Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)‐derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) have shown anti‐inflammatory potential in multiple inflammatory diseases. In the March 2022 issue of the Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, it was shown that EVs from human MSCs can suppress severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) replication and can mitigate the production and release of infectious virions. We therefore hypothesized that MSC‐EVs have an anti‐viral effect in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in vivo. We extended this question to ask whether also other respiratory viral infections could be treated by MSC‐EVs. Adipose stem cell‐derived EVs (ASC‐EVs) were isolated using tangential flow filtration from conditioned media obtained from a multi‐flask cell culture system. The effects of the ASC‐EVs were tested in Vero E6 cells in vitro. ASC‐EVs were also given i.v. to SARS‐CoV‐2 infected Syrian Hamsters, and H1N1 influenza virus infected mice. The ASC‐EVs attenuated SARS‐CoV‐2 virus replication in Vero E6 cells and reduced body weight and signs of lung injury in infected Syrian hamsters. Furthermore, ASC‐EVs increased the survival rate of influenza A‐infected mice and attenuated signs of lung injury. In summary, this study suggests that ASC‐EVs can have beneficial therapeutic effects in models of virus‐infection‐associated acute lung injury and may potentially be developed to treat lung injury in humans.

Keywords: acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, adipose stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles, H1N1, mesenchymal stem cells, SARS‐CoV‐2

1. INTRODUCTION

In the 2022 March issue of the Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, S. Chutipongtanate et al. reported that extracellular vesicles (EVs) from human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can suppress severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) replication and mitigate the production and release of infectious virions (Chutipongtanate et al., 2022), which suggests that MSC EVs have direct effects on viral infection. Furthermore, a recent blinded and placebo‐controlled clinical study showed improvement in lung injury parameters in severe COVID‐19 disease (Lightner et al., 2023).

In the present report, we investigated the efficacy of adipose‐tissue MSC‐derived EVs (ASC‐EVs) in both SARS‐CoV‐2 and H1N1 influenza infection in vivo. Both of these viruses are known to cause severe infections in humans, and in some cases, they can cause both cytokine storms and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Daemi et al., 2021). Although most influenza pandemics can be at least partly controlled by vaccines and antiviral therapy, the unprecedented coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic is still ongoing and continues to cause severe disease, including cytokine storms and ARDS, primarily in unvaccinated individuals (Vo et al., 2022). Vaccines and antiviral therapy have not yet been successful in controlling the pandemic, and there is a need for additional therapeutic modalities to treat severe inflammation induced by respiratory viruses (The U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2020). MSC‐EVs are known to have tissue regenerative and anti‐inflammatory functions, including roles in inflammatory respiratory diseases (Huang et al., 2022; Pattanapanyasat, K. et al, 2022, WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium, 2021). Therefore, we hypothesized that adipose tissue MSC‐EVs have anti‐inflammatory effects in severe viral respiratory infections.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Kits and reagents

The kits and reagents used in this study were purchased from the following sources: Minimum Essential Medium (MEM)‐α, foetal bovine serum (FBS), gentamycin, Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) and trypsin‐ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Trypsin‐EDTA) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Grand Island, NY, USA); normal immunoglobulin G and phycoerythrin‐conjugated antibodies for a cluster of differentiation CD9, CD63 and CD81 were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA); enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for calnexin was from LSBio (Seattle, WA, USA); ELISA for TSG101 and cytochrome C was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) or R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA); the 500‐kDa molecular weight cut‐off filter membrane cartridge was from GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA); and the Hybrid‐R RNA purification kit was from GeneAll (Seoul, South Korea).

2.2. Cell culture

A human ASC cryostock at passage four was prepared as described previously and was stored in liquid nitrogen until use (Lee et al., 2020). Frozen cells were thawed at 37°C, plated at a density of 3000 cells/cm2, and cultured in MEM‐α containing 10% FBS and 0.1% gentamycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). ASCs were maintained until they reached confluence and were characterized for surface marker expression and tri‐lineage differentiation potential according to the criteria described by the International Society of Cellular Therapy (Börger et al., 2020).

Vero E6 cells (CRL‐1586, American Type Culture Collection; ATCC) were cultured in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin‐streptomycin, 1% L‐glutamine (200 nM), 1% sodium pyruvate (100 nM) and nonessential amino acids. All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. The cell viability and cell size were monitored using an automated cell counter with trypan blue staining.

2.3. Isolation of ASC‐EVs

To obtain ASC‐conditioned media (CM), a vial of ASC stock was thawed and sub‐cultured with gradually increasing culture scales in T175 flasks and a one or two‐layered cell factory (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) prior to passage 7. At passage 7, the ASCs were plated at a density of 6000 cells/cm2 in 10‐layered cell factories and cultured up to 90% confluence in MEM‐α containing 10% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The FBS was heat‐inactivated (56°C for 30 min) before being added to the cell culture. The ASCs were washed three times with DPBS to remove residual FBS and were supplemented with serum‐free and phenol‐red‐free MEM‐α. The cells were further incubated in an FBS‐free medium for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 before the CM was collected (Lee et al., 2020).

ASC‐EVs (ASCE™ is the proprietary trademark of ExoCoBio Inc.) were isolated from ASC‐CM using tangential flow filtration (TFF)‐based ExoSCRT™ technology as previously described (Lee et al., 2020). Briefly, to remove larger non‐exosomal particles, including cells, cell debris, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies, the ASC‐CM was filtered through a 0.22‐µm polyethersulfone membrane filter (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and then concentrated using TFF with a 500 kDa molecular weight cut‐off filter. The concentrated ASC‐CM was further dialyzed with appropriate volumes of buffer to remove non‐exosomal proteins, nutrients and cellular waste products such as lactate and ammonia. Isolated ASC‐EVs were stored in small aliquots at −80°C in sterile polypropylene tubes. Frozen ASC‐EVs were thawed at 4°C until further use.

ASC‐EVs were characterized according to the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018) as recommended by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (Théry et al., 2018). Nanoparticle tracking analysis was performed using Zetaview (Particle Metrix, Meerbusch, Germany) as described previously (Lee et al., 2020). Transmission electron microscopy analysis, flow cytometry analysis and protein quantification were performed as previously described (Shin et al., 2020). ELISAs for TSG101, calnexin and cytochrome C were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Figure S1).

2.4. Quantitative of miRNAs and IFITM3

Total RNAs were extracted from ASC‐EVs using QIAzol lysis reagent (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (QIAGEN). To normalize for technical variation, 0.16 fmol of synthetic cel‐miR‐39‐3p (QIAGEN) was spiked into the ASC‐EVs sample after the addition of a denaturing solution. The quality and quantity of the miRNAs were assessed using a spectrophotometer (DS‐11/DeNovix, Wilmington, DE, USA). Four miRNAs were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2.0 µL of template RNAs were reverse‐transcribed using miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Assay (QIAGEN), and then qPCR was performed using miRCURY LNA SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN). The miRNA primers (miR‐181a‐5p, miR‐92a‐3p, miR‐23a‐3p, miR‐103a‐3p, miR‐26a‐5p) from miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Assays (QIAGEN) were used. Analysis was performed using QuantStudio 3 Real‐time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) to quantify the amount of miRNA. Relative expression levels were normalized to spike in, cel‐miR‐39‐3p and calculated using the standard curve methods. The quantification of IFITM3 (interferon‐induced transmembrane protein 3) in ASC‐EVs was evaluated in an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit following the manufacturer's instructions (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA). The IFITM3 contents were measured using a microplate spectrophotometer at 450 nm (SpectraMax i3X, Molecular Devices, California, USA).

2.5. H1N1 influenza A virus

Influenza A/Puerto Rico/08/1934 (H1N1) was used to model highly pathogenic human influenza A virus infection. All experiments were performed under animal biosafety level 2 (ABL‐2) conditions at Knotus Co., Ltd. (Incheon, South Korea).

2.6. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in vitro

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2; BetaCoV/Korea/KCDC03/2020, NCCP43326) was used to model highly pathogenic human SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Virus stocks were grown and propagated in Vero E6 cells and were titrated using the plaque assay and the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay. All experiments were performed under animal biosafety level 3 (ABL‐3) conditions at the Korea Zoonosis Research Institute (KoZRI) of Jeonbuk National University (Jeollabuk‐do, South Korea).

2.7. Cellular uptake assay

For fluorescent labelling of the ASC‐EVs, the PKH67 Green Fluorescent Cell Linker Mini Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. After ASC‐EVs were fluorescently labelled, they were purified using an MW3000 Exosome spin column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove the unlabelled dye. The labelled ASC‐EVs were then incubated with Vero E6 cells. During incubation, cellular uptake of labelled ASC‐EVs was monitored using the IncuCyte S3 live cell imaging system (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.8. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the ASC‐EVs on Vero E6 cells was determined using the 3‐[4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl]−2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) or CCK‐8 (Dojindo, MD, USA) assays. For the MTT assay, Vero E6 cells (1 × 104 cells/mL) were seeded in 96‐well cell culture plates followed by treatment with different concentrations (2‐fold serial dilutions) of ASC‐EVs in triplicate. After 48 and 96 h of incubation, 50 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) in PBS was added to each well and further incubated for 4 h at 37°C until formazan crystals were formed. The supernatant was aspirated and the formazan crystals produced by metabolically active cells were dissolved in 100 µL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Spectra Max i3x, Molecular Devices Inc., CA, USA), then the absorbance value was converted to determine the percentage of living cells.

2.9. In vitro antiviral activity assays

For Vero E6 cells, 1 × 104 cells/mL were seeded into 96‐well plates and incubated overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Subsequently, the culture medium was removed from each well, and 101−102 TCID50 of SARS‐CoV‐2 (50 µL suspension) and different concentrations of ASC‐EVs (50 µL) were added to each well. For the virus control, 101−103 TCID50 of the virus plus the highest concentration of DMSO were added to six wells. In addition, six wells were treated with DMSO alone (negative control). The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and cytotoxicity was monitored for up to 3 days post‐infection.

2.10. SARS‐CoV‐2 plaque assay

Vero E6 cells (1 × 104 cells/mL) were seeded into 96‐well plates and incubated overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Then, 10‐fold serial dilutions (101, 102 and 103 TCID50) of SARS‐CoV‐2 stock and 2‐fold serial dilutions (5.0 × 109, 2.5 × 109, 1.25 × 109, 0.625 × 109, 0.31 × 109 and 0.15 × 109 particles/100 µL) of ASC‐EVs were added to triplicate wells to a final volume of 0.2 mL/well. After 48 or 72 h, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 200 µL of 4% formaldehyde solution for 15 min, and stained with 0.4% crystal violet. The wells were inspected for viral presence, as determined by the appearance of cytopathic effects (CPE). The viral endpoint titration (the dilution required to infect 50% of the wells) was expressed as TCID50/mL. CPE (%) was calculated along with the virus titer (number of positive wells/total number of wells × 100). The mean of the positive area on plaque‐staining cells was analyzed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) in a total of four wells.

2.11. Experimental Syrian hamster model of SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced acute lung injury (ALI)

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Approval No. KNOTUS IACUC 21‐KE‐044) and was performed according to the Animal Experimentation Policy of KoZRI (Jeonbuk National University, Jeollabuk‐do, Korea). Seven‐week‐old female Syrian hamsters (RjHan: AURA) were obtained from Janvier Labs (Saint‐Berthevin, France) and kept under controlled environmental conditions (temperature, 23 ± 3°C; relative humidity, 55 ± 15%; ventilation, 10−20 air changes/h and luminous intensity, 150−300 lux) with a 12 h light‐dark cycle in the experimental animal facility at KoZRI of Jeonbuk National University.

ALI was induced by intranasal inoculation with 200 µL of 104 TCID50 of SARS‐CoV‐2 (NCCP43326). 24 h after infection, the vehicle control or ASC‐EVs were intravenously administered once a day for 4 days through the tail vein. The amount of ASC‐EVs per injection was 3.0 × 109 or 1.0 × 1010 particles/200 µL (corresponding to 20.3 and 67.9 µg of protein, respectively) per head. The body weights of the hamsters were recorded every day until 7 days post‐infection.

2.12. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of the SARS‐CoV‐2–infected Syrian hamster lungs

The hamsters were sacrificed on day 5 or 7 post‐infection, and the lungs were harvested and the most visibly infected lesion of each lobe was used for analysis. The lungs were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, sectioned longitudinally in the bronchial region, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The lung tissue sections were assigned a score as follows: 0, no pathological manifestations; 1, affected area ≤ 10%; 2, affected area between 10% and 50% and 3, affected area ≥ 50%; an additional point was added when pulmonary edema and/or alveolar haemorrhage was observed (Imai et al., 2020; Kulkarni et al., 2022). Total inflammatory cell counts were determined from these images at 400× magnification (Olympus BX53, Tokyo, Japan) in three randomly selected regions per H&E‐stained lung tissue section.

For immunohistochemical staining of the lung tissue sections, citrate buffer was used for antigen retrieval, followed by incubation with anti‐interleukin (IL)−1β (1:200 dilution, NB600‐633 Novus Biological, LLC, USA) and N protein (1:200 dilution, NB10056576, Novus Biological LLC, USA) antibodies. After sequential incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies, the slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Dako, CA, USA). The signal intensity of immunohistochemical staining was further quantified using Zen 2.3 blue edition software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Thüringen, Germany), and the area of positivity was presented as the percentage of the total tissue area.

2.13. Experimental mouse model of H1N1 influenza A virus‐induced ALI

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC Approval No. KNOTUS IACUC 20‐KE‐457) and was performed according to the Animal Experimentation Policy of Knotus Co., Ltd. Six‐week‐old female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Orient Bio (Seongnam, Gyonggi‐do, Korea) and maintained under controlled environmental conditions (temperature, 23 ± 3°C; relative humidity, 55 ± 15%; ventilation, 10−20 air changes/h; and luminous intensity, 150−300 lux) with a 12‐h light‐dark cycle in the experimental animal facility at Knotus Co., Ltd.

ALI was induced by intranasal inoculation with 50 µL of 1 LD50 of influenza A/Puerto Rico/08/1934 (H1N1). After infection, vehicle control or ASC‐EVs were administered intravenously once a day for 3 or 4 days at a flow rate of 1 mL/min through the tail vein. The amount of ASC‐EVs per injection was 1.0 × 1010 particles per mouse (equivalent to 67.9 µg of protein). Survival, body weight, body temperature and clinical signs of disease were monitored daily for 14 days. A loss of body weight of 20% was considered a surrogate for death, and the mice were sacrificed if this occurred. Clinical scores were evaluated daily using the following method: (1) slightly ruffled fur, (2) ruffled fur and reduced mobility, (3) ruffled fur, reduced mobility and rapid breathing, (4) ruffled fur, reduced mobility, huddled appearance and rapid and/or laboured breathing indicative of pneumonia and (5) death (Mansell & Tate, 2018). The daily clinical scores were added for each mouse and averaged across the groups.

2.14. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses of the H1N1 influenza A virus‐infected C57BL/6 mice lungs

C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed at 9 days post‐infection, the lungs were harvested and the visibly most infected lesion of each lobe was used for analysis, followed by fixation in neutral buffered formalin. Fixed lungs were sectioned longitudinally in the bronchial region and stained with H&E. The sections were scored in an unbiased fashion from 0 to 3. Score 0 was defined as no pathological change, while scores 1, 2 and 3 corresponded to the presence of inflammation involving <25%, 25%−50% and >50% of the lung parenchyma, respectively (Kulkarni et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019). Sections were scored by two blinded readers resulting in a percentage of pathological scores. Total inflammatory cell counts were determined from these images at 400× magnification (Olympus BX53, Tokyo, Japan) in three randomly selected regions per H&E‐stained lung tissue section.

For immunohistochemical staining of the lung tissue sections, citrate buffer was used for antigen retrieval, followed by incubation with anti‐interleukin (IL)−1β (1:200 dilution, ab9722, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti‐IL‐6 (1:100 dilution, orb6210, Biorbyt, San Francisco, CA, USA), anti‐tumour necrosis factor‐α (1:50 dilution, ab1793, Abcam), interferon‐γ (1:50 dilution, MM700, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and IL‐10 (1:100 dilution, ab189392, Abcam) antibodies. After subsequent incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies, the slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Dako, CA, USA). The signal intensity of immunohistochemical staining was further quantified using Zen 2.3 blue edition software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Thüringen, Germany), and the area of positivity was presented as the percentage of the total tissue area.

2.15. RNA extraction and quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction

To identify SARS‐CoV‐2–specific gene expression in Vero E6 cells or lung tissue lesions, total RNA was extracted using a Hybrid‐R RNA purification kit (GeneAll, Seoul, South Korea). Following this, 100 ng/µL RNA was used for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction to identify SARS‐CoV‐2–specific gene expression using the Allplex 2019‐nCOV assay kit (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea). The relative expressions of the E gene (FAM), RdRP gene (CalRed 610) and N gene (Cy5) were analyzed by the comparative threshold cycles method and normalized to the SARS‐CoV‐2–infected group (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001).

2.16. Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical differences were analyzed using a one‐way analysis of variance with Dunnett's multiple‐comparison test for comparisons of more than three groups and the Mann–Whitney U‐test for nonparametric analysis between two groups using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

This study sought to determine the effects of ASC‐EVs on the in vitro and in vivo replication of SARS‐CoV‐2 during infection. To understand whether any general anti‐infective function could be maintained by ASC‐EVs, we also tested their in vivo therapeutic effects on H1N1 influenza infection. EVs were derived from adipose tissue‐derived MSCs cultured in a cell factory as previously described (Lee et al., 2020), which allows for relatively large‐scale production of ASC‐EVs. EVs were isolated from FBS‐free MSC cell culture medium 48–72 h after cell clearance and were concentrated and purified using TFF as described in detail in the Supplementary Information (Lee et al., 2020). EV characteristics are described in Figure S1. The antiviral effect of ASC‐EVs on SARS‐CoV‐2 was tested in vitro using Vero E6 cells. Furthermore, ASC‐EVs were tested in vivo in Syrian hamsters exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 (wild‐type virus variant) and in mice exposed to the H1N1 influenza virus.

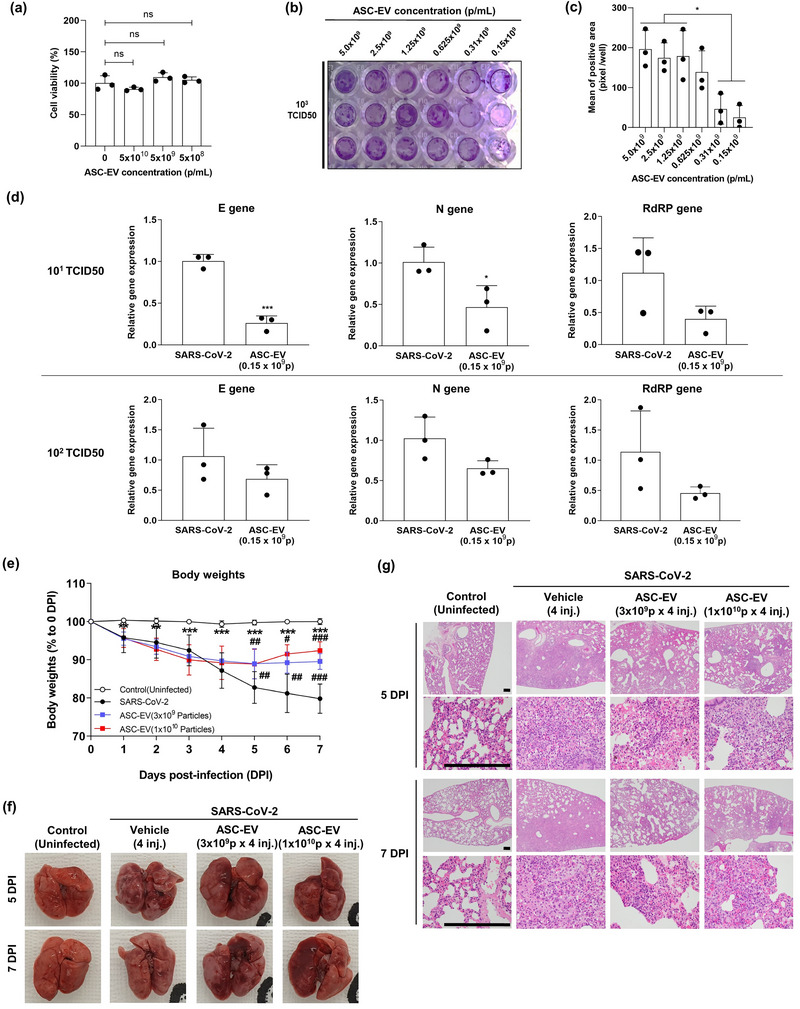

Vero E6 cells express the angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is a viral entry path for SARS‐CoV‐2 (Lu et al., 2008), and these cells were used to test the effects of ASC‐EVs. Treatment with three ASC‐EV doses of up to 5 × 109 particles/mL did not show any signs of cytotoxicity in Vero E6 cells for up to 96 h (Figure 1a). We then tested whether the ASC‐EVs affected the cytopathic effects and replication of SARS‐CoV‐2. Cells were treated with increasing titers of the virus and increasing concentrations of ASC‐EVs for 48 or 72 h. Cytopathic effects were observed at a virus titer of 103 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50), and ASC‐EV treatment (0.15 × 109/mL to 5 × 109 particles/mL) attenuated this effect, reflecting the antiviral activity of the ASC‐EVs against SARS‐CoV‐2 (Figure 1b,c). These findings are similar to the results obtained by Chutipongtanate et al. using umbilical cord‐derived MSC‐EVs (Chutipongtanate et al., 2022). The expression levels of SARS‐CoV‐2–specific genes, namely, the E, RdRP and N genes, were directly attenuated by ASC‐EVs (1 × 1010 particles/mL) at viral titers of 101 TCID50 and 102 TCID50 (Figure 1d).

FIGURE 1.

Anti‐viral effects of ASC‐EVs against SARS‐CoV‐2. (a) The effects of ASC‐EVs on cell viability of Vero E6 cells. Vero E6 cells were treated with ASC‐EVs, and after 24 h a CCK‐8 assay was performed to determine the viability of the cells. (b) Plaque assay of SARS‐CoV‐2–induced cell death. Vero E6 cells were treated with SARS‐COV‐2 (103 TCID50/well) + ASC‐EVs (from 0.15 × 109 to 5.0 × 109 particles/mL) and the CPEs were evaluated from 72 h after infection. (c) The mean plaque reduction in Vero E6 cells with increasing concentrations of ASC‐EVs (n = 3). (d) The relative expression of SARS‐CoV‐2–specific genes (E, RdRP and N) was measured using quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (the top three figures show data for 101 TCID50, and the lower three figures show data for 102 TCID50. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments; ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 compared to SARS‐CoV‐2 (101 TCID50) + ASC‐EVs; ### p < 0.001 compared to SARS‐CoV‐2 (102 TCID50) + ASC‐EVs. (e) Body weight of Syrian hamsters exposed to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with virus inoculated on day 0. All animals survived throughout the experiment (n = 8). (f) Photograph of the Syrian hamster lungs 7 days after induction of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Fewer spots of bleeding and reduced overall redness were observed in animals treated with ASC‐EVs. (g) Micrographs of Syrian hamster lung sections at 5 or 7 days after the induction of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. ASC‐EVs increased the area of apparent alveoli and reduced cellularity. The scale bar is 250 µm. DPI, days post‐infection. Magnification is 40× (first and third row) and 400× (second and fourth row).

We tested whether ASC‐EV treatment reduced any signs of infection in vivo in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected Syrian hamsters. Intranasal challenge with SARS‐CoV‐2 (200 µL of 104 TCID50 of wild‐type SARS‐CoV‐2) resulted in weight loss in the animals during the study period; however, all the animals survived. Four daily intravenous injections of 3 × 109 or 1 × 1010 particles/mL ASC‐EVs versus vehicle (protocol shown in Figure S2a) reduced body weight loss (Figure 1e). From 5 days post‐infection, ASC‐EV therapy was associated with body weight recovery of the infected hamsters, seemingly dose‐dependently at day 7 (Figure 1e). Examination of the lungs showed detectable discoloration and focal red lesions in infected hamsters, and ASC‐EVs significantly reduced the pathology score (Figure 1f). Furthermore, H&E histological analysis showed that the accumulation of inflammatory cells and the thickening of alveolar septa were reduced by ASC‐EVs in infected mice (Figure 1g). Altogether, these findings demonstrated the in vitro and in vivo antiviral activity of ASC‐EVs against SARS‐CoV‐2 (Figure 1). We do not have direct evidence of an EV‐mediated mechanism for the antiviral effects observed. However, a qPCR analysis identified five potentially antiviral miRNAs (miR‐181a‐5p, miR‐92a‐3p, miR‐23a‐3p, miR‐103a‐3p, miR‐26a‐5p) in the ASC‐EVs (Figure S1g). Further, we could also identify the potentially anti‐viral protein IFITM3 in the ASC‐EVs (Figure S1h).

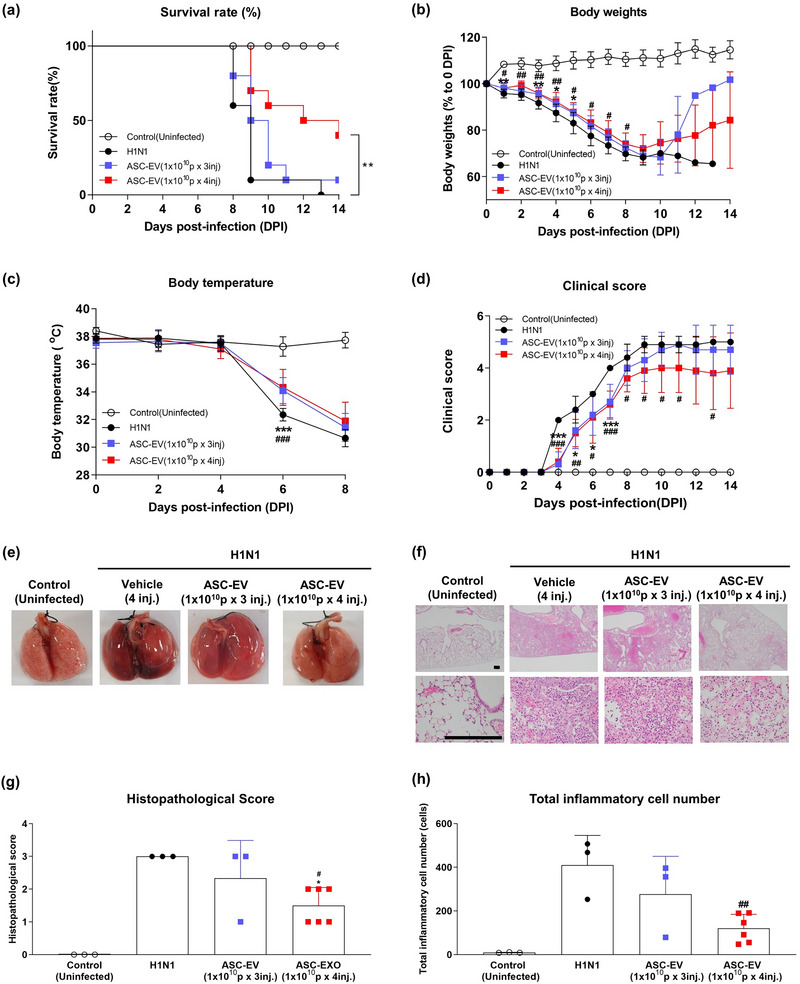

To test whether ASC‐EVs exhibited similar anti‐viral effects against other viruses, we used a mouse model of H1N1 influenza A virus infection (Bouvier et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2020). Intranasal challenge of mice with H1N1 influenza A virus (50 µL of one median lethal dose (LD50) of influenza A Puerto Rico 08/1934 H1N1) resulted in respiratory distress, inflammation and death, and 3−4 daily intravenous injections of 1 × 1010 particles/mL ASC‐EVs or vehicle (protocol shown in Figure S3a) resulted in a prolonged survival rate from day 9 post‐infection (Figure 2a). Treatment also resulted in a significant reduction in the loss of body weight (Figure 2b) and an improvement in body temperature up to day 8, which was prior to the death of any animal (Figure 2c) (Rogers et al., 2020). The trends for reduced body weight loss were also seen in surviving animals treated with ASC‐EVs beyond day 9; however, these data were inconclusive because only a few mice survived the infection beyond that day. The clinical score of the infection is shown in Figure 2d and was significantly reduced in the mice treated with four injections of ASC‐EVs. Histopathological changes in the lungs, including edema and areas of dark‐coloured haemorrhage, were reduced in mice treated with ASC‐EVs (Figure 2e). These results also indicate reduced edema and haemorrhage, indicating the protective effects of ASC‐EVs at 9 days post‐infection (Figure 2e). Furthermore, H&E histological analysis indicated that the accumulation of inflammatory cells was reduced by ASC‐EVs in the infected mice (Figure 2f). The histopathological scores and inflammatory cell numbers are shown in Figure 2g,h, and the data indicate a significant improvement with four injections of ASC‐EVs. Figures S2b,c and S3b,c show the presence of cytokines (IL‐1b for SARS‐CoV‐2–infected Syrian hamsters and IL‐1b, IL‐6, TNF‐a, IFN‐g and IL‐10 for H1N1‐infected mice) by immunohistochemistry of lung tissues in the two animal models, implying a significant reduction in cytokine expression, but also showing that the treatment did not fully block cytokine production. Overall, these results indicate a potential beneficial therapeutic effect of ASC‐EVs in H1N1 influenza A virus‐induced acute lung injury in vivo (Figure 2). The expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 genes such as the E, RdRP and N genes are shown in Figure S2d, and these were significantly reduced in ASC‐EV–treated Syrian hamsters.

FIGURE 2.

Anti‐viral effects of ASC‐EVs against H1N1 influenza A virus. (a) Kaplan–Meier survival plot for mice infected with H1N1 virus on day 0. Treatment with higher numbers of intravenous injections of ASC‐EVs reduced mortality (red curve). Mice that lost more than 20% of their body weight were sacrificed and recorded as death. Only a few mice in the ASC‐EV group survived after H1N1 infection in the experiment (n = 11). (b) Body weight of mice infected with H1N1 virus on day 0. The mice that survived the infection beyond day 10 recovered their body weight (no statistical analysis was performed). (c) Body temperature up to day 8 in mice infected with H1N1 virus on day 0. Treatment with ASC‐EVs significantly reduced the drop in body temperature on day 6. (d) Clinical score up to day 14 in mice infected with H1N1 virus on day 0. Treatment with ASC‐EV four times intravenously significantly improved the clinical score. (e) Macroscopic photographs of mouse lungs post‐mortem after H1N1 virus infection on day 0 versus controls. The lungs of mice treated with vehicle appeared dark red with spots of bleeding, whereas the ASC‐EV treatment reduced this morphology. (f) Representative micrographs (H&E staining) of lungs from the different groups infected with the H1N1 virus and treated with ASC‐EVs. The scale bar is 250 µm. DPI, days post‐infection. (g) Post‐mortem histopathological scores of peribronchiolar, perivascular and parenchymal lung tissue in mice infected with H1N1 virus on day 0 and treated with vehicle or ASC‐EVs with two different treatment regimens. (h) Quantification of total inflammatory cells in H1N1‐infected mouse lung tissue.

4. DISCUSSION

MSCs from various sources, including ASCs, bone marrow MSCs and umbilical cord MSCs, convey both anti‐inflammatory and regenerative functions in numerous inflammatory diseases and in different organs, including the lungs (Matthay et al., 2019; Shu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). Importantly, EVs derived from MSCs from different sources such as umbilical cord or adipose tissue show efficacy in multiple experimental inflammatory models. However, it should be noted that MSCs from different donors can confer different degrees of anti‐inflammatory and regenerative activity, which is why batch‐to‐batch stability must be carefully considered. Although there is inadequate published data in experimental animals, multiple clinical tests are currently being performed or are being planned using MSCs or their EVs to treat COVID‐19. As of July 2023, there were more than 26 active and recruiting studies and 23 completed clinical trials of MSCs against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, reflecting the great interest in using MSCs for the treatment of COVID‐19 (https://clinicaltrials.gov). Five of these have resulted in peer‐reviewed publications (Dilogo et al., 2021; Ercelen et al., 2021; Hashemian et al., 2021; Karyana et al., 2022; Kouroupis et al., 2021; Lanzoni et al., 2021; O'Brien et al., 2021; Rebelatto et al., 2022; Saleh et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2022; Turan et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021), and the key finding is that MSC cells and their EVs appear to be safe in these patient groups; however, data on their efficacy is still unclear, primarily because most of these studies were not placebo controlled. Importantly, the National Institutes of Health has discouraged the use of MSCs in patients outside of clinical trials https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/cell‐based‐therapy/ (Liang et al., 2021; Pereira Chilima et al., 2018). EVs may provide a more practical alternative to MSC therapy because they are easier to store and transport (Sengupta et al., 2020). Still, clinical trials of MSC‐EVs in severe COVID‐19 or ARDS are complicated to perform and will provide conclusive results only if they are well designed in terms of size, inclusion criteria, and outcome measures (Börger et al., 2020).

In this study, we have demonstrated that ASC‐EVs effectively prevent lung injury induced by both SARS‐CoV‐2 and H1N1 influenza A virus in two separate animal models. For SARS‐CoV‐2, the in vivo findings are paralleled with the documented in vitro antiviral effects. Previous studies have delineated the specific antiviral effects of MSC‐EVs, primarily in vitro (Lightner et al., 2023; Oh et al., 2022; Park et al., 2021). The exact mechanism explaining the anti‐viral effects of the ASC‐EVs has not been delineated, but five possibly anti‐viral miRNAs and the anti‐viral IFITM3 protein are present in the EVs (Park et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2015). Importantly, iv administration of MSC‐EV in an LPS‐associated ALI model shows lung accumulation of EVs for up to 48 h post iv injection (Tieu et al., 2023), which suggests that the EVs to a large extent biodistribute to the diseased tissue, not primarily elsewhere.

Our current study further adds to previous findings as we have documented the inhibitory effects of ASC‐EVs in virus‐induced acute lung injury in vivo, which may have implications for the human ARDS. Initial clinical trials of MSC‐EVs have indeed implicated efficacy in severe SARS‐CoV‐2‐mediated lung injury, at least in a subpopulation analysis (Lightner et al., 2023).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jun Ho Lee: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Hyungtaek Jeon: Data curation (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Jan Lötvall: Project administration (equal); supervision (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Byong Seung Cho: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Byong Seung Cho and Jun Ho Lee are current employees of ExoCoBio Inc. Byong Seung Cho is the CEO of ExoCoBio Inc. Jun Ho Lee and Byong Seung Cho are shareholders of ExoCoBio Inc. Jan Lötvall holds stock in Exocure Sweden AB and Nexos Biosciences AB and is a scientific advisor for ExoCoBio Inc.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1. Characterization of adipose stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles (ASC‐EVs). (a) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of ASC‐EVs. (b) Purity of ASC‐EVs. The particle‐to‐protein ratio of isolated ASC‐EVs (n = 3). (c) Representative cryo‐transmission electron microscope images of ASC‐EVs. Scale bar: 200 nm. (d) Flow cytometry of EVs associated with Dynabeads with antibodies against CD9, CD63, and CD81 ASC‐EVs. (e) Concentration of TSG101 quantified using ELISA as a marker of EVs (n = 4). (f) Concentration of Calnexin and Cytochrome C quantified by ELISA in EV and ASC cell lysates (n = 4). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the means from three independent experiments; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 compared to ASCs. (g) Relative expression of anti‐viral responses mediated five miRNAs (miR‐181a‐5p, miR‐92a‐3p, miR‐23a‐3p, miR‐103a‐3p, miR‐26a‐5p) measured by qPCR. Relative expression levels were normalized to cel‐miR‐39‐3p (n = 3). (h) Concentration of IFITM3 quantified using ELISA as anti‐viral protein in EVs (n = 6).

Supplementary Figure 2. Study design of the in vivo experiment with SARS‐CoV2 and immunohistochemical analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2infected Syrian hamster lung tissues. (a) Syrian hamsters were infected with a 104 TCID50/mL dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 (NCCP43326). Control (Uninfected): normal Syrian hamsters injected with vehicle control; SARS‐CoV‐2: SARS‐CoV‐2induced Syrian hamsters injected with vehicle control; ASC‐EVs (3 × 109 particles): four administrations of 3 × 109 particles 1, 2, 3, and 4 days post‐infection (dpi); ASC‐EV (1 × 1010 particles): four administrations of 1 × 1010 particles 1, 2, 3, and 4 dpi. (b) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of IL‐1β and N protein in SARS‐CoV‐2infected hamster lung tissues with different treatments (scale bar: 200 µm). (c) Quantification of stained hamster lung tissue area indicating the presence of IL‐1β and N protein (n = 8). (d) The relative expression of SARS‐CoV‐2specific genes (E, RdRP, and N) in SARS‐CoV‐2infected hamster lung tissues at 5 dpi and 7 dpi with different treatments using real‐time qPCR (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. (e) Quantification of total inflammatory cell numbers in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamster lung tissues at 5 dpi and 7 dpi with different treatments (n = 4). Representative tissue images are shown, and the number of total inflammatory cells was quantified in three different areas of every tissue slide. (f) Post‐mortem histopathological scores of peribronchiolar, perivascular, and parenchymal lung tissue in mice infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 virus on day 0 and treated with vehicle or ASC‐EVs with two different treatment regimens.

Supplementary Figure 3. Study design of the in vivo experiment with H1N1 and immunohistochemical analyses of H1N1 influenza A virus‐infected C57BL/6 mouse lungs. (a) Mice were infected with one LD50 dose of influenza A (A/Puerto Rico/08/1934, H1N1) virus on day 0. Control (Uninfected): normal mice injected with vehicle control; influenza: influenza‐induced mice injected with vehicle control; ASC‐EVs (1 × 1010 particles × 3 injections): three administrations of ASC‐EVs on 0, 1, and 2 dpi; ASC‐EVs (1 × 1010 particles × 4 injections): four administrations of ASC‐EVs on 0, 1, 2, and 3 dpi. Mice were monitored until 14 dpi. (b) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of IL‐1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and IL‐10 in infected hamster lung tissues with different treatments (scale bar: 200 µm). (c) Quantification of stained lung tissue area indicating the presence of IL‐1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and IL‐10 (n = 3).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank So Jeong Kim, Hyeong Tae Yu and Yong‐In Yoo, all current or former employees at ExoCoBio Inc., for having contributed to the experiments. Further, we thank Dae Hyun Ha, Helim Lee and Kyojin Lee for contributing to the manufacturing and quality control of the EVs used in this study. All in vivo experiments with SARS‐CoV‐2 were performed under animal biosafety level 3 (ABL‐3) conditions at the Korea Zoonosis Research Institute (KoZRI) of Jeonbuk National University (Jeollabuk‐do, South Korea). All in vivo experiments of Influenza H1N1 were performed at a nonclinical CRO institution (Knotus Co. Ltd, Incheon, Korea). Funding for the present work was provided by a Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine (KFRM) grant funded by the Korean government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Health & Welfare) (Code: 22B0501L1) and within the budget of ExoCoBio Inc.

Lee, J. H. , Jeon, H. , Lötvall, J. , & Cho, B. S. (2024). Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles in SARS‐CoV‐2 and H1N1 influenza‐induced acute lung injury. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 13, e12495. 10.1002/jev2.12495

Contributor Information

Jan Lötvall, Email: jan.lotvall@gu.se.

Byong Seung Cho, Email: ceo@exocobio.com.

REFERENCES

- Börger, V. , Weiss, D. J. , Anderson, J. D. , Borràs, F. E. , Bussolati, B. , Carter, D. R. F. , Dominici, M. , Falcón‐Pérez, J. M. , Gimona, M. , Hill, A. F. , Hoffman, A. M. , de Kleijn, D. , Levine, B. L. , Lim, R. , Lötvall, J. , Mitsialis, S. A. , Monguió‐Tortajada, M. , Muraca, M. , Nieuwland, R. , … Giebel, B. (2020). International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy statement on extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stromal cells and other cells: Considerations for potential therapeutic agents to suppress coronavirus disease‐19. Cytotherapy, 22, 482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier, N. M. , & Lowen, A. C. (2010). Animal models for influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission. Viruses, 2, 1530–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutipongtanate, S. , Kongsomros, S. , Pongsakul, S. , Panachan, J. , Khowawisetsut, L. , Pattanapanyasat, K. , Hongeng, S. , & Thitithanyanont, A. (2022). Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 effect of extracellular vesicles released from mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 11, e12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daemi, H. B. , Kulyar, M. F. , He, X. , Li, C. , Karimpour, M. , Sun, X. , Zou, Z. , & Jin, M. (2021). Progression and trends in virus from influenza A to COVID‐19: An overview of recent studies. Viruses, 13, 1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilogo, I. H. , Aditianingsih, D. , Sugiarto, A. , Burhan, E. , Damayanti, T. , Sitompul, P. A. , Mariana, N. , Antarianto, R. D. , Liem, I. K. , Kispa, T. , Mujadid, F. , Novialdi, N. , Luviah, E. , Kurniawati, T. , Lubis, A. M. T. , & Rahmatika, D. (2021). Umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells as critical COVID‐19 adjuvant therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 10, 1279–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercelen, N. , Pekkoc‐Uyanik, K. C. , Alpaydin, N. , Gulay, G. R. , & Simsek, M. (2021). Clinical experience on umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell treatment in 210 severe and critical COVID‐19 cases in Turkey. Stem Cell Reviews Reports, 17, 1917–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemian, S. R. , Aliannejad, R. , Zarrabi, M. , Soleimani, M. , Vosough, M. , Hosseini, S. E. , Hossieni, H. , Keshel, S. H. , Naderpour, Z. , Hajizadeh‐Saffar, E. , Shajareh, E. , Jamaati, H. , Soufi‐Zomorrod, M. , Khavandgar, N. , Alemi, H. , Karimi, A. , Pak, N. , Rouzbahani, N. H. , Nouri, M. , … Baharvand, H. (2021). Mesenchymal stem cells derived from perinatal tissues for treatment of critically ill COVID‐19‐induced ARDS patients: A case series. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 12, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Li, X. , & Yang, L. (2022). Mesenchymal stem cells and their derived small extracellular vesicles for COVID‐19 treatment. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 13, 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai, M. , Iwatsuki‐Horimoto, K. , Hatta, M. , Loeber, S. , Halfmann, P. J. , Nakajima, N. , Watanabe, T. , Ujie, M. , Takahashi, K. , Ito, M. , Yamada, S. , Fan, S. , Chiba, S. , Kuroda, M. , Guan, L. , Takada, K. , Armbrust, T. , Balogh, A. , Furusawa, Y. , … Kawaoka, Y. (2020). Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and countermeasure development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 117, 16587–16595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyana, M. , Djaharuddin, I. , Rif'ati, L. , Arif, M. , Choi, M. K. , Angginy, N. , Yoon, A. , Han, J. , Josh, F. , Arlinda, D. , Narulita, A. , Muchtar, F. , Bakri, R. A. , & Irmansyah, S. (2022). Safety of DW‐MSC infusion in patients with low clinical risk COVID‐19 infection: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 13, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouroupis, D. , Lanzoni, G. , Linetsky, E. , Messinger, C. S. , Wishnek, M. S. , Leñero, C. , Stone, L. D. , Ruiz, P. , Correa, D. , & Ricordi, C. (2021). Umbilical cord‐derived mesenchymal stem cells modulate TNF and soluble TNF receptor 2 (sTNFR2) in COVID‐19 ARDS patients. European Review Medical Pharmacological Sciences, 25, 4435–4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, H. S. , Lee, J. S. , Bastarache, J. A. , Kuebler, W. M. , Downey, G. P. , Albaiceta, G. M. , Altemeier, W. A. , Artigas, A. , Bates, J. H. T. , Calfee, C. S. , Dela Cruz, C. S. , Dickson, R. P. , Englert, J. A. , Everitt, J. I. , Fessler, M. B. , Gelman, A. E. , Gowdy, K. M. , Groshong, S. D. , Herold, S. , … Matute‐Bello, G. (2022). Update on the features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals: An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 66, e1–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzoni, G. , Linetsky, E. , Correa, D. , Messinger, C. S. , Alvarez, R. A. , Kouroupis, D. , Alvarez, G. A. , Poggioli, R. , Ruiz, P. , Marttos, A. C. , Hirani, K. , Bell, C. A. , Kusack, H. , Rafkin, L. , Baidal, D. , Pastewski, A. , Gawri, K. , Leñero, C. , Mantero, A. M. A. , … Ricordi, C. (2021). Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: A double‐blind, phase 1/2a, randomized controlled trial. Stem Cells Translation Medicine, 10, 660–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. H. , Ha, D. H. , Go, H. K. , Youn, J. , Kim, H. K. , Jin, R. C. , Miller, R. B. , Kim, D. H. , Cho, B. S. , & Yi, Y. W. (2020). Reproducible large‐scale isolation of exosomes from adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their application in acute kidney injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21, 4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W. , Chen, X. , Zhang, S. , Fang, J. , Chen, M. , Xu, Y. , & Chen, X. (2021). Mesenchymal stem cells as a double‐edged sword in tumor growth: Focusing on MSC‐derived cytokines. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters, 26, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightner, A. L. , Sengupta, V. , Qian, S. , Ransom, J. T. , Suzuki, S. , Park, D. J. , Melson, T. I. , Williams, B. P. , Walsh, J. J. , & Awili, M. (2023). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicle infusion for the treatment of respiratory failure from COVID‐19: A randomized, placebo‐controlled dosing clinical trial. Chest, 164, 1444–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K. J. , & Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2(‐Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif.), 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. , Liu, D. X. , & Tam, J. P. (2008). Lipid rafts are involved in SARS‐CoV entry into Vero E6 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 369, 344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, A. , & Tate, M. D. (2018). In vivo infection model of severe influenza A virus. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1725, 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthay, M. A. , Calfee, C. S. , Zhuo, H. , Thompson, B. T. , Wilson, J. G. , Levitt, J. E. , Rogers, A. J. , Gotts, J. E. , Wiener‐Kronish, J. P. , Bajwa, E. K. , Donahoe, M. P. , McVerry, B. J. , Ortiz, L. A. , Exline, M. , Christman, J. W. , Abbott, J. , Delucchi, K. L. , Caballero, L. , McMillan, M. , … Liu, K. D. (2019). Treatment with allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (START study): A randomised phase 2a safety trial. The Lancet, Respiratory Medicine, 7, 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, M. P. , Forleo‐Neto, E. , Musser, B. J. , Isa, F. , Chan, K. C. , Sarkar, N. , Bar, K. J. , Barnabas, R. V. , Barouch, D. H. , Cohen, M. S. , Hurt, C. B. , Burwen, D. R. , Marovich, M. A. , Hou, P. , Heirman, I. , Davis, J. D. , Turner, K. C. , Ramesh, D. , Mahmood, A. , … Covid‐19 Phase 3 Prevention Trial Team . (2021). Subcutaneous REGEN‐COV antibody combination to prevent covid‐19. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385, 1184–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.‐J. , Lee, E.‐N. , Park, J.‐H. , Lee, J. K. , Cho, G. J. , Park, I.‐H. , & Shin, O. S. (2022). Anti‐viral activities of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell‐derived small extracellular vesicles against human respiratory viruses. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12, 850744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium . Pan, H. , Peto, R. , Henao‐Restrepo, A. M. , Preziosi, M. P. , Sathiyamoorthy, V. , Abdool Karim, Q. , Alejandria, M. M. , Hernández García, C. , Kieny, M. P. , Malekzadeh, R. , Murthy, S. , Reddy, K. S. , Roses Periago, M. , Abi Hanna, P. , Ader, F. , Al‐Bader, A. M. , Alhasawi, A. , Allum, E. , … Swaminathan, S. . (2021). Repurposed antiviral drugs for covid‐19—Interim WHO solidarity trial results. The New England Journal of Medicine, 384, 497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. H. , Choi, Y. , Lim, C. W. , Park, J. M. , Yu, S. H. , Kim, Y. , Han, H. J. , Kim, C. H. , Song, Y. S. , Kim, C. , Yu, S. R. , Oh, E. Y. , Lee, S. M. , & Moon, J. (2021). Potential therapeutic effect of micrornas in extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells against SARS‐CoV‐2. Cells, 12, 2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanapanyasat, K. , Hongeng, S. , & Thitithanyanont, A. (2022). Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 effect of extracellular vesicles released from mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 11, e12201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Chilima, T. D. , Moncaubeig, F. , & Farid, S. S. (2018). Impact of allogeneic stem cell manufacturing decisions on cost of goods, process robustness and reimbursement. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 137, 132–151. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelatto, C. L. K. , Senegaglia, A. C. , Franck, C. L. , Daga, D. R. , Shigunov, P. , Stimamiglio, M. A. , Marsaro, D. B. , Schaidt, B. , Micosky, A. , de Azambuja, A. P. , Leitão, C. A. , Petterle, R. R. , Jamur, V. R. , Vaz, I. M. , Mallmann, A. P. , Carraro, J. H. , Ditzel, E. , Brofman, P. R. S. , & Correa, A. (2022). Safety and long‐term improvement of mesenchymal stromal cell infusion in critically COVID‐19 patients: A randomized clinical trial. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 13, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, T. F. , Zhao, F. , Huang, D. , Beutler, N. , Burns, A. , He, W. T. , Limbo, O. , Smith, C. , Song, G. , Woehl, J. , Yang, L. , Abbott, R. K. , Callaghan, S. , Garcia, E. , Hurtado, J. , Parren, M. , Peng, L. , Ramirez, S. , Ricketts, J. , … Burton, D. R. (2020). Isolation of potent SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science, 369, 956–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M. , Vaezi, A. A. , Aliannejad, R. , Sohrabpour, A. A. , Kiaei, S. Z. F. , Shadnoush, M. , Siavashi, V. , Aghaghazvini, L. , Khoundabi, B. , Abdoli, S. , Chahardouli, B. , Seyhoun, I. , Alijani, N. , & Verdi, J. (2021). Cell therapy in patients with COVID‐19 using Wharton's jelly mesenchymal stem cells: A phase 1 clinical trial. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 12, 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, V. , Sengupta, S. , Lazo, A. , Woods, P. , Nolan, A. , & Bremer, N. (2020). Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells as treatment for severe COVID‐19. Stem Cells Development, 29, 747–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , Yuan, X. , Yao, W. , Wang, S. , Zhang, C. , Zhang, B. , Song, J. , Huang, L. , Xu, Z. , Fu, J. L. , Li, Y. , Xu, R. , Li, T. T. , Dong, J. , Cai, J. , Li, G. , Xie, Y. , Shi, M. , Li, Y. , … Wang, F. S. (2022). Human mesenchymal stem cells treatment for severe COVID‐19: 1‐year follow‐up results of a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. eBioMedicine, 75, 103789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K. O. , Ha, D. H. , Kim, J. O. , Crumrine, D. A. , Meyer, J. M. , Wakefield, J. S. , Lee, Y. , Kim, B. , Kim, S. , Kim, H. K. , Lee, J. , Kwon, H. H. , Park, G. H. , Lee, J. H. , Lim, J. , Park, S. , Elias, P. M. , Park, K. , Yi, Y. W. , & Cho, B. S. (2020). Exosomes from human adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells promote epidermal barrier repair by inducing de novo synthesis of ceramides in atopic dermatitis. Cells, 9, 680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu, L. , Niu, C. , Li, R. , Huang, T. , Wang, Y. , Huang, M. , Ji, N. , Zheng, Y. , Chen, X. , Shi, L. , Wu, M. , Deng, K. , Wei, J. , Wang, X. , Cao, Y. , Yan, J. , & Feng, G. (2020). Treatment of severe COVID‐19 with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Research Therapy, 11, 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration . (2020). FDA NEWS RELEASE: FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID‐19. https://www.fda.gov/news‐events/press‐announcements/fda‐approves‐first‐treatment‐covid‐19

- Théry, C. , Witwer, K. W. , Aikawa, E. , Alcaraz, M. J. , Anderson, J. D. , Andriantsitohaina, R. , Antoniou, A. , Arab, T. , Archer, F. , Atkin‐Smith, G. K. , Ayre, D. C. , Bach, J. M. , Bachurski, D. , Baharvand, H. , Balaj, L. , Baldacchino, S. , Bauer, N. N. , Baxter, A. A. , Bebawy, M. , … Zuba‐Surma, E. K. (2018). Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 7, 1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieu, A. , Stewart, D. J. , Chwastek, D. , Lansdell, C. , Burger, D. , & Lalu, M. M. (2023). Biodistribution of mesenchymal stromal cell‐derived extracellular vesicles administered during acute lung injury. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 13, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, T. N. , Meschia, J. F. , Chimowitz, M. I. , Roldan, A. , LeMatty, T. , Luke, S. , Breathitt, L. , Eiland, R. , Foley, J. , & Brott, T. G. (2020). Mitigating the effects of COVID‐19 pandemic on controlling vascular risk factors among participants in a carotid stenosis trial. Journal of Stroke Cerebrovascular Diseases, 12, 105362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo, G. V. , Bagyinszky, E. , & An, S. (2022). COVID‐19 genetic variants and their potential impact in vaccine development. Microorganisms, 10, 598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. , Luo, Y. , Tian, X. , Ma, S. , Sun, Y. , You, C. , Gong, Y. , & Xie, C. (2019). Impact of radiotherapy concurrent with anti‐PD‐1 therapy on the lung tissue of tumor‐bearing mice. Radiation Research, 191, 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Shi, M. , Tong, L. , Wang, J. , Ji, S. , Bi, J. , Chen, C. , Jiang, J. , Bai, C. , Zhou, J. , & Song, Y. (2019). Lung‐resident mesenchymal stem cells promote repair of LPS‐induced acute lung injury via regulating the balance of regulatory T cells and Th17 cells. Inflammation, 42, 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. E. , Chao, T. L. , Tsai, H. T. , Lin, P. H. , Tsai, Y. L. , & Chang, S. Y. (2020). Differentiation of cytopathic effects (CPE) induced by influenza virus infection using deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). PLoS Computational Biology, 16, e1007883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X. , Jiang, W. , Chen, L. , Xu, Z. , Zhang, Q. , Zhu, M. , Ye, P. , Li, H. , Yu, L. , Zhou, X. , Zhou, C. , Chen, X. , Zheng, X. , Xu, K. , Cai, H. , Zheng, S. , Jiang, W. , Wu, X. , Li, D. , … Li, L. (2021). Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of using human menstrual blood‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells in treating severe and critically ill COVID‐19 patients: An exploratory clinical trial. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 11, e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. , He, Z. , Yuan, J. , Wen, W. , Huang, X. , Hu, Y. , Lin, C. , Pan, J. , Li, R. , Deng, H. , Liao, S. , Zhou, R. , Wu, J. , Li, J. , & Li, M. (2015). IFITM3‐containing exosome as a novel mediator for anti‐viral response in dengue virus infection. Cellular Microbiology, 17, 105–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Characterization of adipose stem cell‐derived extracellular vesicles (ASC‐EVs). (a) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of ASC‐EVs. (b) Purity of ASC‐EVs. The particle‐to‐protein ratio of isolated ASC‐EVs (n = 3). (c) Representative cryo‐transmission electron microscope images of ASC‐EVs. Scale bar: 200 nm. (d) Flow cytometry of EVs associated with Dynabeads with antibodies against CD9, CD63, and CD81 ASC‐EVs. (e) Concentration of TSG101 quantified using ELISA as a marker of EVs (n = 4). (f) Concentration of Calnexin and Cytochrome C quantified by ELISA in EV and ASC cell lysates (n = 4). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the means from three independent experiments; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 compared to ASCs. (g) Relative expression of anti‐viral responses mediated five miRNAs (miR‐181a‐5p, miR‐92a‐3p, miR‐23a‐3p, miR‐103a‐3p, miR‐26a‐5p) measured by qPCR. Relative expression levels were normalized to cel‐miR‐39‐3p (n = 3). (h) Concentration of IFITM3 quantified using ELISA as anti‐viral protein in EVs (n = 6).

Supplementary Figure 2. Study design of the in vivo experiment with SARS‐CoV2 and immunohistochemical analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2infected Syrian hamster lung tissues. (a) Syrian hamsters were infected with a 104 TCID50/mL dose of SARS‐CoV‐2 (NCCP43326). Control (Uninfected): normal Syrian hamsters injected with vehicle control; SARS‐CoV‐2: SARS‐CoV‐2induced Syrian hamsters injected with vehicle control; ASC‐EVs (3 × 109 particles): four administrations of 3 × 109 particles 1, 2, 3, and 4 days post‐infection (dpi); ASC‐EV (1 × 1010 particles): four administrations of 1 × 1010 particles 1, 2, 3, and 4 dpi. (b) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of IL‐1β and N protein in SARS‐CoV‐2infected hamster lung tissues with different treatments (scale bar: 200 µm). (c) Quantification of stained hamster lung tissue area indicating the presence of IL‐1β and N protein (n = 8). (d) The relative expression of SARS‐CoV‐2specific genes (E, RdRP, and N) in SARS‐CoV‐2infected hamster lung tissues at 5 dpi and 7 dpi with different treatments using real‐time qPCR (n = 6). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. (e) Quantification of total inflammatory cell numbers in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected hamster lung tissues at 5 dpi and 7 dpi with different treatments (n = 4). Representative tissue images are shown, and the number of total inflammatory cells was quantified in three different areas of every tissue slide. (f) Post‐mortem histopathological scores of peribronchiolar, perivascular, and parenchymal lung tissue in mice infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 virus on day 0 and treated with vehicle or ASC‐EVs with two different treatment regimens.

Supplementary Figure 3. Study design of the in vivo experiment with H1N1 and immunohistochemical analyses of H1N1 influenza A virus‐infected C57BL/6 mouse lungs. (a) Mice were infected with one LD50 dose of influenza A (A/Puerto Rico/08/1934, H1N1) virus on day 0. Control (Uninfected): normal mice injected with vehicle control; influenza: influenza‐induced mice injected with vehicle control; ASC‐EVs (1 × 1010 particles × 3 injections): three administrations of ASC‐EVs on 0, 1, and 2 dpi; ASC‐EVs (1 × 1010 particles × 4 injections): four administrations of ASC‐EVs on 0, 1, 2, and 3 dpi. Mice were monitored until 14 dpi. (b) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of IL‐1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and IL‐10 in infected hamster lung tissues with different treatments (scale bar: 200 µm). (c) Quantification of stained lung tissue area indicating the presence of IL‐1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α, IFN‐γ, and IL‐10 (n = 3).