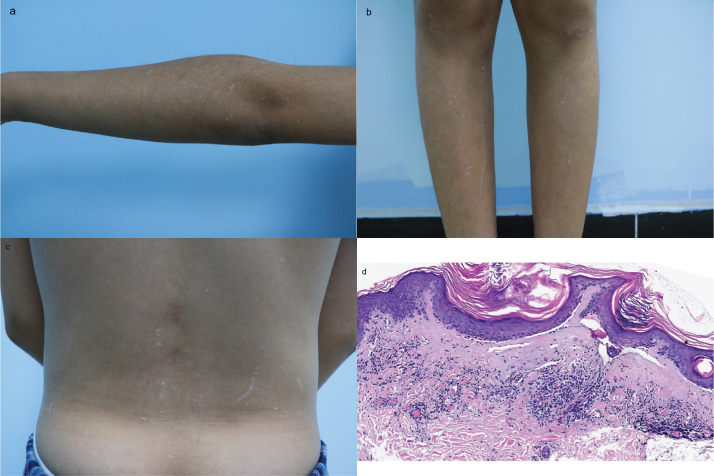

Diagnosis: Generalized lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic mucocutaneous immune-mediated disease that typically involves genital skin (1). Extragenital LS (EGLS) occurs in approximately 15% of patients with LS, and can present in various anatomical areas. Paediatric LS cases represent 5–15% of affected individuals, of which 6% have extragenital manifestations (2). Generalized involvement affecting more than 2 anatomical regions is rare (3). EGLS commonly affects the upper trunk and proximal limbs. The primary lesions begin as asymptomatic to mildly pruritic polygonal white papules, usually on the upper back, chest, abdomen, or neck, which coalesce into well-demarcated erythematous plaques that slowly become atrophic over time, appearing as ivory-white patches with a tendency to scar (4). Köbnerization is very common at extragenital sites, especially at pressure points, old surgical and radiotherapy scars, and trauma sites (5).

Histopathologic features of EGLS include interface dermatitis with epidermal atrophy, orthohyperkeratosis, and follicular plugging (2). The major interventions for EGLS are topical corticosteroids, phototherapy, methotrexate, systemic glucocorticoids, and supportive interventions (1, 6). Disease activity is a critical factor for determining the approach to treatment. Signs of active disease include lesion erythema, new lesions, and expanding lesions. For patients with extensive or spreading active disease, phototherapy or systemic therapy are suggested. For patients with inactive disease, supportive interventions (emollients, wound care for fissures and erosions) rather than anti-inflammatory drugs or phototherapy are suggested. (6). In our case, considering that the lesions are extensive and Köbner phenomenon may indicate active lesions, the patient received a low dose of prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/d) orally. However, there was no improvement after a month’s treatment. We observed that the lesion appeared inactive, as there was no erythema, no formation of new lesions, and no expansion of existing lesions. Consequently, we decided to discontinue systemic therapy and recommended the use of emollients. The patient continues to be monitored through regular follow-up appointments.

REFERENCES

-

1.De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H, Bieber K, Thaçi D, et al. Lichen sclerosus: the 2023 update. Front Med

2023; 10: 1106318. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1106318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

2.Burshtein A, Burshtein J, Rekhtman S. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review of clinical features and treatment. Arch Dermatol Res

2023; 315: 339–346. 10.1007/s00403-022-02397-1

[DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

3.Hong EH, An MK, Cho EB, Park EJ, Kim KJ, Kim KH. A case of generalized lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Ann Dermatol

2020; 32: 327–330. 10.5021/ad.2020.32.4.327

[DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

4.Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review. Aust J Dermatol

2022; 63: 452–462. 10.1111/ajd.13890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

5.Lewis FM, Tatnall FM, Velangi SS, Bunker CB, Kumar A, Brackenbury F, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol

2018; 178: 839–853. 10.1111/bjd.16241

[DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

6.Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: management. In: Callen Jeffrey(ED.), Up To Date 2023; retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus-management?source=history_widget [Google Scholar]