Abstract

Aim

The current study emphasizes the impact of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and Drug-Related Problems (DRPs) caused by supportive care medications administered with chemotherapy.

Method

This is a longitudinal observational study carried out at the Ramaiah Medical College Hospital in Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, at the Department of Oncology. The data was recorded using a specifically created data collecting form. Based on the PCNE (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe), DRPs are identified. The WHO probability scale, Modified Hartwig and Siegel for ADR severity assessment, Naranjo's algorithm for causality assessment, Rawlins and Thompson for predictability assessment, and Modified Shumock and Thornton for preventability assessment were all utilized. The OncPal guideline was considered in terms of the precision of supportive care medications regarding the reduction of ADRs in cancer patients.

Result

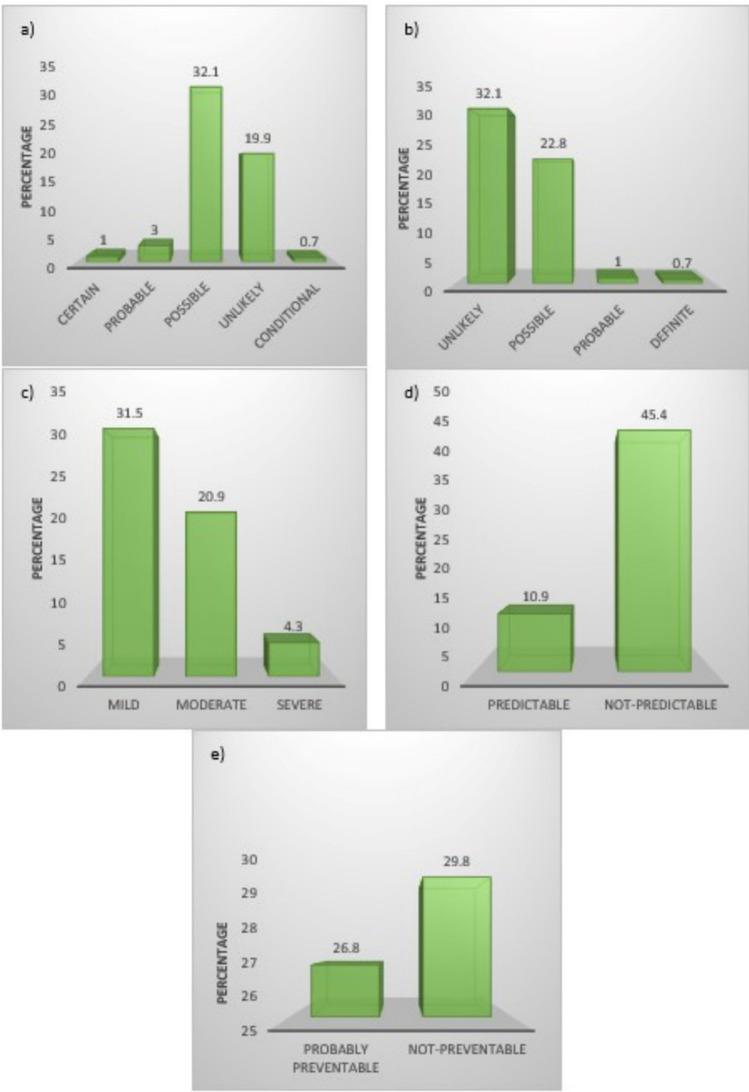

We enrolled 302 patients,166 (55%) female and 136 (45%) male (SD 14.378) (mean 49.97), patients with one comorbidity 59(19.6%) and multimorbidity (two or more) 45(14.9%), the DRPs identified were found to be 153 (50.6%); only P2 (safeties of drug therapy PCNE) were considered in this study. ADRs which are identified 175(57.9%) contributed/caused by the supportive care medications. WHO probability scale: 97 (32.1%) possible and 60 (19.9%) unlikely; Naranjo’s algorithm: 97 (32.1%) unlikely and 69 (22.8%) possible; ADR severity assessment scale (Modified Hartwig and Siegel): 95 (31.5%) mild and 63 (20.9%) moderates; Rawlins and Thompson for determining predictability of an ADR: 33 (10.9%) predictable and 137 (45.5%) non-predictable; and Modified Shumock and Thornton for determining preventability of an ADR: 81 (26.8%) probably preventable and 90 (29.8%) non-preventable. The statistical comparison through preforming t-test and measuring Chi-Square between group with ADRs and without ADRs shows in some variables, significantly (Alcohol consumption status, P = .019) and Easter Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status P < 0.001.

Conclusion

Comprehensive assessment of supportive medications in cancer patients would enhance the patient management and therapeutic outcome. The potential adverse drug reactions (ADRs) caused by supportive care medications can contribute to longer hospital stays and interact with the systemic anti-cancer treatment. The health care professionals should be informed to monitor the patients clinically administered with supportive medications.

Keywords: Supportive care medication, Drug-related problem, Adverse drug reaction, PCNE classification, OncPal guideline

Introduction

Any incident or situation pertaining to drug therapy that modifies (actually/potentially) the intended health outcome is classified as a drug-related issue under the PCNE classification [1]. DRPs have a great deal of unintended consequences, including significant rates of death, morbidity, and prolonged hospital stays and admissions. As a result, the families and the healthcare system bear a heavy financial burden. Therefore, improving patients’ safety status is the goal, and DRP prevention might help achieve this. Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs) and Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) will rise due to complicated medication regimens and a variety of pharmacological agents, which might make patient care challenging [2].

Pharmacy practice is a systematic program that helps hospital pharmacists get the optimum medication therapy by analyzing clinical data and performing appropriate patient evaluations, it really plays a significant role in enhancing drug efficacy and safety. In order to identify and trace the DRPs, this would be carried out in coordination with other healthcare professionals. Numerous variables, including possible drug-drug interactions and ineffectiveness, might lead to drug-related issues and impede treatment outcomes [3]. DRPs rise in oncology ward as a result of adverse drug reactions (DDIs) brought on by complicated cancer medications, which worsen morbidity and death [4]. In order to determine the optimal course of treatment and reduce the financial burden associated with hospital stays and further emergency room visits, it is imperative that DRPs must be detected and evaluated [5]. Studies have shown constantly, adverse reactions in cancer patients significantly influenced by factors such as patient quality of life [6-8], stage and type of the illness[9], specificity of the therapeutic course, age, gender, diet and comorbidities[10- 13]. Given the importance of identifying any cause that might result in ADR, it is particularly vital to consider DRPs, especially in susceptible groups like cancer patients [14, 15]. These individuals, due to their weakened health state and issues stemming from chemotherapy and their illness, are highly susceptible to the adverse effects of ADR. Therefore, it is essential to be mindful of the potential causes of ADR, including DRPs, when working with vulnerable populations like cancer patients [16, 17].

Pharmaceutical care provides the right strategy and ensures that patients receive the best treatment from several areas such as dosage, frequency, route of administration, etc., in order to meet therapeutic objectives and an appropriate patient's quality of life [18]. The most important factor affecting cancer patients, especially the elderly population, is polypharmacy, which raises the prevalence of DRP [19- 22]. Such a disease might be brought on by DRPs, which would impact the treatment strategy [23, 24].

DRPs could happen in different parts of the prescription process, from treatment, which is given during hospital admission, to discharge medications [25]. When the treatment doesn’t go according to the plan, then ADRs will be the result. A study shows that about 17% of hospital admissions occur due to the presence of ADRs, which can cause complications and even death [26]. To prevent such an event, it is crucial to identify and trace all the DRPs so patients will face less burden and complications in their treatment process.

While it is difficult to stop every DRP incident, pharmacy practice may play a significant role in preventing DRPs through patient evaluation. By studying and tracking DRPs early on, however, treatment outcomes can be enhanced [27]. Patients who are more vulnerable to DRPs, such as those with cancer, must be carefully assessed and closely monitored, in order to ensure that any consequences resulting from the existence of DRPs are addressed. Currently available causation tools are insufficient for DRP detection. In addition, a cohesive team of various healthcare providers who are willing to work together should be established in order for them to make a substantial contribution to the patient. This study focused on the occurrence of ADRs and DRPs caused by supportive medications among patients administered with chemotherapy. The goal is to create alertness on potential drug interactions occurring with supportive medications during chemotherapy treatment, which would undoubtedly have an impact on the patients’ ability to get through their therapeutic course.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted amongst cancer patients ≥ 18 years and admitted in the Department of Medical Oncology for a duration of 14 months from December 2022 to January 2024. The protocol was approved by institutional Ethics Committee of Ramaiah Medical College, Bangalore, India with the reference number ECR/215/Inst/KA/2013/RR-22. The data was collected from patients in a suitable data collection form after obtaining informed consent from the patients or the care takers. The consent form was translated into local language Kannada before obtaining consent. The data was collected from the patient medical records, laboratory reports and by interaction with the patients and care takers.

ADRs identified by oncologists were documented in addition to the data collection. criteria for determining preventability of an ADR (modified Shumock and Thornton) [28], The WHO probability scale [29], Naranjo's algorithm [30], ADR severity assessment scale (modified Hartwig and Siegel) [31], criteria for determining predictability of an ADR (Rawlins and Thompson) [32], were among the causality assessment criteria used to evaluate the ADR pattern.

The DRPs detection has been done by PCNE classification since this is an observational study; thus, (I) and (A) are not used; only (P) domain (P2) is used in this study. The detected DRPs were classified according to the PCNE Classification for Drug-Related Problems V9.1. It includes five domains: problem (P), cause (C), planned interventions (I), intervention acceptance (A), and outcome of DRP (O), and for DDIs, Stockley’s drug interaction text book and Drug Interactions Checker by Medscape are used as a reference sources.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adult patients aged ≥ 18 who were admitted to the Medical Oncology Ward and had or did not have comorbidities were included in this study. Patients who underwent radiotherapy without chemotherapy (during the time of study) and those who did not sign the consent form were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the demographic data, Baseline characteristics and ADR pattern was described and analyzed in terms of percentages. Kolmogorov Smirnov test, graphical methods and range of variation was used to test to normality of the data. Independent sample T test was used to compare the continuous data between patients with ADR and without ADR. Chi square test was used to compare the categorical data between two groups. the SPSS version 23 was used to analyze the data that was transferred from the collection form to an excel sheet. P value which is < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline demographic

The sample consisted of 302 adult patients, 166 (or 55% of the total) were female, and 136 (or 45%) were male. The participants' average age is 49.97. Additional patient details were noted, including nutrition, level of education (which PUC refers to Pre-University Course, UG refers to Under Graduate and PG is Post Graduate), marital status and so on (Table 1) presents baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study population

| DRP characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 136 (45) |

| Female | 166 (55) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 93 (30.8) |

| Until 5th grade | 43 (14.2) |

| 6th–10th grade | 91 (30.1) |

| PUC | 43 (14.2) |

| UG | 23 (7.9) |

| PG | 9 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 277 (91.7) |

| Single | 23 (7.9) |

| Widower | 2 (0.7) |

| Diet | |

| Vegetarian | 63 (21) |

| Mixed (vegetarian and non-vegetarian) | 239 (79) |

| Alcohol | |

| Non-alcohol | 265 (87.7) |

| Current | 20 (6.6) |

| Former | 17 (5.6) |

| Smoking | |

| No-smoking | 263 (87.1) |

| Current | 24 (7.6) |

| Former | 15 (5) |

| Sleep | |

| No-disturbance | 205 (67.9) |

| Disturbed | 97 (32.1) |

| Exercise | |

| No-exercise | 224 (74.2) |

| Exercise | 78 (25.8) |

| Allergy | |

| With allergy | 9 (3) |

| No-allergy | 293 (97) |

Prevalence of cancer and comorbidity

Gastrointestinal cancer was diagnosed at 68 (22.5%), followed by head and neck cancer at 34 (11.3%), lymphoid cancer at 29 (9.6%), cervical cancer at 27 (8.6%), leukemia at 21 (7%), lung cancer at 17 (5.6%), ovarian cancer at 9.0%, brain cancer at 7.3%, and other cancer types like testis, elbow, skin, urinary bladder, renal, and others 39 (17.6%). Gastrointestinal cancer is the most common type of cancer. Of the patients, 96 (31.8%) are taking less than five drugs, while 197 (65.2%) are taking five or more. 107 (35.4%) of the comorbidities include hypertension 34 (11%), type 2 diabetes mellitus 16 (5.3%) and other conditions. 14 (4.6%) people have type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension; 9 (3%), hypothyroidism; respiratory disorders such as asthma; and other diseases 6 (2.0%), type 2 diabetes mellitus, and disorders of the cardiovascular system, including deep vein thrombosis and ischemic heart disease, 4 (1.3%), HIV (human immunodeficiency viruses) with the incident of 3 (1%), acute renal illness, and two (0.7%) cases of hepatitis B surface antigen positive (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of cancer, comorbidities and polypharmacy

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Extension of cancer | |

| Locally advanced | 222 (73.5) |

| Metastatic | 80 (26.5) |

| Type of cancer | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 68 (22.5) |

| Breast cancer | 42 (13.9) |

| Lung cancer | 17 (5.6) |

| Head and neck cancer | 34 (11.3) |

| Cervical cancer | 27 (8.9) |

| Leukemia | 21 (7) |

| Lymphoid | 29 (9.6) |

| Ovary cancer | 9 (3) |

| Brain cancer | 7 (2.3) |

| Urinary bladder and renal | 3 (1) |

| Skin cancer | 1 (0.3) |

| Testis cancer | 2 (0.7) |

| Elbow cancer | 1 (0.3) |

| Multiple myeloma | 9 (3) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 7 (2.3) |

| Others | 19 (9.35) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 16 (5.3) |

| Hypertension | 34 (11.3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 9 (3) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension | 14 (4.6) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism | 9 (3) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, deep vein thrombosis | 4 (1.3) |

| Respiratory (asthma and pulmonary tuberculosis) | 6 (2) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism | 1 (0.3) |

| Hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus | 3 (1) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | 3 (1) |

| Acute kidney disease | 3 (1) |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen positive | 2 (0.7) |

| No-comorbidities | 198 (65.6) |

| Polypharmacy | |

| 5 or more than 5 medications | 197 (65.2) |

| Less than 5 medications | 105 (34.8) |

Adverse events

When the patient was being examined by the oncologist during follow up (while patient admitted in the Medical Oncology Ward), all ADRs found were noted and categorized according to organ systems and then we evaluated drug suspected, of course some of the identified ADRs are disease related and some of them are blood product related for hematologic cancer population. Peripheral neuropathy is the most common cause of ADRs in the central nervous system (CNS), accounting for 48 incidents (27.3%), of which anticonvulsant, antimicrobial, and psychotropic drugs might also participate in ADR occurrence along with SACTs. fever (10.7%) which could be due to antimicrobials. Another ADR that has been identified is in gastrointestinal (GI) system, vomiting accounting for the largest percentage at 25 (14.2%), other common ADRs are diarrhea (10.7%), nausea (5.8%) which might be related to antiemetics and opioids, acute gastritis (5.8%), in that order. The hematologic ADR pattern comprises of three types of febrile neutropenia (10.7%) which antimicrobials could participate in the occurrences, thrombocytopenia (3.7%), and non-febrile (3.4%) which are disease related. there is oral mucositis with an incident rate of 17 (9.7%), oral mucositis grade (3), with a frequency of 2 (1.1%) which is due to SACTs, Acute liver damage (0.3%) which antimicrobial such as trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole could be drug suspected, transaminitis (1.1%) could occur by NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and antifungals.

ADR causality, severity, predictability, and preventability

As mentioned in Fig. 1 WHO UMC, Scale World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Center, 97 (32.1%) are possible, 60 (19.9%) are unlikely, and Naranjo’s algorithm is 97 (32.1%) unlikely, 69 (22.8%) possible. Hartwig & Seigel: 95 (31.5%) mild, 63 (20.9%) moderate, Rawlins & Thompson: 33 (10.9%) predictable, 137 (45.4%) non-predictable, Shumock & Thornton: 81 (26.8%) probably preventable, and 90 (29.8%) non-preventable.

Fig. 1.

Causality Assessment: a WHO-UMC probability scale b NARANJO’S algorithm c ADR severity assessment scale Modified Hartwig and Siegel d Predictability of an ADR Rawlins and Thompson e Preventability of an ADR Modified Shumock and Thornton

Statistical comparison on patient’s demographic characteristics based on ADR occurrences

In addition to analyzing demographics in the population of study, statistical measurements were made in both the group with ADR and the group without ADR, as depicted in Table 4, all demographic characteristics were statistically analyzed in both groups and some variables such as alcohol consumption status (P = 0.019) with a Chi-Square value of 7.877), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (P = 0.000), showed statistically significant results. However, statistical analysis reveals no significant difference between patients with and without ADR in variables such as polypharmacy and cancer type (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Demographic comparison and statistical analysis between group with ADR and without ADR

| Characteristic | Overall N = 302 |

ADR | Chi square value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 136 (45.03%) | 61 (44.9%) | 75 (55.1%) | 0.796 | 0.372 |

| Female | 166 (54.96%) | 66 (39.8%) | 100 (60.2%) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 277 (91.72%) | 117 (42.2%) | 160 (57.8%) | 1.475 | 0.478 |

| Single | 23 (7.61%) | 10 (43.5%) | 13 (56.6%) | ||

| Widow/widower | 2 (0.66%) | 0.0% | 2 (100.0%) | ||

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 92 (30.46%) | 46 (50.0%) | 46 (50.0%) | 6.517 | 0.368 |

| Until 5th grade | 43 (14.23%) | 18 (41.9%) | 25 (58.1%) | ||

| ≥ 6–10th grade | 91 (30.13%) | 33 (36.3%) | 58 (63.7%) | ||

| PUC | 43 (14.23%) | 15 (34.9%0 | 28 (65.1%) | ||

| UG | 23 (7.61%) | 12 (52.2%) | 11 (47.8%) | ||

| PG | 9 (2.98%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) | ||

| Diet | |||||

| Vegetarian | 63 (20.86%) | 26 (41.3%) | 37 (58.7%) | 119 | 0.989 |

| Mixed | 239(79.13%) | 126(52.7%) | 113(43.0%) | ||

| Alcohol | |||||

| Non-alcoholic | 265 (87.74%) | 114 (43.0%) | 151 (57.0%) | 7.877 | 0.019 |

| Current alcoholic | 20 (6.62%) | 11 (55.0%) | 9 (45.0%) | ||

| Former alcoholic | 17 (5.62%) | 2 (11.8%) | 15 (88.2%) | ||

| Sleep | |||||

| Disturbed | 205 (67.88%) | 84 (41.0%) | 121 (59.0%) | 304 | 0.581 |

| No-disturbance | 97 (32.11%) | 43 (44.3%) | 54 (55.7%) | ||

| Smoking | |||||

| Non-smoker | 263 (87.08%) | 113 (43.0%) | 150 (57.0%) | 1.549 | 0.461 |

| Current smoker | 24 (7.94%) | 10 (41.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | ||

| Former smoker | 15 (4.96%) | 4 (26.7%) | 11 (73.3%) | ||

| Exercise | |||||

| Exercise activity | 224 (74.17%) | 96 (42.9%) | 128 (57.1%) | 887 | 0.642 |

| No exercise | 77 (25.49%) | 31 (40.3%) | 46 (59.7%) | ||

| Allergy | |||||

| With allergy | 9 (2.98%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 3.645 | 0.056 |

| No allergy | 293 (97.01%) | 126 (43.0%) | 167 (57.0%) | ||

| Cancer type | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | 68 (22.51%) | 27 (39.7%) | 41 (60.3%) | 16.294 | 0.363 |

| Breast | 42 (13.90%) | 18 (42.9%) | 24 (57.1%) | ||

| Lung | 17 (5.62%) | 8 (47.1%) | 9 (52.9%) | ||

| Head and neck | 34 (11.25%) | 10 (29.4%) | 24 (70.6%) | ||

| Cervix | 27 (8.94%) | 11 (40.7%) | 16 (59.3%) | ||

| Prostate | 4 (1.32%) | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Leukaemia | 21 (6.86%) | 14 (66.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | ||

| Lymphoid | 29 (9.60%) | 11 (37.9) | 18 (62.1%) | ||

| Urinary blader and renal | 3 (0.99%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | ||

| Skin | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Ovary cancer | 9 (2.98%) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | ||

| Testis | 2 (0.66%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | ||

| Elbow | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Brain | 7 (2.31%) | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | ||

| Others | 35 (11.58%) | 15 (42.9%) | 20 (57.9%) | ||

| Extension of disease | |||||

| Metastasis | 87 (28.80%) | 36 (87.85) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.005 | 0.367 |

| Locally advanced | 215 (71.19%) | 94 (43.7%) | 121 (56.3%) | ||

| Comorbid | |||||

| No-comorbid | 195 (64.56%) | 81 (41.5%) | 114 (58.5%) | 612 | 0.736 |

| With one or two comorbid | 103 (34.10%) | 45 (43.7%) | 58 (56.3%) | ||

| More than two comorbid | 4 (1.32%) | 1 (25.5%) | 3 (75.5%) | ||

| Associated comorbidities | |||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 16 (5.29%) | 7 (43.8%) | 9 (56.3%) | 10.600 | 0.390 |

| Hypertension | 34 (11.25%) | 14 (41.2%) | 20 (58.8%) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 9 (2.98%) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension | 14 (4.63%) | 3 (21.4%) | 11 (76.6%) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism | 9 (2.98%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, deep vein thrombosis | 4 (1.32%) | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | ||

| Respiratory (asthma and pulmonary tuberculosis) | 6 (1.98%) | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism | 1 (0.33%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | ||

| Hypertension, pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 3 (0.99%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | ||

| Others | 8 (2.64%) | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||

| Polypharmacy | |||||

| Less than 5 medications | 197 (65.23%) | 80 (40.6%) | 117 (59.4%) | 4.888 | 0.087 |

| 5 or more than 5 medications | 105 (34.76%) | 49 (59.7%) | 56 (58.3%) | ||

| DRP (P2.1) | |||||

| No DRP | 168 (55.62%) | 76 (45.2%) | 92 (54.8%) | 1.576 | 0.209 |

| With DRP | 134 (44.37%) | 51 (38.1%) | 83 (61.9%) | ||

| ECOG | |||||

| 0 | 70 (23.17%) | 68 (97.1%) | 2 (2.9%) | 121.264 | 0.000 |

| 1 | 179 (59.27%) | 54 (30.2%) | 125 (69.8%) | ||

| 2 | 41 (13.57%) | 5 (12.2%) | 36 (87.8%) | ||

| 3 | 12 (3.97%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

Discussion

The reported ADRs which is identified by medical oncologist were assessed to determine the potential extent of their relationship with the DRPs. Only (P2) which is evaluating the drugs to see if there are any drug interactions, even in a potential status that the patient may or may not suffer from, are taken into consideration in this study. The primary goal of this study is to raise vigilance in the implementation of drug precision in supportive care medication, which will have an influence on patient treatment in terms of ADR incidence and consequences at the medical oncology ward. In terms of SACTs the adverse drug reactions bring tremendous burden for patient and healthcare provider to manage, due to its potent complex therapy, in this study we would like to highlight the fact that how to minimize this burden as much as possible, one of the crucial factor is to focus on drug precision in supportive care medication, for so many years this topic is studied, yet the problem exists and patients are facing incredible amount of pain and suffering whereas for some would not be possible to get through their chemotherapy.

As it shown in Table 3 the types of the ADRs which could have a strong connection with supportive drugs are mentioned, for example in case of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea which causes by SACTs also due to antiemetics and opioids as well. Due to ondansetron metabolism by CYP2D6 (the isoenzyme that forms an active tramadol metabolite), tramadol and ondansetron have a pharmacodynamic interaction (P450 CYT2D6). Most racemic tramadol forms undergo significant metabolism through distinct mechanisms, such as oxidation mediated by CYP2D6 to produce O-desmethyltramadol, which is 200 times more compatible with mu opioid receptors than the parent drug dosage [33, 34]. Because noradrenaline is a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, it exhibits a much lower median value for area under concentration–time curves for the active metabolite after a dose of tramadol. Therefore, ( +)-o-desmethyltramadol is the mediator factor for opioid receptor-mediated analgesia. On the other hand, ( +) and (−) tramadol contribute to analgesia through inhibition reuptake of neurotransmitter serotonin and noradrenaline [35, 36]. Though serotonin (5-HT) is known to influence pain responses through presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors in the spina dorsal horn, it is theoretically expected that ondansetron, an antagonist of 5-HT3 receptors, will create antagonistic effects with the medications that inhibit pain transmission. This phenomenon also applies to tramadol, an opioid that is not pure and functions by amplifying the effects of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin. It appears that ondansetron and tramadol can interact to provide tramadol effectiveness when ondansetron is prescribed concurrently. This interaction has been allowed in the clinical sector. The recommended outcome, which is decreased control pain, may be reached by increasing the dosage; however, this increase exacerbates nausea and vomiting, which ondansetron cannot adequately compensate for. In summary, ondansetron should not be used as an antiemetic in combination with tramadol [37]. Tramadol and ondansetron combine to produce serotonin syndrome, which manifests as a wide range of symptoms, including autonomic instability (autonomic dysfunction), which includes symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [38].

Table 3.

Non-SACTs related to ADR occurrences

| Class of drug | Drugs | N (%) | ADRs | N(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobials | Piperacillin | 15 (10) | Peripheral Neuropathy | 48 (27.4) |

| Ceftriaxone | 4 (2.8) | |||

| Levofloxacin | 10 (12.3) | |||

| Meropenem | 7 (5) | |||

| Anticonvulsants | Pregabalin | 9 (11.1) | ||

| Gabapentin | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Levetiracetam | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Phenytoin | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Psychotropic | Olanzapine | 13 (16) | ||

| Clobazam | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Antiemetic | Ondansetron | 57 (70.4) |

Nausea Vomiting Diarrhea |

8 (4.5) 25 (14.2) 10 (5.7) |

| Opioids | Tramadol | 54 (66.7) | ||

| Opioids | Tramadol | 54 (66.7) |

Nausea Vomiting Tachycardia Lethargy Blurred vision Dizziness |

5 (2.8) 20 (11.4) 1 (0.3) 28 (16) 1 (0.3) 1 (0.3) |

| Morphine | 6 (7.4) | |||

| Anticonvulsants | Gabapentin | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Levetiracetam | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Antimicrobials | Piperacillin | 15 (10) | Febrile neutropenia | 10(5.7) |

| Ceftriaxone | 4 (2.8) | |||

| Levofloxacin | 10 (12.30) | |||

| Meropenem | 7 (5) | |||

| Anticoagulant | Rivaroxaban | 5 (6.2) | Gum bleeding | 2 (1.1) |

| Laxative | Lactulose | 36 (44.4) |

Nausea Fatigue Muscle weakness Tingling sensation |

5 (2.8) 7 (4) 2 (1.1) 5 (2.8) |

| Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) | Gabapentin | 1 (1.2) |

Fatigue Fatigue grade 1 Fatigue grade 2 Fatigue grade 3 |

16 (5.3) 8 (4.5) 7 (4) 1 (0.3) |

| Levetiracetam | 2 (2.5) | |||

| Pregabalin | 9 (11.1) | |||

| Phenytoin | 1 (1.2) | |||

| Antimicrobials | Piperacillin | 15 (10) |

Fever High grade fever |

10 (5.7) 8 (4.5) |

| Ceftriaxone | 4 (2.8) | |||

| Meropenem | 7 (5) | |||

| Anticonvulsants | Levetiracetam | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Pregabalin | 9 (11.1) | |||

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone | 6 (7.40) | Acute gastritis | 5 (2.8) |

| Prednisolone | 6 (7.4) | |||

| NSAIDs | Aspirin | 6 (7.4) | ||

| Antimicrobials | Levofloxacin | 10 (12.3) | Epigastric burning sensation | 2 (1.1) |

| Laxative | Lactulose | 36 (44.4) | ||

| Opioids | Morphine | 6 (7.4) | Constipation | 5 (2.8) |

| Tramadol | 54 (66.7) | |||

| Antiemetic | Ondansetron | 57 (70.4) | Dysphagia | 4 (2.2) |

| Diuretic | Furosemide | 2 (2.5) | ||

| Antimicrobials | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 2 (2.5) | Acute liver injury | 1(0.3) |

| NSAIDs | Aspirin | 6 (7.4) | Transaminitis | 2(1.1) |

| Antifungals | Fluconazole | 4 (4.9) | ||

| Voriconazole | 11(13.6) |

Emmanuel Andres et al. [39] implicated non-chemotherapy drugs that induce febrile neutropenia, such as antibiotics like amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, piperacillin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and other molecules like acyclovir. According to Emmanuel Andres et al., all healthcare providers should be aware of their practice in terms of potential adverse reactions and apply it to their daily routine programs. Particular attention should be paid to these drugs especially in oncological population because febrile neutropenia occurs in most of the case due to SACTS and disease related and also due to antimicrobials as it is shown in Table 3, since it is highly prescribed in patients with hematological cancer either for empirical administration or prophylaxis.

Concurrent use of two or more CNS depressants (such as tramadol, morphine, pregabalin, and gabapentin) produces an addictive respiratory depressant and sedative effect [40]. the combination of these drugs as we know exacerbates ADRs such as lethargy, dizziness, constipation and blurred vision. Also, the bioavailability of gabapentin can be increased by morphine, and consequently, the analgesic efficacy would be enhanced. Gabapentin also induces the analgesic effect of morphine and other opioids.

Electrolyte imbalance is a very crucial aspect for patient management, for example, hypokalemia and hypokalemia induce nausea and vomiting, hypokalemia could increase ADRs such as muscle weakness, fatigue, tingling sensations which occurs in oncological population a lot. That being said, considering laxative which is prescribed highly due to constipation that most of cancer patients are facing and in a long term if this drug dose not monitored it would cause so many complications.

Peripheral neuropathy with the highest incident ADR occurrences which induce by SACTs and non-cancer specific medications such as antimicrobials, anticonvulsants and psychotropics as well, the intensity of peripheral neuropathy would increase if drug precision doesn’t consider regarding supportive care medications, the occurrence of ADRs such as tingling sensation, numbness, general weakness, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea and blurred vision could worsen patient’s condition. According to Table 3, other ADRs are mentioned such as gum bleeding, acute gastritis, epigastric burning sensation and transaminitis which shown with the drug suspected. our main focus is to reduce the high incident occurrences ADRs which impact on patient mostly. Even though the majority of non- specific cancer medications may not be prescribed for an extended period of time, it has been observed that some patients take these medications for a longer duration and frequency due to disease related problems. Therefore, knowledge of these medications may greatly enhance therapeutic precision thus any DDIs should be acknowledged and take to the consideration as a drug safety [41] and this is more significant in an oncological population.

Julian Lindsay et al. [42] mentioned in their study regarding the developing oncological palliative care guideline OncPal [42], the list of the drugs which are not benefit in patient, although this guideline is about palliative care patient with the short life expectancy, we considered in our study for determining the drugs could increase the ADRs in Medical Oncology Ward. Our aim is to highlights the correlation of supportive care medication in ADR occurrences while considering the majority of ADRs in cancer patients are due to potent chemotherapy. Our primary focus was on addressing ADRs that were associated with supportive medications. Specifically, we excluded adverse effects resulting from chemotherapy, such as Carboplatin hypersensitivity, extravasation, Bendamustine-induced rash, and chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis.

Cancer patients, particularly those who are undergoing watch-and-wait management in case of relapse, require precise medication and supportive drugs due to their susceptibility, resulting from disease progression and long-term therapy. This is crucial to prevent any additional complications [43–45].

According to Table 4 patients with higher ECOG scores were found to experience more ADRs. As a result, it is essential to closely monitor patients based on their supportive drug therapy, as disease progression can cause a variety of issues in all aspects of treatment.

Table 4, was shown the participation of patient’s background and ADR occurrences, although it was not statistically significant in most of the variable (P > 0.05), except ECOG (P < 0.001) and alcoholic consumption status with the P value of (0 0.019), the percentage of patient who had ADRs in most of the variable is higher, for example, the DRP = 134(44.37%) showing 83(61.9%) had ADRs compare to 51(38.1%) without ADRs (P = 0.209).

According to a study conducted by Amanda et al. [46], the extent of admissions in cancer patients due to ADRs was examined, as well as the role of chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy-induced ADRs. The study revealed that the percentage of ADRs caused by supportive drugs is similar to that caused by SACTs, highlighting the importance of awareness and monitoring of non-chemotherapy drugs. In our study, patients with drug-related problems exhibited a higher percentage of ADRs and experienced issues that resulted in delays in chemotherapy, discontinuation, and extended hospital stays.

Conducting a comprehensive assessment is important, especially for geriatric oncology patients, who are particularly vulnerable to experiencing adverse drug reactions (ADRs) due to their age-related frailty. This vulnerability can lead to a range of issues [47] The feasibility of assessment in geriatric oncology and its potential benefits for enhancing patient management and treatment outcomes have been demonstrated [48]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) advises conducting a special assessment for geriatric oncology patients aged 65 or more who are undergoing chemotherapy. The intention of this assessment is to recognize drug-related issues contributed by supportive care medications that could have been overlooked by the oncologist to acknowledged [49] Our study supports this approach, and we strongly recommend its application not just for geriatric oncology but also for adult patients under the age of 65 who are admitted in Medical Oncology Ward, as we have done in this study.

Conclusion

DRPs are present in the Medical Oncology Ward as a result of comorbid and disease-related problems. Therefore, it may be possible to significantly influence the severity of ADR occurrences and, consequently, patient care by recognizing and tracking DRPs. The unforeseen difficulties caused by DRPs can have an effect on patients' health and create a significant number of issues, which magnifies notably during chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

Authors express their deepest gratitude to the Faculty of Pharmacy, M S Ramaiah University of Applied Science, all the nursing staff and resident doctors of M S Ramaiah Medical College Hospital for their incredible cooperation.

Author contributions

BBT, EM, VVM contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection. Data analysis was performed by ASN. VVM performed project administration. BBT contributed writing the manuscription, EM supervised the study and reviewed the manuscription. All authors read and approved the manuscription.

Funding

No funding for the submitted work.

Data availability

The data used to support the finding of this study are included within the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the M. S. Ramaiah Medical College Hospital (MSRMCH), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, before to its start in December 2022. Prior to the start of the data collection procedure, the collecting form was accompanied with the consent form which was translated into Kannada language was signed by patient or family member. Ethics Committee, MS Ramaiah Medical College Hospital, Bangaluru, Karnataka, India is registered under DCGI (Drugs Controller General India) and Department of Health Services and works in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmed KO, Muddather HF, Yousef BA. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) drug-related problems classification version 9.1: first implementation in Sudan. J Pharm Res Int. 2021. 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i59a34321. 10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i59a34321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabil S, El-Shitany NA, Shawki MA, et al. A pharmaceutical care plan to minimize the incidence of potential drug-related problems in cancer patients. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2022;89:4874–80. 10.21608/EJHM.2022.260758. 10.21608/EJHM.2022.260758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garin N, Sole N, Lucas B, et al. Drug related problems in clinical practice: a cross-sectional study on their prevalence, risk factors and associated pharmaceutical interventions. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1–11. 10.1038/s41598-020-80560-2. 10.1038/s41598-020-80560-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yismaw MB, Adam H, Engidawork E. Identification and resolution of drug-related problems among childhood cancer patients in Ethiopia. J Oncol. 2020. 10.1155/2020/6785835. 10.1155/2020/6785835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Freitas GRM, Tramontina MY, Balbinotto G, et al. Economic impact of emergency visits due to drug-related morbidity on a Brazilian Hospital. Value Heal Reg Issues. 2017;14:1–8. 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.03.003. 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishii M, Soutome S, Kawakita A, et al. Factors associated with severe oral mucositis and candidiasis in patients undergoing radiotherapy for oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas: a retrospective multicenter study of 326 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1069–75. 10.1007/s00520-019-04885-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar A, Roy S, Bhandari M, et al. Current trends in management of oral mucositis in cancer treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(8):2019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawashita Y, Kitamura M, Soutome S, et al. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with severe radiationinduced mucositis in pharyngeal or laryngeal cancer patients: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1064. 10.1186/s12885-021-08793-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawashita Y, Soutome S, Umeda M, Saito T. Predictive risk factors associated with severe radiation-induced mucositis pharyngeal or oropharyngeal cancer patients: a retrospective study. Biomedicines. 2022;10(10):2661. 10.3390/biomedicines10102661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SC, Lai YH, Huang BS, Lin CY, Fan KH, Chang JT. Changes and predictors of radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with oral cavity cancer during active treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(3):214–9. 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Sanctis V, Bossi P, Sanguineti G, et al. Mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and systemic therapies: literature review and consensus statements. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;100:147–66. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebri E, Kiss A, Tóth F, Hortobágyi T. Female sex as an independent prognostic factor in the development of oral mucositis during autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15898. 10.1038/s41598-020-72592-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z, Huang L, Wang H, et al. Predicting nomogram for severe oral mucositis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma during intensity-modulated radiation therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Oncol. 2022;30(1):219–32. 10.3390/curroncol30010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlano MC, Monteverde M, Colantonio I, et al. Impact of age on acute toxicity induced by bio- or chemo-radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(10):1051–7. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morais-Faria K, Palmier NR, de Lima CJ, et al. Young head and neck cancer patients are at increased risk of developing oral mucositis and trismus. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(9):4345–52. 10.1007/s00520-019-05241-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao Z, Gao J, Qian L, et al. Factors associated with acute oral mucosal reaction induced by radiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective single-center experience. Medicine. 2017;96(50): e8446. 10.1097/MD.0000000000008446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vatca M, Lucas JJ, Laudadio J, et al. Retrospective analysis of the impact of HPV status and smoking on mucositis in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(9):869–76. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepler C, Strand L. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krustev T, Milushewa P, Tachkov K. Impact of polypharmacy, drug-related problems, and potentially inappropriate medications in geriatric patients and its implications for bulgaria-narrative review and metanalysis. Front Public Health. 2022;3:743138. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.743138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schindler E, Richling I, Rose O, et al. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) drug-related problem classification version 9.00: German translation and validation. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;43:726–30. 10.1007/s11096-020-01150-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleason KM. Results of the medications at transitions and clinical handofs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441–7. 10.1007/s11606-010-1256-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan JL, Sampson LL, Shojania M, K G, et al. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:397–403. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freyer J. Drug-related problems in geriatric rehabilitation patients after discharge—a prevalence analysis and clinical case scenario-based pilot study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14:628–37. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell K, Harrison J, Scahill S, Braund R, et al. Identifying drug-related problems during transition between secondary and primary care in New Zealand. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21:333–6. 10.1111/ijpp.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufmann CP, Stampfi D, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML, et al. Determination of risk factors for drug-related problems: a multidisciplinary triangulation process. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006376–e006376. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unroe KT. Inpatient medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: a retrospective cohort study of age and other risk factors for medication discrepancies. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8:115–26. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Mil F. Drug-related problems: a cornerstone for pharmaceutical care. J Malta Coll Pharm Pract. 2005;10:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ducharme MM, Boothby LA. Analysis of adverse drug reactions for preventability. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:157–61. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01130.x. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egberts TCG. Causal or casual? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:365–6. 10.1002/pds.1094. 10.1002/pds.1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Pharmaceulicjl-carc index Notes. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iftikhar S, Sarwar MR, Saqib A, Sarfraz M. Causality and preventability assessment of adverse drug reactions and adverse drug events of antibiotics among hospitalized patients: a multicenter, cross-sectional study in Lahore, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199456. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpe DA. Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid Mu receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59:385–90. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulsen L, Arendt-Nielsen L, Brøsen K, et al. The hypoalgesic effect of tramadol in relation to CYP2D6. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:636–44. 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90211-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamer UM, Musshoff F, Kobilay M, et al. Concentrations of tramadol and o-desmethyltramadol enantiomers in different CYP2D6 genotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:41–7. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borlak J, Hermann R, Erb K, et al. A rapid and simple CYP2D6 genotyping assay–case study with the analgetic tramadol. Metab Clin Exp. 2003;52:1439–43. 10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00256-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guidelines for codeine therapy in the context of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:321–6. 10.1038/clpt.2011.287. 10.1038/clpt.2011.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ. Serotonin syndrome presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2000;79:201–9. 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00001. 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrès E, Mourot-Cottet R, Maloisel F, et al. History and outcome of febrile neutropenia outside the oncology setting: a retrospective study of 76 cases related to non-chemotherapy drugs. J Clin Med. 2017;6:1–12. 10.3390/jcm6100092. 10.3390/jcm6100092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baxter K. Stockley’s drug interactions. Chicago, London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hulskotte LMG, Töpfer W, Reyners AKL, et al. Drug-drug interaction perpetrators of oxycodone in patients with cancer: frequency and clinical relevance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;80:455–64. 10.1007/s00228-023-03612-2. 10.1007/s00228-023-03612-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, et al. The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the ‘OncPal deprescribing guideline.’ Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:71–8. 10.1007/s00520-014-2322-0. 10.1007/s00520-014-2322-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludmir EB, Palta M, Willett CG, Czito BG. Total neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: an emerging option. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1497–506. 10.1002/cncr.30600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glimelius B. On a prolonged interval between rectal cancer (chemo)radiotherapy and surgery. Ups J Med Sci. 2017;122(1):1–10. 10.1080/03009734.2016.1274806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dossa F, Chesney TR, Acuna SA, Baxter NN. A watch-and wait approach for locally advanced rectal cancer after a clinical complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(7):501–13. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30074-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavan AH, et al. Adverse drug reactions in an oncological population: prevalence, predictability, and preventability. Oncologist. 2019;24:e968–77. 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubenstein LZ, Stuck AE, Siu AL, et al. Impacts of geriatric evaluation and management programs on defined outcomes: overview of the evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:8S-16S. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb05927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, et al. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1133–63. 10.1093/jnci/djs285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2326–47. 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the finding of this study are included within the manuscript.