Abstract

Background

Acute liver failure (ALF) following cardiac arrest (CA) poses a significant healthcare challenge, characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates. This study aims to assess the correlation between serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels and poor outcomes in patients with ALF following CA.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted utilizing data from the Dryad digital repository. The primary outcomes examined were intensive care unit (ICU) mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to assess the relationship between serum ALP levels and clinical prognosis. The predictive value was evaluated using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Two prediction models were developed, and model comparison was performed using the likelihood ratio test (LRT) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Results

A total of 194 patients were included in the analysis (72.2% male). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a one-standard deviation increase of ln-transformed ALP were independently associated with poorer prognosis: ICU mortality (odds ratios (OR) = 2.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31–4.74, P = 0.005), hospital mortality (OR = 2.21, 95% CI 1.18–4.16, P = 0.014), and unfavorable neurological outcome (OR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.25–4.60, P = 0.009). The area under the ROC curve for clinical prognosis was 0.644, 0.642, and 0.639, respectively. Additionally, LRT analyses indicated that the ALP-combined model exhibited better predictive efficacy than the model without ALP.

Conclusions

Elevated serum ALP levels upon admission were significantly associated with poorer prognosis of ALF following CA, suggesting its potential as a valuable marker for predicting prognosis in this patient population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-024-02049-2.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, Acute liver failure, Clinical prognosis, Risk factor, Cardiac arrest

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a life-threatening complication encountered in critically ill patients within the intensive care unit (ICU). It affects 16–56% of patients suffering from post-cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS) during their treatment and is associated with poor clinical outcomes, highlighting the liver's significant role in the pathophysiology of cardiac arrest (CA) syndrome [1, 2]. Despite advancements in diagnosis and treatment, the mortality rate for patients with ALF following CA remains alarmingly high [1].

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a glycoprotein primarily located on cell membranes and is predominantly found in various human tissues, including the liver, bone, placenta, kidney, and small intestine [3]. ALP is closely linked to several adverse risk factors, particularly inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and coagulation [4]. Inflammation is pivotal in the pathogenesis of ALF, where reactive oxygen species production aggravates mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, resulting in hepatocyte necrosis [5]. During ALF, ALP activity increases in liver tissue, indicating a protective response to immunological liver damage by neutralizing endotoxins [6]. Additionally, ALP can dephosphorylate and detoxify lipopolysaccharides (LPS), thereby reducing liver inflammation by downregulating inflammatory pathways, including TLR4, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NF-Κb [7, 8]. Consequently, patients with ALF demonstrate a significant elevation in serum ALP levels. In clinical settings, serum ALP levels are well-established markers of skeletal or hepatobiliary dysfunction [9, 10]. Recent findings suggest a relationship between serum ALP levels and the risk of cardiovascular diseases, as well as all-cause mortality in diverse populations, including those with chronic kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and coronary artery disease [4, 11–13]. Furthermore, several studies show a positive correlation between serum ALP levels and both all-cause mortality and poor functional prognosis following cerebrovascular disease [14, 15]. However, the existence of a similar association between serum ALP levels and mortality or neurological outcomes in patients with ALF following CA remains unclear.

We hypothesized that elevated total serum ALP levels independently correlate with poorer prognosis in patients with ALF following CA. Thus, we conducted a longitudinal cohort study to assess the association between serum ALP levels and mortality/neurological outcome in this patient population.

Methods

Study population

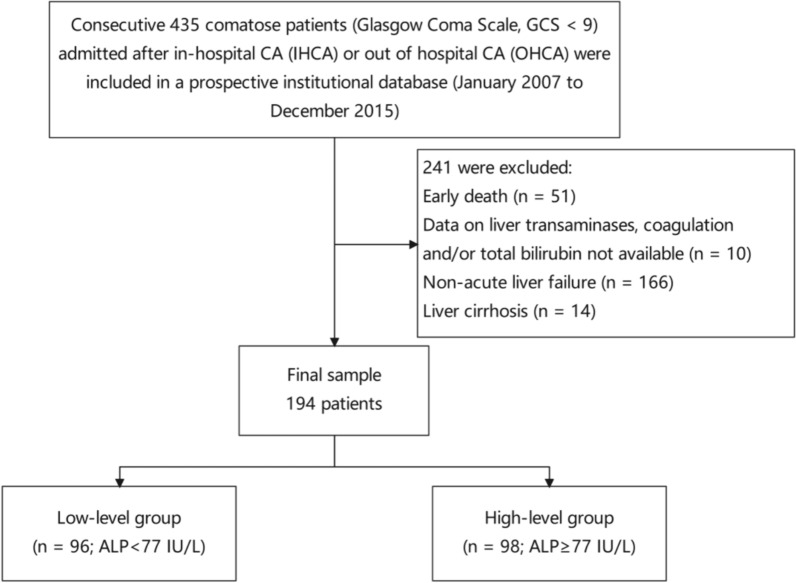

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the Dryad digital repository (10.5061/dryad.qv6fp83). Conducted at Erasme Hospital, Brussels, Belgium, from January 2007 to December 2015, it focused on ICU-treated in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité d’Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire Erasme-ULB (P2017/264), but waived the need for informed consent because of its retrospective nature. Included 194 comatose patients with acute liver failure following IHCA or OHCA (Glasgow Coma Scale < 9). Exclusion criteria comprised deaths within 24 h of admission (n = 51), the absence of liver function data (n = 10), concurrent cirrhotic disease (n = 14), and the absence of ALF following CA (n = 166) (Fig. 1). All CA and comatose patients underwent 24-h targeted temperature management (TTM) with a target temperature of 32–34 °C, employing midazolam and morphine for deep sedation and cisatracurium for shivering control. Post-resuscitation treatment followed established protocols [16].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study population with inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data collection

We collected demographic data, arrest characteristics, and comorbidity profiles for all patients. Disease severity was assessed upon admission using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Initial laboratory assessments on admission following return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) included blood gas analysis (pH, PaO2, PaCO2) and standard tests such as serum alanine transaminase (ALT), serum aspartate transaminase (AST), ALP, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), serum lactate, serum creatinine, total bilirubin (normal range ≤ 1.2 mg/dL), international normalized ratio (INR) (normal range ≤ 1.2), prothrombin time (PT) (normal range > 70%), and platelet (normal range 150–350 × 103/mm). Mean arterial pressure (MAP), mechanical ventilation, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), vasoactive drug usage, and ICU length of stay were documented.

Definitions

ALF following CA was defined as a condition characterized by an INR levels equal to or greater than 1.5, elevated total bilirubin levels, and the absence of chronic liver disease [1, 2]. Shock was defined as a systolic arterial pressure below 90 mmHg despite appropriate volume expansion, necessitating vasopressor support (e.g., dopamine/dobutamine, adrenaline) for over 6 h. ICU and in-hospital mortality refer to all-cause mortality during the ICU stay and overall hospitalization, respectively. An unfavorable neurological outcome was delineated by a cerebral performance categories score (CPC) of 3–5 at 90 days, while a favorable outcome was a CPC of 1–2[17]. The CPC scale ranges from 1 (good cerebral functioning or mild disability) to 5 (brain death). CPC assessments were conducted prospectively by the general practitioner via telephone interviews during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (25th to 75th percentiles) or mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%). For continuous variables, the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was utilized to assess normality of distribution. Pearson's Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was employed for categorical data. For baseline characteristics analysis, serum ALP levels were categorized into two groups according to the median: < 77 IU/L and ≥ 77 IU/L. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for the risk of mortality/unfavorable neurological outcome according to serum ALP levels (median and one-standard deviation increase of ln-transformed) in patients with ALF following CA. We corrected for age, sex, adrenaline, cardiac cause, out-of-hospital, non-shockable rhythm, chronic anticoagulation, shock, vasopressor therapy, CRP, and MAP as potential confounders. Subsequently, restricted cubic spline models and smooth curve fitting were utilized to investigate the relationship between serum ALP levels and clinical prognosis. Interaction and stratified analyses were conducted based on subgroup variables, with interaction across subgroups assessed using likelihood ratio tests. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and the predictive performance of serum ALP levels on prognosis was assessed using the area under the curve (AUC). Model comparison were performed using the likelihood ratio test (LRT) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics Analysis Platform (Version 1.9, Beijing, China). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the participants (n = 194) in the cohort study. The average age of the participants was 62.0 (52.0, 73.8) years, with 72.2% being male. The high-level group predominantly consisted of participants with non-shockable rhythms, IHCA, and chronic renal failure. Additionally, those in the high-level group was more likely to present with poorer laboratory results and to require more interventions compared to the low-level group.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study participants

| Variables | Total (n = 194) |

ALP < 77 IU/L (n = 96) |

ALP ≥ 77 IU/L (n = 98) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.0 (52.0, 73.8) | 61.5 (52.0, 74.0) | 64.0 (51.2, 73.0) | 0.773 |

| Weight, kg | 77.0 (68.0, 85.0) | 75.0 (65.0, 83.0) | 78.0 (70.0, 85.0) | 0.189 |

| Male, n (%) | 140 (72.2) | 73 (76) | 67 (68.4) | 0.233 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 5.0 (2.2, 10.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 10.2) | 4.5 (2.0, 9.0) | 0.3 |

| APACHE II score | 25.0 (20.2, 29.0) | 25.0 (21.0, 29.0) | 25.0 (19.0, 30.0) | 0.953 |

| SOFA score | 11.5 (9.0, 14.0) | 12.0 (9.0, 14.0) | 11.0 (9.0, 14.0) | 0.716 |

| Arrest characteristics | ||||

| Witnessed, n (%) | 166 (85.6) | 82 (85.4) | 84 (85.7) | 0.953 |

| Bystander CPR, n (%) | 136 (70.1) | 66 (68.8) | 70 (71.4) | 0.684 |

| Time to ROSC, min | 15.5 (7.0, 28.0) | 15.0 (9.0, 30.0) | 16.0 (7.0, 25.0) | 0.388 |

| Adrenaline, mg | 4.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 0.309 |

| Out-of-Hospital, n (%) | 98 (50.5) | 57 (59.4) | 41 (41.8) | 0.015 |

| TTM, n (%) | 172 (88.7) | 91 (94.8) | 81 (82.7) | 0.008 |

| Cardiac cause, n (%) | 109 (56.2) | 54 (56.2) | 55 (56.1) | 0.986 |

| Non-shockable rhythm, n (%) | 126 (64.9) | 54 (56.2) | 72 (73.5) | 0.012 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic anticoagulation, n (%) | 34 (17.5) | 17 (17.7) | 17 (17.3) | 0.947 |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 49 (25.3) | 26 (27.1) | 23 (23.5) | 0.562 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 82 (42.3) | 37 (38.5) | 45 (45.9) | 0.298 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 77 (39.7) | 43 (44.8) | 34 (34.7) | 0.151 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 44 (22.7) | 21 (21.9) | 23 (23.5) | 0.791 |

| COPD/asthma, n (%) | 33 (17.0) | 17 (17.7) | 16 (16.3) | 0.798 |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 23 (11.9) | 9 (9.4) | 14 (14.3) | 0.29 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 43 (22.2) | 15 (15.6) | 28 (28.6) | 0.03 |

| During ICU stay | ||||

| IABP, n (%) | 15 ( 7.7) | 9 (9.4) | 6 (6.1) | 0.396 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 36 (18.6) | 23 (24) | 13 (13.3) | 0.055 |

| Shock, n (%) | 121 (62.4) | 57 (59.4) | 64 (65.3) | 0.394 |

| Vasopressor therapy, n (%) | 155 (79.9) | 70 (72.9) | 85 (86.7) | 0.016 |

| Inotropic agents, n (%) | 122 (62.9) | 61 (63.5) | 61 (62.2) | 0.852 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 192 (99.0) | 96 (100) | 96 (98) | 0.497 |

| CRRT, n (%) | 40 (20.6) | 16 (16.7) | 24 (24.5) | 0.178 |

| Blood sample on admission | ||||

| Lactate, mEq l−1 | 5.6 (4.4, 9.0) | 5.8 (4.4, 9.1) | 5.4 (4.4, 8.9) | 0.826 |

| CRP, mg dl−1 | 42.0 (15.8, 100.0) | 29.0 (10.0, 70.0) | 53.0 (24.0, 127.5) | < 0.001 |

| SCr, mg dl−1 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.1) | 0.344 |

| ScvO2/SvO2, % | 68.8 (63.3, 74.2) | 67.7 (63.0, 71.6) | 69.5 (64.5, 76.8) | 0.124 |

| AST, IU/L | 104.5 (51.2, 236.5) | 102.5 (42.8, 209.5) | 111.5 (62.0, 239.2) | 0.242 |

| ALT, IU/L | 71.0 (35.0, 178.8) | 75.0 (33.0, 172.8) | 70.5 (39.0, 184.2) | 0.504 |

| LDH, IU/L | 366.5 (245.2, 531.2) | 332.5 (238.8, 452.2) | 451.5 (250.8, 634.0) | 0.016 |

| ALP, IU/L | 77.0 (58.0, 108.8) | 58.0 (44.5, 65.2) | 108.5 (86.2, 169.0) | < 0.001 |

| GGT, IU/L | 66.0 (41.0, 102.0) | 55.0 (33.0, 86.0) | 77.5 (55.0, 135.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg dl−1 | 0.6 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.005 |

| APTT, sec | 37.4 (29.5, 60.2) | 36.7 (29.8, 69.1) | 38.0 (29.3, 54.6) | 0.897 |

| PT, % | 50.5 (38.2, 70.0) | 47.0 (37.8, 65.5) | 56.0 (40.2, 72.0) | 0.074 |

| INR | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.9) | 0.172 |

| Platelets,/mm3 | 173.5 (121.0, 235.8) | 172.0 (127.0, 235.2) | 174.5 (119.5, 237.0) | 0.994 |

| Glucose, mg dl−1 | 200.0 (150.2, 295.5) | 222.5 (169.0, 322.5) | 189.5 (132.8, 269.8) | 0.016 |

| pH | 7.3 (7.2, 7.4) | 7.3 (7.2, 7.4) | 7.3 (7.2, 7.4) | 0.3 |

| MAP, mmHg | 84.0 (73.2, 98.8) | 84.5 (74.2, 97.0) | 84.0 (71.8, 101.5) | 0.801 |

Data presented are median (25th–75th percentile), or N (%)

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; TTM, targeted temperature management; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; ScvO2/SvO2, central venous/mixed venous oxygen saturation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ- glutamyl transferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; SCr, serum creatinine; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Primary outcomes

Table 2 presents the cumulative incidences of prognosis among the 194 patients included in the study. Of these patients, 106 (54.6%) died in the ICU, 116 (59.8%) died during hospitalization, and 121 (62.4%) experienced an unfavorable neurological outcome. Participants in the high-level group were more likely to have higher rates of ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Primary outcomes

| Outcome | Total (n = 194) |

ALP < 77 IU/L (n = 96) |

ALP ≥ 77 IU/L (n = 98) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 106 (54.6) | 41 (42.7) | 65 (66.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 116 (59.8) | 46 (47.9) | 70 (71.4) | < 0.001 |

| Unfavorable neurological outcome, n (%) | 121 (62.4) | 50 (52.1) | 71 (72.4) | 0.003 |

ICU: intensive care unit

Fig. 2.

Relationship between serum ALP levels and clinical prognosis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

Table 3 shows the results from multivariate logistic regression analysis. When ALP was considered as a continuous variable(ln), elevated serum ALP levels were associated with an increased risk of ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome, with OR of 2.49 [1.31–4.74], 2.21 [1.18–4.16], and 2.40 [1.25–4.60], respectively. When ALP was treated as a categorical variable, the OR remained significantly associated with all three outcomes (2.53 [1.24–5.14], 2.29 [1.13 ~ 4.64], and 2.09 [1.02–4.29], respectively). Furthermore, a restricted cubic splines regression model indicated that the risk for all three outcomes increased linearly with rising serum ALP levels (P for non-linearity = 0.816, 0.598 and 0.342, respectively) (Figure S1).

Table 3.

Multifactorial logistic regression analysis of serum ALP levels and poor outcomes in patients with ALF following CA

| Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| ICU mortality | ||||||

| Per-SD increase of ln (ALP levels) | 2.66 (1.53–4.65) | 0.001 | 2.65 (1.52–4.62) | 0.001 | 2.49 (1.31–4.74) | 0.005 |

| ALP levels | ||||||

| ALP < 77 IU/L | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| ALP ≥ 77 IU/L | 2.64 (1.48–4.73) | 0.001 | 2.61 (1.45–4.7) | 0.001 | 2.53 (1.24–5.14) | 0.010 |

| Hospital mortality | ||||||

| Per-SD increase of ln (ALP levels) | 2.62 (1.49–4.62) | 0.001 | 2.59 (1.47–4.56) | 0.001 | 2.21 (1.18–4.16) | 0.014 |

| ALP levels | ||||||

| ALP < 77 IU/L | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| ALP ≥ 77 IU/L | 2.72 (1.5–4.92) | 0.001 | 2.69 (1.47–4.9) | 0.001 | 2.29 (1.13–4.64) | 0.022 |

| Unfavorable neurologic outcome | ||||||

| Per-SD increase of ln (ALP levels) | 2.61 (1.47–4.63) | 0.001 | 2.57 (1.45–4.56) | 0.001 | 2.40 (1.25–4.60) | 0.009 |

| ALP levels | ||||||

| ALP < 77 IU/L | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| ALP ≥ 77 IU/L | 2.42 (1.33–4.40) | 0.004 | 2.38 (1.31–4.35) | 0.005 | 2.09 (1.02–4.29) | 0.044 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALF, acute liver failure; CA, cardiac arrest; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; ICU: intensive care unit; MAP = mean arterial pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein

Model 1: Adjust for age and sex

Model 2: Adjust for Model1 + adrenaline + cardiac cause + out of hospital + non-shockable rhythm + chronic anticoagulation + shock + vasopressor therapy + CRP + MAP

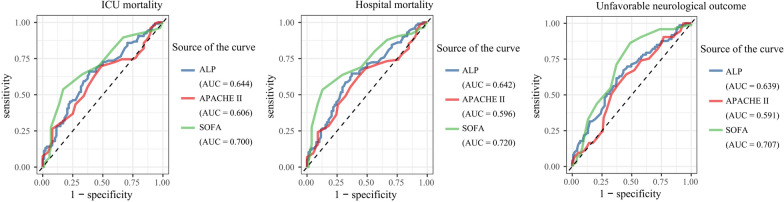

The predictive accuracy for clinical prognosis

The ROC curve results showed that the AUC was 0.644 (95% CI 0.567–0.722) for ICU mortality, 0.642 (95% CI 0.563–0.721) for hospital mortality, and 0.639 (95% CI 0.559–0.719) for unfavorable neurological outcome (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of ROC curves for predicting ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome

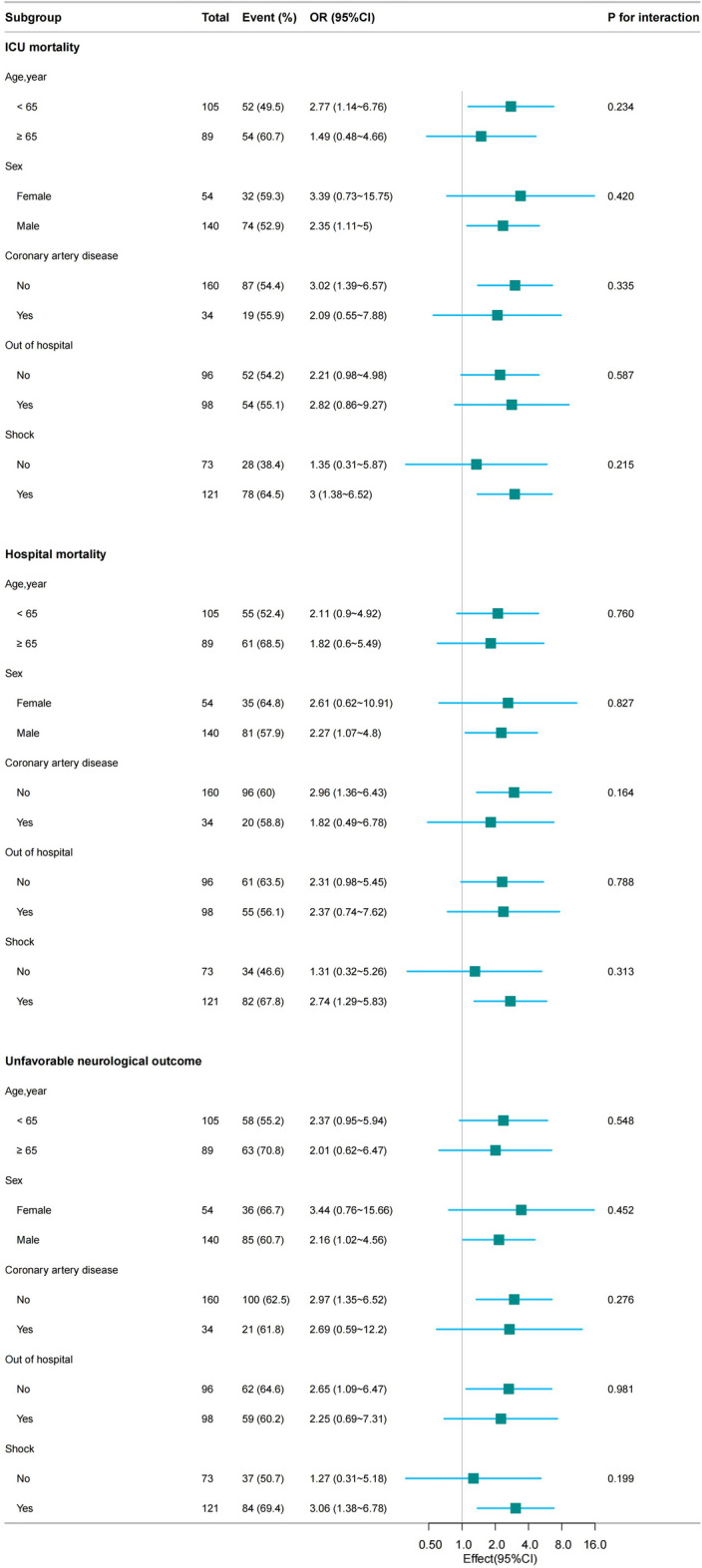

Subgroup analysis

We analyzed the risk stratification value of serum ALP levels for primary endpoints in multiple subgroups of the enrolled patients, including age, sex, coronary artery disease, OHCA, and shock (Fig. 4). Overall, the positive correlation between serum ALP levels and all three prognosis were generally consistent across subgroups, with higher serum ALP levels associated with higher rate of ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome.

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analysis of the association between serum ALP levels and clinical prognosis

Adding the ALP to clinical information

Table 4 displays the evaluation of two multivariate models using LRT, AIC, and AUC. Model 2 consistently showed higher LRT compared to Model 1 for all three clinical prognosis. Specifically, for ICU mortality, AIC values decreased from 248.39 in Model 1 to 237.31 in Model 2, with AUC increasing from 0.732 to 0.768. Similarly, for hospital mortality, AIC values decreased from 243.57 to 235.23, with AUC increasing from 0.729 to 0.759. For unfavorable neurological outcome, AIC values decreased from 238.12 to 230.00, with AUC increasing from 0.733 to 0.7767. These findings indicate that combining serum ALP levels with Model 1 improves the prognostic prediction model.

Table 4.

Comparison of different prognostic models in patients with ALF following CA

| Model predictors | LRT | AIC | P value | AUROC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU mortality | ||||

| Model 1 | 32.88 | 248.39 | < 0.001 | 0.732 |

| Model 2 | 45.96 | 237.31 | < 0.001 | 0.768 |

| Hospital mortality | ||||

| Model 1 | 31.88 | 243.57 | < 0.001 | 0.729 |

| Model 2 | 42.21 | 235.23 | < 0.001 | 0.759 |

| Unfavorable neurological outcome | ||||

| Model 1 | 32.82 | 238.12 | < 0.001 | 0.733 |

| Model 2 | 43.04 | 230.00 | < 0.001 | 0.767 |

ALF: acute liver failure, CA: cardiac arrest, LRT: likelihood ratio test, AIC: Akaike information criterion, AUC: area under the curve

Model 1 included age, sex, adrenaline, out of hospital, and shock

Model 2 included model 1 plus the serum ALP

Discussion

In this study, we explored for the first time the association between serum ALP levels and prognosis in patients with ALF following CA. Our findings revealed that elevated serum ALP levels was independently linear correlation associated with increased ICU mortality, hospital mortality and unfavorable neurological outcome in this patient population. And this association persisted for ALP after adjustment for confounders and remained robust in subgroup analyses. The addition of ALP to the original model enhanced its prognostic predictive abilities. Furthermore, as our inclusion of patients with both IHCA and OHCA, broadens the generalizability of our findings. The results suggest that serum ALP levels could be a promising biomarker for predicting prognosis in patients with ALF following CA. Nevertheless, additional research is required to validate these findings and to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

Nearly all population-based studies, have consistently shown an association between serum ALP levels and increased all-cause mortality. An analysis involving 34,147 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted from 1999 to 2014 revealed a positive correlation between serum ALP levels and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population[4]. A multicenter randomized trial found that elevated serum ALP levels were associated with higher mortality rates among African Americans with stage III and stage IV chronic kidney disease [11]. Additionally, previous studies have indicated that elevated serum ALP levels not only predict in-hospital mortality following acute cerebral infarction, but also correlate with a poor neurological outcomes at three months [15], which is similarly applicable to patients with cerebral hemorrhage [14]. These findings align with those of our study, where multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that elevated serum ALP levels were associated with an increased risk of ICU mortality, hospital mortality, and unfavorable neurological outcome, with OR of 2.49 [1.31–4.74], 2.21 [1.18–4.16], and 2.40 [1.25–4.60], respectively. Furthermore, treating ALP as a categorical variable and conducting subgroup analyses further validated the robustness of our results. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that serum ALP, although found in various organs, is primarily located in the liver. Therefore, elevated ALP levels may signal a worsening prognosis when hepatocyte necrosis occurs [18, 19].

Integrating serum ALP levels with clinical information significantly enhanced the model's performance, with AUC values of 0.768 for ICU mortality, 0.759 for hospital mortality, and 0.767 for unfavorable neurological outcome. While these results suggest that including ALP enhances model performance, careful consideration is necessary regarding its direct application in clinical practice. Additionally, our analysis using ROC curves demonstrated that serum ALP exhibited comparable predictive accuracy for adverse outcomes when compared to APACHE II and SOFA scores. Both the APACHE II and SOFA scores are recognized for their prognostic capabilities in predicting mortality and poor neurological outcome following CA [20–23]. The inclusion of hepatic dysfunction makes the SOFA score especially relevant for clinical prognostic assessment in patients with ALF [24]. Although the APACHE II score remains prognostically relevant for patients with ALF or following liver transplantation, its predictive accuracy may be limited [25, 26]. Our findings indicate that among the three predictors, the SOFA score demonstrated the highest predictive efficacy, while the APACHE II score showed the lowest. Nonetheless, serum ALP continues to be a readily accessible and effective predictor.

Various mechanisms linking elevated serum ALP levels to poor outcomes in ALF following CA deserve consideration. Notably, serum ALP has been recognized as a surrogate marker of systemic inflammation, and multiple studies have reported an association between ALP and CRP [12, 27, 28]. Our study also demonstrated consistent findings, revealing a significant positive correlation between ALP and CRP levels (P < 0.05). After ROSC, PCAS induces a sepsis-like syndrome characterized by elevated inflammatory markers, including CRP, the resulting ALF further exacerbates the inflammatory response [18, 29]. Numerous studies have confirmed that elevated CRP levels are indicative of high mortality and unfavorable neurological outcome following CA, with the underlying mechanism linked to the inflammatory response rather than necessarily indicating the presence of an infection [30, 31]. Inflammation may thus explain the link between elevated serum ALP levels and poor outcomes. According to data from European Union transplant units, approximately 18% of ALF cases are attributed to pharmacological factors, with an increasing trend in recent years [32]. The use of various adrenaline and vasoactive drugs during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and post-resuscitation therapy can contribute to pharmacological liver injury and poorer outcomes in CA patients [33, 34]. In our study, higher ALP levels were observed in individuals who frequently or heavily used vasoactive drugs (P < 0.05). Therefore, pharmacological factors may provide another explanation for the correlation between elevated serum ALP levels and poor outcomes. However, even after adjusting for these factors, the association between ALP levels and adverse prognosis persisted, suggesting that this relationship operates through distinct mechanisms. Other mechanisms may also be at play, and future studies should investigate specific ALP isoenzymes to elucidate the pathophysiological links between serum ALP and poor outcomes.

Additionally, we observed that the high-level group had significantly lower blood glucose levels compared to the low-level group. Several factors may contribute to this finding. Firstly, following CA, the body's metabolic demands increase, particularly in the acute post-resuscitation phase [35]. Impaired liver function may hinder the liver's ability to supply adequate energy and metabolites, leading to higher energy expenditure and reduced serum glucose levels [36]. Secondly, the liver may experience direct damage from ischemia and reperfusion injury following CA, resulting in hepatocellular damage or necrosis and an increased release of liver enzymes such as ALP. Given the liver’s critical role in regulating glucose—through glycogen synthesis, catabolism, and gluconeogenesis—lower glucose levels may indicate significant liver dysfunction [37]. Therefore, the observed hypoglycemia in the high-level group, along with elevated liver enzymes and a significantly poorer outcomes, reinforces this possibility.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, it is a single-center observational and retrospective analysis of an existing database, which may limit the generalizability of our findings and hinder the ability to establish causal relationships. Secondly, despite adjusting for numerous potential confounders, we cannot entirely exclude the possibility of undetected confounders. Thirdly, our results are derived from a Belgian population, necessitating further validation in other populations. Lastly, the existing database only includes serum ALP measurements, without information on ALP isoforms, which limits our ability to infer the association of other ALP sources with increased mortality. However, it is important to note that, despite being single-center studies, the results remained consistent, indicating the robustness of the findings within the specific study populations.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that serum ALP may serve as a valuable marker for predicting the prognosis of patients with ALF following CA, although further confirmation of these findings is necessary.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Curve fitting of the lnand clinical prognosis in patients with ALF following CA.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Enrica Iesu et al. for sharing their data.

Abbreviations

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALF

Acute liver failure

- CA

Cardiac arrest

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- OR

Odds ratios

- CI

Confidence interval

- PCAS

Post-cardiac arrest syndrome

- IHCA

In-hospital cardiac arrest

- OHCA

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- TTM

Targeted temperature management

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- ROSC

Return of spontaneous circulation

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

- INR

International normalized ratio

- PT

Prothrombin time

- IABP

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- CRRT

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- CPC

Cerebral performance categories score

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- AUC

Area under the curve

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- LRT

Likelihood ratio test

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Author contributions

WL and YX planned and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LL and LC contributed to the data cleaning and statistical analysis. WL, CS, and LL revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding support received from Science and Technology Plan Project of Wenzhou Municipality (Y20220497).

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on request. Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.qv6fp83.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité d’Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire Erasme-ULB (P2017/264), but waived the need for informed consent because of its retrospective nature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Iesu E, Franchi F, Zama Cavicchi F, Pozzebon S, Fontana V, Mendoza M, et al. Acute liver dysfunction after cardiac arrest. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11): e0206655. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delignette MC, Stevic N, Lebossé F, Bonnefoy-Cudraz E, Argaud L, Cour M. Acute liver failure after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Resuscitation. 2024;197: 110136. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2024.110136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Curhan G, Pfeffer M, Sacks F, Thadhani R, Melamed ML, et al. Relation between alkaline phosphatase, serum phosphate, and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality. Circulation. 2009;120(18):1784–92. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan W, Yan M, Wang H, Xu Z. Associations of serum alkaline phosphatase level with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1217369. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1217369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeschke H. Reactive oxygen and mechanisms of inflammatory liver injury: present concepts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):173–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Q, Lu Z, Zhang X. A novel role of alkaline phosphatase in protection from immunological liver injury in mice. Liver. 2002;22(1):8–14. 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2002.220102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pike AF, Kramer NI, Blaauboer BJ, Seinen W, Brands R. A novel hypothesis for an alkaline phosphatase ‘rescue’ mechanism in the hepatic acute phase immune response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(12):2044–56. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Wang Y, Yao Q, Fan L, Meng L, Zheng N, et al. Alkaline phosphatase attenuates LPS-induced liver injury by regulating the miR-146a-related inflammatory pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101(Pt A): 108149. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siller AF, Whyte MP. Alkaline phosphatase: discovery and naming of our favorite enzyme. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(2):362–4. 10.1002/jbmr.3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poupon R. Liver alkaline phosphatase: a missing link between choleresis and biliary inflammation. Hepatology. 2015;61(6):2080–90. 10.1002/hep.27715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddhu S, Ma X, Baird B, Cheung AK, Greene T. Serum alkaline phosphatase and mortality in African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(11):1805–10. 10.2215/CJN.01560309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JH, Lee HS, Park HM, Lee YJ. Serum alkaline phosphatase level is positively associated with metabolic syndrome: a nationwide population-based study. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;500:189–94. 10.1016/j.cca.2019.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ndrepepa G, Xhepa E, Braun S, Cassese S, Fusaro M, Schunkert H, et al. Alkaline phosphatase and prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47(5):378–87. 10.1111/eci.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Wang W, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Wang A, Zhao X. Association between alkaline phosphatase and clinical outcomes in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 677696. 10.3389/fneur.2021.677696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Liu Z, Lu Q, Liu P, Lin X, Wang J, et al. Non-linear association between serum alkaline phosphatase and 3-month outcomes in patients with acute stroke: results from the Xi’an stroke registry study of China. Front Neurol. 2022;13: 859258. 10.3389/fneur.2022.859258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tujjar O, Mineo G, Dell’Anna A, Poyatos-Robles B, Donadello K, Scolletta S, et al. Acute kidney injury after cardiac arrest. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):169. 10.1186/s13054-015-0900-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Biarent D, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry Templates for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Circulation. 2015;132(13):1286–300. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Perez Ruiz Garibay A, Kortgen A, Leonhardt J, Zipprich A, Bauer M. Critical care hepatology: definitions, incidence, prognosis and role of liver failure in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):289. 10.1186/s13054-022-04163-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haarhaus M, Brandenburg V, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Stenvinkel P, Magnusson P. Alkaline phosphatase: a novel treatment target for cardiovascular disease in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(7):429–42. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Dejam A, Giberson T, Giberson B, Cristia C, et al. APACHE II scoring to predict outcome in post-cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84(5):651–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blatter R, Amacher SA, Bohren C, Becker C, Beck K, Gross S, et al. Comparison of different clinical risk scores to predict long-term survival and neurological outcome in adults after cardiac arrest: results from a prospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):77. 10.1186/s13613-022-01048-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda J, Kato S, Yano H, Nitta G, Kono T, Ikenouchi T, et al. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score predicts mortality and neurological outcome in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. J Cardiol. 2020;76(3):295–302. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pineton de Chambrun M, Bréchot N, Lebreton G, Schmidt M, Hekimian G, Demondion P, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock post-cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(12):1999–2007. 10.1007/s00134-016-4541-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehler M, Kokoska J, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with cirrhosis assessed by prognostic scoring systems. Hepatology. 2001;34(2):255–61. 10.1053/jhep.2001.26522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niewiński G, Starczewska M, Kański A. Prognostic scoring systems for mortality in intensive care units–the APACHE model. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46(1):46–9. 10.5603/AIT.2014.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell I, Bihari D, Chang R, Wendon J, Williams R. Earlier identification of patients at risk from acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(2):279–84. 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J, Song TJ, Song D, Lee HS, Nam CM, Nam HS, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase and phosphate in cerebral atherosclerosis and functional outcomes after cerebral infarction. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3547–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webber M, Krishnan A, Thomas NG, Cheung BM. Association between serum alkaline phosphatase and C-reactive protein in the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48(2):167–73. 10.1515/CCLM.2010.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adrie C, Adib-Conquy M, Laurent I, Monchi M, Vinsonneau C, Fitting C, et al. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation after cardiac arrest as a “sepsis-like” syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106(5):562–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000023891.80661.AD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer M, Wiberg S, Grand J, Kjaergaard J, Hassager C. Interleukin-6 receptor antibodies for modulating the systemic inflammatory response after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (IMICA): study protocol for a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, single-center, randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):868. 10.1186/s13063-020-04783-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Annborn M, Dankiewicz J, Erlinge D, Hertel S, Rundgren M, Smith JG, et al. Procalcitonin after cardiac arrest—an indicator of severity of illness, ischemia-reperfusion injury and outcome. Resuscitation. 2013;84(6):782–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Germani G, Theocharidou E, Adam R, Karam V, Wendon J, O’Grady J, et al. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure in Europe: outcomes over 20 years from the ELTR database. J Hepatol. 2012;57(2):288–96. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi X, Yu J, Pan Q, Lu Y, Li L, Cao H. Impact of total epinephrine dose on long term neurological outcome for cardiac arrest patients: a cohort study. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12: 580234. 10.3389/fphar.2021.580234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong ME, Tan EH, Ng FS, Panchalingham A, Lim SH, Manning PG, et al. Survival outcomes with the introduction of intravenous epinephrine in the management of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(6):635–42. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoaib M, Kim N, Choudhary RC, Yin T, Shinozaki K, Becker LB, et al. Increased plasma disequilibrium between pro- and anti-oxidants during the early phase resuscitation after cardiac arrest is associated with increased levels of oxidative stress end-products. Mol Med. 2021;27(1):135. 10.1186/s10020-021-00397-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneeweiss B, Pammer J, Ratheiser K, Schneider B, Madl C, Kramer L, et al. Energy metabolism in acute hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(5):1515–21. 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90159-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han HS, Kang G, Kim JS, Choi BH, Koo SH. Regulation of glucose metabolism from a liver-centric perspective. Exp Mol Med. 2016;48(3): e218. 10.1038/emm.2015.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Curve fitting of the lnand clinical prognosis in patients with ALF following CA.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request. Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.qv6fp83.