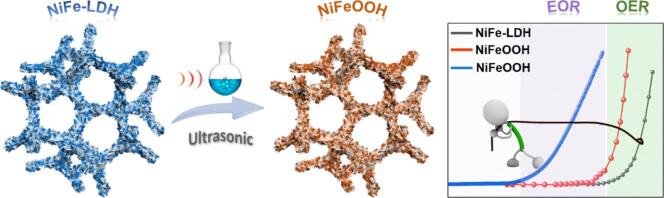

Graphical abstract

A novel ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction inducing surface reconstruction strategy enables the low-spin states of Ni2+ () and Fe2+ () on the NiFe-LDH surface to partially transform into high-spin states of Ni3+ () and Fe3+ () and formation of the highly active species of NiFeOOH. The as-prepared electrode not only shows superior activity for water oxidation but also for various organics electrooxidation.

Keywords: Ultrasonic, Fenton reaction, NiFe-LDH, Surface reconstruction, Electrooxidation

Abstract

Nickel/iron-layered double hydroxide (NiFe-LDH) tends to undergo an electrochemically induced surface reconstruction during the water oxidation in alkaline, which will consume excess electric energy to overcome the reconstruction thermodynamic barrier. In the present work, a novel ultrasonic wave-assisted Fenton reaction strategy is employed to synthesize the surface reconstructed NiFe-LDH nanosheets cultivated directly on Ni foam (NiFe-LDH/NF-W). Morphological and structural characterizations reveal that the low-spin states of Ni2+ () and Fe2+ () on the NiFe-LDH surface partially transform into high-spin states of Ni3+ () and Fe3+ () and formation of the highly active species of NiFeOOH. A lower surface reconstruction thermodynamic barrier advantages the electrochemical process and enables the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode to exhibit superior electrocatalytic water oxidation activity, which delivers 10 mA cm−2 merely needing an overpotential of 235 mV. Besides, surface reconstruction endows NiFe-LDH/NF-W with outstanding electrooxidation activities for organic molecules of methanol, ethanol, glycerol, ethylene glycol, glucose, and urea. Ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction inducing surface reconstruction strategy will further advance the utilization of NiFe-LDH catalyst in water and organics electrooxidation.

1. Introduction

Electrolysis of water to extract hydrogen represents one of the highly promising avenues for achieving sustainable energy production as well as addressing ever-increasing resource crises and environmental pollution [1], [2]. Nevertheless, its productivity is dramatically hindered by the half-water oxidation reaction due to the slow reaction kinetics caused by the complex four-electron transfer process [3], [4]. At present, developing efficient electrocatalysts to lower the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) overpotential or coupling organics molecule electrooxidation reactions (EORs, possessing lower theoretical voltage) instead of OER are both feasible strategies for reducing energy consumption and improving the economy [5]. As a consequence, various up-and-coming electrocatalysts, such as noble-metal-based RuO2 and IrO2, hydroxides, oxides, sulfides, and phosphides are designed and synthesized [6], [7]. Particularly, nickel/iron-layered double hydroxide (NiFe-LDH) has proven to be an appealing candidate for OER thanks to its low cost as well as superior activity [8], [9], [10]. Understanding the OER mechanism holds immense significance to ulteriorly boost the activity of the NiFe-LDH catalyst.

In the alkaline OER process, the NiFe-LDH catalyst tends to undergo an electrochemically induced surface reconstruction and formation of the corresponding (oxy)hydroxide (NiFeOOH) [11]. The reconstructed NiFeOOH is widely regarded as the true active species because the high spin states of Ni3+ with electron configuration is an advantage in strengthening the covalent character of metal–oxygen bonds [12], [13], [14]. The Fe3+ () is conducive to adjusting the valence state of Ni3+ in NiFeOOH during the OER process and thus promotes its catalytic activity [15], [16]. Besides, a lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism (LOM) can be also triggered in NiFeOOH to maximize the use of surface metals and oxygen atoms as active sites [15]. During anodic polarization, an evident oxidation peak occurring in regions much lower than that of OER onset potential is commonly observed from the perspective of experiments [17]. Besides, surface reconstruction is also found in several organics EORs such as urea, lignin derivatives, and ethylene glycol electrooxidation processes [18]. Consequently, excess electric energy needs to be consumed to overcome the reconstruction thermodynamic barrier. To activate surface reconstruction of catalysts, most of the research efforts are attention to adjusting the applied electrochemical oxidation voltage, but posing challenges in synthesis using conventional techniques [19], [20]. Therefore, urgently desired to develop more reasonable and effective approaches to activate and regulate the surface reconstruction, thereby further boosting the OER and organics EORs reactivities of the NiFe-LDH catalyst.

Herein, a surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH nanosheets grown directly on Ni foam surfaces (NiFe-LDH/NF-W) is prepared through a novel ultrasonic wave-assisted synthesis strategy. The addition of H2O2 not only triggers the Fenton reaction with the Fe2+ but also generates strong oxidation species •OH under ultrasonic wave irradiation, which facilitates the low-spin states of Ni2+ () and Fe2+ () transform into high-spin states of Ni3+ () and Fe3+ (). Morphological and structural characterizations reveal that the highly active species of NiFeOOH with amorphous are formed on the NiFe-LDH surface. It lowers the surface reconstruction barrier from NiFe-LDH to NiFeOOH throughout the electrochemical procedure. Surface reconstruction endows the NiFe-LDH/NF-W with superior OER catalytic activity (η = 235 mV @ 10 mA cm−2) and organic molecules (methanol, ethanol, glycerol, ethylene glycol, glucose, and urea) oxidation activities. Ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction inducing surface reconstruction strategy paves a new path for further boosting the electrochemical oxidation activities of NiFe-LDH catalysts.

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials

Ni foams (thickness: 1.0 mm) were ordered from Hebei Ruiyun Silk Mesh Technology Co. Ltd.. Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (98 %), Fe(NO3)3·9H₂O (99.99 %), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30 wt% in H2O), KOH (99.99 %), Methanol (99.5 %), Ethanol (99.5 %), Glycerine (99 %), Ethylene glycol (98 %), ɑ-D-Glucose (≥99.5 %), Urea (99 %) were ordered from Sinopharm Chemical Regent Co, Ltd, China, and utilized directly without any subsequent purification steps.

2.2. Preparation of NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode

An altered hydrothermal approach was utilized to prepare the electrode of NiFe-LDH nanosheets in situ grown on Ni foam surfaces (NiFe-LDH/NF-H). In brief, 0.33 mmol of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.33 mmol of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, and 1.67 mmol of urea were firstly mixed in 30 ml distilled water and subsequently poured 50 ml hydrothermal reactor. Afterward, a segment of Ni foam (1 cm × 5 cm, washed with distilled water, ethanol, and 1 M HCl at least three times to clean its surfaces) was submerged within the blended solution and treated in an oven at 120 ℃ for 12 h. Ultimately, the NiFe-LDH/NF-H obtained underwent rinsing with distilled water and ethanol and then dried under vacuum at room temperature The mass of the catalysts loaded on the nickel foam surface is weighed as c.a. 3.8 mg.

2.3. Preparation of NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes

A novel ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction synthesis method was utilized to prepare the NiFe-LDH catalyst with surface partial reconstruction (NiFe-LDH/NF-W). Namely, the as-obtained NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode was placed in a flask containing 0.1 M hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and placed in a controllable temperature ultrasonic synthesis instrument (XH-2008D, parameters: 600 W, 25 KHz, 25 ℃, 200 mL of round-bottomed flask; Beijing Xianghu Science and Technology Development Company, China) for operating 10 min. After being rinsed with distilled water and ethanol and drying at room temperature under vacuum, the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode was finally synthesized. The mass of the catalysts loaded on the nickel foam surface is weighed as c.a. 2.2 mg. Besides, the reaction times of 1 min, 5 min, and 20 min were employed to explore their effect on the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes.

2.4. Characterization of electrodes

The crystal structures of the as-synthesized NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/max-2550 diffractometer with Ni filtered Cu Kα irradiation), Raman spectra (Renishaw Invia confocal micro-Raman), vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) (LakeShore 8604), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab 250XI, Thermo, USA). The nanostructures were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-5610LV) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 S-Twin microscopes).

2.5. Electrochemical experiments

The electrochemical experiments were taken on a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation. The as-prepared NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W (1 cm × 1 cm) acted as the working electrode, Pt plate (1 cm × 1 cm), and Hg/HgO as counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The electrocatalytic water oxidation was measured in 1 M KOH. Notably, other electrooxidation experiments were tested in 1 M KOH+x (x = 1 M methanol, 1 M ethanol, 0.1 M glycerol, 1 M ethylene glycol, 0.01 M glucose, 0.33 M urea, and 3 M NaCl solution). All the potentials were referenced to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE): ERHE=EHg/HgO+0.098 + 0.059 × pH.

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) plots were tested at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 apart from the water oxidation process (1.0 mV s−1). Electrochemical surface areas (ECSA) were derived through cyclic voltammetry (CV) in the non-Faradaic regions with different scan rates (20–60 mV s−1) [21]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of various electrocatalytic oxidation reactions was conducted within a frequency range spanning from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz under their open-circuit voltages. The durability properties under 300 mA cm−2 were measured by chronopotentiometry and using a thermostat water bath to control reaction system temperatures. The temperature-dependent LSV measurements were acquired to evaluate the electrocatalytic water oxidation activation energy (Ea) according to the Arrhenius formula [12], [22]. In operando Nyquist and Bode spectrums were recorded at 0.92–1.53 V (vs RHE) with a step of 0.05 V and an amplitude of 5 mV sweeping frequencies from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz. FT A.C. Voltammetry (FTACV) was performed within a potential range of 0 to 0.7 V (vs Hg/HgO), utilizing a potential amplitude of 100 mV and an alternating current frequency of 10 Hz. The first to the 6th harmonic transformed I–V curve from 32,768 data points recorded by the CHI software. The I–V curve, which originated from 32,768 data points recorded by the CHI software, underwent a harmonic transformation, resulting in the generation of the first through sixth harmonic curves.

2.6. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The DFT simulations were performed utilizing the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) [23]. The spin-unrestricted PBE functional was employed to assess the exchange and correlation energies, while the conjugate gradient algorithm was utilized to relax the structures until convergence was achieved, ensuring that the forces and total energy on all atoms were below 0.01 eV Å−1 and 1 × 10-5 eV, respectively [24], [25]. The plane-wave basis set was utilized with a kinetic energy cutoff set at 400 eV. The integration of the Brillouin zone was performed using a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack grid. The dominant exposed (0 0 3) facet of Ni0.67Fe0.33-LDH and (0 0 1) facet of Ni0.67Fe0.33OOH was selected as the preferred computational model. The atomic ratio of 2 to 1 was utilized according to the calculated contents of Ni and Fe cations in NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W by fitted XPS areas (Table S1).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Formation mechanism of surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH/NF-W

The surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes were synthesized through an ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction synthesis method. As displayed in Fig. 1a, the electrode comprising NiFe-LDH nanosheets grown directly on Ni foam surfaces (NiFe-LDH/NF-H) was first prepared via a modified hydrothermal approach. Afterward, the as-prepared NiFe-LDH/NF-H was preoxidized by the H2O2 under ultrasonic wave irradiation. Of note, ultrasonic waves as a non-classical energy source could efficiently reduce reaction times and control nanocrystal morphologies [4], [26]. During the peroxidation process, the H2O2 is in favor of generating the hydroxyl radicals (•OH) with strong oxidizing property (EORP=2.8 V) (equation (1),

| H2O2 → •OH+OH− | (1) |

Fig. 1.

Morphology analyses of the NiFe-LDH/NF-W catalysts. (a) Simplified visualization of the preparation process for surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH/NF-W, (b) SEM image, (c) TEM image, (d) SAED pattern, (e) HRTEM image, and (f and g) inverse-FFT images for regions Ι and ΙΙ in panel e, respectively. (h) HAADF-STEM image alongside its elemental distribution mappings.

Meanwhile, H2O2 combined with Fe2+ existing on the surface of NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode would spark the well-known Fenton reaction and formation of the high valence state Fe3+ (equation (2) [16],

| Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + •OH+OH− | (2) |

The detected DMPO-•OH signal by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technique can confirm this reaction process (Figure S1) [27]. Additionally, the strong oxidizing of •OH could promote the Ni2+ transformation on the surface of NiFe-LDH/NF-H into Ni3+. Accordingly, the surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes containing high valence states of Fe3+ and Ni3+ were obtained, which will reduce the excess electric energy consumption caused by electrochemical reconstruction in time of the water oxidation process.

3.2. Morphological characterization of electrodes

The morphological characteristics of the as-obtained catalysts are investigated through both SEM and TEM measurements. The SEM characterization of the NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode showcases that the nanosheet array thin film featuring abundant open voids is successfully grown on the Ni foam (Figure S2). After ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction, as can be seen in Fig. 3, Fig. 1b, the 2D nanosheet morphology of the array thin film is well-retained in NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes. Another interesting fact is that the 2D nanosheets tend to thicken and incompletely self-assemble into 3D frameworks as the reaction time progresses from 1 min to 20 min. This phenomenon can be ascribed to the partial stacking and reconstructing between the 2D nanosheets occurring under a long process time. Since the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode prepared at the ultrasonic wave irradiation times of 10 min manifests the optimal catalytic property (discussed further later), comprehensive characterizations and research are focused on this electrode as a case study. TEM image further demonstrates the 2D nanosheets interconnected nanostructure of NiFe-LDH/NF-W (Fig. 1c). The presence of a dispersed array of concentric rings showcased in the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern indicates a polycrystalline structure and observed the (0 0 3) and (0 1 2) crystal planes of NiFe-LDH (Fig. 1d). The HRTEM in Fig. 1e confirms this nanostructure that major crystalline nanodomains are embedded in minor amorphous nanodomains. The crystalline nanodomains exhibit distinct lattice fringes with interplanar spacings of 0.26 and 0.23 nm corresponding to the (0 1 2) and (0 1 5) facets of NiFe-LDH (Fig. 1f and g). Whereas the amorphous nanodomains may result from partial oxidation of the NiFe-LDH surface thereby forming NiFeOOH during the peroxidation process. This result also explains the O atomic% increase of NiFe-LDH/NF-W contrasted with NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode in EDX spectra (Figure S4). Besides, the contents and ratios of Fe and Ni atomic% are well-retained in NiFe-LDH/NF-W (Figure S5). The HAADF-STEM images further reveal an even distribution of O, Fe, and Ni elements (Fig. 1h), verifying that surface partially oxidized NiFe-LDH/NF-W are synthesized by the ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction process.

Fig. 3.

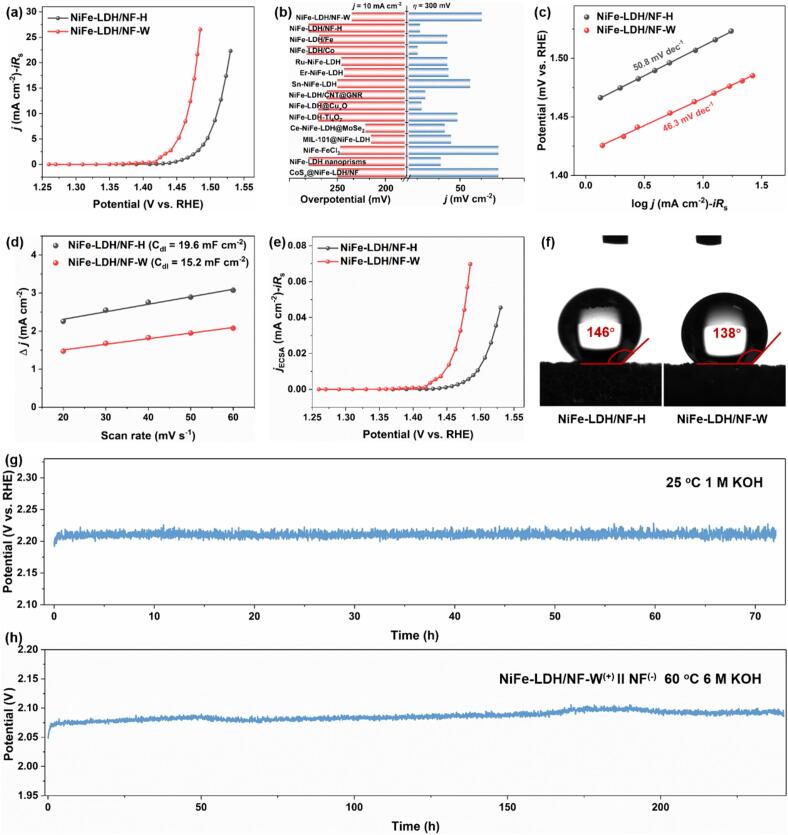

Electrocatalytic water oxidation performances of the NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W. (a) Steady-state LSV curves. (b) Comparison of the η delivered at 10 mA cm−2 and j at 300 mV overpotential. (c) Tafel plots. (d) Plots of the charging current density differences (Δj) versus scan rates reveal a linear slope that is twice the value of the double-layer capacitance (Cdl). (e) Steady-state LSV curves normalized by ECSA. (f) The contact angle of water on the electrodes. (g) Chronopotentiometry plots at j = 300 mA cm−2 under a three-electrode system at 25℃ in 1 M KOH. (h) Voltage-time plots of NiFe-LDH/NF-W(+)IINF(−) cell at j = 300 mA cm−2 at 60℃ in 6 M KOH.

3.3. Structural characterization of catalysts

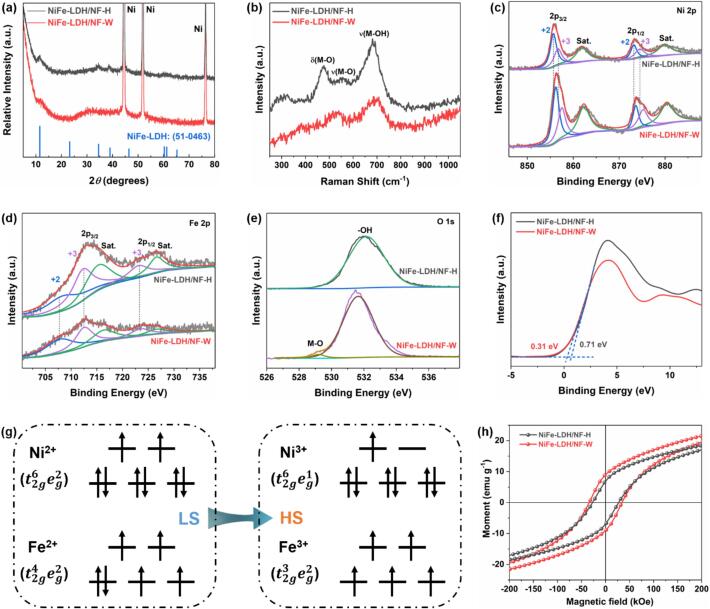

XRD, Raman, XPS, and VSM measurements were employed to analyze the crystalline structures of the as-prepared electrodes (Fig. 2). The XRD pattern in Fig. 2a demonstrates that the NiFe-LDH/NF-H shows a typical NiFe-LDH structure (JCPDS No. 51–0463). After the ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction, the characteristic peaks in NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode become weaker. The reason can be attributed to the surface reconstruction and emergence of amorphous structure, which is consistent with the HRTEM image. Three typical broad peaks are presented in Raman spectra, among which the Raman broad peaks at about 470 and 540 cm−1 are associated with the eg bending and A1g stretching vibrations of metal–oxygen bond in NiFe-LDH, whereas the band concentrated on 680 cm−1 is the asymmetric stretching vibration of the metal-hydroxide group (Fig. 2b) [28], [29]. The weaker and broader Raman peaks in NiFe-LDH/NF-W contrasted with NiFe-LDH/NF-H confirm a higher degree of disorder in its structure. XPS measurement is further conducted to explore the chemical states of the elements. As displayed in Fig. 2c and d, the Ni 2p and Fe 2p spectra manifest the characteristic spin–orbit splitting behaviors of the p orbital, accompanied by two shakeup satellites positioned between the 2p1/2 and 2p3/2, demonstrating that Ni and Fe are in the Ni3+/Ni2+ and Fe3+/Fe2+ oxidation states [30], [31], [32]. It is noteworthy that the relative intensities (peak areas) of Ni3+/Ni2+ (0.85) and Fe3+/Fe2+ (1.55) for NiFe-LDH/NF-W are higher than that of NiFe-LDH/NF-H (0.58 and 1.27) (Table S1), suggesting that the surface reconstruction occurred and may be in the form of NiFeOOH. Surface reconstruction adjusts the filled state of Ni and Fe 3d orbitals and thereby leads to alterations in the electron spin state. As schematic illustrates in Fig. 2g, the low-spin states of Ni2+ () and Fe2+ () transform into the high-spin states of Ni3+ () and Fe3+ () [33]. The magnetic analysis further verifies this result that the saturation magnetization (Ms), residual magnetization (Mr), and coercivity (Hcm) values increase from 18.4 emu g−1, 6.6 emu g−1, and 27.1 kOe to 21.7 emu g−1, 9.1 emu g−1, and 34.8 kOe (Fig. 2h), respectively. Besides, the electro-binding energies of metallic ions have a positive shift, whereas the O2− has a negative shift as well as generates the metal–oxygen bond in NiFe-LDH/NF-W in contrast with the NiFe-LDH/NF-H (Fig. 2e), indicating the charges may be transferred from Ni/Fe to O [34]. The high valence states of Ni3+ and Fe3+ in NiFe-LDH/NF-W are crucial for enhancing its OER activity. As confirmed by the UPS valence-band spectra (Fig. 2f), the calculated valence band maximum values for NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W are approximately 0.71 eV and 0.31 eV, respectively. Because the d states are primarily attributed to the valence electrons located in proximity to the Fermi level [35], [36], a lower valence band certifies that the NiFe-LDH/NF-W is in favor of adsorbing the oxygen-containing species during the OER process.

Fig. 2.

Structure characterizations of the NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W. (a) XRD patterns, (b) Raman spectra, high-resolution XPS spectra of (c) Ni 2p, (d) Fe 2p, and (e) O 1 s, (f) UPS valence-band spectra, (g) Schematic illustration of electron spin state transitions of Ni2+/Ni3+ and Fe2+/Fe3+ (LS: low-spin state, HS: high-spin state), and (h) magnetic hysteresis (M−H) loops.

3.4. Electrocatalytic water oxidation analysis

Subsequently, comprehensive electrochemical tests are conducted to investigate the electrocatalytic water oxidation properties of NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes with surface partial reconstruction. As displayed in Figure S6, LSV curves indicate that the ultrasonic wave irradiation times have a significant effect on their OER activity by tailoring the reconstruction levels. The NiFe-LDH/NF-W obtained at the reaction time of 10 min showcases the lowest overpotential (η) of 266 mV at the current density (j) of 50 mA cm−2. In addition, its OER activity is far outperforming the control samples of Ni foam electrode, NiFe-LDH/NF-H (354 mV), and commercial RuO2 (343 mV) (Figure S7). Therefore, it is selected as the case to study the OER activity and mechanism in-depth. Nevertheless, evaluating the OER activity of electrodes by extracting from potential dynamic LSV curves may induce potential misjudgment [37]. Because the oxidation peaks of the metals-based catalysts may overlap with the OER reaction trend during the elevated anode voltage. To this end, as shown in Figure S8, the chronoamperometry technique was used to measure the steady-state response at potential intervals within the catalytic turnover range. Here, the polarization curves are plotted by extracting the 100th second of every chronoamperometry record from the NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes. A manual iRs-correction rate of 100 % is utilized. As the steady-state LSV curves showcased in Fig. 3a, the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode delivers the j of 10 mA cm−2 merely needing a voltage of 1.465 V (vs RHE) (η = 235 mV), which outperforms the NiFe-LDH/NF-H (η = 280 mV) and most of NiFe-LDH catalysts that have been reported recently (Fig. 3b and Table S2).

To elucidate the underlying reason for the enhanced OER activity observed in the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode, double-layer capacitances (Cdl) are measured through CV curves for the assessment of the electrochemical surface areas (ECSA) (Figure S9). A higher ECSA indicates more active site exposure and higher electrocatalytic capability for electrocatalysts [38]. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, NiFe-LDH/NF-W manifests a slight difference in Cdl value (15.2 mF cm−2) in comparison to the NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode (19.6 mF cm−2). Combined with the LSV plots normalized by ECSA reveals that the enhanced OER catalytic activity of NiFe-LDH/NF-W does not depend on the quantity of active sites but rather on increased intrinsic activity (Fig. 3e). Tafel slope can further corroborate this point because its determination is solely reliant on the reaction kinetics, i.e., the type of active sites, not quantity [39], [40]. Notably, according to the Tafel definition, the steady-state response is essential for its investigation relative to the commonly dynamic tests [37]. As disclosed in Fig. 3c, the steady-state Tafel plots reveal a lower Tafel slope of NiFe-LDH/NF-W (46.3 mV dec-1) compared to NiFe-LDH/NF-H (50.8 mV dec-1), implying that it has preferable active site type and inherent catalytic activity. Additionally, the step of MOH+OH– → MO+H2O+e- is their rate-determining step (RDS) concluded by the well-known Tafel equation [37], [41], which demonstrates that the chemisorption of OH onto metallic active sites is critical for the OER to proceed [12]. Moreover, a smaller contact angle of water for NiFe-LDH/NF-W (138°) than NiFe-LDH/NF-H (146°) demonstrates that it is in favor of H2O adsorption (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, this result also reveals the reason why NiFe-LDH/NF-W enjoys a higher OER performance since the surface reconstructed NiFeOOH facilitates the HO-chemisorption thereby accelerating the OER procedure [41], [42]. It is worth mentioning that the hydrophobicity of electrodes is advantageous to releasing the produced O2 and reducing the metal cations solubility from the surface of the catalyst into the electrolyte to guarantee their stability during the OER. Besides, the hydrophobic property is an efficient strategy to inhibit water oxidation and improve the poorly soluble organics electrooxidation activity in aqueous environment [41], [51]. Hence, the NiFe-LDH/NF-W manifests excellent long-term durability under the j of 300 mA cm−2 for 72h at 25℃ with an inappreciable voltage increase (Fig. 3g). To further meet industrial applications, utilizing the NiFe-LDH/NF-W as the anode and a bare Ni foam as the cathode, an alkaline water electrolysis cell was assembled and operated under industrial conditions, specifically at 60 ℃ and with 6 M KOH. As showcased in Fig. 3h, the NiFe-LDH/NF-W(+)IINF(-) cell achieved a j of 300 mA cm−2 at 2.07 V and only c.a. 4 % activity decay after 240 h, which may be caused by the Ni and Fe cations minor dissolution from the NiFeOOH surface into the electrolyte (Table S3) [11], suggesting its great potential in commercial utilization.

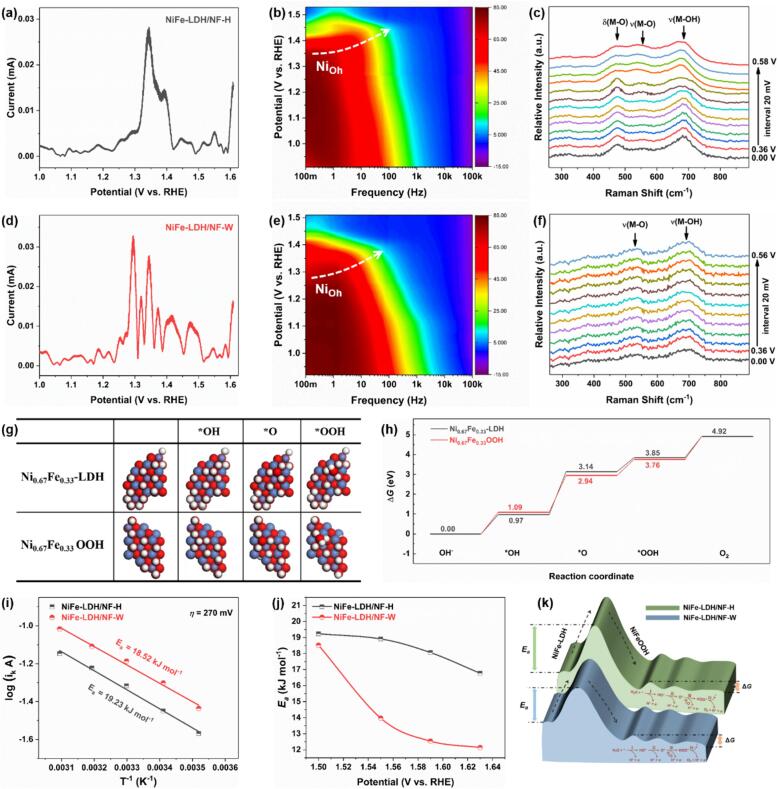

3.5. Evolution of NiFe-LDH/NF-W during the OER process

Combining electrode characterizations with electrochemical measurements reveals that the surface partially reconstructed NiFeOOH endows NiFe-LDH/NF-W with an outstanding OER property. Subsequently, the evolution of NiFe-LDH/NF-W during the OER process is explored using the FTACV, operando EIS, and in situ Raman measurements (Fig. 4). In FTACV (Figure S10), the higher-order harmonic components (≥4) avoid the non-Faradaic process and instead signify currents that are linked to electron transfer and catalytic reactions [43], [44]. Therefore, the 6th harmonic FTACV components of NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W from the region of 1.0 to 1.6 V (vs RHE) are extracted to compare. As displayed in Fig. 4a and d, two distinctive peak sets can be categorized as representing different steps of electron transfer occurring in the OER pathway [45], [46]. The first region (1.2–1.5 V vs RHE) is attributed to the redox of Ni2+/3+ and the structural reconfiguration towards the formation of the NiOOH active center. Whereas the second region beyond 1.5 V is associated with the rapid dissociation of water and the production of O2. Particularly, NiFe-LDH/NF-W exhibits a higher current of 33 μA compared to the NiFe-LDH/NF-H (28 μA) in the former region, proving its faster structural transformation toward the oxyhydroxide. This result can be further corroborated by the operando EIS. Here, the OCV of NiFe-OH/NF-H and NiFe-OH/NF-W electrodes are 0.01 and 0.03 V vs. Hg/HgO, respectively. As showcased in 2D contour Bode plots (Fig. 4b and e), both electrodes exhibit a single-phase angle peak locus that undergoes decay at the low-frequency region of 0.1–200 Hz for NiFe-LDH/NF-H and 0.1–70 Hz for NiFe-LDH/NF-W, which corresponds to the reconstruction of octahedral coordination for Ni ions (Nioh) in NiFe-LDH [44], [47]. Moreover, this reconstruction of Nioh reaches its maximum at c.a. 1.35 and 1.28 V (vs RHE), which aligns with the FTACV results. Because the low-frequency region is associated with the OER process, a lower onset potential of NiFe-LDH/NF-W (1.42 V) than NiFe-LDH/NF-H (1.45 V) further confirms that the former electrode enjoys a superior intrinsic activity [33], [48]. A full water electrooxidation reaction of the two electrodes will proceed when the voltages are over 1.50 and 1.46 V (vs RHE), respectively. Besides, the 3D Nyquist curves exposed a faster decrease in the semiarc of NiFe-LDH/NF-W as the potential increase (Figure S11), suggesting a higher rate of charge transfer within it than NiFe-LDH/NF-H (Figure S13) [33]. Besides, in situ Raman spectroscopy was performed to further track the evolution of the electrode surface during the water oxidation. As displayed in Fig. 4c, the relative intensity of Raman peaks between 470, 540, and 680 cm−1 are increased with the elevated working potential, revealing an electrochemically induced surface reconstruction occurred on the NiFe-LDH/NF-H during the water oxidation [49]. Alternatively, the relative intensity changes of Raman peaks on NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode varied little, which verifies that the surface partial reconstruction induced by the ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction can effectively avoid the occurrence of electrochemical reconstruction (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the initial NiFe-LDH and reconstructed NiFeOOH models are constructed to calculate the Gibbs free energies (ΔG) of the reaction intermediates (*OH, *O, and *OOH) on their surface using the density functional theory (DFT) method (Fig. 4g) [21], [40]. As demonstrated in Fig. 4h, the rate-determining steps of water oxidation for NiFe-LDH and NiFeOOH are the formation of *O, which aligns well with the findings obtained through the Tafel analysis (Fig. 3c). A smaller highest ΔG value change of 1.85 eV for NiFeOOH than NiFe-LDH (2.17 eV) indicates a higher intrinsic catalytic activity. The LSV curves under temperature-dependent are tested to evaluate the OER activation energy (Ea) according to the Arrhenius formula (Figure S14) [12], [22], [50]. As displayed in Fig. 4i, at the OER initial phase of η = 270 mV, the Ea value of NiFe-LDH/NF-W (18.52 kJ mol−1) is lower than that of NiFe-LDH/NF-H (19.23 kJ mol−1), which reveals that NiFe-LDH/NF-W can easier overcome the surface reconstruction thermodynamics barrier and proceeding with the water oxidation reaction. Afterward, the Ea of NiFe-LDH/NF-W exhibits a faster decrease and lower values compared to the NiFe-LDH/NF-H under the higher overpotentials (η = 320, 360, and 400 mV) (Figures S15 and 4j). These results as schematic illustrated in Fig. 4k that the ultrasonic process lowers the surface reconstruction barrier from NiFe-LDH to NiFeOOH thereby boosting the subsequent OER procedure.

Fig. 4.

Evolution analysis of the NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W during the water oxidation. (a and d) The 6th harmonic FTACV curves. (b and e) The operando 2D contour Bode plots. (c and f) In situ Raman spectroscopy measurements at varying applied voltages (V vs. Ag/AgCl). (g) Top-down views of the models depicting the adsorbed intermediates (*OH, *O, and *OOH). (h) The calculated Gibbs free-energy diagram. (i) Arrhenius plots of the kinetic currents at η = 270 mV, (j) activation energy (Ea) obtained at various overpotentials, and (k) schematic illustration of Ea.

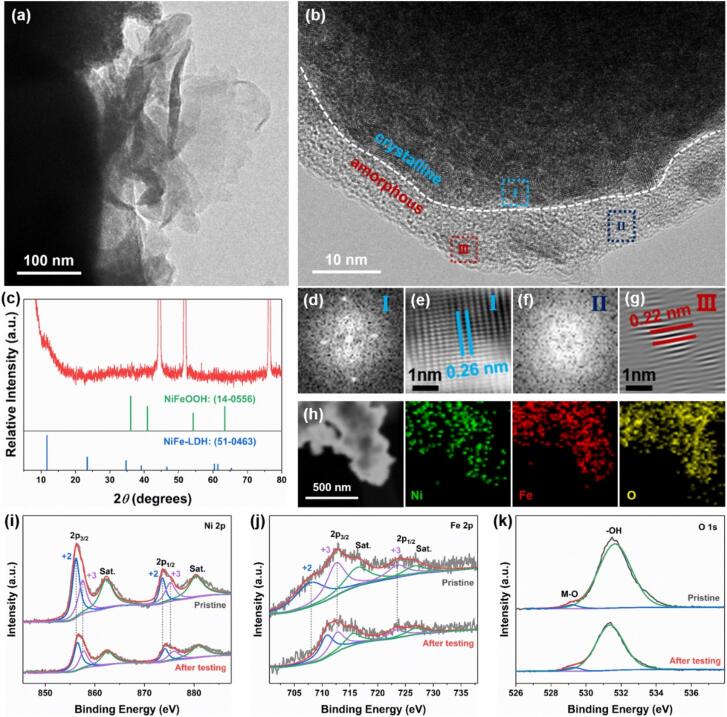

3.6. Characterizations of the NiFe-LDH/NF-W after stability testing

To further corroborate the inevitable surface reconstruction induced by electrochemistry during the water oxidation, the NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode after stability testing is comprehensively characterized. SEM image shows that its wall-like interconnected nanosheet structure is well maintained (Fig. 5a). Besides, the HRTEM image (Fig. 5b) and FFT diffraction patterns (Fig. 5d and f) demonstrate that a crystalline-amorphous structure at the edge of the nanosheets is formed. The inverse-FFT image for the crystalline region Ι shows an interplanar spacing of 0.26 nm corresponding to the (0 1 2) plane of NiFe-LDH (Fig. 5e), whereas the crystalline region Ⅲ embedded in the amorphous matrix shows the interplanar spacing of 0.22 nm corresponding to the (1 0 1) plane of NiFeOOH (Fig. 5g). Combined with the XRD result indicates that only partial surface reconstruction occurs (Fig. 5c), and it primarily appears as an amorphous. The valence states of uniform dispersed Ni, Fe, and O elements on its surface (Fig. 5h) are analyzed by the XPS measurement. As displayed in Fig. 5i, after OER testing, both Ni2+ and Ni3+ binding energies in Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 have a 0.2 eV positive shift contrast to its pristine. In addition, the Fe2+ peak in Fe 2p3/2 region almost disappears, and the formation of its higher valence (Fig. 5j). The peak of the metal–oxygen bond located at 529.3 eV in the O 1 s spectrum has a slightly negative shift (Fig. 5k). A similar phenomenon is also observed in the XPS spectra of the NiFe-LDH/NF-H electrode (Figure S16). These results reveal a consensus as previous reports that electrochemically induced surface reconstruction is inevitable for NiFe-LDH during the OER process [11], [50]. Therefore, lowering the surface reconstruction barrier by ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction synthesis strategy can markedly improve the OER activity of NiFe-LDH catalysts.

Fig. 5.

Characterizations of NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode after durability measuring. (a) TEM image, (b) HRTEM image, (c) XRD pattern, (d and f) FFT diffraction patterns, and (e and g) inverse-FFT images for the labeled areas Ι and ΙΙ in panel b, respectively. (h) HAADF-STEM image alongside its corresponding elemental mappings. XPS spectra of (i) Ni 2p, (j) Fe 2p, and (k) O 1 s.

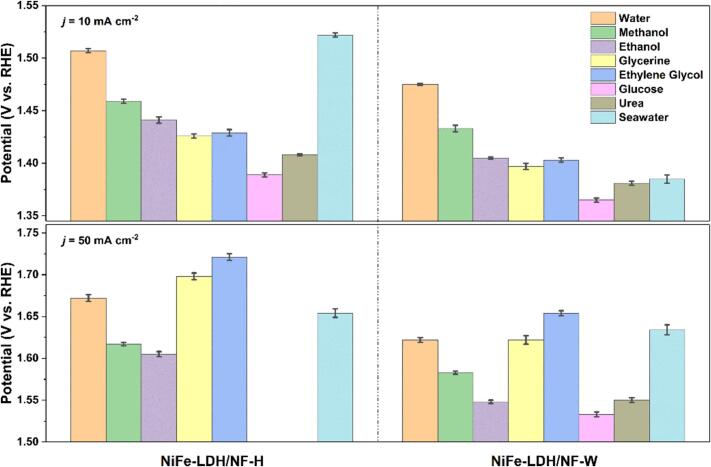

3.7. Organics electrooxidation reactions

Replacement of the sluggish OER with organics molecule electrooxidation reactions (EORs) that are more thermodynamically favorable is another effective strategy to decrease the energy consumption of H2 production [51]. On the other hand, alcohols (methanol, ethanol) and urea oxidation reactions can be applied in direct fuel cells [52], [53], [54]; large molecular alcohols oxidation reactions, such as ethylene glycol, glycerine, and glucose, can be utilized to produce high value-added products [55], [56]. Interestingly, Ni-based LDHs have demonstrated their proficiency not only in exhibiting outstanding performances for OER but also for EORs [51], and the reconstructed (oxy)hydroxides are regarded as their active species [57], [58]. Therefore, the surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode is employed to perform various organics EORs and seawater in 1 M KOH (Figures S17-S24). The NiFe-LDH/NF-W manifests higher EORs activities than NiFe-LDH/NF-H for methanol, ethanol, glycerol, ethylene glycol, glucose, urea, and seawater. Besides, as displayed in Fig. 6, EORs potentials (1.433, 1.405, 1.397, 1.403, 1.365, 1.381, and 1.385 V vs RHE) of NiFe-LDH/NF-W are lower than OER potential (1.475 V) at the j of 10 mA cm−2. Nevertheless, higher EORs potentials for glycerol and ethylene glycol than OER were obtained at the j of 50 mA cm−2. The reason can be attributed to large molecular alcohols with higher viscosity slowing the EORs kinetics [53], [56]. On the other side, superior EORs activities are achieved for the soluble organic molecules. As an example, electrooxidation of glucose only needs 1.365 and 1.553 V to obtain j of 10 and 50 mA cm−2, which is lower than 110 and 69 mV than water oxidation, respectively. Therefore, coupling the H2 evolution reaction with soluble organics electrooxidation reactions utilizing our NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode would further reduce its energy consumption.

Fig. 6.

The applied potentials of various organics EORs at j = 10 and 50 mA cm−2 on the NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes.

4. Conclusion

In summary, a surface partially reconstructed NiFe-LDH nanosheets directly grown on Ni foam surfaces (NiFe-LDH/NF-W) is synthesized through a novel ultrasonic-assisted Fenton reaction synthesis strategy. The low-spin states of Ni2+ () and Fe2+ () on the NiFe-LDH surface transform into high-spin states of Ni3+ () and Fe3+ () and formation of the highly active species of NiFeOOH. In situ Raman spectroscopy and operando EIS combined with the temperature-dependent LSV curves indicate that the ultrasonic process lowers the reconstruction activation energy (Ea) barrier and thereby facilitates the reconstructed process from NiFe-LDH to NiFeOOH. The NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrode not only shows superior activity for water oxidation but also for various organics (including methanol, ethanol, glycerol, ethylene glycol, glucose, and urea) electrooxidation, which delivers 10 mA cm−2 only needing potentials of 1.465, 1.433, 1.405, 1.397, 1.403, 1.365, 1.381, and 1.385 V vs RHE, respectively. This work will further promote the application of NiFe-LDH materials in the electrolysis of water to produce hydrogen, fuel cells, and electric organic synthesis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shanfu Sun: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Tianliang Wang: Formal analysis. Ruiqi Liu: Methodology. Zhenchao Sun: Formal analysis. Xidong Hao: Visualization. Yinglin Wang: Conceptualization. Pengfei Cheng: Visualization. Lei Shi: Supervision. Chunfu Zhang: Supervision. Xin Zhou: Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22205169, 62271378, 62371375, and 62071363), National Key Research and Development Program (Nos. 2021YFC3090400 and 2021YFC3090402), Shaanxi Province Key Research and Development Program (No. 2024GX-YBXM-332), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2023M742734 and 2024T170694), Shaanxi Province Postdoctoral Research Project Funding (No. 2023BSHYDZZ93), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. ZYTS24065), Ministry of Public Security Science and Technology Program Projects (No. 2022ZB40), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Plan Project (Nos. 2023YFSH0027, 2020GG0185, 2021GG0160 and 2022YFHH0073), Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (No. 2023-JC-YB-506), Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (No. 2022TD-37). Thanks eceshi (www.eceshi.com) for the ICP-MS and Shiyanjia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com) for the VSM analysis.

Footnotes

Fig. S1-S24 show the EPR spectrum, SEM images, EDX spectra, LSV curves, Chronoamperometry tests, CV curves, FTACV results, 3D Bode plots, Nyquist plots, temperature-dependent LSV curves, XPS spectra, and various organics electrooxidation measurements of NiFe-LDH/NF-H and NiFe-LDH/NF-W electrodes. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.107027.

Contributor Information

Shanfu Sun, Email: sunshanfu@xidian.edu.cn.

Pengfei Cheng, Email: pfcheng@xidian.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zheng H., Wang S., Liu S., Wu J., Guan J., Li Q., Wang Y., Tao Y., Hu S., Bai Y., Wang J., Xiong X., Xiong Y., Lei Y. The heterointerface between Fe1/NC and selenides boosts reversible oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023;33:2300815. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202300815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Zhang M., Liu Y., Zheng Z., Liu B., Chen M., Guan G., Yan K. Recent advances on transition-metal-based layered double hydroxides nanosheets for electrocatalytic energy conversion. Adv. Sci. 2023;10:2207519. doi: 10.1002/advs.202207519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L., Wang Y., Zhao Z., Wang Y., Li Q., Wang Q., Tang Y., Lei Y. Trimetallic oxyhydroxides as active sites for large-current-density alkaline oxygen evolution and overall water splitting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022;110:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2021.08.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panahi A., Ghanbari M., Dawi E., Monsef R., Abass R., Aljeboree A., Salavati-Niasari M. Simple sonochemical synthesis, characterization of TmVO4 nanostructure in the presence of Schiff-base ligands and investigation of its potential in the removal of toxic dyes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X., Wang Y., Wu Z. Design principle of electrocatalysts for the electrooxidation of organics. Chem. 2022;8:2594–2629. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y., Zhang T., Mao Y., Wang J., Sun C. Highly efficient bifunctional layered triple Co, Fe, Ru hydroxides and oxides composite electrocatalysts for Zinc-Air batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023;935 doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2023.117315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Chen Z., Zhang M., Liu Y., Luo H., Yan K. Green fabrication of nickel-iron layered double hydroxides nanosheets efficient for the enhanced capacitive performance, Green. Energy Environ. 2022;7:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.gee.2021.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han J., Meng X., Lu L., Wang Z., Sun C. Triboelectric nanogenerators powered electrodepositing tri-functional electrocatalysts for water splitting and rechargeable zinc-air battery: A case of Pt nanoclusters on NiFe-LDH nanosheets. Nano Energy. 2020;72 doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang T., Huang H., Han J., Yan F., Sun C. Manganese-doped hollow layered double (Ni, Co) hydroxide microcuboids as an efficient electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. ChemElectroChem. 2020;7:3852–3858. doi: 10.1002/celc.202001138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y., Wang X., Zhu X., Wu Z., Zhao D., Wang F., Sun D., Tang Y., Li H., Fu G. Improving the oxygen evolution activity of layered double-hydroxide via erbium-induced electronic engineering. Small. 2023;19:2206531. doi: 10.1002/smll.202206531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao L., Cui X., Sewell C.D., Li J., Lin Z. Recent advances in activating surface reconstruction for the high-efficiency oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:8428–8469. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00962h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun S., Jin X., Cong B., Zhou X., Hong W., Chen G. Construction of porous nanoscale NiO/NiCo2O4 heterostructure for highly enhanced electrocatalytic oxygen evolution activity. J. Catal. 2019;379:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2019.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang T., Bian J., Zhu Y., Sun C. FeCo nanoparticles encapsulated in N-doped carbon nanotubes coupled with layered double (Co, Fe) hydroxide as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for rechargeable Zinc-Air batteries. Small. 2021;17:2103737. doi: 10.1002/smll.202103737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng X., Han J., Lu L., Qiu G., Wang Z., Sun C. Fe2+-doped layered double (Ni, Fe) hydroxides as efficient electrocatalysts for water splitting and self-powered electrochemical systems. Small. 2019;15:1902551. doi: 10.1002/smll.201902551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Y., Wang H., Peng C., Bu L., Chiang C., Tian K., Zhao Y., Zhao J., Lin Y., Lee J., Gao L. Co-induced electronic optimization of hierarchical NiFe LDH for oxygen evolution. Small. 2020;16:2002426. doi: 10.1002/smll.202002426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Li L., Shi J., Xie M., Nie J., Huang G., Li B., Hu W., Pan A., Huang W. Oxygen defect engineering promotes synergy between adsorbate evolution and single lattice oxygen mechanisms of OER in transition metal-based (oxy)hydroxide. Adv. Sci. 2023;10:2303321. doi: 10.1002/advs.202303321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M., Li H., Jiang X., Jiang M., Zhan X., Fu G., Lee J., Tang Y. Gd-induced electronic structure engineering of a NiFe-layered double hydroxide for efficient oxygen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:2999–3006. doi: 10.1039/d0ta10740a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou H., Li Z., Xu S., Lu L., Xu M., Ji K., Ge R., Yan Y., Ma L., Kong X., Zheng L., Duan H. Selectively upgrading lignin derivatives to carboxylates through electrochemical oxidative C(OH)−C bond cleavage by a Mn-doped cobalt oxyhydroxide catalyst. Angew. Chem. 2021;133:9058–9064. doi: 10.1002/ange.202015431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X., Ni K., Wen B., Guo R., Niu C., Meng J., Li Q., Wu P., Zhu Y., Wu X., Mai L. Deep reconstruction of nickel-based precatalysts for water oxidation catalysis. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4:2585–2592. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.9b01922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X., Guo R., Ni K., Xia F., Niu C., Wen B., Meng J., Wu P., Wu J., Wu X., Mai L. Reconstruction-determined alkaline water electrolysis at industrial temperatures. Adv. Mater. 2020;32:2001136. doi: 10.1002/adma.202001136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun S., Zheng M., Cheng P., Wu F., Xu L. Porous bimetallic cobalt-iron phosphide nanofoam for efficient and stable oxygen evolution catalysis. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2022;626:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun S., Zhou X., Cong B., Hong W., Chen G. Tailoring the d-band centers endows (NixFe1−x)2P nanosheets with efficient oxygen evolution catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020;10:9086–9097. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c01273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kresse G., Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558–561. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kresse G., Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758–1775. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perdew J.P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Z., Wang J., Dong S., Wang L., Li L., Cao Z., Zhang Y., Cheng L., Yang J. Ultrasonic controllable synthesis of sulfur-functionalized metal–organic frameworks (S-MOFs) and their application in piezo-photocatalytic rapid reduction of hexavalent chromium (Cr) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;107 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.106912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H., Chen Z., Shang Y., Lv C., Zhang X., Li F., Huang Q., Liu X., Liu W., Zhao L., Ye L., Xie H., Jin X. Boosting carrier separation on a BiOBr/Bi4O5Br 2 direct Z-scheme heterojunction for superior photocatalytic nitrogen fixation. ACS Catal. 2024;14:5779–5787. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.3c06169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang P., Liu X., Wang Y., Zheng H., Wang J., Zheng J., Liu M., Deng D., Bai Y., Chen Y., Zhang T., Liu Z., Lei Y. Weatherability and heat resistance enhanced by interaction between AG25 and Mg/Al-LDH. Rare. Met. 2024;43:2758–2768. doi: 10.1007/s12598-023-02605-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang C., Zou P., Nairan A., Zhang Y., Liu J., Liu K., Hu S., Kang F., Fan H., Yang C. Exceptional performance of hierarchical Ni–Fe oxyhydroxide@NiFe alloy nanowire array electrocatalysts for large current density water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:86–95. doi: 10.1039/C9EE02388G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun S., Yin Z., Cong B., Hong W., Zhou X., Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen G. Crystalline carbon modified hierarchical porous iron and nitrogen co-doped carbon for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 2021;594:864–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T., Hu Y., Liu K., Yin J., Li Y., Fu G., Zhang Y., Tang Y. Hollow yolk-shell nanoboxes assembled by Fe-doped Mn3O4 nanosheets for high-efficiency electrocatalytic oxygen reduction in Zn-Air battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;427 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z., Wu X., Jiang X., Shen B., Teng Z., Sun D., Fu G., Tang Y. Surface carbon layer controllable Ni3Fe particles confined in hierarchical N-doped carbon framework boosting oxygen evolution reaction. Advanced Powder Materials. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.apmate.2021.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Z., Meng Z., Gong X., Hao Z., Li X., Sun H., Hu X., Yu S., Tian H. Rapid surface reconstruction of pentlandite by high-spin state iron for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. 2024;136:e202317022. doi: 10.1002/anie.202317022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han H., Choi H., Mhin S., Hong Y., Kim K., Kwon J., Ali G., Chung K., Je M., Umh H., Lim D., Davey K., Qiao S., Paik U., Song T. Advantageous crystalline–amorphous phase boundary for enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:2443–2454. doi: 10.1039/C9EE00950G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z., Song Y., Cai J., Zheng X., Han D., Wu Y., Zang Y., Niu S., Liu Y., Zhu J., Liu X., Wang G. Tailoring the d-band centers enables Co4N nanosheets to be highly active for hydrogen evolution catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5076–5080. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song Q., Li J., Wang S., Liu J., Liu X., Pang L., Li H., Liu H. Enhanced electrocatalytic performance through body enrichment of Co-based bimetallic nanoparticles in situ embedded porous N-doped carbon spheres. Small. 2019;15:1903395. doi: 10.1002/smll.201903395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun S., Sun G., Cheng P., Liu R., Zhang C. iRs-corrections induce potentially misjudging toward electrocatalytic water oxidation. Mater. Today Energy. 2023;32 doi: 10.1016/j.mtener.2023.101246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan K., Chen H., Ji Y., Huang H., Claesson P.M., Daniel Q., Philippe B., Rensmo H., Li F., Luo Y., Sun L. Nickel–vanadium monolayer double hydroxide for efficient electrochemical water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11981. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith R.D., Fagan R.D., Trudel S., Berlinguette C.P., Prevot M.S. Water oxidation catalysis: Electrocatalytic response to metal stoichiometry in amorphous metal oxide films containing iron, cobalt, and nickel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11580–11586. doi: 10.1021/ja403102j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun S., Lv C., Hong W., Zhou X., Wu F., Chen G. Dual tuning of composition and nanostructure of hierarchical hollow nanopolyhedra assembled by NiCo-layered double hydroxide nanosheets for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019;2:312–319. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b01318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang P., Liu X., Liu Z., Zhang T., Zheng H., Ou H., Wang Y., Bai Y., Liu M., Deng D., Wang J., Chen Y., Zheng H., Jiang J., Lei Y. Hyperspectral and weather resistant biomimetic leaf enabled by interlayer confinement. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024:2405908. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202405908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suen N., Hung S., Quan Q., Zhang N., Xu Y.J., Chen H.M. Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:337–365. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00328A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adamson H., Bond A.M., Parkin A. Probing biological redox chemistry with large amplitude Fourier transformed ac voltammetry. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:9519–9533. doi: 10.1039/C7CC03870D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J., Li H., Yu Z., Liu C., Yuan Z., Wang C., Zhao S., Henkelman G., Li S., Wei L., Chen Y. Octahedral coordinated trivalent cobalt enriched multimetal oxygen-evolution catalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020;10:2002593. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202002593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu Z., Xu W., Zhu W., Yang Q., Lei X., Liu J., Li Y., Sun X., Duan X. Three-dimensional NiFe layered double hydroxide film for high-efficiency oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:6479–6482. doi: 10.1039/C4CC01625D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohammed-Ibrahim J. A review on NiFe-based electrocatalysts for efficient alkaline oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources. 2020;448 doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.227375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang N., Hu Y., An L., Li Q., Yin J., Li J., Yang R., Lu M., Zhang S., Xi P., Yan C. Surface activation and Ni-S stabilization in NiO/NiS2 for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202207217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao S., Hu F., Yin L., Li L., Peng S. Manipulating electron redistribution induced by asymmetric coordination for electrocatalytic water oxidation at a high current density. Sci. Bull. 2023;68:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2023.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin X., Wang Z., Cao S., Hu Y., Liu S., Chen X., Chen H., Zhang X., Wei S., Xu H., Cheng Z., Hou Q., Sun D., Lu X. Bioinspired trimesic acid anchored electrocatalysts with unique static and dynamic compatibility for enhanced water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:6714. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42292-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang M., Dong C., Huang Y., Li Y., Shen S. Electronic structure evolution in tricomponent metal phosphides with reduced activation energy for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Small. 2018;14:1801756. doi: 10.1002/smll.201801756. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0021-9517(19)30440-3/h0285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song Y., Ji K., Duan H., Shao M. Hydrogen production coupled with water and organic oxidation based on layered double hydroxides. Exploration. 2021;1:20210050. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen S.T., Law H.M., Nguyen H.T., Kristian N., Wang S., Chan S.H., Wang X. Enhancement effect of Ag for Pd/C towards the ethanol electro-oxidation in alkaline media. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009;91:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang J., Wang W., Wu D., Xu F., Jiang K., Guo Y., Gao Z. Self-supported amorphous phosphide catalytic electrodes for electrochemical hydrogen production coupling with methanol upgrading. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 2023;648:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.05.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serov A., Kwak C. Direct hydrazine fuel cells: A review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010;98:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou H., Ren Y., Li Z., Xu M., Wang Y., Ge R., Kong X., Zheng L., Duan H. Electrocatalytic upcycling of polyethylene terephthalate to commodity chemicals and H2 fuel. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4679. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang J., Song F., Hou Y., Wu D., Xu F., Jiang K., Gao Z. Molybdenum, tungsten doped cobalt phosphides as efficient catalysts for coproduction of hydrogen and formate by glycerol electrolysis. J. Colloid Inter. Sci. 2024;665:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2024.03.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang Y., Chong X., Liu C., Liang Y., Zhang B. Boosting hydrogen production by anodic oxidation of primary amines over a NiSe nanorod electrode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:13163. doi: 10.1002/ange.201807717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen W., Xu L., Zhu X., Huang Y.C., Zhou W., Wang D., Zhou Y., Du S., Li Q., Xie C., Tao L., Dong C., Wang Y., Chen R., Su H., Chen C., Zou Y., Li Y., Liu Q., Wang S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:7297. doi: 10.1002/anie.202015773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.