Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers face burnout from high job demands and prolonged working conditions. While mental health services are available, barriers to access persist. Evidence suggests digital platforms can enhance accessibility. However, there is a lack of systematic reviews on the effectiveness of digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) for healthcare professionals. This review aims to synthesize evidence on DMHIs’ effectiveness in reducing burnout, their acceptability by users, and implementation lessons learned.

Method

This Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-guided review included 12 RCTs on DMHIs for healthcare professionals, published before 31 May 2024. The primary focus was on burnout, with secondary outcomes related to mental health and occupation. Quality appraisal used Cochrane risk of bias tools. A narrative synthesis explored DMHIs’ effectiveness, acceptability, utilization, and implementation lessons.

Results

Significant improvements in mental health outcomes were observed in 10 out of 16 RCTs. Burnout and its constructs showed significant improvement in five RCTs. Studies that measured the acceptability of the interventions reported good acceptability. Factors such as attrition, intervention design and duration, cultural sensitivities, flexibility and ease of use, and support availability were identified as key implementation considerations.

Conclusions

Web-based DMHIs positively impact burnout, mental health, and occupational outcomes among healthcare professionals, as shown in most RCTs. Future research should enhance DMHIs’ effectiveness and acceptability by addressing identified factors. Increasing awareness of DMHIs’ benefits will foster acceptance and positive attitudes. Lessons indicate that improving user engagement and effectiveness requires a multifaceted approach.

Keywords: Self-help digital mental health intervention, burnout, mental health outcomes, healthcare workers, systematic review

Introduction

Healthcare workers are at risk of poor mental health conditions due to high job demands and prolonged exposure to stressful working environments. 1 As a result, many of them developed occupational burnout, a syndrome caused by prolonged states of work-related stress and anxiety, which can predict various negative mental and physical health outcomes.2–5 Distress symptoms such as work-related stress, anxiety, and depression that occur together with burnout have significant impacts on healthcare employees’ lives and their job performance. 6 High levels of anxiety (40%), depression (37%), and distress (37%) among healthcare workers were commonly identified in the meta-analysis7,8 and other studies9–11 done during the COVID-19 pandemic. Strategies to give mental health support and treatment to healthcare professionals have been in place but the options were underutilized.12,13 The barriers to utilizing mental health support include time constraints, cost, privacy and confidentiality concerns, stigma, potential implications on a healthcare career, and exposure to unwanted interventions such as counselling and medications. 14 To mitigate the challenges in utilizing and meet the increasing demand for mental health support, various forms of internet-based or digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) have been introduced. 15

The wide prevalence of burnout among health professionals necessitates broader access to effective mental health interventions. Techniques such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), acceptance commitment therapy (ACT), emotionally focused therapy (EFT), mindfulness, and relaxation therapy are considered among the most popular and effective evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches. These interventions are typically delivered in traditional one-to-one or group settings with a trained therapist. 16 A method to widen access to them is the use of self-guided internet-based interventions, especially to provide care to difficult-to-reach and underserved populations. 17 The potential of self-guided programmes has long been studied well before the advent of the Internet as they provide innovative solutions to challenges such as the cost, stigma, and time constraints linked to classical face-to-face therapy. In addition, self-guided techniques can empower groups that would normally struggle to access classical psychotherapy services. 18 Public access to the internet and usage of digital platforms in the last three decades has expanded the breadth of psychotherapeutic methods, including self-guided and minimally guided therapy protocols. Available evidence suggests that self-guided psychotherapeutic techniques have a robust level of effectiveness, 19 although it has also been pointed out that evidence regarding self-guided therapy methods such as chatbots remains scant and inconclusive. 20 Similarly, evidence suggests that other digitally-based interventions with either full or minimal guidance by human therapists also provide levels of effectiveness comparable to traditional face-to-face settings for a variety of psychopathological disorders such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depressive disorder.21–23 Furthermore, past studies, evaluating the effectiveness of digital health interventions on various health-related outcomes, showed that digital health interventions positively impact health-related outcomes in the workplace.24,25

Despite the wealth of knowledge in digitally delivered psychotherapeutic techniques, several important questions remain in this field. First, there is contradictory evidence regarding the effectiveness of self-guided applications or chatbots used to improve mental health outcomes 20 as a main tool of choice to deliver fully self-guided psychotherapy. Second, although DMHIs are known to have beneficial effects on well-being, in particular in the context of mental health in work environments, there are areas for improvement in how the users receive and engage with it in this particular context. 26 One of the methods to improve the effectiveness of self-help DMHI is to evaluate users’ acceptability and attitudes toward various forms of DMHIs. Finally, although there is an abundance of literature assessing the effectiveness, acceptability, preference, and attitudes about various forms of DMHIs, a systematic review on randomized controlled trials of DMHIs among healthcare workers has yet to be published. A notable exception relates to systematic reviews of studies done during the COVID-19 pandemic, 27 which overall showed promising results regarding the use of DMHI. To address these outstanding questions, we report here a systematic review that aimed at synthesizing the evidence about the effectiveness, and acceptability of users, and lessons learned from the studies regarding the development and implementation of self-help DMHI for healthcare workers in improving burnout and mental health outcomes.

Methods

Design

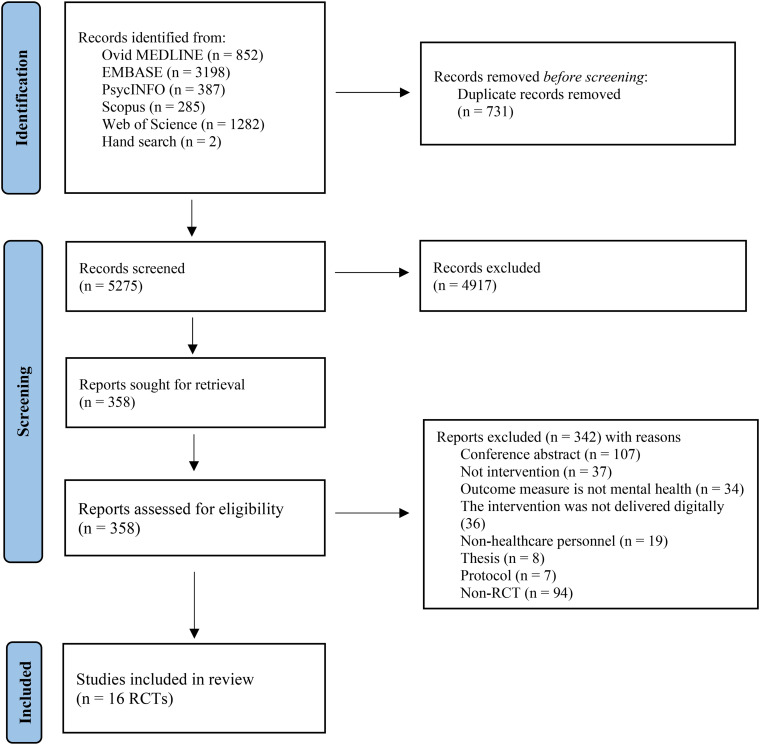

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were employed to conduct this systematic review on DMHIs among healthcare professionals as shown in Diagram 1 (see supplementary file 1 for PRISMA checklist). Prior to the data extraction process, the protocol was registered with PROSPERO (Record ID 240454). A qualitative synthesis was conducted for this narrative review after the records were screened for eligibility.

Diagram 1.

PRISMA guideline diagram showing the flow process for studies included in the systematic review.

Source: Adapted from: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Search strategies

Original articles and abstracts on mental health and self-help DMHIs were identified. A search was carried out on 31 May 2024 in Ovid Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus using a broad range of search terms based on MeSH indexing as well as free text terms. Databases were searched using a combination of keywords such as: ‘healthcare professionals’, ‘e-health’, ‘telemedicine’, and ‘mental health’ (see supplementary file 2 for the full list of search terms and supplementary file 3 for the search strategies). The terms were combined with ‘OR’ within the category and combined with ‘AND’ between categories. The search strategy was devised based on the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) concept. Eligibility criteria, described below, were screened for papers meeting the inclusion criteria. The search strategy was devised on Ovid Medline, which was then adapted for EMBASE and PsychINFO. The search was also done on Web of Science and Scopus.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included published randomized controlled trials that used methods such as parallel randomization, cluster randomization, individual randomization, and stratified randomization. The population of interest included any healthcare professionals, doctors, nurses, and allied healthcare workers, who received mental health interventions delivered digitally through email, website, application, or social media viewable on a computer, tablet, or smartphone to improve mental health outcomes. The articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals up to 31 May 2024 were included in the study. The primary outcomes were mental health-related outcomes, such as burnout, stress, anxiety, depression, and mental well-being. As secondary outcomes, job-related outcomes were included and covered mostly work functioning, job satisfaction, patient experience, work engagement, relationships with colleagues, and work-life balance. Due to the variation of procedures and outcome measures employed throughout each of the articles, narrative synthesis was conducted.

Identification

Titles and abstracts from initial searches based on inclusion and exclusion criteria were screened independently by reviewer 1 (LMA) and reviewer 2 (TMM). Both reviewers also did the abstract and full-text screenings. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by consulting with the third reviewer (TTS).

Data extraction

The data extraction process was carried out by two independent researchers (LMA and TMM). It is then followed by a quality appraisal process. From the 16 studies selected, the following information was extracted: author (year), location of the intervention, study design, year of enrolment, duration, follow-up frequency, participants, sample size, type of interventions, control methods, outcomes, findings, and implementation lessons learned.

Risk of bias assessment

Quality appraisal was done by two researchers (LMA and TMM) independently first using Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool version (2), RoB 2 (2019 version), for individual and parallel randomized controlled trials and new RoB 2 for cluster-randomized trials (2021 version). The ‘Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias’ tool 28 measures the risk of bias, with items judged as a low, high, or unclear risk for the included studies that adopt a randomized design. Bias is assessed as a judgement (high, low, or unclear) for individual studies from five domains including selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting), and other (any important concerns about bias not already discussed).

Results

Search results

The process of studies included in this review is described in Diagram 1. A total of 6006 articles were identified from five databases and hand searches. No eligible article was identified by manually searching the references of the selected articles. After removing 731 duplicates, 5275 research articles were selected for initial screening. Further 4917 titles and abstracts were excluded if they did not meet the eligibility criteria and 358 records were left for retrieval. Further, 342 out of 358 were excluded, the reasons being conference abstracts (n = 107), non-intervention studies (n = 37), the outcome measure was not mental health (n = 34), the intervention was not delivered digitally (n = 36), the target population was non-healthcare personnel (n = 19), thesis reports (n = 8), protocol (n = 7), and non-randomized controlled trials (n = 94) were removed as well. Overall, a total of 16 randomized controlled trials were selected for the review.

Quality assessment

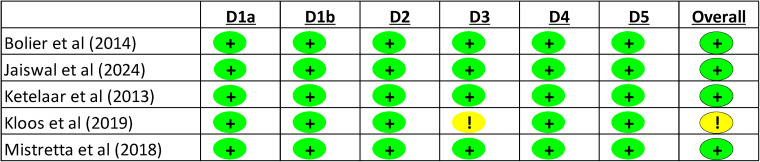

Results from Figure 1 show that all cluster randomized studies were identified as low risk for the domains that measure the randomization process, and the timing of identification or recruitment of participants. The domain that assessed the deviations from the intended interventions was also evaluated as low risk for all five studies. The domain of missing outcome data was judged as having a low risk of bias in four studies, while it was rated as having some concerns of risk in Kloos et al. 29 study.

Figure 1.

Risk of bias check for cluster randomized trials.

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias for the rest of the studies, which used parallel randomization, stratified randomization, block randomization, and individual randomization. The risks were measured using the RoB 2 version. It was found that the studies have a low risk of bias in all domains except two. Adair et al. 30 have some concerns about the risk of randomization and Congiusta et al. 31 have a high risk of bias for missing outcome data.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias check for individual or parallel randomized trials.

Results on outcomes

The description of authors and country, randomization methods, year of the conduct of the trial, recruited participants and sample size have been presented in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the review articles.

| Author study and country | Randomization method | Year of enrolment | Participants | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adair et al., 30 United States | Parallel randomization | 2018 | Healthcare workers |

N = 277 Self-focused condition group = 139 Other-focused condition group = 138 |

| Barrett et al., 32 Ireland | Parallel randomization | Not available | Social and healthcare professionals |

N = 42 ACT group = 22 CBT group = 20 |

| Bhardwaj et al., 33 India | Parallel randomization | 2021-2022 | Healthcare professionals | N = 98 Intervention = 47 Control = 47 |

| Bolier et al., 34 Netherlands | Cluster randomization | 2014 | Nurses, allied health professionals such as physiotherapists and radiotherapists |

N = 1140 Intervention = 579 Control = 567 |

| Congiusta et al., 31 United States | Stratified randomization | 2015 | Physicians from 4 clinical disciplines |

N = 63 Intervention = 30 Control = 33 |

| Dincer and Inangil, 35 Turkey | Individual randomization | 2020 | Nurses caring for COVID-19 patients |

N = 72 Intervention = 35 Control = 37 |

| Dyrbye et al., 36 Minnesota, USA | Stratified randomization | 2012 | Physicians in the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine |

N = 290 Intervention = 145 Control = 145 |

| Fiol-DeRoque et al., 37 Spain | Parallel randomization | 2020 | Healthcare workers who had provided health services to the patients with COVID-19 |

N = 482 Intervention = 248 Control = 234 |

| Ghawadra et al., 44 Malaysia | Stratified randomization | Not available | Nurses with mild or moderate levels of stress, anxiety, or depression |

N = 249 Intervention = 123 Control = 126 |

| Hersch et al., 38 Virginia, New York, USA | Block randomization | 2014 | Nurses |

N = 104 Intervention = 52 Control = 52 |

| Jaiswal et al., 39 USA | Cluster randomization | 2021-2022 | Healthcare professionals |

N = 43 Intervention = 22 Control = 21 |

| Ketelaar et al., 40 Netherlands | Cluster randomization | Not available | Nurses and allied health professionals | N = 1140 |

| Kloos et al., 29 Netherlands | Cluster randomization | 2015 | Nursing staff in nursing homes |

N = 128 Intervention = 79 Control = 49 |

| Mistretta et al., 41 Arizona, USA | Cluster randomization | Not available | Employees at the Mayo Clinic |

N = 60 MBRT group = 22 Smartphone resilience intervention app group = 23 Control = 15 |

| Smoktunowicz et al., 42 Poland | Blocked randomization | 2018 | Physicians, nurses, dentists, physiotherapists, midwives, paramedics, others |

N = 1240 Condition 1 = 311 Condition 2 = 311 Condition 3 = 309 Condition 4 = 309 |

| Xu et al., 43 Australia | Parallel randomization | 2019-2020 | Healthcare professionals from the emergency department |

N = 148 Intervention = 74 Control = 74 |

Note. ACT = acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT = Cognitive behavioral therapy; MBRT = mindfulness-based resilience training.

Studies were conducted in nine different countries. Six studies were conducted in the United States of America, while the remaining were conducted in Australia, Ireland, India, the Netherlands, Malaysia, Poland, Spain, and Turkey.

Five out of 16 studies utilized parallel randomization. Five studies utilized clustered randomization, three studies used stratified randomization, and two studies used blocked randomization.

The year of enrolment into the studies varied from as early as 2012 to the latest one 2022.

Four studies focused on nurses while one study conducted the intervention among physicians only. The rest of the studies performed their interventions on various healthcare professionals such as allied health professionals and healthcare workers. The sample size varied from 42 to 1240 in studies included in this review.

Table 2 describes the details of the DMHI used as well as the main methodological features of each study. The length of the interventions ranged from a single session of 20 min to 24 weeks. The types of intervention are also described in detail in Table 2 There are variations in the types of interventions used in these studies however all used clinically proven psychotherapeutic methods such as gratitude letter writing, ACT and CBT, relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and EFT. In most studies, mobile applications and websites were used for delivering the intervention. Three studies used email to send the intervention via links and two studies used video calls for the online delivery of instructions and demonstrations. The level of self-guidance can be seen in two forms, fully self-guided or partially self-guided with the therapist-assisted in the intervention.

Table 2.

Description of type of intervention and control groups.

| Authors’ study and country | Duration/length of the intervention | Types of intervention | Level of self-guidance | Method of delivery of the intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adair et al., 30 United States | 1 session, 1 week | Seven minutes of gratitude letter writing (self-focus condition or other-focus condition) in the text box provided on the website. | Fully self-guided intervention | The one-time prompt email was sent to the participants at baseline and 1 week later. | Active control group |

| Barrett et al., 32 Ireland | 3 sessions, 2 weeks | Stress management programme (ACT or CBT) built on two separate websites. | Fully self-guided | The links to two separate websites for interventions were emailed to the participants. The interventions were delivered via the on-screen text instructions | Active control group |

| Bhardwaj et al., 33 India | 12 weeks | Yoga-based meditation and breath intervention | Trained instructors guided online sessions | via online video conferencing application ‘Zoom’ – practice at home with online assistance provided | Wait-list control group |

| Bolier et al., 34 Netherlands | 2 weeks for each module | Self-help workers’ health surveillance module combined with automated personalized feedback and online intervention group. The modules based on cognitive behavioural therapy, are offered. | Fully self-help/self-guided | The links to the assessment questionnaire, intervention, and personalized feedback on the website were emailed to the participants | Wait-list control group |

| Congiusta et al., 31 United States | 24 weeks | Learn-Do-Share online physician training curriculum which combines a set of web-based learning modules with coaching tips to promote a patient-centered experience | Self-guided online modules with biweekly conference calls among the participating physicians to share experiences. | The links to the bundles were assigned to the participants through weekly emails. | No treatment control group |

| Dincer and Inangil, 35 Turkey | A single session of 20 min | Single online EFT the basic principle of which is to send activating and deactivating signals to the brain by stimulating points on the skin that have distinctive electrical properties, usually by tapping on them. | Guided online by a person certified in EFT. | Online video call delivery of EFT by a person certified in EFT. The instructor taught and demonstrated to participants the steps of EFT during the online session. | No treatment control group |

| Dyrbye et al., 36 Minnesota, USA | Once a week for 10 weeks | Electronic delivery of 5-6 self-directed micro-tasks consisted of 6 themes crafted for physicians. The themes were intentionally designed to cultivate professional satisfaction and well-being. | Fully self-guided | The link to the intervention and survey assessment was emailed to the participants. The tasks were delivered once a week. | No treatment control group |

| Fiol-DeRoque et al., 37 Spain | 2 weeks | Intervention group: Self-managed and self-guided psychoeducational mobile-based intervention. Contents include CBT, and mindfulness approaches, which were written and audio-visual contents. Control group: Written information about the mental health care of the healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic was provided through the same mobile application. |

Full self-guided | The participants were instructed to download the mobile application after thorough instructions were given via telephone call. | Active control group |

| Ghawadra et al., 44 Malaysia | 2 h workshop followed by 4 weeks of self-practice guided by a website | Mindfulness-based training: 2 h of mindfulness training workshop followed by 4 weeks of guided self-practice mindfulness-based training on the website | Partial self-guided since a workshop was given before self-guided practice. | The participants were given a code number to create a user account. The website provides a detailed explanation of the exercises and guidance. Reminders were sent to the participants via the WhatsApp intervention group. |

Wait-list control group |

| Hersch et al., 38 Virginia, New York, USA | The intervention was made available for 3 months | Web-based BREATHE cognitive behavioural therapy with relaxation techniques: Stress management programme which consists of seven modules for the nurses and eight modules for nurses’ managers. | Fully self-guided | The link to the website was emailed to the participants. Participants are to complete the modules over 3 months period. Reminder emails to use the program, to answer the second and post-test questionnaires. | Wait-list control group |

| Jaiswal et al., 39 USA | 3 months | Digital WellMind | Fully self-guided | Participants installed the mobile application and research team followed up via periodic emails once every 2 weeks. | No treatment control group |

| Ketelaar et al., 40 Netherlands | Self-help e-Mental health intervention (EMH) developed based on cognitive behavioural therapy and combine a variety of aspect, e.g., providing information and advice, weekly assignments, the option of keeping a diary, and a forum to get in contact with others who have similar complaints. | Fully self-help | The link to the self-help EMH website was emailed to the participants. Weekly assignments and interactions took place online | Wait-list control group | |

| Kloos et al., 29 Netherlands | 1 lesson per week over eight weeks | 8-week online positive psychology intervention ‘This is Your Life’ consists of eight modules that cover six key topics of well-being: The modules consist of psychoeducation and evidence-based positive psychology exercises. |

Fully self-guided | Face-to-face induction was conducted before the online gamified intervention. Participants used website manuals and login codes to follow the intervention individually at home. | No treatment control group |

| Mistretta et al., 41 Arizona, USA | 6 weekly 120 min MBRT sessions; 6-week trial for smartphone; 3 months | Group 1: 6 weeks of personal mindfulness-based resilience training (MBRT) which incorporates acceptance commitment therapy and mindful-based stress reduction therapy. Group 2: a resiliency-based self-help smartphone intervention |

Psychologist in-person intervention vs self-guided | MBRT sessions were delivered by a clinical psychologist/developer. Participants in smartphone intervention were prompted every 7–10 days with one of four possible topics that they wanted to focus on for the next week. |

Wait-list control group |

| Smoktunowicz et al., 42 Poland | Over 6 weeks for experimental conditions and over 3 weeks for active controls. | Experimental Conditions via Med-stress self-guided internet intervention on website Condition 1 = SE + SS Condition 2 = SS + SE Obligatory modules SE = self-efficacy enhancement module SS = perceived social support enhancement module Optional modules Relaxation Mindfulness Cognitive restructuring Lifestyle |

Fully self-tailor and self-guided | Participants were directed to the Med-stress web-based activities via emails | Active control condition Condition 3 = SE Condition 4 = SS |

| Xu et al., 43 Australia | 4 weeks | Guided mindfulness meditation delivered over a smartphone application | Fully self-guided | 60 Guided mindfulness meditation sessions were made available on the commercially available application which was provided to the participants in the intervention group free-of-charge. | Wait-list control group |

Note. ACT = acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; EFT = emotional freedom techniques; EMH = e-Mental health; BREATHE = Stress Management for Nurses program; MBRT = mindfulness-based resilience training; SE = self-efficacy enhancement module; SS = perceived social support enhancement mod.

The summary of the result findings on Burnout and mental health outcomes after using digital platforms to deliver mental health therapies or psychotherapeutic techniques are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Table summary of studies which have significant improvement in burnout.

| Burnout | Significant improvement between the intervention and control groups | Significant improvement within the intervention groups over time |

|---|---|---|

| Burnout | — | Barrett et al. 32 ; Dincer and Inangil 35 |

| Emotional Exhaustion subscale | Bhardwaj et al. 33 | Adair et al. 30 ; Xu et al. 43 |

| Depersonalization subscale | Bhardwaj et al. 33 | Congiusta et al. 31 ; Xu et al. 43 |

| Personal achievement subscale | Bhardwaj et al. 33 | Congiusta et al. 31 ; Xu et al. 43 |

Table 4.

Table summary of studies which have significant improvement in other mental health outcomes.

| Mental Health Outcomes | Significant improvement between the groups | Significant improvement within the intervention groups over time |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Ghawadra et al. 44 | Dincer and Inangil 35 ; Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 ; Ghawadra et al. 44 |

| Compassion for others | — | — |

| Coping with stress | — | — |

| Depression | — | Ghawadra et al. 44 |

| Fatigue | — | Dyrbye et al. 36 |

| Mental health symptoms | Bolier et al. 34 | Barrett et al. 32 |

| Mindfulness | — | Ghawadra et al. 44 ; Mistretta et al. 39 ; Mistretta et al. 43 |

| Perceived stress/stress | Hersch et al.38,; Smoktunowic et al. 42 | Barrett et al. 32 ; Dincer and Inangil35,; Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 ; Ghawadra et al. 44 ; Xu et al. 43 |

| Psychological flexibility | — | — |

| Quality of life | Bhardwaj et al. 33 | Dyrbye et al. 36 |

| Self-compassion | — | Mistretta et al. 39 ; Jaiswal et al. 41 |

| Self-reported mental health | — | — |

| Sleep monitoring/Insomnia | — | Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 |

| Social well-being | Bolier et al. 34 | — |

| Subjective happiness | — | Adair et al. 30 |

| Substance and alcohol use | — | — |

| Symptoms of distress | — | Dincer and Inangil 35 |

| Well-being | Bolier et al. 34 | Dyrbye et al. 36 ; Mistretta et al. 41 ; Xu et al. 43 |

Burnout

Out of 16 studies, five studies examined the effectiveness of using digital platforms on improving burnout. Specifically, two studies, Barrett et al. 32 and Dincer and Inangil 35 , demonstrated a significant improvement in overall burnout scores within the intervention groups over time. However, there was no significant difference observed between groups. Additionally, while overall burnout did not exhibit significant improvement in other studies, two separate studies by Adair et al. 30 and Congiusta et al. 31 did report significant enhancements in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement subscales over time within the group. Significant improvements in subscales of burnout such as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement were identified by Bhardwaj et al. 33 in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Mental health outcomes

Regarding various mental health outcomes, significant findings have been observed across a spectrum of measures in nine studies, as outlined in Table 4. Anxiety, 44 mental health symptoms, 34 stress,38,42 quality of life, 33 social well-being, 34 and overall well-being 34 were significantly improved in the intervention groups that received DMHIs compared to the control groups.

Significant improvements were also identified in the experimental groups that received digital interventions over time within the intervention group for anxiety,35,37,44 depression, 44 fatigue, 36 mental health symptoms, 32 mindfulness,39,43,44 stress,32,35,37,43,44 quality of life, 36 self-compassion,39,41 subjective happiness, 30 symptoms of distress 35 and overall well-being.36,41,43

Job-related outcomes

Table 5 presents job-related outcomes, highlighting significant findings in job satisfaction, patient experience, work engagement, and work-life balance across six studies. It was found that job satisfaction, 44 patient experience 31 and work engagement 42 were improved significantly in the experiment groups with digital intervention. Significant improvements in the experiment groups over time are found for job satisfaction,29,44 patient experience 31 and work-life balance. 30

Table 5.

Table summary of studies which have significant improvement in other job-related outcomes.

| Job-related outcomes | Significant improvement between the groups | Significant improvement within the intervention groups over time |

|---|---|---|

| Impaired work functioning | ||

| Job satisfaction | Ghawadra et al. 44 | Ghawadra et al. 44 ; Kloos et al. 29 |

| Patient experience | Congiusta et al. 31 | Congiusta et al. 31 |

| Professional satisfaction | — | — |

| Relationship quality | — | — |

| Work engagement | Smoktunowicz et al. 42 | |

| Work limitations | — | — |

| Work-life balance | — | Adair et al. 30 |

Acceptability and utilization

Seven studies in this review measured the acceptability and utilization of the online intervention by the participants as described in Table 6. The acceptability of the intervention was measured by Kloos et al., 29 where a fully self-guided gamified online intervention was delivered to the participants over eight weeks. The measurement from this study reported that participants in their study moderately accepted the 8-week online course. Participants from Ref. 30 , who received gratitude letters writing on the website, were assessed as having higher engagement. With regards to utilization, improved mental health outcome was observed, which included engaging exercises, such as self-efficacy enhancing modules, in the intervention group.42,43 Hersch et al. 38 reported that the majority of the participants logged into the programme 2.5 times on average but there were those who never did, and their engagement time was about 43 min. His study identified that a greater reduction in stress was observed among the participants who spent more time utilising intervention. Participants from the study done by Barrett et al., 32 where a full-self-guided stress management programme was delivered via websites, reported that the materials used in the online intervention were useful and easy to understand which was translated as acceptable.

Table 6.

Acceptability and utilization.

| Acceptability and utilization | Authors’ study | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability of intervention | Kloos et al. 29 |

|

| Tool engagement and utilization | Adair et al. 30 |

|

| Intervention usage | Smoktunowicz et al. 42 |

|

| Xu et al. 43 |

|

|

| Programme utilisation | Hersch et al. 38 |

|

| Helpfulness | Barrett et al. 32 |

|

| Usability | Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 | The participants perceived that PsyCovidApp was highly usable. After the trial, 94.1% of participants in the intervention group asked the research team if they could regain access to the PsyCovidApp intervention. |

Lessons learned from implementation

In our review of the implementation lessons learned, we searched all studies for narratives described under their limitation subsections. From these narratives, we synthesized and categorized the barriers and facilitators that impacted the effectiveness of the interventions as seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Implementation lessons learned.

| Categories | Barriers | Authors’ study |

|---|---|---|

| Summary of implementation lessons learned (barriers) | ||

| Intervention design and implementation | Component Effects: Difficulty in disentangling the effects of individual components when both groups receive interventions. | Adair et al. 30 ; Barrett et al. 32 |

| Inadequate Duration: Brief intervention periods insufficient for significant changes. | Barrett et al. 32 ; Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 | |

| Complexity and Choice: Excessive options leading to lower motivation and engagement. | Bolier et al. 34 | |

| Participant engagement and attrition | High Attrition Rates: High dropout rates, especially in younger participants and those without follow-up support. | Adair et al. 30 ; Barrett et al. 32 ; Bolier et al. 34 ; Smoktunowic et al. 42 ; Xu et al. 43 |

| Lack of Support: Online interventions lacking therapist availability contributing to attrition. | Bolier et al. 34 ; | |

| Technical Skills: Problems with technical skills hindering participant engagement. | Ketelaar et al. 40 ; | |

| Low Utilization: Low program utilization diluting observed differences between groups. | Hersch et al. 38 ; Ketelaar et al. 40 ; | |

| Bias and blinding issues | Expectation Bias: Placebo effects and differences in expectations influencing outcomes. | Adair et al. 30 ; Jaiswal et al. 39 |

| Hawthorne Effect: Changes due to participants’ awareness of being studied rather than the intervention itself. | Bhardwaj et al. 33 ; Dyrbye et al. 36 | |

| Self-Selection Bias: Self-selection and self-reporting leading to inherent biases. | Xu et al. 43 | |

| Measurement and monitoring | Follow-up Issues: Participants failing to complete follow-up assessments and tasks. | Adair et al. 30 |

| Insufficient Follow-up Period: Short follow-up periods insufficient to detect clinically meaningful differences. | Fiol-DeRoque 37 | |

| Monitoring Difficulties: Challenges in monitoring participants’ adherence and practice. | Ghawadra et al. 44 | |

| Context and generalizability | Generalizability: Limited generalizability due to specific healthcare settings and participant demographics. | Mistretta et al. 41 |

| Relevance to Work Context: Intervention content not always applicable to the participants’ work context. | Kloos et al. 29 | |

| Cultural Acceptance: High dropout rates in regions where digital interventions are less common. | Smoktunowic 42 | |

| Study design and conduct | Sample Size: Small sample sizes limiting the ability to generalize findings. | Hersch et al. 38 |

| Participant Blinding: Lack of blinding contributing to biases in outcomes. | Jaiswal et al. 39 | |

| Baseline Values: High baseline values possibly due to participants’ concerns about anonymity. | Kloos et al. 29 | |

| Summary of implementation lessons learned (facilitators) | ||

| Flexibility and accessibility | mHealth Interventions: Mobile health interventions enabling participants to incorporate them into busy schedules. | Bhardwaj et al. 33 |

| Short Sessions: Shorter, flexible sessions increasing accessibility and engagement. | Jaiswal et al. 39 | |

| Ease of use | Simple Procedures: Simple and easy flow of procedures suitable for prescription purposes. | Bhardwaj et al. 33 |

| Concise Content: Concise video fragments improving user engagement. | Kloos et al. 29 | |

| Support and guidance | Professional Guidance: Guidance from healthcare professionals or psychologists improving adherence and effectiveness. Face-to-Face Workshops: Prior face-to-face workshops reducing dropout rates and enhancing engagement. |

Kloos et al. 29 ; Ghawadra et al. 44 |

| Positive outcomes and engagement | Longer Interventions: Longer intervention periods associated with greater improvements in outcomes. | Bhardwaj et al. 33 ; Dybye et al. 36 |

| Personalization: Tailored interventions more valued by participants, such as those delivered before the end of the workday allowing early leave. | Mistretta et al. 41 | |

| Monitoring and feedback | Blinding and Reduction of Bias: Blinding participants, outcome assessors, and data analysts reducing biases. | Bhardwaj et al. 33 ; Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 |

| Data Collection: Collecting patient experience data during and after interventions for comprehensive feedback. | Congiusta et al. 31 | |

| Cultural and contextual adaptation | Contextual Relevance: Adapting intervention content to be more relevant to participants’ work contexts. | Kloos et al. 29 |

| Cultural Sensitivity: Addressing cultural acceptance to improve engagement in regions where digital interventions are less common. | Smoktunowic et al. 42 | |

Barriers identified

1. Intervention Design and Implementation

Barriers related to intervention design and implementation were prominent. Studies, by Adair et al. 30 and Barrett et al., 32 noted that the effects of intervention components were influenced by both study groups receiving the intervention. Furthermore, Barrett et al. 32 and Fiol-DeRoque et al., 37 highlighted the inadequacy of the intervention duration, which was insufficient to produce meaningful outcomes. Bolier et al. 34 pointed out that the complexity and variety of intervention options also posed significant challenges.

2. Participant Engagement and Attrition

High attrition rates emerged as a major barrier, particularly among younger participants and those without follow-up, as observed by Adair et al., 30 Barrett et al., 32 Bolier et al., 34 Smoktunowicz et al., 42 and Xu et al. 43 The lack of therapist support further exacerbated this issue. 34 Additionally, participants’ technical skill deficiencies 40 and low intervention utilization diluted the observed differences between groups.38,40

3. Bias and Blinding Issues

Bias and blinding issues were significant barriers. Expectation bias due to placebo effects was noted by Adair et al. 30 and Jaiswal et al. 39 The Hawthorne effect, where participants’ awareness of being studied influenced their behaviours, was reported by Bhardwaj et al. 33 and Dyrbye et al. 36 Self-selection bias arising from self-selection and self-reporting was another critical barrier highlighted by Xu et al. 43

4. Measurement and Monitoring

Challenges in measurement and monitoring included follow-up issues 30 and insufficient follow-up periods that impacted the production of clinically meaningful differences. 37 Monitoring difficulties due to participants’ adherence and practice were also problematic. 44

5. Context and Generalizability

Contextual factors and generalizability of findings were major concerns. Mistretta et al. 41 pointed out that findings were often limited to specific healthcare settings and participant demographics. The relevance of intervention content to the work context was questioned by Kloos et al., 29 while Smoktunowicz et al. 42 noted cultural acceptance issues in settings where digital interventions were less common.

6. Study Design and Conduct

Study design and conduct issues included small sample sizes limiting the generalizability of findings 38 and lack of blinding contributing to biases in outcomes. 39 High baseline values, possibly due to participants’ concerns about anonymity, were noted by Kloos et al. 29

Facilitators identified

1. Flexibility and Accessibility

Facilitators enhancing flexibility and accessibility were highlighted by Bhardwaj et al., 33 who noted that the flexible nature of mobile health interventions allowed participants to incorporate them into their busy schedules. Jaiswal et al. 39 found that short intervention sessions increased participant engagement.

2. Ease of Use

Interventions that were simple and easy to follow significantly facilitated participation. Bhardwaj et al. 33 emphasized the importance of a straightforward procedure for self-guided interventions and concise video content that improved user engagement.

3. Support and Guidance

Professional guidance emerged as a critical facilitator for improving adherence and effectiveness, as reported by Kloos et al. 29 and Ghawadra et al. 44 The provision of face-to-face workshops prior to the intervention also proved beneficial.29,44

4. Positive Outcomes and Engagement

Longer intervention periods were associated with greater improvements in outcomes, as highlighted by Bhardwaj et al. 33 and Dyrbye et al. 36 Mistretta et al. 41 found that tailored or personalized interventions were particularly valued by participants.

5. Monitoring and Feedback

Effective monitoring and feedback mechanisms were essential facilitators. Bhardwaj et al., 33 and Fiol-DeRoque et al. 37 , emphasized the importance of blinding participants to reduce bias, while, 31 noted the value of comprehensive data collection during and after the intervention.

6. Cultural and Contextual Adaptation

Cultural and contextual adaptation of interventions played a significant role in enhancing engagement, Kloos et al. 29 and Smoktunowicz et al., 42 highlighted the importance of ensuring contextual relevance and cultural sensitivity of interventions to improve engagement in digital interventions.

In summary, understanding and addressing these barriers and facilitators can inform the design and implementation of future interventions, enhancing their effectiveness and sustainability in diverse settings.

Discussion

The goal of this systematic review was to synthesize the evidence on the effectiveness in improving burnout and other mental health-related and job-related outcomes, user acceptability, and lessons learned implementation of self-help DMHI for healthcare workers. A total of 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were identified which met the eligible criteria. The RCTs included in this study covered a broad range of digital interventions and mental health outcomes, which is the reason why a narrative synthesis was carried out and a meta-analysis was not performed in this study.

Overall, significant improvements in burnout, anxiety, mental health symptoms, stress, quality of life, social well-being, general well-being, job satisfaction, patient experience, and work engagement were observed among participants in the intervention groups that used DMHIs compared to the control groups. Even though some studies in this review do not show significant improvement between intervention and control groups, they demonstrate significant positive effects on mental health outcomes over time within the intervention groups. They are overall burnout, all three subscales of burnout, anxiety, depression, fatigue, mental health symptoms, mindfulness, stress, quality of life, self-compassion, sleep, subjective happiness, symptoms of distress, general well-being, job satisfaction, patient experience, and work-life balance. These findings are consistent with the results from other systematic reviews where they concluded that the use of DMHIs has a positive impact on health and occupational-related outcomes.25,26 However, Abd-Alrazaq et al. 45 found that there is still insufficient evidence to prove the effectiveness and safety, and recommended that further studies are required to draw solid conclusions that their effect is clinically important.

Studies assessing DMHIs found them acceptable and useful.29,32 This aligns with the study by Apolinário-Hagen et al., 46 though they noted these are not equivalent to face-to-face therapies. Conversely, Musiat et al. 47 reported negative views on computerized self-help, likely contributing to high attrition rates seen in some RCTs, as user engagement correlates with acceptability. 48 Three studies also linked utilization to positive outcomes, indicating that designing highly acceptable digital platforms is essential for improving user engagement and utilization.

The interventions varied in content, duration, delivery method, sample size, participant characteristics, and outcome measurements. This variability highlights the need for future researchers to identify factors critical for effective interventions. Future studies should focus on standardizing these variables, customizing interventions to meet diverse population needs, and conducting long-term longitudinal studies to gather evidence and recommendations for the sustainability, adherence, and success of interventions. 49

Factors such as effects of intervention components, the inadequacy of intervention duration, high attrition, bias and blinding issues, challenges in measurements of outcomes and monitoring, and generalizability are identified as barriers that impacted the effectiveness of the interventions. They give researchers an insight into the challenges required to overcome in designing, developing, and implementing future studies alike. High attrition is an issue in most of the studies included in this review, and the reasons are lack of professional support and poor technical skills. Given the busy nature of healthcare professionals’ work, developing a mobile phone application that is compatible with any operating system so that users can use it anytime anywhere, 33 creating short and simple content that is easy for the user to follow,33,39 and tailoring the digital content to the needs and culture29,42 of the healthcare professionals are recommended. Moreover, including features such as links to professional support, scheduling appointments through apps, notifications feature that can be customized, and eventually monitoring of progress and feedback option would give the users the channels to personalize the digital mental health service according to their needs.

Careful consideration of the intervention design, the effects of blinding, and the duration of the intervention is critical for successful implementation, as highlighted by the authors of the RCTs being reviewed. The placebo and Hawthorne effects should be considered in the study design. For instance, in RCTs lacking no-treatment control groups,30,32 these effects may have influenced outcomes, as participants were aware of their interventions. This can be addressed by including a wait-list control group34,38,44 or a no-treatment control group.29,31,35,36 Although this may potentially introduce expectation or self-selection bias, 50 recommended an active control group with a dummy intervention can be used to mitigate these biases.

Barrett et al. 32 , highlighted that a shorter intervention duration negatively impacts the ability to observe significant positive changes, contradicting studies that found significant outcomes with brief interventions.30,32,43 Dyrbye et al. 36 suggested that insignificant results may be due to an inadequate dose or frequency of the intervention.

Lastly, the results indicate that both psychotherapist-delivered and self-guided digital interventions, whether online or face-to-face, 32 were similarly effective in reducing the negative consequences of occupational stress. Even though this might be true for other studies such as Refs.,31,33,34,38,42,44 the results from healthcare workers using digital interventions are not significant in Refs.36,40,41 Even though more and more studies have proven the effectiveness of DMHIs, it is also critical to consider that digital interventions are not for everyone. For instance, due to the self-guided nature of the intervention, the trials are carried out among participants with mild or no mental health symptoms at baseline, hence, the changes measured in such studies might not be considered clinically significant since many studies missed the potential larger portion of participants who needs this care. Another consideration is that not all participants may feel comfortable using this service through a digital platform, as it requires a certain level of digital literacy. 51

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Two studies in this review are considered to have some concerns and another one is identified as having high risk after quality appraisal. These findings were attributed to having risks in the domains that appraise the randomization process, and the missing outcome data. Consequently, the generalizability of the results from these studies is questionable. The review focuses on diverse methods of delivery of mental health care via digital platforms and meta-analyse was not possible as a result of this. It is recommended to take the results from this synthesis with caution since the narrative syntheses can be biased which has an impact on the credibility of the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is observed that the effectiveness of web-based or online DMHIs is proven to be positive in improving mental health outcomes such as burnout, anxiety, stress, mental health symptoms, social and general well-being, and mental health symptoms among healthcare professionals. Insight from valuable lessons learned indicates that improving user engagement and the effectiveness of DMHIs requires a multifaceted approach. It is essential to design content that is short, simple, and concise, specifically tailored for healthcare professionals. This approach ensures that the material is easily digestible and directly relevant to their needs. Furthermore, providing access to professional guidance through the digital platform enhances the support and reliability of the intervention. Lastly, adapting the intervention content to align more closely with the user's work contexts and cultural backgrounds ensures greater relevance and resonance, ultimately fostering better engagement and sustained use.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH

Footnotes

Contributorship: Min Tan, Tin Su and Pascal Geldsetzer developed the review protocol; Lwin Aye and Min Tan conducted the screening independently; Lwin Aye wrote the manuscript; Tin Su, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus and Alexandre Schaefer planned the study. Tin Su, Pascal Geldsetzer, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Lay Soon, Till Bärnighausen, Ulrich Reininghaus and Lwin Aye led in revising the manuscripts. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, results and manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting of Interest: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All authors confirm that they have no competing financial or personal interests that may inappropriately influence this research work.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The publication fee for this research was supported by Institute for Research, Development and Innovation, IMU University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The institution had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study. The authors declare no competing interest.

Guarantor: Tin Su, who is the principal investigator of the project.

Informed Consent: Since this study is a systematic review, consent from the participants is unnecessary.

ORCID iD: Lwin M. Aye https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4400-1593

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alrawashdeh HM, Al-Tammemi AB, Alzawahreh M, et al. Occupational burnout and job satisfaction among physicians in times of COVID-19 crisis: a convergent parallel mixed-method study. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C. Burnout, psychology of. In: Wright JD. (ed) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 2015, pp.929–932. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080970868260091 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raudenská J, Steinerová V, Javůrková A, et al. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2020; 34: 553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabagh Z, Hall NC, Saroyan A. Antecedents, correlates and consequences of faculty burnout. Educ Res 2018; 60: 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yates SW. Physician stress and burnout. Am J Med 2020; 133: 160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marvaldi M, Mallet J, Dubertret C, et al. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021; 126: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saragih ID, Tonapa SI, Saragih IS, et al. Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 121: 104002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acar Sevinc S, Metin S, Balta Basi N, et al. Anxiety and burnout in anesthetists and intensive care unit nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Anesthesiol 2022; 72: 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saijo Y, Chiba S, Yoshioka E, et al. Job stress and burnout among urban and rural hospital physicians in Japan. Aust J Rural Health 2013; 21: 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zakaria MI, Remeli R, Ahmad Shahamir MF, et al. Assessment of burnout among emergency medicine healthcare workers in a teaching hospital in Malaysia during COVID-19 pandemic. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 2021; 28: 254–259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, et al. Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: a prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ 2010; 2: 210–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyssen R, Røvik JO, Vaglum P, et al. Help-seeking for mental health problems among young physicians: is it the most ill that seeks help? - A longitudinal and nationwide study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004; 39: 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givens JL, Tjia J. Depressed medical students’ use of mental health services and barriers to use. Acad Med 2002; 77: 918–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollis C, Morriss R, Martin J, et al. Technological innovations in mental healthcare: harnessing the digital revolution. Br J Psychiatry 2015; 206: 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: basics and beyond, 3rd ed. New York, USA: Guilford Publications, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanna M, Rose R. Digital interventions in mental health: reviews and recommendations for application in clinical practice and supervision. Cogn Behav Pract 2021; 29: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs MK, Goodman G. Psychology and self-help groups. Predictions on a partnership. Am Psychol 1989; 44: 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dear BF, Staples LG, Terides MD, et al. Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord 2015; 36: 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abd-Alrazaq A, Safi Z, Alajlani M, et al. Technical metrics used to evaluate health care chatbots: scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2020a; 22: e18301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Titov Net al. et al. Internet interventions for adults with anxiety and mood disorders: a narrative umbrella review of recent meta-analyses. Can J Psychiatry 2019; 64: 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlbring P, Andersson G, Cuijpers P, et al. Internet-based vs. Face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther 2018; 47: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vigerland S, Lenhard F, Bonnert M, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 50: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen AT, Wu S, Tomasino KN, et al. A multi-faceted approach to characterizing user behavior and experience in a digital mental health intervention. J Biomed Inform 2019; 94: 103187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howarth A, Quesada J, Silva J, et al. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Health 2018; 4: 2055207618770861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carolan S, Harris PR, Cavanagh K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drissi N, Ouhbi S, Marques G, et al. A systematic literature review on e-mental health solutions to assist health care workers during COVID-19. Telemed e-Health 2021; 27: 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterne J, Savovic J, Page M, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J 2019; 366: l4898. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kloos N, Drossaert CHC, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. Online positive psychology intervention for nursing home staff: A cluster-randomized controlled feasibility trial of effectiveness and acceptability. Int J Nurs Stud 2019; 98: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adair KC, Rodriguez-Homs LG, Masoud S, et al. Gratitude at work: prospective cohort study of a web-based, single-exposure well-being intervention for health care workers. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e15562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Congiusta S, Ascher EM, Ahn Set al. et al. The use of online physician training can improve patient experience and physician burnout. Am J Med Qual 2020; 35: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett K, Stewart Iet al. A preliminary comparison of the efficacy of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) stress management interventions for social and healthcare workers. Health Soc Care Community 2021; 29: 113–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhardwaj P, Pathania M, Bahurupi Y, et al. Efficacy of mHealth aided 12-week meditation and breath intervention on change in burnout and professional quality of life among health care providers of a tertiary care hospital in north India: a randomized waitlist-controlled trial. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1258330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolier L, Ketelaar SM, Nieuwenhuijsen K, et al. Workplace mental health promotion online to enhance well-being of nurses and allied health professionals: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv 2014; 1: 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dincer B, Inangil D. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on nurses’ stress, anxiety, and burnout levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. EXPLORE 2021; 17: 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Richards ML, et al. A randomized, controlled study of an online intervention to promote job satisfaction and well-being among physicians. Burn Res 2016; 3: 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiol-DeRoque MA, Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Jiménez R, et al. A mobile phone–based intervention to reduce mental health problems in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (PsyCovidApp): randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021; 9: e27039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hersch RK, Cook RF, Deitz DK, et al. Reducing nurses’ stress: a randomized controlled trial of a web-based stress management program for nurses. Appl Nurs Res 2016; 32: 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaiswal S, Purpura SR, Manchanda JK, et al. Design and implementation of a brief digital mindfulness and compassion training app for health care professionals: cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2024; 11: e49467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ketelaar SM, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Gärtner FR, et al. Effect of an E-mental health approach to workers’ health surveillance versus control group on work functioning of hospital employees: a cluster-RCT. PLoS One 2013; 8: e72546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mistretta EG, Davis MC, Temkit M, et al. Resilience training for work-related stress among health care workers: results of a randomized clinical trial comparing in-person and smartphone-delivered interventions. J Occup Environ Med 2018; 60: 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smoktunowicz E, Lesnierowska M, Carlbring P, et al. Resource-Based internet intervention (med-stress) to improve well-being among medical professionals: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e21445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu H, Eley R, Kynoch Ket al. et al. Effects of mobile mindfulness on emergency department work stress: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med Australas 2022; 34: 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghawadra SF, Abdullah KL, Choo WY, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based training on stress, anxiety, depression and job satisfaction among ward nurses: a randomized control trial. J Nurs Manag 2020; 28: 1088–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abd-Alrazaq AA, Rababeh A, Alajlani M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of using chatbots to improve mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020b; 22: e16021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apolinário-Hagen J, Harrer M, Kählke F, et al. Public attitudes toward guided internet-based therapies: web-based survey study. JMIR Ment Health 2018; 5: e10735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Musiat P, Goldstone P, Tarrier N. Understanding the acceptability of e-mental health - attitudes and expectations towards computerised self-help treatments for mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 2014; 14: 09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gulliver A, Calear AL, Sunderland M, et al. Predictors of acceptability and engagement in a self-guided online program for depression and anxiety. Internet Interv 2021; 25: 100400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Shepherd J, Gevaert J, et al. Design and development of a digital intervention for workplace stress and mental health (EMPOWER). Internet Interv 2023; 34: 100689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lutz J, Offidani E, Taraboanta L, et al. Appropriate controls for digital therapeutic clinical trials: a narrative review of control conditions in clinical trials of digital therapeutics (DTx) deploying psychosocial, cognitive, or behavioral content. Front Digit Health 2022; 4: 823977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spanakis P, Lorimer B, Newbronner E, et al. Digital health literacy and digital engagement for people with severe mental ill health across the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in England. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2023; 23: 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-dhj-10.1177_20552076241278313 for Self-help digital mental health intervention in improving burnout and mental health outcomes among healthcare workers: A narrative review by Lwin M. Aye, Min M. Tan, Alexandre Schaefer, Sivakumar Thurairajasingam, Pascal Geldsetzer, Lay K. Soon, Ulrich Reininghaus, Till Bärnighausen and Tin T. Su in DIGITAL HEALTH