Abstract

Background:

Despite the universal nature of postpartum vaginal bleeding after childbirth and the importance of managing vaginal bleeding in the postpartum period to monitor health status, little is known about the information or products that birthing individuals are provided. Investigating current practices may offer insights to enacting more supportive and equitable postpartum care.

Objective:

To evaluate the patterns and content of vaginal bleeding counseling provided to birthing parents while on a postnatal inpatient unit.

Design:

Observational study of inpatient postpartum care. Birthing parents and their companions consented to video and audio recording of themselves, their infants, and healthcare team members during their postnatal unit stay.

Methods:

Following IRB approval and in coordination with clinicians at a tertiary hospital in the southeastern United States, data were collected with 15 families from August to December 2020. A multidisciplinary team coded video and audio data from each family from 12 h before hospital discharge. This analysis evaluates patterns of vaginal bleeding counseling timing, content, and language concordance and thematic content of this communication.

Results:

Birthing parent participants were self-identified Hispanic White (n = 6), non-Hispanic Black (n = 5), non-Hispanic White (n = 3), and non-Hispanic multi-race (n = 1). Six were Spanish-speaking and eight had cesarean section births. The timing, content, and language concordance of vaginal bleeding communication varied, with these topics mainly addressed in the hour preceding discharge. Twelve of the 15 birthing parents had communication on these topics between 2 and 5 times, 2 had one exchange, and 1 had no counseling on postpartum bleeding observed. Four of the six Spanish-speaking birthing parents had counseling on these topics that was not language concordant. Postpartum vaginal bleeding management involved the themes of access to products, patient safety, and meaningful counseling. There was a lack of adequate access, variation in accurate and respectful care, and a busy clinical environment with differences in information provided.

Conclusion:

Findings suggest that there are opportunities to strengthen clinical practices for more consistent, proactive, and language concordant vaginal bleeding and subsequent menstrual care postpartum. Menstrual equity is an important part of dignified and safe care.

Keywords: postpartum, menstrual equity, counseling, language concordance, patient safety

Plain language summary

Video analysis of when and what information on vaginal bleeding was shared between people who just gave birth and their healthcare team at the hospital.

Why did we do the study? After birth, people must take care of vaginal bleeding. It is important for people in the hospital to recognize warning signs for too much bleeding, have access to pads, and feel supported by their healthcare team before discharging to home. There has been little research on experiences with inpatient counseling on postpartum vaginal bleeding—a part of the reproductive life cycle—for new parents. We wanted to watch and listen in hospital rooms so we could think about the best ways for healthcare providers to talk about vaginal bleeding. What did we do? We asked 15 people who just gave birth, people staying with them at the hospital, and their healthcare team if we could video and sound record in their hospital rooms. They could start and stop recording anytime. We only recorded people who agreed to be in the study. What did we learn? We watched recordings of the last 12 hours at the hospital before each family went home. We found that most of the time, the healthcare workers did not talk about vaginal bleeding. People who spoke Spanish did not always have someone interpreting into their language. Sometimes family members had to translate and ask for pads. Some people did not have enough pads or underwear and had to wait after asking for more. What does it mean? We found ways to improve teaching about vaginal bleeding after birth. We recommend always having an interpreter when needed, giving people enough pads and underwear in their rooms, including companions in the teaching, and having enough healthcare workers to answer requests. These ideas would improve the counseling and give everyone the support needed after giving birth.

Introduction

Access to menstrual products and vaginal bleeding counseling in the early postpartum period is an important component of ensuring menstrual equity across the reproductive life cycle.1 –3 Menstrual equity is most recognized as access to affordable and safe menstrual care products, to safe and private spaces to manage bleeding, and to adequate menstruator knowledge on this biological process, with resources to enable their agency. 1 Much of the literature on menstrual equity, however, focuses on global adolescents, excluding other similarly challenging experiences of physiological vaginal bleeding, such as vaginal bleeding after birth.3,4 Those studies addressing menstrual equity in the adult United States population have focused on menstruators facing homelessness, incarceration, and in educational settings.4 –8 Little is known regarding current vaginal bleeding counseling and management following childbirth for people living in the United States, despite lochia being a universal aspect of postpartum recovery, 9 the significant role of bleeding in maternal morbidity and mortality, 10 and the shared challenges regarding supplies and safety managing monthly and postpartum vaginal bleeding. 3

Birthing parents require timely access to appropriate menstrual products during their inpatient postpartum stay and beyond, for dignified and safe care. The need for clear communication on vaginal bleeding, menstrual supplies, and maternal health warning signs during the postpartum hospital stay is highly acute.9,11 Being informed about typical postpartum lochia—defined as vaginal discharge after birth—and thresholds of postpartum bleeding concern in the days and weeks after either vaginal or cesarean section birth requires clear, meaningful communication with the healthcare team.9,10 Furthermore, when birthing parents are healing from vaginal or perineal lacerations, pad changes for management and hygiene can irritate healing wounds and be painful. 12 Despite the impact of lochia management on new parent wellbeing, there are limited studies assessing vaginal bleeding counseling, supplies, and management support provided by healthcare team members during the early postpartum period. 13

The postpartum unit is a complex environment, in which medical practice guidelines do not always appropriately align with birthing parents’ needs.2,11 In a qualitative study on postpartum experiences, birthing parents described a lack of comprehensive discharge education and challenges with ensuring support. 14 Birthing parents reported feeling guilty asking for pads and underwear, reflecting feelings of being burdensome. 14 They also report frustration with their dependency on staff, who often appear extremely busy and rushed in their communication.2,14 Additionally, although language concordant care in clinical services is mandated by federal law and is essential to ethical practice, there is variability in interpretation service utilization for Spanish-speaking individuals on the postnatal unit. 15 Lack of concordant language access can negatively impact the quality and content of the discharge counseling, and likely leaves bleeding management needs unmet, particularly for the most vulnerable patients. 15

The purpose of this aspect of an observational study of inpatient postpartum care was to observe the patterns and content of verbal communication addressing vaginal bleeding as part of childbirth hospitalization. Understanding patterns of postpartum vaginal bleeding communication on the postnatal unit can inform clinical strategies for adherence to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) patient safety bundles on both obstetric hemorrhage and the postpartum discharge transition. 16 The ACOG postpartum discharge transition patient safety change package includes providing ongoing education to all patients on early warning signs and risk for postpartum complications and ensuring patients have access to essential hygiene supplies for managing postpartum vaginal bleeding. 13

Methods

This analysis evaluates patterns of vaginal bleeding counseling timing, content, and language concordance and thematic content of the verbal communication, as part of a larger observational research study that involved filming inpatient postpartum care. The parent study was designed to explore observed practices and interactions, with a predetermined sample size of 15 birthing parent–infant couplets. This manuscript follows STROBE reporting criteria. 17

Participants

Birthing parents and companions provided informed, written consent for their participation and permission of their infants to participate in the filming research project on the postnatal unit between August and December 2020. Inclusion criteria included: age over 18 years old, fluency in English or Spanish, recruitment between 6 and 24 h postpartum, a liveborn singleton who was rooming-in, and access to a phone or computer. We purposefully recruited the sample for birthing parent racial and language diversity. Potential participants were excluded if they were incarcerated at the time of delivery, were planning for adoption, or had a positive COVID-19 test result (including companion or infant). Participants received a $100 gift card following study participation, as thanks for their many hours of data collection. Data collection occurred at a single institution in the southeastern United States while COVID-19 regulations were in place in the postnatal unit, which only permitted one companion to be present and no visitors. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Biomedical Institutional Review Board (#19-1900).

Study procedures

After family enrollment, a bilingual research staff member who was a native Spanish-speaker set up video equipment in their postnatal unit room. An Axis Companion Recorder and two Axis Companion Cube L cameras (Axis Communications AB, Lund, Sweden) were specifically configured for this study. This equipment recorded continuous audio and video, including infrared illumination for low light conditions, locally to the recorder box. Both cameras were wired directly to the video recorder box using ethernet patch cables. The two cameras were mounted using clamps to a rail behind the participant’s bed as well as to a shelf on the wall directly opposite the participant’s headboard, ensuring that two vantage points were collected in the postnatal unit room. Instructions were provided verbally and in writing to participants in their preferred language/s (English or Spanish) on how to turn off and turn back on the cameras if they desired. A sign was posted on the participant’s door that recording was in progress for healthcare team members. Research staff also partnered with postpartum nursing staff to ensure that clinicians were aware of the recording and could contact research staff for any reason. Two senior study team members also worked on the postnatal unit and facilitated project coordination with healthcare team members. After each participant was discharged, nursing staff alerted research staff to remove the video equipment after the participant had left their room. The videos were then downloaded and stored on a secure server.

Analysis

Video coding was performed by multidisciplinary research team members using a study-developed behavioral taxonomy, with codes, definitions, and clarifying information. An example is the code “health care team member/s present and speaking,” defined as one or more healthcare team member physically within the postnatal unit room and they were observed speaking to a birthing parent or companion at any time during a 5-min segment. Clarifying information was that it was also coded as occurring if a healthcare team member was outside of the room (such as in the postnatal unit hallway) and communicating with the birthing parent or companion. A total of 166 h of the 12-h prior to discharge observation period were double coded for behaviors in 5-min increments, with inter-rater reliability for each variable (κ > 0.70 controlling for chance), evaluated using R statistical software. 18

The quantitative coding included verbal communication with healthcare team members, birthing parents, and companions within each 5-min segment, distinguishing topics addressed by speaker. Language spoken when healthcare team members were present was coded as: English spoken, Spanish spoken with short words, Spanish spoken in sentences without interpretation services, Spanish spoken with interpretation services (in-person interpreter, phone, tablet), and/or companion interprets. When Spanish was spoken in sentences without interpretation services, the audio was analyzed further by a native Spanish-speaking research team member for logic and grammar. Coders met weekly as a group to discuss behavioral and topic coding to address any uncertainties and to resolve discrepancies by consensus with the senior author (KPT). The coded datasets were checked, with any missing information or inconsistencies corrected by review of the original video–audio in coordination with KPT. Verbal communication was categorized as language concordant when a healthcare team member spoke English with an English-speaking birthing parent, a healthcare team member spoke in sentences in Spanish without errors with a Spanish-speaking birthing parent, or when interpretation services were utilized with a Spanish-speaking birthing parent. The communication was considered as language discordant when a healthcare team member spoke English with a Spanish-speaking birthing parent, a healthcare team member Spanish with a Spanish-speaking birthing parent with words or short phrases only, a healthcare team member spoke in sentences in Spanish with errors with a Spanish-speaking birthing parent, or a companion interpreted information from a healthcare team member from English to Spanish for a Spanish-speaking birthing parent).

Through the process of quantifying behaviors (creating counts of codes) and the timing of topics verbally addressed, the research team (including native Spanish-speakers, clinicians, and non-clinicians) transcribed and wrote notes of the observations. The quantitative data were organized in a spreadsheet and the qualitative data were recorded in a document, both by participant IDs and timestamps in 5-min increments. The vaginal bleeding related content of the qualitative data were inductively coded by two team members (SMD and KECM), to categorize interactions when healthcare team members were present in the postnatal unit rooms and a clinician, birthing, parent, and/or companion spoke about any of the following keywords: bleeding/hemorrhage uterine contractions/cramps, pads, supplies, underwear, vaginal care, witch hazel or Tucks pads, or bleeding-related warning signs. After familiarization with the data and creating memos, the authors reviewed the video and audio files as needed to clarify details of the recorded verbal communication and observed context, and iteratively developed themes. 19 Qualitative data saturation was reached through this process when the team members determined that no new codes were emerging.

Results

One hundred two individuals who met inclusion criteria were approached. Of these, 16 birthing parents consented to participate. Fifteen families were filmed (one was not filmed due to a technical error with the recording equipment). All participating families included a filmed companion. Six birthing parents self-identified as Hispanic white and Spanish-speaking, five identified as non-Hispanic Black, three identified as non-Hispanic white, and one identified as non-Hispanic multi-race (Table 1). The average length of recording was 31 h (ranging from 10 to 76 h). Six of the 15 recordings included the recording equipment being turned off at least once during the 12 h prior to discharge, with missing data for at least 30 min out of hour-long segments for 5 participants (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Filmed participant characteristics (N = 15).

| Birthing parent and infant characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Birthing parent ethnicity and race | |

| Hispanic White | 6 (40) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 (33) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3 (20) |

| Non-Hispanic multi-race | 1 (7) |

| Birthing parent preferred language | |

| English | 9 (60) |

| Spanish | 6 (40) |

| Birthing parent age | |

| 18–24 years old | 2 (13) |

| 25–34 years old | 9 (60) |

| 35 years or older | 4 (27) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparas | 7 (47) |

| Multiparous | 8 (53) |

| Infant’s gestational age at delivery | |

| 34 + 0 to 36 + 6 weeks | 2 (13) |

| 37 + 0 to 39 + 6 weeks | 10 (67) |

| 40 weeks or more | 3 (20) |

| Type of birth | |

| Cesarean section | 8 (53) |

| Vaginal | 7 (47) |

| Dyad length of stay in postpartum unit | |

| 24 h or less | 1 (7) |

| 25–48 h | 3 (20) |

| 49–72 h | 10 (67) |

| 73 h or more | 1 (7) |

| Method of infant feeding in postpartum unit | |

| Human milk and formula | 8 (53) |

| Human milk | 6 (40) |

| Formula | 1 (7) |

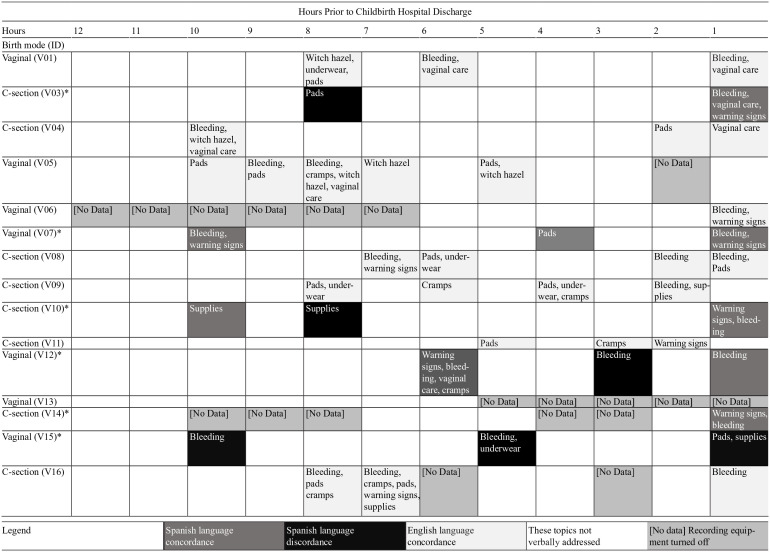

Figure 1.

The timing, content, and language concordance of vaginal bleeding verbal communication among healthcare team members, birthing parents and companions as filmed during the 12 h of inpatient postpartum care prior to hospital discharge.

*Spanish-speaking birthing parents.

The timing, content, and language concordance of vaginal bleeding communication as filmed during the 12 h of inpatient postpartum care prior to discharge varied (Figure 1), with the topics mostly addressed in the hour preceding discharge. Twelve of the 15 birthing parents had communication on these topics between 2 and 5 times, 2 had one exchange, and 1 had none observed. Four of the six Spanish-speaking birthing parents had counseling on these topics that was not language concordant. For one of these Spanish-speaking individuals, each instance of verbal communication on from their healthcare team on vaginal bleeding related topics was not language concordant (V15). Vaginal bleeding related counseling occurred in the last hour prior to hospital discharge for 11 of the 15 birthing parents, with missing data during this time for 1 participant (Figure 1).

Three themes emerged during content analysis of postpartum vaginal bleeding communication in the inpatient setting: Access to products, Patient safety, and Meaningful counseling. Within these themes were several underlying components, including language concordant counseling, the timing of staff responses to birthing parent requests, options of products, the role of companions, the hospital room environment, and transitioning to home and community.

Access to products: lack of adequate maternal access to menstrual hygiene products on the postnatal unit and through hospital discharge

An adequate quantity of pads was not always accessible during the inpatient postpartum stay, with five birthing parents requesting products from their healthcare team during the observations. Two birthing parents specifically discussed the number of pads available, if any, and shared concerns on quantity and quality of pads brought to the room after request. One birthing parent requested pads and ice packs, then expressed dissatisfaction with wearing the small pads given and requested larger pads twice.

Lack of interpretation service utilization impacted the clarity of healthcare team and birthing parent communication and maternal dignity. Responses to birthing parent needs for pads during the postnatal unit stay led to coordination with companions for access. For example, one Spanish-speaking companion used their phone to translate “adult diaper” to request pads for the Spanish-speaking Hispanic white multiparous parent. Two Spanish-speaking birthing parents expressed concerns to their companions around the limited quantity of menstrual hygiene products provided, but they did not request more from their healthcare team. One of these birthing parents sent their companion to buy pads in the hospital pharmacy.

Additionally, a Hispanic White Spanish-speaking multiparous birthing parent told her companion that the low level of inpatient room pad stocking suggested their healthcare team members did not know about the quantity of blood birthing parents lose after giving birth: “They bring me two [pads], they have no idea how much one can bleed. The night [nurse] didn’t bring me any pads” (V07). When pads were brought to birthing parents and when communication was language concordant, the interactions enabled conversation about product options and offered opportunity for ongoing support. A healthcare team member coordinated support: “I don’t know which one you’re using, [so] I brought you large and small ones. Do you use [need] diapers, pads, or other things?” (V07). Another interaction regarding access to menstrual hygiene products involved a companion asking if the couple can take products in the room home with them, to which the healthcare team member responds with affirmation about those pads and other supplies: “All the supplies and then the bathroom, the pads, everything, that’s yours too. Take all those. And then the soap like the shampoo and stuff that she used she can take all that” (V15).

Several birthing parents expressed concern with the need to ask a healthcare team member for access to products more than once. A workaround was to ask a technician “for the errands” because “the nurses forget [to respond to the patient requests] because they too busy” (V05). Access to pads after hospital discharge was also discussed among birthing parents and companions in varying contexts. In one instance, an individual asked a healthcare team member if they were allowed to access pads and ice packs if they remain at the hospital after their postpartum discharge while their infant receives treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The birthing parent spoke to a family member by phone about needing pads and diapers:

“They said they’ll try and help take care of me in certain ways down there [in the NICU], but I’m technically not a patient. Now I have to hoard [these products] for home but I’m also hoarding for this room. So it’s like, I’m like, ‘crap man.’ . . .it’s hard to double hoard—you have to, you have to play. . .and ask two different people that don’t know that you already have it. I keep taking all the diapers out of the drawer and telling them we’re out of diapers.” (V05) English-speaking, non-Hispanic multiracial first-time parent

Access to menstrual hygiene products after the hospital discharge transition were not observed in the observed counseling. nor were community-based resources such as the local diaper bank.

Patient safety: supporting maternal physical and emotional wellbeing through accurate information and respectful care

When interpretation services were used, there was a case of mistranslated information. Their healthcare team member stated, “If you have a lot of bleeding that fills up one pad in an hour or less, you will need to call your doctor right away.” Then the medical interpreter spoke in Spanish with information that translates to: “If you fill up a pad in one hour and if two hours go by and it happens again, please call your hospital or provider” (V03).

Timing between birthing parent requests and healthcare team distribution of vaginal bleeding related products (pads, underwear, or witch hazel/Tucks) took up to 45 min. Waits included maternal and companion verbal expressions of distress, especially in circumstances when the birthing parent was caring for their infant without a companion in the room. In one of these cases, a birthing parent states that their underwear is bloody. The birthing parent walks into the postnatal unit hallway to ask a healthcare team member for another pair of underwear. Her infant then cries as they wait. The birthing parent tries to soothe the infant in the bassinet, addressing the delay for both of them:

“Shhh. . .it’s okay girl, I’m coming, I’m coming girl, I’m coming girl, I’m coming girl, I’m coming, I gotta to get. . .I gotta go get my underwear on, I’m coming, I’m coming,” (V08), English-speaking, non-Hispanic white first-time parent

After making this statement, the birthing parent gets their old underwear off the hospital bed and steps into the hallway again without underwear on. While trying to keep themselves covered with their gown, they ask a passing healthcare team member: “Hey. . .can I- can I- can I get one of these underwear and um some ice. . .” The birthing parent then returns to the room and shuts the door, saying “What the. . .no-that, that is ridiculous, that was ridiculous, I felt really disrespected right now.” The individual then cries, goes into the bathroom, and speaks to themselves, “I cannot be alone. . .so disrespected I feel right now, in pain. . .hurting. . .and totally disrespected” (V08). Eighteen minutes passed from their request until they received clean underwear.

In an instance when a healthcare team member explained contributors for delay in delivering menstrual hygiene products, the information was followed by frustration and dissatisfaction from the birthing parent and their companion. In response to the companion calling-in the request, the healthcare member communicated that they were in the middle of shift change, but that someone would come to the postnatal unit room shortly. The companion thanked the person, ended the call, and then expressed frustration to the birthing parent, stating, “I didn’t need to know that you was in between shifts right now. I just need to get my shit. . .[this] piss[es] me off right now—just woke up” (V05). In contrast to some companions helping with access to vaginal bleeding products, one companion limited birthing parent access to pads. The patient asked the companion if “just to be on the safe side,” they should request permission to carry a couple of pads that were in the room home with them (V01). The companion replied, “I think you will be alright [without them]” and they left without the products.

Meaningful counseling: busy environment and differences with the information provided

The counseling environment within postnatal unit rooms sometimes occurred in the context of extensive in-room activities, such as infants crying or being fed, companions making telephone calls, and multiple healthcare providers doing different evaluations simultaneously, especially in the last hours prior to discharge. In three instances of vaginal bleeding counseling interactions, birthing parents were asked to confirm understanding of the information with the healthcare team member; this confirmation of comprehension was not consistent. Conflicting information from clinicians was also observed, such as variations in describing vaginal bleeding expectations. For example with one family, a healthcare team member came into the postnatal unit room the morning of hospital discharge, greeted the patient and their companion, introduced herself, and asked what language they prefer (V12). In response, she offered in Spanish, “Vaginal bleeding can last up to six weeks. But you should never fill up a pad of a normal size. If you’re filling it up completely within an hour, it’s a lot of blood and I want you to come to the hospital” (V12). The interaction also included time spent engaging around questions. Later with this family, an hour prior to their discharge, two different healthcare team members and an interpreter enter the room, say hello, introduce themselves, and provide postpartum bleeding information that slightly differed:

“For momma, at this time, we want to make sure that bleeding is decreasing, not increasing. So if you’re having any clots that are egg sized or larger or saturating in a pad in an hour or less, call your doctor. That’s not normal at this point.”

This information describes pads filling over time as a cause for concern but did not mention clots. The birthing parent is not asked about their comprehension or asked if the information they received from other healthcare team members was consistent. Furthermore, the infant had been crying throughout the communication, and both parents were trying to care for their infant while the healthcare team members stood and read discharge instructions aloud.

Many counseling experiences were paired with written materials. The printed “After Visit Summary” was offered as a source of information when a birthing parent asked where they could find the information verbally shared. The clinician replied, “I’m sure you’re gonna forget because everybody forgets, it’s kind of a hard time cause you’re tired and everything. The most important thing will be written down for you in your discharge summary” (V16). Healthcare team members also navigated competing responsibilities during vaginal bleeding counseling, such as interruptions from clinical communication devices during their time in-room with patients.

Discussion

Access to menstrual supplies during the inpatient postpartum stay is an often overlooked, yet critical aspect of patient care and bleeding management. This transitional period is a memorable and high-needs part of the reproductive life course. In this research study with 15 birthing parents, 12 of them had communication on vaginal bleeding topics between 2 and 5 times, 2 of them had one exchange, and 1 of them had none observed. These findings raise concerns on the consistency of counseling and discharge communication, with implications for patient safety. Postpartum hemorrhage is a major cause for readmission in the United States, with Black and Brown birthing parents more likely to experience severe postpartum hemorrhage than their White counterparts.20 –22 In North Carolina, rurality, socioeconomic status, and culture impact maternal vulnerability, with patients often driving a long distance to access care at the study institution. 23 Education on monitoring and managing postpartum bleeding begins in the inpatient unit and standard messaging to address subjective patient expectations of bleeding can be lifesaving. 10

The lack of supplies readily available in postpartum rooms for managing postpartum bleeding was observed as a source of stress among patients and their companions. Several participants noted dissatisfaction with delays in restocking supplies after requesting more. Due to their immediate needs for postpartum pads, one family expressed frustration when having to use a personal phone to translate their request; others expressed frustration when staff offered explanations for their delays responding to patients’ requests for more pads or underwear. When periodically checking on patients, healthcare team members inconsistently assessed patients’ needs for more supplies. When supplies were restocked, the pad size or quantity sometimes differed from what was needed, forcing patients to repeat the process of requesting more pads or find an alternative way to acquire the essential supplies. When companions are present in the inpatient postpartum room, they should be afforded the time to bond with their new baby, rather than having to leave to fulfill a birthing parent’s request to purchase more pads as was observed with one family. The inpatient postpartum stay is already full of potential stressors as patients transition to the role of parenting a newborn while managing their own healing after childbirth. The lack of access to pads, a comparatively inexpensive supply when evaluating the cost of an entire hospital admission, should not be an additional stressor.

Patient safety, dignity, and autonomy were compromised when patients had unmet needs for supplies during the inpatient stay. Several parents discussed experiencing stress around asking for supplies, worrying about being burdensome. Then they verbalized emotional distress and vulnerability while waiting for the requested supplies to be delivered. This discomfort in requesting supplies creates a communication barrier between patients and healthcare teams and in some situations forces patients to rely on companions to serve as an advocate. Furthermore, birthing parents’ well-being was undermined from instances of loss of dignity, specifically when there were long delays before the requested pads were provided. Although unintentional, healthcare team members may convey perception of blame on the birthing parent or companion for requesting supplies when the staff gave reasons to explain why it took them so long to bring the pads. Such miscommunication can further complicate the provider–patient relationship and undermine the trust between both—which is an essential component of safe and respectful care.

Both the healthcare team and patients may be unaware of the complex realities and the competing interests of nurses, staff, providers, companions, and patients during the 12 h prior to hospital discharge inside and outside of the postnatal unit room; communicating these realities to one another is challenging. Additionally, patients with Limited English Proficiency experience a loss of autonomy; in this study interpretation services were not always utilized for communication with Spanish-speaking birthing parents, consistent with recent research that identified language discordance on the postnatal unit. 15 Further, communication occurred while companions and patients were distracted by infant needs or by having multiple healthcare team members in the room, which does not support comprehensible information exchange. The lack of meaningful communication added unnecessary barriers and stress.

The content of the counseling that healthcare team members provided on postpartum bleeding and warning signs was inconsistent. An interpretation was incorrect, such inconsistency introduce risks for patient safety. Overall, it seemed that the postpartum discharge education may not be as effective as imagined, given the environment in which it occurs and the checklist approach. There is opportunity to assess birthing parent perspectives on the patterns, tailoring, and depth for health information and care planning. Shared decision-making requires the ability of patients and their companions to hear and process information. Language concordance and teach back can be part of positive experiences, for families to be and feel supported, listened to, and respected.11,12 Companions can also serve as a maternal support at home, helping to monitor for worsening vaginal bleeding and utilizing healthcare services for the birthing parent as warranted. Including them as active participants in all maternity counseling, especially counseling for the warning signs for postpartum hemorrhage, can improve birthing parents’ experiences, access to timely care upon discharge, and outcomes.

It is important to highlight positive inpatient experiences as examples to celebrate and grow. Some healthcare team members focused on the patient experiences with bleeding and communicated expectations and warning signs, in birthing parents’ preferred language in many interactions. Culturally aligned care in also critical for postpartum menstrual equity, such as observed when a healthcare team member acknowledged the patient’s discomfort or made effort to offer options and a greater quantity of supplies when they did not know patient preferences. Future work can further assess supportive practices around vaginal bleeding counseling—which is an often uncomfortable and culturally taboo topic—so that it is easier for minoritized patients to discuss and engage. 4 Ensuring postpartum menstrual equity during discharge includes intentional positioning and eye contact, to connect with patients during their inpatient stay and actively equip them for hospital discharge. It is expected that patients will continue to need pads for managing postpartum bleeding once they return home, as well as access to period supplies in the future when their menstrual cycles resume. Yet, healthcare team members inconsistently offered supplies for patients to take home upon discharge or and there was hesitancy around whether birthing parents should take the pads that were already in their rooms. None of the observations included assessment of a patient’s ability to access or afford pads after they left the hospital. The data also did not include communication about the opportunity to access a community-based resource, the period supply program of a state-wide diaper bank, for products. This was a missed opportunity for patient empowerment and access upon discharge. Postpartum bleeding requiring medical attention typically includes the use of pads as tools for blood loss measurement, and yet, access to these supplies is not assessed in routine inpatient counseling or included in patient discharge information. Additionally, the dismissal by one companion of a birthing parent’s consideration to take home pads could be innocuous, a sign of relationship tension, or reflect lack of awareness about needs to manage postpartum bleeding at home.

Access to menstrual products often comes at severe personal cost, physically, emotionally, and financially—costs that negatively impact menstruators’ safety and wellbeing. 7 A 2019 study of low-income women in St. Louis found that about 66% were unable to afford menstrual products at some point during the past year, with several resorting to substitutions such as toilet paper or rags. 5 In that previous research, menstruators chose between buying food and spending money on menstrual products, with Black and Latinx people having to make this decision more often. 7 For low-income families, Women, Infants, and Children program and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits often offer supplemental food packages as a part of postpartum care, but no policy program provides access to menstrual products or the funds to purchase them. 9 These economic and racial inequities in menstrual equity were worsened during the pandemic, with a 2022 study noting increased menstrual insecurity with people who suffered income loss. 24 Although the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) was passed in 2020 to allow Americans to use their health savings account and health reimbursement arrangements to purchase menstrual products, it addresses only a small part of the larger issue. 24 The Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act comprised of 12 bills aimed at addressing the multi-faceted issue of racial inequities in obstetric outcomes in the United States. 25 Yet, none of these bills included provisions for menstrual equity in the postpartum period, suggesting this problem remains hidden and overlooked. 25

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include unique insight into postpartum care interactions through naturalistic filming and audio-recording. The data offer nuanced information on the realities of addressing postpartum bleeding on the postpartum unit, with strengths and areas for opportunities as observed with diverse families. The qualitative component of this study highlights the emotional and other patient safety impacts of inadequate access to postpartum supplies and communication.

Our analysis focused on the last 12 h of the inpatient stay prior to discharge; a limitation to our study is that unit admission and counseling outside of the observation period is unknown. Furthermore, data collection at a single institution limits generalizability, although the literature suggests barriers to vaginal bleeding counseling and access to menstrual products may be widespread. Additionally, the recording equipment was turned off in some instances—demonstrating participant agency in this type of intimate research. This study was also conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could have impacted the staffing levels and environment, with healthcare team members minimizing room entry to reduce potential exposure. However, the observed wait times and distress incurred are unacceptable when aiming for just and equitable care.

In this analysis, we did not explore patient characteristics such as having a shoulder dystocia, cesarean section, or postpartum hemorrhage as confounding experiences. Birth experiences can impact postpartum vaginal bleeding counseling; for example, patients who had a postpartum hemorrhage may be more likely to receive information about bleeding and warning signs. They also may be traumatized from the experience, leading to differences in bleeding vigilance and interrelated behaviors from the emotional and physical distress. One case in this sample identified complexity with birthing parent discharge in the context of ongoing infant hospitalization. Previous research of maternal health needs in the NICU setting similarly found gaps in access to pads in that unit. 26 Future studies could prospectively evaluate vaginal bleeding counseling and management through pregnancy and through various contexts throughout the postpartum year to understand facilitators and barriers to access, safety, and postpartum menstrual equity.

Conclusion

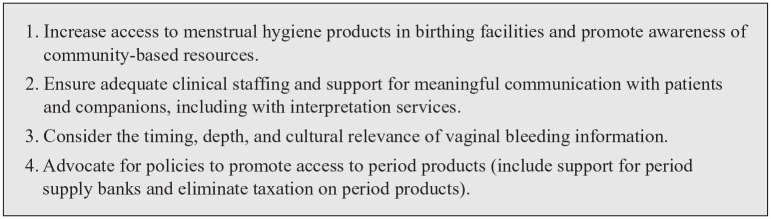

Postpartum menstrual equity encompasses information, access to hygiene supplies, affordability, and safety for individual’s autonomy around vaginal bleeding—an important aspect of the postpartum phase of a person’s reproductive life cycle. This study explored clinical communication, the availability of supplies, and companion involvement around vaginal bleeding management during postpartum hospitalization. Most families had a few exchanges with their healthcare team members about postpartum bleeding, 2 had no communication, and 10 received information on vaginal care, bleeding amounts, or pads in the hour preceding discharge. There are opportunities to strengthen clinical practices for maternal safety and to advance respectful, equitable care (Figure 2). The need for staff to replenish menstrual supplies and offer product options as a part of their routine care and discharge process was evident. Managing postpartum vaginal bleeding is important, yet services are not yet structured to adequately support postpartum families during their inpatient vaginal bleeding care or to connect them with community-based resources for period product access across the patient’s reproductive life course.

Figure 2.

Recommendations for improving postpartum menstrual equity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The funding organization was not involved in the data collection, analysis, and interpretation or the preparation of the manuscript and has no right to approve or disapprove publication of the finished manuscript. The authors are solely responsible for this document’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or HHS. We are grateful to participants for their time and willingness to share their experiences. We thank Marina Pearsall for project management and Maria Fernanda Ochoa Toro for recruitment and data collection. This article was presented as a poster publication at both the National Perinatal Association National Conference on April 20, 2023 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and at the National Institutes of Health Innovative Approaches to Improve Maternal Health Workshop in Bethesda, Maryland from May 8 to 9, 2023.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Kelley EC Massengale  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2868-2472

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2868-2472

Catalina Montiel  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4001-5947

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4001-5947

Kristin P Tully  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5214-2287

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5214-2287

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This work was reviewed by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Biomedical Review Board (#19-1900) and approved. Written, informed consent was conducted in person. Birthing parents and companions provided informed, written consent for their participation and permission of their infants to participate in the filming research project on the postnatal unit between August and December 2020.

Consent for publication: We have obtained written informed consent to publish these data as described in our institutional review board document.

Author contribution(s): Shilpa M Darivemula: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Kelley EC Massengale: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Catalina Montiel: Formal analysis; Writing – review & editing.

Alison M Stuebe: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Kristin P Tully: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R18HS027260, Department of Health and Human Services.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Drs. Tully and Stuebe are inventors of a patented medical device. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill intellectual property is licensed. The device is not referenced or otherwise related to the content of this manuscript. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The data are identifiable and therefore not available.

References

- 1. Weiss-Wolf J. Periods gone public: taking a stand for menstrual equity. New York, NY: Archade, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finlayson K, Crossland N, Bonet M, et al. What matters to women in the postnatal period: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS One 2020; 15(4): e0231415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sommer M, Phillips-Howard PA, Mahon T, et al. Beyond menstrual hygiene: addressing vaginal bleeding throughout the life course in low and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 2017; 2(2): e000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sommer M, Mason DJ. Period poverty and promoting menstrual equity. JAMA Health Forum 2021; 2(8): e213089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuhlmann AS, Bergquist EP, Danjoint D, et al. Unmet menstrual hygiene needs among low-income women. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133(2): 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gruer C, Hopper K, Smith RC, et al. Seeking menstrual products: a qualitative exploration of the unmet menstrual needs of individuals experiencing homelessness in New York City. Reprod Health 2021; 18(1): 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darivemula S, Knittel A, Flowers L, et al. Menstrual equity in the criminal legal system. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2023; 32(9): 927–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cardoso LF, Scolese AM, Hamidaddin A, et al. Period poverty and mental health implications among college-aged women in the United States. BMC Womens Health 2021; 21(1): 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiss-Wolf J. Periods don’t stop for pandemics—and neither have our nation’s moms. Marie Clare, September 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yargawa J, Fottrell E, Hill Z. Women’s perceptions and self-reports of excessive bleeding during and after delivery: findings from a mixed-methods study in Northern Nigeria. BMJ Open 2021; 11(10): e047711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tully KP, Stuebe AM, Verbiest SB. The fourth trimester: a critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 217(1): 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearsall MS, Stuebe AM, Seashore C, et al. Welcoming, supportive care in US birthing facilities and realization of breastfeeding goals. Midwifery 2022; 111: 103359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King PL, Bamel D, Adams KM. Postpartum discharge transition change package, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, https://saferbirth.org/wp-content/uploads/PPDT-Change-Package-Final_5.8.23.pdf (2022, accessed 1 December 2023).

- 14. Rudman A, Waldenström U. Critical views on postpartum care expressed by new mothers. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; 7: 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jensen JL, Sweeney A, Gill C, et al. Evaluation of patient access to Spanish-language concordant care on a postpartum unit. Nurs Womens Health 2022; 26(6): 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Patient Safety Bundles, https://saferbirth.org/patient-safety-bundles/ (2021, accessed 1 December 2023).

- 17. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007; 335(7624): 806–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saldaña J. (ed.). The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fein A, Wen T, Wright JD, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage and risk for postpartum readmission. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021; 34(2): 187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clapp MA, Little SE, Zheng J, et al. Hospital-level variation in postpartum readmissions. JAMA 2017; 317(20): 2128–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Srinivas SK, Wright JD, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage outcomes and race. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 219(2): 185.e1–185.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. March of Dimes, Peristats. 2023. Report Card for North Carolina, https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/reports/north-carolina/report-card (2023, accessed 1 December 2023).

- 24. Sommer M, Phillips-Howard PA, Gruer C, et al. Menstrual product insecurity resulting from COVID-19‒related income loss, United States, 2020. Am J Public Health 2022; 112(4): 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arbuckle S. All aboard the Momnibus: will Congress’s proposed legislative package help drive down Black maternal mortality rates? SMU Sci Technol Law Rev 2021; 24: 413. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verbiest S, Ferrari R, Tucker C, et al. Health needs of mothers of infants in a neonatal intensive care unit: a mixed methods study. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173(11 Suppl): S37–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]