Abstract

Background

The association between education, intelligence, and cognition with digestive tract diseases has been established. However, the specific contribution of each factor in the pathogenesis of these diseases are still uncertain.

Method

This study employed multivariable Mendelian randomization (MR) to assess the independent effects of education, intelligence, and cognition on gastrointestinal conditions in the FinnGen and UK Biobank European-ancestry populations. A two-step MR approach was employed to assess the mediating effects of the association.

Results

Meta-analysis of MR estimates from FinnGen and UK Biobank showed that 1- SD (4.2 years) higher education was causally associated with lower risks of gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.66), peptic ulcer (OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.47, 0.69), irritable bowel syndrome (OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.56, 0.87), diverticular disease (OR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.78), cholelithiasis (OR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.59, 0.79) and acute pancreatitis (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.41, 0.72), independently of intelligence and cognition. These causal associations were mediating by body mass index (3.7-22.3%), waist-to-hip ratio (8.3-11.9%), body fat percentage (4.1-39.8%), fasting insulin (1.4-5.5%) and major depression (6.0-12.4%).

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate a causal and independent association between education and six common digestive tract diseases. Additionally, our study highlights five mediators as crucial targets for preventing digestive tract diseases associated with lower education levels.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-024-03400-x.

Keywords: Digestive tract diseases, Education, Mendelian randomization, Mediation analyses, Cognition, Intelligence

Background

Educational attainment, intelligence and cognitive abilities are important predictors of socioeconomic attainment, health outcomes, and a broad of implications for lifestyle behaviors [1, 2]. It has been observed in various studies that individuals with higher educational attainment, superior intelligence and cognitive abilities are associated with a lower prevalence of partial gastrointestinal disorders [3, 4]. However, there exists a reciprocal relationship among education level, intelligence, and cognitive abilities [1], and recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified genetic association between education and intelligence [5]. A growing body of compelling evidence suggests that lifestyle factors and metabolic determinants contribute to an increased risk of digestive tract diseases [6–8]. These modifiable risks are further influenced by education level, cognitive function, and intelligence [9, 10]. Thus far, the independent causal impact of education, intelligence, and cognitive ability on digestive tract diseases remains uncertain, and the extent to which potentially modifiable risk factors mediate this association is still unclear. A comprehensive understanding of this topic can provide valuable insights into prevention and intervention strategies for the occurrence and progression of digestive tract diseases.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a well-established method that is widely recognized for establishing causal inferences based on observational data. In this approach, instrumental variables are employed, which are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified through genome-wide association GWAS. These SNPs demonstrate robust associations with a particular exposure, enabling them to serve as reliable proxies [11]. The MR methodology has recently witnessed significant advancements, such as the integration of multivariable MR (MVMR). This approach enables the exploration of mediation effects and the independent impact of interrelated exposures on a given outcome by incorporating genetic variants associated with each exposure into a unified model [12, 13].

Our primary objective is to investigate the independent causal associations of education, intelligence, or cognition with digestive tract diseases. Additionally, we aim to investigate the underlying causal structure by evaluating potential mediators within an MVMR framework.

Methods

Study design

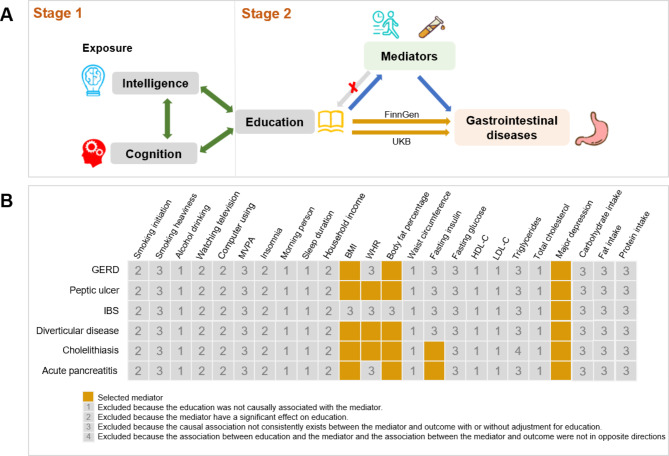

Our study consisted of 2 stages (Fig. 1A); In the first stage, we used univariable MR (UVMR) to assessed the effect of education, intelligence, and cognitive performance on eight digestive tract diseases, and the results shown a comprehensive association between education, intelligence, cognition and digestive tract diseases. Then, the results of MVMR found that only education remained an independent protective contributor for six out of the eight digestive tract diseases with adjustment for intelligence and cognition. In the second stage, we selected 5 mediators from 23 candidate mediators within rigorous screening conditions, and then we calculated the mediating proportion in the casual effect of education on six digestive tract diseases. The study methods were compliant with the STROBE-MR checklist(Supplementary File 2) [14].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study design. A, Study design. B, Mediator selection process. This study consisted of 2 stages of analyses. In stage 1, we examined the causal links between education, intelligence, and cognition and eight digestive tract diseases. To evaluate the overall and independent causal effects of each exposure on outcomes, we employed univariable Mendelian randomization (UVMR) and multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR) approaches. The MVMR analysis revealed that solely education exhibited an independent causal influence on six of the eight digestive tract diseases with adjustment for intelligence and cognition. In stage 2, we first selected potential mediators for the association between education and the six digestive tract diseases. Subsequently, their mediating effects were calculated using a two-step MR. MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; BMI, body mass index; HR, waist-to-hip ratio; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBS, Irritable bowel syndrome

Data for exposure

The SNPs associated with education, intelligence and cognition were all derived from latest GWASs (Table 1). GWAS datasets for education was conducted by Social Science Genetic Association Consortium, which included 766,345 of European-ancestry individuals after ruling out participants from 23andMe [15]. The population included in the education related GWAS was aged older than 30 years and was assessed on the basis of the number of years of education received. Genetic associations with intelligence were derived from recent GWAS of multiple traits consisted with 269 867 European-ancestry individuals and adjusted for age, sex, ancestry principal components [5]. GWAS datasets for cognition was conducted by Cognitive Genomics Consortium, which included 257 841 individuals of European ancestry. We selected genetic instruments at genome- wide significance (P < 5 × 10− 8), and independent instruments variants (IVs) were obtained after linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001 within 10,000 kb). In addition, SNPs that exhibit significant associations with the outcome variables (P < 5 × 10− 8) were excluded from the analysis.

Table 1.

Information of GWAS datasets used in the MR study

| Phenotype | Unit | No of participants | Ancestry | Consortium/cohort | Year of publication | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | ||||||

| Education | SD (4.2 y) | 766 345 | European | SSGAC | 2018 | 30,038,396 |

| Intelligence | SD | 269 867 | European | META | 2018 | 29,942,086 |

| Cognition | SD (0.99 points) | 257 841 | European | COGENT | 2018 | 30,038,396 |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal diseases | Event | - | European | FinnGen | 2023 | - |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | Event | - | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,424,355 |

| 24 candidate mediators* | ||||||

| Selected mediators | ||||||

| BMI | SD (4.7 kg/m 2) | 681 275 | European | GIANT | 2018 | 30,124,842 |

| WHR | SD (0.09) | 212 244 | European | GIANT | 2015 | 25,673,412 |

| BF% | SD | 454 633 | European | UK Biobank | 2018 | 29,846,171 |

| Fasting insulin | SD (0.68 mmoL/L) | 151 013 | European | Meta | 2021 | 34,059,833 |

| Major depression | Event |

170 756 cases 329 443 controls |

European | PGC | 2019 | 30,718,901 |

| Excluded mediators | ||||||

| MVPA |

SD (2084 MET-min/week) |

377 234 | European | UK Biobank | 2018 | 29,899,525 |

| Watching television | SD (1.5 h) | 408 815 | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,317,632 |

| Computer using | SD (1.2 h) | 408 815 | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,317,632 |

| Insomnia | Event |

397 972 cases 463 020 controls |

European | UK Biobank | 2019 | 30,804,566 |

| Sleep duration | 1.1 h/day | 446 118 | European | UK Biobank | 2019 | 30,846,698 |

| Morning person | Event |

252 287 cases 150 908 controls |

European | UK Biobank | 2019 | 30,696,823 |

| Smoking initiation | Event |

311 629 cases 321 173 controls |

European | GSCAN | 2019 | 30,643,251 |

| Smoking heaviness | SD (8 cigarettes/d) | 337 334 | European | GSCAN | 2019 | 30,643,251 |

| Alcohol drinking | SD (9 drinks/wk) | 335 394 | European | GSCAN | 2019 | 30,643,251 |

| Total household income | SD | 397 751 | European | UK Biobank | 2018 | 29,846,171 |

| Relative intake of carbohydrates | SD | 268,922 | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,393,786 |

| Relative intake of fat | SD | 268,922 | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,393,786 |

| Relative intake of protein | SD | 268,922 | European | UK Biobank | 2020 | 32,393,786 |

| Waist circumference | SD (12.5 cm) | 231 353 | European | GIANT | 2015 | 25,673,412 |

| Fasting glucose | SD (0.60 mmoL/L) | 200 622 | European | Meta | 2021 | 34,059,833 |

| HDL-C | SD (15.5 mg/dL) | 187 167 | Mixed | GLGC | 2013 | 24,097,068 |

| LDL-C | SD (38.7 mg/dL) | 173 082 | Mixed | GLGC | 2013 | 24,097,068 |

| Total cholesterol | SD (41.8 mg/dL) | 187 365 | Mixed | GLGC | 2013 | 24,097,068 |

| Triglycerides | SD (90.7 mg/dL) | 177 861 | Mixed | GLGC | 2013 | 24,097,068 |

SSGAC, Social Science Genetic Association Consortium; COGENT, Cognitive Genomics Consortium; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; BF% indicates body fat percentage; GIANT, Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits; PGC, Psychiatric Genomic Consortium; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; GSCAN, GWAS & Sequencing Consortium of Alcohol and Nicotine use; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; GLGC, Global Lipids Genetics Consortium; MR, Mendelian randomization

*Five out of 21 candidate mediators met all criteria of mediator selection and were included in the mediation MR analyses

Data for outcomes

The outcome of GWASs on eight digestive tract diseases were obtained from two independent consortia: the FinnGen study and the UK Biobank study, the detail information of included outcome data was shown in Table S1. To ensure the stability of the results, only diseases with a sample size greater than 1000 were considered for inclusion in the outcome analysis. For the FinnGen study, we utilized eight digestive tract diseases summary-level data in individuals of European ancestry from the most recent publicly available R9 release. These diseases were defined using the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-8), ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes. On the other hand, the UK Biobank study involved a large cohort of over 500,000 participants recruited in the UK between 2006 and 2010. In our analysis, we utilized summary statistics from GWAS conducted by the Lee lab [16], focusing on individuals of European ancestry. The gastrointestinal disease outcomes in this study were defined using the ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes.

Data for mediators

Based on literature reviews [17–19], the 24 candidate mediators were used in this study, which included three physical activity traits (moderate to vigorous physical Activity [MVPA] [20], watching television [21], computer using [21]), two stress-related traits (insomnia [22], major depression [23]), two sleep traits (sleep duration [24], morning person [25]), three smoking and drinking traits (smoking initiation [26], smoking behaviors [26] and alcohol drinking per week [26]), total household income [27], four adiposity traits (body mass index [BMI] [28], body fat percentage [BF%] [27], waist-to-hip-ratio [WHR] [29] and waist circumference [29]), two glycemic traits (fasting insulin [30], fasting glucose [30]), four lipids traits (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] [31], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] [31], triglycerides [31], total cholesterol) [31], intake of carbohydrate, protein, and fat [32]. The detailed information of those 24 candidate mediators were shown in Table 1.

To ensure the validity of the mediation analyses, we conducted a thorough screening for mediators between education and digestive tract diseases as follows (1) Education is causally associated with the mediator, and it should be noted that the impact of education on the mediator is unidirectional, as bidirectionality between them may impact the integrity of the analyses [33]. (2) There is a consistent causal association between the mediator and digestive tract diseases with adjustment for education. (3) The relationship between education and the mediator, as well as the association between the mediator and digestive tract diseases, should be in opposite directions. The detailed process of mediator selection can be found in Fig. 1B.

Finally, In the mediation analyses, we included a total of 5 mediators that satisfied all criteria (BMI, WHR, BF%, Fasting insulin, Major depression). These mediators were examined to assess their mediating effects on the causal association between education and digestive tract diseases.

This study is based on publicly available summary statistics data, ethical approval and consent for the summary statistics were obtained from the original publication.

Statistical analysis

To estimate the effect size of each independent variable (IV), we utilized the Wald ratio. Subsequently, we combined these ratios using the inverse variance weighting (IVW) method, and we used the multiplicative random-effects IVW method as main analysis in this study. Furthermore, three additional approaches were employed to corroborate the results obtained from the IVW estimator. The weighted median [34] and MR-Egger estimators were utilized to generate unbiased causal estimates, even in the presence of invalid IVs. The intercept test of MR-Egger can identify unmeasured pleiotropy, and it can produce estimates while considering horizontal pleiotropy, but the precision of the estimates may be reduced [35]. Additionally, the Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) method [36], a variation of the IVW estimator, was applied to produce consistent estimates by identifying and excluding significant pleiotropic outliers. Heterogeneity among SNPs’ estimates in each association was estimated by Cochran’s Q value. Summary of the different methods used for MR analysis was shown in Supplementary File 1.

Then, we conducted multivariable MVMR to estimate the effect of education, intelligence, and cognition on the gastrointestinal disease outcome with mutual adjustment to explore whether one exposure was causally associated with the outcomes independent of another two exposures. The performance of all MR should be based on three fundamental assumptions: (1) A close association between genetic variants and the exposure; (2) No association between genetic variants and any potential confounding factors; and (3) The association between genetic variants and the outcome solely occurs through the exposure pathway.

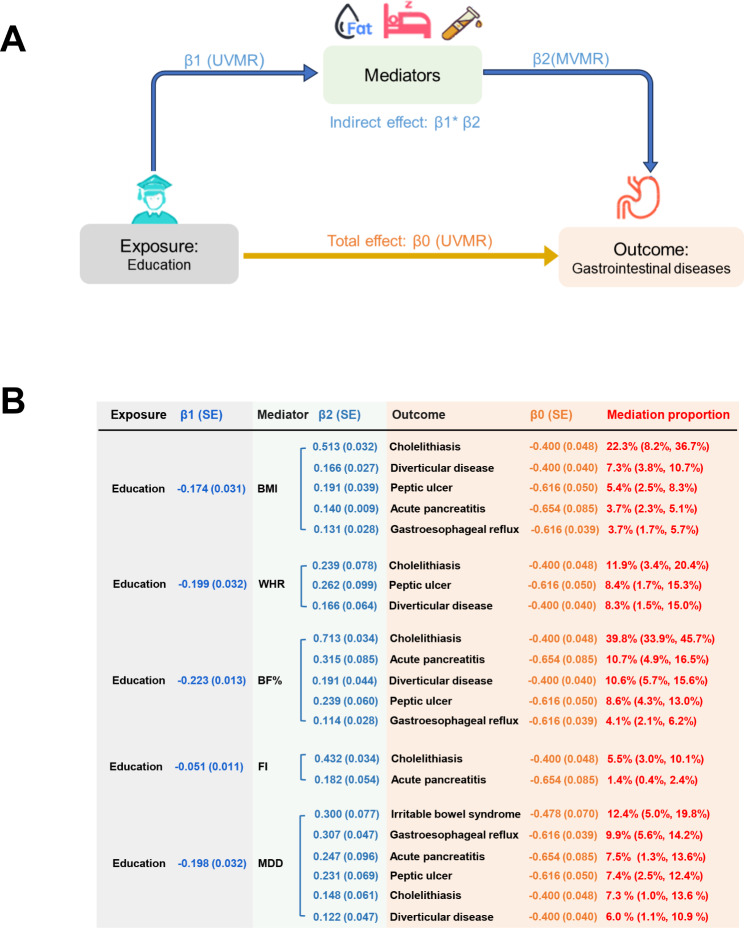

Two- step MR was conducted to calculate the mediating effects of selected mediators in the casual association between education and outcomes. At first step, UVMR was employed to estimate the causal effect of education on each mediator, with each estimation defined as β1. In the second step, the causal effect of each mediator on each outcome was estimated using GWASs from FinnGen and UK Biobank, with adjustment for education using MVMR, and the MVMR estimate was denoted as indirect effect (β2). We assessed the causal effect of exposure on outcome by performing UVMR, with estimates defined as total effect (β0). Ultimately, the proportion of mediation for each mediator in the overall effect of education on gastrointestinal disease was determined by dividing the indirect effect (obtained through the estimates from the two steps, β1 × β2pooled) by the total effect (β0) [37], the delta method was used to assess the 95%CI of the mediation proportion [38].

The mRnd statistical power online tool (http://cnsgenomics.com/shiny/mRnd/) was ultilized for the power calculation. All analyses were conducted using R packages TwoSampleMR, MVMR, and MRPRESSO in R software 4.1.1. To account for multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg correction was employed to control the false discovery rate. Associations with a nominal P-value < 0.05, but a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value > 0.05, were considered suggestive, while associations with a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered significant. We considered IVW estimates as causal effect only if they exhibited consistent direction with all sensitivity analysis.

Results

Finally, we obtained 317, 165 and 147 independent IVs for education, intelligence and cognition, respectively. The F-statistic of each genetic variant exceeded 10, indicating a good strength of IVs were utilized (Table S2). All associations had sufficient statistical power (Table S3).

Unadjusted and adjusted causal effects of education, intelligence and cognition on eight digestive tract diseases

In the IVW method, the UNMR results for digestive tract diseases from FinnGen study and UK Biobank study were highly consistent (Table S4-6). Meta-analysis of the IVW results from different sources showed that each 1- SD (4.2 years) longer genetically predicted years of schooling was associated with a lower risk of gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.59), peptic ulcer (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.49, 0.61), irritable bowel syndrome (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.54, 0.70), diverticular disease(OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.62, 0.72), NAFLD (OR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.44, 0.70), cholelithiasis (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.72), acute pancreatitis (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.44, 0.61) but not acute appendicitis (OR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88, 1.01). After adjusting for intelligence and cognition, the associations remained for education with digestive tract diseases except for NAFLD (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.53, 1.18), and all MVMR results were shown in Table S7. The UVMR and MVMR results remain consistent after FDR- adjustment for multiple testing (Table S8). Therefore, education was independent protect factors for six digestive tract diseases after MVMR analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

UVMR and MVMR estimates of the causal associations of education, intelligence, and cognition with digestive tract diseases. Plots (bars) represent OR (95% CI) of IVW for the risk of eight digestive tract diseases associated with each 1- SD increase in years of schooling. As for education, blue plots represent the univariable Mendelian randomization (UVMR) results, and orange plots represent the multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR) results after adjusted for intelligence and cognition. As for intelligence, blue plots represent the UVMR results, and orange plots represent the MVMR results after adjusted for education and cognition. As for cognition, blue plots represent the UVMR results, and orange plots represent the MVMR results after adjusted for education and intelligence. Estimates with P < 0.05 in IVW analysis are reported in bold. The estimates of gastrointestinal disease were meta-analysis by combining estimates from the UK Biobank study and the FinnGen study. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NAFLD, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Each 1-SD higher intelligence was associated with a lower risk of gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.71, 0.84), peptic ulcer (OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.79, 0.99), irritable bowel syndrome (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.70, 0.89), diverticular disease (OR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.78, 0.92), NAFLD (OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.58, 0.90), cholelithiasis (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.73, 0.86), acute pancreatitis (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.70, 0.94) but not acute appendicitis (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.87, 1.04). After adjusting for education and cognition, the associations vanished for intelligence with each gastrointestinal disease (Fig. 2; Table S7).

Each 1-SD better cognition was associated with a lower risk of gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.68, 0.79), peptic ulcer (OR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.75, 0.88), irritable bowel syndrome (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.68, 0.88), diverticular disease(OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.82, 0.96), NAFLD (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.53, 0.84), cholelithiasis (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.77, 0.90), acute pancreatitis (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.71, 0.97), acute appendicitis (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.83, 0.99). After adjusting for education and intelligence, the associations vanished for cognition with each gastrointestinal disease (Fig. 2; Table S7).

All directions of IVW results were consistent with those of several sensitivity analyses results. Heterogeneity was observed across the studies, but the MR-Egger test revealed no evidence of potential horizontal pleiotropy in all MR analyses, except for the analysis of NAFLD in the FinnGen study when cognition was the exposure (Table S4-6). Although MR-PRESSO identified some outliers, the associations remained significant even after excluding these outlier SNPs (Table S4-6).

Effect of education on each mediator

Out of the 23 potential mediators, five mediators met the screening criteria and were incorporated into the mediation MR analyses (Fig. 1B). In the UVMR analyses, 1-SD increase in years of schooling was associated with lower BMI (IVW β: −0.174; 95% CI: -0.234, -0.113), lower WHR (β: −0.199; 95% CI: -0.262, -0.136), lower BF% (β: −0.223; 95% CI: -0.252, -0.193), lower fasting insulin (β: −0.051; 95% CI: -0.073, -0.029), and a decreased risk of major depression (β: −0.198; 95% CI: -0.261, -0.135). Results remained consistent in several sensitivity analyses (Table 2). Genetic IVs for education demonstrated consistent heterogeneity and no evidence of pleiotropy with the IVs for mediators. In the reverse MR analyses, there was limited support for a significant causal effect of mediators on education, except for a negative association between BMI, BF%, WHR and education, which was mainly driven by horizontal pleiotropy (P value for Egger intercept < 0.001) (Table S9).

Table 2.

UVMR estimating the causal associations between education and the selected mediators

| Mediator | Method | β (95% CI) | P value | * P (Intercept) | # P (Heterogeneity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | IVW | -0.174 (-0.234, -0.113) | < 0.001 | 0.779 | < 0.001 |

| Weighted Median | -0.152 (-0.203, -0.100) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR Egger | -0.201 (-0.479, 0.063) | 0.135 | - | - | |

| MR PRESSO | -0.171 (-0.220, -0.119) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| WHR | IVW | -0.199 (-0.262, -0.136) | < 0.001 | 0.949 | 0.007 |

| Weighted Median | -0.230 (-0.317, -0.143) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR Egger | -0.192 (-0.475, 0.091) | 0.186 | - | - | |

| MR PRESSO | -0.230 (-0.291, -0.169) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| BP% | IVW | -0.223 (-0.252, -0.193) | < 0.001 | 0.285 | < 0.001 |

| Weighted Median | -0.212 (-0.242, -0.181) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR Egger | -0.155 (-0.282, -0.028) | 0.017 | - | - | |

| MR PRESSO | -0.223 (-0.192, -0.776) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| Fasting insulin | IVW | -0.051 (-0.073, -0.029) | < 0.001 | 0.808 | < 0.001 |

| Weighted Median | -0.066 (-0.097, -0.034) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR Egger | -0.061 (-0.153, 0.032) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR PRESSO | -0.047 (-0.069, -0.026) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| Major depression | IVW | -0.198 (-0.261, -0.135) | < 0.001 | 0.588 | < 0.001 |

| Weighted Median | -0.236 (-0.310, -0.162) | < 0.001 | - | - | |

| MR Egger | -0.127 (-0.396, 0.141) | 0.352 | - | -- | |

| MR PRESSO | -0.209 (-0.279, -0.140) | < 0.001 | - |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; VW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; PRESSO, pleiotropy residual sum and outlier; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; BF%, body fat percentage

*P(Intercept), p value of MR-Egger intercept; #P(Heterogeneity), p value of Cochrane’s Q value in heterogeneity test

Causal effect of each mediator on digestive tract diseases with adjustment for education

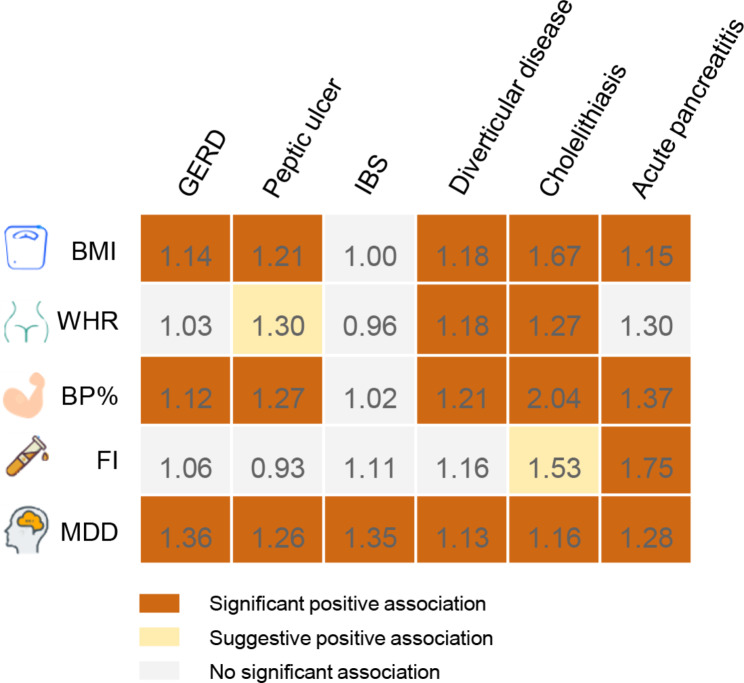

In pooled MVMR, BMI was significant positive association with gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.21), peptic ulcer (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.31), diverticular disease (OR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.25), cholelithiasis (OR: 1.67; 95% CI: 1.57, 1.77) and acute pancreatitis (OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.18) with adjustment of education (Fig. 3; Table S10-11). WHR was significant positive association with diverticular disease (OR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.34) and cholelithiasis (OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.47), and suggestive positive association with peptic ulcer (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.59) with adjustment of education. FB% was significant positive association with gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.19), peptic ulcer (OR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.43), diverticular disease (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.33), cholelithiasis (OR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.91, 2.20) and acute pancreatitis (OR: 1.37; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.61) with adjustment of education. Fasting insulin was significant positive association with acute pancreatitis (OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.18, 2.60), and suggestive positive association with cholelithiasis (OR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.18). Major depression was significant positive association with gastroesophageal reflux (OR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.24, 1.50), peptic ulcer (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.10, 1.44), irritable bowel syndrome (OR: 1.35; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.57), diverticular disease (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.23), cholelithiasis (OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.31) and acute pancreatitis (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.55) with adjustment of education.

Fig. 3.

Summary of the causal association between each mediator and digestive tract diseases with adjustment for education. M Numbers in the boxes are ORs for associations of exposure and each gastrointestinal outcome. The reported ORs are scaled to a 1-unit increase in log odds of genetic liability to major depression and a 1-unit increase of body mass index, waist- to- hip ratio, body fat percentage and fasting insulin. The association with a P value < 0.05, but Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values > 0.05, was considered suggestive, and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values < 0.05 were deemed significant. The estimates of gastrointestinal disease were meta-analysis by combining estimates from the UK Biobank study and the FinnGen study. BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist- to- hip ratio; BF%, body fat percentage; FI, fasting insulin; MDD, major depression; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBS, Irritable bowel syndrome

Mediation effect of mediator in the associations between education and digestive tract diseases

We employed a two-step MR approach to examine the mediating role of mediator in the causal effects of education on six digestive tract diseases (Fig. 4A). The effects of education on digestive tract diseases were partly attenuated after adjusting for each mediator (Table S12). BMI explained 22.3% (95% CI: 8.2– 36.4%) of the total effect of education on cholelithiasis, followed by diverticular disease (7.3%; 3.8– 10.7%), peptic ulcer (5.4%; 2.5– 8.3%), acute pancreatitis (3.7%; 2.3– 5.1%), and gastroesophageal reflux (3.7%; 1.7– 5.7%; Fig. 4B). The proportion mediated by WHR in the associations between education and outcomes was 11.9% (3.4– 20.4%) for cholelithiasis, 8.4% (1.7– 15.3%) for peptic ulcer, and 8.3% (1.5– 15.0%) for diverticular disease. BP% explained 39.8% (95% CI: 33.9– 45.7%) of the total effect of education on cholelithiasis, followed by acute pancreatitis (10.7%; 4.9– 16.5%), diverticular disease (10.6%; 5.7– 15.6%), peptic ulcer (8.6%; 4.3– 13.0%), and gastroesophageal reflux (4.1%; 2.1– 6.2%). The proportion mediated by fasting insulin in the associations between education and outcomes was 5.5% (3.0– 10.1%) for cholelithiasis and 1.4% (0.4– 2.4%) for acute pancreatitis. Major depression explained 12.4% (95% CI: 5.0– 19.8%) of the total effect of education on irritable bowel syndrome, followed by gastroesophageal reflux (9.9%; 5.6– 14.2%), acute pancreatitis (7.5%; 1.3– 13.6%), peptic ulcer (7.4%; 2.5– 12.4%), diverticular disease (7.3%; 3.8– 10.7%), peptic ulcer (5.4%; 2.5– 8.3%), cholelithiasis (7.3%; 1.0– 13.6%) and acute pancreatitis (6.0%; 1.1– 10.9%).

Fig. 4.

Two-step MR framework and estimated proportion mediated by mediator in the causal associations between education and digestive tract diseases. (A) Two- step MR framework. (B) Proportion mediated by mediator in the causal associations between education and digestive tract diseases. To assess the mediating role in the causal connections between education and six digestive tract diseases, a two-step Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis was employed. In the first step, the causal impact of education on each mediator was estimated using univariable Mendelian randomization (UVMR), with each estimate denoted as β1. In the second step, the causal influence of each mediator on each outcome was estimated using multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR), considering the adjustment for education. The resulting estimate from MVMR was denoted as β2. To determine the mediation proportion in the association between education and each outcome, the product of β1 and β2 was divided by the total causal effect of education on the outcome (β0), and the 95% CI of the mediation proportion was obtained using the delta method. CI, confidence interval; MR, Mendelian randomization; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist- to- hip ratio; BF%, body fat percentage; FI, fasting insulin; MDD, major depression

Discussion

In this MR study, we found independent causal effect of education on six digestive tract diseases, while adjusting for intelligence and cognition. However, the causal effects of intelligence and cognition on six digestive tract diseases were no longer significant after adjusting for education, indicating that education played a substantial role in influencing their effects. Furthermore, we explored whether these effects were mediated through some causal pathways. In our investigation of the pathway from education to outcomes, we conducted a thorough examination of potential mediators. Out of the 23 modifiable risk factors, we identified five factors that acted as causal mediators. These mediators were ranked based on their proportion in mediating the association between education and six digestive tract diseases, including BMI (3.7%- 22.3), WHR (8.3- 11.9%), BP% (4.1- 39.8%), Fasting insulin (1.4- 5.5%) and major depression (7.4- 12.4%). The direct effect of education on digestive tract diseases was remained significant with adjustment for some mediators. These findings support an independent causal effect of education on gastrointestinal disease, and considerable mediating effect of five mediators, primarily adiposity traits, between education and digestive tract diseases.

Accumulating evidence from observational and MR studies has consistently suggested that individuals with higher levels of educational attainment and cognition exhibit a decreased risk of several digestive tract diseases [17, 39–42]. Moreover, it has been observed in various observational studies that individuals with superior intelligence and cognitive abilities are associated with a lower prevalence of partial gastrointestinal disorders [3], however, no MR studies have been conducted to investigate this relationship. The current study provides robust genetic evidence supporting the bidirectional connections among educational attainment, intelligence, and cognition [5]. Therefore, it is still unclear whether educational attainment, intelligence, or cognitive function has an independent impact on digestive tract diseases. Our MR analysis builds upon previous findings and provides additional evidence indicating that higher levels of educational attainment independently confer a primary protective effect against digestive tract diseases, beyond the influence of intelligence and cognition.

The evidence substantiating the significance of education as a determining factor for health is extremely persuasive. The level of education significantly influences health outcomes by affecting employment, health-related behaviors, and income [43]. Gaining insight into the connection between education and health outcomes is crucial for mitigating health disparities and enhancing the overall health of the population. However, there remains a limited number of studies investigating the relationship between education and digestive tract diseases. The HUNT2 and HUNT3 studies indicated that individuals with a higher level of education had a reduced relative risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease [44, 45]. This observational study was supported by a recent MR study, which examined the relationship between education and esophageal disorders [4]. Another MR study discovered a noteworthy correlation between education and NAFLD, aligning with the outcomes of our UVMR analysis [39]. However, when adjusting for intelligence and cognitive function, the direct impact of education on NAFLD weakened towards null in the FinnGen and UK Biobank studies. This indicates that the association is primarily influenced by intelligence and cognitive function. However, it is noteworthy that this result may be influenced by sample size limitations. Despite using the two largest GWAS databases available, the combined sample size for NAFLD is less than 4,000 individuals. In conclusion, educational attainment does indeed decrease the occurrence of certain gastrointestinal disorders, and compared to intelligence and cognitive function, educational attainment is a more modifiable factor [46]. Hence, our findings offer valuable insights for prioritizing education policies and reducing educational disparities as preemptive measures to alleviate the burden of gastrointestinal and associated diseases [46].

An additional significant discovery in this study is the identification of the mediating effects of mediators in the association between education and digestive tract diseases. We rigorously screened 23 candidate mediator variables and ultimately identified five mediators that met the criteria, including three adiposity traits (BMI, WHR and BP%), fasting insulin and major depression. It is worth noting that BMI mediates a 22.3% risk of cholelithiasis, while BP% mediates a 39.8% risk of cholelithiasis and 10.7% and 10.6% risks of acute pancreatitis and diverticular disease, respectively. These findings align with prior epidemiological and MR studies, which have consistently linked obesity to digestive tract diseases [8, 47]. This suggests that interventions targeted at obesity may significantly reduce the risk of digestive tract diseases, particularly in individuals with lower levels of education. Furthermore, depression mediates a risk of 6.0–12.4% for all six digestive tract diseases. There are several biological mechanisms that could explain the direct influence of depression on digestive tract diseases. Dysregulation of gastric acid secretion, attributed to autonomic dysfunction associated with depression, can contribute to the development of gastroesophageal reflux and peptic ulcers [48, 49]. Furthermore, chronic stress triggers the neuroendocrine response and stimulates cortisol production, resulting in an imbalance in gut microbiota and subsequent intestinal inflammation [48, 50]. It is worth noting that obesity, depression, and abnormal blood glucose are prevalent public health conditions that frequently coexist and share underlying biological mechanisms [51, 52]. Therefore, due to the interrelationships among the five mediators, there may be some degree of overlap in the proportions mediated by each mediator in our analyses [46].

Interestingly, despite being supported by robust observational studies, several candidate mediators did not exhibit mediating effects in the pathway from education to gastrointestinal disease in this MR study. Multiple observational studies [53, 54] have reported significant associations between educational attainment and LDL-C, HDL-C, total cholesterol, alcohol consumption, and waist circumference. However, our MR study did not provide support for these associations, suggesting that the observed results in the observational studies may be biased by residual confounding or reverse causation [55]. Furthermore, previous research has indicated associations between education and smoking, insomnia, and sedentary behavior [56–58]. However, establishing a causal relationship between them has been challenging. In our MR analysis, we identified a bidirectional relationship between education and these factors.

To our knowledge, this is the first MR study to investigate the separate causal effects of education on gastrointestinal disease, independent of intelligence and cognition. Furthermore, it successfully identifies the causal mediators involved in the pathway linking education and digestive tract diseases. The major strength of the present study is MR design, which effectively minimized confounding and reverse causality biases. In addition, we used two independent outcome source GWAS, such as the FinnGen Study, which ensured minimal overlap with exposure or mediator GWASs to minimize the likelihood of type 1 errors. Additionally, the UK Biobank, with its large sample size, was utilized to replicate and validate the findings from the FinnGen Study, and the combined effects increased statistical power as well as strengthened our findings. Furthermore, the results of several sensitivity analyses in the MR study corroborated the IVW results, demonstrating the robustness and stability of our findings.

This MR study also has several limitations. First, Gender may influence the relationship between education and gastrointestinal diseases; however, due to the lack of individual-level GWAS data, we were unable to conduct a gender-specific analysis. Second, we prioritized the investigation of the most prevalent risk factors as potential mediators, the mediating effect between education and digestive tract diseases can’t be comprehensive explanation [46]. Third, after the Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment for multiple testing, the estimated causal effects of WHR on peptic ulcer and fasting insulin on cholelithiasis, with education adjustment, turned borderline significant. To ensure the reliability and applicability of these findings, further validation using separate cohorts in future analyses is warranted. Firth, the direct impact of education on NAFLD weakened towards null with adjustment for intelligence and cognition, but this may be bias by limited sample size. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct large-scale studies in the future. Fifth, The study primarily used data from European ancestry populations, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other ethnic groups. Finally, while Mendelian randomization helps minimize confounding, it cannot completely rule out all potential confounding factor.

Conclusions

This MR study provided a detailed analysis of the causal protective effect of education on the risk of six digestive tract diseases, independent of intelligence and cognition. It also identified five causal mediators, including indicators of adiposity, fasting insulin and major depression, that explain the relationship between education and digestive tract diseases. By offering causal evidence, this study contributes valuable insights into the etiology of digestive tract diseases and advocates for the enhancement of educational attainment and the reduction of educational inequity as promising strategies to mitigate the prevalence and burden of gastrointestinal disorders. Additionally, effective management of the identified causal mediators holds potential in this regard.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the authors and participants of all GWASs from which we used summary statistics data.

Abbreviation

- MR

Mendelian randomization

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- IVW

Inverse variant weighted

- MR-PRESSO

MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence intervals

- MVPA

Moderate to vigorous physical Activity

- WHR

Waist-to-hip-ratio

- BMI

Body mass index

- BF%

Body fat percentage

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- WM

Weighted median

Author contributions

YW and YB designed this study. YW conducted analyses and drafted the manuscript. LHZ directed the analytical strategy and supervised the study from conception to completion. YW, YB, YLW and FJ performed the data analyses. YW and LHZ revised the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yudan Wang and Yanping Bi contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and cognitive functioning across the Life Span. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020;21(1):6–41. 10.1177/1529100620920576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs I, Wollny A. Personal values, trait emotional intelligence, and mental health problems. Scand J Psychol. 2022;63(2):155–63. 10.1111/sjop.12785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rey E, Moreno Ortega M, Garcia Alonso MO, Diaz-Rubio M. Constructive thinking, rational intelligence and irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(25):3106–13. 10.3748/wjg.15.3106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Yang X, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J, Lu M. Association of educational attainment with esophageal cancer, Barrett’s esophagus, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, and the mediating role of modifiable risk factors: a mendelian randomization study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1022367. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1022367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Bryois J, de Leeuw CA, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):912–9. 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li LF, Chan RL, Lu L, Shen J, Zhang L, Wu WK, et al. Cigarette smoking and gastrointestinal diseases: the causal relationship and underlying molecular mechanisms (review). Int J Mol Med. 2014;34(2):372–80. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan S, Chen J, Ruan X, Sun Y, Zhang K, Wang X et al. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and 24 gastrointestinal diseases: mendelian randomization analysis. Elife. 2023;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kim MS, Song M, Kim S, Kim B, Kang W, Kim JY, et al. Causal effect of adiposity on the risk of 19 gastrointestinal diseases: a mendelian randomization study. Obes (Silver Spring). 2023;31(5):1436–44. 10.1002/oby.23722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strand BH, Tverdal A. Trends in educational inequalities in cardiovascular risk factors: a longitudinal study among 48,000 middle-aged Norwegian men and women. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(10):731–9. 10.1007/s10654-006-9046-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies NM, Hill WD, Anderson EL, Sanderson E, Deary IJ, Davey Smith G. Multivariable two-sample mendelian randomization estimates of the effects of intelligence and education on health. Elife. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(1):1–22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanderson E. Multivariable mendelian randomization and mediation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021;11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Sanderson E, Davey Smith G, Windmeijer F, Bowden J. An examination of multivariable mendelian randomization in the single-sample and two-sample summary data settings. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(3):713–27. 10.1093/ije/dyy262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, et al. Strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology using mendelian randomization: the STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA. 2021;326(16):1614–21. 10.1001/jama.2021.18236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50(8):1112–21. 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou W, Zhao Z, Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, LeFaive J, Gagliano Taliun SA, et al. Scalable generalized linear mixed model for region-based association tests in large biobanks and cohorts. Nat Genet. 2020;52(6):634–9. 10.1038/s41588-020-0621-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie J, Huang H, Liu Z, Li Y, Yu C, Xu L, et al. The associations between modifiable risk factors and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2023;77(3):949–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Yang H, Li H, He C, Yang L, Lv G. Insights into modifiable risk factors of cholelithiasis: a mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2022;75(4):785–96. 10.1002/hep.32183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Kong L, Ye C, Dou C, Zheng J, Xu M, et al. Causal impacts of educational attainment on chronic liver diseases and the mediating pathways: mendelian randomization study. Liver Int. 2023;43(11):2379–92. 10.1111/liv.15669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klimentidis YC, Raichlen DA, Bea J, Garcia DO, Wineinger NE, Mandarino LJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK Biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(6):1161–76. 10.1038/s41366-018-0120-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Vegte YJ, Said MA, Rienstra M, van der Harst P, Verweij N. Genome-wide association studies and mendelian randomization analyses for leisure sedentary behaviours. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1770. 10.1038/s41467-020-15553-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane JM, Jones SE, Dashti HS, Wood AR, Aragam KG, van Hees VT, et al. Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):387–93. 10.1038/s41588-019-0361-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(3):343–52. 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dashti HS, Jones SE, Wood AR, Lane JM, van Hees VT, Wang H, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic loci for self-reported habitual sleep duration supported by accelerometer-derived estimates. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1100. 10.1038/s41467-019-08917-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SE, Lane JM, Wood AR, van Hees VT, Tyrrell J, Beaumont RN, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):343. 10.1038/s41467-018-08259-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):237–44. 10.1038/s41588-018-0307-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Yengo L, Sidorenko J, Kemper KE, Zheng Z, Wood AR, Weedon MN, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(20):3641–9. 10.1093/hmg/ddy271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, Ferreira T, Locke AE, Mägi R, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518(7538):187–96. 10.1038/nature14132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Spracklen CN, Marenne G, Varshney A, Corbin LJ, Luan J, et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat Genet. 2021;53(6):840–60. 10.1038/s41588-021-00852-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, Kanoni S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1274–83. 10.1038/ng.2797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meddens SFW, de Vlaming R, Bowers P, Burik CAP, Linnér RK, Lee C, et al. Genomic analysis of diet composition finds novel loci and associations with health and lifestyle. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(6):2056–69. 10.1038/s41380-020-0697-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Chen Z, Pärna K, van Zon SKR, Snieder H, Thio CHL. Mediators of the association between educational attainment and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a two-step multivariable mendelian randomisation study. Diabetologia. 2022;65(8):1364–74. 10.1007/s00125-022-05705-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yavorska OO, Burgess S. MendelianRandomization: an R package for performing mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(6):1734–9. 10.1093/ije/dyx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(5):377–89. 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):693–8. 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter AR, Sanderson E, Hammerton G, Richmond RC, Davey Smith G, Heron J, et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: current methods and challenges for implementation. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(5):465–78. 10.1007/s10654-021-00757-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Kong L, Ye C, Dou C, Zheng J, Xu M et al. Causal impacts of educational attainment on chronic liver diseases and the mediating pathways: mendelian randomization study. Liver Int. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Mao X, Mao S, Sun H, Huang F, Wang Y, Zhang D, et al. Causal associations between modifiable risk factors and pancreatitis: a comprehensive mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1091780. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1091780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koutny F, Aigner E, Datz C, Gensluckner S, Maieron A, Mega A et al. Relationships between education and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Adewuyi EO, O’Brien EK, Porter T, Laws SM. Relationship of Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease with Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders: A Large-Scale Genetic Overlap and Mendelian Randomisation Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.The Lancet Public H. Education: a neglected social determinant of health. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(7):e361. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30144-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallan A, Bomme M, Hveem K, Møller-Hansen J, Ness-Jensen E. Risk factors on the development of new-onset gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. A population-based prospective cohort study: the HUNT study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(3):393–400. quiz 1. 10.1038/ajg.2015.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Johnsen R, Hveem K, et al. Relation between gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and socioeconomic factors: a population-based study (the HUNT study). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(9):1029–34. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Ye C, Kong L, Zheng J, Xu M, Xu Y, et al. Independent Associations of Education, Intelligence, and Cognition with Hypertension and the Mediating effects of Cardiometabolic Risk factors: a mendelian randomization study. Hypertension. 2023;80(1):192–203. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solar I, Santos LAO, Yamashita LM, Barret JS, Nagasako CK, Montes CG, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: associations between FODMAPS intake, problematic foods, adiposity, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):637–41. 10.1038/s41430-018-0331-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruan X, Chen J, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Wang X, et al. Depression and 24 gastrointestinal diseases: a mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13(1):146. 10.1038/s41398-023-02459-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang S, Xu Z, Gao Y, Wu Y, Li Z, Liu H, et al. Bidirectional crosstalk between stress-induced gastric ulcer and depression under chronic stress. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51148. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agirman G, Yu KB, Hsiao EY. Signaling inflammation across the gut-brain axis. Science. 2021;374(6571):1087–92. 10.1126/science.abi6087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milaneschi Y, Simmons WK, van Rossum EFC, Penninx BW. Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(1):18–33. 10.1038/s41380-018-0017-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilton C, Sabaratnam R, Drakesmith H, Karpe F. Iron, glucose and fat metabolism and obesity: an intertwined relationship. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47(7):554–63. 10.1038/s41366-023-01299-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Metcalf PA, Sharrett AR, Folsom AR, Duncan BB, Patsch W, Hutchinson RG, et al. African american-white differences in lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins, by educational attainment, among middle-aged adults: the atherosclerosis risk in communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(8):750–60. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Addey T, Alegre-Díaz J, Bragg F, Trichia E, Wade R, Santacruz-Benitez R, et al. Educational and social inequalities and cause-specific mortality in Mexico City: a prospective study. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(9):e670–9. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00153-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian Randomization Jama. 2017;318(19):1925–6. 10.1001/jama.2017.17219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.León-Muñoz LM, Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, Guallar-Castillón P, Regidor E, López-García E, Martínez-Gómez D, et al. Contribution of lifestyle factors to educational differences in abdominal obesity among the adult population. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):836–43. 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang Z, Shi J, Liu W, Wei S, Zhang Z. The influence of educational level in peri-menopause syndrome and quality of life among Chinese women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36(11):991–6. 10.1080/09513590.2020.1781081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross S, Armas Rojas N, Sawatzky J, Varona-Pérez P, Burrett JA, Calderón Martínez M, et al. Educational inequalities and premature mortality: the Cuba prospective study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(11):e923–31. 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00237-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.