Abstract

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people experience disparities in cancer care, including more late-stage diagnoses, worse cancer-related outcomes, and an increased number of unaddressed and more severe symptoms related to cancer and cancer-directed therapy. This article outlines plans to address the unique needs of TGD people through a TGD-focused oncology clinic. Such a clinic could be structured by upholding the following tenets: (1) champion a supportive, gender-affirming environment that seeks to continuously improve, (2) include a transdisciplinary team of specialists who are dedicated to TGD cancer care, and (3) initiate and embrace TGD-patient-centric research on health outcomes and health care delivery.

The Rationale for a Transgender and Gender Diverse-Focused Oncology Clinic

More than 1.4 million adults in the United States identify with a gender different from that assigned at birth—a number that exceeds the population of Dallas, Texas.1 These individuals encompass the gender identity spectrum: from transgender men who were assigned female sex at birth, to transgender women who were assigned male sex at birth, to nonbinary individuals who identify outside the male or female binary. This population is growing: approximately, 1.4% of youth aged 13-17 years (compared with 0.6% of adults) identify as Transgender and gender diverse (TGD).1 As these individuals are sometimes reluctant to disclose their identity or are not consistently asked about it, this number is likely an underestimate.2

Transgender and gender diverse individuals experience health care disparities. Over a quarter report postponing medical care due to past discrimination; half report having to teach their clinicians about their health care needs.3 To underscore the gravity of poor health care and minority stress, 40% of the TGD people report attempted suicide.3 The TGD people are more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages of cancer and are more likely to suffer poor outcomes—presumably as a result of delays and more advanced stage cancer at diagnosis—when compared with the general population.4, 5, 6, 7 For example, TGD patients have a 2-fold higher risk of death from non-Hodgkin lymphoma (hazard ratio [HR], 2.34; 95% CI, 1.06-3.45).5 Such disparities persist even after adjusting for health insurance status and after excluding individuals who declined cancer treatment.

Again, these statistics likely represent underreporting because TGD people are often invisible in oncology clinics. Patient surveys have not historically inquired about gender identity.8, 9, 10 For example, our data report that, in 2017, fewer than one-quarter of oncology practices nationwide were asking for patients’ gender identity information; this proportion improved in 2022, but still only 58% of practices nationwide reported collection of gender identity.2,11 Disclosing gender identity may compromise TGD individuals’ safety, and previous traumatic experiences within the health care system may result in no disclosure.8,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Furthermore, many oncology clinicians are not asking about gender identify, perhaps because they feel inadequately trained to do so.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 In addition, many datasets that collect gender identity have high rates of misclassification, and TGD individuals may not see themselves represented in standard discrete questionnaire response options for sex assigned at birth and gender identity (typically male, female, or transgender).9 For instance, a transgender man faces a conundrum of whether to report gender identity as male or transgender. Better methods to identify TGD people with cancer and to support their reporting needs are necessary.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Despite the growing cancer-specific needs of TGD people and despite the data that point to their being underserved, to our knowledge, no cancer clinics (or, at most, few) have been established in the United States. The TGD-focused cancer clinics could help improve cancer care for TGD people and generate research to improve TGD cancer care. This paper describes our institution’s vision and blueprint for such a cancer clinic for the TGD people whom we serve. Of note, a nascent version of this clinic has already begun to care for patients throughout the cancer continuum—from cancer diagnosis through survivorship and end-of-life care—at our institution. We provide this paper to provide evolving guidance to other institutions.

How Should a TGD-Focused Clinic be Staffed and Structured?

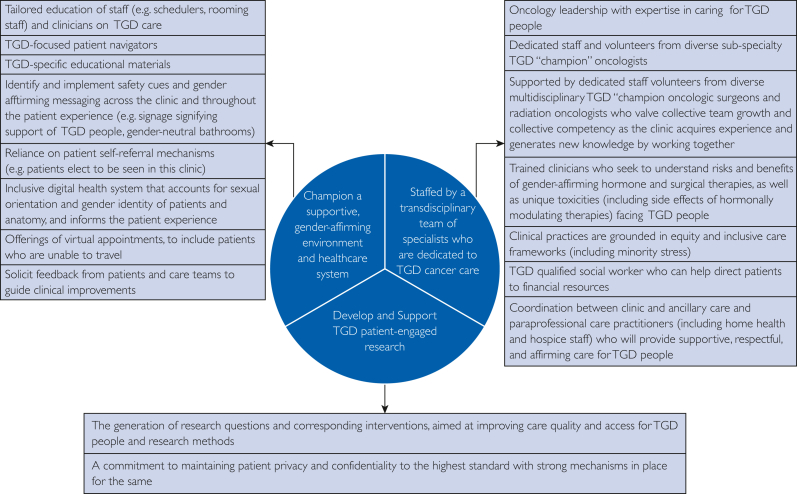

Three main tenets guide the development and structure of a TGD-focused cancer clinic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tenets and structure of an TGD-focused cancer clinic. TGD, transgender and gender diverse.

Tenet 1: Recruit Physician and Nurse Champions and Support These Health Care Providers’ Gender-Affirming Efforts

First, a TGD-specific oncology clinic should strive for a safe and supportive environment, which relies on the training of all clinic staff—from the appointment office to desk staff to medical assistants, nurses, and clinicians—on why and how to discuss gender identity in an affirming way; all staff need to have taken educational courses (institution-specific trainings—our group’s courses are currently in development, the COLORS training program, or courses through the Fenway Institute).29 Patient navigators who are aware and respectful of the needs of TGD individuals should be recruited and trained. The TGD-identifying people can serve as advocates who will work closely with patients and clinicians in this clinic. Every effort should be made to involve TGD individuals throughout the clinic, as staff or clinicians, and as advisors to practices.

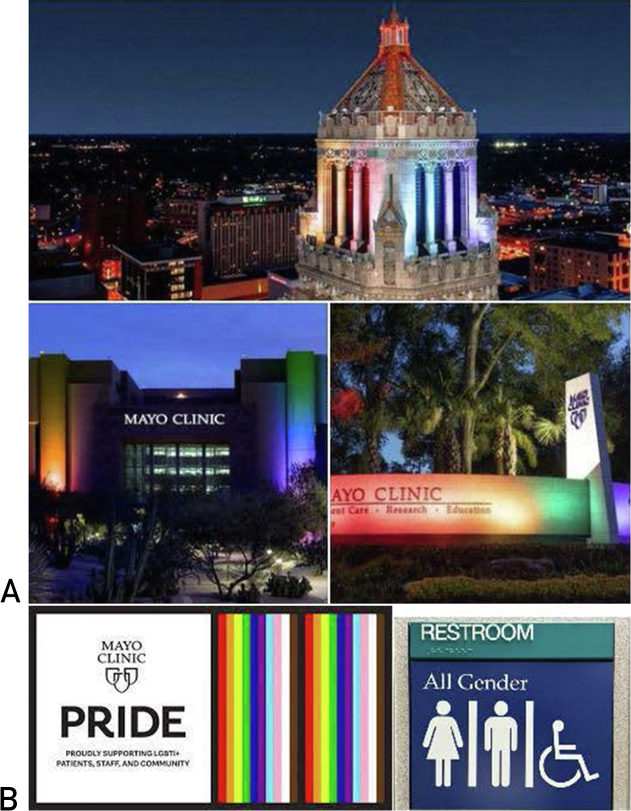

This environment should include safety cues, such as a signage of support of TGD people (transgender pride or progress pride flags are an example) and the presence of gender-neutral bathrooms, and well-publicized educational materials specific to TGD people; language and signage that tout gendered stereotypes (ie using terms such as women’s cancer) will be minimized (Figure 2). To further ensure TGD patient safety and confidentiality and to ensure patients are not outed in the medical record by referral to this clinic, patients should self-refer. Thus, all patients, as a part of the new oncology patient questionnaire, may be asked “Would you like to be cared for in the transgender and gender diverse cancer clinic?” TGD people should understand at the outset that this clinic was established with the express purpose of improving care (so that they are not made to feel unnecessarily focused on).29,30

Figure 2.

Mayo Clinic signage that signifies support for TGD individuals shows (A) Mayo Clinic buildings lit up in celebration of Pride month and (B) Mayo Clinic Pride logo and signage for gender-neutral bathrooms and other similar indicators will enable TGD patients to feel comfortable during their appointments. TGD, transgender and gender diverse.

This clinic should engage digital tools, including utilization of the electronic health record (EHR) and virtual visits. The EHR allows for patient self-identification of gender identity, and also an organ inventory, which informs the relevance of cancer diagnostics and treatment. The organ inventory will identify individuals who have undergone gonadectomy, in which fertility preservation discussions are not needed. For those who retain their ovaries, gonadectomy could be considered with an estrogen-driven cancer. For TGD people who have more limited resources or limited care options, virtual appointments may be important.3 In the ever-changing post-COVID world of insurance coverage, this may require clinicians to seek licensure in other states, particularly for individuals in regions with anti-TGD health care legislation.

From the time of this clinic’s inception throughout its implementation, TGD people will be asked for their input on ways this clinic could be improved, guiding an iterative process to spur advances and progress.

“Oncology is multidisciplinary, which means that the patient must trust every provider on their care team… The problem in oncology, really, is that it’s not as if you make a relationship with one open-minded oncology provider…If you’re coming into cancer for the very first time as a gay person or as a transgender person, you’re talking about the risks of meeting new people as you try to create your team. You face—How do I disclose? And what do I do if they don’t want to treat me?” Dr. Don Dizon, quoted in the Cancer Letter “SCOTUS Decision on Denying Service to LGBTQ+ People Opens Doors for Discrimination in Cancer Care.”

Tenet 2: Collaborate With Specialists Who Have Interest and Expertise in TGD Cancer Care

Although an oncologist with expertise in caring for TGD patients should lead the clinic, the subspecialized, multidisciplinary nature of cancer care calls for the support and expertise of a transdisciplinary team that engages clinicians across specialties and disciplines. For example, an informal query of the EHR, (consisting of a search by E.C.R. and A.J. for patients with a cancer diagnosis self-identifying as TGD in the EHR), found that numerous cancer types were represented among the consecutive TGD individuals with cancer, from genitourinary cancers to gastrointestinal cancers to rare cancer types such as Waldenstrom. The observation that no single malignancy manifested a predominant presence illustrates the fact that, in building such a clinic, its founders must rely on the vast expertise within a large tertiary or quaternary medical center. To do otherwise could limit the quality of care rendered to these patients. Furthermore, this comprehensive team of cancer care professionals should include staff who proactively decide to be involved in this clinic and are enthusiastic about undergoing TGD training developed by our group (or others). An authentic commitment from the staff to the health and well-being of TGD patients is essential to ensuring that health care professionals provide compassionate care to TGD individuals with cancer and to address their unique needs. Ideally, one or more volunteer oncology champions would represent each cancer type (ie, breast, lung, and gastrointestinal) and provide high-level, state-of-the-art cancer care. A multidisciplinary team (oncology operation and radiation oncology) would be comprised of other champions within each discipline.

For instance, our TGD-focused breast oncology care team, the core of this clinic, consists of individuals with expertise in providing care for TGD individuals and consists of 2 breast oncologists, an advanced practice provider (a nurse practitioner), and a nurse. The schedulers, those who room patients, and a social worker, all of whom support this clinic, all hold special interest and have voluntarily received training in working with this patient population; some are members of the TGD community. In addition to this core oncology clinical team, TGD-focused champions have been identified in breast radiology and in the internal medicine breast clinic (clinicians who have expertise in diagnosing breast or chest malignancy and in providing survivorship care), and in radiation oncology, operation, and plastic operation. Therefore, clinicians and staff who understand the complexities of TGD cancer care are providing culturally competent care from cancer screening through diagnosis, multidisciplinary cancer treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care.

Health care clinicians within this TGD clinic must recognize—but ultimately accept—that cancer care for TGD individuals might not always be perfectly aligned with the care that other non-TGD patients receive. Importantly, these staff must seek to understand the gravity of stopping gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT). For instance, one patient at our institution was diagnosed with a hormonally driven cancer but continued testosterone therapy. Per clinician notes, stopping his testosterone supplement “would clearly significantly negatively impact his quality of life,” a medical record quotation that underscores how the discontinuation of GAHT can threaten patients’ core identity and result in distress. Although cancer-directed therapies often require cessation of hormonal therapy that could be antagonistic with cancer therapy, stopping GAHT might not be the best decision, as derived from a compassionate and thoughtful educational discussion with the patient above. Of note, the effect of androgens as a part of GAHT on cancer development and cancer progression remains unknown.31, 32, 33, 34

In addition, cancer clinicians might need to increase their acceptance of providing invasive procedures to TGD individuals even when clinical trials suggest that a less invasive approach provides equivalent outcomes. This concept is not limited to transgender individuals; some surgical procedures may also compromise the gender identity of cisgender individuals.35 Another case of a transgender woman illustrates this point. This individual elected to pursue prostatectomy – rather than radiation therapy – as extirpation of the prostate seemed most concordant with her gender identity.

Other examples are gleaned from publications from our team and the work of Lisy et al,36 who qualitatively studied the cancer survivorship experiences of TGD people in Australia.37

A nonbinary person with localized breast cancer elected to pursue bilateral mastectomy without reconstruction, rather than a lumpectomy with radiation, as this decision was reflective of their gender identity. This decision was also reflected in qualitative interviews completed by Lisy et al36; one nonbinary person reported, postbilateral mastectomy “I really was what I always wanted to be, flat-chested, and I was really happy with the surgery.”

The TGD-focused oncology teams should be comfortable discussing the risks and benefits of local therapies, in the context of a patient’s gender identity. Of course, shared decision-making should discuss survival and recurrence but also how options might influence a person’s identity. The wishes of TGD patients should be heard, listened to, at times accommodated, and never assumed.

Furthermore, the cases described above in conjunction with previous research illustrate that TGD people experience adverse effects of cancer therapy in a manner that might not typify what other patients experience. Lisy et al36 captured comments from a TGD patient, “I can’t have sex. I spent years with gender dysphoria, not being happy with what was there, and then I get to the stage where I can finally fix that and then two years later I can’t use the thing, yes, I’m a little bit distressed about that” and “at no point had anyone ever said anything other than, ‘you might suffer some dryness’ so I was a little disappointed with that, not having been given the full story, not having that time to prepare for that mentally.” For TGD patients, a decline in libido can be multifactorial in nature, presumably related to stress from a cancer diagnosis, endocrine therapy, and low-testosterone levels, and palliated with a multifaceted approach. Hence, symptom palliation for TGD patients might be complex.

Discussions of fertility preservation are also often overlooked in TGD people; according to OUT: The National Cancer Survey, conducted by the National LGBT Cancer Network, 82% of sexual and gender minority cancer survivors reported that their oncology team did not discuss how to support plans for future fertility.38 However, many TGD individuals hope to be parents, should be offered a discussion about fertility preservation, and should be referred to fertility specialists who focus on TGD individuals. Similarly, TGD individuals might experience financial toxicity more acutely. Because of previous discrimination, a TGD person’s financial situation might be strained. Patients might have had problems gaining employment and acquiring health insurance. Along similar lines, a TGD person’s social support network might be limited and consist of friendships as opposed to family ties. A TGD person with cancer might identify a friend – rather than a genetic family member – as a medical decision-maker. A TGD-focused oncology team should inquire about, discuss, and address such potential issues proactively and garner help and advice from other members of the health care team, such as a social worker, with insights into community-based TGD resources and with knowledge of how to garner resources. Social workers may also help patients with financial issues and transportation challenges that might impede cancer treatment. They can also provide counseling to individuals in distress after such a cancer diagnosis and help patients navigate to medical appointments. Even community-based TGD-specific social resources (for instance, TGD pool nights or yoga) should be shared with patients. The TGD clinic team should also coordinate care with ancillary care practitioners, particularly those who provide home-based services, such as home health and hospice, and those who will treat TGD people with respect and affirm their identities. It is important that TGD people are safely cared for in their homes, particularly during such vulnerable and difficult times as occur with a cancer diagnosis.

Tenet 3: Develop and Support Patient-Engaged Research

What we learn from each patient should be cataloged – confidentially – with the goal of helping the next patient. This clinic’s research should align with recommendations for conducting clinical trials, which are inclusive of and affirming for TGD people, as published by a Mayo Clinic multidisciplinary team.39 For instance, research will integrate community engagement to improve participant recruitment, enhance informed consent processes that emphasize participant safety protections, and use data collection forms and survey items that contain gender-affirming language.

Currently, a paucity of data is available. As a case in point, although Mayo Clinic has solicited gender identity from every new oncology patient using a standard questionnaire, consistent with National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommendations, since 2017, based on 12 patients who emerged from a medical record review, the number of TGD patients with cancer at Mayo Clinic is lower than one might expect: 0.6% of adults in the United States identify as transgender and gender diverse;100,000 patients are seen with cancer diagnoses at Mayo Clinic annually; cancer incidence does not appear different among TGD people than cisgender people – thus, we would have expected perhaps a couple of hundred TGD patients with cancer – not 12.40, 41, 42 This low number is not unique to Mayo Clinic. At the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, during a presentation devoted to caring for TGD people at high risk of cancer, most participants (58.4%) reported seeing fewer than 5 TGD people per year (note that this is among people interested enough in the topic to attend such a session).43 Such limited data underscore the need to conduct respectful and confidential, patient-oriented research.

Although research reports that TGD patients experience poorer cancer outcomes, issues remain unaddressed. To date, the reasons behind delayed diagnosis or poor prognosis, the best way to administer cancer-directed therapies in the setting of gender-affirming therapy in hormonally driven cancers, how to dose chemotherapy (and calculate kidney function) in patients undergoing GAHT, and how to address therapy adverse effects or gender-affirming therapies – warrant investigation. A TGD-focused clinic is ideally placed in a health care setting where clinical and translational researchers provide expertise to investigate pressing clinical issues. For instance, a prospective study of TGD individuals with hormonally driven cancers would help to identify the safety and efficacy of different types of endocrine therapy in the setting of GAHT. Such a study would consist of evaluations of tumor specimens to better understand interactions between GAHT and endocrine therapy. Such research might also investigate patient-reported outcomes that pertain to how endocrine therapy might influence gender identity and expression of identity. Although sample sizes might be small, such research—including qualitative research that often requires relatively small sample sizes—is imperative to driving up quality of care in these underserved groups of patients.

Finally, the clinic—and, of course, the research—should be advertised online, such as through social media (and within internal and external clinics), to reach the largest patient catchment. An online presence will allow for inclusivity, help patients who have not sought cancer care due to previous discrimination, and explain the need for research. The internet and social media are sources of information for TGD individuals, and Rosser et al44 have confirmed that even older sexual minority patients prefer contact online for health care research.45,46 An online presence will likely enable TGD individuals with cancer to know of the resources available. Integrating educational materials on social media allows patients to ponder research participation prior and to be prepared to accept or decline.

Practical Considerations

This paper highlights the structure of a TGD-focused cancer clinic at a quaternary medical center in the Midwest with an awareness of limitations. Virtual visits and multistate licensure of clinicians may help counter access barriers, but obstacles such as limited insurance coverage might still come into play. Social media as an educational platform offers information to TGD patients who are unable to travel or make use of virtual visits.3 Advocacy for the rights of TGD individuals – throughout the health care systems and within every level of government will ultimately change the tide of discrimination, allow for improvements in cancer care and cancer-related outcomes, and make the acquisition of cancer care easier.

“We are not our best intentions. We are what we do.47” This quotation encapsulates our rationale for being deliberate and methodical in planning a TGD-focused cancer clinic. Such clinics are needed to help identify and address the disparities that face TGD individuals who are diagnosed with cancer, to provide excellent oncologic care in a safe and inclusive environment, and to promote TGD-specific community-engaged research. Such a clinic should involve sub-specialists from multiple oncologic disciplines and make efforts to engage all patients who identify as TGD and have cancer. However, for the times we misstep, we hope that a prompt apology, a genuine realization of the consequences, a recognition of an opportunity to learn, and a steadfast commitment to TGD individuals with cancer will improve and sustain our efforts over time.

Potential Competing Interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This article was supported by the following grant numbers: K12AR084222 and K07AG076401 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Herman J.L., Flores A.R., O'Neill K.K. The Williams Institute; 2022. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cathcart-Rake E.J., Jatoi A., Dressler E.V.M., et al. Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection among NCI community oncology research program (NCORP) practices: A 5-year landscape update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.6548. 6548-6548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant J., Mottet L., Tanis J., et al. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns Z.T., Bitterman D.S., Perni S., et al. Clinical characteristics, experiences, and outcomes of transgender patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1) doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson S.S., Han X., Mao Z., et al. Cancer stage, treatment, and survival among transgender patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(9):1221–1227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn G.P., Sanchez J.A., Sutton S.K., et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):384–400. doi: 10.3322/caac.21288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown G.R., Jones K.T. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191–198. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKay T., Watson R.J. Gender expansive youth disclosure and mental health: clinical implications of gender identity disclosure. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2020;7(1):66–75. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tordoff D., Andrasik M., Hajat A. Misclassification of sex assigned at birth in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and transgender reproductive health: a quantitative bias analysis. Epidemiology. 2019;30(5):669–678. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cicero E.C., Reisner S.L., Merwin E.I., Humphreys J.C., Silva S.G. Application of behavioral risk factor surveillance system sampling weights to transgender health measurement. Nurs Res. 2020;69(4):307–315. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cathcart-Rake E.J., Zemla T., Jatoi A., et al. Acquisition of sexual orientation and gender identity data among NCI Community Oncology Research Program practice groups. Cancer. 2019;125(8):1313–1318. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamen C.S., Smith-Stoner M., Heckler C.E., Flannery M., Margolies L. Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(1):44–51. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.44-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn G.P., Schabath M.B., Sanchez J.A., Sutton S.K., Green B.L. The importance of disclosure: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, queer/questioning, and intersex individuals and the cancer continuum. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1160–1163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossman K., Salamanca P., Macapagal K. A qualitative study examining young adults' experiences of disclosure and nondisclosure of LGBTQ identity to health care providers. J Homosex. 2017;64(10):1390–1410. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suen L.W., Lunn M.R., Sevelius J.M., et al. Do ask, tell, and show: contextual factors affecting sexual orientation and gender identity disclosure for sexual and gender minority people. LGBT Health. 2022;9(2):73–80. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson H.M. Patient perspectives on gender identity data collection in electronic health records: an analysis of disclosure, privacy, and access to care. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):205–215. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haider A.H., Schneider E.B., Kodadek L.M., et al. Emergency department query for patient-centered approaches to sexual orientation and gender identity: the EQUALITY study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):819–828. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maragh-Bass A.C., Torain M., Adler R., et al. Is it okay to ask: transgender patient perspectives on sexual orientation and gender identity collection in healthcare. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(6):655–667. doi: 10.1111/acem.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maragh-Bass A.C., Torain M., Adler R., et al. Risks, benefits, and importance of collecting sexual orientation and gender identity data in healthcare settings: a multi-method analysis of patient and provider perspectives. LGBT Health. 2017;4(2):141–152. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haider A., Adler R.R., Schneider E., et al. Assessment of patient-centered approaches to collect sexual orientation and gender identity information in the emergency department: the EQUALITY study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cathcart-Rake E., O'Connor J.M., Ridgeway J.L., et al. Querying patients with cancer about sexual health and sexual and gender minority status: a qualitative study of health-care providers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(6):418–423. doi: 10.1177/1049909119879129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cathcart-Rake E., O'Connor J., Ridgeway J.L., et al. Patients' perspectives and advice on how to discuss sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual health in oncology clinics. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(12):1053–1061. doi: 10.1177/1049909120910084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griggs J., Maingi S., Blinder V., et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2203–2208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon S. Breaking Down Health Care Barriers for LGBT Community. American Cancer Society Web site. Published 2018. Accessed May 10, 2022, 2022.

- 25.Olsen K. AACR conference examines cancer disparities in the LGBTQ population. American Association for Cancer Research. Accessed May 10, 2022.

- 26.National Institutes of health releases report on . National LGBTQ Task Force; 2022. LGBT Health. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuehn B.M. IOM: data on health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons needed. JAMA. 2011;305(19):1950–1951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamen C.S., Dizon D.S., Fung C., et al. State of cancer care in America: achieving cancer health equity among sexual and gender minority communities. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(11):959–966. doi: 10.1200/OP.23.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seay J., Hicks A., Markham M.J., et al. Developing a web-based LGBT cultural competency training for oncologists: the COLORS training. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):984–989. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seay J., Hicks A., Markham M.J., et al. Web-based LGBT cultural competency training intervention for oncologists: pilot study results. Cancer. 2020;126(1):112–120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurrala R.R., Kumar T., Yoo A., Mundinger G.S., Womac D.J., Lau F.H. The impact of exogenous testosterone on breast cancer risk in transmasculine individuals. Ann Plast Surg. 2023;90(1):96–105. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker G.M., Guzman-Arocho Y.D., Bret-Mounet V.C., et al. Testosterone therapy and breast histopathological features in transgender individuals. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(1):85–94. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00675-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan K.J., Jolly D., Liang J.J., Weinand J.D., Safer J.D. Estrogen levels do not rise with testosterone treatment for transgender Men. Endocr Pract. 2018;24(4):329–333. doi: 10.4158/EP-2017-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappas I.I., Craig W.Y., Spratt L.V., Spratt D.I. Efficacy of sex steroid therapy without progestin or GnRH agonist for gonadal suppression in adult transgender patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e1290–e1300. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piot-Ziegler C., Sassi M.L., Raffoul W., Delaloye J.F. Mastectomy, body deconstruction, and impact on identity: a qualitative study. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):479–510. doi: 10.1348/135910709X472174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lisy K., Kerr L., Jefford M., Fisher C. Everything's a fight: A qualitative study of the cancer survivorship experiences of transgender and gender diverse Australians. Cancer Med. 2023;12(11):12739–12748. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cathcart-Rake E.J., Kling J.M., Carroll E.F., et al. Understanding disparities: a case illustrative of the struggles facing transgender and gender diverse patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(2):227–230. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.7005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scout N., Rhoten B. National LGBT Cancer Network; 2021. OUT: the National cancer survey, summary of findings.http://cancer-network.org/out-the-national-cancer-survey [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kacel E.L., Pankey T.L., Vencill J.A.J., et al. Include, Affirm, and Empower: A paradigm shift in cancer clinical trials for sexual and gender diverse populations. Annals LGBTQ Public Popul Health. 2022;3(1):18–40. doi: 10.1891/LGBTQ-2021-0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asscheman H., Giltay E.J., Megens J.A., de Ronde W.P., van Trotsenburg M.A.A., Gooren L.J.G. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):635–642. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Blok C.J.M., Wiepjes C.M., Nota N.M., et al. Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2019;365 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Blok C.J.M., Dreijerink K.M.A., den Heijer M. Cancer risk in transgender people. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019;48(2):441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel S. Paper presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL: June 4, 2023. Managing cancer risk in transgender patients with inherited cancer predisposition. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosser B.R.S., Capistrant B. Online versus telephone methods to recruit and interview older gay and bisexual men treated for prostate cancer: findings from the restore study. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(2) doi: 10.2196/cancer.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safer J. I'm Joshua Safer, Medical Director at the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Boston University Medical Center, here to talk about the science behind transgender medicine. Transgender Health AMA Series: Reddit. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howe A., Anderson J. Involving patients in medical education. BMJ. 2003;327(7410):326–328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7410.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dickinson A. AZQuotes.com. Wind and Fly LTD. 2024 https://www.azquotes.com/author/65647-Amy_Dickinson [Google Scholar]