Abstract

Background:

Understanding pathways to dual diagnosis (DD) care will help organize DD services and facilitate training and referral across healthcare sectors.

Aim:

The aim of our study was to characterize the stepwise healthcare and other contacts among patients with DD, compare the characteristics of the first contact persons with common mental disorder (CMD) versus severe mental illness (SMI), and estimate the likelihood of receiving appropriate DD treatment across levels of contacts.

Methods:

This cross-sectional, descriptive study in eight Indian centers included newly enrolled patients with DD between April 2022 and February 2023. The research spans varied geographic regions, tapping into regional variations in disease burden, health practices, and demographics. The study categorized healthcare contacts by using the WHO Pathways Encounter Form.

Results:

The sample (n = 589) had a median age of 32 years, mostly males (96%). Alcohol was the most common substance; SMI (50.8%) and CMD were equally represented. Traditional healers were a common first contact choice (18.5%); however, integrated DD care dominated subsequent contacts. Assistance likelihood increased from the first to the second contact (23.1% to 62.1%) but declined in subsequent contacts, except for a significant rise in the fifth contact (97.4%). In the initial contact, patients with CMD sought help from public-general hospitals and private practitioners for SUD symptoms; individuals with SMI leaned on relatives and sought out traditional healers for psychiatric symptoms.

Conclusion:

Recognizing the cultural nuances, advocating for integrated care, and addressing systemic challenges pave the way to bridge the gap in DD treatment.

Keywords: Dual diagnosis, help seeking, India, multicentric, substance use disorder

INTRODUCTION

Dual diagnosis (DD) is defined as the concurrent presence of substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric disorders. Approximately 50%–60% of those with either SUD or any mental illness have DD.[1] Studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) demonstrated a similar high co-occurrence. For instance, a study from Nigeria showed that two-thirds of patients with SUD had co-occurring schizophrenia spectrum disorder.[2] Data on the prevalence of DD in India lacks any national estimate.[3] Different estimates across centers have suggested a prevalence ranging from 11% to 40%.[4,5,6,7,8,9]

Persons with DD have higher morbidity and mortality. There is a higher incidence of homelessness, social exclusion, and unemployment.[10] A recent retrospective cohort study from India in patients hospitalized for AUD showed that severe mental illness (SMI) doubled the odds of hospital readmission over 5 years.[4] Individuals with DD are more likely to relapse to substance misuse and psychiatric symptoms, contributing to the poor course and outcome of both conditions.[11,12] Treating individuals with DD is challenging due to complex clinical and psychosocial needs. The reluctance stems from fear of drug interactions, limited training, and compartmentalized services, leading to underreporting and exclusion.[13] Although different models of DD care are documented in high-income countries,[14,15,16] these are resource-intensive and thus less sustainable in LMICs.[17]

Nevertheless, integrated DD care might be more favorable in terms of service users’ experience and treatment outcomes.[16] A review from India[3] lamented the lack of provision of a uniform, evidence-based system of DD care, even in tertiary care settings.

In India, the treatment gaps for mental illness and SUD are between 75% and 85%.[18,19] A serious lack in the number of trained mental health professionals, poor coverage of mental healthcare at district-level hospitals, and limited awareness and high stigma among service providers and users contribute to the treatment gap.[18] Despite four decades of a national mental health program, the treatment gap remains high for individuals with mental illness. The gap is likely greater for those with DD due to the lack of a specific care policy.

Pathways to care, which map sequential help-seeking behavior and document the care received during those encounters, might help understand the DD care needs.[20] Pathways of help-seeking are the critical link between the onset of problems and the provision of health care.[21] Therefore, DD care pathways may also help clinical decision-making and effective service delivery. A study of help-seeking pathways assumes more importance in India because mental healthcare is delivered by various service organizations.[18] In addition to public healthcare, it has a dominant private for-profit healthcare system. The accessibility and availability of mental healthcare and the type of healthcare organizations also differ across states.[18] Hence, a better understanding of pathways to DD care, preferably from multiple sites across the country, will help organize DD services and facilitate training and referral.

Moreover, no previous studies from India or elsewhere have examined care pathways for persons with DD. However, studies among patients with mental illness showed different help-seeking pathways from anxiety and depressive disorders versus psychosis. The former group seeks help from primary care, whereas the latter prefers mental healthcare services.[22] Previous reviews showed a different care-seeking pattern in LMICs versus high-income countries.[23]

The aim of our multisite study from an LMIC was to 1) characterize the step-wise healthcare and other contacts among patients with DD, 2) compare the characteristics of the first contacts persons with common mental disorder (CMD) versus SMI, and 3) estimate likelihood of receiving appropriate DD treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study spanned nine Indian centers, covering northern (n = 2), western (n = 1), central (n = 2), eastern (n = 3), and north-eastern (n = 1) states and union territories. The number of participants from the northern, western, eastern, central, and northeast centers was 54, 15, 279, 226, and 15, respectively. Please see Supplementary Figure 1 (369.3KB, tif) for further details. All study centers provide integrated DD care; however, these are structurally located within the tertiary care SUD service (n = 4) or mental health service (n = 4). Teams in tertiary care SUD or mental health services provided integrated DD care. State-wise analysis revealed mental disorder burden variations, potentially linked to sociodemographic index (SDI) differences (India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2020).[24] Substance use patterns also varied regionally (Ambekar et al., 2019).[19] Opioid prevalence was high in the north and northeast, while the east and central regions had more alcohol and cannabis use. Finally, mental health service organizations and coverage differ in these states.[18] Ethics approval was obtained from each institute, and data collection occurred between April 2022 and February 2023, with varying study periods due to approval and administrative differences.

Participants

Consecutive newly enrolled patients over 18 years seeking treatment from any of the study sites during the prespecified period were eligible for the study. All participants had a substance dependence diagnosis and a diagnosis of other mental disorders per the International Classification of Disease 10th version.[25] Patients with only tobacco use disorder and not willing to provide informed consent were excluded. Qualified psychiatrists made the diagnosis. This study was a subgroup analysis of a larger study on patients with SUDs.

Variables

We defined eight healthcare contact levels based on structural, functional, and cost factors. Mental health and addiction services, with or without integrated DD care, were classified, along with traditional informal care and private-for-profit healthcare. Other public healthcare categories are outlined in Table S1. Demographic and clinical variables were collected, including age, sex, socioeconomic status, substance use details, psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and treatment initiation factors. Symptoms leading to healthcare contact were categorized into substance use disorder (SUD), mental health, both, or other symptoms. Treatment types were divided into five categories, with pharmacological treatment further categorized for SUD, mental illness, or both. Rural-urban status was determined using 2011 census data. Comorbid medical illnesses were recorded from health records. Mental illnesses were classified as CMD (anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, dysthymia) and SMI (psychosis, bipolar disorder, recurrent depression). The rationale for this distinction is the different severity, presentation, course, outcome, and treatment needs of these two patient groups.[22] These differences might contribute to different help-seeking behavior. We compared the healthcare contact characteristics of those with CMD versus SMI.

Table S1:

Glossary of terms and description of different treatment services

| Public-funded addiction services or de-addiction centers (DACs) | Government-funded addiction clinics/opioid substitute centers/buprenorphine substitution centers/detoxification centers. Psychiatrists and medical officers run these centers with experience in addiction treatment. However, integrated care is not expected in these centers. |

|---|---|

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | Centers are funded by the government and run by psychiatrists/addiction psychiatrists. In our study, these represent tertiary care treatment facilities such as the Center for Addiction Psychiatry of CIP Ranchi, DTC PGIMER Chandigarh, Department of Addiction Medicine, LGBRIMH, and PGIMS Rohtak. Integrated treatment is available in these centers. |

| Mental health services with integrated addiction services (MHSI) | These centers are funded by the government and run by psychiatrists (at times addiction psychiatrists). In our study, it includes the psychiatry department of tertiary care treatment facilities such as AIIMS Patna, AIIMS Jodhpur, and AIIMS Bhubaneswar. Integrated treatment is available in these centers. Integrated treatment is available in these centers. |

| Mental health services (MHS) | Government-funded psychiatric hospital. These centers are run by psychiatrists and medical officers with OPD and IPD facilities. Often, these centers lack specialist addiction services. So, integrated care is not expected in these centers. |

| Religious/Native practices (RNP) | Religious and native healing practices encompass a wide range of spiritual approaches. These practices are deeply rooted in the beliefs and traditions of various cultures and often involve rituals, ceremonies, and natural remedies. Some examples include faith healing, shamanic healing, AYUSH, and crystal healing. These practices may involve prayer, herbal remedies, rituals, etc. |

| General Hospital (GH)/Emergency services (ES)/Primary health centers (PHC) | Are government-funded Primary and secondary level care. General hospitals sometimes have in-house psychiatrists and run Psychiatry OPD. Whereas Primary Health Centers, emergency services of GH lacks specialist psychiatrist/addiction specialist. |

| Private medical facilities (PvtM) | Are run by private enterprises and involve general physicians and general surgeons but not psychiatrists. |

| Private psychiatric/DAC (PvtP) | Non-government psychiatric clinic/psychiatric nursing home/addiction clinics/opioid substitute centers/detoxification centers. These centers are run by psychiatrists and medical officers (with or without experience in addiction treatment). Integrated care may or may not be available in these centers. |

We created a proxy variable named “likelihood of being helped.” Those who contacted integrated DD care were considered as “being helped.”[16]

Data sources and measurement

The Pathway Study Encounter Form by the WHO collaborative study[26] was used in our study. It is a culture-neutral questionnaire designed to systematically assess sources of care used by patients before consulting a mental health professional. It has been used for Indian patients with SUDs.[6,27] We have included minor changes made by Balhara et al.[6] and Bhad et al.[27] into the original form to make it more appropriate for our study sample.

Trained mental healthcare professionals collected information.

All data were collected in real time on a Google form. DM, TM, and AG periodically checked for incomplete and incorrect/invalid entries.

Bias

Our study might have a selection bias because patients seeking treatment in the tertiary care integrated DD care might differ from those seeking treatment from other healthcare or informal sectors and patients with DD living in the community. Our study can only draw inferences for the former group of persons with DD. By consecutive sampling, we aimed to reduce the selection bias; however, the systematic difference in the patients’ characteristics might still need to be addressed. Even random sampling would not have addressed this concern. We enquired about the history of sequential healthcare contacts, which might be subjected to recall bias.

Study size

This was a descriptive, exploratory study, and we performed no power calculation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean, median, and standard deviation/interquartile range for continuous variables. Group comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Independent t-test (two groups) or its non-parametric equivalent, the Mann-Whitney U test, made similar comparisons for the continuous variables. The Chi-square test compared the “likelihood of being helped” between healthcare contacts. The significance level was kept at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 1920 patients were approached. We excluded 303 patients for various reasons (time constraints cited by patients = 113, did not consent = 38, only tobacco use disorder = 19, had severe withdrawal symptoms = 85, had symptoms of intoxication = 48). We also excluded 1617 with only SUD diagnosis from the analysis for this work. Pathways to care for only the SUD population have been published separately.[28] There are several reasons for creating separate reports for SUD and DD. First, the pathways to seeking care are notably different between these groups. Merging them would increase heterogeneity and make our findings harder to interpret. Second, for patients with DD, the definition of healthcare contacts needs adjustment. For instance, mental health facilities at the tertiary level with integrated SUD treatment, either functionally or structurally, should be classified as providing integrated care for DD. This integration is less relevant for individuals with only SUD. Third, distinct care pathways carry different clinical and policy implications for patients with SUD versus those with DD.

Hence, 599 patients with DD were included in this study; however, the first contact information was available for 589 patients, and the final analysis was done for these 589 patients.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

Study participants, with a median age of 32 (IQR: 15–77) years, were predominantly male (96%) with intermediate education (median: 12 years; IQR: 8–15 years). Most were married (60%) and employed (78%). Over half were non-indigenous (57.4%), rural dwellers (61.6%), and from nuclear families (52.8%). Alcohol dependence was prevalent (68.4%), followed by tobacco and cannabis (61.5% and 51.8%). Opioid dependence was reported by 25.6%. Psychotic spectrum disorders (39.4%) were common, with depressive, anxiety, and bipolar spectrum disorders accounting for 26.2%, 22.2%, and 11.2%, respectively. SMI constituted 50.8%, while CMD made up 49.2%. Furthermore, 16.8% reported comorbid medical illnesses. For further details, please refer to Table 1.

Table 1:

Details of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (n=588)

| Variable | Median (IQR)/n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years (n=588) | 32.0 (Range: 25–41) |

| Years of education (n=589) | 12.0 (Range: 8–15) |

| Gender (n=589) | |

| Male | 565 (95.9) |

| Female | 24 (4.1) |

| Indigenous population (n=589) | |

| No | 338 (57.4) |

| Yes | 223 (37.9) |

| Not known | 30 (4.8) |

| Marital status (n=589) | |

| Married | 353 (59.9) |

| Separated | 23 (3.9) |

| Single | 208 (35.3) |

| Widowed | 5 (0.8) |

| Employment status (n=589) | |

| Employed | 459 (77.9) |

| Unemployed | 130 (22.1) |

| Locality (n=589) | |

| Rural | 363 (61.6) |

| Urban | 219 (37.2) |

| Unknown | 7 (1.2) |

| Religion (n=589) | |

| Hindu | 483 (82.0) |

| Islam | 69 (11.7) |

| Sikh | 16 (2.7) |

| Others/data absent | 21 (3.6) |

| Family type (n=589) | |

| Nuclear | 311 (52.8) |

| Joint/Extended | 269 (45.7) |

| Others/Not known | 9 (1.5) |

| Socioeconomic status (Modified Kuppuswamy) (n=520) | |

| Upper | 21 (4.0) |

| Upper middle | 238 (45.8) |

| Lower middle | 121 (23.3) |

| Upper lower | 127 (24.4) |

| Lower | 13 (2.5) |

| Duration of substance use (months) (n=583) | 84 (48–180) |

| Duration of substance dependence (months) (n=575) | 46 (25–95) |

| Duration of mental health symptoms (months) (n=575) | 28 (12–48) |

| Primary substance (n=589) | |

| Alcohol | 403 (68.4) |

| Cannabis | 77 (13.1) |

| Opioids | 67 (11.4) |

| Tobacco | 26 (4.4) |

| Sedatives | 14 (2.3) |

| Others | 2 (0.4) |

| Profile of active dependence (n=589) | |

| Alcohol dependence | 399 (67.7) |

| Tobacco dependence | 362 (61.5) |

| Cannabis dependence | 305 (51.8) |

| Opioids dependence | 151 (25.6) |

| Sedative dependence | 38 (6.5) |

| Emergency reception visit | |

| Yes | 55 (9.3) |

| No | 135 (22.9) |

| Not known | 399 (67.7) |

| Conflict with law | |

| Yes | 16 (2.7) |

| No/Not known | 573 (97.3) |

| First symptom | |

| Compulsion | 336 (57.0) |

| Withdrawal | 123 (20.9) |

| Tolerance | 39 (6.6) |

| Loss of control | 30 (5.1) |

| Use despite harm | 21 (3.6) |

| Neglect of pleasurable activities | 9 (1.5) |

| Craving | 4 (0.7) |

| Psychiatric Illness | |

| Psychotic Spectrum (F1X.5 & F20–F29) | 235 (39.9) |

| Depressive Spectrum (F32–F39) | 155 (26.3) |

| Anxiety Spectrum (F40–F49) | 135 (22.9) |

| Bipolar Spectrum (F30–F31) | 64 (10.9) |

| Comorbid Medical illness | |

| Present | 99 (16.8) |

| Absent | 170 (28.9) |

| Absent/Not known | 320 (54.3) |

Details of the pathways to care for DD disorders

1st contact details

Among 589 first-contact participants, 18.5% chose religious/native practices, followed by specialized addiction services with integrated care (17.3%) and govt general hospital/emergency services (15%). Private medical and private psychiatric services each attracted 8.8% of patients. Mental health services and primary health care were contacted by 7.0% and 6.6% of patients, respectively. Initiators were mainly relatives (64.7%), patients themselves (25.3%), and psychiatric symptoms-triggered contact (31.2%). Addiction-related symptoms prompted 21.9%, and a combination led to 25.1% of cases. Pharmacotherapy was received by 57%, and 7.6% underwent a combination of medication and psychosocial interventions.

2nd contact details

The median time between first and second contacts was 14 months (IQR: 12–38 months). Among 430 patients with a second contact, 48.6% sought specialized addiction services, followed by government general hospitals/emergency services (14.4%) and mental health services with integrated addiction services (13.5%). Relatives initiated 45.1% of contacts, patients 30.9%, and medical practitioners 12.5%. Psychiatric symptoms prompted 2/5th of contacts, while addiction-related and combined symptoms each accounted for 1/5th. Most patients (60%) received pharmacotherapy, and 30% had a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial interventions.

3rd contact details

The median time between second and third contacts was 12 months (IQR: 1.75–35 months). Among 158 patients, 43.7% contacted specialized addiction services, 25.9% general hospitals/emergency services, and 5.1% mental health services with integrated services. Relatives initiated 39.2% of contacts, patients 30.4%, and healthcare providers 29.1%. Over one-fifth sought help for unrelated medical/surgical symptoms. Nearly 70% received pharmacological treatment exclusively, and 23% had a combination of medication and psychosocial interventions.

4th contact details

The time between the third and fourth contact was 4 months (IQR: 1.25–28.5 months). Among 79 patients, 40.5% visited specialized addiction services, 8.9% mental health services, and 27.8% government general hospitals. Mental healthcare specialists initiated 27.8% of contacts, patients 24.1%, medical practitioners 24.1%, and relatives 22.5%. Addiction-related reasons prompted 44.3% of contacts. Pharmacological treatment alone was received by 58%, and 37% had a combination of pharmacological and psychological treatment.

5th contact details

The median duration between the fourth and fifth contacts was 1 month (IQR: 1–5 months). Among 39 patients with a fifth contact, almost all sought treatment from specialized addiction services (SAS). Patients, relatives, and healthcare providers initiated the contact in about one-third of cases, with significant involvement from mental healthcare specialists and medical practitioners. Nearly all patients received medical care, and over two-thirds also had additional psychosocial intervention. For further details, please refer to Table 2.

Table 2:

Details related to stepwise treatment contact (1st to 5th contact)

| Variable | Number (%) (Range)/n (%) |

|---|---|

| First contact (n=589) | |

| Religious/Native Practices (RNP) | 109 (18.5) |

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | 102 (17.3) |

| Govt general hospital/Emergency service | 86 (14.6) |

| Private psychiatrist/Private DAC | 52 (8.8) |

| Private Medical practitioner (PvtM) | 52 (8.8) |

| Mental health service | 41 (7.0) |

| PHC | 39 (6.6) |

| Mental health services with integrated addiction services (MHSI) | 34 (5.8) |

| Community health worker/Pharmacist/Social worker/Self-medication/Others | 28 (4.7) |

| Public-funded addiction services or de-addiction center (DAC) | 26 (4.4) |

| Who initiated the first contact? | |

| Relatives/friends | 381 (64.7) |

| Patient self | 149 (25.3) |

| Workmate/employers | 43 (4.3) |

| Medical practitioners | 27 (4.6) |

| Not available | 13 (2.2) |

| Others (Neighbors, police) | 5 (0.9) |

| What symptoms led to the first contact? | |

| Psychiatric symptoms-related | 184 (31.2) |

| Addiction-related | 129 (21.9) |

| Mixed | 148 (25.1) |

| Others (Medical, surgical, unrelated) | 44 (7.5) |

| Not available | 84 (14.3) |

| Nature of treatment at first contact (n=589) | |

| Pharmacological only | 334 (56.7) |

| Psychosocial only | 23 (3.9) |

| Religious/Native | 109 (18.5) |

| Pharmacological and Psychosocial | 45 (7.6) |

| Referral | 16 (2.7) |

| Record NA | 62 (10.5) |

| Pharmacological Break-up (n=158) | |

| Addiction-related | 81 (51.3) |

| Psychiatry-related | 47 (29.7) |

| Both | 30 (19.0) |

| Second contact (n=430) | |

| Who was seen? Who initiated the third contact? |

|

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | 209 (48.6) |

| Govt general hospital/Emergency service | 62 (14.4) |

| Mental health services with integrated addiction services (MHSI) | 58 (13.5) |

| Private practitioner (medical) | 31 (7.2) |

| Private psychiatrist/Private DAC | 21 (4.9) |

| Mental health service | 20 (4.6) |

| Religious/Native practices (RNP) | 10 (2.3) |

| Public-funded addiction services (DAC) | 6 (1.4) |

| Others (self-medication/community health work/PHC/ES) | 13 (3.0) |

| Who initiated the first contact? | |

| Relatives/friends | 261 (60.7) |

| Patient self | 89 (20.7) |

| Medical practitioners | 38 (8.3) |

| Mental healthcare specialists | 18 (4.2) |

| Others (Neighbors/police/workmates/employers) | 11 (2.5) |

| Not available | 13 (2.9) |

| What symptoms led to the second contact? | |

| Psychiatric symptoms-related | 167 (38.8) |

| Addiction-related | 92 (21.4) |

| Mixed | 84 (19.5) |

| Others (Medical, surgical, unrelated) | 44 (10.2) |

| Not available | 43 (10.0) |

| Nature of treatment at second contact | |

| Pharmacological only | 258 (60.0) |

| Psychosocial only | 3 (0.7) |

| Pharmacological and psychosocial | 129 (30.0) |

| Referral | 11 (2.5) |

| Traditional and others | 11 (2.5) |

| Record NA | 18 (4.2) |

| Pharmacological Break-up (n=191) | |

| Addiction-related | 98 (51.3) |

| Psychiatry-related | 64 (33.5) |

| Both | 29 (15.2) |

| Third contact (n=158) | |

| Who was seen? | |

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | 69 (43.7) |

| Govt general hospital/Emergency service | 41 (25.9) |

| Mental health services with integrated services (MHSI) | 8 (5.1) |

| Public-funded addiction services (DAC) | 7 (4.4) |

| Mental health service | 7 (4.4) |

| Others (Traditional, private practitioner, psychiatry, etc.) | 25 (15.8) |

| Who initiated the third contact? | |

| Relatives/friends | 62 (39.2) |

| Patient self | 48 (30.4) |

| Medical practitioners | 27 (17.1) |

| Mental healthcare specialists | 19 (12.0) |

| Others | 2 (1.3) |

| What symptoms led to the third contact? | |

| Addiction-related | 60 (38.0) |

| Psychiatric symptoms-related | 40 (25.3) |

| Mixed | 21 (13.3) |

| Others (Medical, surgical, unrelated) | 33 (20.9) |

| Not available | 4 (2.5) |

| Nature of treatment at third contact | |

| Pharmacological only | 110 (69.6) |

| Psychosocial only | 3 (1.9) |

| Pharmacological and Psychosocial (both) | 37 (23.4) |

| Traditional and others | 7 (4.4) |

| Record NA | 1 (0.6) |

| Pharmacological | |

| Addiction-related only | 18 (32.1) |

| Break-up (n=56) | |

| Psychiatry-related only | 14 (25.0) |

| Both | 24 (42.9) |

| Fourth contact (n=79) | |

| Who was seen? | |

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | 32 (40.5) |

| Govt general hospital/Emergency service | 22 (27.8) |

| Addiction services | 5 (6.3) |

| Mental health service | 6 (7.6) |

| Mental health services with integrated services (MHSI) | 7 (8.9) |

| Others | 7 (9.2) |

| Who initiated the fourth contact? | |

| Mental healthcare specialists | 22 (27.8) |

| Patient self | 19 (24.1) |

| Medical practitioners | 19 (24.1) |

| Relatives | 18 (22.8) |

| Neighbor | 1 |

| What symptoms led to the fourth contact? | |

| Addiction-related | 35 (44.3) |

| Psychiatric symptoms-related | 17 (21.5) |

| Mixed | 11 (13.9) |

| Others (Medical, surgical, unrelated) | 14 (17.7) |

| Not available | 2 (2.5) |

| Nature of treatment at fourth contact | |

| Pharmacological only | 46 (58.2) |

| Psychosocial only | 1 (1.3) |

| Pharmacological and psychosocial both | 29 (36.7) |

| Record NA | 1 |

| Fifth contact (n=39) | |

| Who was seen? | |

| Specialized addiction services with integrated care (SAS) | 35 (89.7) |

| Others | 4 |

| Who initiated the fifth contact? | |

| Mental healthcare specialists | 19 (48.7) |

| Medical practitioners | 9 (23.1) |

| Others | 11 (28.2) |

| What symptoms led to the fifth contact? | |

| Addiction-related only | 29 (74.4) |

| Psychiatric symptoms-related only | 2 |

| Mixed | 8 |

| Nature of treatment at fifth contact | |

| Pharmacological only | 11 (28.2) |

| Psychosocial only | 1 (2.6) |

| Pharmacological and psychosocial (both) | 27 (69.2) |

The likelihood of receiving appropriate assistance in subsequent contacts

Receiving integrated services (SAS or MHSI) significantly increased from the first (23.1%) to the second contact (62.1%) (χ2 158.15, P < 0.00001). However, assistance declined between the 2nd and 3rd contacts (49.4%) (χ2 7.717, P = 0.005). The 3rd and 4th contacts showed consistent assistance (49.4% vs. 49.4%, χ2 0, P = 1). Significantly higher help rates were observed in the 5th contact compared to the 4th (97.4% vs. 49.4%, χ2 26.6, P < 0.00001). For details, see Supplementary Table S2.

Table S2:

The likelihood of appropriate assistance in subsequent contacts

| Reached Integrated care | Did not reach Integrated care | Likelihood of reaching integrated care | Chi-square, P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Contact | 136 | 453 | 23.1% | χ2=158.15, P<0.00001 |

| Second Contact | 267 | 163 | 62.1% | |

| Second Contact | 267 | 163 | 62.1% | χ2=7.717, P=0.005 |

| Third Contact | 78 | 80 | 49.4% | |

| Third Contact | 78 | 80 | 49.4% | χ2=0, P=1 |

| Fourth Contact | 39 | 40 | 49.4% | |

| Fourth Contact | 39 | 40 | 49.4% | χ2=26.6, P<0.00001 |

| Fifth Contact | 38 | 1 | 97.4% |

Comparison of the first contact characteristics between CMD and SMI

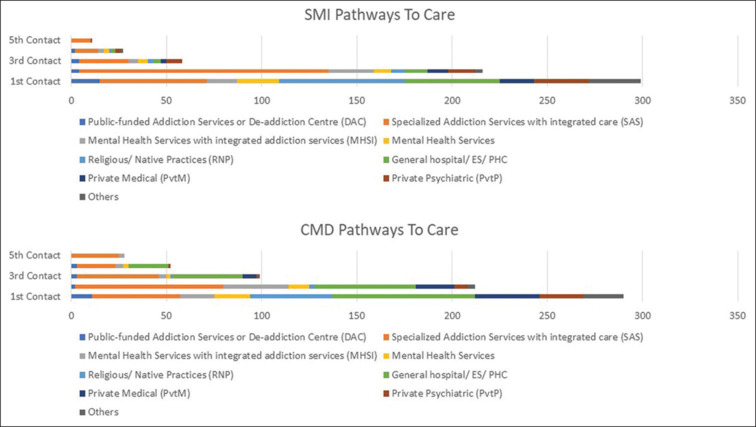

In initial contacts, patients with CMD favored government general hospitals (21.7% vs. 7.7%) and private medical practitioners (11.7% vs. 6.0%) compared to SMI patients. SMI individuals were more inclined toward native religious practices (22.1% vs. 14.8%). In the SMI group, 84.9% of first contacts were initiated by relatives or friends, while in the CMD group, patients (44.0%) and their relatives or friends (46.8%) led the first contact. Addiction-related symptoms prompted first contact in 35.2% of CMD cases, while psychiatry-related symptoms played a significant role (51.2%) in the SMI group. Treatment types were generally similar, but SUD medications were more frequently prescribed in the CMD group. For further details, please refer to Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3:

Comparison of the first contact characteristics between common mental disorder (CMD) and severe mental illness (SMI)

| CMD | SMI | Statistics (Chi-square/M-W test/K-W test, P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of first contact (n=589) | |||

| Public addiction treatment facility | 11 (1.9) | 15 (2.5) | 35.3 (<0.001) |

| Govt. general hospital | 63 (10.7) | 23 (3.9) | |

| Mental health services | 19 (3.2) | 22 (3.7) | |

| Native religious practices | 43 (7.3) | 66 (11.2) | |

| Private medical practitioner | 34 (5.8) | 18 (3.1) | |

| Private psychiatrist/DAC (PvtP) | 23 (3.9) | 29 (4.9) | |

| Integrated care | 64 (10.9) | 72 (12.2) | |

| Others | 33 (5.6) | 54 (9.2) | |

| Who initiated the first contact? (n=576) | |||

| Self | 125 (21.7) | 24 (4.2) | 103.9 (<0.001) |

| Relatives/friends | 133 (23.1) | 248 (43.1) | |

| Others | 26 (4.5) | 20 (3.5) | |

| Symptoms leading to first contact (n=505) | |||

| Psychiatry-related | 59 (11.7) | 125 (24.8) | 80.1 (<0.001) |

| Addiction-related | 92 (18.2) | 37 (7.3) | |

| Mixed | 69 (13.7) | 79 (15.6) | |

| Others | 41 (8.1) | 3 | |

| Treatment received? Pharmacological vs. Psychosocial vs. Both vs. (n=484) | |||

| Pharmacological only | 189 (39.0) | 145 (30.0) | 4.9 (p=0.178) |

| Psychosocial only | 11 (2.3) | 12 (2.5) | |

| Both | 19 (3.9) | 26 (5.4) | |

| None | 50 (10.3) | 32 (6.6) | |

| Medications for psychiatric disorder received or not (n=162) | |||

| Received | 32 (19.8) | 45 (27.8) | 13.875 (p<0.001) |

| Not received | 60 (37.0) | 25 (15.4) | |

| Medications for SUD received or not (n=162) | |||

| Received | 73 (45.1) | 38 (23.5) | 11.576 (p=0.001) |

| Not received | 19 (11.7) | 32 (19.8) | |

| The mean time taken for the first visit to integrated services (in months) | 34.2 (SD=48.3) | 27.4 (SD=37.7) | 0.041 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of the contact characteristics between severe mental illness (SMI) and common mental disorder (CMD)

Comparison of the second and third contact characteristics between CMD and SMI

In the subsequent contacts, people with CMD were more likely to continue to seek treatment at government general hospitals; however, treatment seeking for SMI leaned significantly toward integrated care (P < 0.0001). Contact initiation continued to be dominated by the family and relatives of those with SMI. In contrast, the patients and their treating doctors initiated the second and third contacts for those with CMD (P < 0.0001). The symptoms leading to the second and third contacts showed a similar pattern as the first contact (P < 0.001). The patients with SMI were still less likely (P < 0.001) to receive medications for SUD in their second contact with healthcare. The proportion increased in the third contact, but only one in four received it (P = 0.054). Only in the third contact did a significantly more significant (P = 0.005) proportion of patients receive treatment for psychiatric disorders. Please see the Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, and Figure 1 for further details.

Supplementary Table 3:

Comparison of the second contact characteristics between Common Mental Disorder (CMD) and Severe Mental Illness (SMI)

| Comparison of the second contact characteristics between common mental disorder (CMD) and severe mental illness (SMI) | CMD [n (%)] | SMI [n (%)] | Statistics (Chi-square, P) Fisher’s exact wherever applicable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of second contact (n=430) | |||

| Govt. general hospital | 53 (12.3) | 12 (2.8) | 38.2, P<0.0001** |

| Mental health services | 11 (2.6) | 9 (2.1) | |

| Private medical practitioner | 20 (4.6) | 11 (2.6) | |

| Integrated care | 112 (26.0) | 155 (36.0) | |

| Others | 18 (4.2) | 29 (6.7) | |

| Who initiated the second contact? (n=418) | |||

| Self | 69 (16.5) | 20 (4.8) | 60.8, P<0.0001** |

| Relatives/Friends | 95 (22.7) | 170 (40.7) | |

| Medical/Mental Health Practitioner | 41 (9.8) | 15 (3.6) | |

| Others | 3 (0.7) | 5 (1.2) | |

| Symptoms leading to second contact (n=387) | |||

| Psychiatry-related | 47 (12.1) | 120 (31.0) | 95.7 (<0.001**) |

| Addiction-related | 67 (17.3) | 25 (6.5) | |

| Mixed | 29 (7.5) | 55 (14.2) | |

| Others | 42 (10.8) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Treatment received? Pharmacological vs. Psychosocial vs. Both (n=390) | |||

| Pharmacological only | 151 (38.7) | 107 (27.4) | 22.2, P<0.001** |

| Psychosocial only | 1 (0.25) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Both | 43 (11.0) | 86 (22.0) | |

| Medications for psychiatric disorder received or not (n=192) | |||

| Received | 28 (14.6) | 65 (33.8) | 2.7, P=0.1 |

| Not received | 41 (21.3) | 58 (30.2) | |

| Medications for SUD received or not (n=162) | |||

| Received | 59 (30.7) | 10 (5.2) | 18.0, P<0.0001** |

| Not received | 68 (35.4) | 55 (28.6) |

**P<.05 is significant

Supplementary Table 4:

Comparison of the third contact characteristics between Common Mental Disorder (CMD) and Severe Mental Illness (SMI)

| Comparison of the third contact characteristics between common mental disorder (CMD) and severe mental illness (SMI) | CMD [n (%)] | SMI [n (%)] | Statistics (Chi-square, P), Fisher’s exact wherever applicable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of third contact (n=158) | |||

| Govt. general hospital | 37 (23.4) | 4 (2.5) | 29.0, P<0.0001 |

| Private Medical practitioner | 7 (4.4) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Integrated care | 47 (29.7) | 31 (19.6) | |

| Others | 8 (5.1) | 21 (13.3) | |

| Who initiated the third contact? (n=158) | |||

| Self | 37 (23.4) | 11 (7) | 31.7, P<0.0001 |

| Relatives/Friends | 22 (13.9) | 42 (26.6) | |

| Medical/Mental Health Practitioner | 40 (25.3) | 6 (3.8) | |

| Symptoms leading to third contact (n=154) | |||

| Psychiatry-related | 12 (7.8) | 28 (18.2) | 53.7 (<0.001) |

| Addiction-related | 41 (26.6) | 19 (12.3) | |

| Mixed | 12 (7.8) | 9 (5.8) | |

| Others | 33 (21.4) | 0 | |

| Treatment received? Pharmacological vs. Psychosocial vs. Both (n=146) | |||

| Pharmacological only | 74 (50.7) | 32 (22.0) | 2.1, P=0.15 |

| Psychosocial only | 0 | 3 (2.1) | |

| Both | 21 (14.4) | 16 (10.9) | |

| Medications for psychiatric disorder received or not (n=56) | |||

| Received | 27 (48.2) | 15 (26.8) | 7.7, P=0.005 |

| Not received | 3 (5.3) | 11 (19.6) | |

| Medications for SUD received or not (n=56) | |||

| Received | 17 (30.4) | 13 (23.2) | 3.7, P=0.054 |

| Not received | 21 | 5 (8.9) |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, ours might be the first attempt to describe the help-seeking behavior of patients with DD. Our results revealed that one in five persons with DD sought initial help from traditional/religious healers. The percentage was significantly higher for those with SMI than those with CMD. However, in subsequent contacts, help-seeking from traditional healers reduced steeply. Except for the initial contact, integrated DD care comprised the major healthcare contact, ranging from 40% to 80%. A substantial proportion, 1 in 4–6 persons, contacted secondary and emergency public healthcare care. Patients with CMD (vs. SMI) were likely to enroll in general medical and private for-profit healthcare systems. However, private healthcare contributed to 8%–12% of contacts in our study sample. The time lags between the first three contacts were more than 1 year. Although family members initiated help-seeking, we observed a steady increase in self-initiated care contacts and referrals by medical/mental health professionals for subsequent healthcare contacts.

Initial help-seeking from traditional healers reflects cultural practice and social norms. The role of traditional healers in delivering mental healthcare is well-known in Southeast Asia.[29] Complementary and alternative medicine practitioners occupy the vacuum created by the enormous treatment gap in these countries. Although less prevalent in terms of the absolute percentage, the major proportion of our study population chose to consult traditional healers, suggesting they contribute significantly to care pathways in Indian patients with DD, especially those with SMI. Therefore, the mental health policy must aim to integrate traditional practices and medical healthcare. Training, support, and linkage with traditional healers should reduce the time lag between traditional and medical healthcare contacts. A study from Ghana and Nigeria showed that it is feasible to train traditional and faith healers to deliver care for patients with SMI collaboratively; moreover, collaborative care is more effective and cost-effective than traditional models of care.[30]

Integrated DD care not only improves outcomes for mental health and substance use but is also a cost-effective strategy.[31] Evidence suggests the sustainability of integrated treatment programs even after the withdrawal of the research support.[32] Hence, it is encouraging to see integrated DD care as a major healthcare contact in our study population, reflecting these services’ acceptability, appropriateness, and perceived effectiveness. However, integrated DD care requires training, staffing, financing, high fidelity, and agency leadership.[33] Moreover, there is no one-size-fits-all integrated care. This will be different for different mental health conditions (CMD vs. SMI) or substance use and will vary across cultures and contexts.[31] Decision makers and service providers must recognize the challenges and healthcare diversity. We must also allude to the time lags between treatment contacts, which might be attributed to the over-reliance on these specialized integrated services, which are few.

The fact that more than one in six persons in our study sample had physical health comorbidities and persons with DD are more likely to experience violence, self-harm, and other acute emergencies might explain the substantial general medical and emergency contacts.[34] Policymakers must recognize the importance of screening for mental health and substance misuse during these opportunistic encounters. Screening, brief interventions, and linkage with specialized DD services must be introduced to make these health encounters count and provide inclusive support bearing the “no wrong door” philosophy in mind.[35] A progressive increase in medical referrals in our study sample suggests that healthcare professionals recognize the need for linkage with higher and more intensive services.

India still has a traditional collectivistic society, and the family plays a key role as a decision-maker.[36] Therefore, it should not be surprising to see family members’ primary role in initiating healthcare contacts in our study population. Cross-national studies have shown that almost all patients with SMI in India live with their families.[37] The gradual increase in the rates of self-initiated treatment for subsequent contacts indicates that family members could act as a vehicle of change and support and motivate patients to see healthcare contacts. Therefore, the strength of the Indian family structure must be harnessed to reduce the treatment gap for patients with DD.

Persons with DD need access to crisis support, housing, aftercare, interventions to improve treatment retention and reduce substance misuse, and risk assessment and management. These psychosocial interventions may improve the outcome of patients with DD and are recommended as standards of care elsewhere.[38] However, delivering psychosocial interventions will require the availability of adequately trained staff. Limited access to psychosocial interventions in our study sample might reflect limited resources. However, the proportion of people receiving psychosocial interventions increased with further healthcare contacts. Higher contacts indicate a higher severity of DD and higher access to integrated DD care. Hence, these interventions are reserved for those with severe DD, permitting equitable distribution of the strained resources.

In our study, the likelihood of seeking integrated DD treatment had an erratic pattern. It increased significantly between the first and second contact, then plateaued to increase again at the last contact. This pattern reflects a dysfunctional referral and linkage in the healthcare system. The nonavailability of adequate human and other resources for primary and secondary care, a limited organizational mechanism to provide continuity of care, and the nonavailability of health cards are a few reasons for the ineffective healthcare referral system in the country.[39]

We observed similarities and differences compared to the pathways to care for those with SUDs. Like patients with alcohol dependence, those with DD were inclined to seek treatment from specialized treatment centers.[40] Moreover, similar to the treatment-seeking behavior for DD, the patterns of referral and subsequent contacts were also erratic for those with SUDs.[40,41] However, patients with SUDs, especially those with opioid dependence had a higher tendency to self-medicate, which is negligible in patients with DD.[27]

Finally, we observed that patients with CMD were more likely to seek SUD treatment, whereas those with SMI were “brought” for mental health symptoms. Interestingly, the providers’ treatment choices aligned with patients’ concerns, unlike the recommended standards of care. While the alignment might indicate patients’ preference and autonomy, treating one disorder will not change the course and outcome of the other disorder. Limited training and capability to screen and treat both conditions might have contributed to the under-treatment.[3] Insufficient treatment might also be explained by the service organization.[42] The negative attitude of the healthcare staff toward SUD treatment and a fear of “abuse” of SUD medications in patients with SMI could be other reasons for exclusion from either CMD or SUD treatment.[43] Delayed integrated care contact in those with CMD might be related to the initial contacts with general medical and private for-profit healthcare. One could attribute the limited awareness of public medical healthcare and financial motives in private care to the delayed time to access integrated care.

Limitation

Our study, conducted in eight centers in India, may only partially represent part of the country due to potential selection bias. Varying participant numbers across centers and a predominantly male sample limit generalizability. The cross-sectional design hinders establishing causation or assessing long-term trajectories. While integrated DD care within existing facilities seems practical, a dedicated DD team is needed. Operational aspects and healthcare providers’ challenges in delivering integrated care have yet to be extensively explored.

CONCLUSION

One in five patients with DD initially seek help from traditional/religious healers, transitioning to integrated care after that. Although family-initiated and supported treatment contacts were common, self-initiated and professional referrals increased over time. General medical and private for-profit healthcare systems are favored by patients with CMD, while private healthcare contributes 8%–12% of contacts. The study underscores the complexities of DD care in India, emphasizing the imperative for standardized, culturally sensitive approaches and collaborative care to effectively address challenges and bridge the treatment gap for those with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Center-wise distribution of dual-diagnosis patients

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the center staff who helped in the data collection and logistics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsuhaibani R, Smith DC, Lowrie R, Aljhani S, Paudyal V. Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:209. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obadeji A, Oluwole LO, Kumolalo BF, Dada MU. Patterns of substance use disorders and associated co-occurring psychiatric morbidity among patients seen at the psychiatric unit of a tertiary health center. Addict Health. 2022;14:35–43. doi: 10.22122/ahj.v14i1.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balhara YPS, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, Mahadevan J, Pal A, Narasimha VL, et al. Clinical care of patients with dual disorders in India: Diverse models of care delivery. Adv Dual Diagn. 2022;15:227–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh A, Sharma N, Noble D, Basu D, Mattoo SK, Bn S, et al. Predictors of five-year readmission to an inpatient service among patients with alcohol use disorders: Report from a low-middle income country. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57:123–33. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1990341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subodh BN, Hazari N, Elwadhi D, Basu D. Prevalence of dual diagnosis among clinic attending patients in a de-addiction centre of a tertiary care hospital. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balhara YPS, Prakash S, Gupta R. Pathways to care of alcohol -dependent patients: An exploratory study from a tertiary care substance use disorder treatment center. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2016;5:e30342. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.30342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S, Balhara YPS. A review of Indian research on co-occurring cannabis use disorders and psychiatric disorders. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:186–95. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_791_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basu D, Ghosh A. Profile of patients with dual diagnosis: Experience from an integrated dual diagnosis clinic in North India. J Alcohol Drug Depend. 2015;3:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Balhara YP. A Review of Indian research on co-occurring psychiatric disorders and alcohol use disorders. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:10–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.175089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todd J, Green G, Harrison M, Ikuesan BA, Self C, Pevalin DJ, et al. Social exclusion in clients with comorbid mental health and substance misuse problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:581–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt GE, Bergen J, Bashir M. Medication compliance and comorbid substance abuse in schizophrenia: Impact on community survival 4 years after a relapse. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:253–64. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziedonis DM, Smelson D, Rosenthal RN, Batki SL, Green AI, Henry RJ, et al. Improving the care of individuals with schizophrenia and substance use disorders: consensus recommendations. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:315–39. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szerman N, Torrens M, Maldonado R, Balhara YPS, Salom C, Maremmani I, et al. Addictive and other mental disorders: A call for a standardized definition of dual disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:446. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02212-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rollins AL, Eliacin J, Kukla M, Wasmuth S, Salyers MP, McGuire AB. Implementation of integrated dual disorder treatment in routine veterans health administration settings. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2022;22:112–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster G, Robertson J, Pallis S, Segal J. The dual diagnosis clinician shared care model – a clinical mental health dual diagnosis integrated treatment initiative. Adv Dual Diagn. 2022;15:165–76. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikkert M, Goudriaan A, de Waal M, Peen J, Dekker J. Effectiveness of Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT) in severe mental illness outpatients with a co-occurring substance use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;95:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fantuzzi C, Mezzina R. Dual diagnosis: A systematic review of the organization of community health services. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:300–10. doi: 10.1177/0020764019899975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. Bengaluru, Karnataka: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; 2016. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16: Mental Health Systems. NIMHANS Publication No. 130. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK, et al. New Delhi, India: Government of India; 2019. Magnitude of Substance Use in India, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huxley P, Krayer A, Poole R, Gromadzka A, Jie DL, Nafees S. The Goldberg-Huxley model of the pathway to psychiatric care: 21st-century systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2023;9:e114. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2023.505. doi: 10.1192/bjo. 2023.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogler LH, Cortes DE. Help-seeking pathways: A unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:554–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2011. Common Mental Health Disorders: Identification and Pathways to Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilford P, Wickramaseckara Rajapakshe OB, Singh SP. A systematic review of care pathways for psychosis in low-and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993. The ICD-10 classification of Mental and Behavioral disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gater R, de Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, Caraveo J, Chandrashekar CR, Dhadphale M, et al. The pathways to psychiatric care: A cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1991;21:761–74. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002239x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhad R, Gupta R, Balhara YPS. A study of pathways to care among opioid dependent individuals seeking treatment at a community de-addiction clinic in India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2020;19:490–502. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2018.1542528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh A, Mahintamani T, Somani A, Mukherjee D, Padhy S, Khanra S, et al. Exploring help-seeking pathways and disparities in substance use disorder care in India: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2024;66:528–37. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_123_24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijayakumar L. The need for mental health research in Southeast Asia. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023;13:100228. doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gureje O, Appiah-Poku J, Bello T, Kola L, Araya R, Chisholm D, et al. Effect of collaborative care between traditional and faith healers and primary health-care workers on psychosis outcomes in Nigeria and Ghana (COSIMPO): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:612–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocks S, Berntson D, Gil-Salmerón A, Kadu M, Ehrenberg N, Stein V, et al. Cost and effects of integrated care: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:1211–21. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chokron Garneau H, Assefa MT, Jo B, Ford JH, 2nd, Saldana L, McGovern MP. Sustainment of integrated care in addiction treatment settings: Primary outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73:280–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunette MF, Asher D, Whitley R, Lutz WJ, Wieder BL, Jones AM, et al. Implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: A qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:989–95. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yule AM, Kelly JF. Integrating treatment for co-occurring mental health conditions. Alcohol Res. 2019;40 doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.1.07. arcr.v40.1.07. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v40.1.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbosa C, McKnight-Eily LR, Grosse SD, Bray J. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in emergency departments: Review of the impact on healthcare costs and utilization. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;117:108096. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heitzman J, Worden RL editors, editors. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress; 1995. India: A Country Study. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dani MM, Thienhaus OJ. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia in two cities in the U.S. and India. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:300–1. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakobyan S, Vazirian S, Lee-Cheong S, Krausz M, Honer WG, Schutz CG. Concurrent disorder management guidelines. Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2406. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godlee F. Put patients first and give the money back. BMJ. 2015;351:h5489. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5489. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pal Singh Balhara Y, Prakash S, Gupta R. Pathways to care of alcohol -dependent patients: An exploratory study from a tertiary care substance use disorder treatment center. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. 2016;5:e30342. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.30342. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba. 30342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Somashekar VM, John S, Praharaj SK. Pathways to care in alcohol use disorders: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary hospital in South India. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2023:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2023.2189197. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2023.2189197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinderup P. Challenges in working with patients with dual diagnosis. Adv Dual Diagn. 2018;11:60–75. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilchrist G. Improving access, assessment and treatment response for substance abusers with co-occurring mental health problems. Adv Dual Diagn. 2012;5:1–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Center-wise distribution of dual-diagnosis patients