Abstract

We are interested in the role of asymmetric phosphate neutralization in DNA bending induced by proteins. We describe an experimental estimate of the actual electrostatic contribution of asymmetric phosphate neutralization to the bending of DNA by the Escherichia coli catabolite activator protein (CAP), a prototypical DNA-bending protein. Following assignment of putative electrostatic interactions between CAP and DNA phosphates based on X-ray crystal structures, appropriate phosphates in the CAP half-site DNA were chemically neutralized by methylphosphonate substitution. DNA shape was then evaluated using a semi-synthetic DNA electrophoretic phasing assay. Our results confirm that the unmodified CAP DNA half-site sequence is intrinsically curved by 26° in the direction enhanced in the complex with protein. In the absence of protein, neutralization of five appropriate phosphates increases DNA curvature to 32° (∼23% increase), in the predicted direction. Shifting the placement of the neutralized phosphates changes the DNA shape, suggesting that sequence-directed DNA curvature can be modified by the asymmetry of phosphate neutralization. We suggest that asymmetric phosphate neutralization contributes favorably to DNA bending by CAP, but cannot account for the full DNA deformation.

INTRODUCTION

The Escherichia coli catabolite activator protein (CAP) is a transcription factor that mediates the regulation of over 150 genes (1). CAP binds to DNA as a homodimer, in a complex with cyclic AMP (1). Binding induces an ∼90° bend in its DNA-binding site in vitro (see Fig. 1A) (2–5). DNA bending may be important in the function of CAP as a transcriptional activator: in the absence of CAP binding, replacement of the CAP-binding site with intrinsically curved A-tract DNA restores promoter activity (6,7; but see 8).

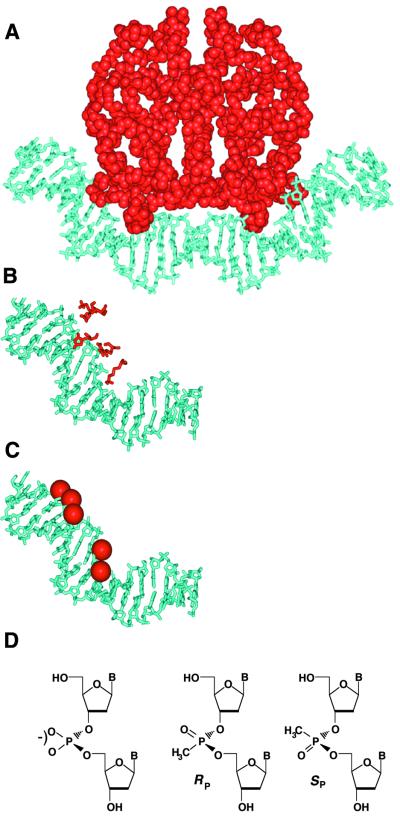

Figure 1.

Asymmetric phosphate neutralization in CAP–DNA complexes. (A) CAP–DNA structure, derived from Schultz et al. (3) and Parkinson et al. (4). CAP is shown in red, DNA in cyan. (B) Left half-site DNA, highlighting the five basic side-chains of CAP (K26, K166, R169, K188 and H199) that contact DNA phosphates [nomenclature from Parkinson et al. (4)]. (C) Modified half-site DNA. Methylphosphonate substitutions shown as red spheres. (D) Structures of anionic phosphodiester linkage (left) and neutral methylphosphonate diastereomeric linkages (right).

The molecular mechanisms by which CAP induces DNA bending are of great interest. CAP is the prototype of proteins that induce DNA bending towards the protein surface, a feature shared by the histone octamer core of the nucleosome (9). Although crystal structures identify specific atomic interactions, they do not reveal the relative energetic contributions of such interactions to binding and induced conformational changes in the protein and DNA. DNA bending over short distances is energetically unfavorable and must be compensated for by the binding free energy of the protein–DNA interaction. Obvious sources of such favorable free energy changes include counterion release from DNA, dehydration of the protein–DNA interface, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions and electrostatic forces. Favorable interactions on the protein surface have been invoked to explain extensive DNA ‘wrapping’ on proteins (10,11). In addition to these conventional forces, we have been interested in the potential role of latent DNA bending forces revealed when phosphates in the DNA double helix are neutralized asymmetrically (12,13). Our previous studies have indicated that some DNA curvature can originate from asymmetric charge neutralization without any other attractive forces applied by the protein (14–17). DNA collapse upon asymmetric charge neutralization is thought to reflect the unbalancing of small local interphosphate repulsions normally present along the DNA double helix.

To what extent does asymmetric phosphate neutralization play a role in the DNA bending observed in the complex with CAP? Gurlie and Zakrzewska used molecular modeling to explore the role of laterally asymmetric neutralizing salt bridge interactions in the CAP–DNA complex (18). Modeling of the unmodified CAP half-site predicted intrinsic DNA curvature of 38°, with the curvature being smoothly distributed along the modeled sequence. The direction of this curvature was predicted to agree with the direction of bending observed in the CAP–DNA complex. Through in silico neutralization of appropriate DNA phosphates, modeling predicted a 13° increase in DNA curvature (∼34% greater than unmodified), with no induced change in the direction of curvature. These authors also investigated the predicted sequence specificity of modification, demonstrating that the precise positioning of phosphate neutralizations was important to both the estimated DNA bend magnitude and direction.

Herein we describe an experimental measurement of the actual electrostatic contribution of asymmetric phosphate neutralization to the bending of a DNA duplex containing a single half-site CAP-binding consensus sequence (5′-TGTGA). X-ray crystal structure data (3,4) were used to assign putative neutralizing interactions between CAP basic amino acid side chains and DNA phosphates. Appropriate phosphates were chemically neutralized by methylphosphonate substitution, to mimic sites of close approach by these cationic CAP amino acids (14–16). The shape of the DNA half-site was then evaluated, in the absence of protein, before and after site-specific neutralizations. DNA shape analysis was performed using a semi-synthetic DNA electrophoretic phasing assay that allows quantitative estimation of DNA bend magnitude and direction as a function of phosphate modification (19). Our results confirm that the CAP DNA half-site is intrinsically curved in the direction enhanced in the complex with protein (5). Neutralization of five phosphates causes an ∼23% increase in curvature (from 26° to 32°). This observation demonstrates that asymmetric phosphate neutralization by CAP makes a detectable favorable contribution to DNA bending in the complex. Our data suggest that asymmetric phosphate neutralization contributes to DNA bending, but cannot account for the full DNA deformation caused by CAP binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides

Unmodified oligonucleotides were prepared by standard phosphoramidite chemistry. All oligomers were purified by denaturing 20% PAGE, eluted overnight from diced gel slices and desalted using C18 reverse phase cartridges. Oligonucleotide concentrations were determined at 260 nm using appropriate nearest neighbor molar extinction coefficients (M–1 cm–1) as described (20). Oligonucleotides containing methylphosphonate substitutions were synthesized and deprotected as described (15,21). Oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), annealed to the appropriate complementary strand and diluted to a concentration of ∼10 nM.

Trimolecular ligations

Left and right DNA arms were generated by PCR and restricted with BbsI (19). Equimolar amounts (∼1 nM final concentration) of the left arm, right arm and radiolabeled DNA duplex inserts were ligated at room temperature for 2 h, using 400 U of T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs), in a 10 µl reaction. Ligations were terminated by the addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 50 mM.

Quantitative analyses of electrophoretic phasing probe mobilities

Trimolecular ligation products (∼240 bp) were resolved on 8% native polyacrylamide (1:29 bis-acrylamide:acrylamide) gels in 0.5× TBE buffer, at 10 V cm–1 at 22°C for 5 h. Mobilities (µ) of trimolecular products were measured as the distance migrated (mm) and normalized to the average mobility of each group of five ligation products sharing the same duplex insert, but containing the five different right arms, according to:

µrel = µ/µavg 1

where µrel is the relative mobility, µ is the mobility of each ligation product and µavg is the average mobility of a group of probes sharing the same duplex insert.

The value of µrel was plotted against the spacing (in bp) between the nucleotide designated 1 in the duplex insert (see Fig. 2B) and the center of curvature of the proximal 5′ A5 tract in the right phasing arm and then fit to the phasing function (22):

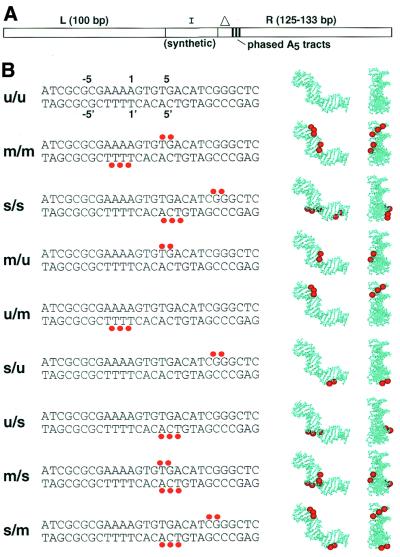

Figure 2.

Experimental design. (A) Semi-synthetic phasing probes. Phasing probes are trimolecular ligation products, containing a synthetic DNA duplex insert (I) flanked by restriction fragments (L and R). In the present study each strand of the synthetic insert was 24 bases in length. Three phased A5- tracts in the right arms are indicated as vertical black lines. Right arms differ only in the initial distance to the first A5- tract of the array, indicated by the triangle. (B) The DNA duplex inserts (I) under investigation. Red dots indicate sites of methylphosphonate substitution. Top strand sequences are shown 5′→3′ (left to right). Single letter codes (left) refer to substitutions on the top/bottom strands, respectively, where u refers to an unmodified DNA strand, m refers to a DNA strand bearing methylphosphonate residues on phosphates contacted by basic amino acids in the crystal structure and s refers to strands bearing methylphosphonates as in m, but shifted 5 bp to the right. Coordinates above and below u/u DNA strands indicate the numbering of DNA bases in the CAP half-site, as defined by Parkinson et al. (4). Molecular graphics at right depict neutralized phosphates mapped onto the DNA structure extracted from the X-ray model (left of pair is side view, right of pair is same molecule viewed in the plane of the figure, from right).

µrel = (APH/2){cos[2π(S – ST)/PPH]} + 1 2

where APH is the amplitude of the phasing function, S is the normalized spacer length, ST is the trans spacer length and PPH is the phasing period (set at 10.5 bp/turn). The value of APH estimated from curve fitting is related to the magnitude of curvature in the synthetic insert. The value of ST estimated from curve fitting allows evaluation of the direction of curvature relative to the phased A5 tract array intrinsic to the right arm.

Previous phasing assay calibration with a series of duplex inserts containing A5 tracts revealed a linear relationship between the measured phasing amplitude and the predicted degree of DNA curvature:

APH = 0.026 + 0.0047CP (r2 = 0.991) 3

where APH is the amplitude of the phasing function and CP is the predicted curvature (deflection of the helix axis in degrees) of the DNA duplex insert (19). This relationship allows direct estimation of the angle of DNA curvature from the amplitude of the phasing function.

RESULTS

Assignment of methylphosphonate substitutions

In Figure 1A we depict the structure of the CAP–DNA complex (3,4). Figure 1B illustrates the structure of the left half-site of the CAP–DNA complex and shows the five basic side-chains of CAP (K26, K166, R169, K188 and H199) that form apparent ion pairs with DNA phosphates. These DNA phosphates contacted by CAP are shown in Figure 1C as red spheres. We targeted the corresponding phosphodiester linkages (Fig. 1D) for substitution by neutral methylphosphonates (Fig. 1D).

Experimental design

We utilized a DNA phasing assay that allows quantitative estimation of DNA bend magnitude and direction (Fig. 2A) to measure the effect of asymmetric phosphate neutralization in CAP half-site DNA (19). This assay format is comparable with conventional electrophoretic phasing experiments (23,24), except that chemically modified DNA is embedded directly into longer recombinant phasing probes (19). This procedure requires far fewer modified DNA oligonucleotides than conventional ligation ladder experiments (25). As shown in Figure 2A, trimolecular ligations among a linear DNA duplex PCR product (left arm, L), a series of five different PCR products each containing a region of constant curvature (phased A5 tracts) separated by a variable spacer from the left end of the arm (right arms, R) and a synthetic DNA duplex insert (I) whose shape is to be studied (Fig. 2B; u/u to s/m) creates five different electrophoretic phasing probes. The length of DNA between the left terminus and the phased A5 tracts (providing ∼54° of intrinsic curvature) in R differs for each insert (Fig. 2A). As a result, there are five distinct helical phasings between elements in the synthetic insert (I) and the phased A5 tracts. This design allows quantitative analysis of the shape of the DNA in the synthetic insert. We demonstrated previously that this system is easily calibrated with synthetic inserts containing variable numbers of A5 tracts and is sensitive to modest alterations in DNA curvature induced by methylphosphonate substitution in laterally asymmetric patterns (19).

An unmodified DNA duplex (Fig. 2B, u/u) was designed, based on the DNA sequence used for CAP crystallization (4). As described above, inspection revealed five salt bridge interactions that were targeted for modification (Fig. 2B, insert m/m) (3,4). The contacts involve phosphodiester linkages at positions 4:5, 5:6, 1:–1′, –1′:–2′ and –2′:–3′, with amino acids R169, K188, H199, K166 and K26 [nomenclature adapted from Parkinson et al. (4)]. DNA numbering is shown above and below duplex u/u in Figure 2B. Motivated also by molecular modeling studies (18), we designed DNA duplex s/s (Fig. 2B) in which the same pattern of methylphosphonate substitutions was shifted 5 bp downstream from its position in insert m/m. Alternative pairings of appropriate top and bottom DNA strands also permitted construction of inserts m/u, u/m, s/u, u/s, m/s and s/m, in which the number and position of phosphate neutralizations differ systematically (Fig. 2B). The positions of the various neutralized phosphates are displayed in side and end views of the left CAP half-site DNA on the right of Figure 2B.

Effect of phosphate neutralization in the CAP half-site

Electrophoretic phasing analyses were employed to measure changes in mobility due to ligation of the synthetic inserts (Fig. 2B) between L and each of the five right arms R. If a curved DNA sequence is present in I, changes in the helical phasing between the two DNA elements (reference A5 tracts in R versus curvature in I) will lead to alterations in electrophoretic mobility. When curvature loci are aligned in cis, gel mobility is minimized. The extent to which gel mobility varies within each set of probes is interpreted as a measure of the magnitude and direction of DNA curvature contributed by the DNA duplex insert.

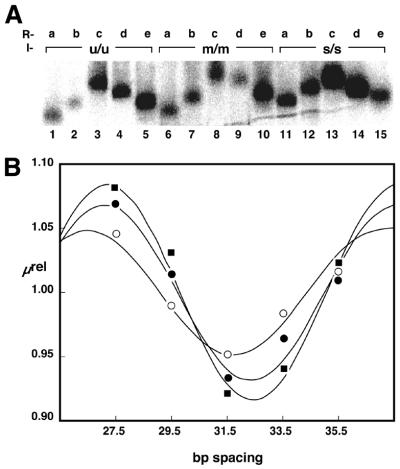

Representative data from experiments conducted with inserts u/u, m/m and s/s (Fig. 2B) are depicted in Figure 3A. Single letter codes refer to substitutions on the top/bottom strands, respectively, where u refers to an unmodified DNA strand, m refers to a DNA strand bearing methylphosphonate residues on phosphates contacted by basic amino acids in the crystal structure and s refers to strands bearing methylphosphonates as in m, but shifted 5 bp to the right. Duplex inserts were ligated between L and each of the five right arms R and electrophoresed through native polyacrylamide gels as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3A). Phasing probes containing the unmodified DNA (insert u/u, Fig. 3A, lanes 1–5) displayed strikingly different electrophoretic mobilities, confirming the presence of intrinsically curved DNA in the unmodified CAP-binding site. The gel mobility of each probe was analyzed as described previously (19,22). Relative mobility, µrel (equation 1), was plotted against the spacing (in base pairs) between the nucleotide designated 1 in the duplex insert (Fig. 2B) and the center of curvature of the proximal 5′ A5 tract in R. The results are depicted in Figure 3B (filled circles). Using techniques derived by Kerppola (22) and a set of standard probes bearing A tracts in the insert (19), the relative differences in probe mobilities were transformed (equations 2 and 3) into estimates of DNA curvature magnitudes (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Phasing assay data. (A) Image obtained after native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of phasing probes containing duplexes u/u, m/m and s/s. Identities of right phasing arms are shown, with a, b, c, d and e referring to a spacing of 27.5, 29.5, 31.5, 33.5 and 35.5 bp, respectively, between the center of curvature in the proximal A5 -tract and position 1 of the CAP half-site (Fig. 2B). (B) Quantitative analysis of electrophoretic data for inserts u/u (filled circles), m/m (filled squares) and s/s (open circles). The relative mobility of each of the five phasing probes in a given protein complex (µrel) was plotted as a function of the spacing (in base pairs) between the center of curvature in the proximal A5- tract and position 1 of the CAP half-site (Fig. 2B). Data were fit to eqution 2 as described in Materials and Methods.

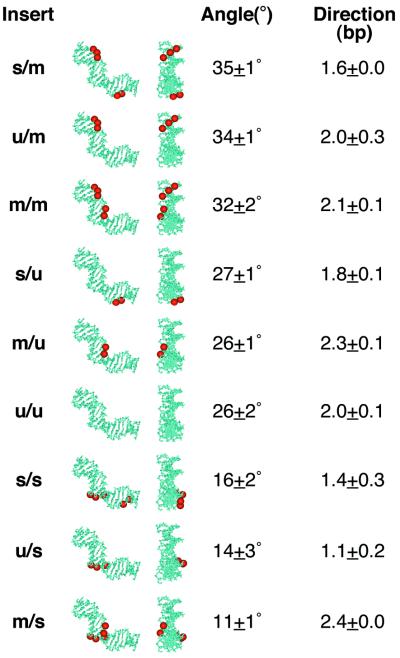

Figure 4.

Results of charge neutralization experiments. DNA inserts are ranked on the basis of apparent curvature in electrophoretic phasing experiments, from most curved (top) to least curved (bottom). Duplex designations are as in Figure 2B, followed by side and end views of the synthetic inserts with neutralizations (red) depicted on the DNA structural model extracted from the CAP/DNA X-ray structures (for clarity). Apparent bend angles were deduced from analysis of electrophoretic phasing data as in Figure 3 and are described as the average and standard deviation of at least two independent experiments. Bend direction is deduced from the curve fitting of phasing data as described in Materials and Methods. Bend direction is defined here as towards the minor groove in a reference frame centered on the indicated base pair position (as defined by the numbering shown in Fig. 2B). For reference, the primary DNA kink in the left half-site of the crystal structure is toward the major groove at position 6.5. The smaller secondary DNA kink is toward the minor groove between positions –1 and 1.

We deduced an apparent intrinsic DNA curvature of 26° based on unmodified duplex u/u. The semi-synthetic phasing assay also permits estimation of the direction of DNA curvature. This information is revealed by the spacing at which the fitted cosine function is at a minimum (Fig. 3B) (19). If it is assumed that the DNA helical repeat in the region analyzed is ∼10.5 bp/turn, the apparent bend direction in unmodified duplex u/u is towards the major groove in a reference frame centered on the base pair position designated 2.0 (numbering as in Fig. 2B). Previous experiments have provided various estimates of the intrinsic curvature of the CAP site through molecular modeling (∼38° for the CAP half-site; 18) and through cyclization kinetics (∼15° for the full site; 5). Analysis of crystal structures had assigned the primary kink in the helix axis toward the major groove at base pair 6.5 and a secondary kink toward the minor groove at position –1 to 1 (3,4). Both kinks cause bends in the same overall direction and this is within ∼30° of the direction of the intrinsic DNA curvature we detect.

A different phasing profile was observed for duplex insert m/m (Fig. 3A, lanes 6–10). The mobilities of these modified DNAs displayed a greater dependence on the position of the duplex insert in relation to the A5 tracts of R. Mobility retardation was again maximal for products containing R–C (Fig. 3A, lane 8), indicating that the loci of curvature are most nearly in phase for this probe. Quantitation of these data as described above predicts an apparent bend magnitude of 32°, a 23% increase relative to duplex u/u (Fig. 4). The bend direction was not significantly different from u/u (both centered at position ∼2.1), supporting previous experiments and models where CAP binding alters the DNA bend magnitude without changing the bend direction significantly (5,18) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 also depicts the electrophoretic analysis of probes derived from the ligation of duplex s/s between L and R. This design deliberately shifts the CAP neutralization pattern one half-helical turn away from the frame of reference of the natural CAP half-site. These ligation products (Fig. 3A, lanes 11–15) display significantly reduced phase-dependent mobility anomalies. Quantitation provided an estimated bend magnitude of 16°, a 38% decrease from the curvature of u/u (26°). The bend direction was centered at position 1.4 (Fig. 4). This result demonstrates that the neutralization pattern can predictably enhance or reduce intrinsic DNA curvature, depending on the phasing of the neutralized surface.

We performed additional experiments that altered the number and position of methylphosphonate substitutions by testing all combinations of top and bottom DNA strands (Fig. 2B). Results of these experiments are also summarized in Figure 4. Data are ordered from the largest to smallest apparent DNA bend. The data indicate that the presence of three consecutive neutralizations at positions between base pairs 1′ and –3′ consistently enhances DNA bend magnitude by 6–9° (23–35%). Interestingly, this result is relatively independent of the charge character of the other DNA strand (Fig. 4, compare s/m, u/m and m/m). When the neutralized patch was shifted by 5 bp (duplexes s/s, u/s and m/s), the DNA bend magnitude was significantly reduced. This result again largely reflected the position of the group of three consecutive neutralized phosphates and was independent of the charge character of the top DNA strand. All bend directions were centered within ∼1 bp of the curvature in u/u. Apparent DNA bend direction is obtained by the position of the minimum of the cosine function fit through the phasing data. If it is assumed that the DNA helical repeat remains constant and that bending occurs by base pair roll into a groove, the relative invariance of this minimum implies that the direction of DNA bending remains centered at nearly the same position. DNA side and end views mapping neutralization locations onto the left CAP half-site DNA are shown in columns 2 and 3 of Figure 4. Inspection clearly shows that induced bending largely corresponds to the prediction that DNA will bend toward its neutralized surface.

DISCUSSION

We used a DNA phasing assay to experimentally measure the relative contributions to DNA bending due to asymmetric phosphate neutralization in the CAP half-site. Our results indicate a relative increase in DNA curvature of ∼23% when methylphosphonate substitutions are positioned to mimic sites of close contact by cationic amino acids observed in the CAP–DNA crystal structures (3,4). This observation demonstrates that asymmetric phosphate neutralization by CAP makes a detectable favorable contribution to DNA bending, but does not fully account for the large DNA deformation (∼90°) in the CAP–DNA complex (3,4).

Of particular note is the apparent importance of the local modified phosphate pattern for DNA deformation. The presence of three consecutive neutralized phosphates on the bottom DNA strand made dominant contributions, regardless of sequence (Fig. 4). When these methylphosphonates were placed to mimic sites of close approach by cationic amino acids, DNA curvature was enhanced, independent of the position of a pair of neutralizations on the other strand. When deliberately shifted one half-helical turn downstream, the same pattern of modifications induced a significant decrease in total DNA curvature. This dominant behavior of three consecutive neutralized phosphates was unexpected and is most evident in the bending behavior of duplexes s/m, u/m and m/m (Fig. 4). The dominance of the group of three consecutive neutralized phosphates is also evident in the shifted sequence context (Fig. 4, duplexes s/s, u/s and m/s), although in this series the pair of top strand neutralizations also exerts an influence. These results suggest that the loss of local interphosphate repulsions due to three consecutive phosphate neutralizations exerts a disproportionate effect on DNA collapse relative to a pair of neutralizations. The induced bending by an isolated set of three neutralized phosphates (Fig. 4, duplex u/m) demonstrates that neutralizations need not be positioned across a DNA groove to promote bending in a direction suggesting collapse of that groove. This result is not unexpected, as elimination of charge on either side of the groove reduces electrostatic repulsions as the groove is narrowed.

The DNA bending induced by phosphate neutralization in duplex m/m (Fig. 4) corresponds well to a DNA deformation in the CAP–DNA complex termed the ‘secondary kink’ (4). This secondary kink occurs in each half-site. In the left half-site (studied in our experiments) the secondary kink collapses the DNA minor groove by ∼19° over a region of 3 bp, centered between base pairs –1 and 1, as numbered in Figure 2B. Bending toward the minor groove at this position is consistent with the induced bend in this direction observed in neutralization pattern m/m (Fig. 4). Thus, we propose that asymmetric phosphate neutralization plays a role in providing perhaps one-third of the DNA bending observed at this secondary kink site, and perhaps ∼15% of the overall DNA bending in the complex with CAP.

It is important to compare our results with those obtained through other methods. Molecular modeling studies suggested a slightly larger intrinsic curvature of a similar unmodified CAP half-site sequence (38° versus 26°), but predicted a similar relative increase in curvature upon phosphate neutralization (18). Our observation that the direction of DNA curvature does not change upon modification is also in agreement with these authors (18). However, details of the prior modeling study deviate from our design. Certain phosphodiesters chosen for in silico neutralization (18) are likely to have been inappropriate due to the following considerations. The phosphodiester linkage between base pairs 2 and 3 was neutralized in the prior modeling study, but is actually contacted by the neutral amino acid Q170. The phosphodiester linkage between base pairs 3 and 4 was also neutralized, but forms hydrogen bonds with neutral residues T168, 169NH and 170NH. The phosphodiester linkage between base pairs –2′ and –3′ was not neutralized in the prior study, despite close contact by K26. The phosphodiester linkage between base pairs 9′ and 10′ was neutralized, but forms hydrogen bonds with neutral residues 179NH, S179 and T182. Finally, the phosphodiester linkage between base pairs 10′ and 11′ was neutralized in the modeling study, but forms hydrogen bonds with the neutral 139NH backbone. Despite these differences, an overall agreement with the prior modeling study exists in the sense that asymmetric phosphate neutralization enhances DNA bending in the predicted direction. Agreement also exists with the prediction from modeling that a 5 bp downstream shift of the neutralized linkages from sites predicted in the crystal structure results in an overall reduction in DNA curvature.

Few other studies are available for the evaluation of intrinsic curvature present in the free CAP half-site. Kahn and Crothers used Monte Carlo simulations coupled with cyclization kinetics to estimate ∼7.5° of curvature per half-site (26). It is unfortunate that, to our knowledge, a crystal structure of the uncomplexed DNA is not available for comparison.

We note that in the crystal structure of the CAP–DNA complex the primary DNA kink is between base pairs 6 and 7, producing a large bend toward the major groove. Smaller kinks between base pairs –1 and 1 exhibit roll angles of ∼20°, compressing the minor groove, with the DNA deformation distributed over 1–2 adjacent base pairs (4). Ebright and co-workers have recently reported the results of experiments that further support the importance of sequence-non-specific electrostatic interactions in dominating the shape of DNA in the CAP–DNA complex (27,28).

Our experimental approach is limited from the standpoint that individual DNA bends are not resolved; only a single virtual locus of curvature is detected by the phasing assay. It is possible that the presence of other intrinsically curved elements may contribute to the measured phasing dependence. Measured phasing amplitudes are also, to some extent, dependent on the position of a locus of curvature in the duplex inserts, relative to the position of the reference A5 tracts in the right arms (19). Diminished phasing amplitudes are contributed by elements of curvature in the distal portion of the studied sequence. Our assay also requires the assumption that the DNA helical repeat is not changed significantly by substitution with methylphosphonate linkages, a result supported by our previous studies (14).

Our results may also be compared with previous studies of the contribution of asymmetric phosphate neutralization to less extreme DNA bending induced by other proteins. Methylphosphonate substitution experiments with the PU.1 transcription factor binding site suggested that asymmetric phosphate neutralization between PU.1 and DNA was more than sufficient to account for all of the DNA bending observed in the crystal structure (29). Tomky et al. (16) also measured the contribution of asymmetric phosphate neutralization in bending of the AP-1 site by bZIP charge variants derived from GCN4 (30). It was observed that the amount of DNA bending induced by methylphosphonate substitution was of the same order as that induced by the binding of charge variants bearing additional basic amino acids. The fractional contribution to DNA bending by asymmetric phosphate neutralization may therefore be specific to each DNA–protein complex and may be of lesser importance in complexes with extensive hydrogen bonding networks and other favorable contact forces. Nonetheless, our present results highlight a detectable role for latent DNA bending forces revealed by asymmetric phosphate neutralization in the CAP–DNA complex.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Doerge of the Mayo Foundation Molecular Biology Core Facility for providing excellent oligonucleotide synthesis services. This work was supported by the Mayo Foundation and NIH grant GM54411 to L.J.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Passner J.M. and Steitz,T.A. (1997) The structure of a CAP-DNA complex having two cAMP molecules bound to each monomer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2843–2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu-Johnson H.N., Gartenberg,M.R. and Crothers,D.M. (1986) The DNA binding domain and bending angle of the E. coli CAP protein. Cell, 47, 995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz S.C., Shields,G.C. and Steitz,T.A. (1991) Crystal structure of a CAP-DNA complex: the DNA is bent by 90°. Science, 253, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkinson G., Wilson,C., Gunasekera,A., Ebright,Y.W., Ebright,R.E. and Berman,H.M. (1996) Structure of the CAP-DNA complex at 2.5 Å resolution: a complete picture of the protein-DNA interface. J. Mol. Biol., 260, 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn J.D. and Crothers,D.M. (1998) Measurement of the DNA bend angle induced by the catabolite activator protein using Monte Carlo simulation of cyclization kinetics. J. Mol. Biol., 276, 287–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracco L., Kotlarz,D., Kolb,A., Diekmann,S. and Buc,H. (1989) Synthetic curved DNA sequences can act as transcriptional activators in Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 8, 4289–4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gartenberg M.R. and Crothers,D.M. (1991) Synthetic DNA bending sequences increase the rate of in vitro transcription initiation at the Escherichia coli lac promoter. J. Mol. Biol., 219, 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiyar S.E., Gourse,R.L. and Ross,W. (1998) Upstream A-tracts increase bacterial promoter activity through interactions with the RNA polymerase α subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 14652–14657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maher L.J. (1998) Mechanisms of DNA bending. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2, 688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsodikov O.V., Saecker,R.M., Melcher,S.E., Levandoski,M.M., Frank,D.E., Capp,M.W. and Record,M.T.J. (1999) Wrapping of flanking non-operator DNA in lac repressor-operator complexes: implications for DNA looping. J. Mol. Biol., 294, 639–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holbrook J.A., Tsodikov,O.V., Saecker,R.M. and Record,M.T.J. (2001) Specific and non-specific interactions of integration host factor with DNA: thermodynamic evidence for disruption of multiple IHF surface salt-bridges coupled to DNA binding. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 379–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirzabekov A.D. and Rich,A. (1979) Asymmetric lateral distribution of unshielded phosphate groups in nucleosomal DNA and its role in DNA bending. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 76, 1118–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning G.S., Ebralidse,K.K., Mirzabekov,A.D. and Rich,A. (1989) An estimate of the extent of folding of nucleosomal DNA by laterally asymmetric neutralization of phosphate groups. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 6, 877–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss J.K. and Maher,L.J. (1994) DNA bending by asymmetric phosphate neutralization. Science, 266, 1829–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss-Soukup J.K., Rodrigues,P.D. and Maher,L.J. (1998) Effect of base composition on DNA bending by phosphate neutralization. Biophys. Chem., 72, 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomky L.A., Srauss-Soukup,J.K. and Maher,L.J. (1998) Effects of phosphate neutralization on the shape of the AP-1 transcription factor binding site in duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2298–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams L.D. and Maher,L.J. (2000) Electrostatic mechanisms of DNA deformation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 29, 497–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurlie R. and Zakrzewska,K. (1998) DNA curvature and phosphate neutralization: an important aspect of specific protein binding. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 16, 605–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardwidge P.R., Zimmerman,J.M. and Maher,L.J. (2000) Design and calibration of a semi-synthetic DNA phasing assay. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puglisi J.D. and Tinoco,I. (1989) Absorbance melting curves of RNA. Methods Enzymol., 180, 304–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogrefe R.I., Vaghefi,M.M., Reynolds,M.A., Young,K.M. and Arnold,L.J. (1993) Deprotection of methylphosphonate oligonucleotides using a novel one-pot procedure. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2031–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerppola T.K. (1994) DNA bending specificity among bZIP family proteins. In Conaway,R.C. and Conaway,J.W. (eds), Transcription: Mechanisms and Regulation. Raven Press, New York, NY, pp. 387–424.

- 23.Thompson J.F. and Landy,A. (1988) Empirical estimation of protein-induced DNA bending angles: applications to λ site-specific recombination complexes. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 9687–9705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zinkel S.S. and Crothers,D.M. (1990) Comparative gel electrophoresis measurement of the DNA bend angle induced by the catabolite activator protein. Biopolymers, 29, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross E.D., Den,R.B., Hardwidge,P.R. and Maher,L.J. (1999) Improved quantitation of DNA curvature using ligation ladders. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 4135–4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahn J.D. and Crothers,D.M. (1992) Protein-induced bending and DNA cyclization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 6343–6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen S., Vojtechovsky,J., Parkinson,G.N., Ebright,R.H. and Berman,H.M. (2001) Indirect readout of DNA sequence at the primary-kink site in the CAP-DNA complex: DNA binding specificity based on energetics of DNA kinking. J. Mol. Biol., 314, 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S., Gunasekera,A., Zhang,X., Kunkel,T.A., Ebright,R.H. and Berman,H.M. (2001) Indirect readout of DNA sequence at the primary-kink site in the CAP-DNA complex: alteration of DNA binding specificity through alteration of DNA kinking. J. Mol. Biol., 314, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss-Soukup J.K. and Maher,L.J. (1997) Role of asymmetric phosphate neutralization in DNA bending by PU.1. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 31570–31575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauss-Soukup J. and Maher,L.J. (1998) Electrostatic effects in DNA bending by GCN4 mutants. Biochemistry, 37, 1060–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]