Abstract

Deep neural networks have significantly advanced the field of medical image analysis, yet their full potential is often limited by relatively small dataset sizes. Generative modeling, particularly through diffusion models, has unlocked remarkable capabilities in synthesizing photorealistic images, thereby broadening the scope of their application in medical imaging. This study specifically investigates the use of diffusion models to generate high-quality brain MRI scans, including those depicting low-grade gliomas, as well as contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) and chest and lung X-ray images. By leveraging the DreamBooth platform, we have successfully trained stable diffusion models utilizing text prompts alongside class and instance images to generate diverse medical images. This approach not only preserves patient anonymity but also substantially mitigates the risk of patient re-identification during data exchange for research purposes. To evaluate the quality of our synthesized images, we used the Fréchet inception distance metric, demonstrating high fidelity between the synthesized and real images. Our application of diffusion models effectively captures oncology-specific attributes across different imaging modalities, establishing a robust framework that integrates artificial intelligence in the generation of oncological medical imagery.

Keywords: cancer, imaging, latent diffusion, generative diffusion, DreamBooth, stable diffusion, breast, lung, brain, cancer, medical imaging, MRI, chest, X-ray

Introduction

Medical imaging is challenged by data shortages, resulting from the high costs of image acquisition and processing, stringent data privacy regulations, and the rarity of certain diseases [1]. This shortage constrains the data available for training deep learning models, which in turn limits their performance and impedes the progress of computer-aided diagnostic systems.

Generative models, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs), have enhanced medical datasets by providing high-quality, realistic images. GANs have paved the way for innovative strategies to tackle a wide range of complex pathological image analysis tasks [2–14]. However, GANs often suffer from unstable training and produce images with limited diversity and quality [1], complicating their use in medical imaging where accurate diagnosis depends on subtle visual differences. This necessitates the need for reliable high-quality synthetic images to support effective computer-assisted diagnostic systems [15].

Diffusion models have revolutionized image generation [16], consistently surpassing GANs in performance [16]. These models excel across various domains by creating high-fidelity images from diverse datasets, including both multi- and unimodal sources like LAION-5B [17]. Their adoption in medical imaging represents a significant leap forward. Specifically, a denoising diffusion probabilistic model pipeline, a variant of diffusion models, was used to generate high-quality MRI images of brain tumors [18]. This application of diffusion models in 3D medical imaging has outperformed traditional 3D GANs, setting new benchmarks for the field. These models generate synthetic data that not only mirror ground truth clinical images but also address the critical shortages where real data are scarce or unavailable [19–31]. This capability is transformative for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and advancing treatment options by providing high-quality data that were previously unattainable. Our study makes a unique contribution by using these models to synthesize medical imaging data for rare diseases, an important yet underexplored area. By doing so, we significantly diminish the reliance on costly, expert-annotated datasets, offering a scalable solution that could transform medical research and practice.

Models like stable diffusion [32], which provides open-source code, alongside DALLE-2 [33], Midjourney, and others, follow in the footsteps of pioneering text-to-image diffusion models, such as GLIDE [34] and Imagen [35]. The growing popularity of these diffusion models [32–36], in contrast to GANs [37–40], is largely due to their robust training dynamics and their ability to produce exceptionally reliable and diverse images.

Leveraging image generation methods presents a promising avenue for addressing the paucity of meticulously curated, high-resolution medical imaging datasets [41]. The annotation process for such datasets requires substantial manual labor from skilled medical professionals, who possess sufficient expertise to decipher and attribute semantically significant features within the images. This innovative approach alleviates the burden on healthcare professionals while ensuring the availability of reliable data.

Here, we utilized DreamBooth [31], which is dependent on the Imagen [35] text-to-image model, and integrated with the stable diffusion framework. DreamBooth offers a notable advantage for fine-tuning models with limited data. Unlike the full stable diffusion framework, DreamBooth requires fewer images to achieve high-quality and context-specific medical image generation. This efficiency stems from its ability to update the entire diffusion model using just a few examples, associating word prompts with the example images. By inputting a minimal set of medical images, we refine a pretrained text-to-image stable diffusion model to uniquely associate specific medical imaging modalities with distinct identifiers. This technique enables the generation of new, photorealistic images for cancer. The resulting high-quality synthetic datasets not only supplement traditional data acquisition methods where real medical images are scarce but also provide valuable resources for advancing machine learning strategies.

Materials and methods

Training the text-to-Image diffusion models using DreamBooth

The experiments were performed using DreamBooth [31] integrated with the Stable Diffusion [32] v1.5 framework. The experiments were conducted using a DreamBooth stable diffusion notebook, available at: (https://colab.research.google.com/github/ShivamShrirao/diffusers/blob/main/examples/dreambooth/DreamBooth_Stable_Diffusion.ipynb). The process involves gradually adding Gaussian noise to an image and then denoising it to generate new images (Fig. 1). Model weights (runwayml/stable-diffusion-v1-5) were obtained from the Huggingface platform [42], which utilizes the Diffusers library [43]. The training configuration employed includes a pre-trained model and a variational autoencoder (VAE) that has been fine-tuned using a mean squared error loss function (stabilityai/sd-vae-ft-mse), provided by Stability AI. It uses prior preservation with a weight of 1.0 and a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. With a training batch size of 1, the text encoder is trained using mixed precision, an 8-bit Adam optimizer, and one gradient accumulation step. The learning rate is set to 10−6, and a constant scheduler is used with no warmup steps. The model utilizes 50 class images, a maximum of 800 training steps, and a save interval of 10 000.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the diffusion model training process

Note: Schematic of the stable diffusion process featuring forward and reverse diffusion [22, 63].

Starting with multiple distinct sets of medical images, we fine-tuned a text-to-image diffusion model that was trained using input images associated with a textual cue, which includes a distinct textual identifier for the class type.

The models were trained using DreamBooth implementation of stable diffusion using distinct sets of medical imaging data. The DreamBooth model consists of a denoising score-matching architecture with normalization layers, a U-Net-based generator, and several residual blocks. The model is designed to perform image synthesis through a diffusion process. The architecture is configured to ensure stable and efficient training. The training process involves a list of concepts, which can be customized.

Diffusion process

The diffusion process is governed by a stochastic differential equation (SDE) that involves a continuous-time Markov process. The SDE is solved using the Euler–Maruyama method with discretization steps (timesteps) ranging from 0 to T − 1. The study explores different noise schedules to understand their impact on the diffusion process.

Inference and image synthesis

The DreamBooth model was used to generate images based on specified prompts. During the image synthesis process, the diffusion process is reversed by iteratively applying the learned denoising function to a sequence of noise-corrupted images. The resulting image is obtained at the end of the reverse process. This procedure is performed with varying noise schedules to analyze the impact on image quality. The main image generation parameters include a positive prompt. The image generation process was performed with a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

Quantitative assessment of image similarity: Fréchet inception distance score analysis

For the quantification of visual similarity between two sets of images, we calculated Fréchet inception distance (FID) scores using a PyTorch implementation (https://github.com/mseitzer/pytorch-fid; Seitzer, 2020). The FID score measures the Wasserstein-2 distance between multivariate Gaussian distributions fitted to the activations of the Inception-v3 pool3 layer of the respective datasets. Images were processed and evaluated using the command “python -m pytorch_fid path/to/dataset1 path/to/dataset2”. This method has been demonstrated to correlate well with human perceptual judgments and is robust for assessing the quality of GAN outputs.

Implementation of StyleGAN3 for generating synthetic MRI and X-ray medical images

The experiments to train StyleGAN3 [44] models on sagittal MRI brain images and chest X-ray images were facilitated through a training notebook (https://github.com/akiyamasho/stylegan3-training-notebook). This process utilized the StyleGAN3 architecture developed by NVIDIA, with the model training being conducted within the integrated Google Colab environment.

Model configuration parameters were set to optimize the training process: Configuration was set to “stylegan3-t”, primarily designed for translation equivariance. GAMMA, the R1 regularization weight, was adjusted to 0.5 to stabilize training dynamics. Training sessions were executed with these parameters. The model’s performance was periodically evaluated by generating checkpoints that allowed for the continuation of training sessions. Post-training, the trained model was used to generate synthetic images.

Results

Training of stable diffusion with DreamBooth for brain cancer

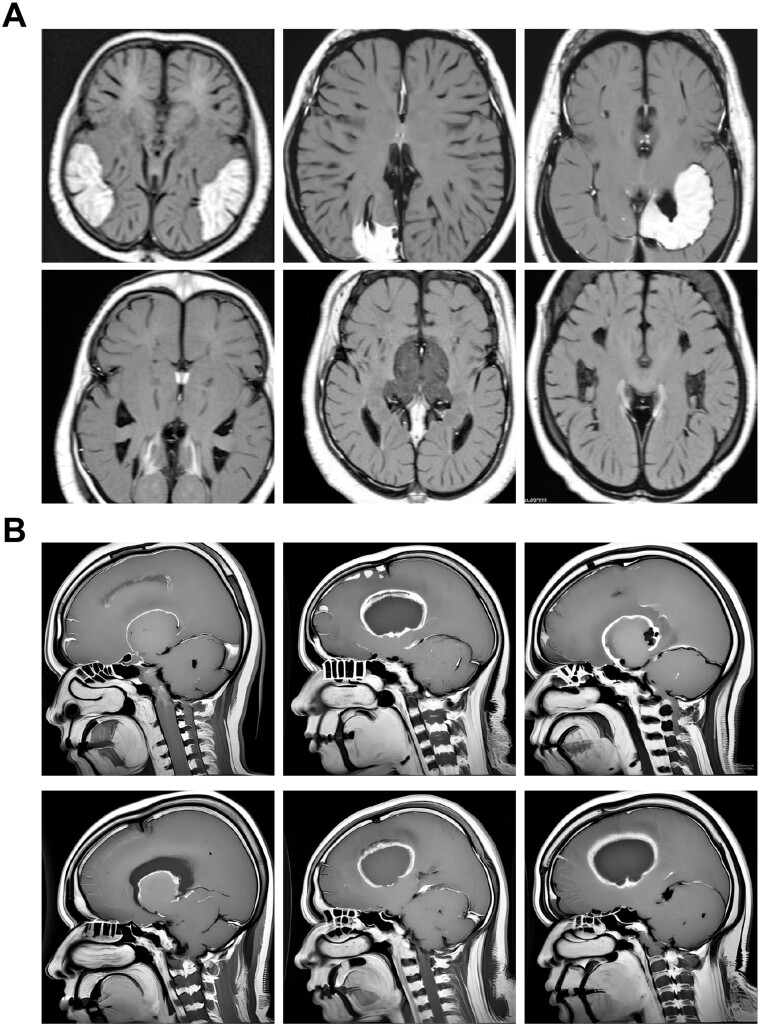

Utilizing the DreamBooth [31] integration within the Stable Diffusion [32] v1.5 framework (see Materials and methods section), we focused on training and synthesizing medical images. We trained separate fine-tuned models on datasets of clinically curated medical images for various brain cancers—specifically gliomas, meningiomas, and pituitary tumors [45, 46], as cataloged in the “Brain Tumor Image Dataset” from Kaggle (see Materials and methods section). After training, the model was used to synthesize MRI images in response to textual prompts. The resulting collection features MRI scans of meningiomas (Fig. 2A), gliomas (Fig. 2B), and pituitary tumors (Fig. 3). Additionally, following training on datasets of healthy brain images, the models produced both sagittal and horizontal MRI scans (Fig. 4), showcasing their ability to accurately replicate complex medical imagery with versatility.

Figure 2.

MRI images of brain cancer generated by fine-tuning a DreamBooth diffusion model

Note: (A) Horizontal MRI scans of synthesized meningioma tumors, displaying z-slices of the brain. (B) Sagittal brain MRI scans of glioma tumors generated using a stable diffusion model fine-tuned with the Kaggle “Brain Tumor Image Dataset”. Images have a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

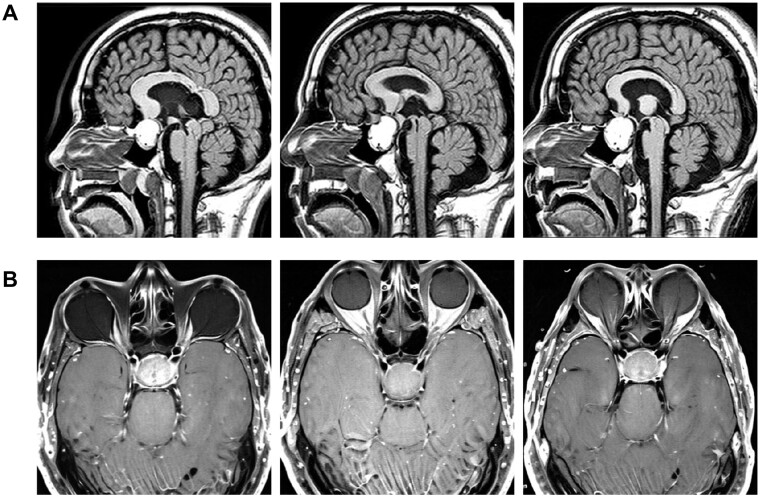

Figure 3.

MRI images depicting pituitary tumor brain scans produced through refining a DreamBooth diffusion model

Note: (A) Sagittal sectional MRI scans displaying pituitary tumors and brain tissue, with each micrograph depicting a slice of the head, brain, and tumor. (B) Horizontal brain MRI scans of pituitary tumors produced using a DreamBooth stable diffusion model refined with the Kaggle “Brain Tumor Image Dataset”. Images are displayed at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

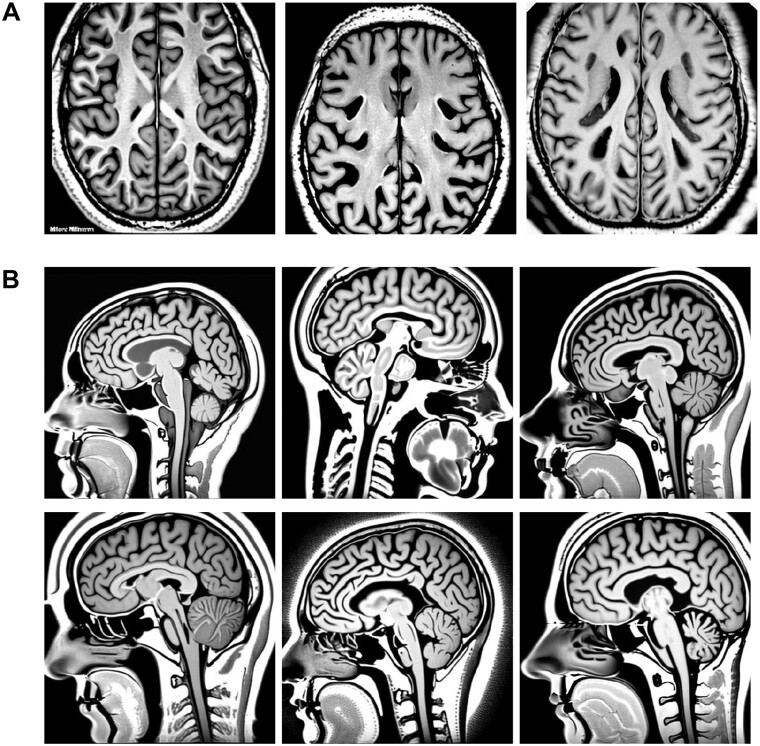

Figure 4.

Examples of images produced for healthy brain MRI scans

Note: (A) Synthesized images of brain MRI scans in horizontal view, showing brain tissue, where each micrograph represents a section of the head and brain. (B) Synthesized MRI scans of healthy brains in sagittal sections. These images were produced using a DreamBooth stable diffusion model and feature a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

Low-grade gliomas (LGGs), classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as grades II and III, are brain neoplasms [47–49] that, unlike the often curable grade I gliomas, exhibit infiltrative growth, increasing their risk of recurrence and progression [50]. Histopathological analysis for these tumors provides imprecise prognostic predictions due to observer variability. An alternative approach involves classifying LGG subtypes through image examination and clinical evaluation, offering critical insights prior to or in lieu of surgical intervention. Studies have linked MRI-derived morphological characteristics with genomic classifications of these tumors [51]. However, traditional manual segmentation of MRI scans [52] for feature extraction is labor intensive and costly, leading to variable annotations.

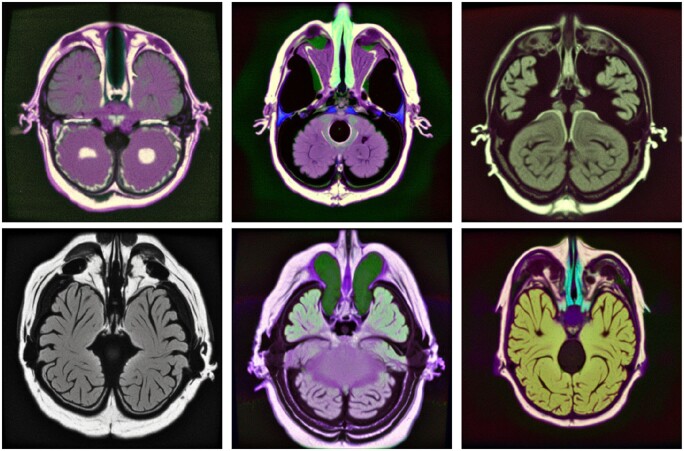

To address these challenges, we have developed LGG diffusion models that can be useful to the scientific community in refining algorithms for categorizing gliomas and other malignancies. Utilizing DreamBooth and medical images from the LGG segmentation dataset [53], we generated stable diffusion models of low-grade gliomas. These models successfully produce a diverse range of MRI images in response to text prompts (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Images generated for low-grade gliomas

Note: Images utilized for fine-tuning a DreamBooth stable diffusion model were sourced from the Cancer Genome Atlas Low Grade Glioma Collection (TCGA-LGG) and the LGG segmentation datasets available on Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mateuszbuda/lgg-mri-segmentation). Training images were acquired from The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) and are associated with patients in TCGA low-grade glioma collection. The resulting synthesized images are displayed at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

Generative models for mammography images

The application of deep learning offers a significant opportunity to reduce the workload of radiologists and enhance diagnostic accuracy. However, achieving these goals requires extensive and comprehensively annotated datasets. A prime example for training deep learning models is the categorized Digital Database for Low energy and Subtracted Contrast Enhanced Spectral Mammography (CDD-CESM) dataset [54], which includes 2006 high-resolution annotated images from CESM, along with medical records of patients aged 18–90.

Using data from the CDD-CESM repository [54], we trained stable diffusion using DreamBooth with a select number of CESM mammography images. We then generated synthesized mammography images using textual prompts (Fig. 6A). Further, our use of image-to-image diffusion techniques created a varied collection of breast cancer mammography images, effectively minimizing patient-specific traits while producing breast tumor images (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Synthesis of CESM images

Note: (A) Training images were obtained from the CDD-CESM [54] database. The fine-tuned model produced synthetic mammography images. (B) Text-to-image synthesis of mammography images using stable diffusion enabled the generation of diverse mammography images for breast cancer detection. Images are presented at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels.

The fine-tuning of these stable diffusion models and image-to-image algorithms has enabled the generation of images with distinct clinical features, making them suitable for various applications including medical education, machine learning, and accessing images of rare conditions. Additionally, these images can be employed in diagnostic assistance, therapeutic planning, patient education, and the development of novel imaging technologies.

Synthesis of chest X-ray images using diffusion models

The thoracic radiograph is a critical diagnostic tool used for detecting and assessing a variety of pulmonary disorders, including pneumonia [55], lung cancer [56], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [57], interstitial lung diseases [58], and pulmonary embolism [59, 60]. In healthcare facilities, X-ray images, along with their corresponding radiology evaluations, are generated and stored.

We leveraged a thoracic radiograph repository to develop a fine-tuned generative diffusion model, using images from the ChestX-ray8 [61] database, which includes 108 948 anterior perspective X-ray images of 32 717 unique individuals. We then used textual prompts to produce synthesized thoracic radiographs (Fig. 7A). The images produced by this model display detailed visuals of chest X-rays, demonstrating its efficacy in creating pulmonary and chest radiographic representations.

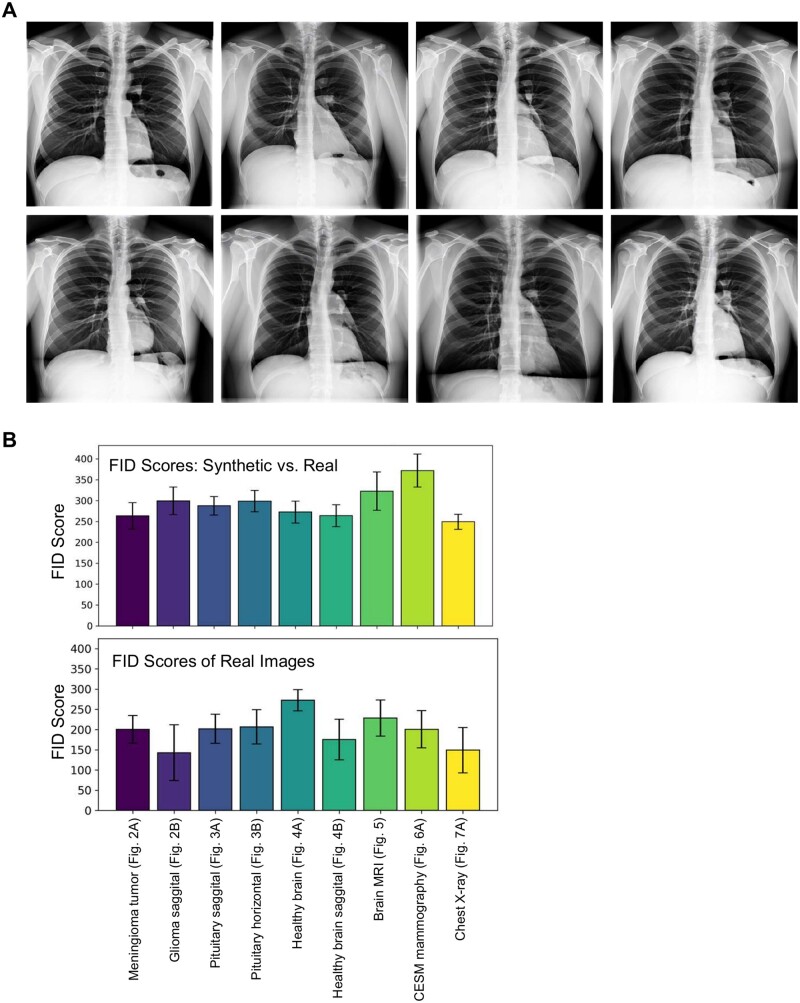

Figure 7.

Chest X-ray images synthesized using a fine-tuned diffusion model

Note: (A) Synthesis of chest X-ray images through the application of DreamBooth stable diffusion for text-to-image transformation, which was used for model fine-tuning. A retrained or fine-tuned DreamBooth model denoises from a random Gaussian noise vector, conditioned by embeddings generated from text prompts. The decoder within the models VAE maps the noise-reduced latent vector to pixel space, yielding high-quality, diverse chest X-rays. (B) Bar plots displaying FID scores: the top section compares synthetic images generated using DreamBooth with real images, and the bottom section compares real images against each other.

Similarity evaluation of authentic and synthesized medical images

We calculated the FID to evaluate the similarity between real medical images and those synthesized using our DreamBooth fine-tuned stable diffusion model. FID, which measures the similarity between two image datasets, correlates strongly with human visual quality assessments and is commonly used to evaluate GANs. The FID score is obtained by computing the Fréchet distance between two Gaussians fitted to feature representations from the Inception network. We used Pytorch-fid [62] to calculate FID scores (see Materials and methods section), comparing both real and synthesized images. Additionally, we assessed FID scores by comparing real images against each other. Our findings reveal a high degree of similarity between real images (MRI, LGG, CDD-CESM, and X-ray) and their synthesized equivalents (Fig. 7B). This demonstrates the effectiveness of the DreamBooth training process.

We conducted a comparative analysis of DreamBooth's integration with Stable Diffusion and StyleGAN to assess their effectiveness in training and image synthesis. Utilizing the StyleGAN3 training notebook (see Materials and methods section), we trained custom datasets for chest X-rays and sagittal MRI of normal brains, as depicted in Figs 7A and 4B, respectively. DreamBooth completed its training in 10–15 minutes on a T4 GPU, while StyleGAN3 required more extensive GPU VRAM resources (A100 or L4) and took 24–36 hours. Given its higher costs and resource demands, StyleGAN's accessibility for researchers is limited. Training was terminated once FID scores neared those of DreamBooth, with both methods showing comparable similarity to real images (FID scores around 200–300).

Notably, DreamBooth achieved lower FID scores than StyleGAN (Supplementary Fig. S1). Furthermore, the training of sagittal MRI images of normal brains using either DreamBooth or StyleGAN yielded synthesized images that closely resembled real images, as shown by FID score analysis (Fig. 7B). These results underscore DreamBooth's superior training efficiency and its ability to generate images of comparable or enhanced quality relative to StyleGAN.

Discussion

By leveraging DreamBooth and a diverse set of medical imagery, we have advanced diffusion models capable of generating high-quality medical images. The application of stable diffusion in medical imaging holds promise for significant advancements in diagnostics, research, and treatment development. Synthesizing detailed medical images enhances diagnostic accuracy, enabling healthcare professionals to precisely identify and assess various medical conditions. Furthermore, creating these images may aid researchers in the development of algorithms and machine learning models that improve diagnostic and treatment methodologies.

The potential of DreamBooth stable diffusion models for MRI, mammography, and X-ray image synthesis has been showcased in this study. Synthesized mammography images offer a valuable dataset for studying a wide range of breast cancer cases, including rare conditions, enhancing accessibility beyond clinical settings. Utilizing synthesized chest images for lung and pulmonary diseases also offers a range of benefits. These images can enhance training data for machine learning algorithms, leading to improved diagnostic capabilities while preserving patient privacy. Moreover, generating synthetic images is cost-effective, as it reduces the need for expensive medical imaging equipment and reliance on limited real-world data. Synthesized images also serve as valuable educational tools, helping medical students and professionals better understand and identify various diseases. Customized datasets can be created with specific disease characteristics, promoting the development and testing of innovative diagnostic methods and treatment approaches. The use of synthesized images ensures ethical research practices by eliminating the need for invasive procedures on real patients, and carefully curated synthetic datasets can avoid biases, providing a more balanced and accurate evaluation of diagnostic algorithms and techniques.

By leveraging these synthesized images, machine learning algorithms can be trained and fine-tuned, ultimately contributing to a reduced burden on radiologists. Furthermore, these images can serve as a basis for the creation of innovative diagnostic techniques, broadening the scope of medical imaging and enhancing patient care. This information may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of cancer diagnosis and treatment, ultimately resulting in improved patient outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the application of diffusion models in generating medical imaging data has the potential to significantly impact the field of medical image research by expanding training datasets and facilitating large-scale investigations. This novel approach offers the opportunity to create diverse and clinically relevant images without compromising patient privacy, thus enabling researchers to develop more accurate diagnostic tools, enhance medical education, and promote the advancement of innovative imaging technologies. The ongoing exploration and refinement of diffusion models will be useful in shaping the future of medical imaging research, ensuring both improved patient outcomes and the ethical use of imaging data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhizhong Han, Yang Shi, and Seongho Kim for helpful discussions. This work utilized the Wayne State University High Performance Computing Grid for computational resources (https://www.grid.wayne.edu/). This work was supported by Wayne State University and Karmanos Cancer Institute.

Author contributions

B.L.K. conceived the study, designed and carried out the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. Benjamin Kidder (Conceptualization [lead], Investigation [lead], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review and editing [lead]).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Biology Methods and Protocols online.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by Wayne State University and Karmanos Cancer Institute.

Data availability

Publicly available medical imaging data analyzed in this study include:

Brain MRI images—Kaggle Brain Tumor Image Dataset [45, 46]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/denizkavi1/brain-tumor; https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mateuszbuda/lgg-mri-segmentation; https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=5309188

Low-grade glioma (LGG) images, Low-grade glioma (LGG) Segmentation Dataset [53]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/denizkavi1/brain-tumor; Mammography images—CDD-CESM repository [54]: https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=109379611; NIH Chest X-rays, ChestX-ray8 database [61]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nih-chest-xrays/data; Stable diffusion weights—The DreamBooth stable diffusion weights, instance prompts, and code for image inference and training have been deposited on Hugging Face: https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_normal_horizontal_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_normal_saggital_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_pituitary_tumor_horizontal_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_pituitary_tumor_saggital; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Chest_X-ray; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Glioma_saggital_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/low_grade_glioma_lgg_horizontal; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Mammography_CESM; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/meningioma_tumor; Code: The corresponding code is publicly available at: https://github.com/KidderLab/Medical_Imaging

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kazerouni A, Aghdam EK, Heidari M. et al. Diffusion models in medical imaging: a comprehensive survey. Med Image Anal 2023;88:102846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barragán-Montero A, Javaid U, Valdés G. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for medical imaging: a technology review. Phys Med 2021;83:242–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suganyadevi S, Seethalakshmi V, Balasamy K.. A review on deep learning in medical image analysis. Int J Multimed Inf Retr 2022;11:19–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han Z, Wei B, Mercado A. et al. Spine-GAN: semantic segmentation of multiple spinal structures. Med Image Anal 2018;50:23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serag A, Ion-Margineanu A, Qureshi H. et al. Translational AI and deep learning in diagnostic pathology. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barile B, Marzullo A, Stamile C. et al. Data augmentation using generative adversarial neural networks on brain structural connectivity in multiple sclerosis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2021;206:106113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tellez D, Litjens G, van der Laak J. et al. Neural image compression for gigapixel histopathology image analysis. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2019;43:567–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bera K, Schalper KA, Rimm DL. et al. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—new tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:703–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huo Y, Deng R, Liu Q. et al. AI applications in renal pathology. Kidney Int 2021;99:1309–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mandal S, Greenblatt AB, An J.. Imaging intelligence: AI is transforming medical imaging across the imaging spectrum. IEEE Pulse 2018;9:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xing F, Xie Y, Su H. et al. Deep learning in microscopy image analysis: A survey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learning Syst 2018;29:4550–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sultan AS, Elgharib MA, Tavares T. et al. The use of artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in oncologic histopathology. J Oral Pathol Med 2020;49:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anwar SM, Majid M, Qayyum A. et al. Medical image analysis using convolutional neural networks: a review. J Med Syst 2018;42:226–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta A, Harrison PJ, Wieslander H. et al. Deep learning in image cytometry: a review. Cytometry A 2019;95:366–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Müller-Franzes G, Niehues J, Khader F. et al. Diffusion Probabilistic Models beat GANs on Medical Images. arXiv 2022. arXiv preprint arXiv:221207501.

- 16. Dhariwal P, Nichol A.. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021;34:8780–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schuhmann C, Beaumont R, Vencu R. et al. LAION-5B: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models. arXiv:2210.08402 [cs.CV], 2022.

- 18. Dorjsembe Z, Odonchimed S, Xiao F. Three-dimensional medical image synthesis with denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In: Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, 2022

- 19. Yi X, Walia E, Babyn P.. Generative adversarial network in medical imaging: A review. Med Image Anal 2019;58:101552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kazerouni A, Aghdam E, Heidari M. et al. Diffusion models for medical image analysis: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2210.08402 [cs.CV], 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Cao H, Tan C, Gao Z. et al. A survey on generative diffusion model. arXiv:2209.02646 [cs.AI], 2022.

- 22. Ali H, Murad S, Shah Z. Spot the fake lungs: Generating Synthetic Medical Images using Neural Diffusion Models. arXiv:2211.00902 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 23. Chambon P, Bluethgen C, Delbrouck J. et al. RoentGen: vision-language foundation model for chest X-ray generation. arXiv:2211.12737 [cs.CV], 2022.

- 24. Chambon P, Bluethgen C, Langlotz CP. et al. Adapting pretrained vision-language foundational models to medical imaging domains. arXiv:2210.04133 [cs.CV], 2022.

- 25. Müller-Franzes G, Niehues J, Khader F. et al. Diffusion probabilistic models beat GANs on medical images. arXiv:2212.07501 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 26. Khader F, Mueller-Franzes G, Arasteh S. et al. Medical diffusion: denoising diffusion probabilistic models for 3D medical image generation. arXiv:2211.03364 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 27. Kim B, Ye JC. Diffusion deformable model for 4D temporal medical image generation. arXiv:2206.13295 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 28. Packhäuser K, Folle L, Thamm F. et al. Generation of anonymous chest radiographs using latent diffusion models for training thoracic abnormality classification systems. arXiv:2211.01323 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 29. Peng W, Adeli E, Zhao Q. et al. Generating realistic 3D brain MRIs using a conditional diffusion probabilistic model. arXiv:2212.08034 [eess.IV], 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Pinaya WHL, Tudosiu P, Dafflon J. et al. Brain imaging generation with latent diffusion models. arXiv:2209.07162 [eess.IV], 2022.

- 31. Ruiz N, Li Y, Jampani V. et al. Fine tuning text-to-image diffusion models for subject-driven generation. arXiv:2208.12242 [cs.CV], 2022.

- 32. Rombach R, Blattmann A, Lorenz D. et al. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)2021:10674–85. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramesh A, Dhariwal P, Nichol A. et al. Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv:2204.06125 [cs.CV], 2022.

- 34. Nichol A, Dhariwal P, Ramesh A. et al. Glide: Towards photorealistic image generation and editing with text-guided diffusion models. arXiv:2112.10741 [cs.CV], 2021.

- 35. Saharia C, Chan W, Saxena S. et al. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022;35:36479–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sohl-Dickstein J, Weiss E, Maheswaranathan N. et al. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. arXiv 2015;abs/1503.03585.

- 37. Reed S, Akata Z, Yan X. et al. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research2016;1060–9.

- 38. Zhang H et al. Stackgan: Text to photo-realistic image synthesis with stacked generative adversarial networks. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 2017;5908–16.

- 39. Xu T, Zhang P, Huang Q. et al. Attngan: Fine-grained text to image generation with attentional generative adversarial networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition2018;1316–24.

- 40. Li B, Qi X, Lukasiewicz T. et al. Controllable text-to-image generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019;32. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koh D-M, Papanikolaou N, Bick U. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in cancer imaging. Commun Med (Lond) 2022;2:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V. et al. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations 2020;38–45.

- 43. von Platen P, Patil S, Lozhkov A. et al. Diffusers: state-of-the-art diffusion models. GitHub repository. 2022.

- 44. Karras T, Aittala M, Laine S. et al. Alias-free generative adversarial networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021;34:852–63. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cheng J, Huang W, Cao S. et al. Enhanced performance of brain tumor classification via tumor region augmentation and partition. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng J, Yang W, Huang M. et al. Retrieval of brain tumors by adaptive spatial pooling and fisher vector representation. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Forst DA, Nahed BV, Loeffler JS. et al. Low-grade gliomas. Oncologist 2014;19:403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sanai N, Chang S, Berger MS.. Low-grade gliomas in adults: a review. J Neurosurg 2011;115:948–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cavaliere R, Lopes MBS, Schiff D.. Low-grade gliomas: an update on pathology and therapy. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:760–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wank M, Schilling D, Schmid TE. et al. Human glioma migration and infiltration properties as a target for personalized radiation medicine. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10(11):456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mazurowski MA, Clark K, Czarnek NM. et al. Radiogenomics of lower-grade glioma: algorithmically-assessed tumor shape is associated with tumor genomic subtypes and patient outcomes in a multi-institutional study with The Cancer Genome Atlas data. J Neurooncol 2017;133:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Menze BH, Jakab A, Bauer S. et al. The multimodal brain tumor image segmentation benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2015;34:1993–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Buda M, Saha A, Mazurowski MA.. Association of genomic subtypes of lower-grade gliomas with shape features automatically extracted by a deep learning algorithm. Comput Biol Med 2019;109:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Khaled R, Helal M, Alfarghaly O. et al. Categorized contrast enhanced mammography dataset for diagnostic and artificial intelligence research. Sci Data 2022;9:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Khatri A, Jain R, Vashista H. et al. Pneumonia identification in chest X-ray images using EMD. In: Trends in Communication, Cloud, and Big Data: Proceedings of 3rd National Conference on CCB, 2018. Springer (2020).

- 56. van Ginneken B. Fifty years of computer analysis in chest imaging: rule-based, machine learning, deep learning. Radiol Phys Technol 2017;10:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bhatt SP, Washko GR, Hoffman EA. et al. Imaging advances in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Insights from the genetic epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPDGene) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;199:286–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ward J, McDonald C.. Interstitial lung disease: An approach to diagnosis and management. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:106–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ho M-L, Gutierrez FR.. Chest radiography in thoracic polytrauma. Ajr Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gadkowski LB, Stout JE.. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008;21:305–33, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang X, Peng Y, Lu L. et al. ChestX-Ray8: Hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE Computer Society (2017).

- 62. Seitzer M. pytorch-fid: FID Score for PyTorch. GitHub repository. 2020.

- 63. Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P.. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020;33:6840–51. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available medical imaging data analyzed in this study include:

Brain MRI images—Kaggle Brain Tumor Image Dataset [45, 46]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/denizkavi1/brain-tumor; https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mateuszbuda/lgg-mri-segmentation; https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=5309188

Low-grade glioma (LGG) images, Low-grade glioma (LGG) Segmentation Dataset [53]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/denizkavi1/brain-tumor; Mammography images—CDD-CESM repository [54]: https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=109379611; NIH Chest X-rays, ChestX-ray8 database [61]: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nih-chest-xrays/data; Stable diffusion weights—The DreamBooth stable diffusion weights, instance prompts, and code for image inference and training have been deposited on Hugging Face: https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_normal_horizontal_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_normal_saggital_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_pituitary_tumor_horizontal_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Brain_pituitary_tumor_saggital; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Chest_X-ray; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Glioma_saggital_MRI; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/low_grade_glioma_lgg_horizontal; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/Mammography_CESM; https://huggingface.co/KidderLab/meningioma_tumor; Code: The corresponding code is publicly available at: https://github.com/KidderLab/Medical_Imaging