Abstract

Background

There is currently no research on the correlation between novel inflammatory indexes systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and the risk of anemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD) population, as well as survival analysis in CKD with anemia.

Methods

This investigation encompassed 4444 adult subjects out of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2005 and 2018. The study utilized multi-variable logistic regression to assess the relationship between SII, NLR, PLR, and anemia risk occurrence in CKD population. Survival differences in CKD patients with anemia, based on varying levels of SII, NLR, and PLR were evaluated employing Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

The adjusted logistic regression model demonstrates that SII, NLR, and PLR are associated with the risk of anemia occurrence in CKD population. Kaplan–Meier’s analysis reveals significant differences in survival rates among CKD patients with anemia stratified by NLR levels. The adjusted Cox proportional hazards model shows that the higher NLR group has a 30% elevated risk of all-cause mortality contrasted with lower group (hazard ratio, HR: 1.30, confidence interval (CI) [1.01, 1.66], p value <.04). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) demonstrates no nonlinear relationship between NLR and all-cause mortality. Lastly, sub-cohort analysis indicates that in populations with diabetes, hypertension, and hyperuricemia, NLR levels have a greater impact on all-cause mortality.

Conclusions

Controlling inflammation may reduce the occurrence of anemia in CKD populations, with NLR serving to be a potential prognostic indicator for survival results within CKD patients suffering from co-morbid anemia.

Keywords: Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, chronic kidney disease, anemia, NHANES

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is characterized as either structural or functional renal impairment persisting for more than three months [1]. A meta-analysis encompassing nearly seven million people showed that the global incidence of CKD is about 11–13% [2]. Therefore, CKD has become a heavy global public health burden. As renal function declines in CKD patients, sodium retention, toxin accumulation, hormonal malfunctions, metabolic disorders, and the state of micro-inflammation will occur, all of which could lead to impairment of blood system [3]. Anemia, a prevalent hematological complication in CKD patients, can manifest early in the disease course, increasing in prevalence and severity as the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases. Cross-sectional data assessment out of the 2007–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated that anemia prevalence was doubly high in CKD patients (15.4%) compared to the general population (7.6%). The prevalence of anemia escalated with advancing CKD stages, ranging from 8.4% at phase 1 to 53.4% at phase 5 [4]. Prior research has identified anemia as a risk factor for increased cardiovascular morbidity, hospitalization rates, and diminished quality of life among CKD patients [5]. In addition, anemia significantly increases patients’ economic burden [6]. However, several studies have shown that anemia in patients with CKD is still under identified and under treated to some extent [7,8].

Many metabolites, including endotoxin, hyperphosphate, and homocysteine, are proinflammatory [9–11]. As renal function declines, metabolites gradually accumulate in the body, thus CKD patients are in a chronic inflammatory state [12]. Numerous studies have implicated inflammation in the etiology of renal anemia. Many pro-inflammatory factors are known to inhibit the proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells, affect iron transport, inhibit erythropoietin (EPO) synthesis and activity, and influence erythrocyte longevity [13–15]. Thus, inflammation may be an important risk factor for the development of anemia in the CKD patients. However, due to the cumbersome and expensive detection of traditional inflammation indicators including interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), their application in primary hospitals is limited. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) were initially developed by researchers to predict the prognosis of patients with tumors and severe illnesses [16–18], as they are based on counts of peripheral lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets, which can better reflect the balance of individual inflammatory and immune status. With continued research into these markers, it has been discovered that these inflammatory indices are associated with the risk of developing chronic inflammatory diseases not related to tumors [19,20] and perform well in predicting the prognosis of non-tumor disease populations [21,22]. Although it is generally accepted that anemia in the CKD population is closely related to the body’s inflammatory state, the relationship between these inflammatory markers and the risk of anemia in the CKD population has not yet been revealed, nor is it clear how they perform in predicting the survival prognosis of the CKD population with anemia.

Hence, this research aims to investigate the association between these novel inflammatory indicators and the risk of developing anemia in CKD population, as well as their relationship with all-cause mortality within the renal anemia population, using the data from NHANES and National Death Index (NDI) databases, to contribute to the improvement of anemia and the reduction of all-cause mortality in CKD patient.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and data source

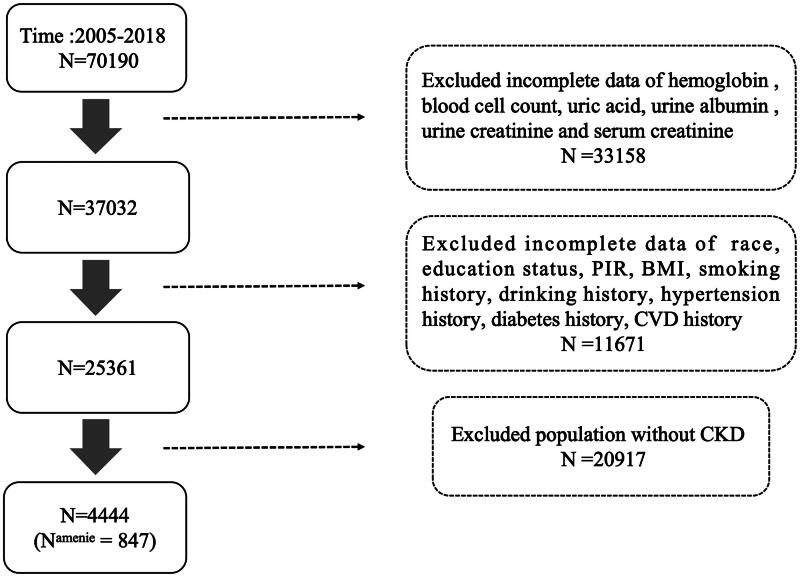

This investigation encompassed 4444 adults (20 or older) out of the NHANES performed spanning from 2005 to 2018. NHANES aims to assess the health as well as nutritional condition of grown-ups and children throughout the United States by collecting data via surveys, physical examinations, as well as laboratory tests in various regions. Exclusion criteria for research participants included missing values for hemoglobin (Hb), blood cell count tests, missing data on kidney function-related indicators such as blood creatinine, urine albumin, urine creatinine, missing survival data, as well as missing demographic information and past medical history. The National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Committee approved NHANES project and the informed consent of all NHANES participants can be viewed on the CDC website. Since the data used in this study are publicly available, it is exempt from ethical review involving human subjects. The criteria for participant inclusion and exclusion are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screening process flowchart for participant selection. PIR: ratio of family income to poverty; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; BMI: body mass index.

2.2. Inflammatory index

Data on leukocyte counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets) obtained from NHANES were utilized to compute the SII, NLR, as well as PLR [23]. Samples with values that deviate significantly from the overall distribution will be excluded to avoid skewing the results. The formulas used are: SII = platelet count multiplied by neutrophil count divided by lymphocyte count; NLR = neutrophil count divided by lymphocyte count; PLR is platelet count divided by lymphocyte count. Based on these quartiles of these inflammatory markers, participants were categorized to high and low groups, with those above the 3/4 quartile classified as the high group and those below the 3/4 quartile classified as the low group.

2.3. Anemia

Anemia was identified employing the World Health Organization’s diagnostic criteria: adult males having serum Hb degrees below 13 g/dL as well as non-pregnant adult females with levels below 12 g/dL were categorized as anemic [24].

2.4. Chronic kidney disease

The diagnosis of CKD follows the clinical practice recommendations for CKD outlined in Kidney Disease: Enhancing Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2020 [25]: (1) kidney damage (structural or functional) persisting for more than 3 months, including histological or imaging abnormalities, tubular damage, abnormal urine sediment, proteinuria, or a kidney transplantation history, with or without a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR); (2) decrease in GFR of unknown cause persisting for more than 3 months. The phase of CKD is decided by the KDIGO consensus [26] and is based on the eGFR derived employing the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration algorithm. These steps are explained in the following manner: classification of renal function stages: stage I: optimal renal performance characterized by a GFR of 90 mL/(min·1.73 m2) or higher. Stage II: A slight reduction in renal efficiency, with GFR values ranging between 60 and 89 mL/(min·1.73 m2). Stage IIIa: Mild to moderate decline in renal function, as indicated by a GFR between 45 and 59 mL/(min·1.73 m2). Stage IIIb: Moderate reduction in kidney function, with GFR levels spanning between 30 and 44 mL/(min·1.73 m2). Stage IV: Significant impairment in renal function, indicated by a GFR between 15 and 29 mL/(min·1.73 m2). Stage V: Renal failure, identified by a GFR of less than 15 mL/(min·1.73 m2).

2.5. Primary outcome

The principal outcome assessed was all-cause mortality. Survival data for participants were acquired through linkage with the NDI public dataset (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality-public.htm). Recorded details for deceased subjects included their death date and death cause, categorized employing the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) codes.

2.6. Covariates

Information regarding demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and health status was collected from NHANES 2005–2018. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race (non-Hispanic white, Mexican American, non-Hispanic black, other Hispanic, other race), education status (less than 9th grade, 9–11th grade, high school graduate or equivalent, some college or AA degree, college graduate or above), ratio of family income to poverty (PIR) [27]. Lifestyle information included smoking status (never smoked, former smoker, current smoker) and alcohol consumption status (non-drinker, drinker) [28]. Health information included body mass index (BMI), history of diabetes (Hb A1C concentration ≥6.5%, fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL, or self-reported diabetes) [29], history of hypertension (average of three consecutive measurements of systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥80 mmHg, self-reported history of hypertension, or use of antihypertensive medication), history of hyperuricemia (serum uric acid level ≥420 μmol/L for men, ≥360 μmol/L for women) [30], and history of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, angina pectoris, stroke, myocardial infarction).

2.7. Data analysis

The analysis used sample weights to make the results representative of the US community population. Characteristics of the NHANES 2005–2018 sample were segmented into two groups based on anemia diagnosis. The comparison of continuous and categorical variables between these groups utilized the Wilcoxon rank-sum and the Chi-square testing, respectively. Multi-variable logistic regression was applied to compute odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for examining the associations involving the SII, NLR, PLR, and anemia risk in the CKD population. Additionally, we analyzed the relationship between inflammation markers and red blood cell counts. Metabolic byproducts in the CKD population, such as indoxyl sulfate and inorganic phosphates, are involved in processes related to red blood cell death (see Supplementary Table 1). Kaplan–Meier’s estimates evaluated disparities in all-cause mortality among CKD patients with varying levels of SII, NLR, and PLR. Additionally, models for Cox proportional hazards quantified hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs to assess the effects of inflammation levels on mortality in anemic CKD patients. To thoroughly account for confounders, three analytical models were developed: model 1 performed univariate analyses solely on inflammation levels; model 2 incorporated demographic factors such as age, gender, race, education, and PIR; in model 3, additional adjustments were made for various demographic factors, including gender, race, age, education, PIR, BMI, smoking history, alcoholic beverage history, diabetes, hypertension, hyperuricemia, cardiovascular disease history, as well as the CKD phase. Furthermore, the study employed multi-variable Cox proportional hazards models using limited cubic spline curves to investigate potential nonlinear associations between inflammatory markers and death at the fifth, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentages of these markers. Stratified analyses determined the consistency of the relationship between NLR and mortality across various subgroup, segmented by gender, age, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, and CKD stage. R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was employed for conducting statistical analysis. All experiments performed were two-sided, and a significance level of .05 was employed to establish statistical significance.

3. Findings

3.1. Baseline characteristics of the participants

A total of 4444 American adults diagnosed with CKD were included, among whom 847 participants had anemia (Table 1; attributes of the anemia group are provided within Supplementary Table 2). The average age of participants was 60.64 (±0.39) years, with females accounting for 52.27%. In the anemia group, the average Hb concentration was 11.35 (±0.04) g/dL, as well as the average eGFR was 57.52 (±1.35) mL/(min·1.73 m2). The mean values of SII, NLR, and PLR were 703.57 (±29.39), 2.77 (0.08), and 152.63 (3.55), respectively. Additionally, participants with anemia had a lower proportion of smokers, drinkers, and obesity, and a higher proportion of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperuricemia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of CKD participants aged 20 years and older from the NHANES 2005 to 2018.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 4444) | Non-anemia (N = 3597) | Anemia (N = 847) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.64 (0.39) | 59.65 (0.42) | 66.53 (0.68) | <.0001 |

| Gender | .92 | |||

| Female | 2323 (52.27) | 1890 (57.26) | 433 (57.05) | |

| Male | 2121 (47.73) | 1707 (42.74) | 414 (42.95) | |

| Race | <.0001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2230 (50.18) | 1897 (73.81) | 333 (59.68) | |

| Mexican American | 593 (13.34) | 497 (6.80) | 96 (6.60) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 977 (21.98) | 671 (9.68) | 306 (24.46) | |

| Other Hispanic | 350 (7.88) | 287 (4.27) | 63 (4.46) | |

| Other race | 294 (6.62) | 245 (5.44) | 49 (4.80) | |

| Education status | <.0001 | |||

| Less than 9th grade | 664 (14.94) | 499 (8.06) | 165 (13.96) | |

| 9–11th grade | 741 (16.67) | 598 (13.18) | 143 (15.66) | |

| High school grade | 1092 (24.57) | 880 (24.93) | 212 (27.36) | |

| College | 1190 (26.78) | 977 (30.65) | 213 (25.79) | |

| College graduate or above | 757 (17.03) | 643 (23.18) | 114 (17.23) | |

| PIR | 2.70 (0.05) | 2.75 (0.05) | 2.35 (0.07) | <.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | .39 | |||

| <18.5 | 80 (1.8) | 70 (2.17) | 10 (1.57) | |

| 18.5–24 | 782 (17.6) | 606 (18.49) | 176 (21.15) | |

| 24–27 | 777 (17.48) | 625 (17.10) | 152 (18.48) | |

| >27 | 2805 (63.12) | 2296 (62.25) | 509 (58.80) | |

| Smoking | <.0001 | |||

| Never smoker | 2200 (49.5) | 1746 (49.62) | 454 (53.57) | |

| Former smoker | 1467 (33.01) | 1169 (32.39) | 298 (36.28) | |

| Current smoker | 777 (17.48) | 682 (17.99) | 95 (10.15) | |

| Drinking | <.0001 | |||

| No | 1538 (34.61) | 1186 (29.37) | 352 (39.35) | |

| Yes | 2906 (65.39) | 2411 (70.63) | 495 (60.65) | |

| Diabetes | <.0001 | |||

| No | 2711 (61) | 2267 (68.77) | 444 (57.65) | |

| Yes | 1733 (39) | 1330 (31.23) | 403 (42.35) | |

| Hypertension | <.0001 | |||

| No | 1015 (22.84) | 877 (28.38) | 138 (15.93) | |

| Yes | 3429 (77.16) | 2720 (71.62) | 709 (84.07) | |

| CKD stage | <.0001 | |||

| G1–G2 | 2286 (51.44) | 1998 (55.61) | 288 (33.01) | |

| G3–G5 | 2158 (48.56) | 1599 (44.39) | 559 (66.99) | |

| Hyperuricemia | <.0001 | |||

| No | 2919 (65.68) | 2440 (68.16) | 479 (57.11) | |

| Yes | 1525 (34.32) | 1157 (31.84) | 368 (42.89) | |

| CVD | <.0001 | |||

| No | 3220 (72.46) | 2686 (78.24) | 534 (62.85) | |

| Yes | 1224 (27.54) | 911 (21.76) | 313 (37.15) | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.86 (0.04) | 14.28 (0.03) | 11.35 (0.04) | <.0001 |

| eGFR (mL/(min·1.73 m2)) | 72.56 (0.59) | 75.10 (0.66) | 57.42 (1.33) | <.0001 |

| Scr (mg/dL) | 1.12 (0.01) | 1.05 (0.01) | 1.54 (0.05) | <.0001 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 354.89 (1.98) | 350.92 (1.99) | 378.57 (5.50) | <.0001 |

| SII | 613.59 (8.92) | 598.64 (8.49) | 702.77 (29.49) | <.001 |

| NLR | 2.53 (0.03) | 2.49 (0.03) | 2.77 (0.08) | .002 |

| PLR | 133.25 (1.35) | 130.06 (1.31) | 152.26 (3.57) | <.0001 |

| Red blood cell count (million cells/μL) | 4.54 (0.01) | 4.65 (0.01) | 3.88 (0.02) | <.0001 |

PIR: ratio of family income to poverty; BMI: body mass index; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; Hb: hemoglobin; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; Scr: serum creatinine; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Continuous variables with a normal distribution were presented as mean values along with their standard deviations (SDs), while categorical variables were expressed as proportions. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed to compare continuous variables, and Chi-square testing was utilized for categorical variables. We adjusted for sample weights from the mobile examination center to ensure the representativeness of results for the US civilian resident population.

3.2. Relationship between inflammatory indexes and risk of anemia among CKD population

The study utilized multi-variable logistic regression analysis to explore the correlations between SII, NLR, PLR and the risk of anemia in the CKD population. Model 1 initially demonstrated a strong correlation between elevated levels of inflammatory indices and a higher risk of anemia among individuals with CKD. Subsequent adjustments in model 3 for age, gender, race, educational attainment, PIR, BMI, smoking, and alcohol use histories, as well as histories of hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, cardiovascular disease, and CKD stage, confirmed the persistence of these associations. Specifically, the correlation with SII (OR: 1.56, 95% CI [1.16, 2.11], p value <.005) and NLR (OR: 1.44, 95% CI [1.00, 2.07], p value <.05) was intensified, whereas the association with PLR (OR: 1.75, 95% CI [1.33, 2.30], p value <.001) slightly diminished (Table 2).

Table 2.

The relationship between SII, NLR, PLR, and the risk of anemia occurrence in CKD patients.

| Inflammatory index | Group | Anemia/total | OR (95% CI), p value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

| SII | Low | 516/3000 | – | |||||

| High | 331/1444 | 1.48 (1.20, 1.84) | .001 | 1.55 (1.16, 2.07) | .004 | 1.56 (1.16, 2.11) | .005 | |

| NLR | Low | 503/2873 | – | |||||

| High | 344/1571 | 1.40 (1.13, 1.73) | .002 | 1.55 (1.10, 2.19) | .01 | 1.44 (1.00, 2.07) | .05 | |

| PLR | Low | 496/3086 | – | |||||

| High | 351/1358 | 1.88 (1.58, 2.25) | .0001 | 1.82 (1.40, 2.38) | .0001 | 1.75 (1.33, 2.30) | .001 | |

OR: odd rate; –: reference; CI: confidence interval; PIR: ratio of family income to poverty; CKD: chronic kidney disease; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Sampling weights were considered in logistic regression analyses to obtain nationally representative estimates.

Unadjusted.

Adjusted for gender, age, race, education status, and PIR.

Model 2 + adjusted for smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia history, cardiovascular disease history, and CKD stage.

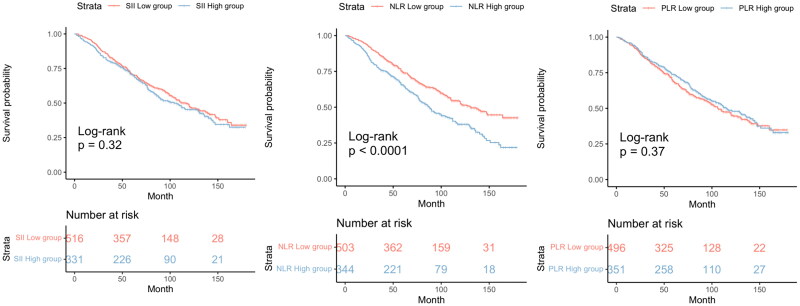

3.3. Relationship between inflammatory indices and all-cause mortality in anemic CKD patients

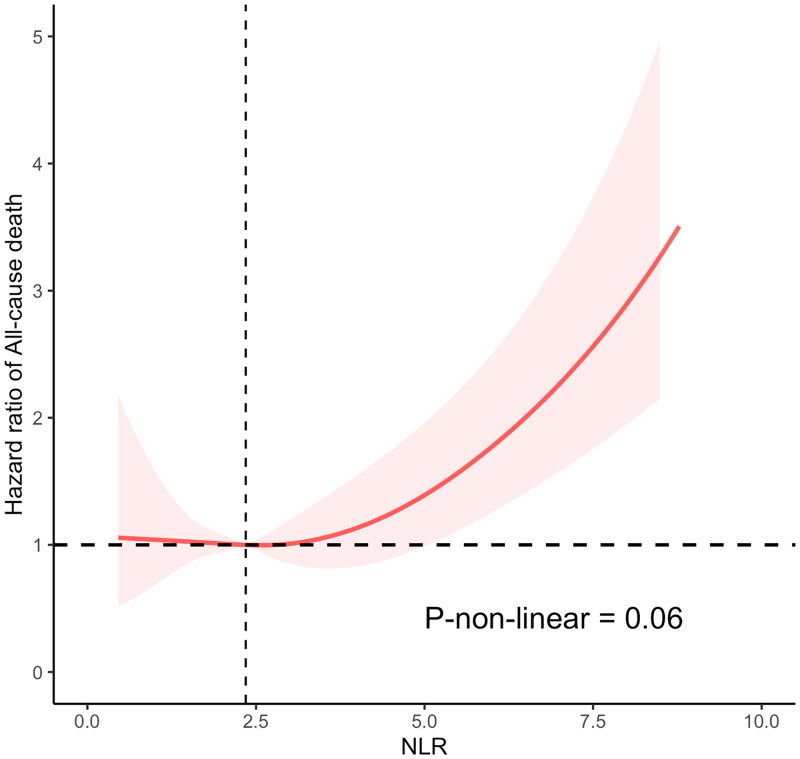

Among the 847 individuals diagnosed with CKD and anemia, 390 deaths succumbed over a median monitoring period of 71 months. Kaplan–Meier’s curves illustrated a significantly elevated mortality rate among anemic CKD patients within the high NLR group compared to their counterparts in the low NLR group (p value <.0001) (Figure 2). However, mortality rates showed no variance when assessed against SII and PLR levels. The unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model revealed a 57% increase in mortality risk for the high NLR cohort relative to the low NLR cohort (HR: 1.57, CI [1.24, 2.00], p value <.001). This finding remained consistent in model 3, which adjusted for demographic and health variables including age, sex, race, educational attainment, PIR, BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption histories, as well as histories of hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, cardiovascular disease, and CKD phase (HR: 1.30, CI [1.01, 1.66], p value <.04) (Table 3). Nonetheless, no significant correlations were observed between SII, PLR, and survival rates in CKD patients with anemia. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis indicated an absence of a nonlinear relationship between NLR as a continuous variable and all-cause mortality in anemic CKD patients (p-nonlinear = .06) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of all-cause death in the groups of high and low SII, NLR, PLR levels during the follow-up period. SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Table 3.

The relationship between SII, NLR, PLR, and the all-cause mortality rate of CKD patients with anemia.

| Inflammatory index | Group | Death/total | HR (95% CI), p value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

| SII | Low | 230/516 | – | |||||

| High | 160/331 | 1.04 (0.81, 1.34) | .7 | 0.90 (0.67, 1.23) | .5 | 0.88 (0.62, 1.25) | .5 | |

| NLR | Low | 203/503 | – | |||||

| High | 187/344 | 1.57 (1.24, 2.00) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.02, 1.60) | .034 | 1.30 (1.01, 1.66) | .04 | |

| PLR | Low | 226/496 | – | |||||

| High | 164/351 | 0.84 (0.66, 1.07) | .2 | 0.85 (0.67, 1.09) | .2 | 0.81 (0.62, 1.05) | .12 | |

HR: hazard ratio; –: reference; CI: confidence interval; PIR: ratio of family income to poverty; CKD: chronic kidney disease; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Sampling weights were considered in Cox proportional hazards model analyses to obtain nationally representative estimates.

Unadjusted.

Adjusted for gender, age, race, education status, and PIR.

Model 2 + adjusted for smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia history, cardiovascular disease history, and CKD stage.

Figure 3.

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses between NLR and all-cause mortality of CKD participants with anemia. NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

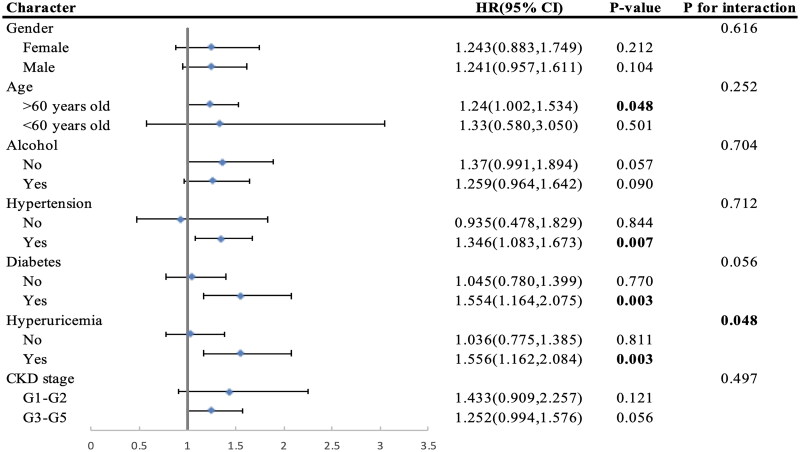

3.4. Sub-cohort analysis and sensitivity analysis

Stratified analysis was utilized to evaluate whether the association involving NLR and all-cause mortality among CKD patients suffering from anemia was consistent across different demographic characteristics and comorbidities. The results revealed that in subcohorts with hypertension (HR: 1.346, CI [1.083, 1.673], p value <.007), diabetes (HR: 1.554, CI [1.164, 2.075], p value <.003), and hyperuricemia (HR: 1.556, CI [1.162, 2.084], p value <.003), higher NLR levels were associated with an amplified effect on mortality among CKD patients with anemia (Figure 4). Furthermore, there was evidence of interaction between high NLR levels and hyperuricemia on mortality among CKD patients with anemia (HR: 1.556, CI [1.162, 2.084], p value <.003, p for interaction: .048). In a sensitivity analysis aimed at assessing potential reverse causation, participants who passed away within a 24-month period of follow-up were excluded. Comparable outcomes were obtained in the Cox proportional hazards model (Supplementary Table 3). To assess whether the exclusion of samples due to missing covariates would impact the robustness of our conclusions, we conducted a separate Cox regression analysis on the excluded samples alone. Additionally, we merged these excluded samples with the included samples to perform another Cox regression analysis. The results confirmed that the conclusions remain unchanged despite the exclusion of samples (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analyses of the associations between NLR and all-cause mortality among CKD participants with anemia from the NHANES 2005–2018. NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HR: hazard ratio.

4. Discussion

This investigation delved into the impact of novel inflammatory markers, SII, NLR, as well as PLR, upon the incidence of renal anemia within individuals suffering from CKD, as well as the all-cause mortality within this group, utilizing data from the NHANES spanning 2005 to 2018. Increased SII, NLR, and PLR levels were all found to be correlated with an elevated risk of renal anemia in CKD patients, as well as the elevated level of NLR increased all-cause mortality in renal anemia population, which was aggravated by old age, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperuricemia.

CKD patients have the serologic evidence of activation of the inflammatory response, such as elevated levels of CRP and pro-inflammatory cytokine [31]. As renal function declines, the accumulation of pro-inflammatory metabolites in the body is the key cause of inflammation [11]. In addition, oxidative stress levels are augmented in CKD and can be mutually enhanced with inflammatory responses. For example, reactive oxygen species production and reactive nitrogen are promoted by toxins accumulated in CKD such as asymmetric dimethylarginine, which results in protein oxidation, DNA cleavage, and impairment of the mitochondrial electron transport cascade [32], whereas the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in peroxidized environments could promote the expression of inflammation-stimulating factors and facilitate the recruitment of inflammatory cells [33]. Moreover, the reduced intestinal barrier function in CKD patient also aggravates the level of inflammation in body. Toxins accumulated in the body are excreted from the intestinal system, disturbing the balance of the intestinal flora and leading to the overgrowth of ammonia-producing bacteria, which may increase the risk of invasion for certain bacteria and cause an inflammatory response [34, 35].

The relationship between inflammation and anemia has been confirmed across different populations. Previous studies have confirmed that SII and NLR are associated with the risk of anemia in the general population [36, 37], and in non-CKD chronic immune activation populations (such as those with rheumatoid arthritis and older cancer patients), NLR and PLR are related to the risk of anemia [38, 39]. Additionally, many studies have demonstrated that inflammation is also associated with the development and progression of renal anemia. Francisco et al. showed that high CRP level is a good predictor of poor Hb control in CKD patients [31]. Pro-inflammatory factors have been shown to affect erythropoiesis through a variety of mechanisms. Allen et al. found that pro-inflammatory factors in the serum of patients with end-stage renal disease and inflammatory diseases could inhibit the colony formation of erythropoiesis [40]. In vivo study confirmed that TNF-α can promote hypoproliferative anemia by directly affecting erythroid progenitor cells and indirectly stimulating IFN-γ production [41]. The effect of systemic inflammatory activation on iron transport is also an important factor contributing to anemia in CKD patients. Macrophages recycle iron from aging erythrocytes, which constitute approximately 90% of daily iron necessities for Hb production and erythropoiesis. Nevertheless, these cells also respond to microbial, autoantigen, or tumor antigen exposures, immune cells release a variety of inflammatory cytokines and affect iron metabolism [42]. IL-1 and IL-6 can affect iron homeostasis by influencing heparin formation and stimulating Hb synthesis [43]. Hepcidin regulates iron metabolism via binding to transmembrane iron transport proteins and leading to their degradation [44]. Elevated hepcidin levels correlate with diminished ferritin expression in duodenal epithelial cells and macrophages, alongside compromised iron uptake and storage by macrophages, as observed in animal models of inflammatory anemia and individuals with inflammatory diseases [45]. Decrease in EPO synthesis as well as activity is another causative factor of inflammatory anemia. Observational studies have shown that most patients with inflammatory anemia have lower levels of EPO than expected [13]. This may result from the fact that some of the inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-1, TNF) affect the hypoxia-mediated EPO production process by inhibiting GATA-2 and NF-κB activities or damaging renal tubular epithelial cells [46, 47]. In addition, a shortening of erythrocyte lifespan can be observed in the inflammatory. Causes include increased phagocytosis of erythrocytes by hepatic and splenic macrophages, destruction of erythrocytes by antibodies and complement, and mechanical damage to erythrocytes by fibrin deposition in the microvasculature, during inflammation [14, 15, 48]. Above studies support our findings that the level of inflammation is correlated with the risk of anemia in CKD patients, suggesting that preventing or controlling the inflammatory state within CKD patients may be a way to improve the incidence of anemia in CKD population.

NLR, PLR, and SII were initially developed by researchers to predict the prognosis of patients with tumors and severe illnesses [16–18], as they are based on counts of peripheral lymphocytes, neutrophils, and platelets, which can better reflect the balance of individual inflammatory and immune status. Due to their lower testing costs and convenient detection methods, these markers are used to predict the prognosis of various chronic inflammatory disease populations [21, 22]. Therefore, exploring their potential to predict survival outcomes in CKD patients with anemia is a worthwhile endeavor. Our research also indicates a strong correlation between elevated NLR and heightened all-cause mortality in populations with renal anemia. This increased mortality risk is attributable to inflammation, which serves as a pivotal mediator linking CKD and cardiovascular disease. Crucially, the interactions between endothelial cells and effector cells of the innate immune system are central to the initiation and progression of inflammation. CKD prompts various metabolic alterations that exacerbate the uremic milieu, leading to the accumulation of diverse uremic toxins. These toxins induce vascular damage, endothelial dysfunction, and activation of the innate immune system. The resultant endothelial dysfunction triggers oxidative stress, augments the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, and perpetuates chronic inflammation [49]. Recent research has highlighted monocyte-driven changes in CKD, which exacerbate endothelial dysfunction and thereby accelerate the progression of CKD and its associated cardiovascular diseases [50, 51]. Inflammatory state strikes the cardiovascular system of CKD patients may be an important way to influence the prognosis of CKD patients. However, unlike NLR, PLR, and SII, which use platelet count as the numerator, did not demonstrate satisfactory predictive performance in the CKD population with anemia. In cancer patients, platelets can protect circulating tumor cells from shear stress, induce epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in circulating tumor cells, and promote the extravasation of tumor cells [52, 53]. This may explain why PLR and SII perform well in predicting the prognosis of cancer patients but do not show similar effectiveness in the CKD population with anemia.

Clinical application of inflammatory factors is limited by their complex and costly detection techniques, while novel inflammatory indicators are gradually being used in clinical studies to predict the prognosis of chronic inflammatory diseases due to their ease of detection and low cost. A multicenter cohort study conducted across 39 centers in China found that NLR levels are predictive of the risk for end-phase renal disease within individuals suffering from stage 4 CKD [54]. Similarly, a meta-analysis identified NLR as a prognostic marker for all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular events within patients suffering from CKD [55]. A cohort study involving five centers in China reported that elevated SII levels independently predict higher risks of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in non-dialysis CKD patients [56]. Additionally, another study noted that each unit increase in SII is correlated to a 20.2% rise in all-cause mortality as well as a 28% increase in cardiovascular mortality among peritoneal dialysis patients [57], while our study did not observe a significant relationship between SII and mortality in renal anemia population. This may because our survival analyses were conducted using data from non-Asian populations, suggesting that the relationship between SII and patient mortality may be influenced by ethnicity.

Drawing on prior research, we focused our investigation on CKD patients who also suffered from anemia. Our findings not only established correlations between SII, NLR, as well as PLR levels and the risk of anemia development within CKD patients but also linked higher NLR levels with increased all-cause mortality within this group. These observations suggest that managing inflammation may enhance both anemia outcomes and overall prognosis in the CKD patient population. However, several limitations accompany our study. Primarily, since non-Hispanic whites predominate within the NHANES dataset, these results may not be generalizable to other racial groups, underscoring the need for further validation across diverse populations. Second, the cross-sectional nature of NHANES hinders our ability to ascertain causal relationships between novel inflammatory markers and renal anemia. Lastly, unknown confounding variables and potential biases in survey responses may also impact the study results.

5. Conclusions

This study found that in the CKD population, inflammatory markers such as NLR, PLR, and SII are associated with the risk of developing anemia. Specifically, an increase in NLR is associated with a higher risk of mortality in the CKD population with anemia. This relationship is more pronounced in subgroups with comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperuricemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank to the National Center for Health Statistics at the CDC for their excellent work in collecting the NHANES data and for making it accessible to the public.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82300831), the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (Nos. YDZJ202201ZYTS126 and 20210101259JC), and the Talent Project of Jilin Science and Technology Development (No. 20240602091RC).

Author contributions

S.F. and J.H. conceptualized the research topic and framework; Z.F. and H.W. identified the methodological details of the research; H.X. and M.W. used statistical software for data analysis; S.F. and F.M. wrote the main manuscript text; Z.X. conducted writing-review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethical approval

The CDC/NCHS Research Ethics Review Board granted approval for the detailed methods and protocols employed in the NHANES study.

Consent form

The procedures, including informed consent protocols for participants, can be accessed on the CDC.gov website. All methods adhered to the applicable guidelines and regulations. Since the data used in this study are publicly available, it was exempt from ethical review involving human subjects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data can be downloaded from the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm).

References

- 1.Huang J, Yu Y, Li H, et al. Effect of dietary protein intake on cognitive function in the elderly with chronic kidney disease: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. Ren Fail. 2023;45(2):2294147. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2294147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(7):e0158765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen E, van Galen G.. Chronic renal failure-causes, clinical findings, treatments and prognosis. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2022;38(1):25–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stauffer ME, Fan T.. Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLOS One. 2014;9(1):e84943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palaka E, Grandy S, van Haalen H, et al. The impact of CKD anaemia on patients: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes—a systematic literature review. Int J Nephrol. 2020;2020:7692376. doi: 10.1155/2020/7692376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nissenson AR, Wade S, Goodnough T, et al. Economic burden of anemia in an insured population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(7):565–574. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.7.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, Evans M, Mazhar F, et al. Poor recognition and undertreatment of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease managed in primary care. J Intern Med. 2023;294(5):628–639. doi: 10.1111/joim.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura T, Snijder R, Nozaki K.. Diagnosis patterns of CKD and anemia in the Japanese population. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(5):694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki K. Chronic inflammation as an immunological abnormality and effectiveness of exercise. Biomolecules. 2019;9(6):223. doi: 10.3390/biom9060223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez-Moreno JM, Herencia C, de Oca AM, et al. High phosphate induces a pro-inflammatory response by vascular smooth muscle cells and modulation by vitamin D derivatives. Clin Sci. 2017;131(13):1449–1463. doi: 10.1042/CS20160807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamlett L, Haragsim L.. Quotidian hemodialysis and inflammation associated with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14(3):e35–e42. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J, Li H, Yang X, et al. The relationship between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and early renal injury in population with/without hypertension: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2002. Ren Fail. 2024;46(1):2294155. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2294155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615–624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libregts SF, Gutiérrez L, de Bruin AM, et al. Chronic IFN-γ production in mice induces anemia by reducing erythrocyte life span and inhibiting erythropoiesis through an IRF-1/PU.1 axis. Blood. 2011;118(9):2578–2588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-315218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitlyng BL, Singh JA, Furne JK, et al. Use of breath carbon monoxide measurements to assess erythrocyte survival in subjects with chronic diseases. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(6):432–438. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Yang X-R, Xu Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6212–6222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith RA, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, et al. Prognosis of resected ampullary adenocarcinoma by preoperative serum CA19-9 levels and platelet–lymphocyte ratio. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(8):1422–1428. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts – rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102(1):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu K, Tang S, Liu C, et al. Systemic immune-inflammatory biomarkers (SII, NLR, PLR and LMR) linked to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease risk. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1337241. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1337241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tudurachi BS, Anghel L, Tudurachi A, et al. Assessment of inflammatory hematological ratios (NLR, PLR, MLR, LMR and monocyte/HDL–cholesterol ratio) in acute myocardial infarction and particularities in young patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(18):14378. doi: 10.3390/ijms241814378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colaneri M, Genovese C, Fassio F, et al. Prognostic significance of NLR and PLR in COVID-19: a multi-cohort validation study. Infect Dis Ther. 2024;13(5):1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s40121-024-00967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocyigit I, Eroglu E, Unal A, et al. Role of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in prediction of disease progression in patients with stage-4 chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2013;26(2):358–365. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Y, Peng B, Liu J, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2018. Front Immunol. 2022;13:975400. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization; 2024. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/85839/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf

- 25.KDIGO 2020 . Clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020;98(4s):S1–S115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lameire NH, Levin A, Kellum JA, et al. Harmonizing acute and chronic kidney disease definition and classification: report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2021;100(3):516–526. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, Xiao W, Duan Z, et al. Depression heightened the association of the systemic immune-inflammation index with all-cause mortality among osteoarthritis patient. J Affect Disord. 2024;355:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di X, Liu S, Xiang L, et al. Association between the systemic immune-inflammation index and kidney stone: a cross-sectional study of NHANES 2007–2018. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1116224. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1116224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di XP, Gao XS, Xiang LY, et al. The association of dietary intake of riboflavin and thiamine with kidney stone: a cross-sectional survey of NHANES 2007–2018. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):964. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. Association of dietary inflammatory index with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in hyperuricemia population: a cohort study from NHANES 2001 to 2010. Medicine. 2023;102(51):e36300. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000036300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Francisco AL, Stenvinkel P, Vaulont S.. Inflammation and its impact on anaemia in chronic kidney disease: from haemoglobin variability to hyporesponsiveness. NDT Plus. 2009;2(Suppl. 1):i18–i26. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Muneer PM, Chandra N, Haorah J.. Interactions of oxidative stress and neurovascular inflammation in the pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51(3):966–979. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duni A, Liakopoulos V, Roumeliotis S, et al. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and evolution of chronic kidney disease: untangling Ariadne’s thread. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3711. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cobo G, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P.. Chronic inflammation in end-stage renal disease and dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(Suppl. 3):iii35–iii40. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mihai S, Codrici E, Popescu ID, et al. Inflammation-related mechanisms in chronic kidney disease prediction, progression, and outcome. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2180373. doi: 10.1155/2018/2180373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, Xiao J, Cai W, et al. Association of the systemic immune-inflammation index with anemia: a population-based study. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1391573. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1391573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alshuweishi Y, Alfaifi M, Almoghrabi Y, et al. A retrospective analysis of the association of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) with anemia in the Saudi population. Medicina. 2023;59(9):1592. doi: 10.3390/medicina59091592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Z, Shao H, Liu H, et al. Anemia in elderly rheumatoid arthritis patients: a cohort study. Arch Med Sci. 2024;20(2):457–463. doi: 10.5114/aoms/172443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Huang J-X, Tang M, et al. A comprehensive analysis of the association between anemia and systemic inflammation in older patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2023;32(1):39. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-08247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen DA, Breen C, Yaqoob MM, et al. Inhibition of CFU-E colony formation in uremic patients with inflammatory disease: role of IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. J Investig Med. 1999;47(5):204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goicoechea M, Martin J, de Sequera P, et al. Role of cytokines in the response to erythropoietin in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54(4):1337–1343. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prakash J, Raja R, Mishra RN, et al. High prevalence of malnutrition and inflammation in undialyzed patients with chronic renal failure in developing countries: a single center experience from eastern India. Ren Fail. 2007;29(7):811–816. doi: 10.1080/08860220701573491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canali S, Core AB, Zumbrennen-Bullough KB, et al. Activin B induces noncanonical SMAD1/5/8 signaling via BMP type I receptors in hepatocytes: evidence for a role in hepcidin induction by inflammation in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(3):1146–1162. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Theurl I, Aigner E, Theurl M, et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis in anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency anemia: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Blood. 2009;113(21):5277–5286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.La Ferla K, Reimann C, Jelkmann W, et al. Inhibition of erythropoietin gene expression signaling involves the transcription factors GATA-2 and NF-kappaB. FASEB J. 2002;16(13):1811–1813. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0168fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jelkmann W. Regulation of erythropoietin production. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 6):1251–1258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moldawer LL, Marano MA, Wei H, et al. Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor-alpha alters red blood cell kinetics and induces anemia in vivo. FASEB J. 1989;3(5):1637–1643. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.5.2784116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: from mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(3):924–967. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.120.000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heine GH, Ortiz A, Massy ZA, et al. Monocyte subpopulations and cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(6):362–369. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogacev KS, Zawada AM, Emrich I, et al. Lower Apo A-I and lower HDL-C levels are associated with higher intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocyte counts that predict cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(9):2120–2127. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Placke T, Salih HR, Kopp HG.. GITR ligand provided by thrombopoietic cells inhibits NK cell antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2012;189(1):154–160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO.. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial–mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan Q, Wang J, Peng Z, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and incident end-stage renal disease in Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease: results from the Chinese Cohort Study of Chronic Kidney Disease (C-STRIDE). J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao WM, Tao SM, Liu GL.. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in relation to the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):1059–1066. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2020.1832521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai W, Xie Y, Zhao X, et al. Elevated systemic immune inflammation level increases the risk of total and cause-specific mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease: a large multi-center longitudinal study. Inflamm Res. 2023;72(1):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00011-022-01659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li G, Yu J, Jiang S, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index was significantly associated with all-cause and cardiovascular-specific mortalities in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:3871–3878. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S426961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data can be downloaded from the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm).