Abstract

In recent years, ultrasound has emerged as a widely used technology for modifying proteins/peptides. In this study, we focused on the intrinsic mechanism of ultrasound-induced modification of bovine liver peptides, which were treated with ultrasound power of 0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 W, and their physicochemical and functional properties, as well as ultrastructures, were investigated. The results show that ultrasound mainly affects hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions to change the conformation of proteins and unfolds proteins through a cavitation effect, leading to an increase in biological activity. Fourier infrared spectroscopy showed that ultrasound inhibited the formation of hydrogen bonds and reduced intermolecular cross-linking. Molecular weight distribution showed that the antioxidant components of bovine liver polypeptides were mainly concentrated in fractions of 500–1,000 Da. Maximum values of ABTS (82.66 %), DPPH (76.02 %), chelated iron (62.18 %), and reducing power (1.2447) were obtained by treating bovine liver polypeptides with 500 W ultrasound. Combined with the scanning electron microscopy results, with the intervention of ultrasound, the impact force generated by ultrasonication may lead to the loosening of the protein structure, which further promotes the release of antioxidant peptides, and these findings provide new insights into the application of ultrasound in the release of antioxidant peptides from bovine liver.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Bovine liver hydrolysates, Modification, Antioxidant peptides, Ultrastructure

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of population and relative shortage of food resources, making full use of food resources has become an important issue for human beings. The liver, an important organ for storing nutrients in the animal body, is a high-quality animal by-product resource, its rich protein content makes the investigation of its physicochemical properties and processing mechanisms of great interest [1]. Therefore, development of value-added products from animal liver is currently an effective way to address its limited resource use.

Currently, the development and research on the liver are mainly based on the processed products of pig liver, chicken liver, duck liver, and goose liver [2], [3], in addition, the research on liver protein mainly focuses on the extraction of bioactive substances from liver protein as raw materials [4]. In terms of existing applications, some scholars combine the hydrolysis of poultry liver proteins with the Maillard reaction to generate products with unique colors and flavors, which are applied to feed or pet food enticing agents [5] and porcine liver protein hydrolysate as an alternative source of feed protein for Pacific white shrimp [6]. In terms of potential applications, liver proteins can also be used as a source of naturally occurring animal-derived protease extracts, that exhibit highly efficient enzyme performance, helping to their application in the dairy industry and anti-inflammatory adjuvant therapy [7], [8]. However, the development of antioxidant peptides from bovine liver and how to efficiently improve their bioactivity have not been reported in detail. Regarding food-derived antioxidant peptides, most of them are derived from animals, plant proteins, and microorganisms, with animal-derived antioxidant peptides dominating the market [9]. Recovered hydrolysates such as housefly larval proteins [10]and porcine hemoglobin [11], porcine liver proteins [12], etc., have been reported to exhibit a variety of physicochemical and biological properties, such as antioxidant and metal chelating characteristics. Therefore, the extraction of food-borne antioxidant peptides from bovine liver provides a good inspiration for the sustainable use and development of liver resources.

Protein hydrolysates are obtained by protease hydrolysis, resulting in hydrolysis products with a large number of exposed hydrolysis sites, which can alter their physicochemical properties and enhance their biological activity without affecting their nutritional value [13]. However, since protein hydrolysates treated with a single enzyme have low functional and antioxidant properties, as a result, some studies have focused on seeking means such as adjuncts or combinations to achieve improved action. [14]. Among them, ultrasonic is a new green processing technology that is considered safe and non-toxic. Ultrasound can generate strong shear and mechanical forces due to thermal and cavitation effects, which can alter hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions as well as the molecular structure of proteins, thus improving the physicochemical and functional properties of proteins and peptides, etc [15]. Several studies related to ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis have been conducted. For example, Ultrasound-assisted pretreatment enhances the activity of bovine hide gelatin hydrolysate against ABTS radicals, DPPH radicals, ferrous chelation, and iron reduction [16]. Studies on ultrasonic modification of liver proteins have focused on the functional properties of chicken liver proteins modified by low-frequency ultrasonic waves such as rheological and emulsification properties [17], enhancement of antimicrobial properties [18], and improvement of volatile flavor substances in duck liver [19]. However, studies on the ultrasonic modification of bovine liver peptides with different powers have not been reported yet.

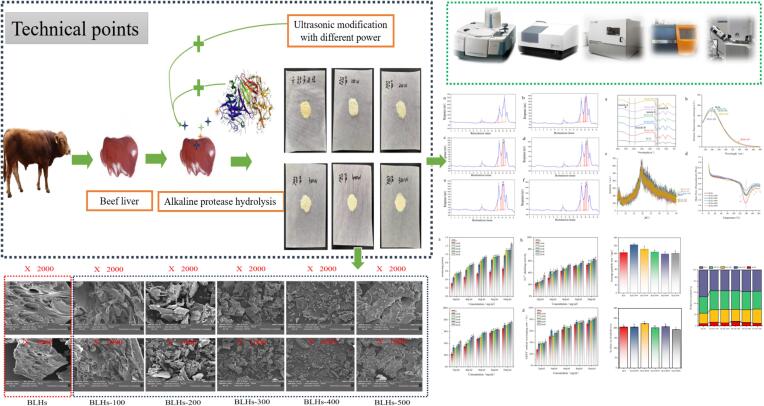

This study aimed to investigate the effects of different ultrasonic powers (0, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 W) on the physicochemical properties, ultrastructure, and antioxidant activity of bovine liver hydrolysates (Flow chart of the experiment shown in Fig. 1), to provide a theoretical basis for the application of bovine liver hydrolysate as an antioxidant active ingredient in the food industry.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of ultrasound-modified bovine liver peptide and overall experiments involving evaluation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Fresh bovine liver was purchased from Lanzhou City, Gansu Province. Preliminary treatment of bovine liver to remove visible connective tissue such as blood vessels, bile ducts, and fat. Store at −18 °C. Alkaline protease (200 U/g) was purchased from Shanghai Yuan Ye Biotechnology Co. Reagents were purchased from Beijing Sorabio Technology Co.

2.2. Preparation of bovine liver hydrolysates (BLHs)

Prepared using a modified method described in Refs [20]. The bovine liver was homogenized, Adjusted pH to 8, the alkaline protease addition was 0.4 %, and digestion was carried out for 4 h at a constant temperature of 50 °C. After enzymatic digestion, the dispersion was heated to 95 °C for 10 min, cooled, and centrifuged at 5,000 g (4 °C), and the supernatant obtained was freeze-dried to obtain the bovine liver hydrolysate.

2.3. Ultrasonic modification treatment

BLHs treated by ultrasonication were modified [5]. A 2 % solution of BLHs was taken and sonicated with a 2.0 cm flat-tip probe using 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 W for 20 min, 3 s of sonication, and 2 s of resting, and then the dispersions were treated with five different output powers were freeze-dried. The treated groups were BLHs-100, BLHs-200, BLHs-300, BLHs-400, BLHs-500, and BLHs without sonication was the control group.

2.4. Molecular weight distribution

Minor modifications based on previous research [21]. Determination of the molecular weight of bovine liver hydrolysate using an Agilent 1260 series high-performance liquid chromatography instrument, the detector is Agilent RID G1362A, and the chromatographic column parameters and conditions are Waters Ultrahydrogel, 300 × 7.8 mm, 500–250-120 A; Mobile phase: 0.1 mol/L NaNO3 aqueous solution; Flow rate: 1 mL/min; Temperature: 40 °C; Standard: PEG.

2.5. Fourier transform infrared spectral scanning

An appropriate amount of lyophilized sample was placed on a Spectrum Two FTIR spectrometer for scanning.

2.6. Fluorescence spectrum

Fluorescence intensity was monitored using a fluorescence spectrometer (F-7000 FL 220–240 V) on bovine liver hydrolyzed proteins treated with different ultrasound powers. The excitation and emission slits were each 5 nm wide and emission spectra were collected at specific wavelengths [22].

2.7. X-ray diffraction (XRD) assay

The XRD patterns of the BLHs and BLHs-100, BLHs-200, BLHs-300, BLHs-400, and BLHs-500 were determined with a powder X-ray diffractometer. Patterns were obtained in the 2θ region from 5° to 40° at a scanning rate of 4°/min [23].

2.8. Thermodynamic properties

Lyophilized BLHs (2–5 mg) was placed in an aluminum crucible under flowing oxygen. The thermal stability of the samples was determined by differential scanning calorimetry [24].

2.9. Surface hydrophobicity

Fluorescence intensity was measured at specific wavelengths by adding 50 µL of 8 mmol/L ANS to each of the different concentrations of sample dilutions (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL (10 mL)). The initial slope is obtained through linear regression analysis and used as an indicator of surface hydrophobicity.

2.10. Particle size

Measured on the laser particle size instrument Bettersize2000 at 25 °C. Before measurement, dilute the sample with PBS buffer (pH 7.0) at 1 mg/ml (w/v).

2.11. DPPH scavenging activity

Referring to previous studies and making some modifications (Jiang et al.,2016), 0.5 ml of diluted sample was mixed with 3.5 ml of DPPH solution (0.1 mmol/l), and the absorbance value was measured at 517 nm.

| (1) |

where Ai: sample solution + DPPH solution; Aj: sample solution + 95 % ethanol; Ac: 95 % ethanol + DPPH solution.

2.12. ABTS scavenging activity

The ABTS analysis was conducted as described by Jamroz ´et al[25]. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm after adding 4 ml ABTS+solution to 40 μl of sample solution for 30 min(A1).

| (2) |

where A0 is the absorbance of PBS instead of the BLHs and SBLHs.

2.13. Reducing force

The reducing power of BLHs was determined by the literature method [14].

2.14. Metal chelating activity

The diluted sample was thoroughly mixed with FeCl3 (0.05 M, 0.1 ml) and ferrozine monosodium salt (0.5 mM, 0.1 ml) and measured at 562 nm (A1).

| (3) |

where A0 is the absorbance of water instead of the BLHs and SBLHs.

2.15. Microstructure characterization

Scanning electron microscope images of lyophilized BLH and BLHs-100\200\300\400\500 W in 1 kx and 2 kx were recorded.

2.16. Statistic analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Origin 2021 software and SPSS 26.0 software to determine significant differences. p < 0.05 is defined as a significant difference between samples.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Molecular weight distribution

Fig. 2 depicts the Mw distribution of BLHs untreated by sonication and at different sonication powers. Based on the relative contents of the components of bovine liver peptide, it is easy to see that although cavitation effects such as mechanical energy release, high pressure, and localized heat can change the protein structure and regulate its aggregation by accelerating the phase transition and inducing ultrasound-medium interactions under the action of ultrasound's physical magnetic field [26], however, the different powers do not have a significant effect on the molecular weight distribution of BLHs. Pezeshk and Yolandani et al. found that ultrasonic treatment did not cause molecular weight changes in tuna by-products (300 W; 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min) and soy protein isolates (20, 28, 35, 40, and 50 kHz), there was no significant difference in protein bands, which is consistent with the findings of this experiment [27], [28].

Fig. 2.

Relative content of bovine liver peptides with different molecular weights.

The molecular weight of peptides is closely related to their biological activities, and low molecular weight peptides have higher antioxidant activity due to higher oligopeptide content [29]. In the < 500 fractions, BLHs accounted for 48 %, and 37 %–38 % after ultrasonic treatment, which was relatively reduced by about 21.8 %, and in the 500–1000 Da fraction, BLHs accounted for 29 %, and the molecular weight accounted for ultrasonic treatment could be increased by about 13.8 %.Therefore, combined with the results of antioxidant capacity after ultrasonication, it was speculated that the antioxidant components of bovine liver peptide were mainly concentrated in the 500–1000 Da fraction, and similar conclusions were found in sheep bone protein hydrolysate that the 500–1300 Da fraction showed stronger antioxidant capacity [30].

3.2. Surface hydrophobicity

Under hydrophobic interactions, surface hydrophobicity is an important factor in determining the conformational and functional properties of proteins [31]. Under the intervention of ultrasound (100–500 W), the surface hydrophobicity of bovine liver peptides showed a tendency to increase and then decrease, with the highest surface hydrophobicity at an ultrasound power of 200 w, which was significantly different from that of the untreated bovine liver peptides (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). According to previous similar studies, the cavitation effect of ultrasound produces tiny bubbles and microbeams, which are conducive to destroying non-covalent bonds, revealing the molecular structure of proteins, and exposing Phe, Trp, Tyr, etc and further increasing the exposure rate of hydrophobic amino acid residues in proteins, thus enhancing the surface hydrophobicity of proteins [32], [33]. However, when the ultrasound power reached 500, the bovine liver peptide exhibited a decrease in surface hydrophobicity, possibly due to hydrophobicity-driven protein proximity and aggregation, which allowed the exposed hydrophobic groups to be encapsulated in the protein [32], [33], another possibility is due to the re-polymerization of proteins by hydrophobic binding at high ultrasound power [34]. In addition, Ding et al. reported that ultrasonication caused a rearrangement of the tertiary protein structure of mantle proteins from scallops, leading to molecular unfolding, which increased their surface hydrophobicity [26]. While the surface hydrophobicity of soybean isolate proteins increased from 200 W to 400 W and decreased at 600 W [35]. There are some differences in the effect of the appropriate selection of ultrasonic power on the structural changes of different substrates.

Fig 3.

a. Surface hydrophobicity of bovine liver peptides at different ultrasonic power. b. The average particle size of bovine liver peptide under different ultrasonic power. note: different lowercase letters represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.3. Particle size

Particle size is used to characterize the degree of protein aggregation[36], As shown in Fig. 3b, low-power ultrasound treatment (100–200 W) significantly increased the average particle size of bovine liver peptides (p < 0.05), which, combined with the scanning electron microscopy results, may be attributed to the initial fragmentation of the bovine liver polypeptides due to the formation of outwardly extending unstable aggregates caused by low power ultrasound. The decreasing trend in particle size with increasing ultrasound power (300–500 W) may be attributed to the turbulence effect produced by intense ultrasound collisions, cavitation, and strong shear that disrupts the intense collisions and non-covalent interactions between the protein aggregates [37]. Ding et al. also showed that mung bean protein can reduce the average particle size from 326.3 to 290.13 nm under 500 W high-power ultrasound conditions [26].

3.4. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The secondary structure of BLHs is shown in Fig. 4a, with the amide A peak at 3010 cm-1 for the control and the amide A peak in the range of 2979–2998 cm-1 for BLHs (100-500 W) after sonication. Typically, the amide A band occurs at 3400–3440 cm-1. However, when the N-H group forms hydrogen bonds, it may shift to a lower wave number, so the sonicated bovine liver peptide appears to have more hydrogen bonding interactions, which results in a shift to a lower wave number, this is similar to the conclusions of ultrasonic extraction of tuna by-products and ultrasonically treated mung bean protein hydrolysate [34], [27]. In addition, the hydrophobic region of proteins induced by C-H stretching vibrations can be reflected in the range of 3000–2800 cm-1 [38], which shows that the C-H tensile vibration is enhanced after ultrasonic treatment. Due to C=O stretching and N-H bending, the main peak of amide I of BLHs and sonicated-BLHs appeared at about 1600–1700 cm-1, which is usually directly related to the conformation of the polypeptide chain. The amplitude of bovine liver peptides was increased in the sonicated peptides compared to the control group, which was probably due to the thermal effect and the sonication-induced unfolding of aggregation between the reactive moieties, which reduces the cross-linking between protein molecules [39]. Similarly, improved functional properties of quinoa proteins after high-intensity sonication were reported to be associated with an increase in α-helices and the formation of aggregates [40]. The amide II bands appeared at 1500–1600 cm-1, which might be caused by C-N stretching, but the absorption peaks were in similar positions. Therefore, the introduction of ultrasound may mainly act on hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction, which in turn induces the protein secondary structure to become loose and disordered, which is conducive to further improving the functional properties of bovine liver peptides.

Fig. 4.

a. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra; b. Fluorescence spectra; c. x-ray diffraction; d. Differential calorimetric scanning (DSC).

3.5. Intrinsic fluorescence spectrum

Fig. 4b shows the fluorescence spectra of BLHs in the range of 330–500 nm and BLHs under ultrasonication and analyses the changes in the tertiary structure of bovine liver peptide proteins. The fluorescence emission is mainly dependent on the protein folding tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine residues in the proteins are used to reflect the conformational changes in the tertiary structure [41]. There was no significant change in the λ maxima of BLHs-100\200\300\400\500 compared to BLHs. The fluorescence intensity after sonication was overall lower than the fluorescence signal intensity of BLHs, indicating that sonication contributes to the alteration and partial unfolding of the tertiary structure of bovine liver peptides. This may be related to an increase in the number of fluorescence bursting groups or energy transfer [18]. The fluorescence signal intensity was highest at 300 W ultrasound powers, the fluorescence intensity was related to the content of aromatic amino acids within the protein molecule or surrounded by non-polar amino acids so that appropriate ultrasound power exposed the aromatic amino acid residues, but higher ultrasound power caused protein folding so that the aromatic amino acid residues that had already been exposed were returned to the interior of the protein [32], [33].

3.6. X-ray diffraction (XRD) assay

Both BLHs and ultrasonicated BLHs showed obvious characteristic diffraction peaks at 19.2° (Fig. 4c), indicating that different ultrasonic powers in the range of 100–500 W did not significantly affect the structure of bovine liver peptides and retained the main chemical structure. In the relevant report on the effect of ultrasound on keratins, we found that there was no significant change in the peak intensities of keratins with the increase of power, which was like the conclusion of this experimental study. However, with the increase in ultrasound time, the peak intensity decreases [42]. It is therefore reasonable to assume that although ultrasound can generate high-speed shear forces and destroy local hierarchical structures, the main chemical structure of bovine liver peptides has not been altered, possibly due to other factors such as the duration of ultrasound action.

3.7. Thermodynamic properties

The proteins before and after sonication of bovine liver peptides were thermodynamically analyzed using DSC. As shown in Fig. 4d, all samples showed a broad absorption peak at approximately 130 °C-150 °C, indicating some form of thermal transition, which corresponds to the thermal denaturation temperature of bovine liver peptides. Among them, the absorption peak of 139.4 °C for the sonicated untreated bovine liver peptide was taken as the critical center, and it was found that the thermal denaturation temperature was shifted to the left at sonication powers of 100 w and 200 w. This indicated that the thermal stability of bovine liver peptide was reduced under low power sonication conditions, probably due to the local deformation and accelerated movement of molecules caused by ultrasound, which was a result of the unfolding of the protein structure, and that the thermal denaturation temperature of bovine liver peptide was shifted to the left with the increase in ultrasound power at 500 W With the increase of ultrasonic power, the thermal denaturation temperature of bovine liver peptide was maximum at 500w, which showed good thermal stability. Energy changes can be used to assess the degree of denaturation and aggregation of proteins [43]. With the increase of ultrasound power, the energy changes firstly increased and then decreased, and reached the lowest value at the ultrasound power of 400 W. The thermodynamic structure was more stable, which might be related to the folded or aggregated state of the bovine liver peptide. In addition, moderate sonication showed that the thermodynamic stability of bovine liver peptides could be improved to a certain extent to avoid unfavorable changes such as precipitation or aggregation under thermal processing conditions.

3.8. Characterization of antioxidant performance

Measurement of reducing power by reduction of trivalent iron (Fe3+) to ferrous iron [38]. The reducing power of ultrasonically treated BLHs increased with increasing ultrasound power from 100 W to 500 W. At 10 mg/mL, the reducing power of BLHs, BLHs-100 W, BLHs-200 W, BLHs-300 W, BLHs-400 W, and BLHs-500 W was in the range of 0.6553–1.2447 (Fig. 5a), and the data showed that the ultrasonically treated BLHs all had more reducing power than BLHs, which was increased by 47.82–89.94 % by the intervention of ultrasound, and similarly, the reducing power of whey protein isolate increased from 0.02 to 0.61 [44], this phenomenon may be because ultrasonication can increase the content of specific amino acids in protein hydrolysates such as Phe and Tyr, which have strong electron-donor capacity, to enhance the scavenging of free radicals, and thus improve the antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of antioxidant capacity of bovine liver hydrolysate at different ultrasonic power. Note: Different lowercase letters represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

Fe2+ chelating capacity assesses lipid oxidation, and cell and tissue damage [45]. The Fe2+ chelating capacity was 21.75 %-62.18 % at 2–10 mg/mL of BLHs, BLHs-100 W, BLHs-200 W, BLHs-300 W, BLHs-400 W and BLHs-500 W (Fig. 5b). There was no significant difference between the sonicated bovine liver peptides at low concentrations at low power (p > 0.05). However, overall sonication improved the Fe2+ chelating ability of BLHs, especially MPH-400 W and MPH-500 W. sonication may increase the number of carboxyl and amino groups of acidic and basic amino acid branched chains to generate more negative charges, which is favorable for Fe2+ binding, and thus bovine liver peptides exhibited stronger Fe2+ chelating ability under some degree of sonication.

After the DPPH radical is removed, the absorbance of its solution gradually decreases, and the color changes from dark purple to yellow [46]. Therefore, the DPPH radical scavenging capacity can be used to quantify the antioxidant activity. As shown in Fig. 5c, the DPPH radical scavenging ability was significantly enhanced with increasing BLHs concentration (p < 0.05). The free radical scavenging rates of BLHs-100 W, BLHs-200 W, BLHs-300 W, BLHs-400 W, and BLHs-500 W at 10 mg/mL could reach 71.30–76.02 %, which were significantly higher than those of BLHs 65.40 % (p < 0.05). These data showed that the DPPH radical scavenging activity of BLHs was enhanced by 9.02 %-16.23 % with the increase of ultrasonic power from 100 W to 500 W. This demonstrated that BLHs could terminate the radical chain reaction by converting the radicals into more stable products. That ultrasonication could enhance this ability [47].

Fig. 5d shows that the ABTS radical scavenging activity of BLHs and sonicated BLHs increased from 27.36 % to 82.66 % when the concentration was increased from 2 to 10 mg/mL presenting a stoichiometric concentration dependence, with 10 mg/mL BLHs, BLHs-100 W, BLHs-200 W, BLHs-300 W, BLHs-400 W, and BLHs-500 W reaching 72.55 %-82.66 %, and the maximum ABTS scavenging activity of bovine liver peptide was observed when the ultrasonic power reached 500, which increased the antioxidant property of bovine liver peptide by 13.94 % relative to that of the non-ultrasonicated bovine liver peptide, thus, ultrasonication significantly increased the ABTS radical scavenging activity of BLHs (p < 0.05). Similarly, He and Zou et al. found that the ABTS radical scavenging activity of bovine hides collagen hydrolysate and porcine brain hydrolysate was significantly enhanced by ultrasonic treatment [19], [48]. This may be due to the high turbulence and shear energy generated by sonication, which exposes more hydrophobic ends of the bovine liver peptide, thus enhancing the ABTS radical scavenging activity of BLHs.

3.9. Microstructure characterization

The microstructures of the ultrasound untreated and treated bovine liver peptide samples were observed by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 6). The figure shows an irregular dense microstructure (From left to right, scanning electron microscope images of BLHs, BLHs-100, BLHs-200, BLHs-300, BLHs-400, and BLHs-500 at 1kx and 2kx.). Without ultrasound treatment, the surface of the bovine liver peptide showed a dense porous aggregated structure with surface folds. With the intervention of ultrasound, the impact and cavitation effects generated by the ultrasound treatment led to the loosening of the protein structure and had a dispersing effect on the protein structure [26]. The surface of bovine liver peptides appeared to extend outwards at an ultrasound power of 100 w. In the study of ultrasound-induced acid-soluble collagen in tuna skin, a short period of ultrasound action affected the structure and length of the original protein, due to shear forces, the sample became fragmented and the surface became rougher as the ultrasonic power increased. This phenomenon may be due to the dismantling of protein aggregates by the shear forces released by the rupture of cavitation bubbles during compression, high temperature, and high pressure [27]. When the ultrasonic power reached 500 W, a small amount of aggregation of bovine liver peptide occurred, which increased the particle size of the protein, this phenomenon was consistent with the trend of the experimental results of the particle size, and the results of the study showed that ultrasound-induced microstructures of bovine liver peptide underwent obvious physical changes.

Fig. 6.

Schematic structure of microscopic scanning electron microscopy of bovine liver peptide under different ultrasonic power.

4. Conclusion

With the increasing demand for sustainable development, the development of natural antioxidant products is crucial for the growing population. Through the present study, we have demonstrated that the modification method of ultrasound, appropriately invoked, can promote the alteration and partial unfolding of the structure of bovine liver peptides, enhance the antioxidant properties of bovine liver peptides and improve their thermal stability to cater to the demands of thermal processing. The above results suggest that ultrasonication is a useful tool to assist in the modification of bovine liver peptides, offering the possibility of expanding their application in the food industry and improving the antioxidant properties of animal-derived protein peptides in general for commercial application.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yufeng Duan: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Xue Yang: Conceptualization. Dan Deng: Conceptualization. Li Zhang: Project administration, Resources. Xiaotong Ma: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Long He: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Xiaopeng Zhu: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Xinjun Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Hebei Province Modern Agriculture Industry Technology System Beef Cattle Industry Innovation Team Construction Project (HBCT2018130204), Key Technology Integration and Industrialization Demonstration for Beef and Lamb Slaughtering and Processing (2021A02003-3), and the program for China modern Agricultural industry Research System (Cattle and Yak) (No. CARS-37).

References

- 1.Zou Y., Shahidi F., Shi H.B., Wang J.K., Huang Y., Xu W.M., Wang D.Y. Values-added utilization of protein and hydrolysates from animal processing by-product livers: a review. Trend. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;110:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Salem F.M., Abou Arab E.A. Chemical properties, microbiological quality and sensory evaluation of chicken and duck liver paste (foie gras) Grasas Aceites. 2010;61(2):126–135. doi: 10.3989/gya.074908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martín-Sánchez A.M., Ciro-Gómez G., Vilella-Esplá J., Pérez-Alvarez J.A., Sayas-Barberá E. Physicochemical and sensory characteristics of spreadable liver pates with annatto extract (Bixa orellana L.) and date palm co-products (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Foods. 2017;6(11) doi: 10.3390/foods6110094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong G.Y., Gao X.Q., Wang P., Xu X.L., Zhou G.H. Comparative study of extraction efficiency and composition of protein recovered from chicken liver by acid-alkaline treatment. Process Biochem. 2016;51(10):1629–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X., Zou Y., Wang D.Y., Xiong G.Y., Xu W.M. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment on the extent of Maillard reaction and the structure, taste and volatile compounds of chicken liver protein. Food Chem. 2020;331 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soares M., Rezende P.C., Corrêa N.M., Rocha J.S., Martins M.A., Andrade T.C., do NascimentoVieira F. Protein hydrolysates from poultry by-product and swine liver as an alternative dietary protein source for the Pacific white shrimp. Aquacult. Rep. 2020;17 doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2020.100344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chafik A., Essamadi A., Çelik S.Y., Mavi A. Purification of camel liver catalase by zinc chelate affinity chromatography and pH gradient elution: an enzyme with interesting properties. J. Chromatogr. B-Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2017;1070:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chafik A., Essamadi A., Çelik S.Y., Mavi A. Purification and biochemical characterization of a novel copper, zinc superoxide dismutase from liver of camel (Camelus dromedarius): an antioxidant enzyme with unique properties. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;86:428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lv R.Z., Dong Y.F., Bao Z.J., Zhang S.M., Lin S.Y., Sun N. Advances in the activity evaluation and cellular regulation pathways of food-derived antioxidant peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022;122:171–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J., Wang Y., Dang X., Zheng X., Zhang W. Housefly larvae hydrolysate: orthogonal optimization of hydrolysis, antioxidant activity, amino acid composition and functional properties. BMC. Res. Notes. 2013;6:197. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez C., Rendueles M., Díaz M. Production of porcine hemoglobin peptides at moderate temperature and medium pressure under a nitrogen stream. functional and antioxidant properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(22):5636–5643. doi: 10.1021/jf300400k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrajo P., Pateiro M., Gagaoua M., Franco D., Zhang W.G., Lorenzo J.M. Evaluation of the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of porcine liver protein hydrolysates obtained using alcalase, bromelain, and papain. Appl. Sci.-Basel. 2020;10(7) doi: 10.3390/app10072290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Alvarez O., Chamorro S., Brenes A. Protein hydrolysates from animal processing by-products as a source of bioactive molecules with interest in animal feeding: a review. Food Res. Internat. 2015;73:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W.X., Huang L.R., Chen W.W., Wang J.L., Wang S.H. Influence of ultrasound-assisted ionic liquid pretreatments on the functional properties of soy protein hydrolysates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadam S.U., Tiwari B.K., Alvarez C., O'Donnell C.P. Ultrasound applications for the extraction, identification and delivery of food proteins and bioactive peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015;46(1):60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He L., Gao Y.F., Wang X.Y., Han L., Yu Q.L., Shi H.M., Song R.D. Ultrasonication promotes extraction of antioxidant peptides from oxhide gelatin by modifying collagen molecule structure. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou Y., Shi H.B., Chen X., Xu P.P., Jiang D., Xu W.M., Wang D.Y. Modifying the structure, emulsifying and rheological properties of water-soluble protein from chicken liver by low-frequency ultrasound treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;139:810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X., Jiang D., Xu P.P., Geng Z.M., Xiong G.Y., Zou Y., Xu W.M. Structural and antimicrobial properties of Maillard reaction products in chicken liver protein hydrolysate after sonication. Food Chem. 2021;343 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L., Xia Q., Cao J.X., He J., Zhou C.Y., Guo Y.X., Pan D.D. Ultrasonic effects on the headspace volatilome and protein isolate microstructure of duck liver, as well as their potential correlation mechanism. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.do Evangelho, J. A., Vanier, N. L., Pinto, V. Z., De Berrios, J. J., Dias, A. R. G., & Zavareze, E. D. (2017). Black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) protein hydrolysates: Physicochemical and functional properties. Food Chem., 214, 460-467. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Habinshuti I., Mu T.H., Zhang M. Ultrasound microwave-assisted enzymatic production and characterisation of antioxidant peptides from sweet potato protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;69 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He L., Cao Y.Y., Wang X.Y., Wang Y.R., Han L., Yu Q.L., Zhang L. Synergistic modification of collagen structure using ionic liquid and ultrasound to promote the production of DPP-IV inhibitory peptides. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023;103(9):4603–4613. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu T., Liu L. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan nanoemulsions loading thymol or thyme essential oil for the preservation of refrigerated pork. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C., Huang X.J., Peng Q., Shan Y.Y., Xue F. Physicochemical properties of peanut protein isolate-glucomannan conjugates prepared by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(5):1722–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamróz E., Kulawik P., Krzysciak P., Talaga-Cwiertnia K., Juszczak L. Intelligent and active furcellaran-gelatin films containing green or pu-erh tea extracts: characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;122:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding Q.Y., Tian G.F., Wang X.H., Deng W.Y., Mao K.M., Sang Y.X. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the structure and functional properties of mantle proteins from scallops (Patinopecten yessoensis) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;79 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pezeshk S., Rezaei M., Abdollahi M. Impact of ultrasound on extractability of native collagen from tuna by-product and its ultrastructure and physicochemical attributes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;89 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yolandani, Ma, H. L., Li, Y. L., Liu, D. D., Zhou, H. C., Liu, X. S., Zhao, X. X. (2023). Ultrasound-assisted limited enzymatic hydrolysis of high concentrated soy protein isolate: Alterations on the functional properties and its relation with hydrophobicity and molecular weight. Ultrason. Sonochem., 95. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Esteve C., Marina M.L., García M.C. Novel strategy for the revalorization of olive (Olea europaea) residues based on the extraction of bioactive peptides. Food Chem. 2015;167:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu G.H., Dou L., Zhang J., Su R.A., Corazzin M., Sun L.A., Su L. Exploring the antioxidant stability of sheep bone protein hydrolysate-identification and molecular docking. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2024;192 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi L.S., Yang X.Y., Gong T., Hu C.Y., Shen Y.H., Meng Y.H. Ultrasonic treatment improves physical and oxidative stabilities of walnut protein isolate-based emulsion by changing protein structure. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2023;173 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.114269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li R.N., Xiong Y.L.L. Ultrasound-induced structural modification and thermal properties of oat protein. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;149 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H.J., Hu Y.F., Zhao X.H., Wan W., Du X., Kong B.H., Xia X.F. Effects of different ultrasound powers on the structure and stability of protein from sea cucumber gonad. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F.F., Li Y.Q., Sun G.J., Wang C.Y., Liang Y., Zhao X.Z., Mo H.Z. Influence of ultrasound treatment on the physicochemical and antioxidant properties of mung bean protein hydrolysate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan S.Z., Xu J.W., Zhang S., Li Y. Effects of flexibility and surface hydrophobicity on emulsifying properties: ultrasound-treated soybean protein isolate. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang B., Du X., Kong B.H., Liu Q., Li F.F., Pan N., Zhang D.J. Effect of ultrasound thawing, vacuum thawing, and microwave thawing on gelling properties of protein from porcine longissimus dorsi. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulseren I., Guzey D., Bruce B.D., Weiss J. Structural and functional changes in ultrasonicated bovine serum albumin solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14(2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y.Y., Wang C.Y., Wang S.T., Li Y.Q., Mo H.Z., He J.X. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) seed protein hydrolysates obtained with different proteases. Food Chem. 2021;345 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karnjanapratum S., Benjakul S. Asian bullfrog (Rana tigerina) skin gelatin extracted by ultrasound-assisted process: Characteristics and in-vitro cytotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;148:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vera A., Valenzuela M.A., Yazdani-Pedram M., Tapia C., Abugoch L. Conformational and physicochemical properties of quinoa proteins affected by different conditions of high-intensity ultrasound treatments. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;51:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin J., Ma H.L., Wang K., Yagoub A.A., Owusu J., Qu W.J., Ye X.F. Effects of multi-frequency power ultrasound on the enzymolysis and structural characteristics of corn gluten meal. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;24:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin X.J., Yang C., Guo Y.J., Liu J.Q., Bitter J.H., Scott E.L., Zhang C.H. Effect of ultrasound on keratin valorization from chicken feather waste: process optimization and keratin characterization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;93 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevkani K., Singh N., Kaur A., Rana J.C. Structural and functional characterization of kidney bean and field pea protein isolates: a comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;43:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu L., Li X.D., Du L.L., Zhang X.X., Yang W.S., Zhang H.D. Effect of ultrasound assisted heating on structure and antioxidant activity of whey protein peptide grafted with galactose. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2019;109:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nikoo M., Regenstein J.M., Noori F., Gheshlaghi S.P. Autolysis of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by-products: Enzymatic activities, lipid and protein oxidation, and antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie Z., Huang J., Xu X., Jin Z. Antioxidant activity of peptides isolated from alfalfa leaf protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2008;111(2):370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J., He J., Dang Y.L., Cao J.X., Sun Y.Y., Pan D.D. Ultrasound treatment on the structure of goose liver proteins and antioxidant activities of its enzymatic hydrolysate. J. Food Biochem. 2020;44(1) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou Y., Wang W., Li Q., Chen Y., Zheng D.H., Zou Y.M., Yang L.Q. Physicochemical, functional properties and antioxidant activities of porcine cerebral hydrolysate peptides produced by ultrasound processing. Process Biochem. 2016;51(3):431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2015.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]