Abstract

Endophthalmitis is one of the most severe ocular emergencies faced by ophthalmologists worldwide. Without prompt treatment significant visual loss is inevitable. With increased understanding of the science of endophthalmitis, recent studies have shown a clear role of early and more definitive surgery to achieve better visual and anatomic outcomes. Surgery in endophthalmitis encompasses a whole gamut of interventions. There are diagnostic procedures like anterior chamber tap and vitreous biopsy or therapeutic procedures like complete pars plana vitrectomy and retinal detachment repair. Current literature is deficient on a detailed description of the spectrum of surgical interventions in endophthalmitis. In the current communication, we summarize the studies based on various surgical interventions in endophthalmitis. We also elaborate in detail on each surgical maneuver, taking the reader through the nuances of each surgery via an exhaustive description and appropriate photos and surgical video clips.

Subject terms: Eye manifestations, Uveal diseases

Abstract

眼内炎为全球眼科医生面临的最严重的眼科急症。若不及时治疗, 将不可避免地导致严重的视力丧失。随着对眼内炎了解的不断加深, 最近的研究表明, 病程早期和更加完善的手术治疗对患者的功能以及解剖预后疗效显著。眼内炎手术形式多样。在诊断方面, 可进行前房穿刺和玻璃体活检;在治疗方面, 可行彻底的经睫状体平坦部玻璃体切除和视网膜脱离复位术。目前缺乏对眼内炎手术干预范围的详细描述的文献。就目前的研究现状, 本文总结了各种基于眼内炎手术干预的临床研究, 并详细阐述了手术操作的步骤, 并通过详细解读、术中图片以及剪辑的手术视频, 使读者了解每一次手术的细微差别。

Introduction

Endophthalmitis is an ocular emergency. With delay, the chances of salvaging the eye can decrease exponentially. There are reports of a higher requirement of evisceration (up to 12.84%) with delayed treatment in postoperative endophthalmitis [1]. The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS), conducted in the early 1990s, prospectively compared the medical (vitreous tap and injection of antibiotics) and surgical management (PPV and injection of antibiotics) in acute post-operative (Cataract and secondary intraocular lens) endophthalmitis [2]. EVS reported no additional benefit of vitrectomy in eyes with the presenting visual acuity (PVA) of hand motions (HM, measured as the movement of hand at one meter) or better. However, it is pertinent to note that vitrectomy was considered complete if at least 50% of the vitreous gel was removed in the PPV groups. Since then, several investigators from different countries have reported increased use of and benefit from early and near complete vitrectomy [3–5]. Surgery is an integral component of endophthalmitis management, from diagnosis (anterior chamber or vitreous fluid collection) to removing exudative membrane in the anterior chamber to crystalline lens management to vitreous surgery.

The current communication is a descriptive analysis of various scenarios in which a surgical intervention in endophthalmitis becomes pertinent. This includes the surgical nuances of each scenario. Existing literature on the same is also reviewed along with our viewpoints.

Surgical maneuvers in endophthalmitis

Various surgical maneuvers that are used in endophthalmitis management are discussed in detail in the text below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Surgical maneuvers used in endophthalmitis.

| 1. | Corneal abrasion |

| 2. | Anterior chamber tap |

| 3. | Anterior chamber exudative membrane removal |

| 4. | Intra Ocular Lens explantation |

| 5. | Lens abscess removal |

| 6. | Vitreous tap |

| 7. | Vitreous biopsy |

| 8. | Pars Plana vitrectomy |

| 9. | Subretinal abscess drainage |

Corneal abrasion

Corneal clarity is often compromised in acute setting of endophthalmitis. This occurs due to the concurrent presence of corneal edema. This can cause visual restrictions in surgical interventions. This issue can be circumvented to an extent by doing a controlled corneal abrasion.

Technique

A cotton bud can be used to scrape and roll up the corneal epithelium. Alternatively, a toothed forceps can be used to initiate the scape and can be continued with a non-toothed forceps. A viscoelastic can be applied over the epithelium to ensure a smooth scraping.

Anterior Chamber (AC) tap

AC tap is a diagnostic procedure that involves sampling the aqueous humor. The diagnostic yield from an AC tap is lower than a vitreous tap [6]. However, it’s a preferred first diagnostic test given its ease of performance. It can be undertaken as an office procedure using a slit lamp or in the operating room (OR) using an operating microscope along with other procedures.

Technique

After fixing the eyeball with forceps on the opposite quadrant, a 26 G needle attached to the syringe is inserted parallel to the iris and just anterior to the limbus. This avoids crossing the pupil and prevents inadvertent lens touch. As soon as the needle tip is inside the AC, about 0.1 ml of aqueous fluid is collected by a controlled manual aspiration, keeping the bevel of the needle facing the iris.

An advantageous technique is to press the center of the cornea with a moistened cotton tip during the aspiration. This helps push the aqueous humor towards the angles, making the periphery deeper; it helps increase the fluid aspiration into the needle and, at the same time, protects the crystalline lens from an inadvertent touch.

AC exudative membrane removal

The AC exudates, hypopyon, or sometimes fibrinous membranes need to be removed to improve the visualization of the posterior segment and for microbiological tests.

Technique

Two limbal corneal incisions are made at a distance of 4–5 clock hours apart. An ophthalmic viscoelastic device (OVD) is injected into the AC to deepen the anterior chamber and loosen the potential adhesions of the membranes. Alternatively, the balanced salt solution can also be used to irrigate the AC. Another option is to use bimanual irrigation and aspiration cannula.

A vitrectomy cutter, the cutting port facing the membrane, can be used to remove the adherent thick membranes. It can be used in aspiration-only mode to loosen the membranes, and then, with cutting mode, the membranes can be aspirated in a controlled manner. Care is taken to visualize the opening of the cutter to prevent inadvertent injury to the cornea, lens, or iris. An intraocular forceps with a large platform, like McPherson forceps, is a good alternative. A 26 G needle can also be used to aspirate and engage the edge of the membrane, which can then be removed from the surface of the iris in a “capsulorhexis manner.” As the membrane separates from the underlying iris, pigmentation seen on the undersurface of the membrane being peeled indicates a complete removal of the same (Fig. 1, Supplementary Video 1).

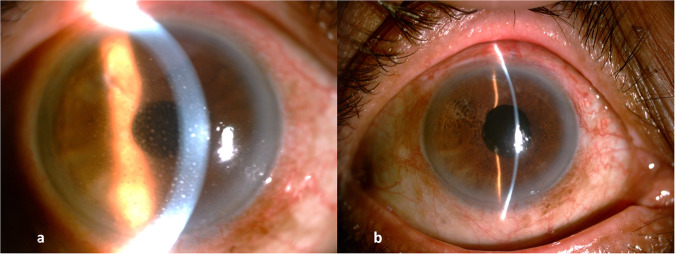

Fig. 1. Pre and post slit lamp photo of anterior chamber membrane cleared in endophthalmitis.

a Anterior chamber full of exudates. b Exudates cleared.

Intraocular lens (IOL) explantation

In delayed-onset endophthalmitis and situations where primary management with intravitreal and intracapsular antibiotics does not work, the explantation of IOL becomes unavoidable. Also, in cases with complicated cataract surgery where the IOL is dislocated or malpositioned, the explantation of the IOL becomes necessary. It is many times indicated in fungal endophthalmitis recalcitrant to vitrectomy and intravitreal antifungal agent injection. When the IOL is explanted, particularly in delayed-onset endophthalmitis, appears to reduce the number of intravitreal injections and improve functional outcomes [7].

Technique

It is ideal to explant the IOL with the bag. Foldable IOL is explanted through a corneal tunnel, and a non-foldable IOL is explanted through a pre-fashioned scleral tunnel.

The first step is to inject OVD into the AC. The IOL is then bisected in the AC and removed through the corneal wound. In the case of non-foldable IOL, it is dialed into the AC after making a scleral tunnel, then held with non-toothed forceps and explanted through the scleral tunnel. An endo illuminator introduced through a scleral port can be used as a support to prevent inadvertent IOL displacement into the vitreous cavity and, at the same time, to nudge the IOL into the AC. Once the IOL is explanted, the bag remnants can be held in a McPherson’s forceps and removed in toto (Fig. 2, Supplementary Video 2). It’s ideal to plate the IOL and the bag directly into a blood or chocolate agar plate for microbiological work-up.

Fig. 2. Pre and post slit lamp photo of IOL explantation for low-grade endophthalmitis.

a Low-grade endophthalmitis with keratic precipitates with IOL. b IOL explanted.

Lens abscess removal

When a breach in the lens capsule occurs, microorganisms gain access to the lens cortex. This can act as a nidus for an infection called a lens abscess [8]. It appears as a focal or diffuse yellowish or creamy infiltrate within the lens matter well demarcated from the lens matter. Once confirmed clinically, removing the lens nucleus becomes inevitable for controlling the infection. (Fig. 3)

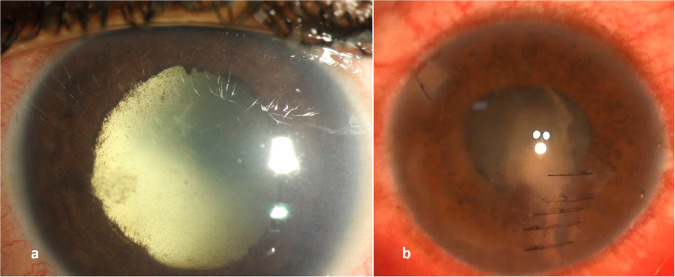

Fig. 3. Slit lamp photograph demonstrating different cases of lens abscesses.

a A deep lens abscess secondary to endogenous endophthalmitis. b A superficial lens abscess secondary to open globe penetrating injury.

Technique

The route of lens removal is planned based on the density of the nucleus. A softer nucleus can be removed with a lens aspiration using bimanual irrigation and aspiration cannulae through an anterior approach. 23 G or 25 G cutter can also aspirate the lens nucleus through the anterior or pars plana approach (Video 3). In a denser nucleus, a scleral tunnel can remove the nucleus along with the capsular bag in toto. It is necessary to avoid spilling the fragmented lens matter into the vitreous cavity. The retrieved lens matter can be directly plated into a blood or chocolate agar plate.

Vitreous tap

Vitreous aspiration by needle tap can be done as an office procedure. There could be a concern about the potential vitreous incarceration, leading to retinal detachment. However, one study found it a safe clinical procedure to generate an adequate sample in about 92% of cases [9]. It is also superior to AC fluid for yield of microorganisms [10].

Technique

Vitreous tap can be done as an office procedure. Under aseptic conditions and topical anesthesia, a 23-guage or 25-gauge needle is inserted 4 mm (phakic eyes) or 3.5 mm (pseudophakic eyes) behind the limbus into the middle of the vitreous cavity, pointing to the optic disc (approximately 7–8 mm deep). The aim is to aspirate 0.3–0.5 ml of vitreous fluid.

The butterfly needle technique described by Raju and Das is a safer alternative [11]. A butterfly needle, consisting of a 19 mm, 233/4-gauge needle attached to a flexible tubing measuring 300 mm, can be used to aspirate the vitreous sample. The surgeon squeezes the wings of the butterfly, and it is held stable by the surgeon’s dominant hand.

Vitreous biopsy

This technique uses a vitrectomy cutter instead of a needle for collecting the vitreous sample. The needle aspiration could be quick but a potential cause for traction as there is only aspiration and no cutting of the vitreous. Also, since only the syneretic portion of the vitreous can be aspirated, the chances of dry tap also increase. The advantage of vitreous biopsy over the vitreous tap is that it reduces the potential risk of vitreous traction by cutting the traction and aspiration. It also ensures a good yield as the gel portion of the vitreous is also aspirated.

Technique

If an AC paracentesis is planned along with a vitreous biopsy, placing the sclerotomy before the paracentesis is advisable, as canula insertion will be challenging in hypotonous eyes. A bevelled bi-planar sclerotomy is made either supero-nasally or supero-temporally. This ensures that the conjunctival and sclerotomy openings are offset, and these become self-sealed after the removal of the instruments. A 1 ml syringe is attached to the aspiration line. The vitrectomy cutter is placed in the mid-vitreous cavity, and the vitreous is cut with simultaneous manual aspiration is made until an adequate sample is collected (Supplementary Video 4). A cut-rate between 5000–10,000 is recommended to avoid morphological alteration of the sample. Active suction of the syringe should be done once the cutter is out of the vitreous cavity to prevent a collapse of the globe.

Instead of the one-port technique, two-port technique can prevent globe collapse. This is especially important when a high-volume of sample is needed, or the infusion line is first secured in the usual manner in the infero-temporal quadrant. But the infusion cannula is turned off till the vitreous biopsy sample is obtained. It is turned on at the end of the biopsy to prevent the globe from collapsing. Instead of a second sclerotomy for infusion, an anterior chamber maintainer can be placed in case of aphakia or pseudophakia effectively making it a single port procedure.

Alternatively, air can be used in the infusion to pressurize the eye before the start of surgery. This can ensure a larger sample, even up to 2 ml, without globe collapse [12]. Instead of one port or two ports technique, the preferred method is a three ports technique, as a thorough vitrectomy, to the extent possible at the earliest, can significantly reduce the infective load. A portable vitrector is also described for office vitreous biopsy [13].

Pars plana vitrectomy

The EVS recommended removing up to 50% of the vitreous. In the last three decades since the EVS was conducted, the PPV technology has changed to smaller gauge instrumentation, measured fluidics, and improved viewing systems. Today, an early and near complete vitrectomy is recommended if the media opacity allows it [14, 15].

Technique

Insert the trocars in the pars plana (3.0–4.0 mm from the limbus, depending on lens status) using a bevelled incision technique. An anterior vitrectomy is performed, followed by a core vitrectomy. The granular appearance of vitreous exudates facilitates adequate visualization of vitreous. If the microbial diagnosis has confirmed a non-fungal etiology, triamcinolone may be used for visualization of the vitreous.

Although core vitrectomy is quick as it decreases only the central bulk of the vitreous and is safe as it averts posterior vitreous detachment-related risks, the risk of maculopathy due to exudates is not averted, leading to poor visual outcomes. Hence, complete and early vitrectomy, including creating a PVD and removing all, but especially the posterior vitreous, should be a priority (Supplementary Video 5). This allows better infection clearance, better assessment of the retinal surface and potentially decreases vitreoretinal interface sequences once endophthalmitis resolves.

Subretinal abscess drainage

A subretinal abscess occurs in endogenous endophthalmitis when a pathogen reaches the choroid via the bloodstream following a breach in the blood-retinal barrier that reaches the retina and, sometimes, the vitreous cavity [16–18]. Surgical options are pars plana vitrectomy with retinotomy or retinectomy.

Technique

Needle drainage is the preferred technique for the management of the subretinal abscess. A standard 23 G or 25 G vitrectomy is completed. An elevated and relatively avascular area over the abscess is identified. A 41 G needle is used to make a retinotomy over the identified area. The abscess is slowly drained, debulking the abscess to the extent possible (Supplementary Video 6). Venkatesh et al. described a technique using the 41 G needle to inject antibiotics into the subretinal abscess recalcitrant to intravitreal antibiotics.

For the retinectomy technique, after completion of vitrectomy, the area with subretinal abscess is demarcated with diathermy. Cutter is used to perform retinectomy through the cauterized retina, allowing access to the sub-retinal space. The abscess can then be drained with the cutter in aspiration mode.

Surgical challenges in endophthalmitis

Hypotony

The causes of hypotony in endophthalmitis could be active wound leaks, choroidal detachment, retinal detachment, reduced ciliary body function, and ciliary body detachment from choroidal effusion or cyclitic membranes [1].

In case of a history of trauma or prior surgery, wound exploration should be done before introducing the trocars to look for any wound leak. If present, the leak should be secured before entering the vitreous cavity. We suggest the following steps:

Introduction of the trocars, the first step in any vitreo retinal surgery, is challenging in a hypotonous eye. The core principle of trocar insertion is to create a valve-like effect that helps in wound apposition [19]. The usual practice is to insert the trocar intrasclerally at 45° to the surface, changing the direction tangential to the ocular surface once the sclera is fully penetrated. In a hypotonous eye, too much maneuvering will cause globe collapse, and entry will be difficult. Hence, we can attempt a vertical stab incision. Once the infusion cannula is secured and the intravitreal location of the cannula tip is confirmed, the infusion can be started to overcome the hypotony, and the rest of the trocars can be introduced in the usual oblique manner.

Injecting balanced salt solution into the vitreous cavity with a 29 G needle before insertion of the cannula is another technique to overcome the hypotony. This firms up the globe, allowing a smooth entry of the trocars for the insertion of the instruments.

Drainage of large choroidal detachments restores proper ciliary body apposition with a normal return of intraocular pressure (IOP). Repair of retinal detachment, with or without silicone oil, and excision of anterior vitreoretinal membranes, removal of anterior loop traction, and cyclitic membranes can elevate IOP to a functional range.

A preoperative ultrasonography can be used to guide the choice of sclerotomy site especially in cases of choroidal or retinal detachment.

Media haze

One of the biggest challenges in endophthalmitis surgeries is the media haze. Both anterior chamber inflammation and vitritis can hamper the visualization of the tip of the infusion cannula in the vitreous cavity, which is mandatory for the initiation of the vitrectomy. Various maneuvers, some of which already described by us, can be useful guides.

Infusion of air instead of fluid and visualization of the air bubble in the retrolenticular space can confirm the proper insertion of the infusion cannula.

Tactile confirmation of the infusion cannula tip can be done with the help of a light pipe introduced from the opposite quadrant.

OVD injection into the vitreous cavity can help displace some retrolenticular opacities, improving visualization.

Endoscopic surgery/hybrid approach can be done in case the anterior segment prevents the posterior segment visualization (Video 7, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. A case of endophthalmitis post open globe injury with hazy cornea which underwent endoscopic vitrectomy.

a Pre operative photo showing corneal edema. b Post operative photo showing corneal edema resolved with a residual scar.

Surgical dilemmas in endophthalmitis

Silicon oil related

Dave et al. have examined the benefits of silicone oil injection in vitrectomy for endophthalmitis when required. In an in vitro study, they found that even multidrug-resistant organisms like Klebsiella and Pseudomonas were inhibited by silicon oil. Another significant observation was that fungal growth was halted significantly, though not inhibited completely. They concluded that silicon oil can supplement the antimicrobial activities of intravitreal antibiotics [20].

It is suggested that always ensure a thorough and complete vitrectomy before injecting silicon oil. Currently, there is no consensus on the acceptable dosages of intravitreal antibiotics in silicone oil-filled eyes. During the surgery, one can inject the antibiotics before the silicon oil injection and use the standard dosage. Hegazy et al. suggested injecting up to two third of the usual dosage in silicon oil filled eyes during follow-ups [21]. Follow up of the oil-filled eye in endophthalmitis to look for resolution should be based on clinical examination. B scan ultrasonography is not very useful in an oil-filled eye.

Antibiotics related

The choice of antibiotic is easier if the culture sensitivity report of the microorganism is available. This will not be the case during the initial presentation. Routine practice is to use a combination therapy. Combining two broad-spectrum antibiotics covering gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms is the preferred choice. Surgeons should be aware of the physicochemical properties of the antibiotics used. Apart from the antibiotic choice, the frequency of intravitreal antibiotics and the end point of injections are also dilemmas in endophthalmitis management.

Inject broad-spectrum antibiotics. We use vancomycin and imipenem/colistin. Antifungals are injected when there is a strong suspicion of fungal etiology. Amphotericin B and voriconazole are our choices. Once the antibiotic susceptibility test results are available, the intravitreal antibiotic can be changed accordingly. Different syringes should be used for separate drugs to prevent precipitate formation [22].

Dexamethasone is also injected when there is no suspicion of fungal infection. Even in proven cases of fungal cause of endophthalmitis, intravitreal dexamethasone has been seen to be effective in faster clearance of inflammation [23]. We recommend systemic steroids not as a routine but as per assessment of the post operative inflammation. If the eye harbors residual inflammation post surgery then a short course of systemic steroids can be considered at 1 mg/kg body weight for 7–10 days. The usage should be avoided or should be under close monitoring with an internist in patient with a history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or an endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. A good end point to stop the steroids would be the fundus visibility of the optic disc and retina up to the second order vessels.

We re-inject after 48 h in case of non-resolution, status quo, or worsening. Serial B scan ultrasounds and slit lamp photographs are done to document the change in the intensity of the inflammation.

We stop injecting when the patient is clinically better. This is determined by the improvement in symptoms (such as pain relief) and signs (resolution of the inflammatory signs, such as a decrease in the AC cells and resolution of vitritis). The serial documentation helps to objectively assess the reduction in inflammation.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis and treatment are critical in the management of endophthalmitis. Surgical management is almost invariably required. Each case can present a unique surgical challenge based on the severity of endophthalmitis and the extent of the globe involved.

Knowledge and skill regarding the various maneuvers that can be executed in each situation helps maximize the benefit of the intervention.

Summary

What is known

Endophthalmitis often requires surgical intervention for optimal management

Surgery in endophthalmitis can be challenging in view of hazy view, edematous retina, ocular inflammation and often associated trauma

What this article adds

An understanding that different endophthalmitis scenarios require different surgical interventions

Appropriately done surgical interventions can assist in optimal management of the infection

Supplementary information

video showing the technique of vitreous biopsy

Video showing removal of anterior chamber membrane in endophthalmitis

video showing IOL explantation in a case of low-grade endophthalmitis

Video showing removal of a lens abscess following open globe injury

video showing technique of retinal biopsy under air

video showing complete vitrectomy in endophthalmitis with PVD induction

Video showing removal of a subretinal abscess

Author contributions

The study was conceived and designed by Vivek Pravin Dave and Aiswarya Ramachandran. All authors were involved in the draft, proof reading and finalizing the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Permission has been received from the patient(s) shown in Figs. 1–4 for the use of their image in published media.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-024-03089-y.

References

- 1.Dave TV, Dave VP, Sharma S, Karolia R, Joseph J, Pathengay A, et al. Infectious endophthalmitis leading to evisceration: spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens and antibacterial susceptibility profile. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2019;9:9. 10.1186/s12348-019-0174-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. A randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1479–96. [PubMed]

- 3.Kuhn F, Gini G. Vitrectomy for endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:714. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng Y, Sun W, Gu Y, Lou J, Liu W. Endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in China, 1995-2009. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1715–22. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behera UC, Budhwani M, Das T, Basu S, Padhi TR, Barik MR, et al. Role Of Early Vitrectomy In The Treatment Of Fungal Endophthalmitis. Retina. 2018;38:1385–92. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjoholm-Gomez de Liano C, Soberon-Ventura VF, Salcedo-Villanueva G, Santos-Palacios A, Guerrero-Naranjo JL, Fromow-Guerra J, et al. Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of anterior chamber tap in cases of bacterial endophthalmitis. Eye Vis. 2017;4:18. 10.1186/s40662-017-0083-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dave VP, Parmeshwarappa DC, Dogra A, Pappuru RR, Pathengay A, Joseph J, et al. Clinical Presentations and Comparative Outcomes of Delayed-Onset Low-Grade Endophthalmitis Managed with or Without Intraocular Lens Explantation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:551–5. 10.2147/OPTH.S243496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangan MS, Arıcı C, Tuncer İ, Yetik H. Isolated Anterior Lens Capsule Rupture Secondary to Blunt Trauma: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2016;46:197–9. 10.4274/tjo.85547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobo A, Lightman S. Vitreous aspiration needle tap in the diagnosis of intraocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:595–9. 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01895-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma S, Jalali S, Adiraju MV, Gopinathan U, Das T. Sensitivity and predictability of vitreous cytology, biopsy, and membrane filter culture in endophthalmitis. Retina. 1996;16:525–9. 10.1097/00006982-199616060-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raju B, Das T, FRCS The Hyderabad Endophthalmitis Research Group. Simple And Stable Technique Of Vitreous Tap. Retina. 2004;24:803–5. 10.1097/00006982-200410000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dave VP, Vithalani N, Sheba E, Joseph J, Pathengay A. Culture Positivity Rates Of Deep Vitreous Biopsy Under Air Vis-À-Vis Conventional Anterior Vitreous Biopsy In Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Retina. 2022;42:2128–33. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch FH, Koss MJ. Microincision vitrectomy procedure using intrector technology. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1599–604. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Kim HS, Yoo SJ, Choi MJ, Lew Y, Kim JW, et al. Immediate Vitrectomy for Acute Endophthalmitis in Patients with a Visual Acuity of Hand Motion or Better. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2022;36:390–7. 10.3341/kjo.2022.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong SH, Cho HJ, Kim HS, Han JI, Lee DW, Kim CG, et al. Acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: 164 consecutive cases treated at a referral center in South Korea. Eye. 2017;31:1456–62. 10.1038/eye.2017.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403–23. 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00054-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatesh P, Temkar S, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Intralesional antibiotic injection using 41G needle for the management of subretinal abscess in endogenous endophthalmitis. Int J Retin Vitreous. 2016;2:17. 10.1186/s40942-016-0043-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maguire J. Postoperative endophthalmitis: optimal management and the role and timing of vitrectomy surgery. Eye. 2008;22:1290–1300. 10.1038/eye.2008.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue M, Shinoda K, Shinoda H, Kawamura R, Suzuki K, Ishida S. Two-step oblique incision during 25-gauge vitrectomy reduces incidence of postoperative hypotony. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;35:693–6. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dave VP, Joseph J, Jayabhasker P, Pappuru RR, Pathengay A, Das T. Does ophthalmic-grade silicone oil possess antimicrobial properties? J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2019;9:20. 10.1186/s12348-019-0187-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegazy HM, Kivilcim M, Peyman GA, Unal MH, Liang C, Molinari LC, et al. Evaluation of toxicity of intravitreal ceftazidime, vancomycin, and ganciclovir in a silicone oil-filled eye. Retina. 1999;19:553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radhika M, Mithal K, Bawdekar A, Dave V, Jindal A, Relhan N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal antibiotics in endophthalmitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2014;4:22. 10.1186/s12348-014-0022-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majji AB, Jalali S, Das T, Gopinathan U. Role of intravitreal dexamethasone in exogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Eye. 1999;13:660–5. 10.1038/eye.1999.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

video showing the technique of vitreous biopsy

Video showing removal of anterior chamber membrane in endophthalmitis

video showing IOL explantation in a case of low-grade endophthalmitis

Video showing removal of a lens abscess following open globe injury

video showing technique of retinal biopsy under air

video showing complete vitrectomy in endophthalmitis with PVD induction

Video showing removal of a subretinal abscess