Abstract

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus are vectors of arboviruses and have different levels of resistance to synthetic insecticides, such as the organophosphate temephos, according to their area of occurrence. As an alternative, there are semisynthetic substances with potential insecticidal effect; however, they need to be fully tested by an effective method for the mosquito control. The semi-synthetic dillapiole n-butyl ether exhibits toxic ovicidal and larvicidal activity in both mosquito species. However, has no proven the mutagenicity and cytotoxicity risks of this larvicide in drinking water effect for consumption by non-target organisms, such as in humans neither in other vertebrates, which access pools of water contain this sprayed substance. In this sense, both of the biomarkers of the genotoxicity, the micronucleus (MN) and comet, using this substance were tested in Balb/C mice to assess the genetic damage and risks of its application as a mitigating measure against Ae. aegypti. Male specimens (n = 60) were exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg via a comet assay in peripheral blood (n = 30) and a micronucleus test in bone marrow cells (n = 30). The induction of mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of dillapiole n-butyl ether in these animals occurred only at a concentration of 40 mg/kg, in multiple treatments. However, dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 20 and 10 mg/kg has potential for use against Ae. aegypti in the form of a larvicide in water for consumption by humans and other vertebrates a new vector control measure.

Keywords: Dengue fever, Citogenotoxicity, Bioinsecticides, Vector control

1. Introduction

Aedes aegypti is the main vector of emerging and re-emerging dengue virus (DENV), chikungunya virus (CHIKV), yellow fever virus (YFVV) and Zika virus (ZIKV) [11]. The resistance of mosquitoes of epidemiological importance to conventional pesticides and the safety of their application in vector control are points that deserve attention [27]. For about 30 years, temephos, from the organophosphate class, has been the only larvicide approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) for use in drinking water in Ae. aegypti control campaigns [8]. However, since the late 1990s, there have been reports of changes in the susceptibility of this mosquito [4], [5].

Thus, new methodologies and new substances for controlling Ae. aegypti are necessary in order to optimize the integrated management of this vector [36], [37]. In addition to the search for new substances for vector control and new vector control methodologies, there is also concern about their low impact on non-target organisms or the minimization of risks to the safety of these organisms. Thus, new research on environmentally safe insecticides and other alternatives for the control of Ae. aegypti and Aedes albopictus are necessary given the scarce number of studies in the literature on available insecticides for use in vector control campaigns.

One possible solution is the semi-synthetic dillapiole n-butyl ether, which has broad ovicidal and larvicidal activity in Ae. aegypti [9] and Ae. albopictus [19]. It is derived from dillapiole, a main component in the essential oil of the plant Piper aduncum [7], which is widely distributed in the Amazon region [16]. However, data regarding the cytogenotoxicity of dillapiole n-butyl ether in mammals [38] are scarce.

In the case of cytogenotoxicity, some biomarkers are used to test substances in mammalian cells. Among the biomarkers of genotoxicity, the micronucleus (MN) frequency can detect clastogenic and aneugenic agents, but is not suitable for detecting single strand breaks [39]. Moreover, the comet assay does not detect genetic damage induced by aneugenic agents [21]. Thus, these facts reflect the need for the joint use of these two tests for the detection of genetic damage.

The present study aims to further the knowledge about the cytogenotoxic activity of dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) in Mus musculus (Balb/C) mice by using the comet assay in peripheral blood and the micronucleus test in bone marrow, in order to evaluate the safety of its possible application as a larvicide against Ae. Aegypti for use in drinking water, and for the mosquito control. Therefore, the present study aim to set up DBE genotoxic potential in mamalian, such as Balb/C mice, attentive to genotoxicity, before go on with future ecotoxicity studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation of dillapiole from Piper aduncum

A total of 20 kg of P. aduncum (leaves, thin stems and flowers) grown at Embrapa Amazônia Occidental, KM 23 of state highway AM-010, Amazonas state, Brazil, were dehydrated in an oven at 40 °C. A sample of 12.5 kg of the dry material was distilled in a Clevenger apparatus, which provided 25 mL of light-yellow oil (24.1 g, 1.082 g.mL−1). The fraction rich in dillapiole (17.7 g, 72.1 % v/v) was obtained from the isolate via column chromatography (20 cm height; 1.5 cm diameter) using hexane:acetone (95:5).

2.2. Mercuriation procedure of the dillapiole ethers

The dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) was prepared by dissolving dillapiole in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and adding a suspension of Hg(OAc)2 in n-butanol alcohol with magnetic stirring under nitrogen. The reaction was left at room temperature for 72 hours, and the organomercury intermediate was then reduced by adding an alkaline solution of NaBH4 for 5–10 min. The Hg° was removed by filtration and the filtrate was extracted using CHCl3. The combined CHCL3 phases were washed with water, NaCl sat. aq., and dried with anhydrous MgSO4. The ether was obtained after evaporation of the solvent. The crude product was purified by using normal phase column chromatography and the pure ether was obtained in yield of 4.1 g, which is equivalent to 73 % of the theoretical yield. The DBE was confirmed via RMN 1H (CDCl3; 500 MHz): 6.40 s; 2.83 dd; 2.53 dd; 3.56 sext; 1.12 d; 5.89 s; 3.48 m; 3.38 m; 3.77 s (OMe); 4.02 s (OMe); 1.51 m; 1.34 sext; 0.89 t. RMN 13C (CDCl3; 125 MHz): 14.1; 19.6; 19.9; 32.4; 37.2; 60.1; 61.3; 68.7; 76.2; 101.3; 103.9; 125.5; 136.1; 137.7; 144.5; 144.9. DBE, a structural analogue of dillapiole (CAS 484–31–1), is registered under patent BR1020120333376 at the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), Brazil.

2.3. Animal housing and feeding

Male Balb/C mice of eight weeks of age and weighing approximately 25 g at the beginning of the experiments were obtained from the central vivarium of the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA), Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil. The experimental procedures involving these animals were carried out according to the protocols approved by the INPA Ethics Commission for Animal Use (CEUA), according to approval N°. 008/2020, SEI 01280.000181/2020–90. The animals were kept in an environment with a temperature of 22 ºC, relative humidity of 60 ± 10 %, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. They were subsequently transferred to polysulfone microinsulators with ad libitum access to water and food, except for the short period of fasting before and after oral administration of the DBE, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), methylmethanesulfonate (MMS) and phosphate-saline buffer (PBS).

2.4. Experimental design for the comet assay and micronucleus test

The comet assay and micronucleus test were performed using 60 male Balb/C mice in each test. The animals received multiple treatments of 0.1 mL of DBE per 10 g of body weight by gavage for three consecutive days, with an interval of 24 hours between treatments. Two experimental sets were used in the two tests. Each set contained 30 animals, which was divided into six groups of five animals. For the comet assay, in set 1, the animals were euthanized 4 hours after the last treatment, and animals in set 2 were euthanized 24 hours after the last treatment. For the micronucleus test, in sets 1 and 2, the euthanasia of the subjects occurred 24 hours and 48 hours after the last treatment, respectively.

The first group received only filtered water and was the negative control. In the second group, the solvent/dilution vehicle of the DBE, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 5 %, was administered and was named the solvent control. The third, fourth and fifth groups received DBE in three concentrations (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg), comprising the values of 25 %, 50 % and 100 % of the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), respectively, which were previously established in our laboratory, following the principles of OECD guideline 420 (2001). In the sixth group, which was the positive control, methylmethanesulfonate (MMS) (40 mg/kg) was used and the solvent/dilution vehicle of this compound was phosphate-saline buffer (PBS).

2.5. Sample collection and comet assays

The comet assay was performed according to the protocol established by Singh et al. [32], Tice et al. [33] and [24], with minor modifications. In this test, the Balb/C mice were injected intraperitoneally with ketamine solution (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) 4 and 24 hours after treatment. Blood, which was collected in the absence of artificial light and obtained by cardiac puncture, was kept in Eppendorfs, containing 5 mL of sodium heparin (400 µL/mL).

The mixture of 10 µL of blood and 120 µL of low melting point agarose (0.5 %) was spread over the slides coated with normal melting point agarose (1.5 %). The cells were covered with a coverslip and kept at 4 °C for 10 minutes. The coverslips were removed from the slides and immersed in a freshly prepared lysis solution consisting of 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 10 % dimethyl sulfoxide, 1 % Triton X-100 and 10 mM Tris, pH 10, for 60 min at 4 °C. After lysis, the slides were transferred to a horizontal electrophoresis vessel containing 300 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA at pH> 13, and maintained for 40 minutes for DNA denaturation. Electrophoresis was performed at 1 V/cm (25 V and 300 mA) for 20 min. The slides were then immersed in a neutralization buffer (0.4 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) for 15 min. After drying at room temperature, the slides were fixed in ethanol for 10 minutes and stored for subsequent staining and analysis. Each slide was stained using 30 µL of ethidium bromide (20 µL/mL), and analyzed immediately.

The microphotographs were captured under epi-fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager A2 Zeiss), using a Cy3 filter, with a wavelength of 510–575 nm, and then transferred to the Comet Score 2.0 software. A total of 150 comets from each animal were analyzed, which equates to 750 comets per treated group, using the parameters Tail Length (mm), Tail DNA (%) and Tail Moment (arbitrary units).

2.6. Sample collection and micronucleus test

The micronucleus test was performed according to Tice et al. (1990a), Tice et al. (1990b) and the principles of OECD guideline 474 (2016). In this test, the mice were euthanized with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), by intraperitoneal injection 24 hours and 48 hours after treatment. Soon after, necropsy was performed on each individual to remove bone marrow cells from the femurs. During the necropsy, the femurs were carefully excised, and the proximal epiphyses were cut to expose the bone marrow canal. The marrow (cell suspension) of each animal was extracted using a syringe needle (1 mL) containing fetal bovine serum into a centrifuge tube. Bone marrow material was resuspended in fetal bovine serum using a Pasteur pipette. Then, after homogenization, the suspension was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1000 rpm. The precipitated material at the bottom of the microtube was eluted in 0.5 mL of fetal bovine serum. The smears were prepared by dripping two drops of the suspension onto the matte end of a slide.

Bone marrow samples from Balb/C mice after undergoing the slide smear procedure were fixed in methanol and stained with Leishman eosin-blue. The frequency of the polychromatic erythrocytes (PCE) was expressed as a proportion of the total number of erythrocytes (PCE + normochromatic erythrocytes (NCE)), and the PCE:NCE ratio was also determined by counting 500 erythrocytes per animal. The incidence of micronucleated immature erythrocytes was expressed as the MN frequency, which was calculated by counting a total of 4000 cells per animal.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results of the micronucleus test are presented as ± SD for each group of Balb/C mice and statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparison using the Tukey test, at 5 % probability of error. Analysis of the comet assay data showed significance by means of the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, and Fisher’s minimum significant difference test was applied, with Bonferroni correction, on the average ranks of the compared treatments. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version R 4.1.0. The value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Comet assays

In the blood of Balb/C mice, according to the Tail Length parameter, there was no significant difference between the negative control (NC) and the solvent control (SC) in relation to the concentrations of 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg of DBE, at 4 and 24 hours (Fig. 1). However, the positive control (PC) showed a large increase in damaged DNA when compared to the SC (DMSO) and the test substance (DBE).

Fig. 1.

Genotoxic effect of dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) by the comet assay using the Tail Length parameter in blood of male Balb/C mice (n = 5, per treatment) exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg and three controls (water = negative control; 5 % DMSO = solvent control [dimethyl sulfoxide]; PC = positive control [methyl methanesulfonate]), at 4 and 24 hours after the start of treatment. The statistical analysis was according to Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher’s test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data with identical letters do not differ significantly from each other.

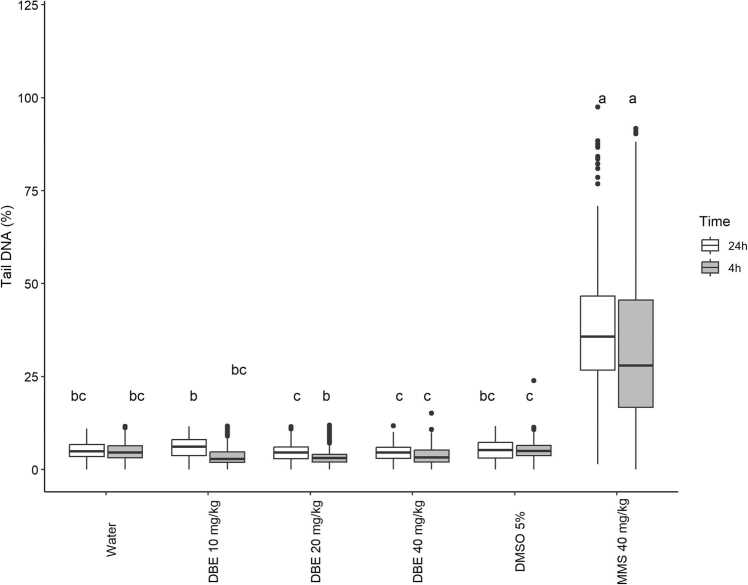

In the Tail DNA variable (Fig. 2), at the timepoint of 4 hours, only the concentration of 20 mg/kg showed a slight increase in damaged DNA when compared to the SC. The PC showed a high increase in DNA damage when compared to the SC (DMSO) and the test substance (DBE).

Fig. 2.

Genotoxic effect of dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) by means of the comet assay using the Tail DNA parameter in the blood of male Balb/C mice (n = 5, per treatment) exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg and three controls (water = negative control; 5 % DMSO = solvent control [dimethyl sulfoxide]; PC = positive control [methyl methanesulfonate]), at 4 and 24 hours after the start of treatment. The statistical analysis was according to Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher’s test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data with identical letters do not differ significantly from each other.

In the analysis using the Tail Moment parameter (Fig. 3), at both 4 and 24 hours, the three concentrations of EDB (40, 20, and 10 mg/kg) did not show an increase in DNA damage frequency when compared to the negative control (NC) and positive control (PC). The PC showed a high frequency of DNA damage in relation to the SC (DMSO) and the test substance (DBE).

Fig. 3.

Genotoxic effect of dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) by means of the comet assay using the Tail Moment parameter in the blood of male Balb/C mice (n = 5, per treatment) exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg and three controls (water = negative control; 5 % DMSO = solvent control [dimethyl sulfoxide]; PC = positive control [methyl methanesulfonate]), at 4 and 24 hours after the start of treatment. The statistical analysis was according to Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher’s test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data with identical letters do not differ significantly from each other.

3.2. Micronucleus test

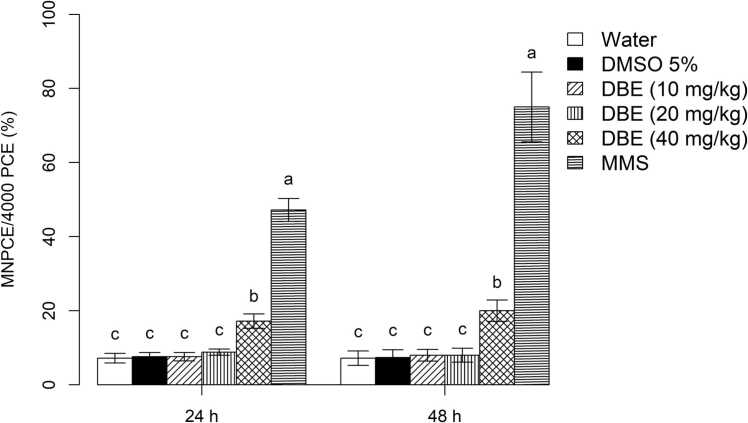

Fig. 4 expresses the rates of micronucleated polychromatic erythrocyte (MNPCE) from the bone marrow of the Balb/C mice, for which the number of MN did not change at concentrations of 10 and 20 mg/kg of DBE, as there was no statistically significant reduction in the MNPCE frequency in the total erythrocytes analyzed, when compared to the NC and SC, at the timepoints of 24 and 48 hours. However, a significant increase in MNPCE per cell occurred only at a concentration of 40 mg/kg of DBE when compared to the NC and SC at these two timepoints. Notwithstanding, the PC showed a high increase in MNPCE when compared to the concentration of 40 mg/kg of DBE, at both timepoints.

Fig. 4.

Mean±SD frequency of MNPCEs by means of the micronucleus test in the bone marrow cells of male Balb/C mice (n = 5 per treatment) exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) at concentrations of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg and three controls (water = negative control; 5 % DMSO = solvent control [dimethyl sulfoxide]; PC = positive control [methyl methanesulfonate]), at 24 and 48 hours after the beginning of treatment. The statistical analysis was according to ANOVA and Tukey’s test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data with identical letters do not differ significantly from each other.

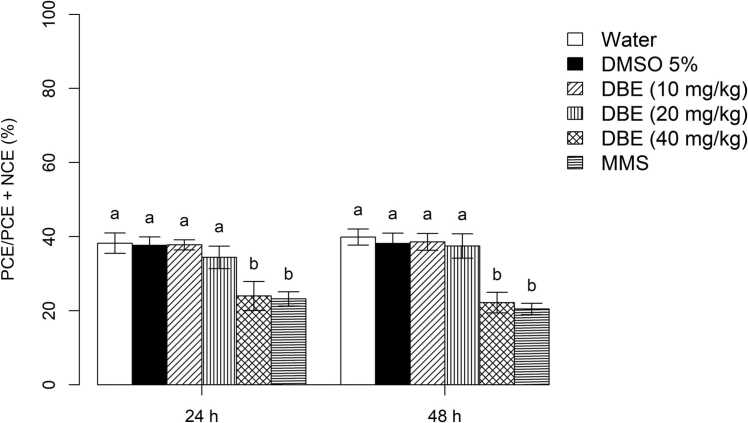

In the bone marrow cells of Balb/C mice, the cytotoxic effects of DBE at the lowest concentrations (10 and 20 mg/kg), at 24 hours and 48 hours, showed no significant decrease in the frequency of PCE in the PCE:NCE ratio, when compared to the NC and SC (Fig. 5). However, at the DBE concentration of 40 mg/kg, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of PCE when compared to the NC and SC, but it did not differ from the PC, at both timepoints.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity in the bone marrow cells of male Balb/C mice (n = 5, per treatment) exposed to dillapiole n-butyl ether at concentrations of 10, 20 or 40 mg/kg and three controls (water = negative control; 5 % DMSO = solvent control [dimethyl sulfoxide]; PC = positive control [methyl methanesulfonate]), at 24 and 48 hours after the beginning of treatment. The PCE/PCE+NCE ratio (given as the mean±SD) is based on the examination of 500 erythrocytes per mouse. The statistical analysis was according to ANOVA and Tukey’s test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data with identical letters do not differ significantly from each other.

4. Discussion

Dillapiole, in addition to DBE, has several other semi-synthetic derivatives, such as dillapiole methyl ether, dillapiole ethyl ether, dillapiole propyl ether, dillapiole octyl ether, dillapiole diol, and isodillapiole, which have larvicidal activity in Ae. aegypti and antiprotozoal activity against Leishmania amazonenses [2]. The ovicidal, larvicidal and genotoxic activity of dillapiole in Ae. aegypti is well documented [25], as well as the increase in this activity when this component is linked to the butyl group, both against Ae. aegypti [9] and against Ae. albopictus [19]. Other dillapiole derivatives such as isodylapiol and dillapiole methyl ether also showed toxic and genotoxic effects against Ae. aegypti [14]; [26]; [31], even at the lowest concentrations tested [31].

However, dillapiole n-butyl ether (DBE) proved to be the most potent larvicide among the dillapiole derivatives (Domingos et al., 2016). In the study by Viana Cruz et al. [38], this substance induced genotoxic, mutagenic and cytotoxic effects in male Balb/C mice, at the highest concentrations of DBE (150 and 328 mg/kg), which are higher than those tested in mosquitoes. The concentrations of 80, 150 and 328 mg/kg used by these authors corresponded to 25 %, 50 % and 80 %, respectively, of the LD50, with a single treatment. In this study, the comet test, with peripheral blood, and the micronucleus test, with bone marrow, at concentrations of 150 and 328 mg/kg showed induction of breaks in the DNA double strand, the formation of MN and inhibition of cell division or induction of irreversible cell lesions. Thus, it was necessary to further investigate the in vivo cytogenotoxic effects of the semi-synthetic DBE, using multiple treatments and in concentrations lower than those used by Viana Cruz et al. [38] in order to simulate the frequent use of this derivative as a larvicide in drinking water at concentrations closer to the lethal concentrations (100 %) against the larvae of Ae. aegypti.

The hazard/risk assessment of chemicals in general goes through several phases and in vivo tests with different animal models, especially those related to genotoxicity [12]. Among these parameters, the comet assay is a widely used technique for investigating DNA damage. In the present study, DNA preservation occurred at all DBE concentrations used in the Tail Length variable, at 4 and 24 hours. Viana Cruz et al. [38], using concentrations of 80, 150 and 328 mg/kg, with a single treatment, observed the absence of DNA damage in Balb/C mice at the timepoint of 4 hours; however, there was an increased frequency of DNA damage at all concentrations at the timepoint of 24 hours. This absence of damage within 4 hours can be explained by the application of a single treatment, whereas in the present study multiple treatments were used.

Another well-established parameter is the micronucleus test Fenech and Morley, 1985; de Sá et al., ; Kruskal, Wallis ; Martins, Lima ; OECD ; LHFD et al., ; Schmid; Tice et al.,; Tice et al., [10], [8], [13], [18], [22], [26], [29], [34], [35]. MN originate from delayed chromatin in the anaphase of mitosis or meiosis, because of chromosomal breakage, thus generating acentric and di - or multicentric chromosomal fragments, or from the malfunction of the spindle apparatus, forming whole chromatids. In the telophase, MN is included in one of the daughter cells, in which it can fuse with the main nucleus or form one or several secondary nuclei. Thus, these MN are composed of chromosomal fragments, usually much smaller than the main nucleus. In the bone marrow of mammals subjected to mutagenic substances, upon completion of one or more mitoses, MN can be detected in several cell types [29].

The micronucleus test has become one of the main in vivo screening methods for evaluating genotoxicity in erythrocytes collected from bone marrow or peripheral blood cells of animals, usually rodents [23], and is a useful tool in assessing the safety of the use of synthetic substances. It is used in the investigation of potential insecticides and the development of new products for the control of vectors of arbovirus, such as temephos-resistant Ae. aegypti [4], [30], [20], [28]. Semi-synthetics with potential larvicidal effect are being studied [2]. The study by Manwill et al. [17] demonstrated the larvicidal activity of cinnamodial (CDIAL), a unique sesquiterpene dialdehyde from the medicinal plant Cinnamosma fragrans, and several semi-synthetics, against first-stage larvae of Ae. aegypti using a concentration of 100 µM, which killed 70 % of the larvae in 24 hours. Almost all derivatives of CDIAL showed significantly lower efficacy than CDIAL. However, only the semi-synthetic (-)-6ß-acetoxy-9α-hydroxydrim-7-ene-12-methyl-12-one-11-al killed 100 % of the larvae.

Domingos et al. [9] obtained even more promising results regarding the toxic effects of DBE in third stage larvae of Ae. aegypti, since they registered lethal effects with an LC50 of 18 µg/mL and LC90 of 27 µg/mL after 24 hours of exposure. On the other hand, Meireles et al. [19] evaluated this compound in Ae. albopictus and obtained an LC50 of 25 µg/mL and an LC90 of 41 µg/mL.

In their insecticide intoxication study, Magalhães and Caldas [15] evaluated medical records of patients who had suffered insecticide poisoning. These authors found that temephos caused 70 % of intoxication cases, which were mainly due to occupational exposure. In another approach, Benitez-Trinidad et al. [3] studied the in vitro effects of induction of DNA damage by temephos on human lymphocytes, in which they reported a significant increase in genomic lesions with increasing doses (1, 2, 5 and 10 μM). The study by Cobanoglu and Cayir [6], using the same cell type, showed an increase in the frequency of sister chromatid exchange (SCE), which suggests that temephos may have clastogenic effects at concentrations of 50 and 75 µg/mL. In vivo studies were also performed by Aiub et al. [1], who evaluated the genotoxicity of temephos in the peripheral blood of Wistar rats at a concentration of 1.34 mM, which produced 22 % severe genomic lesions and an increase of 48 % at a dose of 21.75 mM. These studies point out dangers of the use of the chemical temephos and emphasize the need for investigations on alternative insecticides, such as DBE, for vector control.

In the present study, only the concentration of 40 mg/kg of DBE showed a significant increase in MN per cell and a significant decrease in the frequency of PCE, in the PCE:NCE ratio, indicating that DBE can be mutagenic and cytotoxic at this concentration, when multiple treatment is used. These data demonstrate the relevance of this study to understand whether, even at lower concentrations, DBE has a genotoxic effect in the treated mice. The above data are also relevant, since DBE has a lower genotoxic profile than temephos.The data in this study reinforce and complement those of Viana Cruz et al. [38] regarding the safety of the application of the semi-synthetic DBE as a larvicide against Ae. aegypti and its effects on non-target organisms.

5. Conclusions

The micronucleus test in the bone marrow of Balb/C mice showed mutagenicity and cytotoxicity at the concentration of 40 mg/kg. In the comet assay in blood that presented negative genotoxicity in the variable Tail Length, Tail DNA and Tail Moment. The analyses showed increased cytogenotoxic effects in Balb/C mice and suggest that DBE may be effective to use as a larvicide in the control of Ae. aegypti in drinking water, both for consumption by humans and by other animals, as well as having a lower genotoxic profile than the synthetic larvicide temephos. In this sense, studies of biochemical, histopathological and pharmacokinetic changes in non-target organisms are necessary in order to confirm the safety of DBE at low concentrations. Furthermore, the presente study about citogenotoxicity, initiate a comprehensive assessment of the ecotoxicity of this substance, considering that there is a proven need to implement new methods to control Ae. aegypti.

Funding

Funding was received from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), INCT-ADAPTA II/INPA, under process number 465540/2014–7; Governo do Estado do Amazonas/SEPLANCTI/FAPEAM/POSGRAD 2021, and FAPEAM (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas), via call 021/2011 (Programa Universal de Amparo à Pesquisa do Amazonas), under process number 1036/2011. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Código de Financiamento 001.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Leonardo Brandão Matos: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology. Junielson Soares da Silva: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Sabrina da Fonseca Meireles: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Plínio Pereira Gomes Júnior: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision. Francisco Celio Maia Chaves: Methodology. Fernanda Guilhon-Simplicio: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology. Míriam Silva Rafael: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Daniel Luís Viana Cruz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ana Cristina da Silva Pinto: Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Wanderli Pedro Tadei (in memoriam) of the Laboratório de Malária e Dengue, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA), Dr. Adalberto Luis Val of the Laboratório de Ecofisiologia e Evolução Molecular at INPA, and Dr. Jacqueline da Silva Batista and Eliana Feldberg of the Programa de Genética, Conservação e Biologia Evolutiva at INPA for the institutional support.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Aiub C.A.F., Coelho E.C.A., Sodré E., Pinto L.F., Felzenszwalb I. Genotoxic evaluation of the organophosphorus pesticide temephos. Genet. Mol. Res. 2002;1(2):159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barros A.M.C., Lima E.S., Pinto A.S.C., Simplicio F.G., Chaves S.C.M., Pereira A.R.M.F. Potential of dilapiol analogues for use in Neglected Diseases, with emphasis on Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: a literature review. Braz. J. Dev. 2021;7(7):73198–73218. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benitez-Trinidad A.B., Herrera-Moreno J.F., Vázquez-Estrada G., Verdín-Betancourt F.A., Sordo M., Ostrosky-Wegman P., Bernal-Hernández Y.Y., Medina-Díaz I.M., Barrón-Vivanco B.S., Robledo-Marenco M.L., et al. Cytostatic and genotoxic effect of temephos in human lymphocytes and HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015;29:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga I.A., Lima J.B.P., Soares S.S., Valle D. Aedes aegypti resistance to temephos during 2001 in several municipalities in the states of Rio de Janeiro, Sergipe, and Alagoas, Brazil. Mem. órias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99(2):199–203. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chediak M.G., Pimenta J.F., Coelho G.E., Braga I.A., Lima J.B.P., Cavalcante K.R.L., Sousa L.C., Melo-Santos M.A.V., Macoris M.L.G., Araújo A.P., et al. Spatial and temporal country-wide survey of temephos resistance in Brazilian populations of Aedes aegypti. Mem. órias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111(5):311–321. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760150409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cobanoglu H., Cayir A. Assessment of the genotoxic potential of temephos. Pestic. i fitomedicina. 2020;35(3):183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cicció J.F., Ballestero C.M. Constituintes voláteis de las hojas e espigas de Piper aduncum (Piperaceae) da Costa Rica. Rev. De. Biol. ía Trop. 1997:783–790. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Sá E.L.R., Rodovalho C.M., de Sousa N.P.R., ILRD S.á, Bellinato D.F., LDS Dias, Hardy A., Benford D., Halldorsson T., Jeger M., Knutsen H.K., More S., Naegeli H., Noteborn H., Ockleford C., et al. Clarification of some aspects related to genotoxicity assessment. EFSA J. 2017;15:12. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domingos P.R.C., Silva Pinto A.C., Santos J.M.M., Rafael M.S. Insecticidal and genotoxic potential of two semi-synthetic derivatives of dillapiole for the control of Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Mutat. Res.: Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014;772:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenech M., Morley A.A. Measurement of micronuclei in lymphocytes. Mutat. Res. /Environ. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1985;147(1-2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(85)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gubler D.J. The global threat of emergent/re-emergent vector-borne diseases. Vector Biology. Ecol. Control. 2010:39–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy A., Benford D., Halldorsson T., Jeger M., Knutsen H.K., Schlatter J. Clarification of some aspects related to genotoxicity assessment. EFSA J. 2017;15(12) doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruskal W.H., Wallis W.A. Use of ranks on one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952;47:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima V.S., Pinto A.C., Rafael M.S. Effect of isodillapiole on the expression of the insecticide resistance genes GSTE7 and CYP6N12 in Aedes aegypti from central Amazonia. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015;14(2):16728–16735. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.11.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magalhães A.F.A., Caldas E.D. Occupational exposure and poisoning by chemical products in the Federal District. Rev. Bras. De. Enferm. 2019;72:32–40. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maia J.G.S., Zohhbi M.D.G.B., Andrade E.H.A., Santos A.S., Silva M.H.L., Luz A.I.R., Bastos C.N. Constituents of the essential oil of Piper aduncum L. growing wild in the Amazon region. Flavour Fragr. J. 1998;13(4):269–272. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manwill P.K., Kalsi M., Wu S., Cheng X., Piermarini P.M., Rakotondraibe H.L. Semi-synthetic cinnamodial analogues: structural insights into the insecticidal and antifeedant activities of drimane sesquiterpenes against the mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins A.J., Lima J.B.P. Evaluation of insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti populations connected by roads and rivers: the case of Tocantins state in Brazil. Mem. órias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2019;114 doi: 10.1590/0074-02760180318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meireles S.F., Domingos P.R.C., Silva Pinto A.C., Rafael M.S. Toxic effect and genotoxicity of the semisynthetic derivatives dillapiole ethyl ether and dillapiole n-butyl ether for control of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Mutat. Res.: Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2016;807:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales D., Ponce P., Cevallos V., Espinosa P., Vaca D., Quezada W. Resistance status of Aedes aegypti to deltamethrin, malathion, and temephos in Ecuador. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2019;35(2):113–122. doi: 10.2987/19-6831.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mughal A., Vikram A., Ramarao P., Jena G.B. Micronucleus and comet assay in the peripheral blood of juvenile rat: establishment of assay feasibility, time of sampling and the induction of DNA damage. Mutat. Res.: Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2010;700(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [webpage on the Internet]. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals: Acute Oral Toxicity – Fixed Dose Procedure. (2001). [updated 2023 Mar 15; cited 2023 Apr 15] Available from: 〈https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/test-no-420-acute-oral-toxicity-fixed-dose-procedure_9789264070943-en#page1〉.

- 23.OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [webpage on the Internet]. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals: In vivo mammalian alkaline comet assay. Test Guideline 489. (2016). [updated 2023 Mar 15; cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: 〈https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/test-no-489-in-vivo-mammalian-alkaline-comet-assay_9789264224179-en〉.

- 24.OECD – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [webpage on the Internet]. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals: Mammalian Erythrocyte Micronucleus Test. Test Guideline 474. (2016). [updated 2023 Mar 15; cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: 〈https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/test-no-474-mammalian-erythrocyte-micronucleus-test_9789264224292-en〉.

- 25.Rafael M.S., Hereira-Rojas W.J., Roper J.J., Nunomura S.M., Tadei W.P. Potential control of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) with Piper aduncum L. (Piperaceae) extracts demonstrated by chromosomal biomarkers and toxic effects on interphase nuclei. Genet. Mol. Res. 2008;7:772–781. doi: 10.4238/vol7-3gmr481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LHFD Santos, PRC Domingos, SDF Meireles, Bridi L.C., ACDS Pinto, Rafael M.S. Genotoxic effects of semi-synthetic isodillapiole on oviposition in Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762) (Diptera: Culicidae) Rev. da Soc. Bras. De. Med. Trop. 2020;53:1–7. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0467-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satoto T.B.T., Satrisno H., Lazuardi L., Diptyanusa A. Insecticide resistance in Aedes aegypti: an impact from human urbanization? PLoS One. 2019;14(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satriawan D.A., Sindjaja W., Richardo T. Toxicity of the organophosphorus pesticide temephos. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019;1(2):62–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmid W. In Chemical mutagens. Springer; Boston, MA: 1976. The micronucleus test for cytogenetic analysis; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seccacini E., Lucia A., Zerba E., Licastro S., Masuh H. Aedes aegypti resistance to temephos in Argentina. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2008;24(4):608–609. doi: 10.2987/5738.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silva J.S., da Silva Pinto A.C., Dos Santos L.H.F., da Silva L.J., da Cruz D.L.V., Rafael M.S. Genotoxic and mutagenic effects of methyl ether dillapiole on the development of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Med. Vet. Entomol. 2021;35(4):556–566. doi: 10.1111/mve.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh N.P., McCoy M.T., Tice R.R., Schneider E.L. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1988;175:184–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tice R.R., Agurell E., Anderson D., Burlinson B., Hartmann A., Kobayashi H., Miyamae Y., Rojas E., Ryu J.-C., Sasaki Y.F. Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2000;35:206–221. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(2000)35:3<206::aid-em8>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tice R.R., Erexson G.L., Hilliard C.J., Huston J.L., Boehm R.M., Gulati D., Shelby M.D. Effect of treatment protocol and sample time on the frequencies of micronucleated polychromatic erythrocytes in mouse bone marrow and peripheral blood. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:313–322. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tice R.R., Erexson G.L., Shelby M.D. The induction of micronucleated polychromatic erythrocytes in mice using single and multiple treatments. Mutat. Res. /Environ. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1990;234:187–193. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(90)90014-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valle D., Belinato T.A., Martins A.J. In: Dengue: teorias e práticas. Valle D., Pimenta D.N., Cunha R.V., editors. Fiocruz; Rio de Janeiro: 2015. Controle químico de Aedes aegypti. Resistência a inseticidas e alternativas; pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valle D., Bellinato D.F., Viana-Medeiros P.F., Lima J.B.P., Martins A.D.J. Resistance to temephos and deltamethrin in Aedes aegypti from Brazil between 1985 and 2017. Mem. órias do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2019;114:1–17. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760180544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viana Cruz D.L., Sumita T.C., Silva Leão Ferreira M., Soares da Silva J., Pinto A.C.D.S., Marques Barcellos J.F., Rafael M.S. Histopathological, cytotoxicological, and genotoxic effects of the semi-synthetic compound dillapiole n-butyl ether in Balb/C mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part A. 2020;83:604–615. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2020.1804026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vikram A., Tripathi D.N., Pawar A.A., Ramarao P., Jena G.B. Pre-bledyoung-rats in genotoxicity testing: a model for peripheral blood micronucleus assay. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008;52:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.