Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking is one of the leading causes of preventable death in the world. Decisions to smoke are often made within a broad social context and therefore community interventions using coordinated, multi‐component programmes may be effective in influencing the smoking behaviour of young people.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of multi‐component community based interventions in influencing smoking behaviour, which includes preventing the uptake of smoking in young people.

Search methods

The Tobacco Addiction group's specialised register, Medline and other health, psychology and public policy electronic databases were searched, the bibliographies of identified studies were checked and raw data was requested from study authors. Searches were updated in August 2010.

Selection criteria

Randomized and non randomized controlled trials that assessed the effectiveness of multi‐component community interventions compared to no intervention or to single component or school‐based programmes only. Reported outcomes had to include smoking behaviour in young people under the age of 25 years.

Data collection and analysis

Information relating to the characteristics and the content of community interventions, participants, outcomes and methods of the study was extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second. Studies were combined in a meta‐analysis where possible and reported in narrative synthesis in text and table.

Main results

Twenty‐five studies were included in the review and sixty‐eight studies did not meet all of the inclusion criteria. All studies used a controlled trial design, with fifteen using random allocation of schools or communities. One study reported a reduction in short‐term smoking prevalence (twelve months or less), while nine studies detected significant long‐term effects. Two studies reported significantly lower smoking rates in the control population while the remaining thirteen studies showed no significant difference between groups. Improvements were seen in secondary outcomes for intentions to smoke in six out of eight studies, attitudes in five out of nine studies, perceptions in two out of six studies and knowledge in three out of six studies, while significant differences in favour of the control were seen in one of the nine studies assessing attitudes and one of six studies assessing perceptions.

Authors' conclusions

There is some evidence to support the effectiveness of community interventions in reducing the uptake of smoking in young people, but the evidence is not strong and contains a number of methodological flaws.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Female, Humans, Male, Young Adult, Health Promotion, Smoking Prevention, Age Factors, Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Can community interventions deter young people from starting to smoke?

Some evidence is available to suggest that multi‐component community interventions are effective in influencing smoking behaviour and preventing the uptake of smoking in young people. These interventions use co‐ordinated, widespread, multi‐component programmes to try and influence young people's behaviour. Community members are often involved in determining and/or implementing these programmes. These include education of tobacco retailers about age restrictions, programmes for prevention of smoking‐related diseases, mass media, school and family‐based programmes. Changes in intentions to smoke, knowledge, attitudes and perceptions about smoking did not generally appear to affect the long‐term success of the programmes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people.

| Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with preventing smoking in young people Settings: Intervention: Community interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Community interventions | |||||

| Weekly smoking Follow‐up: 2‐ to 15‐years | Study population | OR 0.83 (0.59 to 1.17) | 17508 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 169 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (107 to 192) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 170 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (108 to 193) | |||||

| Monthly smoking Follow‐up: 2‐ to 15‐years | Study population | OR 0.97 (0.81 to 1.16) | 27077 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | ||

| 148 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (123 to 168) | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| 140 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (116 to 159) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 A mixture of RCT's and CCT's were used, lack of allocation concealment, blinding and significant loss to follow‐up 2 Significant heterogeneity as determined by a combination of visual data inspection and I‐squared statistic. 3 Some studies required manual adjustment for clustering effects as this was not addressed by the original study authors

Background

The reduction of smoking prevalence among adolescents remains a key public health priority (BMA 2008). Addiction to nicotine usually begins during adolescence although the proportion of new smokers who first use cigarettes after the age of 18 has increased in the United States from around 25% in 2002 to 40% in 2009 (SAMHSA 2009). An estimated one‐in‐five young teenagers already smokes regularly and another 30 million children throughout the world will take up the habit every year (GYTSC 2002) with 19.1% of school students who had never smoked cigarettes indicating that they would initiate smoking within the next year (MMWR 2008). In England the prevalence of regular smoking amongst 11 to 15 year olds in 2009 was 6%, a decline from 13% in 1996 (NHS IC 2010). Amongst 15 year olds the prevalence was higher in girls (16%) than boys (14%) (NHS IC 2010). Current reports still indicate that globally, smoking behaviour among adolescent girls is increasing over that of boys (Mackay 2006; Warren 2009). The UMDNJ 2007 New Jersey Youth Tobacco Survey estimates that 90 million cigarettes, or 4.2 million packs of cigarettes were consumed by high‐school students annually in 2006.

There is a wide‐held theory that if smoking does not start during adolescence, it is unlikely ever to occur (USDHHS 1994). This has resulted in various attempts to reduce the number of young people taking up smoking through primary prevention programmes, which have been designed to discourage experimentation with cigarettes and to deter regular use. Most interventions have included prevention programmes delivered in school settings, however the results have been mixed and reported effects small (Rooney 1996, Wiehe 2005, Thomas 2006). Mass media interventions have been compared in another Cochrane review, Brinn 2010 also with mixed results. The most effective campaigns for the review (Brinn 2010) were based on solid theoretical grounds, used formative research in designing the campaign message, and the message broadcasts were of reasonable intensity over extensive periods of time. Recognition that decisions to smoke are made within a broad social context has led to the development and implementation of community‐wide programmes. Such interventions are based on the premise that social and environmental processes impact upon health and well‐being and contribute to health decline, disease, and mortality. It has been argued that the essence of the community approach to influence smoking behaviour, in particular smoking prevention lies in its multi‐dimensionality, in the co‐ordination of activities to maximise the chance of reaching all members, and in ongoing and widespread support for the maintenance of non‐smoking behaviour (Schofield 1991).

Interventions with multiple components such as age restrictions for tobacco purchase, tobacco‐free public places, various mass media communications and special programmes in schools are often combined to create large‐scale community‐wide initiatives, to influence the smoking behaviour of young people. Initiatives vary in the extent to which they emphasise community involvement in problem specification and planning of the intervention. Some have been conducted through community groups and organisations emphasising a principle of 'ownership' or 'partnership' in promoting health. Community members are involved in decisions about the implementation of various activities within the programme, often building on existing organisational structures.

Despite the potential of community‐wide programmes, debate continues about their effectiveness in influencing the smoking behaviour of young people. For example, a non‐systematic review of eighteen smoking prevention programmes up to 1995 concluded that community initiatives have yet to demonstrate that they can directly reduce smoking prevalence in adolescents (Stead 1996).

Objectives

To carry out a systematic review to assess the effectiveness of community interventions in influencing the smoking behaviour of young people. In particular the following issues were addressed:

a. The effectiveness of community interventions, compared with no intervention in influencing the smoking behaviour of young people;

b. The effectiveness of community interventions compared with other single component interventions (e.g. school‐based programmes) in influencing the smoking behaviour of young people.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered studies using one of the following designs:

a. RCT: (randomized controlled trials) in which participants were assigned prospectively to one or more alternative forms of intervention using a process of random allocation;

b. CCT: (controlled clinical trials) in which participants were assigned prospectively at the level of community, geographical region or school, to one or more alternative intervention groups using a quasi‐random allocation method, or in which the method of assignment was unclear but could possibly have been random or quasi‐random;

c. CBA: (controlled before‐and‐after trial) where contemporaneous baseline and post‐intervention data was collected from the intervention group and a comparable population, (no CBA studies were identified for inclusion in this review).

Each study needed to have a minimum of two clusters in each of the intervention and control groups.

Studies which did not report baseline characteristics were excluded.

Types of participants

Young people aged less than 25 years.

Types of interventions

Interventions were considered which:

a. were targeted at entire or parts of entire communities or large areas, and;

b. had the intention of influencing the smoking behaviour of young people, and;

c. focused on multi‐component (i.e. more than one) community intervention, which could include but was not limited to: school‐based programmes, media promotion (e.g. TV, radio, print), public policy, organisational initiatives, health care provider initiatives, sports, retailer and workplace initiatives, anti‐tobacco contests and youth anti‐smoking clubs.

Community interventions were defined as coordinated widespread (multi‐component) programmes in a particular geographical area (e.g. school districts) or region or in groupings of people who share common interests or needs, which support non‐smoking behaviour.

Studies which only included single component interventions, did not have community involvement (e.g. school‐based only) or had mass media as the sole form of intervention delivery were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Young people were classified as smokers or non‐smokers in different ways according to daily, weekly or monthly frequency of smoking, or by lifetime consumption. Where possible the strictest distinction was used, in which youths with any history of cigarette use were defined as smokers.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure of smoking behaviour were objective (e.g. saliva thiocyanate levels, alveolar carbon monoxide) or self‐reported smoking. This outcome was measured in terms of:

a) the level of change in smoking behaviour observed,

b) the sustainability of the change in behaviour after the intervention ('less than' versus 'longer than' one year).

Search methods for identification of studies

Possible studies were identified from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Database which includes reports of possible trials identified from regular searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO (see search strategies and dates in the Tobacco Addiction Group Module). Additional searches covered a wider range of databases and combined terms related to smoking, young people and community‐wide interventions.

Electronic searches

For this update searches were limited by publication date from 2002 onwards. The search platform is that used for the present update. The following databases were searched:

Searched via OVID on 18th August 2010: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Econlit. Searched via CSA on 19th August 2010: Sociological Abstracts, British Humanities Index, PAIS, ERIC, ASSIA. Searched in the Cochrane Library issue 3, 2010: Cochrane Central Database of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Other databases searched for the original review were no longer easily available, and since no original studies had been located solely from one of these sources we did not update these searches. Databases searched for earlier versions are listed in Appendix 1

The MEDLINE strategy is listed below. Other strategies are provided in the Appendix

1 exp Smoking/ 2 "Tobacco Use Disorder"/ or Tobacco/ 3 (smoking or tobacco or cigarette$).ti,ab. 4 1 or 2 or 3 5 (young adj people).ti,ab,sh. 6 (children or juveniles or girls or boys or teenagers or adolescents).ti,ab. 7 Adolescent/ 8 Child/ 9 minors.ti,ab,sh. 10 8 or 6 or 7 or 9 or 5 11 (nationwide or statewide or countrywide or citywide).ti,ab,sh. 12 (nation adj wide).ti,ab,sh. 13 (state adj wide).ti,ab,sh. 14 ((country or city) adj wide).ti,ab,sh. 15 outreach.ti,ab,sh. 16 (multi adj (component or facet or faceted or disciplinary)).ti,ab,sh. 17 (field adj based).ti,ab,sh. 18 (interdisciplinary or (inter adj disciplinary)).ti,ab,sh. 19 local.ti. 20 citizen$.ti,ab,sh. 21 (community or communities).mp. 22 11 or 21 or 17 or 12 or 20 or 15 or 14 or 18 or 13 or 16 or 19 23 22 and 4 and 10

Searching other resources

The bibliographies of papers identified in the electronic searches were checked for any additional relevant studies, and personal contact with content area specialists were made.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

From the title, abstract, or descriptors, KC independently reviewed the literature searches to identify potentially relevant trials. All studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria in terms of study design, population or interventions, were excluded. All potential inclusions and 'exclude but relevant' studies were confirmed by a second author (MB).

Data extraction and management

One review author (KC) completed data extraction for each included study, which was reviewed by an additional author (either MB or NL) using a tailored standardised data extraction form. All disagreements were resolved by consensus.

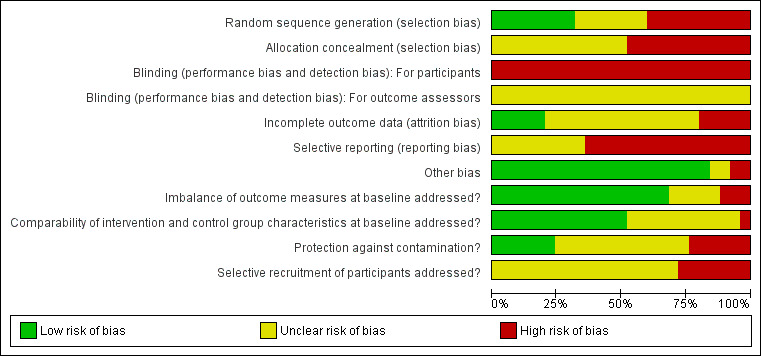

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality of included studies were assessed using the ‘Risk of bias’ tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) and additional criteria developed by the Cochrane EPOC Group (EPOC 2009). One review author (KC) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study, which was independently assessed again by one of two additional authors (MB or NL). All disagreements were resolved by consensus. Risk of bias was assessed with the following seven domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other potential threats to validity (Higgins 2008). Three additional domains were included that assessed design‐specific threats to validity including: imbalance of outcome measures at baseline; comparability of intervention and control group characteristics at baseline; and protection against contamination (EPOC 2009). Finally, for cluster study designs, we assessed the risk of bias associated with an additional domain; selective recruitment of participants. In studies eligible for inclusion in this review, the term ‘participant’ may refer to schools, community organisations and individual young people.

Measures of treatment effect

Outcomes

Outcome measures for RCT, CCT and CBA studies were selected in accordance with Cochrane Collaboration standards (Higgins 2008) for dichotomous outcomes, continuous outcomes (mean difference) and counts or rates (rate ratio).

Unit of analysis issues

Studies found to contain unit of analysis errors were re‐analysed if data were available. Unit of analysis errors are found in studies that allocate participants to treatment or control in clusters (e.g. schools and communities), but analyse the results by individual participants. This can result in overestimation of the statistical significance of the results by not accounting for the clustering of individuals in the data (Rooney 1996; Ukoumunne 1999). For studies that did not include adjustments for clustering the size of the trial was reduced to the effective sample size (Rao 1992) using the original sample size from each study, divided by a design effect of 1.2 which is consistent with other smoking cessation community intervention trials (Gail 1992) and as per recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook, section 16.3.4 (Higgins 2008).

Dealing with missing data

Where statistics essential for analysis were missing (e.g. group means and standard deviations for both groups are not reported) and can not be calculated from other data, we attempted to contact the authors to obtain data.

Assessment of reporting biases

Potential reporting biases would have been assessed using a funnel plot, providing the inclusion of greater than ten studies for each reported outcome. Asymmetry in the plot could be attributed to publication bias, but may well be due to true heterogeneity, poor methodological design or artefact. As there were fewer than ten studies for each outcome, the reporting biases have been extrapolated within the 'other bias' section in the risk of bias tables.

Data synthesis

Meta‐analyses were only conducted if relevant, valid data were available from at least two studies of the same design, with interventions that were conceptually similar (e.g. interventions that include school components) and measured the same outcome. The fixed‐effects model was used for meta‐analysis with the exception of data presenting significant heterogeneity as determined by a combination of the I² statistic (> 60%) and visual inspection of the data. In such instances the analysis was converted to the random‐effects model.

For smoking behaviour outcomes entered in a meta‐analysis we used outcomes reported at the longest follow up. Studies that reported a follow up at less than 12 months and after a longer period could be included in both time periods in the sub group analysis by duration of follow up. For studies with multiple outcome measures that were appropriate for inclusion in a meta‐analysis, the authors ranked the effect sizes of each measure and used the median value. Where two appropriate measures were used, the most conservative value was taken.

A tabular analysis considering the direction of observed effects and size for each study outcome is presented in Additional tables. A narrative synthesis was also conducted taking into consideration the methodological quality of each study (Results).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The effects of community interventions are complex, and may be influenced by a number of competing factors. Significant heterogeneity relating to results and study characteristics was determined by a combination of the I² statistic (> 60%) and visual inspection of the data as per recommendations in the Cochrane handbook, chapter 9.5.4 (Higgins 2008). We were unable to use a Forrest plot for visual inspection of the data due to an insufficient number of included studies for the reported outcomes. We conducted sub‐group analyses to further investigate the different aspects of community intervention programmes. Subgroup analyses were conducted only if comparable data (as outlined above) was available from two studies, which could be considered similar enough to be included in the same subgroup, (e.g. two studies conducted in rural areas), or reporting separate outcomes for different subgroups (e.g. by gender). The following characteristics were pre‐specified for possible sub‐group analysis prior to data extraction:

a) Population ‐ e.g. developed/developing countries or urban/rural populations

b) Subjects ‐ e.g. gender, age or socioeconomic status

c) Intervention ‐ e.g. number of intervention components, duration of interventions or intensity of interventions

d) Design ‐ e.g. duration of follow‐up

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on studies with a high risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables

Results of the search

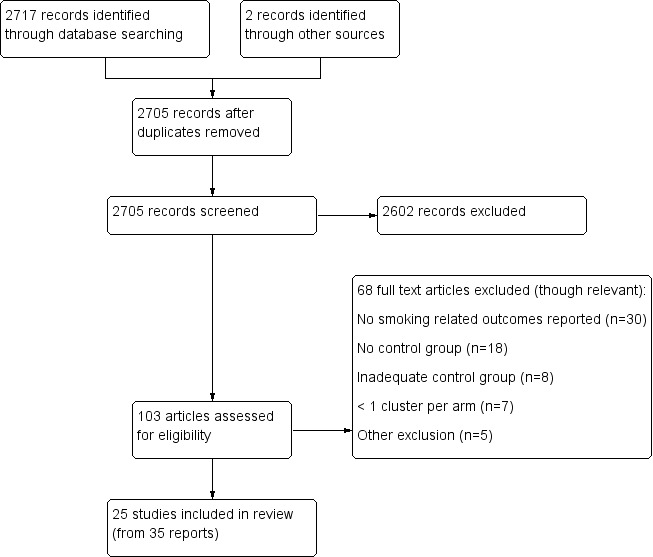

Reports relating to twenty five studies met all of the inclusion criteria from 2717 articles (see Figure 1 for PRISMA diagram). Detailed information about each included study is provided in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. (See 'Characteristics of excluded studies' for details of the sixty eight excluded studies and reasons for exclusion.) All of the included studies used a controlled trial design with clustering.

1.

Flow diagram of literature for this review

Included studies

All 25 studies investigated the effects of multi‐component community interventions directed at young people, <25 years, using either a parallel group RCT (n=15) or CCT (n=10) design. Trials were published between 1989 and 2009, though the methodology and preliminary results for some studies were published earlier; from 1983. A total of approximately 104,000 participants were recruited from a mixture of schools (n=735), community clubs (n=92), communities/cities/towns n=49 and paediatric practices (n=12). Seventeen studies originated from the United States of America, three from Australia, two from the United Kingdom and one each from India and Finland. One study (De Vries 2003) included six countries (Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom) as a nested, cluster controlled clinical trial.

Characteristics of communities:

The communities in which the interventions took place varied across the studies. For example, in one study the populations of the communities randomised ranged from 1,700 to 13,500 (Biglan 2000) and another was based in a city of 1.3 million people (Pentz 1989), while the largest study spanned six countries (De Vries 2003). Some communities were in rural areas (Biglan 2000; Hancock 2001) whilst others were in towns or cities in predominantly urban areas (Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Piper 2000) and some communities were specifically targeted because of economic deprivation (St Pierre 1992; Perry 2008).

Characteristics of participants:

The participants varied across studies. Some studies targeted young people in specific high‐risk groups; for example those defined as high‐risk because they lived in a deprived area (St Pierre 1992; Perry 2008), because they attended a continuation high‐school (continuation high‐schools are alternative high‐schools in the USA for young people at risk of dropping out of the school) (Sussman 1998; Winkleby 2004), or because they were expected to have a high smoking prevalence (Elder 2000). Native American children living on reservations were targeted in one study (Schinke 2000). The age of participants ranged from 8 to 24 years across the different studies. The age of targeted participants also varied and ranged from 10 to 24 years of age.

Characteristics of interventions:

The interventions evaluated in the 25 studies were diverse and each differed in the focus of activity. Thirteen focused specifically on influencing youth smoking behaviour through tobacco prevention initiatives (St Pierre 1992; Gordon 1997; Tang 1997; Sussman 1998; Biglan 2000; Elder 2000; Piper 2000; Schinke 2000; Stevens 2002; Schofield 2003; Gordon 2008; Perry 2008; Klein 2009), five included tobacco prevention with an additional aim to reduce specific health risk factors for cancer (Hancock 2001) or cardiovascular disease (Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Baxter 1997; Vartiainen 1998), while the remaining seven studies combined goals through a combination of tobacco prevention with either reduction or cessation initiatives (Pentz 1989; Murray 1994; D'Onofrio 2002; De Vries 2003; Perry 2003; Winkleby 2004; Hawkins 2009). Though the interventions for all studies involved influencing smoking behaviour, nine studies also included interventions for alcohol, (Elder 2000; Stevens 2002) alcohol and marijuana (Schinke 2000) or alcohol, marijuana, other drug use and/or delinquent behaviour (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992; Sussman 1998; Piper 2000; Stevens 2002; Perry 2003).

The extent to which attempts were made to include community participation also varied significantly. In five studies community leaders were encouraged to become actively involved in both the development and in giving ongoing support for the community programmes (Perry 1994; Piper 2000; Hancock 2001; Perry 2003; Hawkins 2009), though the duration and intensity of involvement differed. In the 'Age Appropriate' arm of the Piper 2000 study a community organiser was employed for six months over a three year period whilst in the 'Intensive' arm the organiser was employed for one fifteen month block. They were trained to use survey data, prioritise and target risk factors for prevention actions and to choose which prevention policies and programmes addressed the communities needs. However, in the Perry 2003 study, eight community organisers were hired to create and facilitate extra‐curricular activities for the second component of the D.A.R.E. intervention. In the study by Hawkins 2009, community leaders received six training sessions delivered over six to twelve months to form a community coalition of diverse stakeholders to implement and monitor the intervention. Other studies involved multiple organisations including the national health service, city councils, social workers, business owners, voluntary organisations, sports organisations, health care providers, community organisations, media, retailers, schools, government, law enforcement or workplaces.

Specific intervention components:

The majority of studies included school components in addition to a multi‐component community intervention (twenty one of the twenty five included studies), though the duration and intensity differed. As examples, Biglan 2000 had five class sessions over a one week period for three consecutive years, and Hawkins 2009 allowed schools to choose any combination of school and community programmes which ranged from five, two‐hour weekly sessions to weekly, year‐long classroom activities; Pentz 1989 included ten school and homework sessions per year over two years, while D'Onofrio 2002 only included an optional activity to conduct a tobacco survey at school as part of an intervention run through local community 4‐Health Clubs. This intervention included education, booklets, worksheets, puzzles, stories, experiments, poster and activities to make a anti‐smoking commercial at 4‐Health Clubs. One other trial conducted an intervention with local girls' and boys' Clubs St Pierre 1992 including education, group activities and video sessions, however no school‐based interventions were included. In total four studies included no school related activities (St Pierre 1992; Elder 2000; Stevens 2002; Klein 2009). The remaining three studies involved: recruitment from a migrant education programme with an intervention focusing on parent/child communications with eight weeks of evening group meetings plus booster sessions (Elder 2000); Stevens 2002 enrolled subjects from a paediatric primary care setting, where the family would decide upon a personal tobacco prevention policy with the addition of subsequent clinician education visits, twelve mail out newsletters specific to adults and twelve specific to young people in addition to letters from their respective clinician. Finally the Klein 2009 intervention focused on the government initiated 'Clean Indoor Air' policy as their programme, with an evaluation of the subsequent smoking ban in public places, particularly in restaurants, cafes and bars.

Optional extracurricular projects were added to some interventions including organisation of a tobacco‐free day and the option of working with community agencies on tobacco use prevention (D'Onofrio 2002), non‐smoking conference attendance on National non‐smoking day (De Vries 2003), health fairs, after‐school clubs and amusement park activities (Gordon 2008), promotion of World No Tobacco Day (Schofield 2003), drug‐free parties and drug‐awareness week (Sussman 1998), amongst others (Hancock 2001; Perry 2003). Four studies used incentives for completion of tobacco prevention assignments and to improve class attendance (Piper 2000; Stevens 2002; Schofield 2003; Gordon 2008).

Sixteen trials involved parent/guardian participation which mainly included education through pamphlets or homework requiring parent/guardian involvement (Gordon 1997; Biglan 2000; Piper 2000; Hancock 2001; D'Onofrio 2002; Perry 2003; Schofield 2003; Perry 2008; Gordon 2008; Hawkins 2009). Though some studies did have stronger parental involvement with equal parent/youth attendance for group sessions (Elder 2000; Stevens 2002), requests or incentives to quit smoking as a role model (De Vries 2003; Tang 1997), or attendance at tobacco prevention information sessions (Pentz 1989; Schinke 2000). Ten studies included peers as role models, (Baxter 1997; Vartiainen 1998; Biglan 2000; Elder 2000; Piper 2000; Perry 2003;Schinke 2000; Schofield 2003; Perry 2008;Winkleby 1993), two of which used older high‐school students (Winkleby 1993; Schinke 2000). Four studies were simultaneously run with adult programmes (Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Baxter 1997; Vartiainen 1998).

Media advocacy components were included in nine studies, two of which included television prevention initiatives (Pentz 1989; De Vries 2003) in addition to other media. The remaining seven studies used a combination of local media publications, magazines, radio, flyers, posters and newspapers (Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Tang 1997; Biglan 2000; Piper 2000; Schinke 2000; Hancock 2001).

Six interventions aimed at young people included components focusing on reducing tobacco scales to minors. Some included specific activities for youth to reduce illegal tobacco sales, (Biglan 2000; De Vries 2003; Schofield 2003; Winkleby 2004) whilst the study by Gordon 1997 reminded tobacco retailers about the law before conducting retailer tests where young people attempted to purchase tobacco products. Another study (Tang 1997) provided retailer education and surveillance.

Health care professionals as intervention deliverers were a key component in four studies and a smaller component of interventions in four other studies. The study by Stevens 2002, used the paediatric primary care setting to recruit youth and implement the intervention via family/clinician meetings through individualised development of a smoke‐free policy, for each family. Other studies included training for pharmacists and dental care interventions (De Vries 2003), continuing education and utilisation of health professionals (Perry 1994; Hancock 2001), or simply provided health education through intervention components such as mass media and other health promotion activities (Pentz 1989; Piper 2000; Schofield 2003; Winkleby 2004). Further encouragement into healthy life‐style choices through smoke‐free sporting events such as roller‐skating, rock climbing, bowling, snowboarding, skiing, disc golf tourneys and skateboarding competitions, were also aspects to the Sussman 1998, De Vries 2003 and Gordon 2008 studies.

Specific control components:

Most studies used usual activities as the control groups (Baxter 1997; Tang 1997; St Pierre 1992; Winkleby 1993; Murray 1994; Perry 1994; Sussman 1998; Vartiainen 1998; Piper 2000; Schinke 2000; Hancock 2001; D'Onofrio 2002; De Vries 2003; Schofield 2003; Gordon 2008; Klein 2009; Hawkins 2009), though two studies included minimal interventions which included components to influence youth smoking behaviour ‐ Biglan 2000 opted to invest the same intensity and duration for the programme, where the intervention focused on drug use prevention, and Gordon 1997 provided control students with smoking prevention booklets which were used in schools, plus take home workbooks. Retailers were also tested for underage cigarette purchases in the control catchment areas through students attempting purchases. Three control areas were provided with delayed interventions, which were commenced after the evaluation period for the studies were completed (Pentz 1989; Perry 2003; Perry 2008). One study (Schofield 2003) offered the intervention to control schools after completion of the evaluation only if the schools requested it, however support was offered for other health related issues during the evaluation period. Other initiatives unrelated to smoking were used as controls in some studies to account for biases associated with increased resources and attention provided to intervention subjects, or as an alternative means of providing some form of benefit to the control clusters for their participation in the evaluation. The control group in Elder 2000 consisted of a first aid and home safety education programme focused on preparation for emergencies, skills and household safety concerns such as baby‐proofing a house. Education, role‐playing sessions and intensity of the programme mimicked that of the smoking prevention intervention. In Winkleby 2004 school students learned about drug and alcohol abuse prevention through a modified version of Project Toward No Drug abuse, (Sussman 1998) focusing on health motivation, social skills and decision making regarding drug and alcohol use.

Intervention delivery:

Methods for the programme message implementation varied significantly between studies with the majority of interventions delivered by multiple individuals. Teachers and other school faculty contributed to intervention delivery in sixteen studies (Pentz 1989; Murray 1994; Perry 1994; Tang 1997; Sussman 1998; Vartiainen 1998; Biglan 2000; Piper 2000; Schinke 2000; Hancock 2001; De Vries 2003; Schofield 2003; Perry 2003; Gordon 2008; Perry 2008; Hawkins 2009) and were trained by study investigators or paid research staff. The level of training varied between studies and within study clusters, for example in De Vries 2003, the largest study including six countries, training for teachers varied from two to forty‐eight hours. Adult and youth volunteers contributed as trained volunteer leaders (Sussman 1998; D'Onofrio 2002), volunteers for Big Brother and Big Sister tutoring programmes (Hawkins 2009), peer narrators for prevention information (Gordon 2008) or other roles (Biglan 2000; Elder 2000; Hancock 2001). Peers were also elected by teachers or fellow class mates and were trained to act as role models and deliver influential programme messages for seven studies (Pentz 1989; Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Vartiainen 1998; Perry 2003; Schofield 2003; Perry 2008). Similarly, five studies recruited parents as channels to enhance and deliver programme information (Elder 2000; Schinke 2000; De Vries 2003; Schofield 2003; Gordon 2008). Research or project staff delivered the intervention directly to individuals only in four studies (Sussman 1998; Vartiainen 1998; Winkleby 2004; Gordon 2008) whilst specialised groups were used for six studies. These groups included cancer Council health educators, (Hancock 2001) health and human services workers for community based, youth focused and family focused programmes, (Hawkins 2009) government level policies, (Klein 2009) paediatric primary care clinicians, (Stevens 2002) and law enforcement (Schinke 2000; Perry 2003).

Follow‐up:

The duration of follow up at which smoking status was assessed differed between studies and in some cases was not clear. Outcomes were measured, for example, at the end of the intervention (Baxter 1997; Gordon 1997; De Vries 2003), one year later (Sussman 1998; Baxter 1997; Hancock 2001), approximately one and a half years later (Elder 2000; D'Onofrio 2002), three and a half years later (Schinke 2000), and in the case of one study, fifteen years after the intervention (Vartiainen 1998).

Outcome collection:

Smoking behaviour was assessed in all studies by self‐report, though two studies used face‐to‐face interviews for data collection purposes. A number of different intermediate outcomes were measured, including knowledge about the effects of smoking, attitudes toward smoking and intentions to smoke in the future. Chemical validation occurred in eight studies by exhaled carbon monoxide (Pentz 1989; Winkleby 1993; Murray 1994; Sussman 1998; Biglan 2000; Elder 2000; Piper 2000; Winkleby 2004) in addition to plasma thiocyanate levels for one study (Winkleby 1993). A random number of students in half of the school classes in the Perry 1994 study were assessed for saliva thiocyanate levels, whilst in the Schinke 2000 trial only a small proportion were analysed. Researchers in the Piper 2000 study collected exhaled carbon monoxide samples for bogus pipeline measures only.

Outcome collection occurred through different methods which could also differ at various time points throughout the study and in some trials methods, were not clear. These include research staff and trained data collectors in nine studies, (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992; Perry 1994; Sussman 1998; Vartiainen 1998; Piper 2000; Schofield 2003; Winkleby 2004; Perry 2008) school teachers and/or other faculty in eleven (Murray 1994; Baxter 1997; Gordon 1997; Tang 1997; Biglan 2000; Hancock 2001; De Vries 2003; Perry 2003; Schofield 2003; Gordon 2008; Hawkins 2009), via telephone calls in four studies (Biglan 2000; D'Onofrio 2002; Winkleby 2004; Klein 2009), postal questionnaires in six (Pentz 1989; Tang 1997; Vartiainen 1998; Biglan 2000; D'Onofrio 2002; Stevens 2002), and face‐to‐face in two (Winkleby 1993; Elder 2000). One study (Biglan 2000) sent $10 in an envelope with the questionnaire as an incentive for parents to complete and return the survey.

Risk of bias in included studies

Key methodological features of the twenty five included studies are summarised in the table of characteristics of included studies (Figure 2).

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Sequence generation:

Methods for choosing intervention and control areas varied across studies and in some cases the details provided were unclear. Some studies chose areas specifically to target particular groups of young people such as those with a high risk of substance abuse (Sussman 1998). In some studies the allocation of areas, communities or schools within particular geographical regions to either intervention or control was random (Schinke 2000), whilst for other studies allocation was random after communities or areas had been matched on a number of different factors. The investigators described a random component for sequence generation in eight studies (Gordon 1997; Biglan 2000; Hancock 2001; Schinke 2000; D'Onofrio 2002; Winkleby 2004; Gordon 2008; Hawkins 2009) which includes coin tossing or the use of computer generated random number tables. Ten studies had inadequate sequence generation (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992; Winkleby 1993; Perry 1994; Baxter 1997; Tang 1997; Vartiainen 1998; Piper 2000; De Vries 2003; Klein 2009), and the remaining seven studies were unclear.

Allocation concealment:

Allocation concealment was inadequate in twelve studies, i.e. the assignment of participants was not conclealed from investigators (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992; Winkleby 1993; Murray 1994; Perry 1994; Baxter 1997; Tang 1997; Vartiainen 1998; Piper 2000; De Vries 2003; Klein 2009), and unclear in the remaining thirteen.

Blinding for participants and outcome assessors:

All studies were inadequate in terms of blinding for participants due to the nature of a community‐delivered intervention. No authors mentioned any attempts to conceal subject allocation from outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data:

Complete reporting of outcome data occurred in five studies (Vartiainen 1998; De Vries 2003; Perry 2003; Perry 2008; Hawkins 2009), which accounted for attrition in the sample population and described methods of handling missing variables in data sets, such as via random imputation or removal of data sets missing 90% of the responses etc. Five other studies failed to address incomplete outcome data. Baxter 1997 had significant amounts of data missing from one of the intervention schools and three classes in the control school; Hancock 2001 failed to mention characteristics of participants unable to be followed up and mentioned the collection of weekly and ever smoking data outcomes, however the data was not presented as it was deemed 'very similar' to the results for monthly smoking. The Klein 2009 study was unable to collect data at some time points due to gaps in funding, whereas the Piper 2000 study were unable to schedule in‐school surveys for two intensive and one control school despite attempts. Both the Hancock 2001 and St Pierre 1992 studies mentioned outcome variables as being collected, which were not reported in the publications. The remaining fourteen studies had unclear reporting of incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting:

Selective reporting was unclear in nine studies (Murray 1994; Baxter 1997; Gordon 1997; Sussman 1998; Vartiainen 1998; Schinke 2000; Perry 2003; Schofield 2003; Winkleby 2004) and was a high risk of bias for the remaining fifteen. Examples of selective reporting include outcomes reported incompletely with missing n‐values for separate intervention and control groups or as a visual representation only which can not be meta‐analysed or studies failing to include results for a key outcome which would be expected to be reported for such a study.

Imbalance of outcome measures at baseline:

Three studies (Winkleby 1993; Baxter 1997; Schofield 2003) failed to address imbalances in outcome measures at baseline, five studies were unclear (Tang 1997; Gordon 1997; Hancock 2001; Perry 2003; Winkleby 2004), whilst the remaining seventeen studies accounted for any imbalances in outcome measures at baseline through statistical measures.

Comparability of intervention and control characteristics at baseline:

Only one study failed to address comparability of intervention and control group characteristics at baseline. In Pentz 1989 the authors mentioned a possibility of non‐equivalence of study groups, since the majority of schools were assigned to programme and control conditions based on administrator flexibility. No adjustments were made in the analysis to account for these imbalances. Thirteen studies adequately addressed imbalances in intervention and control characteristics at baseline through statistical adjustments or did not have any significant imbalances (St Pierre 1992; Winkleby 1993; Murray 1994; Perry 1994; Vartiainen 1998; Piper 2000; Schinke 2000; Hancock 2001; D'Onofrio 2002; Stevens 2002; Perry 2008; Hawkins 2009; Klein 2009). The remaining 11 studies had unclear comparability between study characteristics at baseline.

Protection against contamination:

Seven studies had potential sources of contamination: A state‐wide tobacco education programme was initiated in 1990, which may have affected the control group results in the D'Onofrio 2002 study. The control group in the Netherlands for the De Vries 2003 study also underwent a national smoking prevention programme simultaneously with the evaluation for this programme. The Elder 2000 study had schools containing both intervention and control groups within them, whilst authors in the Gordon 1997 study mentioned contamination as a difficulty in their discussion. St Pierre 1992 provided the intervention to boys and girls clubs, a setting in which authors believe a natural 'booster programme' effect may have occurred for both prevention groups, thus making the two treatment groups similar. In addition, 87% of the 'SMART only' and 87% of the 'controls' reported learning about alcohol and other drugs from an intervention programme at school. For the Tang 1997 study, authors mention a possibility that little difference existed between the extent of exposure for intervention and control conditions. Furthermore, a comprehensive programme aimed at reducing the sale of cigarettes to minors was implemented in the control in Northern Sydney during the closing stages of the evaluation. Finally the Winkleby 1993 study had possible contamination due to one control city banning public smoking in 1990 which subsequently produced a large decline in smoking. One‐third of survey respondents for this study did not live in the treatment cities during the entire intervention period. Although authors adjusted for this in their analysis the results did not change. Six studies were adequately protected against contamination (Perry 1994; Vartiainen 1998; Biglan 2000; Hancock 2001; Perry 2003; Winkleby 2004), whilst the remaining 12 studies had unclear protection against contamination.

Selective recruitment of participants:

Selective recruitment of participants were unclear in 18 studies and a high risk of bias in the remaining seven (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992; Piper 2000; De Vries 2003; Winkleby 2004; Hawkins 2009; Klein 2009). Possible selective recruitment occurred through subjects volunteering to take part in the evaluation, subjects selected by school teachers or by study staff.

Other risks of bias:

Two studies were identified as having other possible threats to validity. In Piper 2000, authors found significant differences between the different proposed methods of analysis used for the same data. As such they presented the results with 'the least amount of bias in the estimates of the standard errors due to the design effect'. The other study, D'Onofrio 2002, had a significant gap between study completion and publication of results (12 years). In addition authors state that different interventions were delivered to each intervention group and the full intervention as it was intended was not delivered, with an average delivery of 67%. The Baxter 1997 and Elder 2000 studies provided insufficient information to permit judgement of 'yes or no', while the remaining 21 studies had no other sources of bias identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Intervention effectiveness was assessed in all 25 included studies through smoking prevalence, in addition to a mixture of secondary outcomes including behaviours, attitudes, perceptions and knowledge. The data was analysed as per the pre‐defined methods described in 'Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity'. For a summary of intervention effectiveness for each of these outcomes see Table 2.

1. Summary of intervention effectiveness.

| Study ID/ n‐values | Outcome Results (comparing intervention to control): | ||||

| Smoking | Behavioural intention* | Attitudes | Perceptions | Knowledge | |

|

Baxter 1997 Clusters n=4 (high‐schools) plus unknown number of primary‐schools (n=13 for intervention group only) Individuals n=1503 (mean from cross‐section x2 time points) 36‐months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Biglan 2000 Clusters n=16 (communities) Individuals n=4450 (mean from cross‐section x5 time points including baseline) 12‐months (SI) |

Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Not significant | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Not significant | ‐ |

| 36‐months (SI) | Not significant | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Not significant | ‐ |

| 48‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | ‐ |

|

D'Onofrio 2002 Clusters n=78 (community clubs) Individuals n=1590 (mean from cross‐section x3 time points) 9‐months (SI) |

Not significant | Favours intervention | Not significant | Favours intervention | Favours intervention |

| 24‐months (SI) | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant |

|

De Vries 2003 Clusters n=235 (schools) Individuals n=23531 (Also see Table 4 and footnote) 12‐months |

Overall not significant; Favours intervention 2/6 countries; Favours control 2/6 countries | Overall not significant; Favours control 2/6 countries | Overall not significant; Favours intervention 1/6 countries | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Overall not significant; Favours intervention 2/6 countries | Overall not significant; Favours intervention 1/6 countries; Favours control 1/6 countries | Overall favours intervention; Favours intervention 3/6 countries | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30‐months (SI) | Overall favours intervention; Favours intervention 2/6 countries | Overall not significant; Favours intervention 2/6 countries | Overall not significant; Favours intervention 2/6 countries | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Elder 2000 Clusters n=25 (schools) n=17 (school districts) Individuals n=660 2‐months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ |

| 12‐months (SI) | Not significant (GEE); Favours intervention (time x treatment of 'susceptible' cohort) | ‐ | Not significant (GEE); Favours intervention (time x treatment for tobacco‐anticipated outcomes) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Not significant (GEE); Favours intervention (time x treatment of 'susceptible' cohort) | ‐ | Not significant (GEE); Favours intervention (time x treatment for tobacco‐anticipated outcomes) | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Gordon 1997 Clusters n=8 (schools) Individuals n=1569 6‐months (SI) |

Not significant | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | ‐ | Not significant |

|

Gordon 2008 Clusters n=40 (schools) Individuals n=6276 12‐months (SI) |

Overall and Cohort‐1: Not significant Cohort‐2: Favours intervention | Cohort‐1: Not significant ( ANCOVA); Cohort‐1&2: Favours intervention (time x treatment) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Hancock 2001 Clusters n=20 (towns) Individuals n=3973 36/48‐months (SI) |

Favours control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Hawkins 2009 Clusters n=28 (school districts) n=88 (schools) Individuals n=4407 36‐months (SI) |

Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Klein 2009 Clusters n=9 (cities) n=60 (GPU's) (both intervention only) Individuals n=4230 24‐months (EI) |

Not significant | Not significant | ‐ | Not significant | ‐ |

|

Murray 1994 Clusters n=81 (schools) Individuals n=7180 36‐months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Pentz 1989 Clusters n=42 (schools) Individuals n=1607 (matched cohort) n=5065 (total) 12‐months (EI) |

Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Perry 1994 Clusters n=2 (communities) n=20 (schools) Individuals n=2401 12‐months (SI) |

Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 36‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 48‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 60‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 72‐months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Perry 2003 Clusters n=24 (schools) Individuals n=6237 24‐months (SI) |

D.A.R.E. Not significant; D.A.R.E. Plus: Favours intervention for boys only, overall not significant (Combined D.A.R.E. and D.A.R.E. Plus in meta‐analyses favour intervention) |

D.A.R.E. Not significant; D.A.R.E. Plus Favours intervention for boys only, overall not significant (Combined D.A.R.E. and D.A.R.E. Plus in meta‐analyses favour intervention) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Perry 2008 Clusters n=32 (schools) Individuals n=8369 12 months (SI) |

Not significant | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours control | Favours intervention |

| 24 months (SI) | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours intervention | Favours control (see Table 3) | Favours intervention |

|

Piper 2000 Clusters n=21 (middle‐schools) Individuals n=1981 (matched cohort) n=1677 (year ten only) 24 months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | Age appropriate HFL: Not significant; Intensive HFL: Favours intervention |

‐ |

| 36 months (SI) | Age appropriate HFL: Favours control; Intensive HFL: Not significant |

‐ | ‐ | Age appropriate HFL: Not significant; Intensive HFL: Favours intervention |

‐ |

|

Schinke 2000 Clusters n=10 (reservations) n=27 (schools) Individuals n=1396 6‐months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 18‐months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30‐months (SI) | Not significant for weekly smoking; Favours Skills only for smokeless tobacco use |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 42‐months (SI) | Not significant for weekly smoking; Favours Skills only for smokeless tobacco use |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Schofield 2003 Clusters n=24 (schools) Individuals n=4841 24 months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | Not significant | ‐ | Favours intervention |

|

St Pierre 1992 Clusters n=14 (clubs) Individuals n=377 3 months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Favours intervention |

| 15 months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Favours intervention |

| 27 months (SI) | Not significant; However on post‐hoc tests SMART Only and SMART + Boosers Favoured the intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Favours intervention |

|

Stevens 2002 Clusters n=12 (paediatric practices) Individuals n=3145 12‐months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24‐months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 36‐months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Sussman 1998 Clusters n=21 (schools) Individuals n=1578 12 months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24/36 months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 48/60 months (SI) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Tang 1997 Clusters n=27 (schools) Individuals n=4567 12 months (SI) |

Not significant | ‐ | Favours control (on data adjusted for baseline cofounders) | Not significant | Not significant |

|

Vartiainen 1998 Clusters n=6 (schools) Individuals n=897 24 months (SI) |

Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 36 months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 48 months (SI) | Favours intervention | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 96 months (SI) | Favours intervention; Except for monthly smoking which was not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 180 months (SI) | Not significant; However favours intervention for cohort of baseline non‐smokers | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Winkleby 1993 Clusters n=4 (cities) Individuals n=2605 (cross‐sectional sample of 4 cities) 12 months (from the start of the adolescent intervention) |

Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 24 months (from the start of the adolescent intervention) | Not significant | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Winkleby 2004 Clusters n=10 (continuation high‐schools) Individuals n=813 2.5 months (SI) |

Favours intervention (daily smoking only); Not significant for weekly or non‐smokers | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 6 months (EI) | Favours intervention (daily smoking only); Not significant for weekly or non‐smokers | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

* Behavioural intention = intentions to smoke in the future

SI: Follow‐up commences from the start of the intervention period

EI: Follow‐up commences from the end of the intervention period

DeVries 2003: Baseline smokers excluded from analysis; Weekly smoking at 12‐months follow‐up varied: two of the six countries showed a significant difference favouring the intervention whilst authors describe Denmark and UK as producing counter productive trends; See also Table 3, Table 4 and Effects of interventions.

Overall summary of smoking behaviour:

Overall ten interventions presented in the 25 studies demonstrated intervention effectiveness in influencing smoking behaviour including prevention, at primary follow up. One programme provided statistically and clinically significant short‐term benefits (<12 months) (Winkleby 2004) and nine provided longer‐lasting effectiveness (Pentz 1989; St Pierre 1992 (only in post hoc testing); Perry 1994; Vartiainen 1998 (up until eight‐year follow up); Biglan 2000 (for 12‐ and 48‐month follow ups only); De Vries 2003 (at 30 months only); Perry 2003 (for boys only in the D.A.R.E. Plus intervention; and when combining both D.A.R.E. and D.A.R.E. Plus groups together and comparing to control for the meta‐analysis); Perry 2008; Hawkins 2009). Two interventions favoured the control group (Piper 2000; Hancock 2001), whilst the remaining 13 studies demonstrated no significant benefit.

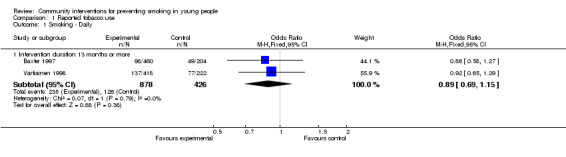

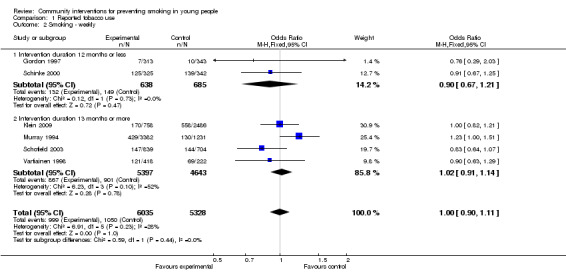

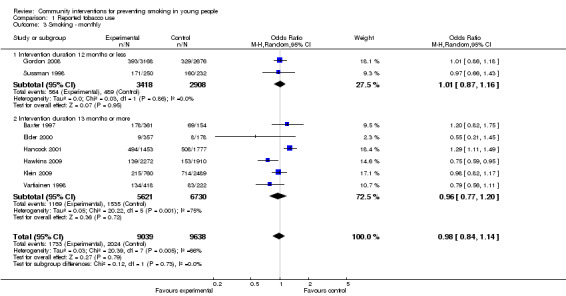

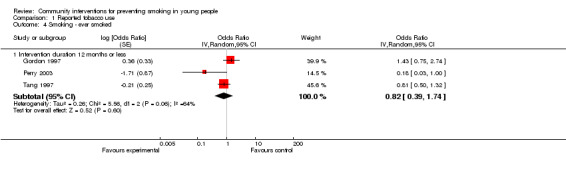

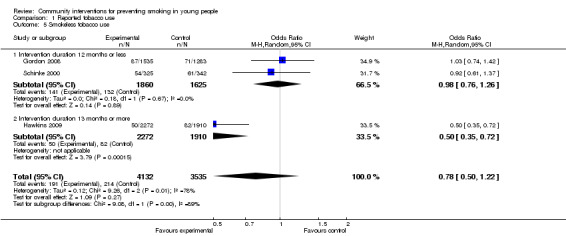

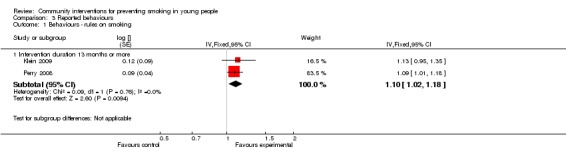

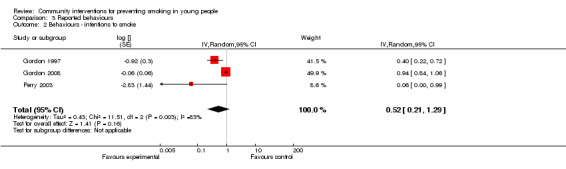

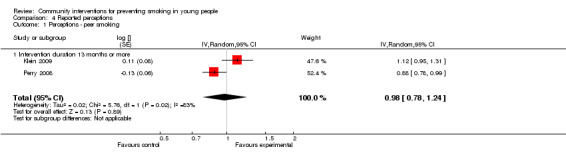

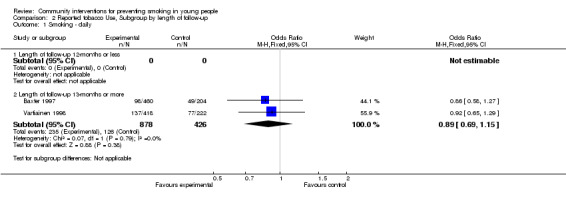

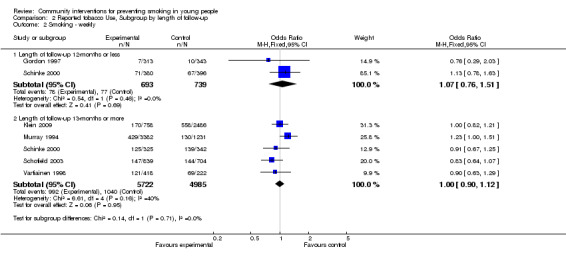

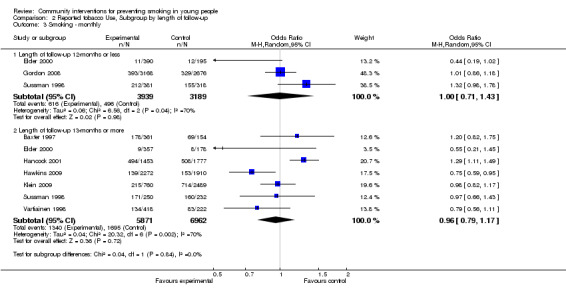

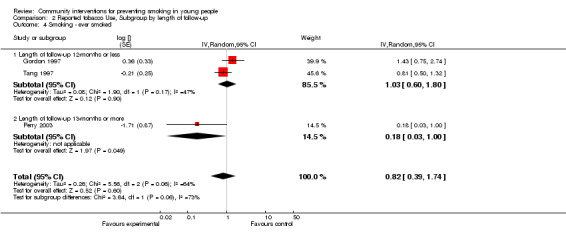

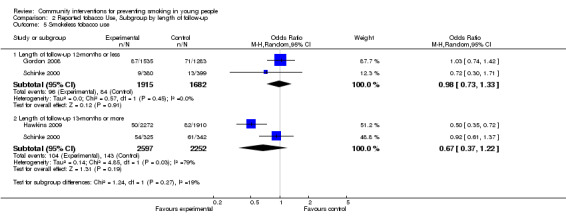

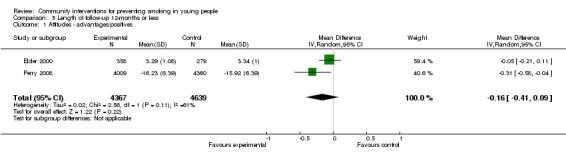

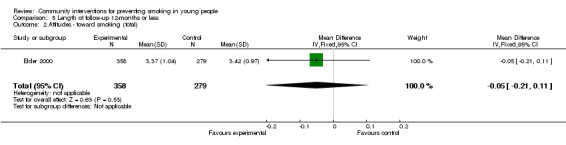

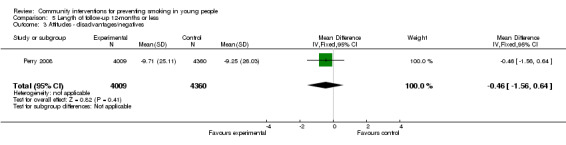

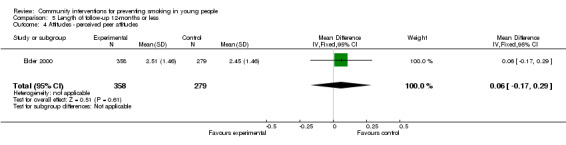

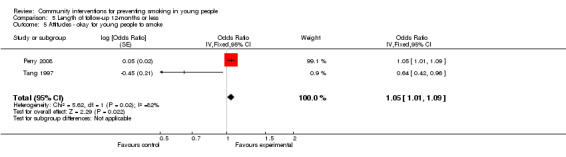

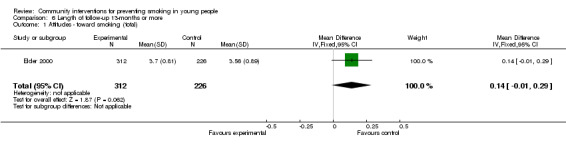

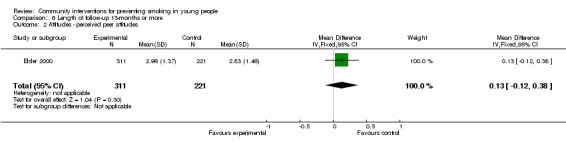

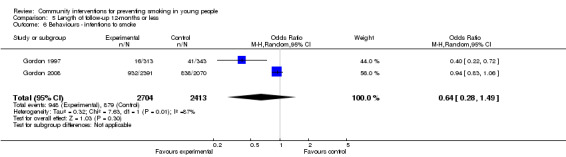

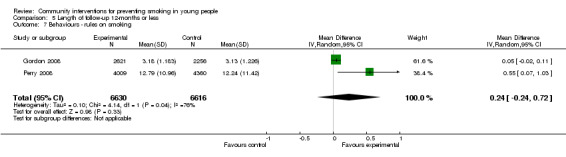

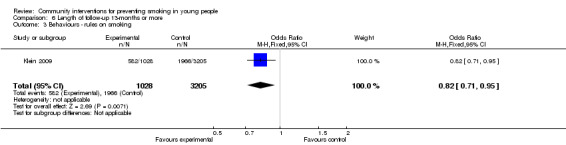

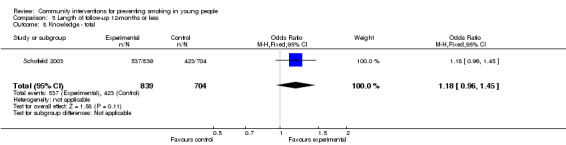

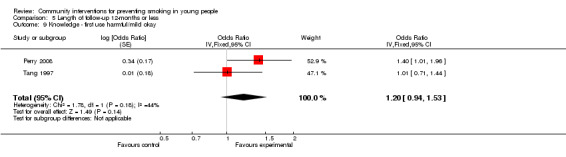

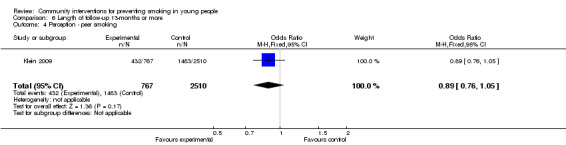

Narrative synthesis has been used to report primary outcomes, secondary outcomes and process measures for all studies (Table 3). A combination of 16 studies were able to be included in the meta‐analyses, with eight studies being the largest number of studies available for one outcome. However these results should be interpreted with caution as outcomes are only reported for studies in which data were available for meta‐analyses. Of the studies categorised as showing evidence of clinically and statistically significant benefit, only two (Vartiainen 1998, Perry 2008) reported outcomes that could be included in the meta‐analysis. Smoking was assessed as daily (Analysis 1.1), weekly (Analysis 1.2), monthly (Analysis 1.3), ever smoked (Analysis 1.4) and smokeless tobacco use (Analysis 1.5). Sub‐group analyses were conducted based on intervention duration < 12 months and > 13 months. There were no statistically or clinically significant results for weekly, monthly or smokeless tobacco use. For daily smoking and 'ever smoked' the point estimates were consistent with a clinical benefit but the number of studies were small and the confidence intervals wide (daily smoking Analysis 1.1, two studies, OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.15)), (ever smoked Analysis 1.4, three studies, OR 0.82 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.74)).

2. Summary of individual study outcomes and process measures.

| Study ID/sub‐headings: | Detailed synthesis of intervention effectiveness: |

|

Baxter 1997 Smoking behaviour: |

Cohort analysis: Smoking increased in both intervention and control areas by 20% overall; in the intervention schools the number of girls smoking increased by 29% and the number of boys by 10%, and in the control school the numbers of girls smoking increased by 24% and the number of boys by 16%. Cross‐sectional analysis: There was no evidence of any difference between intervention and control schools in the change in smoking rates between 1991 and 1994 (Chi‐square =2.6; p=0.12). |

|

Baxter 1997 Intermediate outcome data: |

None reported. |

|

Baxter 1997 Process measures: |

None reported. |

|

Baxter 1997 Comments: |

NHS costs (schools component only) estimated to be £16,350. |

|

Biglan 2000 Smoking behaviour: |

Prevalence of cigarette smoking in prior month: Using a random coefficients analysis for nested cross sectional design, the effect of the interventions were not significant. Using pair‐wise analysis of the effect from time‐1 to each of the follow‐up points, the effects of the interventions were significant at times‐2 (p=0.022) and ‐5 (p=0.038) and approached significance at time‐4 (p=0.077, 2 tailed test). The effect was calculated as the difference in the change in prevalence from time‐1 to the relevant time for the control condition, minus the same change for the school‐based‐only condition. At time‐2 the net change was 4.5% (i.e., a larger decrease in community‐participation areas), at time‐4 it was 2.4%, and at time‐5, 3.8%. Prevalence of smoking in school‐based‐only communities increased significantly from time‐1 to each of the subsequent time points. There was no significant change in the community‐participation condition, suggesting that the intervention prevented an increase in prevalence. There was no evidence that the community‐participation and school‐based‐only communities differed on expired carbon monoxide at any time points. |

|

Biglan 2000 Intermediate outcome data: |

Young people in the community‐participation group reported more negative attitudes toward tobacco use (slope t(14 df)=2.31, p=0.036). Their awareness of efforts to prevent illegal sales became significantly more positive (slope t(14 df)=‐2.31, p=0.036), Intentions to smoke over 5‐years were significantly more positive for grade 9 males in school‐based‐only communities (slope t(14 df)=2.87, p=0.0124). At time‐2 parents in community‐participation communities perceived more town support for tobacco access restrictions (8 communities). By time‐3 and ‐4, parents in the community‐participation group were aware of more efforts to reduce youth access, and perceived greater town support for access restrictions. There were significant intervention effects over time on the perception of town support for tobacco prevention, and the support of business leaders. There was no evidence of an impact on perceived support from schools or government officials. |

|

Biglan 2000 Process measures: |

After the first year of intervention, the total amount of activities over the year were correlated with the amount of change in the prevalence of any tobacco use (including smokeless tobacco), r=‐0.61, p<0.10. The correlation was not significant for time‐1 to time‐3. However, the correlation between the cumulative number of activities over the 3‐years of the intervention in each community and the community’s change in the prevalence of any tobacco use between time‐1 and time‐4 was significant, r=‐0.75, p<0.05. This correlation was apparently due to the correlation of cumulative activities with changes in smoking prevalence between time‐1 and time‐4, r=‐0.73, p<0.05 (data from an unpublished draft report). |

|

Biglan 2000 Comments: |

Time‐1 smoking prevalence was higher in community‐participation groups (approximately 10%, adjusted for covariates) than in school‐based‐only groups (approximately 8%). This difference approached but did not reach significance. From time‐1 to time‐2 there was a marked drop in smoking prevalence in community‐participation groups and increase in the school‐based only communities. An analysis of the slope for prevalence (excluding the time‐2 data) showed that the slopes did differ significantly (t(14)=‐2.79, p=0.014), even when excluding the data points offering the strongest evidence for an effect. Communities had small populations and were mainly in rural areas. Only two communities had significant numbers of students from minority ethnic groups. Parents were offered a $10 incentive to complete the questionnaire. |

|

D’Onofrio 2002 Smoking behaviour: |

None of the smoking behaviour programme effect estimates were significant at post‐test 1 or post‐test 2. |

|

D’Onofrio 2002 Intermediate outcome data: |

At post‐test 1 (9‐months) programme effect coefficients (EC) with 95% confidence intervals are used to show that youth in the programme clubs had: greater knowledge of the actual prevalence of tobacco use among high‐school students (EC+0.058; +0.021, +0.095); were more likely to report that smokeless tobacco is addictive (EC+0.168; +0.062, +0.274); the first use of cigarette is harmful to one’s body (EC+0.166; +0.019, +0.313); quitting cigarettes is difficult (EC+0.154; +0.005, +0.337); tobacco companies try to sell their products to children (EC+0.194; +0.051, +0.337); and they did not intend to smoke cigarettes in the future (EC+0.084; +0.023, +0.145); By post‐test 2 (24‐months) there were no significant results for any outcome. |

|

D’Onofrio 2002 Process measures: |

Fidelity of programme implementation varied by club from 43.0% to 85.3% with an average fidelity of 67.3% (SD=9.7). programme leaders added their own anecdotes to the curriculum approximately twice per session. The 'going further' activities were reported as being completed by 5.3% of members. |

|

D’Onofrio 2002 Comments: |

None to report. |

|

De Vries 2003 Smoking behaviour: |

For time‐1/time‐2 (12‐months) no overall effects for smoking behaviour were found using logistic regression. With regards to weekly smoking at time‐3 (24‐months), 18.4% of non‐smokers in the experimental group had begun smoking on a weekly basis compared to 18.8% in the control group. A significant overall effect for weekly smoking was found at time‐4 (30‐months) with 21.9% commencing smoking in the experimental group compared to 23.4% in the control (p=0.03). (Also see Table 4). |

|

De Vries 2003 Intermediate outcome data: |

Intentions to smoke overall were not significant at any follow‐up, though individual countries demonstrated varying results (some in favour of intervention, some control) across the three time‐periods (see Table 4). In one country (Spain), subjects were significantly less convinced of the advantages of smoking at 12‐months compared to the control, however this effect was not seen in any other country as all the respondents perceived many disadvantages and believed that smoking had detrimental effects. As such there was no overall significant differences between intervention and control, which was also the case at 30‐months follow‐up. The experimental group at time‐3 (24‐months) however, were significantly less convinced of the pros of smoking than the controls (p<0.05). By time‐4 the experimental group were more confident in cigarette refusal (self‐efficacy) than the control. |

|

De Vries 2003 Process measures: |

Intervention implementation varied significantly between countries with total number of lessons being Denmark 12, Finland 14, The Netherlands 9, Spain 18, Portugal 14 and United Kingdom 9. The activities within the ESFA projects also varied though each contained some components at the school level, parental level and out‐of‐school level. |

|

De Vries 2003 Comments: |

Random assignment was not possible in the Netherlands and Spain. |

|

Elder 2000 Smoking behaviour: |

No between‐group results were significant. 30‐day smoking started and remained at very low levels throughout the 2‐years; The highest group prevalence at any measurement period was 4.7% with 2.5% being the lowest. Smoking prevalence in those susceptible (susceptibility defined as a combination of outcomes designed by the authors) to smoking reduced by nearly 40% in the attention‐control group and by 50% in the intervention group from baseline to 2‐year follow‐up. The overall reduction in subjects 'susceptible to smoking' from immediate post‐intervention to 2‐years was statistically significant (definition of susceptible subjects included those who were current smokers, did not show a firm resolve not to smoke, would accept a cigarette from a friend or intended to smoke in the next year). Older children were more likely to smoke and boys were significantly more susceptible than girls to smoking. |

|

Elder 2000 Intermediate outcome data: |

Tobacco peer norms, tobacco self‐standards and communication with parents all had no significant interactions and no significant intervention effects when the interaction terms were dropped (GEE results). Tobacco‐anticipated outcomes for the time‐by‐treatment analysis was statistically significant. Authors state this interaction was due to the discrepancy in the difference between control and intervention at time‐2 (‐0.05) compared to differences seen at time‐3 (0.19) and time‐4 (0.14). |

|

Elder 2000 Process measures: |

A significant dose‐response relationship with respect to susceptibility to smoking was seen as dose increased in the intervention group, which was not seen in the attention control group (p=0.036). |

|

Elder 2000 Comments: |

None to report. |

|

Gordon 1997 Smoking behaviour: |

At 6‐months there were no significant differences in smoking prevalence between the control group and the intervention group. After the intervention period the number of non‐smokers reduced by 13%, ever smokers increased by 5% and weekly smokers increased by 3%, however these results were not significant between groups. |

|

Gordon 1997 Intermediate outcome data: |

Number of students who did not intend to smoke fell by 8% (from 62% to 54%) in the intervention group and by 17% (from 69% to 52%) in control group (p=0.01). There were marginal increases in knowledge in both groups and significant influences on attitudes (overall attitudes toward smoking). Purchasing cigarettes from retailers was more difficult, 12‐ out of 17‐students were refused in the intervention group compared to 5‐ out of 13‐students in the control group. |

|

Gordon 1997 Process measures: |

Various anti‐smoking activities in the community were encouraged such as: community police officers reminding retailers of their obligations regarding the sale of cigarettes to minors and posters and leaflets displayed in general practitioner practices. |

|

Gordon 1997 Comments: |

In the control group compared to the intervention group at baseline there were more non‐smokers (70% vs 63%), fewer occasional smokers (17% vs 21%), and less regular smokers (0% vs 2%). It is unclear whether the pupils in the control schools might have been contaminated by community initiatives in the catchment areas of the intervention schools |

|

Gordon 2008 Smoking behaviour: |

No intervention effect was found for smoking prevalence for either cohort using the mixed‐model ANCOVA, p=0.4010 or the time‐by‐condition analysis (p=0.5716). A statistically significant effect was found for cohort‐2 (ANCOVA ‐0.042, t=‐2.59, df=18, p=0.0187), representing a 4.2% reduction in smoking prevalence in intervention schools after controlling for pre‐test smoking. Cohort‐2 exhibited an 11.2% increase in smoking prevalence in control schools and a 7.1% increase in intervention schools. There was no intervention effect on smokeless tobacco use (assessed for males only) across both cohorts (p=0.9349) or in cohort‐2 (p=0.9058). |

|

Gordon 2008 Intermediate outcome data: |

No intervention effect was found for susceptibility using a mixed model ANCOVA (p=0.1147), however the time‐by‐treatment analysis indicated a marginal reduction (‐0.072, t=2.12, df=37, p=0.041). Cohort‐2 schools however significantly differed by condition for susceptibility according to both the mixed‐model ANCOVA (‐0.08, t=‐2.45, df=18, p=0.0245, partial r=‐0.50) and the time‐by‐treatment analysis (‐0.098, t=‐2.92, df=17, p=0.0096, partial r=‐0.58). The interaction between condition and cohort was not significant (ANCOVA p=0.077 time‐by‐treatment p=0.1331). The intervention had no significant effect on smoker image (i.e., the condition did not affect student’s images of smokers), though in cohort‐2, sixth grade smoker image was significantly associated with eighth grade 30‐day smoking (0.04, t=2.93, df=1,479, p=0.0034, r=0.08) Sixth grade reports on house smoking rules were significantly related to eighth grade 30‐day cigarette use across cohorts, even after controlling for baseline smoking (‐0.019, t=‐4.87, df=3,406, p<0.0001, r=‐0.08). There was no evidence that intervention effects were mediated by effects on house rules for the combined sample or cohort‐2. |

|

Gordon 2008 Process measures: |

None reported. |

|

Gordon 2008 Comments: |

Analysis conducted on 60% Intervention and 59% Control. |

|

Hancock 2001 Smoking behaviour: |

Smoking prevalence (4‐week) increased over time in all towns, and intervention towns showed a greater increase (outcome significantly favoured control). Girls showed the greatest net difference, 5%, but this was not significant (p=0.2). |

|

Hancock 2001 Intermediate outcome data: |

None reported. |

|

Hancock 2001 Process measures: |

At time‐2 only 2588 students answered questions about anti‐smoking activities. In the past 2‐years 74.6% of intervention and 70.8% of control groups were aware of anti‐smoking activities (difference not significant, p=0.5). Of students aware of campaigns, 30.1% had smoked in the past month, of those not aware 28.6% had smoked, (relationship not significant, p=0.5). |

|

Hancock 2001 Comments: |

Sample size was reduced at time‐2, with fewer boys included. About 10% of surveys contained some nonsensical responses and were not included. The lack of difference in awareness of anti‐smoking actions may indicate that many similar activities were occurring in control towns and schools. A survey of school principals supported this for school activities. |

|

Hawkins 2009 Smoking behaviour: |

A mixed‐model analysis of covariance for smokeless tobacco use in the last 30‐days showed significantly higher prevalence rates in the eighth grade for control communities, compared to intervention communities (t8=3.23, p=0.01 [2‐tailed], adjusted odds ratio =1.79). Eighth grade student smoking prevalence (30‐day use) did not differ significantly across groups (t8=1.47). |

|

Hawkins 2009 Intermediate outcome data: |

None reported. |

|

Hawkins 2009 Process measures: |

Over the 2‐years adherence improved for most programmes with rates averaging 91% in 2004‐2005 and 94% in 2005‐2006. Only one programme decreased in adherence over the 2‐years from 93% to 54% (programme Development Education). The highest dosage scores were in the parent training and after school programmes with all programmes averaging at least a 4.0 on a 5 point quality delivery score. Average delivery scores in 2004‐2005 were 4.38 and in 2005‐2006 they were 4.59. |

|

Hawkins 2009 Comments: |

None to report. |

|

Klein 2009 Smoking behaviour: |

The intervention had no significant effect on monthly or weekly smoking compared to control. Smoking prevalence rates across both cohorts increased from 12% at baseline to 29% at 5‐year follow‐up for monthly smoking and 8% at baseline to 22% at 5‐year follow‐up for weekly smoking. |

|

Klein 2009 Intermediate outcome data: |

Parental smoking and close friend smoking increased the odds of past month smoking by 40% and nearly 100% respectively). Rules on smoking at home were significantly associated with a 12% reduction in the odds of past month smoking. Friend smoking status rendered a more powerful influence on smoking behaviour than the intervention (clean‐indoor‐air) policy with youth. Youth with close friends who smoked were more likely themselves to smoke compared to youth with no close friends that smoked. |

|

Klein 2009 Process measures: |

The number of participants living in an area with a clean‐indoor‐air policy were 1028. No other information provided. |

|

Klein 2009 Comments: |

None to report. |

|

Murray 1994 Smoking behaviour: |

Authors report no significant differences in tobacco use incidence or prevalence rates at 36‐months follow‐up, nor was there any evidence of a dose‐response relationship in the four‐group comparison study data set. There was a marginal (p=0.05) difference in favour of control when the three intervention groups were combined as one, when meta‐analysing data for this review (odds ratio 1.23 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.51). |

|

Murray 1994 Intermediate outcome data: |

Pro‐smoking messages were stable; anti‐smoking messages more frequently reported by Minnesota youth in 4 of 5 media types tested. Frequently expressed strong anti‐tobacco beliefs were stable over time. Increases in exposure to anti‐smoking messages had little effect on smoking related beliefs. |

|

Murray 1994 Process measures: |

In 1989 and 1990, 95% of participants saw or heard at least one advertisement; On average advertisements were seen or heard 50‐times per year, per person. |

|

Murray 1994 Comments: |

Minnesota students had significantly fewer peers, family or friends who smoked, which did not change over the 5‐years. |

|

Pentz 1989 Smoking behaviour: |