Abstract

Although luminescent aluminum compounds have been utilized for emitting and electron transporting layers in organic light-emitting diodes, most of them often exhibit not phosphorescence but fluorescence with lower photoluminescent quantum yields in the aggregated state than those in the amorphous state due to concentration quenching. Here we show the synthesis and optical properties of β-diketiminate aluminum complexes, such as crystallization-induced emission (CIE) and room-temperature phosphorescence (RTP), and the substituent effects of the central element. The dihaloaluminum complexes were found to exhibit the CIE property, especially RTP from the diiodo complex, while the dialkyl ones showed almost no emission in both solution and solid states. Theoretical calculations suggested that undesired structural relaxation in the singlet excited state of dialkyl complexes should be suppressed by introducing electronegative halogens instead of alkyl groups. Our findings could provide a molecular design not only for obtaining luminescent complexes but also for achieving triplet-harvesting materials.

Subject terms: Excited states, Ligands, Photochemistry, Optical materials

Luminescent aluminum compounds have been utilized for emitting and electron transporting layers in organic light-emitting diodes, but most exhibit fluorescence as opposed to phosphorescence. Here, the photophysical properties of β-diketiminate aluminum complexes are shown to depend on the nature of the metal substituents, with a diiodoaluminum complex displaying room temperature phosphorescence.

Introduction

Aluminum complexes have been utilized as a Lewis acid in organic reactions and polymerizations and as a platform for constructing optoelectronic materials. In particular, luminescent aluminum complexes have been widely investigated since organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) were fabricated with tris(8-quinolinolato)aluminum (Alq3) as an emitting layer1–3. Their luminescence color can be tuned over whole visible region by modifying the electronic structure of their ligand moieties, especially in the case of 8-quinolinolate4 and salen5 complexes. However, most of these complexes exhibit only fluorescence rather than phosphorescence and critically weaker emission intensity in the solid state than that in the dilute solution state although they are required to show luminescent properties in the condensed state for the device applications. In addition, there are limited series of stable aluminum complexes which are able to exhibit remarkable emission properties2,6. Thus, it is still of great significance to explore a class of solid-state luminescent aluminum complexes, especially with room-temperature phosphorescence (RTP).

β-Diketiminate ligands are characterized by the two sp2-nitrogen atoms as the coordination centers. Compared to the corresponding acetylacetonate ligands, their steric and electronic demands are able to be easily tuned by the substituents on the nitrogen atoms as well as the carbon atoms. Therefore, these ligands have enabled to isolate reactive aluminum(I) species7, which have paved the way for accessing various fruitful chemical transformations, like inert-bond activations8–11. Furthermore, the series of the four-coordinated complexes of the group 13 elements have been synthesized by using those ligands12,13. Despite tremendous research efforts, the optical and/or electronic properties of aluminum(III) complexes with β-diketiminate ligands have not been mainly focused on probably because they have very weak absorption bands in the visible region due to the limited π-conjugation length within the β-diketiminate ligands. On the other hand, it has been reported that the β-diketiminate complexes of the group 13 elements exhibit solid-state emission14–22. These reports have shown that the π-conjugation system of the β-diketiminate ligands should extend within the whole ligand and lead to the efficient luminescence. Importantly, the luminescence efficiency of those complexes in the crystalline states is typically higher than those in the dilute solutions and amorphous solids. This phenomenon is called crystallization-induced emission (CIE) and is beneficial because those luminophores are potentially applied for OLEDs, chemo-sensors, bioimaging, and laser amplifiers23–25. The bulky peripheral aromatic groups of the β-diketiminate ligands could be probably responsible for the fast non-radiative decay processes in solution26 and prohibit π-stacking which leads to critical concentration quenching in the solid state24. Hence, these complexes could open up an avenue for achieving functional optical materials with solid-state luminescent properties based on aluminum27–34. Herein, we envisioned that a class of the π-extended β-diketiminate ligand serves as a scaffold to obtain efficient solid-state emission properties from aluminum complexes. Furthermore, aluminum allowed us to systematically evaluate the substituent effects at the central element on photophysical properties thanks to the easier access to aluminum complexes with different substituents than the other group 13 elements. As a result, it was demonstrated that dialkylaluminum and dihaloaluminum complexes are non-emissive and emissive, respectively, in crystalline states at room temperature. Theoretical calculations suggest that the alkyl substituents should lead to a significant structural relaxation at the excited state, which results in fast non-radiative quenching processes. Importantly, solid-state luminescent aluminum complexes were developed, especially the diiodoaluminum complex that exhibits efficient RTP with 0.54 of quantum yield.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

To assess the effects of substituents on aluminum on the photophysical properties of β-diketiminate complexes, we synthesized five compounds with different substituents (Fig. 1a). The isopropyl groups on the aromatic groups of the ligand (LH) were employed for the kinetic stabilization of the complex7,35–37. The dialkylaluminum complexes, LAlMe and LAlEt, were successfully synthesized by reacting trialkylaluminum with LH in toluene at 100 °C according to the literatures on the syntheses of the related complexes35,38,39. The dihaloaluminum complexes, LAlCl, LAlBr, and LAlI, were synthesized with the modified procedure of the related compounds through the reactions of LH and n-butyllithium followed by the treatment with the corresponding aluminum trihalides35,36. These molecular structures were characterized with 1H, 13C{1H} and 27Al{1H} NMR spectroscopies, high-resolution mass (HRMS) spectrometry, elemental analysis, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 1b–e).

Fig. 1. Aluminum complexes investigated in this study.

a Synthetic scheme of the dialkylaluminum and dihaloaluminum complexes. Single-crystal structures of b LAlMe, c LAlCl, d LAlBr, and e LAlI.

Photophysical properties at room temperature

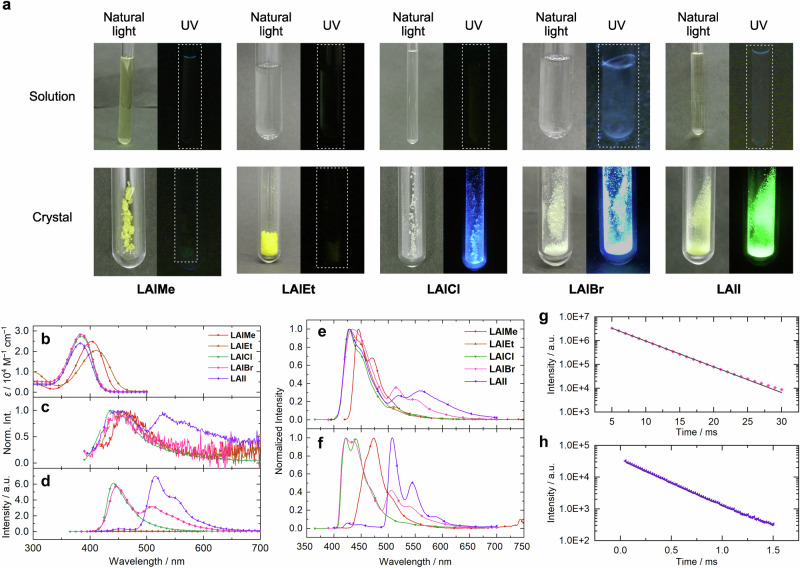

There are two significant effects from the substituents on the photoluminescent properties (Fig. 2a): (i) the dihaloaluminum complexes emit light in solid states at room temperature, while the dialkyl ones hardly show emission under the same condition; (ii) the emission color of the dihaloaluminum complexes depends on the type of halogen (LAlCl, blue; LAlBr, bluish white; LAlI, green). Meanwhile, all compounds exhibited almost no luminescence in the solution states at room temperature in the similar manner as shown in the previous reports15–17,40. The previous studies demonstrated that the conventional β-diketiminate complexes have the CIE property with blue emission in crystalline states at room temperature when neither electron-accepting nor donating substituent was introduced on the ligands. Therefore, the non-emissive nature of the alkylaluminum complexes and the halogen-dependent emission color are the peculiar features among this class of luminophores.

Fig. 2. Photophysical properties of aluminum β-diketiminate complexes.

a Photographic images of solutions and crystals of the complexes. UV, 365 nm. b, c UV–vis absorption and PL spectra in solutions at room temperature, respectively. d PL spectra in crystalline states at room temperature. e, f PL spectra in solutions and crystalline states at 77 K, respectively. g, h Phosphorescence decay curve of LAlBr (detected at 511 nm) and LAlI (detected at 515 nm) in crystalline states at room temperature, respectively. Solid lines represent fitting curves.

We conducted spectroscopic studies under nitrogen at room temperature to elucidate the electronic structures of the complexes (Fig. 2b–d and Table 1). First, UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded in the 2-methylpentane (2MP)/toluene solutions (99/1, v/v, 1 × 10−5 M) at room temperature (Fig. 2b). All compounds showed similar absorption spectra with slight difference in the position of absorption maximum. The shapes and positions of the longest-wavelength absorption bands were similar to the typical β-diketiminate complexes and assignable mainly to the π–π* (S0–S1) transition of the ligand moiety, suggesting that the electronic character of the ground-state structure of the complexes should not be affected by the substituents on the aluminum atom. Nevertheless, the substituents apparently change the S0–S1 transition energy probably due to their different contribution to the frontier orbitals41. Second, photoluminescent (PL) spectra were measured for the same solutions and their crystalline powders (Fig. 2c, d). As we presumed, quite weak and broad emission spectra were obtained from all solutions. Their absolute quantum yields (ΦPL) were lower than 0.01. In the crystalline state, LAlMe and LAlEt hardly exhibited emission enhancement (ΦPL < 0.01), while LAlCl, LAlBr, and LAlI showed significant emission spectra in the visible region. ΦPL values were determined to be 0.48 for LAlCl, 0.44 for LAlBr, and 0.58 for LAlI. Importantly, the PL spectra of LAlBr and LAlI composed two distinct bands in the blue and green regions. PL lifetime (τPL) measurements revealed that the shorter-wavelength bands possessed nanosecond-order τPL, while the longer-wavelength ones had microsecond-order τPL (Fig. 2g, h and Table 2). Finally, their PL spectra recorded after several milliseconds after photoexcitation showed only longer-wavelength component (Supplementary Fig. 1). Consequently, the blue- and green-emission bands were assignable to fluorescence and phosphorescence, respectively. These data mean that the heavy atom effect of bromine and iodine should lead to the RTP properties of LAlBr and LAlI. The estimated phosphorescence quantum yield (ΦP) value of LAlI (0.54) is the highest one among the aluminum complexes. It is also of interest to note that the related boron complexes with iodine on the peripheral aromatic rings hardly show apparent RTP18. The heavy atoms directly attached on the central element might efficiently accelerate intersystem crossing and phosphorescence processes.

Table 1.

Results of photophysical measurements at room temperaturea

| λabs/nm | ε/104 M−1 cm−1 | λFluo/nm | λPhos/nm | ΦF | ΦP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAlMe | Solution | 403 | 2.5 | 460 | n.d. | <0.01 | – |

| Crystal | – | – | 473 | n.d. | <0.01 | – | |

| LAlEt | Solution | 410 | 2.0 | 458 | n.d. | <0.01 | – |

| Crystal | – | – | 480 | n.d. | <0.01 | – | |

| LAlCl | Solution | 386 | 2.8 | 436 | n.d. | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Crystal | – | – | 442 | n.d. | 0.48 | – | |

| LAlBr | Solution | 385 | 2.9 | 441 | n.d. | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Crystal | – | – | 447 | 511 | 0.25 | 0.19 | |

| LAlI | Solution | 384 | 2.4 | 450 | 528 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Crystal | – | – | 454 | 515 | 0.04 | 0.54 |

aPhotoluminescence properties were recorded with photoexcitation at the absorption maximum wavelength in the solution state at room temperature. Solution, 1 × 10−5 M in 2-methylpentane/toluene (99/1, v/v); crystal, recrystallized from hexane; –, not determined. Phosphorescence spectra were recorded with pulsed excitation. Quantum yields of fluorescence and phosphorescence were estimated by absolute quantum yields and deconvoluted photoluminescence spectra with multi-component Gaussian functions.

Table 2.

PL lifetime and estimated rate constants at room temperaturea

| <τF>/ns | <τP>/ms | krS/107 s−1 | knrS/107 s−1 | kISCS/107 s−1 | krT/102 s−1 | knrT/102 s−1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAlCl | Solution | <0.03 | – | >3.3 | >3300 | >3.3 | – | – |

| Crystal | 2.1 | – | 34 | 31 | 6.4 | – | – | |

| LAlBr | Solution | <0.04 | – | >2.5 | >2500 | >25 | – | – |

| Crystal | 2.0 | 4.0 | 13 | 16 | 23 | 1.1 | 1.4 | |

| LAlI | Solution | <0.04 | 0.10 | >1.0 | >2200 | >250 | 0.4 | 100 |

| Crystal | 0.14 | 0.29 | 29 | 10 | 680 | 20 | 15 |

a<τF> and <τP>, average fluorescence and phosphorescence lifetimes, respectively; krS, radiative decay rate constant from singlet state (fluorescence); knrS, non-radiative decay rate constant from singlet state (internal conversion); kISCS, intersystem crossing rate constant from singlet state; krT, radiative decay rate constant from triplet state (phosphorescence); knrT, non-radiative decay rate constant from triplet state. <τF> values for solutions are upper limits estimated by the streak camera system. krS, knrS, and kISCS values for solutions are lower limits calculated from the upper limit of the <τF> values.

From the fluorescence and phosphorescence quantum yields and PL lifetime measurements with the dihaloaluminum complexes at room temperature, rate constants of each photophysical processes were estimated (Table 2). For the detailed procedure, see Supplementary Figs. 2–6, Supplementary Tables 2–5, and Supplementary Notes 1, 2. Although their PL decay profiles in solutions were close to the incident light pulse in terms of time resolution, the apparent fluorescence decay curves were observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, the upper limits of fluorescence lifetime were estimated from the decay curves for calculating the lower limits of each rate constant. For all three complexes in the solution states, quite large non-radiative decay rate constants for singlet states (knrS~1010 s−1) were obtained, suggesting that most excited molecules would be quenched nonradiatively through the internal conversion from S1 to S0 probably because this process could occur through conical intersections26. Only in the case of LAlI, the rapid intersystem crossing process derived from the strong heavy atom effect of iodine could occur to some extent (kISC/knrS ~ 0.1). On the other hand, the crystals of these complexes exhibited at least 100 times smaller knrS values than their solutions, leading to their CIE properties. In the cases of LAlBr and LAlI, the suppression of the internal conversion should open the intersystem crossing processes as well as fluorescence. It is worth noting that the radiative rate constant from singlet states (krS) and kISCS of some complexes were enhanced by the crystallization, which might originate from the intermolecular interactions and could contribute to their CIE properties.

Photophysical properties at 77 K

To gain further information about the photophysical processes, we recorded PL spectra of the solutions and crystalline powders at 77 K with a cryostat under nitrogen atmosphere (Fig. 2e and Table 3). Importantly, all compounds clearly exhibited phosphorescence in the frozen solution state, probably because the non-radiative decay processes could be closed at the low temperature. Indeed, the hypsochromic shifts of the emission band were observed, indicating that structural changes in the excited state should be hampered under the frozen environment. In other words, it is suggested that there are significant structural relaxations in the excited state that cause non-radiative decay of the singlet excited states in room-temperature solutions. Interestingly, LAlMe and LAlCl exhibited phosphorescence at 77 K, despite the absence of heavy atoms, implying the intrinsic triplet-forming properties of these series of compounds40. In the crystalline states at 77 K, the slight hypsochromic shifts of emission bands were observed except for LAlMe. These shifts might originate from the tight packing of the crystals. On the other hand, the bathochromic shift for the crystal of LAlMe might be attributed to the weakening of the 0–0 band. Significantly, the apparent crystallization-induced phosphorescence enhancement was observed from LAlI. The estimated ΦPhos in crystal was 2.2 times higher than that in the frozen solution, possibly because of the acceleration of intersystem crossing and phosphorescence processes and because the restriction of non-radiative decay from excited triplet states.

Table 3.

Results of photoluminescence measurements at 77 Ka

| λFluo/nm | λPhos/nm | ΦFluo | ΦPhos | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAlMe | Solution | 445 | 541 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Crystal | 474 | 569 | 0.25 | n.d. | |

| LAlEt | Solution | 429 | 530 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Crystal | 429 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| LAlCl | Solution | 428 | 510 | 0.93 | 0.03 |

| Crystal | 422 | 535 | 0.96 | 0.04 | |

| LAlBr | Solution | 435 | 514 | 0.56 | 0.35 |

| Crystal | 422 | 506 | 0.56 | 0.26 | |

| LAlI | Solution | 426 | 515 | 0.13 | 0.33 |

| Crystal | 425 | 507 | 0.03 | 0.74 |

aExcited at the absorption maximum wavelength in solution state at room temperature. Solution, 1 × 10−5 M in 2-methylpentane/toluene (99/1, v/v); crystal, recrystallized from hexane; n.d., not determined due to negligible phosphorescence. Phosphorescence spectra were recorded with pulsed excitation. Quantum yields of fluorescence and phosphorescence were estimated by absolute quantum yields and deconvoluted photoluminescence spectra with multi-component Gaussian functions.

Theoretical calculations

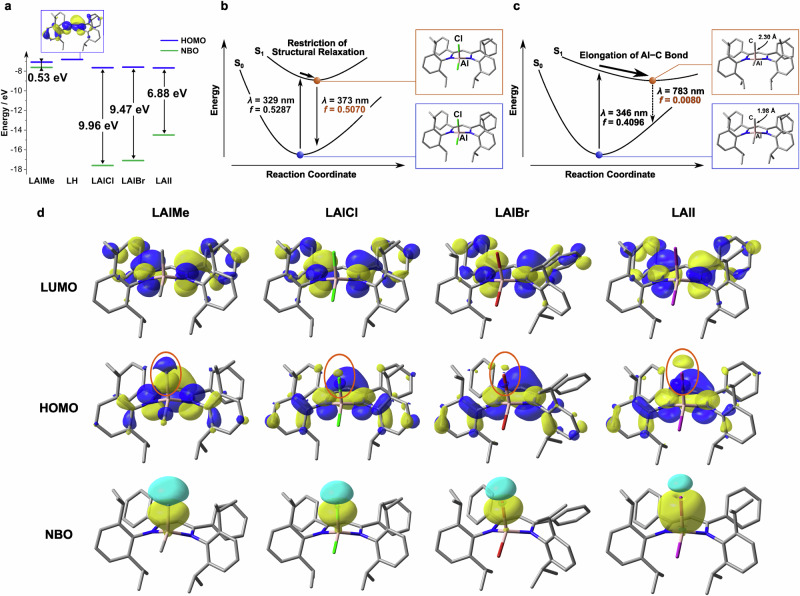

Density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 package42 to study the electronic structures of the dimethylaluminum and dihaloaluminum complexes (Fig. 3). Geometry optimization was performed for both S0 and S1 states with the CAM-B3LYP functional and the Lanl2DZ basis set for I and the 6-31G(d,p) one for the other atoms, followed by single-point transition energy calculations at the same level of theory except for the basis set for the light atoms (6-311++G(d,p)). The significant structural relaxation at the S1 state was estimated only for LAlMe, leading to the narrow S0–S1 energy gap (1.58 eV) and the small oscillator strength (f = 0.0080). The most characteristic change in the relaxation was the elongation of one of the Al–C bonds from 1.98 Å (S0) to 2.30 Å (S1). At the S0 geometry, its Kohn–Sham highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) was significantly delocalized over the Al–C bond as well as the ligand moiety, while the Kohn–Sham lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) possessed little contribution from this bond because of a nodal plane passing through it (Supplementary Tables 15 and 16). Hence, the electron density between aluminum and carbon atoms should decrease upon the photoexcitation from S0 to S1, resulting in the weakening of the bond and the considerably large structural relaxation at the S1 state. Similar photoinduced bond weakening or activation of Al–C bond have been reported in other systems of photochemical reactions43–46. For the resulted S1 geometry, the HOMO mainly located at the Al–C moiety, where the HOMO–LUMO overlap much less effectively than that for the S0 geometry, making the f value of the S1–S0 transition smaller. Therefore, it is suggested that the structural relaxation should be responsible for the non-radiative decay process of the dialkylaluminum complexes.

Fig. 3. Results of (TD-)DFT calculations.

a Calculated energies of Kohn–Sham HOMO and NBO of the corresponding Al–X (X = Me, Cl, Br, and I) bond. b, c Optimized geometries and energies of LAlCl and LAlMe, respectively, at S0 and S1 states. d Kohn–Sham HOMO, LUMO, and NBO. Orange circles highlight the contribution from the substituent on aluminum to each HOMO.

On the other hand, the dihaloaluminum complexes presented only smaller structural changes between the S0 and S1 states, probably because the contribution from the Al–halogen bond to their HOMO would be smaller (Supplementary Table 17). Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis suggested that the orbital on the Al–C bond should be mainly composed of the NBO attributed to the 2p orbital of the carbon atom, which is located at the similar energy region with the HOMO of the β-diketiminate ligand (Supplementary Tables 20 and 21). As the corresponding p orbitals of chlorine, bromine, and iodine should be located at the much lower energy region because of their large electronegativity than carbon (Supplementary Tables 22 and 23), the Al–halogen bond would not strongly contribute to the HOMO of the dihaloaluminum complexes due to the weaker orbital interactions. As a result, the undesired structural relaxation causing the non-radiative quenching could hardly occur in the S1 state and the S1–S0 electronic transition would be no longer forbidden at its S1 geometry (e.g., f = 0.5070 for LAlCl, Fig. 3b). Consequently, it is suggested that the photophysical processes of β-diketiminate complexes could be drastically modulated by the substituents on the central element. In addition, it is worth noting that the electron-donating contribution from the Al–C bond destabilizes the HOMO level compared to the dihaloaluminum complexes, leading to the lower S1 state consistent with the observed redshift of the absorption band. Indeed, LAlEt, with the more strongly electron-donating ethyl group, showed the absorption band in the lowest energy region among the complexes. The stronger electron-donating ability of the ethyl groups might be responsible for the non-emissive behavior of LAlEt even in the solution at 77 K (see Supplementary Note 2).

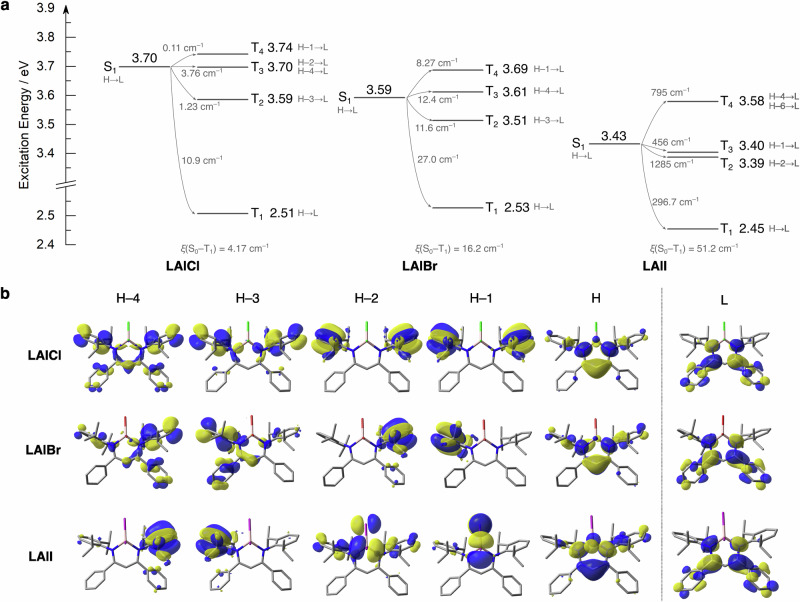

We also calculated excited triplet state (Tn) energy and spin–orbit coupling (SOC) constants between Sm and Tn states, ξ(Sm – Tn), for the dihaloaluminum complexes with the Q-Chem 5 package47 to get deeper insights into their phosphorescent properties (Fig. 4). The S1 and T1 states of each complex were dominantly characterized by the locally excited (LE) state within the central N2C3 moiety. As the S1–T1 energy gap was calculated to be about 1.0 eV or larger, the ISC from S1 to T1 seemed to be less efficient. On the other hand, the Tn (n = 2–4) states were located in the similar energy region of the S1 state (±100 meV). In addition, the SOC values were estimated to be large enough to accept the efficient ISC between S1 and Tn. For LAlCl and LAlBr, these large SOC values are attributable to the intraligand charge transfer (CT) character of these Tn states with twisted conformations between the donor (aromatic rings) and acceptor (N2C3 unit) as shown in Fig. 4b. As the transitions between the S1(LE) to the Tn(CT) occurs with the large change in orbital angular momentum derived from the twisted conformations, the electron-spin flipping is allowed with holding the angular momentum conservation48. On the other hand, the T2 and T3 states of LAlI significantly consist of the transition from the nonbonding orbitals (lone pairs) of the iodine atoms (HOMO-1 and HOMO-2) to its LUMO. Consequently, the heavy atom effect of iodine could efficiently accelerate the ISC between S1 to T2 and T3. Considered the absence of RTP from the difluoroboron complexes with iodinated β-diketiminate ligands18, the heavy atoms directly attached to the central atom should be responsible for the efficient RTP property. Importantly, it was suggested that the SOC constants not only between S1 and Tn but also between S0 and T1 significantly increased as the atomic number of the halogen atoms become larger because of the heavy atom effect. Therefore, both of ISC and phosphorescence processes should be enhanced in LAlBr and LAlI compared to LAlCl.

Fig. 4. Excited singlet and triplet states of the complexes.

a Excitation energies of singlet and triplet states relative to each S0 state. Orbital contributions to each state and SOC constants between Sm and Tn states are shown in gray texts. H and L denote HOMO and LUMO. b Kohn–Sham molecular orbital distributions (isovalue = 0.03).

Conclusion

CIE-active four-coordinated β-diketiminate aluminum(III) complexes, LAlCl, LAlBr, and LAlI were discovered. From the spectroscopic measurements and the theoretical calculations, it was strongly suggested that the 2p orbital of the carbon atom in LAlMe significantly contributed to its HOMO and induced the undesirable structural relaxation in the S1 state. As a result of the relaxation, internal conversion from S1 to S0 should occur even in the crystalline state at room temperature. The series of NBO analysis certainly proposed that more electronegative halogen substituents would not disturb the HOMO distribution of the β-diketiminate moiety, leading to suppression of the non-radiative quenching paths. Thus, the dihaloaluminum complexes exhibited efficient photoluminescence in the crystalline state at room temperature. In particular, LAlI exhibited RTP with 0.54 of the phosphorescence quantum yield as a result of the efficient heavy atom effect of iodine on the central element. Our strategy for constructing desired luminophores by modifying the substituents on the central element could be applicable not only for achieving further luminescent metal complexes but also for obtaining optoelectronic materials, reagents, and catalysts.

Methods

Characterization

1H (400 MHz) and 13C{1H} (100 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL JNM-AL400 spectrometer. In 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra, tetramethylsilane (TMS) and/or residual solvent peaks were used as an internal standard. 27Al{1H} NMR (130 MHz) spectra were recorded on a JEOL JNM-ECZ500 spectrometer and referenced to 1.1 M Al(NO3)3 in D2O (0 ppm) as an external standard. The peak in 27Al{1H} NMR spectra at around 60 ppm was attributed to the signal from an NMR tube. HRMS was performed at the Technical Support Office (Department of Synthetic Chemistry and Biological Chemistry, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University), and the HRMS spectra were obtained on a Thermo Fisher Scientific EXACTIVE spectrometer for electrospray ionization (ESI) and for direct analysis in real time (DART). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected using a Rigaku R-AXIS RAPID-F. Data were collected at 93 K with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation diffractometer and an imaging plate. Equivalent reflections were merged, and a symmetry related absorption correction was carried out with the program ABSCOR49. The structures were solved with SHELXT 201450 and refined on F2 with SHELXL51 on Yadokari-XG52 or ShelXle53. The program ORTEP-354 was used to generate the X-ray structural diagram. For crystallographic data, see Supplementary Table 1. Elemental analysis was performed at the Microanalytical Center of Kyoto University.

Photophysical measurements

UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a SHIMADZU UV-3600 spectrophotometer. Fluorescence and phosphorescence emission spectra and phosphorescence decay were measured with a HORIBA JOBIN YVON Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorometer and an Oxford Optistat DN for temperature control. Absolute photoluminescence quantum yields were measured with a Hamamatsu Photonics Quantaurus-QY Plus C13534-01 and a sample holder for low temperature, A11238-05, was used for the measurements at 77 K. Picosecond photoluminescence (PL) lifetimes were measured with the second harmonic generation of a Ti:sapphire pulsed laser (wavelength: 400 nm, pulse width: 100 fs, time resolution: 40 ps) and a streak camera (Hamamatsu Photonics C4334-01).

Materials

All reactions were performed under argon atmosphere using modified Schlenk line techniques and an MBRAUN glove box system, UNIlab, unless otherwise noted. Analytical thin layer chromatography was performed with silica gel 60 Merck F254 plates. Column chromatography was performed with Wakogel C-200 SiO2. n-BuLi (1.55 M in hexane, Kanto Chemical Co., Inc), AlMe3 (ca. 1.4 M in hexane, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.; TCI), AlEt3 (ca. 1.0 M in hexane, TCI), AlBr3 (99.999% trace metal basis, Sigma-Aldrich Co., LLC.; Aldrich), iodine (FUJIJILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation; Wako), deoxygenated toluene (Wako), and deoxygenated hexane (Wako) were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. AlCl3 (99.999% trace metal basis, Aldrich) was purified by sublimation under inert atmosphere before use. LH37 and LAlCl22 were synthesized according to the reported literatures. LAlMe35, LAlBr36, and LAlI36 were synthesized by using modified procedures of the literature for the related compounds.

Synthesis of LAlMe

AlMe3 (1.3 mL, ca. 1.4 M in hexane, 1.8 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of LH (1.0 g, 1.8 mmol) in 5 mL of toluene at 0 °C. The yellow transparent solution was stirred at 0 °C for 5 min, allowed to warm to 100 °C, and stirred for 16 h. All volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was dissolved in ca. 80 mL of hot hexane under air. After filtration with a warmed apparatus, the filtrate was slowly cooled to room temperature to give bright yellow crystals suitable for X-ray analysis (0.96 g, 87% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 7.14–7.00 (m, 10H), 6.82–6.79 (m, 6H), 5.72 (s, 1H), 3.57 (sept, 4H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 1.35 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 0.94 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), −0.22 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6): δ 170.8 (C=N), 144.4, 141.3, 139.8, 129.2, 128.8, 127.6, 127.1, 124.5, 103.2, 28.6, 26.4, 23.9, −9.98; 27Al{1H} NMR (130 MHz, C6D6): δ 148.4 (br); HRMS (ESI, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C41H51AlN2 + H+, 599.3940; found, 599.3930; analysis (calcd., found for C41H51AlN2): C (82.23, 82.38), H (8.58, 8.43), N (4.68, 4.67).

Synthesis of LAlEt

AlEt3 (0.92 mL, ca. 1.0 M in hexane, 0.92 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of LH (0.5 g, 0.92 mmol) in 5 mL of toluene at room temperature. The yellow transparent solution was allowed to warm to 100 °C, and stirred for 16 h. After filtration with a pre-warmed glass filter, the filtrate was concentrated to give a crude crystal. The product was recrystallized from hexane under air to afford a pure compound as a bright yellow crystal (0.38 g, 65% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 7.17–7.02 (m, 10H), 6.83–6.81 (m, 6H), 5.64 (s, 1H), 3.60 (sept, 4H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 1.39 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 1.37 (t, 6H, 3JH–H = 8.3 Hz), 0.95 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 0.34 (q, 4H, 3JH–H = 8.1 Hz); HRMS (ESI, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C43H55AlN2 + H+, 627.4253; found, 627.4260.

Synthesis of LAlCl

To a slurry of LH (0.50 g, 0.91 mmol) and hexane (9 mL) was added n-BuLi (1.55 M in hexane, 0.65 mL, 1.0 mmol) dropwise at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for 10 min at −78 °C, then allowed to slowly warm to r.t. and stirred for 5 h. The slurry was added to a suspension of freshly sublimed AlCl3 (0.24 g, 1.82 mmol) in hexane (5 mL) at −78 °C. The mixture was warmed to 50 °C and stirred for 19 h at the same temperature. The product was extracted with hexane then filtered with Merck Millipore 0.20 μm hydrophobic PTFE filter repeatedly. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. Analytically pure product was obtained by repeated crystallization from hexane with slow evaporation method. The crystals were collected and washed with hexane to give the spectroscopically pure and X-ray quality product (87 mg, 18% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 7.08–6.99 (m, 10H), 6.81–6.74 (m, 6H, Ar), 5.84 (s, 1H), 3.65 (sept, 4H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 1.47 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 0.94 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 172.2, 144.6, 138.1, 137.9, 129.5, 129.0, 127.7, 127.6, 124.4, 103.6, 28.7, 26.1, 23.6; 27Al{1H} NMR (130 MHz, C6D6): δ 100.7; HRMS (DART, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C39H45AlCl2N2 + H+, 639.2848; found, 639.2828; analysis (calcd., found for C39H45AlCl2N2): C (73.23, 73.27), H (7.09, 7.19), N (4.38, 4.33), Cl (11.08, 10.78).

Synthesis of LAlBr

To a slurry of LH (0.50 g, 0.91 mmol) and hexane (9 mL) was added n-BuLi (1.55 M in hexane, 0.65 mL, 1.0 mmol) dropwise at −78 °C. The mixture was stirred for 10 min at −78 °C, then allowed to slowly warm to r.t. and stirred for 5 h. The yellow slurry was concentrated under reduced pressure. The yellow powder was washed with hexane and dried under reduced pressure to give the solid of the lithium complex (0.50 mg, 99%). To a precooled solution of the lithium complex (0.29 g, 0.53 mmol) in toluene (6 mL) was added a suspension of AlBr3 (0.14 g, 0.53 mmol) dropwise at −78 °C. The mixture was allowed to slowly warm to r.t. and stirred for 14 h. The turbid orange solution was filtered with a Merck Millipore 0.20 μm hydrophobic PTFE filter. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. Analytically pure product was obtained by repeated crystallization from mixed solvent of toluene and hexane (ca. 1/10, vol/vol). The crystals were collected and washed with hexane to give the spectroscopically pure and X-ray quality product (0.13 g, 33%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 7.08–7.00 (m, 10H), 6.79–6.73 (m, 6H), 5.90 (s, 1H), 3.72 (sept, 4H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz), 1.47 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.6 Hz), 0.92 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.7 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6): δ 172.7, 145.0, 138.9, 138.4, 129.6, 129.2, 128.3, 127.8, 124.9, 104.9, 29.2, 26.9, 23.8; HRMS (DART, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C39H45AlBr2N2 + H+, 727.1838; found, 727.1831; [M–Br]+ calcd. for C39H45AlBrN2+, 647.2576; found, 647.2570.

Synthesis of LAlI

To a solution of LAlMe (1.5 g, 2.5 mmol) in toluene (65 mL) was added a solution of I2 (1.6 g, 6.3 mmol) in toluene (14 mL) dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was allowed to slowly warm to r.t. and stirred for 3 days. The dark red solution was filtered with a Merck Millipore 0.20 μm hydrophobic PTFE filter. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. Analytically pure product was obtained by repeated crystallization from mixed solvent of toluene and hexane. The yellow crystals were collected and washed with hexane to give the spectroscopically pure and X-ray quality product (0.82 g, 40% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 7.08–7.00 (m, 10H), 6.77–6.75 (m, 6H), 6.02 (s, 1H), 3.78 (br, 4H), 1.47 (d, 12H, 3JH–H = 6.6 Hz), 0.90 (br, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, C6D6): δ 172.8, 145.1, 139.2, 138.5, 129.6, 129.1, 128.5, 128.4, 127.8, 125.0, 105.9, 29.5, 23.7; HRMS (DART, m/z): [M + H]+ calcd. for C39H45AlI2N2 + H+, 823.1544; found, 823.1560.

Theoretical calculations

All calculations were carried out using Gaussian 16 Revision C.03 at the (TD-)CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) and (TD-)CAM-B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) levels of theory for geometry optimizations and for time-dependent single-point calculations, respectively. All optimized structures were confirmed to be at local minimum using frequency calculations. The crystal structures were employed as the initial geometries of the optimizations at S0 states. The initial geometries for the optimization at S1 states were the corresponding optimized structures at the S0 states. Calculated low frequencies are listed in Supplementary Tables 7–14. Molecular orbital components which have large absolute values of orbital coefficients are shown in Supplementary Tables 15–18. Supplementary Table 19 shows the calculated frontier orbital energies and the electronic transitions for LAlMe and LAlCl. NBO analyses were carried out using the CAM-B3LYP functional and the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set. In the case of the calculations using the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set, the corresponding NBOs could not be saved in the checkpoint files due to the large number of basis functions (1333 for LAlMe and 1307 for LAlCl). Selected natural atomic orbital occupancies and NBO coefficients are listed in Supplementary Tables 20–23.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Computation time was provided by the SuperComputer System, Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University. We thank Y. Okabayashi (AIST) for his support on time-resolved PL measurements. This work was partially supported by The Asahi Glass Foundation and a Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (for S.I., JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 21K14673 and 23K13793) and for Scientific Research (B) (for K.T., JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24K01570).

Author contributions

S.I. performed the synthesis and characterization of all compounds, the photophysical measurements, and the theoretical calculations. T.H. performed the time-resolved PL measurements. K.T. and Y.C. supervised the research. All authors discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Hiroki Iwanaga and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials of this article. All NMR spectra are provided as Supplementary Data 1–15. DFT-optimized geometries at S0 and S1 states of the compounds are provided as Supplementary Data 16. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1880035 for LAlCl, 1880036 for LAlMe, 2364980 for LAlBr, and 2364981 for LAlI. These data can be obtained free of charge from The CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The cif files are also provided as Supplementary Data 17–20.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-024-01295-z.

References

- 1.Tang, C. W. & VanSlyke, S. A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett.51, 913–915 (1987). 10.1063/1.98799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang, S. Luminescence and electroluminescence of Al(III), B(III), Be(II) and Zn(II) complexes with nitrogen donors. Coord. Chem. Rev.215, 79–98 (2001). 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00403-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao, S.-B. & Wang, S. Luminescence and reactivity of 7-azaindole derivatives and complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev.39, 3142–3156 (2010). 10.1039/c001897j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl, R. & Anzenbacher, P. Emission color tuning in AlQ3 complexes with extended conjugated chromophores. Org. Lett.5, 2769–2772 (2003). 10.1021/ol034693a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang, K., Kim, H., Lee, Y., Lee, M. & Do, Y. Synthesis and properties of salen–aluminum complexes as a novel class of color‐tunable luminophores. Chem. Eur. J.15, 6478–6487 (2009). 10.1002/chem.200900137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ono, T. et al. Dinuclear triple-stranded helicates composed of tetradentate ligands with aluminum(III) chromophores: optical resolution and multi-color circularly polarized luminescence properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 2614–2618 (2021). 10.1002/anie.202011450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui, C. et al. Synthesis and structure of a monomeric aluminum(I) compound [{HC(CMeNAr)2}Al] (Ar=2,6-iPr2C6H3): a stable aluminum analogue of a carbene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.39, 4274–4276 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roesky, H. W. & Kumar, S. S. Chemistry of aluminium(I). Chem. Commun. 4027 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nagendran, S. & Roesky, H. W. The chemistry of aluminum(I), silicon(II), and germanium(II). Organometallics27, 457–492 (2008). 10.1021/om7007869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu, T. & Nikonov, G. I. Oxidative addition and reductive elimination at main-group element centers. Chem. Rev.118, 3608–3680 (2018). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakewell, C., White, A. J. P. & Crimmin, M. R. Reactions of fluoroalkenes with an aluminium(I) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 6638–6642 (2018). 10.1002/anie.201802321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourget-Merle, L., Lappert, M. F. & Severn, J. R. The chemistry of β-diketiminatometal complexes. Chem. Rev.102, 3031–3066 (2002). 10.1021/cr010424r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, C., Bellows, S. M. & Holland, P. L. Tuning steric and electronic effects in transition-metal β-diketiminate complexes. Dalton Trans.44, 16654–16670 (2015). 10.1039/C5DT02215K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macedo, F. P., Gwengo, C., Lindeman, S. V., Smith, M. D. & Gardinier, J. R. β‐Diketonate, β‐ketoiminate, and β‐diiminate complexes of difluoroboron. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2008, 3200–3211 (2008). 10.1002/ejic.200800243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshii, R., Hirose, A., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Boron diiminate with aggregation‐induced emission and crystallization-induced emission-enhancement characteristics. Chem. Eur. J.20, 8320–8324 (2014). 10.1002/chem.201402946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshii, R., Hirose, A., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Functionalization of boron diiminates with unique optical properties: multicolor tuning of crystallization-induced emission and introduction into the main chain of conjugated polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc.136, 18131–18139 (2014). 10.1021/ja510985v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, S., Hirose, A., Yamaguchi, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Size-discrimination of volatile organic compounds utilizing gallium diiminate by luminescent chromism of crystallization-induced emission via encapsulation-triggered crystal–crystal transition. J. Mater. Chem. C4, 5564–5571 (2016). 10.1039/C6TC01819J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi, M., Ito, S., Hirose, A., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Modulation of sensitivity to mechanical stimulus in mechanofluorochromic properties by altering substituent positions in solid-state emissive diiodo boron diiminates. J. Mater. Chem. C4, 5314–5319 (2016). 10.1039/C6TC01111J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, S., Hirose, A., Yamaguchi, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Synthesis of aggregation-induced emission-active conjugated polymers composed of group 13 diiminate complexes with tunable energy levels via alteration of central element. Polymers9, 68 (2017). 10.3390/polym9020068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi, M., Ito, S., Hirose, A., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Luminescent color tuning with polymer films composed of boron diiminate conjugated copolymers by changing the connection points to comonomers. Polym. Chem.9, 1942–1946 (2018). 10.1039/C8PY00283E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito, S., Yaegashi, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Reversible vapochromic luminescence accompanied by planar half-chair conformational change of a propeller-shaped boron β-diketiminate complex. Chem. Eur. J.27, 9302–9312 (2021). 10.1002/chem.202101107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito, S., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Effects of a central element on photoluminescence properties of β-diketiminate complexes composed of the group 13 elements. Dalton Trans. 10.1039/d4dt01689k (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hong, Y., Lam, J. W. Y. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev.40, 5361–5388 (2011). 10.1039/c1cs15113d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mei, J., Leung, N. L. C., Kwok, R. T. K., Lam, J. W. Y. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: together we shine, united we soar! Chem. Rev.115, 11718–11940 (2015). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi, Z. et al. Recent advances in organic mechanofluorochromic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev.41, 3878–3896 (2012). 10.1039/c2cs35016e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito, S. et al. Highly efficient luminescence from boron β-dialdiminates and their π-conjugated polymers in both solutions and solids: significant impact of the substituent position on luminescence behavior. Mater. Chem. Front.7, 4971–4983 (2023). 10.1039/D3QM00761H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, G. et al. Multi-emissive difluoroboron dibenzoylmethane polylactide exhibiting intense fluorescence and oxygen-sensitive room-temperature phosphorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc.129, 8942–8943 (2007). 10.1021/ja0720255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, G., Lu, J., Sabat, M. & Fraser, C. L. Polymorphism and reversible mechanochromic luminescence for solid-state difluoroboron avobenzone. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 2160–2162 (2010). 10.1021/ja9097719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito, H. et al. Reversible mechanochromic luminescence of [(C6F5Au)2(μ-1,4-diisocyanobenzene). J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 10044–10045 (2008). 10.1021/ja8019356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao, D. et al. Regiospecific N‐heteroarylation of amidines for full-color-tunable boron difluoride dyes with mechanochromic luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 13676–13680 (2013). 10.1002/anie.201304824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, L. et al. luminescent chromism of boron diketonate crystals: distinct responses to different stresses. Adv. Mater.27, 2918–2922 (2015). 10.1002/adma.201500589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirai, Y. et al. Triboluminescence of lanthanide coordination polymers with face-to-face arranged substituents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.56, 7171–7175 (2017). 10.1002/anie.201703638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gon, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Recent progress in the development of advanced element-block materials. Polym. J.50, 109–126 (2018). 10.1038/pj.2017.56 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gon, M., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Creative synthesis of organic–inorganic molecular hybrid materials. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn.90, 463–474 (2017). 10.1246/bcsj.20170005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian, B., Ward, D. L. & Smith, M. R. Synthesis, structure, and reactivity of β-diketiminato aluminum complexes. Organometallics17, 3070–3076 (1998). 10.1021/om970886o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stender, M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of HC{C(Me)N(C6H3-2,6-i-Pr2)}2MX2 (M = Al, X = Cl, I; M = Ga, In, X = Me, Cl, I): sterically encumbered β-diketiminate group 13 metal derivatives. Inorg. Chem.40, 2794–2799 (2001). 10.1021/ic001311d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrowsmith, M., Crimmin, M. R., Hill, M. S. & Kociok-Köhn, G. Beryllium derivatives of a phenyl-substituted β-diketiminate: a well-defined ring opening reaction of tetrahydrofuran. Dalton Trans.42, 9720–9726 (2013). 10.1039/c3dt51021b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakthavachalam, K. & Reddy, D. N. Synthesis of aluminum complexes of triaza framework ligands and their catalytic activity toward polymerization of ε-caprolactone. Organometallics32, 3174–3184 (2013). 10.1021/om3011432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stender, M. et al. The synthesis and structure of lithium derivatives of the sterically encumbered β-diketiminate ligand [{(2,6-Pri2H3C6)N(CH3)C}2CH]−, and a modified synthesis of the aminoimine precursor. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 3465–3469 (2001).

- 40.Ito, S., Tanaka, K. & Chujo, Y. Characterization and photophysical properties of a luminescent aluminum hydride complex supported by a β-diketiminate ligand. Inorganics7, 100 (2019). 10.3390/inorganics7080100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aoyama, Y., Sakai, Y., Ito, S. & Tanaka, K. Effects of central elements on the properties of group 13 dialdiminate complexes. Chem. Eur. J.29, e202300654 (2023). 10.1002/chem.202300654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01. (2016). http://gaussian.com/

- 43.Inoue, S. & Takeda, N. Reaction of carbon dioxide with tetraphenylporphinatoaluminium ethyl in visible light. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn.50, 984–986 (1977).

- 44.Murayama, H., Inoue, S. & Ohkatsu, Y. Photochemical activation of metal–carbon bond in zinc and aluminium porphyrins. Substitution reaction with hindered phenols. Chem. Lett.12, 381–384 (1983).

- 45.Hirai, Y., Murayama, H., Aida, T. & Inoue, S. Activation of a metal axial ligand bond in aluminum porphyrin by visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc.110, 7387–7390 (1988).

- 46.Komatsu, M., Aida, T. & Inoue, S. Novel visible-light-driven catalytic carbon dioxide fixation. Synthesis of malonic acid derivatives from CO2 an αβ-unsaturated ester or nitrile and diethylzinc catalyzed by aluminum porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.113, 8492–8498 (1991).

- 47.Shao, Y. et al. Advances in molecular quantum chemistry contained in the Q-Chem 4 program package. Mol. Phys.113, 184–215 (2015). 10.1080/00268976.2014.952696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shao, W. & Kim, J. Metal-free organic phosphors toward fast and efficient room-temperature phosphorescence. Acc. Chem. Res.55, 1573–1585 (2022). 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higashi, T. ABSCOR. Program for Absorption Correction (Rigaku Corporation, 1995).

- 50.Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT—integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A71, 3–8 (2015). 10.1107/S2053273314026370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C71, 3–8 (2015). 10.1107/S2053229614024218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kabuto, C., Akine, S., Nemoto, T. & Kwon, E. Release of software (Yadokari-XG 2009) for crystal structure analyses. J. Cryst. Soc. Jpn.51, 218–224 (2009).

- 53.Hübschle, C. B., Sheldrick, G. M. & Dittrich, B. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr.44, 1281–1284 (2011). 10.1107/S0021889811043202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farrugia, L. J. ORTEP-3 for Windows—a version of ORTEP-III with a graphical user interface (GUI). J. Appl. Crystallogr.30, 565–565 (1997). 10.1107/S0021889897003117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials of this article. All NMR spectra are provided as Supplementary Data 1–15. DFT-optimized geometries at S0 and S1 states of the compounds are provided as Supplementary Data 16. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1880035 for LAlCl, 1880036 for LAlMe, 2364980 for LAlBr, and 2364981 for LAlI. These data can be obtained free of charge from The CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The cif files are also provided as Supplementary Data 17–20.