Abstract

Nervous systems of bilaterally-symmetric animals display left-right asymmetries in development. In Caenorhabditis elegans , the Q neuroblasts display left-right asymmetry of migration, with QR on the right migrating anteriorly and QL on the left migrating posteriorly. Previous worked showed that a group of transmembrane receptor molecules including UNC-40 /DCC and PTP-3 /LAR control direction of initial Q migration. However, no classical secreted paracrine growth factor has been identified. Previous work showed that molecules in the extracellular matrix are involved, including UNC-52 /Perlecan and the cuticle collagens DPY-17 and SQT-3 . This report shows that the cuticle collagen DPY-14 is also involved, and genetically acts with DPY-17 and SQT-3 , possibly in a collagen trimer. DPY-14 might be a component of an inherent left-right chirality in the extracellular matrix that directs left-right asymmetric Q neuroblast migration.

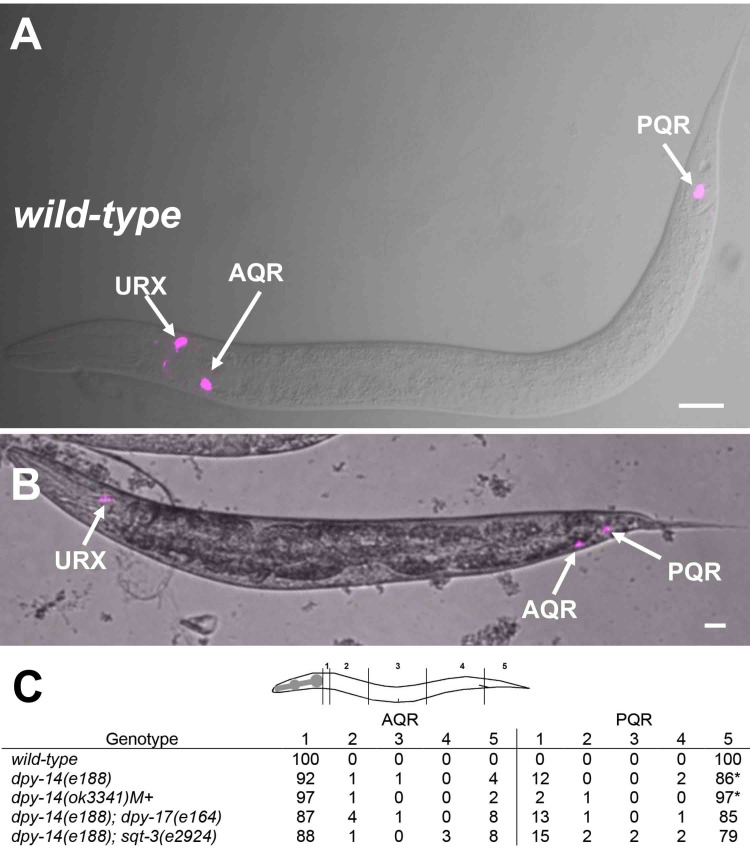

Figure 1. AQR and PQR migration.

The lqIs244 [Pgcy-32::cfp] transgene was used to visualize AQR in the head and PQR in the tail. A) A wild type larva showing AQR position and PQR position. The URX neurons also express Pgcy-32::cfp . B) A dpy-14 ( e188 ) larva with AQR that has migrated posteriorly toward the tail. The scale bars represents 10μM. C) Quantification of AQR and PQR migration in different genotypes. For each genotype, 100 animals were scored. The locations of AQR and PQR along the body were scored on a 5-position scale (see diagram). 1 is the wild-type position of AQR; 2 is posterior to the normal AQR position but anterior to the vulva; 3 is at or near the vulva; 4 is the normal birth position of the Q neuroblasts; and 5 is the wild-type position of PQR. In pairwise comparisons using Fisher's exact test, there were no significant differences at positions 1 and 5 between dpy-14 ( e188 ) and double mutants with dpy-17 ( e164 ) or sqt-3 ( e2924 ). dpy-14 ( ok3341 )M+ was significantly different from dpy-14 ( e188 ) at PQR position 5 ( p = 0.01) (asterisk).

Description

The bilateral Q neuroblasts are sisters of the V5 seam cells and are born during embryogenesis (Sulston and Horvitz 1977; Chapman et al. 2008; Middelkoop and Korswagen 2014). At larval hatching, QR on the right protrudes and migrates anteriorly over the V4 seam cell, and QL on the left protrudes and migrates posteriorly over the V5 seam cell (Chapman et al. 2008). QR and QL then undergo an identical pattern of cell division, cell death, and neuronal differentiation to produce three neurons each. QR produces AQR, AVM, and SDQR, and QL produces PQR, PVM, and SDQL. QR daughters migrate anteriorly, including AQR which migrates the longest distance to the deirid ganglion near the pharynx ( Figure 1A ). QL daughters migrate posteriorly, with PQR migrating the longest distance to the phasmid ganglion posterior to the anus ( Figure 1A ).

A group of transmembrane receptor molecules act together to control the initial migration of QR and QL, including UNC-40 /DCC, PTP-3 /LAR, MIG-21 , and the Cadherins CDH-3 and CDH-4 (Middelkoop et al. 2012; Sundararajan and Lundquist 2012; Sundararajan et al. 2014; Ebbing et al. 2019). In QL, UNC-40 /DCC and PTP-3 /LAR act redundantly in parallel to drive posterior protrusion and migration. In QR, UNC-40 and PTP-3 mutually inhibit one another's posterior migration activity, resulting in anterior protrusion and migration. Defects in the direction of initial migration affects the subsequent migration of AQR and PQR (Chapman et al. 2008). unc-40 , ptp-3 , mig-21 , and cdh-4 mutants each have misdirected AQR and PQR migration, with AQR sometimes migrating posteriorly and PQR sometimes migrating anteriorly.

Previous studies indicate that the cuticle collagen genes dpy-17 and sqt-3 result in initial QL and QR migration defects similar to unc-40 , ptp-3 , mig-21 , and cdh-4 (Lang and Lundquist 2021) . dpy-17 and sqt-3 encode similar single collagen repeat molecules of the collagen IV family (Novelli et al. 2006; Fotopoulos et al. 2015). Work described here shows that the dpy-14 is also required AQR and PQR migration similar to dpy-17 and sqt-3 . dpy-14 ( e188 ) has a morphological phenotype similar to dpy-17 and sqt-3 : a spindle-shaped Dpy that is very severe in early larval development and that gets less severe as the animals develop to adulthood (Gallo et al. 2006). dpy-14 encodes a cuticle collagen with a single collagen repeat similar to DPY-17 and SQT-3 (Gallo et al. 2006). dpy-14 ( e188 ) mutants displayed defects in AQR and PQR migration, with reversals of direction of migration of both cells: 6% of AQRs migrated posteriorly to the normal position of PQR ( Figure 1B and C); and 11% of PQR migrated anteriorly to the normal position of AQR ( Figure 1C ). This is similar to the level of defects observed in dpy-17 and sqt-3 mutants (Lang and Lundquist 2021) . A deletion of the dpy-14 gene, dpy-14 ( ok3341 ) , resulted in sterile Dpy adults. dpy-14 ( ok3341 ) animals with wild-type maternal dpy-14 activity also displayed AQR and PQR migration reversals, with AQR migration significantly less severe than dpy-14 ( e188 ) ( Figure 1C ). This difference could be due to wild-type maternal dpy-14 activity in dpy-14 ( ok3341 ). However, dpy-14 ( e188 ) is a missense mutation that changes glycine 139 to arginine in the first collagen Gly–X–Y region (Gallo et al. 2006). Gly–X–Y repeats are required for trimerization of collagen monomers to form the collagen triple-helix (Bella et al. 1994; Bella et al. 2006). These data suggest that dpy-14 ( e188 ) might not be a simple loss of function of dpy-14 and might have some dominant interfering activity, possibly with dpy-17 and/or sqt-3 .

Double mutants of dpy-17 and sqt-3 were no more severe than single mutants alone (Lang and Lundquist 2021) . sqt-3 ; dpy-14 ( e188 ) and dpy-17 ; dpy-14 ( e188 ) double mutants were also no more severe than either single alone (Table 1). The triple mutant could not be constructed and is likely inviable. In any event, these results suggest that DPY-14 , DPY-17 , and SQT-3 all act together to regulate AQR and PQR migration. DPY-17 and SQT-3 are thought to act together in a trimer (Novelli et al. 2006). One attractive hypothesis is that each of these three Collagen monomers form a Collagen triple helix molecule that acts in AQR and PQR migration.

No classical secreted paracrine factor has been identified that regulates the left-right asymmetry of Q neuroblast migration, although the basement membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan UNC-52 /Perlecan is involved (Ochs et al. 2022), and this work and previous work (Lang and Lundquist 2021) suggests that the collagen extracellular matrix is involved. Possibly, the Q neuroblasts are responding to inherent left-right chirality that is present in extracellular matrices including the cuticle (Bergmann et al. 1998) to migrate anteriorly on the right and posteriorly on the left. UNC-52 /Perlecan and a DPY-17 / SQT-3 / DPY-14 collagen trimer might be part of this extracellular matrix left-right chirality to which the Q neuroblasts respond.

Methods

Standard C. elegans genetics and culture techniques at 20°C were utilized (Brenner 1974) . AQR and PQR were visualized using Pgcy-32::cfp transgenes (Chapman et al. 2008; Josephson et al. 2016). AQR and PQR position along the body was noted using a five-position scale as previously described (Josephson et al. 2016; Lang and Lundquist 2021) (see Figure 1C ): position 1 is the normal position of AQR in the deirid ganglion in the anterior; position 2 is posterior to the normal position of AQR but anterior to the vulva; position three is around the vulva; position four if the birthplace of the Q neuroblasts in the posterior; and position 5 is the normal final position of PQR in the tail in the phasmid ganglion behind the anus.

Reagents

The following C. elegans mutants and variants were used: LGI, dpy-14 ( e188 ), dpy-14 ( ok3341 ), tmC20 ; LGII, lqIs244 [Pgcy-32::cfp]; LGIII, dpy-17 ( e164 ); LGV, sqt-3 ( e2924 ) . The tmC20 balancer (Dejima et al., 2018) was used to maintain dpy-14 ( ok3341 ) heterozygotes . The following strains were analyzed:

|

Strain |

Genotype |

Origin |

|

wild-type |

CGC |

|

|

CGC/this work |

||

|

CGC/this work |

||

|

CGC/this work |

||

|

CGC/this work |

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Wormbase. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

References

- Bella J, Eaton M, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Crystal and molecular structure of a collagen-like peptide at 1.9 A resolution. Science. 1994 Oct 7;266(5182):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7695699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella J, Liu J, Kramer R, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Conformational effects of Gly-X-Gly interruptions in the collagen triple helix. J Mol Biol. 2006 Jul 15;362(2):298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann DC, Crew JR, Kramer JM, Wood WB. Cuticle chirality and body handedness in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Genet. 1998;23(3):164–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)23:3<164::AID-DVG2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974 May 1;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JO, Li H, Lundquist EA. The MIG-15 NIK kinase acts cell-autonomously in neuroblast polarization and migration in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2008 Sep 24;324(2):245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejima K, Hori S, Iwata S, Suehiro Y, Yoshina S, Motohashi T, Mitani S. An Aneuploidy-Free and Structurally Defined Balancer Chromosome Toolkit for Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Rep. 2018 Jan 2;22(1):232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbing A, Middelkoop TC, Betist MC, Bodewes E, Korswagen HC. Partially overlapping guidance pathways focus the activity of UNC-40/DCC along the anteroposterior axis of polarizing neuroblasts. Development. 2019 Sep 25;146(18) doi: 10.1242/dev.180059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulos P, Kim J, Hyun M, Qamari W, Lee I, You YJ. DPY-17 and MUA-3 Interact for Connective Tissue-Like Tissue Integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans: A Model for Marfan Syndrome. G3 (Bethesda) 2015 Apr 27;5(7):1371–1378. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo M, Mah AK, Johnsen RC, Rose AM, Baillie DL. Caenorhabditis elegans dpy-14: an essential collagen gene with unique expression profile and physiological roles in early development. Mol Genet Genomics. 2006 Feb 22;275(6):527–539. doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson MP, Chai Y, Ou G, Lundquist EA. EGL-20/Wnt and MAB-5/Hox Act Sequentially to Inhibit Anterior Migration of Neuroblasts in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2016 Feb 10;11(2):e0148658–e0148658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AE, Lundquist EA. The Collagens DPY-17 and SQT-3 Direct Anterior-Posterior Migration of the Q Neuroblasts in C. elegans. J Dev Biol. 2021 Feb 19;9(1) doi: 10.3390/jdb9010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelkoop TC, Korswagen HC. Development and migration of the C. elegans Q neuroblasts and their descendants. WormBook. 2014 Oct 15;:1–23. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.173.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelkoop TC, Williams L, Yang PT, Luchtenberg J, Betist MC, Ji N, van Oudenaarden A, Kenyon C, Korswagen HC. The thrombospondin repeat containing protein MIG-21 controls a left-right asymmetric Wnt signaling response in migrating C. elegans neuroblasts. Dev Biol. 2011 Oct 29;361(2):338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli J, Page AP, Hodgkin J. The C terminus of collagen SQT-3 has complex and essential functions in nematode collagen assembly. Genetics. 2006 Feb 1;172(4):2253–2267. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.053637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs ME, McWhirter RM, Unckless RL, Miller DM 3rd, Lundquist EA. Caenorhabditis elegans ETR-1/CELF has broad effects on the muscle cell transcriptome, including genes that regulate translation and neuroblast migration. BMC Genomics. 2022 Jan 6;23(1):13–13. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977 Mar 1;56(1):110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan L, Lundquist EA. Transmembrane proteins UNC-40/DCC, PTP-3/LAR, and MIG-21 control anterior-posterior neuroblast migration with left-right functional asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2012 Oct 10;192(4):1373–1388. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan L, Norris ML, Schöneich S, Ackley BD, Lundquist EA. The fat-like cadherin CDH-4 acts cell-non-autonomously in anterior-posterior neuroblast migration. Dev Biol. 2014 Jun 19;392(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]