were found to be significantly elevated in nonsurvivors compared with survivors of ARDS (24). The most significantly altered pathway observed between nonsurvivors and survivors of patients with ARDS in this study was phenylalanine metabolism. In vivo animal experiments have indicated that elevated levels of phenylalanine may be linked to more severe lung injury and increased mortality in ARDS (24). Consistent with previous studies, higher levels of branched chain amino acids (BCA) (essential amino acids comprising leucine, isoleucine, and valine) in ARDS, which are related to protein catabolism, have been observed in ARDS. However, due to the complex nature of metabolite interactions and analytical variability, further validation is needed before considering them as reliable clinical biomarkers. In addition, an elevated level of phenylalanine concentration has been reported in patients with ARDS in multiple studies (11, 18, 24). The elevation of phenylalanine could be due to bacterial and viral infections (40). A similar increase was also observed during experimentally induced infections in dogs (41), rats (42), and monkeys (40). Therefore, this elevation of phenylalanine is characteristic of the inflammatory process. Moreover, methylguanidine, an index of hydroxyl radical formation, was also found to be increased in ARDS (43). This finding aligns with previous reports indicating that methylguanidine is a serum marker of lung injury in rat models of sepsis-induced ALI (44) and in patients with leptospirosis (45). Interestingly, methylguanidine, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, was used as an anti-inflammatory treatment for acute inflammation (46, 47). These metabolic signatures are commonly observed in patients with ARDS and could provide valuable insights into its pathophysiology and potential avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions.

METABOLIC PATHWAYS SPECIFIC TO COVID-ASSOCIATED ARDS

During the COVID-19 pandemic, several metabolomic analyses were used to investigate the metabolic changes associated with the severity of the disease. Furthermore, these metabolic changes were associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and organ dysfunction, which are common complications of severe COVID-19. One study found that individuals infected with COVID-19 often exhibit elevated levels of certain metabolites, such as lactate, creatinine, and proinflammatory cytokines (48). Similarly, patients with COVID were found to have abnormally high levels of ketone bodies (acetoacetic acid, 3-hydroxybutyric acid, and acetone) and 2-hydroxybutyric acid, which serves as an indicator of hepatic glutathione synthesis and a marker of oxidative stress (21). Another study observed increased levels of triacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines, prostaglandin E2, and arginine in patients with COVID-19, alongside decreased levels of betaine and adenosine. These changes were associated with pulmonary carbon monoxide-diffusing capacity and total lung capacity (27). Similarly, diglyceride (17:0_17:1) and ceramide (d18:1/23:0), ceramide (d18:1/18:0), and ceramide (d18:1/26:1) were the most discriminating biomarkers for distinguishing patients with COVID from non-COVID patients (49). The variability in metabolomics findings could arise from several factors, including differences in sample preparation, instrument sensitivity and accuracy, experimental design, and data analysis methods. Of utmost significance, the high degree of biological variation between individuals can make it challenging to identify consistent metabolic changes across diverse patient populations with dynamic disease states. The activation of the kynurenine pathway has been observed in many studies in patients with COVID-19 (20, 28, 50). The kynurenine pathway serves as the primary route for tryptophan catabolism, essential for the synthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in the liver. Dysregulation of this pathway could result from immune system activation, leading to the accumulation of potentially neurotoxic compounds. Overall, newly identified biomarkers and their related pathways require further validation. Despite its immense potential, research on ARDS metabolomics is still in its early stages. Until now, most metabolomics studies have focused on differentiating ARDS from control subjects and establishing a metabolic signature of the disease. There are several limitations to the current approaches. First, there are multiple variations among individual studies, including differences in cohort characteristics, sample types, and data analysis methods used. Second, there is a lack of procedural standards across these studies. These standards encompass aspects such as patient recruitment, study design, case-control matching, and the standardization of sampling and preparation procedures. Third, many studies have used untargeted metabolomics analysis, which may not provide the most accurate metabolic profiling. To enhance precision, it is essential to incorporate targeted approaches and use individual metabolite standards. Given the significant variability among these studies, expanding the sample size and confirming the findings through independent validation cohorts is crucial. In addition, the usage of 13C stable isotope resolved metabolomics would be a more effective approach to validate the findings identified in untargeted metabolomics.

METABOLIC BIOMARKERS DIFFERENTIATING COVID- AND NON-COVID-INDUCED ARDS

To identify potential biomarkers for distinguishing between COVID-19 and pneumonia infections, a large-scale metabolomics study identified a panel of 25 biomarkers strongly associated with susceptibility to severe COVID-19 (OR 2.9) and severe pneumonia (OR 2.6) (51). In this study, significantly elevated levels of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), saturated fatty acids (SFAs), omega-6/omega-3 ratio, lactate, and glycoprotein acetyls are present in patients with severe pneumonia. Conversely, significantly higher concentrations of triglycerides, MUFAs, omega-6/omega-3 ratio, glucose, creatine, and glycoproteins acetyls existed in patients with severe COVID-19. Different species of MUFAs, the ratios of omega-6/omega-3, and glycoproteins are highly associated with inflammation in the lung. The presence of lactate dehydrogenase, the key enzyme responsible for lactate production, serves as a marker for tissue damage. Similarly, elevated levels of lactate and other metabolic fingerprints comparing direct and indirect ARDS were observed by using NMR and GC-MS (52). Direct ARDS demonstrates derangement of the urea cycle and branched-chain amino acid metabolism, whereas indirect ARDS primarily involves disturbances in bioenergetic pathways (52). Interestingly, direct ARDS metabolic status is similar to the derangements of bacterial infection in A549 human airway epithelial cells (53), where elevated extracellular levels of glutamate, valine, and lysine have been associated with an increase in glutamate secretion together with the cessation of cellular valine and lysine uptake. On the other hand, indirect ARDS demonstrated derangements in pyruvate and fumarate, similar to the LPS-induced endothelial dysfunction in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (54).

Furthermore, reliable biomarkers to distinguish severe COVID-19 from nonsevere COVID-19 were also explored (55). In this study, the porphyrin and purine pathways were found to be significantly elevated in the severe disease group, suggesting their potential as prognostic biomarkers. Elevated levels of cholesteryl ester CE (18:3) in nonsevere patients corresponded to significantly different blood cholesterol components, including total cholesterol and HDL (55). Akin to the previous study, increased levels of triacylglycerols, phosphatidylcholines, prostaglandin E2, and arginine, as well as decreased levels of betaine and adenosine, are found to be associated with pulmonary CO diffusing capacity and total lung capacity in patients with COVID-19 (27). Moreover, elevated productions of ketone bodies, short-chain fatty acids metabolism as well as active cAMP signaling pathways were observed in the exhaled breath condensate from patients with COVID-19 (7). Similarly, shifts in inflammatory oxylipin (products of lipid oxidation) and their dysregulation could be used to monitor disease progression or severity of COVID-19, including pathways related to P450, COX, and 15-LOX metabolism (8).

Reliable biomarkers play a crucial role in assessing the severity of ARDS for accurate diagnosis and treatment decisions However, the heterogeneous nature of biomarkers exhibits significant variations in their chemical structures, concentrations, and biological functions across different biological samples, individuals, and disease conditions. This heterogeneity in metabolomics data poses several challenges for validation. Therefore, it would be advantageous to combine metabolomics data with other clinical factors to comprehensively assess the patient’s condition.

DIVERSE METABOLIC ENDOTYPES BETWEEN COVID- AND NON-COVID-INDUCED ARDS

ARDS can be categorized into mild, moderate, and severe stages and pulmonary and extrapulmonary phenotypes based on underlying biology and severity (56). Improved classification of ARDS and its related phenotypes could not only optimize diagnosis but also improve the management, therapeutic intervention, and risk stratification of ARDS. Therefore, gaining a deeper understanding through endotype identification might enable us to stratify patients based on pathogenic mechanisms and their responses to treatments. In addition, metabolic endotypes specific to disease subtypes can be correlated with biomarker validation through epidemiological approaches. In a retrospective study on biological endotypes involving 464 patients and controls, mBALF and serum samples were analyzed using NMR spectroscopy from clinically diagnosed ARDS subtypes categorized as mild, moderate, and severe ARDS (11). This study identifies proline, glutamate, phenylalanine, and valine as serum endotypes, and lysine, arginine, tyrosine, threonine, and branched-chain amino acids (BCAs) as mBALF endotypes (11). Glutamate, as one of the key carbon sources, plays an important role in mediating T-cell activation. These results are consistent with recent findings that both proline and glutamate have been associated with increased abnormalities and correlated to dysfunctional metabolism in ARDS (9, 15). One of these studies aimed to examine undiluted pulmonary edema fluid obtained at the time of endotracheal intubation from 16 clinical phenotypes of patients with ARDS and 13 control patients with hydrostatic pulmonary edema (15). The main endotype pathways identified in this study include alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and lysine degradation (15).

Comparatively, a retrospective study included 123 patients with COVID who were stratified into asymptomatic/mild (n = 12), moderate (n = 64), and severe (n = 47) categories, along with a group of 15 healthy controls (57). In this study, an upregulation of l-kynurenine and a downregulation of l-tryptophan in severe patients with COVID were found, indicating an elevated l-kynurenine/l-tryptophan ratio. This suggests a disease-associated hyperactivation of the indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) enzyme. IDO leads the conversion of l-tryptophan into l-kynurenine in immune cells, which is strongly activated in response to interferons and inflammatory cytokines released during inflammation (58). Besides the endotypes, the metabolic signature of ARDS due to COVID-19 across different severities was also explored. The unique metabolic fingerprint was measured by comparing the hypoinflammatory subgroup (n = 68) and hyperinflammatory subset (n = 34) using NMR and GC-MS (52). Hypoinflammatory ARDS appears to exhibit a more pronounced impact on urea cycle metabolism, whereas hyperinflammatory ARDS appears to have a greater impact on serine-glycine metabolism. The specific biological pathways involved in hypoinflammatory ARDS are mainly responsible for protein breakdown (valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation) and steroid hormone synthesis (C21-steroid hormone biosynthesis and metabolism). On the other hand, the specific biological pathways impacted in hyperinflammatory ARDS mainly involve promoting inflammation (prostaglandin formation from arachidonate) and the synthesis of stress hormones (tyrosine metabolism) (52). All these results suggest that metabolomics has the potential to identify distinct subsets of patients with ARDS.

SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVES

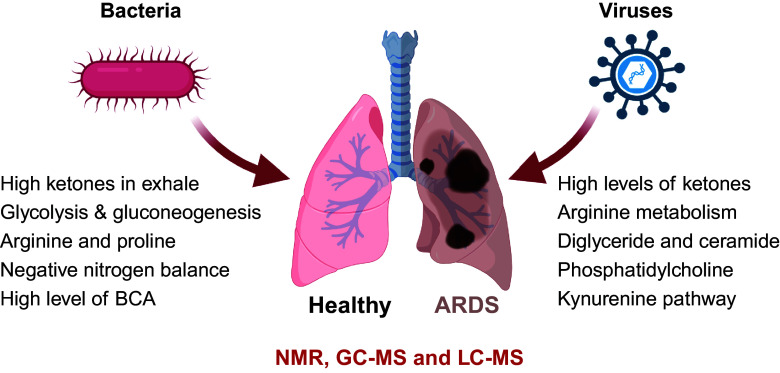

In addition to stable isotope methods, multi-omic analysis could be another approach to delineate the functional connections among different molecules. Examining the metabolites from various biological samples simultaneously, including BAL, plasma, and urine, may provide important insights into the biology of ARDS. Studies involving patients at high risk for ARDS are critical because the profile in the early phase of acute lung injury may be different from that in established ARDS and thus may provide new insights into its pathogenesis. As illustrated in Fig. 1, metabolic dysregulations in patients with ARDS stem from various factors. Elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced levels of antioxidant molecules like glutathione may result from immune system activation, subsequently leading to ketone production. The breakdown of proteins altered amino acid profiles, glycolysis, and TCA cycles may indicate muscle wasting, bacterial infection, and sepsis as ARDS progression. Conversely, increased levels of specific lipids, such as sphingolipids and ceramides, have been linked to inflammation, cell apoptosis, and cell membrane breakdown in ARDS. In addition, the kynurenine and arginine pathways play crucial roles in regulating T-cell activation during infection. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of these metabolic phenotypes is essential for tailoring treatment strategies and improving outcomes for patients with ARDS.

Figure 1.

Metabolic signatures differentiate COVID and non‐COVID ARDS. ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome. [Image created with a licensed version of BioRender.com.]

Until now, there have been few studies using the multi-omics approach to investigate ARDS specifically caused by either bacterial infection or sepsis. On the other hand, multiple studies began to combine different omic approaches for COVID. Overmyer et al. (26) used RNA-seq and high-resolution mass spectrometry on 128 blood samples from COVID-positive and COVID-negative patients with diverse disease severities and outcomes. Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics data were correlated with clinical outcomes in this study. They found groups of highly correlated molecules, including protein gelsolin, metabolite citrate, and plasmalogens as well as apolipoproteins, which provide pathophysiological insights into ARDS (26). These results indicate the dysregulation of platelet function, blood coagulation, acute phase response, and pathophysiology for the different COVID-19 phenotypes (26). Similarly, Lam et al. (33) investigated exosome-enriched plasma fractions of extracellular vesicles using lipidomics and proteomic analyses from patients at different temporal stages of COVID, including the presymptomatic, hyperinflammatory, resolution, and convalescent phases. They also found dysregulated raft lipid metabolism that underlies changes in extracellular vesicle lipid membrane anisotropy that alters the exosomal localization of presenilin-1 (PS-1) in the hyperinflammatory phase (33). Another study examined tissues from multiple organs, including the lung, kidney, liver, and heart, from COVID autopsy donors (34). The integrated computational analysis (Table 2) uncovered substantial remodeling in the lung epithelial, immune, and stromal compartments, with evidence of multiple paths of failed tissue regeneration, including defective alveolar type 2 differentiation and expansion of fibroblasts and putative TP63+ intrapulmonary basal-like progenitor cells (34).

Table 2.

Integrated omics studies on COVID-19

| Study | Key Dysregulated Pathways | Omics |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell atlases (34) | Transcriptional alterations in multiple cell types in COVID donor heart tissue and mapped cell types and genes implicated with disease severity based on COVID GWAS. Dysregulated surfactant and phospholipids metabolism in COVID. | Transcriptomics of multiple organs |

| Blood exosome (33) | Dysregulated raft lipid metabolism in exosomes alters the location of presenilin-1 in the hyperinflammatory phase. | Lipidomics and metabolomics |

| Blood (26) | 219 molecular features with high significance to COVID status and severity, many of which were involved in complement activation, dysregulated lipid transport, and neutrophil activation. Protein gelsolin and metabolite citrate or plasmalogens, apolipoproteins, offering pathophysiological insights. | Lipidomics, metabolomics, proteomics |

| COVID-19-induced ARDS (59) | COVID-related ARDS have elevated branched amino acids, urea cycle, phospholipid and fatty acids; bacteria-related ARDS have elevated tyrosine, methionine, benzoate, and alanine/aspartate, and histidine. ARDS-associated mitochondrial dysfunction as poor prognosis of acute kidney injury during ARDS. | Lipidomics, metabolomics, proteomics |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Using metabolomic approaches, we may achieve early detection of ARDS and even predict its development before clinical symptoms become apparent. In addition, certain metabolites may serve as prognostic markers, helping to predict the severity and outcomes of ARDS. On the other hand, there are several potential issues and challenges associated with this approach, such as detection limits, sample variability, sample variation, standardization and reproducibility, and even experimental design. One of the minor weaknesses in this review is that we sought data merely from PubMed database. We believe that future big data and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques will enable us to conquer these challenges with better and more accurate management of diseases.

In summary, with development of instrumental and analytical methods, such as machine learning and multi-omics integration, could not only advance our understanding of ARDS biology but also provide new insights into pathogenesis and potential therapeutics in the future.

GRANTS

This work was funded by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) Foundation YFEL141014 to X.J. This work was also funded by Grants from NIH (HL134828 and GM127596).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.-L.J. prepared figures; X.J. and H.-L.J. drafted manuscript; X.J. and H.-L.J. edited and revised manuscript; X.J. and H.-L.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Graphical abstract created with a licensed version of BioRender.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Singleton KD, Beckey VE, Wischmeyer PE. Glutamine prevents activation of NF-kappaB and stress kinase pathways, attenuates inflammatory cytokine release, and prevents acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) following sepsis. Shock 24: 583–589, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000185795.96964.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sharma NS, Lal CV, Li J-D, Lou XY, Viera L, Abdallah T, King RW, Sethi J, Kanagarajah P, Restrepo-Jaramillo R, Sales-Conniff A, Wei S, Jackson PL, Blalock JE, Gaggar A, Xu X. The neutrophil chemoattractant peptide proline-glycine-proline is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L653–L661, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sedhai YR, Yuan M, Ketcham SW, Co I, Claar DD, McSparron JI, Prescott HC, Sjoding MW. Validating measures of disease severity in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18: 1211–1218, 2021. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-772OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bos LDJ, Weda H, Wang Y, Knobel HH, Nijsen TME, Vink TJ, Zwinderman AH, Sterk PJ, Schultz MJ. Exhaled breath metabolomics as a noninvasive diagnostic tool for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J 44: 188–197, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00005614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schubert JK, Muller WP, Benzing A, Geiger K. Application of a new method for analysis of exhaled gas in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 24: 415–421, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s001340050589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hu S, McCartney MM, Arredondo J, Sankaran-Walters S, Borras E, Harper RW, Schivo M, Davis CE, Kenyon NJ, Dandekar S. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical exhaled breath condensate samples for metabolomic analysis. J Breath Res 16: 10.1088/1752-7163/ac3f24, 2021. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ac3f24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paris D, Palomba L, Albertini MC, Tramice A, Motta L, Giammattei E, Ambrosino P, Maniscalco M, Motta A. The biomarkers’ landscape of post-COVID-19 patients can suggest selective clinical interventions. Sci Rep 13: 22496, 2023. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-49601-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borras E, McCartney MM, Rojas DE, Hicks TL, Tran NK, Tham T, Juarez MM, Franzi L, Harper RW, Davis CE, Kenyon NJ. Oxylipin concentration shift in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. J Breath Res 17: 10.1088/1752-7163/acea3d, 2023. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/acea3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans CR, Karnovsky A, Kovach MA, Standiford TJ, Burant CF, Stringer KA. Untargeted LC-MS metabolomics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid differentiates acute respiratory distress syndrome from health. J Proteome Res 13: 640–649, 2014. doi: 10.1021/pr4007624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rai RK, Azim A, Sinha N, Sahoo JN, Singh C, Ahmed A, Saigal S, Baronia AK, Gupta D, Gurjar M, Poddar B, Singh RK. Metabolic profiling in human lung injuries by high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Metabolomics 9: 667–676, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0472-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Viswan A, Ghosh P, Gupta D, Azim A, Sinha N. Distinct metabolic endotype mirroring acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) subphenotype and its heterogeneous biology. Sci Rep 9: 2108, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viswan A, Singh C, Rai RK, Azim A, Sinha N, Baronia AK. Metabolomics based predictive biomarker model of ARDS: a systemic measure of clinical hypoxemia. PLoS One 12: e0187545, 2017. [Erratum in PLoS One 13: e0193474, 2018]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moolamalla STR, Balasubramanian R, Chauhan R, Priyakumar UD, Vinod PK. Host metabolic reprogramming in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systems biology approach. Microb Pathog 158: 105114, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Voiriot G, Dorgham K, Bachelot G, Fajac A, Morand-Joubert L, Parizot C, Gerotziafas G, Farabos D, Trugnan G, Eguether T, Blayau C, Djibre M, Elabbadi A, Gibelin A, Labbe V, Parrot A, Turpin M, Cadranel J, Gorochov G, Fartoukh M, Lamaziere A. Identification of bronchoalveolar and blood immune-inflammatory biomarker signature associated with poor 28-day outcome in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 12: 9502, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogers AJ, Contrepois K, Wu M, Zheng M, Peltz G, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Profiling of ARDS pulmonary edema fluid identifies a metabolically distinct subset. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 312: L703–L709, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00438.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barberis E, Amede E, Khoso S, Castello L, Sainaghi PP, Bellan M, Balbo PE, Patti G, Brustia D, Giordano M, Rolla R, Chiocchetti A, Romani G, Manfredi M, Vaschetto R. Metabolomics diagnosis of COVID-19 from exhaled breath condensate. Metabolites 11: 847, 2021. doi: 10.3390/metabo11120847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh C, Rai RK, Azim A, Sinha N, Ahmed A, Singh K, Kayastha AM, Baronia AK, Gurjar M, Poddar B, Singh RK. Metabolic profiling of human lung injury by 1H high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of blood serum. Metabolomics 11: 166–174, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0688-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Nin N, Jimenez-Clemente J, Horcajada JP, Arenas-Miras MDM, Gea J, Esteban A, Ruiz-Cabello J, Lorente JA. Metabolomic profile of ARDS by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with H1N1 influenza virus pneumonia. Shock 50: 504–510, 2018. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas T, Stefanoni D, Reisz JA, Nemkov T, Bertolone L, Francis RO, Hudson KE, Zimring JC, Hansen KC, Hod EA, Spitalnik SL, D'Alessandro A. COVID-19 infection alters kynurenine and fatty acid metabolism, correlating with IL-6 levels and renal status. JCI Insight 5: e140327, 2020. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shen B, Yi X, Sun Y, Bi X, Du J, Zhang C, , et al. Proteomic and metabolomic characterization of COVID-19 patient sera. Cell 182: 59–72.e15, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bruzzone C, Bizkarguenaga M, Gil-Redondo R, Diercks T, Arana E, Garcia de Vicuna A, Seco M, Bosch A, Palazon A, San Juan I, Lain A, Gil-Martinez J, Bernardo-Seisdedos G, Fernandez-Ramos D, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Embade N, Lu S, Mato JM, Millet O. SARS-CoV-2 infection dysregulates the metabolomic and lipidomic profiles of serum. iScience 23: 101645, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwarz B, Sharma L, Roberts L, Peng X, Bermejo S, Leighton I, Casanovas-Massana A, Minasyan M, Farhadian S, Ko AI; Yale IMPACT Team; Dela Cruz CS, Bosio CM. Cutting edge: severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans is defined by a shift in the serum lipidome, resulting in dysregulation of eicosanoid immune mediators. J Immunol 206: 329–334, 2021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin S, Yue X, Wu H, Han TL, Zhu J, Wang C, Lei M, Zhang M, Liu Q, Xu F. Explore potential plasma biomarkers of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) using GC-MS metabolomics analysis. Clin Biochem 66: 49–56, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu J, Pan T, Qi X, Tan R, Wang X, Liu Z, Tao Z, Qu H, Zhang Y, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang J, Liu J. Increased mortality of acute respiratory distress syndrome was associated with high levels of plasma phenylalanine. Respir Res 21: 99, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu D, Shu T, Yang X, Song JX, Zhang M, Yao C, Liu W, Huang M, Yu Y, Yang Q, Zhu T, Xu J, Mu J, Wang Y, Wang H, Tang T, Ren Y, Wu Y, Lin SH, Qiu Y, Zhang DY, Shang Y, Zhou X. Plasma metabolomic and lipidomic alterations associated with COVID-19. Natl Sci Rev 7: 1157–1168, 2020. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Overmyer KA, Shishkova E, Miller IJ, Balnis J, Bernstein MN, Peters-Clarke TM, Meyer JG, Quan Q, Muehlbauer LK, Trujillo EA, He Y, Chopra A, Chieng HC, Tiwari A, Judson MA, Paulson B, Brademan DR, Zhu Y, Serrano LR, Linke V, Drake LA, Adam AP, Schwartz BS, Singer HA, Swanson S, Mosher DF, Stewart R, Coon JJ, Jaitovich A. Large-scale multi-omic analysis of COVID-19 severity. Cell Syst 12: 23–40.e7, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu J, Zhou M, Luo P, Yin Z, Wang S, Liao T, Yang F, Wang Z, Yang D, Peng Y, Geng W, Li Y, Zhang H, Jin Y. Plasma metabolomic profiling of patients recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with pulmonary sequelae 3 months after discharge. Clin Infect Dis 73: 2228–2239, 2021. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kimhofer T, Lodge S, Whiley L, Gray N, Loo RL, Lawler NG, Nitschke P, Bong SH, Morrison DL, Begum S, Richards T, Yeap BB, Smith C, Smith KGC, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. Integrative modeling of quantitative plasma lipoprotein, metabolic, and amino acid data reveals a multiorgan pathological signature of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Proteome Res 19: 4442–4454, 2020. [Erratum in J Proteome Res 20: 3400, 2021]. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fraser DD, Slessarev M, Martin CM, Daley M, Patel MA, Miller MR, Patterson EK, O'Gorman DB, Gill SE, Wishart DS, Mandal R, Cepinskas G. Metabolomics profiling of critically ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 patients: identification of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Crit Care Explor 2: e0272, 2020. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Delafiori J, Navarro LC, Siciliano RF, de Melo GC, Busanello ENB, Nicolau JC, Sales GM, de Oliveira AN, Val FFA, de Oliveira DN, Eguti A, Dos Santos LA, Dalçóquio TF, Bertolin AJ, Abreu-Netto RL, Salsoso R, Baía-da-Silva D, Marcondes-Braga FG, Sampaio VS, Judice CC, Costa FTM, Durán N, Perroud MW, Sabino EC, Lacerda MVG, Reis LO, Fávaro WJ, Monteiro WM, Rocha AR, Catharino RR. Covid-19 automated diagnosis and risk assessment through metabolomics and machine learning. Anal Chem 93: 2471–2479, 2021. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sindelar M, Stancliffe E, Schwaiger-Haber M, Anbukumar DS, Adkins-Travis K, Goss CW, O'Halloran JA, Mudd PA, Liu WC, Albrecht RA, Garcia-Sastre A, Shriver LP, Patti GJ. Longitudinal metabolomics of human plasma reveals prognostic markers of COVID-19 disease severity. Cell Rep Med 2: 100369, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Snider JM, You JK, Wang X, Snider AJ, Hallmark B, Zec MM, Seeds MC, Sergeant S, Johnstone L, Wang Q, Sprissler R, Carr TF, Lutrick K, Parthasarathy S, Bime C, Zhang HH, Luberto C, Kew RR, Hannun YA, Guerra S, McCall CE, Yao G, Del Poeta M, Chilton FH. Group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 is associated with the pathobiology leading to COVID-19 mortality. J Clin Invest 131: e149236, 2021. doi: 10.1172/JCI149236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lam SM, Zhang C, Wang Z, Ni Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Huang X, Mo L, Li J, Lee B, Mei M, Huang L, Shi M, Xu Z, Meng FP, Cao WJ, Zhou MJ, Shi L, Chua GH, Li B, Cao J, Wang J, Bao S, Wang Y, Song JW, Zhang F, Wang FS, Shui G. A multi-omics investigation of the composition and function of extracellular vesicles along the temporal trajectory of COVID-19. Nat Metab 3: 909–922, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Yang Y, Segerstolpe A, , et al. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature 595: 107–113, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bos LD, Sterk PJ, Schultz MJ. Volatile metabolites of pathogens: a systematic review. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003311, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shin H-W, Umber BJ, Meinardi S, Leu S-Y, Zaldivar F, Blake DR, Cooper DM. Acetaldehyde and hexanaldehyde from cultured white cells. J Transl Med 7: 31, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schütte H, Lohmeyer J, Rosseau S, Ziegler S, Siebert C, Kielisch H, Pralle H, Grimminger F, Morr H, Seeger W. Bronchoalveolar and systemic cytokine profiles in patients with ARDS, severe pneumonia and cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Eur Respir J 9: 1858–1867, 1996. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09091858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Metwaly S, Cote A, Donnelly SJ, Banoei MM, Mourad AI, Winston BW. Evolution of ARDS biomarkers: will metabolomics be the answer? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L526–L534, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00074.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pacheco R, Gallart T, Lluis C, Franco R. Role of glutamate on T-cell mediated immunity. J Neuroimmunol 185: 9–19, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wannemacher RW Jr, Klainer AS, Dinterman RE, Beisel WR. The significance and mechanism of an increased serum phenylalanine-tyrosine ratio during infection. Am J Clin Nutr 29: 997–1006, 1976. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Newberne PM. Overnutrition on resistance of dogs to distemper virus. Fed Proc 25: 1701–1710, 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wannemacher RW Jr, Powanda MC, Pekarek RS, Beisel WR. Tissue amino acid flux after exposure of rats to Diplococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 4: 556–562, 1971. doi: 10.1128/iai.4.5.556-562.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nakamura K, Ienaga K, Yokozawa T, Fujitsuka N, Oura H. Production of methylguanidine from creatinine via creatol by active oxygen species: analyses of the catabolism in vitro. Nephron 58: 42–46, 1991. doi: 10.1159/000186376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kao SJ, Su CF, Liu DD, Chen HI. Endotoxin-induced acute lung injury and organ dysfunction are attenuated by pentobarbital anaesthesia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 480–487, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen HI, Kao SJ, Hsu YH. Pathophysiological mechanism of lung injury in patients with leptospirosis. Pathology 39: 339–344, 2007. doi: 10.1080/00313020701329740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marzocco S, Di Paola R, Genovese T, Sorrentino R, Britti D, Scollo G, Pinto A, Cuzzocrea S, Autore G. Methylguanidine reduces the development of non septic shock induced by zymosan in mice. Life Sci 75: 1417–1433, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Marzocco S, Di Paola R, Serraino I, Sorrentino R, Meli R, Mattaceraso G, Cuzzocrea S, Pinto A, Autore G. Effect of methylguanidine in carrageenan-induced acute inflammation in the rats. Eur J Pharmacol 484: 341–350, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497–506, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Caterino M, Gelzo M, Sol S, Fedele R, Annunziata A, Calabrese C, Fiorentino G, D'Abbraccio M, Dell'Isola C, Fusco FM, Parrella R, Fabbrocini G, Gentile I, Andolfo I, Capasso M, Costanzo M, Daniele A, Marchese E, Polito R, Russo R, Missero C, Ruoppolo M, Castaldo G. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism and pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19. Sci Rep 11: 2941, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roberts I, Wright Muelas M, Taylor JM, Davison AS, Xu Y, Grixti JM, Gotts N, Sorokin A, Goodacre R, Kell DB. Untargeted metabolomics of COVID-19 patient serum reveals potential prognostic markers of both severity and outcome. Metabolomics 18: 6, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11306-021-01859-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Julkunen H, Cichońska A, Slagboom PE, Würtz P; Nightingale Health UK Biobank Initiative. Metabolic biomarker profiling for identification of susceptibility to severe pneumonia and COVID-19 in the general population. eLife 10: e63033, 2021. doi: 10.7554/eLife.63033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Metwaly S, Cote A, Donnelly SJ, Banoei MM, Lee CH, Andonegui G, Yipp BG, Vogel HJ, Fiehn O, Winston BW. ARDS metabolic fingerprints: characterization, benchmarking, and potential mechanistic interpretation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 321: L79–L90, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00077.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gierok P, Harms M, Methling K, Hochgrafe F, Lalk M. Staphylococcus aureus infection reduces nutrition uptake and nucleotide biosynthesis in a human airway epithelial cell line. Metabolites 6: 41, 2016. doi: 10.3390/metabo6040041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McGarrity S, Anuforo O, Halldorsson H, Bergmann A, Halldorsson S, Palsson S, Henriksen HH, Johansson PI, Rolfsson O. Metabolic systems analysis of LPS induced endothelial dysfunction applied to sepsis patient stratification. Sci Rep 8: 6811, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Oliveira LB, Mwangi VI, Sartim MA, Delafiori J, Sales GM, de Oliveira AN, Busanello ENB, Val F, Xavier MS, Costa FT, Baia-da-Silva DC, Sampaio VS, de Lacerda MVG, Monteiro WM, Catharino RR, de Melo GC. Metabolomic profiling of plasma reveals differential disease severity markers in COVID-19 patients. Front Microbiol 13: 844283, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.844283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Calfee CS, Janz DR, Bernard GR, May AK, Kangelaris KN, Matthay MA, Ware LB. Distinct molecular phenotypes of direct vs indirect ARDS in single-center and multicenter studies. Chest 147: 1539–1548, 2015. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ceballos FC, Virseda-Berdices A, Resino S, Ryan P, Martinez-Gonzalez O, Perez-Garcia F, Martin-Vicente M, Brochado-Kith O, Blancas R, Bartolome-Sanchez S, Vidal-Alcantara EJ, Alboniga-Diez OE, Cuadros-Gonzalez J, Blanca-Lopez N, Martinez I, Martinez-Acitores IR, Barbas C, Fernandez-Rodriguez A, Jimenez-Sousa MA. Metabolic profiling at COVID-19 onset shows disease severity and sex-specific dysregulation. Front Immunol 13: 925558, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.925558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yeung AW, Terentis AC, King NJ, Thomas SR. Role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 129: 601–672, 2015. doi: 10.1042/CS20140392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Batra R, Whalen W, Alvarez-Mulett S, Gomez-Escobar LG, Hoffman KL, Simmons W, Harrington J, Chetnik K, Buyukozkan M, Benedetti E, Choi ME, Suhre K, Schenck E, Choi AMK, Schmidt F, Cho SJ, Krumsiek J. Multi-omic comparative analysis of COVID-19 and bacterial sepsis-induced ARDS. PLoS Pathog 18: e1010819, 2022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]