Abstract

Background and study aims Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is sometimes challenging because of stenosis and scarring. We examined the use of an ultrathin endoscope for esophageal ESD, which is difficult using conventional endoscopes.

Patients and methods A designated transparent hood and ESD knife for ultrathin endoscopes have been developed and clinically introduced. Esophageal ESD was performed on 303 lesions in 220 patients in our hospital from February 2021 to February 2023. Of them, an ultrathin endoscope was used on 26 lesions in 23 cases. The safety and utility of an ultrathin endoscope in esophageal ESD were retrospectively verified.

Results All 26 lesions were resected en bloc, and serious complications such as perforation, massive bleeding, or pneumonia, were not observed. Lesions were found on the anal side of the stenosis and over the scarring in 38.6% (10/26) and 50% (13/26) of participants, respectively. Moreover, 46.2% of participants (12/26) had lesions on the cervical esophagus. The total procedure time was 64.1 ± 37.7 minutes, but the average time from oral incision to pocket creation was 121.2 ± 109.9 seconds.

Conclusions Ultrathin endoscopes may be useful for difficult esophageal ESD.

Keywords: Endoscopy Upper GI Tract; Endoscopic resection (ESD, EMRc, ...); Pediatric endoscopy; Benign strictures

Introduction

Endoscopic treatment is widely used for superficial esophageal cancer. Endoscopic treatment progressed from endoscopic mucosal resection to endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), drastically improving the en bloc resection rate 1 2 . Intramucosal carcinoma, which has a low risk of lymph node metastasis, can be cured via endoscopic resection of the lesion, enabling treatment while maintaining the patient’s quality of life. Stenosis, scarring, or lesions in the cervical esophagus are the major difficulties in esophageal ESD, among various difficulties that have been reported 3 4 5 .

Owing to their minimal invasiveness, ultrathin endoscopes are primarily used for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy 6 . The image resolution is improved, and the lesion detection rate is comparable to conventional endoscopy 7 . Nevertheless, ultrathin endoscopes have not been used in therapeutic endoscopy because dedicated treatment devices are unavailable 8 9 . However, ultrathin endoscopes have an advantage in therapeutic endoscopy as they can access narrow areas. This device is particularly advantageous in esophageal ESD, where a narrow visual field is associated with treatment difficulty due to stenosis or scarring. We collaborated with companies to develop two ultrathin endoscope devices to enable ESD and used them in clinical practice 10 11 . This study retrospectively investigated the usefulness of ultrathin endoscopes in esophageal ESD.

Patients and methods

We performed esophageal ESD on 220 patients with 303 lesions in Toranomon Hospital from February 2021 to February 2023. In these cases, ESD with a conventional endoscope was difficult. Ultrathin endoscopes were used for ESD in 26 lesions in 23 patients. An ultrathin endoscope was used when a conventional endoscope could not visualize the lesion or the site of dissection. Therefore, an ultrathin endoscope was used because starting with a conventional endoscope approach was impossible due to stenosis or curvature of the cervical esophagus.

When an adequate approach to the dissection area is impossible because of a condition such as scarring, treatment is usually performed with a conventional endoscope followed by an ultrathin endoscope. This study retrospectively investigated the safety and efficacy of ultrathin endoscopes in esophageal ESD. The Ethics Committee of Toranomon Hospital approved this study.

Device

ESD procedure using an ultrathin endoscope on a lesion with a pharyngeal stricture.

Video 1

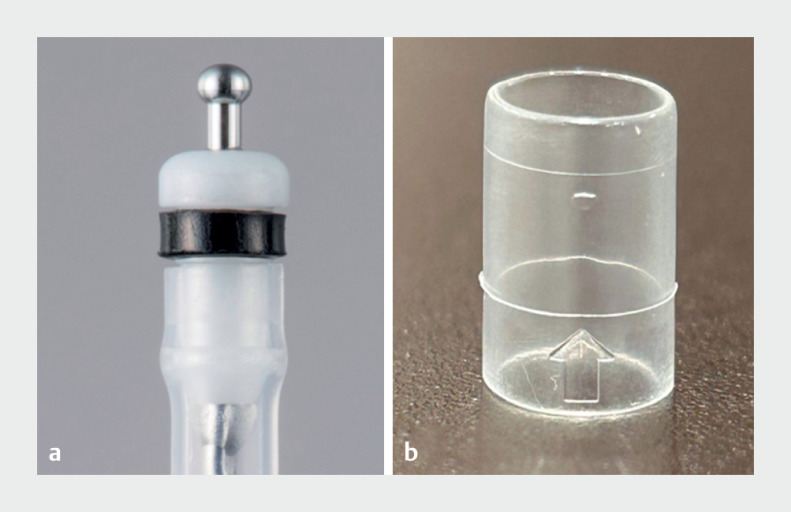

A transparent hood (Nichendo) for ultrathin endoscopes was jointly developed with Yasui Co., Ltd. (Miyazaki, Japan), and an ESD knife (Endosaber Fine) for ultrathin endoscopes was jointly developed with Yamashina Seiki Co., Ltd. (Shiga, Japan).

The cylindrical transparent hood has an outer diameter of 5.9 mm and is made of elastomer. The maximum outer diameter of the ESD knife was 1.95 mm. These devices were approved and clinically introduced in January 2021.

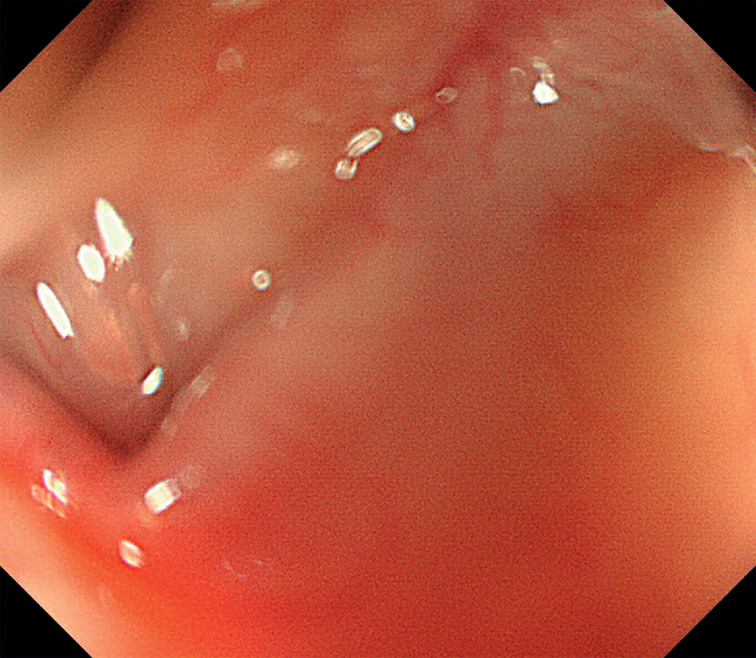

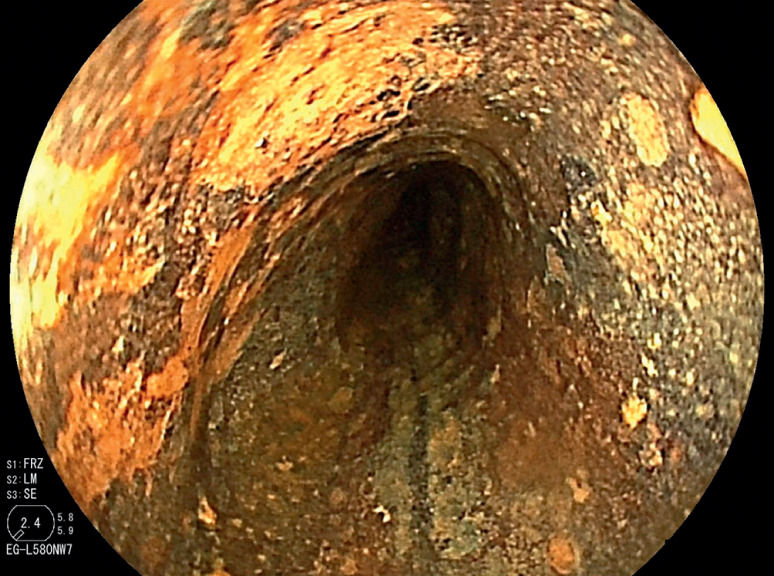

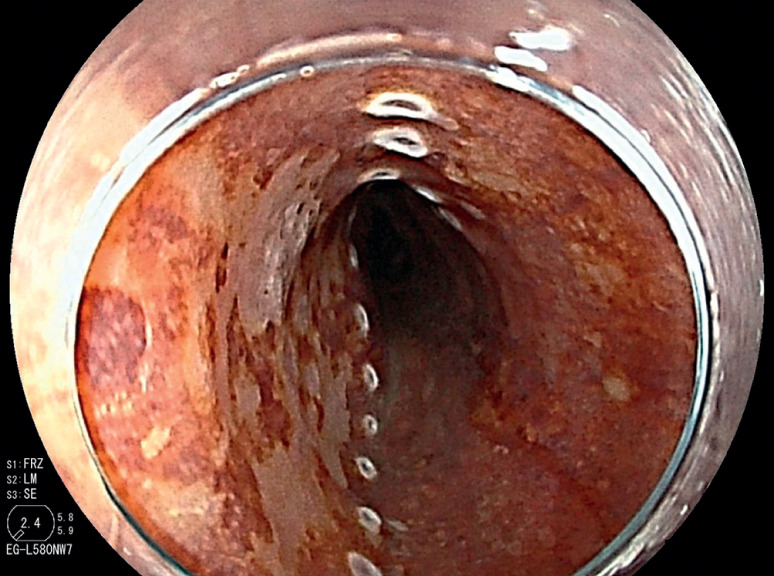

Conventional endoscopes include an Olympus GIF H290T (maximum diameter 11.8 mm) or a Fujifilm EG-L580RD7 (maximum diameter 11.8 mm). Ultrathin endoscopes include an Olympus GIF 1200N (maximum diameter 5.8 mm), an Olympus GIF 290N (maximum diameter 5.8 mm), or a Fujifilm EG-L580NW7 (maximum diameter 5.9 mm). ESD was performed beyond the stricture after pharyngeal chemoradiotherapy ( Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 , and Video 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Images of devices that have been developed and clinically introduced. a Transparent hood for ultrathin endoscope (Nichendo). b Endoscopic submucosal dissection knife for ultrathin endoscope (Endosaber Fine).

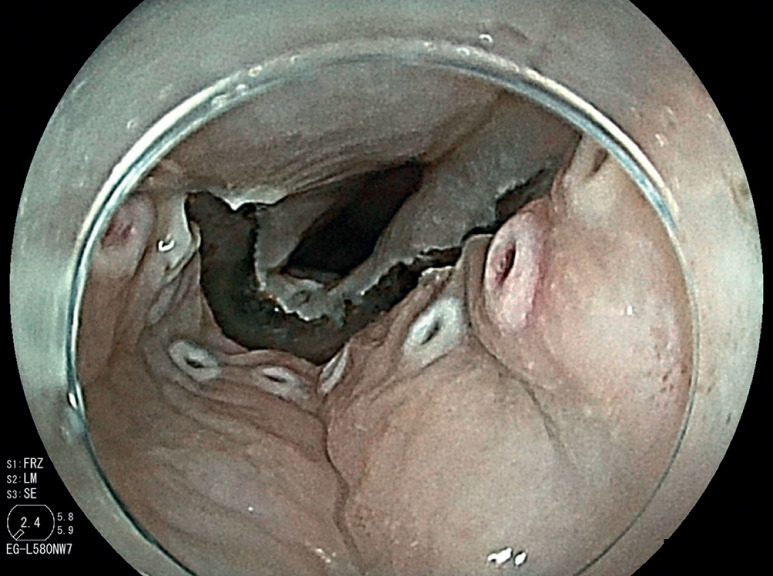

Fig. 2.

A conventional endoscope could not pass through the stenosis after CRT.

Skilled endoscopists with board certification from the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society performed all ESD procedures in this study. Furthermore, the method of esophageal ESD was similar to the conventional method and is described briefly. First, iodine staining was used to diagnose the border ( Fig. 3 ). Then, markings were placed approximately 2 mm outside the lesions with a soft coagulation effect 4, 50 W with a knife tip ( Fig. 4 ). Glycerol was injected outside the marking, and an incision was made with an endocut effect of 1, duration of 1, and interval of 1 ( Fig. 5 ). Afterward, dissection was performed with swift coagulation effect 3, 40 W while observing the submucosal layer to be dissected with a transparent tip hood ( Fig. 6 ), and the lesion was resected en bloc ( Fig. 7 , Fig. 8 ). Intraoperative hemorrhage was coagulated with a knife tip with swift coagulation effect 3, 40 W. Hemostatic forceps were used (Pentax or Kaneka) with soft coagulation effect 4, 50 W when hemostasis could not be obtained. This study used a VIO 300D high-frequency apparatus (ERBE, Tübingen, Germany).

Fig. 3.

A lesion was identified as an iodine-unstained area.

Fig. 4.

A marking was placed 2 mm outside the lesion.

Fig. 5.

An anal side incision was performed.

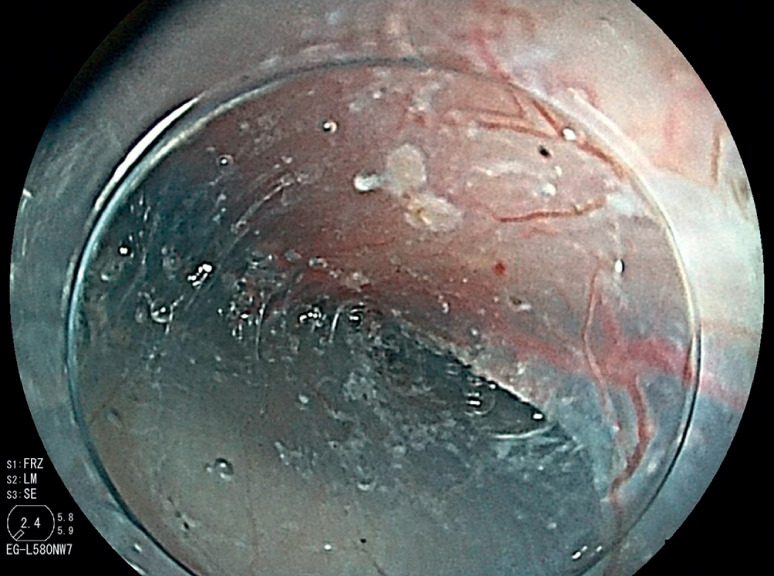

Fig. 6.

The submucosal layer was dissected using the pocket creation method.

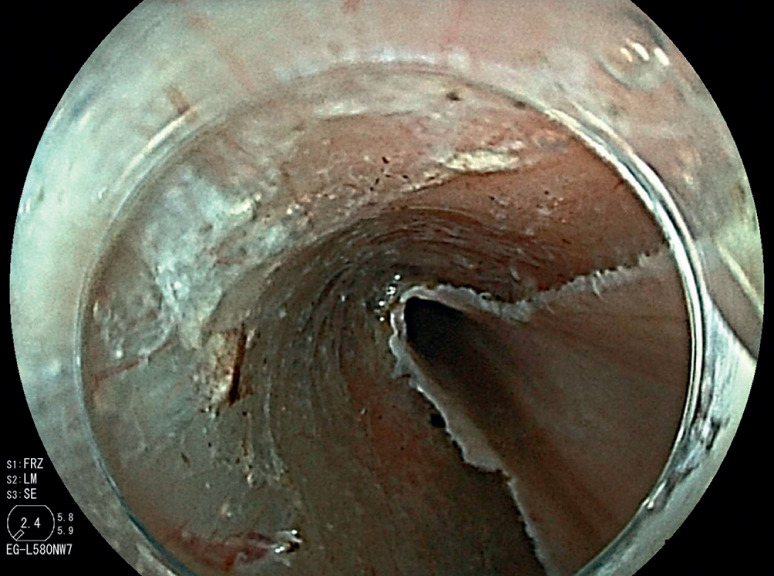

Fig. 7.

The lesion was resected en bloc.

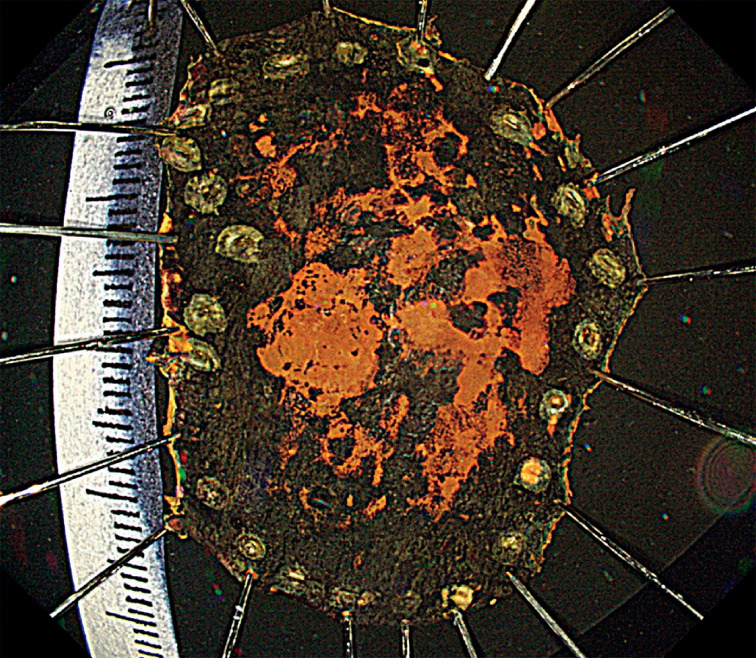

Fig. 8.

The pathological diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma, pT1a-LPM, 25 × 18 mm, ly0, v0, margin negative.

ESD was initiated with an ultrathin endoscope for lesions on the anal side of the stenosis or the cervical esophagus when a lesion could not be approached with a conventional endoscope. Furthermore, ESD with a conventional endoscope was combined with an ultrathin endoscope when the dissected layer could not be visualized due to fibrosis during dissection.

A local injection or an oral steroid was administered at operator discretion to prevent postoperative stenosis. Fluid replacement was performed while the patient was fasting on the day of ESD. Examination, x-ray, and blood testing were performed the day after ESD and meals were started at operator discretion.

Evaluation items

Short-term outcomes evaluated included intraoperative perforation, muscle layer injury, procedure time, intraoperative bleeding, postoperative bleeding, pneumonia, and fever. Outcomes such as postoperative stenosis and recurrence were evaluated as long-term factors. The procedure time required from the start of the oral side incision to pocket creation in cases using the pocket creation method was measured by analyzing video images.

Results

This study included 23 patients (19 males and four females, Table 1 ). Ultrathin endoscopes were used in 8.6% (26/303) of all esophageal ESD procedures during the same period. The average age of the patients was 72.8 ± 8.0 years. Eight of the 26 ESD procedures were completed with an ultrathin endoscope and 18 with an ultrathin and a conventional endoscope. In nine of those 18 cases, ultrathin endoscopes were used first due to the stenosis, and then conventional endoscopes were used in combination with an ultrathin endoscope. In the remaining nine cases, conventional endoscopes were used first, and then ultrathin endoscopes were used due to scarring. ESD procedures were performed under general anesthesia in 18 cases and under conscious sedation with sedatives and analgesics in eight.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

| SD, standard deviation. | |

| Number of patients | 23 cases |

| Age, years (± SD) | 72.8 ± 8.0 |

| Gender (male:female) | 19:4 |

| History of pharyngeal cancer, % (n/n) | 56.5 (13/23) |

| History of esophageal cancer, % (n/n) | 90.0 (21/23) |

Lesions were found on the anal side of the stenosis in 38.6% (10/26) and with scarring in 50% (13/26). Furthermore, 46.2% of patients (12/26) had lesions in the cervical esophagus ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Lesion characteristics.

| SD, standard deviation. | |

| Number of lesions | 26 |

| Tumor size (mm ± SD) | 18.8 ± 14.1 |

| Specimen size (mm ± SD) | 32.6 ± 13.2 |

| Lesions on the anal side of the stenosis, % (n/n) | 38.6 (10/26) |

| Lesions with scarring, % (n/n) | 50 (13/26) |

| Lesions on the cervical esophagus, % (n/n) | 46.2 (12/26) |

En bloc resection was possible for all 26 lesions. Serious complications, such as intraoperative perforation, pneumonia, and intraoperative bleeding, were not observed. Muscle layer damage was observed in seven lesions, but all could be followed up conservatively. Stenosis was prevented with corticosteroids in three cases. These patients only had mild stenosis and balloon dilatation was not required. Balloon dilatation was required in one patient with stenosis in whom steroids were not used.

The average size of the specimens was 32.6 ± 13.2 mm and the invasion depth was T1a-MM in one lesion; all others were T1a-epithelial or lamina propria. Five lesions had positive or ambiguous lateral margins and all had negative vertical margins. Total procedure time was 64.1 ± 37.7 minutes. The pocket creation method was used in 53.8% of cases (14/26). The average time required from the start of oral incision to pocket creation was 121.2 ± 109.9 seconds ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Study results.

| ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; SD, standard deviation. | |

| En bloc resection rate, % (n/n) | 100 (26/26) |

| R0 resection rate, % (n/n) | 80.8 (21/26) |

| Procedure time (min ± SD) | 62.2 ± 36.7 |

| Perforation, % (n/n) | 0 (0/26) |

| Muscle injury, % (n/n) | 26.9 (7/26) |

| Massive bleeding, % (n/n) | 0 (0/23) |

| Delayed bleeding, % (n/n) | 0 (0/23) |

| Pneumonia, % (n/n) | 0 (0/23) |

| Stenosis after ESD, % (n/n) | 4.3 (1/23) |

Discussion

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has been identified as cancer with a high metachronous carcinogenesis rate. The incidence of metachronous carcinogenesis 5 years after ESD for pharyngeal and esophageal SCC is approximately 20% 12 13 . Careful endoscopic follow-up is important, but patient prognosis is excellent if the disease is detected early. We usually perform follow-up endoscopys twice a year in patients with a history of SCC. All of the patients in this study had a history of pharyngeal or esophageal SCC that was discovered during follow-up endoscopy.

Esophageal stenosis and narrowing of the lumen occasionally is seen in patients and the causes are various. Stenosis is a major clinical problem, especially after extensive ESD, and various methods to prevent stenosis have been reported 14 15 16 17 18 . Among them, steroids are currently the most widely used. Nevertheless, we have often seen patients for whom balloon dilatation was required. Stenosis also can occur after radiation therapy for esophageal and pharyngeal cancer. Radiation-induced stenosis is more severe than post-ESD stenosis, and dilation may not resolve the stenosis.

Esophageal ESD can be complicated by various factors, one of which is stenosis, which is the major factor impacting procedure success. Furthermore, lesions from post-ESD scarring and cervical esophageal lesions are sometimes difficult to treat with normal ESD. All of our patients had at least one of these complications. An ultrathin endoscope may not be necessary when balloon dilatation is performed, and treatment with a conventional endoscope is possible. However, the lesion will be damaged if balloon dilation is performed on the anal side of the stenosis with a normal diameter device. An ultrathin endoscope has great advantages if a conventional endoscope cannot pass through the balloon dilation because of severe stenosis.

Moreover, dissecting the scar under direct vision using a conventional endoscope is sometimes difficult. Even in such a case, an ultrathin endoscope can be used in a narrow space in the scar to perform dissection under direct vision. Furthermore, lesions in the cervical esophagus are sometimes difficult to approach using a conventional endoscope. An ultrathin endoscope approach is possible in such cases. Subsequent treatment is relatively easy if the submucosal space can be entered using an ultrathin endoscope using the pocket creation method 19 . Approximately half of the patients in this study underwent ESD of the cervical esophagus. Ultrathin endoscopes are useful for ESD in the narrow and curved cervical esophagus.

This study has some limitations, as does ESD with an ultrathin endoscope. First, this study was not a comparison study with a conventional endoscope. ESD with conventional endoscopes was performed as much as possible and ultrathin endoscopes were used only when treatment with conventional endoscopes was challenging. In the future, we will further clarify the criteria for using ultrathin endoscopes and conduct randomized controlled trials to verify the usefulness of ultrathin endoscopes. An ultrathin endoscope is more unstable than a conventional endoscope because of its thinness and softness. However, the pocket creation method was used as much as possible because the endoscope provides stability when entering the narrow submucosal space. A pocket can be created quickly using an ultrathin endoscope, which is considered a great advantage.

Furthermore, an ultrathin endoscope in an ESD procedure is difficult to aspirate and waterjets cannot be used. ESD using an ultrathin endoscope is more difficult than with a conventional endoscope. Massive bleeding during an ESD procedure can be a difficult complicatoin. Hence, we attempted to perform ESD with a conventional endoscope as much as possible. Operators who perform ESD with an ultrathin endoscope mst have a higher level of skill. Using an ultrathin endoscope does not eliminate all complications. Ultrathin endoscopes are considered suitable for ESD because the procedure causes relatively little bleeding. An ultrathin endoscope with a large forceps diameter and a waterjet function should be developed.

Conclusions

We developed two devices that enable ESD with an ultrathin endoscope and introduced them for clinical use. They were used for esophageal ESD 2 years after their introduction. ESD is usually difficult to perform with a conventional endoscope. The ultrathin endoscope was used for 8.6% of all esophageal ESDs. The procedure took a long time, but en bloc resection was safely performed in all cases. Ultrathin endoscopes may be useful for difficult cases of esophageal ESD.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kim JS, Kim BW, Shin IS. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous esophageal neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1862–1869. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Masao H et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection is superior to conventional endoscopic resection as a curative treatment for early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuhara M, Urabe Y, Oka S et al. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients who develop metachronous superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma close to a post-endoscopic submucosal dissection scar. Esophagus. 2023;20:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10388-022-00945-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ariyoshi R, Toyonaga T, Tanaka S et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms extending to the cervical esophagus. Endoscopy. 2018;50:613–617. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Hoteya S et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial cancer of the cervical esophagus. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E736–E741. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-112493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Takagi Y, Yamamoto K et al. Narrow-band imaging on screening of esophageal lesions using an ultrathin transnasal endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khurelbaatar T, Miura Y, Osawa H et al. Improved detection of early gastric cancer with linked color imaging using an ultrathin endoscope: a video-based analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2022;10:E644–E652. doi: 10.1055/a-1793-9414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura M, Shibata T, Tahara T et al. Usefulness of transnasal endoscopy where endoscopic submucosal dissection is difficult. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:378–384. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono K, Ohata K, Kimoto Y et al. A case of early esophageal cancer with pharyngeal stenosis treated by endoscopic submucosal multi-tunnel dissection using an ultra-thin endoscope. Endoscopy. 2023;55:E1–E2. doi: 10.1055/a-1899-8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikuchi D, Tanaka M, Nakamura S et al. Feasibility of ultrathin endoscope for esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E606–E609. doi: 10.1055/a-1352-3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koseki M, Kikuchi D, Odagiri H et al. Possibility of ultrathin endoscopy in radial incision and cutting for esophageal strictures. VideoGIE GIE. VideoGIE. 2022;7:358–360. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2022.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogasawara N, Kikuchi D, Inoshita N et al. Metachronous carcinogenesis of superficial esophagus squamous cell carcinoma after endoscopic submucosal dissection: incidence and risk stratification during long-term observation. Esophagus. 2021;18:806–816. doi: 10.1007/s10388-021-00848-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogasawara N, Kikuchi D, Tanaka M et al. Comprehensive risk evaluation for metachronous carcinogenesis after endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus. 2022;19:460–468. doi: 10.1007/s10388-022-00907-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi N, Isomoto H, Nakayama T et al. Usefulness of oral prednisolone in the treatment of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanaoka N, Ishihara R, Takeuchi Y et al. Intralesional steroid injection to prevent stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal cancer: a controlled prospective study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1007–1011. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iizuka T, Kikuchi D, Yamada A et al. Polyglycolic acid sheet application to prevent esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2015;47:341–344. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang J, Ye S, Ji X et al. Deployment of carboxymethyl cellulose sheets to prevent esophageal stricture after full circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection: A porcine model. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:608–615. doi: 10.1111/den.13070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohki T, Yamato M, Ota M et al. Prevention of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection using tissue-engineered cell sheets. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:582–58800. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takezawa T, Hayashi Y, Shinozaki S et al. The pocket-creation method facilitates colonic endoscopic submucosal dissection (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]