Abstract

Aim

Despite the serious consequences of exposure to high job demands for nursing staff, few studies have identified pathways that could reduce the influence of high job demands on burnout. The current study aimed to exaime whether a stress mindset mitigates the positive relationship between job demands and burnout.

Design

A cross‐sectional survey was adopted and data were collected employing self‐report questionnaires.

Methods

A convenience sample of 676 nurses recruited from six regional hospitals in China were invited to complete a demographic questionnaire, the Psychological Job Demand Scale, the Stress Mindset Scale and the Burnout Scale. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis and simple slope analysis were used to examine the moderating role of stress mindset.

Results

Higher job demands were positively linked to burnout, and stress mindset was negatively linked to burnout. Stress mindset moderated the positive relationship between job demands and burnout. Specifically, compared to nurses with a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset, the relationship will be smaller for nurses holding a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset.

Patient or Public Contributions

Based on these findings, nursing leaders should foster nurses' stress‐is‐enhancing mindset, which can ameliorate the adverse effect of job demands.

Keywords: burnout, job demand, job demand‐control model, nurses, stress mindset

1. INTRODUCTION

Job‐induced burnout often stems from the stress inherent in most occupations (Peasley et al., 2020; Solomonidou & Katsounari, 2020; Travis et al., 2015). A number of studies have identified certain professional groups that are more vulnerable to burnout. Unsurprisingly, nursing staff are considered to be particularly susceptible to the danger of burnout, as their professions are stressful and emotionally demanding (Grace & VanHeuvelen, 2019; Labrague et al., 2016; Lewis & Cunningham, 2016). Occupational stress in the nursing context is ubiquitous, typical stressors include long working hours, heavy workloads, interpersonal relationships with colleagues, as well as dealing with life‐ and death‐ situations (Bae, 2021; Bae & Yoon, 2014; İlhan et al., 2006; Laranjeira, 2011), all of which often make their jobs physically and emotionally taxing. Besides work‐related demands, lack of control over the work schedule has been identified as a contributing factor to role stress for nurses at work and a predisposing factor for burnout (Teclaw & Osatuke, 2014). In China, up to 50% of hospital nurses were experiencing moderate and high levels of burnout (Guo et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2012). Consequently, nurses burnout is highlighted as the most pressing issue and problem in healthcare setting. According to the most commonly used definition, burnout is a psychological syndrome including emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 1996) and negatively affects nurses' health and performance (Bonetti et al., 2019). Burnout has been related to many detrimental individual and organizational outcomes, such as decreased productivity and job satisfaction, disengagement and reduced organizational commitment, increased absenteeism and turnover intentions (Han et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2013; Lee & Akhtar, 2011; Travis et al., 2015), and consequently jeopardize patient care. Due to the prevalence of nurse burnout, nursing managers should identify pathways that buffer against the negative effects of burnout.

Most traditional burnout research has focused on the contextual and situational factors contributing to burnout. For example, existing studies have clearly demonstrated that high job demands are one of the strongest, best established antecedents of burnout (Crawford et al., 2010). Increased workload demands, higher time constraints, and insufficient time with family are three typical job demands in the nursing profession (Bakhoum et al., 2021; Hayward et al., 2016). Although situational factors such as heavy workloads and lack of leadership support have been found to be predictive of burnout, not all people in the same work context develop burnout. Even when sharing a working environment, some nurses experience lower burnout than others. This suggests that there are other protective factors against nurse stress and burnout. As such, job demands are not inherently stressful for all nurses. However, little research has been concerned with individual differences that could explain employees' perceptions of their job stressors. Recent research has revealed striking individual differences among people in their beliefs about the nature of stress (Crum et al., 2013, 2017). Research in clinical psychology indicates that a stress mindset, that is, whether individuals believe stress is detrimental or beneficial, can moderate the negative consequences of challenging and demanding environments (Huebschmann & Sheets, 2020). Specifically, a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset – the extent to which one believes that stress has enhancing consequences – can help to maintain an individual's positive outlook and mood when they encounter high levels of stress or demanding working conditions (Mansell, 2021). Despite the fact that nurses are a population for which stress is common and mental health concerns are rising, stress mindset has not been closely examined in a nursing population. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate stress mindset among nurses, and to explore whether stress mindset moderates the relationship between job demands and burnout. From a practical perspective, concerning on this specific individual level factor is relevant, since a stress mindset is amenable to change, and consequently, interventions to foster this belief are available.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Burnout and high job demands

Burnout is a central concept in a healthcare setting (La Torre et al., 2021), and research on its determinants and consequences has strong practical relevance for human resources management. Maslach et al. (1996) defined burnout as ‘a state of exhaustion in which one is cynical about the value of one's occupation and doubtful of one's capacity to perform’. Burnout is a multi‐facet construct comprised of three distinct dimensions. The three dimensions are emotional exhaustion, involving feelings of being overextended and drained personal emotional resources, depersonalization refers to a distanced and disillusioned attitude toward the job and others on the job, and decreased sense of personal accomplishment refers to a loss of or a decline in feeling competent and successful at work. Working in a healthcare institution has been related to higher levels of burnout than working in other occupations (La Torre et al., 2021; Woo et al., 2020). Burnout appears common among nurses, with prevalence estimates ranging from 40% to 50%. For example, Renzi et al. (2012) found that 50% of registered nurses had elevated scores on emotional exhaustion. A recent study of five countries has found that 40% of nurses experience high levels of burnout, and that the majority of nurses intend to leave their profession because of burnout (Crawford & Daniels, 2014).

Burnout represents a chronic ongoing reaction to severe work‐related tension and a negative affective response to prolonged stress (Toppinen‐Tanner et al., 2009). Each component of burnout may result as a consequence of chronic work stress. In the literature, the link between stressors and burnout is well documented, suggesting that exposure to stressors can arouse psychological, physiological and behavioural stress responses, which may in turn lead to burnout or impaired health (Newman et al., 2020; O'Callaghan et al., 2019). Job demands are generic sources of stress common to different professions. Job demands are defined as a set of psychological stressors in the workplace, such as high workload, increased time pressure, role ambiguity and high responsibility (Lavigne et al., 2014). Being unable to efficiently deal with these stressors, some nurses are becoming frustrated, dissatisfied, demotivated, physically and psychologically depleted which results in the onset of burnout syndrome (Akkoç et al., 2020). It is important to note that these stressors are psychological demands and not physical ones. Although job demands are inherently stressful, they are not necessarily negative, they may be viewed as stressors when meeting those demands requires additional effort while the employee has not adequately recovered from previous work sequences. In other words, stress occurs if job demands are perceived as threatening or challenging and as exceeding personal resources. Still, because it is often assumed that job demands only lead to resource loss, job demands have consistently been linked to higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, as these demands require cognitive resources to overcome obstacles (Smout et al., 2021). Therefore, job demands are theorized to result in negative outcomes.

Nursing is recognized unquestionably as a highly demanding profession (Scully, 2015), characterized by a high rate of burnout and dropout. Nurses experiencing more long‐term stress may display emotional exhaustion or depressive symptoms. Prominent job demands related to nursing work include heavy workload, uncertainty surrounding treatment, dealing with death and dying, and addressing the emotional and spiritual needs of patients and their families (Rushton et al., 2015). Researchers have found positive relationships between job demands and burnout in the nursing profession. For example, García‐Sierra et al. (2016) demonstrated that job demands were positively correlated with burnout among nurses (García‐Sierra et al., 2016). A longitudinal study of nurses found that increases in depersonalization and decreases in personal accomplishment at Time 2 were predicted by increases in job demands at Time 2 (Pisanti et al., 2016). Additionally, increased job demands were associated with musculoskeletal disorders and burnout among emergency nurses (Sorour & El‐Maksoud, 2012). High job demands lead to fatigue because resources such as time and energy are exhausted, which in turn leads to burnout. As well as the demanding workload, nurses typically have little control over their work. Job control refers to the extent to which the individual can exert influence over tasks. Low job control at work may not only limit nurses' ability to act on their moral decisions (Karanikola et al., 2013), but also reduce their job satisfaction (De Los Santos & Labrague, 2021). Therefore, we hypothesizs that higher job demands would be positively associated with burnout. Given the positive consequences of high job demands on nurse burnout, it is valuable to provide nurses with practical guidelines that may help them diminish these effects.

2.2. Stress mindset as a moderater

Much is known about stress and its resulting strain. Although stress is often described as an inherently negative experience, experiencing stress may not always be deleterious for personal development and well‐being. Conversely, stress can be perceived positively and used constructively in some circumstances. Transactional theory of stress highlights that behavioural responses to stressors are partly determined by the way people appraise them (Courtright et al., 2014). Specifically, the same environmental stimulus such as high job demands may engender different reactions from different individuals depending on how individuals evaluate it (Yan et al., 2021). A growing body of literature has indicated that individuals' beliefs about stress may play an important role in shaping the stress responses that an individual experiences in a stressful situation (Crum et al., 2017). As the clinical environment continually places nurses under conditions of stress, it is necessary to study how a stress mindset is associated with burnout. Stress mindset is defined as the extent to which an individual holds the mindset that stress has enhancing versus debilitating outcomes (Crum et al., 2013). The belief that stress can have positive effects on stress‐related outcomes is labelled as a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset, and the belief that stress has negative effects is labelled as a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset. Stress mindset is an important construct to stressful life events, because, unlike other personal resources such as psychological capital, it directly relates to subjective beliefs about the nature of stress. Stress mindset is also distinct conceptually and empirically from other domains of mindsets, and may be particularly associated with mental health. Most importantly, stress mindset has been proven to be malleable and can be developed through interventions.

Empirical evidence has shown that having a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset is associated with health‐related outcomes (Hagger et al., 2020), including decreases in anxiety and depressive symptoms. Additionally, having a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset is associated with job performance, job satisfaction, and turnover (Kim et al., 2020). Individuals who hold a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset exhibit more adaptive physiological responses and more approach‐oriented behavioural responses when faced with stressful events compared to those have a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset (Crum et al., 2013). Furthermore, when expecting a high workload, those with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset are typically more prone to engage in planning and scheduling. Therefore, nurses with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset may be better able to create pleasant emotional environments.

Stress mindset also acts as a moderator of the relationships between stressful experiences and well‐being. Some empirical studies have found that the relationships between job‐related stressors and work burnout and depression are weaker among people with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset. For example, Hammond et al. (2020) examined stress mindset as a moderator of the effects of work–family conflict and enrichment on job satisfaction and turnover intentions. The results showed that stress‐is‐enhancing mindset mitigated the effects of work–family conflict on job satisfaction and turnover intentions, and strengthened the effect of work‐family enrichment on job satisfaction. Similarly, using daily diaries, Laferton et al. (2019) investigated the effects of stress mindset on affect in the daily stress process, and found that university students with high negative stress beliefs had higher negative affect when experiencing social stress; for students with low negative stress beliefs, the relationship between social stress and negative affect was smaller. Huebschmanna and Sheets (Huebschmann & Sheets, 2020) found that a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset buffers the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms in college students who had high levels of stress. Taken together, there is evidence that stress mindset may act as a moderator to buffer adverse influences of stressful experiences. It may therefore be assumed that the positive association between job demands and burnout will be smaller if nurses have a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset.

2.3. Job demand–control model

This study is informed by the job demand–control (JD‐C) model, which has been used to explain the relationship between job demands and job strain in the work domain (Hessels et al., 2017). The job demand‐control model is currently the most popular framework in occupational psychology to explain employee well‐being and motivation in the context of high job demands. The job demand‐control model builds on the premise that work characteristics, which are specific to every occupation, can generally be categorized into two dimensions: job demands and job control. Job demands are defined as psychological stressors involved in accomplishing the workload, and have been mainly operationalized in terms of work pressure, role conflicts or quantitative workload (Falco et al., 2017). Bakker et al. (2003) posit that not all job demands are inherently unfavourable, they would turn into job stressors when satisfying such demands requires high effort from which the individual has not adequately recovered. Typically, high job demands have been linked to various indicators of job strain, including anxiety and depressive symptoms (Salmela‐Aro & Upadyaya, 2018). Contrary to job demands, job control refers to the extent to which people have the authority to make decisions and utilize skills concerning the job. Having high decision latitude has been consistently associated with higher performance and lower strain (Alarcon, 2011). Therefore, job demands increase work‐related stress, job control not only reduces work‐related stress but also mitigates the influence of job demands on stress (Hessels et al., 2017).

Within the framework of the JD‐C model, although the focus has been on the main effects of job demands and job control, theoretically, it could be argued that it is the interaction between job demands and job control that is most crucial in the development of job strain and motivation. Accordingly, the JD‐C model proposes two distinct hypotheses: strain and activation hypothesis. The strain hypothesis postulates that strain will be highest in jobs characterized by the combination of high job demands and low job control. According to the JD‐C model, burnout is a prevalent phenomenon among nurses due to the interaction between high job demands and low job control. The activation hypothesis states that the combination of high demands and high job control may result in an increase in intrinsic work motivation, learning and personal growth. Furthermore, high job control can compensate or mitigate the impact of job demands on burnout. Specifically, the adverse impact of high demands is diminished or even eliminated in jobs providing high levels of control. The idea behind this buffering effect is that high levels of job control provide the means for successfully dealing with high job demands. For example, having autonomy or having opportunity for personal control has been shown to play a crucial role in lowering vulnerability to burnout (Fernet et al., 2014), while in high‐strain jobs providing only low levels of control, high demands can fully exert their negative effects. According to the activation hypothesis of the JD‐C model, job control may function as a moderator in the relationship between job demands and strain. Evidence from several studies also suggests that job resources have a direct negative relationship with burnout (Alarcon, 2011).

Although research on the JD‐C model has mainly concentrated on job characteristics, the recent addition of personal resources into the model is a noteworthy contribution. For example, a limited number of studies have examined the role of job‐related control beliefs, such as locus of control, resilience, coping, and self‐efficacy beliefs, which have the potential to buffer the relationships between job demands and occupational outcomes (Rushton et al., 2015; Gilbert et al., 2017; Jarden et al., 2018). The combination of high job demands and high personal resources represents the buffer effect and proposes that although working under demanding conditions, high levels of personal resources may prevent the occurrence of job strain. In this study, we chose to examine the stress mindset as a personal resource, which acts as a buffer in the relationship between job demands and burnout. Specifically, a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset may serve as a high job control that mitigates the loss of resources in the face of high job demands. A stress‐is‐enhancing mindset can help one effectively cope with stress and remain determined, focused, confident, and in control under pressure, and quickly recover from stress. Therefore, the relationship between job demands and burnout can be moderated by stress mindset.

3. STUDY AIM AND HYPOTHESES

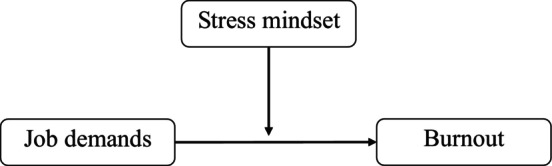

Attempting to understand the predictors of burnout and how psychological factors of staff can moderate the negative effects of job demands could potentially help organizations to increase the quality of health care. As the JD‐C model proposes that job burnout is the result of the interplay between job demands and job control, the current study aims to examine the relationships between job demands, stress mindset and burnout in a sample of nurses. Based on past theory and research, it is hypothesized that job demands would be positively related to burnout (Hypothesis 1), and that stress mindset will be negatively related to burnout (Hypothesis 2). A core aim of this study is to explore the potential moderating role of stress mindset on the relationship between job demands and burnout. We anticipated that individuals' perceived job demands will be less strongly associated with burnout among nurses with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset (Hypothesis 3). In other words, nurses with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset are expected to experience lower levels of burnout if they are experiencing higher versus lower levels of job demands. Figure 1 illustrates the central aim of this study.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized moderation model.

4. METHODS

4.1. Study design

This study employed a cross‐sectional design. Data for this study was collected through the online ‘Questionnaire Star’ platform.

4.2. Setting and participants

Convenience sampling was employed for data collection between May and July 2022. Participants were registered nurses enrolled from six regional hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China. The inclusion criteria were as follows: having a full‐time, ongoing contract; being a registered nurse who worked more than 1 year; consenting to participate in the study. A total of 700 nurses participated in this study, 24 nurses failed to complete the survey. This resulted in the final sample of 676 participants, giving a response rate of 96.57%. All data analyses were conducted after data collection concluded.

4.3. Measurement of the variables

The questionnaire consisted of the following: Job Demand Scale, Stress Mindset Measure, Maslach Burnout Inventory, and a section with questions on socio‐demographic information that were developed for present research.

4.3.1. Socio‐demographic characteristics

A self‐administered questionnaire was designed to collect the socio‐demographic characteristics of participants, such as gender, age, marital status, educational level and job tenure.

4.3.2. Job demands

The level of participants' perceived job demands were measured with the Psychological Job Demand Scale (PJDS), which was one of the subscales of the Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire modified by Cheng et al. (2003). The PJDS consists of five items on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The score for job demands was calculated by averaging all item responses. High scores indicate greater psychological job demand. Cronbach's α for our sample was 0.94.

4.3.3. Stress mindset

The degree to which respondents perceived stress as enhancing or debilitating was assessed with the Stress‐Mindset Measure (SMM) developed by (Crum et al., 2013). The SMM is a unidimensional and bipolar scale, consisting of eight items, with four items measuring a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset and other four items measuring a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset. The responses are given on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items measuring the stress‐is‐debilitating mindset are reversed. The items are averaged and combined into a single scale, with higher scores referring to stress‐is‐enhancing mindset and lower scores to stress‐is‐debilitating mindset. Cronbach's α of stress‐is‐enhancing and stress‐is‐debilitating mindset subscales for our sample were 0.87 and 0.88, respectively.

4.3.4. Burnout

The participants' experiences of burnout were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981), which consisted of emotional exhaustion (5 items), depersonalization (5 items) and low sense of personal accomplishment (6 items). All items are scored on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The score for burnout was calculated by averaging all item responses. High scores indicate greater burnout. Cronbach's α of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and low sense of personal accomplishment subscales for our sample were 0.85, 0.82 and 0.87, respectively.

4.4. Ethical considerations

Before data collection, ethical approval for this study was granted from the Ethical Committee of Shaoxing University. Nurses received an explanation of the study purposes and reassurance of anonymity, confidentiality, and use of their responses only for the aim of the research. All participants voluntarily took part in this survey and were told that they could withdraw from the study without any reason at any time.

4.5. Procedure

Prior to data collection, we contacted the healthcare administrators or nursing leaders to gain research access. Upon receipt of the approval, we randomly selected a part of nurses working in the healthcare institutions as participants. The survey consisted of approximately 700 nurses. Before starting the survey, we fully explained the research purpose and contents, and then guided them to complete an anonymous online questionnaire survey. Participants did not receive any compensation.

4.6. Data analysis

Mean values (M) and standard deviation (SD) were utilized to characterize the studied population. One‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and independent t‐tests were applied to check for group differences in job demands, stress mindset and burnout according to the general characteristics. Pearson correlations were calculated to determine the interrelationships between study variables. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to explore the moderating role of stress mindset. Burnout was treated as a dependent variable, job demand was treated as an independent variable, and stress mindset was treated as a moderator variable. Demographic characteristics such as age and gender, were entered in the first step as control variables. In the second step, job demands and stress mindset were entered as independent variables. In the third step, the interaction of job demands and stress mindset was entered. When the interaction is significant, the moderating effect is found. Bootstrapping is reported alongside the regression models. To understand this interaction more clearly, a simple slope analysis suggested by Aiken and West was conducted. All analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS 20.0 software.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Sample demographics

A total of 676 nurses aged 25–54 completed the survey. The majority of nurses were female (97.6%) and married (76%), with a mean age of 35.84 years and working experience of 16.37 years. Of this group, most nurses (88.7%) obtained a bachelor's degree.

5.2. Differences in job demands, stress mindset and burnout according to characteristics

The means were 3.43 (SD = 0.83) for job demands, 3.36 (SD = 0.73) for stress mindset and 3.10 (SD = 0.76) for burnout (Table 1). Table 2 displays a set of independent sample t‐test and one‐way ANOVA comparisons results for the difference in job demands, stress mindset and burnout across gender, marital status, age, educational level and job tenure. An independent‐samples t‐test revealed a marital status difference in job demands (t = 2.44, p = 0.015). Married nurses perceived higher job demands. A one‐way ANOVA indicated that job tenure had effect on job demands (F = 2.89, p = 0.022). Significant differences in stress mindset were found across the age (F = 5.49, p = 0.001), educational level (t = 2.11, p = 0.035) and job tenure (F = 5.61, p < 0.001). No significant group differences in burnout were identified.

TABLE 1.

Means, standard deviations and correlations between variables.

| Variable | M (SD) | Job demands | Stress mindset | Burnout |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job demands | 3.43 (0.83) | 1.00 | ||

| Stress Mindset | 3.36 (0.73) | −0.22** | 1.00 | |

| Burnout | 3.10 (0.76) | 0.26** | −0.43** | 1.00 |

p < 0.01.

TABLE 2.

Nurses' demographics and the level of variable (N = 676).

| Characteristics | Job demands (M ± SD) | Stress minset (M ± SD) | Burnout (M ± SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | t/F | p | t/F | p | t | p | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 16 (2.4) | 5.53 (0.78) | 0.47 | 0.636 | 3.22 (1.06) | −0.78 | 0.433 | 3.37 (0.88) | 1.45 | 0.147 |

| Female | 660 (97.6) | 3.43 (0.83) | 3.36 (0.72) | 3.09 (0.75) | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 514 (76.0) | 3.48 (0.83) | 2.44 | 0.015 | 3.37 (0.75) | 0.97 | 0.33 | 3.10 (0.76) | 0.37 | 0.71 |

| Single/divorced/widow | 162 (24.0) | 3.29 (0.79) | 3.31 (0.66) | 3.08 (0.75) | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| <30 years | 250 (37.0) | 3.32 (0.80) | 2.52 | 0.057 | 3.28 (0.68) | 5.49 | 0.001 | 3.06 (0.75) | 1.46 | 0.223 |

| 31 ~ 39 years | 189 (28.0) | 3.52 (0.81) | 3.29 (0.72) | 3.20 (0.79) | ||||||

| 40 ~ 49 years | 156 (23.1) | 3.48 (0.86) | 3.40 (0.77) | 3.06 (0.74) | ||||||

| 50 ~ 59 years | 81 (12.0) | 3.47 (0.87) | 3.64 (0.73) | 3.07 (0.76) | ||||||

| Educational level | ||||||||||

| Diploma | 76 | 3.27 (0.89) | −1.76 | 0.078 | 3.52 (0.73) | 2.11 | 0.035 | 2.95 (0.79) | −1.90 | 0.058 |

| Bachelor degree | 600 | 3.45 (0.82) | 3.34 (0.73) | 3.12 (0.75) | ||||||

| Job tenure | ||||||||||

| 1 ~ 5 years | 205 (30.3) | 3.29 (0.78) | 2.89 | 0.022 | 3.31 (0.65) | 5.61 | 0.000 | 3.05 (0.72) | 1.43 | 0.221 |

| 6 ~ 10 years | 187 (27.7) | 3.54 (0.79) | 3.22 (0.77) | 3.18 (0.82) | ||||||

| 11 ~ 15 years | 124 (18.3) | 3.52 (0.83) | 3.45 (0.74) | 3.14 (0.73) | ||||||

| 16 ~ 20 years | 52 (7.7) | 3.51 (0.85) | 3.32 (0.71) | 2.95 (0.67) | ||||||

| >21 years | 108 (16.0) | 3.39 (0.92) | 3.61 (0.73) | 3.07 (0.77) | ||||||

5.3. Correlation analysis between job demands, stress mindset and burnout

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations and correlations. All relationships were in the predicted direction: job demands were positively associated with burnout (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), stress mindset was negatively associated with job demands (r = −0.22, p < 0.01) and burnout (r = −0.43, p < 0.01).

5.4. Moderating role of stress mindset

In order to test for the interaction effect of job demands and stress mindset as a predictor of burnout, a multivariable linear regression model was conducted. Results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis were presented in Table 3. The demographic covariates were entered in the first step, but none of them emerged as predictors of burnout. In the second step, job demands and stress mindset were entered, and both were related to burnout and accounted for 20.7% of the variance in burnout. Burnout was positively predicted by job demands (β = 0.16, p < 0.01), and negatively predicted by stress mindset (β = 0.40, p < 0.01). This findings supported Hypothesis 1 and 2. In step 3, a mean‐centred interaction term between job demands and stress mindset was entered and found to be significant (β = 0.09, p < 0.01), accounting for 6.0% of the variance in burnout; job demand and stress mindset remained significant as well. This results indicated that stress mindset had a moderating effect in the relationship between job demands and burnout. To further interpret the interaction between job demands and burnout as predictor of burnout, tests of simple slopes were estimated at low (−1 SD from the mean) and high (+1 SD from the mean) values of stress mindset. As illustrated in Figure 2 and supported by simple slope analyses, high job demands had the strongest influence on burnout when nurses possessed a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset (t = 5.45, β = 0.49, p < 0.01). Again, for nurses with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset, the association between job demands and burnout was not significant (t = 1.37, β = 0.14, p > 0.01). In sum, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

TABLE 3.

The moderating role of stress mindset in the relationship between job demands and burnout.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | p | β | t | 95% CI | p | β | t | 95% CI | p | |

| Gender | −0.06 | −1.52 | [−0.75, 0.14] | 0.130 | −0.04 | −1.30 | [−0.59, 0.15] | 0.193 | −0.04 | −1.26 | [−0.58, 0.16] | 0.210 |

| Marital status | −0.01 | −0.32 | [−0.17, 0.14] | 0.750 | 0.01 | 0.15 | [−0.12, 0.15] | 0.879 | 0.01 | 0.16 | [−0.12, 0.15] | 0.871 |

| Age | 0.09 | 0.84 | [−0.08, 0.23] | 0.399 | 0.06 | 0.66 | [−0.09, 0.20] | 0.508 | 0.07 | 0.68 | [−0.09, 0.19] | 0.488 |

| Educational level | 0.07 | 1.77 | [−0.03, 0.35] | 0.077 | 0.03 | 0.82 | [−0.11, 0.24] | 0.412 | 0.03 | 0.83 | [−0.11, 0.24] | 0.406 |

| Job tenure | −0.11 | −0.97 | [−0.17, 0.05] | 0.331 | −0.02 | −0.23 | [−0.12,0.09] | 0.818 | −0.03 | −0.26 | [−0.12, 0.09] | 0.792 |

| Job demand | 0.16 | 4.55 | [0.07, 0.18] | 0.000 | 0.13 | 4.53 | [0.07, 0.18] | 0.000 | ||||

| Stress mindset | −0.40 | −11.20 | [−0.37, 0.25] | 0.000 | −0.32 | −11.02 | [−0.37, −0.25] | 0.000 | ||||

| Job demand × Stress mindset | 0.09 | 3.72 | [0.03, 0.16] | 0.001 | ||||||||

| F | 1.34 | 26.68** | 32.79** | |||||||||

| R 2 | 0.003 | 0.21 | 0.27 | |||||||||

| ⊿R 2 | 0.207 | 0.06 | ||||||||||

FIGURE 2.

Moderating effect of stress mindset on the relationship between job demands and burnout.

6. DISCUSSION

The purposes of this study among Chinese nurses were to examine the impact of job demands on nurses' burnout, and to assess the extent to which stress mindset would be associated with burnout and whether stress mindset would moderate the effect of job demands on burnout. In line with the previous research (García‐Sierra et al., 2016; Sorour & El‐Maksoud, 2012), this study clearly demonstrated that high job demands were significantly related to burnout. As hypothesized, stress mindset was negatively related to burnout. Specifically, nurses who hold a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset experience lower levels of burnout. Furthermore, the findings of this study highlighted individual differences in responses to job demands. Among nurses with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset, the relationship between job demands and burnout is smaller. Our findings suggest that having a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset can be protective against the development of burnout in nurses experiencing job demands.

6.1. Burnout due to job demands

Results clearly supported the strain hypothesis of the job demand‐control model by showing that job demands were positively associated with burnout in the context of clinical workplaces. Many scholars have claimed that job demands may be interpreted as either a challenge or a threat (Bakker et al., 2003; Huhtala et al., 2021). Nonetheless, in work psychology, the effects of job demands have often been demonstrated empirically for various indicators of job strain, such as exhaustion. Prolonged exposure to stressful working environments has been associated with a great deal of adverse health consequences, including psychological morbidity, somatic distress, anxiety, and depression (Itzhaki et al., 2015; Ninaus et al., 2015). Nursing is viewed as one of the most stressful professionals. Frequently identified sources of stress include time pressure, role conflict, perceived low status of the profession, and working with difficult or unpleasant patients (Bae, 2021; Bae & Yoon, 2014; Laranjeira, 2011). Nurses experience intense, emotion‐laden interactions on a daily basis and have a great number of emotional demands. Higher job demands require nurses to sustain a consistently high level of mental, physical and emotional effort. This sustained effort depletes an individual's energy resources and comes with serious psychological costs. Our findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that workplace characteristics related to the exhaustion of psychological resources (Kirkcaldy & Martin, 2000), such as high job demands, may in turn lead to high levels of burnout.

6.2. Stress mindset and burnout

A small but growing body of literature has examined stress mindset and burnout. According to stress mindset theory, stress from work could not only exacerbate performance at work but may also adversely influence health status and well‐being (Crum et al., 2013). Therefore, stress mindset has the broadest relevance to both job satisfaction and burnout among nurses. As far as we know, this is the first research which directly addresses the relationship between stress mindset and burnout in the nursing context. The findings support our expectation in establishing a negative relationship between stress mindset and burnout. Empirical work in health psychology has obtained consistent results in relation to stress mindset and burnout in other professions, and it has been suggested that if employees hold a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset, they often underestimate stress, embrace stressful situations and see them as an opportunity to learn (Nguyen et al., 2020). They also see themselves as being able to adopt more problem‐focused coping strategies in dealing with stressors. Indeed, a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset has been demonstrated to positively associate with challenge in employees anticipating high‐workload situation. More importantly, adopting a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset may not only make stressful situations feel less emotionally difficult and physiologically taxing but also recruit and magnify emotional, cognitive and physiological attributes that may contribute to adaptive responses over the long‐term (Crum et al., 2017). A stress‐is‐enhancing mindset in turn has been discussed as acting as a potential resource against the development of burnout. Although nurses may have no power over their workloads, those with a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset feel more capable to perform their tasks and as a result, are unlikely to become overly anxious and depressed. This finding is also in accordance with Frederickson's (Fredrickson, 2004) view relating to the importance of personal resources in the promotion of health and well‐being.

6.3. Moderating effect of stress mindset

The issue of high job stress has received greater attention, especially among the nursing profession. However, stress assessment and response are not necessarily experienced the same way for all person. There is increasing evidence that individuals' behavioural responses to stressors are explained by their views of the nature of stress. The empirical research on the moderating effect of stress mindset in the context of occupational stress is still limited among healthcare employees. Central to our research findings is the examination in which stress mindset is postulated as a moderating variable in the relationship between job demands and burnout. Our results are in line with the activation hypothesis of the JD‐C model, that job control affects the relationship between job demands and burnout. A stress‐is‐enhancing mindset incorporates a belief that stress can be controlled and reduced, and even can produce favourable outcomes. According to the JD‐C model, a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset would further deteriorate the experience of resource loss, while a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset may facilitate the procurement of extra resources through more positive stress assessment and response (Hammond et al., 2020). Also, the present findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset acts as a buffer against the negative outcomes related to stress. Both Crum et al. (2013) and Hagger et al. (2020) emphasized that stress mindset plays an important role in coping with stressful situations. Overall, our findings suggest that stress mindset as a personal resource seems to play a constructive role in the prevention of job strain. Additionally, transactional stress theory provides a perspective for understanding the moderating role of stress mindset in the relationship between job demands and burnout (Courtright et al., 2014).

6.4. Implications for managers

From a positive psychology perspective, research on stress mindset is only beginning and can provide relevant contributions to the betterment of employees' lives in an intense and fast‐paced healthcare environment. Stress mindset not only has direct positive effects on health and well‐being but also mitigates negative effects of stressful experiences. This study highlighted that stress mindset as a personal resource can buffer the adverse effect of job demands on burnout. Considering that a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset can mitigate the development of burnout in nurses faced with high job demands, stress mindset intervention would be an efficient strategy. The growing body of research on mindsets advocates that one approach to meaningfully impact the stress response is to alter an individual's beliefs about the consequences of stress. Through stress mindset training, a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset can be fostered or increased and this positive stress mindset can enhance nurses' potential to develop more positive ways of coping when facing stressful events. Several scholars indicate that the most influential way to boost mindset is by enabling ‘mastery experiences.’

6.5. Limations and future directions

This study contains significant results, however, some limitations should be acknowledged and addressed. First, the majority of respondents were female, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although nonsignificance was found between gender and burnout, it is recommended that future studies should be conducted with the more balanced sample. In addition, our sample was limited to nurses in China. It seems plausible that there could be cultural differences in adherence to stress mindset. Second, all the variables in this study were measured using self‐report measures, our results run the risk of common method bias. Future researchers are advised to use more objective measurements in conjunction with self‐reports to obtain less biased data. Third, the current study used a cross‐sectional study design, thus our data did not allow us to draw inferences regarding causality. Future studies should adopt a longitudinal design, which could provide a better understanding of causal mechanisms and variations of job demands, stress mindset and burnout through time. Also, experimental research is necessary to address the causal inferences. This would involve the experimental manipulation of stress mindset. Future studies using intervention strategies is also needed to assess whether stress mindset training contributes to decreased burnout.

7. CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that differences in a person's dispositional attitude to view the nature of stress contribute to burnout under high job demands. Specifically, nurses who have a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset experience lower levels of burnout when confronted with high job demands than those nurses who have a stress‐is‐debilitating mindset. Accordingly, by cultivating a stress‐is‐enhancing mindset is a promising strategy for attenuating the effect of job demand on burnout. However, we would like to acknowledge that reactions to high job demands are likely to depend on other factors we did not incorporate into our model.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YYZ and TTJ: Research design. TTJ: Data collection. LGZ: Data analysis. YYZ and TTJ: Manuscript writing. LGZ: Manuscript revising.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by Humanities and Social Sciences of Ministry of Education Young Fund of China (20YJC880129).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Shaoxing University. Participants signed the informed consent form before being involved in this survey.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants who were involved in present research.

Zhou, Y. , Jin, T. , & Zhang, L. (2024). Can the stress be managed? Stress mindset as a mitigating factor in the influence of job demands on burnout. Nursing Open, 11, e70028. 10.1002/nop2.70028

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Akkoç, İ. , Okun, O. , & Türe, A. (2020). The effect of role‐related stressors on nurses' burnout syndrome: The mediating role of work‐related stress. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(2), 583–596. 10.1111/ppc.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta‐analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S. (2021). Intensive care nurse staffing and nurse outcomes: A systematic review. Nursing in Critical Care, 26(3), 457–466. 10.1111/nicc.12588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.‐H. , & Yoon, J. (2014). Impact of states' nurse work hour regulations on overtime practices and work hours among registered nurses. Health Services Research, 49(5), 1638–1658. 10.1111/1475-6773.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhoum, N. , Gerhart, C. , Schremp, E. , Jeffrey, A. D. , Anders, S. , France, D. , & Ward, M. J. (2021). A time and motion analysis of nursing workload and electronic health record use in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 47(5), 733–741. 10.1016/j.jen.2021.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. , Demerouti, E. , & Schaufeli, W. (2003). Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands‐resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(4), 393–417. 10.1080/13594320344000165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, L. , Tolotti, A. , Valcarengh, D. , Pedrazzani, C. , Barello, S. , Ghizzardi, G. , Graffigna, G. , Sari, D. , & Bianchi, M. (2019). Burnout precursors in oncology nurses: A preliminary cross‐sectional study with a systemic organizational analysis. Sustainability, 11(5), 1246. 10.3390/su11051246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y. , Luh, W.‐M. , & Guo, Y.‐L. (2003). Reliability and validity of the chinese version of the job content questionnaire in Taiwanese workers. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10(1), 15–30. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1001_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtright, S. H. , Colbert, A. E. , & Choi, D. (2014). Fired up or burned out? How developmental challenge differentially impacts leader behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 681–696. 10.1037/a0035790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, E. R. , LePine, J. A. , & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta‐analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. 10.1037/a0019364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J. , & Daniels, M. K. (2014). Follow the leader: How does “followership” influence nurse burnout? Nursing Management, 45(8), 30–37. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000451999.41720.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum, A. J. , Akinola, M. , Martin, A. , & Fath, S. (2017). The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 30(4), 379–395. 10.1080/10615806.2016.1275585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum, A. J. , Salovey, P. , & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. 10.1037/a0031201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Santos, J. A. A. , & Labrague, L. J. (2021). Job engagement and satisfaction are associated with nurse caring behaviours: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(7), 2234–2242. 10.1111/jonm.13384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco, A. , Dal Corso, L. , Girardi, D. , De Carlo, A. , & Comar, M. (2017). The moderating role of job resources in the relationship between job demands and interleukin‐6 in an Italian healthcare organization. Research in Nursing & Health, 41(1), 39–48. 10.1002/nur.21844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernet, C. , Lavigne, G. L. , Vallerand, R. J. , & Austin, S. (2014). Fired up with passion: Investigating how job autonomy and passion predict burnout at career start in teachers. Work & Stress, 28(3), 270–288. 10.1080/02678373.2014.93552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden‐and‐build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Sierra, R. , Fernández‐Castro, J. , & Martínez‐Zaragoza, F. (2016). Relationship between job demand and burnout in nurses: Does it depend on work engagement? Journal of Nursing Management, 24(6), 780–788. 10.1111/jonm.12382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, E. , Foulk, T. , & Bono, J. (2017). Building personal resources through interventions: An integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 214–228. 10.1002/job.2198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grace, M. K. , & VanHeuvelen, J. S. (2019). Occupational variation in burnout among medical staff: Evidence for the stress of higher status. Social Science & Medicine, 232, 199–208. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. , Luo, Y. , Lam, L. , Cross, W. , Plummer, V. , & Zhang, J. (2017). Burnout and its association with resilience in nurses: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1–2), 441–449. 10.1111/jocn.13952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger, M. S. , Keech, J. J. , & Hamilton, K. (2020). Managing stress during the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond: Reappraisal and mindset approaches. Stress and Health, 36(3), 396–401. 10.1002/smi.2969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. M. , Murphy, C. , & Demsky, C. A. (2020). Stress mindset and the work‐family interface. International Journal of Manpower, 42(1), 150–166. 10.1108/ijm-05-2018-0161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.‐S. , Han, J.‐W. , An, Y. S. , & Lim, S.‐H. (2014). Effects of role stress on nurses' turnover intentions: The mediating effects of organizational commitment and burnout. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 12(4), 287–296. 10.1111/jjns.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, B. , Douglas, C. , & Bonner, A. (2013). Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(5), 588–598. 10.1111/jonm.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, D. , Bungay, V. , Wolff, A. C. , & MacDonald, V. (2016). A qualitative study of experienced nurses' voluntary turnover: Learning from their perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(9–10), 1336–1345. 10.1111/jocn.13210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessels, J. , Rietveld, C. A. , & van der Zwan, P. (2017). Self‐employment and work‐related stress: The mediating role of job control and job demand. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(2), 178–196. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huebschmann, N. A. , & Sheets, E. S. (2020). The right mindset: Stress mindset moderates the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 33(3), 248–255. 10.1080/10615806.2020.17369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtala, M. , Geurts, S. , Mauno, S. , & Feldt, T. (2021). Intensified job demands in healthcare and their consequences for employee well‐being and patient satisfaction: A multilevel approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(9), 3718–3732. 10.1111/jan.14861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- İlhan, M. N. , Durukan, E. , Aras, E. , Türkçüoğlu, S. , & Aygün, R. (2006). Long working hours increase the risk of sharp and needlestick injury in nurses: The need for new policy implication. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 563–568. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki, M. , Peles‐Bortz, A. , Kostistky, H. , Barnoy, D. , Filshtinsky, V. , & Bluvstein, I. (2015). Exposure of mental health nurses to violence associated with job stress, life satisfaction, staff resilience, and post‐traumatic growth. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(5), 403–412. 10.1111/inm.12151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarden, R. J. , Sandham, M. , Siegert, R. J. , & Koziol‐McLain, J. (2018). Strengthening workplace well‐being: Perceptions of intensive care nurses. Nursing in Critical Care, 24(9), 15–23. 10.1111/nicc.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanikola, M. N. K. , Albarran, J. W. , Drigo, E. , Giannakopoulou, M. , Kalafati, M. , Mpouzika, M. , & Papathanassoglou, E. D. (2013). Moral distress, autonomy and nurse‐physician collaboration among intensive care unit nurses in Italy. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(4), 472–484. 10.1111/jonm.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. , Shin, Y. , Tsukayama, E. , & Park, D. (2020). Stress mindset predicts job turnover among preschool teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 78(5), 13–22. 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkcaldy, B. D. , & Martin, T. (2000). Job stress and satisfaction among nurses: Individual differences. Stress Medicine, 16(2), 77–89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, G. , Sestili, C. , Imeshtari, V. , Masciullo, C. , Rizzo, F. , Guida, G. , & Mannocci, A. (2021). Association of health status, sociodemographic factors and burnout in healthcare professionals: Results from a multicentre observational study in Italy. Public Health, 195, 15–17. 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J. , McEnroe‐Petitte, D. M. , Gloe, D. , Tsaras, K. , Arteche, D. L. , & Maldia, F. (2016). Organizational politics, nurses' stress, burnout levels, turnover intention and job satisfaction. International Nursing Review, 64(1), 109–116. 10.1111/inr.12347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laranjeira, C. A. (2011). The effects of perceived stress and ways of coping in a sample of Portuguese health workers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(11–12), 1755–1762. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne, G. L. , Forest, J. , Fernet, C. , & Crevier‐Braud, L. (2014). Passion at work and workers' evaluations of job demands and resources: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44(4), 255–265. 10.1111/jasp.12209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. S. Y. , & Akhtar, S. (2011). Effects of the workplace social context and job content on nurse burnout. Human Resource Management, 50(2), 227–245. 10.1002/hrm.20421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H. S. , & Cunningham, C. J. L. (2016). Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nursing Research, 65(1), 13–23. 10.1097/nnr.000000000000013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M. , Ruan, H. , Xing, W. , & Hu, Y. (2013). Nurse burnout in China: A questionnaire survey on staffing, job satisfaction, and quality of care. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(4), 440–447. 10.1111/jonm.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell, P. C. (2021). Stress mindset in athletes: Investigating the relationships between beliefs, challenge and threat with psychological wellbeing. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 57, 102020. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. , Jackson, S. , & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual. Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. , & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, C. , Jackson, J. , Macleod, S. , & Eason, M. (2020). A survey of stress and burnout in forensic mental health nursing. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 16(3), 161–168. 10.1097/jfn.0000000000000271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. T. T. , Neff, L. A. , & Williamson, H. C. (2020). The role of stress mindset in support provision. Personal Relationships, 27(1), 138–155. 10.1111/pere.12302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ninaus, K. , Diehl, S. , Terlutter, R. , Chan, K. , & Huang, A. (2015). Benefits and stressors‐ perceived effects of ICT use on employee health and work stress: An exploratory study from Austria and Hong Kong. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well‐Being, 10(1), 28838. 10.3402/qhw.v10.28838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, E. L. , Lam, L. , Cant, R. , & Moss, C. (2019). Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in Australian emergency nurses: A descriptive cross‐sectional study. International Emergency Nursing, 48, 100785. 10.1016/j.ienj.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peasley, M. C. , Hochstein, B. , Britton, B. P. , Srivastava, R. V. , & Stewart, G. T. (2020). Can't leave it at home? The effects of personal stress on burnout and salesperson performance. Journal of Business Research, 117(10), 58–70. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisanti, R. , van der Doef, M. , Maes, S. , Meier, L. L. , Lazzari, D. , & Violani, C. (2016). How changes in psychosocial job characteristics impact burnout in nurses: A longitudinal analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1082. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi, C. , Di Pietro, C. , & Tabolli, S. (2012). Psychiatric morbidity and emotional exhaustion among hospital physicians and nurses: Association with perceived job‐related factors. Archives of Environmental and Occupational Health, 67(2), 117–123. 10.1080/19338244.2011.578682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, C. H. , Batcheller, J. , Schroeder, K. , & Donohue, P. (2015). Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high‐intensity settings. American Journal of Critical Care, 24(5), 412–420. 10.4037/ajcc2015291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmela‐Aro, K. , & Upadyaya, K. (2018). Role of demands‐resources in work engagement and burnout in different career stages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 190–200. 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scully, N. J. (2015). Leadership in nursing: The importance of recognising inherent values and attributes to secure a positive future for the profession. Collegian, 22(4), 439–444. 10.1016/j.colegn.2014.09.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smout, M. F. , Simpson, S. G. , Stacey, F. , & Reid, C. (2021). The influence of maladaptive coping modes, resilience and job demands on emotional exhaustion in psychologists. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(1), 260–273. 10.1002/cpp.2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomonidou, A. , & Katsounari, I. (2020). Experiences of social workers in nongovernmental services in Cyprus leading to occupational stress and burnout. International Social Work, 65(1), 1–15. 10.1177/0020872819889386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorour, A. S. , & El‐Maksoud, M. M. A. (2012). Relationship between musculoskeletal disorders, job demands, and burnout among emergency nurses. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 34(3), 272–282. 10.1097/tme.0b013e31826211e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teclaw, R. , & Osatuke, K. (2014). Nurse perceptions of workplace environment: Differences across shifts. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(8), 1137–1146. 10.1111/jonm.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppinen‐Tanner, S. , Ahola, K. , Koskinen, A. , & Väänänen, A. (2009). Burnout predicts hospitalization for mental and cardiovascular disorders: 10‐year prospective results from industrial sector. Stress and Health, 25(4), 287–296. 10.1002/smi.1282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Travis, D. J. , Lizano, E. L. , & Mor Barak, M. E. (2015). “I'm so stressed!”: A longitudinal model of stress, burnout and engagement among social workers in child welfare settings. British Journal of Social Work, 46(4), 1076–1095. 10.1093/bjsw/bct205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo, T. , Ho, R. , Tang, A. , & Tam, W. (2020). Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 9–20. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. , Liu, L. , Sun, W. , Zhao, X. , Wang, J. , & Wang, L. (2012). Factors related to burnout among Chinese female hospital nurses: Cross‐sectional survey in Liaoning province of China. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(5), 621–629. 10.1111/jonm.12015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. , Kim, S. , Zhang, S. X. , Foo, M.‐D. , Alvarez‐Risco, A. , Del‐Aguila‐Arcentales, S. , & Yáñez, J. A. (2021). Hospitality workers' COVID‐19 risk perception and depression: A contingent model based on transactional theory of stress model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95(2), 102935. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.