Abstract

Many chemotherapies, which are still the main clinical treatment for primary tumors, will induce persistent DNA damage in non-tumor stromal cells, especially cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and activate them to secrete senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The transition could further result in the formation of tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment and cause drug resistance of neighboring tumor cells. To solve this dilemma, a multi-functional biomimetic drug delivery system (named mPtP@Lipo) was rationally developed by combining CAFs reshaper ginsenoside 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) and cisplatin prodrug (PtLA) to inhibit tumor progression and the formation of SASP. To achieve effective delivery of these molecules deep into the desmoplastic tumor, fibroblast membrane was fused with liposomes as a targeting carrier. In vitro and in vivo results showed that mPtP@Lipo could penetrate deep into the tumor, reverse CAFs phenotype and inhibit SASP formation, which then blocked the immunosuppressive progress and thus reinforced anti-tumor immune response. The combination of chemotherapeutics and CAFs regulator could achieve both tumor inhibition and tumor immune microenvironment remodeling. In conclusion, mPtP@Lipo provides a promising strategy for the comprehensive stromal-desmoplastic tumor treatment.

Keywords: MT: Regular Issue, cancer-associated fibroblasts, chemotherapy, liposomes, senescence-associated secretory phenotype, tumor microenvironment

Graphical abstract

A multi-functional biomimetic drug delivery system (named mPtP@Lipo) was rationally developed by combining CAFs reshaper ginsenoside 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) and cisplatin prodrug (PtLA) to regulate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and the formation of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), leading to effective tumor inhibition.

Introduction

Tumor microenvironment (TME), consisting of tumor cells, lymphocytes, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM), plays a crucial role in tumor progression and metastasis. The stromal cells in the tumor site are regarded as the soil of tumor, supporting the tumor progression or even metastasis under instigation of tumor cells. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the main components of stromal cells, which account for 40%–50% in tumor1 or 80% in desmoplastic tumor,2 significantly contribute to tumor cell proliferation, migration, and immune suppression.3 CAFs frequently gather around the vessels, forming a physical barrier with secreted rich ECM,4 leading to the stromal-vessel-type tumor. This results in the off-target of therapeutic agents and formation of immunosuppressive TME with reduced lymphocyte and cytokine infiltration.5,6 Previous studies showed that CAFs increased the paracrine of survival factors, leading to chemo-resistance and stromal restoration when exposed to cisplatin-loaded nanoparticles.7 DNA damage agents, such as platinum (Pt) drugs, could induce the DNA damage of CAFs, and persistent DNA damage caused cellular senescence of CAFs,8 which is the latest hallmark of tumors.9 Senescent cells then undergo proinflammatory genomic reprogramming and release various types of cytokines, called senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).10 SASP could enable CAFs to interact with other cells in tumor and results in tumor stemness and immunosuppression.11 Thus, it is rational to treat desmoplastic tumor by combing the strategy of CAFs reversion and downstream cytokines regulation with chemotherapeutics.

Natural products have gained increasing attention in oncotherapy due to their safety profile and multifunction, and previous studies had found several natural products for CAFs and inflammation regulation,12,13,14 as a combination therapy. Moreover, many of the SASP factors are proinflammatory cytokines and activated through the NF-κB pathway,15 suggesting the tight connection between SASP and inflammation. Research has shown that procyanidin C1 (PCC1) could enhance therapeutic efficacy when co-administered with chemotherapy through senescent cells depletion.16 However, few studies have been carried out to focus on the inhibition efficacy of natural product on SASP.

Herein, anti-inflammatory ginsenosides were screened based on their down-regulation effect on the activated CAFs. Among them, ginsenoside 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) showed the most evident inhibition of CAFs activation. PPD is a final metabolite of protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides such as ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rh2, and Rg3, and its multiple biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrosis, and anti-tumor activity, have been reported.17,18,19,20 However, the effect and mechanism of PPD on CAFs and on SASP remain unknown.

To achieve CAFs regulation and deep penetration, the nanotechnology and biomimetic strategy was considered. Previous studies had shown the cell membrane coating or fusion endowed nanoparticles with similar surface properties and functions such as tumor targeting capability.21,22,23,24,25 Considering the core strategy of CAFs regulation, fibroblast membranes were adopted to fuse with the liposomes, and a stroma-rich tumor model was established by co-implanting lung cancer cells with fibroblasts, which resembles the components and morphology of the TME.7 Ginsenosides can also replace cholesterol as a stabilizer in liposomes, which avoid some disadvantages of cholesterol, such as inducing CD8 T cell exhaustion, leading to uncontrolled tumor growth.26

In this work, a multi-drug liposomal delivery system was developed to overcome the above-mentioned problems, as depicted in Figure 1. First, the fused fibroblast membrane tended for deep penetration into the internal tumor via the imitation of CAFs to get across the barrier of CAFs. Subsequently, cisplatin prodrug (PtLA) and PPD kept in proportion achieved the tumor and exerted anti-cancer effect, respectively. To be specific, PPD saved activated CAFs from cell senescence, avoiding formation of SASP and drug resistance of tumor cells to Pt. Consequently, the elimination of SASP factors, such as interleukin (IL)-6, blocked the autocrine loop of CAFs and their interaction with other cells, which triggered the remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) and relief of immunosuppression. In brief, this work intends to clarify the therapeutic effects of mPtP@Lipo in dual-targeting tumor and CAFs and achieve the dual purposes of tumor inhibition and CAFs remodeling, which opens an avenue of therapeutic strategies for stromal-desmoplastic tumor treatment.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of mPtP@Lipo interacting with cells in the TME, especially CAFs and tumor cells, and thus affecting cascading immunocytes and remodeling TME

The membrane camouflages endowed mPtP@Lipo with deep intratumoral penetration. The combination release of Pt and PPD enhanced Pt-induced tumor apoptosis while PPD regulated the CAFs to avoid the SASP formation, and thus blocked the crosstalk between CAFs with other cells. The elimination of SASP unleashed host immunosuppression, resulting in the stronger immune response and the regression of tumors.

Results

Preparation and characterization of mPtP@Lipo

Ginsenosides with anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrosis activities, R1, Rb1, Rd, Re, Rg1, Rg3, Rh2, PPD, and astragaloside IV (AS-IV) as a control, were first screened to determine their capability to inhibit activated CAFs. α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) is a marker of CAFs activation. The expression of α-SMA in activated CAFs was significantly down-regulated when treated with PPD compared with other ginsenosides (Figure S1), indicating that PPD could inhibit the activation of CAFs and be a regulator for TME.

Design of cisplatin prodrug was applied to develop Pt derivatives with improved encapsulation efficiency in liposomes. The PtLA was synthesized according to previous report,27 by mildly oxidizing cisplatin with H2O2, then reacting the intermediates with lauric anhydride (LA). The detailed synthesis protocol and characterization are summarized in Figures S2 and S3.

mPtP@Lipo and other liposomes were prepared by filming-rehydration method (Figure 2A). Extrusion step was used to induce the complete fusion of fibroblast membranes and liposomes. The particle size of mPtP@Lipo was 133.1 ± 2.37 nm with zeta potential of −26.2 ± 0.757 mV (Figure S4; Table S1), which was similar to the membrane potential. The morphology was observed under transmission electron microscopy (TEM), presenting spherical shape and good dispersity (Figure 2B). The Pt loading efficiency of mPtP@Lipo was 9.36% ± 0.43% and of other Pt-loaded liposomes was about 6%. The PPD loading efficiency of mPtP@Lipo was 11.85% ± 0.18% and other PPD-loaded liposomes was about 8%, indicating mPtP@Lipo exhibited a higher encapsulation capability than other liposomes, which might attribute to the function of ginsenoside to regulate the lipid bilayer fluidity in liposomes.

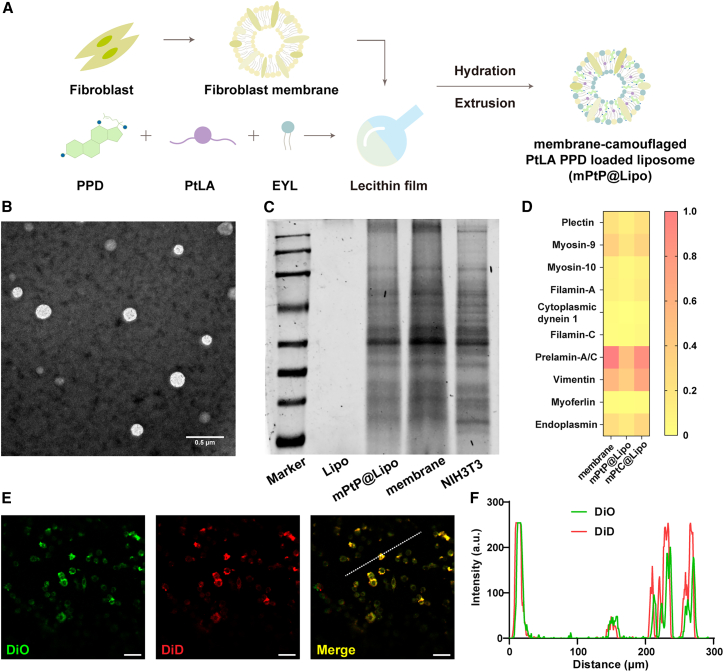

Figure 2.

Preparation and characterization of mPtP@Lipo

(A) Schematic illustration for the isolation of fibroblast membrane fragments and the preparation of mPtP@Lipo by filming-rehydration. (B) The typical TEM image of mPtP@Lipo. Scale bar, 0.5 μm. (C) The SDS-PAGE pattern of proteins isolated from fibroblasts, fibroblast membrane fragments, and mPtP@Lipo. (D) Top 10 identified proteins of fibroblast, mPtC@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo analyzed by LC-MS. (E) CLSM images of LLC cells incubated with mPtP@Lipo. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) The overlapping fluorescence intensity of traces (dotted white lines in E).

The protein composition reserved on the biomimetic liposomes was analyzed by SDS-PAGE to compare biomarker fingerprints of mPtP@Lipo, membrane fragments, and NIH3T3cells. From Figure 2C, it was found that mPtP@Lipo inherited proteinogram completely from NIH3T3cells, as well as membrane fragments. The top 10 identified proteins of fibroblasts were analyzed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and the results showed homology of highly retained proteins, indicating that the fabrication process of mPtP@Lipo had little impact on the constituent of proteins (Figure 2D). Moreover, a cellular internalization process was observed by confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) to examine the integrality of mPtP@Lipo. Membrane and liposome were labeled by different fluorescence dyes, respectively. Co-localization analysis demonstrated that mPtP@Lipo could maintain its integrality and fusion when entering cells (Figures 2E and 2F). These results confirmed the successful fusion of fibroblast membrane and liposomes.

Previous studies have shown that Pt prodrug could release Pt through intracellular redox-responsive process and achieve specific anti-tumor effect. The drug release under different media was conducted, and the released Pt and PPD were measured, respectively. As shown in Figures S5A and S5B, for mPtP@Lipo incubated with redox medium, about 80% of Pt and PPD were detected over the course of 72 h, indicating that entrapped drugs could obtain the synchronous release in response to the reductive condition. However, for mPtP@Lipo incubated with PBS (Figure S5C), less than 20% of Pt was released within the same intervals, demonstrating that the liposomes could avoid the burst release of Pt.

PPD in mPtP@Lipo alleviated Pt-induced cellular senescence and SASP in vitro

It is reported that Pt treatment could induce DNA damage, and persistent DNA damage in non-tumor stromal cells would convert cells into SASP.8,10 SASP enabled CAFs to adapt TME for tumor progression and propel the immunosuppression. Thus, the fabrication of mPtP@Lipo were hypothesized to achieve the regulation of SASP in CAFs and a cascade of immune responses (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

mPtP@Lipo alleviated Pt-induced SASP and engaged in the amplification of the immune cascade

(A) Schematic illustration for the TME regulation process of mPtP@Lipo. (B) Representative images for SA-β-Gal staining of NIH3T3cells after different treatments at the same concentration of Pt. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) Heatmap for representative SASP factors gene in CAFs after different treatments at the same concentration of Pt. (D) Protein expression of p-p38 and p38 in CAFs after different treatments. (E) Quantitative analysis for p-p38/p38 protein level. (F) Quantitative analysis for in vitro induction of immature DC maturation, n = 3. (G) Quantitative analysis for in vitro activation of T lymphocytes, n = 3. (H) Quantitative analysis for protein expression of IL-6 on CAFs after treatments in vitro, n = 3. (I) Representative flow cytometry analysis for gating mature DCs. (J) Representative flow cytometry analysis for gating CD3+CD69+ T cells. Data in (E), (F), and (G) represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Since increased lysosomal SA-β-Gal is a key biomarker of senescent cells, the cellular states of cellular senescence were evaluated by SA-β-Gal imaging of NIH3T3cells after different treatments at the same concentration of Pt. As shown in Figure 3B, the CAFs treated with groups containing Pt showed the presence of SA-β-Gal (green), while the CAFs treated with groups containing both Pt and PPD displayed similar cellular status to the control group, which indicated that PPD could inhibit the formation of SASP, and the absence of PPD was beyond restraint of cellular senescence. Further, typical SASP factors were quantified at the mRNA level, including interleukin (IL)-1a, IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, Wnt16, Wnt3a, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP) 3, MMP9, MMP12, and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (CXCL12). The expression of these factors in mRNA level was significantly down-regulated after treatment with the PPD-included groups (Figure 3C). Therein, PtC@Lipo and mPtC@Lipo group showed significant increase of SASP factors, while PtP@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo group realized evident decrease of them. Among all the groups, mPtP@Lipo group showed the strongest effect to decrease the production of SASP factors, due to the higher cellular internalization and uptake. A key factor, IL-6, was further determined by ELISA. As shown in Figure 3H, the concentration of IL-6 was significantly down-regulated with PPD-included treatment. The results verified that PPD combined with Pt in liposomes could alleviate Pt-induced cellular senescence and SASP, realize phenotypical reversion of CAFs, and inhibit the production of SASP.

Thus, further studies were carried out to explore the possible mechanism by mPtP@Lipo on alleviating cellular senescence and SASP. Since the SASP is replete in inflammatory cytokines,28 and anti-inflammation activity of PPD was reported to be mediated through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway,17 the activation of p38 MAPK pathway in CAFs after the treatment of mPtP@Lipo was investigated. As shown in Figures 3D and 3E, the groups containing both Pt and PPD showed nearly half the phosphorylation level compared with those containing only Pt, which proved that Pt could induce p38 phosphorylation and the treatment with PPD will down-regulate this process. And the phosphorylation level in mPtP@Lipo treatment has lowered to a similar level as in PBS treatment. This result demonstrated that PPD in mPtP@Lipo could regulate cellular senescence and SASP of CAFs through p38 MAPK pathway.

mPtP@Lipo engaged in immune response reinforcement in vitro

It was hypothesized that the SASP enabled CAFs to interact with other cells in TME and drove them to tolerate or even support tumor growth, especially immune cells (Figure 3A). Therefore, the effect of mPtP@Lipo on immune cascade reactions were studied.

The direct cytotoxicity against multicellular model with LLC cells and NIH3T3cells was estimated by MTT assay, and cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cellular viability is shown in Figure S6A and EC50 results are listed in Table S2. mPtP@Lipo showed the lowest EC50 value (5.339 ± 0.008 nM at 48 h). Subsequently, apoptosis assay with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining was conducted (Figures S6B and S6C). Flow cytometry analysis found that groups containing Pt all could improve apoptosis, among which mPtP@Lipo significantly enhanced the effect of PtLA to induce cell apoptosis and necrosis, from 15.50% ± 0.29% to 34.19% ± 0.58%.

Immature dendritic cells (DCs) were obtained from bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. CAFs were pre-treated with different groups and co-cultured with LLC cells, then the supernatant from LLC cells was collected for DC maturation assay, respectively. Mature DCs were measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Figures 3F and 3I, the percentage of CD80+CD86+ DCs increased in groups containing PPD compared with those containing only Pt. PtLA- and PtC@Lipo-treated groups showed a similar level of DC maturation due to Pt-induced tumor immunogenic antigens in the supernatant. Consistent with membrane camouflage, the mPtC@Lipo group showed a 1.1-fold percentage of mature DCs than PtLA and PtC@Lipo. mPtP@Lipo displayed the highest percentage of mature DCs (47.2% ± 0.45%), 1.2-time increase than that of PtP@Lipo. These results supported the hypothesis that the inhibition of SASP after PPD-included treatment could boost the maturation of DCs.

T cell activation was also estimated by flow cytometry. Primary lymphocytes were isolated from the spleen of healthy C57BL/6 mice and incubated with pre-treated DCs (with lipopolysaccharide [LPS] and supernatant from LLC cells treated with different groups). CD69, an early marker of T cell activation, was detected to express the level of T cell activation. As shown in Figures 3G and 3J, groups containing PPD consistently showed improved level of T cell activation compared with those containing only Pt. PtP@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo showed similar levels of T cell activation, 12.63-fold over control and 1.2-fold over PtC@Lipo and mPtC@Lipo, indicating that PPD in PtP@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo assisted to activate T cells based on the enhanced DC maturation. These results clarified that the inhibition of SASP after mPtP@Lipo treatment could augment the immune cascade and induce stronger immune response.

In conclusion, all in vitro results suggested that mPtP@Lipo could potentially avoid the formation of SASP, block the interaction of CAFs with immune cells, promote DC maturation from Pt-induced immunogenic antigens, and reinforce immune response.

Fibroblast membrane camouflage endowed mPtP@Lipo with improved tumor penetration and intracellular accumulation in vitro and in vivo

The cellular uptake of liposomes was evaluated by loading DiD as a fluorescent probe to trace them. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the camouflage with fibroblast membranes increased the uptake efficiency of liposomes (Figures 4A and S7), due to tumor affinity. Considering the CAFs-induced off-target, transwell model was established to simulate the CAFs physical barrier according to previous work.29 LLC cells were seeded in the basal chamber with NIH3T3 cells seeded in the transwell inserts, and then observed using CLSM. As shown in Figures 4B and 4C, the camouflages with fibroblast membranes endowed liposomes with higher efficiency of crossing CAFs barrier than those without membrane fusion. mPtP@Lipo showed the best ability to cross CAFs barrier and reach the tumor cells, which was 21.5- and 2.1-fold higher than PtC@Lipo and PtP@Lipo, respectively. The uptake efficiency by tumor cells of PtP@Lipo also showed 10.3-fold higher than PtC@Lipo, indicating that PPD in PtP@Lipo could reeducate CAFs and down-regulate the barrier compactness, contributing to higher uptake in tumor cells.

Figure 4.

mPtP@Lipo enhanced the cellular internalization and deep tumor penetration in vitro and in vivo

(A) Histogram analysis for cellular uptake of liposomes in LLC cells in vitro. (B) CLSM images of LLC cells in transwell model after incubation with liposomes. The visualization of cells was achieved by DAPI staining. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Quantitative analysis for cellular uptake in (B), n = 3. (D) Representative images of multicellular tumor spheroid with different treatments. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis for penetration ratio, n = 3. (F) Quantitative analysis for penetration ratio of tumor cells to CAFs, n = 3. (G) Representative IVIS images of tumor-bearing mice after i.v. injection of PtC@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, PtP@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo. (H) Ex vivo IVIS images of tumors. (I) Quantitative analysis based on fluorescence intensity of tumors, n = 3. Data in (C), (E), (F), and (I) represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

A multicellular tumor spheroids model was established to evaluate the tumor penetration of liposomes. LLC cells (blue), NIH3T3cells (green) and different liposomes (red) were pre-dyed, respectively. Tumor spheroids were treated and observed under CLSM using z axis scanning. As shown in Figure 4D, LLC cells (blue) and NIH3T3 cells (green) were promiscuously mixed, the same as how TME was constructed in vivo. Quantitative analysis showed that mPtP@Lipo presented the deepest penetration distance (90.97 ± 0.43 μm) (Figure S8; Table S3) and the highest penetration rate (17.03% ± 0.29%) (Figure 4E), verifying the enhanced penetration with membrane camouflaged. Moreover, internalization in LLC cells and NIH3T3 cells was evaluated, respectively. The penetration ratio of tumor cells to CAFs were then calculated. As shown in Figure 4F, mPtP@Lipo significantly increased tumor cellular internalization and assisted liposome redistribution in the tumor site. Interestingly, PtP@Lipo and mPtC@Lipo showed similar level of penetration ratio of tumor cells to CAFs, indicating that PPD also facilitated penetration and cellular internalization process to some extent besides the membrane fused on the liposomes, perhaps because of its effect on CAFs re-education and CAFs barrier impairment. These results clarified the efficiency of camouflages with fibroblast membrane to enhance the tumor penetration in vitro, further emphasizing the superiority of the strategy of biomimetic design in tumor targeting drug delivery.

Next, tumor accumulation of mPtP@Lipo in vivo was evaluated using DiR as the fluorescent probe by IVIS instrument. As shown in Figure 4G, PtP@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo both rapidly arrived in the tumor site, and the fluorescence intensity increased with time and reached a maximum at 24 h, indicating the ability of biofluid retention. Then the mice were euthanized and ex vivo tissue imaging was performed. As shown in Figures 4H and 4I, mPtP@Lipo showed the highest tumor accumulation, which is 2.2-fold higher than PtP@Lipo. The intensity of mPtC@Lipo in the tumor showed 2.6-fold higher than PtC@Lipo. Consistent with in vitro results, the intensity of PtP@Lipo was slightly higher than mPtC@Lipo, indicating that PPD played a role in tumor accumulation and it seemed to be more efficient in vivo. These results confirmed the tumor enrichment and accumulation behaviors in vivo of liposomes with membrane camouflage.

mPtP@Lipo inhibited tumor growth significantly

To evaluate in vivo anti-tumor efficiency, a stromal-desmoplastic tumor model was established on C57BL/6 mice with LLC cells co-implanted with NIH3T3cells. The tumor volumes of PBS and PtLA groups grew rapidly while mPtC@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo controlled the tumor growth effectively (Figure 5A). The average tumor volume of mPtP@Lipo on day 23 post engraftment was 350 ± 110 mm3, significantly smaller than that of PtLA group (1712 ± 200 mm3), revealing that mPtP@Lipo with deep tumor penetration and CAF-targeting regulation ability presented the best anti-tumor effect (Figures 5A and S9). As shown in Figure 5B, Tumor inhibition rates (TIRs) of mPtP@Lipo group was found to be 72.81% ± 7.60%, significantly greater than 54.70% ± 11.29% for mPtC@Lipo group. Surprisingly, the PtLA group showed little effect on tumor inhibition, probably because Pt treatment induced CAFs SASP and enhanced tumor progression in return.7 And mPPD@Lipo also showed little anti-tumor efficiency, indicating that liposomes only with CAF regulatory capacity could not inhibit tumor growth effectively. Moreover, a slight weight loss induced by Pt treatment was observed in mPtC@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo group (Figure 5C), indicating that the treatment with mPtP@Lipo and mPtC@Lipo not only suppressed tumor progression but also had little side effect.

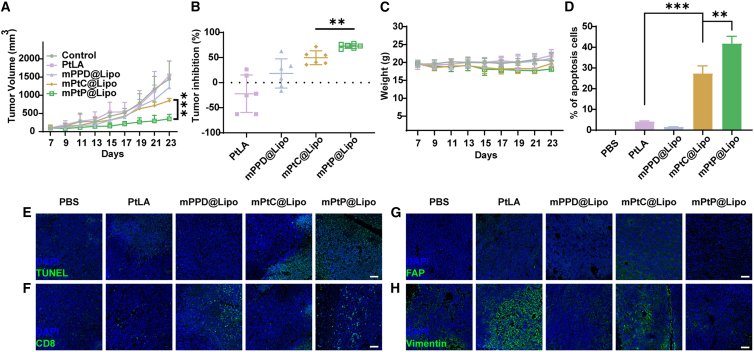

Figure 5.

Therapy with mPtP@Lipo inhibited tumor growth

(A) Tumor growth profiles for tumor-bearing mice i.v. injected with PBS, PtLA, mPPD@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo, n = 6. (B) Tumor inhibition rates of tumor-bearing mice after treatment, n = 6. (C) Body weight profiles for tumor-bearing mice i.v. injected with PBS, PtLA, mPPD@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo, n = 6. (D) Quantitative analysis of TUNEL staining, n = 3. (E) TUNEL staining of internal tumor sections. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Immunofluorescence detection of tumor sections for CD8. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G) Immunofluorescence detection of tumor sections for FAP. (H) Immunofluorescence detection of tumor sections for Vimentin. Scale bar, 50 μm. Data in (A) and (B) represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Tumors were then harvested and TUNEL staining was performed to observe the intratumoral apoptosis rate of each group. As shown in Figures 5D and 5E, the groups containing Pt all presented signal of apoptosis and necrosis in vivo, including PtLA, mPtC@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo group, indicating that the apoptosis was mainly induced by Pt. Notably, the mPtP@Lipo group exhibited the strongest signal, demonstrating that mPtP@Lipo treatment induced the most extensive DNA fragmentation and contributed to proliferation arrest in the internal tumor site, leading to a deeper penetration and a marked higher tumor apoptosis.

To further evaluate primary biosafety, the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were collected for histopathology analysis (Figure S10). Pathological evaluation clarified that no obvious change observed in any organs from PBS, mPPD@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, and mPtP@Lipo groups. In comparation, the mice with free PtLA treatment presented some typical organ damage, such as liver injury with hyperemia and inflammatory infiltrates, and incomplete spleen structure. The results proved that the encapsulation of PtLA into liposomes could reduce its side effect, and mPtP@Lipo was therapeutically effective and biocompatible.

mPtP@Lipo enhanced anti-tumor immunity

The TME regulation effect of mPtP@Lipo in vivo was further evaluated on the tumor-bearing mice. First, the expression of Pt treatment induced apoptosis pathway-related proteins was measured by western blot. Pt-induced cellular suicide process led to down-regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins, dysfunction of mitochondria, release of pro-apoptotic factors, which activated caspase cascade, and finally resulted in decomposition of cellular structure. As shown in Figures 6A–6C, compared with the mPtC@Lipo group, mPtP@Lipo group resulted in a significant down-regulation of Bcl-2 with an obvious up-regulation of Caspase 3, indicating that PPD in mPtP@Lipo could enhance the Pt-induced apoptosis in vivo.

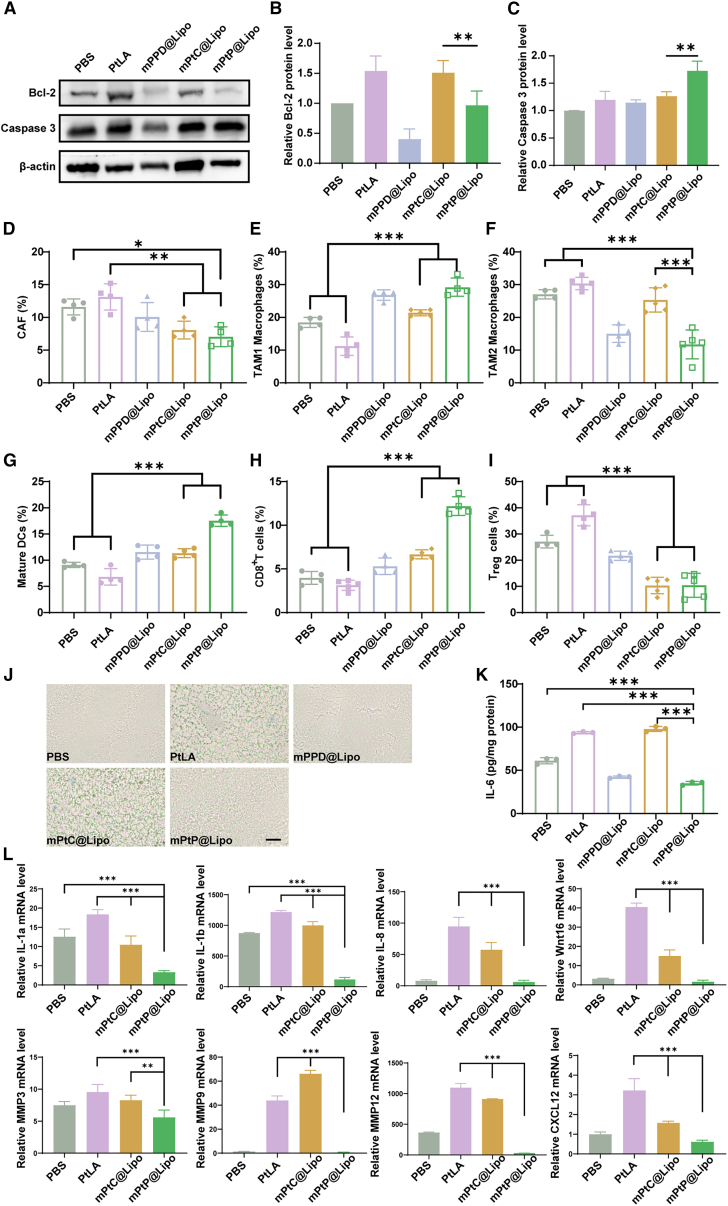

Figure 6.

mPtP@Lipo enhanced in vivo anti-tumor immunity via TME regulation

(A) Protein expression level of Bcl-2 and Caspase 3 of tumors after treatments. β-actin was used as control. (B) Quantitative analysis of Bcl-2 protein level. (C) Quantitative analysis of Caspase 3 protein level. Percentage of (D) CAFs, (E)TAM1 macrophages, (F) TAM2 macrophages, (G) mature DCs, (H) CD8+ T cells, and (I) Treg cells infiltrated in tumors after treatments, n = 4. (J) Representative images for SA-β-Gal staining of ex vivo tumor sections after treatments. Scale bar, 50 μm. (K) Quantitative analysis for protein expression of IL-6 on CAFs after treatments in vivo, n = 3. (L) Quantitative analysis for gene expression of typical SASP factors. Data in (B)–(I), (K), and (L) represent mean ± SD. n.s., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Immunophenotyping analysis was conducted to evaluate the immune response and TME regulation. The typical cell types of CAFs, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), DCs, and T cells were detected by flow cytometry, respectively (Figures S11 and S12). As shown in Figures 6D–6G, the percentage of CAFs decreased significantly from 11.59% ± 1.06% for PtLA to 7.05% ± 1.30% for mPtP@Lipo. Besides, the percentage of proinflammatory M1 phenotype TAM1 significantly increased from 11.2% ± 2.43% for PtLA to 29.23% ± 2.40% for mPtP@Lipo; while the percentage of pro-tumorigenic M2 phenotype TAM2 remarkably decreased from 30.34% ± 1.69% for PtLA to 11.74% ± 3.96% for mPtP@Lipo. The mature DCs also increased from 6.82% ± 1.35% for PtLA to 17.55% ± 0.94% for mPtP@Lipo. Additionally, compared with PBS treatment, the mPtP@Lipo treatment could significantly increase the proportion of immune-promoting cells with a marked reduction in the proportion of immunosuppressive cells. These results revealed that mPtP@Lipo efficiently mitigated immunosuppression induced by CAFs, in addition to that triggered by Pt off-target effects. Mature DCs were responsible for the activation of T cells. Hence, the percentage of CD8+ T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) were further analyzed. As shown in Figures 6H and 6I, tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells were efficiently increased from 3.14% ± 0.52% for PtLA to 12.2% ± 0.92% for mPtP@Lipo, with significant decrease in tumor-infiltrated Tregs, from 37.15% ± 3.46% for PtLA to 10.43% ± 4.10% for mPtP@Lipo.

The expression of SA-β-Gal was investigated to evaluate the cellular senescence in vivo. As shown in Figure 6J, obvious green signals were observed in PtLA and mPtC@Lipo group while no signal was found in mPPD@Lipo and mPtP@Lipo group, similar to the PBS group. The results of qRT-PCR demonstrated that cellular senescence and SASP could be avoided by mPtP@Lipo treatment. ELISA was then conducted to evaluate the level of the key SASP factor, IL-6, in tumors. IL-6, highly produced by CAFs, maintains CAFs activation by self-feedback and is the messenger between CAFs and other cells in tumor to promote tumor progression.30,31 Consistent with in vitro results, the level of IL-6 was highly expressed in PtLA and mPtC@Lipo groups while significantly decreased by 2.67-fold in the mPtP@Lipo group (Figure 6K). The results of qRT-PCR showed that typical SASP factors were all down-regulated in the mPtP@Lipo group (Figure 6L), indicating that the production of SASP was blocked by mPtP@Lipo at the gene level, thus contributing to the improvement of TIME.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of tumor sections was performed to observe CD8+ cells, which played an important role in anti-tumor immune response. Consistent with the results of immunophenotyping analysis, tumors from the mPtP@Lipo group presented the highest signal of CD8+ cells (Figure 5F). The mPtC@Lipo group showed a slight signal around the margin while mPtP@Lipo and mPPD@Lipo groups both showed intratumoral signals, indicating that CAF regulation could lead to enhanced infiltration of immune cells. Moreover, fibroblast activated protein (FAP) and Vimentin were also stained and observed under CLSM (Figures 5G and 5H). FAP is a biomarker of activated CAFs and Vimentin is a biomarker of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), highly expressed in CAFs. mPtP@Lipo group showed the lowest signal of FAP and Vimentin, indicating that mPtP@Lipo reversed the CAFs activation, thus remodeling the TME. Interestingly, mPPD@Lipo group also showed lower signal than PtLA and mPtC@Lipo groups, implying that PPD mainly contributed to the CAFs regulation.

In brief, mPtP@Lipo obviously augmented immune response compared with other groups, which was responsible for its anti-tumor effect.

Discussion

The intensifying investigation into the TME has underscored the pivotal role of CAFs as a crucial component. CAFs exhibit their versatility and intricate mechanisms that drive tumor progression, encompassing facilitation of angiogenesis, metastasis, induction of drug resistance, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and establishment of an immunosuppressive niche. Consequently, CAFs emerge as promising therapeutic targets in oncology.

Current therapeutic strategies aimed at CAFs include direct CAF elimination and regulation of upstream and downstream signaling pathways. However, clinical trials have yielded limited success, with some cases even suggesting a shortened survival period of patients. This may result from the high heterogeneity of CAFs with wide range of sources, and some subtypes may exert tumor inhibition effects. The direct elimination may instead lead to leakage and metastasis of tumor cells.32 Notably, eliminating FAP+ CAFs unexpectedly resulted in tumor progression and metastasis rather than inhibition.6 This underscores the need for a more refined, personalized approach to precisely target and regulate CAFs for optimized anti-tumor efficacy.

Single therapies toward CAFs exhibited limited effect, indicating the feasibility of the combination therapy. In addition, natural ingredients have showed their multifunction in combination therapy. It is reported that ginsenoside Rg3 could inhibit the activation of CAFs through transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad pathway,12 and quercetin could significantly suppress the expression of survival factor in activated fibroblasts,13 while 18β-glycyrrhetinic presented significant effect of down-regulation on survival factor.14 However, the access of free natural ingredients to tumor site remains challenging. Better synergy therapeutic effect can be achieved by co-delivery by nanomedicine, as an advanced drug delivery system, for combination therapy. Besides, previous studies have shown that biomimetic technology, especially membrane coating, could endow nanoparticles with biological functions similar to those of cells. Tumor cell membrane coatings have been found to obtain a homologous binding capability and thus were used to enhance the targeting delivery of liposomes.22 Similarly, other cells with tumor-homing capability, such as platelets and CAFs, have been used for nanoparticle coating.23,24,25 Moreover, it is reported that fibroblast membrane-coated nanoparticles achieved higher internalization into tumor cells and more effective tumor accumulation than that of tumor cell membrane-coated nanoparticles.23

Herein, we established a targeting drug delivery nano-system composed of chemotherapeutic, CAFs regulator and fibroblast membrane, mPtP@Lipo, for combination therapy. In this study, we focused on the CAF regulation. To achieve the ideal therapeutic effects, it is necessary to ensure the efficiency of CAF regulators, so several ginsenosides and saponins were chosen to be screened for their function. Among these ingredients, PPD exhibited the most potent ability to inhibit the CAFs activation. PtLA, a prodrug of cisplatin, was synthesized to increase its encapsulation efficiency in liposomes. The fibroblast membrane was introduced into the lipid membrane in liposomes for specific tumor targeting and penetration. Then mPtP@Lipo was prepared and characterized. The results demonstrated a defined size and zeta potential with high encapsulation efficiency of PPD and PtLA.

Upon the characterization of mPtP@Lipo, flow cytometry and confocal microscopy were used to study the cellular uptake and penetration. With the membrane modified, mPtP@Lipo displayed higher penetration capability and more internalization into tumor cells. Pt-induced cytotoxicity and cellular apoptosis could be reinforced by membrane modified and PPD, mainly because of the increasing cellular uptake. Consistent with in vitro results, in vivo results showed that mPtP@Lipo with the combination of PPD and membrane had the ability to target the tumor and achieve potent tumor inhibition.

The effect on CAF regulation and its mechanism were further studied. Surprisingly, our mPtP@Lipo could efficiently alleviate the cellular senescence and down-regulate the SASP in CAFs, partly via the inhibition of p38/MAPK pathway phosphorylation, affecting the cascade NF-κB pathway. With the down-regulation of SASP factors, especially IL-6, self-feedback and crosstalk conducted by tumor cells would be blocked. Thus, immune cascade could be initiated powerfully with the decreased tumor stemness. In vitro and in vivo results demonstrated the boosting DC maturation and T cells activation, evoking stronger immune response.

The results presented in this paper showed that our mPtP@Lipo could efficiently achieve the co-delivery of chemotherapeutic and CAF regulator to reverse the Pt-induced cellular senescence and SASP in CAFs. Taken together, this study provided further evidence for the strategy of SASP regulation combined with chemotherapy.

It is also crucial to acknowledge that other tumor types, including pancreatic cancer and breast cancer, similarly exhibit stromal cell enrichment, particularly CAFs. Given this commonality, the strategy of CAFs regulation can potentially be extended to other tumor types or related diseases characterized by fibrosis and stromal activation.

Conclusion

In this study, a dual drug delivery nano-system was developed based on the strategy of biomimetic design and TME regulation, especially SASP inhibition and CAFs reversion. mPtP@Lipo showed superiority in tumor accumulation and cellular internalization with membrane camouflages, anti-tumor effect, and augmenting immune cascade with co-loaded Pt and PPD. In conclusion, mPtP@Lipo could realize tumor targeting by fibroblast membrane fusion, inhibit the tumor progression and reverse immunosuppression successfully by combination application of Pt drug and PPD, and thus improve the tumor chemotherapy effect significantly.

Materials and methods

Preparation of fibroblast-camouflaged PPD and PtLA-loaded liposome (mPtP@Lipo)

To prepare conventional cholesterol liposomes with PtLA and fused fibroblast membrane (named mPtC@Lipo), egg yolk lecithin (EYL), cholesterol, and PtLA, at a weight ratio of 5:1:2, were dissolved in the solvent of alcohol and chloroform (1:1, v/v). The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation at 50°C to form a lipid membrane. Next, fibroblast membrane (0.3 mg/mL) was added and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 30°C. The resulting mPtC@Lipo was then extruded sequentially through 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 μm polycarbonate membranes (Nuclepore Track-Etched Membranes, Whatman, UK) at room temperature (RT) and stored at 4°C until use.

Liposomes with PPD, PtLA, and fibroblast membrane (named mPtP@Lipo) were prepared as the same procedure with PPD instead of cholesterol.

Simple liposomes with cholesterol or PPD loading PtLA (named PtC@Lipo or PtP@Lipo), and simple liposomes with only PPD (named mPPD@Lipo) were prepared as previously described without fibroblast membrane.

Fluorescence-hybrid liposomes were prepared by mixing pre-determined amounts of EYL, PPD, and PtLA and dyed with fluorescent probe (3 w/w%), and the following procedure was the same as previously described.

Physicochemical characterization of mPtP@Lipo

The morphology was observed by TEM. The size distribution, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI) of liposomes were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern Zetasizer (Nano ZS, Worcestershire, UK) at RT.

The Pt loading efficiency was determined by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, NexION 300X, PerkinElmer, USA) and calculated using the formula: Pt loading (%) = (weight of charged Pt)/(weight of mPtP@Lipo) × 100%.

The PPD loading efficiency was determined with HPLC at 203 nm and calculated as Pt loading efficiency.

Membrane protein analysis

Membrane proteins in mPtP@Lipo were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In brief, samples with the same protein concentration were heated at 100°C for 10 min and separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel at 120 V for 1 h, followed by stained and imaged with Colloidal Blue Staining Kit (PS111, EpiZyme, China).

Proteomic analysis of mPtP@Lipo was performed by label-free quantification proteomics technology with LC-MS to further illustrate the protein composition as previously described.24 Top 10 proteins were analyzed with their relative expression level.

The integrality of liposome with membrane

DiO (Ex/Em = 484/501 nm) and DiD (Ex/Em = 644/663 nm) were loaded into liposomes in fibroblast membrane and liposome lipid membrane, respectively. LLC cells were seeded in 35 mm sterile glass bottom culture dishes and cultured with complete medium for 24 h. The cells were exposed to dual-labeled mPtP@Lipo for 4 h, then fixed and imaged by CLSM (LSM-780, Zeiss, Germany).

In vitro cellular uptake

LLC cells were seeded in 12-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) and co-cultured with NIH3T3 (5 × 104 cells per well) in transwell inserts for 48 h. The cells were then treated with DiD-labeled mPtP@Lipo, PtP@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, and PtC@Lipo with the same concentration of DiD for 6 h. The LLC cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min, and stained with DAPI (5 μg/mL) for 15 min. The fluorescence intensity of DiD was observed accordingly and quantified by CLSM.

For flow cytometry analysis, after incubation with liposomes, the cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry using CytoFLEX (Beckman).

In vitro penetration in multicellular hybrid tumor spheroids

Multicellular hybrid tumor spheroids were established to mimic the TME in which tumor cells and fibroblasts grow together.33 Briefly, 55 μL of 1.0% agarose solution (w/v) was added in 96-well plates and then cooled to RT. LLC cells and NIH3T3cells were pre-dyed with Dil and DiO, respectively. Two types of cells were mixed at a ratio of 2:1, seeded onto agarose and cultured for 2–3 days to grow into spheroids. Afterward, spheroids were treated with DiD-labeled liposomes (mPtP@Lipo, PtP@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, and PtC@Lipo) with the same concentration of DiD. Tumor spheroids were washed and fixed, then observed and imaged with CLSM using z axis scanning from the top of the spheroids to the middle. The thickness of scanning layer of hybrid tumor spheroids was 20, 40, 60 and 80 μm, respectively.

In vitro apoptosis assay

LLC cells (2 × 105 cells per well) and NIH3T3cells (1 × 105 cells per well) were co-seeded in six-well plates and cultured with complete medium for 24 h. The cells were then treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtP@Lipo, PtP@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, or PtC@Lipo with the same concentration of Pt for 24 h. Afterward, the cellular apoptosis was analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Dalian Meilun Biotechnology, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

In vitro CAFs and SASP regulation

For senescence-associated β galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining, NIH3T3cells (1 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured with supernatant from LLC cells for 48 h to convert into CAFs. The cells were then treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo or PtP@Lipo with the same concentration of Pt for 24 h. Afterward, the cells were fixed and stained with SA-β-Gal Detection Kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Then the cells were observed under a bright-field microscope.

For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay for SASP factors, NIH3T3cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in six-well plates and cultured with supernatant from LLC cells for 48 h. The cells were then treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo, or PtP@Lipo with the same concentration of Pt for 24 h. Afterward, total RNA of CAFs was isolated with TRIeasy Total RNA Extraction Reagent (YEASEN, China) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 mg of total RNA, using HifairⅢ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (gDNA digester plus) (YEASEN, China) and qRT-PCR was performed using Hieff qRT-PCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Low Rox Plus) (YEASEN, China) according to the instruction. Details and primers are available in the experimental details section of the supplemental information.

For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), NIH3T3 cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in six-well plates and cultured with supernatant from LLC cells for 48 h. Then the cells were treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo, or PtP@Lipo with the same concentration of Pt for 24 h and replaced with fresh medium for another 24 h. The supernatant was then collected for IL-6 detection using Mouse IL-6 ELISA KIT (ABclonal, China) according to the manufacture’s instruction.

For western blot analysis, NIH3T3 cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in six-well plates and cultured with supernatant from LLC cells for 48 h. The cells were then treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo, or PtP@Lipo with the same concentration of Pt for 24 h. Afterward, the cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer with protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor on ice and the total solution was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay. The protein samples were then electrophoresed through a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, then transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), then incubated with primary antibody (4°C, overnight) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 h at RT). The blots were developed using an ECL substrate and visualized under FluorChem R (ProteinSimple, USA).

In vitro induction of immature DC maturation

Immature immature dendritic cells (DCs) were isolated and differentiated from bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. Immature DCs were seeded in 12-well plates (2 × 105 cells per well) and cultured with complete medium containing cytokines for 24 h. Meanwhile, LLC cells and NIH3T3 cells were seeded in 12-well plates, co-cultured for 24 h in complete medium, and then treated with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo, or PtP@Lipo for another 24 h. Immature DCs were then treated with LPS and the supernatant from pre-treated LLC cells for 24 h and then incubated with CD80 and CD86 antibodies (Biolegend, USA) to determine the frequency of mature DCs using flow cytometry.

In vitro stimulation of lymphocyte activation

Primary lymphocytes were isolated from spleens of healthy C57BL/6 mice by Mouse 1× Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Dakewe Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, mice were euthanized and spleens were collected under aseptic conditions. The spleen was shredded through 70-μm cell filters. The splenocytes suspended in lymphocyte separation medium were immediately collected, covered with RPMI 1640 medium, and centrifuged (800 × g, 25°C, 30 min). Afterward, the lymphocyte layer was collected, washed and re-suspended in RPMI 1640. The purified lymphocytes were seeded in 12-well plates (2 × 106 cells per well) and cultured with complete medium for 24 h. Meanwhile, DCs were treated with the supernatant from pre-treated LLC cells with PtLA, PtLA+PPD, mPtC@Lipo, PtC@Lipo, mPtP@Lipo, or PtP@Lipo for 24 h. The lymphocytes were then treated with pre-treated DCs for 12 h and then incubated with CD3 and CD69 antibodies (Biolegend, USA). The frequency of CD3+CD69+ lymphocytes was analyzed using flow cytometry.

Xenograft tumor model

To establish the stromal-desmoplastic tumor model, 1 × 106 LLC cells and 5 × 105 NIH3T3cells were mixed and suspended in 100 μL PBS and subcutaneously (s.c.) implanted into the right back of female C57BL/6 mice. Tumor volume was calculated using following formula: tumor volume (mm3) = ab2/2, in which a represents the length and b represents the width. Tumors were monitored daily and measured every other day using a digital caliper. The treatment started once the average tumor volume reached 80–100 mm3. The mice were divided into different groups randomly to ensure that each group had nearly equal starting average tumor volume. The mice were euthanized when their maximum tumor sizes reached humane endpoints, according to institutional policy concerning tumor endpoints in rodents. Moreover, to prevent excessive pain or distress, the mice were euthanized if tumors became ulcerated or if the mice showed any sign of ill health.

In vivo imaging and biodistribution analysis

LLC tumor-bearing mice were randomly grouped when the tumor volumes reached 80–100 mm3, and intravenously (i.v.) administrated DiR-loaded liposomes. Then, fluorescence imaging experiments were performed using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS) instrument at 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h post-injection. Afterward, the tumors and organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were collected and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed to characterize drug distribution in the body.

In vivo anti-tumor effect

LLC tumor-bearing mice were randomly assigned into five groups (n = 6 per group) and i.v. administrated PBS, free PtLA, mPPD@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, or mPtP@Lipo at the dose of 3 mg/kg Pt every other day continuously for seven times. The weight of mice and the size of tumors were monitored every other day, and tumor volumes were calculated. Two days after the last treatment, the mice were euthanized, and tumor and organs were harvested, weighed, and imaged.

Tumor inhibition rates (TIRs) were calculated according to the following formula: TIR (%) = (W − Ws)/W × 100, where W is the average weight of tumors in PBS group and Ws is the weight of tumors in other groups.

Flow cytometry to analyze tumor-infiltrating immune cells and CAFs

After the treatment with PBS, free PtLA, mPPD@Lipo, mPtC@Lipo, or mPtP@Lipo for seven continuous times, tumors were harvested and digested with collagenase IV for the analysis and evaluation of immune cells and CAFs.

Singlet suspensions were incubated with CD45, CD4, CD8, CD25, Foxp3, CD11c, CD80, CD86, F4/80, and CD206 antibodies (Biolegend, USA), respectively. Cell populations were sorted using flow cytometry and data were analyzed with FlowJo.

In vivo TME regulation analysis

For terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, the tumors were cut into slices and stained according to the manufacturer’s instruction to evaluate the systemic toxicity.

For SA-β-Gal staining, frozen sections were washed and stained with SA-β-Gal Detection Kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Then the sections were observed under a bright-field microscope.

For immunofluorescence (IF) staining, CD8, FAP, and Vimentin were stained using antibodies to evaluate the anti-tumor immune response and CAFs regulation. Then the sections were observed under CLSM.

For western blot analysis, tumors were harvested and digested following the protocol previously described, using B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), Caspase 3, and β-actin primary antibodies (ABclonal, China), respectively and HRP-secondary antibodies (ABclonal, China).

For ELISA analysis, tumors were harvested and digested following the protocol previously described. The supernatant was collected for IL-6 detection using Mouse IL-6 ELISA KIT (ABclonal, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed and all the graphs were made by GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. The comparison of two groups was conducted by two-tailed Student’s t test and the comparison of three or more groups was conducted by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test. Statistical significance was set at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82374296 and 82074277).

Author contributions

A.W. and J.W. designed the study. A.W., S.L., and R.Z. performed experiments. X.C., Y.Z., and J.X. provided assistance in some experiments. A.W. analyzed data and wrote the initial manuscript. J.W. funded and supervised the study. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omton.2024.200856.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Wang Y., Gan G., Wang B., Wu J., Cao Y., Zhu D., Xu Y., Wang X., Han H., Li X., et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Irradiated Cancer Cell Recovery Through Autophagy. EBioMedicine. 2017;17:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalluri R., Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts In Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X., Song E. Turning Foes To Friends: Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:99–115. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimoto H., Mundel T.M., Kieran M.W., Kalluri R. Identification of Fibroblast Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miao L., Lin C.M., Huang L. Stromal Barriers and Strategies for the Delivery of Nanomedicine to Desmoplastic Tumors. J. Control. Release. 2015;219:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Özdemir B.C., Pentcheva-Hoang T., Carstens J.L., Zheng X., Wu C.C., Simpson T.R., Laklai H., Sugimoto H., Kahlert C., Novitskiy S.V., et al. Depletion of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis Induces Immunosuppression and Accelerates Pancreas Cancer with Reduced Survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miao L., Wang Y., Lin C.M., Xiong Y., Chen N., Zhang L., Kim W.Y., Huang L. Nanoparticle Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment Enhances Therapeutic Efficacy of Cisplatin. J. Control. Release. 2015;217:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F., Long Q., Fu D., Zhu D., Ji Y., Han L., Zhang B., Xu Q., Liu B., Li Y., et al. Targeting SPINK1 in the Damaged Tumour Microenvironment Alleviates Therapeutic Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4315. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06860-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:31–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coppé J.P., Desprez P.Y., Krtolica A., Campisi J. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype: the Dark Side of Tumor Suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang B., Fu D., Xu Q., Cong X., Wu C., Zhong X., Ma Y., Lv Z., Chen F., Han L., et al. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype is Potentiated by Feedforward Regulatory Mechanisms Involving Zscan4 and TAK1. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04010-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia J., Zhang S., Zhang R., Wang A., Zhu Y., Dong M., Ma S., Hong C., Liu S., Wang D., Wang J. Targeting Therapy and Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Ginsenoside Rg3 Based Liposomes. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20:414. doi: 10.1186/s12951-022-01623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu K., Miao L., Goodwin T.J., Li J., Liu Q., Huang L. Quercetin Remodels the Tumor Microenvironment To Improve the Permeation, Retention, and Antitumor Effects of Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4916–4925. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cun X., Chen J., Li M., He X., Tang X., Guo R., Deng M., Li M., Zhang Z., He Q. Tumor-Associated Fibroblast-Targeted Regulation and Deep Tumor Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Drugs with a Multifunctional Size-Switchable Nanoparticle. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:39545–39559. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b13957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y., Campisi J., Higano C., Beer T.M., Porter P., Coleman I., True L., Nelson P.S. Treatment-Induced Damage To the Tumor Microenvironment Promotes Prostate Cancer Therapy Resistance Through WNT16B. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1359–1368. doi: 10.1038/nm.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Q., Fu Q., Li Z., Liu H., Wang Y., Lin X., He R., Zhang X., Ju Z., Campisi J., et al. The Flavonoid Procyanidin C1 Has Senotherapeutic Activity And Increases Lifespan In Mice. Nat. Metab. 2021;3:1706–1726. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arafa E.S.A., Refaey M.S., Abd El-Ghafar O.A.M., Hassanein E.H.M., Sayed A.M. The Promising Therapeutic Potentials of Ginsenosides Mediated Through p38 MAPK Signaling Inhibition. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J.L., Lv G.Y., He B.C., Zhang B.Q., Zhang H., Wang N., Wang C.Z., Du W., Yuan C.S., He T.C. Ginseng Saponin Metabolite 20(S)-Protopanaxadiol Inhibits Tumor Growth by Targeting Multiple Cancer Signaling Pathways. Oncol. Rep. 2013;30:292–298. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Xu H., Fu W., Lu Z., Guo M., Wu X., Sun M., Liu Y., Yu X., Sui D. 20(S)-Protopanaxadiol Inhibits Angiotensin II-Induced Epithelial- Mesenchymal Transition by Downregulating SIRT1. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:475. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.You L., Cha S., Kim M.Y., Cho J.Y. Ginsenosides are Active Ingredients In Panax Ginseng With Immunomodulatory Properties From Cellular To Organismal Levels. J. Ginseng Res. 2022;46:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang R.H., Kroll A.V., Gao W., Zhang L. Cell Membrane Coating Nanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2018;30 doi: 10.1002/adma.201706759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J., Zhu M., Nie G. Biomembrane-Based Nanostructures for Cancer Targeting And Therapy: From Synthetic Liposomes To Natural Biomembranes and Membrane-Vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;178 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J., Zhen X., Lyu Y., Jiang Y., Huang J., Pu K. Cell Membrane Coated Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles for Enhanced Multimodal Cancer Phototheranostics. ACS Nano. 2018;12:8520–8530. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b04066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L., Zhu Y., Wei X., Chen X., Li Y., Zhu Y., Xia J., Huang Y., Huang Y., Wang J., Pang Z. Nanoplateletsomes Restrain Metastatic Tumor Formation Through Decoy and Active Targeting in a Preclinical Mouse Model. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022;12:3427–3447. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zang S., Huang K., Li J., Ren K., Li T., He X., Tao Y., He J., Dong Z., Li M., He Q. Metabolic Reprogramming by Dual-Targeting Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Tumor Chemo-Immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;148:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim S.A., Su W., Chapman N.M., Chi H. Lipid Metabolism In T Cell Signaling And Function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022;18:470–481. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarano W., de Souza P., Stenzel M.H. Dual-Drug Delivery Of Curcumin And Platinum Drugs in Polymeric Micelles Enhances The Synergistic Effects: a Double Act for the Treatment Of Multidrug-Resistant Cancer. Biomater. Sci. 2015;3:163–174. doi: 10.1039/c4bm00272e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faget D.V., Ren Q., Stewart S.A. Unmasking Senescence: Context-Dependent Effects Of SASP in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:439–453. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You J., Li M., Tan Y., Cao L., Gu Q., Yang H., Hu C. Snail1-Expressing Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Induce Lung Cancer Cell Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Through miR-33b. Oncotarget. 2017;8:114769–114786. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niu N., Yao J., Bast R.C., Sood A.K., Liu J. IL-6 Promotes Drug Resistance Through Formation of Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells and Stromal Fibroblast Reprogramming. Oncogenesis. 2021;10:65. doi: 10.1038/s41389-021-00349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shintani Y., Fujiwara A., Kimura T., Kawamura T., Funaki S., Minami M., Okumura M. IL-6 Secreted from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Mediates Chemoresistance in NSCLC by Increasing Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Signaling. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016;11:1482–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang D., Liu J., Qian H., Zhuang Q. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: from Basic Science To Anticancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023;55:1322–1332. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirschhaeuser F., Menne H., Dittfeld C., West J., Mueller-Klieser W., Kunz-Schughart L.A. Multicellular tumor Spheroids: an Underestimated Tool Is Catching Up Again. J. Biotechnol. 2010;148:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.