Abstract

There is a gap in whether relationship power affects the association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships. Based on the relationship maintenance model and the social distance theory of power, the present study adopted a digital questionnaire design on an online platform to test the mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness between gratitude and satisfaction as well as the moderating role of relationship power. A total of 825 subjects (Mage = 27.2, SD = 10.6; female 46.9%) who had been in romantic relationships for more than six months participated in this study. Overall, the results of the moderator–mediator model indicated that, compared to individuals with low levels of relationship power, the relationship between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness as well as that between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction was weaker among those with high levels of power. These findings are revealing for interventions designed to promote satisfaction between couples with power imbalances.

Keywords: Gratitude, Perceived partner responsiveness, Relationship power, Relationship satisfaction, Romantic relationships

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Romantic relationships have a significant impact on our physical and mental health1. However, poor romantic relationships are not only associated with unhealthy mental states such as depressed mood but even with psychiatric disorders2, posing health risks3. Therefore, the quality of intimate relationships is vital, and romantic relationship satisfaction is a powerful indicator of it4. Understanding the factors that influence relationship satisfaction is crucial for fostering healthy individual and romantic relationships. Previous research has demonstrated that gratitude5, relationship power6, and perceived partner responsiveness7 significantly impact everyday intimacy. However, the interplay and combined influence of these factors on relationship satisfaction remains unclear. Therefore, this study aims to address this research gap by exploring the complex relationships among these variables. We have constructed an integrative model that includes gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, relationship power, and relationship satisfaction. To ensure the generalizability of our findings, we utilized a questionnaire administered across a diverse sample of age groups. The following sections of the paper will describe the relationships between these variables in detail.

Gratitude and relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships

Gratitude is a stable affective trait, not only a feeling of gratitude that arises following help from others but also a habitual focus on and appreciating the positive aspects of life8. Gratitude can improve one's mental health9, and individuals who experience more gratitude report more positive emotions, greater well-being, and exhibit more prosocial behaviors10, and forge high-quality relationships11. Notably, gratitude is paramount to the successful maintenance of romantic relationships12. The broaden-and-build theory proposes that gratitude builds people’s skills for loving and showing appreciation, makes it easier for individuals to feel kindness from others, builds enduring interpersonal resources, and strengthens interpersonal romantic relationships13. A grateful disposition predicts the grateful mood of oneself and one’s spouse, which in turn predicts relationship satisfaction14. Other research has found that the escalation of daily gratitude in romantic relationships, both through self-behavior and the observation of partner behavior, is associated with a higher level of romantic relationship satisfaction15. Romantic relationship satisfaction refers to individuals' global subjective assessment of their romantic relationships with their couples16,17.

Recent research found that relationship power is the ability of one individual in a relationship to extend influence on another person, as evidenced by the individual's ability or potential to control the partner's thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, as well as to be free from the partner's influence18,19, can influence gratitude, e.g., individuals with low relationship power express and feel more gratitude20, especially in employment relationships21 and intergroup contexts22. However, no research has shown whether relationship power affects the positive prediction of gratitude for relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships.

The relationship maintenance model proposed by Gordon et al.12 integrates gratitude and risk regulation to elucidate how gratitude contributes to sustaining relationships. Key findings reveal that individuals who feel gratitude from their partners tend to reciprocate, enhancing both responsiveness and commitment. This mutual gratitude fosters relationship maintenance through supportive behaviors and long-term commitment. Additionally, the social distance theory of power by Magee and Smith23 posits that power creates asymmetric social distance, with high-power individuals feeling more independent and distant, while low-power individuals are more dependent on partner responsiveness. This theory elucidates the moderating role of power in relationship satisfaction, indicating that power dynamics influence the effects of gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness on relationship satisfaction. By integrating these theories, the present study proposes a mediated moderation model to investigate the mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness and the moderating role of relationship power in the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships. The complex interactions among these variables are examined below.

Gratitude and relationship satisfaction: the mediating effect of perceived partner responsiveness

Perceived partner responsiveness (PPR), refers to the extent to which individuals believe their partners are attentively and positively responding to them24, and includes three key ways in which a partner is perceived as supportive25 : (1) understanding (perception of the expresser’s core self, needs), (2) validation (respect for the expresser’s point of view), and/or (3) caring (integral warmth and affection from the responder to the expresser)26. Perceiving the partner's responsiveness to one's needs and desires is at the heart of intimacy12. According to the relationship maintenance model, feeling gratitude for one’s partner predicts greater responsiveness, which in turn increases their desire to maintain their relationships12. This model suggests that individuals with high trait gratitude may be positively associated with high perceived partner responsiveness among couples, which in turn could be related to higher relationship satisfaction. Therefore, the PPR is likely to be a mediating mechanism between gratitude and relationship satisfaction.

From the perspective of the relationship maintenance model, individuals who are more appreciative of their partners report being more responsive to their partners' needs 12. Cross-sectional studies have revealed that gratitude is positively related to perceived partner responsiveness27,28. In a behavioral task paradigm experiment, participants were asked to express gratitude towards their partners and measure the target’s perceptions of the expresser’s responsiveness, found that between members of romantic relationships, the target had greater perceptions of the expresser's responsiveness after gratitude interaction11. The experiment demonstrated that participants who perceived their partners as more responsive when expressing gratitude in the lab had more intimate experiences in the future29. A longitudinal study among married couples found that a high level of perceived partner responsiveness promotes more gratitude feelings, which in turn promotes increased perceived partner responsiveness30.

The relationship maintenance model also states that partners’ responsiveness is related to the relationship maintenance12. This implies that perceived partner responsiveness is related to relationship satisfaction31. Perceived responsiveness is a fundamental element in facilitating the development of intimate relationships32, predicting not only one's intimacy but also that of the partner33. High levels of perceived partner responsiveness can foster more positive sacrifice appraisals as a result of increased closeness and reduced adverse effects toward the partner34. Perceived partner responsiveness is an integral part of intimacy development35 and is critical to relationship satisfaction36. Consistent with this, lower perceived partner responsiveness predicted declines in relationship satisfaction37. Furthermore, researchers demonstrated that perceived partner responsiveness, particularly after the partner has expressed his/her gratitude, will promote a range of outcomes including relationship satisfaction38. However, no research has directly tested the mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness in the association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. Thus, one aim of the present study is to examine whether perceived partner responsiveness mediates the link between gratitude and relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships from the relationship maintenance model’s perspective12.

Gratitude and relationship satisfaction: the moderating effect of relationship power

According to the social distance theory of power23, asymmetric dependence that characterizes power relationships produces asymmetric social distance, with relatively low-power individuals showing more attention and reaction to the behaviors and characteristics of their interaction partners, whereas high-power individuals will not. The find-mind-and-bond theory states that gratitude promotes relationship formation, the judgment of existing relationships, and the maintenance of existing relationships39. The perception of interpersonal warmth (e.g., friendliness, thoughtfulness) is the mechanism by which gratitude expressions can sustain such bonds40. It suggests that relationship power may attenuate the positive predictive effect of gratitude on responsiveness between partners as well as intimacy. Therefore, in the present study, we anticipated that relationship power may modulate the relationship between gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, and relationship satisfaction in romantic relationships.

Although couples in romantic relationships are increasingly desiring equal relationships, the cultural models of mutual support are not well developed41. The imbalance of relationship power incentivizes low-powered individuals to express more gratitude toward high-powered individuals for instrumental purposes42,43. Low-powered individuals can thereby fulfill the expectation of being rewarded with more positive experiences20. Whereas high-power individuals have less interest and concern for others and less commitment to maintain romantic relationships41. The complementary view suggests that gratitude arises from individuals perceiving that they are receiving greater benefits than they have a right to expect44, whereas higher-power individuals expect more benefits from others and do not perceive receiving more benefits than they are entitled to and therefore may be less to express and feel gratitude20 and not reap additional positive emotions45. However, previous research has not examined whether relational power attenuates the role of a positively predictive association between gratitude and closeness. We hypothesize that relationship power may attenuate the strength of the positive correlation between gratitude and relationship satisfaction among intimate partners.

Individuals with lower relationship power tend to adapt to their partner and respond rapidly46, whereas individuals with higher power may ignore their partners’ responses because of their high value47. Power even provides a reason to doubt the purity of others' favors, creating a cynical perspective on others' generosity that undermines relationships48. Individuals who successfully maintain intimacy and counteract imbalances of power tend to be more responsive to each other's behaviors41. It seems that relationship power may be able to influence the relationship between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness. Therefore, the present study hypothesizes that relationship power may attenuate the positive correlation between gratitude and perceived partners’ responsiveness. In addition, relationship power may be a potentially important moderator between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction. Individuals with lower power might perceive and respond to their partners' emotional expressions, more accurately and experience more negative emotions, whereas individuals with higher power might perceive and respond less to their partners’ emotional expressions but experience more positive emotions49. Additionally, it has been found that individuals with low relationship power in couples generated more positive responses to regain power and thus fulfilled their relational needs, such as support50. Whereas individuals with higher power are less willing to support their partners and do not value their partner's supportive responses48,51. The present study hypothesizes that relationship power plays a moderating role in the relationship between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction.

Current study

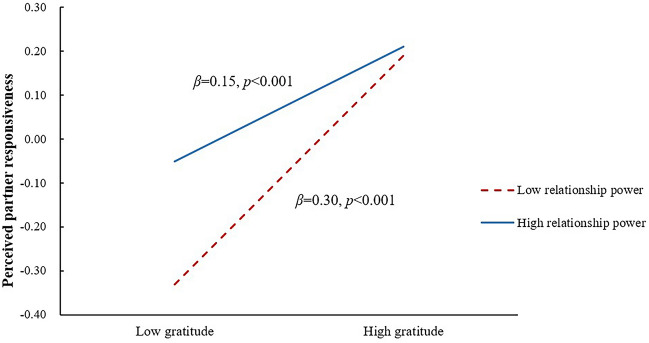

Given the above, no research has indicated whether and how the positive association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction was attenuated by relationship power, to create a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction among intimate partners, this study created a mediated moderation model to investigate the relationship among gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, relationship power, and relationship satisfaction (See Fig. 1). The specific aims of this study were to examine (1) the mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness, and (2) the moderating role of relationship power among gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, and relationship satisfaction. We formulated the following hypotheses: (a) Perceived partner responsiveness may be a potential mediator of the link between interpersonal gratitude and relationship satisfaction among couples; (b) Relationship power may attenuate the direct association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction among intimate couples; (c) Relationship power may attenuate the association between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness among couples; (d) Relationship power may attenuate the association between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction among couples.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

Method

Participants

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our findings, we conducted a priori sample size calculation using G*Power 3.1 software52. Following Cohen's53 recommendations for effect size, we aimed for a power (1-β) of 0.95, an alpha level of 0.05, and an anticipated medium effect size (f2 = 0.15). According to these parameters and previous studies54, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 119 participants. For this study, we recruited participants who have been in a romantic relationship for more than 6 months55 through school bulletin boards, social media sites, and other online platforms for one month. In return for participating in the study, participants were paid 5 RMB after finishing the questionnaires. After excluding 87 participants for invalid answers or age less than 18 years old. A total of 825 samples were included (438 male and 387 female, Mage = 27.2 years, SD age = 10.6). This sample size ensures that our study is adequately powered to detect significant effects and minimizes the risk of Type II errors. Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of samples.

| Variable | Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 27.2 ± 10.6 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 438 (53.1%) |

| Female | 387 (46.9%) |

| Residence | |

| Towns | 629 (76.2%) |

| Rural | 196 (23.8%) |

| Literacy | |

| Junior high school and below | 43 (5.2%) |

| High School | 99 (12.0%) |

| Associate | 404 (49.0%) |

| Bachelor | 250 (30.3%) |

| Graduate student and above | 29 (3.5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 250 (30.3%) |

| Unmarried | 574 (69.6%) |

Associate refers to participants who have completed a two-year college program, while 'Bachelor' refers to participants who have completed a four-year university program.

This study was conducted following the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before the start of the experiment. The study protocol was approved by the University Committee on Human Research Protection of East China Normal University (HR2-0161–2023).

Materials

Gratitude questionnaire

The Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) assessed the frequency and intensity of an individual's experience of gratitude, as well as individual differences in the trait of gratitude through the density and extensiveness of gratitude-inducing events56. This study was measured using its revised Chinese version57. It contains 6 items, such as “I feel thankful for what I have received in life” and "I feel grateful to many different persons", where questions 3 and 6 are reverse scored. Each item is scored using a Likert-7-point scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher mean scores indicating a greater propensity for gratitude in that individual. The α coefficient of the full scale was 0.81, and the split-half reliability was 0.82. The Cronbach’s alpha of this questionnaire was 0.75 in the present study.

Perceived partner responsiveness scale

The 12-item version of items Perceived Partner Responsiveness Scale (PPRS) was designed to measure the degree to which people feel that their relationship partners are responsive to them58. We used the Chinese adaptation of this scale, which has been validated in previous research59, showing an α coefficient of 0.90. The scale consists of general items e.g. “My couple is responsive to my needs”, comprehension items e.g. “My couple is on ‘the same wavelength’ with me” and validation items e.g. “My couple esteems me, shortcomings and all”60 on a 7-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (completely true), mean scores were calculated for all items, with higher scores indicating that the individual perceived his/her partner as more responsive to him/her. In the current present, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Relationship power scale

The Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS) was created by Pulerwitz et al.61. This study used the modified Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS-M) which removed four particular items about consistent condom use. In a total of 19 questions with two subscales, Relationship Control (12 items) and Decision-Making Dominance (7 items), a higher mean score was associated with higher relationship power. The relationship control subscale presented a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly Agree to 4 = Strongly Disagree, such as “Most of the time, we do what my partner wants to do”. The decision-making dominance subscale provided three answer choices: 1 = Your Partner, 2 = Both of You Equally, or 3 = You, such as “Who usually has more say about whose friends to go out with”. The modified scale maintains a good internal consistency reliability (α = 0.85). The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.83 in this study.

Relationship satisfaction index

The Quality of Relationship Index (QRI) was constructed by Patrick and Knee62. It consists of six items that assess the extent to which individuals are satisfied and happy with their relationship (e.g., “My relationship with my partner makes me happy”). Scores 1 (not at all true) to 7 (completely true), Items are averaged such that higher scores reflect higher relationship satisfaction. Internal reliability ranged from 0.85 to 0.94. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Analysis process

SPSS 24.0 was used for descriptive statistics, tests of variance, and correlation analysis of the data. The mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness between gratitude and relationship satisfaction was examined using Model 4 (which is a simple mediation model) of the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes63. Model 59 (which assumes the three paths of the simple mediation model, containing direct paths subject to moderation) was used to examine the moderating role of relationship power among the relationships of gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, and relationship satisfaction. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Common method biases

The Harman one-factor test was conducted to control this problem of common method bias (CMV) before data analysis, and the results showed that the amount of variance explained by the first factor was 25.86%, which is below the threshold of 40%. Therefore, the data obtained in this study were not affected by serious problems related to common method bias.

Preliminary analyses

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, relationship power, and relationship satisfaction. The results of correlation analysis showed that gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, relationship power, and relationship satisfaction were positively related to each other.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of all variables.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gratitude | 5.43 | 0.88 | – | |||

| 2. Perceived partner responsiveness | 4.26 | 0.66 | 0.32*** | – | ||

| 3. Relationship power | 2.56 | 0.39 | 0.11** | 0.16*** | – | |

| 4. Relationship satisfaction | 6.09 | 1.00 | 0.38*** | 0.63*** | 0.12** | – |

N = 825. M = mean. SD = standard deviations. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The mediating role of PPR between gratitude and relationship satisfaction

The mediating effect of perceived partner responsiveness between gratitude and relationship satisfaction was examined after controlling for the variables of gender, age, residence, literacy, marital status, and intimacy duration. As shown in Table 3, gratitude was found to be positively related to relationship satisfaction (β = 0.43, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.36, 0.05]), and when the mediating variable was added, gratitude also predicted relationship satisfaction positively (β = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.16, 0.29]). Perceived partner responsiveness was also positively related to relationship satisfaction (β = 0.87, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.78, 0.95]). The direct positive link between gratitude and relationship satisfaction (β = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95%CI = [0.16, 0.29]) and the indirect positive link between gratitude and relationship satisfaction via perceived partner responsiveness were both significant (β = 0.20, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.14]). Therefore, perceived partner responsiveness may serve as a partial mediation in the link between gratitude and relationship satisfaction.

Table 3.

Mediation model test for perceived partner responsiveness.

| Curve fitting Index | Significance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Predictors | R2 | F | β | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.16 | 22.34 | ||||||

| Gender | − 0.15 | − 2.33 | 0.02 | [− 0.28, − 0.02] | ||||

| Age | − 0.14 | − 1.82 | 0.07 | [− 0.03, 0.00] | ||||

| Intimacy duration | 0.02 | 1.82 | 0.07 | [− 0.00, 0.03] | ||||

| Marital status | − 0.13 | − 0.83 | 0.41 | [− 0.43, 0.17] | ||||

| Literacy | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.88 | [− 0.08, 0.09] | ||||

| Residence | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.81 | [− 0.13, 0.17] | ||||

| Gratitude | 0.43 | 11.62 | 0.00 | [0.36, 0.50] | ||||

| Perceived partner responsiveness | 0.13 | 18.52 | ||||||

| Gender | − 0.03 | − 0.61 | 0.54 | [− 0.11, 0.06] | ||||

| Age | − 0.01 | − 1.51 | 0.13 | [− 0.02, 0.00] | ||||

| Intimacy duration | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.65 | [− 0.01, 0,01] | ||||

| Marital status | − 0.16 | − 1.53 | 0.13 | [− 0.36, 0.04] | ||||

| Literacy | − 0.03 | − 0.92 | 0.36 | [− 0.08, 0.03] | ||||

| Residence | 0.09 | 1.66 | 0.09 | [− 0.02, 0.19] | ||||

| Gratitude | 0.23 | 9.52 | 0.00 | [0.19, 0.28] | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.44 | 80.94 | ||||||

| Gender | − 0.13 | − 2.43 | 0.02 | [− 0.23, − 0.03] | ||||

| Age | − 0.01 | − 1.16 | 0.25 | [− 0.02, 0.00] | ||||

| Intimacy duration | 0.01 | 1.90 | 0.06 | [0.00, 0.03] | ||||

| Marital status | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.94 | [− 0.24, 0.25] | ||||

| Literacy | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.40 | [− 0.04, 0.10] | ||||

| Residence | − 0.06 | − 0.89 | 0.37 | [− 0.18, 0.07] | ||||

| Gratitude | 0.22 | 7.10 | 0.00 | [0.16, 0.29] | ||||

| PPR | 0.87 | 20.31 | 0.00 | [0.78, 0.95] | ||||

'PPR' refers to Perceived Partner Responsiveness. N = 825. LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The moderating role of relationship power among gratitude, PPR, and relationship satisfaction

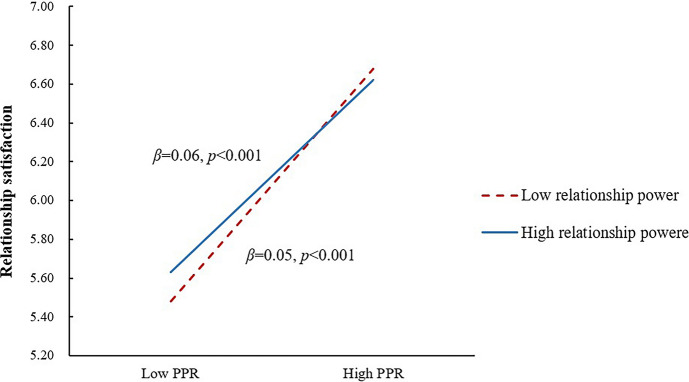

This study used Model 59 from the Process to verify the moderating effect of relationship power. As shown in Table 4, relationship power attenuated the positive relation between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness (β = -0.19, p < 0.01). Compared to individuals with low levels of relationship power (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), the positive association between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness was weaker among individuals with high relationship power (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), as can be seen in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Moderated mediation model test.

| Curve fitting Index | Significance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Predictors | R2 | F | β | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Perceived partner responsiveness | 0.16 | 17.43 | ||||||

| Gender | − 0.07 | − 1.51 | 0.13 | [− 0.16, 0.02] | ||||

| Age | − 0.01 | − 1.47 | 0.14 | [− 0.02, 0.00] | ||||

| Intimacy duration | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.87 | [− 0.01, 0.01] | ||||

| Marital status | − 0.12 | − 1.16 | 0.24 | [− 0.32, 0.08] | ||||

| Literacy | − 0.03 | − 0.96 | 0.34 | [− 0.08, 0.03] | ||||

| Residence | 0.08 | 1.64 | 0.10 | [− 0.02, 0.18] | ||||

| Gratitude | 0.22 | 4.69 | 0.00 | [0.17, 0.27] | ||||

| RP | 0.19 | 3.84 | 0.00 | [0.07, 0.30] | ||||

| Gratitude x RP | − 0.19 | − 3.23 | 0.00 | [− 0.03, − 0.07] | ||||

| Relationship Satisfaction | 0.45 | 59.81 | ||||||

| Gender | − 0.14 | − 2.60 | 0.01 | [− 0.25, − 0.04] | ||||

| Age | − 0.01 | − 1.12 | 0.26 | [− 0.02, 0.01] | ||||

| Intimacy duration | 0.01 | 1.75 | 0.08 | [− 0.00, 0.03] | ||||

| Marital status | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.94 | [− 0.24, 0.25] | ||||

| Literacy | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.46 | [− 0.04, 0.09] | ||||

| Residence | − 0.05 | − 0.74 | 0.46 | [− 0.17, 0.08] | ||||

| Gratitude | 0.22 | 0.72 | 0.47 | [0.16, 0.29] | ||||

| PPR | 0.83 | 6.43 | 0.00 | [0.74, 0.92] | ||||

| RP | 0.06 | 1.71 | 0.09 | [− 0.09, 0.20] | ||||

| Gratitude x RP | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.71 | [− 0.13, 0.19] | ||||

| PPR x RP | − 0.20 | − 2.33 | 0.02 | [− 0.36, − 0.03] | ||||

Note. 'PPR' refers to Perceived Partner Responsiveness, and 'RP' refers to Relationship Satisfaction. N = 825. LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Fig. 2.

The interaction between gratitude and relationship power on perceived partner responsiveness among couples.

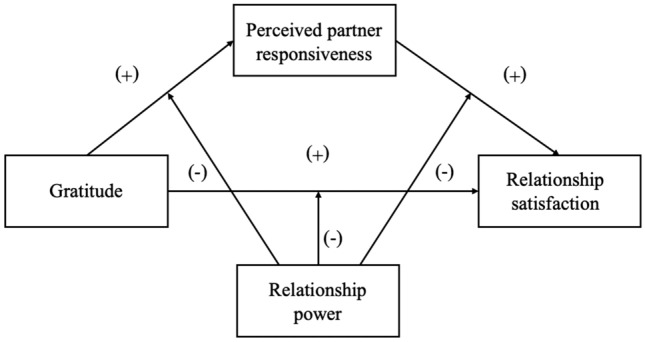

In addition, relationship power could attenuate the positive correlation between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction (β = -0.20, p < 0.05). Compared to individuals with low levels of relationship power (β = 0.05, p < 0.001), the relation between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction is weaker among those with high levels of perceived partner responsiveness (β = 0.06, p < 0.001), as can be seen in Fig. 3. However, relationship power did not significantly moderate the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction (β = 0.03, p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

The interaction between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship power on relationship satisfaction among couples. Low PPR = low perspective partner responsiveness, High PPR = high perspective partner responsiveness.

Finally, as shown in Table 5, relationship power attenuated the indirect positive relation between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. Compared to individuals with low levels of relationship power (β = 0.27 p < 0.05), the indirect positive relation between gratitude and relationship satisfaction via perceived partner responsiveness was weaker for individuals with high levels of relationship power (β = 0.11, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Direct and indirect effects (via perceived partner responsiveness) at different levels of relationship power between gratitude and relationship satisfaction.

| Relationship power | β | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||

| Low | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.30 |

| Medium | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.29 |

| High | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.32 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Low | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.36 |

| Medium | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| High | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

N = 825. LLCI = lower limit of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI = upper limit of the 95% confidence interval. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

The present study constructed a moderated mediation model to investigate the attenuating role of relationship power on gratitude and relationship satisfaction among couples. The results found that gratitude was positively related to relationship satisfaction via the mediating role of perspective partner responsiveness. Interestingly, compared to individuals with low levels of relationship power, the strength of a positive association between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness as well as that between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction was reduced significantly for individuals with high levels of power. These findings have theoretical implications for deepening previous research on the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction12,64, and they have practical implications for how to intervene in gratitude and satisfaction between couples through the lens of relationship power.

The mediating role of perceived partner responsiveness

The current study suggested that perceived partner responsiveness could be a potential mediator in the link between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. These results are consistent with the relationship maintenance model12, which holds that feeling gratitude for a partner predicts enhanced responsiveness, leading to a greater willingness to maintain the relationship. Individuals with a high tendency toward experiencing gratitude may be able to better perceive their partner's emotions, better understand their partner’s intentions, and obtain more social support from their partners 65,66. Previous studies found that perceived partner-focused approach motives promoted gratitude and that this bond was mediated in part by perceived partner response67. And this study found that gratitude can positively predict perspective partner responsiveness. One possible reason is that expressions of gratitude generate a mutual interaction, and the cumulative effect of the interaction is repeated multiple times; this spiraling mutual response driven by gratitude enhances perceived partner responsiveness, thus contributing to improved relationship quality11. Another possible reason is that gratitude contributes to the reciprocal process of relationship maintenance. Through this process, the responses, perceptions, and feelings of the other person are affected, thereby enhancing the ability of perceived partner responsiveness30,39. The present study also found that perceived partner responsiveness could positively predict relationship satisfaction. A diary study found that the effect of sexual satisfaction on marital satisfaction was partially mediated by perceived partner responsiveness68. This suggests that perceived partner responsiveness is a core feature of close, satisfying relationships69. Individuals who exhibit stable emotional dynamics and can respond appropriately to their intimate partner's emotional signals and needs are perceived by their partners as responding positively, thus contributing to the maintenance of the quality of the intimate relationships70. In addition, it has been suggested that the projection of own responsiveness is an important determinant of perceived social support and a means by which caring perceivers maintain satisfying and subjectively communal relationships71.

The Attenuating role of relational power

In addition, the present study found that the strength of positive prediction between gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness as well as the relationship between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction was significantly reduced by relationship power. The above correlations were weaker for high-power individuals compared to low-power individuals in romantic relationships. These findings are consistent with the social distance theory of power23, which proposes that relatively low-powered individuals show more attention and reaction to the behaviors and characteristics of their interaction partners. First, relationship power may attenuate the positive role of gratitude on perceived partner responsiveness. High relationship power will prevent individuals from adopting the perspectives of their partner, less accurately perceiving the intentions of others, and less accurately capturing emotional changes in their partners20,72. It suggested that high-power individuals were more concerned with themselves than with their partners. Therefore, one possible reason why high relationship power leads to a weakening of the gratitude-perspective partner responsiveness correlation is that high-powered individuals refuse to perceive others and are unable to be sufficiently grateful for the good deeds of their partners in romantic relationships. In addition, individuals with high power exhibit an increased perception of psychological privilege, and lead that they expect their low-power partners to placate them in various ways, have a greater desire to accept favors from others, and demonstrate a reduced comprehension of their partner’s perspectives, thoughts, and feelings73. Another possible reason is that high-power individuals hold the belief that their partner should strive to fulfill their needs as much as possible, and they perceive this as the natural order, thus hindering their ability to accurately interpret their partners’ responses.

And, we found relationship power impaired the positive role of perceived partner responsiveness on relationship satisfaction. Specifically, the present study revealed that compared to individuals with a higher power, individuals with a lower power perceived partner responsiveness as a better predictor of satisfaction, which was consistent with the social distance theory of power23. However, high power predisposes individuals to understand things from a more abstract perspective48, to make more instrumental attributions about the behavior of others74. One potential explanation for the attenuating of the positive correlation between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction in the context of relationship power is the tendency of high-power individuals to perceive their partner's responsiveness as a utilitarian end, rather than as a purpose to solidify the quality of the intimate relationship. In addition, high relationship power may lead to decreased levels of commitment to intimacy48. Even if the individual with low relationship power in an intimate relationship responds more positively, this/her partner with high relationship power does not care the responsiveness that includes a committed nature, and therefore will not move up in satisfaction.

The present study found that relationship power could not significantly moderate the association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction in intimate relationships. One reason may be that gratitude has a strong explanatory power in understanding well-being8 and is closely related to daily satisfaction75. The relationship maintenance model indicates gratitude is especially important for the successful maintenance of intimate bonds12. Even relationship power imbalances hardly undermine the unique bond between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. Another reason may be that expressing gratitude predicts increases in the individuals’ perceptions of the communal strength of the relationship across time76, and the individuals in this study were all already in longer-term intimate relationships, so their perception of the communal strength of the relationship was stronger, which is closely related to the relationship quality77. When individuals in intimate relationships have higher levels of gratitude, their relationship satisfaction automatically increases. Thus, the effect of gratitude on relationship satisfaction is likely to be strong and stable regardless of relationship power. Additionally, we controlled for other variables in our analysis to mitigate their effects. Nonetheless, gender differences in emotional expression and communication styles might affect how gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness interact within romantic relationships. Similarly, marital status could impact relationship dynamics, with married couples potentially experiencing different levels of stability and satisfaction compared to unmarried couples. This study extends the relationship maintenance model by showing how gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness (PPR) interact with relationship power to influence satisfaction. Our findings validate the social distance theory of power, demonstrating its relevance in romantic contexts. By integrating these theories, we offer a comprehensive framework for understanding relational dynamics. This integrative approach provides valuable insights for future research on relationship satisfaction.

Practical implications

The findings can be applied in various contexts, including relationship counseling, marriage education, and personal development. First, in relationship counseling and therapy, our findings indicate that gratitude and perceived partner responsiveness can significantly enhance relationship satisfaction. Therapists can incorporate gratitude exercises to help couples improve their positive perceptions of each other78 and teach active listening and empathetic communication skills79. Therapists should also pay special attention to balancing the dynamics of power between partners. Second, in terms of personal development, individuals can improve relationship satisfaction through daily gratitude practices, which also promote overall emotional health80. Additionally, learning to respond to a partner’s needs can enhance relationship satisfaction and interpersonal skills.

Limitations and future directions

Some shortcomings in this study need to be improved in future research. First, this study used a cross-sectional questionnaire study, which resulted in findings that could not be inferred causally, and future research could explore the causal relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction by manipulating the independent and mediating variables, thus better providing a theoretical basis for gratitude interventions. Secondly, this study did not examine the association between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship power and satisfaction from a male–female dichotomous perspective. Future research can explore the satisfaction of both partners from a male–female dichotomous standpoint and delve deeper into the mechanism of power’s role in the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. Lastly, the study lacks explicit modeling of the potential moderating effects of gender and marital status on relationship satisfaction. Our findings, as depicted in Table 4, indicate that these variables significantly influence relationship satisfaction. However, they were not the primary focus of our current model. Future research should consider incorporating gender and marital status as moderating variables to better understand their impact on the dynamics of gratitude, perceived partner responsiveness, and relationship satisfaction.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study extended previous research on relationship satisfaction by developing a moderator–mediator model, which exposed the association between gratitude and relationship satisfaction from a new relationship power perspective. Our findings suggested that perceived partner responsiveness mediated the relationship between gratitude and relationship satisfaction. In addition, the results of the present study suggest that the positive gratitude-perceived partner responsiveness link, as well as the positive link between perceived partner responsiveness and relationship satisfaction, was attenuated by relationship power for individuals in intimate relationships.

Author contributions

L. J., and Y. W., wrote the main manuscript text and T. Z. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3. All authors reviewed the manuscript".

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Science of Anhui Province on Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intelligence Intervention (SYS2024XXX), the scientific and technological innovation 2030—the major project of the Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Intelligence Technology (2021ZD0200500).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B. & Layton, J. B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med.7(7), e1000316. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 (2010). 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whisman, M. A. & Baucom, D. H. Intimate relationships and psychopathology. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev.15(1), 4–13. 10.1007/s10567-011-0107-2 (2012). 10.1007/s10567-011-0107-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith, T. W. & Baucom, B. R. W. Intimate relationships, individual adjustment, and coronary heart disease: Implications of overlapping associations in psychosocial risk. Am. Psychol.72(6), 578–589. 10.1037/amp0000123 (2017). 10.1037/amp0000123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamczyk, K., Barr, A. B. & Segrin, C. Relationship status and mental and physical health among Polish and American young adults: The role of relationship satisfaction and satisfaction with relationship status. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being13(3), 620–652. 10.1111/aphw.12248 (2021). 10.1111/aphw.12248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton, A. W., Jenkins, A. I. C., Gong, Q., Sutton, N. C. & Beach, S. R. The protective effects of perceived gratitude and expressed gratitude for relationship quality among African American couples. J. Soc. Pers. Relat.40(5), 1622–1644 (2023). 10.1177/02654075221131288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Körner, R. & Schütz, A. Power in romantic relationships: How positional and experienced power are associated with relationship quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relat.38(9), 2653–2677 (2021). 10.1177/02654075211017670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Candel, O. S. & Turliuc, M. N. The role of relational entitlement, self-disclosure and perceived partner responsiveness in predicting couple satisfaction: A daily-diary study. Front. Psychol.12, 609232 (2021). 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.609232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J. & Geraghty, A. W. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev.30(7), 890–905. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005 (2010). 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datu, J. A. D., Valdez, J. P. M., McInerney, D. M. & Cayubit, R. F. The effects of gratitude and kindness on life satisfaction, positive emotions, negative emotions, and COVID-19 anxiety: An online pilot experimental study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being14(2), 347–361. 10.1111/aphw.12306 (2022). 10.1111/aphw.12306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang, D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: A daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Gerontol.77(4), e36–e45. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa220 (2022). 10.1093/geronb/gbaa220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Algoe, S. B., Fredrickson, B. L. & Gable, S. L. The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion13(4), 605–609. 10.1037/a0032701 (2013). 10.1037/a0032701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., Oveis, C. & Keltner, D. To have and to hold: Gratitude promotes relationship maintenance in intimate bonds. J. Person. Soc. Psychol.103(2), 257–274. 10.1037/a0028723 (2012). 10.1037/a0028723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredrickson, B. L. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. The Psychology of Gratitude (Vol.8, pp.145–166). New York: Oxford University Press (2004).

- 14.Leong, J. L. T. et al. Is gratitude always beneficial to interpersonal relationships? The interplay of grateful disposition, grateful mood, and grateful expression among married couples. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull.46(1), 64–78. 10.1177/0146167219842868 (2020). 10.1177/0146167219842868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, Y. P., Dwyer, P. C. & Algoe, S. B. Better together: Integrative analysis of behavioral gratitude in close relationships using the three-factorial interpersonal emotions (TIE) framework. Emotion22(8), 1739–1754. 10.1037/emo0001020 (2022). 10.1037/emo0001020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funk, J. L. & Rogge, R. D. Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. J. Fam. Psychol.21(4), 572–583. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 (2007). 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, M. D. et al. Women and men are the barometers of relationships: Testing the predictive power of women’s and men’s relationship satisfaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA119(33), e2209460119. 10.1073/pnas.2209460119 (2022). 10.1073/pnas.2209460119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornelius, T., Desrosiers, A. & Kershaw, T. Spread of health behaviors in young couples: How relationship power shapes relational influence. Soc. Sci. Med.165, 46–55. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.030 (2016). 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson, J. A., Farrell, A. K., Oriña, M. M., & Rothman, A. J. Power and social influence in relationships. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal Relations (pp. 393–420) (2015). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14344-015

- 20.Anicich, E. M., Lee, A. J. & Liu, S. Thanks, but No thanks: Unpacking the relationship between relative power and gratitude. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull.48(7), 1005–1023. 10.1177/01461672211025945 (2022). 10.1177/01461672211025945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawyer, K. B. et al. Being present and thankful: A multi-study investigation of mindfulness, gratitude, and employee helping behavior. J. Appl. Psychol.107(2), 240–262. 10.1037/apl0000903 (2022). 10.1037/apl0000903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ksenofontov, I. & Becker, J. C. The harmful side of thanks: Thankful responses to high-power group help undermine low-power groups’ protest. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull.46(5), 794–807. 10.1177/0146167219879125 (2020). 10.1177/0146167219879125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magee, J. C., & Smith, P. K. The social distance theory of power. Person. Soc. Psychol. Rev. Inc17(2), 158–186 (2013). 10.1177/1088868312472732 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Reis, H. T. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In Relationships, Well-being and Behaviour 113–143 (Routledge, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reis, H. T. & Gable, S. L. Responsiveness. Curr. Opin. Psychol.1, 67–71. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.001 (2015). 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crasta, D., Rogge, R. D., Maniaci, M. R. & Reis, H. T. Toward an optimized measure of perceived partner responsiveness: Development and validation of the perceived responsiveness and insensitivity scale. Psychol. Assess.33(4), 338–355. 10.1037/pas0000986 (2021). 10.1037/pas0000986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Algoe, S. B. & Way, B. M. Evidence for a role of the oxytocin system, indexed by genetic variation in CD38, in the social bonding effects of expressed gratitude. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci.9(12), 1855–1861. 10.1093/scan/nst182 (2014). 10.1093/scan/nst182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ter Kuile, H., Kluwer, E. S., Finkenauer, C. & Van Der Lippe, T. Predicting adaptation to par enthood: The role of responsiveness, gratitude, and trust. Pers. Relatsh.24, 663–682. 10.1111/pere.12202 (2017). 10.1111/pere.12202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jolink, T. A., Chang, Y. P. & Algoe, S. B. Perceived partner responsiveness forecasts behavioral intimacy as measured by affectionate touch. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull.48(2), 203–221. 10.1177/0146167221993349 (2022). 10.1177/0146167221993349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubacka, K. E., Finkenauer, C., Rusbult, C. E. & Keijsers, L. Maintaining close relationships: Gratitude as a motivator and a detector of maintenance behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull.37(10), 1362–1375. 10.1177/0146167211412196 (2011). 10.1177/0146167211412196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosen, N. O. et al. Sexual intimacy in first-time mothers: Associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction across three waves. Arch. Sex. Behav.49, 2849–2861. 10.1007/s10508-020-01667-1 (2020). 10.1007/s10508-020-01667-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debrot, A., Cook, W. L., Perrez, M. & Horn, A. B. Deeds matter: Daily enacted responsiveness and intimacy in couples’ daily lives. J. Fam. Psychol.26(4), 617–627. 10.1037/a0028666 (2012). 10.1037/a0028666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manne, S. et al. The interpersonal process model of intimacy: The role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. J. Fam. Psychol.18(4), 589–599. 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589 (2004). 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visserman, M. L. et al. Lightening the load: Perceived partner responsiveness fosters more positive appraisals of relational sacrifices. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.123(4), 788–810. 10.1037/pspi0000384 (2022). 10.1037/pspi0000384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalifian, C. E. & Barry, R. A. The relation between mindfulness and perceived partner responsiveness during couples’ vulnerability discussions. J. Fam. Psychol.35(1), 1–10. 10.1037/fam0000666 (2021). 10.1037/fam0000666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurenceau, J. P., Barrett, L. F. & Rovine, M. J. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. J. Fam. Psychol.19(2), 314–323. 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314 (2005). 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smallen, D., Eller, J., Rholes, W. S. & Simpson, J. A. Perceptions of partner responsiveness across the transition to parenthood. J. Fam. Psychol.36(4), 618. 10.1037/fam0000907 (2022). 10.1037/fam0000907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Algoe, S. B. & Zhaoyang, R. Positive psychology in context: Effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. J. Posit. Psychol.11(4), 399–415. 10.1080/17439760.2015.1117131 (2016). 10.1080/17439760.2015.1117131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Algoe, S. B. Find, remind, and bind The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass6(6), 455–469. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x (2012). 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams, L. A. & Bartlett, M. Y. Warm thanks: Gratitude expression facilitates social affiliation in new relationships via perceived warmth. Emotion15(1), 1–5. 10.1037/emo0000017 (2015). 10.1037/emo0000017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knudson-Martin, C. Why power matters: Creating a foundation of mutual support in couple relationships. Fam. Process52(1), 5–18. 10.1111/famp.12011 (2013). 10.1111/famp.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H. & Anderson, C. Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychol. Rev.110(2), 265–284. 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265 (2003). 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magee, J. C. & Galinsky, A. D. 8 social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Acad. Manag. Ann.2(1), 351–398. 10.1080/19416520802211628 (2008). 10.1080/19416520802211628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacKenzie, M. J. & Baumeister, R. F. Motivated gratitude and the need to belong: Social exclusion increases gratitude for people low in trait entitlement. Motiv. Emot.43(3), 412–433. 10.1007/s11031-018-09749-3 (2019). 10.1007/s11031-018-09749-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindová, J., Průšová, D. & Klapilová, K. Power distribution and relationship quality in long-term heterosexual couples. J. Sex Marital Therapy46(6), 528–541. 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1761493 (2020). 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1761493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahoney, A. R. & Knudson-Martin, C. The social context of gendered power. In Couples, Gender, and Power: Creating Change in Intimate Relationships (eds Knudson-Martin, C. & Mahoney, A.) 17–29 (Springer Publishing Company, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottman, J. M. Gottman method couple therapy. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy (pp. 138–164) (2008). New York: Guildford

- 48.Inesi, M. E., Gruenfeld, D. H. & Galinsky, A. D. How power corrupts relationships: Cynical attributions for others’ generous acts. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol.48(4), 795–803. 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.01.008 (2012). 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Kleef, G. A. & Lange, J. How hierarchy shapes our emotional lives: Effects of power and status on emotional experience, expression, and responsiveness. Curr. Opin. Psychol.33, 148–153. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.009 (2020). 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Overall, N. C., Hammond, M. D., McNulty, J. K. & Finkel, E. J. When power shapes interpersonal behavior: Low relationship power predicts men’s aggressive responses to low situational power. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.111(2), 195–217. 10.1037/pspi0000059 (2016). 10.1037/pspi0000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Righetti, F. et al. The prosocial versus proself power holder: How power influences sacrifice in romantic relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull.41(6), 779–790. 10.1177/0146167215579054 (2015). 10.1177/0146167215579054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods39(2), 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 (2007). 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 499–500 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitton, S. W. & Kuryluk, A. D. Relationship satisfaction and depressive symptoms in emerging adults: Cross-sectional associations and moderating effects of relationship characteristics. J. Fam. Psychol.26(2), 226–235. 10.1037/a0027267 (2012). 10.1037/a0027267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Don, B. P., Fredrickson, B. L. & Algoe, S. B. Enjoying the sweet moments: Does approach motivation upwardly enhance reactivity to positive interpersonal processes?. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.122(6), 1022–1055. 10.1037/pspi0000312 (2022). 10.1037/pspi0000312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mccullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A. & Tsang, J. A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.82(1), 112–127. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112 (2002). 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei, C., Wu, H., Kong, X. & Wang, H. Revision of gratitude questionnaire—6 in Chinese adolescent and its validity and reliability. Chin. J. School Health32(10), 1201–1202 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reis, H. T., Maniaci, M. R., Caprariello, P. A., Eastwick, P. W. & Finkel, E. J. Familiarity does indeed promote attraction in live interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.101(3), 557–570. 10.1037/a0022885 (2011). 10.1037/a0022885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang, S., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., & Li, Y. Reliability and validity test of Perceived Partner Responsiveness Scale in Chinese version. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 27(5) (2019).

- 60.Reis, H. T., Crasta, D., Rogge, R. D., Maniaci, M. R., & Carmichael, C. L. Perceived Partner Responsiveness Scale (PPRS) (Reis & Carmichael, 2006). The Sourcebook of Listening Research: Methodology and Measures (2017), 516–521. 10.1002/9781119102991.

- 61.Pulerwitz, J., Gortmaker, S. L. & DeJong, W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles42, 637–660. 10.1023/A:1007051506972 (2000). 10.1023/A:1007051506972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patrick, H., Knee, C. R., Canevello, A. & Lonsbary, C. The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.92(3), 434–457. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434 (2007). 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes, A. F. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper] (2012). Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/ public/process2012.pdf

- 64.Gordon, A. M. et al. Feeling appreciated buffers against the negative effects of unequal division of household labor on relationship satisfaction. Psychol. Sci.33(8), 1313–1327. 10.1177/09567976221081872 (2022). 10.1177/09567976221081872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arican-Dinc, B. & Gable, S. L. Responsiveness in romantic partners’ interactions. Curr. Opin. Psychol.53, 101652. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101652 (2023). 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C. & Kashdan, T. B. Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. J. Adolesc.32(3), 633–650. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006 (2009). 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Visserman, M. L., Righetti, F., Impett, E. A., Keltner, D. & Van Lange, P. A. M. It’s the motive that counts: Perceived sacrifice motives and gratitude in romantic relationships. Emotion18(5), 625–637. 10.1037/emo0000344 (2018). 10.1037/emo0000344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gadassi, R. et al. Perceived partner responsiveness mediates the association between sexual and marital satisfaction: A daily diary study in Newlywed couples. Arch. Sex. Behav.45(1), 109–120. 10.1007/s10508-014-0448-2 (2016). 10.1007/s10508-014-0448-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Canevello, A. & Crocker, J. Creating good relationships: responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.99(1), 78–106. 10.1037/a0018186 (2010). 10.1037/a0018186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luginbuehl, T. & Schoebi, D. Emotion dynamics and responsiveness in intimate relationships. Emotion20(2), 133–148. 10.1037/emo0000540 (2020). 10.1037/emo0000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemay, E. P. Jr., Clark, M. S. & Feeney, B. C. Projection of responsiveness to needs and the construction of satisfying communal relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.92(5), 834–853. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834 (2007). 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith, P. K. & Trope, Y. You focus on the forest when you’re in charge of the trees: Power priming and abstract information processing. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.90(4), 578–596. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.578 (2006). 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Inesi, M. E. & Gruenfeld, D. H. Power and perspectives not taken. Psychol. Sci.17(12), 1068–1074. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01824.x (2006). 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Overbeck, J. R. & Park, B. When power does not corrupt: superior individuation processes among powerful perceivers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.81(4), 549–565. 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.549 (2001). 10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park, Y., Impett, E. A., MacDonald, G. & Lemay, E. P. Saying “thank you”: Partners’ expressions of gratitude protect relationship satisfaction and commitment from the harmful effects of attachment insecurity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.117(4), 773–806. 10.1037/pspi0000178 (2019). 10.1037/pspi0000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D. & Graham, S. M. Benefits of expressing gratitude: expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychol. Sci.21(4), 574–580. 10.1177/0956797610364003 (2010). 10.1177/0956797610364003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Balzarini, R. N. et al. The detriments of unmet sexual ideals and buffering effect of sexual communal strength. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.120(6), 1521–1550. 10.1037/pspi0000323 (2021). 10.1037/pspi0000323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L. & Maisel, N. C. It’s the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Pers. Relatsh.17(2), 217–233 (2010). 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cole, S. A., Sannidhi, D., Jadotte, Y. T. & Rozanski, A. Using motivational interviewing and brief action planning for adopting and maintaining positive health behaviors. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis.77, 86–94. 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.003 (2023). 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emmons, R. A. & McCullough, M. E. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.84(2), 377 (2003). 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.