Abstract

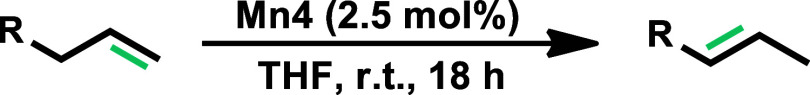

An additive-free manganese-catalyzed isomerization of terminal alkenes to internal alkenes is described. This reaction is implementing an inexpensive nonprecious metal catalyst. The most efficient catalyst is the borohydride complex cis-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)]. This catalyst operates at room temperature, with a catalyst loading of 2.5 mol %. A variety of terminal alkenes is effectively and selectively transformed into the respective internal E-alkenes. Preliminary results show chain-walking isomerization at an elevated temperature. Mechanistic studies were carried out, including stoichiometric reactions and in situ NMR analysis. These experiments are flanked by computational studies. Based on these, the catalytic process is initiated by the liberation of “BH3” as a THF adduct. The catalytic process is initiated by double bond insertion into an M-H species, leading to an alkyl metal intermediate, followed by β-hydride elimination at the opposite position to afford the isomerization product.

Keywords: isomerization, manganese, borohydride, alkenes, DFT calculations

Introduction

Isomerization and translocation of double bonds inside a molecule are essential steps in a variety of catalytic processes. Monoisomerization and especially chain-walking reactions enable the functionalization of a great variety of organic frameworks.1 The compounds thus obtained are widely used as fragrances, agrochemicals, and intermediates in the pharmaceutical industry.2 The field of transpositional isomerization catalysis has long been dominated by complexes based on precious metals, such as rhodium,3 iridium,4 ruthenium,5 and palladium.6 However, representatives of base metal catalysts in this field have been fathomed.7 The early development of nickel-8 and cobalt-based9 isomerization catalysts as well as industrial application of the latter10 represents some of the most established examples. Over the last years, base metal catalysts based on nickel,11 cobalt,12 and iron13 have emerged in the field of alkene isomerization.7,14 Selected base metal catalysts for the isomerization of alkenes are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selected examples of base metal olefin isomerization precatalysts.

As manganese is concerned, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one literature example described by Pidko and Filonenko.15 The authors utilized a cationic Mn(I) CNP pincer carbonyl precatalyst which, in the presence of K[HBEt3], was able to isomerize terminal carbon double bonds at 60 °C.

We have recently demonstrated the broad application of manganese(I) complexes based on fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)3(CH2CH2CH3)] (dippe = 1,2-bis(di-iso-propylphosphino)ethane) for hydrogenation and hydrofunctionalization reactions.16,17 Based on our recent findings, we describe here the activity of fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)3(CH2CH2CH3)] (Mn1),17afac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)3(H)] (Mn2),18cis-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-HBpin)] (Mn3),17c and cis-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)] (Mn4) as precatalysts for the selective isomerization of terminal alkenes to internal alkenes. A plausible reaction mechanism based on detailed experimental and theoretical studies is presented.

Results and Discussion

The new Mn(I) borohydride complex Mn4 was prepared in 79% yield by the treatment of Mn1 with NH3BH3 at 50 °C for 3.5 h. It was fully characterized by 1H, 13C{1H}, and 31P{1H} NMR and IR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS). The catalytic performance of Mn4 and the known Mn(I) complexes Mn1–Mn3 were then investigated for the isomerization of 1-allyl-4-fluorobenzene as a model substrate in THF as a solvent. Selected optimization experiments are depicted in Table 1. Although Mn1 effectively catalyzes a variety of hydrofunctionalizations,16 it turned out to be catalytically inactive for isomerization purposes. Likewise, hydride complex Mn2 was found to be inactive for the desired transformation. With Mn3 bearing the σ–B–H-bound HBpin ligand, full conversion to the internal alkene was achieved at 60 °C. However, lowering the temperature to 25 °C resulted in no catalytic activity. Mn4 afforded high conversion and yield with very good selectivity toward the E-isomer even at room temperature within 10 h. Notably, no additives were required to activate either Mn3 or Mn4. In other solvents such as CH2Cl2 and toluene, Mn4 was considerably less active and lower yields were achieved, whereas in DMSO, acetone, and MeOH, no reaction took place at all (Table 1, entries 8–12). Finally, in the absence of a catalyst, no reaction took place.

Table 1. Optimization Reactions for the Manganese-Catalyzed Transposition of 1-Allyl-4-fluorobenzenea.

| entry | [Mn] (mol %) | solvent | temp (°C) | conversion (%) | E/Z ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mn1 (3) | THF | 60 | ||

| 2 | Mn2 (3) | THF | 60 | ||

| 3 | Mn3 (3) | THF | 60 | >99 | 94:6 |

| 4 | Mn4 (3) | THF | 60 | >99 | 99:1 |

| 5 | Mn3 (3) | THF | 25 | ||

| 6 | Mn4 (2.5) | THF | 25 | >99 | 99:1 |

| 7 | Mn4 (1) | THF | 25 | 8 | 91:9 |

| 8 | Mn4 (2.5) | CH2Cl2 | 25 | 60 | 91:9 |

| 9 | Mn4 (2.5) | toluene | 25 | 42 | 95:5 |

| 10 | Mn4 (2.5) | DMSO | 25 | ||

| 11 | Mn4 (2.5) | acetone | 25 | ||

| 12 | Mn4 (2.5) | MeOH | 25 |

Reaction conditions: 1-allyl-4-fluorobenzene (0.5 mmol), [Mn], and 1,4-dioxane as an internal standard (0.13 mmol) in the respective solvent (0.5 mL) for 10 h. Conversion and the E/Z ratio were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Based on the optimized reaction conditions, the substrate scope and limitations were investigated. In order to achieve sufficient conversion for a broad variety of substrates, the reaction time was extended to 18 h. Starting with aromatic substrates, the desired 1,2-isomerized compound was obtained in high yields. Allylbenzene derivatives featuring strong electron-donating groups (e.g., −OTMS) to weak electron-donating groups (e.g., alkyl moieties) or electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., single or multiple fluorine atoms) were all successfully converted to the desired alkenes with excellent E-selectivity. Halides, ethers, and trimethylsilylethers (Table 2, 1a, 3a, and 4a) were well tolerated. A good performance on annulated systems is demonstrated by the isomerization of 1-allylnaphthalene (6a). The introduction of an ortho-methyl group led to a minor drop in selectivity (8a). A drastic decrease in selectivity was noted for mesityl substrate 11a (Table 2). Although an excellent yield was upheld, a strong interference of the methyl groups can be presumed from the E/Z ratio being decreased to about 3:2. Heterocycles such as thiophene and furan moieties were well tolerated (Table 2, 14a and 15a). However, it should be noted that 40 °C was required for these heteroaromatic systems.

Table 2. Catalytic 1,2-Transposition Reactions of Alkenes by Mn4a.

Reaction conditions: alkene substrate (0.5 mmol), Mn4 (2.5 mol %), and 1,4-dioxane as an internal standard (0.13 mmol) in THF-d8 (0.5 mL) at 25 °C for 18 h. Conversion, yield, and the E/Z ratio were determined by gas chromatography–MS (GC–MS) and 1H NMR spectroscopy. Results represent an average of two runs.

Isolated yield. n.d. = not detected.

While high reactivity was achieved for aliphatic systems, a drop in selectivity was observed (Table 2, 16a and 17a). This effect increased to a mere 55:45 E/Z ratio for trimethyl(pent-1-en-3-yloxy)silane (Table 2, 19a). Gratifyingly, more bulky olefins such as allyladamantane and allyltrimethylsilane underwent facile isomerization to afford 20a and 21a in high yields (Table 2). In comparison to the model substrate 1-allyl-4-fluorobenzene, a slight decrease in catalytic performance was noted, but high E/Z ratios were achieved. The conversion of vinylcyclohexane to the trisubstituted olefin ethylidenecyclohexane (Table 2, 18a) was explored. At room temperature, a conversion of 40% was not exceeded even with an extended reaction time of 36 h. However, heating to 40 °C for 18 h afforded 18a in 99% yield. No conversion could be observed for unprotected phenols, such as eugenol (Table 2, 22a).

Encouraged by these findings, we envisioned the application of Mn4 for the gram-scale synthesis of E-4-(prop-1-en-1-yl)-1,1′-biphenyl from 4-allyl-1,1′-biphenyl (Table 1, 9a). Satisfyingly, an isolated yield of 86% could be achieved, while a high product selectivity of 99:1 in favor of the E-isomer was upheld.

Preliminary studies of long-distance isomerization (chain walking) were conducted by increasing the reaction temperature. At room temperature, olefins 12 and 13 were converted into 12a and 13a, respectively, in 68 and 95% yields with E/Z ratios of 81:19 and 86:14 (Scheme 1). Upon addition of a new batch of catalyst at 70 °C, these olefins were further converted into the conjugated analogues 12b and 13b in 89 and 48% yields, respectively, with E/Z ratios of 90:10 and 99:1. It should be noted that in the case of the nonbranched terminal alkene 12, partial chain walking occurred already at room temperature, accounting for the lower yield of 12a. For the sterically more demanding 13a, the second transposition step is significantly more difficult even at a reaction temperature of 70 °C, leading to a lower yield of 13b. The formation of 12b and 13b from 12 and 13, respectively, was also achieved in one step with similar yields and E/Z ratios upon performing the reaction at 70 °C for 18 h. It has to be mentioned that in the case of the aliphatic substrates 16 and 17, no chain walking was observed.

Scheme 1. Preliminary Studies on Chain-Walking Isomerization Catalyzed by Mn4.

Having established the scope of the isomerization procedure, we turned our attention toward the investigation of the reaction mechanism. Over the last decades, different mechanisms for olefin isomerization by transition metals have been proposed.7,13b,19 Among those, the alkyl and radical mechanisms are the most prevalent. The alkyl mechanism involves the insertion of an olefin into a metal hydride, followed by β-hydride elimination to furnish the product. Following a similar sequence, the radical mechanism is based on the transfer of hydrogen radicals. In contrast to the previously mentioned pathways, the π-allyl mechanism proceeds exclusively in an intramolecular fashion through a 1,3-hydrogen shift.

A well-established method to distinguish the possible pathways described above is the crossover labeling experiment.15 We performed a crossover isomerization of allylbenzene-d2 (2-d2) and nondeuterated 4-allylanisole (4) (Scheme 2). An intramolecular hydrogen shift involved in the allyl mechanism would confine deuterium to the previously labeled substrate 2-d2. However, deuterium scrambling was found to extend to 4-allylanisole, yielding partially deuterated (E)-anethole-d (4a-d). Furthermore, a distribution of deuterium throughout the product propene chains was observed. Due to these findings, the involvement of an π-allyl mechanism in the isomerization catalyzed by Mn4 was excluded.

Scheme 2. Deuterium Crossover Labeling Experiment with Mn4.

To investigate the potential involvement of a radical mechanism, we performed an experiment with TEMPO as a radical trap. The presence of TEMPO is presumed to inhibit isomerization via a radical pathway. However, the presence of the radical trap did not affect the isomerization of compound 1 (Table 3, entry 1). No products of a reaction between TEMPO and a substrate radical could be detected. Therefore, we deem the involvement of a radical mechanism unlikely. Further mechanistic investigations focused on the hydride functionality, accompanied by an easily accessible coordination site. In order to test this assumption, pyridine and PMe3 were used as the additives.

Table 3. Isomerization Experiments with Additivesa.

| entry | additive (mol %) | solvent | yield (%) | E/Z ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TEMPO (12.5) | THF | 97 | 99:1 |

| 2 | pyridine (12.5) | THF | 77 | 96:4 |

| 3 | PMe3 (12.5) | THF |

Reaction conditions: 1-allyl-4-fluorobenzene (0.5 mmol), Mn4 (2.5 mol %), additive (12.5 mol %), and 1,4-dioxane as an internal standard (0.13 mmol) in THF-d8 (0.5 mL) at 25 °C for 10 h. Yield and the E/Z ratio were determined by 19F and 1H NMR spectroscopy.

The addition of pyridine (Table 3, entry 2) resulted in a significant decrease in the reactivity of Mn4. The isomerization of allylbenzene resulted in a yield of 77%, while in the presence of PMe3, no catalytic activity was observed (Table 3, entry 3). A deactivation by the strongly coordinating pyridine and PMe3 ligands is in line with the presence of a vacant coordination site during catalysis. Monitoring of the experiments involving pyridine and PMe3 by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy revealed the formation of new hydride species giving rise to signals at −4.52 (t, JHP = 54.8 Hz) and −9.00 (q, JHP = 49.3 Hz) ppm, respectively. These species are assigned to complexes Mn5 and Mn6, as shown in Scheme 3. While Mn5 could not be isolated in pure form, Mn6 could be isolated in 87% yield. Both compounds were fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy and HR-MS (Supporting Information).

Scheme 3. Syntheses of Hydride Complexes Mn5 and Mn6.

Attempts to in situ generate a coordinatively unsaturated hydride complex from Mn1 and H2 or NaBH4/MeOH did not result in productive catalysis.

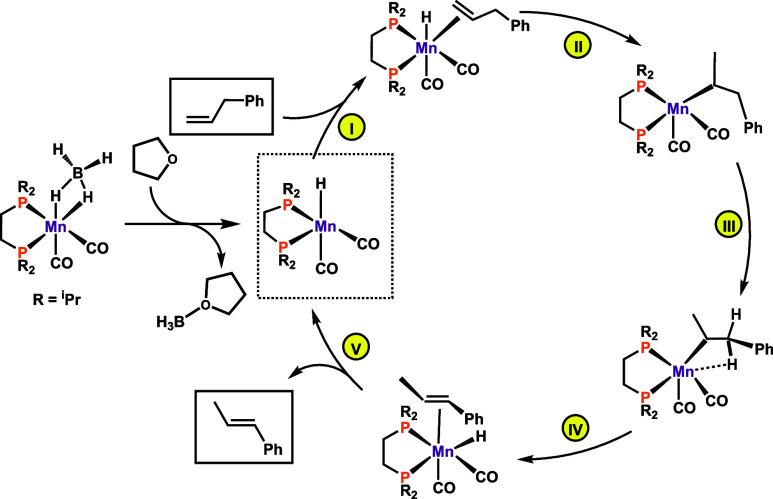

The above-mentioned findings strongly suggest an inner-sphere mechanism with a catalyst activation by loss of “BH3” as the rate-determining step. Deuterium labeling and radical trap experiments are consistent with a hydride mechanism operating via olefin insertion and β-hydride elimination, which is indeed supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (vide infra).

The reaction mechanism was explored in detail by means of DFT calculations,20 with allylbenzene taken as a model substrate and Mn4 (A in the calculations as a THF adduct) as a precatalyst in THF as a solvent. The resulting free energy profiles are presented in Figures 2–4, while Scheme 4 depicts a summary of the catalytic cycle. The free energy profile for the initiation process, where the active catalyst is formed, is depicted in Figure 2. The first step is the addition of a THF molecule in A to the B-atom of the BH4 ligand, thereby forming B containing a κ1-H-coordinated BH3·THF adduct. This first step requires a high barrier of 22 kcal/mol and is endergonic with ΔG = 18 kcal/mol. This is in line with in situ NMR spectroscopy during catalysis, where such a species could not be detected. The dominant species throughout the reaction was found to be Mn4 even upon full conversion. Dissociation of BH3·THF affords the catalytically active species C ([Mn(dippe)(CO)2H]) in an endergonic step (ΔG = 7 kcal/mol) with a barrier of 8 kcal/mol (see also Scheme 4).

Figure 2.

Free energy profile calculated for the activation of the precatalyst by the formation of a BH3·THF adduct. Free energies (kcal/mol) are referred to fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)] (Mn4) (A in the calculation in the form of Mn4·THF).

Figure 4.

Free energy profile calculated for the isomerization of allylbenzene to form E-prop-1-en-1-ylbenzene. Free energies (kcal/mol) are referred to fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)] (Mn4) (A in the calculation in the form of Mn4·THF).

Scheme 4. Simplified Catalytic Cycle for the Isomerization of Allylbenzene in THF.

Addition of allylbenzene affords complex D bearing a η2-bound CH2=CHCH2Ph ligand. In the next step of the reaction, the hydride migrates to the terminal olefin C atom, resulting in an alkyl complex E stabilized by a C–H agostic interaction with the terminal C–H bond (Figure 3). This is a very facile step with a barrier of merely 5 kcal/mol and a free energy balance of ΔG = 1 kcal/mol. In the following steps, the agostic interaction is cleaved to yield F, which is then further stabilized by forming an agostic interaction with the C–H bond adjacent to the phenyl substituent to give intermediate G. These processes are essentially thermoneutral and have a barrier of 11 kcal/mol.

Figure 3.

Free energy profile calculated for the isomerization of allylbenzene. Free energies (kcal/mol) are referred to fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)] (Mn4) (A in the calculation in the form of Mn4·THF).

Complex G undergoes β-elimination to form complex H featuring the η2-coordinated product olefin (Figure 4). The barrier is only 7 kcal/mol with a free energy balance of ΔG = 7 kcal/mol with respect to G. In the last step of the mechanism, E-CH3CH=CHPh (2a) is liberated from H to yield the coordinatively unsaturated hydride complex J. This complex undergoes facile isomerization to afford the catalytically active species K, thereby closing the catalytic cycle (see Scheme 4). It has to be noted that this intermediate is essentially identical to C but without the loosely bound BH3·THF adduct obtained in the initiating step (Figure 2). Closing the cycle from K back to D with the addition of a fresh allylbenzene molecule [K + CH3CH=CHPh (2a) → D] has a free energy balance of ΔG = −5 kcal/mol. In summary, initiation is an endergonic (ΔG = 19 kcal/mol) process with a barrier of 26 kcal/mol, from A to TSBC, while the catalytic cycle has a barrier of ΔG⧧ = 11 kcal/mol, from E to TSEF.

Formation of the Z-isomer of the product was also addressed by DFT mechanistic studies (see Supporting Information). The process involves a C–H agostic exchange in intermediate G, followed by β-elimination and the loss of the corresponding product Z-CH3CH=CHPh. The process has a barrier of 14 kcal/mol measured from G to the β-hydride elimination transition state TSLM, which is thus 4 kcal/mol less favorable than the formation of the E isomer. This is in good agreement with the experimental observations.

Conclusions

In sum, we have introduced an efficient protocol for the transposition of terminal alkenes catalyzed by the Mn(I) borohydride complex fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)]. The reported procedure operates at room temperature with a catalyst loading of 2.5 mol % and no additives. High reactivities and excellent E-selectivities were achieved for the allylbenzene derivatives. While maintaining good reactivity, the selectivity was slightly diminished for aliphatic systems. Increasing the steric bulk in these substrates re-established high E-selectivity. The protocol was also applied for gram-scale synthesis with 4-allyl-1,1′-biphenyl. Preliminary studies also showed a temperature-dependent chain-walking process leading to a sequential migration of the double bond. Deuterium labeling studies were carried out to gain insights into the reaction mechanism. The influence of additives such as pyridine and PMe3 on the reactivity of fac-[Mn(dippe)(CO)2(κ2-BH4)] was investigated, ultimately leading to the detection of hydride species. Both additives lead to deactivation by the strongly coordinating ligands, being in line with the requirement of a vacant coordination site during catalysis. DFT calculations indeed disclosed a typical inner sphere mechanism with all reacting fragments coordinated to the metal. The reaction proceeds via a metal hydride mechanism involving hydride insertion of the terminal C=C bond of the olefin, resulting in an alkyl complex. Consecutive β-elimination of the internal C–H bond adjacent to the substituent yields the isomerization product. Notably, formation of the E-isomer is favored both kinetically and thermodynamically.

Materials and Methods

General Procedure for Catalytic Reactions

Inside an argon flushed glovebox, an NMR tube was charged with a solution of Mn4 (0.0049 g, 0.013 mmol, 2.5 mol %) in THF-d8 (0.500 mL) and 1,4-dioxane (0.011 mL, 0.13 mmol) as an internal standard. The alkene substrate (0.50 mmol) was added, and the NMR tube was left to stand at room temperature. Experiments at elevated temperatures were conducted by placing the NMR tube in a preheated oil bath. The progress of the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR. After the indicated time, the reaction was quenched by exposure to air. GC–MS analysis was performed using butylbenzene as an internal standard. Isolated products were obtained by filtration over silica in PE and careful evaporation of the volatiles.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) is gratefully acknowledged (project no. P 32570-N). Centro de Química Estrutural (CQE) and Institute of Molecular Sciences (IMS) acknowledge the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (projects UIDB/00100/2020, UIDP/00100/2020, and LA/P/0056/2020).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.4c03364.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Vasseur A.; Bruffaerts J.; Marek I. Remote Functionalization through Alkene Isomerization. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 209–219. 10.1038/nchem.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fiorito D.; Scaringi S.; Mazet C. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Alkene Isomerization as an Enabling Technology in Tandem, Sequential and Domino Processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1391–1406. 10.1039/D0CS00449A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C. R.; Grotjahn D. B.. The Value and Application of Transition Metal Catalyzed Alkene Isomerization in Industry. Applied Homogeneous Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2017; pp 1365–1378. [Google Scholar]

- a Morrill T. C.; D’Souza C. A. Efficient Hydride-Assisted Isomerization of Alkenes via Rhodium Catalysis. Organometallics 2003, 22, 1626–1629. 10.1021/om0207358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dong W.; Yang H.; Yang W.; Zhao W. Rhodium-Catalyzed Remote Isomerization of Alkenyl Alcohols to Ketones. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 1265–1269. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yagupsky M.; Wilkinson G. Further Studies on Hydridocarbonyltris(Triphenylphosphine)Rhodium(I). Part II. Isomerisation of n-Pentenes and Hex-1-Ene. J. Chem. Soc. A 1970, 941–944. 10.1039/j19700000941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Y.; Qin C.; Jia X.; Leng X.; Huang Z. An Agostic Iridium Pincer Complex as a Highly Efficient and Selective Catalyst for Monoisomerization of 1-Alkenes to Trans-2-Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1614–1618. 10.1002/anie.201611007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Baudry D.; Ephritikhine M.; Felkin H. Isomerisation of Allyl Ethers Catalysed by the Cationic Iridium Complex [Ir(Cyclo-Octa-1,5-Diene)(PMePh2)2]PF6. A Highly Stereoselective Route to Trans-Propenyl Ethers. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1978, (16), 694–695. 10.1039/c39780000694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ohmura T.; Yamamoto Y.; Miyaura N. Stereoselective Synthesis of Silyl Enol Ethers via the Iridium-Catalyzed Isomerization of Allyl Silyl Ethers. Organometallics 1999, 18, 413–416. 10.1021/om980794e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d De-Botton S.; Filippov D. O. A.; Shubina E. S.; Belkova N. V.; Gelman D. Regioselective Isomerization of Terminal Alkenes Catalyzed by a PC(sp3)Pincer Complex with a Hemilabile Pendant Arm. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 5959–5965. 10.1002/cctc.202001308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hanessian S.; Giroux S.; Larsson A. Efficient Allyl to Propenyl Isomerization in Functionally Diverse Compounds with a Thermally Modified Grubbs Second-Generation Catalyst. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 5481–5484. 10.1021/ol062167o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McGrath D. V.; Grubbs R. H. The Mechanism of Aqueous Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Olefin Isomerization. Organometallics 1994, 13, 224–235. 10.1021/om00013a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sanz-Navarro S.; Mon M.; Doménech-Carbó A.; Greco R.; Sánchez-Quesada J.; Espinós-Ferri E.; Leyva-Pérez A. Parts–per–Million of Ruthenium Catalyze the Selective Chain–Walking Reaction of Terminal Alkenes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2831. 10.1038/s41467-022-30320-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Grotjahn D. B.; Larsen C. R.; Gustafson J. L.; Nair R.; Sharma A. Extensive Isomerization of Alkenes Using a Bifunctional Catalyst: An Alkene Zipper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9592–9593. 10.1021/ja073457i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Perdriau S.; Chang M.-C.; Otten E.; Heeres H. J.; de Vries J. G. Alkene Isomerisation Catalysed by a Ruthenium PNN Pincer Complex. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 15434–15442. 10.1002/chem.201403236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tan J.; Zhang Z.; Wang Z. A Novel Palladium-Catalyzed Hydroalkoxylation of Alkenes with a Migration of Double Bond. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1344–1348. 10.1039/b800838h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gauthier D.; Lindhardt A. T.; Olsen E. P. K.; Overgaard J.; Skrydstrup T. In Situ Generated Bulky Palladium Hydride Complexes as Catalysts for the Efficient Isomerization of Olefins. Selective Transformation of Terminal Alkenes to 2-Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7998–8009. 10.1021/ja9108424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kocen A. L.; Brookhart M.; Daugulis O. Palladium-Catalysed Alkene Chain-Running Isomerization. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 10010–10013. 10.1039/C7CC04953F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Larionov E.; Lin L.; Guénée L.; Mazet C. Scope and Mechanism in Palladium-Catalyzed Isomerizations of Highly Substituted Allylic, Homoallylic, and Alkenyl Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16882–16894. 10.1021/ja508736u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lim H. J.; Smith C. R.; RajanBabu T. V. Facile Pd(II)- and Ni(II)-Catalyzed Isomerization of Terminal Alkenes into 2-Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4565–4572. 10.1021/jo900180p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Liu X.; Li B. Base-Metal-Catalyzed Olefin Isomerization Reactions. Synthesis 2019, 51, 1293–1310. 10.1055/s-0037-1612014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lochow C. F.; Miller R. G. Nickel-Promoted Isomerizations of Alkenes Bearing Polar Functional Groups. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3020–3022. 10.1021/jo00880a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck R. F.; Breslow D. S. The Reaction of Cobalt Hydrotetracarbonyl with Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 4023–4027. 10.1021/ja01480a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keim W. Oligomerization of Ethylene to α-Olefins: Discovery and Development of the Shell Higher Olefin Process (SHOP). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12492–12496. 10.1002/anie.201305308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tricoire M.; Wang D.; Rajeshkumar T.; Maron L.; Danoun G.; Nocton G. Electron Shuttle in N-Heteroaromatic Ni Catalysts for Alkene Isomerization. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1881–1888. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kapat A.; Sperger T.; Guven S.; Schoenebeck F. E-Olefins through Intramolecular Radical Relocation. Science 2019, 363, 391–396. 10.1126/science.aav1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wu Q.; Wang L.; Jin R.; Kang C.; Bian Z.; Du Z.; Ma X.; Guo H.; Gao L. Nickel-Catalyzed Allylic C(sp2)–H Activation: Stereoselective Allyl Isomerization and Regiospecific Allyl Arylation of Allylarenes. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2016, 2016, 5415–5422. 10.1002/ejoc.201600955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Liu C.-F.; Wang H.; Martin R. T.; Zhao H.; Gutierrez O.; Koh M. J. Olefin Functionalization/Isomerization Enables Stereoselective Alkene Synthesis. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 674–683. 10.1038/s41929-021-00658-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kim D.; Pillon G.; DiPrimio D. J.; Holland P. L. Highly Z-Selective Double Bond Transposition in Simple Alkenes and Allylarenes through a Spin-Accelerated Allyl Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3070–3074. 10.1021/jacs.1c00856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu X.; Zhang W.; Wang Y.; Zhang Z.-X.; Jiao L.; Liu Q. Cobalt-Catalyzed Regioselective Olefin Isomerization Under Kinetic Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6873–6882. 10.1021/jacs.8b01815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bergamaschi E.; Beltran F.; Teskey C. J. Visible-Light Controlled Divergent Catalysis Using a Bench-Stable Cobalt(I) Hydride Complex. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5180–5184. 10.1002/chem.202000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang S.; Bedi D.; Cheng L.; Unruh D. K.; Li G.; Findlater M. Cobalt(II)-Catalyzed Stereoselective Olefin Isomerization: Facile Access to Acyclic Trisubstituted Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 8910–8917. 10.1021/jacs.0c02101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Scheuermann M. L.; Johnson E. J.; Chirik P. J. Alkene Isomerization–Hydroboration Promoted by Phosphine-Ligated Cobalt Catalysts. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2716–2719. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Meng Q.-Y.; Schirmer T. E.; Katou K.; König B. Controllable Isomerization of Alkenes by Dual Visible-Light-Cobalt Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5723–5728. 10.1002/anie.201900849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gao Y.; Li X.; Stevens J. E.; Tang H.; Smith J. M. Catalytic 1,3-Proton Transfer in Alkenes Enabled by Fe = NR Bond Cooperativity: A Strategy for pKa-Dictated Regioselective Transposition of C = C Double Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 11978–11987. 10.1021/jacs.2c13350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Woof C. R.; Durand D. J.; Fey N.; Richards E.; Webster R. L. Iron Catalyzed Double Bond Isomerization: Evidence for an FeI/FeIII Catalytic Cycle. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 5972–5977. 10.1002/chem.202004980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jennerjahn R.; Jackstell R.; Piras I.; Franke R.; Jiao H.; Bauer M.; Beller M. Benign Catalysis with Iron: Unique Selectivity in Catalytic Isomerization Reactions of Olefins. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 734–739. 10.1002/cssc.201100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Garhwal S.; Kaushansky A.; Fridman N.; de Ruiter G. Part per Million Levels of an Anionic Iron Hydride Complex Catalyzes Selective Alkene Isomerization via Two-State Reactivity. Chem Catal. 2021, 1, 631–647. 10.1016/j.checat.2021.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Yu X.; Zhao H.; Li P.; Koh M. J. Iron-Catalyzed Tunable and Site-Selective Olefin Transposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18223–18230. 10.1021/jacs.0c08631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Mayer M.; Welther A.; Jacobi von Wangelin A. Iron-Catalyzed Isomerizations of Olefins. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 1567–1571. 10.1002/cctc.201100207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Findlater M.; Zhang S. Cobalt-Catalyzed Isomerization of Alkenes. Synthesis 2021, 53, 2787–2797. 10.1055/a-1464-2524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Obeid A.-H.; Hannedouche J. Iron-Catalyzed Positional and Geometrical Isomerization of Alkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 1100–1111. 10.1002/adsc.202300052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Chernyshov I. Y.; Weber M.; Pidko E. A.; Filonenko G. A. Switching between Hydrogenation and Olefin Transposition Catalysis via Silencing NH Cooperativity in Mn(I) Pincer Complexes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10818–10825. 10.1021/acscatal.2c02963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S.; Kirchner K. Manganese Alkyl Carbonyl Complexes: From Iconic Stoichiometric Textbook Reactions to Catalytic Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2740–2751. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Weber S.; Stöger B.; Veiros L. F.; Kirchner K. Rethinking Basic Concepts - Hydrogenation of Alkenes Catalyzed by Bench-Stable Alkyl Mn(I) Complexes. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 9715–9720. 10.1021/acscatal.9b03963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Weber S.; Glavic M.; Stöger B.; Pittenauer E.; Podewitz M.; Veiros L. F.; Kirchner K. Manganese-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Silylation of Alkenes Following Two Parallel Inner-Sphere Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17825–17832. 10.1021/jacs.1c09175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Weber S.; Zobernig D. P.; Stöger B.; Veiros L. F.; Kirchner K. Hydroboration of Terminal Alkenes and trans-1,2-Diboration of Terminal Alkynes Catalyzed by a Mn(I) Alkyl Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 24488–24492. 10.1002/anie.202110736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduño J. A.; García J. J. Non-Pincer Mn(I) Organometallics for the Selective Catalytic Hydrogenation of Nitriles to Primary Amines. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 392–401. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Biswas S. Mechanistic Understanding of Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Olefin Isomerization: Metal-Hydride Insertion-Elimination vs. π-Allyl Pathways. Comm. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 35, 300–330. 10.1080/02603594.2015.1059325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Crabtree R. H.The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals, 6th ed.; Wiley & Sons, Inc, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Wiley-Blackwell: New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- a Parr R. G.; Yang W.. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Oxford University Press: New York, 1989. [Google Scholar]; b Free energy values were obtained at the M06/6-311++G(d, p)//PBE0/(SDD,6-31G(d,p)) level using the Gaussian 09 package. All calculations included solvent effects (THF) using the PCM/SMD model. A full account of the computational details and a complete list of references are provided as Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.