Abstract

Research using animals depends on the generation of offspring for use in experiments or for the maintenance of animal colonies. Although not considered by all, several different factors preceding and during pregnancy, as well as during lactation, can program various characteristics in the offspring. Here, we present the most common models of developmental programming of cardiovascular outcomes, important considerations for study design, and provide guidelines for producing and reporting rigorous and reproducible cardiovascular studies in offspring exposed to normal conditions or developmental insult. These guidelines provide considerations for the selection of the appropriate animal model and factors that should be reported to increase rigor and reproducibility while ensuring transparent reporting of methods and results.

Keywords: chronic disease, developmental insult, fetal growth restriction, offspring, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Developmental programming is the ability of various exposures in utero or during early postnatal development to induce changes in offspring’s physiology and epigenetics that predispose the exposed offspring to later health problems and increased risk of diseases including cardiovascular diseases. The first evidence of a link between in utero, postnatal, or early life growth and chronic disease came from cohort studies that followed groups of children as they aged (1–3). The concept of developmental programming of cardiovascular disease originated from the “Barker hypothesis,” also known as the fetal origins of adult disease hypothesis, which posits that chronic diseases in adulthood arise because of the intrauterine environment and fetal response to that environment (4). Further evidence supporting the Barker hypothesis came from translational research studies in the form of preclinical animal models, which will be highlighted in the next sections. The aim of this paper is to outline various animal models of developmental insults, highlighting the advantages, limitations, and considerations for each model. We also discuss the pregnancy-related factors that should be reported along with the offspring data, to ensure transparent reporting of methods and results, thus ensuring increased rigor and reproducibility.

Although this article focuses on the cardiovascular risks in the offspring, a companion paper focusing on maternal cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy is published in this issue, Collins et al. (5) “Guidelines for Assessing Maternal Cardiovascular Physiology During Pregnancy and Postpartum.”

MODELS OF DEVELOPMENTAL INSULTS

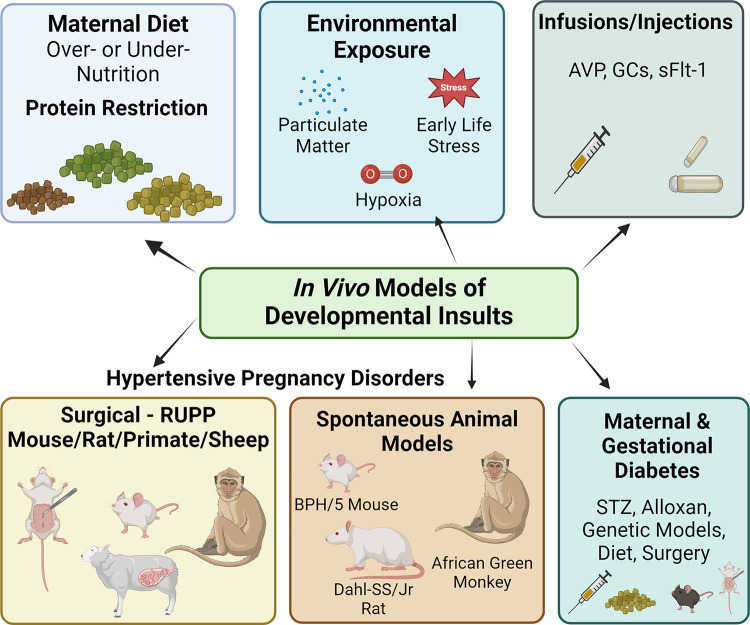

There are several models of developmental insults that program cardiovascular disorders in the resulting progeny. Developmental insults are selected based on the physiological exposures or clinical conditions of interest and the cardiovascular programming outcome that is being measured. Examples of developmental insults include under- and overnutrition, adverse pregnancy conditions, and environmental exposures (summarized in Fig. 1 and discussed in more detail in the upcoming sections).

Figure 1.

Different preclinical models of developmental insult used in the literature. Models include adverse pregnancy conditions (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes), maternal under- or overnutrition, and environmental exposures. AVP, arginine vasopressin; BPH/5, blood pressure high 5; GC, glucocorticoids; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure; STZ, streptozotocin. Created using a licensed version of BioRender.com.

MATERNAL AND GESTATIONAL UNDERNUTRITION

The first evidence that prenatal and perinatal undernutrition could have a long-term impact on human health came from the longitudinal follow-up of adults who were exposed to the Dutch Famine (“Hunger Winter”) of 1944–1945 during gestation or early life (1, 2). Animal models have now become a valuable resource for evaluating the underlying mechanisms because of their short lifespan and the ability to directly manipulate the time and type of nutrition consumed. Maternal caloric restriction is an example of maternal global undernutrition. The extent of calorie restriction used in these animal models varies from as little as 30 to 70% of the daily recommended intake (6, 7). One of the most consistent offspring phenotypes following moderate maternal caloric restriction during pregnancy is increased systolic blood pressure, an observation noted in several species, including mice, rats, sheep, and cows (6, 8–10). In addition to raised blood pressure, offspring exposed to maternal caloric restriction showed signs of vascular dysfunction and fibrosis and developed cardiomegaly associated with increased cardiomyocyte size (6, 9). Although fetal growth restriction (FGR) is a typical phenotype at birth (11, 12), not all studies reported a difference in birth weight, suggesting that developmental programming of adult outcomes may not always accompany the presence of FGR despite the presence of increased systolic blood pressure in the offspring (13).

Maternal protein restriction is one of the most widely studied models of maternal undernutrition. Offspring of protein-restricted dams have been shown to have high blood pressure in adulthood (14–17); however, not all models of maternal protein restriction show evidence of hypertension or an adverse cardiovascular phenotype (18). The differences between offspring outcomes have been linked to the dietary composition of the maternal diet rather than the protein restriction per se. Langley-Evans (19) in 2001 reviewed this in detail and compared the dietary composition of two low-protein diets with differing offspring cardiovascular outcomes, and the differences were attributed to differences in fat and carbohydrate composition of the maternal diet despite a similar degree of nutrient restriction. Importantly, severity of the maternal nutritional intake can also alter offspring outcomes highlighting the importance of consideration of the severity of nutritional deficient in addition to dietary composition of the maternal diet in these models (13). In addition to changes in blood pressure, maternal protein restriction in rodents is shown to lead to other offspring phenotypes, including accelerated atherosclerotic lesion progression, hypercholesterolemia, accelerated growth of the heart, delayed formation of the coronary artery, cardiomyocyte cell loss, and cardiac dysfunction coupled with attenuated β-adrenergic responsiveness as a consequence of both impaired adrenergic and insulin signaling (16, 20–23).

MATERNAL OBESITY OR MATERNAL OVERNUTRITION

Nearly one-third of adults in developed nations are obese, and the proportion of people with obesity continues to increase each year (24). Women with obesity are increasingly recognized to have offspring with greater cardiovascular risk throughout life (25, 26). The modern Western diet typically consumed in developed countries is higher in fat than the recommended guidelines (27), therefore modeling maternal obesity using high-fat diet is generally clinically relevant. However, the clinical relevance of models using high-fat diet-induced obesity to evaluate cardiovascular programming in the offspring is limited by variations in micronutrient and macronutrient consumption as well as varying levels of physical activity in obese humans, all of which are known to impact maternal health and offspring cardiovascular outcomes. Most often, models of maternal obesity use maternal high-fat diets to induce obesity or as a surrogate marker of maternal obesity. In most animal models, increased maternal weight is used as a marker of obesity. However, most models do not specifically measure maternal obesity-associated complications, such as increased adipose deposition and insulin resistance (28–33). Models using a high-fat diet to induce maternal obesity provide a moderately high-fat diet for weeks to months before conception and continue the high-fat diet through pregnancy and lactation. Some models cross foster the offspring to isolate the impact of the high-fat diet on only pregnancy exposure or only lactation exposure, or the combination of both (34, 35). The models of parental obesity evaluate cardiovascular outcomes at various ages from fetal life through adulthood. Most studies include evaluation of blood pressure, cardiac and/or vascular histology, and protein expression, and some studies include mRNA or microRNA expression (32), function with oxygen uptake (28), pressure myography (29–31, 35), or echocardiography (28–31). A wide variety of species have been evaluated, including various strains of mice and rats, as well as sheep (33) and nonhuman primates (32). Regardless of species-specific differences, the overall impact of a maternal high-fat diet-induced obesity most often results in cardiovascular dysfunction from the offspring’s fetal life through adulthood. Clinically, the endpoints studied in these animal models are relevant to human physiological outcomes. Recommendations for future research on the impact of maternal obesity include the evaluation of parental fat mass and body weight and potential comorbid conditions, such as insulin resistance. Furthermore, detailed reporting of dietary composition will aid in reproducibility of results.

Genetic studies showed that variants near the melanocortin 4 receptor (Mc4r) are associated with measures of obesity (e.g., body weight and fat mass) (36). Mice and rats heterozygous for Mc4r or knockout expression have been used to study central regulation of obesity. In the area of programming of obesity in the offspring, one study mated Mc4r heterozygous female and Mc4r heterozygous male mice fed an obesogenic or control diet before mating, during pregnancy, and lactation, and demonstrated that Mc4r knockout offspring had higher body and adipose tissue weights compared with wild-type and heterozygous offspring (37). Moreover, another study demonstrated that a functional Mc4r gene in the hypothalamic periventricular nucleus is critical for early life programming of hypertension in the offspring (38). Much of the work in the rat has been done on characterizing the pregnant female rat with Mc4r deficiency (39) whereas, not much has been done on characterizing the offspring. Deficiency of Mc4r is associated with reduced uteroplacental perfusion pressure (RUPP)-induced hypertension in pregnancy (40). Thus, more studies are required to characterize the contribution of genetic-induced obesity on the developmental programming of cardiovascular disease in the offspring.

ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURES

Fetal Exposure to Exogenous Corticosteroids

Circulating corticosteroids increase during fetal development and contribute to the maturation of fetal tissues including the lung, liver, and the kidney (41). Preclinical studies indicate that fetal exposure to excess corticosteroids is associated with increased risk of chronic disease in the offspring (42–44). Chronic maternal hypercortisolemia in late gestation mimics the increase in corticosteroids that are elevated in response to maternal stress (45, 46). Use of a clinically relevant dose of betamethasone in late gestation mimics the clinically relevant condition of corticosteroids as an interventional therapy for lung maturation in pregnancies at risk for preterm birth (47, 48). Exogenous corticosteroids that are used clinically in the treatment of preterm birth, dexamethasone or betamethasone, are poor substrates for 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2 (11β-HSD-2) activity (49). Placental 11β-HSD-2 is an enzyme that protects the fetus by converting cortisol into a less active form, cortisone. Rat (50, 51) and sheep (45, 46, 52) are common species used for the study of adverse effects of late gestational exogenous corticosteroid exposure on offspring chronic health. Common outcomes using these models of fetal exposure to exogenous corticosteroids include altered fetal cardiac function at birth (46), left ventricular hypertrophy in adulthood (53), a reduction in nephron number (54, 55), renal injury (56), impaired baroreflex sensitivity (57), a significant increase in arterial pressure regardless of species (51, 52, 56, 58), and changes in adaptive cognitive and behavioral function (49). Fetal exposure to exogenous corticosteroids is also associated with sex-specific effects on blood pressure (59) in addition to cardiac (60) and renal function (61). Preclinical studies suggest that the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) (57) and the renal sympathetic nerves (62) contribute to increased blood pressure in offspring exposed to late-gestational exogenous corticosteroids. Despite these findings in preclinical models, a single course of antenatal corticosteroids before preterm birth remains an important antenatal therapy to improve newborn maturation outcomes (63). However, additional studies are warranted to understand the mechanisms that link in utero exposure to excess exogenous corticosteroids to long-term risk for chronic disease in the offspring.

IN UTERO PARTICULATE MATTER PRIMING OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

The role of in utero exposure to particles from the environment has become increasingly studied, with significant evidence emerging on the impacts to human health, particularly later in life. Particulate matter (PM), a heterogeneous mixture of tiny solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in the air, has been shown to be involved in the progression of cardiopulmonary disease and the development of cognitive abnormalities (64–67). Particulate matter is classified based on particle size, with PM2.5 (particles with a diameter of 2.5 μm or smaller) and PM10 (particles with a diameter of 10 μm or smaller) being of primary concern. Exposure to PM2.5 is especially detrimental as these particles can penetrate deep into the respiratory system and even enter the bloodstream (68, 69). Sources of particulate matter include vehicle emissions, industrial processes, construction activities, and natural sources such as dust and pollen. The proximity to these sources and individual lifestyle choices plays a crucial role in determining the adverse effects of PM exposure on health.

The developing fetus is particularly vulnerable to exposure to environmental constituents, including PM. During pregnancy, the placenta serves as a barrier to protect the fetus from harmful substances, but it does not completely prevent the passage of all pollutants. PM2.5 particles have been found to cross the placental barrier (70), this early exposure could influence the programming of various physiological systems including the heart, brain, and lungs, leading to long-term health consequences. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how in utero particulate matter exposure can contribute to adult disease. Oxidative stress and inflammation are key pathways through which PM2.5 particles exert their harmful effects in mice (64, 71). These particles contain toxic components such as heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can induce oxidative stress in developing tissues. In addition, PM-induced inflammation can disrupt normal cellular processes, contributing to the development of diseases like cardiovascular disorders, respiratory ailments, and even metabolic conditions in adult mice (64, 72).

Epidemiological studies have suggested a correlation between in utero particulate matter exposure and various adult diseases. Respiratory disorders such as asthma and decreased lung function, cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and even obesity have been linked to prenatal exposure to PM2.5 in mice (65, 66). Furthermore, emerging evidence in humans indicates potential connections between in utero PM exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders as well as adverse reproductive outcomes (73, 74).

Gaps in the reporting of methods in these studies are inherent in the study of PM, with PM levels changing all the time based on environmental conditions and the location of the study. In addition, studies have not normalized the level of PM exposure, time course, or time of day when exposure occurs. These should be controlled to accurately compare studies on the developmental programming potential of PM on cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurocognitive health. Understanding the link between in utero PM exposure and adult disease has significant implications for public health policies and practices. Pregnant women, especially those living in areas with high levels of air pollution, should receive information and guidance to reduce their exposure. Urban planning and transportation policies aimed at reducing vehicular emissions and improving air quality can contribute to mitigating the risks associated with particulate matter exposure.

In utero PM exposure has emerged as a critical environmental factor that can influence the trajectory of adult health outcomes. The complex interplay of oxidative stress, inflammation, and disrupted developmental programming underscores the importance of addressing this issue on both individual and societal levels. As our understanding of the mechanisms and consequences of in utero PM exposure deepens, efforts to mitigate its impact can help ensure healthier lives for generations to come.

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPOSURE AND EARLY LIFE STRESS

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur during the first decade of life and can extend through adolescence (75, 76). ACEs are marked by emotional distress, violence, abuse, or neglect that are experienced in the household or the community (77). Social determinants of health (SDOH) refer to the environmental and social conditions where people are born, live, and age that affect quality-of-life outcomes and risks. SDOH, in many cases, can have a greater influence on health than either genetic factors or access to healthcare services (78). SDOH and ACE are interconnected, causing toxic stress (79, 80). Increased glucocorticoid levels associated with toxic stress negatively impact tissue development resulting in permanent structural and functional alterations of the brain and other organs. Animal models of ACE are based on the disruption of the Stress Hypo-Responsive Period, corresponding to postnatal days 1–10 in mice and postnatal days 3–14 in rats (81). Elevated glucocorticoids sensitize the neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and other homeostatic systems, resulting in greater risk for chronic disease and exacerbated vascular and metabolic responses to secondary stressors experienced later in life (82).

A preclinical approach for generating sustained fear, anxiety, and stress in the offspring is to introduce persistent alterations in maternal-offspring inputs (83, 84). Maternal separation is a well-established rodent model of early life stress in which neonates are separated from their mothers for 3 h/day from postnatal days 2 to 14 and weaned at postnatal day 21 (85–88). Maternal separation and early weaning in mice have been used as a unique paradigm to model childhood neglect (89–92). Beyond providing nutrition and safety to the nest, maternal-derived sensory stimulation influences appropriate maturation, levels of gene expression patterns, and stress-related neuronal circuits that are crucial for normal development (83, 93). Sensory stimulation of maternal licking and grooming affect the corticotropin-releasing hormone-adrenocorticotropic hormone (CRH-ACTH) expression, an important modulator of basal activity levels of enzymes and hormones necessary for normal growth (84). This input also seems to influence neural stem cell levels and neuronal and glial development (94–96). Moreover, maternal separation serves as a unique model to study the effects of stress exposure during development, as the first postnatal week in rodents is comparable with the third trimester of gestational life in humans. Thus, modeling late gestational exposure to excess glucocorticoids by inducing chronic stress in the offspring can offer insights into the mechanisms by which early exposure to stressful stimuli has a lifelong influence on cardiovascular physiological function.

HYPOXIA

Another potential environmental exposure that could program cardiovascular risks in the offspring is hypoxia, a state of reduced oxygen availability. Different experimental hypoxia models are used based on the clinical condition being modeled. For example, intermittent hypoxia is used to model sleep apnea whereas chronic hypoxia exposure is used to model chronic intrauterine hypoxia that may occur because of reduced uteroplacental blood flow in preeclampsia. In these studies, the level of oxygen, length of exposure, and timing of exposure vary. In addition, the time-point for the measurement of cardiovascular parameters also varies significantly. Despite these limitations and considerations, there is evidence that gestational exposure to hypoxia (11% or 13% O2) during gestation is associated with increased susceptibility and injury from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion insult in adult offspring (97, 98). Interestingly, males and females are both susceptible but have different mechanistic pathways (99, 100). With the use of guinea pigs exposed to chronic hypoxia, changes in mitochondrial acetylation were observed in the hearts of term offspring (101), with larger changes in males than females. Studies using intermittent hypoxia exposure during gestation, report smaller pups with catch-up growth and increased blood pressure at prepubertal age (102). Studies have also been conducted in sheep exposed to chronic hypoxia (103), with reduced fetal weights and FGR in the offspring, and preeclampsia-like features in the ewes. To study the effects of chronic hypoxia on fetal growth and the developing cardiovascular system independent of maternal and placental effects, the chick embryo can be used (104). Importantly, models of prenatal hypoxia in rat and sheep are being used to investigate therapeutic strategies that target oxidative stress to mitigate impaired cardiovascular function in offspring exposed to fetal hypoxemia (105, 106).

ADVERSE PREGNANCY CONDITIONS

Models of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Hypertension during pregnancy poses a significant health concern for both the pregnant women and the exposed offspring and is one of the leading causes of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality worldwide (107). Preeclampsia, one of the common hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, poses a significant future risk for the development of cardiovascular disease in diagnosed mothers and their offspring (108–113). During early pregnancy, maternal uterine spiral artery remodeling is essential to deliver adequate blood flow to the developing fetoplacental unit (114). When perfusion is inadequate, placental ischemia results. To model this, the reduced uteroplacental perfusion pressure (RUPP) model was developed in the rat (115). At gestational day 14, silver clips are placed around the aorta proximal to the iliac bifurcation and around the right and left uterine branch of the ovarian artery to prevent compensatory blood flow (116). Alternatively, clips are placed on both uterine branches of the ovarian artery and both branches of the proximal uterine arteries in the selective RUPP model (117). Blood flow to the gravid uterus is reduced by 40% (116), along with late gestational hypertension, proteinuria, decreased litter size, and FGR (115). Both the RUPP model and human preeclampsia are characterized by elevated circulating factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) (118), TNF-α (119), and autoantibodies against the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1-AA) (120). Placental hypoxia promoted by ligation of arterial blood flow to the conceptus has been shown in the RUPP model to have lasting cardiometabolic alterations in the offspring. Male FGR offspring exhibit hypertension in young adulthood (121) with delayed hypertension development occurring in females at 12 mo of age because of renal sympathetic nerve activation (122) that is associated with an increase in adiposity and early reproductive senescence (123). Offspring of RUPP dams have dysregulated glucose homeostasis with both adult males and females affected (123, 124). The adult males exhibited decreased insulin, whereas the female FGR did not (122, 123). Glucagon is only lower in male and female offspring in the peripubertal stage but not in adulthood. Ghrelin, which is decreased in both male and female peripubertal offspring from the RUPP, only persists into adulthood in the female (124). Although numerous studies report cardiovascular outcomes in offspring using the RUPP model in the rat (121, 122, 124), studies using the RUPP model in the mouse are limited. In the mouse RUPP model (56), central mechanisms for cardiometabolic dysregulation may stem from RUPP mouse neonates having reduced brain microvascular perfusion and a significant decrease in vascular reactivity upon stimulation, with females more affected than males (125).

Although the RUPP model recapitulates important key features of preeclampsia in late gestation, some limitations exist. Mechanical constriction of blood vessels limits options for treatment interventions. Moreover, there is an inability to investigate prepregnancy risk factors or biomarkers of preeclampsia before disease presentation. It is also not possible to study early gestational events because the surgeries are induced late in gestation [gestational days 14 in the rat (115) and 13 in the mouse (126)], whereas spontaneous models of preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension (superimposed preeclampsia) exist that allow for investigation into early events.

Superimposed preeclampsia is defined as preexisting hypertension before pregnancy that is complicated with preeclampsia symptoms during pregnancy (127). The Dahl salt-sensitive rat (Dahl-SS/Jr) was described as a spontaneous model of superimposed preeclampsia (128). Pregnant Dahl-SS/Jr rats have exacerbation of preconception hypertension, pregnancy-specific proteinuria, FGR, and placentopathies similarly seen in preeclampsia and FGR. Because of the spontaneous nature of this rodent model of preeclampsia and the heritability of hypertension, in utero programming can be investigated in Dahl-SS/Jr offspring. Sildenafil citrate was not able to prevent hypertension in offspring given angiotensin II although it reduced the blood pressure response to salt in Dahl-SS/Jr male, but not in female, offspring (129). These types of studies can also be done in a transgenic rat model of human preeclampsia that was created by breeding a female containing the human transgene for angiotensinogen with a male harboring the human renin transgene (130). This model also mimics chronic hypertension superimposed on preeclampsia (131). Studies to date in offspring using this model are limited; however, in offspring expressing the human angiotensinogen and renin gene, birth weight is reduced, and blood pressure is elevated at 6 mo of age (132). Cognitive deficit was also evident, demonstrating that this is another potential model for exploring mechanisms that contribute to adverse outcomes in offspring in a model that mimics hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

The blood pressure high (BPH)/5 mouse is a genetic model with mild hypertension that exhibits obesity and cardiovascular disease before pregnancy and thus is advantageous for investigating cardiometabolic risk throughout the lifecycle. Unlike existing rodent models of preeclampsia that involve surgical or pharmacological induction of the maternal syndrome at mid to late gestation, the BPH/5 mouse develops excessive gestational weight gain and a preeclampsia-like phenotype spontaneously (133, 134). BPH/5 offspring demonstrate sexually dimorphic cardiometabolic risk. Both female and male BPH/5 mice have cardiovascular disease, i.e., hypertension and cardiomegaly (134, 135). BPH/5 females have additional preconception cardiometabolic comorbidities including obesity and hyperphagia (134). BPH/5 males do not demonstrate the obesogenic phenotype as food intake and adult body mass are similar compared with C57 controls. Importantly, using this spontaneous model, a gestational intervention such as reducing maternal gestational weight gain by pair feeding hyperphagic BPH/5 pregnant mice to match food intake in gestational match controls, reduces adiposity and blood pressure in the offspring (136). The concept of reversing in utero programing of offspring has immense promise for stopping the transgenerational lifecycle of disease.

The African Green Monkey has been described as another model of spontaneous preeclampsia. A seminal study used selective breeding of African green monkeys and noted that if one parent has hypertension, offspring are more likely to develop elevated blood pressure as early as 1 yr of age (137). Although this nonhuman primate is promising, access to African Green Monkeys is limited and studies are very costly.

The arginine vasopressin (AVP) pathway has recently come forward as a candidate for investigating preeclampsia. AVP-dependent hypertension is characterized by low circulating renin-angiotensin system activity, which is also seen in women with preeclampsia (138). Chronic AVP infusion during pregnancy (gestational days 0.5 until 16.5) is sufficient to induce the preeclampsia-phenotype in normal healthy C57 female mice. Systolic blood pressure and urinary protein excretion are increased at gestational days 15.0/16.0 and 17.0, respectively. This is associated with robust renal glomerular endotheliosis, a pathognomonic finding in preeclampsia (138). There is also evidence for FGR in AVP-infused pregnancies. Fetal mass measured at late gestation (embryonic day 18.5) is significantly lower after chronic AVP infusion (138). This model supports the novel concept that central mediators of hypertension are activated in early pregnancy. Chronic AVP infusion during pregnancy is associated with altered offspring brain development and gene expression (139). This results in anxiety-like behavior in adult male offspring and impaired learning in adult female offspring.

Some women who develop preeclampsia have no preexisting comorbidities. Placental ischemia and the release of antiangiogenic factors, such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), are thought to provoke the clinical presentation of preeclampsia: new onset hypertension and multiorgan dysfunction. To mimic this, the sFlt1 infusion model was developed. Injection of adenovirus carrying sFlt1 at gestational day 7.5 results in late gestational hypertension and FGR in CD-1 mice (140). Many studies have evaluated the impact of scavenging vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by the soluble receptor, sFlt1, in preeclampsia. To support a pregnancy-specific in utero programming, the offspring born to sFlt1 infused dams have impaired glucose homeostasis (141) and sex-specific alterations in offspring brain development (142) and blood pressure (143).

DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAMMING OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE BY GESTATIONAL DIABETES

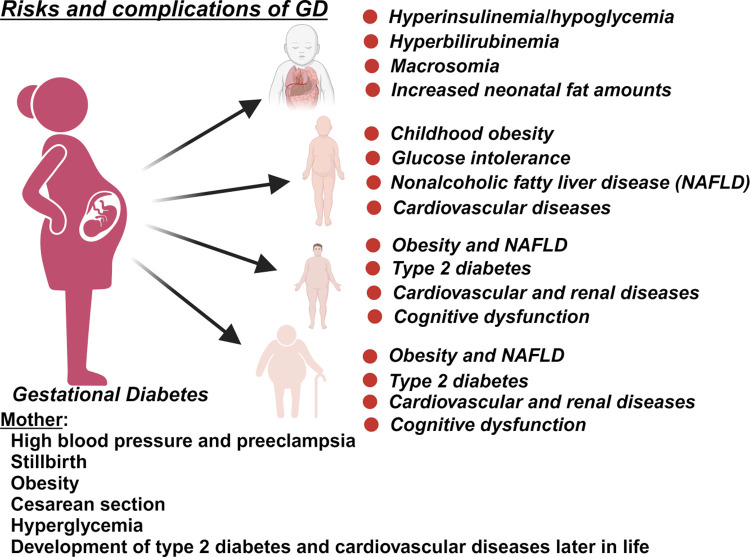

The quality of the fetal environment during pregnancy is crucial in programming cardiovascular health and diseases later in life. Gestational diabetes (GD) is characterized by a transitory form of diabetes induced by insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction during pregnancy. Women diagnosed with GD have an elevated risk, almost 10 times higher, of developing type 2 diabetes later in life (144). GD can affect ∼9 to 25% of pregnancies worldwide (145), and poses a substantial medical challenge, with increased risk of maternal and neonatal morbidity. Pregnant individuals can be affected by pregestational diabetes (individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes before pregnancy) or gestational diabetes, generally diagnosed after the second or third trimester (146). In humans, maternal hormonal and metabolic changes occur during pregnancy to support normal fetal growth and development. These hormonal changes include increased production and release of prolactin and placental lactogen leading to decreased maternal insulin sensitivity to ensure an adequate amount of glucose crosses the placenta to nourish the developing fetus (147, 148). To meet increased energy demands during pregnancy, maternal glucose production is enhanced through gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis resulting in increased energy storage. Besides glucose, late pregnancy is also characterized by elevated free fatty acids (FFA) in the bloodstream to serve as an additional energy source for the mother, but also contribute to the rise in insulin resistance during pregnancy (149, 150). Obese pregnant women have an elevated risk of developing complications during pregnancy, including GD (151–153). In addition, women diagnosed with GD are more likely to develop hypertension (154, 155) and preeclampsia during pregnancy, as well as cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes later in life (Fig. 2). Infants born to mothers with GD are at an increased risk of being born large-for-gestational age, and macrosomic (156). This heightened birth weight raises the likelihood of delivery complications, including the risk of shoulder dystocia (156). Hyperglycemia during pregnancy is also associated with increased blood pressure in the offspring in later life (157).

Figure 2.

Risk and complications of gestational diabetes (GD) in exposed mothers and offspring. Diabetes during pregnancy poses risks for both the mother and the exposed offspring. Risks can manifest during the index pregnancy, later life for mother, and all stages of development for the offspring. Created using a licensed version of BioRender.com.

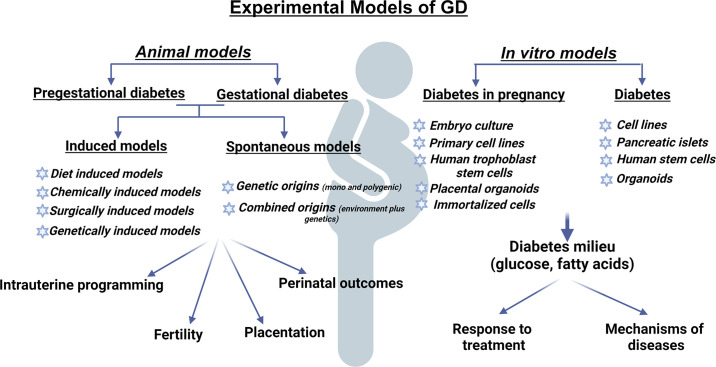

Experimental models of diabetes during pregnancy play a crucial role in unraveling the pathophysiological mechanisms that may lead to the development of effective treatment strategies. Experimental models also offer valuable insights on how to improve perinatal development and prevent FGR, macrosomia, respiratory problems, and type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases that develop early or later in life (Fig. 2). However, GD does not stem from a single environmental or genetic factor; rather, it arises from a complex interplay of various risk factors including weight, ethnicity, genetics, and family history that all play a role in determining the likelihood of developing GD. The complexity of GD and its related complications pose significant challenges when attempting to create animal models that precisely replicate the human’s clinical features (Fig. 3). To overcome these challenges, researchers must carefully select an appropriate animal model that aligns with clinical aspects relevant to their study goals. In vitro models of diabetes and diabetes in pregnancy (Fig. 3) are an essential component of biological research that provides a way to study the response of human or animals in cell culture with relative low cost, enabling reliable and efficient drug discovery studies. However, the major drawback is their failure to capture the inherent complexity of organ system.

Figure 3.

Preclinical models of diabetes during pregnancy. Experimental models of diabetes-induced programming of cardiovascular diseases range from in vitro to in vivo models. Both pregestational and gestational diabetes can be modeled in vivo based on the timing of interventions that produce diabetes-like conditions. GD, gestational diabetes. Created using a licensed version of BioRender.com.

Multiple preclinical models are used to study maternal diabetes and GD as described in Table 1. Administration of streptozotocin (STZ) during pregnancy is a commonly used approach to mimic GD and study the effects of gestational exposure to hyperglycemia on cardiovascular function in the offspring (167, 168). In this model, offspring develop an increase in blood pressure, baroreflex dysfunction, and cardiac hypertrophy (167, 168). Administration of STZ before pregnancy in the mouse can be used to study the effect of maternal diabetes mellitus on cardiovascular health in the offspring. In this model, maternal diabetes induces congenital heart defects (176), a programming event that is reversed by maternal treatment with a synthetic form of tetrahydrobiopterin (177). This study highlights the potential for investigation into potential therapeutic approaches during gestation that alleviate the adverse programming effects on offspring cardiovascular health. In vitro models of diabetes and diabetes in pregnancy (Fig. 3) are also an essential component of biological research that provide a way to study the response of cells from human or animals with relative low cost, enabling reliable and efficient drug discovery studies. However, the major drawback is their failure to capture the inherent complexity of the organ system. Ultimately, by adopting a well-designed approach and animal model, researchers can enhance the translatability of their findings to the human condition and pave the way for more effective interventions and treatments.

Table 1.

Considerations for animal models of developmental programming

| Animal Model | Methods | Duration | Advantages and Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Models of maternal undernutrition

| ||||

| Maternal global undernutrition | Reduced caloric intake | Differing time periods | Pros:

|

(6, 7, 9, 13, 19, 23) |

| Maternal protein restriction | Reduced protein intake | Differing time periods | Pros:

|

(12, 14) |

| Models of obesity and maternal overnutrition | ||||

| High-fat diet | Maternal or paternal high-fat diet | Before and during pregnancy During pregnancy alone During lactation |

Pros:

|

(35, 158, 159) |

| Mc4r (mouse, rat, human) | Genetic knockout/knockdown | Throughout life span | Pros

|

(36, 37) |

| Environmental exposures | ||||

| Fetal corticosteroid exposure | ||||

| Corticosteroid administration | Corticosteroid | During pregnancy Late pregnancy |

Pros:

|

(45, 50) |

| In utero particulate matter exposure | ||||

| Particulate matter exposure (rodents, humans) | Inhalation studies (rodents) Natural exposures (humans) |

Varies | Pros:

|

(64, 65, 67, 68) |

| Hypoxia | ||||

| Hypoxia (rat, guinea pigs, sheep, chick embryo) | Hypoxic chamber (chronic or intermittent hypoxia) |

During gestation | Pros:

|

(101–103, 160) |

| Models of early life stress | ||||

| Maternal separation (rats, mice) | Periods of separation from moms after birth | Postnatal days 2–14 for varying lengths of time depending on paradigm | Pros:

|

(85, 87, 90) |

| Adverse pregnancy conditions | ||||

| Models of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | ||||

| Reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP, rat and mouse) | Surgical intervention | Midgestation induction | Pros:

|

(31, 98, 117, 121, 124, 125) |

| Heat-induced IUGR (sheep) | Exposure to high ambient temperature | Day 40 of gestation to day 115 | Pros:

|

(161) |

| BPH/5 (mouse), Dahl-SS (rat) angiotensin/renin transgenic rat |

Spontaneous | Prepregnancy/throughout life | Pros:

|

(128, 129, 133, 135, 162, 163) |

| African green monkey (NHP) | Spontaneous | Prepregnancy | Pros:

|

(137) |

| AVP (mouse) | Infusion before and throughout (AVP) gestation | Pre- and during pregnancy | Pros:

|

(138, 139) |

| sFlt-1 (mouse) | Infusion on day 8 gestation | During pregnancy | Pros:

|

(142, 143) |

| Models of maternal and gestational diabetes | ||||

| Surgical (rats, sheep) | Total or partial pancreatectomy | Variable | Pros:

|

(164–166) |

| Chemical (rats, mice, rabbits, sheep) | Streptozotocin | Before or during pregnancy | Pros:

|

(165, 167–175) |

| Drug (rats, mice, rabbits, sheep, swine) | Alloxan | Before or during pregnancy | Pros:

|

(176–184) |

| Diet (mice, rats, ewes, dogs, sheep) | High-fat diet | Before pregnancy | Pros:

|

(35, 158, 159, 185–190) |

| Drug (rat) | 24-h infusion of glucose into blood supply of left uterine horn at day 19 gestation | Gestational day 19 | Pros:

|

(191) |

| Genetic: mice (NOD, Akita, db/db), rats (BB, GK) | Genetic manipulation (gene knockouts, transgenic overexpression) | - | Pros:

|

(192–201) |

AVP, arginine vassopressin; BB, biobreeding rat; BPH/5, blood pressure high 5; FGR, fetal growth restriction; GD, gestational diabetes; GK, Goto Kakizaki; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; Mc4r, melanocortin 4 receptor; NHP, nonhuman primate; NOD, nonobese diabetic mouse.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RIGOR AND TRANSPARENCY IN DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAMMING RESEARCH

Considerations for Experiential Design and Biological Variables

Consideration of relevant biological variables is critical to ensure rigor in scientific research. Biological sex, age, weight, and underlying health conditions are examples of critical factors required for consideration. However, to ensure rigor in the field of perinatal research, multiple biological variables must be accounted for because of their inherent impact on developmental programming of offspring growth and chronic health. Maternal variables including parity can alter adiposity in the offspring (202). Advanced maternal age is associated with enhanced uterine artery myogenic responses (203) and reductions in litter size and fetal weight (204). In addition, advanced maternal age is associated with sex-specific effects on vascular dysfunction (205), blood pressure (206), survival, and mortality in the offspring (207). It is well established that maternal diets high in fat (208), and sucrose (209), or low in protein (14, 210) heighten cardiovascular risk in the offspring. However, a maternal diet high in sodium (211) or a change in maternal dietary protein source, wheat gluten versus casein (212) can also alter offspring blood pressure. Maternal exposure to a broad-spectrum oral antibiotic altering the maternal microbiome is sufficient to alter neurobehavioral outcomes in the offspring (213). Cage enrichment during gestation improves reproductive performance including litter size and pup survival (214). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that subtle differences in maternal parity, age, diet, and husbandry can have profound effects on offspring growth, health and behavior (213). During lactation, growth and development of rat pups is dependent on litter size (215). Culling of rodent litters early in the postnatal period has become a standard practice in the field of developmental origins of adult health and disease (216). Maintenance of the sex ratio is warranted and culling to eight pups per litter allows equal access to nutrition reducing variability in the growth and development of the pups (216). Yet, culling to small litter sizes, three or four or less, is associated with accelerated weight gain, hyperphagia, and alterations in the adult metabolic phenotype (217) suggesting that standard practices are necessary for ensuring rigor and reproducibility in experimental design and reporting. Another critical source of biological variability is the use of more than one pup per litter per study outcome. The use of only one randomly selected pup per sex per litter is recommended to ensure study of a “programming” event versus a “litter specific” event (218). To conclude, standardized experimental practices in addition to reporting of biological variables are needed to ensure rigor in reported outcomes in the perinatal field of research. In addition, regarding all models of developmental insult, the time frame for cardiovascular measurements in the offspring should be taken into consideration to ensure accurate and meaningful results. Furthermore, to better understand potential sex differences in the outcomes of offspring, it is essential to include both male and female subjects in the research for a more comprehensive analysis of any divergent effect based on sex (219).

CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

-

1)

Source of animals: commercial vendor and barrier versus in-house breeding (e.g., microbiome and pathogen exposure differences between facilities).

-

2)

Animal strain: different strains have different physiological responses and different genetic backgrounds (e.g., C57BL/6J vs. 6N).

-

3)

Animal breeding history: generational considerations (e.g., genetic drift).

-

4)

Sex as a biological variable: inclusion of male and female offspring with proper power analysis to ensure statistical significance to determine sex differences, inclusion of both sexes versus sex difference design. Include both male and female offspring OR provide strong scientific justification why only one sex is being used. If sex difference in cardiovascular outcome is being considered, ensure that the study is sufficiently powered to determine a difference [see Sex as a Biological Variable Guidelines (219)].

-

5)

Maternal and paternal characteristics (age at breeding, prior pregnancies).

-

6)

Dietary considerations (sources of protein, fats, and carbohydrates, dietary exposure to phytoestrogens, the severity of nutrient restriction).

-

7)

Use of cross-fostering to study pregnancy and/or lactation-specific effects.

-

8)

Use of sham surgery to account for surgical-related influences on weight loss, exposure to anesthesia, and stress related to the procedure and recovery.

-

9)

Methodology (e.g., method for measurement of blood pressure, telemetry vs. tail cuff that may not detect small differences in blood pressure or may detect stress-related blood pressure response because of restraint), with discussion related to strengths, and limitations.

-

10)

The use of appropriate controls and control groups should be factored into the study design.

-

11)

The time of day and time of year in which measurements are made should be considered, to account for circadian regulation of metabolism and hormones.

-

12)

Specific timing of the developmental insult (days of gestation, lactational exposures).

-

13)

Specific timing of outcome measurements.

GUIDELINES FOR TRANSPARENT REPORTING OF RESULTS

-

1)

Provide description of the breeder male used in the breeding setup that led to the offspring being assessed. This is particularly important if studying paternal impacts on offspring health. Some basic information that should be mentioned include age at breeding, paternal weight, whether male is a proven breeder (successful pregnancies), and genotype (when applicable).

-

2) Report all essential pregnancy outcome variables

-

a) Maternal pregnancy information (parity and gravidity, gestational length, timing of any interventions during pregnancy, and any significant fluctuations in maternal physiology that may be relevant to interpretation of offspring data).

-

b) Birth weight.

-

c) Number of pups per litter born.

-

d) Sex composition of litter.

-

e) Number of pups that survived to weaning (if culling is not done).

-

f) If in utero measurements are applicable, the number of visible resorption sites and location of resorptions should be noted.

-

a)

-

3)

Culling of litter size versus postnatal accelerated growth as a programming event.

-

4)

Exposure type, dose, and timing (when initiated, duration of exposure, and any washout period).

-

5)

Lactation information. Authors should report whether exposures/treatments were continued during lactation. Whether cross-fostering was performed. Whether offspring underwent moments of maternal separation during lactation period.

-

6)

Age of offspring at weaning.

-

7)

Age of offspring at start of measurements (gestational, juvenile, or adult offspring). Rats and mice are altricial species, in which cardiovascular maturation continues past birth, becoming complete by the second week of postnatal life (104).

-

8)

Whether environmental enrichment was provided in the cages, type and amount of bedding used.

-

9)

Housing conditions: authors should specify how many animals per cage were housed together, whether offspring were singly housed, whether there were any deviations from normal housing conditions (temperature, light/dark cycle, other external sensory stimuli), whether cage handlers and animal care staff were consistent throughout the entire study, and the type of cages used: dimensions and floor materials (wired mesh cages used)?

BENEFITS TO RISKS ASSESSMENT OF MATERNAL INTERVENTIONS ON OFFSPRING

According to the theory of developmental origins of health and disease, perinatal stressors have an adverse effect on developmental trajectories, increasing offspring risk for chronic disease in adulthood (220, 221). Based on this notion, therapeutic interventions during critical windows of development may also alleviate the adverse effects of pregnancy complications on fetal development and reduce offspring risk of cardiovascular disease later in life. Pregnancy-specific experimental approaches to impact offspring cardiovascular development in utero include 1) systemic maternal treatments and 2) placenta-targeted therapeutics (222).

Systemic maternal treatment with antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, and compounds with nitric oxide-dependent cardioprotective effects have been widely used in experimental studies to target offspring cardiovascular development in commonly used preclinical animal models of pregnancy complications. Perinatal maternal treatment with resveratrol prevented the development of hypertension in the offspring in a genetic model of hypertension (222). In addition, systemic administration of melatonin (223), vitamins (224), or antioxidants (97, 225, 226) in pregnancies exposed to environmental stressors, such as nutrient restriction and hypoxia in preclinical models, prevented adverse cardiac and vascular remodeling and impaired cardiovascular function in fetal and adult offspring. Moreover, these interventions halted the development of hypertension and improved cardiac tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion injury in the offspring adult. Despite these beneficial effects, concerns have been raised about the readiness of systemic maternal treatments for clinical implementation. Resveratrol, ascorbate, and allopurinol can cross the placenta and some studies reported off-target effects of these compounds on fetal organ development (227, 228). Clinical studies echoed these concerns. Maternal supplementation with vitamins that have antioxidant properties increased the risk of low birthweight infants (227) in humans, whereas a clinical trial using sildenafil citrate to treat severe cases of FGR was stopped because of increased rates of neonatal mortality in the sildenafil-treated group (229).

SYSTEMIC MATERNAL TREATMENTS

Pros

-

1)

High feasibility of clinical implementation,

-

2)

Cost-effectiveness,

-

3)

Increased chances of implementation in low-resource settings.

Cons

-

1)

Off-target effects on maternal organs,

-

2)

Potential detrimental off-target effects on the offspring,

-

3)

Suggested contraindications in clinical trials.

The risks associated with systemic maternal treatments have led to the development of innovative approaches that specifically target the placenta. Recent innovations in the field of placenta-targeted therapeutics involve intraplacental treatments, engineered technologies of specific drug delivery systems, and short interfering RNA (222). Liposomes, adenoviral vectors, and nanoparticles have been used as vehicles of drug delivery in various preclinical models of pregnancy complications to improve offspring outcomes. Recent studies provided supportive evidence of beneficial effects of this tissue-targeted approach on offspring cardiovascular development. Antioxidant therapies via nanoparticle-linked delivery to the placenta in preclinical rodent models of intrauterine growth restriction improved offspring cardiac function, reduced susceptibility to cardiac ischemia-reperfusion, and improved mesenteric and pulmonary artery function in the adult offspring (100, 160). In primates, low levels of short interfering RNA reduced sFlt1 mRNA expression in the placenta and ameliorated preeclampsia-like features such as high maternal blood pressure and proteinuria (230).

PLACENTA-TARGETED TREATMENTS

Pros

-

1)

Improve drug properties, such as degradation and half-life properties,

-

2)

Prevent off-target effects,

Cons

-

1)

In developmental stages,

-

2)

Potential detrimental off-target effects on the offspring

-

3)

Long-term effects are understudied,

-

4)

Potentially high cost and low feasibility for implementation in low resource settings.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS IN PERINATAL THERAPEUTICS RESEARCH

-

1)

Timing of therapy: many preclinical studies initiate a therapeutic intervention at the time of inducing a complicated pregnancy experimentally. Clinically, however, treatment would occur after a complicated pregnancy has been diagnosed.

-

2)

Effects of therapy in controls: studies have shown effects of treatment in uncomplicated pregnancies; thus, precision diagnosis and therapy need to be developed.

-

3)

Timing of endpoint measurements: Coats et al. (231, 232) showed that long-term offspring consequences of perinatal treatment with a soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator did not parallel the improvements in obstetric-like outcomes such as uterine blood flow and fetoplacental weights at the end of gestation in a preclinical model of preeclampsia.

-

4)

Sex differences in treatment efficacy: a perinatal therapeutic intervention may have differential effects on male and female offspring outcomes. Ganguly et al. (233) reported that perinatal treatment of pregnant rats with antioxidant MitoQ encapsulated into nanoparticles (nMitoQ) was more effective in female compared with male placentas.

-

5)

Pregnancy-associated maternal physiological adaptations: these physiological adaptations and their influences on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are discussed in this collection [Guidelines for Assessing Maternal Cardiovascular Physiology During Pregnancy and Postpartum (5)].

-

6)

Ethical challenges in clinical application: as we described in previous sections, in utero exposures to various physiological and environmental stressors increase risk of offspring cardiovascular disease in humans and preclinical models. Nevertheless, an increase in risk does not always translate in pathology. Thus, it may be ethically challenging to use perinatal therapeutics in the clinic without absolute certainty that the affected offspring will become symptomatic later in life.

CONCLUSIONS

We recognize that in-depth discussion of all models of developmental insult is not included in this paper. However, based on our review of the current literature, there is strong evidence to support the link between adverse pregnancy or early postnatal developmental conditions and later life health complications in the exposed offspring. Designing well-controlled studies and transparency in the reporting of methods and results are critical to advancing our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the link between these early life exposures and cardiovascular risks in the offspring. In addition, considering the advantages and limitations of each model and discussing the limitations will ensure a more reliable publication record, thus increasing rigor and reproducibility of results. Importantly, use of preclinical models of developmental insult provides critical insight into the identification of potential therapeutic targets. Translational benefits also involve the ability to develop interventional strategies that benefit the mother and the fetus while not inducing further harm to the developing fetus. This guideline article extends the intent of the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology to provide guidelines on topics relevant to cardiovascular research and to improve overall rigor and reproducibility in the field (219, 234–237).

GRANTS

The contributing authors were supported by the following grants: B. T. Alexander by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01HL143459, P20GM104357, P30GM14940, and P20GM121334; J. M. do Carmo by NIH Grants P01HL51971, P20GM104357, P30GM149404, U54GM115428, R01DK121411, and 1R01HL163076; H. E. Collins by NIH Grants R01HL163003, R01HL147844, and R01HL163818 and Jewish Heritage Fund For Excellence Faculty Support Grant; S. T. Davidge by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant FS154313; A. S. Loria by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL135158; S. Goulopoulou by NIH Grants R01HL146562 and HL146562-04S1; J. L. Sones by NIH Grant P20GM135002; J. P. Warrington by NIH Grants R56HL159447; and L. E. Wold by American Heart Association Grants 23SFRNPCS1067044 and 20YVNR35490079 and NIH Grants R01HL139348 and R01AG057046.

DISCLAIMERS

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or other listed founding agency.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.P.W. and J.M.d.C. prepared figures; J.P.W., S.T.D., J.M.d.C., S.G., S.I., A.S.L., J.L.S., L.E.W., E.K.Z., and B.T.A. drafted manuscript; J.P.W., H.E.C., S.T.D., J.M.d.C., S.G., S.I., A.S.L., J.L.S., L.E.W., E.K.Z., and B.T.A. edited and revised manuscript; J.P.W., H.E.C., S.T.D., J.M.d.C., S.G., S.I., A.S.L., J.L.S., L.E.W., E.K.Z., and B.T.A. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge that no artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bleker LS, de Rooij SR, Painter RC, Ravelli AC, Roseboom TJ. Cohort profile: the Dutch famine birth cohort (DFBC)—a prospective birth cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 11: e042078, 2021. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ravelli GP, Stein ZA, Susser MW. Obesity in young men after famine exposure in utero and early infancy. N Engl J Med 295: 349–353, 1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608122950701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raikkonen K, Kajantie E, Pesonen AK, Heinonen K, Alastalo H, Leskinen JT, Nyman K, Henriksson M, Lahti J, Lahti M, Pyhälä R, Tuovinen S, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG. Early life origins cognitive decline: findings in elderly men in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. PLoS One 8: e54707, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 311: 171–174, 1995. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collins HE, Alexander BT, Care AS, Davenport MH, Davidge ST, Eghbali M, Giussani DA, Hoes MF, Julian CG, LaVoie HA, Olfert IM, Ozanne SE, Bytautiene Prewit E, Warrington JP, Zhang L, Goulopoulou S. Guidelines for assessing maternal cardiovascular physiology during pregnancy and postpartum. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. In press. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00055.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woodall SM, Johnston BM, Breier BH, Gluckman PD. Chronic maternal undernutrition in the rat leads to delayed postnatal growth and elevated blood pressure of offspring. Pediatr Res 40: 438–443, 1996. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kawamura M, Itoh H, Yura S, Mogami H, Suga S, Makino H, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Sagawa N, Fujii S. Undernutrition in utero augments systolic blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in adult mouse offspring: possible involvement of local cardiac angiotensin system in developmental origins of cardiovascular disease. Endocrinology 148: 1218–1225, 2007. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawamura M, Itoh H, Yura S, Mogami H, Fujii T, Makino H, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Aoe S, Ogawa Y, Sagawa N, Kanayama N, Konishi I. Isocaloric high-protein diet ameliorates systolic blood pressure increase and cardiac remodeling caused by maternal caloric restriction in adult mouse offspring. Endocr J 56: 679–689, 2009. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mossa F, Carter F, Walsh SW, Kenny DA, Smith GW, Ireland JL, Hildebrandt TB, Lonergan P, Ireland JJ, Evans AC. Maternal undernutrition in cows impairs ovarian and cardiovascular systems in their offspring. Biol Reprod 88: 92, 2013. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.107235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilbert JS, Lang AL, Grant AR, Nijland MJ. Maternal nutrient restriction in sheep: hypertension and decreased nephron number in offspring at 9 months of age. J Physiol 565: 137–147, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vickers MH, Breier BH, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL, Gluckman PD. Fetal origins of hyperphagia, obesity, and hypertension and postnatal amplification by hypercaloric nutrition. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E83–E87, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.1.E83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Almeida JR, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Maternal gestational protein-calorie restriction decreases the number of glomeruli and causes glomerular hypertrophy in adult hypertensive rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192: 945–951, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Clin Sci (Lond) 86: 217–222, 1994. discussion 121. doi: 10.1042/cs0860217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr Res 49: 460–467, 2001. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsukuda K, Mogi M, Iwanami J, Min LJ, Jing F, Ohshima K, Horiuchi M. Influence of angiotensin II type 1 receptor-associated protein on prenatal development and adult hypertension after maternal dietary protein restriction during pregnancy. J Am Soc Hypertens 6: 324–330, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bezerra DG, Lacerda Andrade LM, Pinto da Cruz FO, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Atorvastatin attenuates cardiomyocyte loss in adult rats from protein-restricted dams. J Card Fail 14: 151–160, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci 64: 965–974, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zohdi V, Pearson JT, Kett MM, Lombardo P, Schneider M, Black MJ. When early life growth restriction in rats is followed by attenuated postnatal growth: effects on cardiac function in adulthood. Eur J Nutr 54: 743–750, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Langley-Evans SC. Fetal programming of cardiovascular function through exposure to maternal undernutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 60: 505–513, 2001. doi: 10.1079/pns2001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blackmore HL, Piekarz AV, Fernandez-Twinn DS, Mercer JR, Figg N, Bennett M, Ozanne SE. Poor maternal nutrition programmes a pro-atherosclerotic phenotype in ApoE−/− mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 123: 251–257, 2012. doi: 10.1042/CS20110487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silva-Junior GO, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Insights into coronary artery development in model of maternal protein restriction in mice. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 294: 1757–1764, 2011. doi: 10.1002/ar.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernandez-Twinn DS, Ekizoglou S, Wayman A, Petry CJ, Ozanne SE. Maternal low-protein diet programs cardiac β-adrenergic response and signaling in 3-mo-old male offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R429–R436, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00608.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheema KK, Dent MR, Saini HK, Aroutiounova N, Tappia PS. Prenatal exposure to maternal undernutrition induces adult cardiac dysfunction. Br J Nutr 93: 471–477, 2005. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief 360: 1–8, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, Sattar N, Brion MJ, Benfield L, Ness A, Deanfield J, Hingorani A, Nelson SM, Smith GD, Lawlor DA. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation 121: 2557–2564, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mamun AA, O'Callaghan M, Callaway L, Williams G, Najman J, Lawlor DA. Associations of gestational weight gain with offspring body mass index and blood pressure at 21 years of age: evidence from a birth cohort study. Circulation 119: 1720–1727, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wright JD, Wang CY, Kennedy-Stephenson J, Ervin RB. Dietary intake of ten key nutrients for public health, United States: 1999–2000. Adv Data 334: 1–4, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferey JLA, Boudoures AL, Reid M, Drury A, Scheaffer S, Modi Z, Kovacs A, Pietka T, DeBosch BJ, Thompson MD, Diwan A, Moley KH. A maternal high-fat, high-sucrose diet induces transgenerational cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction independently of maternal mitochondrial inheritance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 316: H1202–H1210, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00013.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. do Carmo JM, Omoto ACM, Dai X, Moak SP, Mega GS, Li X, Wang Z, Mouton AJ, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Sex differences in the impact of parental obesity on offspring cardiac SIRT3 expression, mitochondrial efficiency, and diastolic function early in life. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 321: H485–H495, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00176.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller TA, Dodson RB, Mankouski A, Powers KN, Yang Y, Yu B, Ek Z. Impact of diet on the persistence of early vascular remodeling and stiffening induced by intrauterine growth restriction and a maternal high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317: H424–H433, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00127.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dodson RB, Miller TA, Powers K, Yang Y, Yu B, Albertine KH, Zinkhan EK. Intrauterine growth restriction influences vascular remodeling and stiffening in the weanling rat more than sex or diet. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H250–H264, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00610.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maloyan A, Muralimanoharan S, Huffman S, Cox LA, Nathanielsz PW, Myatt L, Nijland MJ. Identification and comparative analyses of myocardial miRNAs involved in the fetal response to maternal obesity. Physiol Genomics 45: 889–900, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00050.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang Y, Yan X, Zhao JX, Zhu MJ, McCormick RJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Ren J, Du M. Maternal obesity induces fibrosis in fetal myocardium of sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E968–E975, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mitra A, Alvers KM, Crump EM, Rowland NE. Effect of high-fat diet during gestation, lactation, or postweaning on physiological and behavioral indexes in borderline hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R20–R28, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90553.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khan IY, Dekou V, Douglas G, Jensen R, Hanson MA, Poston L, Taylor PD. A high-fat diet during rat pregnancy or suckling induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R127–R133, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00354.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loos RJ, Lindgren CM, Li S, Wheeler E, Zhao JH, Prokopenko I, , et al. Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat Genet 40: 768–775, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ng.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cordero P, Li J, Nguyen V, Pombo J, Maicas N, Novelli M, Taylor PD, Samuelsson AM, Vinciguerra M, Oben JA. Developmental programming of obesity and liver metabolism by maternal perinatal nutrition involves the melanocortin system. Nutrients 9: 1041, 2017. doi: 10.3390/nu9091041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Samuelsson AS, Mullier A, Maicas N, Oosterhuis NR, Eun Bae S, Novoselova TV, Chan LF, Pombo JM, Taylor PD, Joles JA, Coen CW, Balthasar N, Poston L. Central role for melanocortin-4 receptors in offspring hypertension arising from maternal obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 12298–12303, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607464113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Spradley FT, Palei AC, Granger JP. Obese melanocortin-4 receptor-deficient rats exhibit augmented angiogenic balance and vasorelaxation during pregnancy. Physiol Rep 1: e00081, 2013. doi: 10.1002/phy2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spradley FT, Palei AC, Anderson CD, Granger JP. Melanocortin-4 receptor deficiency attenuates placental ischemia-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 73: 162–170, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fowden AL, Li J, Forhead AJ. Glucocorticoids and the preparation for life after birth: are there long-term consequences of the life insurance? Proc Nutr Soc 57: 113–122, 1998. doi: 10.1079/pns19980017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen YT, Hu Y, Yang QY, Son JS, Liu XD, de Avila JM, Zhu MJ, Du M. Excessive glucocorticoids during pregnancy impair fetal brown fat development and predispose offspring to metabolic dysfunctions. Diabetes 69: 1662–1674, 2020. doi: 10.2337/db20-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bal MP, de Vries WB, van Oosterhout MF, Baan J, van der Wall EE, van Bel F, Steendijk P. Long-term cardiovascular effects of neonatal dexamethasone treatment: hemodynamic follow-up by left ventricular pressure-volume loops in rats. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, MD: 1985) 104: 446–450, 2008. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00951.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boubred F, Daniel L, Buffat C, Tsimaratos M, Oliver C, Lelievre-Pegorier M, Simeoni U. The magnitude of nephron number reduction mediates intrauterine growth-restriction-induced long term chronic renal disease in the rat. A comparative study in two experimental models. J Transl Med 14: 331, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li M, Wood CE, Keller-Wood M. Chronic maternal hypercortisolemia models stress-induced adverse birth outcome and altered cardiac function in newborn lambs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 323: R193–R203, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00041.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Antolic A, Wood CE, Keller-Wood M. Chronic maternal hypercortisolemia in late gestation alters fetal cardiac function at birth. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314: R342–R352, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00296.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hai CM, Sadowska G, Francois L, Stonestreet BS. Maternal dexamethasone treatment alters myosin isoform expression and contractile dynamics in fetal arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1743–H1749, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00281.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fallouh B, Nair H, Langman G, Baharani J. The case: unusual cause of acute renal failure in a patient with HIV. Diagnosis: tuberculous granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int 78: 117–118, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ilg L, Klados M, Alexander N, Kirschbaum C, Li SC. Long-term impacts of prenatal synthetic glucocorticoids exposure on functional brain correlates of cognitive monitoring in adolescence. Sci Rep 8: 7715, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26067-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Woods LL, Weeks DA. Prenatal programming of adult blood pressure: role of maternal corticosteroids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R955–R962, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00455.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Regan D, Kenyon CJ, Seckl JR, Holmes MC. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation in the rat permanently programs gender-specific differences in adult cardiovascular and metabolic physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E863–E870, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00137.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moritz KM, De Matteo R, Dodic M, Jefferies AJ, Arena D, Wintour EM, Probyn ME, Bertram JF, Singh RR, Zanini S, Evans RG. Prenatal glucocorticoid exposure in the sheep alters renal development in utero: implications for adult renal function and blood pressure control. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R500–R509, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00818.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dodic M, Samuel C, Moritz K, Wintour EM, Morgan J, Grigg L, Wong J. Impaired cardiac functional reserve and left ventricular hypertrophy in adult sheep after prenatal dexamethasone exposure. Circ Res 89: 623–629, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.097086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ortiz LA, Quan A, Weinberg A, Baum M. Effect of prenatal dexamethasone on rat renal development. Kidney Int 59: 1663–1669, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wintour EM, Moritz KM, Johnson K, Ricardo S, Samuel CS, Dodic M. Reduced nephron number in adult sheep, hypertensive as a result of prenatal glucocorticoid treatment. J Physiol 549: 929–935, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ortiz LA, Quan A, Zarzar F, Weinberg A, Baum M. Prenatal dexamethasone programs hypertension and renal injury in the rat. Hypertension 41: 328–334, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049763.51269.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shaltout HA, Rose JC, Figueroa JP, Chappell MC, Diz DI, Averill DB. Acute AT(1)-receptor blockade reverses the hemodynamic and baroreflex impairment in adult sheep exposed to antenatal betamethasone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H541–H547, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00100.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tang L, Bi J, Valego N, Carey L, Figueroa J, Chappell M, Rose JC. Prenatal betamethasone exposure alters renal function in immature sheep: sex differences in effects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R793–R803, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00590.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alhamoud I, Legan SK, Gattineni J, Baum M. Sex differences in prenatal programming of hypertension by dexamethasone. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 246: 1554–1562, 2021. doi: 10.1177/15353702211003294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Valenzuela OA, Jellyman JK, Allen VL, Niu Y, Holdstock NB, Forhead AJ, Giussani DA, Fowden AL, Herrera EA. Neonatal glucocorticoid overexposure alters cardiovascular function in young adult horses in a sex-linked manner. J Dev Orig Health Dis 12: 309–318, 2021. doi: 10.1017/S2040174420000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tang L, Carey LC, Bi J, Valego N, Sun X, Deibel P, Perrott J, Figueroa JP, Chappell MC, Rose JC. Gender differences in the effects of antenatal betamethasone exposure on renal function in adult sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R309–R317, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90645.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dagan A, Kwon HM, Dwarakanath V, Baum M. Effect of renal denervation on prenatal programming of hypertension and renal tubular transporter abundance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F29–F34, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00123.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 713: antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol 130: e102–e109, 2017. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kulas JA, Hettwer JV, Sohrabi M, Melvin JE, Manocha GD, Puig KL, Gorr MW, Tanwar V, McDonald MP, Wold LE, Combs CK. In utero exposure to fine particulate matter results in an altered neuroimmune phenotype in adult mice. Environ Pollut 241: 279–288, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tanwar V, Adelstein JM, Grimmer JA, Youtz DJ, Sugar BP, Wold LE. PM(2.5) exposure in utero contributes to neonatal cardiac dysfunction in mice. Environ Pollut 230: 116–124, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tanwar V, Gorr MW, Velten M, Eichenseer CM, Long VP 3rd, Bonilla IM, Shettigar V, Ziolo MT, Davis JP, Baine SH, Carnes CA, Wold LE. In utero particulate matter exposure produces heart failure, electrical remodeling, and epigenetic changes at adulthood. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e005796, 2017. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gorr MW, Velten M, Nelin TD, Youtz DJ, Sun Q, Wold LE. Early life exposure to air pollution induces adult cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1353–H1360, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00526.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wold LE, Ying Z, Hutchinson KR, Velten M, Gorr MW, Velten C, Youtz DJ, Wang A, Lucchesi PA, Sun Q, Rajagopalan S. Cardiovascular remodeling in response to long-term exposure to fine particulate matter air pollution. Circ Heart Fail 5: 452–461, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.966580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]