Abstract

During T-cell development in thymus, CD25, the IL-2 receptor α chain (IL-2Rα) is already expressed in early double-negative (DN) thymocytes where commitment to T-cell lineage has been established, but subsequently IL-2Rα is dramatically down-regulated for the remainder of T-cell development. The loss of IL-2Rα expression after expression of the pre-TCR α:β complex on the cell surface is essential for the later specific responses of mature T cells. Using appropriate mouse models and DMS genomic footprinting, we showed that the TATA box in the core promoter region of the murine IL-2Rα locus was occupied only in DN CD25+ T cells. Further, by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, we evidenced that down-regulation of IL-2Rα transcription correlated with (i) loss of the basal transcriptional machinery; (ii) dissociation of histone acetylase p300 and BRG1, a member of the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex SWI/SNF; and (iii) histone N-termini dephosphorylation plus deacetylation. In contrast, occupancy of the proximal enhancer region (positive regulatory region I) was not detected by in vivo genomic footprinting though constitutive accessibility of the promoter region for DNase I digestion both in the DN and double-positive stages correlated with the constitutive association of CBP and PCAF to the IL-2Rα core promoter. These results exemplify one mechanism by which a promoter enables transcription to switch on and off during T-cell differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) is the principal growth factor for antigen-activated T lymphocytes and it plays a pivotal role in peripheral tolerance through the elimination of self-reactive T cells by activation-induced cell death (1). IL-2 promotes T-cell proliferation by binding to a high affinity receptor composed of three transmembrane proteins, the α, β and γc chains (2). β and γc chains combine to form an intermediate-affinity receptor sufficient for IL-2 signaling (3,4) but cannot stimulate the proliferation of normal T lymphocytes (5–7). The main functions of the highly inducible α chain (CD25) are presumed to increase the affinity for IL-2, allowing responsiveness to the low levels of IL-2 physiologically produced in vivo. IL-2Rα is essential, as evidenced by autoimmunity in patients (8) and in mice lacking this protein (9). It was also suggested that the IL-2/IL-2R pathway is involved in thymic selection (10–12) though the phenotype of IL-2Rα-deficient mice seems to exclude a critical role for this component during ontogeny (9).

Developing thymocytes follow a strictly regulated differentiation program characterized through the expression of specific cell surface markers. The thymocyte precursors, which lack expression of both co-receptors CD4 and CD8 [CD4–CD8– double-negative (DN) cells], develop into an intermediate CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) stage before maturing into CD4+ or CD8+ single-positive (SP) cells and exiting the thymus. It is now well established that DN thymocytes represent an heterogeneous population that can be further subdivided into four consecutive developmental stages: DN CD44+CD25– (stage I), DN CD44+CD25+ (stage II), DN CD44–CD25+ (stage III) and DN CD44–CD25– (stage IV) (13–15). In mutant mice lacking the recombinase proteins RAG-1 or RAG-2, or in TCRβ- or pre-Tα-deficient mice, none of them form a pre-TCR complex, α/β T-cell development is significantly arrested at the DN stage III (16–19). Therefore, productive TCRβ chain rearrangement and assembly of the pre-TCR serves as the first checkpoint in T-lymphocyte development for stage III to stage IV transition. Signaling through pre-TCR mediates the transcriptional activation and repression of several genes, including IL-2Rα, and is critical for further proliferation and differentiation (20). After transition to the DP stage, thymocytes do not express IL-2Rα for the remainder of T-cell development. In resting mature lymphocytes its expression is physiologically triggered by antigen and co-stimulatory signals. In these cells, and more specifically in CD4+ T cells, human IL-2Rα is mainly regulated at the level of transcription by at least five positive regulatory regions (PRRI–PRRV) spread out over 12 kb. Each regulatory region appears to play a well defined and complementary role (21–27). For instance, PRRIII (–3786 to –3071) (28,29) and PRRV, located in the first exon (+3389 to +3596) (30), are two specific IL-2 responsive enhancers activated by inducible Stat5 proteins playing a crucial role in the IL-2/IL-2R autoregulatory loop which amplifies IL-2Rα transcription in the late stage of T-cell activation. Hence, IL-2Rα appears critically controlled by IL-2 contrary to the thymus where this cytokine is not directly involved in CD25/IL-2Rα transient expression during the transition from the DN stage to the DP stage. Thus, IL-2Rα appears to be independently regulated in primary and secondary lymphoid organs (31).

In contrast to the wealth of information on transcriptional regulation of IL-2Rα in mature lymphocytes, no attempt has been previously made to identify the molecular mechanisms controlling its expression during ontogeny. In order to differentiate the molecular mechanism enabling IL-2Rα transcription to switch on and off in thymus and in the periphery, we investigated in vivo during T-cell development the organization of the murine IL-2Rα promoter which presents 78% identity with the human gene (32). Using appropriate mouse models such as RAG-deficient mice whose thymic development is arrested at the CD25+ DN stage (17,18,33) that can be rescued to the CD25– DP stage by expression of a TCRβ transgene (34) or by anti-CD3 injection (35), we evidenced by in vivo footprinting that the occupation on TATA box (–33, –28) correlated with IL-2Rα gene expression in DN cells and with the binding of TATA binding protein (TBP) in vitro. As demonstrated in vivo by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP), repression of the IL-2Rα gene in DP cells was associated with the disengagement of two components of the general transcription machinery, TBP and Pol II as well as two members of the chromatin modifying complexes, the histone acetyl transferase (HAT) coactivator p300 and the DNA-dependent ATPase BRG1. In contrast, the HAT coactivators CBP and PCAF remained specifically associated to the inactive IL-2Rα promoter in DP cells. We also observed that acetylation and/or phosphorylation of histone H3 and H4 bound to IL-2Rα promoter was reverted during DN to DP transition. The implications of these observations are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

The mice used in this study included wild-type C57BL/6J and RAG-1-deficient (Rag–/–) (17,18,33). To rescue the development of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes, Rag–/– mice expressing a TCRβ transgene, P14 (Rag–/–, TCRβTg) (34) or 4-week-old Rag–/– mice injected intraperitoneally with anti-CD3ɛ monoclonal antibody (2C11; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) (Rag–/–CD3) (35) were alternatively used since they present an identical CD25– DN phenotype. Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free breeding facility and killed for analysis at between 4 and 6 weeks of age.

DNase I hypersensitivity assay

Isolation and DNase I digestion of nuclei and purification of genomic DNA were performed as described (36). Briefly, nuclei were isolated from 1 × 108 cells by lysis in 0.05% NP-40, suspended at a concentration of 2 × 107 and 5 × 107 nuclei per ml. Aliquots of nuclei were incubated for 3 min at room temperature. The amounts of DNase I (Amersham Life Science) used are indicated in the legend to Figure 1. DNA was purified by phenol–chloroform extraction and 15 µg of DNA was digested with EcoRI. Samples were resolved on a 1% agarose gel, and analyzed by Southern blot assay using a mouse IL-2Rα gene locus-specific probe (see Fig. 1A) which was amplified by PCR (primer mCD25-1, 5′-CCCAGGAAGATGCAGTAAAGGGGTTGACCC-3′, and primer mCD25-2, 5′-CTTCCAAGACAGCAAAGCCAAACCATCCCTGG-3′).

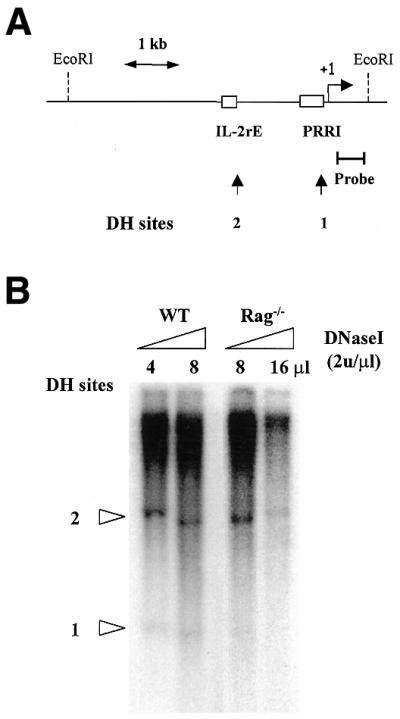

Figure 1.

Analysis of the promoter of the mouse IL-2Rα gene during T-cell development by DNase hypersensitivity assay. (A) Schematic representation of the mouse IL-2Rα gene promoter showing the location of DNase I hypersensitivity sites. The bracketed bar represents the probe. The broken arrow indicates the transcriptional start site (+1) and the open boxes represent, respectively, the location of the proximal regulatory region I and the IL-2 responsive enhancer. Arrows mark the positions of the DH sites (B) DNase I hypersensitivity pattern on the mouse IL-2Rα locus in the WT mice. Highly purified mouse thymocytes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The EcoRI-digested genomic DNA was analyzed by Southern blot using the locus-specific 0.44-kb probe. The amounts of DNase I used for WT were 8 and 16 U and for Rag–/–, 16 and 32 U.

In vivo genomic footprinting assay

Genomic footprinting analyses were performed by the DMS/LM–PCR method as previously described (22) using in vitro and in vivo methylated genomic DNA purified from Rag–/–, Rag–/– TCRβTg and C57BL/6J wild-type thymocytes. The following oligonucleotide primers were used for the coding strand: primer 1, 5′-ATGGGATCAGGATGGAGGA-3′ [(+136, +118), Tm 60°C]; primer 2, 5′-CTCTGCAGTATATTGGGTCAACCCC-3′ [(+100, +76), Tm 63°C]; primer 3, 5′-GGGTCAACCCCTTTACTGCATCTTCCTGGG-3′ [(+86, +57), Tm 68°C].

In vitro DNase I footprinting assay

A radiolabeled 184-bp DNA probe was prepared by PCR amplification from WT genomic DNA using the primers shown in Figure 2B. The DNase I footprinting assays were performed in a final volume of 20 µl, with reaction mixtures containing 6 × 105 c.p.m. of the one-end radiolabeled fragments, 10 µl of 2× TBP binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 4 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 8 mM spermidine, 35% glycerol, 200 µg/ml BSA), 0.5 µl of poly(dI·dC) (1 µg/µl), 0.25 µl of 1% NP-40, 2 µl of 25 mM CaCl2, and TG10EDK50 (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 mM KCl) to the final volume. The amount of protein used in different reactions was 1 µl of human TBP (500 ng/µl). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 30 min. Digestion reactions were performed with 1 µl of DNase I (0.1 U/µl) for 60 s, and were stopped by 400 µl of stop solution (0.5% SDS, 50 mM sodium acetate, 50 µg of tRNA). Twice phenol–chloroform-extracted and ethanol-precipitated DNA pellets were resolved on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

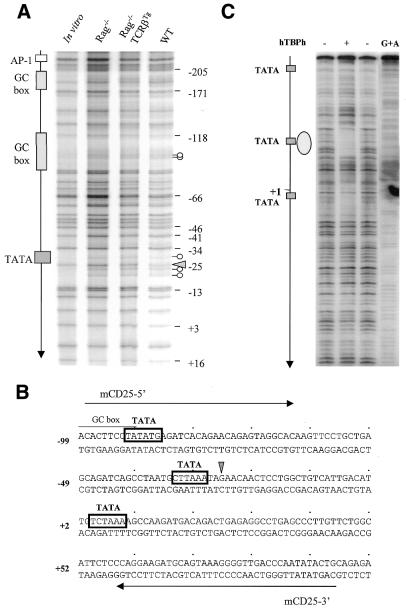

Figure 2.

Identification of the core promoter element, TATA box, in the mouse IL-2Rα locus by in vivo and in vitro footprinting assays. (A) In vivo footprinting analysis of the proximal promoter region of the mouse IL-2Rα gene. DMS/LM–PCR was performed with in vitro or in vivo methylated DNA from thymocytes of Rag–/–, Rag–/– TCRβTg and WT mice. Localization of the putative regulatory elements within the proximal regulatory region of the IL-2Rα gene is indicated on the right side. The arrow marks the in vivo footprinting and the circular marks the enhanced methylation of adenine bases in living cells compared with naked DNA. (B) Partial DNA sequence of the mouse IL-2Rα promoter region. The radiolabeled 184-bp DNA fragment was prepared by PCR amplification with the primers mCD25-5′ and mCD25-3′. Open frames show the positions of three putative TATA boxes. The arrow indicates the guanine residue –25 evidenced by in vivo footprinting. (C) In vitro DNase I footprinting was performed using highly purified recombinant human TBP (hTBP) as indicated above the panel. The G+A sequence ladder is shown on the right lane and the position of the three TATA on the left side.

ChIP assay

Chromatin from Rag–/–, Rag–/–TgP14 and B6 wild-type thymocytes was fixed and immunoprecipitated using the ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology) as recommended by the manufacturer. The purified chromatin was immunoprecipitated using 10 µg of anti-phosphorylated-H3 (p-H3), acetylated-H3 (Ac-H3) or acetylated-H4 (Ac-H4) (UBI), 10 µg of anti-TBP, Pol II, CBP, p300, BRG-1 or PCAF (Santa Cruz), or 5 µl of rabbit non-immune serum. The input fraction corresponded to 0.1 and 0.05% of the chromatin solution before immunoprecipitation. Following DNA purification, the presence of selected DNA sequences was assessed by PCR. Fourteen cycles were performed with the first primer set in 50 µl with 2 and 4% of immunoprecipitated material. Then, using 2 µl of the first PCR product, 25 additional cycles of PCR were performed with the mCD25-3′-2 primer set and 1 µCi of [α-32P]dCTP. PCR products were resolved in 8% acrylamide gels. A 2-fold dilution series was typically used for first PCR reaction. The primers used were as follows: mCD25-5′, 5′-CACTTCCTATATGAGATCACAGAACAGAG-3′; mCD25-3′-1, 5′-CTCTGCAGTATATTGGGTCAACCCC-3′ (first PCR, 198 bp product) or mCD25-3′-2, 5′-GGGTCAACCCCTTTACTGCATCTTCCTGGG-3′ (second PCR, 184 bp product). For CD3ɛ, the primers were 5′-CCCCCACTCTCCTTCATCCT-3′ and 5′-TGTTCCACCGCATCCTCTCA-3′. The PCR program and primer sequences used for Oct-2 and MyoD gene analysis were as previously described (37,38). The average size of the sonicated DNA fragments subjected to immunoprccipitation was 500 bp as controlled by ethidium bromide gel electrophoresis.

RESULTS

PRRI is constitutively accessible for DNase I digestion during ontogeny

In order to determine whether loss of IL-2Rα expression during stage III to stage IV transition during thymocyte differentiation corresponds to changes in chromatin structure accessibility, DNase I hypersensitivity assays were performed using either wild-type thymocytes as a source of CD25 negative cells or CD25+ DN thymocytes of mice deficient for the recombination activating gene RAG-1. Indeed, wild-type thymocytes comprised mostly CD25– DP and SP cells (95% of thymus content) whereas thymocyte development is completely arrested at the CD44–CD25+ stage in Rag–/– mice. We used an EcoRI 5.2-kb segment extending from 4.6 kb 5′ to 0.6 kb 3′ of the major transcription start site (32) (Fig. 1A). Hybridization of Southern blots of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA with the 0.44-kb probe covering nucleotides (+56 to +496) revealed two DNase I hypersensitive (DH) sites (Fig. 1B). DH1 maps a region between the proximal enhancer PRRI and +1 and DH2 is located –1.35 kb, corresponding to two previously reported DH sites (39). Both sites appeared accessible to DNase I digestion in Rag–/– and WT T cells from thymus although the DH1 band was weaker in Rag–/– thymocytes suggesting that no major change in chromatin accessibility correlates with IL-2Rα down-modulation during T-cell development in thymus.

Characterization of the core promoter element in the mouse IL-2Rα locus

DNase I hypersensitivity assays can only reveal major changes in the chromatin structure at a given locus. In an attempt to characterize more subtle modifications, in vivo DMS footprintings were performed to analyze the promoter region of IL-2Rα locus in CD25+ and CD25– thymocytes using Rag–/– and WT mice, respectively. To determine the involvement of a functional pre-TCR, we also used thymocytes from Rag–/– mice expressing a TCRβ transgene where the expression of TCRβ chain restores the pre-TCR signaling and allows the differentiation of DN CD25+ cells into DP CD25– thymocytes (34). The mouse IL-2Rα promoter region, localized between nucleotides –400 and +20 relative to the major transcription initiation site, contains four TATA boxes, two GC boxes, two NF-κB and four AP-1 binding sites (32). No significant footprint was found on GC boxes, NF-κB and AP-1 binding sites in the Rag–/–, Rag–/– TCRβTg and WT thymocytes (Fig. 2A and data not shown). This absence of footprint was not apparently due to an heterogeneity of the thymocyte population analyzed since >95% are DN CD25+ in Rag–/– mice. We can also exclude a problem linked to DNA quality since the same batches were successfully used to characterize the occupancy of the TCRα enhancer during T-cell development (40). However, enhanced methylation of adenine bases was observed at different positions in comparison with naked DNA but without correlation with IL-2Rα expression status. Such enhanced adenine methylation in living cells has already been reported and is probably due to a difference in the buffer composition between naked DNA and nuclear extract samples (41). In contrast, an increased methylation on guanine –25 just downstream of TATA box (–33, –28) in the coding strand was reproducibly observed in Rag–/– thymocytes; however, this footprint was not observed in the non-coding strand (data not shown). This observation suggested the occupancy of TATA box (+33, –28) by TBP, its cognate DNA binding protein, was restricted to CD25+ DN thymocytes. Furthermore, no significant footprint (data not shown) was observed on identified regulatory elements within the murine PRRIII/IL-2rE (32) despite the presence of a strong constitutive DH site.

Determination of the functional TATA box

To lend further support for a specific binding of TBP to TATA box (–33, –28), we examined the binding efficiency of this TATA box to recombinant TBP by in vitro DNase I footprinting assay. An IL-2Rα promoter probe was prepared by PCR using 32P-labeled mCD25-3′ primer (Fig. 2B). Highly purified recombinant human TBP efficiently bound to the TATA box (–33, –28) as shown in Figure 2C. In contrast, only weak protections were observed on TATA boxes (–92, –87) and (+2, +7). The most dramatic protection by TBP on TATA box (–33, –28) correlated with increased methylation of guanine –25 in CD25+ thymocytes. Collectively, the results from in vivo and in vitro footprintings are in agreement with TBP binding to TATA box (–33, –28) of the mouse IL-2Rα locus at the DN stage.

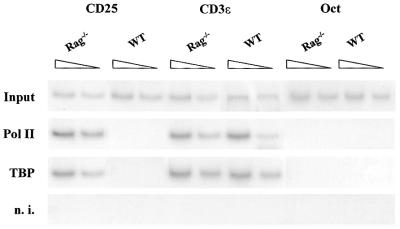

Recruitment of basal transcription machinery to IL-2Rα promoter in vivo

Our observations suggested that TBP is recruited to the IL-2Rα promoter in DN but not DP thymocytes. To address this point, we carried out ChIP experiments that can establish whether a known transcription factor truly binds in the vicinity of a known regulatory element in living cells. Purified CD25+ thymocytes from Rag–/– mice or CD25– thymocytes from WT mice were treated with formaldehyde to cross-link protein–protein and protein–DNA complexes. Following precipitation by specific antibodies against Pol II and TBP, the IL-2Rα promoter fragment present in the immunoprecipitates was identified by PCR amplification. CD3ɛ and Oct-2 were used as active and inactive promoter controls, respectively. In vivo association of TBP and Pol II to IL-2Rα promoter was only found in Rag–/– thymocytes (Fig. 3). TBP and Pol II were permanently associated with the CD3ɛ promoter constitutively active at the DN and DP stages. In contrast, neither TBP nor Pol II fixation was found in the inactive Oct-2 promoter. Comparison of the recruitment of TBP and Pol II with the IL-2Rα promoter in the DN and DP stages evidenced that repression of IL-2Rα expression at the DP stage correlates with dissociation of TBP and RNA Pol II holoenzyme in DP thymocytes.

Figure 3.

Recruitment of basal transcription factors, Pol II and TBP, to IL-2Rα promoter in vivo. PCR analysis of chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA from Rag–/– and WT thymocytes with specific primers for the mouse IL-2Rα core promoter. The input fraction corresponded to 0.1 and 0.05% of the chromatin solution before immunoprecipitation. DNA–protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with rabbit non-immune serum (n.i.) or specific Pol II, TBP antibodies. CD3ɛ and Oct-2 promoter regions were also analyzed as positive and negative controls, respectively.

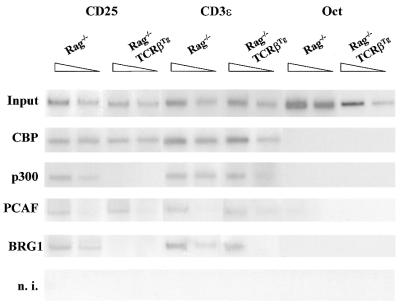

Recruitment of histone acetyl transferases and ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complex to the IL-2Rα core promoter region in vivo

Besides the interactions of basal transcription machinery and site-specific activators, it has become widely accepted that modification of chromatin structure is an important regulatory mechanism. Nucleosome assembly appears to eliminate the ability of the general transcription factors such as TFIID and the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme to interact with promoter sequences. Thus, efficient transcription initiation by the basal transcription machinery requires the recruitment of components of the chromatin remodeling complexes (42). Chromatin modifying activities involve two general classes of protein complexes which differ in whether or not they use covalent modification to alter chromatin structure (43). The first class consists of the HATs and histone deacetylases which respectively modify covalently the N-terminal tails of nucleosomal histones (44). The mammalian GCN5/PCAF and the CBP/p300 proteins bear HAT activities and function as coactivators of transcription by the recruitment to promoters via their interaction with various DNA binding proteins. The second class consists of the ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes which facilitate the accessibility to DNA, altering chromatin structure by changing the location or conformation of the nucleosome (45). Among them, the multi-subunit complex SWI/SNF contains eight or more polypeptides in which the DNA-dependent ATPase is either the BRG1 or BRM1 protein.

Since Pol II and TBP were bound to the IL-2Rα core promoter at the activated stage, we investigated the in vivo recruitment of CBP, p300 and GCN5/PCAF as well as of BRG1. Surprisingly, we found CBP and PCAF constitutively associated to the IL-2Rα promoter both in the activated and suppressive stages whereas p300 and BRG1 were only recruited in CD25+ thymocytes from Rag–/– mice (Fig. 4). The constitutive binding of CBP and PCAF correlated with the DNA accessibility to DNase I digestion both in the DN and DP stages whereas the dissociation of p300 and BRG1 correlated with the disengagement of the basal transcription machinery and IL-2Rα down-regulation in Rag–/–, TCRβTg mice.

Figure 4.

Recruitment of HATs CBP, p300 and GCN5/PCAF, and the chromatin-remodeling complex, BRG1, to IL-2Rα promoter in vivo. Chromatin from Rag–/– and Rag–/–TgP14 thymocytes was analyzed by specific PCR assay for the mouse IL-2Rα/PRRI. The input fraction is the same as in Figure 4. DNA–protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with rabbit non-immune serum (n.i.) or specific CBP, p300, PCAF or BRG1 antibodies. The ChIP assay controls included the CD3ɛ and Oct-2 promoter regions.

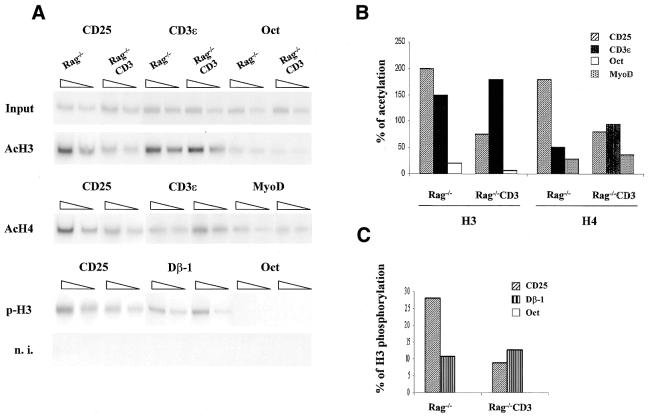

Histone acetylation and phosphorylation correlates with the transcriptional regulation of the mouse CD25/IL-2Rα promoter

N-terminal tail modifications of nucleosomal histones play a central role in transcription regulation allowing for dynamic changes in the accessibility of the underlying genome (46). According to the recruitment of CBP, PCAF and p300 to IL-2Rα promoter, the status of the histone proteins bound to this region was investigated by ChIP assay performed with anti-AcH3, anti-AcH4 and anti-pH3 antibodies. Figure 5A and C shows that H3 and H4 bound to IL-2Rα promoter were highly acetylated at DN stage. In contrast, H3 and H4 acetylation levels were dramatically reduced in CD25– thymocytes from Rag–/–, CD3-treated mice whereas both histones associated with the constitutively active CD3ɛ promoter were highly acetylated at both the DN and DP stages. As a negative control, H3 associated with the silent Oct-2 promoter was very weakly acetylated. Surprisingly, H4 bound to this inactive promoter was acetylated at both the DN and DP stages during T-cell development (data not shown). To exclude a lack of specificity of acetylated H4 binding, we used the inactive MyoD promoter as a negative control (37). H3 bound to the IL-2Rα promoter was also phosphorylated in CD25+ but much less in CD25– thymocytes. As expected, phosphorylated H3 bound to the active Dβ-1 promoter in CD25+ and CD25– thymocytes (Spicuglia,S. and Ferrier,P., unpublished results). These observations evidenced that acetylation of H3 and H4, and phosphorylation of H3 associated with the IL-2Rα promoter region, were strongly reduced when the gene was repressed during the DN to DP transition. Hence, chromatin modification in the vicinity of the core promoter region corresponds to the expression pattern of the IL-2Rα gene during T-cell development in thymus.

Figure 5.

Modifications of the histone proteins correlate with the expression pattern of IL-2Rα. (A) PCR analysis of chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA from Rag–/–, and Rag–/–CD3 thymocytes for the mouse IL-2Rα promoter. DNA–protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with rabbit non-immune serum (n.i.) or specific Ac-H3, Ac-H4 or p-H3 antibodies. CD3ɛ and Dβ-1 were the activ gene controls and Oct-2 and MyoD promoter regions the inactive gene controls. (B and C) Densitometric quantification relative to the input fraction of the level of histone acetylation and of H3 phosphorylation, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have investigated the identity of proteins associated with IL-2Rα promoter accessibility during T-cell development. Our studies have revealed that TATA box (–33, –28) in the IL-2Rα core promoter is specifically occupied in the DN thymocytes from Rag–/– mice. IL-2Rα expression at the CD25+ DN stage correlated with the specific recruitment of the basal transcription machinery components TBP and Pol II as well as the HAT coactivators CPB, p300 and PCAF, and the DNA-dependent ATPase BRG1, a component of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. After undergoing selection for productive TCRβ chain rearrangements and pre-TCR signaling, developing thymocytes proceed to the proliferation stage and dramatically down-regulate CD25/IL-2Rα expression very rapidly. Down-regulation of IL-2Rα transcription after pre-TCR signal correlates with (i) loss of the basal transcriptional machinery, (ii) disassociation of chromatin remodeling complexes and (iii) histone N-termini dephosphorylation and deacetylation on the core promoter region. However, the silenced IL-2Rα gene still maintains the accessibility to its proximal promoter/enhancer region. This accessibility correlates with constitutive binding of PCAF and CBP and may enable rapid re-activation of IL-2Rα in response to T-cell activation signals.

Modification of histone tails appears to act in concert as ‘signaling platforms’, providing a molecular code for the specific recruitment of transcription factors and coactivators to core promoter (reviewed in 46). For example, the acetylated histone N-termini interact with HAT and TAFII250 bromodomains (47,48) but also most probably with the bromodomain of BRG1/BRM proteins present in the SWI/SNF complex. BRG1 recruitment in DN thymocytes is in agreement with a role in chromatin remodeling for the SWI/SNF complex that allows association of TBP and Pol II holoenzyme, completion of PIC assembly at IL-2Rα core promoter and initiation of transcription. The engagement of CBP, p300 and PCAF, which possess intrinsic HAT activity, raises the question of functional redundancy. The dissociation of p300 after the DN to DP transition and the maintenance of CBP and PCAF suggest that each cofactor exerts a distinct and non-redundant role in IL-2Rα gene regulation. Several lines of evidence indeed point to functional differences between these three cofactors (reviewed in 49). p300 engagement correlated with the level of H3 and H4 acetylation and with TBP, Pol II and BRG1 recruitment to the active IL-2Rα promoter. In contrast, CBP and PCAF constitutive binding and the presence of a constitutive DH site appear to participate in the maintenance of a pre-assembled nucleo-protein complex at the IL-2Rα promoter in order to allow a rapid response to the incoming stimuli characteristic of mature T-cell activation. Accordingly, maintenance of activator proteins at specific promoters in yeast has already been reported despite their silencing (50).

We have previously reported a correlation between pre-commitment to activation and detection of stable occupancy by in vivo footprinting within IL-2Rα PRRI enhancer in human mature T cells (22). Such T-cell-specific footprints were not observed in the murine DN, DP and WT thymocytes analyzed in the present study, suggesting that transcriptional activation of IL-2Rα in DN thymocytes and its down-modulation in DP thymocytes depend on different molecular mechanisms than those involved in mature peripheral blood T cells While further comparative analysis is required to identify the common and divergent peculiarities of Il-2Rα gene regulation in thymocytes and mature T cells, our results are in agreement with a previous report evidencing an independent regulation of IL-2Rα expression in primary and secondary lymphoid organs (31). Among the common features, the same TATA box seems to be used in thymocytes and peripheral T cells, whereas the promoter region contains four putative TATA boxes (51). The location of the two constitutive DH sites observed in thymocytes appear also identical to two previously reported DH sites in immature T cells (39). However, the distal site apparently corresponding to the so-called PRRIII/IL-2rE was apparently inducible upon IL-2 stimulation in mature T cells whereas IL-2Rα expression is independent of IL-2 during the early stage of ontogeny. Furthermore, we failed to detect any significant modification of the two NF-κB-binding sites within murine IL-2Rα/PRRI suggesting that transcriptional activation of the IL-2Rα gene at the DN stage in thymus may be NF-κB-independent while activation of NF-κB has been associated with IL-2Rα gene expression in mature T cells (22,23,52–54). Furthermore, none of the other identified regulatory elements within murine IL-2Rα/PRRI and PRRIII (data not shown) were found occupied by in vivo footprinting. However, HAT and SWI/SNF complexes lack sequence-specific DNA binding, and are therefore thought to be recruited to specific promoters via interactions with specific DNA binding proteins. The site-specific transcriptional activators required for IL-2Rα gene activation at the DN stage in thymus remain to be identified.

Whereas both the mature TCR and the pre-TCR can trigger anti-apoptotic events and proliferative signals, the pre-TCR triggers several additional outcomes, including termination of TCRβ locus rearrangements and induction of CD4 and CD8 expression (reviewed in 55,56). The pre-TCR-driven transition from the DN to DP compartment characterized by CD25 transient expression appears as a multi-branched program, involving distinct transduction pathways which can either activate gene expression such as TCRα, CD4 and CD8 or repress other genes such as RAG, germline Vβ, preTα and IL-2Rα (20). In agreement with a direct role of pre-TCR signaling in its repression, IL-2Rα expression persisted to the DP stage in thymocytes expressing specifically β-catenin in the absence of pre-TCR signaling in RAG-2–/– mice (57). Because of the crucial role of the IL-2/IL-2R system in the regulation of the magnitude and duration of T-cell immune response, inactivation of the IL-2Rα gene by pre-TCR signal in thymus is required to ensure the specificity of T-cell responses in the periphery. Indeed, most of the biologic effects of IL-2 are mediated through its high affinity receptor as evidenced by the almost identical phenotype of mice with targeted inactivation of the genes for IL-2 (58) and IL-2Rα (9). Beside its controversial role in thymocyte maturation, IL-2Rα provides a convenient model for the characterization of the molecular mechanisms involved in transcription repression by pre-TCR signaling. The absence of significant DMS footprinting on the known transcriptional regulatory elements within murine IL-2Rα PRRI suggests that transcription factors different from those involved in mature T lymphocytes ensure IL-2Rα activation and repression during thymocyte differentiation.

Gene-targeting studies have demonstrated the crucial role as a transcriptional repressor played by Ikaros in regulating multiple stages of B- and T-cell development (reviewed in 59,60). A putative target sequence has been identified overlapping the PRRI NF-κB binding site conserved in human and mouse IL-2Rα genes (32,61). However, we failed to observe any significant occupancy within this region and several lines of evidence seem to exclude a role for Ikaros in IL-2Rα repression during ontogeny and in mature T cells (62). Alternatively, activation or repression of genes may be regulated by activators or repressors which recognize the chromatin structure, such as SATB1 which appears to orchestrate the temporal and spatial expression of genes during T-cell development (63). In SATB1-null mice, IL-2Rα is ectopically transcribed in DP thymocytes strongly suggesting that SATB1 acts as a repressor during ontogeny. However, no functional SATB1-binding site has been identified so far in the regulatory regions of the murine IL-2Rα. Further work is required to clarify these issues.

In summary, we evidenced for the first time that IL-2Rα repression during thymocyte differentiation is characterized by major reorganization of the transcription machinery and chromatin modifications associated with the IL-2Rα promoter in response to pre-TCR signaling. Furthermore, our studies provide another example that the particular order by which the chromatin-modifying activities are recruited and/or function to allow gene activation might be gene specific (64).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jean-Marc Egly for his invaluable help in the purification of the recombinant protein hTBP, Dominique Payet and Terumi Kowhi-Shigematsu for helpful discussion, and Brigitte Kahn-Perles for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by institutional grants from INSERM and CNRS, and by a specific grant from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer Recherche Médicale. J.-H.Y. was supported by a fellowship from French government (BGF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin J.X. and Leonard,W.J. (1997) Signaling from the IL-2 receptor to the nucleus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev., 8, 313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minami Y., Kono,T., Miyazaki,T. and Taniguchi,T. (1993) The IL-2 receptor complex: its structure, function and target genes. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 11, 245–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura Y., Russell,S.M., Mess,S.A., Friedmann,M., Erdos,M., Francois,C., Jacques,Y., Adelstein,S. and Leonard,W.J. (1994) Heterodimerization of the IL-2 receptor beta- and gamma-chain cytoplasmic domains is required for signalling. Nature, 369, 330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson B.H., Lord,J.D. and Greenberg,P.D. (1994) Cytoplasmic domains of the interleukin-2 receptor beta and gamma chains mediate the signal for T-cell proliferation. Nature, 369, 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantrell D.A. and Smith,K.A. (1984) The interleukin-2 T-cell system: a new cell growth model. Science, 224, 1312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenthal J.W., Tougne,C., MacDonald,H.R., Smith,K.A. and Nabholz,M. (1985) Antigenic stimulation regulates the expression of IL 2 receptors in a cytolytic T lymphocyte clone. J. Immunol., 134, 931–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soldaini E., MacDonald,H.R. and Nabholz,M. (1992) Minimal growth requirements of mature T lymphocytes: interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 increase growth rate but not plating efficiency of CD4 cells stimulated with anti-CD3 and IL-2. Eur. J. Immunol., 22, 1707–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharfe N., Dadi,H.K., Shahar,M. and Roifman,C.M. (1997) Human immune disorder arising from mutation of the alpha chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 3168–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willerford D.M., Chen,J., Ferry,J.A., Davidson,L., Ma,A. and Alt,F.W. (1995) Interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain regulates the size and content of the peripheral lymphoid compartment. Immunity, 3, 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tentori L., Longo,D.L., Zuniga-Pflucker,J.C., Wing,C. and Kruisbeek,A.M. (1988) Essential role of the interleukin 2-interleukin 2 receptor pathway in thymocyte maturation in vivo. J. Exp. Med., 168, 1741–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuniga-Pflucker J.C. and Kruisbeek,A.M. (1990) Intrathymic radioresistant stem cells follow an IL-2/IL-2R pathway during thymic regeneration after sublethal irradiation. J. Immunol., 144, 3736–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassiri H. and Carding,S.R. (2001) A requirement for il-2/il-2 receptor signaling in intrathymic negative selection. J. Immunol., 166, 5945–5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman E.S., Passoni,L., Crompton,T., Leu,T.M., Schatz,D.G., Koff,A., Owen,M.J. and Hayday,A.C. (1996) Productive T-cell receptor beta-chain gene rearrangement: coincident regulation of cell cycle and clonality during development in vivo. Genes Dev., 10, 948–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey D.I., Kennedy,J., Suda,T. and Zlotnik,A. (1993) A developmental pathway involving four phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of CD3-CD4-CD8- triple-negative adult mouse thymocytes defined by CD44 and CD25 expression. J. Immunol., 150, 4244–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voll R.E., Jimi,E., Phillips,R.J., Barber,D.F., Rincon,M., Hayday,A.C., Flavell,R.A. and Ghosh,S. (2000) NF-kappa B activation by the pre-T cell receptor serves as a selective survival signal in T lymphocyte development. Immunity, 13, 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehling H.J., Krotkova,A., Saint-Ruf,C. and Von Boehmer,H. (1995) Crucial role of the pre-T-cell receptor alpha gene in development of alpha beta but not gamma delta T cells. Nature, 375, 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mombaerts P., Clarke,A.R., Rudnicki,M.A., Lacomini,J., Itohara,S., Lafaye,J.J., Wang,L., Ichikawa,Y., Jaenisch,R., Hooper,M.L. and Tonegawa,S. (1992) Mutation in T-cell antigen receptor gene alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature, 360, 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mombaerts P., Iacomini,J., Johnson,R.S., Herrup,K., Tonegawa,S. and Papaioannou,V.E. (1992) RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell, 68, 869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinkai Y., Rathbun,G., Lam,K.P., Oltz,E.M., Stewart,V., Mendelsohn,M., Charron,J., Datta,M., Young,F. and Stall,A.M. (1992) RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell, 68, 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malissen B., Ardouin,L., Lin,S.Y., Gillet,A. and Malissen,M. (1999) Function of the CD3 subunits of the pre-TCR and TCR complexes during T cell development. Adv. Immunol., 72, 103–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cross S.L., Feinberg,M., Wolf,J.B., Holbrook,N.J., Wong-Staal,F. and Leonard,W.J. (1987) Regulation of the human interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain promoter: activation of a nonfunctional promoter by the transactivator gene of HTLV-I. Cell, 49, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Algarte M., Lecine,P., Costello,R., Plet,A., Olive,D. and Imbert,J. (1995) In vivo regulation of interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene transcription by the coordinated binding of constitutive and inducible factors in human primary T-cells. EMBO J., 14, 5060–5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuang A.A., Novak,K.D., Kang,S.M., Bruhn,K. and Lenardo,M.J. (1993) Interaction between NF-kappa B and serum response factor-binding elements activates an interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain enhancer specifically in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 2536–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin B.B., Cross,S.L., Halden,N.F., Roman,D.G., Toledano,M.B. and Leonard,W.J. (1990) Delineation of an enhancer like positive regulatory element in the interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 850–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce J.W., Jamieson,C.A., Ross,J.L. and Sen,R. (1995) Activation of IL-2 receptor alpha-chain gene by individual members of the rel oncogene family in association with serum response factor. J. Immunol., 155, 1972–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John S., Reeves,R.B., Lin,J.X., Child,R., Leiden,J.M., Thompson,C.B. and Leonard,W.J. (1995) Regulation of cell-type-specific interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain gene expression: potential role of physical interactions between Elf-1, HMG-I(Y) and NF-kappa B family proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 1786–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh J.H., Lecine,P., Nunes,J.A., Spicuglia,S., Ferrier,P., Olive,D. and Imbert,J. (2001) Novel CD28-responsive enhancer activated by CREB/ATF and AP-1 families in the human interleukin-2 receptor α-chain locus. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 4515–4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.John S., Robbins,C.M. and Leonard,W.J. (1996) An IL-2 response element in the human IL-2 receptor alpha chain promoter is a composite element that binds Stat5, Elf-1, HMG-I(Y) and a GATA family protein. EMBO J., 15, 5627–5635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecine P., Algarte,M., Rameil,P., Beadling,C., Bucher,P., Nabholz,M. and Imbert,J. (1996) Elf-1 and Stat5 bind to a critical element in a new enhancer of the human interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 6829–6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H.P., Kelly,J. and Leonard,W.J. (2001) The basis for IL-2-induced IL-2 receptor alpha chain gene regulation: importance of two widely separated IL-2 response elements. Immunity, 15, 159–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demaison C., Fiette,L., Blanchetiere,V., Schimpl,A., Theze,J. and Froussard,P. (1998) IL-2 receptor alpha-chain expression is independently regulated in primary and secondary lymphoid organs. J. Immunol., 161, 1977–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperisen P., Wang,S.M., Soldaini,E., Pla,M., Rusterholz,C., Bucher,P., Corthesy,P., Reichenbach,P. and Nabholz,M. (1995) Mouse interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene expression—interleukin-1 and interleukin-2 control transcription via distinct cis-acting elements. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 10743–10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spanopoulou E. (1996) Cellular and molecular analysis of lymphoid development using Rag-deficient mice. Int. Rev. Immunol., 13, 257–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pircher H., Burki,K., Lang,R., Hengartner,H. and Zinkernagel,R.M. (1989) Tolerance induction in double specific T-cell receptor transgenic mice varies with antigen. Nature, 342, 559–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinkai Y. and Alt,F.W. (1994) CD3 epsilon-mediated signals rescue the development of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes in RAG-2–/– mice in the absence of TCR beta chain expression. Int. Immunol., 6, 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cockerill P.N., Shannon,M.F., Bert,A.G., Ryan,G.R. and Vadas,M.A. (1993) The granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor/interleukin 3 locus is regulated by an inducible cyclosporin A-sensitive enhancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 2466–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agata Y., Katakai,T., Ye,S.K., Sugai,M., Gonda,H., Honjo,T., Ikuta,K. and Shimizu,A. (2001) Histone acetylation determines the developmentally regulated accessibility for T cell receptor gamma gene recombination. J. Exp. Med., 193, 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMurry M.T. and Krangel,M.S. (2000) A role for histone acetylation in the developmental regulation of VDJ recombination. Science, 287, 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soldaini E., Pla,M., Beermann,F., Espel,E., Corthesy,P., Barange,S., Waanders,G.A., MacDonald,H.R. and Nabholz,M. (1995) Mouse interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene expression. Delimitation of cis-acting regulatory elements in transgenic mice and by mapping of DNAse-I hypersensitive sites. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 10733–10742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spicuglia S., Payet,D., Tripathi,R.K., Rameil,P., Verthuy,C., Imbert,J., Ferrier,P. and Hempel,W.M. (2000) TCRalpha enhancer activation occurs via a conformational change of a pre-assembled nucleo-protein complex. EMBO J., 19, 2034–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grange T., Bertrand,E., Espinas,M.L., Fromont-Racine,M., Rigaud,G., Roux,J. and Pictet,R. (1997) In vivo footprinting of the interaction of proteins with DNA and RNA. Methods, 11, 151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fry C.J. and Peterson,C.L. (2001) Chromatin remodeling enzymes: who’s on first? Curr. Biol., 11, R185–R197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kingston R.E. and Narlikar,G.J. (1999) ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev., 13, 2339–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strahl B.D. and Allis,C.D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature, 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vignali M., Hassan,A.H., Neely,K.E. and Workman,J.L. (2000) ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung P., Allis,C.D. and Sassone-Corsi,P. (2000) Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell, 103, 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dhalluin C., Carlson,J.E., Zeng,L., He,C., Aggarwal,A.K. and Zhou,M.M. (1999) Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature, 399, 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobson R.H., Ladurner,A.G., King,D.S. and Tjian,R. (2000) Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science, 288, 1422–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glass C.K. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (2000) The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev., 14, 121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sekinger E.A. and Gross,D.S. (2001) Silenced chromatin is permissive to activator binding and PIC recruitment. Cell, 105, 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki N., Matsunami,N., Kanamori,H., Ishida,N., Shimizu,A., Yaoita,Y., Nikaido,T. and Honjo,T. (1987) The human IL-2 receptor gene contains a positive regulatory element that functions in cultured cells and cell-free extracts. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 5079–5086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cross S.L., Halden,N.F., Lenardo,M.J. and Leonard,W.J. (1989) Functionally distinct NF-kappa B binding sites in the immunoglobulin kappa and IL-2 receptor alpha chain genes. Science, 244, 466–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freimuth W.W., Depper,J.M. and Nabel,G.J. (1989) Regulation of the ILH2 receptor alpha-gene. Interaction of a kappa B binding protein with cell-specific transcription factors. J. Immunol., 143, 3064–3068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowenthal J.W., Ballard,D.W., Bohnlein,E. and Greene,W.C. (1989) Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces proteins that bind specifically to kappa B-like enhancer elements and regulate interleukin 2 receptor alpha-chain gene expression in primary human T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 2331–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Von Boehmer H. and Fehling,H.J. (1997) Structure and function of the pre-T cell receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 15, 433–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kruisbeek A.M., Haks,M.C., Carleton,M., Michie,A.M., Zuniga-Pflucker,J.C. and Wiest,D.L. (2000) Branching out to gain control: how the pre-TCR is linked to multiple functions. Immunol. Today, 21, 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gounari F., Aifantis,I., Khazaie,K., Hoeflinger,S., Harada,N., Taketo,M.M. and Von Boehmer,H. (2001) Somatic activation of beta-catenin bypasses pre-TCR signaling and TCR selection in thymocyte development. Nature Immunol., 2, 863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schorle H., Holtschke,T., Hunig,T., Schimpl,A. and Horak,I. (1991) Development and function of T cells in mice rendered interleukin-2 deficient by gene targeting. Nature, 352, 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cortes M., Wong,E., Koipally,J. and Georgopoulos,K. (1999) Control of lymphocyte development by the Ikaros gene family. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 11, 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J., Sif,S., Jones,B., Jackson,A., Koipally,J., Heller,E., Winandy,S., Viel,A., Sawyer,A., Ikeda,T., Kingston,R. and Georgopoulos,K. (1999) Ikaros DNA-binding proteins direct formation of chromatin remodeling complexes in lymphocytes. Immunity, 10, 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molnar A. and Georgopoulos,K. (1994) The Ikaros gene encodes a family of functionally diverse zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 8292–8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Avitahl N., Winandy,S., Friedrich,C., Jones,B., Ge,Y. and Georgopoulos,K. (1999) Ikaros sets thresholds for T cell activation and regulates chromosome propagation. Immunity, 10, 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alvarez J.D., Yasui,D.H., Niida,H., Joh,T., Loh,D.Y. and Kohwi-Shigematsu,T. (2000) The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev., 14, 521–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agalioti T., Lomvardas,S., Parekh,B., Yie,J., Maniatis,T. and Thanos,D. (2000) Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-beta promoter. Cell, 103, 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]