Abstract

Objective This S2k guideline of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) and the German Society of Perinatal Medicine (DGPM) contains consensus-based recommendations for the care and treatment of pregnant women, parturient women, women who have recently given birth, and breastfeeding women with SARS-CoV-2 infection and their newborn infants. The aim of the guideline is to provide recommendations for action in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic for professionals caring for the above-listed groups of people.

Methods The PICO format was used to develop specific questions. A systematic targeted search of the literature was carried out using PubMed, and previously formulated statements and recommendations issued by the DGGG and the DGPM were used to summarize the evidence. This guideline also drew on research data from the CRONOS registry. As the data basis was insufficient for a purely evidence-based guideline, the guideline was compiled using an S2k-level consensus-based process. After summarizing and presenting the available data, the guideline authors drafted recommendations in response to the formulated PICO questions, which were then discussed and voted on.

Recommendations Recommendations on hygiene measures, prevention measures and care during pregnancy, delivery, the puerperium and while breastfeeding were prepared. They also included aspects relating to the monitoring of mother and child during and after infection with COVID-19, indications for thrombosis prophylaxis, caring for women with COVID-19 while they are giving birth, the presence of birth companions, postnatal care, and testing and monitoring the neonate during rooming-in or on the pediatric ward.

Key words: coronavirus, COVID-19, obstetrics, neonatology, midwifery

I Guideline Information

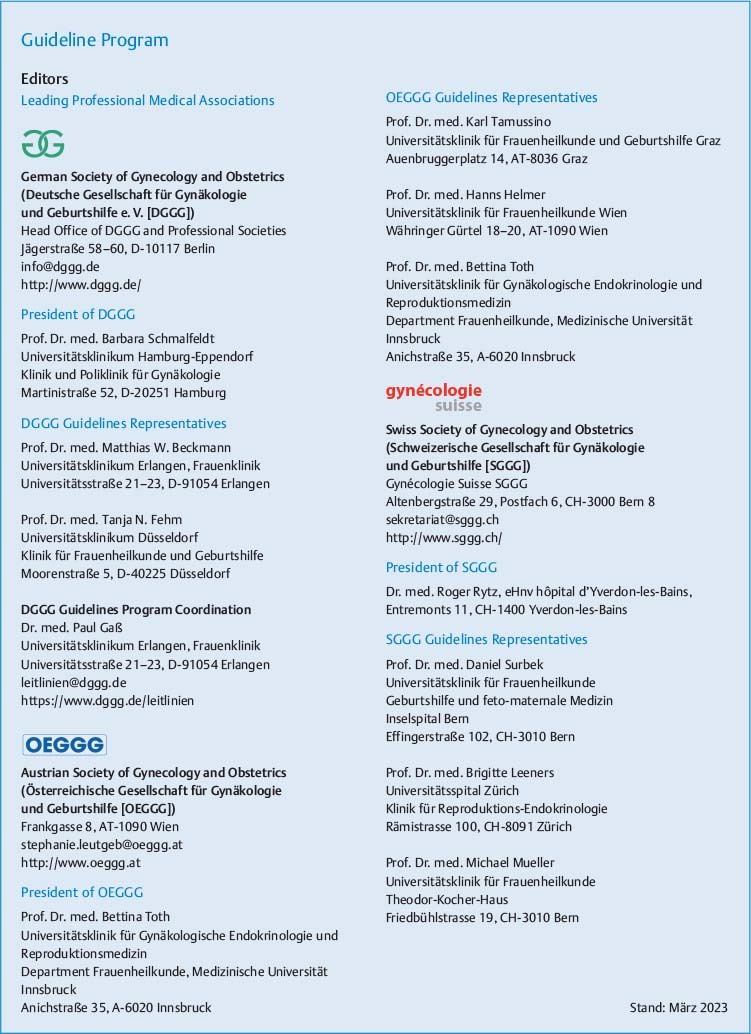

Guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information on the guidelines program, please refer to the end of the guideline.

Citation format

SARS-CoV-2 in Pregnancy, Birth and Puerperium. Guideline of the DGGG and DGPM (S2k-Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/092, March 2022). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2023. doi:10.1055/a-2003-5983

Guideline documents

The complete long version of this guideline in German as well as a list of the conflicts of interest of all the authors is available on the the homepage of the AWMF: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/015-092.html

Guideline authors

Table 1 Lead and/or coordinating guideline author.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| Prof. Dr. Ulrich Pecks | German Society of Perinatal Medicine, DGPM |

| Prof. Dr. Frank Louwen | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics/Working Group for Obstetrics and Prenatal Medicine, DGGG/AGG |

Table 2 Contributing guideline authors.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group (AG)/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organization/association |

|---|---|

| * These persons contributed significantly to the development of the guideline. They did not vote on recommendations or statements. | |

| Lena Agel | German Society of Midwifery Science, DGHWi |

| Dr. Klaus J. Doubek | Professional Association of Gynecologists, BVF |

| Dr. Carsten Hagenbeck | German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics/Working Group for Obstetrics and Prenatal Medicine, DGGG/AGG |

| Prof. Dr. Constantin von Kaisenberg | German Society of Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology, DEGUM |

| Prof. Dr. Peter Kranke | German Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, DGAI |

| Sabine Leitner | Professional Association “The preterm infant” [Bundesverband „Das frühgeborene Kind“] |

| Dr. Nadine Mand | Society for Neonatology and Pediatric Intensive Care Medicine, GNPI |

| Prof. Dr. Mario Rüdiger | German Society of Perinatal Medicine, DGPM |

| Dr. Janine Zöllkau | German Society for Prenatal and Obstetric Medicine, DGPGM |

| Dr. Lukas Jennewein* | Frankfurt University Hospital |

| Nina Mingers* | Schleswig-Holstein University Hospital |

| Magdalena Sitter* | Würzburg University Hospital |

The following professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations stated that they wished to contribute to the guideline text and participate in the consensus conference and nominated representatives to contribute and attend the conference ( Table 2 ).

Neutral moderation of the guideline was provided by Prof. Dr. Constantin von Kaisenberg (certified AWMF-guidelines consultant).

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- aPPT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CCP

clinical consensus point

- CGP

good clinical practice

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CT

computed tomography

- CTG

cardiotocography

- EC

expert consensus

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- FFP

filtering facepiece

- FGR

fetal growth restriction

- FTS

first trimester screening

- IM

intramuscular

- IV

intravenous

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LMWH

low molecular weight heparin

- MEOWS

modified early obstetric warning score

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RKI

Robert Koch Institute

- RT-PCR

real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SpO 2

oxygen saturation

- STIKO

ständige Impfkommission/Standing Committee on Vaccination at the RKI

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

- WHO

World Health Organization

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The purpose of this guideline is to provide recommendations for action with regards to the care of pregnant women, parturient women, women who have recently given birth, and breastfeeding women and their newborn infants during and after infection with SARS-CoV-2 while also considering the available evidence (which was limited, due to the newness of the virus) as well as own data from the CRONOS registry.

Targeted areas of care

Inpatient care

Outpatient care

Target user groups/target audience

This guideline aims to provide all persons involved in the care of pregnant women, parturient women, women who have recently given birth, and breastfeeding women with SARS-CoV-2 infection with recommendations for action. The guideline is aimed at:

gynecologists/obstetricians

pediatricians/neonatologists (m/w/d)

anesthesiologists

midwives

nurses and orderlies working in maternity wards and pediatric wards caring for newborn babies

Adoption and period of validity

The validity of this guideline was confirmed by the executive boards/representatives of the participating medical professional societies/working groups/organizations/associations as well as by the board of the DGGG and the DGPM as well as by their Guidelines Commissions in March 2022 and was thereby approved in its entirety. This guideline is valid from 1 March 2022 through to 31 March 2025. Because of the contents of this guideline, this period of validity is only an estimate. The guideline can be reviewed and updated earlier if necessary. If the guideline still reflects the current state of knowledge, its period of validity can be extended.

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2), and highest (S3) class. The lowest class is defined as consisting of a set of recommendations for action compiled by a non-representative group of experts. In 2004, the S2 class was divided into two subclasses: a systematic evidence-based subclass (S2e) and a structural consensus-based subclass (S2k). The highest S3 class combines both approaches.

This guideline was classified as: S2k

Grading of recommendations

The grading of evidence based on the systematic search, selection, evaluation, and synthesis of an evidence base which is then used to grade the recommendations is not envisaged for S2k guidelines. Individual statements and recommendations are only differentiated by syntax, not by symbols ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Grading of recommendations (based on Lomotan et al., Qual Saf Health Care 2010).

| Description of binding character | Expression |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation with highly binding character | must/must not |

| Regular recommendation with moderately binding character | should/should not |

| Open recommendation with limited binding character | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions or explanations of specific facts, circumstances, or problems without any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “statements.” It is not possible to provide any information about the level of evidence for these statements.

Achieving consensus and level of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level), authorized participants attending the session vote on draft statements and recommendations. The process is as follows. A recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus (> 75% of votes) is not achieved, there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined, based on the number of participants ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Level of consensus based on extent of agreement.

| Symbol | Level of consensus | Extent of agreement in percent |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

The term “expert consensus” is used to characterize consensus decisions specifically relating to recommendations/statements issued without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or where evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terms used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter Grading of recommendations but without the use of symbols; it is only expressed semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”).

IV Guideline

1 General comments on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

With new virus variants emerging and the infections coming in waves, the dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic are not foreseeable. It can be assumed that COVID-19, the disease triggered by SARS-CoV-2, will remain challenging even after the pandemic, whether the disease continues in its current form or similar. In addition to the recommendations for pregnant women, parturient women, women who have recently given birth, and neonates provided in this guideline, it is important to be aware of additional sources reporting on the treatment of affected persons and the management of infection which include the latest findings.

The following sources should be of particular interest (please note that most of these sources are in German):

Recommendations of the RKI on hygiene measures in the context of treating and caring for patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Hygiene.html

Extended hygiene measures used in the German healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/erweiterte_Hygiene.html

-

The German law on preventing and combating infectious diseases in humans (Infection Protection Law, Infektionsschutzgesetz – IfSG): https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ifsg/index.html#BJNR104510000BJNE002305116

Sec. 28a Special protection measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19)

Sec. 28b Uniform protection measures used across all of Germany to prevent the spread of the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) in special occurrences of infection, the power to issue statutory instruments

Sec. 28c Power to issue statutory special regulations for vaccinated, tested and comparable persons

The German-language S2e-guideline with the AWMF registry no. 053-054: “SARS-CoV-2/Covid-19 Information & Practical Help for General Practitioners in Private Practice” 1 .

The German-language S3-guideline with the AWMF registry no. 113/001: “Recommendations for the Inpatient Treatment of Patients with COVID-19” 2 .

The authors have attempted to keep this guideline as short and readable as possible. The evidence pertaining to some aspects or parts of the guideline is therefore discussed and summarized in more detail in the “Recommendations on SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 in Pregnancy, Birth and Puerperium – Update November 2021” prepared by the DGGG and DGPM 3 . This information is also available on the website of the DGGG and the DGPM together with the latest, regularly published recommendations and statements which take account of the current state of the pandemic and include new findings.

Responsibility for ensuring that the load on the healthcare system is balanced

During the pandemic, the specific healthcare structures of the federal states had to be coordinated. Many of the federal states in Germany envisaged a decentralized treatment structure to deal with persons who were SARS-CoV-2-positive or who developed COVID-19 to make optimum use of the resources of the healthcare system. When considering the care of obstetric patients, the guideline authors are of the opinion that obstetric criteria used when deciding whether patients need to be treated in hospital and the care level available at the center treating them are already sufficient to deal with the issue 4 , 5 . There are no indications that a pregnant woman with only (asymptomatic or mild) SARS-CoV-2 infection needs to be transferred to a special center of maximum care with a neonatal intensive care unit. It is the responsibility of every outpatient and inpatient care facility to care for patients who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and adapt their care structures accordingly.

2 Prevention of infection

Pregnant women have a higher risk of COVID-19 taking a more severe course compared to non-pregnant women of the same age. When attempting to prevent infection, the primary challenge is how to deal with asymptomatic infected women who attend hospital appointments. This means that obstetric and neonatology departments constitute a particularly sensitive area in healthcare facilities, and measures must be agreed upon, based on interdisciplinary and interprofessional cooperation, which will protect fellow patients and the staff treating them. In addition to ensuring that rooms are adequately aired and ventilated and that general hygiene measures such as disinfecting hands are in place, the wearing of a FFP by the staff and patients and screening for infectious agents are effective measures which can protect all involved contact persons 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 . The birth-specific aspects in clinical settings, which are important in a pandemic, are described below.

2.1 Wearing a filtering facepiece (FFP)

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| An FFP must be worn when visiting a hospital. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If the test result was negative and the woman giving birth has no typical clinical symptoms of COVID-19, she must be allowed not to wear an FFP. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If the test results have not yet come back or the woman has tested positive or has typical COVID-19 symptoms, the parturient woman must wear an FFP. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The medical staff present at the birth and other persons present should wear an FFP. | |

Effect of wearing an FFP on transmission of the virus

It was found that wearing an FFP significantly reduced the risk of transmission 8 . Medical and hospital staff wearing an FFP (OR 0.11; 95% CI: 0.03 – 0.39; p < 0,001), wearing gloves (OR 0.39; 95% CI: 0.29 – 0.53; p < 0.001), and wearing medical scrubs (OR 0.59; 95% CI: 0.48 – 0.73; p < 0.001) reduced the transmission rate 9 . According to a study carried out in the USA, if a case-patient and a contact both wore an FFP, the transmission rate was reduced even further (from 25.6% to 12.5%) 10 . A German scenario study modelled the effect of different protection measures to prevent the transmission of infection to medical staff when caring for parturient women. According to the study, if a highly infectious patient wore an FFP2 mask, the risk of infection for the midwife decreased from 30% to 7%. Additional active ventilation of the room further reduced the risk to 0.7%. If the woman giving birth wore an FFP, the risk decreased even more to 0.3% 11 . The guideline authors are of the opinion that the birthing process, especially the expulsion phase, is an aerosol-forming situation which results in relevant exposure and therefore involves a relevant risk of transmission to the medical staff providing the care.

2.2 Testing and screening for SARS-CoV-2

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| During the pandemic, each female patient must be asked about symptoms and her history of SARS-CoV-2 infection risks prior to receiving treatment in a healthcare facility (whether as an outpatient or an inpatient). | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Diagnostic testing must be carried out if there is a clinical suspicion consistent with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) based on the patientʼs medical history, symptoms, or findings, irrespective of the patientʼs vaccination status. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Screening for SARS-CoV-2 must be carried out prior to every admission to hospital or admission for the birth, in accordance with the recommendations of the RKI and the national testing strategy as well as any directives issued by federal states. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 2.E8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The results of a SARS-CoV-2 test should be available prior to admission for any elective procedure, e.g., for a planned caesarean section, cerclage, or induction of labor. | |

National testing strategy

The RKI regularly publishes updates of the national testing strategy, which must be complied with in healthcare facilities during the pandemic: “Testing in inpatient or outpatient facilities is basically indicated if there is a clinical suspicion consistent with a SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) based on the patientʼs history, symptoms or findings.” It is also recommended that “patients should in principle be tested prior to (re-) admission as well as prior to any outpatient procedures […] with a nose-and-throat swab and a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. […] The threshold for indicating a diagnostic workup should be low and depends on the epidemic situation.” (As at 1.11.2021) 12

Special aspects affecting facilities caring for pregnant women

From the perspective of preventing infection, facilities which care for pregnant women, parturient women, and their newborn infants are a particularly sensitive issue. As the women are young and healthy and sometimes asymptomatically infected, identifying them is important as this allows measures to be taken to protect the staff, fellow patients, and their families. A nosocomial infection acquired from a fellow patient in hospital which then requires a form of quarantine will complicate the infected patientʼs access to follow-up medical care from midwives and medical practices. Although the disease may often be asymptomatic, pregnant women, particularly in the second half of their pregnancy, have a higher risk of suffering a more severe course of COVID-19 13 and therefore require special protection.

Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy

Pregnant women do not have a higher risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2. Screening has confirmed that the prevalence of infection is similar to that of the general population with regards to its regional and temporal course 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 . However, there are indications that some groups of female patients have a higher risk of infection based on their ethnicity 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 or socio-economic status 31 , 32 . A population-based British cohort study (3527 SARS-CoV-2 infections in 342 080 pregnant women) showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred more often in women who were younger and were primipara, belonged to a non-white ethnic group, lived in disadvantaged areas, or had comorbidities 33 . Moreover, the prevalence of infection appeared to increase as the gestational age increased 34 , 35 . In hospital registries, the number of infected pregnant women in their 3rd trimester pregnancy dominated, constituting 83% (UKOSS) or 64.3% (CRONOS) of all registered infected pregnant women 36 , 37 .

Symptomatic versus asymptomatic female patients

According to studies from New York, London, and Connecticut, the overwhelming (up to 89%) percentage of women who tested positive on admission to hospital to give birth were asymptomatic 38 – 40 . In Great Britain, out of 1148 pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection cared for between March and August 2020 the percentage of asymptomatic patients was 37% 36 . This corresponds to the data obtained from German hospitals included in the CRONOS registry up until 1st October 2020, which recorded 37% of women as asymptomatic 37 .

CRONOS (as at 24th August 2021): Of the 785 women with known infection around the time of their due date from week 37 + 0 of gestation, the rate of asymptomatic women was 55.6% (437/785; no information about symptoms for 23 women). The circumstances of the positive SARS-CoV-2 tests were recorded for 657 women. Of the 354 asymptomatic women, 306 (86.4%) were identified by screening carried out at the hospital.

3 Monitoring of infected pregnant women

3.1 General obstetric and gynecological care

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E9 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The care of a pregnant woman infected with SARS-CoV-2 should not deviate from obstetric standards and the specifications in the German Maternity Guidelines. | |

| Consensus-based statement 3.S1 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| When planning elective prenatal appointments and examinations it is important to consider whether they could be postponed until the pregnant woman no longer needs to isolate/is no longer contagious. | |

3.2 Symptom-based care

3.2.1 Pregnant women who are asymptomatic or have only mild symptoms

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E10 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| A pregnant woman who is infected but asymptomatic or has only mild symptoms must be cared for in accordance with the recommended standards given elsewhere in the guidelines for non-pregnant women. The risk of acute decompensation must be emphasized. | |

Note: We would like to explicitly refer to the recommendations of the S2e-guideline “SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Information & Practical Help for General Practitioners in Private Practice” (as at 02/2022) 1 .

3.2.2 Moderately ill pregnant women

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E11 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If a pregnant woman has symptoms which clearly have a negative impact on her general condition and/or is a higher risk patient in addition to her pregnancy (this particularly applies to unvaccinated pregnant women and pregnant women with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, or chronic lung disease), it must be established whether admission to hospital is indicated. | |

Note: We would like to explicitly refer to the recommendations of the S2e-guideline “SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Information & Practical Help for General Practitioners in Private Practice” (as at 02/2022) 1 .

3.2.3 Severely ill pregnant women

| Consensus-based statement 3.S2 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| When treating a patient in hospital for COVID-19 who is pregnant or has recently given birth, treatment should follow the S3-guideline “Recommendations for the Inpatient Treatment of Patients with COVID-19” and additionally focus on the obstetric aspects. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E12 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If admitted to hospital , the patientʼs vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation) must be measured. In addition to taking the patientʼs vital signs, laboratory and urine diagnostics must also be carried out. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E13 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The initial laboratory workup should include the following parameters which need to be checked regularly as necessary: differential blood count, CRP, LDH, AST/ALT, creatinine as well as D-dimer, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen and urine diagnostics (proteinuria/albuminuria, hematuria, leukocyturia). | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E14 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Imaging must be carried out if the patient presents with respiratory insufficiency or there is a suspicion of pulmonary embolism. This may require the use of procedures employing ionizing radiation (e.g., X-rays/CT). | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E15 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Measurement of vital signs and oxygen saturation must be carried out and the patient must be regularly checked to see whether admission to an intensive care unit is indicated. For patients with COVID-19 and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, the goal is to ensure adequate oxygenation. The aim must be to achieve SpO 2 ≥ 94%. | |

Outpatient treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19

Admission to hospital for monitoring is recommended if symptoms worsen, the patient reports subjective worsening, or vital signs are abnormal. The Modified Early Obstetric Warning Score MEOWS or a similar emergency-care scoring system can be a useful instrument for an objective evaluation and to provide recommendations for action ( Table 5 ). There are no published empirical data for COVID-19.

Table 5 Modified Early Obstetric Warning Score (MEOWS), taken from 41 .

| MEOW score | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MEOWS 0 – 1:

normal

MEOWS 2 – 3: stable , report findings to healthcare provider the same day MEOWS 4 – 5: unstable , urgent evaluation by medical doctor MEOWS ≥ 6: critical , immediate emergency care | |||||||

| SpO 2 (%) | ≤ 85 | 86 – 89 | 90 – 95 | ≥ 96 | |||

| Respiratory rate (/min) | < 10 | 10 – 14 | 15 – 20 | 21 – 29 | ≥ 30 | ||

| Pulse (/min) | < 40 | 41 – 50 | 51 – 100 | 101 – 110 | 110 – 129 | ≥ 130 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ≤ 70 | 71 – 80 | 81 – 100 | 101 – 139 | 140 – 149 | 150 – 159 | ≥ 160 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | ≤ 49 | 50 – 89 | 90 – 99 | 100 – 109 | ≥ 110 | ||

| Diuresis (mL/h) | 0 | ≤ 20 | ≤ 35 | 35 – 200 | ≥ 200 | ||

| Central nervous system | agitated | awake | responds to verbal stimuli | responds to pain | no response | ||

| Temperature (°C) | ≤ 35 | 35 – 36 | 36 – 37.4 | 37.5 – 38.4 | ≥ 38.5 | ||

3.3 Peripartum monitoring of infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 3.E16 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Constant monitoring must be carried out during the birth if the pregnant woman is infected with SARS-CoV-2 and must include the measurement of oxygen saturation, with the aim of achieving SpO 2 ≥ 94%. For further details, readers are explicitly referred to the recommendations in Chapter 5 “Giving Birth”. | |

For the peripartum monitoring of a pregnancy, please refer to the recommendations on giving birth and obstetric management in Chapter 5 “Giving birth when positive for COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2”.

3.4 Care after SARS-CoV-2 infection

For subsequent monitoring of the pregnancy after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, please refer to Chapter 4.3 “Care in pregnancy after SARS-CoV-2 infection”.

For the post-COVID period, please refer to the relevant S1-guideline “Post-COVID/Long COVID” (AWMF registry No. 020/027) 42 .

4 Monitoring the fetus

4.1 General monitoring during maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E17 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| In cases with maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection, fetal monitoring must adhere to current national guidelines and take account of the guidelines issued by professional medical societies on the use of ultrasound, Doppler and CTG, and biochemical analysis. | |

Monitoring the pregnancy and the fetus of mothers with (acute) SARS-CoV-2 infection is done in accordance with general guidelines and medical guidelines and is based on the respective week of gestation 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 . Setting up outpatient infection clinics in doctorʼs offices may make it easier to implement guideline recommendations 49 . Currently valid prenatal diagnostic methods which comply with these standards should additionally be available 43 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 . When planning elective examinations, postponing these examinations until the pregnant woman no longer needs to isolate/is no longer contagious should be considered. The decision must be weighed up on a case-by-case basis which considers the risks, particularly during a pandemic in which it may sometimes be more difficult to access healthcare 58 .

4.2 Monitoring the fetus during maternal COVID-19 infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E18 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Maternal monitoring of a pregnant woman who is seriously ill with COVID-19 is decisive for the prognosis of the fetus. Monitoring must be stepped up if there are signs that the motherʼs condition is worsening (she may imminently require artificial respiration or ECMO). Acute respiratory decompensation must be expected and measures to promptly deliver the unborn child must be discussed. | |

| Consensus-based statement 4.S3 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| There is no evidence for an optimal fetal monitoring regimen in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2. There is no evidence which shows that more intensive fetal monitoring would improve fetal outcome. | |

Acute pulmonary decompensation is characteristic of SARS-CoV-2 infection and has also been observed in pregnant women whose previous course of pregnancy was unremarkable 59 , 60 . When monitoring a viable fetus, monitoring should include CTG examinations as well as checking on fetal growth, carrying out Doppler examinations, and monitoring the amniotic fluid to exclude placental insufficiency as this can lead to FGR 61 , 62 .

4.3 Care in pregnancy after SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E19 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| A fetal assessment should be carried out if a pregnant woman is admitted to hospital and/or was treated for COVID-19 after she has recovered: e.g., fetal biometry, fetal arterial and venous Doppler, maternal Doppler (uterine arteries), Examinations should look for visible signs of infection-related fetal damage, especially cerebral signs of hypoxia/stroke/porencephalic cysts. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 4.E20 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Depending on the week of gestation of the pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection, additional examinations must be carried out on a case-by-case basis due to the higher risk of developing preeclampsia/FGR/vasculitis and the higher risk of preterm birth (e.g., FTS or precise diagnostic workup). | |

The are no resilient data about the appropriate intervals for clinical monitoring. For pregnant women who have recovered from a SARS-CoV-2 infection, had only slight, moderate, or even no symptoms and did not require admission to hospital, the RCOG recommends an unchanged regimen of prenatal care after the pregnant woman no longer needs to self-isolate 63 . In cases which take a severe course, maternal hypoxia involves a risk of fetal hypoxic damage 59 , 60 . It is therefore important that a fetal assessment is carried out at the end of any hospital treatment for COVID-19 or after severe maternal illness, which considers the clinical circumstances and manifestations of COVID-19 in the pregnant woman.

Depending on the extent and type of symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19, the risk of pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia 33 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 and preterm birth 15 , 68 – 74 is higher. A number of studies have reported a higher rate of stillbirths 33 , 68 , 75 and placental changes such as intervillous inflammation, focal vascular villitis and clot formation in fetal vessels 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 . However, these often unspecific changes are not universally demonstrable 80 , 81 .

5 Giving birth when positive for COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2

5.1 Birth companion during the birth

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E21 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Women giving birth who have tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (at least one rapid antigen test within the previous 24 h) or whose infectious status is not yet clear but who have no symptoms (e.g., results of the PCR test have not come back yet) must be permitted to have a birth companion during the birth. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E22 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| For reasons of infection control, it is not recommended that women giving birth who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 or have symptoms of COVID-19 have a birth companion. Should it nevertheless be necessary in individual cases (e.g., difficulties in communicating with the woman giving birth), the birth companion must have either recovered from SARS-CoV-2, be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 or have tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. The birth companion must be given suitable protective clothing and comply with protection measures. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E23 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Any birth companion must be asymptomatic and have no SARS-CoV-2 infection (at least one negative SARS-CoV-2 antigen test within the previous 24 h before entering the delivery ward). If possible, the birth companion must not leave the room where the pregnant woman is giving birth and must comply with the existing hygiene regulations such as the wearing of a FFP. | |

5.2 Induction of labor and monitoring of the birth

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E24 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| A SARS-CoV-2 infection or development of COVID-19 must not , by itself, constitute a reason to deliver the unborn child. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E25 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If relevant maternal respiratory or general impairments are present, the indication to deliver the infant should be reviewed regularly based on the gestational age and the severity of maternal impairment. This implies that close clinical monitoring of the mother and unborn child must be carried out regularly and include monitoring fetal vitality as well as interdisciplinary visits by medical staff from the specialist disciplines involved in the care of mother and child. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E26 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| All specialist disciplines and professions involved in or present at the birth (medical specialties, nursing care, midwives, obstetrics, anesthesiology, pediatric medicine, etc.) must be informed at an early stage that a woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 disease will soon be giving birth as this will make it possible to implement the necessary protection measures effectively in an emergency. | |

5.3 Delivery mode for women with SARS-CoV-2

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E27 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Even if the mother has a SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 disease, the delivery mode should be chosen based on obstetric criteria. | |

| Consensus-based statement 5.S4 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| In addition to the motherʼs medical condition and assumed infectiousness, the decision on the appropriate birth mode must also take account of logistical conditions, the available rooms, and available staff at the hospital. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E28 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If the clinical condition of the pregnant woman worsens during spontaneous vaginal delivery, changing the birth mode should be considered. | |

5.4 Analgesia during delivery

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E29 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If the pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 disease requests analgesia, she must be offered neuraxial analgesia (e.g., epidural analgesia) at an early stage. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E30 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Because of the increased aerosol formation, the use of nitrous oxide (N 2 O) should be avoided when caring for a parturient woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 disease in favor of other available alternatives such as neuraxial analgesia. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 5.E31 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Because of the potential respiratory depression effect, continuous monitoring of SARS-CoV-2-positive patients (1 : 1 care) must be carried out if opioids, particularly remifentanil, are administered, including monitoring the oxygen saturation with the aim of ensuring an oxygen saturation of at least 94% (SpO 2 ≥ 94%). | |

6 Neonates: rooming-in, breastfeeding and testing

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E32 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Rooming-in and bonding with a mother who has tested positive for SARS-CoV-2/has developed COVID-19 should be supported subject to adequate hygiene measures. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E33 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Women who are positive for SARS-CoV-2/have COVID-19 disease must be supported to breastfeed. Special hygiene measures should be observed. If the health of the mother or infant does not permit breastfeeding, the goal should be to use expressed breastmilk to feed the infant. | |

| Consensus-based statement 6.S5 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| It is not necessary to test the breastmilk for SARS-CoV-2 virus. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E34 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| General screening of asymptomatic neonates who do not require special neonatal care born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 disease must not be carried out. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E35 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Testing for SARS-CoV-2 in a neonate not requiring neonatal care may be carried out if, for example, it can be assumed that the mother is contagious. The SARS-CoV-2 test must be carried out using a nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test. | |

| Consensus-based statement 6.S6 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If a test is carried out to exclude intrauterine transmission, then it must be carried out within 24 h post partum. It is important to be aware that if testing is done immediately after the birth, it may result in a false-positive result due to transient contamination by maternal secretions. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 6.E36 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| Irrespective of any neonatal or maternal symptoms, a neonate requiring neonatal care with evidence of maternal peripartum SARS-CoV-2/maternal contagiousness must be tested for SARS-CoV-2 using a RT-PCR test on admission. During the time the infant is kept in neonatal intensive care or in a peripheral ward, a PCR test should be carried out on the 3rd day and repeated on the 5th day of treatment due to an average incubation period of 4 – 5 days. The isolation period should be agreed on a case-by-case basis with the local hygiene team. | |

Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 may occur antenatally, during the birth, or postnatally 82 . Intrauterine transmission appears to be possible at any time during pregnancy 82 , 83 , 84 but it has only been reported in isolated cases with severe maternal disease 85 , 86 , 87 . Transmission to the neonate during the birth through maternal aerosols or fecal contamination of the birth canal is possible in cases of acute maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection (from 14 days before to 2 days after the birth, in very rare cases even when the infection did not occur recently 82 , 88 , 89 , 90 .

The professional medical associations which agreed upon and voted for these recommendations explicitly support both immediate contact between mother and child and breastfeeding, as long as appropriate hygiene measures are followed 3 , 91 – 95 . Hygiene measures are summarized in Table 6 .

Table 6 Hygiene measures.

| Hygiene measures during rooming-in/breastfeeding for mothers who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 |

|---|

|

General testing of all neonates born to mothers positive for SARS-CoV-2 does not offer any guaranteed benefits 96 , 97 . The course of neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections is almost always unproblematic 86 , 93 , 98 and often (in 45% of cases, according to a meta-analysis of 176 neonates) asymptomatic 86 . But testing for SARS-CoV-2 may be carried out for other reasons, for example, for epidemiological reasons or to allow the removal of isolation measures. As is done in adults and children, a swab taken from around the respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, nasal area) is suitable for RT-PCR testing 91 , 95 , 98 . There are no other laboratory parameters specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Leukopenia, lymphocytopenia and thrombocytopenia have been observed, as have elevated transaminase levels; CRP and procalcitonin are usually in normal ranges in neonates 99 . A differential diagnosis may be considered and appropriate examinations carried out if the neonate presents with symptoms 95 .

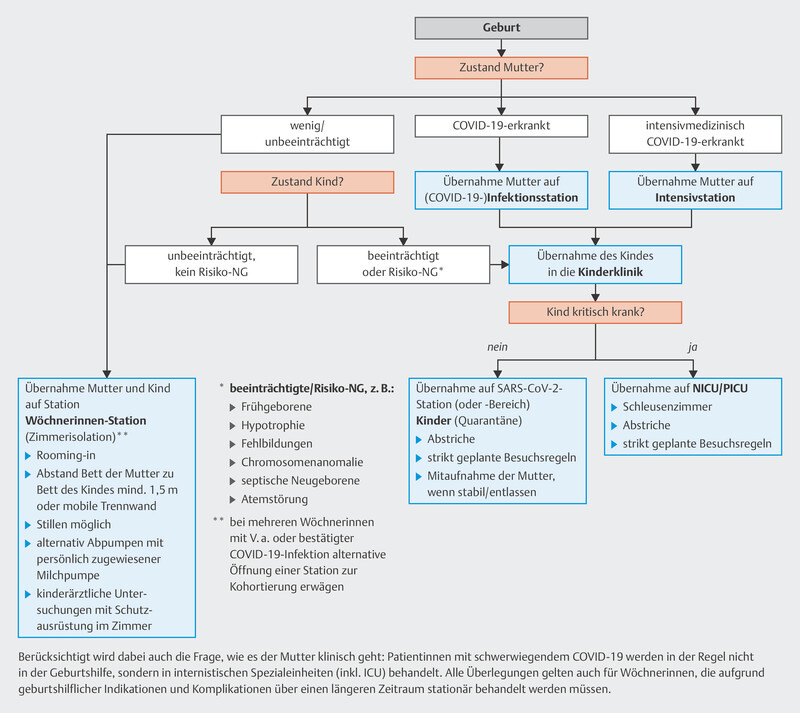

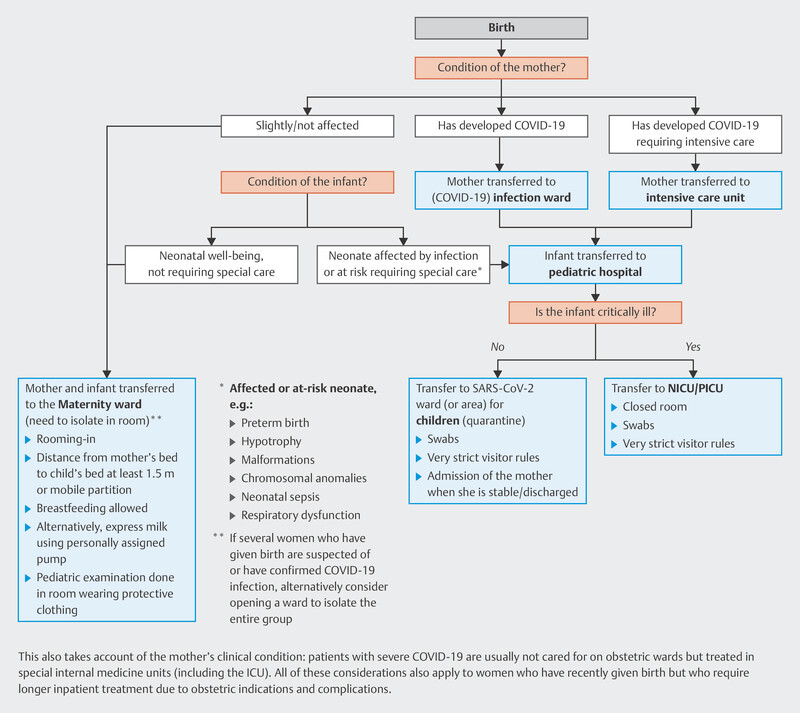

A possible care algorithm for neonates born to mothers who tested positive for acute SARS-CoV-2 compiled by the DGPI, DGPM und DGGG and published in March 2020 has proved to be useful during the pandemic and is shown in Fig. 1 91 .

Abb. 1.

Possible care algorithm for neonates born to mother who have tested positive for acute SARS-CoV-2 according to the extent of disease of mother and child. [rerif]

7 Thromboprophylaxis

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E37 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

The following parameters

must

be considered when deciding whether VTE prophylaxis during pregnancy/puerperium of women with SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 is indicated:

| |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E38 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If a pregnant woman with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and no additional VTE risk factors is receiving outpatient care, she must not be given anticoagulants. | |

| Consensus-based statement 7.S7 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| References: 63 , 100 | |

| In addition to the above-mentioned recommendations for an individual VTE risk assessment, a points system can be used for patients treated in an outpatient setting (e.g., please refer to the guideline 015/092 published at the webside of the AWMF or the RCOG Green Top Guideline 37a). A SARS-CoV-2 infection would be categorized as “systemic infection” even though SARS-CoV-2 infection was not anticipated at the time when the points system was compiled. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E39 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| All pregnant women admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 must receive prophylactic medication against thromboembolisms and medication should be continued as long as symptoms continue, unless medication is contraindicated. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E40 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

|

If thromboprophylaxis is indicated, it

must

be done using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

Unfractionated heparin may be used in an intensive care setting. Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors should not be used for thromboprophylaxis. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 7.E41 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If thromboprophylaxis is indicated due to COVID-19 it should be continued until the patient has no more symptoms. | |

| Consensus-based statement 7.S8 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| There is no evidence that thromboprophylaxis only because of COVID-19 should be continued after the patient no longer has COVID-19 symptoms. | |

Irrespective of any SARS-CoV-2 infection, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is higher during pregnancy, increases with increasing gestational age, and is at its highest in the first 2 weeks after the birth. The risk of VTE is 2 times higher in the first and second trimester of pregnancy, 9 times higher in the third trimester, and 60 – 80 times higher in the first 2 to 6 weeks after the birth compared to non-pregnant women 101 , 102 .

Irrespective of whether a woman is pregnant or not, systemic microangiopathies and thromboembolisms are particularly likely to develop if a woman has severe COVID-19 103 , 104 . Direct obstetric data about the risk of venous thromboembolisms combined with SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 are limited but they do appear to indicate an additional higher risk for infected pregnant women compared to non-infected pregnant women (0.2 vs. 0.1%; aOR 3.4, 95% CI: 2.0 – 5.8) 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 .

The indication for VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy/puerperium for women with SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 is cumulatively justified based on 3 parameters:

The dynamics of the symptoms of disease: asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, critical

The care situation: outpatient or inpatient

The individual risk of VTE: pre-existing and acquired risk factors

The decision whether to continue VTE prophylaxis for pregnant women or postpartum patients on discharge must be made on a case-by-case basis which also considers additional existing VTE risk factors and the patientʼs obstetric course. While COVID-19 is assumed to be a transient risk factor, continuing with VTE prophylaxis medication after COVID symptoms are no long present appears to be appropriate.

As regards the decision to administer anticoagulants in an inpatient setting, please also refer to the German-language AWMF S3-guideline “Recommendations for the Inpatient Treatment of Patients with COVID-19” 2 .

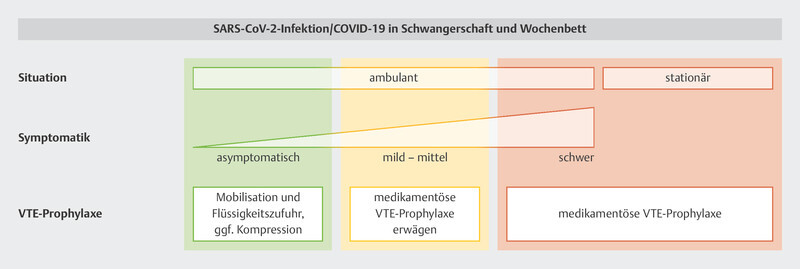

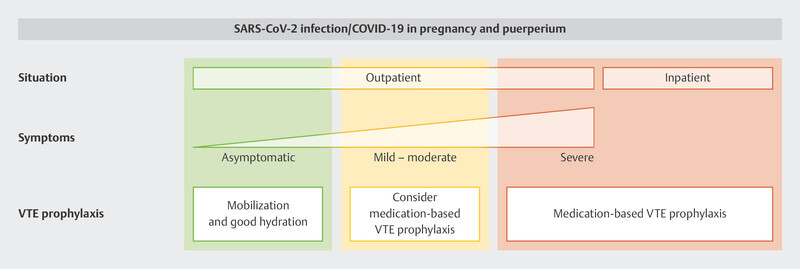

Recommendations for VTE prophylaxis based on the individual care situation and the specific risk factors at different obstetric timepoints are summarized in Fig. 2 3 .

Abb. 2.

Recommendations on VTE prophylaxis for pregnant women/women who have recently given birth with SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 based on the situation, symptoms and individual risk factors (from 3 ). [rerif]

The Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology has published a detailed schematic scoring system to support decisions when to administer anticoagulants to pregnant women and women who have recently given birth in its Green Top Guideline 37a 100 . In their guideline, SARS-CoV-2 infection is modelled as a transient risk factor under the heading “systemic infection”, even though SARS-CoV-2 infection could not have been anticipated at the time when the scoring system was compiled. The scoring system is shown in the long version of this guideline.

8 Drug therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection

8.1 Use of corticosteroids during SARS-CoV-2 infection

8.1.1 Systemic antenatal administration of corticosteroids for fetal indications

| Consensus-based recommendation 8.E42 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

|

A pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection

must

be given antenatal steroids for fetal indications if she shows signs of clinical worsening (e.g., intubation/ECMO is

planned) between weeks 23 + 5 and 34 + 0 of gestation (2 × 12 mg betamethasone/celestan administered intramuscularly (IM) with an interval of 24 h between doses);

alternatively, the patient may be treated with dexamethasone (IM) 4 × 6 mg every 12 h.

It is currently not possible to answer the question whether betamethasone is equivalent to dexamethasone with regards to COVID-19. | |

8.1.2 Systemic corticosteroid administration to treat COVID-19

| Consensus-based recommendation 8.E43 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If maternal corticosteroid therapy is indicated due to maternal COVID-19 symptoms, an assessment must be made at the same time whether antenatal administration of steroids is required for fetal indications. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 8.E44 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| The indications to administer corticosteroids to pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection must be the same as those for non-pregnant women. | |

| Consensus-based recommendation 8.E45 | |

|---|---|

| Expert consensus | Level of consensus +++ |

| If a pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection is administered corticosteroids based on the AWMF S3-guideline 113/001, consideration must be given to replacing dexamethasone with prednisolone or hydrocortisone as they do not cross the placenta as much and have fewer side effects on the fetus (6 mg dexamethasone/24 h oral/IV ≙ 40 mg prednisolone/24 h oral ≙ 2 × 80 mg hydrocortisone/24 h IV). | |

8.1.3 Inhalative corticosteroids

In the S2e-guideline “SARS-CoV-2/Covid-19 Information & Practical Help for General Practitioners in Private Practice”, the German Society for General and Family Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V.) recommends that “patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who are at risk of severe course of disease may be offered budesonide inhalation (2 × 800 µg/d for 7 – 14 days) to reduce this risk (off-label therapy)” 1 .

8.2 Antiviral or COVID-19-specific drugs

For treatment regimens and drug-based treatment options, please refer to the German-language S3-guideline with the AWMF registry no. 113/001 “Recommendations for the Inpatient Treatment of Patients with COVID-19” 2 as well as the statements “Antiviral Medicinal Products for the Treatment of COVID-19” 109 and “COVID-19 Pre-exposition Prophylaxis” 110 issued by the Commission “Benefit Assessment of Medicinal Products”. The recommendations are based on the RCOG guideline “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Pregnancy” 63 and the guideline of the WHO “Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living Guideline” 111 and are summarized in Table 7 .

Table 7 Specific COVID-19 medications in pregnancy.

| Specific medication for COVID-19 | Data basis/recommendations for use |

|---|---|

| Sotrovimab, casirivimab/imdevimab, tixagevimab/cilgavimab (neutralizing monoclonal antibodies) | No associated increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Data are limited; therefore, no final assessment can be made 63 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 . |

| Remdesivir (antiviral medicine) | WHO and RCOG recommend that it should be avoided in pregnancy. But because of the low rates of adverse events, administering the drug may be considered if the patient shows signs of clinical deterioration 63 , 111 , 118 , 119 . |

| Tocilizumab (interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor) | Only limited data available. No indications of teratogenicity or fetotoxicity 63 , 111 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 . |

| Molnupiravir (antiviral medicine) | Should not be prescribed 111 . |

| Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, protease inhibitors) | No data on the use of these medications in pregnancy. Must only be administered if potential benefit is clear 124 , 125 . |

9 Vaccinations in Pregnancy

The Standing Commission on Vaccination at the RKI (STIKO) recommends that all unvaccinated persons of childbearing age should be vaccinated against COVID-19 to ensure that they already have optimum protection against the disease before the start of any pregnancy. The recommendation is that pregnant women who have not yet been vaccinated should receive a vaccination consisting of two doses of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, with an interval of 3 – 6 weeks between vaccinations (Comirnaty) from the 2nd trimester of pregnancy. If the pregnancy was only detected after the first vaccination, the second vaccination should only be administered from the 2nd trimester of pregnancy. In addition, the STIKO recommends that unvaccinated breastfeeding mother should be vaccinated with two doses of an mRNA vaccine, with an interval of 3 – 6 weeks between vaccinations (Comirnaty) (as at 16.09.2021). The recommendations regarding booster vaccinations for pregnant women also apply (as at 15.02.2022) 126 , 127 . In this context, please refer to the very detailed German-language “Justification of the STIKO for the Vaccination of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women against COVID-19” 128 .

The guideline authors agree with the recommendations of the STIKO.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authorsʼ conflicts of interest are listed in the long version of the guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

References

- 1.Blankenfeld H, Kaduszkiewicz H, Kochen M Met al. AWMF 053/054. SARS-CoV-2/Covid-19 Informationen und Praxishilfen für niedergelassene Hausärztinnen und Hausärzte. 2022Accessed February 23, 2022 at:https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/053-054.html

- 2.Kluge S, Janssens U, Welte Tet al. AWMF 113/001. Empfehlungen zur stationären Therapie von Patienten mit COVID-19 – Living Guideline. 2021Accessed February 23, 2022 at:https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/113-001LG.html

- 3.Zöllkau J, Hagenbeck C, Hecher K et al. [Recommendations for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 during Pregnancy, Birth and Childbed – Update November 2021 (Long Version)] Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2022;226:e1–e35. doi: 10.1055/a-1688-9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi R, Bauer N H, Becke-Jakob K AWMF 087/001. Empfehlungen für die strukturellen Voraussetzungen der perinatologischen Versorgung in Deutschland. 2021. https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/087-001l_S2k_Empfehlungen-strukturelle-Voraussetzungen-perinatologische-Versorgung-Deutschland__2021-04_01.pdf. https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/087-001l_S2k_Empfehlungen-strukturelle-Voraussetzungen-perinatologische-Versorgung-Deutschland__2021-04_01.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.von der Wense A, Roll C, Maier R F AWMF 024/002. Verlegung von Früh- und Reifgeborenen in Krankenhäuser der adäquaten Versorgungsstufe. 2019. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/024-002l_S1_Verlegung-Fruehgeborene-Reifgeborene_2019-05.pdf https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/024-002l_S1_Verlegung-Fruehgeborene-Reifgeborene_2019-05.pdf

- 6.Janssens U, Schlitt A, Hein A AWMF 040/015. SARS-CoV-2 Infektion bei Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeitern im Gesundheitswesen – Bedeutung der RT-PCR Testung. 2020. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/040-015.html https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/040-015.html

- 7.Mattner F. AWMF 067/010. Infektionsprävention durch das Tragen von Masken. 2020. https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/067-010.html https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/067-010.html

- 8.COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Review Group Effort (SURGE) study authors . Chu D K, Akl E A, Duda S et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan V WS, Ng H HL, Rahman L et al. Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 1 and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 During Aerosol-Generating Procedures in Critical Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1159–1168. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley J, Huntley J M, Miller J A et al. Mask Effectiveness for Preventing Secondary Cases of COVID-19, Johnson County, Iowa, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:69–75. doi: 10.3201/eid2801.211591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hein A, Kehl S, Häberle L et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Pregnant Women Assessed by RT-PCR in Franconia, Germany: First Results of the SCENARIO Study (SARS-CoV-2 prEvalence in pregNAncy and at biRth InFrancOnia) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2022;82:226–234. doi: 10.1055/a-1727-9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.RKI . RKI – Infektionskrankheiten A–Z – COVID-19 (Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2). 2021. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Teststrategie/Nat-Teststrat.html https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Teststrategie/Nat-Teststrat.html

- 13.Sitter M, Pecks U, Rüdiger M et al. Pregnant and Postpartum Women Requiring Intensive Care Treatment for COVID-19-First Data from the CRONOS-Registry. J Clin Med. 2022;11:701. doi: 10.3390/jcm11030701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Z, McGoogan J M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danielsen A S, Cyr P R, Magnus M C et al. Birthing parents had a lower risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the peripartum period in Norway, 15th of February 2020 to 15th of May 2021. Infect Prev Pract. 2021;3:100183. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2021.100183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ISARIC4C investigators . Docherty A B, Harrison E M, Green C A et al. Features of 20133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanczyk P, Jachymski T, Sieroszewski P. COVID-19 during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum period based on EBM. Ginekol Pol. 2020;91:417–423. doi: 10.5603/GP.2020.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selim M, Mohamed S, Abdo M et al. Is COVID-19 Similar in Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women? Cureus. 2020;12:e8888. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenling Y, Junchao Q, Zhirong X et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19: management and challenges. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2020;62:1–9. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202062062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson J L, Nguyen L M, Noble K N et al. COVID-19-related disease severity in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84:e13339. doi: 10.1111/aji.13339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molteni E, Astley C M, Ma W et al. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection in pregnant women: characterization of symptoms and syndromes predictive of disease and severity through real-time, remote participatory epidemiology. medRxiv [Preprint] 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.17.20161760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettirosso E, Giles M, Cole S et al. COVID-19 and pregnancy: A review of clinical characteristics, obstetric outcomes and vertical transmission. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;60:640–659. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna N, Hanna M, Sharma S. Is pregnancy an immunological contributor to severe or controlled COVID-19 disease? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84:e13317. doi: 10.1111/aji.13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blitz M J, Rochelson B, Prasannan L et al. Racial and ethnic disparity and spatiotemporal trends in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 prevalence on obstetrical units in New York. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emeruwa U N, Spiegelman J, Ona S et al. Influence of Race and Ethnicity on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection Rates and Clinical Outcomes in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1040–1043. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flannery D D, Gouma S, Dhudasia M B et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among parturient women in Philadelphia. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd5709. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellington S, Strid P, Tong V T et al. Characteristics of Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status – United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:769–775. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore J T, Ricaldi J N, Rose C E et al. Disparities in Incidence of COVID-19 Among Underrepresented Racial/Ethnic Groups in Counties Identified as Hotspots During June 5–18, 2020–22 States, February–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1122–1126. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zambrano L D, Ellington S, Strid P et al. Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status – United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasannan L, Rochelson B, Shan W et al. Social determinants of health and coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haizler-Cohen L, Moncada K, Collins A et al. 611 Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:S383. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurol-Urganci I, Jardine J E, Carroll F et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of birth in England: national cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:5220–5.22E13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Mascio D, Sen C, Saccone G et al. Risk factors associated with adverse fetal outcomes in pregnancies affected by Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a secondary analysis of the WAPM study on COVID-19. J Perinat Med. 2020;48:950–958. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2020-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahu A K, Sreepadmanabh M, Rai M et al. SARS-CoV-2: phylogenetic origins, pathogenesis, modes of transmission, and the potential role of nanotechnology. Virusdisease. 2021;32:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00653-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vousden N, Bunch K, Morris E et al. The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: A national cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pecks U, Kuschel B, Mense L et al. Pregnancy and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Germany-the CRONOS Registry. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:841–842. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutton D, Fuchs K, DʼAlton M et al. Universal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Women Admitted for Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khalil A, Hill R, Ladhani S et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in pregnancy: symptomatic pregnant women are only the tip of the iceberg. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:296–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell K H, Tornatore J M, Lawrence K E et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Among Patients Admitted for Childbirth in Southern Connecticut. JAMA. 2020;323:2520–2522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donders F, Lonnée-Hoffmann R, Tsiakalos A et al. ISIDOG Recommendations Concerning COVID-19 and Pregnancy. Diagnostics. 2020;10:243. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10040243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koczulla A R, Ankermann T, Gogoll C AWMF 067/010. S1-Leitlinie Post-COVID/Long-COVID. https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/020-027 https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/020-027

- 43.G-BA . Richtlinien des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über die ärztliche Betreuung während der Schwangerschaft und nach der Entbindung („Mutterschafts-Richtlinien“). 2022. https://www.g-ba.de/richtlinien/19/ https://www.g-ba.de/richtlinien/19/

- 44.für die Leitlinienkommission . Schlembach D, Stepan H. AWMF 015/018. Hypertensive Schwangerschaftserkrankungen. https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/015-018 Diagnostik und Therapie. 2019:1–117. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Louwen F, Wagner U, Abou-Dakn M et al. Caesarean Section. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/084, June 2020) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021;81:896–921. doi: 10.1055/a-1529-6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abou-Dakn M, Schäfers R, Peterwerth N et al. Vaginal Birth at Term – Part 1. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/083, December 2020) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2022;82:1143–1193. doi: 10.1055/a-1904-6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kehl S, Dötsch J, Hecher K et al. Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Guideline of the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (S2k-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/080, October 2016) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77:1157–1173. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berger R, Abele H, Bahlmann F et al. Prevention and Therapy of Preterm Birth. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/025, February 2019) – Part 1 with Recommendations on the Epidemiology, Etiology, Prediction, Primary and Secondary Prevention of Preterm Birth. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2019;79:800–812. doi: 10.1055/a-0903-2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.KBV; BÄK GBW Influenzapandemie Risikomanagement in Arztpraxen. 2008Accessed February 23, 2022 at:https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/_old-files/downloads/Risikomanagement_in_Arztpraxen.pdf

- 50.Rempen A, Chaoui R, Häusler M et al. Quality Requirements for Ultrasound Examination in Early Pregnancy (DEGUM Level I) between 4 + 0 and 13 + 6 Weeks of Gestation. Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:579–583. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-115581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozlowski P, Burkhardt T, Gembruch U et al. DEGUM, ÖGUM, SGUM and FMF Germany Recommendations for the Implementation of First-Trimester Screening, Detailed Ultrasound, Cell-Free DNA Screening and Diagnostic Procedures. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:176–193. doi: 10.1055/a-0631-8898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Kaisenberg C, Klaritsch P, Ochsenbein-Kölble N et al. Screening, Management and Delivery in Twin Pregnancy. Ultraschall Med. 2021;42:367–378. doi: 10.1055/a-1248-8896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Von Kaisenberg C, Chaoui R, Häusler M et al. Quality Requirements for the early Fetal Ultrasound Assessment at 11–13 + 6 Weeks of Gestation (DEGUM Levels II and III) Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:297–302. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merz E, Eichhorn K H, Von Kaisenberg C et al. Aktualisierte Qualitätsanforderungen an die weiterführende differenzierte Ultraschalluntersuchung in der pränatalen Diagnostik (= DEGUM-Stufe II) im Zeitraum von 18 + 0 bis 21 + 6 Schwangerschaftswochen. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:593–596. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaoui R, Heling K, Mielke G et al. [Quality standards of the DEGUM for performance of fetal echocardiography] Ultraschall Med. 2008;29:197–200. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faber R, Heling K S, Steiner H et al. [Doppler Sonography during Pregnancy – DEGUM Quality Standards and Clinical Applications] Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:319–325. doi: 10.1055/a-0800-8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faber R, Heling K S, Steiner H et al. Doppler ultrasound in pregnancy – quality requirements of DEGUM and clinical application (part 2) Ultraschall Med. 2021;42:541–550. doi: 10.1055/a-1452-9898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kleinwechter H, Groten T, Schäfer-Graf U et al. COVID-19 and pregnancy: Case series with diabetes co-morbidity from the registry study ‘Covid-19 Related Obstetric and Neonatal Outcome Study’ (CRONOS) Diabetologe. 2021;17:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machluf Y, Rosenfeld S, Ben Shlomo I et al. The Misattributed and Silent Causes of Poor COVID-19 Outcomes Among Pregnant Women. Front Med. 2021;8:1902. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.745797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Düppers A L, Bohnhorst B, Bültmann E et al. Severe fetal brain damage subsequent to acute maternal hypoxemic deterioration in COVID-19. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;58:490–491. doi: 10.1002/uog.23744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang H, Acharya G. Novel corona virus disease (COVID-19) in pregnancy: What clinical recommendations to follow? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:439–442. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rasmussen S A, Smulian J C, Lednicky J A et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.RCOG Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection and pregnancy. 2022Accessed February 27, 2022 at:https://www.rcog.org.uk/coronavirus-pregnancy

- 64.Antoun L, Taweel N E, Ahmed I et al. Maternal COVID-19 infection, clinical characteristics, pregnancy, and neonatal outcome: A prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:559–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diriba K, Awulachew E, Getu E. The effect of coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV) during pregnancy and the possibility of vertical maternal-fetal transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25:39. doi: 10.1186/s40001-020-00439-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahlberg M, Neovius M, Saltvedt S et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 Test Status and Pregnancy Outcomes. JAMA. 2020;324:1782–1785. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Papageorghiou A T, Deruelle P, Gunier R B et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:2890–2.89E19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei S Q, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S et al. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2021;193:E540–E548. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier R B et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19 Infection: The INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pirkle C M. Evidence based care for pregnant women with covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jafari M, Pormohammad A, Sheikh Neshin S A et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–16. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khalil A, Kalafat E, Benlioglu C et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical features and pregnancy outcomes. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100446. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group . Martinez-Perez O, Prats Rodriguez P, Muner Hernandez M et al. The association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and preterm delivery: a prospective study with a multivariable analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:273. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03742-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stock S J, Carruthers J, Calvert C et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat Med. 2022;28:504–512. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Radan A P, Baud D, Favre G et al. Low placental weight and altered metabolic scaling after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 infection during pregnancy: a prospective multicentric study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:718–722. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prabhu M, Cagino K, Matthews K C et al. Pregnancy and postpartum outcomes in a universally tested population for SARS-CoV-2 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2020;127:1548–1556. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kirtsman M, Diambomba Y, Poutanen S M et al. Probable congenital SARS-CoV-2 infection in a neonate born to a woman with active SARS-CoV-2 infection. CMAJ. 2020;192:E647–E650. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mulvey J J, Magro C M, Ma L X et al. Analysis of complement deposition and viral RNA in placentas of COVID-19 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2020;46:151530. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2020.151530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smithgall M C, Liu-Jarin X, Hamele-Bena D et al. Third-trimester placentas of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive women: histomorphology, including viral immunohistochemistry and in-situ hybridization. Histopathology. 2020;77:994–999. doi: 10.1111/his.14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gulersen M, Prasannan L, Tam Tam H et al. Histopathologic evaluation of placentas after diagnosis of maternal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.WHO Definition and categorization of the timing of mother-to-child transmission of SARS-CoV-2. 2021Accessed March 02, 2022 at:https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-pregnancy-and-childbirth

- 83.Gengler C, Dubruc E, Favre G et al. SARS-CoV-2 ACE-receptor detection in the placenta throughout pregnancy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:489. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]