Abstract

The relationship between lifestyle behaviors and common chronic conditions is well established. Lifestyle medicine (LM) interventions to modify health behaviors can dramatically improve the health of individuals and populations. There is an urgent need to meaningfully integrate LM into medical curricula horizontally across the medical domains and vertically in each year of school and training. Including LM content in medical and health professional curricula and training programs has been challenging. Barriers to LM integration include lack of awareness and prioritization of LM, limited time in the curricula, and too few LM-trained faculty to teach and role model the practice of LM. This limits the ability of health care professionals to provide effective LM and precludes the wide-reaching benefits of LM from being fully realized. Early innovators developed novel tools and resources aligned with current evidence for introducing LM into didactic and experiential learning. This review aimed to examine the educational efforts in each LM pillar for undergraduate and graduate medical education. A PubMed-based literature review was undertaken using the following search terms: lifestyle medicine, education, medical school, residency, and healthcare professionals. We map the LM competencies to the core competency domains of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. We highlight opportunities to train faculty, residents, and students. Moreover, we identify available evidence-based resources. This article serves as a “call to action” to incorporate LM across the spectrum of medical education curricula and training.

Article Highlights.

-

•

Medical and health care professional students and trainees educated in lifestyle medicine have the potential to positively impact patient outcomes.

-

•

Currently, there are minimal instructional hours for the 6 pillars of lifestyle medicine in medical school and residency.

-

•

Established resources and curricula are available to teach lifestyle medicine across the continuum of medical education.

-

•

Innovative opportunities exist to deliver medical education programs, overcome barriers to curricular integration, and research education outcomes in lifestyle medicine.

-

•

Lifestyle medicine knowledge and skills align well with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competency framework, and a focus on competency-based learning is the future of lifestyle medicine educational design.

Frontline health care professionals (HCPs) have the responsibility to address chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, cancer, and obesity with lifestyle medicine (LM) interventions as first-line therapy for the prevention and, in many cases, treatment, aligning with guidelines from the American Heart Association,1 American Cancer Society,2 American Diabetes Association,3 and the American Association of Family Physicians.4 The US health care system is set up to be a reactive “sick care” system for which reimbursement is higher when patients have chronic conditions requiring medications and procedures. Moving the system to one that values health restoration will require incentives for deprescribing and keeping patients out of the hospital and emergency department. This calls for physicians and HCPs who are certified in LM and thus competent at prescribing evidence-based LM interventions. Education and training related to therapeutic LM interventions and mastery of the LM competencies5 can offer dramatic and far-reaching effects. Addressing lifestyle behaviors can improve clinical outcomes and decrease health care costs.6, 7, 8

Although 60% of Americans have 1 or more diet-related chronic conditions,9 only 25%-40% of primary care visits include nutrition counseling.10, 11, 12, 13 Physicians receive little formal nutrition education.14 In addition, 94% of primary care residents feel obligated to discuss nutrition with their patients, yet only 14% feel prepared to do so.15 Since 1985, the National Academy has recommended 25-30 hours of nutrition education in US medical schools.16 Although nearly 85% of medical students recognize that nutrition education is a necessary part of their training,17 71% of medical schools provide less than the recommended minimum of 25 hours nutrition education.18 Physicians report a lack of confidence in their ability, knowledge, and skills to address lifestyle behaviors19, 20, 21, 22 and are, therefore, often unable to support patients in making impactful lifestyle changes.

In addition to nutrition, other lifestyle behaviors are necessary for physical and mental health. For example, it is well-accepted that exercise has several health benefits and is like medicine.23,24 The American Heart Association added sleep to Life’s Simple 7 in 2022 to create the Essential 8 framework highlighting vital health behaviors and health factors to follow for cardiovascular health.25 The importance of sleep is well documented.26 Stress management is also critical for physical and mental health.27 Mental stress can increase inflammatory markers, increase blood pressure, and play a role in insulin resistance and adiposity.28 This stress may be counteracted by resilience activities like 13 minutes of meditation a day.29 The Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, highlighted the importance of social connection for health. He declared that the United States was experiencing an epidemic of loneliness and called on the health care sector to take action.30 Another lifestyle factor to consider is the use of risky substances, including tobacco31 and the excessive use of alcohol because it is also adding to poor health outcomes.32

Lifestyle medicine is defined as “a medical specialty that uses therapeutic lifestyle interventions as a primary modality to treat chronic conditions including, but not limited to, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.”33 These 6 pillars of LM include:33

-

1.

a whole-food, plant-predominant eating pattern;

-

2.

routine physical activity (PA);

-

3.

restorative sleep;

-

4.

stress management;

-

5.

avoidance of risky substances;

-

6.

positive social connections.

The practice of LM is best accomplished with an interprofessional team trained in LM.34,35 Not only do LM physicians and HCPs need to know the guidelines for each pillar, but they also need to understand how to empower patients to make lifestyle changes.36 Empowering patients to change requires a set of skills not often emphasized in medical school or residency training.37 Lifestyle medicine clinicians work to collaborate with their patients to create personalized SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timebound) goals.38 Keeping up with the latest evidence-based practices allows LM clinicians to be effective with their counseling and comprehensive in their approach by factoring in essential areas such as social determinants of health, health equity, and nutrition insecurity. Referring to lifestyle behaviors such as eating as eating “patterns” rather than eating “choices and decisions” is now recommended, as is avoiding the use of the term “willpower” when speaking to patients about lifestyle change.39

Opportunities for Integrating LM into the Continuum of Education

Primary and Secondary Education

The 6 LM pillars can be introduced as early as elementary, middle, and high school. Electives in middle school and high school focused on LM have been successfully implemented.40 At this young age, LM classes should focus on inspiring young people to enjoy healthy lifestyle behaviors through informational and experiential learning.41 The American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) has a free full curriculum with slide decks and a teacher’s manual replete with suggested activities that accompany the Teen Lifestyle Medicine Handbook42 to help teachers deliver LM courses. Medical residents have used the teen curriculum to teach high school students in underserved areas of Boston.43 These same teen resources were used to help create an LM microcredential for high school students.44 Figure 1 shows a summary of LM education opportunities available across the continuum. Further options with links can be found in Supplemental Table (available online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org).

Figure 1.

Integration of lifestyle medicine content into medical and health professions curricula. CE, continuing education; CME, continuing medical education; LMIG, Lifestyle medicine interest groups.

Associate and Bachelor’s Education

Multiple college faculty across the country are leading efforts to move LM into premedical and undergraduate health professions curricula through didactic courses and experiential learning opportunities. Core and elective LM course options introduce LM concepts as well as different career paths in health professions. Lifestyle medicine can be introduced as part of other entry-level science courses, such as nutrition. Interdisciplinary experiences like student-run clinics provide opportunities to learn how to collaboratively apply LM in the clinical setting.

The ACLM offers a full LM 101 Curriculum, including a teacher’s manual and slide decks for 13 modules. This curriculum covers the science of the 6 pillars and the art of putting the pillars into practice with counseling strategies. This LM 101 Curriculum follows the 13 chapters in the Lifestyle Medicine Handbook making it a readymade option for faculty. Faculty from different universities have used this curriculum to teach LM in bachelor’s and master’s courses.45

Graduate Health Professions Education

Professors in graduate health profession master’s and doctorate programs can incorporate LM-related content and activities within their didactic and clinical courses. These courses can be effective online, hybrid,45 or in person. Upon graduation, students enrolled in ACLM-approved Academic Pathway programs receive credit for meeting some or all prerequisites for the ACLM certification examination.33

LM Education in Undergraduate Medical Education

Current State of Undergraduate Medical Education

On average, US medical schools provide only 14.3 hours of nutrition education, mostly during preclinical training.18 It has been reported that medical schools offered about 12 hours of education on substance use disorders, but this was in 2001,46 with unpublished data47 that has been cited for over 20 years, even by the New York Times in 2018.48 In response to the opioid epidemic, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) ran an Opioid Education Challenge Grant Program in 2019. According to the AAMC, in 2021-2022, most medical schools offered a course on substance use disorder recognition and treatment.49 Required PA education is only present in 17% of US medical schools,50 with an average of 8 hours of education on the subject.51 In 1993, less than 5% of US medical schools offered 4 or more hours of education on sleep.52 Almost 20 years later, medical schools across the globe were providing approximately 2.5 hours of sleep education.53 The hours of sleep medicine education ranged from 0 to 8 hours, with an average of 2.6 hours in 5 medical schools from Saudi Arabia.54 In the United Kingdom, 25 medical schools were surveyed, and the average time spent on sleep was 3.2 hours, slightly better than the global average.55 Little research data have been reported studying medical school education surrounding stress management and maintaining positive social connections.

According to the AAMC, the average contact hours of education in the first 2 years of medical school range from 635 to 799 hours per year.56 This demonstrates that, on average, each of these important LM pillars accounts for <1% of total education time in the preclinical years—a time when most of the basic medical education occurs.

Quantifying exact hours of LM content embedded in medical curricula is challenging as the pillars are often threaded into lectures, cases, and clinical rotations. Shifts toward competency-based medical education have the potential to allow students to learn and practice LM skills when aligned with the AAMC Entrustable Professional Activities and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies.57,58 The American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute have proposed frameworks for US medical schools to integrate learning objectives that will improve LM knowledge, skills, and competencies, and these efforts are needed to ensure that future physicians are well-prepared to address common lifestyle-related health issues.59, 60, 61

Improving LM in Undergraduate Medical Education

LM Student Interest Groups

Lifestyle medicine interest groups (LMIGs) are student-led organizations with faculty advisors that are focused on the 6 pillars. The first LMIG was created in the 2008-2009 academic year.62 Lifestyle medicine interest groups are supported at the undergraduate medical education (UME) and graduate medical education (GME) levels, and there are currently over 140 within various academic and health system programs, including 95 LMIGs in medical schools. Grounded in social learning theory,63 LMIGs nurture communities of learning and practice that can help students, faculty, and the local community build healthy habits through involvement in LM-related activities. This model of learning and teaching has been shown to be effective in increasing medical student knowledge and confidence in counseling on behavior change even after just an hour presentation.64 Similarly, just 1 hour of a virtual session on exercise prescription found that medical students and residents increased their knowledge and confidence after the intervention.65 To foster a national community and create resources that can be shared among all LMIGs, the ACLM holds 6 online meetings to gather LMIG members from various schools nationwide in the same virtual space. These meetings are recorded to create a repository of videos from national leaders in LM, which are available to all LMIGs.

These LMIGs provide a parallel curriculum62 that can be delivered as “lunch and learns” or evening workshops. Lifestyle medicine interest group leaders host events to support healthy habits for students, trainees, staff, and the local community. The ACLM LM 101 Curriculum can be used as the basis for the material presented on each pillar. There has been steady growth in the number of LMIGs in medical schools, bachelor’s programs, master’s programs, and doctorate programs, as well as the health systems council at ACLM.

Electives

Electives provide an opportunity to offer LM courses and meet required credits at the same time. Several LM electives and track structures have been described. The open access Foundations of Lifestyle Medicine Curriculum provides a comprehensive document including a summary of LM literature, goals, objectives, and assigned work for an LM elective, as well as a sample structure for the course.66 A culinary medicine elective provides a unique opportunity for an engaging and active learning pedagogy.67

Curricular Themes, Case Studies, Distinction, and Master’s Degree Programs

Only a small number of schools have been able to integrate LM content throughout the UME curriculum. Some schools are integrating LM education into existing curricula by including LM content in case studies, problem-based learning, and clinical activities in a theme, track, or thread.60 Other medical schools are offering distinction, concentration, or track programs in LM. By participating in a distinction program, medical students will graduate with an LM-focused expertise that will enhance their patient care and medical practice. A master’s degree in LM provides medical and health professionals the opportunity to add advanced skills and knowledge to their practice.

Resources to help medical school faculty integrate LM into their curricula include the open access LMEd curriculum providing about a dozen slide decks organized by organ system and several LM case studies. The ACLM UME Question Bank is available to aid faculty with evaluation of student LM knowledge.

Barriers to Implementing LM into UME

Because time is a large barrier to the implementation of new curricular topics in UME, integration of LM into existing courses allows for a comprehensive and holistic education of future HCPs, facilitating collaboration among faculty and alignment of priorities without the heavy burden of revamping the entire curriculum. One barrier to the inclusion of nutrition in medical education noted in the literature is competition with other medical disciplines for time and space in the curriculum.68 Other barriers include the lack of application of nutrition science into clinical practice, the perception that nutrition counseling is not the responsibility of the physician, poor collaboration with nutrition specialists, lack of prioritizing nutrition, and lack of faculty to teach the topic.69 For LM education in all 6 pillars, barriers include lack of time and space in the already full curriculum and lack of faculty who have knowledge and skills in LM topics, including the guidelines, research, and different dosing of LM interventions. Social, commercial, and political pressures may influence content decisions within UME, and it is important to acknowledge, understand, and navigate these forces as new content is considered. Undergraduate medical education needs to use strategies to teach clinically relevant and practical LM content. These teaching opportunities can be created in ways that do not compete with established curricular priorities, but the long-term goal is to have LM embedded into the core curriculum. Collaborating and connecting with faculty already teaching in the core curriculum is important. “The key to spreading lifestyle medicine is connection: connection with colleagues, connection with research, connection with CME, connection with students, and connection with community.”43

Bridging the UME GME Transition for LM

The ACGME uses a conceptual framework centered on 6 core competency domains to describe the requirements for a “trusted physician to enter autonomous practice.”57 These core competency domains include the following:

-

1.

Professionalism;

-

2.

Patient care and procedural skills;

-

3.

Medical knowledge;

-

4.

Practice-based learning and improvement;

-

5.

Interpersonal and communication skills;

-

6.

Systems-based practice.

The LM UME core competencies map across the ACGME’s 6 competency domains.70 Continuing to update these competencies and respond to the needs of patients and medical communities is important. Competencies, for example, on determining when LM should be started as an adjunct to a prescription for medication or other therapeutic intervention and how to deprescribe medication when a patient has been responding to lifestyle modifications are all important to consider.

Graduate Medical Education

Current State of Incorporation of LM Pillars Into GME Curricula

Despite patients’ reliance on their physician for preventive medical guidance, practicing physicians may be uncomfortable counseling patients in lifestyle modifications. A lack of training in GME can lead to low self-efficacy and a lack of counseling in nutrition. Of 451 family physicians in British Columbia surveyed, 82.3% reported inadequate training in nutrition, and they also reported that the maximal impact on their nutrition education came from self-directed learning, with only 30% using nutrition resources.71 In another study, 95% of 930 cardiologists surveyed believed nutrition counseling was part of their personal responsibility to their patients, and 90% reported no or minimal nutrition education.72 In a different study, it was reported that of 40 internal medicine program directors surveyed, less than 50% reported providing “quite a bit/extensive training in dietary counseling” on hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity.73 The most frequently noted “moderate-to-major barriers” to education were competing curricular demands, lack of physician faculty with expertise in nutrition, inadequate financial resources, and lack of administrative support.73 In that same study, 61% of 133 residents reported having very little or no training in nutrition.73 Interestingly, the eating habits of the residents, specifically how many vegetables and fruits they consumed, had an impact on their nutrition counseling.73

Of 72 residency directors surveyed across family medicine, internal medicine, surgery, and anesthesia, 72% thought nutrition should be required, 63% felt lack of adequate resources was a barrier to implementing nutrition education, 43% noted other requirements and time as a barrier, and 28% noted faculty issues.74 Participation in interactive online nutrition courses provides opportunities to improve nutritional knowledge and enhance the residents’ attitudes that maintaining a healthy diet is important for patient care and their own self-care.75 Recognizing the importance of nutrition for medical students and trainees, the ACGME, along with the AAMC and the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, held a summit to address ways to include more nutrition in medical education.76 In an editorial, National Institutes of Health Office of Nutrition Research Director Dr Andrew Bremer clearly expressed the urgent need to prioritize nutrition in medical education.77

There are similar trends with the PA pillar in terms of barriers and training. Systematic reviews on this topic reveal a lack of evidence for PA education in family medicine residency programs.78 Lack of time and training in primary care providers were noted as barriers to PA counseling.79 Of 25 Ohio family medicine, internal medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology programs in 1 study, only 4 programs provided guidance on how to use and implement obesity, nutrition, and PA guidelines, and the 25 programs offered an average of only 2.8 hours of didactics related to obesity, nutrition, and PA.80 Another study revealed that only 26% of 115 US pediatric residencies had planned PA counseling curriculum.81 Programs with a PA curriculum noted a lack of time and space in the current curriculum to be a major barrier to developing curriculum, whereas those without a curriculum noted a lack of trained faculty to be a major barrier.81

Sleep medicine is a well-defined subspecialty with board certification requirements and over 100 sleep medicine fellowship programs. Despite this, education at the prerequisite residency stages is lacking. Researchers leading a global study on this topic revealed that 152 pediatric programs across 10 countries averaged 4.4 hours dedicated to formal sleep education, with 23.3% of programs offering none.82 In a study of 479 residencies across family medicine, ear, nose, and throat (ENT), psychiatry, pulmonary and critical care, neurology, and pediatrics, researchers found that more than half of the ENT, family medicine, and psychiatry programs had no faculty member who specialized in sleep medicine and the mean duration of sleep education was 4.75 hours.83 Only 41.3% of 46 ENT programs in another study had a faculty member who was board certified in sleep medicine or who spent more than 50% of their practice on sleep medicine, underscoring the lack of trained faculty.84 The programs with trained faculty were markedly more likely to respond “extremely” or “very” satisfied with resident sleep exposure than those without.84

With respect to research about education in the stress management pillar, from the results of 1 study, 83% of 212 family medicine residencies provided lectures/workshops on stress management, 79% provided residency retreats, and there was a strong relationship between programs that had lectures on stress management techniques for patients and those that had education for resident stress management.85 To help with stress management during residency, 97% of the 212 family medicine residencies surveyed provided access to counselors and mental health services, and 97% provided Balint/support group access.85 A Balint group consists of 6-10 members and 1-2 facilitators/leaders where an hour is spent discussing a case from memory in a space without judgment.86

The strength of positive social connections in building stress resilience among residents is well known and has been incorporated into GME-level care for residents through programs such as Balint groups and support groups, which can help reduce burnout, and there is an emphasis on the fact that peer social support is an important part of overall support throughout the training process.86 Although there is a strong case for creating structured opportunities for social connections in the GME space, education on social connections for residents is lacking.87

Contrary to what is found for nutrition, PA, stress, sleep, and social connection, substance use content in GME curricula has been persistently evolving and expanding. Highly successful national training programs have been documented. One example is the National Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), which has trained thousands of residents to screen for substance use, provide brief interventions if appropriate, or refer to appropriate treatment programs on the basis of the patient’s needs.88 Respondents of the grant in SBIRT stated that 100% of the residents trained in SBIRT utilized SBIRT clinically afterward.88 These grant-funded national programs demonstrate that GME can provide sufficient education in LM when appropriate support, resources, and training (of both faculty and residents) are offered. Programs such as SBIRT can provide a basis for a curriculum, which can then be modified to better fit the specific needs of different specialties. A competency-based substance use disorder training program for family medicine residencies on the basis of SBIRT practice was developed as an open access curriculum that can meet both the specific needs of family medicine programs and address the common barriers identified by these programs.89 Given the persistent barriers of a lack of time, a lack of resources, and a lack of LM expertise, creating large-scale national resources and training with subsequent specialized curricula to meet the specific needs of the diverse specialties can lead to easier integration, training, and practice of LM among HCPs in all fields. Information on medical education in the areas of the 6 pillars of LM is summarized in Table 118,49, 50, 51,53,73,74,81, 82, 83,85,86,90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103 for both UME and GME.

Table 1.

Estimates of Current Lifestyle Medicine in Undergraduate Medical Education and Graduate Medical Education

| Pillar | UME | GME |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | Average of 14.3 h largely occurring in preclinical courses and 71% of US medical schools provided less than the recommended 25 h.18 | 10% (n=133) of IM residents reported receiving nutrition education via a formal curriculum. 61% of the residents reported having none or little bit of training in nutrition.73 |

| 72% (n=72) US residency program directors thought a nutrition course should be required. Only 26.4% of programs had a formal course in nutrition education and length of course varied from a single 45-min to 10 1-h long sessions.74 | ||

| Physical Activity | 17% of US medical schools offer a required course on exercise and 35.5% of programs offered courses with the terms exercise prescription, exercise, fitness, or physical activity in the course description or list of topics.50 | Less than 1% of total didactic and clinical education time for internal medicine residents is devoted to exercise.90 |

| Of 74 US medical schools surveyed, an average of 8 h of required physical activity education was offered during the 4 y of medical school.51 | Less than 50% of Canadian Family Medicine Residency Program directors reported including structured physical activity counseling education into resident curriculum and teaching.91 | |

| 24-h curriculum delivered over 6-12 wk was feasible, efficacious, well received, and easy to include in the integrative residency curriculum.92 | ||

| Sleep | Sleep education was noted to be under 2.5 h and about one third of international schools sampled provided no sleep education.53 | 152 pediatric programs across 10 countries averaged 4.4 h dedicated to formal sleep education with 23.3% of programs offering none.82 |

| Of 479 residencies (family medicine, otorhinolaryngology, psychiatry, pulmonary and critical care, neurology, and pediatrics) more than 50% of the ear, nose, and throat (ENT), family medicine, and psychiatry programs had no faculty member who specialized in sleep medicine and the mean duration of sleep education was 4.75 h.83 | ||

| Stress | Insufficient data to report on the number of hours of stress management material in the medical school curriculum. | 83% of family medicine residencies (n=212) provided lectures or workshops on stress management.85 |

| There was evidence of improved mindfulness and relationships with peers after an elective course on mind-body medicine that was targeted to both medical student well-being and patient care.93 | 79% of family medicine residencies provided residency retreats.85 | |

| Smoking cessation; substance use disorder education | Of 561 international medical schools: 27% taught a specific module on tobacco; 77% integrated teaching on tobacco; 31% taught about tobacco informally as the topic arose; 4% did not teach about tobacco.94 | 60% of US OB/GYN residencies (n=158) did not have formal curriculum in smoking cessation.96 |

| There was evidence that as little as 2 h of interactive, case-based education in the fourth year of medical school could have a considerable impact.95 | 65% of US OB/GYN residencies did not evaluate residents’ competence on smoking cessation counseling.96 | |

| According to 2021-2022 data from AAMC, 149/155 medical schools offered preclerkship courses on recognition of opioid substance use disorders and 150/155 had required clerkships in this topic.49 | 42%-57% of US OB/GYN residencies spent less than 1 h per year on tobacco use education.96 | |

| 28.6% (n=227) of family medicine directors surveyed, reported a required addiction medicine curricula.97 | ||

| Positive relationships and social connection; behavior change motivational interviewing (MI); and health coaching | Insufficient data to report on the number of hours of social connection material in the medical school curriculum. | Peer support is an important component for residents. Balint groups are a good example, Balint groups increases a participant’s coping ability, psychological mindedness, and patient-centredness.86 |

| There is evidence that social support for medical students needs to be explored as cultural and contextual support specific to the students is crucial for creating safe learning spaces.98 | National survey results from internal medicine and medicine/pediatric residents revealed 67% of residents received MI training in medical school, 27.2% received it in residency, and 22.7% received it in both. 23.5% received no training in MI.101 | |

| No reliable data on the number of medical schools that provide MI training, or the number of hours included in schools that do have this training. | A 12-h MI course increased the use of MI by residents in a written measure, and the course was rated favorably.102 | |

| A pilot program in Germany using e-learning, lectures, and small groups to teach MI to medical students was effective with objective MI skills improving.99 | Even a 1-h didactic session in MI could be beneficial.103 | |

| Little available research on medical students and health coaching but what does exist is promising.100 |

Abbreviations: AAMC Association of American Medical Colleges; GME, graduate medical education; IM, internal medicine; OB/GYN, Obstetrics and gynaecology; UME, undergraduate medical education.

Improving LM Education in GME

Individuals in medical residency programs across the United States can access ACLM’s lifestyle medicine residency curriculum (LMRC). This didactic and practicum offering began in 2018 with 4 sites and is now being used in over 170 sites including 368 residency programs in a variety of specialties. Didactic components of the LMRC require 40 hours of interactive virtual learning and 60 hours of application activities. The curriculum is based on the LM core competencies.5 The practicum component includes at least 400 LM-related patient encounters, exposure to therapeutic lifestyle change programs, and group facilitation. Upon completing a primary residency program and LMRC, physicians are eligible to take the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine (ABLM) certification examination. Feedback has been positive in that the material taught is considered engaging, and residents participate with enthusiasm and the desire to continue learning.104 The ACLM is in the process of a full evaluation and research protocol to test the impact of the LMRC. There is one approved LM intensivist fellowship with the goal of creating many more throughout the country in the coming years.105

Core Competencies in LM

In 2010, the first paper describing the core competencies in LM was published106 and it was updated in 2022.106 Below is a list of the 10 core competency areas in LM. There are a total of 88 competencies that relate to these 10 core competency categories.

The 10 Core Competency Areas in LM

-

1.

Introduction to LM;

-

2.

The role of the practitioner’s personal health and community advocacy;

-

3.

Nutrition science, assessment, and prescription;

-

4.

Physical activity science, assessment, and prescription;

-

5.

Sleep health science and interventions;

-

6.

Treating tobacco use disorder and managing other toxic exposures (including vaping, alcohol use, and other illicit substances);

-

7.

Key clinical processes in LM;

-

8.

Fundamentals of health behavior change;

-

9.

Emotional and mental health assessment and interventions;

-

10.

The role of connectedness and positive psychology.

Lifestyle medicine practices and principles align well with the ACGME’s 6 core competency domains, which include patient care, medical knowledge, professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, practice-based learning, and improvement and systems-based practice.107 Table 2 provides a framework to map the 88 LM subcompetencies as presented in the updated 2022 article.5

Table 2.

Mapping the LM Subcompetencies to the ACGME Core Competencies

| ACGME Core Competencies |

| Patient care and procedural skills |

| Medical knowledge |

| Practice-based learning and improvement |

| Interpersonal and communication skills |

| Professionalism |

| Systems-based practice |

| LM Subcompetencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; LM, lifestyle medicine.

It is important for relatively newer specialties such as LM to consider how best to integrate their work into the existing frameworks and initiatives of more established organizations. For example, how should LM education be considered in the context of the ACGME’s core competencies as well as specialty-specific ones? There are opportunities to explore ways of meaningfully integrating LM core competencies into primary care with family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. It will be important to embed nutrition and LM into specialties where these topics are most relevant, such as cardiology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology.108 Another avenue to consider is developing Clinician Educator Milestones109 for the LM core competencies. These milestones represent a combined effort and collaboration among the ACGME, the Accreditation Council for CME, the AAMC, and the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine.109 The milestones are subcompetencies that help faculty develop and improve teaching and learning skills across the continuum of medical education. This competency-based approach should be the main focus of LM education.

Board Certification in LM

Certification distinguishes physicians and HCPs as ABLM or ACLM diplomates with expert knowledge, having achieved competency in LM. Physicians seeking ABLM certification complete an experiential pathway. They must be board certified in their primary specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties. Medical residents can follow the educational pathway, which involves completion of the LMRC. There is also an option for experienced LM physicians to become LM intensivists, which requires previous ABLM board certification along with a series of documented clinical disease remission patient outcomes. Nonphysicians can also be certified in LM. Health care professionals holding a master’s or doctorate degree can achieve certification through ACLM. This pathway can also be experiential or educational through participation in an ACLM-approved Academic Pathway program. The International Board of Lifestyle Medicine certifies physicians and professionals globally.

Pathways Forward with LM Education

The Readiness to Change Model110 can be applied when supporting medical schools and other HCP education programs. Depending on the stage of change for the academic center, different implementation suggestions apply. Stage-specific strategies are listed for each stage in Table 3.

Table 3.

Suggestions for Including More LM Based on Readiness for Change for Medical and Health Professional Schools and Programs

| Stage of change | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Precontemplation |

|

| |

| Contemplation |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Preparation |

|

| |

| |

| Action |

|

| |

| |

| Maintenance |

|

|

Abbreviations: ACLM, American College of Lifestyle Medicine; LM, lifestyle medicine.

In addition to understanding the different stages of change an academic institution may be in, it is important to identify common barriers holding up progress and to provide solutions around these barriers. Table 443,111, 112, 113, 114, 115 reviews barriers and solutions.

Table 4.

Common Barriers to Including Lifestyle Medicine in Medical and Health Professional Education

| Barriers | Solutions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Core curriculum is full | Offer a separate elective Create optional opportunities for LM education Parallel curriculum Weave LM into current courses and cases Create a Master’s program |

|

| Not enough trained faculty to teach | Increased training in LM Increased knowledge Bring in experts Live or recorded lecture offerings |

|

| Lack of established resources | Complementary resources Resources with costs associated Viewing documentaries Lifestyle medicine textbooks |

|

| Lack of funding | Apply for research grants to study the impact of lifestyle medicine education courses and workshops on medical students, residents, and physicians |

|

| Lack of understanding of and familiarity with LM Lack of LM questions on licensing examinations |

Educate deans Educate faculty Educate students Educate medical school course directors and residency program directors Publish articles in the medical literature Bring awareness to current LM research Collaborate with STEP 1, 2, and 3 licensing boards |

Give grand rounds on a LM topic at the hospital. Deliver LM workshop at ACGME and AAMC national meetings Create special lifestyle medicine editions in major medical journals Run a journal club on LM topics43 ACLM UME Question Bank and other resources to help jump start question creation |

Abbreviations: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ABLM, American Board of Lifestyle Medicine; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ACLM, American College of Lifestyle Medicine; IBLM, International Board of Lifestyle Medicine; LM, lifestyle medicine; LMIG, lifestyle medicine interest group; LMRC, lifestyle medicine residency curriculum; UME, undergraduate medical education.

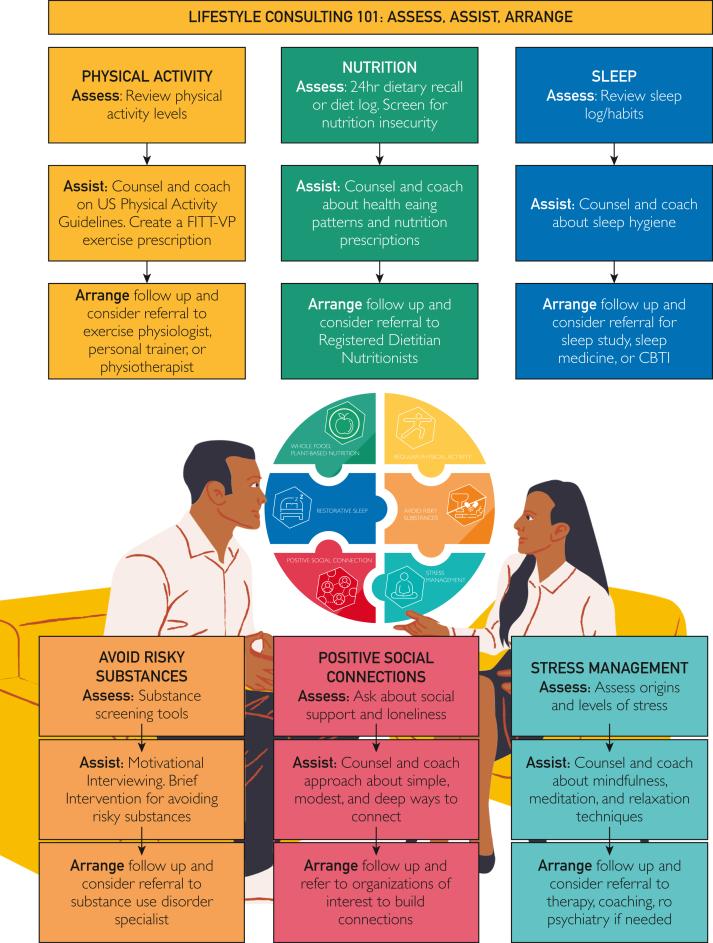

Ideally, medical and HCP students will learn the research, guidelines, and behavior change strategies to help patients adopt and sustain healthy lifestyles for a lifetime. This will involve assessing, assisting, and arranging for follow-up and referral for all 6 pillars. This follows the 5 As (assess, advise, agree, assist, arrange),116 which most clinicians know and understand. Figure 2 shows some of the many ways physicians and HCPs can empower patients to adopt and sustain healthy lifestyles. In this version, the advise, agree, and assist steps were condensed into 1 step labeled “assist.” The first step of assessing the 6 pillars is accomplished by asking open-ended questions and using evidence-based tools. Examples for each pillar include the ASA24 Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool,117,118 Physical Activity Vital Signs,119 Perceived Stress Scale,120 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,121 the University of British Columbia’s University of British Columbia State Social Connection Scale,122 and alcohol screening with Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).123 Nutrition, sleep, and exercise logs are also useful to establish a baseline and track progress.

Figure 2.

Lifestyle consulting 101: assess, assist, and arrange for the 6 pillars of lifestyle medicine. Source: Pillars of Lifestyle Medicine graphic logo included with permission from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine.

Lifestyle medicine education emphasizes that the 6 pillars are like medicine with prescription doses and intensities.124 The higher the dose and intensity, the greater the change, and the more likely there will be a need for medication deprescribing, especially with chronic conditions like hypertension and type 2 diabetes. The LM clinician must consider the individual patient, their social determinants of health, their readiness for change, and other personal factors to develop a specific prescription that clearly identifies the frequency, intensity, time, and type of interventions. These can be remembered as F.I.T.T. prescriptions and can be created for all 6 pillars.113 For example, an exercise prescription may be 3 times a week, at moderate intensity, 50 minutes of stationary biking, whereas a nutrition prescription may be once a day, ¼ cup of almonds for a snack at 3 pm, based on someone’s unique goals.

There are several options for medical schools and HCP schools to incorporate more LM education. Starting with an LMIG, they should identify the faculty and students able to put time and energy into the 6 pillars and then work toward an LM curricular theme and offer electives such as culinary medicine. Taking deliberate steps forward to plan and integrate LM into UME and GME is a vital way to build momentum. Analyzing the programs’ readiness for change, current barriers to implementation, and identifying resources that can be used ensures the process is targeted to the needs of the specific school and is in alignment with the LM curriculum implementation standards.70 Evaluation drives curriculum. When the national medical examinations and board certifications include more questions on the 6 pillars, medical and health professions school faculty and deans will be required to fortify these topics in the core curriculum. Lifestyle medicine champions need to take the next step toward integrating LM into UME and GME.

Summary of Recommendations Future Directions for LM Education

-

•Promote awareness of LM

-

oEstablish-of LMIGs.

-

oTrain the trainer and become certified in LM: train faculty, course directors, and program directors in LM so that they can become certified by ABLM/International Board of Lifestyle Medicine/ACLM.

-

oUse grand rounds, electives, webinars, lunch and learns, national meeting presentations, and workshops to teach others about LM.

-

oPromote LM research via grants and share current research through journal clubs.

-

oLobby for policy change by partnering with leaders at AAMC and ACGME as well as government officials.

-

o

-

•Revamping current curricula

-

oDuring curricular review, discuss how to fully integrate LM competencies into existing curricula.

-

oConsider the addition of established curricular resources into UME and GME, such as the LM101 curriculum or LMRC.

-

oIdentify current barriers to implementation and establish a task force to address barriers.

-

oImplement LM competencies into UME and GME. Redefine and refine competencies to better suit various residency/fellowship needs.

-

oEstablish evaluation metrics to ensure competencies are met. Consider OSCEs, 360° evaluations, quizzes, direct observation tools, or other evaluation tools to ensure LM education is valuable, competency-based, and put into practice.

-

o

Figure 3 shares several recommendations for focus areas to move forward with LM education.

Figure 3.

Focus areas to move forward with lifestyle medicine education. AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; CE, continuing education; LM, lifestyle medicine.

Conclusion

Reversal of the chronic disease burden requires a paradigm shift in the approach to patient care where chronic disease guidelines emphasizing lifestyle interventions and offering optimal dosages and intensities, are followed. Lifestyle medicine is high-value, person-centered care that encourages the patient to be active in their own health outcomes through therapeutic lifestyle interventions where, in most cases of chronic disease, “LM pillars are preferred to pills and procedures.” Physicians and HCPs are responsible for offering LM as an option for prevention and treatment for their patients with chronic medical conditions. Lifestyle medicine includes a team approach centered on the patient, and all members of the team play a role in the process. Thus, they all need education. Lifestyle medicine education must be competency-based to provide the foundation for physicians and HCPs to be knowledgeable, trained, and skilled at managing lifestyle-related chronic conditions. Lifestyle medicine is urgently needed to reverse the course of the chronic disease crisis. This article is a call to action to make the principles of LM a curricular priority and advocate for these principles as HCPs. The collaborative efforts of health and medical educators, stakeholders, policymakers, and accreditation organizations will help make change happen. Lifestyle medicine is the antidote to the chronic medical conditions plaguing the nation and the world. The time is now for LM education and training to be a priority.

Potential Competing Interests

Dr Frates has served as a consultant for Jenny Craig Scientific Advisory Board, obVus Solutions, and Clearing.com. Dr Freeman is the Director of Workforce Development at the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and President of the Indiana Lifestyle Medicine Network; receives grant funding through the Ardmore Institute of Health. Dr Co is one of the Board of Directors, ACGME. Dr Bernstein receives royalties as a Nutrition Textbook Author for Jones and Bartlett Learning. The other author reports no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Pollard and Morgan Snyder for reference assistance; Veronica Moreno and Connie Cordova for their expertise with image design; and Rahul Anand, MD for carefully reviewing the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Virani S.S., Newby L.K., Arnold S.V., et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2023;148(9):e9–e119. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rock C.L., Thomson C., Gansler T., et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):245–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association 5. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S46–S60. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obesity and healthy lifestyle: clinical guidance and practical resources. American Academy of Family Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/clinical-guidance-obesity.html

- 5.Lianov L.S., Adamson K., Kelly J.H., Matthews S., Palma M., Rea B.L. Lifestyle medicine core competencies: 2022 update. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;16(6):734–739. doi: 10.1177/15598276221121580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panigrahi G., Goodwin S.M., Staffier K.L., Karlsen M. Remission of type 2 diabetes after treatment with a high-fiber, low-fat, plant-predominant diet intervention: a case series. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023;17(6):839–846. doi: 10.1177/15598276231181574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frattaroli J., Weidner G., Merritt-Worden T.A., Frenda S., Ornish D. Angina pectoris and atherosclerotic risk factors in the multisite cardiac lifestyle intervention program. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livingston K.A., Freeman K.J., Friedman S.M., et al. Lifestyle medicine and economics: a proposal for research priorities informed by a case series of disease reversal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11364. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chronic diseases in America Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm

- 10.Frame L.A. Nutrition, a tenet of lifestyle medicine but not medicine? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5974. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anis N.A., Lee R.E., Ellerbeck E.F., Nazir N., Greiner K.A., Ahluwalia J.S. Direct observation of physician counseling on dietary habits and exercise: patient, physician, and office correlates. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton C.B., Goodwin M.A., Stange K.C. Direct observation of nutrition counseling in community family practice. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(3):174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kushner R.F. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24(6):546–552. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley J., Ball L., Hiddink G.J. Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3(9):e379–e389. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vetter M.L., Herring S.J., Sood M., Shah N.R., Kalet A.L. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(2):287–298. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Research Council . National Academies Press; 1985. Division on Earth and Life Studies, Commission on Life Sciences, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee on Nutrition in Medical Education. Nutrition Education in U.S. Medical Schools.https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=PN3FNujr-IoC [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cresci G., Beidelschies M., Tebo J., Hull A. Educating future physicians in nutritional science and practice: the time is now. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019;38(5):387–394. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1551158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams K.M., Butsch W.S., Kohlmeier M. The state of nutrition education at US medical schools. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015(4):1–7. https://downloads.hindawi.com/archive/2015/357627.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malatskey L., Bar Zeev Y., Polak R., Tzuk-Onn A., Frank E. A nationwide assessment of lifestyle medicine counseling: knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of Israeli senior family medicine residents. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01261-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe M., Leidel A., Krishnan S.M., Weber A., Rubenfire M., Jackson E.A. Patient-related diet and exercise counseling: do providers’ own lifestyle habits matter? Prev Cardiol. 2010;13(4):180–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2010.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsui J.I., Dodson K., Jacobson T.A. Cardiovascular disease prevention counseling in residency: resident and attending physician attitudes and practices. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(8):1080–1083. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15303414 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bleich S.N., Bennett W.L., Gudzune K.A., Cooper L.A. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Department of HHS . 2nd ed. US DHHS; 2024. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=6j6c0AEACAAJ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pegg Frates E., McBride Y. Its fun: a practical algorithm for counseling on the exercise prescriptions: a method to mitigate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress-related illness. Clin Exp Psychol. 2016;02(2) doi: 10.4172/2471-2701.1000116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd-Jones D.M., Allen N.B., Anderson C.A.M., et al. Life’s essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146(5):e18–e43. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cappuccio F.P., D’Elia L., Strazzullo P., Miller M.A. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stress in America 2023 American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2023/collective-trauma-recovery

- 28.Osborne M.T., Shin L.M., Mehta N.N., Pitman R.K., Fayad Z.A., Tawakol A. Disentangling the links between psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(8) doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basso J.C., McHale A., Ende V., Oberlin D.J., Suzuki W.A. Brief, daily meditation enhances attention, memory, mood, and emotional regulation in non-experienced meditators. Behav Brain Res. 2019;356:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) New surgeon general advisory raises alarm about the devastating impact of the epidemic of loneliness and isolation in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/03/new-surgeon-general-advisory-raises-alarm-about-devastating-impact-epidemic-loneliness-isolation-united-states.html

- 31.TobaccoFree Health effects. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/index.htm

- 32.Drinking too much alcohol can harm your health Learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm

- 33.Home American College of Lifestyle Medicine. https://lifestylemedicine.org/

- 34.Kent K., Johnson J.D., Simeon K., Frates E.P. Case series in lifestyle medicine: a team approach to behavior changes. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(6):388–397. doi: 10.1177/1559827616638288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarke C.A., Frates J., Pegg Frates E. Optimizing lifestyle medicine health care delivery through enhanced interdisciplinary education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(6):401–405. doi: 10.1177/1559827616661694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frates E.P., Moore M.A., Lopez C.N., McMahon G.T. Coaching for behavior change in physiatry. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(12):1074–1082. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31822dea9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frates E.P., Bonnet J. In: Nutrition in Lifestyle Medicine. Rippe J.M., editor. Springer International Publishing; 2017. Behavior change and nutrition counseling; pp. 51–84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bovend’Eerdt T.J.H., Botell R.E., Wade D.T. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):352–361. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olstad D.L., Kirkpatrick S.I. Planting seeds of change: reconceptualizing what people eat as eating practices and patterns. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:32. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01102-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolferz R. J.r., Arjani S., Bolze A., Frates E.P. Students teaching students: bringing lifestyle medicine education to middle and high schools through student-led community outreach programs. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(4):371–373. doi: 10.1177/1559827619836970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tollefson M., Kees A., Bolze A., Wolferz R., Plaven B., Frates E.P. A call to action for intermediate and secondary school lifestyle medicine education: instating healthy teen behaviors. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(1):43–46. doi: 10.1177/1559827619879065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frates B., Palven B., Watts B., Agarwal N., Dalal M., Tollefson K. American College of Lifestyle Medicine; 2020. The teen lifestyle medicine handbook: the power of healthy living. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frates B. Incorporating lifestyle medicine into your academic institution and hospital setting: the key is connection. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023;17(4):490–493. doi: 10.1177/15598276231170547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lifestyle medicine for teens—University of North Texas Health Science Center. https://learningplus.unthsc.edu/courses/lifestyle-medicine-for-teens

- 45.Frates E.P., Xiao R.C., Sannidhi D., McBride Y., McCargo T., Stern T.A. A web-based lifestyle medicine curriculum: facilitating education about lifestyle medicine, behavioral change, and health care outcomes. JMIR Med Educ. 2017;3(2):e14. doi: 10.2196/mededu.7587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller N.S., Sheppard L.M., Colenda C.C., Magen J. Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disorders. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):410–418. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller N.S., Sheppard L.M., Yang L., Megan J. A survey of curriculum for alcohol and drug disorders in medical schools through the United States [unpublished]. cited in Pokorny AD, Solomon J. A follow-up survey of drug abuse and alcoholism reaching in medical schools. J Med Educ. 1983;58(4):316–321. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffman J. Most doctors are ill-equipped to deal with the opioid epidemic. Few medical schools teach addiction. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/10/health/addiction-medical-schools-treatment.html Published online September 10, 2018.

- 49.Opioid addiction content in required curriculum Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/data/opioid-addiction-content-required-curriculum

- 50.Dirks-Naylor A.J., Crump L.H., Le N. Exercise prescription-related course offerings in US medical schools. J Health Sci Educ. 2021;5(4):1–5. https://escires.com/articles/Health-1-217.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoutenberg M., Stasi S., Stamatakis E., et al. Physical activity training in US medical schools: preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43(4):388–394. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen R.C., Rosekind M., Rosevear C., Cole W.E., Dement W.C. Physician education in sleep and sleep disorders: a national survey of U.S. medical schools. Sleep. 1993;16(3):249–254. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mindell J.A., Bartle A., Wahab N.A., et al. Sleep education in medical school curriculum: a glimpse across countries. Sleep Med. 2011;12(9):928–931. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Almohaya A., Qrmli A., Almagal N., et al. Sleep medicine education and knowledge among medical students in selected Saudi Medical Schools. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:133. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romiszewski S., May F.E.K., Homan E.J., Norris B., Miller M.A., Zeman A. Medical student education in sleep and its disorders is still meagre 20 years on: a cross-sectional survey of UK undergraduate medical education. J Sleep Res. 2020;29(6) doi: 10.1111/jsr.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weeks of instruction and contact hours required in medical school programs. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/data/weeks-instruction-and-contact-hours-required-medical-school-programs

- 57.Common program requirements Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/programs-and-institutions/programs/common-program-requirements

- 58.The Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for entering residency. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Hivert M.F., Arena R., Forman D.E., et al. Medical training to achieve competency in lifestyle counseling: an essential foundation for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases and other chronic medical conditions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(15):e308–e327. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aspry K.E., Van Horn L., Carson J.A.S., et al. Medical nutrition education, training, and competencies to advance guideline-based diet counseling by physicians: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(23):e821–e841. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Horn L., Lenders C.M., Pratt C.A., et al. Advancing nutrition education, training, and research for medical students, residents, fellows, attending physicians, and other clinicians: building competencies and interdisciplinary coordination. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(6):1181–1200. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pojednic R., Frates E. A parallel curriculum in lifestyle medicine. Clin Teach. 2017;14(1):27–31. doi: 10.1111/tct.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization. 2000;7(2):225–246. doi: 10.1177/135050840072002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frates E.P., Xiao R.C., Simeon K., McCargo T., Guo M., Stern T.A. Increasing knowledge and confidence in behavioral change: a pilot study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6) doi: 10.4088/PCC.16m01962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sprys-Tellner T., Levine D., Kagzi A. The application of exercise prescription education in medical training. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2023;10 doi: 10.1177/23821205231217893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bansal S., Cramer S., Stump M., Wasserstrom S. Lifestyle medicine electives: options for creating curricula within medical school training. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023;17(6):754–758. doi: 10.1177/15598276221147181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hauser M.E., Nordgren J.R., Adam M., et al. The first, comprehensive, open-source culinary medicine curriculum for health professional training programs: a global reach. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(4):369–373. doi: 10.1177/1559827620916699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thircuir S., Chen N.N., Madsen K.A. Addressing the gap of nutrition in medical education: experiences and expectations of medical students and residents in France and the United States. Nutrients. 2023;15(24):5054. doi: 10.3390/nu15245054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mogre V., Stevens F.C.J., Aryee P.A., Amalba A., Scherpbier A.J.J.A. Why nutrition education is inadequate in the medical curriculum: a qualitative study of students’ perspectives on barriers and strategies. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trilk J.L., Worthman S., Shetty P., et al. Undergraduate medical education: lifestyle medicine curriculum implementation standards. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(5):526–530. doi: 10.1177/15598276211008142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wynn K., Trudeau J.D., Taunton K., Gowans M., Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(3):e109–e116. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20228290 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Devries S., Agatston A., Aggarwal M., et al. A deficiency of nutrition education and practice in cardiology. Am J Med. 2017;130(11):1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khandelwal S., Zemore S.E., Hemmerling A. Nutrition education in internal medicine residency programs and predictors of residents’ dietary counseling practices. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5 doi: 10.1177/2382120518763360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Daley B.J., Cherry-Bukowiec J., Van Way C.W., III, et al. Current status of nutrition training in graduate medical education from a survey of residency program directors: a formal nutrition education course is necessary. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(1):95–99. doi: 10.1177/0148607115571155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shafto K., Shah A., Smith J., et al. Impact of an online nutrition course to address a gap in medical education: a feasibility study. PRiMER. 2020;4:5. doi: 10.22454/PRiMER.2020.368659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Proceedings of the Summit on Medical Education in Nutrition Documenting three days of discussion. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/nutritionsummit/nutrition-summit-proceedings.pdf

- 77.Bremer A.A. Prioritizing nutrition in medical education-the time has come. Adv Nutr. 2024;15(6) doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2024.100231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wattanapisit A., Tuangratananon T., Thanamee S. Physical activity counseling in primary care and family medicine residency training: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1268-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hébert E.T., Caughy M.O., Shuval K. Primary care providers’ perceptions of physical activity counselling in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(9):625–631. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Antognoli E.L., Seeholzer E.L., Gullett H., Jackson B., Smith S., Flocke S.A. Primary care resident training for obesity, nutrition, and physical activity counseling: a mixed-methods study. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(5):672–680. doi: 10.1177/1524839916658025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goff S.L., Holboe E.S., Concato J. Pediatricians and physical activity counseling: how does residency prepare them for this task? Teach Learn Med. 2010;22(2):107–111. doi: 10.1080/10401331003656512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mindell J.A., Bartle A., Ahn Y., et al. Sleep education in pediatric residency programs: a cross-cultural look. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:130. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sullivan S.S., Cao M.T. Sleep medicine exposure offered by United States residency training programs. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(4):825–832. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gouveia C.J., Kern R.C., Liu S.Y.C., Capasso R. The state of academic sleep surgery: a survey of United States residency and fellowship programs. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(10):2423–2428. doi: 10.1002/lary.26572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gardiner P., Filippelli A.C., Lebensohn P., Bonakdar R. The incorporation of stress management programming into family medicine residencies-results of a national survey of residency directors: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2015;47(4):272–278. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25853597 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roberts M. Balint groups: a tool for personal and professional resilience. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):245–247. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22423015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ziegelstein R.C. Creating structured opportunities for social engagement to promote well-being and avoid burnout in medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):537–539. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pringle J.L., Kowalchuk A., Meyers J.A., Seale J.P. Equipping residents to address alcohol and drug abuse: the National SBIRT Residency Training Project. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):58–63. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00019.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seale J.P., Shellenberger S., Clark D.C. Providing competency-based family medicine residency training in substance abuse in the new millennium: a model curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liddle D.G., Changstrom B., Senter C., et al. Recommended musculoskeletal and sports medicine curriculum for internal medicine residency training. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2021;20(2):113–123. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thornton J., Khan K., Weiler R., Mackie C., Petrella R. Are family medicine residents trained to counsel patients on physical activity? The Canadian experience and a call to action. Postgrad Med J. 2023;99(1169):207–210. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hill L.L., Nichols J., Wing D., Waalen J., Friedman E. Training on Exercise is Medicine® within an integrative medicine curriculum. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(suppl 3):S278–S284. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.018. (5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams M.K., Estores I.M., Merlo L.J. Promoting resilience in medicine: the effects of a mind-body medicine elective to improve medical student well-being. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020;9 doi: 10.1177/2164956120927367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Richmond R., Zwar N., Taylor R., Hunnisett J., Hyslop F. Teaching about tobacco in medical schools: a worldwide study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(5):484–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Marshall K.F., Carney P.A., Bonuck K.J., Riquelme P., Robbins J. Preparing fourth year medical students to care for patients with opioid use disorder: how this training affects their intention to seek addiction care opportunities during residency. Med Educ Online. 2023;28(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2022.2141602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nims L., Jordan T.R., Price J.H., Dake J.A., Khubchandani J. Smoking cessation education and training in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs in the United States. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):1151–1158. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_451_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tong S., Sabo R., Aycock R., et al. Assessment of addiction medicine training in family medicine residency programs: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2017;49(7):537–543. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28724151 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ardekani A., Hosseini S.A., Tabari P., et al. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keifenheim K.E., Velten-Schurian K., Fahse B., et al. ‘A change would do you good’: training medical students in motivational interviewing using a blended-learning approach—a pilot evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(4):663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maini A., Fyfe M., Kumar S. Medical students as health coaches: adding value for patients and students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02096-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chan C.A., Windish D.M. A survey of motivational interviewing training experiences among internal medicine residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;112 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Childers J.W., Bost J.E., Kraemer K.L., et al. Giving residents tools to talk about behavior change: a motivational interviewing curriculum description and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(2):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Miller-Matero L.R., Tobin E.T., Fleagle E., Coleman J.P., Nair A. Motivating residents to change communication: the role of a brief motivational interviewing didactic. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e124. doi: 10.1017/S146342361900015X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lutchman K., Wan M., Lan F.Y., Kales S.N., Frates E.P. Integrating the lifestyle medicine residency curriculum into an occupational medicine training program. J Occup Environ Med. 2024;66(4):e143–e144. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000003056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rea B., Wilson A. Creating a lifestyle medicine specialist fellowship: a replicable and sustainable model. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(3):278–281. doi: 10.1177/1559827620907552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lianov L., Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA. 2010;304(2):202–203. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies NEJM Knowledge+. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/exploring-acgme-core-competencies/ (Part 1 of 7)

- 108.Albin J.L., Thomas O.W., Marvasti F.F., Reilly J.M. There and back again: a forty-year perspective on physician nutrition education. Adv Nutr. 2024;15(6) doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2024.100230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Clinician Educator Milestones Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/milestones/resources/clinician-educator-milestones/

- 110.Hashemzadeh M., Rahimi A., Zare-Farashbandi F., Alavi-Naeini A.M., Daei A. Transtheoretical model of health behavioral change: a systematic review. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24(2):83–90. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_94_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rippe J.M. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2019. Lifestyle Medicine.https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=z8ySDwAAQBAJ [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rippe J.M. Lifestyle Medicine. Book series. https://www.routledge.com/Lifestyle-Medicine/book-series/CRCLM

- 113.Frates B. Healthy Learning; 2019. Lifestyle Medicine Handbook: An Introduction to the Power of Healthy Habits.https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=pEIpwAEACAAJ [Google Scholar]

- 114.Frates B.C.D. Healthy Learning; 2023. The Lifestyle Medicine Pocket Guide.https://healthylearning.com/the-lifestyle-medicine-pocket-guide/ [Google Scholar]

- 115.Downes L., Tryon L. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2023. Health Promotion and Disease Prevention for Advanced Practice: Integrating Evidence-Based Lifestyle Concepts.https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=0FbgEAAAQBAJ [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sherson E.A., Yakes Jimenez E., Katalanos N. A review of the use of the 5 A’s model for weight loss counselling: differences between physician practice and patient demand. Fam Pract. 2014;31(4):389–398. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.ASA24® Dietary Assessment Tool. Australian Society of Anaesthetists. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/asa24/

- 118.24-hour dietary recall (24HR) at a glance. Dietary Assessment Primer. https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov/profiles/recall/

- 119.Physical activity vital sign Exercise is medicine. https://exerciseismedicine.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/EIM-Physical-Activity-Vital-Sign.pdf

- 120.Cohen S. Contrasting the Hassles Scale and the Perceived Stress Scale: who’s really measuring appraised stress? Am Psychol. 1986;41(6):716–718. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.6.716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F. 3.r.d., Monk T.H., Berman S.R., Kupfer D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]