1. Introduction

While anticoagulation remains the standard for treatment of acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), use of inferior vena cava filters (IVCFs) has increased in recent decades [1,2]. IVCFs were designed to trap thrombi originating in lower-extremity veins to prevent the development of clinically significant PE [2]. However, data demonstrating that IVCFs reduce thrombosis-related morbidity or mortality are lacking [2,3].

While current guidelines agree that IVCFs should be considered in instances of acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) and an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, details surrounding other indications vary, which contributes to the heterogeneity in use of IVCFs in practice [[1], [2], [3]]. IVCFs have been associated with recurrent lower-extremity DVT, filter migration, and fatal bleeding [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. Given the potential harms and healthcare expenditures associated with IVCFs, further efforts toward defining clear indications for their use are needed.

2. Methods

As a first step toward defining best practices, we developed an online cross-sectional survey of physicians to characterize IVCF use in fictional scenarios. In addition, we evaluated respondent center of practice, access to thrombosis consulting services, and use of societal guidelines to inform IVCF decision making.

Using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics XM), the survey was disseminated to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Anticoagulation Forum, Thrombosis Canada, Canadian Hematology Society, and Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR). The survey was tested in advance by thrombosis specialists for content validity. Results were summarized descriptively and analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared test, Fisher exact test, independent 2-sample t-test, or analysis of variance, as appropriate. The study received approval from Windsor Regional Hospital’s Research Ethics Board.

3. Results

A total of 115 physicians completed the survey (Table). Most respondents specialize in hematology/thrombosis (n = 43; 37.4%) and interventional radiology (n = 42; 36.5%), with half practicing in an academic/tertiary care facility (n = 57; 49.6%). Half (n = 60; 52.2%) practice in a center with established protocols for IVCF removal. Most respondents (n = 69; 60.0%) estimated IVCF removal rates at greater than 50% at their center of practice. The most commonly cited clinical guidelines used to inform IVCF insertion included the American College of Chest Physicians (n = 72; 62.6%) followed by the SIR (n = 45; 39.1%).

Table.

Demographics of survey respondents.

| Respondent demographic | Values (N = 115), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Specialty of respondent | |

| Hematologist/thrombosis specialist | 43 (37.4%) |

| Interventional radiologist | 42 (36.5%) |

| Internal medicine specialist | 15 (13.0%) |

| Critical care physician | 5 (4.3%) |

| Vascular medicine specialist | 2 (1.7%) |

| Respirologist | 2 (1.7%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 (1.7%) |

| Pediatric hematologist/oncologist | 2 (1.7%) |

| Medical oncologist | 2 (1.7%) |

| Type of practice | |

| Academic/tertiary care | 57 (49.6%) |

| Community | 58 (50.4%) |

| Access to thrombosis service | |

| Yes | 61 (53.0%) |

| No | 54 (47.0%) |

| Established IVCF removal protocols | |

| Yes | 60 (52.2%) |

| No | 55 (47.8%) |

| Guideline used to inform IVCF use | |

| American College of Chest Physicians, 2012/2016/2021 update | 72 (62.6%) |

| Society of Interventional Radiology, 2020 | 45 (39.1%) |

| American Heart Association, 2011 | 14 (12.2%) |

| European Society of Cardiology, 2014 | 10 (8.7%) |

| Other | 7 (6.1%) |

| National Institute for Health Care and Excellence, 2020 | 5 (4.3%) |

IVCF, inferior vena cava filter.

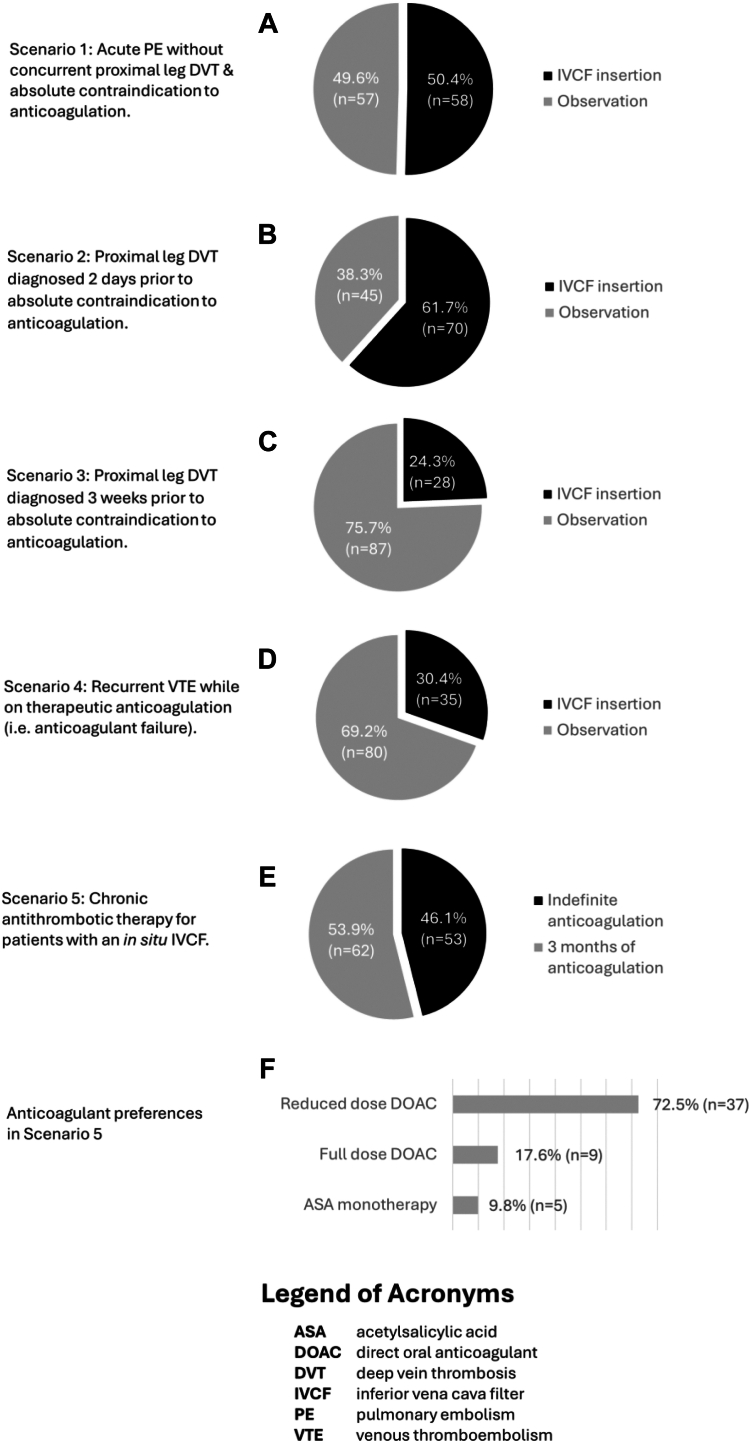

For the management of patients with an acute PE without concurrent proximal lower-extremity DVT and an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, 50.4% (n = 58) would proceed with an IVCF, whereas 49.6% (n = 57) would observe (Figure 1A). When presented with a scenario involving an acute proximal lower-extremity DVT diagnosed 2 days prior to an absolute contraindication to anticoagulation, 61.7% (n = 70) would proceed with an IVCF (Figure 1B). The remainder chose careful monitoring followed by gradual resumption of anticoagulation. In a similar scenario involving a nonacute proximal lower-extremity DVT that was diagnosed 3 weeks earlier, 24.3% (n = 28) would proceed with filter insertion (Figure 1C). In the setting of anticoagulation failure involving a recurrent proximal lower-extremity DVT that developed despite one month of therapeutic anticoagulation, only 30.4% (n = 35) would suggest an IVCF (Figure 1D).

Figure.

Physician responses to fictional inferior vena cava filter scenarios.

Finally, responses varied in terms of decision of duration and type of anticoagulation in the setting of a chronic indwelling IVCF (Figure 1E). In a scenario where a patient with a trauma-related VTE received an IVCF that was unable to be retrieved, 46.1% (n = 53) believed that the indwelling filter warranted indefinite anticoagulation, whereas 53.9% (n = 62) discontinued anticoagulation after 3 months of therapy. Among respondents who would advise indefinite antithrombotic therapy, most (70%) recommended a direct oral anticoagulant at a reduced dose (Figure 1F).

Across clinical scenarios, decisions to proceed with IVCF insertion varied according to clinical specialty, with hematologists/thrombosis specialists less likely to insert filters than other specialties (P = .02). However, type of practice (academic/tertiary vs community; P = .51) and access to a thrombosis consulting service (P = .10) did not impact decision making.

4. Discussion

Our survey revealed several interesting points regarding physician use of IVCFs. First, responses across clinical scenarios were generally mixed, reflective of the heterogeneous use of filters in the real world. This may be partly explained by the lack of high-quality clinical trial data on the use of IVCFs and uniform indications for IVCFs among current guidelines, especially as they fail to define the timing of an acute VTE and, consequently, the optimal timeframe to consider IVCF insertion.

More than half of survey respondents would proceed with a filter when presented with a case of a proximal lower-extremity DVT diagnosed 2 days prior to onset of a major bleed, while a quarter would advise on a filter if the DVT was diagnosed 3 weeks prior to the same bleed event. Risk of VTE recurrence is highest within the initial 2 weeks of diagnosis [8], which likely explains why fewer physicians would proceed with a filter in the latter setting; however, further clarity on use of filters following an acute VTE, such as the timing to be considered as “acute,” is needed.

Similar variability in responses was encountered in a case of an acute PE without concurrent lower-extremity DVT and major bleed, whereby approximately half of the respondents would proceed with a filter and the remainder would observe. Given that the role of IVCFs is to prevent the development of clinically significant PE from DVT, it is unclear whether they offer benefit in patients with an existing PE but without concurrent DVT, especially given that IVCFs are associated with risk of DVT. Data in this setting is limited to retrospective cohort studies [2,3].

Most respondents however did not feel that anticoagulation failure represented an indication to proceed with filter insertion, although both the American Heart Association and SIR guidelines recommend the use of an IVCF in this setting based on limited data, and over one-third of survey respondents chose the SIR and American Heart Association as their preferred guideline.

Finally, responses varied for the type and duration of anticoagulation advised in the case of an indwelling IVCF that was unable to be retrieved, with roughly half (46.1%) in favor of indefinite therapy. Filter removal rates have been estimated to be between 12% and 42% in practice [9]. Consequently, a potentially significant number of patients who receive an IVCF face the dilemma of chronic antithrombotic therapy owing to the concern that the filter itself poses inherent thrombotic risks, although the optimal anticoagulant for permanent venous stents and devices is unknown [10]. This further underscores the importance of ensuring filters are used in appropriate settings to minimize the risk of both acute and long-term complications if the filter is not retrieved. Post–IVCF insertion monitoring practices are not uniformly provided by the current guidelines.

Our study has several limitations. The survey was publicized to clinician networks involved in thrombosis and interventional radiology, possibly leading to a selection bias of respondents with an interest in this area. Also, we were unable to collect details relating to respondents’ country of practice since our institutional research ethics board recommended against it to safeguard the anonymity of respondent demographics. This similarly may have led to a selection bias as local practice patterns may influence IVCF decision making, and we could not adjust for over- or underrepresented localities in our analysis. Moreover, to keep the survey succinct, we only focused on selected aspects of filter use.

5. Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the variability in use of IVCFs in current clinical practice and emphasizes a need for clarity in instances that are poorly defined by available guidelines. Moreover, there is a need for reliable postinsertion monitoring practices to optimize removal rates and minimize risk of complications. Prospective research is needed to address filter use in these controversial settings to provide more evidence and clearer guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by a research start-up award by the Canadian Venous Thromboembolism Research Network (CanVECTOR).

Author contributions

R.L., M.S., J.C., and A.L.C. designed the survey, collected and analyzed the responses, and wrote the manuscript. R.L. performed statistical analyses and revised the manuscript. A.L.-L., D.S., and T.-F.W. provided expert opinion and revised the manuscript. A.L.C. conceptualized the study. All authors read and approved the latest version of the article.

Relationship Disclosure

There are no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Handling Editor: Dr Bethany Samuelson Bannow

References

- 1.Stein P.D., Kayali F., Olson R.E. Twenty-one-year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1541–1545. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duffett L., Carrier M. Inferior vena cava filters. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:3–12. doi: 10.1111/jth.13564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard P., Meyer G., Parent F., Mismetti P. Medical literature, vena cava filters and evidence of efficacy. A descriptive review. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:761–769. doi: 10.1160/TH13-07-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkhouli M., Morad M., Narins C.R., Raza F., Bashir R. Inferior vena cava thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:629–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.12.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajda J., Park A.N., Raj A., Raj R., Gorantla V.R. Inferior vena cava filters and complications: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15 doi: 10.7759/cureus.40038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montoya C., Rey J., Polania-Sandoval C.A., Bornak A., Shao T., Kenel-Pierre S. Inferior vena cava filter long term complications and retrieval techniques: a case series and literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2024;58:559–566. doi: 10.1177/15385744231226048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Ha T.G. Complications of inferior vena caval filters. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23:150–155. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-941445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner T.E., Saeed M.J., Novak E., Brown D.L. Association of inferior vena cava filter placement for venous thromboembolic disease and a contraindication to anticoagulation with 30-day mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angel L.F., Tapson V., Galgon R.E., Restrepo M.I., Kaufman J. Systematic review of the use of retrievable inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1522–1530.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee Cervi A., Applegate D., Stevens S.M., Woller S.C., Baumann Kreuziger L.M., Punchhalapalli K., et al. Antithrombotic management of patients with deep vein thrombosis and venous stents: an international registry. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21:3581–3588. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2023.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]