Abstract

Objective:

Substance use disorders (SUD) are frequently comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, but a comprehensive diagnostic assessment is often not clinically feasible. Efficient psychometrically-validated screening tools exist for many commonly comorbid conditions, but cut-off accuracies have typically not been evaluated in addiction treatment settings. This study examined the performance of several widely-used screening measures in relation to diagnostic status from a clinical interview to identify and validate cut-off scores in an inpatient SUD treatment setting.

Method:

Participants were 99 patients in a large residential SUD treatment program in Ontario, Canada. Participants completed a screening battery, including the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 (GAD-7), and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5), and underwent a semi-structured diagnostic clinical interview. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to determine optimal cut-off scores on the screening tool against the interview-based diagnosis.

Results:

Area under the curve (AUC) was statistically significant for all screens and were as follows: PHQ-9 = 0.70 (95% CI = 0.59–0.80), GAD-7 = 0.74 (95% CI = 0.63–0.84), and PCL-5 = 0.79 (95% CI = 0.66–0.91). The optimal accuracy cut-off scores based on sensitivity and specificity were: PHQ-9 ≥16, GAD-7 ≥ 9, the PCL-5 ≥ 42.

Conclusions:

In general, the candidate screeners performed acceptably in this population. However, the optimal cut-off scores were notably higher than existing guidelines for depression and PTSD, potentially due to the general elevations in negative affectivity among individuals initiating SUD treatment. Further validation of these cut-off values is warranted.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Screening, Substance Use Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Measurement-based Care

1. Introduction

Psychoactive substance misuse is a major public health concern, associated with deleterious short- and long-term consequences, and is estimated to affect over 19.7 million Americans (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2018). In fact, substance use costs American society over $740 billion per annum (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). Substance use disorders (SUD) tend to co-occur with other psychiatric conditions, particularly depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Strathdee et al., 2005; Compton et al., 2007; MacKillop et al., 2016). For example, Grant et al. (2004), in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), found that 20% of the general population with a substance use disorder had a comorbid mood disorder, and 18% had an anxiety disorder. Moreover, both the NESARC II and III confirmed high rates of comorbidity in individuals with substance use disorders over time (Grant et al., 2015). Notably, depressive and PTSD symptoms have been found to be associated with higher levels of alcohol motivation, putatively reflecting more potent negative reinforcement as a driver of the comorbidity (Murphy et al., 2013).

Similar patterns are present in clinical settings. In an inpatient addiction population, investigators observed over 60% of patients with SUD had current comorbid psychiatric disorders, with the most commonly occurring disorder being depression (25.8%), and PTSD (14%) (Chen et al., 2011). The risks associated with substance misuse increase substantially when accompanied by a co-occurring psychiatric condition. Such consequences include attenuated physical health, social dysfunction, incarceration, poverty, poor treatment outcomes, and premature mortality (O’Brien et al., 2004; Kessler, 2004; Swedsen & Merikangas, 2000; Draine et al., 2002; Dickey et al., 2002). Moreover, individuals in addiction treatment who have unidentified comorbid conditions are significantly more likely to drop out of treatment, and even when their comorbidities are identified, their symptoms are infrequently addressed (Schulte et al., 2010). The high rates of co-occurring substance and other psychiatric disorders, create manifold challenges in treatment settings for many reasons, including: the acute affects of substance intoxication and withdrawal can mask the symptoms of concurrent comorbidities; there are often insufficient resources and expertise available to manage concurrent disorders; and there can be clinical nihilism, insofar as trying to manage the concurrent disorders simultaneously may be viewed as neither feasible, nor effective (for review see Flynn & Brown, 2008).

Given the high rates of comorbidities, as well as the significant impairments associated with these comorbid conditions, accurate assessment and identification of complex psychiatric presentations is critical in SUD treatment (Rush, 2015). In clinical settings, the gold standard for diagnosing an individual with psychiatric conditions is structured or semi-structured clinical interviews by trained diagnosticians. While these interviews are considered the most clinically accurate, they are typically resource- and time-intensive, and are not feasible in high volume clinical settings (Eack, Singer & Greeno, 2008). As such, screening questionnaires are commonly used as a low-cost, rapid, and relatively low burden strategy to identify individuals who are likely to have a condition. Although these screening questionnaires are not intended to diagnose an individual, when psychometrically sound, they have good psychometric properties, they provide sufficient justification for a patient to be referred for more in-depth and time consuming, but accurate diagnostic assessment (Rush & Castel, 2013). The accuracy of the screening tools themselves depends on the nature of the group being assessed, including their age, ethnicity, and psychiatric condition (Alexander et al., 2008), and the presence of an SUD. In other words, the cut off score on the screening questionnaire varies depending on certain features of the population being sampled, and therefore potentially impacts who will be identified for further assessment.

Although certain widely used screening questionnaires, have been well validated in general psychiatric settings, they have not been well established among people with SUD. In fact, to our knowledge the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 have only been validated once in a SUD population and that was in an outpatient setting (Delgadillo et al., 2011; Delgadillo et al., 2012). Without validation of these screening questionnaires within a SUD treatment population, typical cut off scores for identification may not be as accurate or valid. As such, identifying validated cut off scores for SUD clinical populations is critical for two reasons. First, it is important to examine the psychometric properties of measures in meaningfully distinct populations, such as outpatient psychiatry compared to inpatient addiction treatment, since the results may signal differential need for psychiatric follow-up. Second, the presence of a SUD may result in a higher false positive rate. Specifically, individuals in addiction treatment may have recently experienced a negative life event that precipitated admission to treatment, which may increase general negative affectivity. As such, high negative affectivity resulting from the substance misuse may contribute to false positives from a psychiatric standpoint.

Given these intersecting factors the current study sought to evaluate existing screening measures directly. Specifically, with a sample of patients seeking treatment in an inpatient addiction program, self-report screening measures of depression, anxiety disorders, and PTSD were administered, followed by a structured diagnostic clinical interview that addressed the same domains. Performance on each screen was examined in relation to the gold standard diagnosis to assess the utility of the measure and determine the optimal cut off scores. Although the presence of an SUD was assumed given the clinical setting, a secondary objective of the study was to also examine SUD screening in terms of its accuracy.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

Data were collected from 100 patients, aged 18–65, in the 35-day stream of the addiction medicine services inpatient program at Homewood Health Centre (HHC) located in a large mental health and addiction treatment hospital in Guelph, Ontario. One participant was excluded as they were transferred to a different inpatient unit, and therefore did not complete any screening assessments. The sample was 68% male, with a mean age of 41.7 (SD = 11.39). The most frequently self-reported diagnosis was alcohol use disorder (69%), followed by anxiety disorders (55%). Participant characteristics and prevalence and overlap of diagnoses are presented in Table 1. Figures representing the comorbid psychopathology are in supplemental materials. Participants completed a self-report screening assessment battery upon stabilization, at least two days after admission but within the seven days. This involved completion of screening questionnaires assessing depression, anxiety, PTSD, and SUDs (described below). Subsequently, each participant was administered a semi-structured clinical interview by two doctoral-level interviewers (EL, SS). All diagnostic interviews were audiotaped and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Where discrepancies were present between the interviewer and the reviewer, the final disposition was made by a licensed clinical psychologist (JM). All participants underwent informed consent and all procedures were approved by the Regional Centre for Excellence in Ethics Board (RCEE) at Homewood Health Centre.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics (n= 99)

| Variable | M(SD)/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 41.7 (11.39) | ||

| Sex | 68% male | ||

| Race | 89% white | ||

|

| |||

| Screening Tools (M(SD)) | Total | Female (n = 31) | Male (n = 68) |

|

| |||

| PCL-5 | 32.60 (18.97) | 39.13 (16.37) | 29.62 (19.43) |

| PHQ-9 | 14.73 (6.35) | 15.58 (5.37) | 14.34 (6.75) |

| GAD-7 | 11.22 (5.99) | 12.91 (5.41) | 10.43 (6.10) |

| Alcohol Sx | 5.41 (4.08) | 6.74 (4.01) | 4.81 (3.97) |

| Cocaine Sx | 3.15 (4.54) | 2.68 (4.47) | 3.37 (4.60) |

| Opioids Sx | 1.40 (3.26) | 0.97 (2.56) | 1.43 (2.52) |

| Cannabis Sx | 1.30 (2.49) | 1.03 (2.44) | 1.60 (3.53) |

|

| |||

| DART Diagnostic Status (%positive (n)) | Total | Female (n = 31) | Male (n = 68) |

|

| |||

| PTSD | 16.2 (16) | 19.4 (6) | 14.7 (10) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 29.3 (29) | 35.5 (11) | 26.5 (18) |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 37.4 (27) | 41.9 (13) | 35.3 (24) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 69.7 (69) | 74.3 (23) | 67.6 (46) |

| Cocaine Use Disorder | 33.3 (33) | 32.3 (10) | 33.8 (23) |

| Opioid Use Disorder | 13.1 (13) | 9.7 (3) | 14.7 (10) |

| Cannabis Use Disorder | 19.2 (19) | 12.9 (4) | 22.1 (15) |

| Any Substance Use Disorder | 57.6 (57) | 41.9 (16) | 51.5 (41) |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities (%positive (n)) | Total | Female (n = 31) | Male (n = 68) |

|

| |||

| AUD + any non addiction comorbidity | 45.5 (45) | 58.1 (18) | 39.7 (27) |

| SUD + any non addiction comorbidity | 44.4 (44) | 45.2 (14) | 44.1 (30) |

Note: PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Checklist-5; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5; Sx = symptoms; AUD: Alcohol Use Disorder; SUD: Substance use Disorder; DART: Diagnostic Assessment for Research and Treatment

2.2. Measures

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Spitzer et al., 1999):

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report measure that has been rigorously validated as a measure of depressive symptoms.

Symptoms are evaluated as to whether or not they occurred over the past two weeks. The PHQ-9 demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .87). The validated cut off score for this screening instrument in non-clinical settings is a score of 10 or above (Kocalevent et al., 2013).

2.3. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006)

The GAD-7 is a seven-item self-report scale assessing anxiety symptoms. Symptoms are evaluated as to whether or not they occurred over the past two weeks. The GAD-7 demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .92). The validated cut off score for this screening instrument in nonclinical settings is 10 or above (Löwe et al., 2008)

2.4. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure assessing PTSD symptom severity. Symptoms are evaluated over in the two weeks prior to admission to HHC. The PCL-5 as a whole demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .83), and each subscale exhibited good to excellent internal consistency (α’s = .81 −.91). The validated cut off score in non-clinical settings for this screening instrument is a score of 31 or above (Bovin et al., 2016). However, the established cut off score used at HHC is 38 or above.

2.5. ICD-10 Symptom Checklist for Mental Disorders - Psychoactive Substance Use Syndromes Module (World Health Organization, 2004).

This checklist assesses self-reported SUD symptoms using the dependence items from ICD 10, but was augmented with additional items to capture all SUD symptoms in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Responses range from 0–11 (the DSM-5 maximum), with dichotomous response options as either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Substances include: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, other stimulants, heroin, other opioids, hallucinogens, inhalants, sedatives, prescription sleep aids, and other substances not listed. Other opioids and heroin were grouped together. Low frequency substances (<6% of participants) were excluded (i.e. stimulants, hallucinogens, inhalants, sedatives, and prescription sleep aids). Internal consistency was good to excellent across substances (α’s = .87 −.92).

2.6. Diagnostic Assessment Research Tool (DART; McCabe et al., 2017):

The DART is an open-source semi-structured diagnostic interview with a modular design to assess wide range of mental disorders based on the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Each module consists of mandatory criterion-based questions as well as optional clarifying questions to ensure diagnostic accuracy. This study included the following modules: alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, gambling use disorder, major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder, PTSD, acute stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. For the purposes of this analysis, anyone who met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and/or social anxiety disorder and/or panic disorder were considered to have an anxiety disorder.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

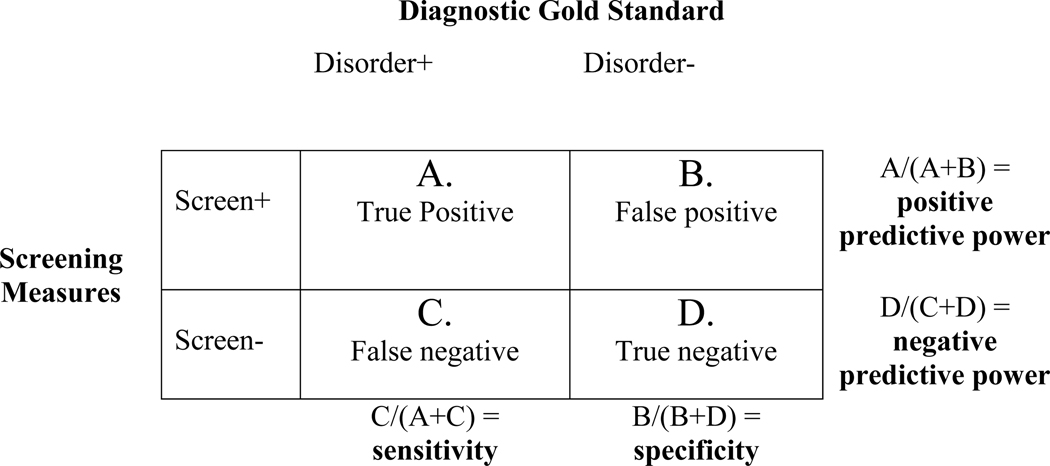

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to examine the capacity of a cut-off on the screening tool to predict the DART diagnosis (e.g., Goodie et al., 2013). An ROC curve is a test designed to assess the true positive rate over the false positive rate measured at every cut off value. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) (i.e., the overall accuracy of the test performance) was calculated, with possible ranges between 0.5 for an index of a test with no discriminatory capability, to 1.0 for a test that is perfectly accurate. Asymptotic significance and confidence intervals are also reported. To determine the optimal cut off point, the Youden index method (Youden, 1950) was employed, whereby sensitivity (i.e., proportion classified as positive on the self-report instrument l who actually have the diagnosis by interview, or true positive rate) and specificity (i.e., proportion classified as negative on the self-report instrument who do not have the diagnosis by interview, or the true negative rate) were calculated for all points for each disorder, and the cut point was determined where the sum of sensitivity and specificity was optimal. Using the optimal cut off score determined by the Youden index method, positive predictive power (i.e., probability an individual truly has the disorder when the screening measure is above a given cut point) and negative predictive power (i.e., probability an individual truly does not have the disorder when the screening measure is at or below a given cut point) were calculated (Figure 1 describes how sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive powers were calculated). In addition, sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative powers of the previously published validated cut off scores were compared to those derived from this study. Finally, κ statistics of different cut off scores were calculated to determine the level of concordance between the screening tools and the diagnostic interview. Values between 0.21–0.4 reflect fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 reflect moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 reflect substantial agreement, and .81–1.00 reflect almost perfect agreement (Cohen, 1960).

Figure 1:

Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive power and negative predictive power.

3. Results

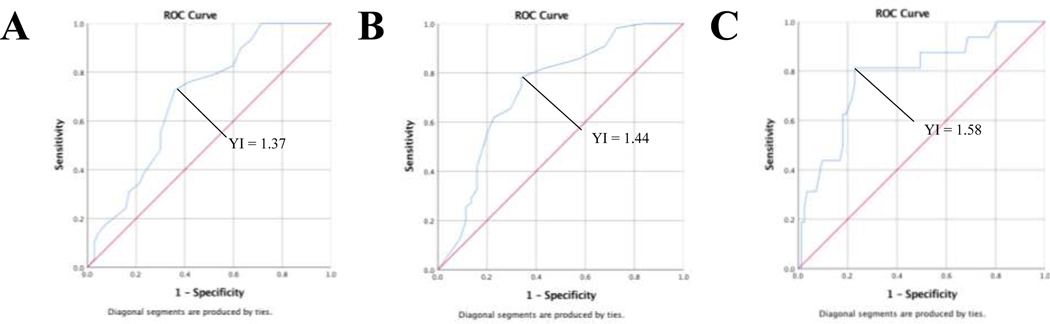

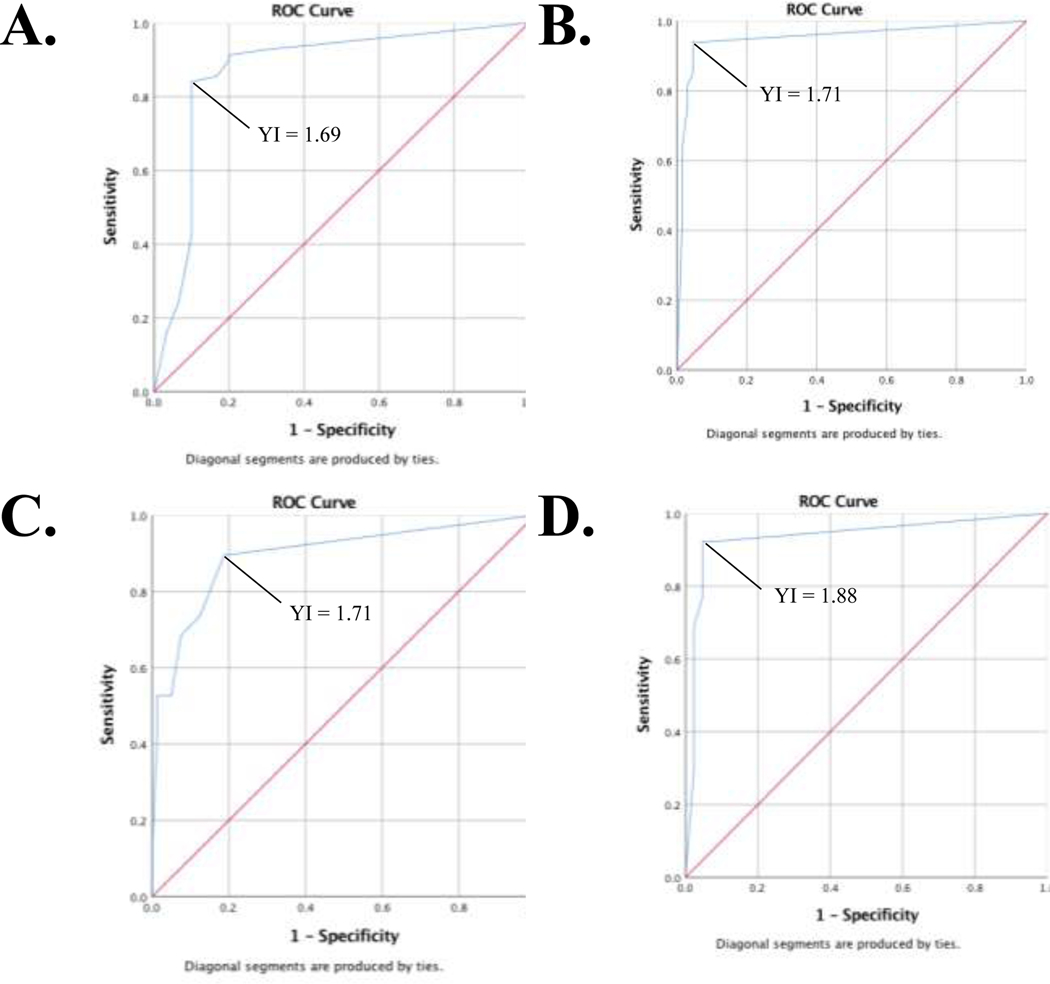

Table 2 presents AUCs, standard errors, and asymptotic statistical significance for all screens. The AUCs suggest that all measures performed significantly better than chance, discerning between participants with and without the disorders. For MDD, anxiety disorders, and PTSD the accuracy was fair. Table 3 lists the optimal cut-off scores for each individual based on the Youden index. The cut off scores from this study were compared to the validated cut off scores obtained in studies in general psychiatric populations for each screening measure in the literature.

Table 2:

Receiver operating curve area under the curve analyses

| Measure | Area | SE | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.002 | [0.59, 0.80] |

| GAD-7 | 0.74 | 0.05 | <0.001 | [0.63, 0.84] |

| PCL-5 | 0.79 | 0.06 | <0.001 | [0.66, 0.91] |

| Alcohol Sx checklist | 0.87 | 0.05 | <0.001 | [0.78, 0.96] |

| Cocaine Sx checklist | 0.95 | 0.03 | <0.001 | [0.90, 1.00] |

| Opioids Sx checklist | 0.94 | 0.05 | <0.001 | [0.85, 1.00] |

| Cannabis Sx checklist | 0.89 | 0.05 | <0.001 | [0.80, 0.99] |

Note: PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Checklist-5; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5; Sx = symptoms

Table 3:

ROC curve optimal cut off score for sensitivity and specificity based on the Youden index

| Measure | Validated cut off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive | Negative Predictive | Validated κ | Optimal Cut off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive | Negative Predictive | Optimal κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 (GP) | ≥10 | 1.000 | 0.29 | 37% | 100% | 0.19 | ≥16 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 46% | 85% | 0.31 |

| GAD-7 | ≥10 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 73% | 67% | 0.41 | ≥9 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 74% | 66% | 0.44 |

| PCL-5 | ≥31 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 24% | 93% | 0.22 | ≥42 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 41% | 96% | 0.42 |

| Alcohol Sx | ≥2 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 91% | 80% | 0.71 | ≥4 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 92% | 71% | 0.70 |

| Cocaine Sx | ≥2 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 94% | 71% | 0.65 | ≥2 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 94% | 71% | 0.65 |

| Opioids Sx | ≥2 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 100% | 88% | 0.89 | ≥3 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 99% | 75% | 0.89 |

| Cannabis Sx | ≥2 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 93% | 54% | 0.50 | ≥1 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 89% | 71% | 0.50 |

Note: PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GP: General Psychiatry; OS: Outpatient Substance Use; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Checklist-5; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5

For the PHQ-9, an additional cut off score was calculated to reflect the value obtained in the Delgadillo et al. (2011) study, examining outpatients with substance use disorder. For the GAD-7, a cut off score for the SUD specific population in Delgadillo et al., (2012) was not calculated, as the cut off score was the same score validated in general psychiatry. Of note, depression and PTSD were substantially higher using both the established cut off scores and the substance use specific cut off scores. For the PHQ-9, a cut-off of 16 yielded the optimal accuracy, correctly identifying 72% of individuals with MDD and correctly identifying 64% of individuals without MDD. In contrast, the previously validated score of 10 would over-identify individuals with MDD.

For the PCL-5, a cut-off of 42 would correctly identify 81% of individuals with PTSD and correctly identify 77% of individuals without PTSD. Again, the previously validated cut-off of 31 would over-identify individuals, with specificity of 51%. Figure 2 presents the ROC curves for each diagnosis. As expected, accuracy ranged from good to excellent for SUDs and Figure 3 presents the ROC curves for each SUD diagnosis. See supplementary materials for a complete list of all cut-off scores and associated sensitivity and specificity values.

Figure 2:

ROC curves for non-SUD psychiatric screeners compared to the criterion of diagnostic status. Panel A is the PHQ-9; Panel B is the GAD-7; and Panel C is the PCL-5.

Figure 3:

ROC Curve for SUD screeners compared to the criterion of diagnostic status. Panel A is alcohol use disorder; Panel B is cocaine use disorder; Panel C is cannabis use disorder; Panel D is opioid use disorder.

Positive and negative predictive power using these cut off scores are also presented in Table 3. Both the depression and PTSD screens had positive predictive powers below 50%, meaning that fewer than half who screened positive were actually determined to meet diagnosis. However, the depression and PTSD screens had negative predictive powers above 80%, meaning four out of five who screened negative were indeed negative for the disorders. In addition, Table 3 shows the positive and negative predictive capacities for the validated cut off scores, with proportions either at or substantially below the predictive capacities of the optimal cut off scores for this sample. As expected, the screens for SUD had stronger predictive power, with positive predictive powers between 89–100%, and negative predictive powers between 71–88%.

Table 3 presents the κ values for both the optimal cut off scores and the established cut off scores. For the current study, the Kappa values indicate that there was fair agreement between the PHQ-9 and a diagnosis of MDD; moderate agreement between the GAD-7, PCL-5, and Cannabis Symptom Checklist, and a diagnosis of anxiety, PTSD, and cannabis use disorder, respectively; and substantial agreement to almost perfect agreement between alcohol use, cocaine use, and opioid use symptom checklists, and their corresponding diagnoses. The κ values calculated for the validated cut off values were lower than or equal to those calculated using the optimal cut off score for the PHQ-9, and PCL-5, slightly lower for the GAD-7, and almost identical for the substance use checklists.

4. Discussion

This study found that existing psychiatric screening instruments performed relatively well overall when used with individuals seeking inpatient treatment for SUD; however, their cut points may require adjustment to optimize their utility among this population. Specifically, the previously psychometrically validated cut-off scores, which have been rarely examined in an addiction population, appeared universally too low. For example, based on the optimal cut-offs in this sample, the PHQ-9 demonstrated good sensitivity and adequate specificity, and the PCL-5 demonstrated good sensitivity and excellent specificity, suggesting the cut-off scores generated in this sample are substantively accurate. However, the optimal cut-off scores were considerably higher than the validated cut off scores, with the PHQ-9 being five points higher and the PCL-5, ten points higher. Although used as a secondary indicator, the overall patterns were further supported by the κ statistics, where the PHQ-9 and PCL-5 were substantively higher using the optimal cut off scores compared to the validated cut off scores. Similar findings were presented in Castel, Rush and Scalco (2008), who observed the need to raise the cut off scores for screening PTSD and depression in an SUD population compared to other clinical samples.

Additionally, in the current study, when the previously validated cut-off score for the PHQ-9 was applied in this sample, sensitivity increased to 100%, but specificity decreased to 29%. Similarly, when using the cut off scores obtained by Delgadillo et al. (2011) with SUD outpatients, sensitivity was 90%, and specificity was 37%. In other words, the established cut off scores for the PHQ-9 over-identified patients as being MDD+. For the PCL-5, the situation was somewhat different, insofar as sensitivity did not increase with a higher cut-off, but correct identification of individuals who truly did not have the disorder improved.

The GAD-7 in this study had an optimal cut off score of 10 or greater, similar to the previously validated cut-off of nine and above in general psychiatry (Löwe et al., 2008) and nine and above in a substance use disorder specific population (Delgadillo et al., 2012). This screening tool demonstrated good specificity (78%), suggesting it performed well in correctly classifying patients who did not meet criteria for an anxiety disorder. However, similar to the PHQ-9, sensitivity was adequate but suboptimal (66%), suggesting it only correctly identified two-thirds of those who were subsequently determined to have an anxiety disorder. One explanation for this finding is that individuals entering an addiction treatment program typically have increased distress and disturbance as a result of the acute effects of substance use. In other words, the experience of generally elevated negative affectivity associated with treatment admission may act as a phenotype for depressive and anxiety-like symptoms, leading to increased false positives in a SUD population. Interestingly, the validated cut-off scores for the GAD-7 preformed almost identically to the cut-off scores obtained in this sample, suggesting it may be a problem with the screening measure itself in assessing anxiety disorders in this population. As the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were developed for use in general practice, it may be warranted to develop alternative screening measures for this population. For example, specific wording that assesses whether symptoms are a direct consequence of substance use may help to improve screening accuracy. On the other hand, using established measures in widespread use offers greater comparability and extant insights into the psychometric properties of these tools.

While these screening measures functioned well in general, they did not offer sufficient accuracy to serve in a diagnostic capacity. This is reflected in the fact that the positive predictive powers were generally low in this sample. For depression and PTSD, while negative predictive powers were excellent, positive predictive powers were poor, indicating that the screens tended to miss over half of those screening positive. The positive predictive power for anxiety was slightly better, capturing three-quarters of individuals who actually had the diagnosis. Negative predictive power for anxiety disorders, however, tended to only capture two-thirds of individuals who did not have the diagnosis. While positive and negative predictive powers are generally poor, these instruments are highly dependent on prevalence rates in the population, and thus subject to change in different settings. It is therefore more important for these screens to have the best balance of sensitivity and specificity.

With regards to the secondary focus, the SUD screening instruments, the cut-off scores were at or around the validated cut-off scores, and had good to excellent sensitivity (86–92%) and specificity (80–95%). These results are not surprising, given this is a SUD population, and these scales were developed to screen in this population. However, they provide confirmatory evidence that efficient, low-burden screening measures do indeed accurately classify individuals diagnostically. As individuals with SUD are typically poly-substance users, these screenings tools can help to identity a more fulsome clinical picture. Moreover, without identifying the multifarious patterns of SUD that may be present, treatment itself may be undermined by focusing on the most problematic SUD, and therefore overlooking concurrent SUDs (e.g., focusing on OUD, but overlooking CUD).

These findings should be considered in the context of the study’s strengths and limitations. Strengths include an ecologically valid sample of treatment-seeking patients in a private (insurance-funded) inpatient addiction treatment program. As such, it was highly representative of the kind of settings that are both commonplace across North America and presumably use (or would benefit from) screening measures to inform diagnosis and treatment planning. In addition, the study did not just focus on one comorbidity but included three of the most common comorbid conditions: depression, anxiety disorders, and PTSD.

With regard to limitations, it is important to consider that the sample size was modest, reducing statistical power and reducing the representativeness of the sample. However, the prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in this sample were similar to those obtained in other studies (for a meta-analysis, see Lai et al., 2015), somewhat mitigating this concern. In addition, the current sample size is not substantially below typical sample sizes for developing ranges for laboratory tests (Manrai, Patel, & Ioannidis, 2018). Nonetheless, the results should not be considered definitive, particularly in terms of the specific cut-off scores. Rather, these cut-offs offer an empirically based alternative to existing cut-offs and a clear hypothesis for evaluation in future studies with larger samples. Second, although this study may be representative of inpatient addiction services, they are not necessarily representative of public inpatient SUD treatment programs or lower acuity settings, such as outpatient SUD treatment clinics or general psychiatry programs. Consequently, these results may not generalize across all addiction clinical settings. Third, the GAD-7 is a global screen for anxiety disorders, and therefore does not reflect individual categories within anxiety disorders (e.g. social anxiety, generalized anxiety, and panic disorder). Given the high rates of anxiety disorders in this population, it may be pertinent to assess the cut off scores for separate measures of other anxiety disorders. Furthermore, it is certainly the case that other disorders outside the scope of this study are also comorbid with SUDs (e.g., borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder) and could not be addressed. Fourth, while the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and PCL-5 are widely used and established screening tools, it is possible there are other better performing screening tests (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory) that are more appropriate for this population. As such, future studies may need to address this issue further.

It may be important to consider the broader implications for inpatients undergoing treatment for SUD in light of these findings. Fully 66% of patients met criteria for at least one target non-SUD condition in this sample, with the most common comorbidity being anxiety disorders (i.e. GAD and/or SAD). This is a conservative estimate as it only accounts for the commonly comorbid disorders that were prioritized and assessed in this study. Thus, the overall prevalence rates of comorbid conditions indicate that even SUD treatment services that are not deliberately providing services targeting patients with SUDs and other psychiatric comorbidities (populations typically referred to as concurrent disorders or dual diagnosis patients) are in fact typically doing so. In other words, the high rates of comorbidity between SUD and other conditions, in general and probably even more so in high severity clinical settings, make inpatient SUD treatment de facto concurrent disorders programs, regardless of whether they are designed as such. In turn, clinicians working in addictions may fundamentally need to be trained to address concurrent disorders. For some time there has been a recognition that these comorbidities reflect a particularly pernicious negative reinforcement cycle of ‘self-medication’ (DuPont & Gold, 2007) and, fortunately, clinical protocols for treating substance use disorders and common comorbidities are increasingly available (Flanagan et al., 2016; Iqbal et al., 2019). Consistent with these trends, this study clearly supports calls for a more integrated treatment system, where programs are focussed on SUD and co-occurring conditions, and clinicians are cross-trained on management of concurrent disorders (McGovern et al., 2014; Drake et al., 2010).

Taken together, these results offer evidence that existing screening tools appear to operate adequately in an inpatient SUD treatment setting, but particularly emphasize the need for their optimization. Both the PHQ-9 and PCL-5 in this study had substantially higher cut off scores and, as depression and PTSD are commonly comorbid with substance use, it is critical to establish valid screening values to correctly identify the need for more in depth diagnostic assessment and also guide treatment planning. Further investigation is warranted to determine whether these cut-off scores are viable for widespread implementation in addiction clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE.

This study provides preliminary modified screening cut-off scores for major depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in addiction treatment settings.

Highlights.

Widely-used psychiatric screens functioned adequately in an inpatient addiction treatment setting

Accuracy of screening was increased by increasing the cut-off score for a depression screen, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Accuracy was also increased by increasing the cut-off score for a post-traumatic stress disorder screen, the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

Acknowledgments:

The authors are grateful for the research support of Ms. Alyna Walji, Ms. Heather Millman, Mr. Dezi Ahuja, Dr. Andrea Brown, and Ms. Heather Froome.

Footnotes

Author CRediT statement

Emily Levitt – Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration; Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing; Sabrina Syan - Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration; Writing - Review & Editing; Sarah Sousa - Project administration; Writing - Review & Editing; Jean Costello - Writing - Review & Editing; Brian Rush - Writing - Review & Editing; Andriy Samokhvalov - Writing - Review & Editing; Randi McCabe - Writing - Review & Editing; John Kelly - Writing - Review & Editing; James MacKillop - Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. James MacKillop is a Senior Scientist in BEAM Diagnostics, Inc. No BEAM products were used in the research reported. No other authors have potential conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alexander MJ, Haugland G, Lin SP, Bertollo DN, & McCorry FA (2008). Mental health screening in addiction, corrections and social service settings: Validating the MMS. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(1), 105–119 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel S, Rush B, & Scalco M.(2008). Screening of mental disorders among clients with addictions. The need for population-specific validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 6(1), 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, & Lejuez CW (2011). An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J.(1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, & Grant BF (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo J, Payne S, Gilbody S, Godfrey C, Gore S, Jessop D, & Dale V.(2012). Brief case finding tools for anxiety disorders: Validation of GAD-7 and GAD-2 in addictions treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125(1–2), 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo J, Payne S, Gilbody S, Godfrey C, Gore S, Jessop D, & Dale V.(2011). How reliable is depression screening in alcohol and drug users? A validation of brief and ultra-brief questionnaires. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1–3), 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Normand SLT, Weiss RD, Drake RE, & Azeni H.(2002). Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 53(7), 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, & Hadley TR (2002). Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 53(5), 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, & Bond GR (2010). Implementing integrated mental health and substance abuse services. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 6(3–4), 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- DuPont RL, & Gold MS (2007). Comorbidity and “self-medication”. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 26(S1), 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Singer JB, & Greeno CG (2008). Screening for anxiety and depression in community mental health: the beck anxiety and depression inventories. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(6), 465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC, Korte KJ, Killeen TK, & Back SE (2016). Concurrent treatment of substance use and PTSD. Current psychiatry reports, 18(8), 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, & Brown BS (2008). Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: Issues and prospects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(1), 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodie AS, MacKillop J, Miller JD, Fortune EE, Maples J, Lance CE, & Campbell WK (2013). Evaluating the South Oaks Gambling Screen with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: Results from a diverse community sample of gamblers. Assessment, 20(5), 523–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, ... & Hasin DS (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA psychiatry, 73(1), 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal MN, Levin CJ, & Levin FR (2019). Treatment for substance use disorder with co-occurring mental illness. FOCUS, A Journal of the American Psychiatric Association, 17(2), 88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2004). The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, & Brähler E.(2013). Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(5), 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai HMX, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, & Hunt GE (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, & Herzberg PY (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Woo W, Ryan C, Sousa S, Romano I, Ropp C, ... & Vedelago H (2016). Concurrent substance use disorders and PTSD in an inpatient addiction treatment program in Canada. Canadian Journal of Addiction, 7(4), 33. [Google Scholar]

- Manrai AK, Patel CJ, & Ioannidis JP (2018). Using Big Data to Determine Reference Values for Laboratory Tests—Reply. Jama, 320(14), 1496–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe RE, Milosevic I, Rowa K, Shnaider P, Pawluk EJ, Antony MM & the DART Working Group. (2017). Diagnostic Assessment Research Tool (DART). Hamilton, ON: St. Joseph’s Healthcare/McMaster University. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Gotham HJ, Claus RE, & Xie H.(2014). Dual diagnosis capability in mental health and addiction treatment services: an assessment of programs across multiple state systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG et al. (2013). Symptoms of Depression and PTSD are Associated with Elevated Alcohol Demand. Drug & Alcohol Dependence [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Trends & Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statisticson2020, April 17 [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Charney DS, Lewis L, Cornish JW, Post RM, Woody GE, ... & Calabrese JR. (2004). Priority actions to improve the care of persons with co-occurring substance abuse and other mental disorders: a call to action. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 703–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush BR (2015). Addiction assessment and treatment planning in developing countries. In el-Guebaly N, Carrà G, Galanter M (Eds). Textbook of Addiction Treatment: International Perspectives. Springer Milan Heidelberg; New York Dordrecht London. 1257–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Rush B, Castel S, Brands B, Toneatto T, & Veldhuizen S.(2013). Validation and comparison of diagnostic accuracy of four screening tools for mental disorders in people seeking treatment for substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(4), 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte SJ, Meier PS, Stirling J, & Berry M.(2010). Unrecognised dual diagnosis–a risk factor for dropout of addiction treatment. Mental Health and Substance Use: Dual Diagnosis, 3(2), 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, & Williams JB (1999). Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(18), 1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Löwe B.(2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee G, Manning V, Best DW, Keaney F, Bhui K, Witton J, ... & Piek C. (2005). Dual diagnosis in a Primary Care Group (PCG),(100,000 population locality): a step-by-step epidemiological needs assessment and design of a training and service response model. Drugs, 12(Supp 1), 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, & Merikangas KR (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW (2013, November). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric analysis. In 29th annual meeting of the international society for traumatic stress studies, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2004). International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems (The) ICD-10. World Health Organization. Youden, W. J. (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3(1), 32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.