Abstract

Lymphatic dysfunction is an underlying component of multiple metabolic diseases, including diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. We investigated the roles of KATP channels in lymphatic contractile dysfunction in response to acute metabolic stress induced by inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Ex vivo popliteal lymphatic vessels from mice were exposed to the electron transport chain inhibitors antimycin A and rotenone, or the oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor/protonophore, CCCP. Each inhibitor led to a significant reduction in the frequency of spontaneous lymphatic contractions and calculated pump flow, without a significant change in contraction amplitude. Contraction frequency was restored by the KATP channel inhibitor, glibenclamide. Lymphatic vessels from mice with global Kir6.1 deficiency or expressing a smooth muscle-specific dominant negative Kir6.1 channel were resistant to inhibition. Antimycin A inhibited the spontaneous action potentials generated in lymphatic muscle and this effect was reversed by glibenclamide, confirming the role of KATP channels. Antimycin A, but not rotenone or CCCP, increased dihydrorhodamine fluorescence in lymphatic muscle, indicating ROS production. Pretreatment with tiron or catalase prevented the effect of antimycin A on wild-type lymphatic vessels, consistent with its action being mediated by ROS. Our results support the conclusion that KATP channels in lymphatic muscle can be directly activated by reduced mitochondrial ATP production or ROS generation, consequent to acute metabolic stress, leading to contractile dysfunction through inhibition of the ionic pacemaker controlling spontaneous lymphatic contractions. We propose that a similar activation of KATP channels contributes to lymphatic dysfunction in metabolic disease.

Keywords: contractile dysfunction, lymph pump, metabolic syndrome, reactive oxygen species, action potential, mitochondrial electron transport chain

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Depiction of events by which metabolic stress associated with multiple diseases/conditions of metabolic dysfunction results in ROS production and reduced ATP/ADP following inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport complex, activating KATP channels in lymphatic muscle cells to inhibit the frequency of spontaneous action potentials generated and impair active lymph transport. For context, other pathways are shown that similarly modulate lymphatic muscle KATP channels, including Gain-of-Function (GoF) KATP channels expressed in patients with Cantu syndrome and the phosphorylation of KATP channels subsequent to PKA/PKG activation by nitric oxide/prostanoids.

Significance Statement.

Increasing evidence suggests that lymphatic contractile dysfunction contributes to the pathologies associated with multiple chronic diseases, including aging, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome, all of which are associated with metabolic stress. Although KATP channel activation plays a protective role in arterial smooth muscle under ischemic conditions, activation of KATP channels in lymphatic muscle decreases lymphatic muscle excitability and suppresses the generation of spontaneous contractions that aid in lymph propulsion. We investigated the possible contribution of KATP channels to the lymphatic contractile dysfunction associated with metabolic stress. Acute metabolic stress, induced by inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, led to increased KATP channel activity in lymphatic muscle, either through a reduction in the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio or increased production of ROS, resulting in impairment of the ionic pacemaker driving spontaneous contractions and active lymph transport. These actions were reversed by the KATP channel inhibitor, glibenclamide. Transgenic mice lacking functional KATP channels in lymphatic muscle were resistant to the effects of acute metabolic stress. Our findings point to a common role for KATP channels in the impaired lymphatic function observed in a number of metabolic diseases.

Introduction

The lymphatic system plays a major role in tissue fluid homeostasis through the removal of excess fluid and protein filtered from blood capillaries into the interstitium.1 The accumulation of excess interstitial fluid, most often in dependent extremities, leads to the chronic condition lymphedema. Lymphedema may result from genetic mutations in critical genes controlling lymphatic vessel or valve development,2 surgical disruption of lymphatic networks,3 altered permeability of lymphatic vessels,4–7 and/or impaired spontaneous contractions of the collecting lymphatic vessels that pump lymph centrally.8,9 The consequences of lymphatic dysfunction may also be more subtle. Recent studies suggest that altered lymphatic function contributes to subclinical edema that can compromise organ function under certain conditions, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction10 and diseases associated with the accumulation of tissue sodium.11,12

Subtle consequences of lymphatic dysfunction are also beginning to be appreciated in the context of metabolic diseases, including aging, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Lymphatic contractile dysfunction has been demonstrated in animal models of aging,13,14 obesity,6,15–17 TNFα overexpression,18,19 iNOS activation,20,21 metabolic syndrome,21,22 and other conditions associated with chronic inflammation.23–25 Lymphatic valve dysfunction, which impairs unidirectional lymph transport, is associated with animal models of obesity, with6 or without26 ApoE deficiency, and in models of TNFα hyperactivity.18,27 Lymphatic collecting vessel hyperpermeability, which counteracts the central return of lymph, has been demonstrated in animal models of obesity5,6,26,28 and in a model of type 2 diabetes.29 However, the mechanisms by which lymphatic dysfunction contributes to or results from the primary disease are not clear.

A common feature of these disease models is chronic metabolic stress. The primary source of intracellular ATP is the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) and one mechanism of coupling the electrical activity of cells to their metabolic state is through the activity of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels. KATP channels are voltage-independent, K+-selective channels that are activated by intracellular ADP and inhibited by intracellular ATP.30,31 By sensing the ATP/ADP ratio, they act as “metabolic sensors of the cell.”32 Mammalian KATP channels are hetero-octameric complexes comprised of four inward-rectifying K+ channel (Kir6) pore-forming subunits and four regulatory sulphonylurea receptor (SUR) subunits. Two pairs of genes (ABCC8, KCNJ11, and ABCC9, KCNJ8) on chromosome 11, each encode one pair of subunits—SUR1, Kir6.2, and SUR2, Kir6.1, respectively.30 The expression of different combinations of Kir6 and SUR subunits results in distinct KATP channel properties and functional roles in different cell types.30,32 In the vasculature, KATP channels normally have low activity in arterial smooth muscle cells but become activated under ischemic conditions,30 leading to arterial smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization and dilatation, which in turn increase blood flow and oxygen supply to the ischemic tissue.32 The composition of KATP channels expressed in lymphatic muscle is similar to that in arterial smooth muscle (Kir6.1 and SUR2B). Although KATP-dependent vasodilation plays a protective role in arteries,30,33,34 similar depression of lymphatic muscle excitability by KATP channel activation could promote edema formation and sustain tissue inflammation as a consequence of impaired active lymph transport.8,35

In the present study, we hypothesized that acute mitochondrial inhibition would suppress ATP production and result in KATP channel activation, reducing lymphatic muscle excitability and impairing the active lymph pump. Furthermore, given that metabolic stress can increase ROS production in mitochondria,36 we also sought to evaluate the possible contribution of ROS. Our findings suggest that metabolic stress contributes to the contractile component of lymphatic dysfunction observed in metabolic diseases through ROS-dependent and -independent activation of KATP channels in lymphatic muscle.

Methods

Ethical Approval

All protocols and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri (protocol #9797) and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, 2011).

Mice

Mice were housed and bred under pathogen-free conditions in a controlled environment (22 ± 2°C, 12/12-hr light/dark cycle) of the animal facility of the University of Missouri School of Medicine. C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice were purchased at 5 weeks of age from Jackson Laboratory (C57Bl/6 J, strain #000 664, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Kir6.1−/− mice were a gift from Susumu Seino (Kobe University). Dominant negative Kir6.1 (eGFP-Kir6.1[AAA]) mice were described previously.37 Mice carrying eGFP-Kir6.1[AAA] were crossed to Myh11-CreERT2 mice (JAX No. 01 979) to generate Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1-AAA mice with an inducible dominant negative Kir6.1 transgene expressed specifically in smooth muscle. The offspring were injected with tamoxifen (10 mg mL−1 in safflower oil) for consecutive 5 days and allowed to recover for 14 days; we confirmed the absence of GFP signal in the smooth muscle cell layer before testing. For ROS imaging, Myh11-CreERT2; tdTomato mice were used. Genotypes were confirmed by PCR with Taq DNA Polymerase Premix (Intact Genomics Catalog #3249). Mice were studied at 6-8 weeks of age from either sex, depending upon availability; in the case of Myh11-CreERT2 mice, only males were used, as the transgene is located on the Y-chromosome; for other protocols mice of both sexes were used. For experiments, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection using a mixture of ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg kg−1 body weight) and euthanized by intracardiac injection of KCl.

Vessel Isolation, Pressure Myography, and Data Acquisition

We have previously documented the reliability and reproducibility of contraction parameter tests for mouse popliteal lymphatic vessels studied ex vivo.4,38,39 For the isolation of mouse popliteal lymphatic vessels, a proximal-to-distal incision was made in the skin of the dorso-lateral thigh to expose the superficial saphenous vein. Afferent popliteal lymphatic vessels on either side of this vein were removed and transferred to a Sylgard dissection dish with Krebs buffer containing albumin. After pinning and cleaning, a vessel was cannulated using two glass micropipettes (40-50 µm, outer diameter), pressurized to 3 cmH2O and further cleaned of any remaining tissue in order to track diameter accurately. The vessel was shortened to a length that contained only one valve. Polyethylene tubing (PE-190) attached to the back of each micropipette holder was connected to a 2-channel microfluidic device (Elveflow OB1 MK3, Paris) for computer control of pressure on the stage of an inverted microscope. Input and output pressures were transiently set to 10 cmH2O immediately after set up and the vessel was stretched axially to approximate the in vivo length, which minimized longitudinal bowing and associated diameter-tracking artifacts during subsequent protocols.40 With input and output pressure held at 3 cmH2O, spontaneous contractions typically began within 15-30 min of warm-up and each vessel was allowed to stabilize at 37°C for 30-60 min before beginning an experimental protocol. A suffusion line connected to a peristaltic pump exchanged the chamber contents with Krebs buffer at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. A custom-written LabVIEW (National Instruments; Austin, TX, USA) algorithm41 measured the inner diameter of the vessel from video images obtained at 30 fps using a Basler A641fm firewire camera.

Assessment of Lymphatic Contractile Function

Spontaneous contractions were recorded with equal input and output pressures (3 cmH2O) to prevent a pressure gradient for forward flow through the vessel during the experiment. The effects of mitochondrial ETC inhibitors or oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors on WT, Kir6.1−/− and Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels were determined by adding the compounds to the perfusate. At the end of the perfusion period (20-60 min), a small, predetermined volume of GLIB (1 µm) was added to the 3 mL bath, followed by thorough mixing while the bath was stopped. At the end of every experiment, all vessels were perfused with Ca2+-free Krebs buffer containing 3 m m EGTA for 30 min, and passive diameters were recorded at 3 cmH2O pressure (DMAX). After an experiment, custom-written analysis programs were used to detect peak end-diastolic diameter (EDD), end-systolic diameter (ESD), contraction amplitude (AMP), and contraction frequency (FREQ) on a contraction-by-contraction basis at rest before addition of the drug (FREQREST) and following administration of drug.42 When FREQ was zero, no value of AMP was recorded. Fractional Pump Flow (FPF) is the best estimate of net flow and is a calculated variable due to the lack of flow meters with sensitivities in nL/min range. These data were used to calculate several commonly reported parameters that characterize lymphatic vessel contractile function. Each parameter was averaged over a 5 min period and used to calculate the following indices of lymphatic contractile function:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

where FREQavg represents the average frequency (in contractions per minute; cpm) during the baseline period before the addition of a drug to the bath and DMAX represents the maximum passive diameter (obtained after incubation with calcium-free Krebs solution) at a given level of intraluminal pressure.

Vm Measurement

Popliteal lymphatic vessels from WT mice were isolated and pressurized as described above. Wortmannin (1 µm; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was applied to the perfusion bath for 30 min to inhibit myosin light chain kinase until contractions were sufficiently blunted to maintain impalements into lymphatic smooth muscle using intracellular microelectrodes (200-320 MΩ) filled with 1 M KCl solution. The preservation of small contractions (≤5 µm amplitude) allowed us to monitor the viability of the preparation. Membrane potential was sampled at 1-5 KHz using an AxoClamp2A amplifier, digitized through an A-D interface (USB-6216, National Instruments) and recorded using a custom LabVIEW program. Once impaled, Vm was allowed to stabilize before action potentials and multiple contraction cycles were recorded for analysis. Once recordings were completed, the electrode was retracted and the recording was corrected for any offset potential.

Analysis of ROS Production in Lymphatic Muscle

Popliteal lymphatic vessels from tamoxifen-treated Myh11-CreERT2; tdTomato or WT mice were dissected and cannulated. To evaluate ROS production, the pressurized vessels were loaded with dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR; Fisher Scientific), a membrane permeable dye that coverts to cationic rhodamine 123 upon oxidation and then localizes to mitochondria.43 DHR was dissolved in DMSO and diluted to 10 µm in Krebs buffer, perfused and preincubated for 10 min in a bath and remained in the superfusion solution throughout the experiment. All vessels were incubated at 37°C in a light-protected environment. Nifedipine (1 µm) was applied to the bath to completely inhibit any spontaneous contractions that otherwise would have prevented maintaining focus on the smooth muscle layer. Fluorescence images were acquired for 100 ms at 1 min intervals for 15 min with 10× (Olympus UPlanApo N.A. = 0.40) or 20× (Olympus UPlanSApo N.A. = 0.75) objectives coupled to an EMCCD camera (Photometrics Cascade II) on an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope. Illumination was provided by an Andor/Yokogawa CSU-X Confocal Spinning Disk system with excitation at 472/30 nm and emission at 525/35 nm. Fluorescence intensity was quantified with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) in a region of interest located in the middle of a vessel following subtraction of background fluorescence. As a positive control for generating ROS, the mitochondria complex III inhibitor, antimycin A (1 µm) was added to the superfusion solution.44 To verify the sensitivity of DHR to endogenous ROS production, experiments were repeated following 10 min of preincubation with tiron (1 m m) in combination with polyethylene glycol (PEG)-catalase 250 U mL−1. The respective reagents were present throughout the rest of the experiment. Values for DHR fluorescence are expressed in arbitrary units for the change from baseline within a ROI (△ = fluorescence at x min − fluorescence at 0 min, where x represents 1 min intervals during chemical exposure).45

Solutions and Chemicals

Krebs buffer contained (in m m) 146.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2 CaCl2·2H2O, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4·H2O, 3 NaHCO3, 1.5 NaHEPES, and 5 D-glucose (pH = 7.4). Krebs-BSA buffer was prepared with the addition of 0.5% bovine serum albumin. During cannulation, Krebs-BSA buffer was present both luminally and abluminally, but during the experiment the bath solution was replaced with Krebs solution without albumin. Ca2+ free Krebs buffer was used at the end of experiment to obtain the maximum passive diameter. All chemicals and drugs (rotenone, antimycin A, CCCP, tiron, PEG-catalase) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), with exception of BSA (United States Biochemicals; Cleveland, OH, USA), MgSO4, Na-HEPES (ThermoFisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA). PEG-catalase was dissolved in distilled water. Antimycin A, CCCP, rotenone and GLIB were dissolved in DMSO and the total amount of DMSO was set below 0.4%, which was determined in separate protocols to be the vasoactive threshold concentration.

Statistical Procedures

The number n refers to the total number of vessels included per group as stated in the figure legends; N is number of animals. Values are means ± SD. Statistical analysis was undertaken only for studies where each group size ≥5. Randomization was not a feature of study design. Because baseline values of spontaneous contraction frequency are highly variable among lymphatic vessels,46 we expressed the data as normalized values of FREQ, AMP, or FPF, with each value normalized to the average of the respective control values. Differences between FREQ, AMP, or FPF in the presence or absence of treatment were assessed using ANOVA or paired Student’s t-tests as stated in the figure legends. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism9 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA), with significance for all tests set at P < 0.05.

Results

Mitochondrial ETC Disruption Impairs Lymphatic Pacemaking

When pressurized and heated to physiological intraluminal pressure and temperature, WT popliteal lymphatics developed spontaneous twitch contractions. At 37°C and 3 cmH2O intraluminal pressure, the typical lymphatic contraction pattern shown at the start of the recording in Figure 1A was stable for hours, although in some vessels occasional patterns of burst contractions developed over time. In this example, the contraction amplitude was ∼40 µm (41% of maximal passive diameter) and frequency was 11 contractions per minute (cpm) until ∼1 min after the application of the ETC complex III inhibitor antimycin A (30 n m). This concentration was slightly higher than the IC50 (12.2 n m) used to inhibit mitochondrial oxygen consumption.47 In the presence of antimycin A, contractions nearly ceased during the last 5 min of antimycin A treatment [control FREQ = 11 cpm vs 1 cpm (12.2% of control)]. Contraction amplitude was largely unaffected even after 20 min exposure to antimycin A. The subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm), at a concentration that we found previously could reverse impaired contractions in vessels from mice expressing overactive KATP channels,8,35 partially restored contraction frequency. Both 3 and 10 µm GLIB produced more complete recovery of frequency (not shown), but here we used 1 µm, a concentration that minimizes off-target effects associated with higher concentrations of this inhibitor.48

Figure 1.

Antimycin A reduces lymphatic muscle contraction frequency and the inhibition is reversed by GLIB. Responses of mouse popliteal lymphatics, pressurized to 3 cmH2O, exposed to the mitochondrial ETC complex III inhibitor, antimycin A (30 n m). Example recordings of vessels from (A) wild-type (WT), (B) Kir6.1−/− and (C) Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mice. During the last 2 min of the recording period, the frequency of only the WT vessel was reduced by antimycin A and that reduction was largely rescued by GLIB (1 µm). (D) Summary of changes in normalized frequency for the different treatments and genotypes. Gray bars represent WT vessels (N = 7; n = 10), red bars are Kir6.1−/− vessels (N = 6; n = 5) and green bars are Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels (N = 4; n = 6). All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 between WT vessels before and after treatment of antimycin A and GLIB using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Under baseline conditions, popliteal lymphatics from Kir6.1−/− mice developed similar patterns of spontaneous contractions as WT mice (Figure 1B). The lower basal contraction frequency in this particular vessel reflects natural vessel-to-vessel variation and was not a consistent feature of Kir6.1−/− vessels,35,48 as KATP channels make little contribution to the basal excitability of lymphatic muscle cells (LMCs) of mice under normal (normoxic) conditions. In contrast to the WT vessel, the Kir6.1−/-vessel was almost completely resistant to the effects of antimycin A [control FREQ = 6.8 cpm vs 5.7 cpm during the last 5 min of antimycin A] and subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µM) produced little further effect (FREQ = 6.2 cpm). Although we previously demonstrated that functional KATP channels are expressed in smooth muscle but not endothelium of mouse popliteal vessels, here we expressed a dominant negative construct of Kir6.1[AAA]37 specifically in the muscle layer to confirm that LMC KATP channels were responsible for protection from the effects of antimycin A. The Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] contraction pattern was similar to the WT vessel prior to administration of antimycin A, (Figure 1C). As with the Kir6.1−/− vessel, the Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessel was resistant to the effects of antimycin A (control FREQ = 10.3 cpm vs 10.3 cpm after antimycin A) and the subsequent application of GLIB (1 µm) had little additional effect (FREQ = 9.9 cpm). These observations suggest that treatment with antimycin A results in the activation of KATP channels in the muscle layer of mouse popliteal lymphatic vessels to impair pump function.

Summary data for the effects of antimycin A ± GLIB on lymphatic vessels from the three genotypes are presented in Figure 1D. The frequency of WT vessels was significantly reduced by antimycin A and that depression of frequency was largely reversed by GLIB (1 µm), as predicted if the mechanism involved activation of KATP channels. Antimycin A produced a small but nonsignificant increase in normalized AMP in WT vessels that also was restored to control levels by GLIB (Suppl. Figure 1A). The reduction in FREQ (Figure 1D) was more than sufficient to offset the increase in normalized AMP and produce a significant reduction in calculated fractional pump flow (FPF) (Suppl. Figure 1B), which is an estimate of active lymph transport. The antimycin A-induced reduction in normalized FPF of WT vessels was significantly rescued by GLIB (Suppl. Figure 1B). Antimycin A had no significant effects on the normalized amplitude or FPF of Kir6.1−/− vessels or Myh11CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels (Suppl. Figure 1A, B).

Next, we explored the actions of a different metabolic stressor, rotenone, which inhibits ETC complex I.49 Rotenone (100 n m) caused a progressive decline in the frequency of spontaneous lymphatic contractions, from a control FREQ = 9.9 cpm to 2.2 cpm (22.2% of control) during the last 5 min of rotenone treatment, which was reversed by GLIB (1 µm) (Figure 2A). Note that this vessel had a bursting contraction pattern, whereby 3-8 contractions occurred in rapid succession followed by a short pause prior to the next contraction burst. In contrast, a popliteal lymphatic from a Kir6.1−/− mouse was largely resistant to the effects of rotenone, with control FREQ = 8.1 cpm vs 7.6 cpm during the last 5 min of rotenone treatment; subsequent GLIB (1 µm) application had little additional effect (Figure 2B). A popliteal lymphatic from a Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mouse (also with a bursting contraction pattern) was also resistant to rotenone (control FREQ = 14.1 cpm vs 13.1 cpm during the last 5 min of rotenone) (Figure 2C). Summary data for the effects of rotenone (100 n m) on the 3 genotypes are plotted in Figure 2D. The only significant effects of rotenone were on WT vessels, in which it lowered frequency to ∼25% of control, with partial rescue by GLIB (1 µm). Rotenone had no significant effects on normalized AMP for any of the three genotypes (Suppl. Figure 1C). Rotenone significantly reduced the normalized FPF of WT vessels, but not the normalized FPF of Kir6.1−/− vessels or Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels (Suppl. Figure 1D).

Figure 2.

Rotenone reduces lymphatic muscle contraction frequency and the inhibition is reversed by GLIB. Representative examples of the effects of the mitochondrial ETC complex I inhibitor, rotenone (100 n m) on spontaneous contractions of mouse popliteal lymphatic vessels from (A) WT, (B) Kir6.1−/−, and (C) Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mice. The frequency of only the WT vessel was reduced by rotenone and this effect was largely rescued by GLIB (1 µm). (D) The summary graphs showing normalized frequency for the various treatments and genotypes. Gray bars represent WT vessels (N = 6; n = 8), red bars are Kir6.1−/− vessels (N = 3; n = 6) and green bars are Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels (N = 3; n = 6). All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 between WT vessels before and after treatment of rotenone and GLIB using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Next, we tested the effects of the protonophore CCCP (1 µm), which reduces ATP production by uncoupling mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.50 The application of CCCP (1 µm) to a WT popliteal lymphatic lowered frequency from 9 cpm in the control period to 2 cpm (22.2% of control) during the last 5 min of CCCP (Figure 3A), and the effect was reversed by GLIB (1 µm). In contrast, popliteal vessels from a Kir6.1−/− mouse (Figure 3B) and an Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mouse (Figure 3C) were resistant to the effects of CCCP. The data for CCCP on normalized frequency are summarized for the three genotypes in Figure 3D. The only significant effects of CCCP were on WT vessels, which on average lowered frequency to 22% of control and showed partial rescue by GLIB (1 µm). There were no significant changes in normalized amplitude in response to CCCP for any of the three genotypes, suggesting there was still sufficient ATP for normal actomyosin crossbridge cycling (Suppl. Figure 1E). As a consequence of the reduction in frequency, CCCP caused a significant reduction in the normalized FPF of WT vessels (but not Kir6.1−/− vessels or Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels) (Suppl. Figure 1F).

Figure 3.

CCCP reduces lymphatic muscle contraction frequency and the inhibition is reversed by GLIB. Representative examples of the effects of the oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor, CCCP (1 µm), on mouse popliteal lymphatics from (A) WT, (B) Kir6.1−/− and (C) Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mice. The frequency of only the WT vessel was reduced by CCCP; it was largely rescued by GLIB (1 µm). (D) Summary graphs showing normalized frequency for the various treatments and genotypes. Gray bars represent WT vessels (N = 6; n = 10), red bars are Kir6.1−/− vessels (N = 3; n = 6) and green bars are Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] vessels (N = 3; n = 6). All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 between WT vessels before and after treatment of CCCP and GLIB one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Complex III Inhibition Suppresses Lymphatic Action Potentials

Given these findings, we then tested the effects of antimycin A on the membrane potential of popliteal lymphatics from WT mice. Previously, we showed that KATP channel activation leads to inhibition of the ionic pacemaker underlying spontaneous lymphatic contractions, but that overt hyperpolarization is not required to inhibit action potential generation.35,51 Such was the case for antimycin A. Approximately 100 sec after antimycin A application, spontaneous action potentials ceased, even though the resting Vm depolarized slightly (Figure 4A), contractions stopped and the vessel dilated. The inhibition of action potential firing despite slight depolarization suggests that the threshold for action potential firing was reset52 during this period (Figure 4B, insert b). The effect of this concentration of antimycin A was similar to that produced by 100-300 n m pinacidil in previous studies.48,51 Summary Vm data for nine LMCs from nine different vessels showed that spontaneous action potential generation was abolished by antimycin A in most cells without significant hyperpolarization (with one exception) (Figure 4C). GLIB (1 µm) application restored AP generation in all cells (Figure 4D). Although we did not perform Vm measurements during rotenone or CCCP application, there is a 1:1 correspondence of twitch contractions with APs,35,53,54 and the contraction recordings for rotenone and CCCP suggest that both drugs also inhibited AP firing.

Figure 4.

Antimycin A inhibits action potentials in LMCs and GLIB counteracts its effects. Raw traces showing that antimycin A (30 n m) inhibits the frequency of spontaneous lymphatic contractions (A) and action potentials (APs). Membrane potential (Vm) was recorded using an intracellular electrode in a LMC of a WT mouse popliteal lymphatic vessel pressurized at 3 cmH2O. The recording was made in the presence of 1 µm wortmannin to minimize vessel wall movement. (B) Magnification of APs in panel A prior to drug (a), in the presence of antimycin A (b), and antimycin A and GLIB (1 µm), which restored AP generation (c). (C) Summary of resting Vm values in lymphatic muscle cells before and after treatment of antimycin A and/or GLIB (N = 8; n = 9). (D) Summary of changes in AP (and concomitant contraction) frequency before and after treatment of antimycin A and GLIB. All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

ROS Contribution to Metabolic Disruption of Lymphatic Pacemaking

Next, we measured production of ROS in the muscle layer using DHR. Popliteal lymphatics expressing the td-Tomato reporter in LMCs under the control of Myh11CreERT2 enabled us to focus on the fluorescence signal in the LMC layer per se, while nifedipine (1 µm) was used to completely block any wall movement associated with spontaneous contractions. The DHR signal in the focal plane of the LMCs is shown in the first 2 columns of Figure 5 (at 0 and 15 min), with the td-Tomato signal in the third column and the merged signal in the fourth column. A control vessel is shown in row A, a vessel treated with antimycin A (30 n m) in row B, a vessel treated with rotenone (100 n m) in row C, a vessel treated with CCCP (1 µm) in row D, a vessel treated with antimycin A (1 µm) in row E, and a vessel treated with antimycin A (1 µm) after pretreatment with tiron (1 m m) and Catalase (250 U/mL) in row F. The time courses of the DHR signals under these various conditions are plotted in Figure 5G. Both 30 n m and 1 µm antimycin A produced significant increases in DHR signal, and the latter was prevented by tiron and catalase pretreatment. Neither rotenone nor CCCP treatment led to a significant increase in ROS production.

Figure 5.

Antimycin A, but not rotenone or CCCP enhance ROS generation in WT lymphatic vessels. Nifedipine 1 µm was used to block lymphatic contractions of pressurized (3 cmH2O) popliteal lymphatic vessels from Myh11-CreERT2; tdTomato mice so that the microscope objective could be focused on the tdTomato signal in the LMC layer. Representative images from untreated lymphatic vessels (A; N = 9; n = 9) and lymphatic vessels treated with 30 n m antimycin A (B; N = 9; n = 10), 100 n m rotenone (C; N = 6; n = 10), 1 µm CCCP (D; N = 7; n = 10), 1 µm antimycin A (E; N = 9; n = 10), and 1 µm antimycin A + 1 m m tiron and 250 U/mL catalase (F; N = 9; n = 9) showing initial DHR fluorescence (0 min; First column), 15 min of DHR accumulation (Second column), the td-tomato signal (Third column) and the merged signal (Fourth column) from columns 2 and 3. Scale bars are 50 µm. (G) Summary data for changes for in DHR123 fluorescence over a 15 min measurement period. Values are means ± SD tested with a one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post-hoc test. *P < 0.05 antimycin A (30 n m or 1 µm) vs control. #P < 0.05 antimycin A (1 µm) + tiron + catalase vs antimycin A (1 µm).

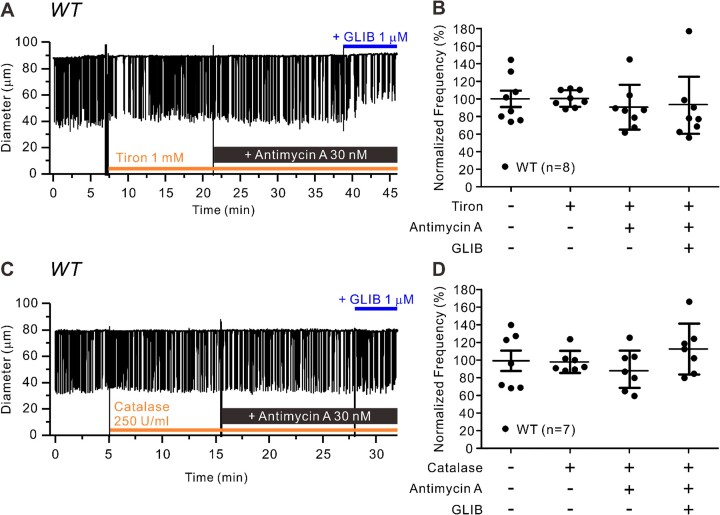

Having established that antimycin A induces ROS production in LMCs, we then asked whether pretreatment with ROS scavengers could prevent the effects of antimycin A on FREQ and FPF of WT lymphatic vessels. The example in Figure 6A shows a vessel treated with tiron (1 m m), at a concentration used to effectively scavenge O2− in other studies.55,56 Tiron was applied to the bath for 10 minutes prior to the addition of antimycin A. In this case, a transient slowing of FREQ occurred almost immediately after the addition of tiron, but FREQ subsequently returned to normal (within 5 min). The application of antimycin A did not produce any substantial changes in contraction FREQ, nor did subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm), which in this case reduced contraction amplitude by ∼40% (Figure 6A). The effect of GLIB on amplitude in this vessel was not a consistent one, as shown in the summary data in Suppl. Figure 2A. Tiron pretreatment effectively blocked the inhibitory effect of antimycin A on normalized FREQ (Figure 6B), but again without significant effects on either normalized AMP or FPF (Suppl. Figure 2A, B). A similar protocol was used to test the effects of the H2O2 scavenger catalase (250 U/mL),55,56 which also completely blocked the inhibitory effects of antimycin A on normalized FREQ (Figure 6C). Summary data for the effects of catalase pretreatment on effects of antimycin A confirm that there were no significant effects on either normalized FREQ (Figure 6D) or on AMP or FPF (Suppl. Figure 3A, B). These effects of tiron and catalase are consistent with the conclusion that antimycin A is producing ROS, which activates KATP channels to inhibit pacemaking frequency.

Figure 6.

Scavenging ROS prevents the effects of antimycin A on lymphatic contraction. Raw traces of lymphatic contractions in WT vessels in response to antimycin A (30 n m) after pretreatment with (A) tiron (1 m m) or (B) catalase (250 U/mL) for 10 min and after subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm). Summary of normalized frequency changes to antimycin A with and without C) tiron (N = 6; n = 8) and (D) catalase (N = 4; n = 7). All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 before and after treatment of rotenone and GLIB using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

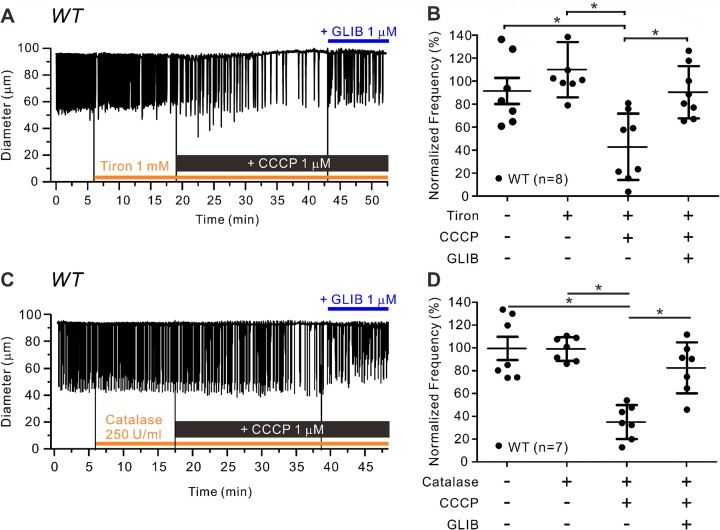

Similar protocols were conducted to test tiron and catalase pretreatment on the effects of rotenone. As shown in the example recording in Figure 7A, pretreatment with tiron failed to prevent the subsequent reduction in contraction FREQ in response to rotenone [control FREQ = 12.5 cpm vs 3.6 cpm (26.9% of control) during last 5 min of rotenone], as confirmed by the summary data in Figure 7B. Rotenone did not significantly inhibit normalized AMP (AMP actually increased) in the presence or absence of tiron (Suppl. Figure 2C) and tiron pretreatment failed to block rotenone-induced inhibition of normalized FPF (Suppl. Figure 2D). Likewise, pretreatment with catalase did not prevent the subsequent rotenone-induced reduction in contraction frequency [Figure 7C; control FREQ = 10.6 cpm vs 2.8 cpm (28.2% of control) during last 5 min of rotenone], as confirmed by the summary data in Figure 7D. Catalase pretreatment did not significantly alter the effect of rotenone on normalized contraction AMP (Suppl. Figure 3C) and failed to block the rotenone-induced inhibition of normalized FPF (Suppl. Figure 3D). These results confirm that rotenone does not inhibit lymphatic pumping through the production of ROS.

Figure 7.

ROS scavengers do not prevent effects of rotenone on lymphatic contraction. Raw traces showing inhibition of lymphatic contraction frequency in WT vessels in response to rotenone (100 n m) after pretreatment with m (A) tiron (1 m m) or (B) catalase (250 U/mL) for 10 min and after subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm). Summary of normalized frequency changes to rotenone with and without C) tiron (N = 5; n = 8) or (D) catalase pretreatment (N = 7; n = 10). All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 before and after treatment of rotenone and GLIB using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Tiron pretreatment also failed to block the inhibitory effect of CCCP on contraction FREQ (Figure 8A; control FREQ = 10.5 cpm vs 4.6 cpm (42.4% of control) during the last 5 min of CCCP], but the inhibition was rescued by subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm). The summary data in Figure 8B confirm that significant CCCP-induced inhibition of contraction FREQ persisted in the presence of tiron. Tiron did not alter the effect of CCCP on AMP and failed to prevent the CCCP-induced reduction in normalized FPF (Suppl. Figure 2E, F). Catalase likewise failed to block the inhibitory effect of CCCP on normalized FREQ [Figure 8C; control FREQ = 10.2 cpm vs 4.3 cpm (39.3% of control) during last 2 min of CCCP], but the inhibition was rescued by subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm). The summary data in Figure 8D indicate that the reduction in normalized FREQ was significant. Catalase pretreatment did not alter the effect of CCCP on contraction AMP (Suppl. Figure 3E) but failed to prevent the CCCP-induced reduction in normalized FPF (Suppl. Figure 3F). These results suggest that CCCP does not inhibit lymphatic contraction through the production of ROS.

Figure 8.

ROS scavengers do not prevent effects of CCCP inhibition on lymphatic contraction. Representative traces of lymphatic contractions in WT vessels in response to CCCP 1 µm pretreated with (A) tiron (1 m m) or (B) catalase (250 U/mL) for 10 min and after subsequent addition of GLIB (1 µm). Summary of normalized frequency changes to CCCP with and without C) tiron (N = 5; n = 8) or D) catalase (N = 4; n = 7) pretreatment. All data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05 before and after treatment of CCCP and GLIB using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

Discussion

Our study is the first to evaluate the effects of metabolic inhibitors on KATP channels in lymphatic muscle. Three different inhibitors of mitochrondrial ATP production, two that inhibited the ETC and one that inhibited oxidative phosphorylation, each retarded the ionic pacemaker that drives spontaneous lymphatic contractions and active lymph pumping. The inhibitor of ETC complex III, antimycin A, acted through the production of ROS, as its effects on contraction frequency were prevented by pretreatment with either of two ROS scavengers, tiron and catalase. The ETC complex I inhibitor (rotenone) and the oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor CCCP did not increase ROS production and their effects were not blocked by ROS scavengers, consistent with the conclusion that KATP channel activation in these cases was mediated by a decrease in the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio.57 Three important findings from our study were that: (1) the effects of all three metabolic inhibitors on contraction frequency and pumping could be reversed by a relatively low and selective concentration of the KATP channel inhibitor GLIB; (2) ETC inhibition caused a selective reduction in contraction frequency without a concomitant inhibition of amplitude; and (3) mice lacking functional KATP channels in lymphatic muscle (Kir6.1−/− or Myh11-CreERT2; Kir6.1[AAA] mice) were completely resistant to the effects of the metabolic inhibitors. Further confirmation that the inhibitors worked through activation of KATP channels in lymphatic muscle came from direct measurements of Vm in LMCs in which antimycin A stopped the generation of spontaneous action potentials, and that inhibition was reversed by GLIB.

The effects of ETC inhibition tested in our study were intended to simulate the chronic metabolic stress associated with metabolic disease. Obesity and insulin resistance are linked to decreased efficiency of ATP synthesis and an increase in mitochondrial ROS production.36 This imbalance of energy production vs utilization is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome. While direct measures of ROS production in lymphatic vessels in animal models of metabolic disease in response to metabolic disorders are lacking, metabolic dysfunction induced by high fat or Western-style diets (ie, high fat and processed carbohydrate) are known to increase ROS production in skeletal muscle and cerebral artery smooth muscle.45,58 A key finding of our study is that while effects of ETC complex I and oxidative phosphorylation inhibition are likely reliant upon reduced ATP/ADP, the effects of complex III inhibition appear to be mediated through ROS production. Scavenging superoxide with tiron or H2O2 with catalase prevented changes in KATP-dependent lymphatic pacemaker modulation in response to complex III inhibition. It is somewhat surprising that the effects of complex III inhibition could be fully prevented by ROS scavenging as antimycin A also would be expected to have an effect on the ATP/ADP ratio. Nonetheless, modulation of mitochondrial energetics had profound effects on lymphatic contractile function through multiple mechanisms of KATP activaton.

ATP is a negative regulator of the KATP channel, with channel activity increasing as ATP levels fall.30 But how might ROS activate the KATP channel? At least two other studies have demonstrated ROS-mediated activation of KATP channels.59,60 Although the exact mechanism is unknown and may vary with the ROS species and/or KATP subunit composition, one study found that H2O2 lowers the sensitivity of the channel to ATP, implying that ROS effects are mediated by the SUR channel subunit.60 ROS species can also activate protein kinases61 and ROS-mediated PKA activation could be another potential mechanism for the increased activity of LMC KATP channels.25,62 However, investigating these mechanisms in lymphatic vessels was beyond the scope of this study.

We have assumed that the KATP channels controlling lymphatic muscle pacemaking are located on the LMC sarcolemma, based in part on the observation that antimycin A-induced inhibition of ETC inhibited AP generation in LMCs (Figure 4). However, evidence suggests that KATP channels are also expressed on the mitochondrial inner membrane (mitoKATP), where they regulate ATP production and alter mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by changing the mitochondrial membrane potential.57 The molecular identity of mitoKATP has been recently described, MitoK (Ccdc51) and MitoSur (Abcb8),63 but assessment of its role in most intact cell preparations is still limited to the use of pharmacological tools such as the inhibitor 5-hydroxydecanoate and the activator diazoxide. These compounds are often promoted as selective regulators of mitoKATP over sarcolemmal KATP (“sarcKATP”) channels, but their selectivity is controversial64–67 and both compounds, or their metabolites, also act on other mitochondrial targets.67–69 Given the limitations of these modulators and the intact vessel techniques employed in the present study, we would be unable to definitively discriminate between mitoKATP and sarcKATP in the regulation of lymphatic vessel pacemaking. However, this remains an area for further investigation.

A major implication of our results is that acute metabolic stress leads to the activation of KATP channels in lymphatic muscle, retarding the ionic pacemaker and inhibiting the spontaneous contractions that are critical for active lymph pumping. Although KATP channel activity makes little contribution to the pacemaking frequency of murine lymphatic vessels under normoxic conditions,35,48 activation of this channel acts as a powerful brake on pacemaking62 by inhibiting the repetitive cycle of diastolic depolarization and AP firing involving anoctamin1 and L-type Ca2+ channels [for details see recent reviews62,70]. Given these findings, we propose that KATP channel activation is a possible explanation for the impaired lymphatic contractile function and/or lymph transport observed in a number of animal models of metabolic disease. It is interesting that many of these studies, like ours, show an impairment—often a selective impairment—in lymphatic contraction frequency. Several examples are notable. (1) In mice and rats of advanced age, selective reductions in basal lymphatic contraction frequency71 and near-elimination of flow-mediated contraction frequency regulation13 were noted in comparison to vessels from younger animals. (2) In mice fed a high fat diet (HFD) to induce obesity, a reduced packet frequency of dye transport was observed in lymphatic vessels of the hindlimb.15,16 (3) In ApoE−/− mice on a HFD, contraction frequency and FPF of ex vivo popliteal lymphatics were impaired at low pressures.6 (4) In a mouse model of TNFα overexpression, popliteal lymphatic vessels showed a reduced spontaneous contraction frequency over a wide range of intraluminal pressure.18 (5) In a high fructose rat model of metabolic syndrome, contraction frequency and calculated pump flow were reduced 40-50%, depending on the intraluminal pressure level, with no significant change in contraction amplitude, stroke volume, or ejection fraction.21 (6) In a rat model of experimental ileitis associated with increased prostanoid and nitric oxide production, spontaneous lymphatic contractions were nearly abolished.23,25 Although these findings are consistent with the conclusion that KATP channels mediated the reductions in contraction frequency, only the latter two studies specifically tested their possible role. In the experimental ileitis model, GLIB (10 µm) treatment essentially restored the lymphatic contraction frequency to normal levels,25 and in the metabolic syndrome model, GLIB (10 µm) partially restored the depression in contraction frequency.22 Collectively, these findings and ours point to a nearly selective impairment of lymphatic contraction frequency in models of metabolic stress, with little or no effect on contraction amplitude, suggesting that a common endpoint of the metabolic stress associated with these various disease models is primarily to inhibit the ionic pacemaker driving spontaneous contractions as opposed to interfering with excitation-contraction coupling. The lack of effect of mitochondrial ETC inhibitors on contraction amplitude in our study suggests that they do not have effects on L-type Ca2+ channels, although the slight blunting of contraction amplitude observed during rescue by GLIB may be related to the documented off-target effect of GLIB on the L-type channel.72–74 It will be important to test the extent to which GLIB treatment [at lower concentrations that are more specific for KATP channels in lymphatic muscle48] can restore impaired lymphatic function in other animal models of metabolic disease and if animals with lymphatic muscle deficient in Kir6.1 channels are resistant to the lymphatic contractile dysfunction associated with those models.

The preceding discussion is not meant to imply that KATP channels are the sole cause of lymphatic dysfunction in metabolic disease or to downplay the importance of other signaling mechanisms that might also negatively impact lymphatic contractile amplitude. Indeed, two of the studies cited above6,18 noted impairments in lymphatic contraction amplitude as well as frequency. Related studies have demonstrated this as well. For example, Liao et al.20 found that upregulation of nitric oxide (NO) production through iNOS (by injecting activated macrophages or CD11b + Gr-1 + cells expressing iNOS) led to the suppression of lymph transport in the mouse hindlimb. The effect appeared to be mediated both by changes in contraction amplitude and frequency, although (as with other in vivo models) a component of the frequency changes may have been due to systemic compensation in order to maintain fluid balance. In these and other studies, the effects on amplitude are likely mediated in part by nitric oxide (NO). For example, in a TNFα overexpression mouse model, the impairment in both contraction frequency and amplitude of ex vivo lymphatic vessels was partially rescued by blocking NO synthase.18 Likewise, iNOS inhibition with 1400 W largely restored the lymphatic contractions lost during experimental ileitis.25 Inhibition of eNOS by L-NAME partially reversed the impairment in lymphatic contraction frequency and amplitude in a mouse model of TNFα overexpression,18 a rat model of aging71 and a rat model of metabolic syndrome.22 The effects of NO on lymphatic contractile function are complex, but in general, low levels of NO production associated with shear-stress activation of eNOS result in slight enhancement of lymph pump output75,76 whereas higher levels of NO production, often associated with imposed flow or iNOS activation, generally depress both lymphatic contraction frequency and amplitude.18,22,48,62,71 To complicate matters, NO appears to induce KATP channel activation in some species25 but not others,48 perhaps depending on the relative activities of PKA and PKG in lymphatic muscle [for more detail see62]. Thus, the extent to which KATP channels may be activated directly by metabolic stress or secondary to NO and/or prostanoid production is likely to vary with the disease model.

In the context of metabolic disease, lymphatic contractile dysfunction can potentially trigger a complicated sequelae of long-term changes in overall lymphatic function and the interstitium. Such changes include peri-lymphatic inflammation, CD4+ cell infiltration, lipid accumulation, and fibrosis—all of which are associated with ROS production, iNOS activation, and/or the production of cytokines and prostanoids.24,77–80 For example, in addition to an impairment in lymphatic contractile function,15,16 obesity-prone mice show reduced lymphatic transport of macromolecules draining to lymph nodes along with decreased density of lymphatic vessels and reduced expression of lymphatic markers, all suggestive of both short- and long-term remodeling of the lymphatic vasculature and surrounding tissue.17 The long-term changes in lymphatic function may negatively impact the lymphatic endothelium, leading to collecting vessel hyperpermeability6,28,29 and compromised integrity of lymphatic valves.6,26,27 These, together with inhibition of the active lymph pump through KATP channel activation and/or NO production would contribute to overall lymphatic system dysfunction.

In summary, acute metabolic stress, either through reductions in the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio or increased ROS production, leads to activation of KATP channels in lymphatic muscle and inhibition of the ionic pacemaker driving spontaneous lymphatic contractions and active lymph transport. Mice lacking functional KATP channels in lymphatic muscle cells are resistant to the effects of acute metabolic stress, pointing to a common role for KATP channels in the impaired lymphatic contractile function observed in a number of metabolic diseases and raising the possibility that KATP channels in lymphatic muscle may be a viable therapeutic target.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Min Li and Shanyu Ho for technical assistance and mouse colony management. The advice of Colin Nichols, whose initial questions prompted this study, is greatly appreciated. The graphical abstract was created in BioRender, for which an appropriate publication license was obtained.

Contributor Information

Hae Jin Kim, Department of Medical Pharmacology & Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA.

Charles E Norton, Department of Medical Pharmacology & Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA.

Scott D Zawieja, Department of Medical Pharmacology & Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA.

Jorge A Castorena-Gonzalez, Department of Pharmacology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA.

Michael J Davis, Department of Medical Pharmacology & Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA.

Author Contributions

H.J.K., C.E.N., S.D.Z., and M.J.D. designed the experiments. H.J.K., J.A.C.-G., S.D.Z. and C.E.N. conducted the experiments. H.J.K., S.D.Z., J.A.C.-G., X.G., and M.J.D. analyzed the data. H.J.K. and M.J.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those eligible for authorship are listed.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL‐141107 and HL‐122578 to M.J.D., R01 HL-168568 to J.A.C.-G., and R00 HL-143198 to S.D.Z.; H.J.K. was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant NRF-2020R1A6A3A03037151.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report, financial or otherwise.

Data Availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper.

References

- 1. Levick JR, CC M. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gonzalez-Loyola A, TV P. Development and aging of the lymphatic vascular system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;169:63–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rockson SG. Secondary lymphedema: is it a primary disease?. Lymphatic Res Biol. 2008;6(2):63–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scallan JP, MJ D. Genetic removal of basal nitric oxide enhances contractile activity in isolated murine collecting lymphatic vessels. Journal of Physiology. 2013;591(8):2139–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao E, Watt MJ, Nowell CJ et al. Mesenteric lymphatic dysfunction promotes insulin resistance and represents a potential treatment target in obesity. Nat Metab. 2021;3(9):1175–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis MJ, Scallan JP, Castorena-Gonzalez JA et al. Multiple aspects of lymphatic dysfunction in an ApoE (-/-) mouse model of hypercholesterolemia. Front Physiol. 2022;13:1098408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang F, Zarkada G, Han J et al. Lacteal junction zippering protects against diet-induced obesity. Science. 2018;361(6402):599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis MJ, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Kim HJ, Li M, Remedi M, CG N. Lymphatic contractile dysfunction in mouse models of Cantu Syndrome with K(ATP) channel gain-of-function. Function (Oxf). 2023;4(3):zqad017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olszewski WL. Contractility patterns of normal and pathologically changed human lymphatics. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2002;979:52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rossitto G, Mary S, McAllister C et al. Reduced lymphatic reserve in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(24):2817–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rossitto G, Mary S, Chen JY et al. Tissue sodium excess is not hypertonic and reflects extracellular volume expansion. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J et al. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gasheva OY, Knippa K, Nepiushchikh ZV, Muthuchamy M, Gashev AA. Age-related alterations of active pumping mechanisms in rat thoracic duct. Microcirculation. 2007;14(8):827–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagai T, Bridenbaugh EA, Gashev AA. Aging-associated alterations in contractility of rat mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Microcirculation. 2011;18(6):463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blum KS, Karaman S, Proulx ST et al. Chronic high-fat diet impairs collecting lymphatic vessel function in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nitti MD, Hespe GE, Kataru RP et al. Obesity-induced lymphatic dysfunction is reversible with weight loss. J Physiol. 2016;594(23):7073–7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia Nores GD, Cuzzone DA, Albano NJ et al. Obesity but not high-fat diet impairs lymphatic function. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(10):1582–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scallan JP, Bouta EM, Rahimi H et al. Ex vivo demonstration of functional deficiencies in popliteal lymphatic vessels from TNF-transgenic mice with inflammatory arthritis. Front Physiol. 2021;12:745096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen Y, Rehal S, Roizes S, Zhu HL, Cole WC, von der Weid PY. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha inhibits lymphatic pumping via activation of the NF-kappaB-iNOS signaling pathway. Microcirculation. 2017;24(3):745096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liao S, Cheng G, Conner DA et al. Impaired lymphatic contraction associated with immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):18784–18789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zawieja SD, Wang W, Wu X, Nepiyushchikh ZV, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M. Impairments in the intrinsic contractility of mesenteric collecting lymphatics in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(3):H643–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zawieja SD, Wang W, Chakraborty S, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M. Macrophage alterations within the mesenteric lymphatic tissue are associated with impairment of lymphatic pump in metabolic syndrome. Microcirculation. 2016;23(7):558–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rehal S, von der Weid PY. Experimental ileitis alters prostaglandin biosynthesis in mesenteric lymphatic and blood vessels. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015;116-117:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rehal S, Stephens M, Roizes S, Liao S, von der Weid PY. Acute small intestinal inflammation results in persistent lymphatic alterations. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;314(3):G408–G417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mathias R, von der Weid PY. Involvement of the NO-cGMP-K(ATP) channel pathway in the mesenteric lymphatic pump dysfunction observed in the guinea pig model of TNBS-induced ileitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304(6):G623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castorena-Gonzalez JA. Lymphatic valve dysfunction in western diet-fed mice: new insights into obesity-induced lymphedema. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:823266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Czepielewski RS, Erlich EC, Onufer EJ et al. Ileitis-associated tertiary lymphoid organs arise at lymphatic valves and impede mesenteric lymph flow in response to tumor necrosis factor. Immunity. 2021;54(12):2795–2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lim HY, Rutkowski JM, Helft J et al. Hypercholesterolemic mice exhibit lymphatic vessel dysfunction and degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(3):1328–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scallan JP, Hill MA, Davis MJ. Lymphatic vascular integrity is disrupted in type 2 diabetes due to impaired nitric oxide signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107(1):89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440(7083):470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aittoniemi J, Fotinou C, Craig TJ, de Wet H, Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Review. SUR1: a unique ATP-binding cassette protein that functions as an ion channel regulator. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1514):257–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foster MN, Coetzee WA. KATP channels in the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(1):177–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brayden JE. Functional roles of KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29(4):312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Quayle JM, Nelson MT, Standen NB. ATP-sensitive and inwardly rectifying potassium channels in smooth muscle. Physiol Rev. 1997;77(4):1165–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davis MJ, Kim HJ, Zawieja SD et al. Kir6.1-dependent K(ATP) channels in lymphatic smooth muscle and vessel dysfunction in mice with Kir6.1 gain-of-function. J Physiol. 2020;598(15):3107–3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bhatti JS, Bhatti GK, Reddy PH. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—A step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(5):1066–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malester B, Tong X, Ghiu I et al. Transgenic expression of a dominant negative K(ATP) channel subunit in the mouse endothelium: effects on coronary flow and endothelin-1 secretion. Faseb J. 2007;21(9):2162–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Zawieja SD, Li M et al. Mechanisms of connexin-related lymphedema. Circ Res. 2018;123(8):964–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Scallan JP, MJ D. Differences in L-type Ca(2+) channel activity partially underlie the regional dichotomy in pumping behavior by murine peripheral and visceral lymphatic vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314(5):H991–H1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Davis MJ. Pressure acquisition and control program for quantitative assessment of lymphatic vessel function. 2023. 10.5281/zenodo.8286107. [DOI]

- 41. Davis MJ. An improved, computer-based method to automatically track internal and external diameter of isolated microvessels. Microcirculation. 2005;12(4):361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis MJ. Diameter tracking program for quantitative assessment of lymphatic vessel contractions. 2023. 10.5281/zenodo.8286119. [DOI]

- 43. Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJA et al. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radical Biol Med. 2012;52(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, EJ L. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: CENTRAL ROLE OF COMPLEX III*. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36027–36031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Norton CE, Jacobsen NL, Sinkler SY, Manrique-Acevedo C, Segal SS. Female sex and western-style diet protect mouse resistance arteries during acute oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020;318(3):C627–C639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scallan JP, Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, MJ D. Lymphatic pumping: mechanics, mechanisms and malfunction. J Physiol. 2016;594(24):5749–5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zuberek M, Paciorek P, Rakowski M, Grzelak A. How to use Respiratory chain inhibitors in toxicology studies-whole-cell measurements. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim HJ, Li M, Nichols CG, MJ D. Large-conductance calcium-activated K(+) channels, rather than KATP channels, mediate the inhibitory effects of nitric oxide on mouse lymphatic pumping. Br J Pharmacol. 2021;178:4119–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li N, Ragheb K, Lawler G et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone induces apoptosis through enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(20):8516–8525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang YQ, Shen X, Xiao XL et al. Mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone induces vasorelaxation without involving K(ATP) channel activation in smooth muscle cells of arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(21):3145–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davis MJ, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, SD Z. Electric field stimulation unmasks a subtle role for T-type calcium channels in regulating lymphatic contraction. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):15862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hancock EJ, Zawieja SD, Macaskill C, Davis MJ, Bertram CD. A dual-clock-driven model of lymphatic muscle cell pacemaking to emulate knock-out of Ano1 or IP3R. J Gen Physiol. 2023;155(12):e202313355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zawieja SD, Castorena JA, Gui P et al. Ano1 mediates pressure-sensitive contraction frequency changes in mouse lymphatic collecting vessels. J Gen Physiol. 2019;151(4):532–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim HJ, Li M, Erlich EC, Randolph GJ, Davis MJ. ERG K(+) channels mediate a major component of action potential repolarization in lymphatic muscle. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):14890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shi Y, Niculescu R, Wang D, Patel S, Davenpeck KL, Zalewski A. Increased NAD(P)H oxidase and reactive oxygen species in coronary arteries after balloon injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(5):739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shi Y, So KF, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Oxygen-derived free radicals mediate endothelium-dependent contractions in femoral arteries of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(7):1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baines CP. The cardiac mitochondrion: nexus of stress. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:61–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Norton CE, Shaw RL, Segal SS. Differential effects of high fat diets on resilience to H(2)O(2)-induced cell death in mouse cerebral arteries: role for processed carbohydrates. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(7):1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tokube K, Kiyosue T, Arita M. Openings of cardiac KATP channel by oxygen free radicals produced by xanthine oxidase reaction. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2):H478–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ichinari K, Kakei M, Matsuoka T, Nakashima H, Tanaka H. Direct activation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel by oxygen free radicals in guinea-pig ventricular cells: its potentiation by MgADP. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28(9):1867–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Marino A, Hausenloy DJ, Andreadou I, Horman S, Bertrand L, Beauloye C. AMP-activated protein kinase: a remarkable contributor to preserve a healthy heart against ROS injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;166:238–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Davis MJ, Kim HJ, CG N. KATP channels in lymphatic function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;323(4):C1018–C1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paggio A, Checchetto V, Campo A et al. Identification of an ATP-sensitive potassium channel in mitochondria. Nature. 2019;572(7771):609–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li X, Rapedius M, Baukrowitz T et al. 5-Hydroxydecanoate and coenzyme A are inhibitors of native sarcolemmal KATP channels in inside-out patches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800(3):385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hu H, Sato T, Seharaseyon J et al. Pharmacological and histochemical distinctions between molecularly defined sarcolemmal KATP channels and native cardiac mitochondrial KATP channels. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(6):1000–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. D'Hahan N, Moreau C, Prost AL et al. Pharmacological plasticity of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels toward diazoxide revealed by ADP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(21):12162–12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hanley PJ, Mickel M, Loffler M, Brandt U, Daut J. K(ATP) channel-independent targets of diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate in the heart. J Physiol. 2002;542(3):735–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Halestrap AP, Clarke SJ, Khaliulin I. The role of mitochondria in protection of the heart by preconditioning. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767(8):1007–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hanley PJ, Drose S, Brandt U et al. 5-Hydroxydecanoate is metabolised in mitochondria and creates a rate-limiting bottleneck for beta-oxidation of fatty acids. J Physiol. 2005;562(2):307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Davis MJ, SD Z. Pacemaking in the lymphatic system. J Physiol. 2024; Mar 23. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Akl TJ, Nagai T, Cote G, Gashev AA. Mesenteric flow in adult and aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol. 2011;301(5):H1828–H1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lee SY, CO L. Inhibition of Na+-K+ pump and L-type Ca2+ channel by glibenclamide in Guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(1):61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bian K, Hermsmeyer K. Glyburide actions on the dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel in rat vascular muscle. J Vasc Res. 1994;31(5):256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sadraei H, Beech DJ. Ionic currents and inhibitory effects of glibenclamide in seminal vesicle smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115(8):1447–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gasheva OY, Zawieja DC, Gashev AA. Contraction-initiated NO-dependent lymphatic relaxation: a self-regulatory mechanism in rat thoracic duct. J Physiol. 2006;575(3):821–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bohlen HG, Gasheva OY, DC Z. Nitric oxide formation by lymphatic bulb and valves is a major regulatory component of lymphatic pumping. Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol. 2011;301(5):H1897–H1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gardenier JC, Kataru RP, Hespe GE et al. Topical tacrolimus for the treatment of secondary lymphedema. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rockson SG, Tian W, Jiang X et al. Pilot studies demonstrate the potential benefits of antiinflammatory therapy in human lymphedema. JCI Insight. 2018;3(20):e123775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tian W, Rockson SG, Jiang X et al. Leukotriene B4 antagonism ameliorates experimental lymphedema. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(389):eaal13920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Angeli V, Llodra J, Rong JX et al. Dyslipidemia associated with atherosclerotic disease systemically alters dendritic cell mobilization. Immunity. 2004;21(4):561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper.