Abstract

Poultry meat, an essential source of animal protein, requires stringent safety and quality measures to address public health concerns and growing international attention. This review examines both direct and indirect factors that compromise poultry meat quality in intensive farming systems. It highlights the integration of rapid and micro-testing with traditional methods to assess meat safety. The paper advocates for adopting probiotics, prebiotics, and plant extracts to improve poultry meat quality.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Biotechnology

Introduction

Poultry meat production continues to outpace other meat sources like pork, beef, and sheep. It is expected to exceed 139 million metric tons in 2023, marking an almost 3% increase compared to 2022, primarily driven by increased production in Brazil and the United States1. China exported 628,500 tonnes of poultry meat for a total export value of $2.212 billion from January to December 2022. Approximately 80% of these exports originated from countries including Brazil, the United States, and Russia. The largest share of the exported goods was chicken, accounting for 84.7%, followed by duck and goose meat (12.8% and 2.5%, respectively)2. According to He and Liu, processed products comprised 57.4% of exports, followed by frozen products (28.0%) and chilled products (14.6%)2. The share of poultry meat in total meat production increased from 8.3% in 1985 to 26.57% in 2021, highlighting the rapid development of the poultry industry. However, because of the rapid growth of modern intensively farmed poultry, the complexity of factors affecting the production and processing of poultry meat makes it difficult to ensure the production of high-quality poultry meat for the market2. The influence of economic development and increased consumer health awareness has led to substantial growth in poultry consumption in regions like Asia, particularly in China and India. Similarly, Western countries have a growing preference for organic and antibiotic-free poultry products3. Consequently, research focused on improving poultry meat quality has also increased. This includes efforts to enhance feed efficiency, optimize genetic selection, and improve management practices to ensure better meat quality. Additionally, heightened consumer awareness of food safety, animal welfare, and environmental sustainability is prompting the industry to adopt stricter standards and innovative practices in poultry farming and meat processing2.

This consensus is that the carcass quality influences the price of poultry meat. Poultry meat quality has been widely studied in recent years, and its evaluation has become a growing demand in the international market. As consumers become more discerning, they are not only concerned about sensory and nutritional properties but also the visual appeal of the meat. Modern poultry breeding, which often involves intensive indoor breeding conditions, can lead to skin pigmentation, scratches, and other skin lesions. These problems affect the visual quality of poultry carcasses4. Health performance is a significant concern in the poultry industry. Factors including heat stress and nutritional and metabolic diseases due to improper poultry management can affect the health of the poultry and, consequently, the meat quality5. The feed’s nutritional composition and the feed additives’ composition are also essential in influencing the quality of the meat. Still, it must be mentioned that feed deterioration, such as contamination with mycotoxin, heavy metals, and chemicals, has an even more severe effect on poultry meat quality4.

In recent years, researchers have been investigating effective ways to enhance meat quality in response to risks to poultry meat quality posed by various influencing factors. Probiotics are a group of beneficial microorganisms that help maintain the balance and health of the host’s intestinal microbiota. They can increase poultry’s daily weight gain and feed conversion ratio, thereby improving productivity. Probiotics can also positively affect poultry meat quality through various mechanisms, such as increasing the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, lowering the content of saturated fatty acids, and minimizing oxidative damage to the meat6. Prebiotics are organic substances that stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial intestinal microbiota. Prebiotics also change the composition of gut microbes and increase the flavor substances in meat. Additionally, prebiotics have improved growth performance, immunological function, and meat quality in poultry7. Plants and plant extracts have attracted attention for their naturalness, non-toxicity, and unique biological activities. These plant extracts have been demonstrated to be beneficial in enhancing poultry meat quality and growth performance, in addition to being a natural substitute for synthetic chemical additives8. This review suggests improvement strategies for poultry meat quality to meet consumer demand for high-quality meat. It underscores the importance of scientific agricultural management and quality feed selection, and it calls for further research to explore the practical application and effectiveness of these strategies for the sustainable development of the poultry industry.

Meat quality evaluation indexes

Meat color

Meat color is one of the commercially important characteristics of meat quality because consumers associate the appearance of meat with the freshness of the product, and meat color substantially influences consumer willingness to purchase. Research shows that consumers usually associate bright cherry-red or pink meat with freshness and quality, while discoloration or browning leads consumers to believe the meat is spoiled and of lower quality9. This perception directly impacts marketability, as meat products that do not meet these color expectations are likely to be rejected by consumers, regardless of their actual quality or safety. Myoglobin, hemoglobin, and cytochrome C are the primary heme pigments present in meat9. The red color and discoloration of myoglobin are determined by the chemical state of myoglobin, which is influenced by some factors, including pre-slaughter factors (genetics, feed, handling, pressure, heat and cold pressures, and gaseous environments), and slaughter, freezing, and processing conditions (nitrates, additives, and pH)10. Temperature and pH after the animal has been killed have an effect on the degree of protein denaturation as well as the physical appearance of the meat. These two parameters affect the reflection of light from the exterior and interior of the meat surface, as the reflection of light is directly proportional to the degree of protein denaturation11. The effect of light reflection on meat color L* is opposite to that caused by hemoglobin concentration and has the least effect on meat color a* and b*4. Protein denaturation in muscle is limited when the pH level is ≥6.0, and the lower the light reflection the greater the transparency of meat appearance. However, muscle suffers from protein denaturation at pH levels below 6.0, which causes an increase in opacity and light reflection4.

Meat tenderness

Tenderness is the most essential quality factor in consumer satisfaction with poultry meat. Tightly bound to muscle proteins, water has a swelling effect on muscle proteins, occupying the space between muscle fibers and giving the meat a firmer structure12. The rate and extent of chemical and physical alterations in the muscle during the poultry slaughter also determine the meat’s tenderness13. When a chicken is slaughtered, blood circulation within the muscle stops, preventing oxygen or nutrients from reaching the muscle; when the muscle is depleted of energy, it contracts and becomes stiff; with time, the meat will soften again, making it tender when cooked13. The main determinants of meat tenderness are the maturity of the connective tissue and the contractile state of the myofibrillar proteins, environmental stresses, the bird’s age, the rigor mortis development rate, and the freezing rate and duration14. Moreover, the contractile state of myofibrillar proteins depends on the rate of development of rigor mortis and the severity of post-slaughter rigor mortis. At the same time, the maturity of connective tissue can increase with age14. According to Bowker et al.15, the tenderness of the breast muscles of older broilers is lower, and there is an interaction between the maturity of connective tissue and the state of collagen in the muscle.

Various methods are used to precisely measure meat tenderness in research settings, often closely related to consumer perceptions. The Warner–Bratzler shear force (WBSF) test is one of the most widely used objective methods for measuring meat tenderness16. This test involves measuring the force required to cut through standardized meat samples, providing a quantitative value of tenderness. Another commonly used method is texture profile analysis (TPA), which primarily simulates the chewing process by subjecting samples to two cycles of compression. The entire testing process is recorded by a computer, with the software outputting a texture profile curve (force-time curve), from which parameters such as peak, time, and area can be calculated to determine the hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, adhesiveness, resilience, and chewiness17. Additionally, sensory evaluation panels, composed of trained panelists or consumers, are used to assess the tenderness of meat samples, providing subjective indicators to complement objective measurements18.

Meat flavor

Flavor is another quality attribute that influences consumer acceptance of chicken breast meat. Although it can be challenging for consumers to distinguish the flavor and odor of different meats when eating them, different flavors occur in chicken breasts during the cooking process due to interactions between sugar and amino acids, lipid and thermal oxidation, and thiamine degradation19. The lipid-derived compounds (e.g., hexenal, heptenal, octenal, nonenal, undecenal, and dodecenal), as well as aldehydes (e.g., octanal, nonanal, decanal, and dodecadienal), have been associated with the distinctive aroma and flavor of chicken meat20. These specific compounds contribute to different sensory experiences for consumer groups. For example, hexenal and nonenal are associated with grassy and citrus flavors, which some consumers find fresh and pleasant21. On the other hand, compounds such as octanal and decanal impart fatty and citrus aromas, providing rich and full-bodied flavors that enhance the overall dining experience22. According to Jayasena et al. 23, cooking also enhances the flavor of chicken by causing a glycosamine reaction (also known as the Millard reaction). During heat treatments that include temperatures over 100°C (e.g., broiling, grilling, deep-frying, and pressure cooking), large quantities of heterocyclic compounds are formed in the aroma of cooked meat. The pH of the meat itself is important in the Millard reaction for the formation of aroma, with pH values between 4.5 and 6.5 favoring the formation of nitrogenous compounds that contribute to the aroma of the food24. The commencement of the post-slaughter rigor mortis reaction results in the formation of several chemical flavor compounds, such as sugars, organic acids, peptides, free amino acids, and adenine nucleotide metabolites, which are also crucial in shaping the final flavor of the meat25. Due to differences in cultural background, dietary habits, and personal taste preferences, different consumer groups have varied preferences for these sensory attributes. Understanding these preferences is crucial for producers to cater to specific markets and improve consumer satisfaction with their products.

pH value in meat

The pH value directly affects meat quality attributes such as tenderness, WHC, color, juiciness, and shelf life. Broiler breast muscle has good WHC due to the hydrophilic nature of proteins, but the hydrophilicity of fibrous proteins in muscle is easily affected by the pH value; after slaughter, the process of glycolysis continuously produces lactic acid; with the prolongation of meat storage time, the pH value decreases; the proteolytic enzyme activity in the muscle is inhibited, which also affects the meat quality of tenderness26. In addition, the decrease in pH value affects the rate of denaturation of myosin and actin in muscle fibers, which reduces their hydrophilic function27. Water is mainly coupled to the hydrophilic groups of proteins through hydrogen bonding. With the continuous occurrence of glycolysis in muscle and the lowering of pH, the electrostatic interaction between proteins and water in muscle fibers is weakened. The coupling structure between the two is continuously destroyed, ultimately resulting in water loss from muscle28.

Managing and controlling pH is crucial for maintaining meat quality in poultry farming and processing. During the pre-slaughter stage, minimizing stress in poultry helps maintain a higher pH post-slaughter29. Stress management techniques mainly include gentle handling, appropriate transportation conditions, and adequate rest before slaughter29. Additionally, adding certain feed additives (such as antioxidants and vitamins) can reduce oxidative stress and improve overall muscle metabolism, thereby helping maintain muscle pH30. Rapid chilling immediately after slaughter can slow down glycolysis, reducing the rate of pH decline31. Controlled storage conditions during poultry meat transportation and storage, including maintaining appropriate temperature and humidity levels, also play an important role in stabilizing pH levels31.

Water holding capacity of meat

WHC directly impacts meat color and tenderness and is one of the most important functional characteristics of raw meat. Several indicators have been proposed to categorize the WHC of meat, including drip loss and cooking loss32. Approximately 88% to 95% of the water in muscle is held in protein-bound existence between actin and myosin within the cell, while the rest is located between myofibers33. Changes in the pH of the muscle will lead to a decrease in the active substances on the water-protein binding sites. When the pH of the muscle reaches the isoelectric point, the positive and negative charges on the active substances on the water-protein binding sites are equal, which will lead to the inability to combine with the charged groups of water and ultimately result in a decrease in the WHC of the meat34. The lack of energy supply to the animal after slaughter causes the aggregation of actin complexes within the muscle, which leads to the loss of space between myofibrillar proteins and, consequently, to a decrease in the WHC of the meat35. Changes in water in the muscle also cause changes in light reflection on the surface of the breast muscle, thus affecting changes in the meat color of broiler breast muscle.

Water transport in meat

Water in muscle can be stored in different spatial structures, mainly within myofibrils, between myofibrils, between myofibrils and cell membranes, between myocytes, and between muscle bundles. Low-frequency nuclear magnetic resonance (L-NMR) techniques are mainly utilized to characterize the movement of water molecules and their distribution in muscle, based on the determination of relaxation time in L-NMR36. Because of the mutual attraction between the surface charge of macromolecules like proteins and the number of water molecules, a multilayer model of water with different degrees of association is formed. The water state is categorized into three types, according to the strength of the water-binding force, including bound water (T2b), immobilized water (T21), and free water (T22)37. Among them, bound water is water that is tightly bound to the surface of muscle proteins, immobile water is water that is tethered to the thick and thin filaments within the muscle fiber lattice through capillary forces, or water that is retained between the myofibrils and cell membranes, and free water is water that exists outside of the myofibrillar gel lattice because of the weak molecular binding force38. The texture, water retention capacity, and sensory characteristics of muscles can be effectively evaluated by analyzing the distribution of water migration in muscles. For example, in chicken patties containing different proportions of wood breast meat, the decrease in the ratio of free water is related to the deterioration of meat quality38.

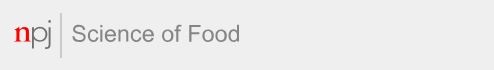

Protein secondary structure analysis by Raman spectroscopy

The protein secondary structure is the specific conformational structure that is formed by the polypeptide backbone through the hydrogen bond connection along a particular axis of circling or folding, mainly for the four structures including ɑ-helix, β-folding, β-cornering, and random coil, of which the first two are regular and orderly structure, whereas the last two are disordered39. When the process of forming a protein is affected by external conditions, the composition of the protein secondary structure will be changed, resulting in changes in the structure of proteins and thus affecting the functional role of proteins. Therefore, examining the secondary protein structure of breast muscle fibers can predict changes in protein function and comprehend differences in meat quality. Raman spectroscopy is a quick and non-destructive monitoring technique that provides quantitative and qualitative data on protein changes to analyze the protein secondary structure of myogenic fibers39. Wu et al. demonstrated that the increase in the content of ɑ-helical structures in muscle is closely related to the increase in water within myogenic fibers40. Recently, the protein secondary structure in L-NMR-treated pork was examined using Raman spectroscopy by Yang et al., which found that a decrease in the ɑ-helix content and an increase in the β-fold content in meat leads to tight binding of protein to water molecules, which reduces the mobility of water and improves the water retention in meat41. Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of meat quality evaluation indicators.

Fig. 1. Meat quality evaluation indexes in poultry.

This comprehensive diagram illustrates the multifaceted approach to evaluating poultry meat quality, structured into eight primary sections, including meat color, pH, water holding capacity, water transport, texture profile analysis, protein structure, flavor, and tenderness, they represent different aspects of meat quality. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint, with key elements from BioReader (https://app.biorender.com/).

Influence of farming management patterns on poultry meat quality

Incubation condition

Poultry muscle is the most abundant edible tissue on the table and provides an essential high-protein source for humans. Myofibers in poultry originate at the early embryogenesis stage, and the overall number of myofibers is almost determined before hatching42. The hatching stage is critical in the life cycle of poultry, covering the period from the onset of embryogenesis to the young bird stage or birth. Muscle development during the embryonic stage is critical for muscle growth and, ultimately, meat yield and quality after hatching43. It has been shown that regulating muscle fiber development during incubation can increase the number of muscle fibers and fiber diameter44.

In recent years, the effects of altered incubation conditions on embryonic development and muscle growth in birds have received much attention in the poultry science community42. Incubation conditions, including temperature, humidity, oxygen concentration, ventilation, and light, may significantly affect the number, shape, and structure of myofibrils, which can have a long-term impact on post-hatch muscle growth and meat quality45. In Table 1, changes in incubation conditions are illustrated to trigger changes in muscle. Appropriate incubation conditions may alter muscle tissue’s morphology and final muscle mass in post-hatching birds by modulating embryonic hormone levels and beneficial myoblast activity43.

Table 1.

Effects of altered incubation conditions on muscle growth and development

| No. | Species | Incubation condition | Specific changes | Muscle changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chicken | Change in temperature and oxygen level | Embryo day 11–20 in low oxygen and high temperature | Causes muscle lesions | 117 |

| 2 | Chicken | Transient temperature change | Embryo day 10 was placed at a high temperature of 38.8 °C | Changes in gene transcription levels that affect muscle development | 118 |

| 3 | Chicken | Monochromatic stimulation | Monochromatic green light for stimulation | Affects satellite cell activity, gene expression, and muscle growth | 119,120 |

| 4 | Chicken | Drug stimulation | Glibenclamide drug applications | Increased muscle tone | 121 |

| 5 | Chicken | Intraembryonic feeding techniques | Delivery of bioactive to chicken embryos at the final stage of incubation using the in-ovo technique | Affects muscle metabolism and development | 45 |

| 6 | Chicken | Changes in temperature and exposure time after incubation | Treatment period immediately after hatching (exposure to cold or heat stress) | Affects muscle growth and morphology | 122 |

| 7 | Duck | Incubation persistent heat stress | Temperature increased by 1 °C in embryo day 11–20 | Affects muscle growth related-gene expression | 123 |

| 8 | Chicken | Continuous temperature change | Exposure to 38.8 °C for hyperthermia treatment at embryonic day 10–14 | Affects body weight, plasma parameters, and meat quality | 124 |

| 9 | Chicken | Transient temperature change | Exposure to 38.8 °C for hyperthermia treatment at embryonic days 7–10 and 10–13 | Affects gene transcription and muscle development | 125 |

| 11 | Chicken | Incubation persistent heat stress | Temperature increased by 1 °C in embryo day 10–27 | Affects muscle development and activates endoplasmic reticulum stress | 126 |

| 12 | Chicken | Maternal immunization | Maternal injection of 0.5 mg myostatin | Inhibited growth and reduced body weight and muscle mass in young chicks | 127 |

| 13 | Chicken | Egg supplementation with probiotics | Eggs were sprayed with different probiotics: Lactobacillus paracasei DUP 13076 (LP) and L. rhamnosus NRRL B 442 (LR) before and during incubation. | Promotes muscle growth and development | 128 |

| 14 | Chicken | Glycerol injection | Glycerol injection into eggs on the day of incubation ED 17–18 days | Affects muscle and liver metabolism | 129 |

| 15 | Duck | Increased incubation temperature | Increase incubation temperature by 1 °C throughout the incubation cycle | Affects DNA methylation in leg muscles, gene expression, and enzyme activity | 130,131 |

High stocking densities

Stocking density is an important parameter in poultry farming, which directly affects poultry growth and meat quality. High stocking densities may lead to increased competition among poultry, affecting their intake and growth rate46. In addition, high stocking densities may also lead to mutual injuries among poultry, resulting in fractures, leg diseases, heat stress, scratches, and other illnesses that may affect their physiological health and meat quality47,48. Studies have shown that high stocking densities increase muscle cooking losses, decrease pH, and increase lactate dehydrogenase activity, all hallmarks of reduced meat quality. In addition, the antioxidant capacity of poultry is affected, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and reduced oxidative stability of meat49,50. This affects the taste and nutritional value of the meat and may also affect consumer acceptance48. Similar findings were also demonstrated in the study of Wang et al., where broilers raised at a high density of 28 birds/m2 resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of abdominal fat and fat content of thigh muscles51. At the same time, this may be related to the abundance of some microbes like Akkermansiaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Faecalibacterium52. Specific changes in poultry meat quality induced by high stocking densities are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of high stocking densities on variation in meat quality

| No. | Species | Stocking densities | Position | Variation in meat quality | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chicken | 28 birds/m2 | Breast and thigh meat | The abdominal fat percentage and the fat content of thigh muscle declined | 52 |

| 2 | Chicken | 23 and 26 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Shear force in breast meat increased | 132 |

| 3 | Chicken | 20, 25 and 30 birds/pen | Breast and wing meat | Final body, drumstick, breast, and wing weights linearly declined with stocking density | 133 |

| 4 | Chicken | 18 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Cooking loss and pH at 45 min decline; activity of lactate dehydrogenase increased | 54 |

| 5 | Chicken | 18.6 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Lightness at 45 min and 24 h after slaughter increased; drip loss at 24 h and 48 h increased | 55 |

| 6 | Chicken | 18 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Meat color b* declined | 56 |

| 7 | Chicken | 20 birds/m2 | Breast and thigh meat | Cooking loss and drip loss of breast and thigh muscles increased | 134 |

| 8 | Chicken | 26 and 35 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Cooking loss, meat color L* and a* at 48 h postmortem increased linearly with decreasing stocking density; ultimate breast pH and nitrogen content decreased linearly with decreasing stocking density | 135 |

| 9 | Chicken | 18 birds/m2 | Breast meat | pH at 24 h increased | 136 |

| 10 | Chicken | 12 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Breast weights declined | 137 |

| 11 | Chicken | 22.5 birds/m2 | Breast meat | pH values increased slightly as density increased | 138 |

| 12 | Chicken | 37 kg/m2 | Breast and thigh meat | Breast meat pH at 24 h, shear force, and cooking loss declined; thigh meat shear force increased | 50 |

| 13 | Chicken | 25.3 and 30.4 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Breast weights declined | 139 |

| 14 | Duck | 9 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Cooking loss increased | 140 |

| 15 | Geese | 6.5 and 7.5 birds/m2 | Breast meat | The intramuscular fat content of breast meat decreased linearly with decreasing stocking density | 51 |

| 16 | Duck | 11 birds/m2 | Breast meat | Drip loss and pH at 45 min declined | 141 |

On the contrary, low stocking densities can provide more spacious living space for poultry and help them thrive, but it may increase farming costs. Maintaining a stocking density of 10–12 birds/m² ensures broilers optimal growth and meat quality. At lower densities, broilers experience reduced stress levels and improved feed conversion rates, leading to better meat quality and flavor. The optimal stocking density for laying hens is 6-8 birds/m². This density helps to increase egg production and quality while maintaining the overall health of the hens. The stocking density for turkeys is 3–5 birds/m², which provides enough space for activity, reduces the risk of leg problems, and improves overall meat quality53. To meet the challenges posed by high stocking densities, nutritional supplements such as nicotinamide, sodium butyrate, and coumarin can be added, effectively improving poultry’s antioxidant capacity and enhancing meat quality54–56. These supplements mitigate the adverse effects of high stocking densities to a certain extent by regulating the physiological mechanisms of poultry and enhancing their resistance to stress. Therefore, choosing appropriate stocking densities is the key to ensuring the healthy growth of poultry and obtaining high-quality meat. In actual breeding, it is necessary to rationally adjust the breeding density according to the type of poultry, growth stage, and breeding environment to achieve economic and biological benefits11.

Growth cycle

As meat quality has become more of a concern than the animal growth rate, more and more studies are beginning to examine the relationship between the growth cycle and meat quality. Slow-growing poultry (with a rearing cycle of more than 90 days) is gaining favor with consumers, while fast-growing broilers (within a rearing cycle of 35–42 days) are being questioned in China57. It was found that there were significant differences in muscle fiber characteristics between slow-growing poultry (Xueshan chickens) and fast-growing poultry (Ross 308 broilers). Slow-growing poultry had thicker muscle fibers, which may have resulted in tougher meat. In addition, slow-growing poultry had a higher percentage of oxidized fibers in the leg meat than in the breast meat58. These oxidized fibers may increase the meat’s redness and intramuscular fat content58.

Using GC–MS and LC–MS techniques, the researchers found differences in the metabolic properties of meat from poultry with different growth rates. For example, the meat of fast-growing broilers (Cobb 500 broilers) was mainly enriched with amino acids and their derivatives. In contrast, slow-growing broilers (Beijing-You chicken) and Pekinese oiled chicken were supplemented with more biologically active compounds such as ɑ-linolenic acid, linoleic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid, which may be significantly related to the juiciness and tenderness of the meat of slow-growing broilers (Beijing-You chicken)59. Similar studies have been demonstrated in duck meat, where it was found that fast-growing ducks (Cherry Valley ducks) and slow-growing ducks (Small-sized Beijing duck and Liancheng White duck) differed in muscle fiber characteristics60. In contrast, slow-growing ducks had a higher content of released water, intramuscular fat, and lower water content in their meat, and all of these differences may be related to the different growth cycles of broiler ducks60. Huo et al. in a study of muscle characteristics of 1-day-old slow-growing broilers (Xueshan chicken) and fast-growing broilers (Ross 308), found that slow-growing broilers had a higher density of breast muscle fibers and lower glycolytic potential, which may be related to differences in the meat quality of the two breeds of broilers61.

In contrast, fast-growing broilers often have lower muscle fiber density and thickness due to their shorter growth cycles. This can result in more tender meat, but the intensity of flavor and juiciness may be lower58. Longer growth cycles are characteristic of slow-growing poultry, allowing for more extensive muscle fiber development, resulting in higher muscle density and coarser fibers. This may lead to tougher meat, but the increased intramuscular fat content and a higher proportion of oxidative fibers help improve flavor and juiciness59. Therefore, optimizing management practices (such as adjusting the rearing cycle) is a strategy to enhance specific meat quality attributes. For example, slightly extending the growth cycle of fast-growing broilers may help balance muscle fiber development and fat content, thereby improving meat tenderness and flavor.

Overuse of antibiotics

The use of antibiotics has been an important topic in modern poultry production. Antibiotics have long been widely used as growth promoters to improve poultry’s growth efficiency and overall health. However, there has been widespread concern regarding the use of antibiotics in poultry feed, especially their potential risks to human health, such as increased antibiotic resistance and drug residues in recent years62. Overuse of antibiotics may result in their poultry residues remaining in the meat after the poultry has been slaughtered. From a meat quality perspective, antibiotic use may affect poultry meat’s nutritional value and sensory properties. Some studies have shown that antibiotic use may change poultry meat’s pH, color, moisture retention capacity, and tenderness63. In addition, the use of antibiotics may increase oxidative stress in poultry, leading to lipid over-oxidation and affecting the degradation of proteins in poultry muscle, resulting in weaker muscle fibers, which reduces the tenderness and texture of poultry meat64. In a survey of sulfonamide and β-lactam antibiotic residues in commercial chicken meat sold in Nairobi, Kenya, a total of the sulfonamides (SAs), sulfapyridine (SPD), sulfadiazine (SDZ) and sulfamethazine (SMZ) and the β-lactams (βLs); ampicillin (AMP), penicillin G (PEG), and amoxicillin (AMX), residual SAs varied between 0.1 and 154.4 μg kg−1, with SPD showing the most significant concentration in ex-layers’ poultry samples65. βLs were detected from 19.7 to 309.0 μg kg−1, with AMX having the maximum amount in ex-layers65. Average AMX levels in all chicken types and AMP in broilers exceeded the Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs). All examined βLs posed a minimal threat (<1% ADI) to human well-being. Both SPD and SDZ presented a notable risk (1–5% ADI) in specific poultry samples, while SPD in ex-layers’ chicken meat specifically posed a significant threat (>5% ADI) to children65. In conclusion, while antibiotics have merits in poultry production, their potential impact on poultry meat quality and public health cannot be ignored. Antibiotic-free poultry production and using natural alternatives may be the future as consumers become increasingly concerned about food safety and quality.

Effects of heat stress on meat quality

Ambient temperature is a crucial factor affecting poultry production, especially in hot seasons or tropical regions, where high ambient temperatures may lead to heat stress, resulting in reduced growth performance and even damage to poultry meat quality66. Heat stress reduces poultry’s growth rate and feed efficiency, impairs the immune response, alters the gut microbial community, and degrades meat quality67. The denaturation of myoplasmic proteins increases due to the rapid pH drop caused by heat stress, especially when muscle temperatures are high after slaughter, which reduces the water-holding capacity of the muscle68. In addition, to dissipate body heat, poultry will pant at an accelerated rate, increasing CO2 emissions, leading to a decrease in blood pH and triggering metabolic acidosis in skeletal muscle67.

Heat stress increases oxidative stress in poultry, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS impair the structure and function of enzymes that regulate sarcoplasmic calcium levels, and through a chain reaction of free radical oxidation, including a decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the onset of an inflammatory response, may lead to lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation69. Chang et al. demonstrated that heat stress regulates the expression of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), catalase (CAT), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), through nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 - antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) signaling pathway. Detoxifying enzyme genes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), catalase (CAT), and heme oxygenase-170. Impaired meat quality by accelerating muscle postmortem glycolysis and overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in rapid pH decline70.

In addition, it has been found that heat stress reduces glycogen reserves in poultry muscle, resulting in dark, firm, and dry (DFD) meat with a higher final pH and WHC5. To address the challenges of heat stress, researchers and producers are looking for strategies to mitigate its effects on poultry health and performance. For example, poultry can be helped to better cope with heat stress by adapting feed formulations, adding antioxidants and other nutritional supplements, and improving husbandry management and environmental control measures5.

Genetic factors

The genotype of poultry largely determines its meat quality characteristics. Different poultry breeds exhibit significant differences in muscle fiber types, fat deposition, and sensory qualities of meat. Genetic factors largely control these characteristics. For example, the fat content and distribution in muscles directly affect the tenderness and flavor of the meat, while muscle fiber types influence the texture and cooking properties of the meat71. Muscle fiber types can be classified into slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibers; the former is rich in fat and has high oxidative metabolism, resulting in more tender meat, while the latter is the opposite. These traits can be regulated through genetic selection to improve meat quality72.

Different genotypes of poultry exhibit significant differences in muscle fiber composition and fat metabolism pathways. These differences can be deeply analyzed and optimized through molecular biology techniques. Marker-assisted selection (MAS) is a breeding method that uses genetic markers associated with meat quality traits for selection73. MAS can significantly enhance breeding efficiency and is more precise than traditional phenotypic selection74. Screening and selecting poultry individuals carrying superior meat quality genes can predict their meat quality traits early in the breeding process, avoiding extensive breeding trials. Research has identified several genetic markers associated with poultry meat quality, including genes related to muscle fiber type, fat deposition, and sensory qualities74. These markers can be used to screen poultry individuals early, thereby improving breeding efficiency and outcomes. Meanwhile, modern molecular breeding techniques can use gene editing technologies (such as CRISPR/Cas9) to directly modify meat quality-related genes to exhibit desirable meat quality traits75. Genomic selection involves analyzing large-scale genomic data to identify genetic markers associated with meat quality and using these markers for breeding selection, improving breeding efficiency and accuracy75. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the influence of farming management patterns on poultry meat quality.

Fig. 2. Multiple feeding management deficiencies that affect poultry meat quality.

This diagram presents an integrated view of how different aspects of feeding management, including growth cycle, high stocking density, overuse of antibiotics, heat stress, and incubation conditions, influence the quality of poultry meat. Moreover, complex interactions between various management factors in poultry production can lead to different meat quality outcomes. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint, with key elements from BioReader (https://app.biorender.com/).

Influence of quality of feed on poultry meat quality

Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are a group of secondary metabolites produced by various molds. They are primarily found in basic agricultural products and animal feeds, with high detection rates in agricultural and poultry products, especially in developing countries76. Currently, more than 500 mycotoxins have been reported, including Aflatoxin B1(AFB1), Ochratoxin A (OTA), Deoxynivalenol (DON), Zearalenone (ZEN), and others77. Studies have shown that when poultry consume feed contaminated with mycotoxins, these toxins may be transferred to poultry meat and eggs, affecting the safety and quality of poultry products78. The study has shown that poultry meat consuming mycotoxin-contaminated feeds becomes darker in color, increases in pH, decreases in water-holding capacity, and changes in fatty acid composition, especially in polyunsaturated fatty acids79. These changes will not only affect the sensory quality of poultry meat but may also affect its nutritional value and health risks. Table 3 summarizes the occurrence of mycotoxin-induced losses in meat quality.

Table 3.

Effects of different mycotoxins on meat quality

| No. | Types of mycotoxins | Dosages | Position | Variation in meat quality | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T-2 toxin | 4 ppm | Breast meat | Lower carcass yield and brisket yield | 142 |

| Bumonisin B1 | 20 ppm | ||||

| 2 | Aflatoxin B1 | 1 mg/kg BW | Breast and thigh meat | Drip loss and shear increased | 143 |

| 3 | Ochratoxin A | 172 μg/kg BW | Breast and thigh meat | pH24 and the water-holding capacity of meat declined | 144 |

| Deoxynivalenol | 200 μg/kg BW | ||||

| 4 | Mycotoxin mixtures | Unknown | Breast and thigh meat | Crude fat content and meat color L* values declined, and meat color a* and b* values increased | 145 |

| 5 | Aflatoxin B1 | 0 ppm and 0.5 ppm | Breast meat | Carcass yield and breast yield declined | 78 |

| 6 | Aflatoxin B1 | Unknown (produced by strain ATCC 13,608) | Breast meat | Meat color L* values and cooking loss increased | 79 |

| 7 | Ochratoxin A | 0.1 mg/kg BW | Breast meat | Breast yield declined | 146 |

| 8 | Aflatoxins | 70.7 ± 1.3 μg/kg feed | Breast and thigh meat | Meat color a* and b* values increased | 147 |

| 9 | Aflatoxin B1 | 2 ppm | Breast meat | Water holding capacity of meat declined | 77 |

| Ochratoxin A | |||||

| 10 | Deoxynivalenol | 0.62 mg/kg BW | Breast meat | Meat color L* values declined | 148 |

| 11 | Deoxynivalenol | 10 mg/kg feed | Breast and thigh meat | Decreased micronutrients in the breast meat | 149 |

| 12 | Zearalenone | 25 mg/kg BW | Breast meat | No significant changes in the total chemical composition of dry matter, crude protein, crude ether extract, and ash | 150 |

| 13 | Aflatoxin B1 | 50 μg/kg BW | Breast meat | Decrease in sensory indicators and damage to the secondary structure of proteins | 36 |

| 14 | Aflatoxins | 0.05 ppm | Breast meat | Meat color L* values increased, and unsaturated fatty acid content decreased | 79 |

| Fumonisin | 20 ppm |

Researchers have proposed several control strategies to reduce the adverse effects of mycotoxins in feed on poultry. Among the most effective methods are pre-harvest control of mycotoxin production and post-harvest contamination reduction76. Biological detoxification methods, i.e., converting mycotoxins into low-toxicity metabolites, are more unique, efficient, and environmentally friendly than chemical and physical methods79. In addition, the application of genetic modification and nanotechnology has shown great potential in reducing mycotoxin production76.

Researchers have proposed several control strategies to reduce the adverse effects of mycotoxins in poultry feed, with the most effective method being the implementation of pre-harvest preventive measures at the farm level to control the production and post-harvest contamination of mycotoxins. Implementing good agricultural practices (GAP), such as using resistant crop varieties and ensuring proper irrigation and drainage, can significantly reduce mycotoxin contamination. Using appropriate storage conditions for harvested crops, including controlling temperature and humidity, can prevent mold growth and mycotoxin production during storage76. Applying biological detoxification methods to contaminated feed, which converts mycotoxins into less toxic metabolites, and using mycotoxin binders and adsorbents in feed helps reduce the bioavailability of mycotoxins79. This approach is more unique, effective, and environmentally friendly than chemical and physical methods. Additionally, genetic modification and nanotechnology have shown great potential in reducing mycotoxin production76. Finally, regular monitoring and testing of mycotoxin contamination in feed ingredients and finished feed are crucial for ensuring the safety and quality of poultry feed.

Chemical contamination

The impact of chemical contaminants in poultry farming has become a public concern. These contaminants pose a potential threat to consumer health and directly impact the quality of poultry meat and food safety. The most common chemical contaminants to which poultry are exposed during the feeding cycle include veterinary products that have exceeded their expiration dates or pesticides and growth promoters from feed ingredients80. Common hormones used to promote poultry growth, such as estrogen, steroid hormone content, and growth hormone, are used to promote growth in poultry. However, residues of these hormones may lead to an increase in the fat content of the meat and changes in the muscle fiber structure, which in turn may affect the taste and nutritional value of the meat67. Angove et al. found that Yolk steroid hormones may increase the differentiation of MSCs toward the adipogenic lineage during differentiation81. Poultry are commonly exposed to contaminants from the environment during feeding, including microplastic (MP), dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and hexabromocyclodecanes (HBCDs)4. Environmental contaminants are mostly exposed from PCBs in aging and broken equipment in poultry houses, from MP in broken footbeds, and HBCDs in insulation materials82. Using pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and Agilent 8700 laser direct infrared imaging spectrometer, we found that polystyrene (PS) and polyamide are the significant types of MPs detected in chicken skeletal muscle. In vitro, results showed that polystyrene-microplastic (PS-MP) exposure induced proliferation and apoptosis but reduced differentiation of chicken primitive myoblasts, while physiological results showed that PS-MP exposure suppressed energy and lipid metabolism, induced oxidative stress, and affected skeletal muscle function by regulating genes involved in neural function and muscle development83. These results indicate that birds produced under modern intensive farming patterns are significantly more likely to be exposed to environmental pollutants than birds produced under traditional production patterns.

Heavy metal

Heavy metals are a group of metallic elements that are dense and toxic, and increased concentrations of these metals in the environment may enter poultry through the food chain, affecting their health and meat quality. In a French study on the level of chemical contamination of organic meat, several environmental contaminants (e.g., dioxins, PCBs, HBCD, Zn, Cu, Cd, Pb, and As) were detected in three animal species (bovine, porcine, and poultry), but all were below national safety limits80. Seven farms were randomly selected from five districts of Bangladesh, and meat samples were collected at all time stages of production with detectable levels of heavy metals like Chromium (Cr) and Cadmium (Cd), which were generally below the safety limits, with significant differences in the levels of Cr and Cd in different meat samples from only a single district in Dhaka and Chittagong84.

Exposure to heavy metals, such as lead and cadmium, may cause abnormal muscle texture in broilers, including hardening of the meat and reduced elasticity. In addition, heavy metal accumulation may affect the muscle color of broilers, leading to color changes and even affecting taste and texture85. Heavy metals may also negatively affect broilers’ growth performance and immune system, leading to growth restriction, reduced resistance, and increased disease incidence84. These changes may be associated with heavy metals on feed digestion and absorption, metabolic processes, and nutrient utilization, ultimately affecting broilers’ overall meat quality86. However, the appropriate addition of heavy metal-based chelates in poultry rearing can instead improve meat quality. The administration of Cu, Zn, and Fe in glycine chelates can influence the antioxidative status of thigh meat in broilers. Zn and Cu chelates have shown potential in enhancing the antioxidative stability of meat, while Fe chelates might decrease antioxidative stability due to increased malondialdehyde levels87. Using Zn, Cu, and Fe chelates can alter the fatty acid profile of thigh meat, influencing its dietary value. Zn chelates, in particular, reduced the total cholesterol content of poultry meat and affected the fatty acid content of the n − 3 fatty-acids family and the n-6 fatty acid family, showing the potential to increase the dietary value of meat88.

Feed additives

Feed additives refer to feed production and processing, the use of a small amount of material added to the process or trace substances in the feed in a small amount but the role of significance. It plays a vital role in poultry feeding, affecting the growth performance of poultry and directly affecting the characteristics of poultry meat. Common feed additives include amino acids, vitamins, fishmeal, trace elements, etc. Elevated levels of lysine in the diet may limit protein synthesis and increase the proportion of nutrients used for energy storage (including energy storage in the form of myo-glycogen), leading to a low pH value of the meat, a darker color of the breast meat, a significant decrease in L* and b*, and an increase in the curing-cooking yield (CCY)89. At the same time, feed supplemented with zinc in its organic form and amino acids (ratio 1:1), the meat showed lower levels, drip loss (1.04%), higher amounts of glucose (4.61 mmol/L), and protein (0.7%)90.

The use of seafood in poultry feed has attracted much attention because they are rich in high-quality proteins and other nutrients. Fishmeal is a brownish powder obtained from whole fish or fish by-products cooked, dehydrated, pressed, dried, and ground. Excessive use of fish oil in poultry feeds may deteriorate the organoleptic quality of meat and eggs, e.g., developing a fishy odor91. It is recommended that less than 1% fish oil and 12% fishmeal be used in poultry diets. Seaweeds are bioactive compounds that can partially replace soybean meal, maize, sorghum, and mineral salts in poultry diets as they contain high levels of micro and macronutrients, fortify chicken meat with omega-3 fatty acids, and promote growth and performance92.

Sodium butyrate (SB) and vitamin D3 (VD3) supplementation on meat quality, oxidative stability, and nutritional value of the broiler chicken. The results indicated that dietary SB decreased meat color L*, cooking loss and drip loss, free fatty acids (FFA), C14:0, C16:0, saturated fatty acids (SFA), C20:4n6, and n − 6:n3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in chicken meat, and the amino acid content was reduced with an increase in the VD3 levels93. A paired comparison test of breast meat soup for flavor assessment showed a tendency for flavor attributes aroma, umami taste, sweetness, sourness, koku taste, and chicken-like taste intensity, except bitterness, to improve94. Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the influence of feed quality on poultry meat quality.

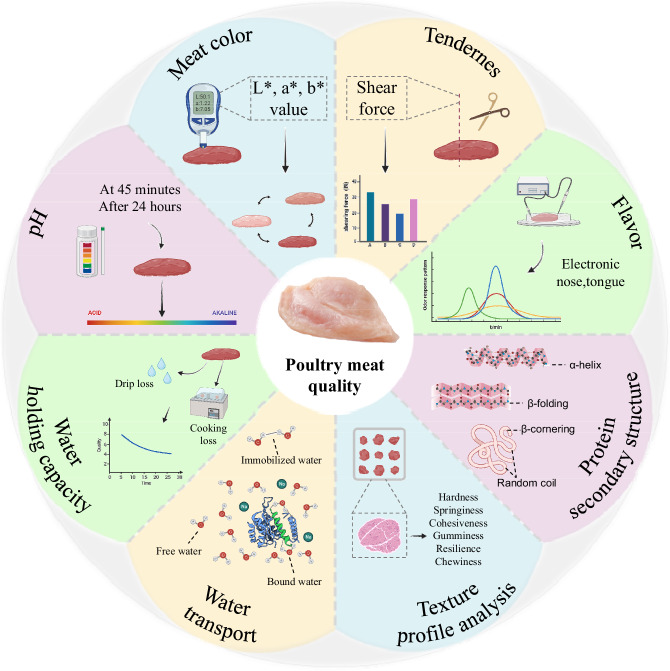

Fig. 3. Effect of feed quality on poultry meat quality.

This figure emphasizes the critical balance required in feed composition to prevent contamination while ensuring the inclusion of essential nutrients. Effective management of feed quality is crucial to avoiding detrimental substances that can impair meat quality while supplementing diets with beneficial nutrients to promote healthy growth and optimal meat yield. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint, with key elements from BioReader (https://app.biorender.com/) and Bing (https://cn.bing.com/).

Improvement strategies

Probiotics

With the increasing concern for food safety and health, optimizing poultry meat quality has become a research priority in agriculture. In this context, probiotics, as beneficial microorganisms, have attracted extensive research attention. Probiotics are a class of microorganisms that help maintain the balance and health of the host’s intestinal microbiota and have a potentially promotive effect in poultry farming95. Adding probiotics can improve poultry’s daily weight gain and feed conversion rate, enabling them to use feed more effectively and thus increase production efficiency6. Chickens fed Rhodopseudomonas palustris significantly increased daily weight gain and feed conversion ratio96. Chickens fed probiotic combinations containing Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis tended to increase body weight gain and improve feed conversion ratio. In contrast, feeds supplemented with Bacillus cereus and coumarin improved growth rate and reduced feed consumption per kilogram of living body weight gain97.

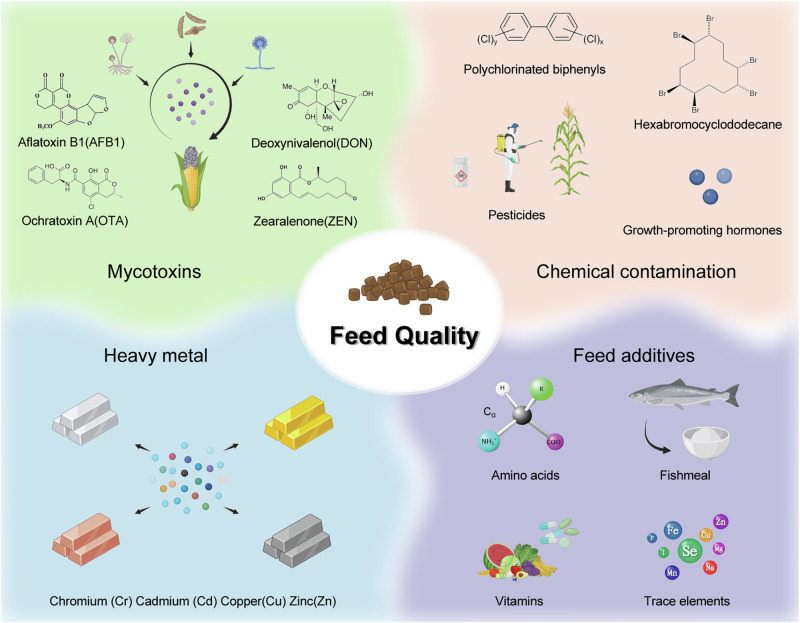

Secondly, probiotics can positively affect poultry meat quality through various mechanisms (Fig. 4). Studies have shown that Brevibacillus laterosporus S62-9 can affect the poultry muscle’s pH, meat color, and moisture retention, thereby improving the flavor and texture of the meat98. The breast meat of broilers fed Lactobacillus farciminis, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus had increased levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids) and decreased levels of saturated fatty acids99. The nutritional value of chicken meat was further enhanced by feeding probiotics. In addition, the addition of probiotics can reduce oxidative damage in meat and improve antioxidant capacity by the Nrf2-ARE pathway, resulting in more stable meat and longer shelf life100–102.

Fig. 4. Mechanisms of probiotics improve chicken meat quality.

A variety of harmful factors attack the intestinal barrier, triggering endotoxin into the bloodstream and causing inflammatory reactions through the activation of the MAPK-Nrf2-ARE pathway resulting in the occurrence of oxidative stress and thus causing deterioration of meat quality. Probiotic supplementation can inhibit the occurrence of oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions and thus improve meat quality. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint, with key elements from BioReader (https://app.biorender.com/) and Bing (https://cn.bing.com/).

Probiotics also inhibit the growth of harmful microorganisms. Probiotics can reduce the growth of harmful bacteria and maintain intestinal health through mechanisms such as competitive elimination and secretion of antimicrobial substances, thereby improving meat quality97. In a challenge with Salmonella typhimurium, chickens fed Bacillus subtilis RX7 and Bacillus subtilis B2A had an increase in the relative weight of their stomachs and a concomitant decrease in the amount of Salmonella in their intestines and feces, implying that probiotics may be able to fight pathogens by modifying the chickens’ digestive system103. The effects of specific strains on improving poultry meat quality are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effects of different bacteria on meat quality

| No. | Strains | Dosages | Position | Position | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brevibacillus laterosporus S62-9 | 1 × 109 CFU/g | Breast meat | The pH, drip loss, cooking loss, and shear force decreased; the content of volatile compounds (1-octen-3-ol and hexanal) increased by a factor of about 20. | 98 |

| 2 | Enterococcus spp., Pediococcus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus spp. | 1 × 105 CFU/g | Breast meat | Color and lipid stabilities of breast meat declined; the myofibrillar fragmentation index increased | 6 |

| 3 | Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | 1.5 × 108 CFU/g, 5 × 108 CFU/g and 3 × 108 CFU/g | Breast meat | Meat color L* and the moisture content of breast meat increased | 151 |

| 4 | L. acidophilus and S. cerevisiae | 1 × 1011 and 1 × 109 CFU/mL | Breast meat | The physical (including pH, colors, water holding capacity, drip loss, and shear force) and sensory characteristics of breast meat increased | 152 |

| 5 | Bacillus subtilis PB6 | 2 × 107 CFU/g | Breast and thigh meat | Arginine, isoleucine, and lysine of thigh meat increased; Cystienof breast meat increased | 115 |

| 6 | Enterococcus faecium | 2 × 108 CFU/g | Breast and thigh meat | Fat content in thigh and breast meat increased, and the color and water content of thigh meat and color of breast meat decreased | 153 |

| 7 | Bacillus subtulis fmbJ | 2 × 1010 CFU/kg | Breast meat | Meat color L* 24 h, b* 45 min, and b* 24 h values decreased and meat color a*24 h increased | 154 |

| 8 | Bacillus subtilis | 2 × 109 spores/g | Breast and thigh meat | pH24h value of thigh meat increased; the drip loss and the cooking loss of breast meat decreased | 155 |

| 9 | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium spp. | 1.2 × 109 CFU/mL | Breast meat | Breast meat production increased linearly with increasing probiotic dosage | 156 |

| 10 | Bacillus subtilis PB6 | 0.5 (0.5×) g/kg feed | Thigh meat | The general sensory analysis (flavor, texture, preference, and general aspect) at 5 h after slaughter increased, and pH values both 30 min and 5 h after slaughter decreased | 157 |

| 11 | Bacillus coagulans | 1 × 1011 CFU/g | Thigh meat | Meat color L* and b* increased | 158 |

| 12 | Bacillus subtilis strain fmbj | 0.3 g/kg feed | Breast meat | The pH and meat color a* decreased, but drip loss, cooking loss, shear force, meat color L*, and b* value increased | 102 |

| 13 | Bacillus subtilis KT260179 | 1 × 109 CFU/g | Breast meat | Water-holding capacity increased, and shear force decreased | 159 |

| 14 | Enterococcus faecium | 1 × 1010 CFU/g | Breast and thigh meat | The concentration of the inosine monophosphate (IMP) in the breast and thigh meat increased; meat color a* and b* of thigh meat increased | 101 |

| 15 | Rhodopseudomonas palustris | 8 × 1010 cells/mL | Breast meat | Both total and glutamic acid contents of breast meat increased, and fat content decreased | 96 |

| 16 | Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis and Clostridium butyricum | 3 × 1012 CFU/g, 4.5 × 1010 CFU/g and 3 × 109 CFU/g | Breast and thigh meat | The pH at 24 h of breast meat increased; cook loss of thigh meat decreased | 100 |

| 17 | Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis | 7 × 107 CFU/g and 4.1 × 107 CFU/g | Breast meat | Cook loss decreased | 97 |

| 18 | Lactobacillus farciminis and Lactobacillus rhamnosus | 4 g/10 kg of feed | Breast meat | Cholesterol and ω-6 fatty acid levels increased | 99 |

| 19 | Bacillus cereus | 12.6 × 103 microbial bodies/kg of feed/day | Breast meat | The chemical elements (As, B, Co, Cu, I, Li, Se, Si, and V) of breast meat decreased | 95 |

| 20 | Bacillus subtilis RX7 and Bacillus subtilis B2A | 1 × 104 CFU/mL | Breast meat | Drip loss after 1 day of storage decreased | 103 |

While adding probiotics to feed as a viable nutritional strategy has potentially positive effects on improving poultry meat quality, using probiotics in poultry feed still requires regulation to ensure their safety and efficacy. In the United States, probiotics used in animal feed must be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)104. The FDA evaluates the safety of probiotic strains and their intended use, requiring detailed documentation on the production process and quality control measures104. Regulatory frameworks may vary by country, but they generally aim to demonstrate the benefits of probiotics in improving poultry performance and meat quality, involving rigorous safety assessments to ensure no potential adverse effects on animals and humans.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that improve the health of the host by selectively stimulating the growth and activity of one or a small number of species of bacteria in a colony; a successful probiotic should stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract rather than harmful bacteria with potentially pathogenic or spoilage activity7. They are not digested in the intestinal tract of poultry but can be fermented by beneficial microorganisms in the gut, resulting in the production of short-chain fatty acids, such as acetic, propionic, and butyric acids, which are useful for intestinal health and function105. Galacto-oligosaccharides and xylo-oligosaccharides altered the proportion of microbiota in the gut at different levels, especially members of the Bacteroidetes and Solanaceae families, such as members of the genera Alistipes, Bacteroides, and Faecalibacterium. They altered the content of metabolites in the cecum that are related to flavoring substances, including eight lysophosphatidylcholines (lysopoietin PCs) and four amino acids, which increased the levels of lipase and ɑ-amylase in the blood of broilers, thus increasing the amount of flavoring substances in the meat106.

All prebiotics (injected in ovo with 0.2 mL solution containing: 3.5 mg/embryo Bi2 tos, trans-galactooligosaccharides (BI); 0.88 mg/embryo DiNovo, extract of Laminaria spp. (DN); 1.9 mg/embryo raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFO) and 0.2 mL physiological saline) increased breast meat weight and yield, as well as fiber diameter107. Saturated, polyunsaturated, and Ʊ-3 fatty acids were increased, and monounsaturated fatty acid levels were decreased in the probiotic group compared to the control group107. Furthermore, inulin can replace antibiotics as a growth promoter. It can ameliorate Clostridium perfringens-induced lipid peroxidation in breast meat and stimulate antioxidant responses without altering the physicochemical properties of the meat108. Trimmed asparagus by-products (TABP) have fructans, such as inulins and fructooligosaccharide (FOS), which are very common prebiotics with structures consisting of short-chain and non-digestible carbohydrates109. TABP supplementation had no significant effect on carcass characteristics, pH, color, and water-holding capacity, but cholesterol content, palmitic acid, oleic acid, saturated fatty acids, and monounsaturated fatty acids levels decreased with increasing TABP addition109. In particular, a TABP dose of 30 g/kg in broiler feed emerged as the best option to achieve these benefits109. As a type of soluble fiber, Gum arabic (Acacia senegal) is considered a natural source of prebiotics that intestinal microorganisms can actively ferment. Adding gum arabic to broiler diets at five concentrations (T1–T5) containing 0.12%, 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1.0% showed that Cooking loss was increased in T2–T4 and shear force was increased in T1–T5. Cohesiveness and gpringiness were increased in T2, while gumminess and chewiness were reduced in T4 and T5. Crude protein content was higher, and crude fat content was lower in T1 breast meat, but the other chemical composition was not affected by the treatments110.

As a natural and safe feed additive, prebiotics have been proven to improve the growth performance, immune function, and meat quality of poultry. With consumers’ increasing concern for food safety and health, the application of prebiotics in the poultry industry will be further promoted and developed.

Plant extracts

In recent years, the poultry industry has sought more natural and healthy feed additives to improve broilers’ growth performance and meat quality. Plants and their extracts have received much attention for their naturalness, non-toxicity, and unique bioactivities and have been recognized as potential options for improving poultry meat quality. The primary raw materials for poultry feed are corn, soybean meal, and soybeans, but direct supplementation as a daily feed ingredient through simple crushing or fermentation of plants can improve the quality of poultry meat. Supplementation of fermented mulberry leaf powder (FMLP) improves the digestion and absorption of nutrients in broiler chickens, thereby enhancing their growth performance, and increases the content of inosinic acid, total amino acids, essential amino acids, and savory amino acids in the breast and thigh muscles, and improves polyunsaturated fatty acids and essential fatty acids in the breast muscles111. Supplementation of 10% alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in the ration increased the content of inosinic acid, total amino acids, essential amino acids, non-essential amino acids, and tasty amino acids in the breast muscles112. The dietary pomegranate peel powder (PPP) significantly alleviated oxidative rancidity during storage by increasing the pH, decreasing the meat color L*, and increasing the meat color a* and b* of the breast muscles compared to the control group113.

Plant extracts are compounds or mixtures of compounds with specific biological activities extracted from plants. Commonly used methods include solvent extraction, ultrasonic extraction, microwave extraction, and enzyme extraction, while supercritical fluid extraction and microwave-assisted extraction are widely used as new extraction techniques8. These plant extracts can not only be used as an alternative to synthetic chemical additives but have also improved the growth performance and meat quality of poultry114. Thyme essential oil as a feed additive can significantly increase essential amino acids (EAAs) and other related meat quality parameters in the domestic breast muscle, thus improving the nutritional value and eating quality of poultry meat115. Trans-anethole (TA) is a volatile anise flavoring constituent of many essential oils of medicinal aromatic plants of more than 20 species (e.g., fennel, anise, and star anise)116. Dietary supplementation with TA reduced drip loss (storage for 24 and 48 h) and cooking loss in breast muscle. It also elevated higher (P < 0.05) concentrations of palmitoleic acid, soybean oil acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, ɑ-linolenic acid, and eicosatrienoic acid, in breast muscles116.

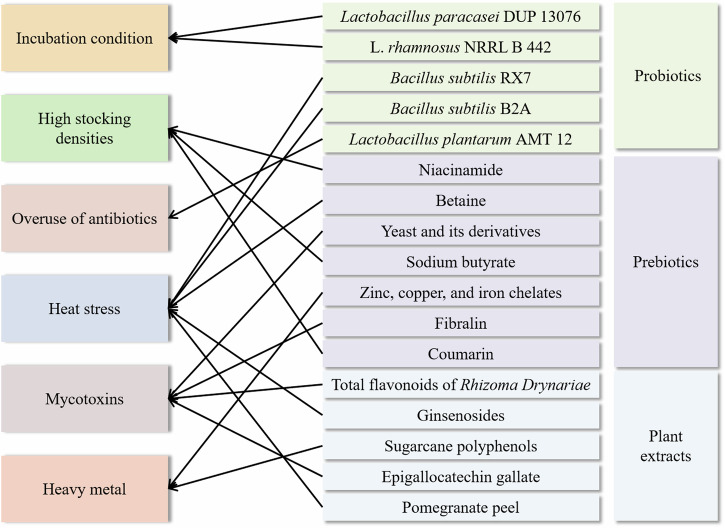

In general, plant extracts have a wide range of application prospects in poultry farming and can improve poultry meat quality in various ways. However, it should be noted that the effects of different plant extracts on poultry may differ, so further in-depth studies are needed to select suitable plant extracts and rational ratios and dosages in practical applications. In addition, scientific research and experiments are the key to evaluating the effects of plant extracts on poultry meat quality to ensure their safety and efficacy. Figure 5 supports the relationship between the considered indexes and the proposed improvement strategy. To conclude, this paper proposes improvement strategies to improve poultry meat quality and meet consumer demand for high-quality poultry meat through scientific agricultural management and quality feed selection. Future research should further explore the effectiveness of these strategies’ practical application to promote the poultry industry’s sustainable development.

Fig. 5. Relationship between the considered indexes and the proposed improvement strategy.

The figure depicts the link between various harmful factors in the poultry production environment and specific mitigation strategies through the use of probiotics, prebiotics and plant extracts. The figure uses a network of lines to connect each harmful factor to one or more interventions, illustrating that the strategy can be targeted to address and mitigate the negative impacts of the harmful factor on poultry meat quality, and highlights the nutritional strategies that can be used in poultry production to improve the overall health of poultry and the quality of the meat produced. The figure was created using Microsoft PowerPoint.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32202876), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023T160198), and the Key Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province Department of China (No. 232102111046).

Author contributions

K.Y. contributed to this work, performed the literature review, and drafted the paper. Q.Q.C. collected the literature and reviewed the text. A.S. and C.Z. contributed to the revision and editing of the paper. S.C.H. contributed to the conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, and revision and editing of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ke Yue (岳珂), Qin-Qin Cao (曹芹芹).

References

- 1.Barbut, S. & Leishman, E. M. Quality and processability of modern poultry meat. Animals12, 2766 (2022). 10.3390/ani12202766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He, Y. & Liu, C. Current situation and countermeasures of poultry industry development in China. Chin. Feed3, 91–94 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panea, B. & Ripoll, G. Quality and safety of meat products. Foods9, 803 (2020). 10.3390/foods9060803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baéza, E., Guillier, L. & Petracci, M. Review: production factors affecting poultry carcass and meat quality attributes. Animal16, 100331 (2022). 10.1016/j.animal.2021.100331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Rivas, P. A. et al. Effects of heat stress on animal physiology, metabolism, and meat quality: a review. Meat Sci.162, 108025 (2020). 10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.108025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, H. W., Yan, F. F., Hu, J. Y., Cheng, H. W. & Kim, Y. H. B. Effects of probiotics feeding on meat quality of chicken breast during postmortem storage. Poult. Sci.95, 1457–1464, (2016). 10.3382/ps/pew055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Khalaifa, H. et al. Effect of dietary probiotics and prebiotics on the performance of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci.98, 4465–4479 (2019). 10.3382/ps/pez282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding, X., Giannenas, I., Skoufos, I., Wang, J. & Zhu, W. The effects of plant extracts on lipid metabolism of chickens—a review. Anim. Biosci.36, 679–691 (2023). 10.5713/ab.22.0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collman, J. P., Boulatov, R., Sunderland, C. J. & Fu, L. Functional analogues of cytochrome c oxidase, myoglobin, and hemoglobin. Chem. Rev.104, 561–588, (2004). 10.1021/cr0206059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou, Y. et al. Effect of ultrasound assisted collagen peptide of chicken cartilage on storage quality of chicken breast meat. Ultrason Sonochem.89, 106154 (2022). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Sabry, M. I., Hassan, S. S. A., Zaki, M. M. & Stino, F. K. R. Stocking density: a clue for improving social behavior, welfare, health indices along with productivity performances of quail (Coturnix cotu rnix)-a review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod.54, 83 (2022). 10.1007/s11250-022-03083-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He, K., Sun, Q. & Tang, X. Prediction of tenderness of chicken by using viscoelasticity based on airflow and optical technique. J. Texture Stud.53, 133–145 (2021). 10.1111/jtxs.12633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner, R. D. et al. Meat tenderness: advances in biology, biochemistry, molecular mechanisms and new technologies. Meat Sci.185, 108657 (2022). 10.1016/j.meatsci.2021.108657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, X., Ha, M., Warner, R. D. & Dunshea, F. R. Meta-analysis of the relationship between collagen characteristics and meat tenderness. Meat Sci.185, 108717 (2022). 10.1016/j.meatsci.2021.108717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowker, B., Gamble, G. & Zhuang, H. Exudate protein composition and meat tenderness of broiler breast fillets. Poult. Sci.95, 133–137 (2016). 10.3382/ps/pev312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roobab, U. et al. Effect of pulsed electric field on the chicken meat quality and taste-related amino acid stability: flavor simulation. Foods12, 710 (2023). 10.3390/foods12040710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe, J. H., Choi, M. H., Rhee, M. S. & Kim, B. C. Estimation of sensory pork loin tenderness using Warner-Bratzler shear force and texture profile analysis measurements. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci.29, 1029–1036, (2016). 10.5713/ajas.15.0482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldas-Cueva, J. P., Mauromoustakos, A. & Owens, C. M. Instrumental texture analysis of chicken patties prepared with broiler breast fillets exhibiting woody breast characteristics. Poult. Sci.100, 1239–1247 (2021). 10.1016/j.psj.2020.09.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sipos, L., Nyitrai, Á., Hitka, G., Friedrich, L. F. & Kókai, Z. Sensory panel performance evaluation—comprehensive review of practical approaches. Appl. Sci.11, 11977 (2021). 10.3390/app112411977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng, S., Liu, R., Li, C., Xu, X. & Zhou, G. Meat quality and flavor compounds of soft-boiled chickens: effect of Chinese yellow-feathered chicken breed and slaughter age. Poult. Sci.101, 102168 (2022). 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Hadi, M. A., Zhang, F. J., Wu, F. F., Zhou, C. H. & Tao, J. Advances in fruit aroma volatile research. Molecules18, 8200–8229, (2013). 10.3390/molecules18078200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heimbuch, M. L. et al. Evaluation of growth, meat quality, and sensory characteristics of wool, hair, and composite lambs. J. Anim. Sci.101, 1–12 (2023). 10.1093/jas/skad076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayasena, D. D. et al. Comparison of quality traits of meat from Korean native chickens and broilers used in two different traditional Korean cuisines. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci.26, 1038–1046 (2013). 10.5713/ajas.2012.12684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gai, K. et al. Identification of key genes affecting flavor formation in Beijing-you chicken meat by transcriptome and metabolome analyses. Foods12, 1025 (2023). 10.3390/foods12051025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Liu, X. et al. Differential proteome analysis of breast and thigh muscles between Korean native chickens and commercial broilers. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci.25, 895–902 (2012). 10.5713/ajas.2011.11374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, Y. et al. A fluorescent pH probe for evaluating the freshness of chicken breast meat. Food Chem.384, 132554 (2022). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beauclercq, S. et al. Divergent selection on breast meat ultimate pH, a key factor for chicken meat quality, is associated with different circulating lipid profiles. Front. Physiol.13, 935868 (2022). 10.3389/fphys.2022.935868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mir, N. A., Rafiq, A., Kumar, F., Singh, V. & Shukla, V. Determinants of broiler chicken meat quality and factors affecting the m: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol.54, 2997–3009 (2017). 10.1007/s13197-017-2789-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Njoga, E. O. et al. Pre-slaughter, slaughter and post-slaughter practices of slaughterhouse workers in Southeast, Nigeria: Animal welfare, meat quality, food safety and public health implications. PLoS ONE18, e0282418 (2023). 10.1371/journal.pone.0282418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang, J. & Xiong, Y. L. Natural antioxidants as food and feed additives to promote health benefits and quality of meat products: a review. Meat Sci.120, 107–117 (2016). 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luong, N. M. et al. A Bayesian approach to describe and simulate the pH evolution of fresh meat products depending on the preservation conditions. Foods11, 1114 (2022). 10.3390/foods11081114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, Y., Xiong, D., Yao, L. & Zhao, C. An SNP in exon 11 of Chicken 5’-AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Gamma 3 subunit gene was associated with meat water holding capacity. Anim. Biotechnol.27, 13–16 (2016). 10.1080/10495398.2015.1069300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oswell, N. J., Gilstrap, O. P. & Pegg, R. B. Variation in the terminology and methodologies applied to the analysis of water holding capacity in meat research. Meat Sci.178, 108510 (2021). 10.1016/j.meatsci.2021.108510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szmańko, T., Lesiów, T. & Górecka, J. The water-holding capacity of meat: a reference analytical method. Food Chem.357, 129727 (2021). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowker, B. & Zhuang, H. Relationship between water-holding capacity and protein denaturation in broiler breast meat. Poult. Sci.94, 1657–1664 (2015). 10.3382/ps/pev120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yue, K. et al. Novel insights into total flavonoids of rhizoma drynariae against meat quality deterioration caused by dietary aflatoxin B1 exposure in chickens. Antioxidants12, 83 (2023). 10.3390/antiox12010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun, X. et al. Low-field NMR analysis of chicken patties prepared with woody breast meat and implications to meat quality. Foods10, 2499 (2021). 10.3390/foods10102499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing, T. et al. Influence of transport conditions and pre-slaughter water shower spray during summer on protein characteristics and water distribution of broiler breast meat. Anim. Sci. J.87, 1413–1420 (2016). 10.1111/asj.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katemala, S., Molee, A., Thumanu, K. & Yongsawatdigul, J. Meat quality and Raman spectroscopic characterization of Korat hybrid chicken obtained from various rearing periods. Poult. Sci.100, 1248–1261 (2021). 10.1016/j.psj.2020.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, Z., Bertram, H. C., Böcker, U., Ofstad, R. & Kohler, A. Myowater dynamics and protein secondary structural changes as affected by heating rate in three pork qualities: a combined FT-IR microspectroscopic and 1H NMR relaxometry study. J. Agric. Food Chem.55, 3990–3997 (2007). 10.1021/jf070019m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang, K. et al. Low frequency magnetic field plus high pH promote the quality of pork myofibrillar protein gel: a novel study combined with low field NMR and Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem.326, 126896 (2020). 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, Y. H. et al. The role of incubation conditions on the regulation of muscle development and meat quality in poultry. Front. Physiol.13, 883134 (2022). 10.3389/fphys.2022.883134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Musawi, S. L., Stickland, N. C. & Bayol, S. A. In ovo temperature manipulation differentially influences limb musculoskeletal development in two lines of chick embryos selected for divergent growth rates. J. Exp. Biol.215, 1594–1604 (2012). 10.1242/jeb.068791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piestun, Y. et al. Thermal manipulations during broiler embryogenesis: effect on the acquisition of thermotolerance. Poult. Sci.87, 1516–1525, (2008). 10.3382/ps.2008-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Givisiez, P. E. N. et al. Chicken embryo development: metabolic and morphological basis for in ovo feeding technology. Poult. Sci.99, 6774–6782 (2020). 10.1016/j.psj.2020.09.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]