Abstract

In a bushfire burning of plant material generates volatile phenolics that may be absorbed by berries and leaves of grapes in nearby vineyards. In grapes these phenolics form glycoconjugates and the undesirable sensory attributes of smoke-exposed grapes only develop post-fermentation in the wine making process, when the free phenolics are released. To reduce the financial losses from producing smoke-tainted wines, phenolic glycosides associated with smoke-taint in grapes are currently monitored in analytical laboratories. Here, we performed LC-MS analysis on extracts of diverse grape varieties of various geographic sites and with varying levels of smoke taint exposure. Discovery of smoke-taint biomarkers, based on untargeted analysis led to the identification of additional phenolic compounds that could contribute significantly to the smoke-tainted flavour of wine. A total of 73 differentially expressed metabolites were detected and LCMSMS analysis resulted in the structural assignment of 15 compounds, including guaiacol and syringol derivatives and novel glycoconguate intermediaries.

Keywords: Phenolic glycosides, LC-MS, Guaiacol, Syringol

Highlights

-

•

73 metabolite associated with various levels of smoke taint were detected in grapes of diverse varieties and geographic sites.

-

•

Discovery of additional phenolic compounds could contribute to the smoke-tainted flavour of wine and serve as smoke-taint biomarkers.

-

•

Guaiacol and syringol derivatives as well as unknown glycoconguate intermediaries were identified.

1. Introduction

In a bushfire burning of plant material generates volatile phenolics that may be absorbed by berries and leaves of grapes in nearby vineyards. In grapes these phenolics form glycoconjugates that do not contribute negatively to the flavour. The undesirable sensory attributes of smoke-exposed grapes only develop post-fermentation in the wine making process, when it is believed free phenolics are released. The breakdown of phenol glycoconjugates via enzymes and acid catalysed hydrolysis have previously been demonstrated (Kennison, Gibberd, Pollnitz, & Wilkinson, 2008; Skouroumounis & Sefton, 2000; Wilkinson, Elsey, Prager, Tanaka, & Sefton, 2004; Wirth, Guo, Baumes, & Günata, 2001). The level at which grapes and wine have been affected by smoke has been analysed by mainly GCMS methods via measurement of guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol that typically form by the burning of lignin, one of the main constituents of wood or bark (Maga, 1989). The presence of these conjugated precursors can pose a problem. However, to reduce the financial losses from producing smoke-tainted wines, phenol glycosides associated with smoke-taint in grapes are monitored in analytical laboratories using analytical methods that either directly measure glycoconjugates using LCMSMS or indirectly via acid hydrolysis for GCMS (Favell et al., 2022; Wilkinson et al., 2011). However, there could many different phenol glycoconjugates and analogues present in smoke-tainted berries and there are only a limited sets of standards (Favell et al., 2022).

Studies on the effect of smoke on varieties Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc indicated that development stage or timing of smoke uptake varies with variety that may be associated with berry skin thickness, seasonal conditions and vine health (Brodison, 2013). Jiang et al. showed that despite varietal differences in Chardonnay and Shiraz, phenol glycosides compared to volatile phenols are a better indicator of smoke exposure in berries, with uptake and glycosylation of phenols being consistent across timepoints in ripening season (Jiang, Parker, Hayasaka, Simos, & Herderich, 2021). Phenolic glycosides were also found in leaves and were identified as potential biomarkers for smoke exposure of vines. Comparing two varieties, Shiraz showed higher levels of phenolic glycosides compared to Chardonnay, owing to the compositional differences in varieties. The presence of guaiacol and 4-vinylguaiacol are also present in wines that are aged in oak wood barrels and are known to contribute to the smoky aroma from the ageing process, and an indicator of the relative toast level of the oak chips (Chatonnet & Boidron, 1988; Dumitriu Gabur et al., 2019; Pollnitz, Pardon, & Sefton, 2000). The compounds can also be produced by enzymatic or thermal degradation of cinnamic acid (Zoecklein, Fugelsang, Gump, & Nury, 2013).Guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, syringol (2,6-dimethoxyphenol), methyl syringol, phenols, o-, p- and m-cresols, are also regarded as the most abundant in wood smoke and important biomarkers for smoke exposure in grapes (Hayasaka et al., 2010). Guaiacol, 4-methyl guaiacol and related compounds were described as smoky and typically positively correlate to the smoke-related sensory attributes in wines produced from smoke-exposed wines and have a low aroma and sensory threshold, suggesting they are likely involved in the smoke flavour (Kennison, Wilkinson, Pollnitz, Williams, & Gibberd, 2009). Yet, studies have shown that smoke-like aromas were present at various levels in wines with concentrations below aroma- thresholds for guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, and 4-ethylguaiacol, in a single smoke exposure experiment regardless of smoke application timing (Kennison et al., 2009). Studies carried out by Parker et al., 2012 (Parker et al., 2012), indicated that low smoke-aroma thresholds for phenols, cresols (o-, m-, and p-isomers), especially m-cresol to the smoke-related sensory properties and the low contribution of 4-methylsyringol and syringol that possessed a high sensory threshold are unlikely an individual contributor to flavour, but more likely to cause an enhanced effect of the more sensitive smoke-aroma volatile phenols.

Apart from the additional volatile phenolics (VPs) concentrating in grapes originating from smoke exposure, secondary metabolite signaling pathways are induced, as observed under abiotic stress conditions in plants (Noestheden, Noyovitz, Riordan-Short, Dennis, & Zandberg, 2018). Using novel extraction methods, untargeted analysis (based on LCMS) was performed on extracts of diverse grape varieties, with various levels of smoke taint (none, low, medium, high or very high) to assess for common biomarkers associated with smoke-taint in wine across different geographic locations and grape varieties as well as functional metabolites associated with abiotic stress responses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Grape samples

Red skinned grapes and white grapes with different levels of smoke exposure were collected at the post-veraison stage from various vineyards across the state of Victoria, Australia (Supplementary Fig. 1) after bush fires that occurred between December 2019 and January 2020. The bunches were collect from different rows of the affected vineyard and from different locations within the rows (i.e. end and internal sampling). For each variety and site a random subset of grapes (10 g) were combined to make a pooled representative sample. The samples were kept at −20 °C before analysis. (See Table 1.)

Table 1.

Number of bunches collected by location, grape variety and level of smoke in vineyards.

| Location | Variety Smoke Level | Chardonnay | Sangiovese | Shiraz | Prosecco | Pinot Grigio | Viognier | Pinot Noir | Sauvignon Blanc | Riesling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geelong | none | 10 | NA | 10 | NA | 10 | NA | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Murray Darling | none | 10 | NA | 10 | 10 | 10 | NA | 10 | 10 | NA |

| Rutherglen 1 | medium | 10 | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rutherglen 2 | high | NA | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | 10 | NA | NA | NA |

| King Valley | very high | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10 | NA | NA |

| Alpine Valley | very high | 10 | 10 | NA | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Smoke level is defined by a Smoke Rating formula which was developed around the following criteria:

-

•

Low = low exposure to bushfire smoke in region and vineyard i.e. some smoke was visible however it was considered low smoke drift from a bushfire between 0 and 200 km distance from sample location.

-

•

Medium = minimal exposure to bushfire smoke in region and vineyard i.e. smoke was visible in the region and vineyard with smoke drift from a bushfire between 0 and 100 km distance from sample location.

-

•

High = high level of exposure to bushfire smoke in region and vineyard i.e. smoke was visible and sustained within a region and vineyard with smoke drift from a bushfire <50 km distance from sample location.

-

•

Very High = very high level of exposure to intense bushfire smoke in region and vineyard i.e. smoke was visible and sustained within a region and vineyard, with smoke drift from a bushfire <25 km distance from sample location.

For each region and sample vineyard tested, there was an assessment made based on these conditions and in consultation with the vineyard manager and an industry consultant / winemaker with experience in smoke taint research, detection and impact. This assessment was supported by taking a sample from these regions and vineyards for commercially testing, in addition to individual vineyards own sensory and winemaking sample ferments.

2.2. Extraction of free and glycosylated phenols from grapes

Samples were extracted as described in Zhiqian et al. (Liu et al., 2020). A total of 10 g of randomly selected de-stemmed berries were homogenized in a 50-mL polypropylene falcon tube using a tissue grinder, and then 4 mL of water was added to the homogenate and thoroughly mixed by vortex for 2 min. The samples were centrifuged for 15 min (5000 g) and the supernatant was transferred to a new 15-mL tube and the volume adjusted to 10 mL with water.

2.3. LC-MS for Untargeted Analysis and LCMSMS methods

Untargeted metabolite profiling was performed on the 84 berry extracts using a Vanquish ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) with a binary pump, autosampler and temperature-controlled column compartment, coupled with a QExactive (QE) Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo, Bremen, Germany) with electrospray (ESI) probe operating in both positive and negative modes. For MS data acquisition, positive and negative ion data were captured over a mass range of 80–1200 m/z, with a mass resolution set at 35,000. Nitrogen was used as the sheath, auxiliary and sweep gases at flow rates of 28, 15 and 4 units, respectively. Spray voltage was set at 3600 V (positive and negative). Sample injection volume was 3 μL and autosampler temperature set to room temperature to avoid formation of sugar crystals. Samples were randomised, and blanks (80% methanol) injected every five samples. A pooled biological quality control (PBQC) was run every 10 samples.

For identification of the 73 compounds targeted analysis was performed, using MS2 and MS3 fragmentation analysis using a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap Velos ion trap MS system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Bremen, Germany), with a heated electrospray ionisation (ESI) source. Data-dependent MS2 and MS3 spectra was acquired on target ions and selected samples with normalised collision energy of 35 V and an ion max time of 50 microseconds. Source heater temperature was maintained at 310 °C and the heated capillary was maintained at 275 °C. The sheath, auxiliary and sweep gases was 28, 15 and 4 units respectively, for ESI- mode. Spray voltage was set at 3600 V (negative). Sample injection volumes was 5 μL.

Prior to data acquisition, all systems were calibrated with Pierce LTQ Velos ESI Positive and Negative Ion Calibration Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mass spectrometry data were acquired using Thermo Xcalibur V. 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

A Thermo Fisher Scientific Hypersil Gold 1.9 μm, 100 mm × 2.1 mm column with a gradient mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid in H2O (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min was used. The gradient began at 2% B, increasing to 100% B over 11 min; followed by 4 min at 100% B before a 5 min equilibration with 2% B.

2.4. Data Processing and Statistical Analyses

The data files obtained following LCMS analyses were processed in the Refiner MS module of Genedata Expressionist® 12.0 with the following parameters: 1) chromatogram chemical noise subtraction with removal of peaks with <4 scans, chromatogram smoothing using moving average estimator over 5 scans, and 70% quantile over 151 scans for noise subtraction, 2) intensity thresholding using a clipping method and a threshold of 10,000, 3) selection of negative mode data only, 4) chromatogram RT alignment using a pairwise alignment based tree and a maximum RT shift of 2 min, 5) chromatogram peak detection using a 5 scans summation window, a minimum peak size of 0.1 min, a maximum merge distance of 0.05 Da, a boundary merge strategy, a maximum gap/peak ratio of 70% with moving average smoothing over 10 scans for peak RT splitting 6) chromatogram isotope clustering using RT and m/z tolerance of 0.05 min and 0.05 Da respectively with a maximum charge of 2, 7) adduct detection using mainly M-H and allowable adducts (M + FA-H).

Statistical analyses were performed using the Analyst module of Genedata Expressionist® 12.0. Principal component analyses (PCA) were performed to identify tissue and treatment differences. Overlay of the PBQC and samples allowed for the validation of the high-quality dataset by ensuring that RT variation, mass error and sensitivity changes throughout the run were consistent. In this study, the BH (Benjamini Hochberg)-adjusted p-values were reported (q < 0.01) using linear regression, with metabolite (y) response predicting smoke-taint rating (y ∼ smoke-taint rating).

PLSDA modelling was carried out using PLSToolbox (ver 8.8.1 Eigenvector Research, Inc.) running on MatLab (ver R2018a, MathWorks). The LCMS intensity data for the 73 metabolites and 84 samples was normalised using log10 and mean center.

Model evaluation was performed using the true positive rate (sensitivity) [(Eq. (2)) with the metrics TP (true positive) and FN (false negative)] and the true negative rate (specificity) [(Eq. (3)), with the metrics TN (true negative) and FP (false positive)]. The true positive rate (sensitivity) and true negative rate (specificity) are used to then determine the classification error (CE) (Eq. (4)), which is equivalent to the average of the false positive rate and false negative rate.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Cross validation (CV) was performed for all models, using Venetian blinds by applying 10 data splits, with one sample per blind used to assess individual models and to select the optimum number of LVs in PLS-DA. Permutation testing was performed using Random t-test using both self-prediction and cross validation.

Identification of metabolites was performed by searching experimental MS1 data through the following databases: Plant Metabolic Network (PMN) https://plantcyc.org (accessed on 23 June 2022); Human Metabolome DataBase (HMDB) (http://hmdb.ca) (accessed on 10 June 2022); ChemSpider (http://chemspider.com) (accessed on 13 June 2022); and Lipid Maps® (http://www.lipidmaps.org) (accessed on 20 June 2022). MS2 data were searched on MzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org) (accessed on 30 June 2022). The MS2 data were analysed for common structural fragments of guaiacol, syringol, cresol, phenol and vanillin (Fig. 1) with a 5 ppm tolerance of (M-H]− was utilized using Thermo Xcalibur V. 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Smoke-taint ions, guaiacol, syringol, cresol and phenol as well as related structural derivatives.

3. Results

To investigate metabolites associated with smoke-tainted grapes, a variety of grapes exposed to different levels of smoke were collected at the post-veraison stage after bush fires. These samples were extracted and analysed using negative electrospray ionisation- ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry (ESI- UHPLC-HRMS).

Evaluation of the metabolomic data revealed a total of 5791 compounds in negative ionisation mode. Putative identification of 2030 metabolites in negative mode, provided valuable information on the complex composition of the smoke-tainted grapes, including flavanols, phenols, sugars, plant hormones and amino acids.

Prior to statistical analysis of ESI- UHPLC-HRMS results, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots were generated on the full dataset, which includes the 5791 features identified in negative ionisation mode. The reproducibility of the PBQC samples as represented in the PCA plots indicated that no corrections were required (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) scores plot showing smoke taint grape samples categorized by variety A) ‘Pinot Noir’ (n = 12), Shiraz (n = 18), Pinot Grigio (n = 15), Chardonnay (n = 18), Sangiovese (n = 9), Viognier (n = 3), Prosecco (n = 3), Riesling (n = 3), Sauvignon Blanc (n = 3); and region B) Murray Darling (n = 12), Rutherglen (n = 27), Alpine Valleys (n = 21), King Valley (n = 6), Geelong (n = 18) C) Control (STCon; n = 30), Mid-High (STMid; n = 21), High (STHigh; n = 21), Very High (STVHigh; n = 12). Sample extracts were evaluated on ESI- UHPLC-HRMS with a PBQC.

The smoke-rating was determined using a smoke-distance-intensity metric employed by local vineyards and supported by our in-house GC–MS method and external laboratories (Liu et al., 2020). Untargeted profiling of UHPLC-HRMS was performed and metabolites were selected based on low or missing values in the control and with a 2-fold increase in the grapes with a smoke-taint rating of mid, high and very high. Significance analysis was also applied using linear regression, with metabolite (y) in response to smoke rating (control = 0; mid = 1; high =2; very high =3) (y ∼ smoke-taint rating). The Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) correction was used to adjust the significance (p value) of each variable and adjusted p-values were reported as q-values. Compounds that were significant but appeared in only certain regions and not others were removed as they were not considered as helpful biomarkers of smoke taint and most likely site specific. However, some smoke related compounds showed high effect sizes between treatments, but a disproportionate increase in the mid and high smoke exposed grapes, likely due to an overlap in sample classification (mid-high and high-very high), but as they also had a high effect size, were still included for analysis, despite linear model results showing P values >0.05. The criterion led to the identification of 73 compounds that could either be exogeneous smoke-related metabolites or a biochemical response of the plant to smoke exposure.

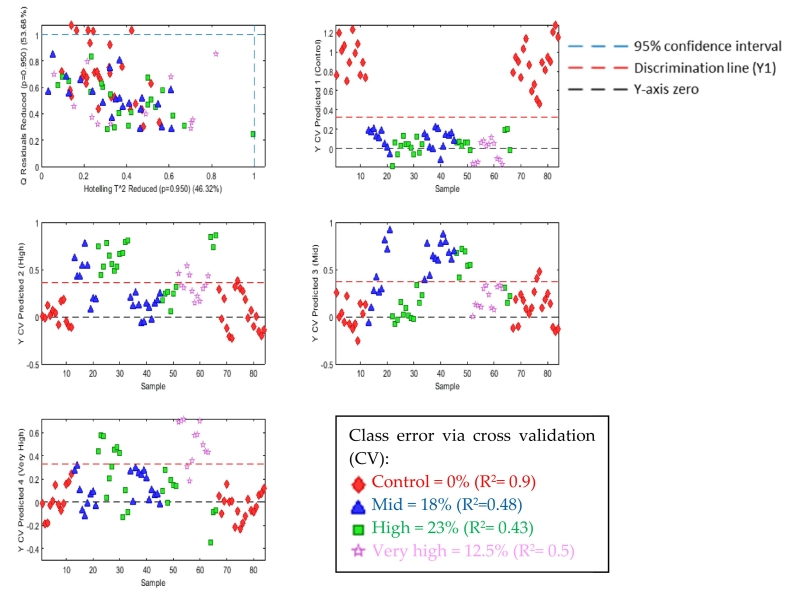

3.1. Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of ESI-UHPLC-HRMS

PLS-DA calibration model was generated on the 73 selected metabolites (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) The model separated the control from smoke-taint samples using three latent variables returning a class error via cross validation (CV) of 0%, 23%, 18% and 12.5% for control, high, mid, and very high respectively (Fig. 3). The overlap in the mid-high-very high smoke-tainted grape samples are as expected due to the variability in the exposure of samples and their relative geographic location.

Fig. 3.

PLS-DA model discriminating control (red diamonds), mid (blue triangles), high (green squares) and very high (pink stars) smoke-tainted grapes. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

A new model was created with two groups control vs smoke-taint (very high, high and mid) using two latent variables. The class error via CV was found to be 0% with a R2 CV of 0.89. Permutation test (50 iterations) showed the model was not overfitted (p < 0.005).

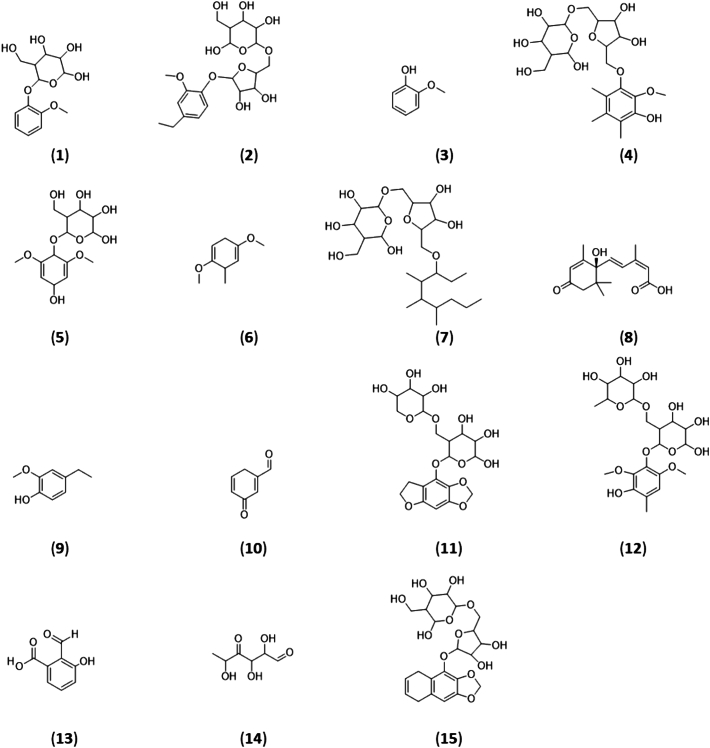

3.2. Metabolite Identification

To confirm identity of the compounds, targeted MS2 and MS3 was performed on the 73 analytes (Supplementary data 1). The individual analytes were examined and compared to common fragments associated with structures guaiacol, syringol, cresol, eugenol, phenol and vanillin (van der Hulst et al., 2019) and fragmentation data searched in libraries. Identification of 15 of the 73 significant metabolites was deduced using either MS or MSn fragmentation of the parent ion (Table 2 and Fig. 4). The level of confidence for metabolite identification was as defined by Schymanski (Schymanski et al., 2014) which was a proposed revision from the first guidelines of the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) where the level of identification was difficult to determine for compounds (Creek et al., 2014; Schrimpe-Rutledge, Codreanu, Sherrod, & McLean, 2016; Schymanski et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Metabolites identified in UHPLC-HRMS ESI- data that were used to generate a PLSDA model between control compared to smoke-tainted grapes (very high, high, mid-high) revealing their VIP scores and their associated effect size. Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p values (Q-values) indicated that 13 of these metabolites are significant (Q < 0.05) in the linear model (y ∼ smoketaint rating) (control = 0; mid = 1; high =2; very high =3).

| Ion | Compound name | m/z | RT | Molecular Formula | Mass Delta [ppm |

Q-Value (BH Adjusted p Value) |

Effect size | VIP | MS2, MS3 Ions | Metabolite identification level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | guaiacol glycoside | 285.0980 | 4.24 | C13H18O7 | 3.86 | 4.62 × 10−10 | 10.94 | 3.23 | 123.0451 | 1 |

| 2 | ethyl guaiacol pentosylglycoside | 445.1719 | 5.29 | C20H30O11 | 3.37 | 4.92 × 10−5 | 5.00 | 2.79 | 151.0763, 293.0876, 233.0665, 191.0561 | 2 |

| 3 | guaiacol | 123.0440 | 4.24 | C7H8O2 | −0.81 | 1.92 × 10−1 | 4.00 | 1.91 | 82.0424 | 2 |

| 4 | tri methyl/propyl/methyl ethyl guaiacol pentosyl glucoside | 489.1982 | 5.60 | C22H34O12 | 3.07 | 5.64 × 10−22 | 4.00 | 0.62 | 443.1920, 293.0876, 263.0777 | 2 |

| 5 | syringol derivative I | 333.1192 | 3.13 | C14H22O9 | 3.30 | 6.71 × 10−17 | 3.52 | 0.57 | 153.0557, 179.0561 | 2 |

| 6 | syringol derivative II | 153.0910 | 5.95 | C9H14O2 | 0.00 | 2.43 × 10−5 | 3.50 | 0.46 | 138.0686, 97.0294, 109.0294 | 2 |

| 7 | Alkyl pentosylglucoside | 493.3021 | 5.81 | C24H46O10 | 2.84 | 1.14 × 10−2 | 3.44 | 0.45 | 475.2909, 447.2237, 331.2489, 313.2378, 295.2276 | 3 |

| 8 | abscisic acid | 263.1289 | 5.95 | C15H20O4 | 4.18 | 4.29 × 10−5 | 3.32 | 0.44 | 153.0922, 138.0689 | 2 |

| 9 | ethyl guaiacol | 151.0755 | 5.95 | C9H12O2 | 0.66 | 1.08 × 10−4 | 3.24 | 0.43 | 107.0138 | 2 |

| 10 | oxocyclohexadiene carbaldehyde | 121.0283 | 4.11 | C7H6O2 | −0.82 | 4.54 × 10−12 | 2.97 | 0.41 | 94.0424 | 2 |

| 11 | phenolic rutinoside (derivative of syringol) | 473.1300 | 4.23 | C20H26O13 | 2.11 | 4.86 × 10−8 | 2.94 | 1.74 | 427.1610, 293.0876, 292.0560 | 2 |

| 12 | methoxy methyl dihydrobenzodioxolol rutinoside | 491.1780 | 4.43 | C21H32O13 | 4.28 | 7.02 × 10−8 | 2.70 | 0.37 | 445.1712, 307.1033, 163.0612 | 2 |

| 13 | formyl hydroxybenzoic acid | 165.0184 | 4.11 | C8H6O4 | 1.21 | 3.31 × 10−12 | 2.49 | 0.35 | 150.0321, 137.0245, 121.0295 | 2 |

| 14 | monosaccharide | 161.0451 | 2.88 | C6H10O5 | 4.35 | 3.48 × 10−1 | 2.40 | 0.39 | 143.0348, 101.0244 | 2 |

| 15 | dihydronapthol dioxolol pentosylglucoside | 483.1508 | 4.85 | C22H28O12 | 2.28 | 8.41 × 10−5 | 1.53 | 0.19 | 437.1444, 293.0872, 191.0561, 149.0453 | 2 |

Fig. 4.

The proposed structures of 15 compounds identified as significantly increased in grape varieties exposed to various levels of smoke.

Of the 73 compounds, a unique feature was inferred for 58 compounds (Level 4) using feature extraction via isotope clustering methods, but due to insufficient data no probable structure could be deduced. Of the 15 remaining structures, compound (7) was assigned a tentative structure (Level 3) due to limited structural possibilities based on the RT and MS2 data evidence; however, no literature or database could support the proposed structure. Based on library spectrum match, RT and MS2 diagnostic fragments, a probable structure was inferred for 13 metabolites (Level 2). Compound (1) was assigned Level 1 identification based on availability of in-house reference standard and MS, MS/MS and RT matching under identical experimental conditions.

Guaiacol (3) co-eluted with guaiacol glycoside at 4.24 min (m/z 123.0451) and MS2 fragmentation of the aromatic structure and subsequent demethoxylation resulted in the ion m/z 82.0424 which matched with our in-house standard. The guaiacol glycosides and related derivatives include structures (1), (2) and (9). Guaiacol glycoside (1) eluted at 4.24 min (M - H]-, m/z 285.0980) and the MS2 spectrum gave rise to the intense guaiacol ion m/z 123.0451 indicating a loss of the sugar moiety. Ethyl guaiacol pentosyl glycoside (2) eluted at 5.29 min (M - H]-, m/z 445.1719) and the MS2 fragmentation led to the intense ethyl guaiacol ion m/z 151.0763 and the loss of the sugar moiety (m/z 293.0876) [14]. The partial loss of the pentosyl glycoside (m/z 233.0665) and loss of O-methyl glucose and subsequent dehydrogenation (m/z 191.0561) confirmed the configuration of the sugar molecule. The less polar ethyl guaiacol (9) eluted slightly later to its glycoside at 5.95 min (M - H]-, m/z 151.0755) and the ions m/z 124.0402 and m/z 107.0138 indicated loss of the ethyl group and subsequent loss of methyl respectively.

The syringol related compounds include structures (5) and (6). The syringol derivative I (5) eluted at 3.13 min (M - H]-, m/z 333.1191) and MS2 fragmentation resulted in the syringol ion (m/z 153.0557) due to loss of hydroxy and the glucose moiety with a corresponding ion at m/z 179.0554. Syringol derivative II (6), eluted at 5.95 min (M - H]-, m/z 153.0910) and the MS2 spectra indicated subsequent loss of methyl groups, giving rise to the intense ion m/z 138.0686, followed by m/z 109.0295 and further fragmentation of the aromatic ring (m/z 97.0294).

Novel glycoconguate intermediaries of the VPs include (4), (11), (12), (15). The compound (4) eluted at 5.60 min (M - H]-, m/z 489.1982) and MS2 fragmentation resulted in a simultaneous de-hydroxylation and de-methoxylation (m/z 443.1920) of the phenolic intermediate ion, likely due to hydrogen bonding. Further MS3 fragmentation on m/z 443.1920 led to loss of the pentosyl glucoside molecule (m/z 293.0876) and also partial loss of the glucose molecule (m/z 311.1505) and the pentosyl glucoside molecule (m/z 263.0777). Compound (11) eluted at 4.23 min (M - H]-, m/z 473.1300) and MS2 fragmentation of the benzodioxolol moiety resulted in loss of the O-CH2-O group (m/z 427.1610) and further fragmentation led to loss of the rutinoside (arabinosyl) molecule (m/z 293.0876). MS3 of the m/z 427.1610 gave rise to m/z 292.0560 indicating glucose attached to the dihydrobenzofuranol, further supporting the presence of a rutinoside. The compound (12) eluted at 4.43 min (M - H]-, m/z 491.1780) and MS2 fragmentation led to simultaneous de-hydroxylation and -methoxylation resulting in the methylguaiacol rutinoside (rhamnosyl) ion (m/z 445.1712). Loss of the disaccharide molecule (m/z 307.1033) and the glucosyl group (m/z 163.0612) was also detected. Compound (15) eluted at 4.85 min (M - H]-, m/z 483.1508) and MS2 fragmentation of the benzodioxolol moiety resulted in loss of the O-CH2-O group (m/z 437.1444). Loss of the pentosyl glucoside ion (m/z 293.0872), glucosyl group (m/z 191.0561) and partial fragmentation of glucose molecule (m/z 149.0453) was also detected.

Lignin pyrolysis can lead to the production of a wide range of compounds and some of these structural variations include (7), (10), (13), (14). The alkyl pentosylglucoside (7) eluted at 2.84 min (M - H]-, m/z 493.3021). Dehydroxylation (m/z 475.2909) and loss of -CH2-CH2-CH3 and dehydrogenation (m/z 447.2237) was detected as well as fragmentation and loss of glucosyl group (m/z 331.2489 and 313.2378), and subsequent dehydroxylation (m/z 295.2276). The hydroxybenzaldehyde (10) eluted at 4.11 min (M - H]-, m/z 121.0283) and fragmentation resulted in the phenolic ion (m/z 94.0424). Formyl hydroxybenzoic acid (13) also eluted at 4.11 min (M - H]-, m/z 165.0184). Fragment ions include dehydroxylation (m/z 150.0321), deformylation (m/z 137.0245) and decarboxylation (m/z 121.0295) which matched with isophthalic acid fragment on m/z cloud database. The monosaccharide (14) eluted at 2.88 min (M - H]-, m/z 161.0451) and structural fragments include dehydroxylation (m/z 143.0348) and loss of C2H2O2 moiety (m/z 101.0244) [14].

The plant hormone abscisic acid (8) eluted at 5.95 min (M - H]-, m/z 263.1289) MS2 fragment ion m/z 153.0922 and MS3 of the ion led to m/z 138.0689. Both ions matched the spectral database m/z cloud.

Although only 15 of the 73 metabolites have structural information, compounds could be useful biomarkers for assessing smoke-tainted grapes.

4. Discussion

This study investigated metabolites associated with smoke taint using ESI- LCMS metabolite profiling on extracts of diverse grape varieties, with known levels of smoke taint (none, low, medium, high or very high). PLSDA modelling revealed that there were important biomarkers associated with smoke-taint levels in bush fire exposed grapes.

Our results show that the smoke-tainted berries showed marked increases in guaiacol derivatives and its glycoconjugates in relation to smoke exposure. Guaiacol is a common lignin degradation product and occurs naturally in the fruit and leaves of grape varieties, providing a subtle contribution to the flavour and aroma of wine (Singh et al., 2011), and at high levels are associated with smoke-aroma and an ashy aftertaste (Kennison et al., 2008; Kennison, Wilkinson, Williams, Smith, & Gibberd, 2007; Parker et al., 2012). Although, syringols were not a major contributor to the model, in fact only two syringol derivatives was identified, the high sensory threshold of these compounds make it an unlikely contributor to high-smoke tainted wine. Syringols are reported to only enhance or provide an additive effect to the smoke-tainted flavours (Parker et al., 2012).

The composition of wood smoke is one that is complex with wide-ranging volatile organic carbons (VOCs), including various forms, substitutions and derivatives of alkanes and aromatics (Naeher et al., 2007). In this study, increased levels of alkyl glycoside, monosaccharide and carbaldehyde were identified in smoke-tainted grapes, consistent across nine grape varieties and five geographic origins. Given the diverse composition of smoke, these metabolites could be smoke-related rather than induced by a plant response to exogenous stress; however, further studies would be required to understand the biochemical response of grapes to smoke exposure.

Four unknown phenol metabolites bearing structural resemblance to phenol metabolites, associated with smoke-taint for e.g. guaiacol and syringol, were identified. Previous studies have indicated that there are likely intermediaries or derivatives of the smoke-taint related volatile phenols present in grapes that could influence sensory characteristics (van der Hulst et al., 2019). During grapevine exposure to smoke subsequent in vivo glycosylation allows the rapid uptake of volatile phenols, and previous studies have indicated that variation in gene expression of glucosyltransferases in varieties could be responsible for the different glycoconjugate profiles. In our study, variety and site-specific metabolites were removed, for the identification of common metabolites of smoke taint.

It is not unexpected that there is increased levels of abscisic acid (ABA) production in smoke-tainted grapes. ABA has been reported to be a key signaling molecule in response to grapevine abiotic stress for e.g. water deficits and light stress and is also linked to secondary metabolite production such as phenolic compounds and VOC's (e.g. terpenes and oxygenated hydrocarbons) in response to environmental stress (Ferrandino & Lovisolo, 2014).

In the present study, further work will be required to identify the structures of the remaining 58 compounds to investigate their contribution to smoke-tainted wine. While the biomarkers identified in this study are promising for future assessment of smoke-tainted grapes, semi-targeted quantitation is only possible for many of the unique compounds, as they are not commercially available.

The use of LCMSMS as a direct measure of phenolic glycoconjugates to accurately monitor smoke-taint levels for routine testing in vineyards is important, however not all are representative of the geographic location and variety. Here, we discover 73 biomarkers of smoke-tainted grapes collected from vineyards of various geographic location and grape variety, with the structural assignment of 15, including 4 novel glycoconjugates of the common volatile phenolic derivatives (syringol and guaiacol) and 4 unique metabolites associated with lignin pyrolysis. Moreover, the identification of increased levels of ABA indicate that not all compounds identified are exogenous and some may be linked to physiological effects of the plant in response to stress induced by smoke exposure. The identification of known smoke-related biomarkers including mainly guaiacol and syringol derivatives, is consistent with previous studies, however, the identification of their novel glycoconguate intermediaries and the unique lignin pyrolysates is an important addition to the suite of metabolites routinely tested in grapes by analytical laboratories prior to the wine making process. Further studies into the identification of unknown metabolites and their contribution to sensory characteristics is required.

Author contributions

S.R., P.R., G.S. conceptualised, supervised and resourced the research; P.R., Z.L, V.E. carried out main experiments; S.R., P.R., K.F., and G.S. undertook writing, editing and review of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agriculture Victoria Research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Simone Rochfort: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Priyanka Reddy: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Krishni Fernanado: Formal analysis. Zhiqian Liu: Investigation, Methodology. Vilnis Ezernieks: Investigation, Methodology. German Spangenberg: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Priyanka Reddy reports article publishing charges was provided by Agriculture Victoria. Priyanka Reddy reports a relationship with Agriculture Victoria that includes: employment. There are no conflicts of interest. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the generosity of the grape growers who provided samples and access to their vineyards.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101665.

Contributor Information

Simone Rochfort, Email: simone.rochfort@agriculture.vic.gov.au.

Priyanka Reddy, Email: priyanka.reddy@agriculture.vic.gov.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Summary of identified metabolites that significantly increased in smoke-tainted grapes.

Map of Victoria showing collection sites for grapes in 2020. (Map by Wayne Harvey, Agriculture Victoria Research, Epsom, 12/3/2020.) B) In field scanning of grapes.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Brodison, K. (2013), Effect of smoke in grape and wine production. Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, Perth. Bulletin 4847, 8-10. https://library.dpird.wa.gov.au/bulletins/203.

- Chatonnet P., Boidron J.N. Dosages de phénols volatils dans les vins par chromatographie en phase gazeuse. Sciences des Aliments. 1988;8:479–488. [Google Scholar]

- Creek D.J., Dunn W.B., Fiehn O., Griffin J.L., Hall R.D., Lei Z., Wolfender J.L. Metabolite identification: Are you sure? And how do your peers gauge your confidence? Metabolomics. 2014;10(3):350–353. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0656-8. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84907095098&doi=10.1007%2fs11306-014-0656-8&partnerID=40&md5=514506c4fe8763ff23634ccc991c9341 Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu Gabur G.D., Teodosiu C., Gabur I., Cotea V.V., Peinado R.A., López de Lerma N. Evaluation of aroma compounds in the process of wine ageing with oak chips. Foods. 2019;8(12) doi: 10.3390/foods8120662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favell J.W., Wilkinson K.L., Zigg I., Lyons S.M., Ristic R., Puglisi C.J., Noestheden M. Correlating sensory assessment of smoke-tainted wines with inter-laboratory study consensus values for volatile phenols. Molecules. 2022;27(15) doi: 10.3390/molecules27154892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandino A., Lovisolo C. Abiotic stress effects on grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): Focus on abscisic acid-mediated consequences on secondary metabolism and berry quality. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2014;103:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.10.012. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84897957949&doi=10.1016%2fj.envexpbot.2013.10.012&partnerID=40&md5=4761c2225ef180914603a2c6bb03f17a Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka Y., Baldock G.A., Parker M., Pardon K.H., Black C.A., Herderich M.J., Jeffery D.W. Glycosylation of smoke-derived volatile phenols in grapes as a consequence of grapevine exposure to bushfire smoke. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(20):10989–10998. doi: 10.1021/jf103045t. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-78049236185&doi=10.1021%2fjf103045t&partnerID=40&md5=616b2c455c24eb457ab8e2ff979d7646 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hulst L., Munguia P., Culbert J.A., Ford C.M., Burton R.A., Wilkinson K.L. Accumulation of volatile phenol glycoconjugates in grapes following grapevine exposure to smoke and potential mitigation of smoke taint by foliar application of kaolin. Planta. 2019;249(3):941–952. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-03079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Parker M., Hayasaka Y., Simos C., Herderich M. Compositional changes in grapes and leaves as a consequence of smoke exposure of vineyards from multiple bushfires across a ripening season. Molecules. 2021;26(11) doi: 10.3390/molecules26113187. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85107397519&doi=10.3390%2fmolecules26113187&partnerID=40&md5=d2a4d4f31ea5409b551edbd43b329269. doi:10.3390/molecules26113187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison K.R., Gibberd M.R., Pollnitz A.P., Wilkinson K.L. Smoke-derived taint in wine: The release of smoke-derived volatile phenols during fermentation of merlot juice following grapevine exposure to smoke. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56(16):7379–7383. doi: 10.1021/jf800927e. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-51649084614&doi=10.1021%2fjf800927e&partnerID=40&md5=21842b8da7903e26a01f6d400d36f582 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison K.R., Wilkinson K.L., Pollnitz A.P., Williams H.G., Gibberd M.R. Effect of timing and duration of grapevine exposure to smoke on the composition and sensory properties of wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2009;15(3):228–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0238.2009.00056.x. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-70350334899&doi=10.1111%2fj.1755-0238.2009.00056.x&partnerID=40&md5=83663c8cdec15c0133e1798ed23ae052 Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison K.R., Wilkinson K.L., Williams H.G., Smith J.H., Gibberd M.R. Smoke-derived taint in wine: Effect of postharvest smoke exposure of grapes on the chemical composition and sensory characteristics of wine. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(26):10897–10901. doi: 10.1021/jf072509k. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-38049052469&doi=10.1021%2fjf072509k&partnerID=40&md5=3a3d8b144c80ff18a0405c81df5771f0 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Ezernieks V., Reddy P., Elkins A., Krill C., Murphy K., Spangenberg G. A simple GC-MS/MS method for determination of smoke taint-related volatile phenols in grapes. Metabolites. 2020;10(7):294. doi: 10.3390/metabo10070294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga J.A. The contribution of wood to the flavor of alcoholic beverages. Food Reviews International. 1989;5(1):39–99. doi: 10.1080/87559128909540844. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0003078174&doi=10.1080%2f87559128909540844&partnerID=40&md5=b26f927d68232fe0a8e21b531da5ddc8 Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher L.P., Brauer M., Lipsett M., Zelikoff J.T., Simpson C.D., Koenig J.Q., Smith K.R. Woodsmoke health effects: A review. Inhalation Toxicology. 2007;19(1):67–106. doi: 10.1080/08958370600985875. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-33845266256&doi=10.1080%2f08958370600985875&partnerID=40&md5=0048e4c9aeddd926ac24ff85e38fdd7b Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noestheden M., Noyovitz B., Riordan-Short S., Dennis E.G., Zandberg W.F. Smoke from simulated forest fire alters secondary metabolites in Vitis vinifera L. berries and wine. Planta. 2018;248(6):1537–1550. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2994-7. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85052663787&doi=10.1007%2fs00425-018-2994-7&partnerID=40&md5=539b30e35ed8cee13160f0ffa7373cca Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M., Osidacz, P., Baldock, G. A., Hayasaka, Y., Black, C. A., Pardon, K. H., . . . Francis, I. L. (2012). Contribution of several volatile phenols and their glycoconjugates to smoke-related sensory properties of red wine. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 60(10), 2629–2637. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84858313657&doi=10.1021%2fjf2040548&partnerID=40&md5=b8c5cd1fae29a5dce4ae4faa9cc7ee0f. doi: 10.1021/jf2040548. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pollnitz A.P., Pardon K.H., Sefton M.A. Quantitative analysis of 4-ethylphenol and 4-ethylguaiacol in red wine. Journal of Chromatography A. 2000;874(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimpe-Rutledge A.C., Codreanu S.G., Sherrod S.D., McLean J.A. Untargeted metabolomics strategies—Challenges and emerging directions. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2016;27(12):1897–1905. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y. Retrieved from doi:10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y. doi:10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schymanski E.L., Jeon J., Gulde R., Fenner K., Ruff M., Singer H.P., Hollender J. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environmental Science and Technology. 2014;48(4):2097–2098. doi: 10.1021/es5002105. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84894259913&doi=10.1021%2fes5002105&partnerID=40&md5=7540ad744a8b6d14160ff475a746de8c Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D.P., Chong H.H., Pitt K.M., Cleary M., Dokoozlian N.K., Downey M.O. Guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol accumulate in wines made from smoke-affected fruit because of hydrolysis of their conjugates. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2011;17(2):S13–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skouroumounis G.K., Sefton M.A. Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of alcohols and their β-D-glucopyranosides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48(6):2033–2039. doi: 10.1021/jf9904970. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0033936556&doi=10.1021%2fjf9904970&partnerID=40&md5=0ec37120c7b0637f4ca39befa5f5fc60 Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson K.L., Elsey G.M., Prager R.H., Tanaka T., Sefton M.A. Precursors to oak lactone. Part 2: Synthesis, separation and cleavage of several β-D-glucopyranosides of 3-methyl-4-hydroxyoctanoic acid. Tetrahedron. 2004;60(29):6091–6100. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2004.05.070. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-3042651376&doi=10.1016%2fj.tet.2004.05.070&partnerID=40&md5=a890a364b1a3005ea4b896be1698d0c5 Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson K.L., Ristic R., Pinchbeck K.A., Fudge A.L., Singh D.P., Pitt K.M., Herderich M.J. Comparison of methods for the analysis of smoke related phenols and their conjugates in grapes and wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2011;17(2):S22–S28. Retrieved from. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00147.x. doi:doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00147.x. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth J., Guo W., Baumes R., Günata Z. Volatile compounds released by enzymatic hydrolysis of glycoconjugates of leaves and grape berries from Vitis vinifera Muscat of Alexandria and Shiraz cultivars. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49(6):2917–2923. doi: 10.1021/jf001398l. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0034840532&doi=10.1021%2fjf001398l&partnerID=40&md5=a792269d88b509c962ce532f040cbbbc Retrieved from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoecklein B., Fugelsang K.C., Gump B.H., Nury F.S. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. Wine analysis and production. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of identified metabolites that significantly increased in smoke-tainted grapes.

Map of Victoria showing collection sites for grapes in 2020. (Map by Wayne Harvey, Agriculture Victoria Research, Epsom, 12/3/2020.) B) In field scanning of grapes.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.